Abstract

STAT5A and STAT5B are highly homologous proteins whose distinctive roles in human immunity remain unclear. However, STAT5A sufficiency cannot compensate for STAT5B defects, and human STAT5B deficiency, a rare autosomal recessive primary immunodeficiency, is characterized by chronic lung disease, growth failure and autoimmunity associated with regulatory T cell (Treg) reduction. We therefore hypothesized that STAT5A and STAT5B play unique roles in CD4+ T cells. Upon knocking down STAT5A or STAT5B in human primary T cells, we found differentially regulated expression of FOXP3 and IL-2R in STAT5B knockdown T cells and down-regulated Bcl-X only in STAT5A knockdown T cells. Functional ex vivo studies in homozygous STAT5B-deficient patients showed reduced FOXP3 expression with impaired regulatory function of STAT5B-null Treg cells, also of increased memory phenotype. These results indicate that STAT5B and STAT5A act partly as non-redundant transcription factors and that STAT5B is more critical for Treg maintenance and function in humans.

Keywords: STAT5, Regulatory T cells (Treg), T cell development

1. Introduction

The signal transducers and activators of transcription (STAT) family of proteins mediate a number of biological activities including immune cell regulation and responsiveness to growth factors. STAT5A and STAT5B are highly homologous proteins encoded by separate genes located on chromosome 17q11.2. Human STAT5A and STAT5B proteins differ by 7 amino acids in the DNA binding domain and 20 amino acids in their carboxy termini in addition to 6 amino acids at the beginning of the transactivating domain [1,2]. While STAT5A and STAT5B may bind the same targets, differential effects may arise due to differential expression or differences in kinetics of DNA binding [3].

Murine studies have highlighted the role for both STAT5A and STAT5B in cytokine signaling and T cell homeostasis [4–7], whereas the roles of STAT5A and STAT5B in regulating human immune responses in vivo remain poorly understood. Previous studies have examined the immune phenotype of human STAT5B-deficiency, a rare severe primary immunodeficiency characterized by growth failure, chronic lung disease, atopic dermatitis, infections of the skin and respiratory tract and/or autoimmune disease [8]. STAT5B homozygous deficient patients have high T cell activation, hypergammaglobulinemia, high IgE levels and marked deficiency in insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-1 production [8,9]. Additionally, IL-2 signaling directly targets the human FOXP3 gene in CD4+ CD25hi Treg requiring the binding of STAT5 proteins [10]. Indeed, in one patient with a homozygous STAT5B mutation resulting in undetectable STAT5B but normal STAT5A expression, we previously showed a decreased numbers of Treg with low levels of FOXP3 expression and impaired suppressive function in vitro [11]. This single case study demonstrated a role for STAT5B in IL-2-mediated CD25 regulation of Treg that is non-redundant with a role for STAT5A. The finding of a reduced number of Treg implies that human Treg require the activation of at least STAT5B; it is unclear at present whether there is a role for STAT5A in human Treg development.

Treg comprise a population of T cells that suppress T cell function and attenuate immune responses against self and non-self antigens. Naturally arising Treg are produced in the thymus, whereas adaptive Treg are induced from naïve T cells after antigen exposure in the periphery. Although a marker unique to Treg populations has not been identified, Treg typically are composed of CD4+ CD25hi T cells that express the transcription factor FOXP3, which is necessary and sufficient for Treg suppressive function [12]. Vukmanovic-Stejiv et al. demonstrated that human CD4+ CD25hi Treg can also be induced by rapid turnover from the memory T cell pool [13]. Whether there is differential regulation between STAT5A and STAT5B of human Treg in the periphery vs. Treg development in the thymus has not been determined. Because STAT5B-deficient patients have been found to have normal levels of STAT5A protein expression but reduced Treg numbers and function, short stature and reduced IL-2R expression (reviewed in [14]), we hypothesized that human STAT5B could function non-redundantly with human STAT5A to regulate FOXP3, IGF-1, and IL-2R, and possibly act separately on thymic Treg development or peripheral Treg induction and maintenance.

To begin to address these questions, we utilized two different approaches: in vitro siRNA-mediated knockdown of STAT5A or STAT5B in human primary T cells and ex vivo analysis of transcriptional profiling, immunophenotyping, functional assays and thymic origin of Treg cells purified from STAT5B−/− patients with diverse mutations leading to STAT5B deficiency with different severity of symptoms and clinical phenotypes.

The current study demonstrates at the molecular level in human cells a differentiation between STAT5A and STAT5B-dependent regulation of genes relevant for immune homeostasis and specifically shows that FOXP3, and consequently Treg suppressive function, is downstream of STAT5B signaling, whereas peripheral Treg induction from memory CD4+ T cells is STAT5B-independent.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Patients

All subjects consented under Stanford approved IRB according to ICH/GCP guidelines. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated as in [8] from 6 STAT5B homozygous deficient patients ranging in age from 6 to 31 years of age, 1 heterozygote (A630Pwt/−), and healthy controls age-matched within 6 months. Healthy controls were obtained from Stanford Hospital and Clinics. The STAT5B-deficient patients have one of the following genotypes: 1× p.A630P−/−, 1× c.1103insC−/−, 2× c.1680delG−/−, 1× SNPs3′UTR and c.424_427del. Absolute numbers of CD3+ T cell, CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, NK cells and Treg, as well as total IgG, IgE, were determined when possible for each patient and are noted in Table 1. No subject had an acute infection and/or was medicated with antiproliferative or immunosuppressive agents within 1 week of the blood draw. This study was approved by the Stanford Administrative panel on Human Subjects in Medical Research Institutional Review Board.

Table 1.

