Abstract

Objective To evaluate the impact of sending an email to responsible parties of completed trials that do not comply with the Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act 801 legislation, to remind them of the legal requirement to post results.

Design Cohort embedded pragmatic randomized controlled trial.

Setting Trials registered on ClinicalTrials.gov.

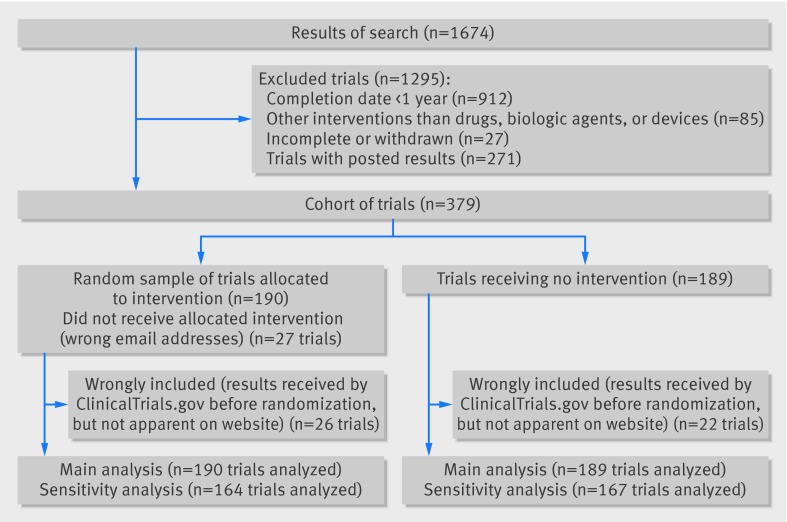

Participants 190 out of 379 trials randomly selected by computer generated randomization list to receive the intervention (personalized emails structured as a survey and sent by one of us to responsible parties of the trials, indirectly reminding them of the legal requirement and potential penalties for non-compliance).

Main outcome measures The primary outcome was the proportion of results posted on ClinicalTrials.gov at three months. The secondary outcome was the proportion posted at six months. In a second step, two assessors blinded to the intervention group collected the date of the first results being received on ClinicalTrials.gov. A post hoc sensitivity analysis excluding trials wrongly included was performed.

Results Among 379 trials included, 190 were randomized to receive the email intervention. The rate of posting of results did not differ at three months between trials with or without the intervention: 36/190 (19%) v 24/189 (13%), respectively (relative risk 1.5, 95% confidence interval 0.9 to 2.4, P=0.096) but did at six months: 46/190 (24%) v 27/189 (14%), 1.7, 1.1 to 2.6, P=0.014. In the sensitivity analysis, which excluded 48/379 trials (13%), 26/190 (14%) and 22/189 (12%), respectively, results were significant at three months (relative risk 5.1, 1.1 to 22.9, P=0.02) and at six months (4.1, 1.3 to 10.6, P=0.001).

Conclusions Sending email reminders about the FDA’s legal requirement to post results at ClinicalTrials.gov improved significantly the posting rate at six months but not at three months.

Trial registration ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01658254.

Introduction

Over the past decades, the under-reporting of trial results has been increasingly acknowledged as a major cause of wasted research.1 2 3 4 To overcome this problem, several initiatives were implemented. Since 2005, members of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors have refused to publish trials in their journals unless they were registered in a publicly accessible free of charge register.5 6 7 On 27 September 2007, the US Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act section 801 (FDAAA 801) added a policy about the posting of main results on the register ClinicalTrials.gov, called “basic results,” for all “applicable clinical trials” no later than one year after the primary completion date—that is, the date of collection of primary outcome data for the last patient to be enrolled.8 Applicable clinical trials include phase II to IV interventional controlled trials registered after the enactment of the FDAAA 801 (or ongoing at this date) involving drugs, biologic agents, or devices (only after FDA approval for any use) regardless of sponsorship and involving at least one US site, whatever the primary country of origin of the trials. Not complying with this requirement could result in civil monetary penalties (up to $10 000 (£6200; €7700) a day), and for federally funded studies the withholding of grant funds.8 9 10 11 12 However, compliance remains poor; approximately 75% of applicable clinical trials do not post basic results.13 14 15

We evaluated the impact of sending reminders to the responsible parties of trials to increase their posting of results at ClinicalTrials.gov.

