Abstract

There has been increasing evidence that ascending thoracic aortic aneurysms (TAAs) protect against atherosclerosis. However, there have been no studies examining the relationship between ascending TAAs and clinical endpoints of atherosclerosis, such as stroke or peripheral arterial disease. In this study, we aim to characterize the relationship between TAAs and a specific clinical endpoint of atherosclerosis, myocardial infarction (MI). We compared prevalence of coronary artery disease (CAD) and MIs in 487 patients who underwent surgical repair for ascending TAAs to 500 control patients who did not have an ascending TAA. Multivariate binary logistic regression was used to calculate the odds of having MI if a patient had an ascending TAA versus any of several MI risk factors. There was a significantly lower prevalence of CAD and MI in the ascending TAA group than in the control TAA group. The odds of having a MI if a patient had a MI risk factor were all > 1 (more likely to have a MI), with the lowest statistically significant odds ratio being 1.54 (age; p = 0.001) and the highest being 14.9 (family history of MI; p < 0.001). The odds ratio of having a MI if a patient had an ascending TAA, however, was near 0 at 0.05 (p < 0.001). This study provides evidence that ascending TAAs protect against MIs, adding further support to the hypothesis that ascending TAAs protect against atherosclerotic disease.

Keywords: atherosclerosis, cardiovascular risk factors, coronary artery, myocardial infarction, aneurysm, acute coronary syndrome, infarction

Approximately 10.4 per 100,000 people in the United States each year are diagnosed with a thoracic aortic aneurysm (TAA), a silent disease that may eventuate in life-threatening aortic dissection or rupture without diagnosis and surgical intervention.1 2 Recently, however, we and others have shown that there may be a silver lining to ascending TAA disease. As opposed to abdominal aortic aneurysms, which have been widely shown to be associated with atherosclerosis,3 4 5 6 there has been increasing evidence that ascending TAAs are actually negatively associated with atherosclerosis.

Nakashima et al looked at the autopsies of 111 aortic dissection patients and showed that there was a lower incidence of atherosclerosis in the type A dissection patients versus the type B dissection patients.7 Studies have also shown a lower incidence of coronary artery disease (CAD) in patients with ascending or aortic arch TAAs than in abdominal aortic aneurysm patients.8 9 10

At our institution, we previously observed that the femoral arteries of patients undergoing surgery for ascending TAAs, which were commonly exposed for cannulation for cardiopulmonary bypass, were almost invariably soft and pliable, like a child or young adult.11 This clinical observation was followed by a study in which we showed that ascending TAA patients have less extensive systemic atherosclerotic disease than patients who do not have ascending TAAs based on total body calcification scores, a late indicator of atherosclerosis.12 We then looked at carotid intima-media thickness (IMT), an early indicator of atherosclerosis; we found ascending TAA patients to have lower carotid IMTs than individuals without ascending TAAs, providing further evidence that ascending TAAs protect against atherosclerosis.13

While these studies have examined the relationship between ascending TAAs and atherosclerosis, we are not aware of any clinical studies investigating the relationship of ascending TAAs with clinical endpoints of atherosclerosis, such as myocardial infarctions (MIs). This relationship is important, as it would provide real clinical significance to the hypothesis that ascending TAAs protect against atherosclerotic disease. This study aims to investigate precisely that relationship. We compare the prevalence of CAD and MIs between 487 ascending TAA patients and 500 control patients, calculating specifically the odds of having a MI if a patient had an ascending TAA versus any of several known MI risk factors. In this way, we aim to add important clinical outcome information regarding whether or not ascending TAAs actually protect against sequelae of atherosclerosis.

Method

This study was approved by the Yale University School of Medicine Human Investigative Committee (number 1205010178).

Patient Population

The ascending TAA group (referred to as the aneurysm group from here on) consisted of 487 patients who had undergone ascending TAA surgery between January 2007 and July 2012. Seven had a history of type A dissection repair and six had a chronic type A dissection. The remainder had nondissecting aneurysms. Eight patients had Marfan syndrome. There were 329 males and 158 females. Mean age was 61.0 years with a range of 18 to 89 years.

The control group consisted of 500 randomly chosen patients who went to the adult emergency room between January 2007 and July 2012 with a chief complaint of abdominal pain and were admitted. We chose abdominal pain patients as they encompass a whole range of ages, races, and both sexes, and are unbiased with respect to CAD and aneurysm disease. No patients in the control group were diagnosed with MI or any atherosclerosis-related conditions, such as intestinal ischemia and arterial embolism, during that admission, or with aneurysms (abdominal or thoracic). Patients under the age of 18 and patients with a history of TAA were excluded. There were 324 males and 176 females. Mean age was 62.3 years with a range from 19 to 94 years.

