Abstract

AIM: To investigate preoperative differential diagnoses made between intrahepatic biliary cystadenoma and intrahepatic biliary cystadenocarcinoma.

METHODS: A retrospective analysis of patient data was performed, which included 21 cases of intrahepatic biliary cystadenoma and 25 cases of intrahepatic biliary cystadenocarcinoma diagnosed between April 2003 and April 2013 at the General Hospital of PLA. Potential patients were excluded whose diagnoses were not confirmed pathologically. Basic information (including patient age and gender), clinical manifestation, duration of symptoms, serum assay results (including tumor markers and the results of liver function tests), radiological features and pathological results were collected. All patients were followed up.

RESULTS: Preoperative levels of cancer antigen 125 (12.51 ± 9.31 vs 23.20 ± 21.86, P < 0.05) and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (22.56 ± 26.30 vs 72.55 ± 115.99, P < 0.05) were higher in the cystadenocarcinoma subgroup than in the cystadenoma subgroup. There were no statistically significant differences in age or gender between the two groups, or in pre- or post-operative levels of alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, total bilirubin (TBIL), and direct bilirubin (DBIL) between the two groups. However, eight of the 21 patients with cystadenoma and six of the 25 patients with cystadenocarcinoma had elevated levels of TBIL and DBIL. There were three cases in the cystadenoma subgroup and six cases in the cystadenocarcinoma subgroup with postoperative complications.

CONCLUSION: Preoperative differential diagnosis relies on the integration of information, including clinical symptoms, laboratory findings and imaging results.

Keywords: Intrahepatic biliary cystadenoma, Intrahepatic biliary cystadenocarcinoma, Preoperative differential diagnosis

Core tip: The number of females was larger than that of males in both groups. Carbohydrate antigen 19-9 has important significance in the preoperative diagnosis of intrahepatic biliary cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma. About half of the patients had elevated levels of total bilirubin (TBIL) and direct bilirubin (DBIL); therefore, we believe it is necessary to test TBIL and DBIL before surgery. The diagnosis relies on the integration of information consisting of clinical symptoms, laboratory findings and imaging results. The short-term and long-term prognoses of cystadenoma were better than those for cystadenocarcinoma.

INTRODUCTION

Intrahepatic biliary cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma are extremely rare neoplasms that account for only 5% of all solitary cystic lesions of the liver[1]. Advances in medical detection technology have made it possible to discover more instances of these diseases. The prognosis of intrahepatic biliary cystadenoma is good, but there is the potential for a malignant transformation into cystadenocarcinoma[2]. In this retrospective study, we reviewed our experience with diagnostic procedures for intrahepatic biliary cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma, supplemented with tests of preoperative liver function, which have been rarely reported in the literature.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We conducted a retrospective study of patient data that included 21 cases of intrahepatic biliary cystadenoma and 25 cases of intrahepatic biliary cystadenocarcinoma diagnosed between April 2003 and April 2013 at the General Hospital of PLA. Diagnosis was confirmed pathologically in all cases. Eighteen potential patients were excluded from the study because they were preoperatively diagnosed with intrahepatic biliary cystadenoma or cystadenocarcinoma but the diagnoses were not confirmed pathologically.

All of the patients in the two groups had complete resection. In the cystadenocarcinoma subgroup, seven had left lateral sectionectomies, eight had left hepatectomy, one had a right hepatectomy, four had right lateral sectionectomies, and five neoplasm enucleations. There were three left lateral sectionectomies, four left hepatectomy, one right hepatectomy, 10 neoplasm enucleations, and three open enucleations in the cystadenoma subgroup. During surgery we explored and ligated the branches of blood vessels and bile ducts to minimize the risk of hemorrhage and bile leak in the cutting edge. There were no perioperative deaths.

