Abstract

Introduction

Percutaneous interventional procedures in the renal arteries are usually performed using a femoral or brachial vascular access. The transradial approach is becoming more popular for peripheral interventions, but limited data exists for renal artery angioplasty and stenting.

Methods

We have analyzed the clinical, angiographic and technical results of renal artery stenting performed from radial artery access between 2012 and 2013. The radial artery anatomy was identified with aortography using 100 cm pig tail catheter. After engagement of the renal artery ostium with a 6F Multipurpose or 6F JR5 guiding catheter, the stenosis was passed with a 0.014” guidewire followed by angioplasty and stent implantation.

Results

In 27 patients (mean age: 65.4 ± 9.17) with hemodynamically relevant renal artery stenosis (mean diameter stenosis: 77.7 ± 10.6%; right, n = 7; left, n = 20), interventional treatment with angioplasty and stenting was performed using a left (n = 3) or right (n = 24) radial artery access. Direct stenting was successfully performed in 13 (48%) cases, and predilatations were required in ten cases 10 (37%). Primary technical success (residual stenosis <30%) could be achieved in all cases. The mean contrast consumption was 119 ± 65 ml and the mean procedure time was 30 ± 8.2 min. There were no major periprocedural vascular complications and in one patient transient creatinine level elevation was observed (3.7%). In one patient asymptomatic radial artery occlusion was detected (3.7%).

Conclusion

Transradial renal artery angioplasty and stenting is technically feasible and safe procedure.

Keywords: carotid stenosis, carotid stenting, radial approach

Introduction

The radial artery (RA) is getting to be the preferred access site for coronary interventions worldwide and the access site is very popular for many peripheral angiographies and interventions as well [1, 2]. Percutaneous renal intervention (PRI) is usually performed using the femoral or brachial vascular access [3] but limited data exists for renal artery angioplasty and stenting performed from RA [4–5]. The major advantage of the RA access is the extreme low rate of vascular complication rate [6]. Several vascular complications were reported after transradial (TR) angioplasty, but many of them are asymptomatic due to dual blood supply of the hand [6–9]. The aim of the study was to analyze the angiographic and clinical results of the renal artery stenting from our database; we describe our technique and provide a review of the literature.

Methods

Study population

We have analyzed the clinical, angiographic and technical results of renal artery stenting performed from radial artery access between 2012 and 2013. Several parameters were applied to evaluate the potential advantages or drawbacks of TR access: access site cross over, rate of access site and renal complications, major adverse events (MAE) at 1-month and consumption of angioplasty equipment. The access site was an operator decision.

Medication

All patients were pretreated with the traditional TR cocktail (5000 U Heparin and 2.5 mg Verapamil) and Aspirin plus Clopidogrel. A bolus of Heparin was given to reach the dose of 100 U/kg Heparin.

Angioplasty technique

After local anesthesia, the RA was punctured with a dedicated TR needle and 6F sheath (Terumo). The RA anatomy was identified in AP or left anterior oblique 20 view with aortography using a 5F 100 cm long pig tail catheter. The cannulation of the renal artery was performed with a 100 cm long 6F JR5 or a 125 cm long 6F Multipurpose (Cordis) guiding catheter (the available guiding length was estimated after the angiography with the 100 cm long pig tail catheter) (Fig. 1A–B). In some cases the “no-touch technique” was used when the ostium was severely diseased [10] (Fig. 2A–D). The renal artery lesion was passed with a conventional coronary guidewire (0.014 BMW or Whisper Extra support, 180 cm) or when the support was insufficient a 0.018 Steelcore (Abbot) was used for buddy wire during the intervention. After performing a road map imaging the lesion was stented directly with a dedicated renal artery stent Express SD (Boston Sci, 150 cm long shaft) or Herculink (Abbot Co, 135 cm long shaft). In calcified arteries or when the stent did not pass the lesion and predilatation was performed with a non-compliant monorail balloon (135–150 cm long) (Fig. 1C–D). In the case of fibro muscular dysplasia or stent restenosis balloon angioplasty was performed primarily.