Methods

Trial design

We identified a cohort of all trials registered on ClinicalTrials.gov that did not comply with the FDAAA 801 requirements for posting trial results. We randomly selected a sample of these trials to receive an intervention. The proportion of trials with basic results posted was assessed for the whole cohort and compared between trials receiving the intervention and the rest of the cohort. This design was similar to the “cohort multiple randomized controlled trial,” proposed elsewhere.16 The only difference was that we included trials rather than patients.

The random sample was determined by a computer generated randomization list, developed by an independent statistician who used R software.17 Allocation was concealed because the randomization was implemented automatically by a web based system. The responsible parties of trials were not aware of the main hypothesis of the study.

Study population

Our cohort included all phase IV trials meeting the FDAAA 801 requirements for which basic results were not posted on ClinicalTrials.gov one year after completion of the trial and that had available contact details (email addresses) of responsible parties. Because the identification of those trials under the FDAAA 801 regulation is difficult,13 we restricted our study to those registered as phase IV trials, which by definition are of FDA approved treatments for approved indications at approved doses.

We first selected all trials that were closed for recruitment, interventional, phase IV, and with at least one site in the United States, by searching ClinicalTrials.gov in the “Advanced research” section. The search was performed on 20 August 2012. We then automatically downloaded all data referring to the selected trials from ClinicalTrials.gov. One of us (AM) screened all trials records and excluded studies that appeared on ClinicalTrials.gov as incomplete or withdrawn; whose intervention was not a drug, a biologic, or a device; results already posted on ClinicalTrials.gov; and completion date less than one year. We thus included trials with an actual primary completion date (that is, the date when the final participant was examined or received an intervention for the purposes of final collection of data for the primary outcome) between October 2008 (one year after the date of application of FDAAA 801) and March 2011. In the screening we considered data as they were registered on the website ClinicalTrials.gov, without further verification.

We extracted the email addresses of responsible parties (sponsors or principal investigators, or both) from ClinicalTrials.gov. When both addresses were missing, we searched for them through Google and in Medline through PubMed. If data related to the sponsor or the principal investigators were missing or if no email address could be found, we excluded the trial.

Intervention

The experimental intervention consisted of sending reminders of the FDAAA 801 requirement through personalized emails to responsible parties of the randomly selected trials. The emails were constructed as surveys, notifying responsible parties of trials that the primary completion date was over a year old and asking for the reasons why they had not posted results on the register (see supplementary appendix). In fact the survey was a “cover” for the reminder. The personalized emails were automatically generated to include the title and the personal NCT number of the trial. The subject of the email was “Posting of basic results.” The emails reminded the recipient that according to the FDAAA 801, the results of their trial should have been posted. The email outlined reasons for posting, including whether responsible parties were aware of the risk of civil penalties (up to $10 000 a day) and withholding of grant funds for federally funded trials if they failed to comply with this requirement. Emails were signed by the last author of the current study, indicating his affiliation (Columbia University, Mailman School of Public Health). The emails were sent on 29 August 2012 to all responsible parties of trials as indicated in ClinicalTrials.gov (sponsors or principal investigators). A similar reminder was systematically sent at day 7 and at two and five months (see supplementary appendix).

Outcomes and measures

The primary outcome was the proportion of trials for which results were posted on ClinicalTrials.gov at three months. The secondary outcome was this proportion at six months.

Because of the quality control process of ClinicalTrials.gov, there is a delay between the posting of results by responsible parties and the day that the results appear as posted on the website. The date and “first received date” are publicly available on the website. Consequently, we extracted these data a posteriori on 18 July 2013 for the whole cohort. This extraction was done independently in duplicate by two assessors who were blinded to the allocated intervention. All disagreements were resolved by discussion to reach consensus.

