Summary (Last updated November 6, 2013; last reviewed November 6, 2013)

This report updates the last version of the Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections (OIs) in HIV-Exposed and HIV-Infected Children, published in 2009. These guidelines are intended for use by clinicians and other health-care workers providing medical care for HIV-exposed and HIV-infected children in the United States. The guidelines discuss opportunistic pathogens that occur in the United States and ones that might be acquired during international travel, such as malaria. Topic areas covered for each OI include a brief description of the epidemiology, clinical presentation, and diagnosis of the OI in children; prevention of exposure; prevention of first episode of disease; discontinuation of primary prophylaxis after immune reconstitution; treatment of disease; monitoring for adverse effects during treatment, including immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS); management of treatment failure; prevention of disease recurrence; and discontinuation of secondary prophylaxis after immune reconstitution. A separate document providing recommendations for prevention and treatment of OIs among HIV-infected adults and post-pubertal adolescents (Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in HIV-Infected Adults and Adolescents) was prepared by a panel of adult HIV and infectious disease specialists (see http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/guidelines).

These guidelines were developed by a panel of specialists in pediatric HIV infection and infectious diseases (the Panel on Opportunistic Infections in HIV-Exposed and HIV-Infected Children) from the U.S. government and academic institutions. For each OI, one or more pediatric specialists with subject-matter expertise reviewed the literature for new information since the last guidelines were published and then proposed revised recommendations for review by the full Panel. After these reviews and discussions, the guidelines underwent further revision, with review and approval by the Panel, and final endorsement by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the HIV Medicine Association (HIVMA) of the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), the Pediatric Infectious Disease Society (PIDS), and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). So that readers can ascertain how best to apply the recommendations in their practice environments, the recommendations are rated by a letter that indicates the strength of the recommendation, a Roman numeral that indicates the quality of the evidence supporting the recommendation, and where applicable, a * notation that signifies a hybrid of higher-quality adult study evidence and consistent but lower-quality pediatric study evidence.

More detailed methodologic considerations are listed in Appendix 1 (Important Guidelines Considerations), including a description of the make-up and organizational structure of the Panel, definition of financial disclosure and management of conflict of interest, funding sources for the guidelines, methods of collecting and synthesizing evidence and formulating recommendations, public commentary, and plans for updating the guidelines. The names and financial disclosures for each of the Panel members are listed in Appendices 2 and 3, respectively.

An important mode of childhood acquisition of OIs and HIV infection is from infected mothers. HIV-infected women may be more likely to have coinfections with opportunistic pathogens (e.g., hepatitis C) and more likely than women who are not HIV-infected to transmit these infections to their infants. In addition, HIV-infected women or HIV-infected family members coinfected with certain opportunistic pathogens may be more likely to transmit these infections horizontally to their children, resulting in increased likelihood of primary acquisition of such infections in young children. Furthermore, transplacental transfer of antibodies that protect infants against serious infections may be lower in HIV-infected women than in women who are HIV-uninfected. Therefore, infections with opportunistic pathogens may affect not just HIV-infected infants but also HIV-exposed, uninfected infants. These guidelines for treating OIs in children, therefore, consider treatment of infections in all children—HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected—born to HIV-infected women.

In addition, HIV infection increasingly is seen in adolescents with perinatal infection who are now surviving into their teens and in youth with behaviorally acquired HIV infection. Guidelines for postpubertal adolescents can be found in the adult OI guidelines, but drug pharmacokinetics (PK) and response to treatment may differ in younger prepubertal or pubertal adolescents. Therefore, these guidelines also apply to treatment of HIV-infected youth who have not yet completed pubertal development.

Major changes in the guidelines from the previous version in 2009 include:

Greater emphasis on the importance of antiretroviral therapy (ART) for prevention and treatment of OIs, especially those OIs for which no specific therapy exists;

Increased information about diagnosis and management of IRIS;

Information about managing ART in children with OIs, including potential drug-drug interactions;

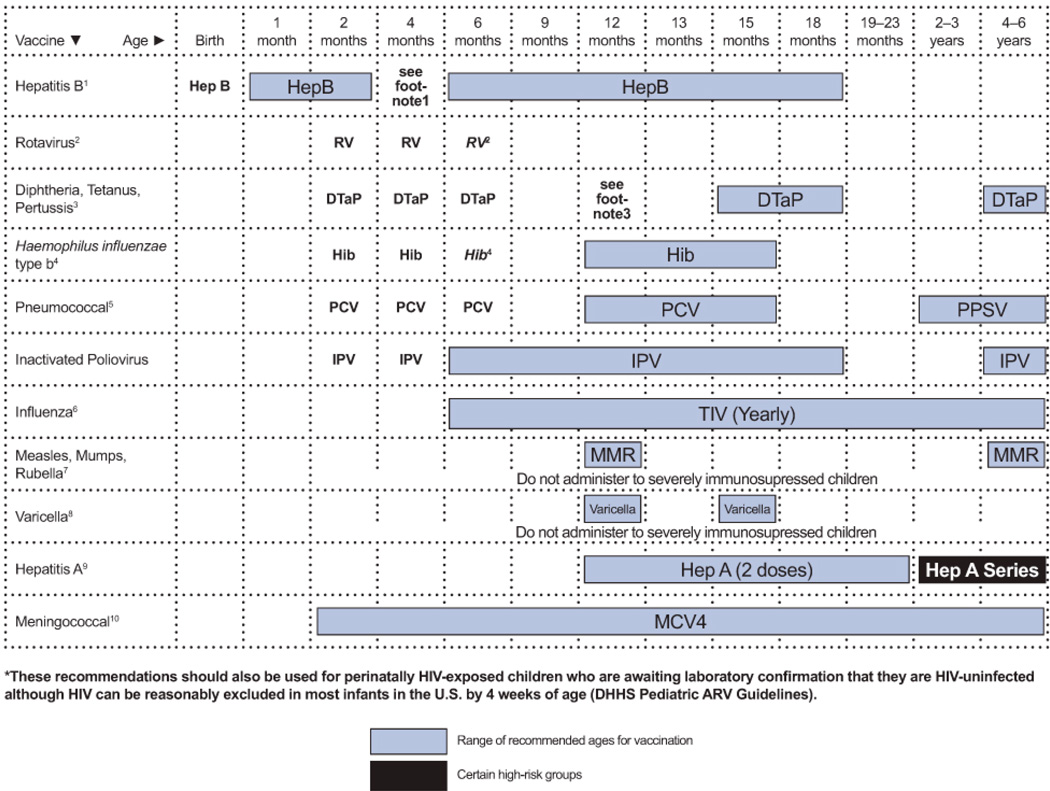

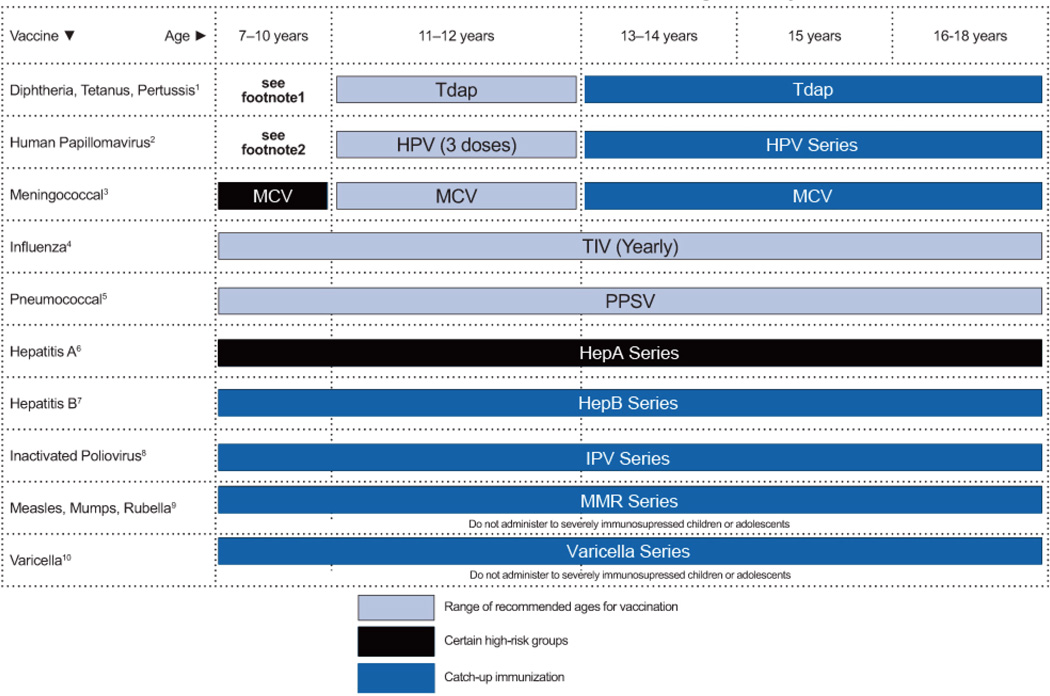

Updated immunization recommendations for HIV-exposed and HIV-infected children, including pneumococcal, human papillomavirus, meningococcal, and rotavirus vaccines;

Addition of sections on influenza, giardiasis, and isosporiasis;

Elimination of sections on aspergillosis, bartonellosis, and HHV-6 and HHV-7 infections; and

Updated recommendations on discontinuation of OI prophylaxis after immune reconstitution in children.

