Abstract

This paper presents the results of a survey among key informants that was conducted between June and September 2011 in Breast Cancer Centers that were accredited according to the criteria of the German Cancer Society (DKG). The survey intended to assess the degree to which the breast cancer center concept was accepted among the key informants as well as to gain an overview over structures and processes in the centers. The Questionnaire for Breast Cancer Centres Key Informants 2011 (FRIZ 2011) was used with two reminders having been sent out. Questionnaires were sent back from 149 of the 243 initially contacted hospitals (response rate: 61.3 %). The vast majority of respondents indicated to be part of the Breast Cancer Center management. 110 of the 149 hospitals did also participate in the patient survey conducted in 2010. Among the key informants surveyed, the concept is highly accepted with regard to improvements in patient care. Overall, the concept is regarded as “good” or “very good” by almost all respondents. Both contact to resident doctors and the hospitalsʼ reputations improved since the implementation of the concept. Quality and patient safety were more often on the agenda than financial performance in the quality circles with the main co-operation partners of the Breast Cancer Centers.

Key words: key informant survey, breast cancer centers, breast cancer

Abstract

Zusammenfassung

In dieser Arbeit sind die Ergebnisse der zwischen Juni und September 2011 in den nach den Kriterien der Deutschen Krebsgesellschaft e. V. (DKG) zertifizierten Brustkrebszentren durchgeführten Befragung von Schlüsselpersonen dargestellt. Ziel der Befragung war es, nach der Patientenperspektive (Kowalski et al. in diesem Heft) auch die versorgerseitige Akzeptanz des Brustkrebszentrenkonzepts zu untersuchen und einen vergleichenden Überblick über Strukturen und Prozesse der Brustkrebszentren in Deutschland zu gewinnen. Die schriftliche Befragung wurde in Anlehnung an die Total-Design-Methode nach Dillman mit 2 Erinnerungsschreiben durchgeführt. Zum Einsatz kam der Fragebogen für Schlüsselpersonen in Brustkrebszentren 2011 (FRIZ 2011). Aus jedem Zentrum wurde ein Ansprechpartner um Teilnahme gebeten. Aus 149 von insgesamt 243 Operationsstandorten gingen ausgefüllte und auswertbare Fragebogen ein. Dies entspricht einem Rücklauf von 61,3 %. Die weit überwiegende Mehrheit der Personen, die den Fragebogen ausgefüllt haben, gab an, Teil der Brustzentrumsleitung zu sein und regelmäßig an den Qualitätszirkeln mit den Hauptkooperationspartnern der Brustkrebszentren teilzunehmen. 110 der 149 teilnehmenden Operationsstandorte hatten zuvor bereits an der Befragung von Patientinnen mit primärem Mammakarzinom in den gleichen Zentren teilgenommen. Im Hinblick auf Verbesserungen der Versorgungsqualität genießt das Konzept unter den befragten Schlüsselpersonen eine hohe Zustimmung. Das Konzept wird insgesamt fast durchgehend als gut oder sehr gut bewertet. Sowohl der Kontakt zu den niedergelassenen Ärzten als auch das Ansehen der Häuser haben sich in der Wahrnehmung der Befragten seit Einführung des Konzepts in der weit überwiegenden Zahl der Häuser verbessert. In den Qualitätszirkeln mit den Hauptkooperationspartnern nehmen Themen zu Qualität und Patientensicherheit mehr Raum ein als finanzielle Themen.

