Abstract

Acute respiratory distress syndrome is a life-threatening disorder caused mainly by pneumonia. Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) is a common nosocomial diarrheal disease. Disruption of normal intestinal flora by antibiotics is the main risk factor for CDI. The use of broad-spectrum antibiotics for serious medical conditions can make it difficult to treat CDI complicated by acute respiratory distress syndrome. Fecal microbiota transplantation is a highly effective treatment in patients with refractory CDI. Here we report on a patient with refractory CDI and acute respiratory distress syndrome caused by pneumonia who was treated with fecal microbiota transplantation.

Keywords: Clostridium difficile infection, Acute respiratory distress syndrome, Fecal microbiota transplantation

Core tip: Mechanical ventilation is the main supportive treatment option in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome, which makes it difficult to perform fecal microbiota transplantation in patients with Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) and acute respiratory distress syndrome. This case report demonstrated that fecal microbiota transplantation can be considered as a treatment for refractory CDI infection caused by acute respiratory distress syndrome.

INTRODUCTION

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a life-threatening medical problem with a reported mortality rate as high as 44%[1]. Pneumonia, sepsis, trauma, aspiration of gastric contents, inhalation of toxic gas, and drowning are the major causes of ARDS[2]. When ARDS is caused by pneumonia, broad-spectrum antibiotics are an essential treatment. Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) causes 15%-25% of antibiotic-associated diarrhea[3]. Cessation of causative antibiotics is essential for the treatment of CDI, but it is risky for most patients with CDI and ARDS caused by pneumonia to discontinue broad-spectrum antibiotics.

The incidence and severity of CDI are increasing[4]. Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) is an effective treatment option for recurrent, refractory CDI. Several studies have reported that the therapeutic efficacy of FMT for the treatment of refractory CDI is > 90%[5,6]. Mechanical ventilation is the main supportive treatment option in patients with ARDS[2], which makes it difficult to perform FMT in patients with CDI and ARDS. Here, we report on a patient with refractory CDI with ARDS caused by pneumonia who was treated successfully with FMT.

CASE REPORT

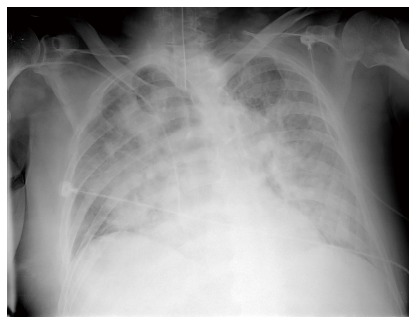

An 83-year-old man with hypertension, diabetes, and prostatic hypertrophy visited our hospital after 2 d of fever and cough accompanied by the production of sputum. Consolidation was noted on chest X-ray. Clarithromycin and ceftriaxone was administered. Despite the antibiotic treatment, the pneumonia did not improve. We changed antibiotics to tazobactam and levofloxacin on hospital day 7. On hospital day 10, dyspnea was aggravated and arterial blood gas analysis on 15 L of O2 supplied by reserve mask produced the following values: pH 7.33, PaCO2 32.0 mmHg, PaO2 36.0 mmHg, HCO3 16.0 mEq/L, SaO2 62%. After endotracheal intubation, mechanical ventilation was applied. Arterial blood gas analysis on 1.0 of fraction of inspired oxygen produced the following values: pH 7.43, PaCO2 35.0 mmHg, PaO2 46.0 mmHg, HCO3 23.0 mEq/L, SaO2 84%. Chest X-ray showed bilateral infiltration of the lungs (Figure 1). The patient met the criteria of ARDS. We changed antibiotics to meropenem and teicoplanin. We used meropenem and teicoplanin until pneumonia was improved.

Figure 1.

Chest X-ray shows bilateral infiltration of lung.