The most important recommendations are highlighted in boxed major recommendations preceding each section, and a table of dosing recommendations appears at the end of each section. The guidelines conclude with summary tables that display dosing recommendations for all of the conditions, drug toxicities and drug interactions, and 2 figures describing immunization recommendations for children aged 0 to 6 years and 7 to 18 years.

The terminology for describing use of antiretroviral (ARV) drugs for treatment of HIV infection has been standardized to ensure consistency within the sections of these guidelines and with the Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Pediatric HIV Infection. Combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) indicates use of multiple (generally 3 or more) ARV drugs as part of an HIV treatment regimen that is designed to achieve virologic suppression; highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), synonymous with cART, is no longer used and has been replaced by cART; the term ART has been used when referring to use of ARV drugs for HIV treatment more generally, including (mostly historical) use of one- or two-agent ARV regimens that do not meet criteria for cART.

Because treatment of OIs is an evolving science, and availability of new agents or clinical data on existing agents may change therapeutic options and preferences, these recommendations will be periodically updated and will be available at http://AIDSinfo.nih.gov.

Background (Last updated November 6, 2013; last reviewed November 6, 2013)

Opportunistic Infections in HIV-Infected Children in the Era of Combination Antiretroviral Therapy

In the era before development of potent cART regimens, OIs were the primary cause of death in HIV-infected children.1 Current ART regimens suppress viral replication, provide significant immune reconstitution, and have resulted in a substantial and dramatic decrease in AIDS-related OIs and deaths in both adults and children.2–5

Despite this progress, prevention and treatment of OIs remain critical components of care for HIV-infected children. OIs continue to be the presenting symptom of HIV infection among children whose HIV-exposure status is unknown because of lack of maternal antenatal HIV testing. For infants and children with known HIV infection, barriers such as inadequate medical care, lack of availability of suppressive ART regimens in the face of extensive prior treatment and drug resistance, caregiver substance abuse or mental illness, and multifactorial adherence difficulties may hinder effective HIV treatment and put them at risk of OIs even in the ART era. These same barriers may then impede provision of primary or secondary OI prophylaxis to children for whom such prophylaxis is indicated. In addition, concomitant OI prophylactic drugs may only exacerbate the existing difficulties in adhering to ART. Multiple drug-drug interactions between OI, ARV, and other compounds that result in increased adverse events and decreased treatment efficacy may limit the choice and continuation of both cART and prophylactic regimens. Finally, IRIS, initially described in HIV-infected adults but also seen in HIV-infected children, can complicate treatment of OIs when cART is started or when optimization of a failing regimen is attempted in patients with acute OIs. Thus, prevention and treatment of OIs in HIV-infected children remains important even in the cART era.

History of the Guidelines

In 1995, the U.S. Public Health Service (USPHS) and IDSA developed guidelines for preventing OIs in adults, adolescents, and children infected with HIV.6 These guidelines, developed for health-care providers and their HIV-infected patients, were revised in 1997, 1999, and 2002.7–9 In 2001, NIH, IDSA, and CDC convened a working group to develop guidelines for treating HIV-associated OIs, with a goal of providing evidence-based guidelines on treatment and prophylaxis. In recognition of unique considerations for HIV-infected infants, children, and adolescents—including differences between adults and children in mode of acquisition, natural history, diagnosis, and treatment of HIV-related OIs—a separate pediatric OI guidelines writing group was established. The pediatric OI treatment guidelines were initially published in December 2004.10 In 2009, recommendations for preventing and treating OIs in HIV-exposed and HIV-infected children were updated and combined into one document; a similar document on preventing and treating OIs among HIV-infected adults, prepared by a separate group of adult HIV and infectious disease specialists, was developed at the same time. Both sets of guidelines were prepared by the Opportunistic Infections Working Group under the auspices of the Office of AIDS Research (OAR) of the NIH. For the current document, the Opportunistic Infections Working Group, again under the auspices of OAR, convened a new panel of pediatric specialists with expertise in specific OIs. The Panel reviewed the literature since the last publication of the prevention and treatment guidelines, conferred over several months, and produced draft guidelines. These draft guidelines were revised based on review by the full Panel and review and approval by the core writing group members. The final report was further reviewed by OAR, experts at CDC, the HIVMA of IDSA, the PIDS, and AAP before final approval and publication.

Why Pediatric Prevention and Treatment Guidelines?

Mother-to-child transmission is an important mode of acquisition of HIV infection and of OIs in children. HIV-infected women coinfected with opportunistic pathogens may be more likely than HIV-uninfected women to transmit these infections to their infants. For example, higher rates of perinatal transmission of hepatitis C and cytomegalovirus (CMV) have been reported from HIV-infected than from HIV-uninfected women.11,12 In addition, HIV-infected women or HIV-infected family members coinfected with certain opportunistic pathogens may be more likely to transmit these infections horizontally to their children, increasing the likelihood of primary acquisition of such infections in young children. For example, Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in children primarily reflects acquisition from family members who have active tuberculosis (TB) disease, and increased incidence and prevalence of TB among HIV-infected individuals is well documented. HIV-exposed or HIV-infected children in the United States may have a higher risk of exposure to M. tuberculosis than would comparably aged children in the general U.S. population because of residence in households with HIV-infected adults.13 Furthermore, HIV-infected women may have transplacental transfer of lower levels of antibodies that protect their infants against serious bacterial infections than women who are not infected with HIV.14 Therefore, these guidelines for treatment and prevention of OIs consider both HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected children born to HIV-infected women.

The natural history of OIs in children may differ from that in HIV-infected adults. Many OIs in adults are secondary to reactivation of opportunistic pathogens, which often were acquired before HIV infection when host immunity was intact. However, OIs in HIV-infected children more often reflect primary infection with the pathogen. In addition, among children with perinatal HIV infection, the primary infection with the opportunistic pathogen occurs after HIV infection is established at a time when the child’s immune system already may be compromised. This can lead to different manifestations of specific OIs in children than in adults. For example, young children with TB are more likely than adults to have extrapulmonary and disseminated infection, even without concurrent HIV infection.

Multiple difficulties exist in making laboratory diagnoses of various infections in children. A child’s inability to describe the symptoms of disease often makes diagnosis more difficult. For infections such as hepatitis C (for which diagnosis is made by laboratory detection of specific antibodies), transplacental transfer of maternal antibodies that can persist in infants for up to 18 months complicates the ability to make a diagnosis in young infants. Assays capable of directly detecting the pathogen are required to diagnose such infections definitively in infants. In addition, diagnosing the etiology of lung infections in children can be difficult because they usually do not produce sputum, and more invasive procedures (e.g., gastric aspirates, bronchoscopy, lung biopsy) may be needed to make a more definitive diagnosis.

Data related to the efficacy of various therapies for OIs in adults are often extrapolated to children, but issues related to drug PK, formulation, ease of administration, dosing, and toxicity require special considerations for children. Young children, in particular, metabolize drugs differently from adults and older children, and the volume of distribution differs. Unfortunately, data often are lacking on appropriate drug dosing recommendations for children aged <2 years.

The prevalence of opportunistic pathogens in HIV-infected children during the pre-ART era varied by child age, previous OI, immunologic status, and pathogen.1 During the pre-ART era, the most common OIs in children in the United States (event rates >1 per 100 child-years) were serious bacterial infections (most commonly pneumonia, often presumptively diagnosed, and bacteremia), herpes zoster, disseminated Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC), Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (PCP), and candidiasis (esophageal and tracheobronchial disease). Less commonly observed OIs (event rate <1 per 100 child-years) included CMV disease, cryptosporidiosis, TB, systemic fungal infections, and toxoplasmosis.3,4 History of a previous AIDS-defining OI predicted development of a new infection. Although most infections occurred in substantially immunocompromised children, serious bacterial infections, herpes zoster, and TB occurred across the spectrum of immune status.

Descriptions of pediatric OIs in children receiving cART have been limited. Substantial decreases in mortality and morbidity, including OIs, have been observed among children receiving cART, as in HIV-infected adults.3,5 Although the number of OIs has substantially decreased during the cART era, HIV-associated OIs and other related infections continue to occur in HIV-infected children.3,15

In contrast to recurrent serious bacterial infections, some of the protozoan, fungal, or viral OIs complicating HIV are not curable with available treatments. Sustained, effective cART, resulting in improved immune status, has been established as the most important factor in controlling OIs in both HIV-infected adults and children. For many OIs, after treatment of the initial infectious episode, secondary prophylaxis in the form of suppressive therapy is indicated to prevent a recurrence of clinical disease as a result of re-activation or reinfection.

These guidelines are a companion to the 2013 Guidelines for Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in HIV-Infected Adults and Adolescents.16 Treatment of OIs is an evolving science, and availability of new agents or clinical data on existing agents may change therapeutic options and preferences. As a result, these recommendations will need to be periodically updated.

