Abstract

Background

Proteoglycans of the arterial wall play a critical role in vascular integrity and the development of atherosclerosis owing to their ability to organize extracellular matrix molecules and to bind and retain atherogenic apolipoprotein (apo)-B containing lipoproteins. Prior studies have suggested a role for biglycan in aneurysms and in atherosclerosis. Angiotensin II (angII) infusions into mice have been shown to induce abdominal aortic aneurysm development, increase vascular biglycan content, increase arterial retention of lipoproteins, and accelerate atherosclerosis.

Objective

The goal of this study was to determine the role of biglycan in angII-induced vascular diseases.

Design

Biglycan-deficient or biglycan wildtype mice crossed to LDL receptor deficient (Ldlr−/−)mice (C57BL/6 background) were infused with angII (500 or 1000 ng/kg/min) or saline for 28 days while fed on normal chow, then pumps were removed, and mice were switched to an atherogenic Western diet for 6 weeks.

Results

During angII infusions, biglycan-deficient mice developed abdominal aortic aneurysms, unusual descending thoracic aneurysms, and a striking mortality caused by aortic rupture (76% for males and 48% for females at angII 1000 ng/kg/min). Histological analyses of non-aneurysmal aortic segments from biglycan-deficient mice revealed a deficiency of dense collagen fibers and the aneurysms demonstrated conspicuous elastin breaks. AngII infusion increased subsequent atherosclerotic lesion development in both biglycan-deficient and biglycan wildtype mice. However, the biglycan genotype did not affect atherosclerotic lesion area induced by the Western diet after treatment with angII. Biglycan-deficient mice exhibited significantly increased vascular perlecan content compared to biglycan wildtype mice. Analyses of the atherosclerotic lesions demonstrated that vascular perlecan co-localized with apoB, suggesting that increased perlecan compensated for biglycan deficiency in terms of lipoprotein retention.

Conclusions

Biglycan deficiency increases aortic aneurysm development and is not protective against the development of atherosclerosis. Biglycan deficiency leads to loosely packed aortic collagen fibers, increased susceptibility of aortic elastin fibers to angII-induced stress, and up-regulation of vascular perlecan content.

Keywords: extracellular matrix, proteoglycans, atherosclerosis, aortic aneurysms, elastin

1. INTRODUCTION

Biglycan, a member of the small leucine-rich proteoglycan family, may contribute to normal collagen fiber formation[1, 2] and has been consistently found in association with elastin fibers in a number of tissues, including the aorta[3, 4]. Biglycan is found throughout the vasculature, and may play a key role in both aortic aneurysms and atherosclerosis.

Aortic aneurysms are a relatively common pathology characterized by segmental weakening of the artery and luminal dilation, which occur in the thoracic or abdominal regions. Unless detected by screening, aneurysms remain clinically silent until presenting catastrophically with rupture and fatal hemorrhage, and are responsible for over 15,000 deaths annually in the United States [5]. The main determinants of the mechanical properties of normal aortae are fibrillar collagens and elastin fibers [6], and the development of aortic aneurysms correlates with disruption of these key structural molecules. Moreover, biglycan has been reported to be substantially suppressed in human abdominal aortic aneurysms [7, 8]. A prior study demonstrated spontaneous aortic dissections in biglycan-deficient mice on the BALB/cA background[3]. Thus, biglycan may play a role in aortic structural integrity and development of aortic aneurysms.

Atherosclerosis is the major underlying cause of cardiovascular events including myocardial infarctions, which is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. We and others have demonstrated the strong presence of biglycan within atherosclerotic lesions, co-localized with apolipoprotein (apo)B, the major protein of atherogenic lipoproteins[9-11]. Over-expression of biglycan increases arterial retention of apoB-lipoproteins and accelerates atherosclerosis[9, 12]. Thus, biglycan may also play a role in atherosclerosis development.