Basic information (including patient age and gender), clinical manifestation (including abdominal bloating or pain, fever, nausea, vomit, and jaundice), duration of symptoms, serum assay results [including tumor markers such as carbohydrate antigen (CA)19-9, CA125, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), alpha fetoprotein (AFP)], and the results of liver function tests [alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), total bilirubin (TBIL), and direct bilirubin (DBIL)], radiological features and pathological results were collected. All patients were followed up.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive analyses were used to characterize the study population. Continuous variables were compared using Student’s t test for variables with a skewed distribution, and data were reported as means ± SD or medians with ranges. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Clinical findings

The cystadenoma subgroup included 21 patients (16 females and five males), with a median age of 53.4 ± 13.2 years when diagnoses were confirmed histologically (range: 30-77 years). The cystadenocarcinoma subgroup included 25 patients, aged 52.0 ± 10.5 years when confirmed histologically (range: 35-74 years), with 20 females and five males. There were no statistically significant differences in age (P = 0.686) or gender (P = 0.988) between the two groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Basic patient information, clinical manifestation, duration of symptoms and pathology

| No. | Gender | Age | Clinical characteristics | Duration of symptoms (mo) | Location | Size (cm3) | Pathology |

| 1 | Female | 30 | Abdominal bloating | 3 | Left lobe | 9 × 6 × 5.5 | Cystadenoma |

| 2 | Female | 48 | Abdominal bloating | 13 | Left lobe | 5 × 4.5 × 2.5 | Cystadenoma |

| 3 | Female | 51 | Abdominal pain | 171 | Right lobe | 9 × 7 × 4 | Cystadenoma |

| 4 | Female | 44 | Asymptomatic | 52 | Left lobe | 4.5 × 3 × 2 | Cystadenoma |

| 5 | Male | 55 | Asymptomatic | 96 | Left lobe | 3 × 2.5 × 2.5 | Cystadenoma |

| 6 | Female | 77 | Asymptomatic | 241 | Right, left lobe | 14 × 10 × 5 | Cystadenoma |

| 7 | Female | 39 | Abdominal bloating, pain | 99 | Left lobe | 17.8 × 9.3 × 12.7 | Cystadenoma |

| 8 | Female | 73 | Abdominal bloating, pain | 12 | Left lobe | 9 × 5 × 4 | Cystadenoma |

| 9 | Male | 47 | Asymptomatic | 20 | Left, caudate lobe | 1.5 × 1 × 0.6 | Cystadenoma |

| 10 | Female | 41 | Asymptomatic | 120 | Right lobe | 12 × 8 × 4 | Cystadenoma |

| 11 | Male | 55 | Asymptomatic | 6 | Left lobe | 0.6 × 0.6 × 0.6 | Cystadenoma |

| 12 | Male | 50 | Abdominal pain | 30 | Left lobe | 5.5 × 3.5 × 2 | Cystadenoma |

| 13 | Female | 63 | Abdominal bloating | 10 | Left lobe | 9 × 7 × 7 | Cystadenoma |

| 14 | Female | 36 | Asymptomatic | 12 | Left lobe | 6 × 4 × 4 | Cystadenoma |

| 15 | Female | 56 | Asymptomatic | 3 | Right, left lobe | 4.5 × 4.5 × 3.5 | Cystadenoma |

| 16 | Female | 54 | Abdominal pain | 24 | Left lobe | 2 × 1.8 × 1 | Cystadenoma |

| 17 | Male | 74 | Abdominal pain | 30 | Left lobe | 9.5 × 7 × 3.5 | Cystadenoma |

| 18 | Female | 53 | Abdominal pain | 5 | Left lobe | 12 × 7.5 × 3 | Cystadenoma |

| 19 | Female | 55 | Abdominal bloating | 12 | Right, left lobe | 10 × 7.5 × 4 | Cystadenoma |

| 20 | Female | 76 | Abdominal pain | 20 | Right lobe | 11.5 × 8 × 6.5 | Cystadenoma |

| 21 | Female | 44 | Fever | 8 | Right lobe | 2.5 × 2 × 1.5 | Cystadenoma |

| 22 | Female | 60 | Asymptomatic | 22 | Left lobe | 1.5 × 1 × 0.2 | Cystadenocarcinoma |