Because the guidelines target HIV-exposed and HIV-infected children in the United States, the opportunistic pathogens discussed are those common to the United States and do not include certain pathogens such as Penicillium marneffei that may be seen almost exclusively outside the United States, that are common but seldom cause chronic infection (e.g., chronic parvovirus B19 infection), or that have the same risk, disease course, and approach to prevention and treatment in all children regardless of HIV status (e.g., streptococcal pharyngitis). The document is organized to provide information about the epidemiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment of each pathogen. Major recommendations are accompanied by ratings that include a letter that indicates the strength of the recommendation and a Roman numeral that indicates the quality of the evidence supporting the recommendation; this rating system is similar to the rating systems used in other USPHS/IDSA guidelines. Because licensure of drugs for children often relies on efficacy data from adult trials in combination with safety data in children, recommendations sometimes may need to rely on data from clinical trials or studies in adults. Thus, the quality of evidence level is accompanied by a * notation to indicate that evidence supporting the recommendation is a hybrid of higher-quality adult study evidence and consistent but lower-quality pediatric study evidence. This modification to the rating system is the same as that used by the HHS Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Pediatric HIV Infection panel.

The tables at the end of this document summarize recommendations for dosing of medications used for treatment and prevention of OIs in children (Tables 1–3), drug preparation and toxicity information for children (Table 4), and drug-drug interactions (Table 5). Vaccination recommendations for HIV-infected children and adolescents are presented in Figures 1 and 2 at the end of the document.

Table 1.

Primary Prophylaxis of Opportunistic Infections in HIV-Exposed and HIV-Infected Children—Summary of Recommendations (Last updated November 6, 2013; last reviewed November 6, 2013)

| Indication | First Choice | Alternative | Comments/Special Issues |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial Infections S. pneumoniae and other invasive bacteria |

|

|

See Figures 1 and 2 for detailed vaccines recommendations. Vaccines Routinely Recommended for Primary Prophylaxis. Additional Primary Prophylaxis Indicated For:

|

| Candidiasis | Not routinely recommended | N/A | N/A |

| Coccidioidomycosis | N/A | N/A | Primary prophylaxis not routinely indicated in children. |

| Cryptococcosis | Not recommended | Not recommended | N/A |

| Cryptosporidiosis | ARV therapy to avoid advanced immune deficiency | N/A | N/A |

| Cytomegalovirus (CMV) |

|

N/A |

Primary Prophylaxis Can Be Considered for:

|

| Giardiasis | cART to avoid advanced immunodeficiency | N/A | N/A |

| Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) |

|

Hepatitis B immunoglobulin following exposure | See Figures 1 and 2 for detailed vaccine recommendations. Primary Prophylaxis Indicated for:

|

| Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) | None | N/A | N/A |

| Herpes Simplex Virus Infections (HSV) | None | None | Primary prophylaxis is not indicated. |

| Histoplasmosis | N/A | N/A | Primary Prophylaxis indicated for selected HIV-infected adults but not children. Criteria for Discontinuing Primary Prophylaxis:

|

| Human Papillomavirus (HPV) | HPV vaccine | N/A | See Figure 2 for detailed vaccine recommendations. |

| Influenza Primary Prophylaxis | Influenza vaccine | None | Note: See Figures 1 and 2 for detailed vaccines recommendations. |

| Primary Chemoprophylaxis Influenza A and B |

Oseltamivir for 10 daysa

|

None | Primary chemoprophylaxis is indicated for unvaccinated HIV-infected children with moderate-to-severe immunosuppression (as assessed by immunologic and/or clinical diagnostic categories) who are household contacts or close contacts of individuals with confirmed or suspected influenza. Chemoprophylaxis of vaccinated HIV-infected children with severe immunosuppression also may be indicated based on health-care provider assessment of the exposure situation. Post-exposure antiviral chemoprophylaxis should be initiated as soon as possible after exposure. a Oseltamivir chemoprophylaxis duration: Recommended duration is 10 days when administered after a household exposure and 7 days after the most recent known exposure in other situations. For control of outbreaks in long-term care facilities and hospitals, CDC recommends antiviral chemoprophylaxis for a minimum of 2 weeks and up to 1 week after the most recent known case was identified (see http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr6001a1.htm). b Oseltamivir is approved by the FDA for treatment of influenza in children aged ≥2 weeks. It is not approved for prophylaxis in children aged <1 year. However, the CDC recommends that health-care providers who treat children ages ≥3 months to <1 year administer a chemoprophylaxis dose of 3 mg/kg body weight/dose once daily. Chemoprophylaxis for infants aged <3 months is not recommended unless the exposure situation is judged to be critical. Premature infants: Current weight-based dosing recommendations for oseltamivir are not appropriate for premature infants (i.e., gestational age at delivery <38 weeks). See J Infect Dis 202 [4]:563-566, 2010 for dosing recommendations in premature infants. Renal insufficiency: A reduction in dose of oseltamivir is recommended for patients with creatinine clearance <30 mL/min. c Zanamivir: Zanamivir is not recommended for chemoprophylaxis in children aged <5 years old. |

|

Primary Chemoprophylaxis Influenza A (ONLY)

Oseltamivir-resistant, adamantane-sensitive strains Based on CDC influenza surveillance; http://www.cdc.gov/flu/weekly/fluactivitysurv.htm |

Amantadine or rimantadine for 10 daysd:

|

dAdamantanes: Because of resistance in currently circulating influenza A virus strains, amantadine and rimantadine are not currently recommended for chemoprophylaxis or treatment (adamantanes are not active against influenza B virus). However, potential exists for emergence of oseltamivir-resistant, adamantane-sensitive circulating influenza A strains. Therefore, verification of antiviral sensitivity of circulating influenza A strains should be done using the CDC influenza surveillance website: http://www.cdc.gov/flu/weekly/fluactivitysurv.htm If administered based on CDC antiviral sensitivity surveillance data, both amantadine and rimantadine are recommended for chemoprophylaxis of influenza A in children aged ≥1 yr. For treatment, rimantadine is only approved for use in adolescents aged ≥13 years. Rimantadine is preferred over amantadine because of less frequent adverse events. Some pediatric influenza specialists may consider it appropriate for treatment of children aged >1 year. Renal insufficiency: A reduction in dose of amantadine is recommended for patients with creatinine clearance <30 mL/min. |

|

| Isosporiasis (Cystoisosporiasis) | There are no U.S. recommendations for primary prophylaxis of isosporiasis. | N/A | Initiation of cART to avoid advanced immunodeficiency may reduce incidence; TMP-SMX prophylaxis may reduce incidence. |

| Malaria |

For Travel To Chloroquine-Sensitive Areas

|

N/A | Recommendations are the same for HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected children. Please refer to the following website for the most recent recommendations based on region and drug susceptibility: http://www.cdc.gov/ malaria/ For travel to chloroquine-sensitive areas. Equally recommended options include chloroquine, atovaquone/proguanil, doxycycline (for children aged ≥8 years), and mefloquine; primaquine is recommended for areas with mainly P. vivax. G6PD screening must be performed prior to primaquine use. Chloroquine phosphate is the only formulation of chloroquine available in the United States; 10 mg of chloroquine phosphate = 6 mg of chloroquine base. For travel to chloroquine-resistant areas, preferred drugs are atovaquone/proguanil, doxycycline (for children aged ≥8 years) or mefloquine. |

| Microsporidiosis | N/A | N/A | Not recommended |

| Mycobacterium avium Complex (MAC) |

|

|

Primary Prophylaxis Indicated for Children:

|

| Mycobacterium Tuberculosis (post-exposure) |

Source Case Drug Susceptible:

|

|

Drug-drug interactions with cART should be considered for all rifamycin containing alternatives. Indication:

|

| Pneumocystis jirovecii Pneumonia |

|

Dapsone Children aged ≥1 months:

Children Aged 1–3 Months and >24 Months–12 Years:

Children Aged ≥5 Years:

|

Primary Prophylaxis Indicated For:

Note: Do not discontinue in HIV-infected children aged <1 year After ≥6 Months of cART:

|

| Syphilis | N/A | N/A |

Primary Prophylaxis Indicated for:

|

| Toxoplasmosis | TMP-SMX 150/750 mg/m2 body surface area once daily by mouth |

For Children Aged ≥1 Month:

|

Primary Prophylaxis Indicated For: IgG Antibody to Toxoplasma and Severe Immunosuppression:

Note: Do not discontinue in children aged <1 year

|

| Varicella-Zoster Virus (VZV) Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis | Varicella vaccine | N/A | See Figures 1 and 2 for detailed vaccine recommendations. |

| Varicella-Zoster Virus (VZV) Primary (Post-Exposure) Prophylaxis | VariZIG 125 IU/10 kg body weight IM (maximum 625 IU), administered ideally within 96 hours (potentially beneficial up to 10 days) after exposure |

|

Primary Post-Exposure Prophylaxis Indicated for:

a CDC. Revised classification system for human immunodeficiency virus infection in children less than 13 years of age. Official authorized addenda: human immunodeficiency virus infection codes and official guidelines for coding and reporting ICD-9-CM. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1994;43:1-19. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/PDF/rr/ rr4312.pdf. |

Key to Acronyms: ARV = antiretroviral; BSA = body surface area; cART = combination antiretroviral therapy; CrCl= (estimated) creatinine clearance; DOT = directly observed therapy; HBV = hepatitis B virus; IGRA = interferon-gamma release assay; QID = four times daily; TB = tuberculosis; TMP-SMX = trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole

Table 3.

Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in HIV-Exposed and HIV-Infected Children—Summary of Recommendations (Last updated April 2, 2014; last reviewed November 6, 2013)

| Indication | First Choice | Alternative | Comments/Special Issues |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Bacterial Infections Bacterial pneumonia S. pneumoniae; occasionally S. aureus, H. influenzae, P. aeruginosa |

|

|

For children who are receiving effective cART, have mild or no immunosuppression, and have mild to moderate community-acquired pneumonia, oral therapy option would be amoxicillin 45 mg/kg body weight per dose twice daily (maximum dose: 4 g per day). Add azithromycin for hospitalized patients to treat other common community-acquired pneumonia pathogens (M. pneumoniae, C. pneumoniae). Add clindamycin or vancomycin if methicillin-resistant S. aureus is suspected (base the choice on local susceptibility patterns). For patients with neutropenia, chronic lung disease other than asthma (e.g., LIP, bronchiectasis) or indwelling venous catheter, consider regimen that includes activity against P. aeruginosa (such as ceftazidime or cefepime instead of ceftriaxone). Consider PCP in patients with severe pneumonia or more advanced HIV disease. Evaluate for tuberculosis, cryptococcosis, and endemic fungi as epidemiology suggests. |

| Candidiasis |

Oropharyngeal:

Critically Ill Echinocandin Recommended:

Fluconazole Recommended:

|

Oropharyngeal (Fluconazole-Refractory):

Esophageal Disease:

|

Itraconazole oral solution should not be used interchangeably with itraconazole capsules. Itraconazole capsules are generally ineffective for treatment of esophageal disease. Central venous catheters should be removed, when feasible, in HIV-infected children with fungemia. In uncomplicated catheter-associated C. albicans candidemia, an initial course of amphotericin B followed by fluconazole to complete treatment can be used (use invasive disease dosing). Voriconazole has been used to treat esophageal candidiasis in a small number of HIV-uninfected immunocompromised children. Voriconazole Dosing in Pediatric Patients:

Treatment Duration:

|

| Coccidioidomycosis |

Severe Illness with Respiratory Compromise due to Diffuse Pulmonary or Disseminated Non-Meningitic Disease:

|

Severe Illness with Respiratory Compromise Due to Diffuse Pulmonary or Disseminated Non-Meningitic Disease (If Unable to Use Amphotericin):

|

Surgical debridement of bone, joint, and/or excision of cavitary lung lesions may be helpful. Itraconazole is the preferred azole for treatment of bone infections. Some experts initiate an azole during amphotericin B therapy; others defer initiation of the azole until after amphotericin B is stopped. For treatment failure, can consider voriconazole, caspofungin, or posaconazole (or combinations). However, experience is limited and definitive pediatric dosages have not been determined. Options should be discussed with an expert in the treatment of coccidioidomycosis. Chronic suppressive therapy (secondary prophylaxis) with fluconazole or itraconazole is routinely recommended following initial induction therapy for disseminated disease and is continued lifelong for meningeal disease. Therapy with amphotericin results In a more rapid clinical response in severe, non-meningeal disease. |

Meningeal Infection:

|

Meningeal Infection (Unresponsive to Fluconazole):

|

||

| Cryptococcosis |

CNS Disease Acute Therapy (Minimum 2-Week Induction Followed by Consolidation Therapy):

|

CNS Disease Acute Therapy (Minimum 2-Week Induction Followed by Consolidation Therapy) If Flucytosine Not Tolerated or Unavailable:

|

In patients with meningitis, CSF culture should be negative prior to initiating consolidation therapy. Overall, in vitro resistance to antifungal agents used to treat cryptococcosis remains uncommon. Newer azoles (voriconazole, posaconazole, ravuconazole) are all very active in vitro against C. neoformans, but published clinical experience on their use for cryptococcosis is limited. Liposomal amphotericin and amphotericin B lipid complex are especially useful for children with renal insufficiency or infusion-related toxicity to amphotericin B deoxycholate. Liposomal amphotericin and amphotericin B lipid complex are significantly more expensive than amphotericin B deoxycholate. Liquid preparation of itraconazole (if tolerated) is preferable to tablet formulation because of better bioavailability, but it is more expensive. Bioavailability of the solution is better than the capsule, but there were no upfront differences in dosing range based on preparation used. Ultimate dosing adjustments should be guided by itraconazole levels. Serum itraconazole concentrations should be monitored to optimize drug dosing. Amphotericin B may increase toxicity of flucytosine by increasing cellular uptake, or impair its renal excretion, or both. Flucytosine dose should be adjusted to keep 2-hour post-dose drug levels at 40–60 µg/mL Oral acetazolamide should not be used for reduction of ICP in cryptococcal meningitis. Corticosteroids and mannitol have been shown to be ineffective in managing ICP in adults with cryptococcal meningitis. Secondary prophylaxis is recommended following completion of initial therapy (induction plus consolidation)—drugs and dosing listed above. bDuration of therapy for non-CNS disease depends on site and severity of infection and clinical response |

| Cryptosporidiosis |

Effective cART:

|

There is no consistently effective therapy for cryptosporidiosis in HIV-infected individuals; optimized cART and a trial of nitazoxanide can be considered. Nitazoxanide (BI, HIV-Uninfected; BII*, HIV-Infected in Combination with Effective cART):

|

Supportive Care:

|

| Cytomegalovirus (CMV) |

Symptomatic Congenital Infection with Neurologic Involvement:

Induction Therapy (Followed by Chronic Suppressive Therapy):

|

Disseminated Disease and Retinitis: Induction Therapy (Followed by Chronic Suppressive Therapy):

Alternatives for Retinitis (Followed by Chronic Suppressive Therapy; See Secondary Prophylaxis):

|

|

| Giardiasis |

|

Metronidazole 5 mg/kg by mouth every 8 hours for 5–7 days. Note: Based on data from HIV-uninfected children |

Tinidazole is approved in the United States for children aged ≥3 years. It is available in tablets that can be crushed. Metronidazole has high frequency of gastrointestinal side effects. A pediatric suspension of metronidazole is not commercially available but can be compounded from tablets. It is not FDA-approved for the treatment of giardiasis. Supportive Care:

|

| Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) |

Treatment of Only HBV Required (Child Does Not Require cART):

|

|

Indications for Treatment Include:

Choice of HBV treatment options for HIV/HBV-co-infected children depends upon whether concurrent HIV treatment is warranted. 3TC and FTC have similar activity (and have cross-resistance) and should not be given together. FTC is not FDA-approved for treatment of HBV. Tenofovir is approved for use in treatment of HIV infection in children aged ≥2 years but it is not approved for treatment of HBV infection in children aged <18 years. It should only be used for HBV in HIV/HBV-infected children as part of a cART regimen. Adefovir is approved for use in children aged ≥12 years. ETV is not approved for use in children younger than age 16 years, but is under study in HIV-uninfected children for treatment of chronic hepatitis B. Can be considered for older HIV-infected children who can receive adult dosage. It should only be used for HBV in HIV/HBV-infected children who also receive an HIV-suppressive cART regimen. IRIS may be manifested by dramatic increase in transaminases as CD4 cell counts rise within the first 6 to 12 weeks of cART. It may be difficult to distinguish between drug-induced hepatotoxicity and other causes of hepatitis and IRIS. In children receiving tenofovir and 3TC or FTC, clinical and laboratory exacerbations of hepatitis (flare) may occur if the drug is discontinued; thus, once anti-HIV/HBV therapy has begun, it should be continued unless contraindicated or until the child has been treated for >6 months after HBeAg seroconversion and can be closely monitored on discontinuation. If anti-HBV therapy is discontinued and a flare occurs, reinstitution of therapy is recommended because a flare can be life threatening. Telbivudine has been approved for use in people aged ≥16 years with HBV; there are no data on safety or efficacy in children aged <16 years; a pharmacokinetic study is under way in HIV-uninfected children. |

| Hepatitis C Virus |

IFN-α Plus Ribavirin Combination Therapy:

|

None | Optimal duration of treatment for HIV/HCV-coinfected children is unknown and based on

recommendations for HIV/HCV-coinfected adults Treatment of HCV in children <3 years generally is not recommended. Indications for treatment are based on recommendations in HIV/HCV-coinfected adults; because HCV therapy is more likely to be effective in younger patients and in those without advanced disease or immunodeficiency, treatment should be considered for all HIV/HCV-coinfected children aged >3 years in whom there are no contraindications to treatment For recommendations related to use of telaprevir or boceprevir in adults, including warnings about drug interactions between HCV protease inhibitors and HIV protease inhibitors and other antiretroviral drugs, see Adult OI guidelines. IRIS may be manifested by dramatic increase in transaminases as CD4 cell counts rise within the first 6–12 weeks of cART. It may be difficult to distinguish between IRIS and drug-induced hepatotoxicity or other causes of hepatitis. IFN-α is contraindicated in children with decompensated liver disease, significant cytopenias, renal failure, severe cardiac disorders and non-HCV-related autoimmune disease. Ribavirin is contraindicated in children with unstable cardiopulmonary disease, severe pre-existing anemia or hemoglobinopathy. Didanosine combined with ribavirin may lead to increased mitochondrial toxicities; concomitant use is contraindicated. Ribavirin and zidovudine both are associated with anemia, and when possible, should not be administered together |

| Herpes Simplex Virus Infections (HSV) |

Neonatal CNS or Disseminated Disease:

|

|

For Neonatal CNS Disease:

|

| Histoplasmosis |

Acute Primary Pulmonary Histoplasmosis:

Acute Therapy (Minimum 2-Week Induction, Longer if Clinical Improvement is Delayed, Followed by Consolidation Therapy):

Acute Therapy (4–6 Weeks, Followed by Consolidation Therapy):

|

Acute Primary Pulmonary Histoplasmosis:

Mild Disseminated Disease:

|

Use same initial itraconazole dosing for capsules as for solution. Itraconazole solution is preferred to the capsule formulation because it is better absorbed; solution can achieve serum concentrations 30% higher than those achieved with the capsules. Urine antigen concentration should be assessed at diagnosis. If >39 ng/mL, serum concentrations should be followed. When serum levels become undetectable, urine concentrations should be monitored monthly during treatment and followed thereafter to identify relapse. Serum concentrations of itraconazole should be monitored and achieve a level of 1 µg/mL at steady-state. Levels exceeding 10 µg/mL should be followed by dose reduction. High relapse rate with CNS infection occurs in adults and longer therapy may be required; treatment in children is anecdotal and expert consultation should be considered. Chronic suppressive therapy (secondary prophylaxis) with itraconazole is recommended in adults and children following initial therapy. Amphotericin B deoxycholate is better tolerated in children than in adults. Liposomal amphotericin B is preferred for treatment of parenchymal cerebral lesions. |

| Human Papillomavirus (HPV) |

|

|

Adequate topical anesthetics to the genital area should be given before caustic modalities are applied. Sexual contact should be limited while solutions or creams are on the skin. Although sinecatechins (15% ointment) applied TID up to 16 weeks is recommended in immunocompetent individuals, data are insufficient on safety and efficacy in HIV-infected individuals. cART has not been consistently associated with reduced risk of HPV-related cervical abnormalities in HIV-infected women. Laryngeal papillomatosis generally requires referral to a pediatric otolaryngologist. Treatment is directed at maintaining the airway, rather than removing all disease. For women who have exophytic cervical warts, a biopsy to exclude HSIL must be performed before treatment. Liquid nitrogen or TCA/BCA is recommended for vaginal warts. Use of a cryoprobe in the vagina is not recommended. Cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen or podophyllin resin (10%–25%) is recommended for urethral meatal warts. Cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen or TCA/BCA or surgical removal is recommended for anal warts. Abnormal Pap smear cytology should be referred to colposcopy for diagnosis and management. |

| Influenza A and B |

Oseltamivir for 5 dayse:

|

None |

eOseltamivir is FDA-approved for treatment of influenza in children aged ≥2 weeks. The CDC recommends that clinicians who treat children ages ≥3 months to <1 year administer a dose of 3 mg/kg twice daily. A dose of 3 mg/kg/dose twice daily also is recommended for infants aged <3 months. Premature Infants: Current weight-based dosing recommendations for oseltamivir are not appropriate for premature infants: gestational age at delivery <38 weeks. See J Infect Dis 202 [4]:563–566, 2010 for dosing recommendations in premature infants. Oseltamivir treatment duration: Recommended duration for antiviral treatment is 5 days; longer treatment courses can be considered for patients who remain severely ill after 5 days of treatment. Renal insufficiency: A reduction in dose of oseltamivir is recommended for patients with creatinine clearance <30 mL/min. fZanamivir: Zanamivir is not recommended for treatment in children aged <7 years. |

|

Influenza A (ONLY)

Oseltamivir-resistant, adamantane-sensitive strains (Based on CDC influenza surveillance www.cdc.gov/flu/weekly/fluactivitysurv.htm) |

Amantadine for 5 daysd:

|

dAdamantanes: Because of resistance in currently circulating influenza A virus strains, amantadine and rimantadine are not currently recommended for chemoprophylaxis or treatment (adamantanes are not active against influenza B virus). However, potential exists for emergence of oseltamivir-resistant, adamantane-sensitive circulating influenza A strains. Therefore, verification of antiviral sensitivity of circulating influenza A strains should be done using the CDC influenza surveillance website: http://www.cdc.gov/flu/weekly/fluactivitysurv.htm If administered based on CDC antiviral sensitivity surveillance data, both amantadine and rimantadine are recommended for chemoprophylaxis of influenza A in children aged ≥1 yr. For treatment, rimantadine is only approved for use in adolescents aged ≥13 years. Rimantadine is preferred over amantadine because of less frequent adverse events. Some pediatric influenza specialists may consider it appropriate for treatment of children aged >1 year. Renal insufficiency: A reduction in dose of amantadine is recommended for patients with creatinine clearance <30 mL/min. |

|

| Isosporiasis (Cystoisosporiasis) | TMP-SMX 5 mg/kg body weight of TMP component given twice daily by mouth for 10 days | Pyrimethamine 1 mg/kg body weight plus folinic acid 10–25 mg by mouth once daily for 14 days Second-Line Alternatives:

|

If symptoms worsen or persist, the TMP-SMX dose may be increased to 5 mg/kg/day given 3–4 times daily by mouth for 10 days or the duration of treatment may be lengthened. Duration of treatment with pyrimethamine has not been well established. Ciprofloxacin is generally not a drug of first choice in children due to increased incidence of adverse events, including events related to joints and/or surrounding tissues. |

| Malaria |

Uncomplicated P. Falciparum or Unknown Malaria Species, from Chloroquine-Resistant Areas (All Malaria Areas Except Those Listed as Chloroquine Sensitive) or Unknown Region:

Initial Therapy (Followed by Anti-Relapse Therapy for P. Ovale and P. Vivax):

|

N/A | For quinine-based regimens, doxycycline or tetracycline should be used only in children aged ≥8 years. An alternative for children aged ≥8 years is clindamycin 7 mg/kg body weight per dose by mouth given every 8 hours. Clindamycin should be used for children aged <8 years. Before primaquine is given, G6PD status must be verified. Primaquine may be given in combination with chloroquine if the G6PD status is known and negative, otherwise give after chloroquine (when G6PD status is available) For most updated prevention and treatment recommendations for specific region, refer to updated CDC treatment table available at http://www.cdc.gov/malaria/resources/pdf/treatmenttable.pdf For sensitive and resistant malaria map: http://cdc-malaria.ncsa.uiuc.edu/ High treatment failure rates due to chloroquine-resistant P. vivax have been documented in Papua New Guinea and Indonesia. Treatment should be selected from one of the three following options:

|

| Severe Malaria |

|

N/A | Quinidine gluconate is a class 1a anti-arrhythmic agent not typically stocked in pediatric hospitals. When regional supplies are unavailable, the CDC Malaria hotline may be of assistance (see below). Do not give quinidine gluconate as an IV bolus. Quinidine gluconate IV should be administered in a monitored setting. Cardiac monitoring required. Adverse events including severe hypoglycemia, prolongation of the QT interval, ventricular arrhythmia, and hypotension can result from the use of this drug at treatment doses. IND: IV artesunate is available from CDC. Contact the CDC Malaria Hotline at (770) 488–7788 from 8 a.m.– 4:30 p.m. EST or (770) 488–7100 after hours, weekends, and holidays. Artesunate followed by one of the following: Atovaquone-proguanil (Malarone™), clindamycin, mefloquine, or (for children aged >8 years) doxycycline. Quinidine gluconate: 10 mg = 6.25 mg quinidine base. Doxycycline (or tetracycline) should be used in children aged ≥8 years. For patients unable to take oral medication, may give IV. For children <45 kg, give 2.2 mg/kg IV every 12 hours and then switch to oral doxycycline. For children >45 kg, use the same dosing as per adults. For IV use, avoid rapid administration. For patients unable to take oral clindamycin, give 10 mg base/kg loading dose IV, followed by 5 mg base/kg IV every 8 hours. Switch to oral clindamycin (oral dose as above) as soon as a patient can take oral medication. For IV use, avoid rapid administration. Drug Interactions:

|

| Microsporidiosis |

Effective cART Therapy:

|

N/A |

|

| Mycobacterium avium Complex (MAC) |

Initial Treatment (≥2 Drugs):

|

If Intolerant to Clarithromycin:

|

Combination therapy with a minimum of 2 drugs is recommended for at least 12 months. Clofazimine is associated with increased mortality in HIV-infected adults and should not be used. Children receiving ethambutol who are old enough to undergo routine eye testing should have monthly monitoring of visual acuity and color discrimination. Fluoroquinolones (e.g., ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin) are not labeled for use in children aged <18 years because of concerns regarding potential effects on cartilage; use in younger individuals requires an assessment of potential risks and benefits Chronic suppressive therapy (secondary prophylaxis) is recommended in children and adults following initial therapy. |

| Mycobacterium Tuberculosis |

Intrathoracic Disease Drug-Susceptible TB Intensive Phase (2 Months):

Note: Depends on disease entity

MDR-TB:

|

Alternative for Rifampin:

If Good Adherence and Treatment Response:

|

Only DOT. If cART-naive, start TB therapy immediately and initiate cART within 2–8 weeks. Already on cART; review to minimize potential toxicities and drug-drug interactions; start TB treatment immediately. Potential drug toxicity and interactions should be reviewed at every visit. Adjunctive Treatment:

|

| Pneumocystis Pneumonia | TMP-SMX 3.75–5 mg/kg body weight/dose TMP (based on TMP component) every 6 hours IV or orally given for 21 days (followed by secondary prophylaxis dosing) |

