Abstract

Proliferative kidney disease (PKD) is a widespread disease of farmed and wild salmonid populations in Europe and North America, caused by the myxozoan parasite Tetracapsuloides bryosalmonae. Limited studies have been performed on the epidemiological role in spread of the disease played by fish that survive infection with T. bryosalmonae. The aim of the present study was to evaluate the persistence of T. bryosalmonae developmental stages in chronically infected brown trout Salmo trutta up to 2 yr after initial exposure to laboratory-infected colonies of the parasite’s alternate host, the bryozoan Fredericella sultana. Kidney, liver, spleen, intestine, brain, gills and blood were sampled 24, 52, 78 and 104 wk post-exposure (wpe) and tested for T. bryosalmonae by PCR and immunohistochemistry (IHC). Cohabitation trials with specific pathogen free (SPF) F. sultana colonies were conducted to test the viability of T. bryosalmonae. PCR detected T. bryosalmonae DNA in all tissue samples collected at the 4 time points. Developmental stages of T. bryosalmonae were demonstrated by IHC in most samples at the 4 time points. Cohabitation of SPF F. sultana with chronically infected brown trout resulted in successful transmission of T. bryosalmonae to the bryozoan. This study verified the persistence of T. bryosalmonae in chronically infected brown trout and their ability to infect the bryozoan F. sultana up to 104 wpe.

Keywords: Salmonid, Fredericella sultana, Proliferative kidney disease, Developmental stages, chronic infection

INTRODUCTION

Proliferative kidney disease (PKD) is an economically important disease affecting salmonid industries in Europe and North America (El-Matbouli et al. 1992, Hedrick et al. 1993). The disease is characterized by nephromegaly, splenomegaly, glomerulonephritis, ascites, exophthalmia, pale gills and darkened skin. PKD severity as well as fish host recovery is dependent on water temperature (Foott & Hedrick 1987, El-Matbouli & Hoffmann 2002, Okamura et al. 2011).

PKD is caused by Tetracapsuloides bryosalmonae (Anderson et al. 1999, Canning et al. 1999, Feist et al. 2001), which belongs to the phylum Myxozoa, class Malacosporea. The T. bryosalmonae life cycle alternates between an invertebrate host (freshwater bryozoans; Canning et al. 1999, 2002) and a vertebrate host, salmonid fish. Overtly infected bryozoans re lease the parasite into the water, and fish are infected through gills (Feist et al. 2001, Grabner & El-Matbouli 2010). Kidney, liver and spleen of the fish host can be affected, but the kidney is the main target organ. In the kidney, T. bryosalmonae undergoes multiplication and differentiation from extra- or pre-sporogonic stages to intra-luminal sporogonic stages (Kent & Hedrick 1986), and infected fish release the spores through the urine (Hedrick et al. 2004).

Although many salmonid species are susceptible to T. bryosalmonae, only a few (e.g. brown trout Salmo trutta, infected with the European strain) can excrete the parasite spores to infect the bryozoans and complete the life cycle (Morris & Adams 2006, Grabner & El-Matbouli 2008). In contrast, rainbow trout Oncorhynchus mykiss do not transmit the infection to the bryozoans (Grabner & El-Matbouli 2008). Rainbow trout held at lower temperatures obtain resistance to the parasite; similarly, rainbow trout that survive a PKD outbreak acquire immunity against the disease in the following season (Foott & Hedrick 1987, de Kinkelin & Loriot 2001).

Infection with T. bryosalmonae seems to play a significant role in declines of wild salmonid populations: e.g. brown trout in Switzerland, and wild Atlantic salmon Salmo salar in the River Åelva in Central Norway (Wahli et al. 2002, Sterud et al. 2007). The endogenic development of T. bryosalmonae in rainbow trout has been well documented (Bettge et al. 2009, Schmidt-Posthaus et al. 2012). In contrast, few reports are available on the chronological development of T. bryosalmonae in brown trout (Clifton-Hadley & Feist 1989, Morris & Adams 2008, Grabner & El-Matbouli 2009, Kumar et al. 2013a, Schmidt-Posthaus et al. 2013). Only limited chronological studies on the effect of PKD on wild salmonid populations have been conducted (Feist et al. 2002, Wahli et al. 2007) due to difficulties adapting sampling protocols, presence of predators and or misdiagnosis resulting from secondary infections (Okamura et al. 2011). Laboratory investigations are easier to conduct, and in this study we aimed to investigate the persistence and infectivity of T. bryosalmonae in chronically infected brown trout at 24, 52, 78 and 104 wk post-exposure (wpe) and the ability of these fish to release viable spores infective for specific pathogen free (SPF) F. sultana colonies, under controlled laboratory condition.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fish

Two groups each of 25 SPF brown trout were obtained as eyed eggs from a local hatchery. Each group was maintained separately in 50 l aquaria at 15°C (±1°C) with flow-through dechlorinated tap water, and fed with commercial fish pellets. Prior to the experiment, brown trout stock were sampled randomly and tested by PCR to confirm absence of any myxozoan infections.