Schlüsselwörter: Schlüsselpersonenbefragung, Brustkrebszentren, Mammakarzinom

Introduction

As part of a 3-stage model for certified oncological care structures, the Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft (German Cancer Society) (DKG) has been awarding certification status to breast cancer centres since 2003. This paper sets out the results of the survey of key informants carried out in 2011 at breast cancer centres certified in accordance with the criteria set down by the Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft e. V. (DKG) and the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Senologie e. V. (DGS). The survey was carried out after the survey of patients with primary breast cancer from the same hospitals which was carried out in 2010 1. The aim of the survey of key informants was to investigate the acceptance of the breast cancer centre concept on the part of care providers, following on from the study of the patientsʼ perspectives, and to obtain a comparative overview of the structures and processes of the breast cancer centres identified in Germany. The data can also be used to investigate whether structures and processes are recognisably associated with various (patient-reported) outcomes. To this end, the results of this survey can be linked, for example, to the results of the patient survey from 2010. It is also conceivable to link this data to other secondary data in order to clarify differences between the hospitals. The survey was carried out for the first time in the centres certified by the DKG and processed by the Institute of Medical Sociology, Health Services Research and Rehabilitation Science (IMVR) within the Faculty of Human Sciences and the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Cologne. Comparable key informant surveys were already carried out in 2007 and 2010 in the breast centres certified in accordance with the requirements of the State of North Rhine-Westphalia. This article describes how the survey was carried out and presents selected results. The results are then subjected to critical discussion.

Material and Methods

The survey encompassed all surgical facilities of breast cancer centres certified by the Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft e. V. (DKG) provided they had not already been certified in accordance with the criteria of the State of North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) and had, therefore, already been included in a survey of key informants carried out in 2010 by the IMVR. A letter was sent in June 2011 to one contact in a managerial position within each surgical facility. The total of 243 hospital contacts from 198 certified breast cancer centres were asked to fill out the key informantsʼ survey questionnaire or to pass it on to another individual who was qualified and able to complete it instead. The contacts in this case were employees of certified breast cancer centres who had already served as contacts for the patient survey previously carried out, i.e. in all cases the manager or centre coordinator or his appointed deputy. No other inclusion or exclusion criteria were defined. The participation of the certified breast cancer centres in the survey was voluntary. The written survey was carried out based on the Total Design Method after Dillman 2. This method involves multiple letters and reminders being sent to those involved in order to achieve as high a response quota as possible 3, 4. Together with the questionnaire, the respondents were sent a postage-paid return envelope, as well as a letter which explained the objective of the survey and contained information regarding data protection. Three weeks after the questionnaire was sent out, a first reminder letter was dispatched. Three weeks after this letter, a second reminder was sent out with a questionnaire and return envelope enclosed. The survey period stretched from mid-June to the end of September 2011. The end of the survey period was defined as 30th September 2011. Questionnaires received after this date could no longer be classed as valid.

The method, classified in literature as the “key informant survey” is a frequently-used method and utilises the knowledge of employees who generally have decision-making authority. The advantages of this method are summarised by Rousseau, for example 5. Managers therefore often have an excellent knowledge of the structures and processes within an organisation (see also 6). One advantage over significantly more elaborate employee surveys is that key informant surveys enable a larger number of hospitals to be surveyed at lower cost. At this point it should be mentioned that the responses of individual key informants in some circumstances may vary from those of other members of an organisation or may be distorted due to the subjectivity of the answers 7. It must, therefore, be pointed out that the information, even given in response to apparently “hard” factual questions, such as the number of operations per year or the number of patients enrolled in clinical studies, does not necessarily reflect the true value.

Survey tool

The 2011 Questionnaire for Key Informants in Breast Cancer Centres (FRIZ 2011) was tailored in collaboration with the DKG to the particular situation of DKG-certified breast cancer centres. Some of the questions occurred in the survey carried out in 2010 in North Rhine-Westphalia by the IMVR in the breast centres certified by the Westphalia-Lippe Medical Association. Others were written for this survey or are already used in similar surveys in the USA. The tool used comprised 11 themed areas containing a total of 73 questions. Borrowing from the requirements made of breast cancer centres for (re-)certification and in light of established parameters and scales, such as for documenting collaboration, it was possible to use questions and items that have already been tried and tested. The survey tool primarily comprised factual questions regarding structures and processes within the breast cancer centre, but also included a section on the evaluation of the breast cancer centre concept.