Statistical analysis

According to estimates from a previous study,15 we assumed that the proportion of studies with results posted at 90 days would be about 10% in the control arm, without any intervention. We calculated the sample size based on the ability to detect an absolute difference of 10% in the primary outcome (that is, 20% of studies with results posted at 90 days with the intervention) between the intervention and control groups. We estimated a target sample size of 199 trials in each group (two tailed χ2 test with α 5% and β 20%).15 Only 190 trials were included in each group, but they corresponded to all available trials fulfilling the inclusion criteria.

We used the χ2 test to compare the proportion of trials with results posted at three and six months. In case of non-receipt of an email (“spam”) or an inaccurate email address for sponsors or principal investigators, we analyzed trials as if they had received the intervention. The results were presented as relative risk, risk difference, number of responsible parties needed to be contacted to obtain one additional posting (1/absolute risk reduction), and corresponding 95% confidence intervals.

Results are not immediately publicly available after being sent by the responsible party to ClinicalTrials.gov (because of the quality control process). We performed a post hoc sensitivity analysis excluding wrongly included trials (that is, trials included despite their results being sent by responsible parties to ClinicalTrials.gov on the date of randomization, but were not apparent on the ClinicalTrials.gov at the time of randomization).

All analyses were two sided and involved use of SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). We considered P<0.05 as significant.

Results

Study population

Among the 1674 studies screened at ClinicalTrials.gov, we identified 379 that had not posted results according to the FDAAA 801. These formed our cohort of trials; 271 (16%) had results posted. A random sample of 190 of these trials was allocated to the intervention group (fig 1). Table 1 shows the characteristics of trials from the whole cohort and the random sample. For 27 of the 190 trials (14%), the responsible party did not receive the allocated intervention because the email was returned with an error message.

Flow chart of trials

Table 1.

Characteristics of cohort of studies with no results posted at ClinicalTrials.gov and randomly selected trials. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Characteristics | Whole cohort (n=379) | Random selection of trials receiving intervention (n=190) | Control group (no intervention) (n=189) |

|---|---|---|---|

| No (interquartile range) of patients | 42 (20-100) | 40 (20-90) | 48 (22-100) |

| Randomized controlled trial | 256 (68) | 122 (64) | 134 (71) |

| Study objectives* | |||

| Efficacy | 137/313 (44) | 69/158 (44) | 68/155 (44) |

| Safety | 24/313 (8) | 12/158 (8) | 12/155 (8) |

| Efficacy or safety | 119/313 (38) | 60/158 (38) | 59/155 (38) |

| Other | 33/313 (10) | 17/158 (11) | 16/155 (10) |

| Trial intervention: | |||

| Drugs | 305 (80) | 157 (83) | 148 (78) |

| Devices | 67 (18) | 30 (16) | 37 (20) |

| Biologics | 7 (2) | 3 (2) | 4 (2) |

| Funding source: | |||

| Industry | 91 (24) | 43 (23) | 48 (25) |

| Not industry | 159 (42) | 89 (47) | 70 (37) |

| Mixed | 129 (34) | 58 (31) | 71 (38) |

| Masking: | |||

| Double blind | 145 (38) | 67 (35) | 78 (41) |

| Single blind | 50 (13) | 26 (14) | 24 (13) |

| Open label | 184 (48) | 97 (51) | 87 (46) |

| Publication in peer reviewed journal | 32 (8) | 23 (12) | 9 (5) |

*66 had missing data.

Outcome measures

At three months, 36/190 (19%) trials in the intervention group had posted results versus 24/189 (13%) in the control group (relative risk 1.5, 95% confidence interval 0.9 to 2.4, risk difference 6.2, 95% confidence interval −1.1 to 13.6, P=0.096, table 2). At six months, 46/190 (24%) trials in the intervention group had posted results versus 27/189 (14%) in the control group (1.7, 1.1 to 2.6, 9.9, 2.1 to 17.8, P=0.014).

Table 2.