Exposure of SPF brown trout to infected Fredericella sultana colonies

SPF brown trout (n = 20; mean ± SD length 5.4 ± 0.5 cm, weight 2.6 ± 0.5 g) were cohabitated for 2 d with overtly infected F. sultana colonies from our laboratory (8 zooids comprising 36 mature Tetracapsuloides bryosalmonae spore sacs; infection was verified by stereo microscopy). A control group of fish (n = 20) was cohabitated for 2 d with SPF F. sultana colonies from our laboratory stock (SPF status was confirmed based on PCR results and daily observation of colonies under a stereomicroscope). During the cohabitation trial, aquarium water flow-through was closed and bryozoan colonies were fed with 6 algae species (80% Cryptomonas ovata; 20% a mixture of Cryptomonas spp., Chlamydomonas spp., Chlamydomonas reinhardii, and Synechococcus spp., Synechococcus leopoliensis) cultured in sterile Guillard’s WC-Medium according to Abd-Elfattah et al. (2014). Feed was added 3 times a week and the water changed every week.

Cohabitation of SPF F. sultana colonies with chronically infected brown trout

SPF F. sultana bryozoans raised in our laboratory were cohabitated with the infected brown trout at 24, 52, 78 and 104 wpe according to Kumar et al. (2013b). Briefly, 2 mo old F. sultana colonies were cohabitated for 8 h daily for 14 d with the chronically infected brown trout in a 50 l aquarium filled with aerated dechlorinated tap water at 15°C (±1°C). During the cohabitation, fish and F. sultana colonies were maintained as described above. Colonies of F. sultana were examined twice a week under a stereomicroscope for the development of T. bryosalmonae. After detection of parasite sacs in the cohabitated colonies, samples of infected zooids were sampled for PCR confirmation of infection with T. bryosalmonae using the methods of Grabner & El-Matbouli (2009).

Blood collection and organ sampling from infected brown trout

To verify the infection, 2 fish from each group were dissected 8 wpe and the kidney was sampled for PCR assay (Grabner & El-Matbouli 2009). All fish were checked daily for mortality or unusual behavior.

At 24, 52, 78 and 104 wpe, 3 fish from the test group were selected randomly, anaesthetized with MS-222 (Tricaine methanesulphonate; Sigma-Aldrich), and blood sampled directly from the heart into hepa rinized tubes (SARSTEDT). Control group fish were also selected randomly and blood samples taken at the same time points (4 fish each at 24 and 52 wpe, and 5 fish each at 78 and 104 wpe). Fish were then killed with an overdose of MS-222. Skin and gills were checked for external parasites and the appearance of the inner organs was assessed. Kidney, liver, spleen, intestine, brain and gills were sampled and preserved at −80°C until used for DNA extraction. Part of each organ was fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for immunohistochemistry (IHC).

Genomic DNA extraction and PCR

DNA was extracted from blood using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (QIAGEN) according to manufacturer’s instructions. All tissue samples collected from different time points from infected and control fish and infected zooids with mature sacs of T. bryosalmonae were homogenized separately using a Tissue Lyser (QIAGEN), and genomic DNA was ex trac ted with a QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA concentration was measured with a Bio-Photometer (Eppendorf). PCR for the detection of T. bryosalmonae used primers 5F (5′-CCT ATT CAA TTG AGT AGG AGA-3′) and 6R (5′-GGA CCT TAC TCG TTT CCG ACC-3′) in the first round (Kent et al. 1998), followed by a nested reaction using primers PKD-real F (5′-TGT CGA TTG GAC ACT GCA TG-3′) and PKD-real R (5′-ACG TCC GCA AAC TTA CAG CT-3′) (Grabner & El-Matbouli 2009).

PCR amplifications were carried out in 25 μl reaction volume containing 12.5 μl of 2× ReddyMix PCR Master Mix (ABGene), 10 pmol of each primer, 1 μl of DNA and 9.5 μl of PCR grade water. The cycling program was initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min; followed by 35 cycles at 95°C for 1 min, 55°C for 1 min in the first-round PCR (61°C in the nested PCR), 72°C for 1 min; and a final extension step at 72°C for 5 min. The amplified PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis on 1.5% agarose gels in Tris acetate-EDTA buffer (0.04 M Tris acetate, 1 mM EDTA) stained with ethidium bromide. DNA 100 and 50 bp molecular weight ladders were used to estimate size of the PCR amplicons.

Immunohistochemistry

Samples from kidney, liver, spleen, intestine, brain and gills from infected and control fish were prepared for IHC according to Grabner & El-Matbouli (2009) with minor modifications. Briefly, fish tissues were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, washed, dehydrated and embedded in paraffin (Tissue-Tek VIP; Sakura Bayer Diagnostics). Sections were cut at 5 μm and processed for IHC assay. T. bryosalmonae-specific monoclonal antibody P01 (Aquatic Diagnostics) was used according to the manufacturer’s instruction. The antibody–antigen reaction was visualized with a Dako EnVision+ System-HRP (AEC) kit (Dako). To visualize the reaction, slides were incubated with the AEC substrate for 4 min until a pink color appeared. The reaction was stopped by immersing the slides in distilled water, then the sections were counterstained with haematoxylin, mounted and examined. Kidney tissue of known PKD infected fish was used as a positive control. Kidney from SPF control fish was considered as negative control.