Biglycan is abundant in normal human aortae, particularly within the intima and media, which are regions affected by aneurysms and dissections. Nevertheless, the molecule is minimally expressed in these regions of normal murine aortae. In previous publications, we reported an approach to ‘humanize’ the proteoglycan profile of murine arteries through a short (four-week) period of angiotensin II (angII) infusions by osmotic pump, during which the animals are fed on normal rodent chow [9, 13]. This approach increases intimal thickness, similar to the diffuse intimal thickening found in normal human arteries [10], and it increases intimal and medial content of biglycan through transient induction of TGFß [9, 13]. In the absence of concurrent, severe hypercholesterolemia, no or nearly no aortic aneurysms or atherosclerotic lesions form[14]. On the other hand, angII infusions in severely hypercholesterolemic mice are a well-established model of aortic aneurysms[15]. Importantly, the structural and compositional changes induced in the aorta by angII infusion persist after removal of the osmotic pump. We have demonstrated that brief prior exposure to angII primes the arteries to trap circulating apoB-lipoproteins, thereby accelerating the development of atherosclerosis during subsequent hypercholesterolemia [9], consistent with the response-to-retention hypothesis of atherogenesis [16]. Thus, angII infusions in mice are a model for a humanized aortic proteoglycan profile, aneurysm development, and atherosclerosis.

An essential tool to study biglycan function in vivo is the biglycan-deficient mouse, which was developed by Young et al to study musculoskeletal diseases and found to have osteoporosis [17]. Biglycan-deficient mice on the BALB/cA background develop spontaneous vascular ruptures owing to defects in adventitial collagen, but these mice show no abnormalities in elastin[3]. We previously bred the biglycan knock-out allele into the C57BL/6J background, which unlike BALB/cA mice, develop no spontaneous vascular ruptures [18] and hence seemed ideal to expose to angII infusions. The goal of our current study was to determine the role of biglycan in the development of aortic aneurysms and atherosclerosis in mice infused with angII or saline.

2. MATERIALS and METHODS

2.1 Animals

All animal care and experimental procedures were approved by the University of Kentucky Animal Care Committee and conformed to Public Health Service policy on the humane care and use of laboratory animals. Biglycan-deficient and littermate control biglycan wild-type mice, backcrossed five times onto C57BL/6J, were crossed with LDL receptor deficient (Ldlr−/−) mice, also on the C57BL/6J background. Thus, all mice were LDL receptor-deficient and on the same genetic background. Because biglycan is located on the X chromosome, the experimental mice for this study were generated by crossing Bgn+/− females either with Bgn+/0 littermate males (which gave Bgn +/+ and Bgn +/− females as well as Bgn+/0 and Bgn−/0 males) or with Bgn −/0 littermate males (which gave Bgn +/− and Bgn −/− females as well as Bgn +/0 and Bgn −/0 males) and then discarding heterozygous female offspring. Thus, wildtype and biglycan deficient males were true littermates, but biglycan wildtype and deficient females came from closely related litters within our single colony. In all cases, the breeders were true littermates. All mice were housed in a temperature-controlled facility with 12 hour light/dark cycles, and fed ad libitum on normal rodent chow with free access to water.

2.2 Mouse models and treatments

Mice weighing at least 20 g were implanted subcutaneously with Alzet osmotic minipumps (model 1004; Alzet Scientific Products, Mountain View, CA, USA) containing angII (to achieve rates of 500 or 1,000 ng/kg/min) or saline for 28 days. The pumps were removed after 28 days to ensure complete cessation of infusions and the prompt return of angII levels to normal. The mice were then fed on an atherogenic Western diet (0.15% cholesterol and 21% fat; Harlan Laboratories, catalog No. 88137, Madison, WI, USA) for the next 6 weeks. At the end of this period, mice were anesthetized by isoflurane inhalation, at which time body weight was measured. Mice were perfused through the left ventricle at constant, near-physiological pressure with 10 ml phosphate-buffered saline, with exsanguination via vena caval puncture, which ensured euthanasia. Blood and organs including major vessels were collected for metabolic assays or analysis of aneurysms or atherosclerosis.

2.3 Metabolic characterization

Systolic blood pressure was measured in conscious mice during the different treatment periods using an automatic tail-cuff apparatus coupled to a personal computer-based data-acquisition system (RTBP1007; Kent Scientific, Litchfield , CT, USA), with each measurement performed at the same time of day by the same operator. For each measurement, 20 chronological readings were obtained from each mouse to yield a mean blood pressure of the day. Plasma total cholesterol and triglyceride concentrations were determined using enzymatic assay kits (Wako Chemical Co., Richmond, VA, USA). Plasma TGFβ1 was measured with the TGFβ1 Emax® ImmunoAssay system (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Samples were acid-activated for total TGFβ1 quantification.