| 23 | Female | 47 | Abdominal bloating | 1 | Left lobe | 5.5 × 5.5 × 5 | Cystadenocarcinoma |

| 24 | Male | 35 | Asymptomatic | 1 | Left lobe | 3.5 × 3 × 3 | Cystadenocarcinoma |

| 25 | Female | 58 | Fever, vomit | 12 | Left lobe | 10 × 7 × 5 | Cystadenocarcinoma |

| 26 | Female | 44 | Abdominal pain | 8 | Left lobe | 13 × 8 × 7 | Cystadenocarcinoma |

| 27 | Male | 59 | Asymptomatic | 28 | Right, left lobe | 11 × 10 × 2 | Cystadenocarcinoma |

| 28 | Female | 46 | Abdominal bloating | 1.3 | Left lobe | 4 × 4 × 3 | Cystadenocarcinoma |

| 29 | Male | 52 | Abdominal bloating | 13 | Left lobe | 5 × 4 × 2.5 | Cystadenocarcinoma |

| 30 | Female | 57 | Abdominal pain, fever, vomiting | 2 | Left lobe | 4 × 3 × 2 | Cystadenocarcinoma |

| 31 | Female | 55 | Abdominal pain, nausea | 9 | Right, left lobe | 8 × 7.5 × 7.5 | Cystadenocarcinoma |

| 32 | Female | 74 | Abdominal pain | 3 | Left lobe | 30 × 18 × 15 | Cystadenocarcinoma |

| 33 | Female | 41 | Abdominal pain, fever, vomiting | 72 | Left lobe | 4 × 3.5 × 1 | Cystadenocarcinoma |

| 34 | Female | 39 | Abdominal pain, jaundice | 2 | Left lobe | 10 × 9 × 5 | Cystadenocarcinoma |

| 35 | Female | 46 | Chills and fever | 3 | Right, left lobe | 2 × 1.3 × 0.6 | Cystadenocarcinoma |

| 36 | Female | 70 | Asymptomatic | 43 | Left lobe | 4.5 × 2.5 × 2 | Cystadenocarcinoma |

| 37 | Female | 51 | Asymptomatic | 96 | Right lobe | 5 × 3 × 2 | Cystadenocarcinoma |

| 38 | Female | 37 | Abdominal pain, fever, vomiting | 31 | Right, left lobe | 12.5 × 10 × 6 | Cystadenocarcinoma |

| 39 | Female | 51 | Abdominal bloating, vomiting | 3 | Left, caudate lobe | 9 × 7.5 × 4.5 | Cystadenocarcinoma |

| 40 | Female | 40 | Asymptomatic | 1 | Left lobe | 4.5 × 2.5 × 2 | Cystadenocarcinoma |

| 41 | Female | 51 | Asymptomatic | 2 | Right, left lobe | 10 × 8 × 5 | Cystadenocarcinoma |

| 42 | Male | 57 | Abdominal pain, jaundice | 1 | Left lobe | 2.5 × 1.7 × 1.5 | Cystadenocarcinoma |

| 43 | Female | 74 | Abdominal pain, fever, vomiting | 0.5 | Left lobe | 12 × 8 × 7 | Cystadenocarcinoma |

| 44 | Male | 50 | Asymptomatic | 2.6 | Left lobe | 2 × 0.7 × 0.5 | Cystadenocarcinoma |

| 45 | Male | 48 | Asymptomatic | 31 | Left lobe | 4 × 4 × 2 | Cystadenocarcinoma |

| 46 | Female | 57 | Abdominal pain, fever, vomiting | 8 | Middle lobe | 5.5 × 2.5 × 1.5 | Cystadenocarcinoma |

The duration of symptoms was significantly higher in the cystadenoma subgroup (47 ± 63.7 mo) than the cystadenocarcinoma subgroup (15.9 ± 23.9 mo) (P = 0.044). In the cystadenoma subgroup, there were 8 patients without any symptoms (38.1%), 12 patients with abdominal bloating or pain (57.1%), and one patient with fever (4.7%). The cystadenocarcinoma subgroup included 9 patients without any symptoms (36%), 4 patients who had only abdominal bloating or pain (16%), 7 patients with abdominal bloating/pain and fever/nausea/vomiting (36%), 2 patients with abdominal bloating/pain and jaundice, and one patient with only chills and fever (4%) (Table 1).

