Abstract

Hospital managers and the heads of medical departments are nowadays being faced with ever increasing demands. It is becoming difficult for some small hospitals to find highly experienced or even experienced medical staff, to provide specific health-care services at break-even prices and to maintain their position in competition with other hospitals. On the other hand, large hospitals are facing enormous pressure in the investment and costs fields. Cooperation could provide a solution for these problems. For an optimal strategic exploitation of the hospitals, their direction could be placed in the hands of a joint medical director. However, the directorship of two hospitals is associated both with opportunities and with risks. The present article illustrates the widely differing aspects of the cooperation between a medical centre and a general hospital providing standard care from both a theoretical point of view and on the basis of practical experience with an actual cooperation of this type in Heidelberg.

Key words: gynaecology, epidemiology, abortion

Abstract

Zusammenfassung

Krankenhausträger und Chefärzte sehen sich heutzutage wachsenden Anforderungen ausgesetzt. Es wird für einige kleinere Kliniken schwieriger, leitende und in Weiterbildung arbeitende ärztliche Mitarbeiter zu finden, bestimmte Gesundheitsleistungen kostendeckend anzubieten und sich in dem Konkurrenzkampf mit anderen Kliniken zu behaupten. Große Kliniken wiederum sehen sich einem immensen Investitions- und Kostendruck ausgesetzt. Kooperationen könnten eine Lösung der Probleme herbeiführen. Dabei kann zur optimalen strategischen Ausrichtung der Häuser die Leitung dieser in der Person eines gemeinsamen Chefarztes vereint werden. Die Leitung zweier Krankenhäuser birgt jedoch Risiken und Chancen zugleich.Dieser Artikel beschreibt die facettenreichen Aspekte einer Kooperation zwischen einem Haus der Maximalversorgung und einem Haus der Grund- und Regelversorgung theoretisch und aus den praktischen Erfahrungen einer gelebten Kooperation in Heidelberg.

Schlüsselwörter: Gynäkologie, Epidemiologie, Abort

Introduction

Over the past years interested physicians have been able to observe a nation-wide trend in the appointment of new heads of medical departments. In general hospitals providing standard care, leading positions that become available are no longer advertised and filled with new applicants but are rather occupied on a part-time basis by a department head or hospital director of a nearby medical centre 1, 2, 3. A partnership is formed between the hospitals which are in effect in competition with one another. The different financial bases of the hospitals may remain unaffected but can possibly, in individual situations, also lie in one set of hands.

When the medical directorship of two hospitals lies in the hands of one senior physician head while the financial bases are provided by two systems, both synergies and conflicts can arise. This development carries both positive and negative aspects, chances and dangers which will be formulated theoretically and illustrated on the basis of our own experience.

General Considerations

The cooperation

From the viewpoint of the hospital management there are in principle several reasons to implement a cooperation and simultaneous joint medical directorship of two hospitals working at different health-care levels:

The desire of the “smaller” general hospital for a strategic union with a medical centre as guarantee for its continuing existence,

Diagnosis-appropriate and adapted patient care with economic advantages for both hospitals,

Increased capacity in the inpatient field,

Lack of or unsuitable applications after advertising the position of senior physician,

Preparation for the take-over of the smaller hospital by the larger one.

Advantages and disadvantages of the personnel cooperation can be found on both sides and are listed in Table 1. Planning security and a strategic linkage to a medical centre at a time when uneconomically operating smaller hospitals are being shut down appears to be the major motivation for the cooperation from the view point of the “smaller” hospital.

Table 1 Advantages and disadvantages of the personnel partnership of medical centres with general hospitals.

| Advantages for the medical centre | Advantages for the general hospital |

|

|

| Disadvantages for the medical centre | Disadvantages for the general hospital |

|

|

For fields like surgery and internal medicine it can be very reasonable to concentrate smaller operations and certain patients (e.g., geriatric patients) in the general hospital in order to reserve the more expensive beds of the medical centre for complex operations (e.g., transplantation surgery) or intensive care patients (e.g., care of cardiac patients). This does not hold for gynaecology because practically all operations, except for the interdisciplinary operations for ovarian cancer, can be performed in all gynaecological departments. The result of this is that all gynaecological departments are effectively in competition with each another. Thus when the medical direction of two hospitals is in one set of hands a distinction between the patient collectives is only difficultly possible and is frequently associated with deficits on the one side or the other, unless, of course it is possible to attract new patients for both hospitals.