Myocardial Infarction and Risk Factors

MI was noted for each patient based on his/her medical record (MI diagnosed during that admission or a documented history of MI). Known CAD was determined based on medical records. The following risk factors for MI were assessed: age, gender, race, body mass index (BMI) (at the time of admission or surgery), family history (first degree relative who suffered an MI), hypertension (based on medical records or antihypertensive treatment), dyslipidemia (based on medical records or use of lipid medications), diabetes mellitus (based on medical records), and tobacco smoking (past or present).

Statistical Analysis

Analyses of dichotomous variables were done using χ 2 tests. Mann-Whitney U tests were used to analyze continuous variables as normality could not be established. Multivariate binary logistic regression was used to calculate the odds of having a MI if a patient had an ascending TAA as opposed to known MI risk factors, while controlling for all the other factors. p-Values < 0.05 were considered significant. Statistical analyses were done using SPSS Statistics version 21 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY) and were reviewed by Yale Center for Analytical Sciences.

Results

Patient Demographics

Table 1 presents the demographic data for the control group and for the aneurysm group. There were a significantly smaller number of Caucasians in the control group than in the aneurysm group (385 vs. 448, p < 0.001; Caucasian race, though, is not a known risk factor for MIs), and a significantly greater number of African Americans in the control group than in the aneurysm group (79 vs. 14, p < 0.001). The mean BMI was significantly lower in the control group than in the aneurysm group (26.8 vs. 28.6, p < 0.001), and there were also a significantly greater number of patients with diabetes mellitus in the control group versus the aneurysm group (154 vs. 38, p < 0.001). There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in any other characteristic.

Table 1. Patient demographics.

| Variable | Control | Aneurysm | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 500 | 487 | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 324 | 329 | 0.36 |

| Female | 176 | 158 | |

| Mean age ± SD, y | 62.3 ± 14.6 | 61.0 ± 13.2 | 0.28 |

| Race | |||

| Caucasian | 385 | 448 | < 0.001 |

| African American | 79 | 14 | < 0.001 |

| Hispanic | 26 | 14 | 0.06 |

| Oriental/Asian | 3 | 7 | 0.19 |

| Other | 7 | 3 | 0.22 |

| Mean BMI ± SD | 26.8 ± 5.81 | 28.6 ± 5.02 | < 0.001 |

| Family history of MI | 73 | 86 | 0.19 |

| Hypertension | 362 | 325 | 0.053 |

| Dyslipidemia | 206 | 207 | 0.68 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 154 | 38 | < 0.001 |

| Smoking | 199 | 205 | 0.46 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; MI, myocardial infarction; SD, standard deviation; y, years.