Characteristics of STAT5B-deficient patients.

| Characteristics | #1 (A630P−/−) | #2 (p.R152X−/−) | #3 (1680delG−/−)a | #4 (1680delG−/−)a | #5 (1102−/−) | #6 SNPs3′UTR | Healthy controls N= 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | F | F | F | F | M | F | 50% M, 50% F |

| Age (years) | 16.5 | 15 | 10 | 12 | 31 | 6.5 | Age matched within 6 months |

| Mean 15 years (range 6–31 years) | |||||||

| Autoimmune disease | + Abs to BEC | +Abs to platelets and to BEC | SJIA thyroiditis | Thyroiditis | No | No | No |

| Immunological evaluation | |||||||

| PBMC protein expression | STAT5A yes | STAT5A yes | STAT5A yes | STAT5A yes | STAT5A yes | STAT5A yes | STAT5A yes |

| STAT5B no | STAT5B no | STAT5B no | STAT5B no | STAT5B no | STAT5B low | STAT5B yes | |

| IgG, mg/dL | 2500 | 2530 | 3015 | 1874 | 2450 | 1860 | Mean 950 (range 670–1025) |

| IgE, IU/mL | 874 | 631 | 298 | 192 | 279 | 245 | 13 (0.35–20) |

| CD3+ (total T cells per μL) | 280 | 1274 | 591 | 405 | 620 | 540 | 4100 (3700–4400) |

| CD4+ (T helper cells per μL) | 160 | 783 | 342 | 276 | 456 | 360 | 2500 (2100–2700) |

| CD8+ (T sup. cells per μL) | 105 | 473 | 114 | 120 | 275 | 184 | 1600 (1500–1700) |

| CD16+56+ (NK cells) | 233 | 18 | 37 | 41 | 115 | 213 | 209 (196–240) |

| Absolute count Treg per μL | 2 | 8 | 3 | 2 | 12 | 24 | 35 |

| (% Treg frequency) | (1) | (1) | (1) | (1) | (3) | (7) | (1) |

| % Treg function | 13 | 50 | 45 | 47 | 72 | 77 | 99 (97–100) |

Abbreviations: Abs, antibodies; BEC, bronchial epithelial cells; SJIA, systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis; ND, not yet determined.

Indicates patients are siblings.

2.2. Cell purification

PBMCs and CD4+ T cells were isolated from whole blood using Ficoll separation and RosetteSep CD4+ enrichment kit (StemCell Technologies). CD4+CD25hiCD127low cells were separated using antigen-coated immunomagnetic bead cell separation (Miltenyi Biotec) and had >90% purity. For Treg suppression assays, CD4+ T cells were incubated with antibodies recognizing CD127 and CD25 (BD Biosciences), and subsequently sorted by flow cytometry on a FACS Aria (BD Biosciences) into CD4+CD25hiCD127low/− Treg and CD4+CD25− effector T cells.

2.3. Quantitative PCR

RNA was isolated from 200,000 peripheral blood cells using RNeasy kits (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. For cDNA synthesis, 500 ng of total RNA was transcribed with cDNA transcription reagents (Applied Biosystems) using random hexamers, according to the manufacturer's protocol. Gene expression was measured in real time using primers and other reagents purchased from Applied Biosystems and SuperArray. All PCR assays were performed in triplicate. Data were presented as relative fold expression of the candidate gene to the expression of the housekeeping gene β-glucuronidase.

2.4. RNA interference and Western blot

CD4+ cells were resuspended at 2 × 105 cells/10 μL in T buffer (Invitrogen) with a 2 nmol cocktail of equal volume Stealth Select siRNA for STAT5A or STAT5B (Invitrogen). Cells were transfected on a Neon Transfection System (Invitrogen) at a preoptimized square pulse condition for STAT5A siRNA (1700 V, 25 ms, 1 pulse) or for STAT5B siRNA (1700 V, 30 ms, 1 pulse). To assess stability of the microporation transfection and long-term cell viability, cells were incubated in a flat-bottom 24-well plate in 490 μL RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) per well at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 1, 3, 5 or 7 days. No further stimulation was used. Viability was also assessed with or without 100 U/mL rhIL-2 (PeproTech). Data were normalized to those from cells transfected in T buffer with 2 nmol Negative Control Medium GC (Invitrogen). To assess knock-down by protein analysis, protein (15 μg/lane) from T cell blasts was electrophoresed, blotted, and probed with antibodies recognizing STAT5A (clone L20) or STAT5B (clone G-2,Santa Cruz Biotechnology) as described [15].

2.5. Flow cytometry and immune phenotyping

The following antibodies and cognate isotypes were purchased from BD Biosciences, unless otherwise indicated, and were used as per manufacturer's instructions: Live/dead, CD4 (SK3), CD25 (BC96), CD31 (MEC13.3), CD45RA (HI100), CD45RO (UCHL1), CD127 (HIL-7R-M21), FOXP3 (eBioscience, PCH-101), Ki67 (eBioscience, 20Raj1), and pSTAT5 (Cell Signaling, 9359). Cells were stained with surface markers, then fixed and permeabilized followed by a blocking step with 2% normal rat serum, and stained with intracellular Ki67 (eBioscience), FOXP3 (eBioscience), or isotype control mAb for 30 min. Cells were acquired with a FACS-calibur or LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star). As per our previously published methods [16], Treg were defined as live, CD4+CD25hiCD127low cells.