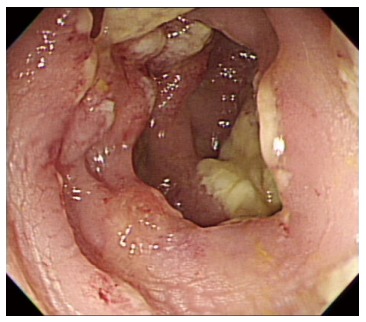

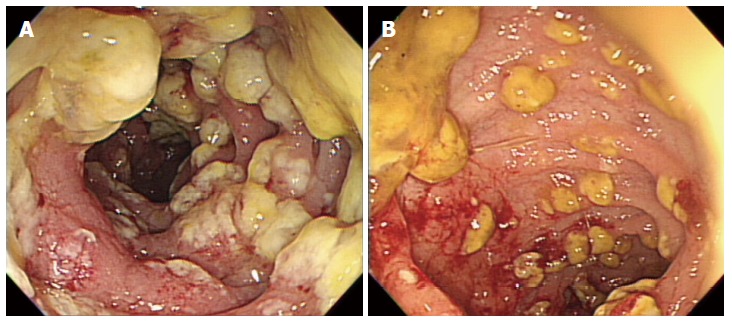

On hospital day 13, diarrhea developed and the frequency was 5-6 times/d. Stool culture (chromID C. difficile; bioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France) and toxin assay by enzyme immunoassay (Wampole Tox A/B Quik Chek; Alere, Orlando, FL, United States) was conducted. A stool sample was positive for C. difficile toxins A and B. The patient was diagnosed with CDI and oral metronidazole (500 mg × 3 times/d) was added. Antibiotics for pneumonia was used for 13 d prior to development of CDI. We could not stop antibiotic treatment and total duration of antibiotic use for pneumonia was consecutive 33 d. Despite 10 d of treatment with oral metronidazole, the amount and frequency of diarrhea increased. Sigmoidoscopy showed multiple yellowish plaques in the rectum and sigmoid colon (Figure 2). We concluded that the oral metronidazole was ineffective and changed the medication to oral vancomycin. Vancomycin dosing was 125 mg × 4 times/d. After 7 d of treatment with oral vancomycin, the patient developed hematochezia. Follow-up sigmoidoscopy showed hemorrhagic changes and an increase in the extent of yellowish plaques compared with the previous sigmoidoscopy (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Sigmoidoscopy shows focal yellowish plaques in the sigmoid colon.

Figure 3.

Follow-up sigmoidoscopy. A: Sigmoidoscopy shows multiple yellowish plaques in the sigmoid colon. B: Sigmoidoscopy shows focal hemorrhagic changes in the sigmoid colon.

We conducted FMT on hospital day 29. Laboratory findings on the day of FMT were as follows: hemoglobin 8.1 g/dL; platelets 332 ×109/L; white blood cell count 8060/mm3; and c-reactive protein 9.0 mg/dL; albumin 2.6 g/dL; and creatinine 1.4 mg/dL. The stool source for FMT was from a family donor. We checked the donor’s blood test and stool test, and HBsAg, HCV Ab, VDRL, C. difficile toxin, and HIV were not detected. The donor had no history of antibiotic use within the past year or any history of chemotherapy. Eighty grams of stool and 240ml of normal saline (1:3) were placed into a blender (NJM-9060; NUC Electronics, Daegu, South Korea). The suspension was passed through a stainless steel tea strainer to remove large particles. FMT was performed using upper endoscopy. The endoscope was inserted to the second portion of the duodenum. The prepared fecal suspension was transferred to the patient’s bowel through the biopsy channel of the endoscope. The procedure time was about 5 min. One day after FMT, the frequency of diarrhea had decreased to once per day, and the diarrhea resolved 5 d after the FMT. Three months after the FMT, the patient received broad-spectrum antibiotics for pneumonia and urinary tract infection, but he did not develop CDI again during hospitalization. The patient left the hospital on hospital day 95.

DISCUSSION

ARDS reflects the acute onset of hypoxemic disease. The most common causes of ARDS are pneumonia and sepsis[2]. ARDS complicates acute kidney injury, nosocomial infection, deep-vein thrombosis, and gastrointestinal bleeding. However, the incidence of CDI in patients with ARDS has not been reported. There is a case report of ARDS caused by CDI[7]. Our patient was an older man with pseudomembranous colitis, which was diagnosed as severe CDI on sigmoidoscopy[8,9]. In cases of severe CDI, 10-14 d of oral vancomycin is recommended[8]. However, we could not use vancomycin for the first treatment regimen because of renal insufficiency. We started metronidazole and changed it to vancomycin. Despite 7 d of treatment with oral vancomycin, his symptoms became aggravated, and we considered that the CDI was refractory to conventional therapy.

