Abstract

The radical S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) superfamily of enzymes catalyzes an amazingly diverse variety of reactions ranging from simple hydrogen abstraction to complicated multistep rearrangements and insertions. The reactions they catalyze are important for a broad range of biological functions, including cofactor and natural product biosynthesis, DNA repair, and tRNA modification. Generally conserved features of the radical SAM superfamily include a CX3CX2C motif that binds an [Fe4S4] cluster essential for the reductive cleavage of SAM. Here, we review recent advances in our understanding of the structure and mechanisms of these enzymes that, in some cases, have overturned widely accepted mechanisms.

S-Adenosylmethionine (SAM) was initially characterized as an electrophilic methyl donor in a wide variety of cellular methylation reactions. However, as early as 1970, an enzyme, lysine 2,3-aminomutase, that required SAM but that did not involve methylation was identified.1−3 The similarity of the reaction catalyzed by this enzyme to the adenosylcobalamin-dependent aminomutases led to the proposal for a radical mechanism, which has since been verified by numerous studies. The key step is the reductive cleavage of SAM into a 5′-deoxyadenosyl radical (Ado•) and methionine as an initiating step (Figure 1A). The highly reactive Ado• intermediate allows the substrate to be readily activated toward reaction through stereoselective H-abstraction.4 This initial discovery drove a surge of interest into this family of enzymes and more broadly, into the field of radical enzymology.5

Figure 1.

(A) General mechanism for reductive cleavage of SAM into 5′-deoxyadenosyl radical and methionine. (B) Structure of pyruvate formate lyase showing the wider, incomplete β/α barrel fold to accommodate this enzyme’s larger substrate—a peptide shown in magenta. (C) Lysine-2,3-aminomutase possesses a complete, closed β/α barrel that surrounds the small substrate, lysine, shown in magenta.

Bioinformatics methods have played an important role in identifying the existence of at first several hundred, and eventually thousands, of related proteins in all kingdoms of life, which came to be known as the radical SAM superfamily.6,7 A host of radical SAM enzymes have now been biochemically characterized,8−10 identifying their crucial role in a diverse range of biological functions including cofactor synthesis,11 enzyme activation, DNA repair, protein and nucleic acid modification, and primary metabolism.12,13 The chemistry catalyzed by radical SAM enzymes proceeds via a remarkably wide range of mechanisms; the reactions catalyzed include carbon methylation, sulfur insertion, oxidation, methylthiolation, and complex carbon skeleton rearrangements including ring formation and isomerization.

An important unifying characteristic of radical SAM enzymes is the presence of a CX3CX2C motif, conserved in almost all known radical SAM enzymes, which coordinates a [Fe4S4] cluster. The cluster is ligated by the three cysteine residues of this motif, which leaves one of the four iron atoms unligated (the “unique” iron), and therefore free to coordinate SAM.14 SAM is then reductively cleaved following electron transfer from the [Fe4S4] cluster, forming the adenosyl radical that initiates the various reactions mentioned above by abstraction of a hydrogen atom from the substrate.15 Many SAM enzymes are also now known to contain a second “auxiliary” [Fe4S4] cluster. In some cases, the second cluster participates directly in the reaction, for example, as the source of the inserted sulfur atom in the biotin synthase reaction.16 For most, however, the function of the second cluster is still unclear, and speculation has centered on the second cluster acting as an electron donor in these cases.17

The increasing availability of crystal structures has allowed researchers to identify other conserved features of the radical SAM superfamily (Figure 1B, C). Early structural studies, including those of HemN and BioB, identified the position of the active site [Fe4S4] cluster within a β8α8 (TIM-barrel) fold.18,19 As more structures became available, the presence of a “partial” β6α6 TIM-barrel was found to be a feature of many enzymes. It appears that enzymes that bind large substrates, such as pyruvate formate-lyase activating enzyme (PFL-AE), adopt the more open partial TIM-barrel structure to allow substrate access to the active site.

Although an enormous amount has been learned about radical SAM enzymes since the discovery of lysine 2,3-aminomutase, the shear breadth and complexity of the reactions catalyzed, together with the technical difficulties associated with working on these highly oxygen-sensitive enzymes, means there is still much that remains to be understood about these enzymes. The structure and mechanisms of many known radical SAM enzymes remain to be elucidated. Many more are known only from sequence alignments, their substrates, the type of reaction catalyzed and physiological roles within the organism are completely unknown.

In this review, we present an overview of selected radical SAM enzymes for which there have been significant recent advances in our understanding of their mechanisms; these are categorized broadly by reaction type. First, we discuss the carbon-centered methylations catalyzed by Cfr and RlmN and the unusual methylthiolation reactions involving the chemically challenging conversion of C–H to C–SCH3 catalyzed by the methylthiotransferases MiaB, RimO, and MtaB. Next, we review some of the diverse and recently identified carbon–carbon bond forming enzymes exemplified by Tyw1 which modifies tRNA bases, MqnE, which is involved in menaquinone biosynthesis, and F0 synthase, which is involved in coenzyme F420 biosynthesis. Lastly we discuss recent advances in our understanding of radical SAM enzymes involved in catalyzing increasingly complex rearrangements, represented by spore photoproduct lyase (SPL), the [Fe,Fe] hydrogenase maturase enzyme, HydG, and the molybdopterin biosynthesis enzyme, MoaA.

2. Methylations and Methylthiotransferases

Radical SAM enzymes catalyze a variety of methylation reactions that are distinct from conventional nucleophilic methylations of electronegative atoms.20 These enzymes are typified by methylation on carbon atoms and require two equivalents of SAM—one serving as the methyl donor, the other to generate Ado• needed in the reaction. Here, we discuss two subsets of methylases exemplified by RlmN and Cfr, and MiaB and RimO for which recent experiments have revealed new and unanticipated mechanisms.