2.4 Analysis of aortic aneurysms

After fixation and the removal of peri-aortic fat, each aorta was photographed using Nikon Image Software. Three aortas from each group were embedded in OCT and serially sectioned using a cryostat (10-μm sections; 9 sections/slide, each slide representing ~100-μm distance of the aortic segment). Sections were fixed with absolute alcohol then stained with Verhoeff's hematoxylin, followed by differentiation in 2% ferric chloride solution, and finally counterstained with Van Gieson's solution (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA; HT25A). Collagen was quantified by Sirius red staining of aortic sections followed by birefringence analysis as described previously[19, 20].

2.5 Quantification and immunostaining of atherosclerotic lesions

Atherosclerosis was quantified in the aortic sinus and the aortic intimal surface as described previously[9]. Aortic sinus sections (10 μm thick) collected every 90 μm were stained with Oil Red O (Fluka, St. Louis, MO, USA) and quantified using computer-assisted morphometry with Nikon Image software. Aortic intimal surface lesions were stained with Sudan IV (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH, USA) then evaluated by en-face quantification of lesions. All quantifications were performed in duplicate by observers blinded to the group assignments of the mice. Immunofluorescence staining was performed using primary antibodies against biglycan (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), perlecan (Accurate, Westbury, NY, USA), or apoB (Biodesign International, Saco, ME, USA) and analyzed by confocal microscopy with the use of a Leica AOBS TCS SP5 inverted laser scanning confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems Inc. Mannheim, Germany). Autofluorescence was eliminated by Sudan Black treatment as previously described[13]. Negative controls were performed using isotype-matched irrelevant primary antibodies, no primary antibody, or no secondary antibody. Perlecan immunostaining was performed on aortic cross sections and visualized by light microscopy and quantified as % aortic area using ImageJ software as previously described[13].

2.6 Immunoblots

Carotid protein was extracted by TRIZOL reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) then dialyzed against 0.1% SDS to obtain maximal protein yield. Equal amounts of protein were separated by SDS-PAGE using 8% gels followed by immunoprobing with an anti-perlecan antibody (Accurate, Westbury, NY, USA). Blotting for β-actin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA; AF2066) served as a loading control. Quantification was performed using ImageJ densitometry software (NIH, USA).

2.7 Statistical analyses

All data are presented as means ± SEM. Statistical differences were assessed by two-way ANOVA: to assess effects of biglycan genotype and infusions (angII or saline), followed by pairwise comparisons by Holm-Sidak method using Sigma Stat software (Jandel Scientifc). P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Biglycan deficiency induced unexpectedly high rates of vascular rupture and mortality of mice during angII infusion