2.6. sjTREC content

Total cellular DNA was isolated from CD4+ T cells using a QIAamp DNA Mini kit (QIAGEN) and used in 20 μL real-time PCR reactions in 384-well plates analyzed in a 7900HT Fast Real Time PCR instrument (Applied Biosystems). Reactions included oligonucleotide primers and a TAMRA-FAM labeled internal probe for the δRec-ψJα signal joint [17]. Internal standards that were cloned from human thymocyte DNA by PCR included a 381-bp segment containing the δRec-ψJα signal joint (primers 5′-GAAAACAGCCTTTGGGACAC-3′ and 5′-GTGAC ATGGAGGGCTGAACT-3′; designed based on the homology of a rhesus macaque sjTREC sequence with human genomic sequences) and a 496-bp segment of the Cα region that is not affected by V(D)J recombination (primers 5′-ATCACGAGCA GCTGGTTTCT-3′ and 5′-CCATTCCTGAAGCAAGGAAA-3′). These products were used in standard curves ranging from 1.0 × 101 to 1.0 × 105 copies per reaction. A TAMRA-FAM labeled internal probe for the Cα region of the TCR-α gene locus was used for detection of Cα copy number [17]. sjTREC values for samples were calculated using ABI 7700 software and samples were analyzed in triplicate experiments excluding results varying by about 10%. Results were averaged. Data are expressed as the number of TRECs per DNA equivalent in 105 input cells.

2.7. T cell suppression assays

T cell suppression assays were preformed as in [18]. Specifically, in round-bottom 96-well microtiter plates, effector CD4+CD25− T cells (3.7 × 103/well) were incubated in either a 1:1 or 4:1 ratio with CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells and magnetic beads (StemCell Technologies). Control conditions lacked either CD4+CD25+ or CD4+CD25– T cells. T cells were cultured for 7 days at 37 °C in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. In the last 16 h of the incubation, [3H]-thymidine (1.0 μCi/well) was added, and cellular incorporation was determined by liquid scintillation counting using a Perkin Elmer scintillation counter.

2.8. Statistical analyses

Paired t tests or ANOVAs were used for analysis of significance. Analysis was carried out with GraphPad Prism statistical software (GraphPad Software, Inc.). P values ≤0.05 were considered significant and are indicated on the figures accompanying this article.

3. Results

3.1. siRNA-induced inhibition of STAT5A/B and subsequent reduction in FOXP3, IL-2R, Bcl-X and IGF1 mRNA

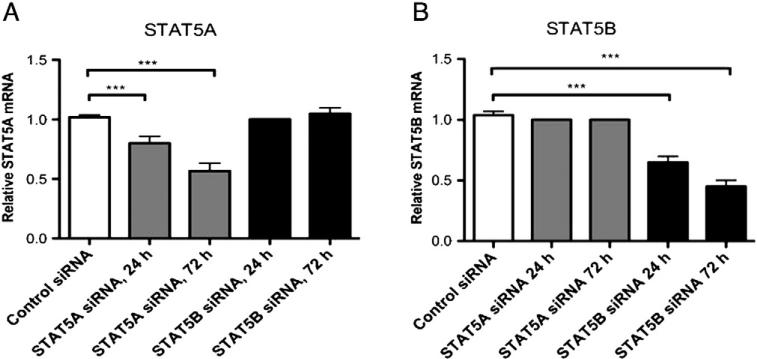

To determine the distinct effect of STAT5A vs. STAT5B, we initially transfected primary human CD4+ T cells with siRNA specific to STAT5A, STAT5B, or a scrambled control, and quantified STAT5A and STAT5B mRNAs in these unstimulated T cells. When compared with control siRNA-transfected T cells, STAT5A siRNA-transfected CD4+ T cells showed a 33% and 45% reduction in STAT5A gene expression after 24 h and 72 h, respectively (Fig. 1A, P < 0.001). Similarly, we observed a 40% and 58% reduction in STAT5B mRNA in STAT5B siRNA-transfected CD4+ T cells 24 and 72 h after transfection, respectively (Fig. 1B, P < 0.001). Protein analysis of transfected CD4+ T cell lysates confirmed the efficiency of the specific gene knockdowns at the corresponding protein level (Fig. S1). Interestingly, at 72 h after siRNA silencing for STAT5A, there was reappearance of small amounts of STAT5A. However, this protein expression was still significantly less compared to the sham control.

Figure 1.

Efficient knockdown of STAT5A and STAT5B in human primary CD4+ T cells. STAT5A and STAT5B were silenced in vitro using siRNA. Purified CD4+ T cells from healthy subjects (n = 3) were transfected with STAT5A siRNA (gray bars), STAT5B siRNA (black bars), or control siRNA (white bar). Relative mRNA expression of (A) STAT5A or (B) STAT5B was assessed by QT-PCR at 24 and 72 h post transfection and calculated on fold-change values over those of β-glucuronidase. ***P < 0.001, data represent mean ± SEM.