Data input and preparation

The questionnaires received were sequentially processed using the Teleform® program. The program includes an error analysis, in which input errors and unclear answers are identified. In cases of doubt, the option of comparing the data with the original questionnaire was used in order to correct any errors. The results set out in the tables below were calculated with the aid of the statistics program IBM SPSS® Version 19.0. The valid percentages in each case (without taking account of missing cases) are reported unless specified otherwise. In view of the automatic rounding-up and rounding-down, it may be that the sum of the individual percentage figures in the tables does not add up to exactly 100.

Results

Selected results from the key informantsʼ survey in the DKG-certified breast cancer centres carried out in 2011 are reported below. The complete results report can be seen on the websites of the DKG and IMVR. The results are presented primarily with an overview of the return achieved. The results of the questions in the FRIZ 2011 are then set out either in table form or bar charts. The number of answers missing per question is also stated in each case.

Return rate and sample description

Completed questionnaires suitable for evaluation were received from 149 of a total of 243 surgical facilities. This equates to a return rate of 61.3 %. In view of overlaps of returns and sending of reminder letters, a second questionnaire was received from four surgical facilities. These questionnaires were not taken into account. After the expiry of the pre-defined survey period, four further questionnaires were received which could not be taken into account for the evaluations that followed. The significant majority of individuals who filled out the questionnaires stated that they were part of the breast cancer centreʼs management team (86.2 %) and regularly took part in quality circles with primary cooperation partners of the certified breast cancer centres (97.9 %). The majority of the hospitals participating in the survey are publicly owned (53.8 %).

110 of the 149 participating surgical facilities had previously taken part in the survey of patients with primary breast cancer mentioned earlier. Among the hospitals that had taken part in the patient survey, the participation quota for the key informantsʼ survey was significantly higher (69 %) than among the hospitals that had not taken part in the survey (46 %). The basis for the further results is the information from the 149 hospitals taking part in the key informantsʼ survey.

Table 1 shows the measures of central tendencies and variation of selected hospital characteristics (mean values, minimum, maximum, standard deviation, median). The differences between the hospitals in terms of the number of operating doctors and the number of specialist oncology nurses are clear. The time between the establishment of a diagnosis and the date of surgery also varies considerably, while the mean value of the average wait is five days with just a small standard deviation.

Table 1 Selected hospital characteristics: Mean values, minimum, maximum, standard deviation, median.

| Mean value | Minimum | Maximum | Standard deviation | Median | No details given | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| How many doctors (lead surgeons) operate on patients with primary breast cancer at your surgical facility? | 3.2 | 1 | 16 | 1.7 | 3 | 1 |

| How many trained specialist cancer nurses work at your surgical facility? | 2.3 | 0 | 20 | 2.1 | 2 | 4 |

| How many days, on average, elapse between the primary breast cancer being diagnosed at your surgical facility and the actual surgery? | 8.8 | 0 | 25 | 4.2 | 8 | 3 |

| How long, on average, is the in-patient stay of patients with primary breast cancer at your surgical facility? | 5.3 | 3 | 10 | 1.3 | 5 | 3 |

Table 2 shows the implementation of selected structure and process characteristics. All of the selected aspects are implemented by the majority of surgical facilities. The requirements for certification (e.g. primary tumour documentation, follow-up tumour documentation) are satisfied by almost all hospitals.

Table 2 Implementation of selected structural and process characteristics.

| To what extent do the following statements apply? At our breast cancer centre (incl. all surgical facilities) … | No | No, but in progress/planned | Yes | No details given |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| There is a written concept for the organisation of tumour MDTs. | 4.1 | 0.7 | 95.3 | 1 |

| There are written procedural instructions regarding the involvement of self-help groups. | 20.8 | 7.4 | 71.8 | 0 |

| There is a defined patient pathway which applies to all patients with primary breast cancer. | 2.7 | 5.4 | 91.9 | 0 |

| There are fixed shared weekly appointments regardless of the MDT (e.g. set days). | 36.9 | 3.4 | 59.7 | 0 |

| We have defined goals. | 1.3 | 1.3 | 97.3 | 0 |

| We have shared quality management. | 3.4 | 0 | 96.6 | 0 |

| The vision of the breast cancer centre is anchored in a mission statement. | 8.1 | 3.4 | 88.6 | 0 |

| We have a corporate design (e.g. logo). | 7.4 | 4.7 | 87.9 | 0 |

| We maintain primary tumour documentation. | 0.7 | 1.3 | 98.0 | 0 |

| We maintain follow-up tumour documentation. | 0.7 | 2.0 | 97.3 | 0 |

Specialist oncology nurses are relieved of their other nursing duties completely in 22.5 % of hospitals and partially in a further 41.5 % of hospitals (no illustration).