Outcome Analysis

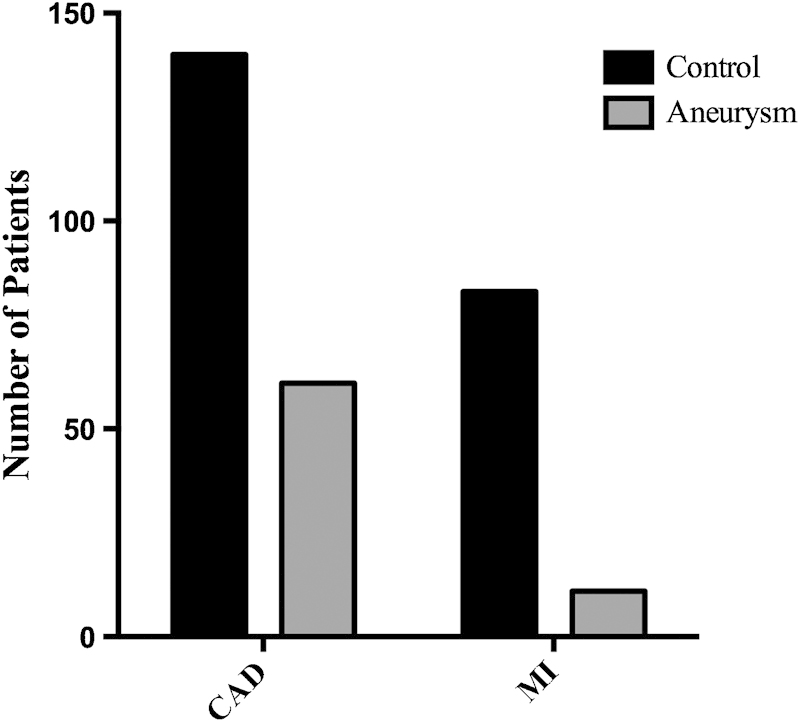

There were significantly less patients in the aneurysm group with a history of CAD than in the control group (61 vs. 140, p < 0.001). There were also significantly fewer patients in the aneurysm group with a history/diagnosis of MI than in the control group (11 vs. 83, p < 0.001) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Prevalence of coronary artery disease and myocardial infarctions. There was a significantly lower prevalence of CAD and MIs in the aneurysm group than in the control group. There were 61 patients in the aneurysm group who had CAD (p < 0.001) versus 140 in the control group. There were 11 patients in the aneurysm group who have had a MI versus 83 in the control group (p < 0.001). CAD, coronary artery disease; MI, myocardial infarction.

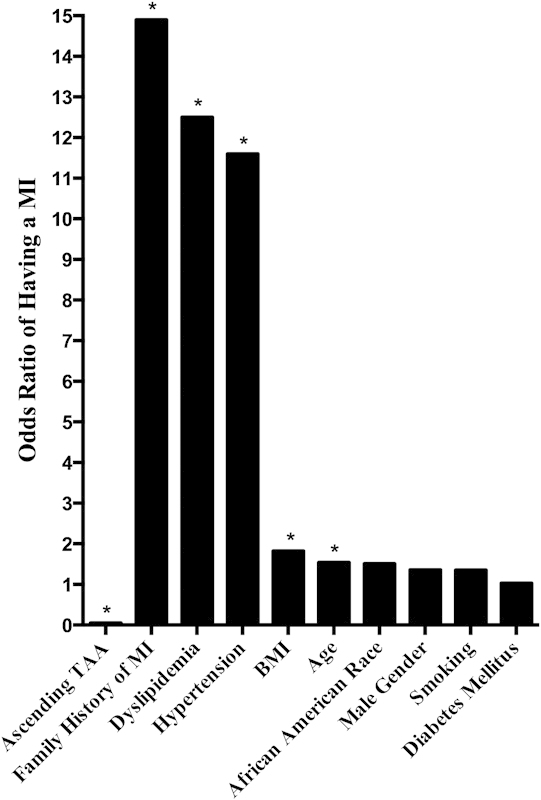

Table 2 shows the odds ratios for having an acute MI in patients with either ascending TAAs or a MI risk factor. The odds ratio for each variable was calculated while controlling for all other variables. This means that the odds of having a MI if a patient had an ascending TAA were calculated while controlling for all known MI risk factors. The odds ratios for African American race and diabetes mellitus, the two characteristics that were significantly more prevalent in the control group, were nonsignificant (p > 0.05). The drastic difference in the odds ratio for having a MI when a patient had an ascending TAA versus any MI risk factor is depicted in Fig. 2. All the risk factors for having a MI had odds ratios of > 1 (more likely to have a MI), understandably. The lowest statistically significant odds ratio was 1.54 for age (p = 0.001) and the highest was 14.9 family history of MI (p < 0.001). The odds ratio for having a MI if a patient had an ascending TAA, however, was almost 0 at 0.05 (p < 0.001).

Table 2. Odds ratio of having a myocardial infarction.

| Variable | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Ascending TAA | 0.05 (0.02–0.11) | < 0.001 |

| Family History of MI | 14.9 (7.58–29.4) | < 0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 12.5 (5.27–29.6) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 11.6 (2.17–61.7) | 0.004 |

| BMI | 1.82 (1.10–3.00) | 0.02 |

| Age | 1.54 (1.20–1.99) | 0.001 |

| African American race | 1.51 (0.65–3.51) | 0.34 |

| Male gender | 1.36 (0.72–2.59) | 0.34 |

| Smoking | 1.35 (0.74–2.46) | 0.32 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.03 (0.55–1.95) | 0.92 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; MI, myocardial infarction; TAA, thoracic aortic aneurysm.

Note: Age is in 10-year intervals. BMI is in 10-unit intervals.

Fig. 2.