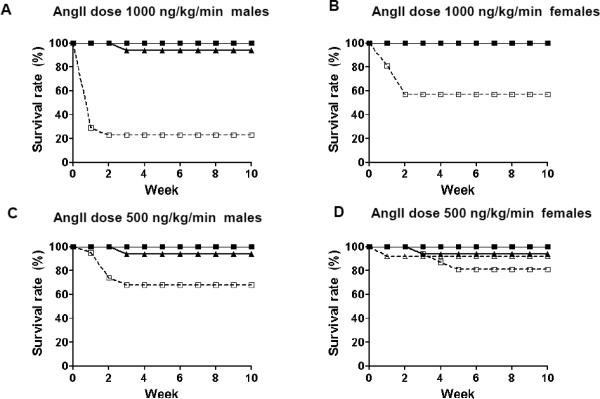

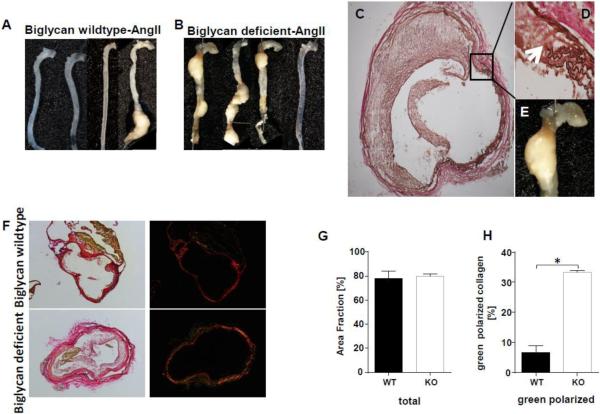

Diet-induced hyperlipidemia at the same time as angII infusion is known to increase abdominal aortic aneurysm development in mice [14]. To avoid this effect, we gave biglycan-deficient or biglycan wildtype Ldlr−/− mice saline or angII (1000 ng/kg/min) via osmotic pumps for 4 weeks while feeding them on normal chow. Surprisingly, even in the absence of a high-cholesterol diet, biglycan-deficient mice exhibited high mortality, with 76% of male and 48% of female biglycan-deficient mice dying during the first 1-2 weeks of angII infusions (Fig. 1A,B). The deaths were primarily due to hemothorax (52%) or hemoabdomen (33%); in 2 cases (15%) cause of death was not determined. Because of this high mortality, we repeated our studies using a lower dose of angII (500 ng/kg/min), which decreased the mortality: 32% of male and 19% of female biglycan deficient mice died (Figs. 1C,D). Again, the cause of death was either hemothorax (89%) or hemoabdomen (11%). For biglycan wildtype mice, 0 of 17 infused with angII 1000 ng/kg/min and only 1 of 25 infused with angII 500 ng/kg/min developed an aortic aneurysm, which is characteristic for Ldlr−/− mice fed on normal chow. In mice that survived the infusions, intact aortae were removed and photographed. Seven out of 26 surviving angII-infused biglycan deficient mice had developed unusual descending thoracic aortic aneurysms (Fig. 2A,B), in addition to or even instead of the well-described ascending thoracic or abdominal aortic aneurysms typically seen in angII-infused mice with concurrent diet-induced hypercholesterolemia [14]. In total, 37% of biglycan-deficient mice that survived the infusion with angII at 1000 ng/kg/min and 43% of biglycan-deficient mice that survived infusion with angII at 500 ng/kg/min exhibited thoracic aortic aneurysms. Histological analysis of descending thoracic aneurysms (Fig. 2C-E) and abdominal aortic aneurysms (not shown) in these surviving mice revealed conspicuous breaks in medial elastin. Aortic collagen was stained by Sirius red. Analysis of the area fraction of Sirius red viewed by normal light microscopy revealed no difference between the genotypes (Fig. 2F,G). Of note birefringence analysis showed that angII-infused biglycan deficient mice had significantly more green polarized collagen indicating thinner or more loosely packed collagen fibers compared to angII-infused biglycan wildtype mice (Fig. 2F,H). These data suggest that biglycan deficiency impairs the formation of dense collagen fiber networks in the aortic wall.

Figure 1. Biglycan deficiency induces unexpectedly high rates of high mortality during angII infusion.

Biglycan-deficient (KO; open symbols, dashed lines) or biglycan wildtype (WT; filled symbols, solid lines) Ldlr−/− mice on normal chow received osmotic mini-pumps filled with saline (triangles) or angII (squares) providing a dose of 1,000 ng/kg/min (A: males, B: females) or 500 ng/kg/min (C: males, D: females). After 28 days of infusion, the pumps were removed, and mice were then begun on a Western diet for 6 weeks. N=11-21/group each gender. Curves for groups with zero mortality are superimposed and may not all be visible.

Figure 2. Biglycan deficiency induces unexpectedly high rates of aortic aneurysms during angII infusion without diet-induced atherogenic hypercholesterolemia.

A. Unruptured aortae from biglycan wildtype (panel A) and biglycan deficient (panel B) Ldlr−/− mice infused with angII at 500 ng/kg/min for 4 weeks then fed on Western diet for 6 weeks were removed and photographed. Shown are 4 mice/group representative of N=8-13 mice of each gender per group. C-E: Thoracic aortic aneurysms were embedded in OCT, sectioned through the aneurysm then stained with Verhoeff's hematoxylin. Shown are representative photos of thoracic aortic aneurysms from angII-treated biglycan-deficient Ldlr−/− mice. C shows an aorta at 4X magnification. D is a 40X magnification of the indicated region from panel C showing the elastin breaks (arrows). E shows the gross appearance of the thoracic aneurysm. F: Non-aneurysm aortic sections from angII-infused biglycan-deficient and biglycan wildtype mice were stained with Sirius red. G: Collagen area was quantified in angII-infused biglycan deficient and biglycan wildtype mice as area fraction (%) of total collagen staining, through analysis of light microscopic images that had been prepared as in panel F. H: Under polarized light the proportion of green polarized collagen to total polarized collagen(red and green) was substantially increased in biglycan deficient compared to wildtype mice. Panels G,H display means±SEM, n=3/group.* represents P<0.01