The divided head physician

An elemental requirement for the double head physician position is a clear delineation of the interests of the two hospitals. Whether or not a trustful cooperation is possible depends on two principle questions: whether both departments must work in a profitable manner or whether the one has more income at the cost of the other and the losses of the other side can be compensated. This question arises especially when the two hospitals have different financial foundations. In such a case divergent interests arise since the partners may simultaneously be competitors for one and the same patient collective. Clear agreements, preferably in written form, are then necessary in order to avoid conflicts of interest from the very beginning. Compensatory payments can then be considered which may become possible due to a decline in the case mix of one of the hospitals.

The divided head physician must think about further rules concerning liability insurances and on the usage of existing cooperations, e.g., in the framework of certified subsections of the hospital (breast centre, genital centre, pelvis centre, etc.).

Whether or not the increased workload of the divided head physician results in an increased salary depends upon the agreed contract. Of particular relevance are the right to treat private patients and the civil servant status of the head physician.

On site representation

Since the divided head physician cannot of course be present in two places at the same time deputies must be appointed in both hospitals who are able to make all decisions on behalf of the head physician in his/her absence. They must possess the necessary expertise to solve all difficult gynaecological and obstetric problems on their own. A high degree of mutual trust is necessary. In most cases the new head physician will bring own his/her deputy to the new hospital and only rarely will a senior physician from the “old” team be named as deputy. The motivation to accept such a position is probably closely correlated with the senior physicianʼs own prospective career planning and the particular financial reimbursement.

Furthermore, this deputy must be registered with the local medical association as a physician empowered to train others in order that the continuing medical training responsibilities are fulfilled even when the head physician is not present in the hospital.

Medical colleagues

The senior physicians and assistant physicians at the two hospitals may work separately without any contact with the staff of the other hospital or alternatively work according to a rotation system in both hospitals. Of course it must be assured that the individual physicians really are in a position to fulfil the medical spectrum of both hospitals (e.g., perinatology in level 1 centre) and that the hours of duty (possibly active vs. standby duty) are comparable 4, 5.

The head physician also has responsibilities for further education. Here, especially synergies can arise since deficits in training at the one hospital can be filled by further training at the other one. Accordingly, by means of a rotation system a comprehensive further education for all assistant physicians can be achieved and, possibly, also specialist qualifications may be gained. In times of reduced applications in our specialty, in particular, this can be advantageous for the general hospital. The physicians of the medical centre can also benefit from this since they can learn interventions in the general hospital that are very rarely encountered in the highly specialised medical centre.

Medical liability insurance

The liability insurance company must be informed of the change in circumstances. They must agree to the new situation. It appears to be particularly important to exactly describe the rotation positions of the deputies, senior physicians and assistant physicians and to have them checked. The liability insurance company must also be informed about rotation systems for all other medical personnel 6.

Patient satisfaction

As a rule the patients react positively to these changes. They welcome the application of modern standards of a medical centre in the general hospital. Furthermore, the patientsʼ trust in the general hospital can be increased when the foundations for certification (e.g., minimum number of treatments) are fulfilled by the cooperation. Thus, smaller hospitals may also obtain certification (e.g., breast centre or urogenital centre) which would otherwise not have been possible 7, 8.

When the capacity of one of the two departments is reached, it is possible to fall back on the other one as a solution in the patientsʼ best interest.