Fig. 1.

A: High grade stenosis of the left renal artery and selective cannulation with a Multipurpose 6F guiding catheter. B: Direct stenting with a 6 × 18 mm Herculink stent. C: Final result

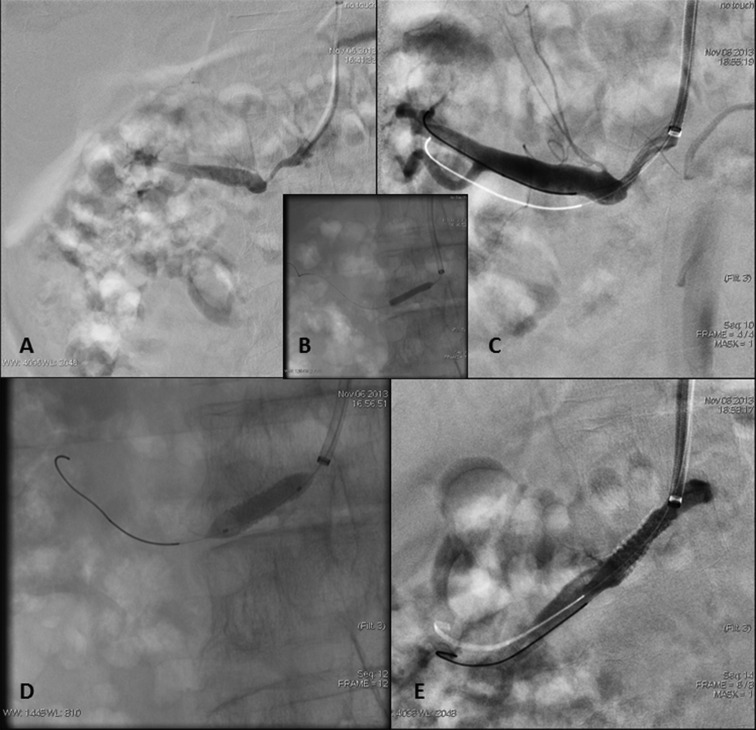

Fig. 2.

A–B: Calcified high grade ostial left renal stenosis and cannulation with a Multipurpose 125 cm diagnostic catheter over a 6F 120 cm sheathless guiding using the telescoping technique. C–D: Predilatation with a Quantum 4 × 20 mm balloon and stenting with a 6.5 × 18 mm Herculink stent. E: Final result

Postoperative treatment

After the procedure the sheath was removed immediately and hemostasis was achieved with a tourniquet for 6 hours. We did not apply a dedicated hemostatic device. All patients were mobilized immediately.

Post procedural follow-up

The RA was investigated after the procedure with palpation and in the case of impalpable RA, the artery was investigated with Doppler Ultrasound. The creatinine level and the blood pressure was controlled 3 days after the intervention.

Quantitative angiography

Angioplasty was performed according to the standard clinical practice. The vessels and the lesions were analyzed by using a computerized quantitative analysis system (General Electric, Innova 3100). Measurements were obtained with digital caliper method.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analysis was performed with a commercially available software Statistica 8.0 (StatSoft Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA). Continue variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation and range, and were compared using unpaired t-tests. Probability values lower than 0.05 were considered to be significant.

Results

Demographic and clinical data are summarized on Table I. The indication of the intervention was resistant hypertension in 18 patients (66.7%) and worsening renal failure in 9 patients (33.3%).

Table I.