Proportion of trials with results posted on ClinicalTrials.gov at three and six months. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Analysis | Intervention | Control | Risk difference (95% CI)* | Relative risk (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary analysis: | n=190 | n=189 | |||

| 3 months | 36 (19) | 24 (13) | 6.2 (−1.1 to 13.6) | 1.5 (0.9 to 2.4) | 0.096 |

| 6 months | 46 (24) | 27 (14) | 9.9 (2.1 to 17.8) | 1.7 (1.1 to 2.6) | 0.014 |

| Sensitivity analysis†: | n=164 | n=167 | |||

| 3 months | 10 (6) | 2 (1) | 4.9 (0.9 to 8.9) | 5.1 (1.1 to 22.9 ) | 0.02 |

| 6 months | 20 (12) | 5 (3) | 9.2 (3.6 to 14.8) | 4.1 (1.6 to 10.6) | 0.001 |

Three month assessment corresponds to posting results on 1 December 2012.

Six month assessment corresponds to posting results on 1 March 2013.

*Asymptotic 95% confidence interval.

†Excluding 48 trials not meeting inclusion criteria because “results first received date” were before randomization.

The number of trials for which responsible parties needed reminding to obtain one additional posting was 10.1 (95% confidence interval 5.6 to 48.7). In other words, email reminders sent to responsible parties of 10 trials led to results posted for one additional trial.

A post hoc sensitivity analysis excluding 48/379 wrongly included trials (13%), with results sent to ClinicalTrials.gov before randomization (26/190 (14%) in the intervention group and 22/189 (12%) in the control group, fig 2), showed significant results at three months (relative risk 5.1, 95% confidence interval 1.1 to 22.9, risk difference 4.9, 95% confidence interval 0.9 to 8.9, P=0.02) and six months (4.1, 1.3 to 10.6, 9.2, 3.6 to 14.8, P=0.001).

Answers to the survey

Among the random selected group of 190 trials that received the intervention, we received back 49 answers to our survey (26%). The answers of closed questions are reported in the appendix.

Discussion

Sending email reminders to responsible parties of trials not complying with the requirements of the US Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act section 801 (FDAAA 801), to post basic results within one year after trial completion, did not improve significantly the posting of results on ClinicalTrials.gov at three months but did at six months. By sending email reminders to responsible parties of 10 trials, results for one additional trial would be posted at six months. A sensitivity analysis excluding non-eligible trials showed significant results at three and six months. However, the proportion of trials without posted results was high at baseline and remained high at six months.10 13 14 15 18 To our knowledge, no published studies have previously evaluated any intervention to improve the posting of results on ClinicalTrials.gov.

Implications

Our trial has important implications. It aimed to be pragmatic, evaluating an intervention that we chose to be simple, easy to use, and of low cost. This intervention is based on automatically generated reminders about posting trial results, which can easily be replicated. Specific new internet tools (such as IF This Then That (IFTTT), an application allowing powerful connections to be made with this simple statement) could even be used for sending reminders.19 To improve participation, our emails were personalized to remind recipients of the trial title, ClinicalTrials.gov NCT number, and trial completion date. However, the emails looked like a survey; the content of the email was low key, listing several possible reasons for not posting results, with penalties listed, and emails were from one of us (PR) and not from an official party such as ClinicalTrials.gov or the FDA. These points probably decreased the efficacy of our intervention, particularly because they were addressed to already non-compliant parties. A more direct email sent by health authorities and telling recipients that they were in default and risked penalties (up to $10 000 a day) or grant funds being withheld and urging them to post their results might have more impact. Furthermore, the impact of the intervention could be underestimated, because 14% of the emails were returned with an error message.

We did not find any significant difference between the intervention and control groups in the posting of results on ClinicalTrials.gov at three months; however, results from the sensitivity analysis excluding non-eligible trials were significant. This can be explained by the delay between the first submission of trial results by responsible parties and their public posting at ClinicalTrials.gov.7 9 This delay can vary considerably. A study of 202 posted results showed a median delay of 65 days (interquartile range 32-142) between posting and public availability of results.20 In fact, when extracting data for the primary and secondary outcomes, we identified 48 trials (13%) with a “results first received” date that was before our date of randomization and which therefore did not meet our inclusion criteria. However, we could determine that these trials were wrongly included a posteriori, because the date when results are first received appears on the website only when ClinicalTrials.gov has publicly posted them. We could not proceed otherwise because of the validation process of ClinicalTrials.gov. The sensitivity analysis excluding these 48 trials that had been wrongly included showed a greater effect at three months (relative risk 5.1, 95% confidence interval 1.1 to 22.9, risk difference 4.9, 95% confidence interval 0.9 to 8.9, P=0.02) than with the main analysis (1.5, 0.9 to 2·4, and 6.2, −1.1 to 13.6, P=0.096).