2.1. Cfr and RlmN

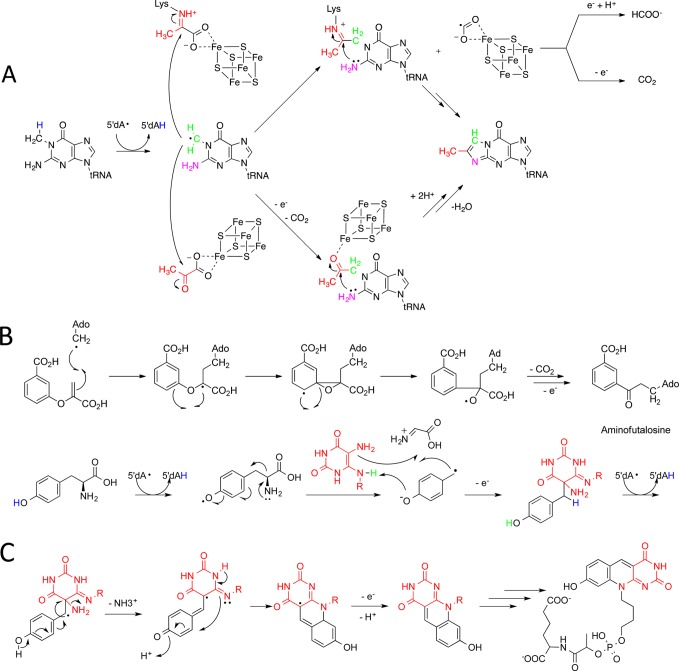

Methylation of rRNA plays an important role in the regulation of translation and in antibiotic resistance in certain bacteria.21 Radical SAM-dependent RNA methylations are characterized by methylation on carbon; the best understood enzymes are Cfr and RlmN that methylate the C2 (RlmN) and C8 (Cfr) amidine carbons of A2503 in the bacterial 23S rRNA.15,22 Both proteins contain a single [4Fe-4S] cluster23 and consume two equivalents of SAM per turnover; one molecule provides the methyl group whereas the other serves to generate Ado•. It was assumed that the reaction would be initiated by Ado• abstracting hydrogen from the amidine carbon to activate it toward methylation; however, it has recently been shown that the reaction proceeds quite differently.

Studies employing labeled SAM and mutated enzymes24,25 together with the crystal structure of RlmN26 support a mechanism whereby the enzyme is first methylated on Cys355. Ado• next abstracts a hydrogen atom from the methylated cysteine, as evidenced by the fact that when (methyl-d3)-SAM is used one deuterium is incorporated into Ado-H.24 The thiomethylene radical thus generated attacks the amidine carbon to form, after one-electron oxidation and loss of a proton, a transient rRNA–protein adduct. The covalent adduct is resolved by attack of a Cys 118 to form a disulfide bridge and the methylated rRNA (Figure 2A). Isotopic labeling confirms that when deuterated SAM is used only 2 deuterium atoms remain in the methyl group and that the third proton derives from the solvent.15,24

Figure 2.

(A) Proposed mechanism for carbon-centered methylation catalyzed by RlmN; the enzyme is first conventionally methylated on Cys355 by SAM; the reaction is then initiated by hydrogen abstraction from the thiomethyl group by Ado•. (B) Proposed mechanism for methylthiolation catalyzed by MiaB. Methylation by SAM of a persulfide ion (derived from the pentasulfide bridge) ligated to the unique iron of the auxiliary [Fe4S4] cluster precedes the radical SAM chemistry to generate Ado•, which abstracts hydrogen from the substrate. The substrate radical then attacks the methylated sulfur atom to afford methythiolated product. (C) Crystal structure of holo-TmRimO. (Right) ribbon diagram showing UPF0004 domain (red), radical SAM domain (blue) and TRAM domain (pink). (Left) A pentasulfide bridge links the two unique iron atoms in each of the Fe4S4 clusters, with iron and sulfur shown in orange and yellow.

2.2. MiaB

Chemical modifications of tRNAs have been discovered in all organisms. In particular, modifications of nucleotides surrounding anticodons of tRNAs are believed to maintain translational efficiency and fidelity.27,28 One such modification is the thiolation of tRNA nucleotides that is accomplished by either of two distinct strategies. In one, the cysteine desulfurase enzyme IscS replaces a nucleoside oxygen with sulfur; in the other, methylthiolation is catalyzed by the radical SAM enzyme MiaB,29 a rare case in which the tRNA is modified through a redox reaction.30

Methylthiotransferases belong to a subset of radical SAM enzymes that contain two [Fe4S4] clusters. In addition to the central radical SAM domain, they possess an N-terminal UPF0004 (uncharacterized protein family 0004) domain that harbors the second [Fe4S4] cluster, ligated by a CX34–36CX28–37C motif,13 and a C-terminal “TRAM” domain, (the name deriving from TRM2 and MiaB).13,31−35 Recently, a crystal structure of the related methylthiotransferase, RimO, discussed below, has been solved, confirming that the cysteine motif coordinates the second [Fe4S4] center.36

MiaB was the first tRNA-modifying enzyme identified to contain an [Fe4S4] cluster.37 It introduces a methylthiol group to the modified tRNA base i6A, forming 2-methythio-N-6-isopentenyladenosine (ms2i6A) at position 37 of tRNAs that read codons starting with uridine.12 Labeling experiments show that one SAM provides the methyl group yielding SAH as the byproduct; while the other produces Ado•.32 To initiate the reaction, Ado• generated by reductive cleavage of SAM is proposed to activate the tRNA substrate (i6A37) by abstracting a H atom from C-2 of the nucleotide (Figure 2). It was thought that thiolation of i6A37 would occur next, with the second iron sulfur cluster providing the sulfur atom, as has been shown for the sulfur insertion reactions catalyzed by BioB.31 This would be followed by methyl transfer from the second SAM, producing MeS2i6A37.20

However, recent work shows that methyl transfer from SAM to the enzyme does not depend on Ado• radical formation and can proceed in the absence of substrate tRNA—suggesting that sulfur insertion may not precede methyl transfer.29 Furthermore, when MiaB was treated with SAM in the absence of a reducing agent, subsequent denaturation of the protein with acid resulted in the release of methanethiol. These results suggested that the methyl group is transferred to an acid-labile sulfur on the protein.29 Although this would be consistent with methyl transfer to one of the bridging μ-sulfido ions of the N-terminal [Fe4S4] cluster, a recent study reports multiple turnovers of MiaB with exogenous sulfide.36 Furthermore, 2-dimensional EPR spectroscopy (HYSCORE) demonstrated that sulfur-containing cosubstrates such as methanethiol can directly chelate to the second cluster, which remains intact.36 Mechanistic rationalization of these observations has been greatly aided by the recently obtained crystal structure of the related methylthiotransferase, RimO, as discussed below.