Demographic and clinical data

| Demographic and clinical data | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 65.4 ± 9.1 |

| Male | 22 (81.5) |

| Hypertension | 27 (100) |

| Renal insufficiency | 9 (33.3) |

| – Hemodialysis | 1 (3.7) |

| Dyslipidaemia | 26 (96.3) |

| Active smokers | 10 (37) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 8 (29.6) |

| Severe obesity | 6 (22.2) |

| Coronary artery disease | 7 (25.9) |

| – Previous PCI | 4 (14.8) |

| Peripheral artery disease | 17 (62.9) |

| – Previous PTA | 10 (37) |

Procedural data are summarized in Table II. In 27 patients (mean age: 65.4 ± 9.17) with hemodynamically relevant renal artery stenosis (mean diameter stenosis: 77.7 ± 10.6%, right; n = 7; left, n = 20), interventional treatment with angioplasty and stenting was performed using a left (n = 3) or right (n = 24) radial artery access. The cross over rate was 0%. Direct stenting was successfully performed in 13 (48%) cases, and predilatations was required in ten cases 10 (37%). Primary technical success (residual stenosis <30%) could be achieved in all cases. The mean contrast consumption was 119 ± 65 ml.

Table II.

Angiographic and procedural data

| Angiographic and procedural data | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Lesion site | |

| Right renal artery | 8 (29.6) |

| Left renal artery | 19 (70.4) |

| Lesion location | |

| Isolated ostial | 7 (25.9) |

| Proximal shaft | 19 (70.4) |

| Middle shaft | 1 (3.7) |

| Distal shaft | 0 (0) |

| Quantitative measurements and angiography | |

| Lesion length (mm) | 14.36 ± 3.25 |

| Reference diameter (mm) | 5.89 ± 0.80 |

| Stenosis diameter (%) | 76.68 ± 10.56 |

| Severe calcification | 7 (25.9) |

| Severe tortuosity | 0 (0) |

| Visible thrombus | 0 (0) |

| Angiographic result of the intervention | |

| Residual stenosis <30% with good flow | 27 (100) |

| Equipments | |

| Diagnostic catheter / procedure (%) | 27 (107.4) |

| Guide catheter / procedure (%) | 25 (92.6) |

| Sheathless guiding (%) | 2 (7.4) |

| Guide wire 0.35 (%) | 28 (103.7) |

| Guide wire 0.14 (%) | 29 (107.4) |

| Balloon / procedure (%) | 13 (48.1) |

| Stent used / procedure (%) | 24 (88.8) |

Complications are summarized in Table III. Procedural complications: In one patient the stent was dislodged from the ostium during balloon removal, but it was successfully mobilized and parked in the external iliac artery. Renal complications: In the investigated population renal failure was not detected, however, in one patient the creatinine and carbamide nitrogen level was increased after the intervention (3.7%). Temporary hematuria was observed in one patient (3.7%). Major adverse event was not detected in the investigated population. Vascular complications: There were no major periprocedural major vascular complications. Minor vascular complication was detected in three patients (11.1%) (1 asymptomatic radial artery occlusion and 2 transient spasm).

Table III.

Complications

| Complications | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Procedural complications | |

| Stent dislodgement | 0 (0) |

| Other | 0 (0) |

| Renal complications | |

| Renal failure | 0 (0) |

| Transient creatinine elevation | 1 (3.7) |

| Access complications | |

| Major | |

| Symptomatic RAO | 0 (0) |

| Compartment syndrome | 0 (0) |

| Other | 0 (0) |

| Minor | |

| Spasm | 2 (7.4) |

| Asymptomatic RAO | 1 (3.7) |

| Perforation without compartment sy | 0 (0) |

| MAE | |

| Death | 0 (0) |

| Urgent bypass operation or PTA | 0 (0) |

| AMI | 0 (0) |

Clinical results

Clinically systolic blood pressure was improved from 162.5 ± 22.2 to 151 ± 21.9 (p = ns). Serum creatinine values dropped from 170.3 ± 124.4 to 167.7 ± 119 (p = ns).