Likelihood of having a myocardial infarction. The odds ratio of having a MI when a patient had an ascending TAA versus MI risk factors. Age is in 10-year intervals and BMI is in 10-unit intervals. Note the drastic difference in odds ratios when a patient had an ascending TAA compared with when a patient had a MI risk factor. *Statistically significant (p <0.05). BMI, body mass index; MI, myocardial infarction; TAA, thoracic aortic aneurysm.

Discussion

Prevalence of Acute Myocardial Infarctions

We are not aware of any other clinical study that examines the relationship between ascending TAAs and clinical endpoints of atherosclerosis. Looking at the clinical endpoint of MI, we found a significantly lower prevalence of MIs in the aneurysm group than in the control group. Not surprisingly, and in line with results found in previous studies, we also found a significantly lower prevalence of CAD in the aneurysm group versus the control group.8 9 10 12

There were differences between the two groups in some risk factors, namely, African American race, BMI, and diabetes mellitus. However, the mean BMI of the control group was actually lower than that of the aneurysm, thus biasing the aneurysm group to have a greater prevalence of MI, which turned out not to be the case and provided further strength to our findings. As for African American race and diabetes mellitus, we understood that there were more patients in the control group than in the aneurysm group with these risk factors, and so we did not just rely on our analyses of the prevalence of MIs in each group.

Likelihood of Having an Acute Myocardial Infarction

We did a multivariate binary logistic regression, which looked at the odds of having a MI if a patient had a variable, either ascending TAA or one of the MI risk factors, independent of all the other variables. So when calculating the odds ratio of having a MI if a patient had an ascending TAA, African American race and diabetes mellitus (the two risk factors more prevalent in the control group), along with all the other MI risk factors, were controlled for. Also, the odds ratio of having a MI if a patient was African American or had diabetes mellitus was not significant (p > 0.05). On the other hand, the odds ratio of having a MI if a patient had an ascending TAA was significant (p < 0.001) and was 0.05. This not only means that a person with an ascending TAA had an almost zero likelihood of having a MI, but also that the odds of a patient with an ascending TAA having a MI was over 20 times less than a patient with a risk factor for MI. In fact, we found that a patient with an ascending TAA was 298 times less likely to have a MI than if he/she had a family history of MI, 250 times less likely to have a MI than if he/she had dyslipidemia, and 232 times less likely to have a MI than if he/she had hypertension. We therefore, provide very strong evidence showing that ascending TAAs protect against having a MI. This provides additional evidence for and also clinical significance to the hypothesis that ascending TAA protects against atherosclerotic disease.

In addition to increasing clinical evidence supporting the protective effect that ascending TAAs have against atherosclerosis, there have also been molecular and genetic studies that provide support for this hypothesis. Transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) have both been shown to have both proaneurysmal and antiatherogenic effects.14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 The mechanism by which TGF-β has been shown to be antiatherogenic includes not just protecting against the development and growth of atherosclerotic lesions, but also protecting against atherosclerotic plaque rapture.22 23 24 Genetics studies, too, have shown that TGF-β and MMPs are both proaneurysmal and antiatherogenic, with some studies showing that polymorphisms that decrease TGF-β levels are found in MI patients.25 26 27 28 29 30 31 There is therefore a molecular and genetic basis not just for the protective effect that ascending TAAs have against atherosclerosis, but also against MIs specifically.

There have been investigations into taking advantage of the antiatherogenic effects of TGF-β and MMPs for new antiatherosclerotic therapies. Triphenylethylene-derived drugs that increase TGF-β levels, such as tamoxifen and raloxifene, for example, have been proposed as potential therapies for CAD.32 33 However, further studies about the protective effect of ascending TAAs against atherosclerosis and the mechanisms that underlie it are needed in the search for novel antiatherosclerotic therapies.

A limitation of our study is that our control group consisted of patients who went to the emergency room. They therefore may not represent the general population, as they went to the emergency room for a health issue. Finding a perfect control group for such a study is difficult; however we believe that the control group that we have chosen is appropriate. We choose patients who came in with a chief complaint of abdominal pain, which is not significantly associated with MIs and is unbiased with respect to CAD and aneurysm disease; also, no patient in the control group was diagnosed with a MI, any atherosclerotic-related disease, or aneurysmal disease during that admission. Another limitation is our definition of family history of MI, which was having a first-degree relative who has had a MI regardless of what age the MI occurred. This may have overestimated the prevalence of patients with a family history of MIs, which could have led to a higher odds ratio of having a MI. However, even if the odds ratio was inflated by 10 times, the odds ratio for family history would still have been 1.50, 30 times higher than the odds ratio for ascending TAA. There were also significantly more patients in the control group who had diabetes, which could be associated with the number of MIs that occurred. The number of diabetic patients in control group was actually so striking when compared with the aneurysm group that it makes us wonder if ascending TAA patients have a decreased prevalence of diabetes. Also, when calculating the odds ratios of having a MI, the odds ratio calculated for diabetes was not significant.