RESULTS

Fish infection

Among fish exposed to the infected bryozoan Fredericella sultana, no mortalities took place in the first 6 wpe and the fish did not show any abnormal behavior. Four fish from the infected group died in the period 6–10 wpe and 2 fish at 14 wpe, due to PKD, and all were injured (especially on the caudal fin) due to cannibalism caused by variance in growth between individuals and competition for feed.

In the treatment group, kidney samples from both routinely dissected fish at 8 wpe and all 6 mortalities tested positive by PCR for Tetracapsuloides bryosalmonae. Internal PKD symptoms including swollen kidney, pale liver and enlarged spleen were obvious in both fish dissected at 8 wpe and in the fish that died at 6–10 wpe. Only moderate exophthalmia and darkened skin were exhibited by all fish in the infected group 12–26 wpe, but these symptoms had disappeared by the end of the experiment. No other clinical signs were observed and no ectoparasites were seen on gills or skin. The 2 fish sampled from the control group at 8 wpe were PCR-negative for T. bryosalmonae.

Exposure of SPF F. sultana colonies to infected brown trout

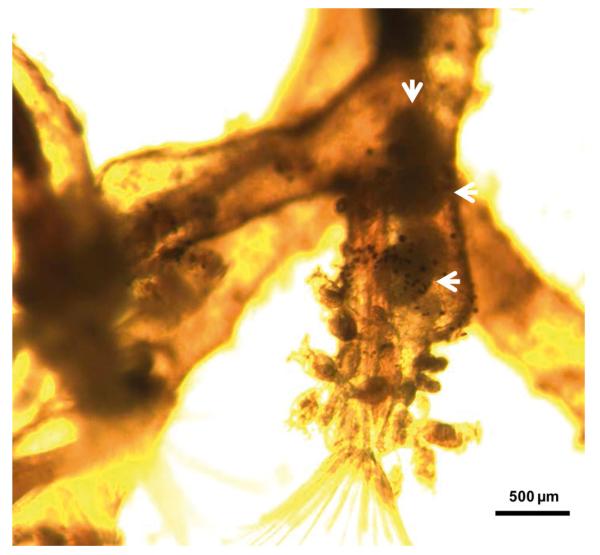

Approximately 4–5 wk after each exposure to infected brown trout (at 26, 52, 78 and 104 wpe), unattached motile overt developmental stages of T. bryosalmonae were observed in the body cavities of exposed F. sultana colonies. Over the following 4 wk, overt infections with characteristic mature sacs were seen floating in the metacoel (Fig. 1). F. sultana zooids were PCR-positive for T. bryosalmonae.

Fig. 1.

Fredericella sultana infected with Tetracapsuloides bryosalmonae, maintained at 15°C. Parasite spore sacs (arrows) are visible in the body cavity of F. sultana after cohabitation with infected brown trout at 104 wk post-exposure

PCR and IHC

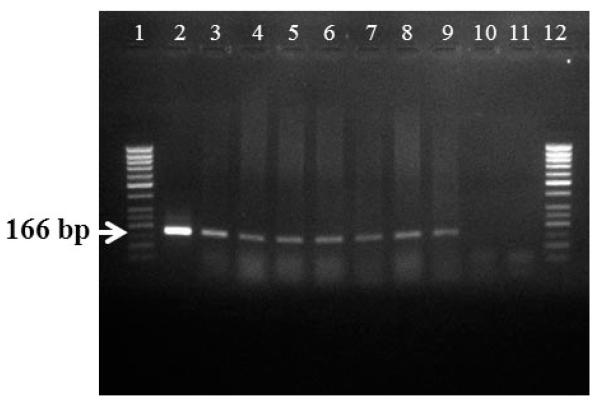

T. bryosalmonae DNA was detected by PCR from kidney, liver, spleen, intestine, brain, gills and blood at 26, 52, 78 and 104 wpe from all fish (Fig. 2). In contrast, blood and organs (kidney, liver, spleen, intestine, brain and gills) from all 20 control fish were negative by PCR.

Fig. 2.