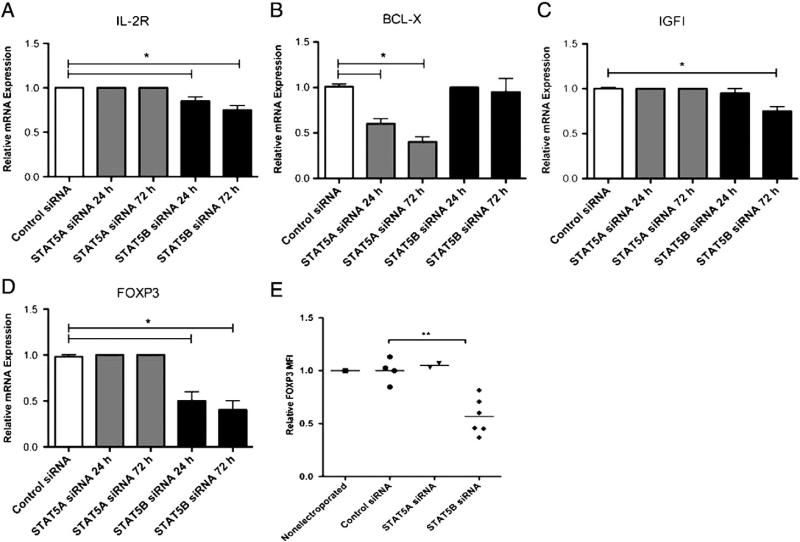

On transfected STAT5Alow or STAT5Blow CD4+ T cells, we then tested the expression of IL-2R, BCL-X, and IGF1 genes that have been reported as regulated by STAT5 proteins [19–21]. As assessed by RT-PCR and compared to control siRNA-transfected cells, knockdown of STAT5B reduced IL-2R expression by 15% after 24 h and 25% after 72 h (P < 0.001) and reduced IGF1 expression by 25% after 72 h (P < 0.001, Figs. 2 A and C), while it did not interfere with BCL-X expression at both time points. On the contrary, silencing of STAT5A significantly reduced BCL-X expression by 41% after 24 h and 61% after 72 h (P < 0.001, Fig. 2B). Therefore, STAT5B appeared to influence transcription of IL-2R whose high level is very important for Treg cell function, whereas activation of the anti-apoptotic protein BCL-X was rather STAT5A-mediated.

Figure 2.

STAT5A and STAT5B differentially regulate T cell mRNA. (A–D) Human primary CD4+ T cells from healthy subjects were transfected in triplicate and assessed by QT-PCR at 24 or 72 h post transfection with STAT5A siRNA (gray bars), STAT5B siRNA (black bars), or control siRNA (white bars) for mRNA expression of (A) IL-2R, (B) BCL-X, (C) IGF1 and (D) FOXP3. Relative mRNA expression was calculated on fold-change values over those of β-glucuronidase. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, *P < 0.001. (E) FOXP3 protein expression in CD4+ T cells was assessed by flow cytometry at 72 h post transfection with control siRNA (n = 4), STAT5A siRNA (n = 2) or STAT5B siRNA (n = 6) and graphed as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI). Levels of FOXP3 from non-electroporated T cells are shown as a control. **P < 0.005.

Both Stat5A and Stat5B have been implicated in stimulating transcription of Foxp3 in murine CD4+ T cells [22]. We found that knockdown of STAT5B in CD4+ T cells reduced FOXP3 mRNA expression by 50% after 24 h and by 75% after 72 h (Fig. 2D). Transfection with control siRNA or STAT5A siRNA did not change the level of FOXP3 transcript neither at 24 nor at 72 h post-transfection. Similarly, the relative median fluorescent intensity (MFI) of FOXP3 protein expressed in gated CD4+CD25+ cells was significantly reduced by 43% in STAT5B siRNA-transfected cells (P < 0.005, Fig. 2E) when compared to control siRNA-transfected cells or STAT5A siRNA-transfected T cells. Overall, siRNA knockdown experiments demonstrate differential regulation of target genes by STAT5A (BCL-X) versus STAT5B (FOXP3, IGF1, and IL-2R).

3.2. Reduced FOXP3 expression in Treg from STAT5B−/− patients is associated with decreased Treg function

We have previously observed a reduced number of Treg with low FOXP3 expression and suppressive function in one STAT5Bnull patient (patient #1) [11]. To determine the consistency of the effect of STAT5B on Treg development and function, we assessed Treg populations in six patients with different mutations and impairment of the STAT5B protein expression, but with normal STAT5A expression. Demographics and immune phenotype of the patients are outlined in Table 1. STAT5Bnull/low patients varied in NK cell, CD8 T cell and CD4 T cell absolute counts and overall lymphopenia was seen in many of the patients (Table 1). The percent of CD4+CD25hi Treg within the T cells was reduced in five out of six of the STAT5B mutated patients (1% compared to 2–6% in healthy individuals) whereas it was normal in patient #6 who had detectable but low levels of STAT5B transcript expression, as compared to age matched healthy controls (Fig. S3). The absence of STAT5B protein expression in the STAT5Bnull patients was confirmed using a NanoPro Immunoassay (Fig. S2). Additionally, PBMCs from the 6 STAT5Bmutated patients had normal STAT5A expression (Table 1). Additionally, Treg function was tested with CD4+CD25+CD127low T cells purified by FACS sorting (for gating strategy, see Fig. S4A). Treg function in patients varied from 13% to 72% of normal Treg function. Of note, patient #5 (STAT5Bnull) and #6 (STAT5Blow) had the highest percent of Treg function (72 and 77% of normal, respectively) and Treg numbers (3 and 6%, within normal range) and had no clinical signs of immune dysfunction (Table 1).

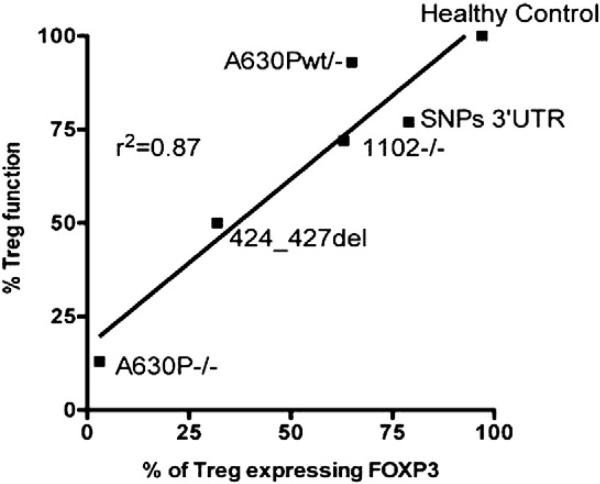

A linear regression analysis between Treg function (expressed as percentage of suppression of proliferation of CD4+ T cells) and percentage of Treg expressing FOXP3 from STAT5B−/− patients #1, 2, 5 and 6, a patient heterozygous for STAT5B, and 1 healthy control (r2 value of 0.87) was performed. These data indicate that Treg from STAT5B−/− patients have reduced FOXP3 expression that directly correlates with decreased Treg suppressive function (Fig. 3). In addition to the immunological defects STAT5B-deficient patients all showed severe growth failure. Patient #1 showed a severe chronic pulmonary fibrosis [15]. Patient #5 had, except for a history of hemorrhagic varicella after immigration to the Netherlands, no clinical signs of immune dysfunction [23]. Patients #3 and #4 were siblings and along with patient #1 and #2 have chronic pulmonary disease [14].