Cost effectiveness

The cost structure of a hospital determines whether a medical service can be carried out in a profitable manner. Up to now it is usually very difficult for most hospitals to calculate whether individually defined treatments can actually be carried out economically. Nevertheless, good controlling together with the head physician can establish which services in each hospital are not economically worthwhile. This must not inevitably mean that the same situation exists in the other hospital since this may have a different cost structure. Thus it must be determined at regular intervals just which services should be offered in each hospital. For the sake of orientation one could propose that major gynaecological cancer operations are more economic in the medical centre than in the general hospital since, in such cases in general, complex cases can be better absorbed by the capacity. In the general hospital, as a rule, rather urogynaecological, endoscopic, reconstructive operations or cosmetic operations as self-paid services can be offered.

Illustration of an Existing Cooperation

Cooperation between the surgical departments of Salem Hospital of the Evangelische Stadtmission Heidelberg gGmbH (Krankenhaus Salem) and the University Hospital has been in existence since 2003 under one professor and head physician (Prof. Dr. M. Büchler) 3, 9. In 2007 a successor was needed in the department of gynaecology and obstetrics. From the point of view of Salem Hospital the reasoning for cooperation was to establish a strategic position. In spite of the fact that Heidelberg has the lowest birth rate in Germany it maintains four departments of gynaecology and obstetrics. Since May 2008 the university gynaecological clinic and the department of gynaecology and obstetrics of Salem hospital are under the medical direction of Prof. Dr. Christof Sohn.

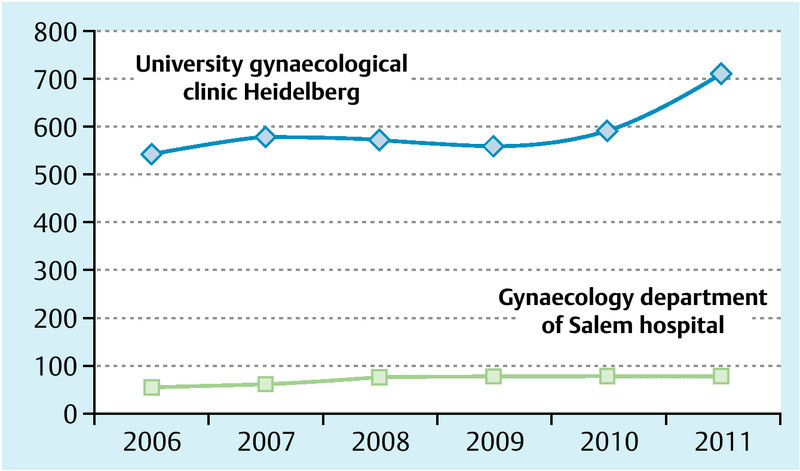

Heidelberg university gynaecological clinic is a specialist medical centre with 103 beds, more than 5000 inpatients and ca. 1400 births per year. Gynaecological oncology (breast centre with ca. 700 primary cases per year) and perinatology deserve mention as particular specialties (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Number of primary breast cancers per year.

Salem hospital is an academic teaching hospital of Heidelberg University with 238 beds maintaining, besides the gynaecological department, also surgical, internal medicine, urology and anaesthesiological departments. The hospital and its departments have always enjoyed a good reputation among the inhabitants of Heidelberg. The department of gynaecology and obstetrics has 42 beds (21 for gynaecology, 18 for obstetrics). With the sponsorship of the Dietmar-Hopp-Stiftung a nearby 19th century villa has been lavishly converted to an exclusive maternity station on 3 floors. This was opened simultaneously with the appointment of the new director.

Our concept provided for the following central points:

Increase in the number of births, starting from ca. 700 in 2007 with a continuously decreasing tendency, by a consequent positioning as individual, family obstetrics services while maintaining university hospital standards and an exclusive cooperation partner.

Extension of the certified breast centre to include Salem hospital.

Establishment of an interdisciplinary cooperation with the surgical and internal medicine departments for the treatment of urinary incontinence and prolapse complaints.

Performance of smaller surgical interventions as well as vaginal and urogynaecological operations in Salem hospital.

Performance of gynaecological-oncological interventions in the university clinic with endoscopic standards.

Creation of an adequate external image.