3.2 No effect of biglycan genotype on atherosclerosis induced by a Western diet after priming with angII infusions

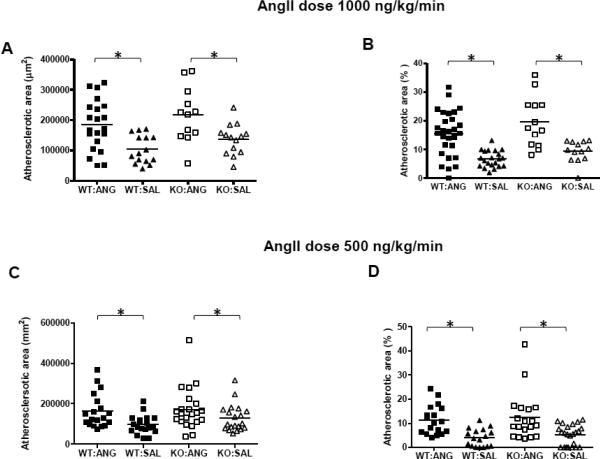

Mice that survived angII infusions had pumps removed at day 28 to ensure cessation of infusions, and then were fed on an atherogenic Western diet to cause atherosclerosis development. We have previously demonstrated that infusion of angII up-regulates vascular biglycan and perlecan content, which then predisposes to accelerated atherosclerosis development [9]. As expected, angII infusions at either dose elevated systolic blood pressure (this did not reach statistical significance in the 1000ng/kg/min dose group, perhaps because of small numbers and selection bias among the surviving mice), without affecting body weight, total plasma cholesterol or triglyceride levels (Table 1). There was no effect of biglycan deficiency on metabolic parameters (Table 1); however, biglycan-deficient mice exhibited lower body weight compared to biglycan wildtype mice (Table 1), which is consistent with our previous findings [21]. After the 6-week Western diet feeding, mice that survived angII infusion (1000 ng/kg/min) developed increased atherosclerotic lesion areas compared to saline-infused animals (approximately 2 fold for aortic sinus and 3 fold for en face aortic surface, both p<0.001, Figure 3A, B). However, biglycan-deficient mice were not protected from atherosclerosis development in response to angII at either site. Similarly, angII infusion of 500 ng/kg/min also induced a 2-fold increase in the lesion area compared to saline infusion (p=0.003 for aortic sinus and p<0.001 for en face surface). Again, no differences in atherosclerotic areas were found between angII treated biglycan-deficient or wildtype mice (Figure 3C, D).

Table 1.

Effect of biglycan deficiency on metabolic parameters

| AngII dose | Parameter | Gender | WT: angII | WT: saline | KO: angII | KO: saline | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1000 ng/kg/min | N | M/F | 17M/12F | 15M/11F | 4M/11F | 4M/13F | |

| Body weight (g) | Male | 36.8±1.0 | 38.4±1.2 | 34.2±2.0 | 33.7±2.0 | a | |

| Female | 25.6±0.8 | 27.2±1.5 | 24.6±0.6 | 25.3±0.7 | NS | ||

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | Male | 1845±136 | 2009±119 | 2437±466 | 1754±307 | NS | |

| Female | 1224±101 | 1314±88 | 1213±6 | 1150±0 | NS | ||

| Triglyceride (mg/dl) | Male | 510±42 | 513±42 | 333±2 | 525±4 | NS | |

| Female | 240±2 | 271±2 | 291±8 | 339±34 | NS | ||

| Total TGFβ (pg/ml) | Both | 10748±2270 | 7349±1793 | 9041±1029 | 9906±1812 | NS | |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | Both | 157±5 | 145±4 | 149±3 | 145±4 | NS | |

| 500 ng/kg/min | N | M/F | 12M/13F | 10M/12F | 13M/13F | 11M/11F | |

| Body weight (g) | Male | 36.6±1.2 | 34.6±1.3 | 32.1±1.0 | 30.7±1.2 | a | |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | Male | 1517±61 | 1414±55 | 1459±49 | 1532±61 | NS | |

| Female | 1340±0 | 1264±7 | 1223±0 | 1316±51 | c | ||

| Triglyceride (mg/dl) | Male | 510±36 | 512±33 | 502±6 | 613±66 | NS | |

| Female | 388±39 | 380±32 | 292±5 | 337±28 | a | ||

| Total TGFβ (pg/ml) | Both | 9001±1667 | 9080±916 | 9391±1230 | 9164±1596 | NS | |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | Both | 156±4 | 143±4 | 150±4 | 143±3 | b |