Figure 3.

Reduced Treg FOXP3 expression in STAT5B-deficient patients correlates to reduced Treg function. Treg were purified from 4 subjects with STAT5B mutations, 1 heterozygote patients (A630Pwt/−) and 6 healthy controls. CD4+CD25hi Treg were assessed for FOXP3 expression via flow cytometry and suppressive capability was assayed by [3H]-thymidine incorporation, in which cells were cultured in a 1:1 ratio of CD4+ effector T cells to Treg. Data were recorded as mean cpm, and representative data are reported as fold differences compared with unstimulated healthy control. Linear regression analysis was preformed comparing % of Treg expressing FOXP3 and % Treg suppressive function (r2 = 0.87).

3.3. FOXP3+ Treg cells from STAT5B-deficient patients are of the memory subset

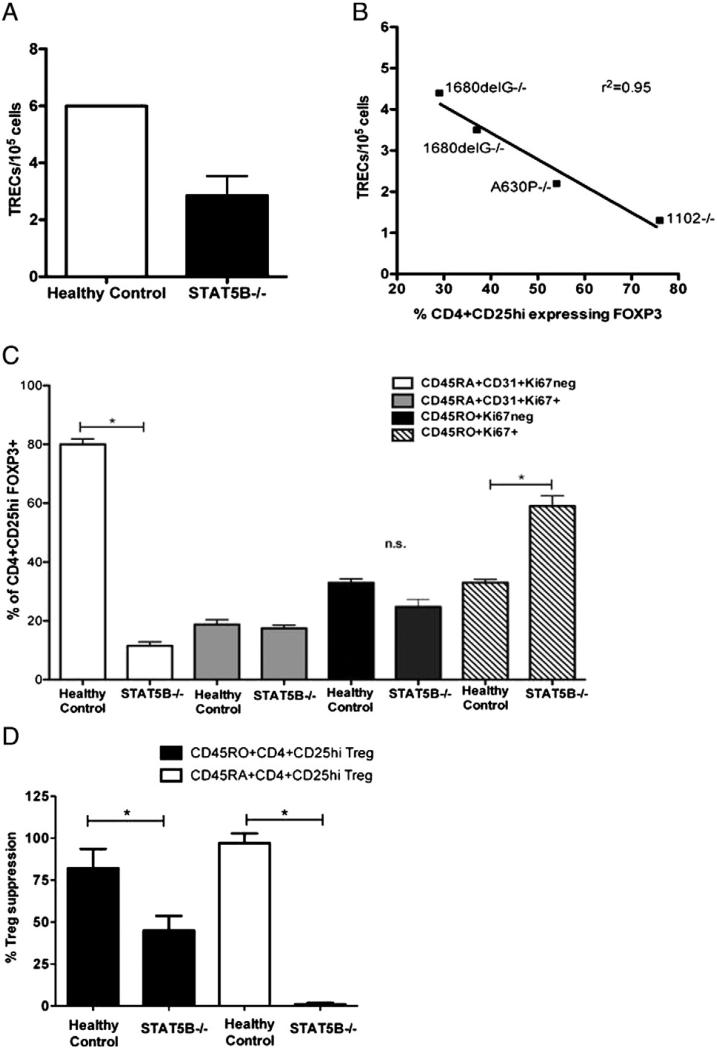

Previous studies have positively correlated FOXP3 expression with de novo T cell development, as revealed by the assessment of excision circles in the TCR gene rearrangement (TRECs) [24]. Additionally, TRECs have been used as a possible measurement of recent thymic emigration (RTE) [13]. We anticipated that reduced FOXP3 expression in Treg of STAT5B-deficient patients could be due to reduced thymic output and would correlate with reduced TREC measurements. Purified CD4+CD25+ T cells (for gating strategy, see Fig. S4B) from 4 of the STAT5B−/− subjects [1–4] or age-matched healthy controls were assessed for FOXP3 expression by flow cytometry and single joint T cell receptor rearrangement excision circle (sjTREC). CD4+CD25+ Treg from STAT5B−/− subjects had consistent lower levels of sjTRECs (mean 2.5, sjTRECs per 105 cells) as compared with CD4+CD25+ Treg from healthy controls (mean 6, sjTRECs per 105 cells, P ≤0.03) (Fig. 4A). When compared to the level of FOXP3 expression, the numbers of sjTRECs in CD4+CD25+ T cells from STAT5B−/− subjects inversely correlated with the level of FOXP3 expression. (Fig. 4B, r2 = 0.95). Previous studies have demonstrated that TREC measurements in the periphery can be a marker of thymic output (if high), with limitations, or indicate that peripheral T cells have undergone division (if low) (reviewed in [25]). Therefore, these data could imply that CD4+CD25+ T cells expressing FOXP3 in STAT5B−/− subjects are likely not recent thymic emigrants and may be of a memory Treg subset.

Figure 4.