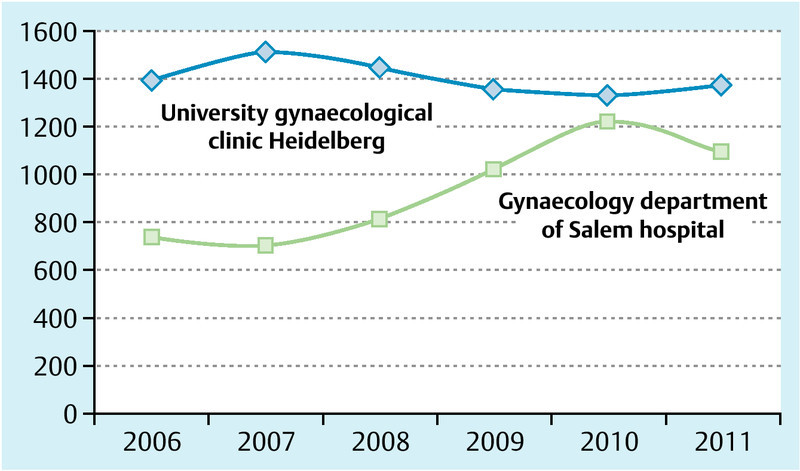

For optimisation of the obstetric procedures, after a short observation period the previously applied standards were completely revised. Numerous routines were examined and changed in cooperation with the medical and nursing staff and adapted to the contemporary wishes of couples (episiotomies only in cases of an absolute indication, umbilical blood sampling, less invasive measures, alternative means for inducing labour, reduction of the number of caesarean sections, pleasant environment, late visiting hours, baby photography). Care of the newborn babies in the maternity unit was transferred to the neonatology department of the university hospital (department head: Prof. Dr. J. Pöschl), who also took over responsibility for the emergency care in the delivery room and the reanimation training programmes held every 3 months for the medical team. Furthermore, high-risk pregnancies and births as well as deliveries before 36 + 0 weeks of pregnancy were cared for in the university clinic. The newly renovated maternity villa in addition provides spacious rooms, adroit partitioning, practical furniture, large bathrooms, pleasant breakfast room and optimal prerequisites for rooming as if in a four-star hotel. Through these measures a good acceptance of the new concept was soon achieved so that the number of births has almost doubled up to 2010 (1283 births; Fig. 3), the rate of caesarean sections has declined from 40 % to less than 30 % and episiotomies were only performed on 19 % of the patients (previously 40 %).

Fig. 3.

Number of births (spontaneous and vaginal operative births and caesarean section deliveries) per year.

In surgical gynaecology the certified breast centre could be extended to Salem hospital so that all university cooperation partners of the university gynaecology clinic can also serve Salem hospital (pathological institute, radiology, radiotherapy, plastic surgery [Berufsgenossenschaftliche Klinik Ludwigshafen], psychooncology). Breast care nurses can also be trained in Salem hospital. Each patient is presented pre- and postoperatively to an interdisciplinary tumour board. In this way, those patients who wish to be treated in a religiously-based hospital or those who do want to be treated in a university hospital can still profit from the high standards of a certified centre. The number of breast cancer operations in Salem hospital has remained constant.

For gynaecological oncology it was decided that patients could receive diagnostic treatment in Salem hospital (stereoscopy, curettage, ionisation, biopsies, etc.), whereas, with the patientʼs agreement, operative treatment of disease would be carried out in the university clinic since the latter can offer laparoscopic procedures and in the near future also robot-assisted surgery. Furthermore, surgical flexibility is greater in the university clinic.

In cooperation with the urological department of Salem hospital, a urogynaecological surgery has been created and is headed by a female senior physician. Preoperatively or for consultation, many patients are referred here by general practitioners or to the surgery in the university gynaecological clinic. Operations on the patients are performed in Salem hospital by the urogynaecologist Dr. Maleika (AGUB III), who is a senior physician at the university clinic and deputy head physician at Salem hospital.