2.3. RimO

RimO is responsible for post-translational modification of Asp88 of the ribosomal protein S12 in E. coli.38 This protein is proposed to play a role in maintaining translational accuracy.33,34 Similar to MiaB, RimO is a bifunctional system that in this case adds a methylthiol group to the β-carbon of an Asp88 residue (Figure 2). The crystal structure of apo-RimO revealed that the acidic TRAM domain is likely to be the binding site for S12.13 RimO function is also dependent on the protein YcaO; it is suggested that YcaO optimizes the interaction between RimO and S12.39

Sequence homology to MiaB initially suggested methylthiolation may occur in a manner similar to MiaB, with one cluster generating Ado• to activate the substrate and the other cluster donating a sulfur atom to the substrate.32,33 However, the recently determined crystal structure of holo-Tm RimO shows a remarkable pentasulfide bridge linking the two unique iron atoms in each of the clusters (Figure 2).36 The structure, along with mechanistic and spectroscopic studies similar to those described for MiaB,36 provide strong evidence that the second cluster remains intact during turnover.

A mechanism that explains these observations starts with incorporation of exogenous sulfide into the pentasulfide bridge between the iron–sulfur clusters. This is followed by methyltransfer from SAM to form a methyl-terminated persulfide chain (Figure 2); the details of how the pentasulfide bridge is cleaved and methylated remain to be determined. Abstraction of hydrogen from the substrate by Ado• activates the substrate for methylthiolation. Next transfer of the methylthio group to the substrate occurs and finally a further electron is lost from the substrate, possibly to the second iron–sulfur cluster, to complete the catalytic cycle.20,36

2.4. Methylthiotransferases in Eukaryotes and Archaea

The hyper-modified adenosine base 2-methylthio-N6- threonylcarbamoyladenosine (ms2 t6A) is found in bacterial, archaeal, and eukaryotic cells.35 The methylthio group is introduced by the methylthiotransferase subfamilies designated as MtaB in bacterial cells and eMtaB in eukaryotic and archaeal cells. These enzymes catalyze the methylthiolation of tRNA at position 37 on N6-threonylcarbamoyladenosine (t6A). The gene CDKAL1, encodes the eMtaB enzyme in humans; interestingly a deficiency in eMtaB reportedly leads to abnormal insulin synthesis and a predisposition to type 2 diabetes.40 This observation lends further support to the emerging view that radical SAM enzymes play important roles in the metabolism of higher eukaryotes as well as microbial organisms. Biochemical analysis of YqeV, a bacterial homologue of CDKAL1, demonstrated the presence of two iron sulfur clusters and that the conserved cysteine motif coordinating the Fe–S cluster is required for tRNA modification, suggesting that these enzymes function similarly to MiaB and RimO.35

3. Complex C–C Bond-Forming Reactions

Radical SAM enzymes catalyze many unusual carbon–carbon bond-forming reactions that proceed through radical intermediates. Here, we review some of the more recent insights into the mechanisms of several enzymes that expand upon the repertoire of radical SAM-catalyzed reactions. These include the hyper-modification of tRNA bases; a new biosynthetic pathway to menaquinone (vitamin K) that operates in some bacteria, and in the biosynthetic pathway for coenzyme F420.

3.1. Tyw1

Wyosine is a tricyclic base found in tRNAPhe of archaea and eukaryotes at position 37, adjacent to the anticodon.41 Its large cyclic structure may improve fidelity, due to its strong base-stacking interactions that reduce the flexibility of the tRNA.42 Twy1 catalyzes the conversion of N-methylguanosine to 4-demethylwyosine as the second step in production of wybutosine, the wyosine derivative found in baker’s yeast. It was recently demonstrated that the two additional carbon atoms are supplied by the α- and β-carbons of pyruvate (Figure 3A).43

Figure 3.

(A) Two mechanisms have been proposed for the conversion of N-methylguanosine to 4-demethylwyosine catalyzed by Tyw1. (top) A lysine stabilizes intermediates by forming a Schiff base with pyruvate; the auxiliary cluster functions as a redox center.43 (bottom) Coordination of the auxiliary cluster promotes the reaction of the substrate radical with pyruvate facilitates cyclization.44 (B) Proposed mechanism for aminofutalosine synthesis catalyzed by MqnE. The key first step involves a radical Michael addition of Ado• to the chorismate-derived cosubstrate; subsequent rearrangement and oxidative decarboxylation produces aminofutalosine. (C) Proposed mechanism for the reaction of tyrosine and diaminouracil catalyzed by F0 synthase. The mechanism involves the abstraction of hydrogen from tyrosine and the release of a dehydroglycine, producing a reactive 4-oxidobenzyl radical, which adds to diaminouracil. A second round of radical chemistry initiates formation of the tricyclic deazaflavin, F0, that in further steps is converted to F420.

Tyw1 from Methanocaldococcus jannaschii was cocrystallized with SAM, revealing a (β/α)6 “partial” TIM barrel structure typical of radical SAM enzymes that act on large substrates.42 Apart from the catalytic [Fe4S4] cluster, which is bound by the α-amino and α-carboxylate groups of SAM, the enzyme contains a second [Fe4S4] cluster (separated from the first by 11 Å) that is essential for enzymatic function. However, its mechanistic role is remains unclear. In eukaryotes, the enzyme has an additional flavodoxin domain that may be involved in shuttling electrons to the iron sulfur cluster.41

Two mechanisms have been proposed for Tyw1,43,44 (Figure 3A) one proposes the formation of a Schiff base to pyruvate formed through a conserved lysine residue, the other coordination of pyruvate to the second [Fe4S4] cluster. Both mechanisms start with hydrogen abstraction from N-methylguanosine by Ado• to activate the substrate followed by homolytic cleavage of the C1–C2 bond of pyruvate. The first mechanism envisages that the second cluster functions to either oxidize or reduce the pyruvate carboxylate group during the reaction (it is not known whether the carboxylate is released as CO2 or formate). Next, transamination of the Schiff base to the amino-group of N-methylguanosine would form the cyclized the product. The second mechanism proposes instead that the second [Fe4S4] cluster functions as a Lewis acid to facilitate cyclization and dehydration to form 4-demethylwyosine, without formation of a Schiff base intermediate. Further investigation is needed to discriminate between these potential mechanisms.41

3.2. MqnE

Menaquinone is used in place of ubiquinone by some bacteria in the electron transfer chain, whereas in animals, as vitamin K, it functions as a coenzyme in carboxylation reactions important in bone formation and blood clotting. Biosynthetic pathways for menaquinone synthesis have been well-characterized, but some bacteria lack the canonical genes for these pathways. Streptomyces coelicolor uses a newly discovered pathway to produce menaquinone that begins with the conversion of chorismate to 3-[(1-carboxyvinyl)oxy]benzoic acid by MqnA.45 The radical SAM enzyme MqnE then catalyzes the conversion of 3-[(1-carboxyvinyl)oxy]benzoic acid to aminofutalosine, releasing methionine and CO2 as byproducts (Figure 3B). Aminofutalosine is subsequently converted to menaquinone by MqnB, MqnC, and MqnD, and other uncharacterized enzymes.45