Biglycan deficient (KO) or biglycan wildtype (WT) mice received osmotic mini-pumps filled with saline or angII providing a dose of 1,000 ng/kg/min or 500 ng/kg/min. After 28 days of infusion, the pumps were removed, and then mice were fed on a Western diet for 6 weeks. All parameters shown were measured at the end of the 10 week study except systolic blood pressure which is an average of daily readings 5 days/week x 4 weeks during the pump infusions. Data shown are means ± SEM for surviving N as indicated. All analyses were done by two-way ANOVA followed by pairwise comparisons by Holm-Sidak method using Sigma Stat software. NS, not significant. a, P<0.05 for WT compared to KO. b, p<0.05 for angll compared to saline. c, significant interaction between the effects of genotype and angII infusion means that main effects cannot be properly interpreted.

Figure 3. No effect of biglycan genotype on atherosclerosis induced by a Western diet that was initiated after pre-treating the animals with angII infusions.

Biglycan wildtype (WT; solid symbols) or biglycan deficient (KO; open symbols) Ldlr−/− mice received osmotic mini-pumps filled with saline (SAL, triangles) or angII (ANG, squares) providing a dose of 1,000 ng/kg/min (A, B) or 500 ng/kg/min (C, D) while they were fed on normal chow. After 28 days of infusion, the pumps were removed, and mice were then switched to a Western diet for 6 weeks. Atherosclerotic area was determined in histologic sections from the aortic sinus (A and C), and on the aortic surface by staining en face (B and D). Each symbol represents the lesion area of an individual mouse and each horizontal line represents the mean for the group. All statistical analyses were done by two-way ANOVA. * represents P<0.01.

3.3 Novel role for biglycan in regulating aortic perlecan content

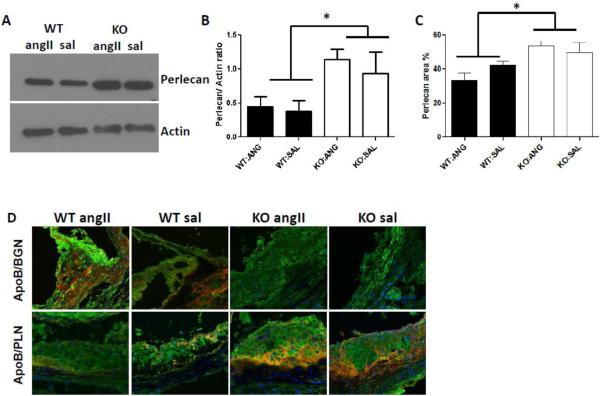

Biglycan is the arterial proteoglycan that most prominently co-localizes with apoB in both human and murine atherosclerosis [10, 11, 22]. However, in murine atherosclerosis arterial perlecan also robustly co-localizes with apoB, and molecular manipulations of perlecan demonstrate that it mediates apoB-lipoprotein retention and the development of atherosclerosis [22-24]. To determine if biglycan deficiency altered vascular perlecan content, we analyzed the perlecan content of carotid arteries, aortas, and aortic root sections from biglycan wildtype and deficient mice after four weeks of angII infusion and six weeks on the Western diet. Compared to biglycan wildtype mice, the biglycan-deficient mice exhibited significantly increased perlecan content in carotid arteries (Fig. 4A,B; P=0.008) and aortae (Fig. 4C, P<0.05). In contrast, there was no effect of angII on vascular perlecan content regardless of biglycan genotype (Fig 4A-C). Aortic root sections were double stained for biglycan and apoB, or for perlecan and apoB. Consistent with our prior work[9], apoB staining of aortic roots from angII-infused mice was more intense than the staining of samples from saline-infused mice. In atherosclerotic lesions of biglycan wildtype mice, apoB co-localized with both biglycan and perlecan (Fig. 4D). In biglycan deficient mice there was striking co-localization of apoB with perlecan (Fig. 4D), suggesting that vascular perlecan is sufficient to mediate apoB retention in the absence of biglycan.

Figure 4. Novel role for biglycan in regulating aortic perlecan content.