Memory Treg with low sjTREC account for FOXP3+ Treg in STAT5B-deficient patients. A) Purified CD4+CD25hi Treg from age-matched healthy control (n = 3) and STAT5B−/− patients (n = 4, patients #1–4) were assessed for sjTREC. B) Linear regression analysis was preformed comparing the number of TRECs/105 cells and FOXP3 expression (as assessed by flow cytometry) in CD4+CD25hi Treg from 4 STAT5B−/− patients. C) Phenotypes of CD4+CD25hi Treg from PBMCs from age-matched healthy controls (n = 6) or STAT5B−/− patients were identified by flow cytometry for CD45RA+CD31+ Ki67neg (white bars), CD45RA+CD31+ Ki67+ (gray bars), CD45RO+Ki67neg (black) and CD45RO+Ki67+ (dashed) Treg. D) Suppressive function of naïve or memory Treg from STAT5B-deficient patients or healthy control subjects age-matched (n = 6) was assessed. CD3-depleted irradiated antigen presenting cells were incubated with purified Treg (CD4+CD25hiCD45RO+, black bars) or CD4+CD25hiCD45RA+, white bars) and were incubated with autologous CD4+CD25low effector T cells. Proliferation was measured by [3H]-thymidine incorporation during the last 18 h of a 5-day culture. Cell proliferation is expressed as mean cpm ± SEM for triplicate wells from two separate experiments. Data is shown as mean ±SEM, *P < 0.05, n.s.; not significant.

To better define the Treg populations present in STAT5B−/− patients and confirm their memory phenotype, CD4+CD25hi FOXP3+ T cells were further phenotyped into memory (CD45RO+) or naïve (CD45RA+CD31+) and dividing/non-dividing (Ki67+/Ki67neg) [26] by flow cytometry. As shown in Fig. 4C, dividing, memory Treg preferentially expressed FOXP3 as compared to other subsets of Treg analyzed in the STAT5B−/− subjects. This is in contrast to the age-matched controls in which the majority of CD4+CD25hi FOXP3+ Treg were made up of naïve, non-dividing (CD45RA + CD31+ Ki67neg subset) cells. Therefore, the majority of FOXP3-expressing Treg from STAT5B−/− subjects are dividing, memory Treg. Finally, we determined if the Treg dysfunction observed in STAT5B−/− patients was restricted to particular Treg populations. Treg function of memory and naïve Treg subsets from STAT5B−/− and healthy subjects were assessed by standard suppression assays. The data in Fig. 4D show that both memory and naïve Treg subsets from STAT5B−/− patients had reduced suppressive capabilities as compared to controls, with naïve STAT5B−/− Treg demonstrating the lowest Treg function (P < 0.05). These data indicate that in the absence of STAT5B expression, in addition to impairment of Treg suppressive function, there is less Treg thymic output and at the same time Treg are more prone to switch to a memory phenotype. Whether these memory Treg are truly thymic derived Treg or are adaptive Treg peripherally induced remains to be clarified.

4. Discussion

Previous mouse knock-out studies demonstrated that Stat5A and Stat5B are collectively essential regulators of lymphoid development and peripheral tolerance with both redundant and non-redundant roles [6]. In humans, the identification of STAT5B mutations associated with the complex clinical syndromes of growth hormone insensitivity and immune deficiency revealed that STAT5B and STAT5A have certain distinct and non-redundant roles, despite sharing >90% identity at the amino acid residue level.

In the present study, we provide evidence in human primary T cells for a distinctive role of STAT5B and STAT5A in immune function, showing that STAT5B, but not STAT5A, regulated the expression of FOXP3 and IL-2R, and that STAT5A, but not STAT5B, regulated the transcription of the pro-apoptotic factor BCL-X. We further demonstrate that in the absence of STAT5B, despite normal expression of STAT5A, Treg cell number and function are impaired, as consistently observed in STAT5B-deficient patients, independently from the mutations. In addition, we report that peripheral naïve STAT5B-deficient Treg cells in these patients are particularly decreased and have low TREC, whereas the memory STAT5B-deficient Treg predominate and have increased proliferative potential in vivo compared to age matched controls. These results not only confirm our previous preliminary observation of Treg insufficiency in STAT5B-deficient patients [11], but also highlight the critical importance of STAT5B for Treg development and maintenance. This suggests that STAT5B, not STAT5A, can directly interact with FOXP3, therefore influencing Treg development and/or function. Further studies are necessary to confirm this.

Notably, we also show that reduced FOXP3 expression in Treg, detected in 4 additional STAT5B−/− patients, correlated with the level of impairment of suppressive function. We observed that patients with more preserved FOXP3 expression and Treg function did not have autoimmune manifestations, proving the causative effect of the Treg deficiency in the development of autoimmunity, as observed in patients with FOXP3 mutations [27].

Previous mouse studies and our current cell culture studies demonstrate the role for STAT5B in regulating FOXP3 expression and to a lesser extent IL-2R expression. Thus, these results imply that STAT5B regulates Treg function through regulation of FOXP3 and possibly IL-2R. Since IL-2R signaling plays an important role in Treg survival and differentiation, the decrease in IL-2R expression in STAT5B knockdown T cells may be indicative of decreased responsiveness to IL-2 and subsequent reduced proliferation/maintenance and FOXP3 expression. High FOXP3 expression is due to strong IL-2-IL-2R-STAT5 signaling.

However, it is also possible that the reduced expression of these two molecules that are essential for Treg development and maintenance in vivo, affects Treg cell generation and/ or alters their ability to remain “fitted” in the peripheral environment. The demonstration of reduced naïve Treg cells and higher memory Treg cells could sustain this hypothesis. Conversely, studies have shown that even in the absence of optimal IL-2R signaling, Treg thymic development and peripheral homeostasis effectively occurs (reviewed [28]).

Alternatively, the reduced FOXP3 naïve and increased memory FOXP3 phenotype could be associated with conventional T cell activity rather than suppressor Treg [29,30]. The markers we used for Treg selection, including FOXP3hiCD127lowCD25hi, are considered standard and sufficient to identify nTreg cells and to distinguish them from T conventional cells, including activated T cells and induced Treg. However, further characterization of the induced Treg compartment and of the state of activation of T effector cells in these patients, could clarify the reason for the low naïve/high memory FOXP3+ T cells.