FMT is highly effective in treating refractory CDI, and the response to FMT is rapid[5]. FMT can be performed through a nasogastric tube, retention enema, upper endoscopy, or colonoscopy. Recommended dosing regimen is > 50 g of stool regardless of infusion route. Relapse rate of CDI was lower when > 50 g of stool was used[6]. Because mechanical ventilation was applied to this patient, it was difficult to conduct FMT using colonoscopy, and colonoscopy requires more time than upper endoscopy. Because the patient was sedated with midazolam, we thought that he might not retain the fecal suspension. Furthermore, FMT using colonoscopy had the risk of perforation because of inflamed colonic mucosa. FMT performed via upper endoscopy has a risk of aspiration; however, endotracheal intubation for the treatment of ARDS had been performed several days before the procedure and there was no aspiration. The diarrhea improved 1 d after FMT and was resolved 5 d after FMT. Broad-spectrum antibiotics were prescribed continuously after FMT, and there was no recurrence of CDI.

To our knowledge, this is the first case report of CDI complicated by ARDS that was treated successfully with FMT. When ARDS complicates refractory CDI, FMT can be considered as a treatment for CDI. However, in such cases, FMT should be performed cautiously because of the patient’s serious medical condition.

COMMENTS

Case characteristics

An 83-year-old man with acute respiratory distress syndrome and diarrhea.

Clinical diagnosis

Refractory Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) complicated by acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Related reports

There are some case reports of CDI complicated by acute respiratory distress syndrome. However, this is the first case report of CDI complicated by acute respiratory distress syndrome that was treated successfully with fecal microbiota transplantation.

Experiences and lessons

Fecal microbiota transplantation cured a critically ill patient with refractory CDI and acute respiratory distress syndrome caused by pneumonia who was treated with fecal microbiota transplantation.

Peer review

This case report demonstrated that fecal microbiota transplantation can be considered as a treatment for refractory CDI caused by acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Footnotes

P- Reviewer: Apewokin S, Alhazzani W, Rodriguez D S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Du P

References

- 1.Phua J, Badia JR, Adhikari NK, Friedrich JO, Fowler RA, Singh JM, Scales DC, Stather DR, Li A, Jones A, et al. Has mortality from acute respiratory distress syndrome decreased over time?: A systematic review. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179:220–227. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200805-722OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dushianthan A, Grocott MP, Postle AD, Cusack R. Acute respiratory distress syndrome and acute lung injury. Postgrad Med J. 2011;87:612–622. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2011.118398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartlett JG, Gerding DN. Clinical recognition and diagnosis of Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46 Suppl 1:S12–S18. doi: 10.1086/521863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Warny M, Pepin J, Fang A, Killgore G, Thompson A, Brazier J, Frost E, McDonald LC. Toxin production by an emerging strain of Clostridium difficile associated with outbreaks of severe disease in North America and Europe. Lancet. 2005;366:1079–1084. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67420-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brandt LJ, Aroniadis OC, Mellow M, Kanatzar A, Kelly C, Park T, Stollman N, Rohlke F, Surawicz C. Long-term follow-up of colonoscopic fecal microbiota transplant for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1079–1087. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gough E, Shaikh H, Manges AR. Systematic review of intestinal microbiota transplantation (fecal bacteriotherapy) for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:994–1002. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jacob SS, Sebastian JC, Hiorns D, Jacob S, Mukerjee PK. Clostridium difficile and acute respiratory distress syndrome. Heart Lung. 2004;33:265–268. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen SH, Gerding DN, Johnson S, Kelly CP, Loo VG, McDonald LC, Pepin J, Wilcox MH. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults: 2010 update by the society for healthcare epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the infectious diseases society of America (IDSA) Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31:431–455. doi: 10.1086/651706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zar FA, Bakkanagari SR, Moorthi KM, Davis MB. A comparison of vancomycin and metronidazole for the treatment of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea, stratified by disease severity. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:302–307. doi: 10.1086/519265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]