PCR amplification of brown trout Salmo trutta tissues infected with Tetracapsuloides bryosalmonae. Data are from 1 fish’s tissues sampled at 104 wk post-exposure. Lanes 1 and 12: 50 bp DNA ladder (Fermentas); Lane 2: positive control; Lane 3: kidney; Lane 4: liver; Lane 5: spleen; Lane 6: gill; Lane 7: intestine; Lane 8: brain; Lane 9: blood; Lane 10: negative control (kidney of control fish); Lane 11: no-template control

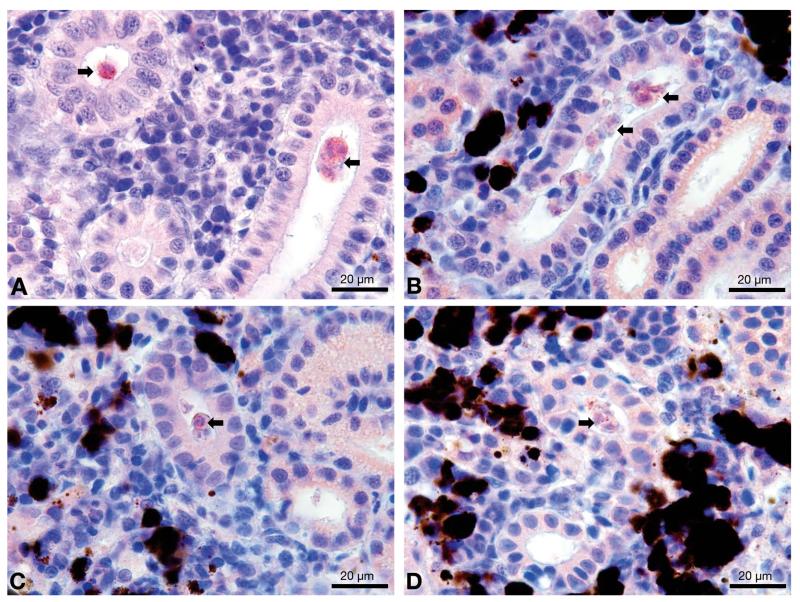

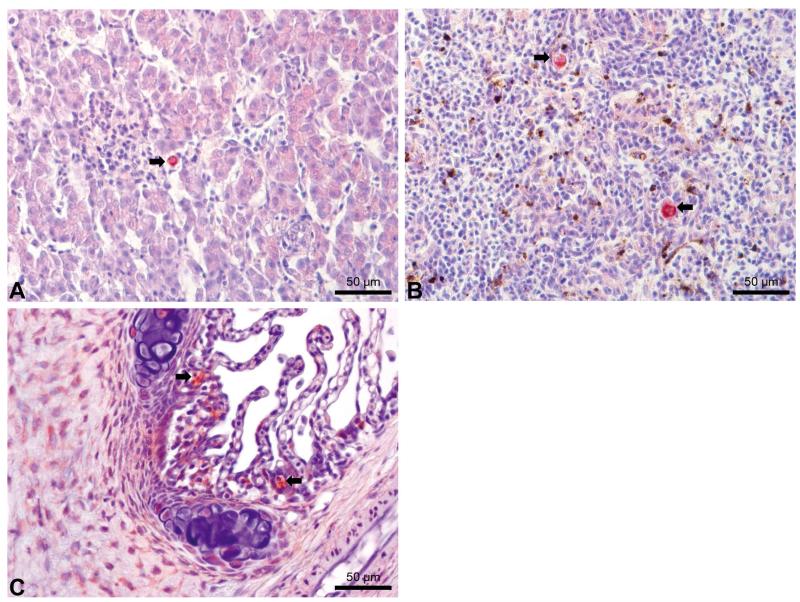

IHC assay of kidney sections from chronically infected brown trout showed intra-luminal sporogonic stages of T. bryosalmonae in the renal tubules and a proliferation of interstitial cells with melano-macrophage centers at all 4 time points (Fig. 3). Maturing spores with polar capsules were observed exclusively in renal tubules. Pre-sporogonic parasite stages were detected in the liver at 26 and 52 wpe (Fig. 4A), and spleen at 26, 52 and 104 wpe (Fig. 4B), while pre-sporogonic stages were present in gills at 52 and 104 wpe only (Fig. 4C). No pre-sporogonic stages were observed in the brain and intestine at any time points. The IHC assay results are summarized in Table 1. None of the control fish showed any positive IHC signals of parasite infection (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Intraluminal sporogonic stages (arrows) of Tetracapsuloides bryosalmonae in the kidney of infected brown trout Salmo trutta sampled at various weeks post-exposure (wpe). (A) 26 wpe, (B) 52 wpe, (C) 78 wpe, (D) 104 wpe. All sections were stained using immunohistochemistry and a hematoxylin counter-stain

Fig. 4.

Developmental stages of Tetracapsuloides bryosalmonae in infected brown trout Salmo trutta sampled at various weeks post-exposure (wpe). (A) Stages in the liver at 52 wpe (arrow); (B) stages in the spleen (arrows) at 104 wpe; (C) stages in the gills at 104 wpe; gill filament is extended with macrophages, lymphocytes and numerous parasites. All sections were stained using immunohistochemistry and a hematoxylin counterstain

Table 1.