Laboratory findings

There was a statistically significant difference in preoperative levels of CA19-9 (P = 0.047) and CA125 (P = 0.044) between the cystadenoma subgroup and the cystadenocarcinoma subgroup (Table 2). Three of the 21 patients with cystadenoma had elevated CA19-9 (average 75.55 U/mL), as did seven of the 25 patients with cystadenocarcinoma (average 217.49 U/mL). Only one patient in the cystadenoma subgroup had a CA125 level (42.31 U/mL) higher than those in the normal range; five patients in the cystadenocarcinoma subgroup had CA125 levels (average 65.28 U/mL) higher than those in the normal range. Other tumor markers, including CEA and AFP, were unremarkable. The preoperative levels of CEA were 1.32 ± 0.72 ng/mL (range: 0.20-2.65 ng/mL) in the cystadenoma subgroup and 2.02 ± 1.16 ng/mL (range: 0.20-4.82 ng/mL) in the cystadenocarcinoma subgroup.

Table 2.

Preoperative levels of marker proteins

| CEA (ng/mL) | AFP (μg/L) | CA125 (U/mL) | CA19-9 (U/mL) | ALT (U/L) | AST (U/L) | TBIL (μmol/L) | DBIL (μmol/L) | |

| Cystadenoma | 1.32 ± 0.72 | 2.08 ± 1.18 | 12.51 ± 9.31 | 22.56 ± 26.30 | 40.03 ± 61.58 | 56.07 ± 141.54 | 19.75 ± 20.32 | 8.98 ± 16.60 |

| Cystadenocarcinoma | 2.02 ± 1.16 | 3.68 ± 7.02 | 23.20 ± 21.86 | 72.55 ± 115.99 | 30.43 ± 19.43 | 26.05 ± 14.02 | 20.02 ± 39.74 | 10.70 ± 31.14 |

All the carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) values in both subgroups were within the normal range: although P = 0.02 between the two groups. There was no statistical significance in the levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), total bilirubin (TBIL) and direct bilirubin (DBIL) before the operation (P > 0.05). However, eight of the 21 patients with cystadenoma and six of the 25 patients with cystadenocarcinoma had remarkable levels of TBIL and DBIL. AFP: Alpha fetoprotein; CA: Carbohydrate antigen.

Four of the 21 patients with cystadenoma had elevated ALT (average 106.75 U/L), and eight of the 25 patients with cystadenocarcinoma had elevated ALT (average 53.69 U/L). Two of the 21 patients with cystadenoma had elevated AST (632.9 U/mL, 111.3 U/mL), and two of the 25 patients with cystadenocarcinoma had elevated AST (47.6 U/mL, 77.5 U/mL). Eight of the 21 patients with cystadenoma had elevated TBIL (average 33.13 μmol/L), and six of the 25 patients with cystadenocarcinoma had elevated TBIL (average 53.13 μmol/L). Twelve of the 21 patients with cystadenoma had elevated DBIL (average 12.68 μmol/L), and 13 of the 25 patients with cystadenocarcinoma had elevated DBIL (average 18.41 μmol/L). There were no statistically significant differences in the levels of ALT, AST, TBIL, and DBIL between the two groups before the operation (P > 0.05, Table 2). However, many patients with cystadenoma or cystadenocarcinoma had elevated levels of TBIL and DBIL.

Radiological diagnosis

In the cystadenoma subgroup, we found a large cystic mass in 12 patients and a middle-sized cystic mass in five patients, the size of the mass ranged from 0.8 to 17 cm in greatest diameter, and one or more septa and mural nodules were observed in 15 patients by computed tomography (CT) scans and ultrasound. In the cystadenocarcinoma subgroup, we found a large cystic mass in 10 patients and a middle-sized cystic mass in 11 patients; size of the mass ranged from 1.1 cm to 22 cm in greatest diameter, and thick, coarse mural and septal calcifications were observed by CT scans and ultrasound.