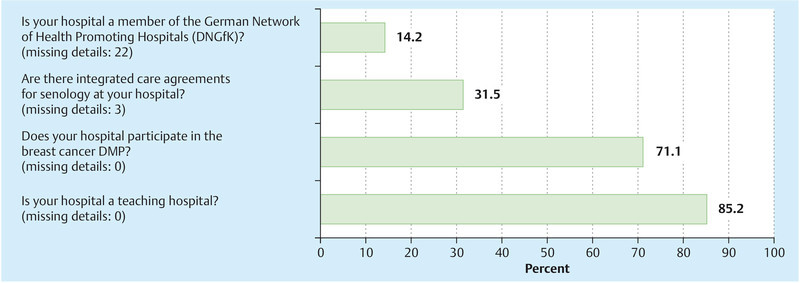

The majority of responding hospitals are teaching hospitals (Fig. 1). 71 % of the hospitals are involved with the breast cancer DMP, whereas just under a third are party to integrated care agreements. 14 % of hospitals are members of the network of health promoting hospitals. Of note is the relatively high proportion of missing answers to this question (n = 22).

Fig. 1.

DNGfK, integrated care agreements, DMP breast cancer and teaching hospital.

Inclusion and information of patients

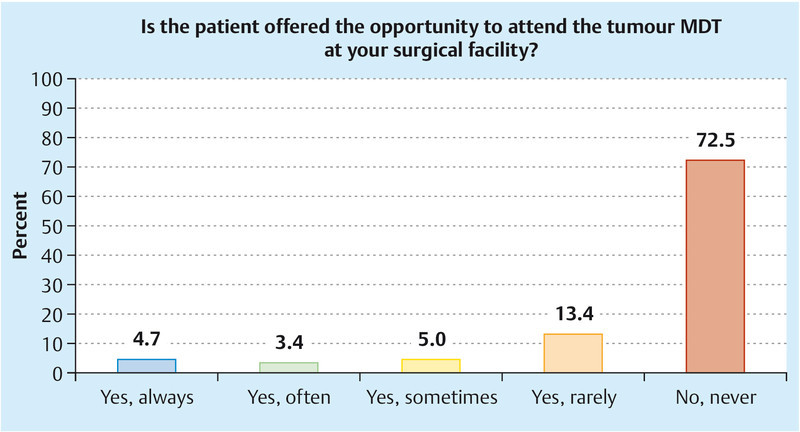

Fig. 2 shows whether patients are offered the opportunity to attend tumour MDTs at the surgical facilities. This is always the case in just under 5 % of hospitals, and never in 72.5 %.

Fig. 2.

Opportunity to participate in tumour MDTs in valid percentages (missing details: 0).