Brown trout Salmo trutta infected with Tetracapsuloides bryosalmonae. Summary of IHC assay at the 4 sampling points (weeks post-exposure, wpe). K: kidney; L: liver; S: spleen; Int: intestine; Br: brain; G: gills. (−) negative, (+) positive. Three fish were tested at each time point

| Time (wpe) |

|

Clinical signs |

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length (cm) | Weight (g) | K | L | S | Int | Br | G | ||

| 24 | 14 | 123 | + | + | + | + | − | − | − |

| 52 | 25 | 184 | − | + | + | + | − | − | + |

| 78 | 30 | 299 | − | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| 104 | 33 | 412 | − | + | − | + | − | − | + |

DISCUSSION

We verified the presence and persistence of Tetracapsuloides bryosalmonae developmental stages in laboratory infected brown trout up to 2 yr from initial exposure and showed that they were still capable of infecting the bryozoan host Fredericella sultana. Clinical signs of PKD, including renal hypertrophy, hepatomegaly and splenomegaly were observed only in fish dissected 6–10 wpe. Minor to moderate swelling of kidneys and spleen was observed in 12% of infected brown trout up to 52 wpe, which is in accordance with results of Holzer et al. (2006).

However, most fish sampled at 26, 52, 78 and 104 wpe did not show any clinical signs. These results were not extraordinary since fish usually do not develop clinical signs at 15°C (Clifton-Hadley et al. 1984, Bettge et al. 2009). Foott & Hedrick (1987) found that rainbow trout that survived PKD infection had sporogonic stages inside their kidney tubules for at least 1 yr following exposure to the parasite. This finding was supported by Morris et al. (2000), who found T. bryosalmonae sporogonic stages in the kidney tubules of brown trout and Atlantic salmon, outside the PKD season. In the present study, we observed internal clinical signs in fish 6–10 wpe only; however moderate exophthalmia and darkened skin persisted until 24 wpe.

T. bryosalmonae DNA were detected by PCR in all kidney samples from each fish at the 4 different time points. This accords with results of Schmidt-Posthaus et al. (2012), who detected T. bryosalmonae DNA by PCR in rainbow trout up to 29 wpe (201 d, until the end of the experiment). Schmidt-Posthaus et al. (2013) suggest that the persistence of T. bryosalmonae DNA may be due to either residual parasite DNA post-infection or latent parasite which might be reactivated. Our cohabitation trials with SPF F. sultana indicated that the parasite remains virulent, with successful transmission to the bryozoan host.

In the present study, IHC assay revealed persistence of sporogonic stages of T. bryosalmonae in the kidney lumen of sampled fish at the 4 time points (26, 52, 78 and 104 wpe). Holzer et al. (2006) observed intravascular developmental stages of T. bryosalmonae in the heart of brown trout by in situ hybridization at 30–45 wpe. Our results also agree with Schmidt-Posthaus et al. (2013), who show persistence of parasite in the kidney lumen of brown trout exposed naturally to T. bryosalmonae in warm rivers during summer. In contrast to brown trout, laboratory-infected rainbow trout did not show any positive signals by IHC after 15 wpe (103 d), independent of water temperature (Schmidt-Posthaus et al. 2012). In the same study, Schmidt-Posthaus et al. (2012) comment on the possibility of persistence of viable parasites in kidneys of infected brown trout survivors. Our results indicated that the parasite can indeed remain viable in the host at least up to 104 wpe after initial exposure, but the mechanism by which the parasite maintains itself is still to be elucidated. Holzer et al. (2006) reported that T. bryosalmonae pre-sporogonic stages are present in the spleen and liver of brown trout at 36 wpe. We demonstrated the persistence of presporogonic stages in multiple organs in brown trout (Table 1) and an apparent inability of the fish immune system to eliminate the parasite. It is well known that PCR is more sensitive than IHC, and this is shown in our study by some tissues being PCR positive but IHC negative (Table 1). Similarly, Skovgaard & Buchmann (2012) reported that while all samples that tested positive for T. bryosalmonae by IHC were confirmed with PCR, not all PCR-positive samples could be confirmed by IHC.

Kent & Hedrick (1986) found PKD developmental stages in the blood vessels and blood smears from infected rainbow trout at 4 wpe, suggesting that the parasite first multiplies in the blood before being distributed to other tissues. We were surprised to detect parasite DNA in the blood by PCR 104 wk after initial exposure. Existence of blood stages of many myxozoan species has been studied (Dyková & Lom 1988); myxozoans use the blood for proliferation and transport of developmental stages (Björk & Bartholomew 2010, Holzer et al. 2013). Morris & Adams (2004) recognized a distinct blood form of T. bryosalmonae from those in the kidney interstitium, based on the distribution of carbohydrate in their primary cells. Holzer et al. (2006) reported T. bryosalmonae presporogonic stages in the intravascular tissue of the heart. Blood stages of T. bryosalmonae as revealed by in situ hybridization were small (<25 μm in diameter) and occasionally had only one cell. Such findings suggest that T. bryosalmonae can switch between blood and kidney forms under unknown conditions and be maintained in the host for a long period. Circulation of T. bryosalmonae blood stages may explain the presence of the parasite in other organs (liver, spleen, gills, brain and intestine) 104 wpe.