For optimisation of the external image, the press centre of the university hospital has created an appropriate internet web site, the contents of which were initially prepared by the medical staff. The previously prepared brochures have been completely revised with the help of the press centre. A parent information evening has been established and is held twice each month; this is announced in the offices of general practitioners, in the internet and in local newspapers in appropriate optical forms. These parent information evenings are not only well adapted to the requirements of women in Heidelberg but also encompass midwives and sisters of the maternity villa so that couples are introduced to a team representing the mutually established vision of obstetrics at Salem hospital. Finally the authors visited also all office-based gynaecologists in the area to explain the new concept to them.

A rotation of the assistant physicians in training was initiated. Surprisingly, experience showed that the rotation between the two hospitals did not occur with equal motivation. Physicians of the university clinic have consciously chosen their career planning within a medical centre and rather view a temporary switch to a general hospital sceptically, whereas the colleagues in Salem hospital show a high motivation to gain new experiences. Furthermore, from the view point of the university physicians there is the fear that the absence could lead to scientific disadvantages.

Discussion

Our specialty gynaecology and obstetrics is facing difficult times. Many departments are suffering from declining case numbers, especially in obstetrics. Thus, new concepts are needed to counter this trend, before political interventions occur, for example, in the form of the definition of minimum case numbers. Cooperations – as described here – may represent one option to work together against this trend.

The introduction of new diagnostic, operation and systemic treatment methods into gynaecological oncology will lead to the creation of specialist centre even if at the moment there is the widespread opinion that all gynaecological tumours can be operated and treated classically in all departments 10. This ignores the fact that endoscopic procedures, robot-assisted surgery, intraoperative radiotherapy and special systemic therapies cannot all be offered by one clinic. Even so, the patients have accepted the creation of specialised oncological centres and prefer to undergo treatment in them 11. In future there will rather be further specialisations in gynaecological oncology.

Furthermore our specialty must assert itself in competition with other specialties in which alternatives to our procedures can be performed. For example, this is the case in urogynaecology or surgery. We can counter this threat, for example, by demonstrable competence in the respective field and by interdisciplinary dialogues.