Conclusion

In this study, we strengthen the support for the hypothesis that ascending TAAs protect against atherosclerosis by looking at the relationship between ascending TAAs and a clinical endpoint of atherosclerosis, MI, which has not been looked at before. There was a decreased prevalence of CAD and MIs in patients with ascending TAAs compared with patients without ascending TAAs. There was also a near zero odds of having a MI if one had an ascending TAA—an over 20 times less likelihood than if one had a risk factor for MI. We therefore, provide evidence showing that ascending TAAs have a protective effect against MIs. We hope that, in contributing to the understanding of the protective relationship that ascending TAAs have against atherosclerosis, we also promote investigation of new antiatherosclerotic therapies that exploit the proaneurysmal yet antiatherogenic molecular mechanisms behind this protective effect.

References

- 1.Ramanath V S, Oh J K, Sundt T M III, Eagle K A. Acute aortic syndromes and thoracic aortic aneurysm. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84(5):465–481. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)60566-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuzmik G A, Sang A X, Elefteriades J A. Natural history of thoracic aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2012;56(2):565–571. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2012.04.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buxton D B. Molecular imaging of aortic aneurysms. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging . 2012;5(3):392–399. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.112.973727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cornuz J, Sidoti Pinto C, Tevaearai H, Egger M. Risk factors for asymptomatic abdominal aortic aneurysm: systematic review and meta-analysis of population-based screening studies. Eur J Public Health . 2004;14(4):343–349. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/14.4.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnsen S H, Forsdahl S H, Singh K, Jacobsen B K. Atherosclerosis in abdominal aortic aneurysms: a causal event or a process running in parallel? The Tromsø study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol . 2010;30(6):1263–1268. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.203588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaschina E, Scholz H, Steckelings U M. et al. Transition from atherosclerosis to aortic aneurysm in humans coincides with an increased expression of RAS components. Atherosclerosis . 2009;205(2):396–403. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakashima Y, Kurozumi T, Sueishi K, Tanaka K. Dissecting aneurysm: a clinicopathologic and histopathologic study of 111 autopsied cases. Hum Pathol . 1990;21(3):291–296. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(90)90229-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agmon Y, Khandheria B K, Meissner I. et al. Is aortic dilatation an atherosclerosis-related process? Clinical, laboratory, and transesophageal echocardiographic correlates of thoracic aortic dimensions in the population with implications for thoracic aortic aneurysm formation. J Am Coll Cardiol . 2003;42(6):1076–1083. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00922-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kojima S, Suwa S, Fujiwara Y. et al. Incidence and severity of coronary artery disease in patients with acute aortic dissection: comparison with abdominal aortic aneurysm and arteriosclerosis obliterans [in Japanese] J Cardiol . 2001;37(3):165–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Islamoğlu F, Atay Y, Can L. et al. Diagnosis and treatment of concomitant aortic and coronary disease: a retrospective study and brief review. Tex Heart Inst J . 1999;26(3):182–188. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ayyash B, Tranquilli M, Elefteriades J A. Femoral artery cannulation for thoracic aortic surgery: safe under transesophageal echocardiographic control. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg . 2011;142(6):1478–1481. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Achneck H, Modi B, Shaw C. et al. Ascending thoracic aneurysms are associated with decreased systemic atherosclerosis. Chest . 2005;128(3):1580–1586. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.3.1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hung A, Zafar M, Mukherjee S, Tranquilli M, Scoutt L M, Elefteriades J A. Carotid intima-media thickness provides evidence that ascending aortic aneurysm protects against systemic atherosclerosis. Cardiology . 2012;123(2):71–77. doi: 10.1159/000341234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grainger D J. Transforming growth factor β and atherosclerosis: so far, so good for the protective cytokine hypothesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol . 2004;24(3):399–404. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000114567.76772.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nataatmadja M West J West M Overexpression of transforming growth factor-β is associated with increased hyaluronan content and impairment of repair in Marfan syndrome aortic aneurysm Circulation 2006114(1, Suppl):I371–I377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neptune E R, Frischmeyer P A, Arking D E. et al. Dysregulation of TGF-beta activation contributes to pathogenesis in Marfan syndrome. Nat Genet . 