Discussion

Atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis (RAS) can be associated with three main clinical syndromes such as renovascular hypertension; ischemic nephropathy; and cardiac syndromes (refractory heart failure, unstable angina, and sudden-onset pulmonary edema). The treatment of the RAS can be optimal medical or interventional treatment. Many studies has confirmed the potential of the PRI to decrease the hypertension [11] and to reverse the progression of renal failure [12], but some studies show no benefit in patients presented with RAS [13] for this reason patient selection has a paramount importance due to the high number of non-responsive patients and because the procedure is associated with frequent vascular access complications and worsening renal failure [11–14].

Vascular complications

Femoral access complications occur more frequently in patients with peripheral artery disease [15] and renal dysfunction [16] and both diseases are associated with RAS and make these patients more vulnerable for femoral complications [17]. Due to high number of the access complications of the PRI, many efforts were made to decrease the incidence of their frequency, such as introducing new alternative access sites (brachial, radial), small new low profile 6F compatible devices, routine use of closure devices [4–5]. BA access is associated with high risk of vascular and nerve complications [18], but despite the disadvantages of the BA access this is the second access site for many interventionalist for PRI, due to the large size of the brachial artery, which makes the puncture easy, while it is not spasmogenic and allows the use of 6–7F large sheaths and the traditional catheter length allows the use of nearly all devices used for PRI. Another potential access site for PRI is the radial and ulnar way which has shown in many coronary and peripheral studies an extremely low rate of access site complications [1, 2, 6].

Renal complications

The most severe complication associated after PRI is the worsening renal failure and the potential cause can be macro and microembolisation during the intervention and contrast nephropathy. Distal embolization can be prevented with careful guiding catheter engagement of the ostium with “no-touch technique” [10] and with using distal embolic protection devices [14]. TR and TB access allows relatively atraumatic cannulation of the renal artery ostia especially in cases when the renal artery has a downward origin and potentially decrease the chance of distal embolization.

Disadvantages

On the low rate of early (spasm, perforation, brachial artery dissection, distal embolization) and late [pseudo aneurysm formation, radial artery occlusion (RAO)] reported vascular complications of radial approach it is important to note that most of them are asymptomatic due to dual blood supply of the hand [6–9]. Symptomatic complications causing critical hand ischemia can occur when the forearm circulation is not complete and the radial artery occludes or when the brachial or subclavian artery is damaged [19]. RAO is reported in 3–5% in different studies [6–9], and as the radial artery must be preserved for further interventions and Cimino fistulae, all preventive measures must be taken to prevent RAO including fast and atraumatic puncture, intra-arterial administration of Heparin and verapamil, and the use of non-occlusive bandage [20]. Additionally in patients with renal insufficiency, in whom the below-the-knee arteries are frequently affected by atherosclerosis and calciphylaxis symptomatic RAO might occur more easily than in normal population [21].

Advantages

The potential of immediate mobilization of the patients increase the patient comfort and shorten the hospitalization, but the most important advantage of the technique is the extreme low rate of vascular complications [1].

Technical aspects

Puncture and traversing the radial and brachial artery is the same as during coronary procedures and is important that the operator be aware of the radial artery anomalies especially radial artery loops to avoid complications. The catheter advancement in the ascending aorta is sometimes difficult, especially from the right radial artery, but the pig tail catheter can be advanced in the ascending aorta with Terumo hydrophilic wire in LAO60 projection easily. There are two techniques for guide-catheter advancement: direct and indirect engagement. We prefer the direct catheter advancement, when the ostium is not diseased, but in the case of high-grade ostial lesions or several adjacent aortic disease, there is a risk of guide catheter dissection, distal embolization therefore in these patients we prefer the “no-touch technique”. A long 5F diagnostic catheter (125 cm) is telescoped through a shorter 6F guide catheter the long 300 cm 0.014–0.018 GW is placed over the stenosis, and after removing the diagnostic catheter a long monorail balloon is used for predilatation. We are following the trends which suggest a movement forward 0.014 GWs and long coronary monorail balloons for PRI. The one caveat to keep in mind is that radial access requires the use of balloons and stents with long shaft lengths (135 or 150 cm). We prefer 135–150 cm long balloon expandable stents for PRI, but sometimes these 135 cm long stents has not sufficient length in 125 long guiding catheter, therefore the Y connector must be removed and the stent must be implanted under roadmap image. Another option is to use a long 120 cm sheathless guiding (Asahi) and 125 long diagnostic catheter for no-touch technique (Fig. 2). The left radial artery is generally preferred for renal angiography and interventions due to shorter distance and the avoidance of crossing the carotid vessels, but we prefer the right radial approach because the right radial approach is more comfortable for the operator.