In the cystadenoma subgroup there were only four patients fully diagnosed with cystadenoma and three patients diagnosed with cystadenocarcinoma or another malignancy using CT, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ultrasound (US). There were also eight patients diagnosed with cystadenoma or another benign tumor after examination using CT, MRI or US in the cystadenocarcinoma subgroup. CT, MRI and US were not particularly effective modalities for diagnosing these rare lesions (Table 3).

Table 3.

Radiological diagnosis

| Cystadenoma | Cystadenocarcinoma | Other benign tumor | Other malignancy | No qualitative | |

| Cystadenoma subgroup | 4 | 1 | 9 | 2 | 5 |

| Cystadenocarcinoma subgroup | 3 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 11 |

Ultrasonography, computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging were not particularly effective modalities for diagnosing these rare lesions.

Pathological results

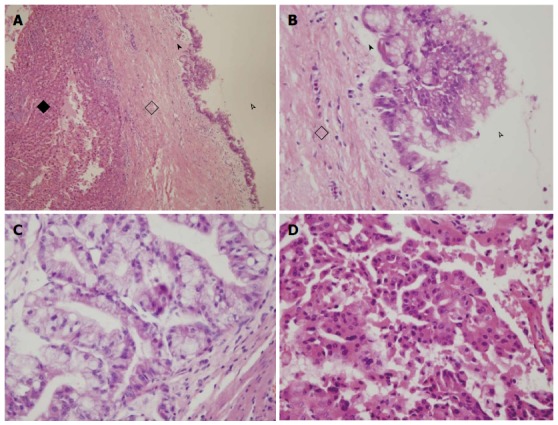

The average neoplasm size was 303.6 cm3 in the cystadenoma subgroup (range: 0.2-2102.4 cm3), and 511.6 cm3 in the cystadenocarcinoma subgroup (range: 0.3-8100 cm3, Table 1, P > 0.05). In the cystadenoma subgroup, there were 13 patients whose neoplasms were in the left lobe, four patients whose neoplasms were in the right lobe, three patients whose neoplasms were in both right and left lobes, and one patient whose neoplasm was in the left and caudate lobes. The cystadenocarcinoma subgroup included 17 patients whose neoplasms were in the left lobe, one patient whose neoplasm was in the right lobe, six patients whose neoplasms were in both of right and left lobes, and one patient whose neoplasm was in the left and caudate lobes (P > 0.05, Table 1). Mucinous cystadenoma was more common than papillary cystadenoma in the cystadenoma subgroup (Figure 1). The number of mucinous cystadenocarcinomas patients was similar to that of papillary cystadenocarcinoma; the present study included five patients with mucinous and papillary cystadenocarcinomas.

Figure 1.

Pathology of intrahepatic biliary cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma. A, B: Intrahepatic biliary cystadenoma (black diamond, hepatic tissue; hollow diamond, fibrous cyst wall; arrowhead, simple columnar epithelium; hollow arrowhead, cavity); C, D: Intrahepatic biliary cystadenocarcinoma. Mucinous cystadenocarcinoma with columnar epithelium, abundant cytoplasm, containing mucin, and nuclei located in the basal layer (C).

Postoperative complications

Cystadenoma subgroup: One case had bile leakage and abdominal infection nine days after surgery. Two cases had encapsulated fluid within the abdominal cavity at six days surgery.

Cystadenocarcinoma subgroup: One case had nausea and vomiting at 10 d after surgery. One case showed atelectasis, subphrenic effusion and intermittent fever at nine days after surgery, and about 952 mL of bilious brown liquid was drained out at 16 d after surgery. Two cases had wound infection. One case had an intestinal obstruction at 11 d after surgery. There was a bleeding varix at lower esophagus in one patient at 6 d after surgery.