Ability of the salmonid host to eliminate T. bryosalmonae appears to be dependent on many factors, which include temperature, presence of other co-infections, age and, most importantly host species. Ferguson (1981) reported that the recovery of in fected rainbow trout is facilitated by reduced water temperature. In contrast, Kent & Hedrick (1986) demonstrated the ability of rainbow trout to recover independently of the water temperature (fish were maintained at >15°C); also Morris et al. (2005) found that 10% of naturally infected rainbow trout held in the laboratory for 36 wk (9 mo) after initial exposure showed clinical signs of PKD at constant water temperature (18°C), while, 90% of infected rainbow trout had recovered. Holzer et al. (2006) found that kidney samples of Age 1+ brown trout (second year fish kept in a pond system) were PCR-positive for T. bryosalmonae, which indicate that T. bryosalmonae was still present throughout the second summer. Additionally, in situ hybridization revealed stages of T. bryosalmonae in the epithelium and lumen of the renal tubules in Age 1+ brown trout. Morris & Adams (2008), using IHC, found pseudoplasmodia in the kidney tubules of brown trout infected with T. bryosalmonae at constant water temperature (18°C). We found persistence of T. bryosalmonae sporogonic stages in the kidney tubules of brown trout, suggesting that persistence of parasite depends on the fish species and their immune systems (Kumar et al. 2013a). The above-mentioned results indicate that the parasite can persist for a long period in brown trout regardless of the temperature regime (either at a constant temperature under laboratory conditions, or variable temperature as in a pond system). Additionally, Gay et al. (2001) reported that T. bryosalmonae can develop in the bryozoan F. sultana at water temperatures of 7–8°C, since the spores were present throughout the year. Therefore, our laboratory temperature 15°C (± 1°C) was optimal for both vertebrate and invertebrate hosts and does not interfere with the pathogenesis and development of the parasite.

Schmidt-Posthaus et al. (2012) found that chronically infected rainbow trout (held at 12°C) could completely regenerate renal morphology and eliminate the majority of the parasite. Kumar et al. (2013a) demonstrated similar results in rainbow trout at 16.5°C at 17 wpe using IHC and quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR). The only difference between these 2 studies was the temperature, which appears to in fluence the rate but not the progress of recovery (Ferguson 1981, Clifton-Hadley et al. 1986, Schmidt-Posthaus et al. 2012). In contrast to rainbow trout, our results from brown trout show that this species is unable to completely clear the infection after 104 wpe, while held at constant temperature and the absence of any source of re-infection. We also demonstrated that recovered brown trout were able to infect the bryozoan host up to 104 wpe. This finding suggests that brown trout which survive infection with T. bryosalmonae may act as carriers of the parasite.

Schmidt et al. (1999) attributed the decline of brown trout catches in Switzerland to PKD, which was supported by Wahli et al. (2002, 2007). Wahli et al. (2002) surveyed wild brown trout and rainbow trout, and found disease prevalence ranged between 40 and 100% at some Swiss river sites. Recently, we reported stages of T. bryosalmonae in the statoblasts (dormant stage) of F. sultana, which indicates not only the occurrence of vertical transmission but also the possibility that the parasite can persist in the bryozoan host and be distributed to new locations (Abd-Elfattah et al. 2014). Our current results demonstrate persistence of T. bryosalmonae also in the fish host and their ability to infect F. sultana colonies up to 24 mo from the initial exposure. Taken together, these aspects of the parasite’s biology explain persistence of PKD in endemic waters and farms and its wide geographic distribution. Further studies are needed to address how long the parasite can persist in wild brown trout as well as the role of blood stages in parasite maintenance in the host over long periods.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded in part by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF), Project No. P 22770-B17 and the University of Veterinary Medicine, Vienna (PL 29110263). We thank Dr. S. Atkinson for editing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Ethics statement. This study was approved by the institutional ethics committee of the University of Veterinary Medicine, Vienna, and conducted according to Austrian Law for Animal Experiments (Tierversuchsgesetz) 2012, §26, under Permit No. GZ 68.205/0247-II/3b/2011.

LITERATURE CITED

- Abd-Elfattah A, Fontes I, Kumar G, Soliman H, Hartikainen H, Okamura B, El-Matbouli M. Vertical transmission of Tetracapsuloides bryosalmonae (Myxozoa), the causative agent of salmonid proliferative kidney disease. Parasitology. 2014;141:482–490. doi: 10.1017/S0031182013001650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson CL, Canning EU, Okamura B. 18S rDNA sequences indicate that PKX organism parasitizes Bryozoa. Bull Eur Assoc Fish Pathol. 1999;19:94–97. [Google Scholar]