Study limitations

The main limitation of the study is the retrospective study design and the lack of femoral control group. Another limitation of the study that the right and left radial approach was not investigated in the study.

Conclusion

Transradial renal artery angioplasty and stenting is technically feasible and safe. Further randomized studies are needed to confirm the superiority over the traditional femoral artery access.

Abbreviations

- RA:

radial artery

- FA:

femoral

- BA:

brachial artery

- PRI:

percutaneous renal intervention

- RAO:

radial artery occlusion

- RA:

radial artery

- TR:

transradial

Funding Statement

Funding sources: None.

Footnotes

Author's Contributions: ZR, KT and ZJ introduced the study idea. ZR and BN performed the interventions. KT performed the off-line analysis and acquired the angiography images. NK and SN helped in the interpretation of the results and statistical analysis. ZR wrote the manuscript. KH and BM added clinical discussion to the manuscript. ZR and BN reviewed the manuscript. Finally, all authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Conflict of interest: The authors have no real or perceived conflicts of interest to disclose.

Contributor Information

Zoltán Ruzsa,

Károly Tóth,

Zoltán Jambrik,

Nándor Kovács,

Sándor Nardai,

Balázs Nemes,

Kálmán Hüttl,

Béla Merkely,

References

- 1.Caputo RP, Tremmel JA, Rao S, Gilchrist IC, Pyne C, Pancholy S, Frasier D, Gulati R, Skelding K, Bertrand O, Patel T. Transradial arterial access for coronary and peripheral procedures: executive summary by the Transradial Committee of the SCAI. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2011 Nov 15;78(6):823–839. doi: 10.1002/ccd.23052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Staniloae CS, Korabathina R, Coppola JT. Transradial access for peripheral vascular interventions. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2013 Jun 1;81(7):1194–1203. doi: 10.1002/ccd.24608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaukanen ET, Manninen HI, Matsi PJ, Söder HK. Brachial artery access for percutaneous renal artery interventions. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1997 Sep-Oct;20(5):353–358. doi: 10.1007/s002709900167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scheinert D, Bräunlich S, Nonnast-Daniel B, Schroeder M, Schmidt A, Biamino G, Daniel WG, Ludwig J. Transradial approach for renal artery stenting. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2001 Dec;54(4):442–447. doi: 10.1002/ccd.1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sanghvi K, Coppola J, Patel T. Cranio-caudal (transradial) approach for renal artery intervention. J Interv Cardiol. 2013 Oct;26(5):530–535. doi: 10.1111/joic.12053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kolluri R, Fowler B, Nandish S. Vascular access complications: diagnosis and management. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2013 Apr;15(2):173–187. doi: 10.1007/s11936-013-0227-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanei Y, Kwan T, Nakra NC, Liou M, Huang Y, Vales LL, Fox JT, Chen JP, Saito S. Transradial cardiac catheterization: a review of access site complications. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2011 Nov 15;78(6):840–846. doi: 10.1002/ccd.22978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stella PR, Kiemeneij F, Laarman GJ, Odekerken D, Slagboom T, van der Wieken R. Incidence and outcome of radial artery occlusion following transradial artery coronary angioplasty. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1997 Feb;40(2):156–158. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0304(199702)40:2<156::aid-ccd7>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uhlemann M, Möbius-Winkler S, Mende M, Eitel I, Fuernau G, Sandri M, Adams V, Thiele H, Linke A, Schuler G, Gielen S. The Leipzig prospective vascular ultrasound registry in radial artery catheterization: impact of sheath size on vascular complications. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2012 Jan;5(1):36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2011.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feldman RL, Wargovich TJ, Bittl JA. No-touch technique for reducing aortic wall trauma during renal artery stenting. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 1999 Feb;46(2):245–248. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-726X(199902)46:2<245::AID-CCD27>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dorros G, Jaff M, Mathiak L, He T. Multicenter Palmaz stent renal artery stenosis revascularization registry report: four-year follow-up of 1,058 successful patients. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2002 Feb;55(2):182–188. doi: 10.1002/ccd.3050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramos F, Kotliar C, Alvarez D, Baglivo H, Rafaelle P, Londero H, Sánchez R, Wilcox CS. Renal function and outcome of PTRA and stenting for atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis. Kidney Int. 2003 Jan;63(1):276–282. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00734.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wheatley K, Ives N, Gray R, Kalra PA, Moss JG, Baigent C, Carr S, Chalmers N, Eadington D, Hamilton G, Lipkin G, Nicholson A, Scoble J ASTRAL Investigators. Revascularization versus medical therapy for renal-artery stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2009 Nov 12;361(20):1953–1962. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0905368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cooper CJ, Haller ST, Colyer W, Steffes M, Burket MW, Thomas WJ, Safian R, Reddy B, Brewster P, Ankenbrandt MA, Virmani R, Dippel E, Rocha-Singh K, Murphy TP, Kennedy DJ, Shapiro JI, D'Agostino RD, Pencina MJ, Khuder S. Embolic protection and platelet inhibition during renal artery stenting. Circulation. 2008 May 27;117(21):2752–2760. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.730259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jeremias A, Gruberg L, Patel J, Connors G, Brown DL. Effect of peripheral arterial disease on in-hospital outcomes after primary percutaneous coronary intervention for acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2010 May 1;105(9):1268–1271. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aziz EF, Pulimi S, Coleman C, Florita C, Musat D, Tormey D, Fawzy A, Lee S, Herzog E, Coven DL, Tamis-Holland J, Hong MK. Increased vascular access complications in patients with renal dysfunction undergoing percutaneous coronary procedures using arteriotomy closure devices. J Invasive Cardiol. 2010 Jan;22(1):8–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilms G, Marchal G, Peene P, Baert AL. The angiographic incidence of renal artery stenosis in the arteriosclerotic population. Eur J Radiol. 1990 May-Jun;10(3):195–197. doi: 10.1016/0720-048x(90)90137-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alvarez-Tostado JA, Moise MA, Bena JF, Pavkov ML, Greenberg RK, Clair DG, Kashyap VS. The brachial artery: a critical access for endovascular procedures. J Vasc Surg. 2009 Feb;49(2):378–385. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.09.017. discussion 385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ruzsa Z, Molnár L, Szabó G, Merkely B. Catheter-induced brachial artery dissection during transradial angioplasty. J Vasc Access. 2013 Oct-Dec;14(4):392–393. doi: 10.5301/jva.5000148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanmartin M, Gomez M, Rumoroso JR, Sadaba M, Martinez M, Baz JA, Iniguez A. Interruption of blood flow during compression and radial artery occlusion after transradial catheterization. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2007 Aug 1;70(2):185–189. doi: 10.1002/ccd.21058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruzsa Z, Tóth K, Berta B, Koncz I, Szabó Gy, Jambrik Z, Varga I, Hüttl K, Merkely B, Nemes A. Allen’s test in patients with peripheral artery disease. Central European Journal of Medicine. 2014;9(1):34–39. doi: 10.2478/s11536-013-0178-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]