Follow-up

Follow-up was available for all 46 patients. In the cystadenoma subgroup, 17 patients were alive at the end of follow-up (178.2 ± 75.7 wk, range: 82-377 wk), and four patients were lost to follow-up. The cystadenocarcinoma subgroup included 16 patients who were alive at the end of follow-up (270.6 ± 140.2 wk, range: 61-496 wk), four patients who had died by the end of follow-up (83.8 ± 49.0 wk, range: 52-156 wk), and five patients who were lost to follow. One patient showed recurrence at the time of 402 wk after the operation in the cystadenocarcinoma subgroup.

DISCUSSION

The first case of intrahepatic biliary cystadenoma was documented in 1887[3], and intrahepatic biliary cystadenocarcinoma was initially described and published by Willis in 1943[4]. Previous reports have indicated that women account for 85%-95% of all cases, which suggests that the malignancies might be influenced by hormones[5-7]. The primary treatment of cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma is hepatic resection[8]. Intrahepatic biliary cystadenomas may arise from congenitally misshapen bile ducts or primitive hepatobiliary stem cells. Intrahepatic biliary cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma are extremely rare tumors, and it can be difficult to differentiate between them[9,10]. We analyzed 46 patients retrospectively, and most of the results are consistent with the findings of our predecessors; however, we also found one difference from previous reports.

Tran et al[11] reported one child case (a 2-year-old girl) with intrahepatic biliary cystadenoma. Patients in their fifties make up a large percentage of the two groups, and the youngest age was 30 years in the present study. There was no statistically significant difference in age at presentation between the cystadenoma subgroup and cystadenocarcinoma subgroup, which is not consistent with previous reports[12,13]. Wang et al[10] reported that most intrahepatic biliary cystadenocarcinomas occurred in older males. Ishak et al[14] reported that all the cystadenomas were in middle-aged women, and the cystadenocarcinomas occurred in both male and female patients. However, our study population included significantly more females than males in both subgroups. One possible reason for this is the low sample size; therefore, we look forward to performing further research using data from multiple facilities.

Intrahepatic biliary cystadenoma is a slow growing tumor. The symptoms in the cystadenocarcinoma subgroup were more complex than in the cystadenoma group: clinical symptoms, including duration of symptoms, abdominal pain, fever, nausea, vomiting and jaundice can aid in differential diagnosis between the two diseases. Other symptoms, such as recurrent infection, pressure related symptoms, spontaneous rupture of the neoplasm and inferior vena cava obstructions have also been reported[15-17].

Horsmans et al[18] reported a higher level of CA19-9 and normal levels of CEA and AFP in patients with intrahepatic biliary cystadenoma or cystadenocarcinoma in 1996, suggesting that CA125 and CA19-9 are important for the preoperative diagnosis of intrahepatic biliary cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma. CA125 (for which there are few reports in the literature) and CA19-9 can help differentially diagnose the two diseases.

In the past, results of liver function tests have not been commonly reported in the literature. In the present study, levels of AST and ALT were normal in most patients in both groups, even when the symptom duration was very long, which suggests that liver function was not affected. Many patients had significantly elevated levels of TBIL and DBIL. It is necessary to pay close attention to preoperative TBIL and DBIL levels, although the information does not help with the differential diagnosis.

With the progress being made in abdominal imaging, more hepatic cystic neoplasms are now being discovered[19]. Biliary cystadenomas or cystadenocarcinomas appear as large, solitary, multilocular cystic neoplasms with internal septa and well circumscribed smooth margins on CT and MR imaging[20]. However, the misdiagnosis rate of intrahepatic biliary cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma using imaging methods was high among the 46 patients included in our study. It is difficult to distinguish between cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma using CT imaging[21]. Teoh et al[22] reported that preoperative differentiation using radiological imaging methods was inaccurate. We consider radiological imaging to play only a minor role in the differential diagnosis.

Diagnosis can be confirmed pathologically. The present study differs from the previous report by Fairchild et al[23], whereby more tumors occurred in the left lobe than in the other lobes. The location of neoplasm was regarded as not significant in the differential diagnoses between intrahepatic biliary cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma in our study.