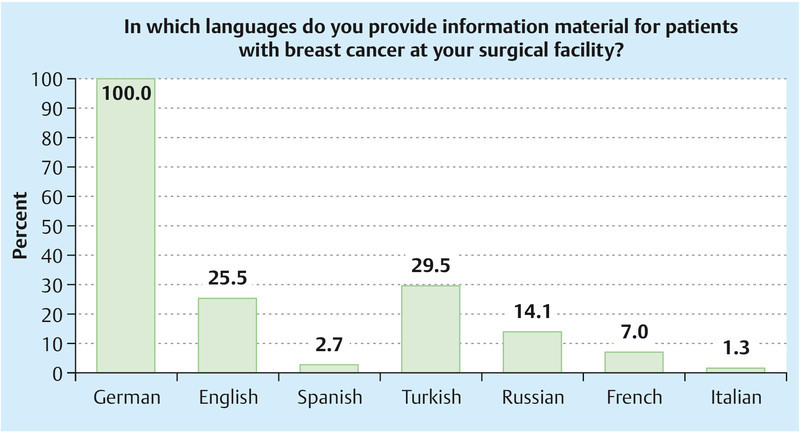

All surgical facilities provide their patients with information via the breast cancer centre (Table 3). In more than three quarters of the hospitals, information folders, flyers and information on the website are used. Information material for patients is also provided in some hospitals in languages other than German, the most common being Turkish (29.5 % of hospitals) and English (25.5 %) (Fig. 3).

Table 3 Patient information.

| In what form is information passed on via the breast cancer centre to patients? (Please select all that apply) | No | Yes | No details given |

|---|---|---|---|

| Information folder | 16.1 | 83.9 | 0 |

| Information session | 34.2 | 65.8 | 0 |

| Website | 22.1 | 77.9 | 0 |

| Flyers | 19.5 | 80.5 | 0 |

| Not at all | 100 | 0 | 0 |

Fig. 3.

Provision of multi-lingual information materials in valid percentages (missing details: 0).

Cooperation with referring doctors

In virtually all surgical facilities, contact with general practitioners is established via information sessions and further training courses (Table 4). In around 40 % of surgical facilities there are also regular or infrequent working meetings with referring doctors. In virtually all surgical facilities, the referring doctors receive copies of the breast cancer patientʼs findings/discharge summary and in just under three quarters of the surgical facilities the operation notes are regularly sent to the referring doctor. In 72.5 % of the surgical facilities, the findings, treatment and aftercare of patients are discussed in person with the referring doctors.

Table 4 Collaboration with general practitioners (valid percentages).

| Yes, regularly | Yes, irregularly | No | No details given | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Does your breast cancer centre offer information sessions for doctors who refer patients to it? | 81.9 | 16.8 | 1.3 | 0 |

| Does your breast cancer centre offer further training meetings for doctors who refer patients to it? | 81.9 | 17.4 | 0.7 | 0 |

| Does your breast cancer centre offer working meetings with your referring doctors, e.g. to discuss problems? | 38.9 | 40.9 | 20.1 | 0 |

| Do the referring doctors receive copies of the findings/discharge reports relating to patients with breast cancer? | 98.7 | 0 | 1.3 | 0 |

| Are the findings, treatment and aftercare of patients discussed in person with the referring doctors? | 12.1 | 60.4 | 27.5 | 0 |

| Are the operation notes sent to the referring doctor? | 72.3 | 11.5 | 16.2 | 1 |

Quality circle with primary cooperation partners

The questions set out in Tables 5 to 7 are taken from the Governance, Leadership and Clinical Care Survey 8 and adapted to the situation in DKG-certified breast cancer centres operating quality circles with primary cooperation partners. Performance quality appears significantly more frequently on the agenda in quality circles with primary cooperation partners than financial performance (Table 5).

Table 5 Topics in the quality circle discussed with primary cooperation partners (valid percentages).

| How often … | Every meeting | Most meetings | Some meetings | Few/rare meetings | Never | No details given |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Is financial performance on the agenda for the quality circle with primary cooperation partners? | 0 | 6.8 | 23.6 | 56.8 | 12.8 | 1 |

| Is quality performance on the agenda for the quality circle with primary cooperation partners? | 39.6 | 44.3 | 14.1 | 2.0 | 0 | 0 |

Table 7 Subjects in the quality circle discussed with primary cooperation partners III (valid percentages).

| How often are the following items reviewed by the quality circle with the primary cooperation partners? | Quarterly or more frequently | At least annually | Less than annually or never | No details given |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital-acquired infections | 17.6 | 58.1 | 24.3 | 1 |

| Medication errors | 15.5 | 49.3 | 35.1 | 1 |

| Results of the parameter sheet | 14.1 | 83.9 | 2.0 | 1 |

| BQS/AQUA quality indicators | 13.4 | 75.2 | 11.4 | 0 |

| Patient satisfaction | 20.8 | 75.8 | 3.4 | 0 |

With regard to the amount of time spent over the course of the year in quality circles with primary cooperation partners, the aspects of quality and patient safety dominate those of finances (Table 6).