Several reasons can explain why results were not posted. Firstly, responsible parties may not be aware of the legal requirements for posting results and the risk of penalties for non-compliance. In fact the FDAAA 801 is a complex act and determining which trial actually falls under the regulations may be difficult.11 13 18 Regarding countries under this regulation, the requirement to post results currently concerns trials of all countries, as long as one US site is involved. However, the dissemination and implementation of this law may need to be improved. These points are important to mention, when regulations concerning the publication of results and registries are being extended to the European Union.21 In addition, navigating the ClinicalTrials.gov register to post results can be difficult and time consuming. One study showed that approximately 38 hours was required to submit basic results on ClinicalTrials.gov, plus an additional 22 hours to collect the applicable data and information required by the register.9 Another reason could be that some of the responsible parties are probably unaware that publishing results in a journal does not exempt them from posting results on the registry. Yet another study showed that the reporting could be more complete on ClinicalTrials.gov than in published articles, particularly for safety data.15 Regardless, the rate of published trials among our sample was low: 8% at baseline among the 379 studies without posted results. This rate agrees with previous findings: cumulative percentages of published results were 12% at 12 months after the completion of cancer trials in the study by Nguyen and colleagues and almost half at 36 months in the same study and in the study by Ross and colleagues.15 22

Limitations of this study

Our study has several limitations. Some trials included did not meet our inclusion criteria, because the “results first received” date appears only when the results have been validated by ClinicalTrials.gov and called “posted.” To overcome this problem, we tried to access this information later (July 2013) and performed a sensitivity analysis. Secondly, because our trial aimed to be simple and pragmatic, we extracted data automatically after downloading them from the register. We might have included trials that did not fit our inclusion criteria, such as trials incorrectly registered by responsible parties as phase IV. However, this pitfall equally concerned both arms. Thirdly, we restricted our trial to studies registered as phase IV trials so as to use stringent criteria, ensuring that they were under the FDAAA 801 regulation. Fourthly, we included trials indicated as closed and might have missed trials with a “closed studies” status that had not been updated; the number of trials not complying may be larger than those we encountered. Another limitation is that for 14% of trials, the intervention was not received (returned with an error message), which highlights the need for updating email addresses of responsible parties in ClinicalTrials.gov. Also, our study focused on trials, which constituted the units of our analysis. Consequently, we did not consider that some sponsors or principal investigators could be involved in more than one trial. Finally, although we included all trials that met our criteria, the sample size was slightly lower than our sample size calculation.

Conclusions

Sending emails to remind responsible parties of trials of the FDAAA 801 legal requirements to post trial results one year after trial completion is a simple and inexpensive way to improve significantly the posting of results on ClinicalTrials.gov at six months but not at three months. A direct reminder from health authorities might be more effective.

What is already known on this topic

The under-reporting of trial results has been increasingly acknowledged as a major cause of wasted research

On 27 September 2007, the US Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act section 801 (FDAAA 801) added a policy about the posting of basic results on ClinicalTrials.gov for all “applicable clinical trials” no later than one year after the primary completion date

Although not complying with this requirement could result in penalties, compliance remains poor; approximately 75% of applicable clinical trials do not post basic results

What this study adds

Sending emails to remind responsible parties of trials of the FDAAA 801 legal requirements to post trial results one year after trial completion is a simple and inexpensive way to improve significantly the posting of results on ClinicalTrials.gov at six months

Results were not significant at three months

A direct reminder from health authorities might be more effective

Contributors: AM, IB, and PR conceived and designed the study. IB and PR supervised the study. All authors drafted the manuscript, critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content, had full access to all of the data in the study, and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. PR is the guarantor.