The preferred treatment is surgery for patients with intrahepatic biliary cystadenocarcinoma and those who having symptoms of intrahepatic biliary cystadenoma. Postoperative complications of liver function have been described in some studies[24]. Patients with intrahepatic biliary cystadenocarcinoma had more postoperative complications, such as vomiting, intermittent fever, intestinal obstruction and a bleeding varix at the lower esophagus compared with those with intrahepatic biliary cystadenoma. It may be affected by the tumor location, size and extent of resection. Survival rates for cystadenocarcinomas can reach 87% at 5 years after complete resection[25]. Complete excision of the tumor is the best treatment for intrahepatic biliary cystadenomas and cystadenocarcinomas[26].

COMMENTS

Background

Intrahepatic biliary cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma are extremely rare cystic masses of the liver that are rarely reported, and it can be difficult to differentiate between the two. This study investigated preoperative differential diagnoses between intrahepatic biliary cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma.

Research frontiers

Abdominal imaging has improved, but cannot reliably distinguish intrahepatic biliary cystadenoma from cystadenocarcinoma. Future multi-institutional studies with the integration of clinical symptoms, laboratory findings and imaging results will be needed to better discover the biology, prognosis and management of these patients.

Innovations and breakthroughs

There was a statistically significant difference in preoperative levels of carbohydrate antigen 125 (P = 0.044) between the cystadenoma subgroup and the cystadenocarcinoma subgroup. There were no statistically significant differences in the levels of alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, total bilirubin (TBIL), and direct bilirubin (DBIL) between the two groups before the operation. However, many patients with cystadenoma or cystadenocarcinoma had elevated levels of TBIL and DBIL. The study population included significantly more females than males in both subgroups. There were more tumors occurring in the left lobe than in other lobes.

Applications

The results of this study will help physicians to make the correct preoperative differential diagnosis between intrahepatic biliary cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma.

Terminology

Intrahepatic biliary cystadenomas and cystadenocarcinomas are rare cystic neoplasms that usually arise in the liver. Intrahepatic biliary cystadenomas may arise from congenitally misshapen bile ducts or primitive hepatobiliary stem cells, and have potential to develop into cystadenocarcinomas.

Peer review

The paper describes the clinicopathological characteristics of cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma, with a particular focus on the preoperative differential diagnosis of these two rare diseases. The paper is of interest and may represent a valuable contribution to a topic that is scarcely explored in literature.

Footnotes

P- Reviewer: Maroni L, Serin KR, Zimmer V S- Editor: Gou SX L- Editor: Stewart G E- Editor: Du P