Table 6 Subjects in the quality circle discussed with primary cooperation partners II (valid percentages).

| 10 % or less | 11–20 % | 21–30 % | 31–40 % | More than 40 % | No details given | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Over the course of the year, what percentage of the time is typically spent on issues of financial performance in meetings of the quality circle with primary cooperation partners? | 78.8 | 14.4 | 4.1 | 2.7 | 0 | 3 |

| Over the course of the year, what percentage of the time is typically spent on issues of quality and safety in meetings of the quality circle with primary cooperation partners? | 2.7 | 14.2 | 26.4 | 14.2 | 42.6 | 1 |

The results of the parameter sheet and patient satisfaction are reviewed at least once a year in over 95 % of hospitals. Medication errors and hospital-acquired infections, on the other hand, are reviewed in 35 and 24 % respectively of surgical facilities less than once a year by the quality circle with primary cooperation partners (Table 7).

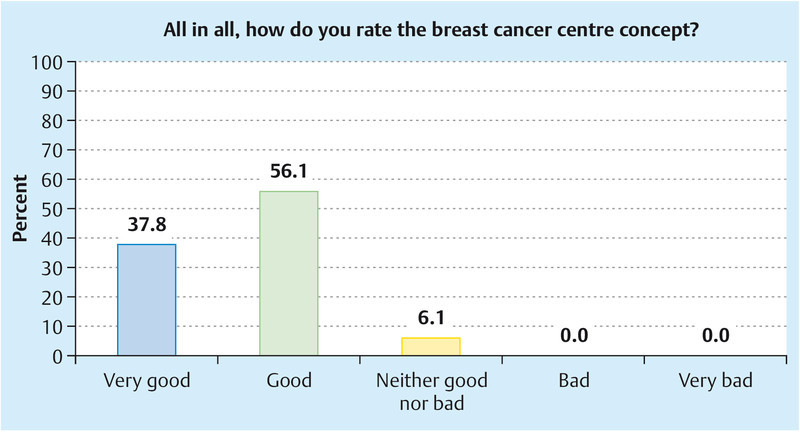

Assessment of the breast cancer centre concept and changes since its introduction

Over 90 % of those surveyed regarded the breast cancer centre concept as “good” or “very good”; none of them classed it as “poor” (Fig. 4). The majority of those surveyed see improvements in the quality of care of breast cancer patients both in their own breast cancer centres and in Germany as a whole (Table 8); none has seen a deterioration. With regard to the status of the centre, the psycho-oncological support and the quality of the tumour MDT, the large majority has again seen improvements. The improvements with regard to the working climate, communication with general practitioners and hospital managers, on the other hand, are rated significantly less highly. Just under 30 % of those surveyed reported a deterioration in the economic situation of their surgical facility since the introduction of breast cancer centres.

Fig. 4.

Assessment of the breast cancer centres concept (valid percentages).

Table 8 Assessment of developments since the introduction of breast cancer centres.

| Very much improved | Improved slightly | Unchanged | Worsened slightly | Very much worsened | No details given | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| How has the quality of care for patients with primary breast cancer changed overall at your breast cancer centre since the introduction of breast cancer centres? | 44.9 | 44.9 | 10.2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| How has the quality of care for patients with primary breast cancer changed in Germany as a whole since the introduction of breast cancer centres? | 45.6 | 50.3 | 4.1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| How has the economic situation of your surgical facility changed since the introduction of breast cancer centres? | 5.6 | 18.8 | 46.5 | 24.3 | 4.9 | 5 |

| How has the status of your surgical facility changed since the introduction of breast cancer centres? | 33.8 | 45.3 | 20.9 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| How has the contact between your surgical facility and general practitioners changed since the introduction of breast cancer centres? | 9.5 | 49.7 | 40.8 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| How has the communication between your surgical facility and the hospitalʼs management team changed since the introduction of breast cancer centres? | 6.9 | 39.3 | 49.7 | 3.4 | 0.7 | 4 |