Interestingly, unlike all other radical SAM enzymes, the mechanism by which MqnE converts 3-[(1-carboxyvinyl)oxy]benzoic acid into aminofutalosine does not involve hydrogen abstraction by Ado•. Rather, it involves the addition of Ado• to a double bond (Figure 3B). The UV–visible spectrum of the enzyme demonstrates a characteristic 415 nm absorbance band, indicative of a [Fe4S4] cluster. Recently, the role of MqnE was elucidated by anaerobically incubating chorismate SAM and dithionite with MqnA and MqnE. Whereas MqnA alone catalyzed the dehydration of chorismate, the enzymes together produced the aminofutalosine.45

3.3. F0 Synthase

F0 is a precursor to the deazaflavin cofactor F420, used by various enzymes including those involved in energy metabolism, DNA repair and antibiotic synthesis, in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes.46 Recent studies on purified F0 synthase from Thermobifida fusca using labeled substrates have shown that F0 is formed from diaminouracil and tyrosine, rather than 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate as had been proposed.47 The enzyme from Thermobifida fusca (FbiC) is a single protein that interestingly possesses two CX3CX2C-containing radical SAM domains, suggesting that two different [Fe4S4] clusters are responsible for producing Ado• during the course of the reaction.47 Consistent with this, 2.5 equiv of 5′-deoxyadenosine were formed for each F0 synthesized.

F0 synthase has also been studied from cyanobacteria and archaea where it comprises two subunits, CofG and CofH, each containing one [Fe4S4] cluster.47 The two subunits appear to catalyze successive steps in the overall reaction. Thus, incubation of CofH with diaminouracil, tyrosine, SAM, and reductant gave a small molecule product that could subsequently be incubated with CofG, SAM, and reductant to yield F0. A mechanism for the formation of F0 that is consistent with these findings is shown in Figure 3C. As originally proposed,47 fragmentation of the tyrosyl radical generates a glycyl radical and the quinone methide intermediate that subsequently reacts with diaminouracil. However, in the light of recent work on hydG (discussed in section 4.2), we present a mechanism involving fragmentation of the tyrosyl radical to give a 4-oxidobenzyl radical that seems equally plausible. Further experiments will be needed to distinguish between these two possibilities.

4. Complex Carbon Skeleton Rearrangements

Radical SAM enzymes have been shown to catalyze complex carbon skeleton rearrangements in the areas of DNA repair and cofactor biosynthesis. In this section, we review new mechanisms proposed for spore photoproduct lyase (SPL) and for the biogenesis of the CO and CN ligands in the FeFe-hydrogenase H cluster, which derive from tyrosine through the action of the radical SAM enzyme HydG. We also summarize recent studies on the molybdenum cofactor biosynthesis enzymes MoaA and MoaC, which clarify their roles in converting GTP into the polycyclic pyranopterin structure.

4.1. Spore Photoproduct Lyase

Exposure to ultraviolet radiation results in dimerization of adjacent thymine bases in DNA, which can have deleterious effects on DNA replication and transcription. Spore photoproduct lyase (SPL), a radical SAM enzyme found in bacteria and commonly studied in Bacilus subtilis, repairs these dimers and thus reverses the damage.48 The enzyme contains the canonical radical SAM [Fe4S4] cluster and adopts and incomplete, (β/α)6 TIM barrel fold (Figure 4).49

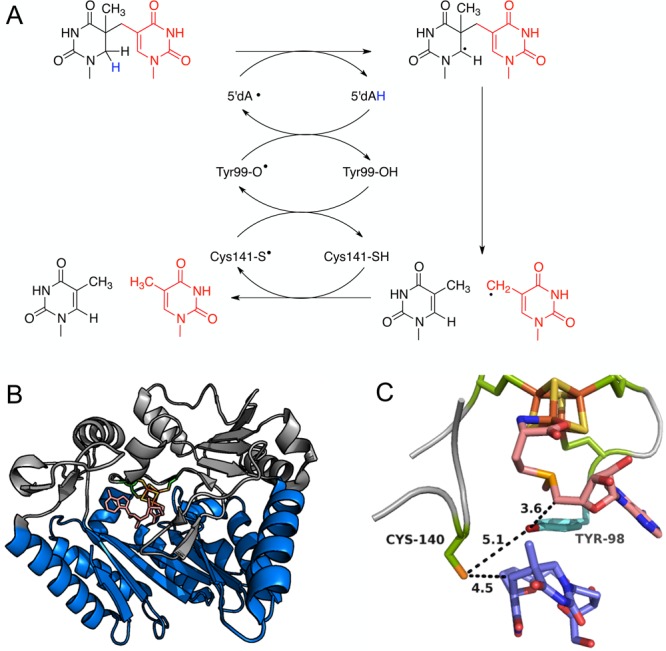

Figure 4.

(A) Newly proposed mechanism for SPL accounting for radical regeneration by a hydrogen atom transfer pathway involving Cys140 and Tyr98; (B) SPL enzyme structure with partial TIM barrel fold shown in blue and substrate in brown; (C) close-up view of SPL active site with [Fe4S4] in yellow/orange, conserved cysteine residues in green, SAM in pink, thymine dimer in blue, and Tyr98 in cyan.