Indeed, human CD4+CD25hi Treg do not arise solely from thymic generation but can also be induced by rapid turnover from the memory T cell pool [31]. We determined that a dividing memory Treg subset (CD45RO+Ki67+) expressed FOXP3 preferentially over other subsets of Treg in STAT5B−/− patients, sharply contrasting with age-matched controls in which a naïve, non-dividing subset was the most enriched in FOXP3 expression (Fig. 4). These data show that the majority of Treg from STAT5B−/− subjects are dividing, memory Treg that may be compensating for a lack of de novo FOXP3+ Treg production. It could also be hypothesized that FOXP3 expression in Treg from STAT5B−/− patients is regulated via STAT5B-independent and STAT5A-independent pathways. This hypothesis is further supported by the difference in Treg cell number and function in STAT5B−/− patients with different STAT5B mutations. For example, patient #5 (1102−/−) has relatively normal Treg number (3% of normal) and cell function (72% of normal) that we found to be associated with FOXP3 expression and reduced TREC; this is compared to patient #1 (A630P−/−), whom has sub-normal Treg number (1% of normal) and function (13% of normal) with reduced FOXP3 and increased TREC (Table 1, Figs. 3 and 4). All of the STAT5B mutations in the STAT5B−/− patients reported herein are null mutations, thus our data suggests that there is a compensatory pathway, independent of STAT5, which is regulating FOXP3 expression and Treg development.

We believe that the high proportion of memory Treg in STAT5B−/− patients may have contributed to their auto-immune disease severity. Previous work has shown that memory Treg have reduced suppressive functionality, as indicated by their very high turnover in vivo, high susceptibility to apoptosis, and critically short telomeres [13]. Consistent with these findings, we observed that all Treg subsets from STAT5B−/− patients had reduced suppressive capabilities as compared to controls, and that naïve Treg had the lowest levels of Treg function. Finally, a recent study demonstrates a role for STAT5 in negative regulation of follicular helper T cell differentiation [32] via Blimp-1 and it would be of interest to study this population of immune cells in the STAT5B−/− patients along with the effects of siRNA studies in STAT5A vs. STAT5B in Blimp-1-mediated functions.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, our data demonstrate that despite being highly homologous proteins, some functions of STAT5A and STAT5B are non-redundant. Further ChIP-Seq studies more widely delineating the regulation and differential roles of STAT5A vs. STAT5B in human T cells will increase our understanding of the mechanism(s) of human immune dysregulation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Maarten J.D. van Tol, Leiden University Medical Center, for help with the culture of lymphocytes. Writing and editing assistance was provided by Amanda C. Jacobson, Ph.D., Stanford University. This work was supported by the Clinical Immunological Society Junior Faculty Award.

Abbreviations

- Treg

regulatory T cell

- FOXP3

forkhead box P3

- TREC

T cell receptor excision circles

Footnotes

6. Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.clim.2013.04.014.