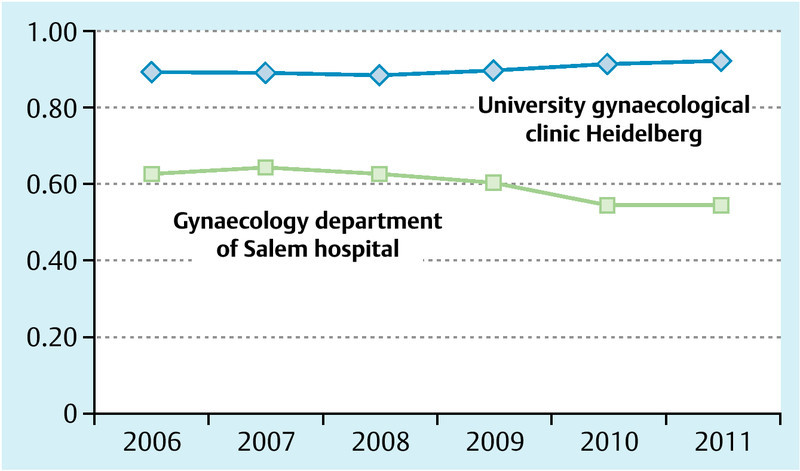

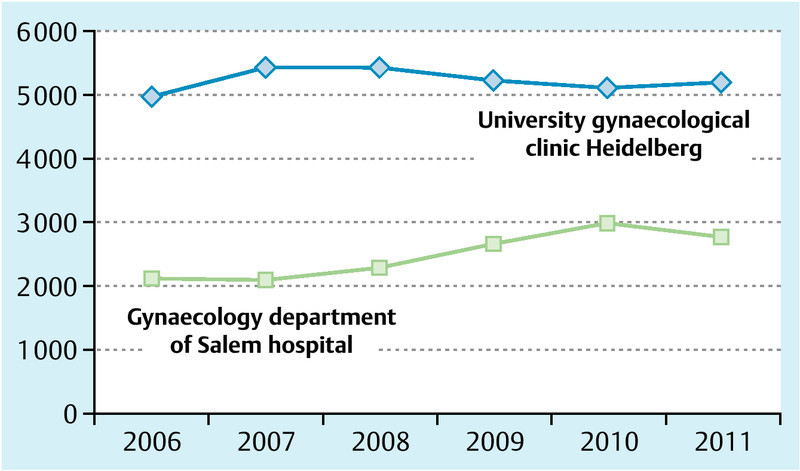

By cooperation between two departments of gynaecology and obstetrics, the two hospitals can be strategically guided within a region and thus ensure the continuing existence of both departments. In Heidelberg this procedure resulted in a stimulation of both clinics. The number of births increased in Salem hospital through the new standards, university cooperation partners and a well-conceived publicity without impinging on the patient collective of the university clinic specialising in high-risk obstetrics. In gynaecology an increased number of patients with gynaecological tumours could be recruited for the university clinic. Thus the case-mix indices in both hospitals remain constant with increasing case numbers (Fig. 1 and 2). Certainly some of these developments would have occurred without the cooperation (e. g., increasing number of births due to the renovated maternity villa in Salem hospital; increasing number of gynaecological oncology patients in the university clinic). However, it is not certain that these developments would have been equally effective without the additional supporting synergisms (exclusive cooperation with the university paediatric clinic; structuring of the patient collective). Numerous developments would not have been possible at all.

Fig. 1.

Case-mix index (CMI) per business year; the decline in Salem hospital correlates with the increasing number of births.

Fig. 2.

Inpatient cases of the gynaecological-obstetrics department per year.

As a limitation, we have also noted an in part critical point of view by some office-based gynaecologists who now refer fewer patients than previously to the two hospitals. This appears to be due, among others, to the fear that university medicine could develop an excessively large dominance in the region. A responsible, humane and highly qualified treatment of our patients will hopefully convince these colleagues in future of the advantages and utility of the partnership.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest None.

Supporting Information

German supporting information for this article

References

- 1.Metzelder M L, Engelmann C, Bottländer M. et al. Cooperation model between an university clinic and a peripheral paediatric surgical department. Zentralbl Chir. 2008;133:559–561. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1077019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Egger B, Schmid S W, Schäfer M. et al. 2-year evaluation of a cooperation model between a surgical university clinic and a general hospital. Chirurg. 2001;72:30–36. doi: 10.1007/s001040051264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Welsch T, von Frankenberg M, Simon T. et al. Hospital cooperation models. Safeguarding optimized patient care, medical training and resource utilization. Chirurg. 2012;83:274–279. doi: 10.1007/s00104-011-2254-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mautner E. et al. Medical and psychosocial risk factors for depression and decreased quality of life in pregnancy and postpartum. Geburtsh Frauenheilk. 2010;70:298–303. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Billmann M K, Rath W, Beinder E. Pregnancies at an advanced maternal age: results from Zurich and review of the literature. Geburtsh Frauenheilk. 2010;70:273–280. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hellmers C, Krahl A, Schucking B. Decisions in the delivery room: how do obstetricians come to their decisions? Geburtsh Frauenheilk. 2010;70:553–560. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strauss A. et al. Emergencies in obstetrics. Geburtsh Frauenheilk. 2010;70:R22–R36. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diedrich K, Strowitzki T, Kentenich H. Position paper – current state of reproductive medicine in Germany. Geburtsh Frauenheilk. 2010;70:355–360. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1298358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.von Frankenberg M, Schmitz-Winnenthal H, Bornemann T. et al. [Project “Partnership” – university surgical departments and hospitals for basic and regular medical care. Directing cooperation for the future] Chirurg. 2007;78:368–373. doi: 10.1007/s00104-006-1266-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lux M P, Fasching P A, Loehberg C R. et al. Health services research and health economy – quality care training in gynaecology, with focus on gynaecological oncology. Geburtsh Frauenheilk. 2011;71:1046–1055. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1280435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lux M P, Fasching P A, Bani M R. et al. Marketing of breast and perinatal centers – are patients familiar with the product “specialized centers and certification”? Geburtsh Frauenheilk. 2009;69:321–327. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

German supporting information for this article