- Bettge K, Wahli T, Segner H, Schmidt-Posthaus H. Proliferative kidney disease in rainbow trout: time- and temperature-related renal pathology and parasite distribution. Dis Aquat Org. 2009;83:67–76. doi: 10.3354/dao01989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Björk SJ, Bartholomew JL. Invasion of Ceratomyxa shasta (Myxozoa) and comparison of migration to the intestine between susceptible and resistant fish hosts. Int J Parasitol. 2010;40:1087–1095. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canning EU, Curry A, Feist SW, Longshaw M, Okamura B. Tetracapsula bryosalmonae n. sp. for PKX organism, the cause of PKD in salmonid fish. Bull Eur Assoc Fish Pathol. 1999;19:203–206. [Google Scholar]

- Canning EU, Tops S, Curry A, Wood TS, Okamura B. Ecology, development and pathogenicity of Buddenbrockia plumatellae Schröder, 1910 (Myxozoa, Malacosporea) (syn. Tetracapsula bryozoides) and establishment of Tetracapsuloides n. gen. for Tetracapsula bryosalmonae. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 2002;49:280–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2002.tb00371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifton-Hadley RS, Feist SW. Proliferative kidney disease in brown trout Salmo trutta: further evidence of a myxosporean aetiology. Dis Aquat Org. 1989;6:99–103. [Google Scholar]

- Clifton-Hadley RS, Bucke D, Richards RH. Proliferative kidney disease of salmonid fish: a review. J Fish Dis. 1984;7:363–377. [Google Scholar]

- Clifton-Hadley RS, Richards RH, Bucke D. Proliferative kidney disease (PKD) in rainbow trout Salmo gairdneri: further observations on the effects of water temperature. Aquaculture. 1986;55:165–171. [Google Scholar]

- de Kinkelin P, Loriot B. A water temperature regime which prevents the occurrence of proliferative kidney disease (PKD) in rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss (Walbaum) J Fish Dis. 2001;24:489–493. [Google Scholar]

- Dyková I, Lom J. Review of pathogenic myxosporeans in intensive culture of carp (Cyprinus carpio) in Europe. Folia Parasitol. 1988;35:289–307. [Google Scholar]

- El-Matbouli M, Hoffmann RW. Influence of water quality on the outbreak of proliferative kidney disease field studies and exposure experiments. J Fish Dis. 2002;25:459–467. [Google Scholar]

- El-Matbouli M, Fischer-Scherl T, Hoffmann RW. Present knowledge on the life cycle, taxonomy, pathology and therapy of some Myxosporea spp. important for fresh water fish. Annu Rev Fish Dis. 1992;2:367–402. [Google Scholar]

- Feist SW, Longshaw M, Canning EU, Okamura B. Induction of proliferative kidney disease (PKD) in rainbow trout Oncorhynchus mykiss via the bryozoan Fredericella sultana infected with Tetracapsula bryosalmonae. Dis Aquat Org. 2001;45:61–68. doi: 10.3354/dao045061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feist SW, Peeler EJ, Gardiner R, Smith E, Longshaw M. Proliferative kidney disease and renal myxosporidiosis in juvenile salmonids from rivers in England and Wales. J Fish Dis. 2002;25:451–458. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson HW. The effects of water temperature on the development of proliferative kidney disease in rainbow trout, Salmo gairdneri Richardson. J Fish Dis. 1981;4:175–177. [Google Scholar]

- Foott JS, Hedrick RP. Seasonal occurrence of the infectious stage of proliferative kidney disease (PKD) and resistance of rainbow trout, Salmo gairdneri Richard son, to reinfection. J Fish Biol. 1987;30:477–483. [Google Scholar]

- Gay M, Okamura B, de Kinkelin P. Evidence that infectious stages of Tetracapsula bryosalmonae for rainbow trout Oncorhynchus mykiss are present throughout the year. Dis Aquat Org. 2001;46:31–40. doi: 10.3354/dao046031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabner DS, El-Matbouli M. Transmission of Tetracapsuloides bryosalmonae (Myxozoa: Malacosporea) to Fredericella sultana (Bryozoa: Phylactolaemata) by various fish species. Dis Aquat Org. 2008;79:133–139. doi: 10.3354/dao01894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabner DS, El-Matbouli M. Comparison of the susceptibility of brown trout (Salmo trutta) and four rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) strains to the myxozoan Tetracapsuloides bryosalmonae, the causative agent of proliferative kidney disease (PKD) Vet Parasitol. 2009;165:200–206. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2009.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabner DS, El-Matbouli M. Tetracapsuloides bryosalmonae (Myxozoa: Malacosporea) portal of entry into the fish host. Dis Aquat Org. 2010;90:197–206. doi: 10.3354/dao02236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedrick RP, MacConnell E, de Kinkelin P. Proliferative kidney disease of salmonid fish. Annu Rev Fish Dis. 1993;3:277–290. [Google Scholar]