References

- 1.Soldaini E, John S, Moro S, Bollenbacher J, Schindler U, Leonard WJ. DNA binding site selection of dimeric and tetrameric Stat5 proteins reveals a large repertoire of divergent tetrameric Stat5a binding sites. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000;20:389–401. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.1.389-401.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boucheron C, Dumon S, Santos SC, Moriggl R, Hennighausen L, Gisselbrecht S, Gouilleux F. A single amino acid in the DNA binding regions of STAT5A and STAT5B confers distinct DNA binding specificities. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:33936–33941. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.51.33936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grimley PM, Dong F, Rui H. Stat5a and Stat5b: fraternal twins of signal transduction and transcriptional activation. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 1999;10:131–157. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(99)00011-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Snow JW, Abraham N, Ma MC, Herndier BG, Pastuszak AW, Goldsmith MA. Loss of tolerance and autoimmunity affecting multiple organs in STAT5A/5B-deficient mice. J. Immunol. 2003;171:5042–5050. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.10.5042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Teglund S, McKay C, Schuetz E, van Deursen JM, Stravopodis D, Wang D, Brown M, Bodner S, Grosveld G, Ihle JN. Stat5a and Stat5b proteins have essential and nonessential, or redundant, roles in cytokine responses. Cell. 1998;93:841–850. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81444-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yao Z, Cui Y, Watford WT, Bream JH, Yamaoka K, Hissong BD, Li D, Durum SK, Jiang Q, Bhandoola A, Hennighausen L, O'Shea JJ. Stat5a/b are essential for normal lymphoid development and differentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:1000–1005. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507350103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yao Z, Kanno Y, Kerenyi M, Stephens G, Durant L, Watford WT, Laurence A, Robinson GW, Shevach EM, Moriggl R, Hennighausen L, Wu C, O'Shea JJ. Nonredundant roles for Stat5a/b in directly regulating Foxp3. Blood. 2007;109:4368–4375. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-11-055756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nadeau K, Hwa V, Rosenfeld RG. STAT5b deficiency: an unsuspected cause of growth failure, immunodeficiency, and severe pulmonary disease. J. Pediatr. 2011;158:701–708. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Torgerson TR. Immune dysregulation in primary immuno-deficiency disorders. Immunol. Allergy Clin. N. Am. 2008;28:315–327. viii–ix. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zorn E, Nelson EA, Mohseni M, Porcheray F, Kim H, Litsa D, Bellucci R, Raderschall E, Canning C, Soiffer RJ, Frank DA, Ritz J. IL-2 regulates FOXP3 expression in human CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells through a STAT-dependent mechanism and induces the expansion of these cells in vivo. Blood. 2006;108:1571–1579. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-004747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen AC, Nadeau KC, Tu W, Hwa V, Dionis K, Bezrodnik L, Teper A, Gaillard M, Heinrich J, Krensky AM, Rosenfeld RG, Lewis DB. Cutting edge: decreased accumulation and regulatory function of CD4+CD25(high) T cells in human STAT5b deficiency. J. Immunol. 2006;177:2770–2774. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.5.2770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fontenot JD, Gavin MA, Rudensky AY. Foxp3 programs the development and function of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. Nat. Immunol. 2003;4:330–336. doi: 10.1038/ni904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vukmanovic-Stejic M, Zhang Y, Cook JE, Fletcher JM, McQuaid A, Masters JE, Rustin MH, Taams LS, Beverley PC, Macallan DC, Akbar AN. Human CD4+ CD25hi Foxp3+ regulatory T cells are derived by rapid turnover of memory populations in vivo. J. Clin. Invest. 2006;116:2423–2433. doi: 10.1172/JCI28941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hwa V, Nadeau K, Wit JM, Rosenfeld RG. STAT5b deficiency: lessons from STAT5b gene mutations. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011;25:61–75. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kofoed EM, Hwa V, Little B, Woods KA, Buckway CK, Tsubaki J, Pratt KL, Bezrodnik L, Jasper H, Tepper A, Heinrich JJ, Rosenfeld RG. Growth hormone insensitivity associated with a STAT5b mutation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;349:1139–1147. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu GP, Chiang D, Song SJ, Hoyte EG, Huang J, Vanishsarn C, Nadeau KC. Regulatory T cell dysfunction in subjects with common variable immunodeficiency complicated by autoimmune disease. Clin. Immunol. 2009;131:240–253. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haines CJ, Giffon TD, Lu LS, Lu X, Tessier-Lavigne M, Ross DT, Lewis DB. Human CD4+ T cell recent thymic emigrants are identified by protein tyrosine kinase 7 and have reduced immune function. J. Exp. Med. 2009;206:275–285. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nadeau K, McDonald-Hyman C, Pratt B, Noth B, Hammond K, Balmes J, Tager I. Ambient air pollution impairs regulatory T-cell function in asthma. J. Allergy. Clin. Immunol. 2010;126:845–852. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Antov A, Yang L, Vig M, Baltimore D, Van Parijs L. Essential role for STAT5 signaling in CD25+CD4+ regulatory T cell home-ostasis and the maintenance of self-tolerance. J. Immunol. 2003;171:3435–3441. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.7.3435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gesbert F, Griffin JD. Bcr/Abl activates transcription of the Bcl-X gene through STAT5. Blood. 2000;96:2269–2276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joung YH, Lee MY, Lim EJ, Kim MS, Hwang TS, Kim SY, Ye SK, Lee JD, Park T, Woo YS, Chung IM, Yang YM. Hypoxia activates the IGF-1 expression through STAT5b in human HepG2 cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007;358:733–738. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.04.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Passerini L, Allan SE, Battaglia M, Di Nunzio S, Alstad AN, Levings MK, Roncarolo MG, Bacchetta R. STAT5-signaling cytokines regulate the expression of FOXP3 in CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells and CD4+CD25-effector T cells. Int. Immunol. 2008;20:421–431. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxn002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walenkamp MJ, Vidarsdottir S, Pereira AM, Karperien M, van Doorn J, van Duyvenvoorde HA, Breuning MH, Roelfsema F, Kruithof MF, van Dissel J, Janssen R, Wit JM, Romijn JA. Growth hormone secretion and immunological function of a male patient with a homozygous STAT5b mutation. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2007;156:155–165. doi: 10.1530/eje.1.02327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miura Y, Thoburn CJ, Bright EC, Phelps ML, Shin T, Matsui EC, Matsui WH, Arai S, Fuchs EJ, Vogelsang GB, Jones RJ, Hess AD. Association of Foxp3 regulatory gene expression with graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2004;104:2187–2193. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hazenberg MD, Otto SA, Cohen Stuart JW, Verschuren MC, Borleffs JC, Boucher CA, Coutinho RA, Lange JM, Rinke de Wit TF, Tsegaye A, van Dongen JJ, Hamann D, de Boer RJ, Miedema F. Increased cell division but not thymic dysfunction rapidly affects the T-cell receptor excision circle content of the naive T cell population in HIV-1 infection. Nat. Med. 2000;6:1036–1042. doi: 10.1038/79549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Booth NJ, McQuaid AJ, Sobande T, Kissane S, Agius E, Jackson SE, Salmon M, Falciani F, Yong K, Rustin MH, Akbar AN, Vukmanovic-Stejic M. Different proliferative potential and migratory characteristics of human CD4+ regulatory T cells that express either CD45RA or CD45RO. J. Immunol. 2010;184:4317–4326. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kanai T, Jenks J, Nadeau KC. The STAT5b pathway defect and autoimmunity. Front. Immunol. 2012;3:234. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheng G, Yu A, Malek TR. T-cell tolerance and the multi-functional role of IL-2R signaling in T-regulatory cells. Immunol. Rev. 2011;241:63–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01004.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tran DQ, Ramsey H, Shevach EM. Induction of FOXP3 expression in naive human CD4+ FOXP3 T cells by T-cell receptor stimulation is transforming growth factor-beta dependent but does not confer a regulatory phenotype. Blood. 2007;110:2983–2990. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-094656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang J, Ioan-Facsinay A, van der Voort EI, Huizinga TW, Toes RE. Transient expression of FOXP3 in human activated nonregulatory CD4+ T cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 2007;37:129–138. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huehn J, Polansky JK, Hamann A. Epigenetic control of FOXP3 expression: the key to a stable regulatory T-cell lineage? Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2009;9:83–89. doi: 10.1038/nri2474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnston RJ, Choi YS, Diamond JA, Yang JA, Crotty S. STAT5 is a potent negative regulator of TFH cell differentiation. J. Exp. Med. 2012;209:243–250. doi: 10.1084/jem.20111174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.