2003;33(3):407–411. doi: 10.1038/ng1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCaffrey T A. TGF-betas and TGF-β receptors in atherosclerosis. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev . 2000;11(1-2):103–114. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(99)00034-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Silence J, Collen D, Lijnen H R. Reduced atherosclerotic plaque but enhanced aneurysm formation in mice with inactivation of the tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 (TIMP-1) gene. Circ Res . 2002;90(8):897–903. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000016501.56641.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lemaître V, O'Byrne T K, Borczuk A C, Okada Y, Tall A R, D'Armiento J. ApoE knockout mice expressing human matrix metalloproteinase-1 in macrophages have less advanced atherosclerosis. J Clin Invest. 2001;107(10):1227–1234. doi: 10.1172/JCI9626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koullias G J Ravichandran P Korkolis D P Rimm D L Elefteriades J A Increased tissue microarray matrix metalloproteinase expression favors proteolysis in thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections Ann Thorac Surg 20047862106–2110., discussion 2110–2111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Silence J, Lupu F, Collen D, Lijnen H R. Persistence of atherosclerotic plaque but reduced aneurysm formation in mice with stromelysin-1 (MMP-3) gene inactivation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol . 2001;21(9):1440–1445. doi: 10.1161/hq0901.097004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCaffrey T A, Consigli S, Du B. et al. Decreased type II/type I TGF-beta receptor ratio in cells derived from human atherosclerotic lesions. Conversion from an antiproliferative to profibrotic response to TGF-beta1. J Clin Invest . 1995;96(6):2667–2675. doi: 10.1172/JCI118333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mallat Z, Gojova A, Marchiol-Fournigault C. et al. Inhibition of transforming growth factor-beta signaling accelerates atherosclerosis and induces an unstable plaque phenotype in mice. Circ Res . 2001;89(10):930–934. doi: 10.1161/hh2201.099415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lutgens E, Gijbels M, Smook M. et al. Transforming growth factor-beta mediates balance between inflammation and fibrosis during plaque progression. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol . 2002;22(6):975–982. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000019729.39500.2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ye S, Eriksson P, Hamsten A, Kurkinen M, Humphries S E, Henney A M. Progression of coronary atherosclerosis is associated with a common genetic variant of the human stromelysin-1 promoter which results in reduced gene expression. J Biol Chem . 1996;271(22):13055–13060. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.22.13055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vaughan C J, Casey M, He J. et al. Identification of a chromosome 11q23.2-q24 locus for familial aortic aneurysm disease, a genetically heterogeneous disorder. Circulation . 2001;103(20):2469–2475. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.20.2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Humphries S E, Luong L A, Talmud P J. et al. The 5A/6A polymorphism in the promoter of the stromelysin-1 (MMP-3) gene predicts progression of angiographically determined coronary artery disease in men in the LOCAT gemfibrozil study. Lopid Coronary Angiography Trial. Atherosclerosis . 1998;139(1):49–56. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(98)00053-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andreotti F, Porto I, Crea F, Maseri A. Inflammatory gene polymorphisms and ischaemic heart disease: review of population association studies. Heart . 2002;87(2):107–112. doi: 10.1136/heart.87.2.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kempf K, Haltern G, Füth R. et al. Increased TNF-alpha and decreased TGF-beta expression in peripheral blood leukocytes after acute myocardial infarction. Horm Metab Res . 2006;38(5):346–351. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-925403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yokota M, Ichihara S, Lin T L, Nakashima N, Yamada Y. Association of a T29—>C polymorphism of the transforming growth factor-beta1 gene with genetic susceptibility to myocardial infarction in Japanese. Circulation . 2000;101(24):2783–2787. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.24.2783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koch W, Hoppmann P, Mueller J C, Schömig A, Kastrati A. Association of transforming growth factor-beta1 gene polymorphisms with myocardial infarction in patients with angiographically proven coronary heart disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol . 2006;26(5):1114–1119. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000217747.66517.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grainger D J, Metcalfe J C. Tamoxifen: teaching an old drug new tricks? . Nat Med . 1996;2(4):381–385. doi: 10.1038/nm0496-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saitta A, Morabito N, Frisina N. et al. Cardiovascular effects of raloxifene hydrochloride. Cardiovasc Drug Rev . 2001;19(1):57–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-3466.2001.tb00183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]