The established mechanism for SPL starts with the formation of an Ado• radical, which abstracts a hydrogen atom from C-4 of the dihydrothymine moiety of the dimer. The resulting thyminyl radical then fragments to restore one thymine residue and generate a methyl-based radical on the second thymine residue, which abstracts a hydrogen back from Ado-H to regenerate Ado• and the restore second thymine residue.48 This mechanism predicts that the hydrogen atom first abstracted by the Ado• radical should be returned to one of the thymine residues. However, a recent study using deuterated dithymine substrates revealed that the mechanism is more complex. Surprisingly, when the hydrogen atom first abstracted by the Ado• is replaced by deuterium, no deuterium is observed in the thymine product, suggesting that the originally abstracted hydrogen is not returned to thymine.50

Site-directed mutagenesis studies show that a conserved cysteine residue, Cys140, (that does not coordinate the [Fe4S4] cluster) is required for SPL function. The crystal structure of SPL (Figure 4) shows this cysteine residue to be closer to the 3′-thymidine residue than SAM, suggesting that Cys140 is the true hydrogen atom donor to the thyminyl radical. Cys140 alanine and serine mutants were not catalytically active but structurally the similar to wild-type SPL. The S–H bond dissociation energy is low enough to donate hydrogen to the thyminyl radical, but the O–H bond dissociation energy is too high, explaining why cysteine but not serine can act as a hydrogen source.49 Indeed, mutation of Cys140 to alanine traps the enzyme before the final step allowing the allylic thyminyl radical to be trapped with dithionite as the thymine sulfinic acid derivative.51

For the reaction to be catalytic with respect to SAM, Ado• must eventually be regenerated. Tyr98, is located between Cys140 and SAM in the enzyme active site and is a potential intermediate in the hydrogen transfer pathway (Figure 4). The Tyr98Phe mutant enzyme was still functional, but has a 3-fold lower reaction rate, suggesting this is not an obligate step.52 The tyrosine O–H and cysteine S–H have similar bond dissociation energies, indicating that abstraction of a hydrogen atom from Tyr98 by the cysteinyl radical is feasible. In contrast, the C–H bond dissociation energy is much higher so that transfer of hydrogen from Ado-H to either a tyrosyl or cysteinyl radical would be unfavorable. It has been hypothesized that this energy difference could be offset by coupling the abstraction of hydrogen from Ado-H to the regeneration of SAM.52

4.2. Hydrogenase Maturing Enzyme, HydG

HydE and HydG are radical SAM enzymes that are involved in the maturation of the [FeFe]-hydrogenase (HydA), which plays a central role in hydrogen metabolism in various anaerobic bacteria. HydA contains a complex metal cluster in which a [Fe4S4] cluster is linked through a cysteine ligand to a di-iron cluster, the H-cluster, which is the site of hydrogen generation. The H-cluster is ligated by CN, CO, and dithiolate ligands; recent studies have shown that it is synthesized separately and then inserted into HydA53 through the actions HydE, HydF, and HydG. HydE and HydG are radical SAM enzymes that contain significant sequence similarities to biotin synthase (BioB) and tyrosine lyase (ThiH), respectively.

HydG is the better understood enzyme; it has been shown to use tyrosine as a substrate in the synthesis of CN– and CO ligands, while producing p-cresol as the biproduct. In addition to the Ado• generating [Fe4S4] cluster, the enzyme contains a C-terminal [Fe4S4] cluster that, based on characterization of mutants lacking the cysteine ligands to the cluster, appears to be the site of CO and CN– production. A recent study found that that disruption of the C-terminal [Fe4S4] cluster does not affect the enzyme’s affinity for SAM but drastically reduces the affinity for tyrosine. Kinetic analysis of the iron–sulfur cluster mutants indicated that the C-terminal cluster is not needed for tyrosine cleavage to p-cresol but is required for conversion into CN– and CO.54

It is generally considered that the HydG reaction is initiated by abstraction of the phenolic hydrogen from tyrosine by Ado•; however, the subsequent steps in the mechanism are less clear. In particular, cleavage of the tyrosyl radical could occur heterolytically, to produce dehydroglycine and a 4-oxidobenzyl radical, or homolytically, to produce glycyl radical and quinmethide as intermediates.55,54 The mechanism of cleavage has implications for how CN– and CO are produced from the glycyl fragment.

Recently, EPR spectroscopy, together with various 2H, 13C, and 15N-labeled tyrosine substrates, has been used to identify HydG reaction intermediates and a detailed reaction mechanism was proposed, accounting for the role of both clusters.56 The results support a mechanism where cleavage of the tyrosine radical occurs heterolytically to form a 4-oxidobenzyl radical and dehydroglycine, in which dehydroglycine is bound to the C-terminal cluster. Electron and proton transfer reduces the 4-oxidobenzyl radical to p-cresol. Lastly, by a mechanism that is still unresolved, dehydroglycine is cleaved and dehydrated to give the CO and CN– ligands that remain bound to the unique iron of the C-terminal cluster (Figure 5A).56 Further analysis employing stopped-flow FT-IR and electron–nuclear double resonsance (ENDOR) spectroscopies suggest that this Fe[CO][CN–] synthon is further converted by HydG to a Fe[CO]2[CN–] complex. The entire Fe[CO]2[CN–] complex forms the basis for one-half of the H-cluster and is subsequently transferred to apo-HydA, probably through the combined action of HydE and HydF, to ultimately form the mature HydA [FeFe]-hydrogenase.57

Figure 5.

(A) Recently proposed mechanism for the cleavage of tyrosine by HydG: Tyrosine binds to the auxiliary C-terminal [Fe4S4] cluster. Ado• generated by N-terminal [Fe4S4] cluster reacts with tyrosine, producing a tyrosyl radical. Cleavage of the tyrosyl radical results in 4-oxidobenzyl radical and dehydroglycine bound to the auxiliary cluster that is subsequently cleave to produce CO and CN– ligands to the H cluster of HydA. (B) Proposed mechanism for the conversion of GTP to 3′, 8-cH2GTP by MoaA; MoaC is now established to catalyze the further steps necessary to produce the pyranopterin ring system.

4.3. Molybdopterin Biosynthesis—MoaA and MoaC

Molybdopterin is one of the few molybdenum-containing compounds synthesized in nature. In animals guanosine triphosphate (GTP) serves as precursor.58 In a complex reaction, the first two enzymes in the molybdopterin biosynthetic pathway, MoaA and MoaC, convert GTP into cyclic pyranopterin monophosphate (cPMP) an intermediate possessing a system of four linked six-membered rings.59 There have been various mechanistic proposals for this transformation and some debate about the roles of MoaA and MoaC in the production of cPMP, which recent mechanistic experiments have begun to clarify.