Funding: This study received no funding.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisation that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: This trial was approved by the institutional review board of Paris-Descartes, Ile de France II, France on 23 July 2012 (registration No 00001072).

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Transparency: The guarantor (PR) affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Cite this as: BMJ 2014;349:g5579

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Description of email intervention

Answers to survey

Forest plots for sensitivity analysis

References

- 1.Holtz RL What you don’t know about a drug can hurt you: untold numbers of clinical-trial results go unpublished; those that are made public can’t always be believed. 2012. http://online.wsj.com/article/SB122903390105599607.html.

- 2.Lehman R, Loder W. Missing clinical trials data. BMJ 2012;344:d8158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan AW, Song F, Vickers A, Jefferson T, Dickersin K, Gøtzsche PC, et al. Increasing value and reducing waste: addressing inaccessible research. Lancet 2014;383:257-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glasziou P, Altman DG, Bossuyt P, Boutron I, Clarke M, Julious S, et al. Reducing waste from incomplete or unusable reports of biomedical research. Lancet 2014;383:267-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Angelis C, Drazen JM, Frizelle FA, Haug C, Hoey J, Horton R, et al. Clinical trial registration: a statement from the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. N Engl J Med 2004;351:1250-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wager E, Williams P; Project Overcome failure to Publish nEgative fiNdings Consortium. “Hardly worth the effort”? Medical journals’ policies and their editors’ and publishers’ views on trial registration and publication bias: quantitative and qualitative study. BMJ 2013;347:f5248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.ClinicalTrials.gov. 2014. www.ClinicalTrials.gov/.

- 8.Food and Drug Administration. Clinicaltrials.gov protocol registration system: US public law 110-185. 2010. http://prsinfo.ClinicalTrials.gov/fdaaa.html.

- 9.Lester M, Godlew B. ClinicalTrials.gov registration and results reporting: updates and recent activity. J Clin Res Best Pract 2011;7:1-5. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zarin DA, Tse T, Williams RJ, Califf RM, Ide NC. The ClinicalTrials.gov results database—update and key issues. N Engl J Med 2011;364:852-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tse T, Williams RJ, Zarin DA. Reporting “basic results” in ClinicalTrials.gov. Chest 2009;136:295-303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gopal RK, Yamashita TE, Prochazka AV. Research without results: inadequate public reporting of clinical trial results. Contemp Clin Trials 2012;33:486-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prayle AP, Hurley MN, Smyth AR. Compliance with mandatory reporting of clinical trial results on ClinicalTrials.gov: cross sectional study. BMJ 2012;344:d7373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gill CJ. How often do US-based human subjects research studies register on time, and how often do they post their results? A statistical analysis of the ClinicalTrials.gov database. BMJ Open 2012;2(4):pii:e001186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nguyen T, Dechartres A, Belgherbi S, Ravaud P. Public availability of results of trials assessing cancer drugs in the United States. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:2998-3003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Relton C, Torgerson D, O’Cathain A, Nicholl J. Rethinking pragmatic randomised controlled trials: introducing the “cohort multiple randomised controlled trial” design. BMJ 2010;340:c1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2012. www.R-project.org/.

- 18.Wadman M. FDA says study overestimated non-compliance with data-reporting laws. Nature News 2012. 10.1038/nature.2012.10549. [Google Scholar]

- 19.About IFTTT. 2014. http://ifttt.com.

- 20.Riveros C, Dechartres A, Perrodeau E, Haneef R, Boutron I, Ravaud P. Timing and completeness of trial results posted at ClinicalTrials.gov and published in journals. PLoS Med 2013;10:e1001566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kmietowicz Z. European regulator is urged to release data on drugs approved in past 10 years. BMJ 2013;347:f5905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ross JS, Tse T, Zarin DA, Xu H, Zhou L, Krumholtz HM. Publication of NIH funded trials registered in ClinicalTrials.gov: cross sectional analysis. BMJ 2012;344:d7292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of email intervention

Answers to survey

Forest plots for sensitivity analysis