| How has the working climate in your surgical facility changed since the introduction of breast cancer centres? | 5.5 | 32.2 | 56.2 | 5.5 | 0.7 | 3 |

| How has the quality of the psycho-oncological support at your surgical facility changed since the introduction of breast cancer centres? | 61.5 | 31.8 | 6.8 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| How has the quality of the tumour MDTs at your surgical facility changed since the introduction of breast cancer centres? | 55.1 | 32.0 | 12.2 | 0.7 | 0 | 2 |

Discussion

The aim of this survey was to investigate the acceptance of the concept of certified breast cancer centres from the perspective of key informants within a centre and to look at the impacts of certification on everyday clinical practice. As such, this paper represents a contribution to care research, the importance of which is still growing 9.

What does the concept of certified breast cancer centres constitute? The aim of the certification system is to improve the treatment and care of patients with breast cancer. This is based on cooperation between all of the relevant medical and surgical disciplines, professionals and patient representatives, i.e. the inter-disciplinary, multi-professional and cross-sector collaboration of everyone involved. This is the only way that quality-assured, comprehensive care can be achieved for patients. With certification, the implementation of these requirements in everyday clinical practice is required and verified.

The results of the survey show that the described concept of certified breast cancer centres is classed as good to very good by almost all participants of the survey (93.9 %). A closer look at the reasons that led to this opinion reveals first and foremost the key informantsʼ perception of an improved quality of care for patients since the introduction of breast cancer centres. This is true both in their own breast cancer centres (89.8 %) and in Germany as a whole (95.9 %). Over two thirds of the survey respondents have also seen an improvement in the status of their hospital as a result of the certification and the associated representation of quality to the outside world, for example through the use of a logo. Other aspects of the collaboration in a certified network, such as contact with general practitioners, have also improved according to the key informants surveyed (60 %).

One central module in the certification concept is the interdisciplinary collaboration of primary treating partners in tumour MDTs. It is, therefore, all the more pleasing that the majority of service providers regard the quality of the tumour MDT as very much improved (55.1 %) or improved (32.0 %) since certification. The quality of the psycho-oncological support, a key indicator of comprehensive patient support in relation to the certification concept but also, most importantly, as a reflection of a high-quality oncology care concept, has also increased significantly with certification.

Surprisingly, the working climate in most centres has remained unchanged (56.2 %) and in significantly more than a third of those surveyed it has improved slightly or a lot. This means that the efforts being made as part of the certification process are not having any negative impacts on the collaboration between treating partners. On the contrary, the clearly-defined treatment processes and responsibilities appear to support the quality of the collaboration.

In the survey responses that reflect the implementation of the concept of certified breast cancer centres, the workflows and content of quality circles are of particular note, at least allowing the assumption that aspects of compliance with guidelines are also being discussed in the quality circle 9. Fortunately, matters relating to quality and patient safety generally take up more time in the quality circles with primary cooperation partners than financial matters. However, it must be mentioned that in more than a third of hospitals, medication errors are never discussed in the quality circles or are discussed less than once a year. Even if medication errors may be analysed under different auspices in most hospitals, there is nonetheless still significant potential for risk management and patient safety in the certified breast cancer centres.

On a very positive note, the results of the parameter sheet and the results of the patient satisfaction survey are discussed in almost all centres at least once a year, and in some cases even quarterly. Parameters in the parameter sheet include the recommendations of the evidence-based guideline, the requirements on interdisciplinary collaboration, but also the requirements on the personal expertise of the service providers. This means that the primary treatment partners in a centre discuss their specific results on an interdisciplinary basis, allowing them to identify the strengths and weaknesses of their centre and consequently implement targeted measures aimed at improving quality. The same applies to patient satisfaction. The fact that the centres use the feedback from patients for interdisciplinary discussion in quality circles and are able to derive potential for improvement or positive affirmation, represents a very convincing implementation of the concept of certified breast cancer centres in everyday clinical practice.