MoaA is a radical SAM enzyme; its crystal structure with GTP and SAM bound provided the first clues to its function and mechanism.60 MoaA exists as a homodimer with each subunit contains two canonical radical SAM [Fe4S4] clusters: one at the N-terminus and one at the C-terminus of each subunit. The enzyme adopts a partial TIM (β/α)6 barrel structure with a hydrophilic channel in the center and a [Fe4S4] cluster on either side. SAM coordinates to the N-terminal [Fe4S4] cluster, whereas GTP coordinates to the C-terminal cluster.60

Recently, using deuterium-labeled substrates, that allowed intermediates to be characterized by mass spectrometry, it was possible to demonstrate that the C-3′ H atom of GTP is abstracted by Ado•.61,62 Furthermore, using 2,3,-dideoxyGTP as a substrate an intermediate containing the bond between the guanine C8 and ribose C3′ was obtained.63 Based on these results, a mechanism for the rearrangement was proposed in which the C-3′ radical attacks the C8 of guanosine to form a key C–C bond, which after reduction yields the intermediate 3′,8-cyclo GTP in the rearrangement product. It was suggested that further, nonradical steps catalyzed by MoaA would lead to a PMP-triphosphate intermediate that would be the substrate for MoaC (Figure 5B).62,63 However, it has now been shown that under anaerobic conditions MoaA catalyzes only the formation of 3′,8-cyclo GTP from GTP and SAM (Figure 5B).61 This product was isolated and structurally characterized and further shown to be converted to cPMP by MoaC, providing convincing evidence for the roles of the two enzymes in molybdopterin biosynthesis.

5. Concluding Remarks

The past two decades have seen the number of known radical SAM enzymes grow enormously to the point at which they comprise a remarkably diverse superfamily. As such, in a review such as this, it has only been possible to highlight recent advances in understanding a limited subset of enzymes. Although advances in recombinant technologies have greatly facilitated the expression of these enzymes, their oxygen sensitivity, low catalytic activity and the complexity of many of their substrates continue to make these enzymes challenging to work on. The increasing number of structures now available reveals a common fold for radical SAM enzymes based on the 8-stranded (full) or 6-stranded (partial) β/α-barrel. Another emerging theme is the presence of auxiliary iron sulfur clusters in many radical SAM enzymes that appear to serve diverse and often incompletely understood functions.

In contrast to their structural uniformity, the reactions catalyzed by radical SAM enzymes are discovered to be ever more diverse and mechanistically complex. As examples recent work has uncovered a novel role for Ado• in bacterial menaquinone biosynthesis and revealed unexpected mechanistic complexity in SPL, an enzyme that has been known for quite some time. Similarly, the seemingly simple methylation reaction catalyzed by RlmN has been shown to occur through a quite different mechanism than originally suggested, as have the methylthiolation reactions catalyzed by MiaB and RimO. Lastly, we suspect that few people would have predicted that the “inorganic” carbonyl and nitrile ligands found in the iron–hydrogenase cofactor would be derived from tyrosine. Hopefully radical SAM enzymes still hold further surprises to be uncovered.

Acknowledgments

Research in the authors’ laboratory is supported in part by grants National Science Foundation, CHE 1152055, CBET 1336636, and the National Institutes of Health, GM 093088.

Glossary

Glossary

- Radical SAM enzymes

a class of enzymes that utilize and iron sulfur cluster to reductively cleave S-adenosylmethionine to produce a 5′deoxyadenosyl radical. This highly reactive species participates in a remarkably wide range of biological reactions

- [Fe4S4] cluster

an inorganic complex comprising a cubic arrangement of iron and sulfur atoms that function as one-electron redox cofactors in many enzymatic reactions. In most cases, each of the four iron atoms is ligated by a cysteine residue from the protein; radical SAM enzymes are unique in that only three iron atoms are ligated by cysteine, leaving a vacant coordination position for SAM

- 5′-Deoxyadenosine

the product produced by radical SAM enzymes upon quenching of the transient 5′-deoxyadenosyl radical