References

- 1.Del Poggio P, Buonocore M. Cystic tumors of the liver: a practical approach. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:3616–3620. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.3616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woods GL. Biliary cystadenocarcinoma: Case report of hepatic malignancy originating in benign cystadenoma. Cancer. 1981;47:2936–2940. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19810615)47:12<2936::aid-cncr2820471234>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henson SW, Gray HK, Dockerty MB. Benign tumors of the liver. VI. Multilocular cystadenomas. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1957;104:551–554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Willis RA. Carcinoma arising in congenital cysts of the liver. J Pathol. 1943;50:492–495. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martel G, Alsharif J, Aubin JM, Marginean C, Mimeault R, Fairfull-Smith RJ, Mohammad WM, Balaa FK. The management of hepatobiliary cystadenomas: lessons learned. HPB (Oxford) 2013;15:617–622. doi: 10.1111/hpb.12026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davies W, Chow M, Nagorney D. Extrahepatic biliary cystadenomas and cystadenocarcinoma. Report of seven cases and review of the literature. Ann Surg. 1995;222:619–625. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199511000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim HH, Hur YH, Koh YS, Cho CK, Kim JW. Intrahepatic biliary cystadenoma: Is there really an almost exclusively female predominance? World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:3073–3074. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i25.3073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lantinga MA, Gevers TJ, Drenth JP. Evaluation of hepatic cystic lesions. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:3543–3554. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i23.3543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hansman MF, Ryan JA, Holmes JH, Hogan S, Lee FT, Kramer D, Biehl T. Management and long-term follow-up of hepatic cysts. Am J Surg. 2001;181:404–410. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(01)00611-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang C, Miao R, Liu H, Du X, Liu L, Lu X, Zhao H. Intrahepatic biliary cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma: an experience of 30 cases. Dig Liver Dis. 2012;44:426–431. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tran S, Berman L, Wadhwani NR, Browne M. Hepatobiliary cystadenoma: a rare pediatric tumor. Pediatr Surg Int. 2013;29:841–845. doi: 10.1007/s00383-013-3290-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sang X, Sun Y, Mao Y, Yang Z, Lu X, Yang H, Xu H, Zhong S, Huang J. Hepatobiliary cystadenomas and cystadenocarcinomas: a report of 33 cases. Liver Int. 2011;31:1337–1344. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Soares KC, Arnaoutakis DJ, Kamel I, Anders R, Adams RB, Bauer TW, Pawlik TM. Cystic neoplasms of the liver: biliary cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218:119–128. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ishak KG, Willis GW, Cummins SD, Bullock AA. Biliary cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma: report of 14 cases and review of the literature. Cancer. 1977;39:322–338. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197701)39:1<322::aid-cncr2820390149>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williamson JM, Rees JR, Pope I, Strickland A. Hepatobiliary cystadenomas. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2013;95:507–510. doi: 10.1308/003588413X13629960046633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abhishek S, Jino T, Sarin GZ, Sandesh K, Prathapan VK, Ramachandran TM. An uncommon cause of ascites: spontaneous rupture of biliary cystadenoma. Australas Med J. 2014;7:6–10. doi: 10.4066/AMJ.2014.1875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arkadopoulos N, Yiallourou AI, Palialexis C, Stamatakis E, Kairi-Vassilatou E, Smyrniotis V. Inferior vena cava obstruction and collateral circulation as unusual manifestations of hepatobiliary cystadenocarcinoma. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2013;12:329–331. doi: 10.1016/s1499-3872(13)60052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horsmans Y, Laka A, Gigot JF, Geubel AP. Serum and cystic fluid CA 19-9 determinations as a diagnostic help in liver cysts of uncertain nature. Liver. 1996;16:255–257. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0676.1996.tb00738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vogt DP, Henderson JM, Chmielewski E. Cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma of the liver: a single center experience. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;200:727–733. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qian LJ, Zhu J, Zhuang ZG, Xia Q, Liu Q, Xu JR. Spectrum of multilocular cystic hepatic lesions: CT and MR imaging findings with pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2013;33:1419–1433. doi: 10.1148/rg.335125063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li X, Zhang JL, Wang YH, Song SW, Wang FS, Shi R, Liu YF. Hepatobiliary cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma: a single center experience. Tumori. 2013;99:261–265. doi: 10.1177/030089161309900223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Teoh AY, Ng SS, Lee KF, Lai PB. Biliary cystadenoma and other complicated cystic lesions of the liver: diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. World J Surg. 2006;30:1560–1566. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-0461-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fairchild R, Reese J, Solomon H, Garvin P, Esterl R. Biliary cystadenoma: a case report and review of the literature. Mo Med. 1993;90:656–657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ratti F, Ferla F, Paganelli M, Cipriani F, Aldrighetti L, Ferla G. Biliary cystadenoma: short- and long-term outcome after radical hepatic resection. Updates Surg. 2012;64:13–18. doi: 10.1007/s13304-011-0117-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Läuffer JM, Baer HU, Maurer CA, Stoupis C, Zimmerman A, Büchler MW. Biliary cystadenocarcinoma of the liver: the need for complete resection. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34:1845–1851. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(98)00166-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu J, Wang Y, Yu X, Liang P. Hepatobiliary mucinous cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma: report of six cases and review of the literature. Hepatogastroenterology. 2010;57:451–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]