- Hedrick RP, Baxa DV, De Kinkelin P, Okamura B. Malacosporean-like spores in urine of rainbow trout react with antibody and DNA probes to Tetracapsuloides bryosalmonae. Parasitol Res. 2004;92:81–88. doi: 10.1007/s00436-003-0986-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzer AS, Sommerville C, Wootten R. Molecular studies on the seasonal occurrence and development of five myxozoans in farmed Salmo trutta L. Parasitology. 2006;132:193–205. doi: 10.1017/S0031182005008917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzer AS, Bartos̆ová P, Pecková H, Tyml T, et al. ‘Who’s who’ in renal sphaerosporids (Bivalvulida: Myxozoa) from common carp, Prussian carp and goldfish — molecular identification of cryptic species, blood stages and new members of Sphaerospora sensu stricto. Parasitology. 2013;140:46–60. doi: 10.1017/S0031182012001175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent ML, Hedrick RP. Development of the PKX myxosporean in rainbow trout Salmo gairdneri. Dis Aquat Org. 1986;1:169–182. [Google Scholar]

- Kent ML, Khattra J, Hervio DML, Devlin RH. Ribosomal DNA sequence analysis of isolates of the PKX myxosporean and their relationship to members of the genus Sphaerospora. J Aquat Anim Health. 1998;10:12–21. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar G, Abd-Elfattah A, Saleh M, El-Matbouli M. Fate of Tetracapsuloides bryosalmonae (Myxozoa) after infection of brown trout (Salmo trutta) and rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) Dis Aquat Org. 2013a;107:9–18. doi: 10.3354/dao02665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar G, Abd-Elfattah A, Soliman H, El-Matbouli M. Establishment of medium for laboratory cultivation and maintenance of Fredericella sultana for in vivo experiments with Tetracapsuloides bryosalmonae (Myxo zoa) J Fish Dis. 2013b;36:81–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2761.2012.01440.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris DJ, Adams A. Localization of carbohydrate terminals on Tetracapsuloides bryosalmonae using lectin histochemistry and immunogold electron microscopy. J Fish Dis. 2004;27:37–45. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2761.2003.00509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris DJ, Adams A. Transmission of Tetracapsuloides bryosalmonae (Myxozoa: Malacosporea), the causative organism of salmonid proliferative kidney disease, to the freshwater bryozoan Fredericella sultana. Parasitology. 2006;133:701–709. doi: 10.1017/S003118200600093X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris DJ, Adams A. Sporogony of Tetracapsuloides bryosalmonae in the brown trout Salmo trutta and the role of the tertiary cell during the vertebrate phase of myxozoan life cycles. Parasitology. 2008;135:1075–1092. doi: 10.1017/S0031182008004605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris DJ, Adams A, Feist SW, McGeorge J, Richards RH. Immunohistochemical and PCR studies of wild fish for Tetracapsula bryosalmonae (PKX), the causative organism of proliferative kidney disease. J Fish Dis. 2000;23:129–135. [Google Scholar]

- Morris DJ, Ferguson HW, Adams A. Severe, chronic proliferative kidney disease (PKD) induced in rainbow trout Oncorhynchus mykiss held at a constant 18°C. Dis Aquat Org. 2005;66:221–226. doi: 10.3354/dao066221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura B, Hartikainen H, Schmidt-Posthaus H, Wahli T. Life cycle complexity, environmental change and the emerging status of salmonid proliferative kidney disease. Freshw Biol. 2011;56:735–753. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt H, Bernet D, Wahli T, Meier W, Burkhardt-Holm P. Active biomonitoring with brown trout and rainbow trout in diluted sewage plant effluents. J Fish Biol. 1999;54:585–596. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt-Posthaus H, Bettge K, Segner H, Forster U, Wahli T. Kidney pathology and parasite intensity in rainbow trout Oncorhynchus mykiss surviving proliferative kidney disease: time course and influence of temperature. Dis Aquat Org. 2012;97:207–218. doi: 10.3354/dao02417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt-Posthaus H, Steiner P, Müller B, Casanova-Nakayama A. Complex interaction between proliferative kidney disease, water temperature and concurrent nematode infection in brown trout. Dis Aquat Org. 2013;104:23–34. doi: 10.3354/dao02580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skovgaard A, Buchmann K. Tetracapsuloides bryosalmonae and PKD in juvenile wild salmonids in Denmark. Dis Aquat Org. 2012;101:33–42. doi: 10.3354/dao02502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterud E, Forseth T, Ugedal O, Poppe TT, et al. Severe mortality in wild Atlantic salmon Salmo salar due to proliferative kidney disease (PKD) caused by Tetracapsuloides bryosalmonae (Myxozoa) Dis Aquat Org. 2007;77:191–198. doi: 10.3354/dao01846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahli T, Knuesel R, Bernet D, Segner H, et al. Proliferative kidney disease in Switzerland: current state of knowledge. J Fish Dis. 2002;25:491–500. [Google Scholar]

- Wahli T, Bernet D, Steiner PA, Schmidt-Posthaus H. Geographic distribution of Tetracapsuloides bryosalmonae infected fish in Swiss rivers: an update. Aquat Sci. 2007;69:3–10. [Google Scholar]