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

References

- Chirpich T. P.; Zappia V.; Costilow R. N.; Barker H. A. (1970) Lysine 2,3-aminomutase. Purification and properties of a pyridoxal phosphate and S-adenosylmethionine-activated enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 245, 1778–1789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unkrig V.; Neugebauer F. A.; Knappe J. (1989) The free radical of pyruvate formate-lyase. Characterization by EPR spectroscopy and involvement in catalysis as studied with the substrate-analogue hypophosphite. Eur. J. Biochem. 184, 723–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballinger M. D.; Reed G. H.; Frey P. A. (1992) An organic radical in the lysine 2,3-aminomutase reaction. Biochemistry 31, 949–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontecave M.; Mulliez E.; Ollagnier-de-Choudens S. (2001) Adenosylmethionine as a source of 5′-deoxyadenosyl radicals. Curr. Opin Chem. Biol. 5, 506–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey P. A.; Magnusson O. T. (2003) S-Adenosylmethionine: A wolf in sheep’s clothing, or a rich man’s adenosylcobalamin?. Chem. Rev. 103, 2129–2148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sofia H. J.; Chen G.; Hetzler B. G.; Reyes-Spindola J. F.; Miller N. E. (2001) Radical SAM, a novel protein superfamily linking unresolved steps in familiar biosynthetic pathways with radical mechanisms: Functional characterization using new analysis and information visualization methods. Nucleic Acids Res. 29, 1097–1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vey J. L.; Drennan C. L. (2011) Structural insights into radical generation by the radical SAM superfamily. Chem. Rev. 111, 2487–2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atta M.; Mulliez E.; Arragain S.; Forouhar F.; Hunt J. F.; Fontecave M. (2010) S-Adenosylmethionine-dependent radical-based modification of biological macromolecules. Curr. Opin Chem. Biol. 20, 684–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanz N. D.; Booker S. J. (2012) Identification and function of auxiliary iron-sulfur clusters in radical SAM enzymes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Proteins Proteomics 1824, 1196–1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broderick J. B.; Duffus B. R.; Duschene K. S.; Shepard E. M. (2014) Radical S-Adenosylmethionine Enzymes. Chem. Rev. 114, 4229–4317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q.; Liu W. (2011) Complex biotransformations catalyzed by radical S-adenosylmethionine enzymes. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 30245–30252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esberg B.; Leung H. C.; Tsui H. C.; Bjork G. R.; Winkler M. E. (1999) Identification of the miaB gene, involved in methylthiolation of isopentenylated A37 derivatives in the tRNA of Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 181, 7256–7265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arragain S.; Garcia-Serres R.; Blondin G.; Douki T.; Clemancey M.; Latour J. M.; Forouhar F.; Neely H.; Montelione G. T.; Hunt J. F.; Mulliez E.; Fontecave M.; Atta M. (2010) Post-translational modification of ribosomal proteins: Structural and functional characterization of RimO from Thermotoga maritima, a radical S-adenosylmethionine methylthiotransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 5792–5801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebs C.; Broderick W. E.; Henshaw T. F.; Broderick J. B.; Huynh B. H. (2002) Coordination of adenosylmethionine to a unique iron site of the [4Fe-4S] of pyruvate formate-lyase activating enzyme: A Mossbauer spectroscopic study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 912–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimori D. G. (2013) Radical SAM-mediated methylation reactions. Curr. Opin Chem. Biol. 17, 597–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Challand M. R.; Driesener R. C.; Roach P. L. (2011) Radical S-adenosylmethionine enzymes: Mechanism, control, and function. Nat. Prod. Rep. 28, 1696–1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jameson G. N.; Cosper M. M.; Hernandez H. L.; Johnson M. K.; Huynh B. H. (2004) Role of the [2Fe-2S] cluster in recombinant Escherichia coli biotin synthase. Biochemistry 43, 2022–2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layer G.; Moser J.; Heinz D. W.; Jahn D.; Schubert W. D. (2003) Crystal structure of coproporphyrinogen III oxidase reveals cofactor geometry of Radical SAM enzymes. EMBO J. 22, 6214–6224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkovitch F.; Nicolet Y.; Wan J. T.; Jarrett J. T.; Drennan C. L. (2004) Crystal structure of biotin synthase, an S-adenosylmethionine-dependent radical enzyme. Science 303, 76–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atta M.; Arragain S.; Fontecave M.; Mulliez E.; Hunt J. F.; Luff J. D.; Forouhar F. (2012) The methylthiolation reaction mediated by the Radical-SAM enzymes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1824, 1223–1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doi Y.; Arakawa Y. (2007) 16S ribosomal RNA methylation: Emerging resistance mechanism against aminoglycosides. Clin. Infect. Diseases 45, 88–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benitez-Paez A.; Villarroya M.; Armengod M. E. (2012) The Escherichia coli RlmN methyltransferase is a dual-specificity enzyme that modifies both rRNA and tRNA and controls translational accuracy. RNA 18, 1783–1795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grove T. L.; Radle M. I.; Krebs C.; Booker S. J. (2011) Cfr and RlmN contain a single [4Fe-4S] cluster, which directs two distinct reactivities for S-adenosylmethionine: Methyl transfer by S(N)2 displacement and radical generation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 19586–19589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grove T. L.; Benner J. S.; Radle M. I.; Ahlum J. H.; Landgraf B. J.; Krebs C.; Booker S. J. (2011) A radically different mechanism for S-adenosylmethionine-dependent methyltransferases. Science 332, 604–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCusker K. P.; Medzihradszky K. F.; Shiver A. L.; Nichols R. J.; Yan F.; Maltby D. A.; Gross C. A.; Fujimori D. G. (2012) Covalent intermediate in the catalytic mechanism of the radical S-adenosyl-l-methionine methyl synthase RlmN trapped by mutagenesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 18074–18081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boal A. K.; Grove T. L.; McLaughlin M. I.; Yennawar N. H.; Booker S. J.; Rosenzweig A. C. (2011) Structural basis for methyl transfer by a radical SAM enzyme. Science 332, 1089–1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agris P. F. (1996) The importance of being modified: Roles of modified nucleosides and Mg2+ in RNA structure and function. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 53, 79–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbonavicius J.; Qian Q.; Durand J. M.; Hagervall T. G.; Bjork G. R. (2001) Improvement of reading frame maintenance is a common function for several tRNA modifications. EMBO J. 20, 4863–4873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landgraf B. J.; Arcinas A. J.; Lee K. H.; Booker S. J. (2013) Identification of an intermediate methyl carrier in the radical S-adenosylmethionine methylthiotransferases RimO and MiaB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 15404–15416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leipuviene R.; Qian Q.; Bjork G. R. (2004) Formation of thiolated nucleosides present in tRNA from Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium occurs in two principally distinct pathways. J. Bacteriol. 186, 758–766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez H. L.; Pierrel F.; Elleingand E.; Garcia-Serres R.; Huynh B. H.; Johnson M. K.; Fontecave M.; Atta M. (2007) MiaB, a bifunctional radical-S-adenosylmethionine enzyme involved in the thiolation and methylation of tRNA, contains two essential [4Fe-4S] clusters. Biochemistry 46, 5140–5147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierrel F.; Douki T.; Fontecave M.; Atta M. (2004) MiaB protein is a bifunctional radical-S-adenosylmethionine enzyme involved in thiolation and methylation of tRNA. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 47555–47563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anton B. P.; Saleh L.; Benner J. S.; Raleigh E. A.; Kasif S.; Roberts R. J. (2008) RimO, a MiaB-like enzyme, methylthiolates the universally conserved Asp88 residue of ribosomal protein S12 in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 1826–1831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K. H.; Saleh L.; Anton B. P.; Madinger C. L.; Benner J. S.; Iwig D. F.; Roberts R. J.; Krebs C.; Booker S. J. (2009) Characterization of RimO, a new member of the methylthiotransferase subclass of the radical SAM superfamily. Biochemistry 48, 10162–10174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arragain S.; Handelman S. K.; Forouhar F.; Wei F. Y.; Tomizawa K.; Hunt J. F.; Douki T.; Fontecave M.; Mulliez E.; Atta M. (2010) Identification of eukaryotic and prokaryotic methylthiotransferase for biosynthesis of 2-methylthio-N6-threonylcarbamoyladenosine in tRNA. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 28425–28433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forouhar F.; Arragain S.; Atta M.; Gambarelli S.; Mouesca J. M.; Hussain M.; Xiao R.; Kieffer-Jaquinod S.; Seetharaman J.; Acton T. B.; Montelione G. T.; Mulliez E.; Hunt J. F.; Fontecave M. (2013) Two Fe-S clusters catalyze sulfur insertion by radical-SAM methylthiotransferases. Nat. Chem. Biol. 9, 333–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierrel F.; Bjork G. R.; Fontecave M.; Atta M. (2002) Enzymatic modification of tRNAs: MiaB is an iron-sulfur protein. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 13367–13370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalak J. A.; Walsh K. A. (1996) β-methylthio-aspartic acid: Identification of a novel post-translational modification in ribosomal protein S12 from Escherichia coli. Protein Sci. 5, 1625–1632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strader M. B.; Costantino N.; Elkins C. A.; Chen C. Y.; Patel I.; Makusky A. J.; Choy J. S.; Court D. L.; Markey S. P.; Kowalak J. A. (2011) A proteomic and transcriptomic approach reveals new insight into β-methylthiolation of Escherichia coli ribosomal protein S12. Mol. Cell Proteomics 10, M110 005199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei F. Y.; Suzuki T.; Watanabe S.; Kimura S.; Kaitsuka T.; Fujimura A.; Matsui H.; Atta M.; Michiue H.; Fontecave M.; Yamagata K.; Suzuki T.; Tomizawa K. (2011) Deficit of tRNA(Lys) modification by Cdkal1 causes the development of type 2 diabetes in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 121, 3598–3608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young A. P.; Bandarian V. (2013) Radical mediated ring formation in the biosynthesis of the hypermodified tRNA base wybutosine. Curr. Opin Chem. Biol. 17, 613–618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y.; Noma A.; Suzuki T.; Senda M.; Senda T.; Ishitani R.; Nureki O. (2007) Crystal structure of the radical SAM enzyme catalyzing tricyclic modified base formation in tRNA. J. Mol. Biol. 372, 1204–1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young A. P.; Bandarian V. (2011) Pyruvate is the source of the two carbons that are required for formation of the imidazoline ring of the 4-demethylwyosine. Biochemistry 50, 10573–10575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perche-Letuvee P.; Kathirvelu V.; Berggren G.; Clemancey M.; Latour J.-M.; Maurel V.; Douki T.; Armengaud J.; Mulliez E.; Fontecave M.; Garcia-Serres R.; Gambarelli S.; Atta M. (2012) 4-Demethylwyosine synthase from Pyrococcus abyssi is a radical-S-adenosyl-l-methionine enzyme with an additional [4Fe-4S](+2) cluster that interacts with the pyruvate co-substrate. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 41174–41185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahanta N.; Fedoseyenko D.; Dairi T.; Begley T. P. (2013) Menaquinone biosynthesis: Formation of aminofutalosine requires a unique radical SAM enzyme. J. Am. Chem, Soc. 135, 15318–15321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo M. S.; Yurek D. A.; Coats J. H.; Li G. P. (1989) Isolation and identification of 7,8-didemethyl-8-hydroxy-5-deazariboflavin, an unusual cosynthetic factor in streptomycetes, from Streptomyces lincolnensis. J. Antibiot. 42, 475–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decamps L.; Philmus B.; Benjdia A.; White R.; Begley T. P.; Berteau O. (2012) Biosynthesis of F-0, precursor of the F-420 cofactor, requires a unique two radical-SAM domain enzyme and tyrosine as substrate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 18173–18176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey P. A.; Hegeman A. D.; Ruzicka F. J. (2008) The radical SAM superfamily. Crit Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 43, 63–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjdia A.; Heil K.; Barends T. R.; Carell T.; Schlichting I. (2012) Structural insights into recognition and repair of UV–DNA damage by spore photoproduct lyase, a radical SAM enzyme. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, 9308–9318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L.; Lin G.; Liu D.; Dria K. J.; Telser J.; Li L. (2011) Probing the reaction mechanism of spore photoproduct lyase (SPL) via diastereoselectively labeled dinucleotide SP TpT substrates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 10434–10447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandor-Proust A.; Berteau O.; Douki T.; Gasparutto D.; Ollagnier-de-Choudens S.; Fontecave M.; Atta M. (2008) DNA repair and free radicals, new insights into the mechanism of spore photoproduct lyase revealed by single amino acid substitution. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 36361–36368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L.; Nelson R. S.; Benjdia A.; Lin G.; Telser J.; Stoll S.; Schlichting I.; Li L. (2013) A radical transfer pathway in spore photoproduct lyase. Biochemistry 52, 3041–3050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulder D. W.; Boyd E. S.; Sarma R.; Lange R. K.; Endrizzi J. A.; Broderick J. B.; Peters J. W. (2010) Stepwise FeFe-hydrogenase H-cluster assembly revealed in the structure of HydA(Delta EFG). Nature 465, 248–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driesener R. C.; Duffus B. R.; Shepard E. M.; Bruzas I. R.; Duschene K. S.; Coleman N. J. R.; Marrison A. P. G.; Salvadori E.; Kay C. W. M.; Peters J. W.; Broderick J. B.; Roach P. L. (2013) Biochemical and kinetic characterization of radical S-adenosyl-l-methionine enzyme HydG. Biochemistry 52, 8696–8707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolet Y.; Martin L.; Tron C.; Fontecilla-Camps J. C. (2010) A glycyl free radical as the precursor in the synthesis of carbon monoxide and cyanide by the FeFe-hydrogenase maturase HydG. FEBS Lett. 584, 4197–4202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuchenreuther J. M.; Myers W. K.; Stich T. A.; George S. J.; NejatyJahromy Y.; Swartz J. R.; Britt R. D. (2013) A radical intermediate in tyrosine scission to the CO and CN-ligands of FeFe hydrogenase. Science 342, 472–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuchenreuther J. M.; Myers W. K.; Suess D. L. M.; Stich T. A.; Pelmenschikov V.; Shiigi S. A.; Cramer S. P.; Swartz J. R.; Britt R. D.; George S. J. (2014) The HydG enzyme generates an Fe(CO)(2)(CN) synthon in assembly of the FeFe hydrogenase H-cluster. Science 343, 424–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanzelmann P.; Schindelin H. (2004) Crystal structure of the S-adenosylmethionine-dependent enzyme MoaA and its implications for molybdenum cofactor deficiency in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 12870–12875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanzelmann P.; Schwarz G.; Mendel R. R. (2002) Functionality of alternative splice forms of the first enzymes involved in human molybdenum cofactor biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 18303–18312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanzelmann P.; Schindelin H. (2006) Binding of 5′-GTP to the C-terminal FeS cluster of the radical S-adenosylmethionine enzyme MoaA provides insights into its mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 6829–6834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hover B. M.; Loksztejn A.; Ribeiro A. A.; Yokoyama K. (2013) Identification of a cyclic nucleotide as a cryptic intermediate in molybdenum cofactor biosynthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 7019–7032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta A. P.; Hanes J. W.; Abdelwahed S. H.; Hilmey D. G.; Hanzelmann P.; Begley T. P. (2013) Catalysis of a new ribose carbon-insertion reaction by the molybdenum cofactor biosynthetic enzyme MoaA. Biochemistry 52, 1134–1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta A. P.; Abdelwahed S. H.; Begley T. P. (2013) Molybdopterin biosynthesis: Trapping an unusual purine ribose adduct in the MoaA-catalyzed reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 10883–10885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]