If TMP-SMX-Intolerant or Clinical Treatment Failure After 5–7 Days of TMP-SMX Therapy Pentamidine:

Daily Dosing:

|

After acute pneumonitis resolved in mild-moderate disease, IV TMP-SMX can be changed to oral. For oral administration, total daily dose of TMP-SMX can also be administered in 3 divided doses (every 8 hours). Dapsone 2 mg/kg body weight by mouth once daily (maximum 100 mg/day) plus trimethoprim 5 mg/kg body weight by mouth every 8 hours has been used in adults but data in children are limited. Primaquine base 0.3 mg/kg body weight by mouth once daily (maximum 30 mg/day) plus clindamycin 10mg/kg body weight/ dose IV or by mouth (maximum 600 mg given IV and 300–450 mg given orally) every 6 hours has been used in adults, but data in children are not available. Indications for Corticosteroids:

|

| Syphilis |

Congenital Proven or Highly Probable Disease:

Early Stage (Primary, Secondary, Early Latent):

|

Congenital Proven or Highly Probable Disease (Less Desirable if CNS Involvement):

|

For treatment of congenital syphilis, repeat the entire course of treatment if >1 day of treatment is missed. Examinations and serologic testing for children with congenital syphilis should occur every 2–3 months until the test becomes non-reactive or there is a fourfold decrease in titer. Children with increasing titers or persistently positive titers (even if low levels) at ages 6–12 months should be evaluated and considered for re-treatment. In the setting of maternal and possible infant HIV infection, the more conservative choices among scenario-specific treatment options may be preferable. Children and adolescents with acquired syphilis should have clinical and serologic response monitored at 3, 6, 9, 12, and 24 months after therapy. |

| Toxoplasmosis |

Congenital Toxoplasmosis:

Acute Induction Therapy (Followed by Chronic Suppressive Therapy):

|

For Sulfonamide-Intolerant Patients:

|

Congenital Toxoplasmosis:

|

| Varicella-Zoster Virus (VZV) |

Chickenpox Children with No or Moderate Immune Suppression (CDC Immunologic Categories 1 and 2) and Mild Varicella Disease:

Children with Uncomplicated Zoster:

|

Patients Unresponsive to Acyclovir:

|

In children ≥1 year of age, some experts base IV acyclovir dosing on body surface area (500 mg/m2 body surface area/dose IV every 8 hours) instead of body weight. Valacyclovir is approved for use in adults and adolescents with zoster at 1 g/dose by mouth TID for 7 days; the same dose has been used for varicella infections. Data on dosing in children are limited and there is no pediatric preparation, although 500 mg capsules can be extemporaneously compounded to make a suspension to administer 20 mg/kg body weight/dose (maximum dose 1 g) given TID (see prescribing information). Famciclovir is approved for use in adults and adolescents with zoster at 500 mg/dose by mouth TID for 7 days; the same dose has been used for varicella infections. There is no pediatric preparation and data on dosing in children are limited; can be used by adolescents able to receive adult dosing. Involvement of an ophthalmologist with experience in managing herpes zoster ophthalmicus and its complications in children is strongly recommended when ocular involvement is evident. Optimal management of PORN has not been defined. |

Key to Acronyms: LIP = lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia; PCP = pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia; IV = intravenous; PK = pharmacokinetic; CSF = cerebrospinal fluid; CNS = central nervous system; ICP = intracranial pressure; cART = combination antiretroviral therapy; ART = antiretroviral therapy; BSA = body surface area; CrCl = (estimated) creatinine clearance; HBV = hepatitis B virus; SQ = subcutaneous; HCV = hepatitis C virus; IFN-α = interferon-alfa; BID = twice daily; TID = three times daily; QID = four times daily; CNS = central nervous system; CSF = cerebrospinal fluid; HSV = herpes simplex virus; PCR = polymerase chain reaction; BCA = bichloroacetic acid; IFN = interferon; TCA = trichloroacetic acid; TMP-SMX = trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole; DOT = directly observed therapy; IGRA = interferon-gamma release assay; IM = intramuscular; TB = tuberculosis; IRIS = immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome; TE = toxoplasmic encephalitis

Table 4.

Common Drugs Used for Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in HIV-Infected Children: Preparations and Major Toxicities (Last updated November 6, 2013; last reviewed November 6, 2013)

| Drug | Preparations | Major Toxicitiesa | Special Instructions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indicating Need for Medical Attention |

Indicating Need for Medical Attention if Persistent or Bothersome |

|||

| Acyclovir (Zovirax) |

Oral Suspension:

|

More Frequent:

Parenteral Form Only:

|

More Frequent:

|

Requires dose adjustment in patients with renal impairment. Avoid other nephrotoxic drugs. Administer IV preparation by slow IV infusion over at least 1 hour at a final concentration not to exceed 7 mg/mL. This is to avoid renal tubular damage related to crystalluria; must be accompanied by adequate hydration. |

| Albendazole (Albenza) |

Tablets:

|

More Frequent:

|

Less frequent:

|

Should be given with food. May crush or chew tablets and give with water. Monitor CBC and LFTs prior to each cycle. |

| Amikacin | IV |

More Frequent:

|

N/A | Must be infused over 30 to 60 minutes to avoid neuromuscular blockade. Requires dose adjustment in patients with impaired renal function. Should monitor renal function and hearing periodically (e.g., monthly) in children on prolonged therapy. Therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM). indicated |

| Amphotericin B Deoxycholate (Fungizone) | IV |

More Frequent:

|

|

Monitor BUN, Cr, CBC, electrolytes, LFTs. Infuse over 1 to 2 hours; in patients with azotemia, hyperkalemia, or getting doses >1 mg/kg, infuse over 3 to 6 hours. Requires dose reduction in patients with impaired renal function. Avoid other nephrotoxic drugs, when possible, because nephrotoxicity is exacerbated with concomitant use of other nephrotoxic drugs; permanent nephrotoxicity is related to cumulative dose. Nephrotoxicity may be ameliorated by hydration with 0.9% saline IV over 30 minutes prior to the amphotericin B infusion. Infusion-related reactions less frequent in children than adults; the onset is usually 1 to 3 hours after infusion, duration <1 hour; frequency decreases over time. Pre-treatment with acetaminophen and/or diphenhydramine may alleviate febrile reactions. |

| Amphotericin B Lipid Complex (Abelcet) | IV |

More Frequent:

|

|

Monitor BUN, Cr, CBC, electrolytes, and LFTs. Infuse diluted solution at rate of 2.5 mg/kg/hour. In-line filters should not be used. Use with caution with other drugs that are bone marrow suppressants or that are nephrotoxic; renal toxicity is dose-dependent, but less renal toxicity than seen with conventional amphotericin B. Consider dose reduction in patients with impaired renal function. |

| Amphotericin B Liposome (AmBisome) | IV |

More Frequent:

|

|

Monitor BUN, Cr, CBC, electrolytes, and LFTs. Infuse over 2 hours. Consider dose reduction in patients with impaired renal function. |

| Artesunate |

IV:

|

Rare:

|

|

Monitor CBC, LFTs, and electrolytes. ~40% less mortality than with quinidine use in severe malaria 50% lower incidence of hypoglycemia than quinidine |

| Atovaquone (Mepron) |

Oral Suspension:

|

Frequent:

|

Frequent:

|

Should be administered with a meal to enhance absorption; bioavailability increases 3-fold when administered with high-fat meal. |

| Atovaquone/ Proguanil (Malarone) |

Tablets:

|

Less frequent:

|

N/A | Pediatric tablets are available to make dosing easier. Side effects requiring discontinuation in ~1%–2% of patients Not recommended for prophylaxis in patients with CrCl <30 mL/min. |

| Azithromycin (Zithromax) |

Oral Suspension:

|

More Frequent:

|

|

Administer 1 hour before or 2 hours after a meal; do not administer with aluminum-and magnesium-containing antacids. IV should be infused at concentration of 1 mg/mL over a 3-hour period, or 2 mg/mL over a 1-hour period; should not be administered as a bolus. Use with caution in patients with hepatic function impairment; biliary excretion is the main route of elimination. Potential drug interactions. |

| Capreomycin (Capastat) | IM |

More Frequent:

|

N/A | Requires dose adjustment in patients with impaired renal function. Administer only by deep IM injection into large muscle mass (superficial injections may result in sterile abscess). Should monitor renal function and hearing periodically (e.g., monthly) in children on prolonged therapy. Monitor LFTs and electrolytes. |

| Caspofungin (Cancidas) | IV |

More Frequent:

|

|

Requires dose adjustment in moderate-to-severe hepatic insufficiency. IV infusion over 1 hour in normal saline (do not use diluents containing dextrose) |

| Chloroquine Phosphate (Aralen) |

Tablets:

|

More Frequent:

|

|

Store in child-proof containers and protect from light. Can be toxic in overdose. Bitter tasting, so consider administering with foods that can mask the taste. Solution available worldwide, but not in United States. Caution in patients with G6PD deficiency or seizure disorder. Monitor CBC; periodic neurologic and ophthalmologic exams in patients on prolonged therapy. |

| Cidofovir (Vistide) | IV |

More Frequent:

|

|

Infuse over 1 hour. Should not be used in patients with severe renal impairment. Nephrotoxicity risk is decreased with pre-hydration with IV normal saline and probenecid with each infusion. Probenecid is administered prior to each dose and repeated for two additional doses after infusion. Additional hydration after infusion is recommended if tolerated. Concurrent use of other nephro-toxic drugs should be avoided. Monitor renal function, urinalysis, electrolytes, and CBC and perform ophthalmologic exams. |

| Ciprofloxacin (Cipro) |

Oral Suspension:

Cipro XR:

|

Less Frequent:

|

More Frequent:

|

Administer oral formulations at least 2 hours before, or 6 hours after, sucralfate or antacids or other products containing calcium, zinc, or iron (including daily products or calcium-fortified juices). Take with full glass of water to avoid crystalluria. Possible phototoxicity reactions with sun exposure. IV infusions should be over 1 hour. Do not split, crush, or chew extended-release tablets. |

| Clarithromycin (Biaxin) |

Oral Suspension:

|

Rare:

|

More Frequent:

|

Requires dose adjustment in patients with impaired renal function. Can be administered without regard to meals. Reconstituted suspension should not be refrigerated. Potential drug interactions |

| Clindamycin (Cleocin) |

Oral Solution:

|

More Frequent:

|

More Frequent:

|

IV preparation contains benzyl alcohol, not recommended for use in neonates. IV preparation must be diluted prior to administration. Capsule formulation should be taken with food or a full glass of water to avoid esophageal irritation. Reconstituted oral solution should not be refrigerated. |

| Cycloserine (Seromycin) |

Capsules:

|

More Frequent:

|

|

Take with food to minimize gastric irritation. Neurotoxicity is related to excessive serum concentrations; serum concentrations should be maintained at 25–30 mcg/mL. Requires dose adjustment in patients with impaired renal function. Do not administer to patients with severe renal impairment (because of increased risk of neurotoxicity). Should monitor serum levels, if possible. Should administer pyridoxine at the same time. Monitor renal function, LFTs, and CBC. |

| Dapsone |

Syrup (available under Compassionate Use IND):

|

More Frequent:

|

|

Protect from light; dispense syrup in amber glass bottles. Monitor CBC and LFTs. |

| Doxycycline (Vibramycin) |

Tablets and Capsules:

|

More Frequent:

|

|

Swallow with adequate amounts of fluids Avoid antacids, milk, dairy products, and iron for 1 hour before or 2 hours after administration of doxycycline. Use with caution in hepatic and renal disease. IV doses should be infused over 1 to 4 hours. Patient should avoid prolonged exposure to direct sunlight (skin sensitivity). Generally not recommended for use in children aged <8 years because of risk of tooth enamel hypoplasia and discoloration, unless benefit outweighs risk. Monitor renal function, CBC, and LFTs if prolonged therapy. |

| Erythromycin |

Erythromycin- Base Tablet:

Suspension:

Suspension:

Tablet

|

Less Frequent:

|

|

Use with caution in liver disease. Oral therapy should replace IV therapy as soon as possible. Give oral doses after meals. Parenteral administration should consist of a continuous drip or slow infusion over 1 hour or longer. Adjust dose in renal failure. Erythromycin should be used with caution in neonates; hypertrophic pyloric stenosis and life-threatening episodes of ventricular tachycardia associated with prolonged QTc interval have been reported. High potential for interaction with many ARVs and other drugs. |

| Ethambutol (Myambutol) |

Tablets:

|

Less Frequent:

|

|

Requires dose adjustment in patients with impaired renal function. Take with food to minimize gastric irritation. Monitor visual acuity and red-green color discrimination regularly. Monitor renal function, LFTs, and CBC. Avoid concomitant use of drugs with neurotoxicity. |

| Ethionamide (Trecator-SC) |

Tablets:

|

Less Frequent:

|

More Frequent:

|

Avoid use of other neurotoxic drugs that could increase potential for peripheral neuropathy and optic neuritis. Administration of pyridoxine may alleviate peripheral neuritis. Take with food to minimize gastric irritation. Monitor LFTs, glucose, and thyroid function. Perform periodic ophthalmologic exams. |

| Fluconazole (Diflucan) |

Oral Suspension:

|

Less Frequent:

|

More Frequent:

|

Can be given orally without regard to meals. Shake suspension well before dosing. Requires dose adjustment in patients with impaired renal function. IV administration should be administered over 1–2 hours at a rate ≤200 mg/hour. Daily dose is the same for oral and IV administration. Multiple potential drug interactions Monitor periodic LFTs, renal function, and CBC. |

| Flucytosine (Ancobon) |

Capsules:

|

More Frequent:

|

|

Monitor serum concentrations and adjust dose to maintain therapeutic levels and minimize risk of bone marrow suppression. Requires dose adjustment in patients with impaired renal function; use with extreme caution. Fatal aplastic anemia and agranulocytosis have been rarely reported. Oral preparations should be administered with food over a 15-minute period to minimize GI side effects Monitor CBC, LFTs, renal function, and electrolytes. |

| Foscarnet (Foscavir) | IV |

More Frequent:

|

Frequent:

|

Requires dose adjustment in patients with impaired renal function. Use adequate hydration to decrease nephrotoxicity. Avoid concomitant use of other drugs with nephrotoxicity. Monitor serum electrolytes, renal function, and CBC. Consider monitoring serum concentrations (TDM) IV solution of 24 mg/mL can be administered via central line but must be diluted to a final concentration not to exceed 12 mg/mL if given via peripheral line. Must be administered at a constant rate by infusion pump over ≥2 hours (or no faster than 1 mg/kg/minute). |

| Ganciclovir (Cytovene) |

Capsules:

|

More Frequent:

|

|

Requires dose adjustment in patients with renal impairment. Avoid other nephrotoxic drugs. IV infusion over at least 1 hour. In-line filter required. Maintain good hydration. Undiluted IV solution is alkaline (pH 11); use caution in handling and preparing solutions and avoid contact with skin and mucus membranes. Administer oral doses with food to increase absorption. Do not open or crush capsules. Monitor CBC, LFTs, renal function; conduct ophthalmologic examinations. |

| Interferon-alfa-2B (IFN-α-2B; Intron) | Parenteral (SQ or IV use) |

More Frequent:

|

More Frequent:

|

Severe adverse effects less common in children than adults. Toxicity dose-related, with significant reduction over the first 4 months of therapy. For non-life-threatening reactions, reduce dose or temporarily discontinue drug and restart at low doses with stepwise increases. If patients have visual complaints, an ophthalmologic exam should be performed to detect possible retinal hemorrhage or retinal artery or vein obstruction. Should not be used in children with decompensated hepatic disease, significant cytopenia, autoimmune disease, or significant pre-existing renal or cardiac disease. If symptoms of hepatic decompensation occur (ascites, coagulopathy, jaundice), IFN-α-2B should be discontinued. Reconstituted solution stable for 24 hours when refrigerated. Monitor CBC, renal function, LFTs, thyroid function, and glucose. |

| Isoniazid (Nydrazid) |

Oral Syrup:

|

More Frequent:

|

|

Take with food to minimize gastric irritation. Take ≥1 hour before aluminum-containing antacids. Hepatitis less common in children. Use with caution in patients with hepatic function impairment, severe renal failure, or history of seizures. Pyridoxine supplementation should be provided for all HIV-infected children. Monitor LFTs and periodic ophthalmologic examinations. |

| Itraconazole (Sporanox) |

Oral Solution:

|

Less frequent:

|

More Frequent:

|

Oral Solution:

IV infusion over 1 hour. Multiple potential drug interactions Monitor LFTs and potassium levels. Monitor serum concentrations (TDM) in severe infections. |

| Kanamycin | IV IM |

More Frequent:

|

N/A | Must be infused over 30 to 60 minutes to avoid neuromuscular blockade. Requires dose adjustment in patients with impaired renal function. Should monitor renal function and hearing periodically (e.g., monthly) in children on prolonged therapy. Monitor serum concentrations (TDM). Monitor renal function; conduct, hearing exams for patients receiving prolonged therapy. |

| Ketoconazole (Nizoral) |

Tablets:

|

Less Frequent:

|

Frequent:

|

Adverse GI effects occur less often when administered with food. Drugs that decrease gastric acidity or sucralfate should be administered ≥2 hours after ketoconazole. Disulfiram-like reactions have occurred in patients ingesting alcohol. Hepatotoxicity is an idiosyncratic reaction, usually reversible when stopping the drug, but rare fatalities can occur any time during therapy; more common in females and adults >40 years, but cases reported in children. High-dose ketoconazole suppresses corticosteroid secretion, lowers serum testosterone concentration (reversible). Multiple potential drug interactions. Monitor LFTs. |

| Mefloquine (Lariam) |

Tablets:

|

More Frequent:

|

|

Side effects less prominent in children. Administer with food and plenty of water. Tablets can be crushed and added to food; bitter tasting so administer with foods that can mask the taste Monitor LFTs. |

| Nitazoxanide (Alinia) |

Oral Suspension:

|

N/A |

More Frequent:

|

Should be given with food. Shake suspension well prior to dosing. |

| P-Aminosalicyclic Acid (Paser) |

Delayed Release Granules:

|

Rare:

|

|

Should not be administered to patients with severe renal disease. Drug should be discontinued at first sign of hypersensitivity reaction (rash, fever, and GI symptoms typically precede jaundice). Vitamin B12 therapy should be considered in patients receiving for >1 month. Administer granules by sprinkling on acidic foods such as applesauce or yogurt or a fruit drink like tomato or orange juice. Maintain urine at neutral or alkaline pH to avoid crystalluria. The granule soft “skeleton” may be seen in the stool. Monitor CBC and LFTs. |

| Pegylated Interferon Alfa-2A (Pegasys) |

Injection:

|

More Frequent:

|

More Frequent:

|

Toxicity dose-related. Dose modifications based on type and degree of toxicity. For non-life threatening reactions, reduce dose or temporarily discontinue drug and restart at low doses with stepwise increases. If patients have visual complaints, an ophthalmologic exam should be performed to detect possible retinal hemorrhage or retinal artery or vein obstruction. Should not be used in children with decompensated hepatic disease, significant cytopenia, autoimmune disease, or significant pre-existing renal or cardiac disease. If symptoms of hepatic decompensation occur (ascites, coagulopathy, jaundice),Peg- IFN-α-2A should be discontinued. Monitor CBC, renal function, LFTs, thyroid function, and glucose. Store vials and syringes in refrigerator. Protect from light. Administer SQ in abdomen or thigh. Rotate injection sites. |

| Pegylated Interferon Alfa-2B (Pegintron) |

Injection:

|

More Frequent:

|

More Frequent:

|

Toxicity dose-related. Dose modifications based on type and degree of toxicity. For non-life threatening reactions, reduce dose or temporarily discontinue drug and restart at low doses with stepwise increases. If patients have visual complaints, an ophthalmologic exam should be performed to detect possible retinal hemorrhage or retinal artery or vein obstruction. Should not be used in children with decompensated hepatic disease, significant cytopenia, autoimmune disease, or significant pre-existing renal or cardiac disease. If symptoms of hepatic decompensation occur (ascites, coagulopathy, jaundice),Peg- IFN-α-2A should be discontinued. Monitor CBC, renal function, LFTs, thyroid function, and glucose. Store vials and syringes in refrigerator. Protect from light. Administer SQ in abdomen or thigh. Rotate injection sites. |

| Pentamidine (Pentam) | IV Aerosol |

IV More Frequent:

More Frequent:

|

IV More Frequent:

More Frequent:

|

Rapid infusion may result in precipitous hypotension; IV infusion should be administered over ≥1 hour (preferably 2 hours). Cytolytic effect on pancreatic beta islet cells, leading to insulin release, can result in prolonged severe hypoglycemia (usually occurs after 5–7 days of therapy, but can also occur after the drug is discontinued); risk increased with higher dose, longer duration of therapy, and re-treatment within 3 months of prior treatment. Hyperglycemia and diabetes mellitus can occur up to several months after drug discontinued. Monitor LFTs, renal function, glucose, electrolytes, BP. Inhalation:

|

| Posaconazole (Noxafil) |

Oral Solution:

|

Less frequent:

|

|

Must be given with meals. Adequate absorption is dependent on food for efficacy. Monitor LFTs, renal function and electrolytes. Monitor serum drug concentrations (TDM). Shake suspension prior to dosing. |

| Primaquine |

Tablets:

|

More Frequent:

|

|

Take with meals or antacids to minimize gastric irritation. Store in a light-resistant container. Bitter taste. Monitor CBC. |

| Pyrazinamide |

Tablets:

|

More Frequent:

|

|

Avoid in patients with severe hepatic impairment. Reduce dose in patients with renal or hepatic impairment. Monitor LFTs and uric acid. |

| Pyrimethamine (Daraprim) |

Tablet:

|

Less Frequent:

|

|

To prevent hematologic toxicity, administer with leucovorin. Monitor CBC. |

| Quinidine | IV |

Serious:

|

Very Frequent:

|

EKG monitoring is standard of care. Do not give by bolus infusion. If EKG changes observed, slow infusion rate. Monitor CBC and LFTs. |

|

Ribavirin Virazole Powder for solution for nebulization Rebetol Oral capsules and oral solution Copegus, Ribasphere, Ribapak Oral tablets and capsules |

Powder for Solution for Nebulization:

|

|

|

Should not be used in patients with severe renal impairment. Should not be used as monotherapy for treatment of hepatitis C, but used in combination with IFN-α. Intracellular phosphorylation of pyrimidine nucleoside analogues (zidovudine, stavudine, zalcitabine) decreased by ribavirin, may have antagonism; use with caution. Enhances phosphorylation of didanosine; use with caution because of increased risk of pancreatitis/mitochondrial toxicity. Oral solution contains propylene glycol. Teratogenic/embryocidal. Contraindicated in pregnant women and their male partners. Avoid pregnancy for additional 6 months after treatment. Monitor CBC, renal function, LFTs, and thyroid function. Perform pregnancy tests regularly while on therapy. |

| Rifabutin (Mycobutin) |

Capsules:

|

More Frequent:

|

|

Preferably take on empty stomach, but may be administered with food in patients with GI intolerance. The contents of capsules may be mixed with applesauce if patient is unable to swallow capsule. May cause reddish to brown-orange color urine, feces, saliva, sweat, skin, or tears (can discolor soft contact lenses). Uveitis seen with high-dose rifabutin (i.e., adults >300 mg/ day), especially when combined with clarithromycin. Multiple potential drug interactions Use with caution in patients with renal or hepatic impairment. Monitor CBC, LFTs; conduct ophthalmologic examinations. Reduce dose in patients with renal impairment. |

| Rifampin (Rifadin) |

Oral Suspension:

|

Less Frequent:

|

|

Preferably take on empty stomach, but can be administered with food in patients with GI intolerance; take with full glass of water. Suspension formulation stable for 30 days. Shake well prior to dosing. May cause reddish to brown-orange color urine, feces, saliva, sweat, skin, or tears (can discolor soft contact lenses). Multiple potential drug interactions Use with caution in patients with hepatic impairment. Administer IV by slow infusion. Extravasation may cause local irritation and inflammation. Monitor CBC and LFTs. |

| Streptomycin | IM |

More Frequent:

|

|

Usual route of administration is deep IM injection into large muscle mass. For patients who cannot tolerate IM injections, dilute to 12–15 mg in 100 mL of 0.9% sodium chloride; must be infused over 30 to 60 minutes to avoid neuromuscular blockade. Requires dose adjustment in patients with impaired renal function. Monitor renal function and hearing periodically (e.g., monthly) in children on prolonged therapy. Monitor serum concentrations (TDM). |

| Sulfadiazine |

Tablet:

|

Rare:

|

|

Ensure adequate fluid intake to avoid crystalluria. Monitor CBC, renal function, and urinalysis. Monitor serum concentrations (TDM) if serious infection. |

| Trimethoprim-Sulfameth-oxazole (TMP-SMX) (Bactrim, Septra) |

Oral Suspension:

Single Strength:

|

More Frequent:

|

|

Requires dose adjustment in patients with impaired renal function. Maintain adequate fluid intake to prevent crystalluria and stone formation (take with full glass of water). Potential for photosensitivity skin reaction with sun exposure. IV infusion over 60 to 90 minutes Monitor CBC, renal function. |

| Valacyclovir (Valtrex) |

Tablets:

|

Rare:

|

More Frequent:

|

Thrombotic thrombocytopenia purpura/hemolytic uremic syndrome has been reported in HIV-infected adults with advanced disease receiving high (i.e., 8 g/day) but not low doses. Monitor CBC and renal function. |

| Valganciclovir (Valcyte) |

Tablets:

|

More Frequent:

|

|

Requires dose adjustment in patients with renal impairment. Avoid other nephrotoxic drugs. Tablets should not be broken or crushed. Monitor CBC and renal function. Potentially teratogenic and carcinogenic. |

| Voriconazole (VFEND) |

Tablet:

|

Less Frequent:

|

More Frequent:

|

Oral tablets should be taken 1 hour before or after a meal. Shake oral suspension well prior to dosing. Maximum IV infusion rate 3 mg/kg/hour over 1 to 2 hours. Oral administration to patients with impaired renal function if possible (accumulation of IV vehicle occurs in patients with renal insufficiency) Dose adjustment needed if hepatic insufficiency. Visual disturbances common (>30%) but transient and reversible when drug is discontinued. Multiple potential drug interactions Monitor renal function, electrolytes, and LFTs Consider monitoring serum concentrations (TDM). |

The toxicities listed in the table have been selected based on their potential clinical significance and are not inclusive of all side effects reported for a particular drug.

Key to Acronyms: ARV = antiretroviral; BP = blood pressure; BUN = blood urea nitrogen; CBC = complete blood count; CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; CNS = central nervous system; Cr = creatinine; CrCl = creatinine clearance; EKG = electrocardiogram; G6PD = Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase; GI = gastrointestinal; IFN- = interferon alfa; IM = intramuscular; IND = investigational new drug; IV = intravenous; LFT = liver function test; SJS = Stevens-Johnson Syndrome; SMX = sulfamethoxazole; SQ = subcutaneous; TDM = therapeutic drug monitoring; TMP = trimethoprim

Table 5.

Significant Drug Interactions for Drugs Used to Treat or Prevent Opportunistic Infections (Last updated November 6, 2013; last reviewed November 6, 2013)