The evaluations of the survey clearly show the extent of the voluntary initiative by the certified breast cancer centres, which forms the basis for the implementation of the concept of certification in order to achieve a constantly improving quality of care for patients from the perspective of the service provider, as well as the patient 1. These efforts have manifested themselves in very diverse ways in the development of the economic situation since the introduction of the breast cancer centre concept. Whereas around a third of the hospitals have noticed a slight deterioration in their economic situation, a quarter of certified centres have noticed an improvement. The relationship between improved cost effectiveness for health care and a partial deterioration in the economic situation for individual service providers during the course of the certification process has already been discussed elsewhere 10, 11. In order to offer a more detailed overview of the financial impacts, the Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft is planning to survey certified centres.

A further important point in the survey results is the average inpatient stay, which was specified as a minimum of 3 and a maximum of 10 days, the mean being 5.3 days. In order to satisfy the various needs of patients with regard to comprehensive information and preparation for the time following discharge from hospital 1 as effectively as possible, the further reduction of the length of hospital stay currently being discussed or even the direct transfer to the outpatient department should be avoided.

Summary

The aim of this survey was to investigate the acceptance of the concept of certified breast cancer centres from the perspective of key informants within a centre and to look at the impacts of certification on everyday clinical practice.

The results of the survey indicate that the described concept of certified breast cancer centres is classed as good to very good by almost all participants of the survey. From the perspective of the service provider, the key contributing perception in this case is the improved quality of care for patients since the introduction of breast cancer centres. Over two thirds of those surveyed also believed that the status of their hospital and the contact with general practitioners had improved as a result of certification. The quality of the tumour MDT and the quality of the psycho-oncological support provided are overwhelmingly regarded as having improved significantly.

Fortunately, matters relating to quality and patient safety take up more time in the quality circles with primary cooperation partners than financial matters. Whereas more than a third of the hospitals never discuss medication errors in quality circles, or do so less than once a year, almost all of the centres discuss the results of the parameter sheet at least once a year, and in some cases quarterly, as well as the results of the patient satisfaction survey, in order to implement targeted quality improvements.

The effects of certification on the economic situation are varied. For a precise analysis of this, the Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft is to carry out a survey on the financial background of the certified centres.

In summary, the results show wide acceptance of the concept of certified breast cancer centres, which is implemented with considerable input from the service provider in order to further improve the quality of the care given to patients.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest None.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Kowalski C Wesselmann S Kreienberg R et al. The patientsʼ view on accredited breast cancer centers: strengths and potential for improvement Geburtsh Frauenheilk 2012. in print [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dillman D A. New York: Wiley & Sons; 1978. Mail and Telephone Survey: the total Design Method. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freise D C Methodische Aspekte der Durchführung von Patientenbefragungen Köln: Forschungsbericht der Universität zu Köln200329–50. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petermann S. Rücklauf und systematische Verzerrungen bei postalischen Befragungen. ZUMA-Nachrichten. 2005;57:56–78. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rousseau D M. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Pub.; 1990. Assessing organizational Culture: the Case of multiple Methods; pp. 153–192. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poggie J J. Toward quality control in key informant data. Human Organization. 1972;31:23–30. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumar N, Stern L W, Anderson J C. Conducting interorganizational research using key informants. Acad Manage J. 1993;36:1633–1651. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jha A, Epstein A. Hospital governance and the quality of care. Health Affairs. 2010;29:182–187. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lux M P, Fasching P A, Loehberg C R. et al. Health services research and health economy – quality care training in gynaecology, with focus on gynaecological oncology. Geburtsh Frauenheilk. 2011;71:1046–1055. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1280435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wöckel A, Varga D, Kurzeder C. et al. Leitlinienkonformität bei der Therapie des Mammakarzinoms. Geburtsh Frauenheilk. 2009;69:611–616. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lux M P, Hildebrandt T, Bani M R. et al. Gesundheitsökonomische Aspekte und finanzielle Probleme in den zertifizierten Strukturen des Fachgebietes. Gynäkologe. 2011;44:816–826. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.