A. Biglycan wildtype (WT) and biglycan deficient (KO) Ldlr−/− mice were infused with angII at 500 ng/kg/min or saline (sal) for 28 days while the animals were fed on normal chow. The pumps were then removed, and mice were switched to a Western diet for 6 weeks. Carotid arteries were collected at the end of the studies, and protein was extracted and immunoblotted for perlecan. Actin is shown as the loading control. Each lane represents an individual mouse representative of N=4/group. B. Densitometry quantification of immunoblots. Displayed is carotid perlecan content, normalized to actin content. Shown are means ± SEM for N=4/group. * P< 0.05. C. Aortic cross sections were immunostained for perlecan, and perlecan area is expressed as % aortic area. Shown are means ± SEM for N=6-10/group. D. Sections of atherosclerotic plaques in the aortic sinus were immunostained for apoB (green) and biglycan (BGN, red) or perlecan (PLN, red), with nuclei stained by DAPI (blue). Yellow demonstrates co-localization of apoB with each proteoglycan, as indicated. In each photo, the lumen is on the upper left side of the image. Photos shown are representative for N=3-4 mice/group (group indicated at the top of each column) magnified 630X.

4. DISCUSSION

The purpose of the present study was to determine the role of biglycan in angII-induced vascular diseases – namely, aortic aneurysms and atherosclerosis. Biglycan-deficient mice (of both genders) given infusions of angII had strikingly high mortality, which resulted from ruptured aortic aneurysms, even though the animals consumed normal chow during the infusions. In addition to displaying abdominal aortic aneurysms, angII-infused biglycan-deficient mice exhibited a high frequency of unusual descending thoracic aneurysms. Both the abdominal and thoracic aortic aneurysms were characterized by elastin breaks typical for angII-induced aneurysms. In aortas of biglycan deficient mice, we found more loosely packed collagen fibers, as demonstrated by strongly increased proportion of green birefringence. The formation of loosely packed, irregular collagen fibril networks in the absence of biglycan is in line with findings in bone[1], in the heart after myocardial infarction[25] and in the aorta[3]. Surprisingly, the biglycan-deficient mice had also increased vascular perlecan content, suggesting a compensatory response of the vasculature to the genetic deletion of biglycan.

In human abdominal aortic aneurysms, biglycan mRNA levels were found to be markedly decreased compared to the levels in normal arteries, whereas mRNA levels for decorin, another small leucine rich proteoglycan, remained unchanged [7, 8]. Immunohistochemical analysis of human abdominal aortic aneurysms also demonstrated that loss of biglycan staining was associated with elastin fiber breakdown, whereas decorin was focally increased in aortic media [26]. Although biglycan and decorin are closely related members of the small leucine-rich proteoglycan family, decreases in biglycan expression appear to be uniquely associated with aortic aneurysms.

Mechanisms by which biglycan might support vascular integrity are unclear. In the present study, biglycan deficient mice on the C57BL/6J background had normal survival and no spontaneous vascular pathology under control conditions (saline infusion), but upon angII infusion, they exhibited a remarkably high incidence of aortic rupture. The incidence of rupture was higher in males than females and the location was more in the thoracic than abdominal aorta. The reason for the preferential increase in thoracic aortic aneurysms in biglycan-deficient mice is unclear. However, regional differences in aortic pathologies have been attributed to different embryonic origins of smooth muscle cells in different regions of the aortae[27, 28]; biglycan may be expressed to a different extent in these different smooth muscle lineages, which might account for these observations. Importantly, biglycan deficient mice in the present study (C57BL/6J background) developed classical breaks in aortic elastin upon angII infusions. Thus, this murine model recapitulates key features of human aortic aneurysms and indicates a role for biglycan in the protection of elastin fibers when under stress.

Elastin is the most abundant protein of the artery wall [29]. Elastin is secreted as the soluble precursor tropoelastin, which is then stabilized by cross links onto a pre-existing microfibrillar matrix consisting of fibrillins and microfibrillar-associated glycoproteins (MAGPs), forming a network of elastin fibers that are responsible for vessel dilation and recoil [30]. A key histological characteristic of aortic aneurysms is elastin fragmentation and medial attenuation during aneurysmal expansion until the time of rupture [6]. Mutations of fibrillin-1 give rise to Marfan syndrome, which features aortic dilations [31], indicating that normal elastin and its associated microfibrils are critical for aortic integrity. Notably, biglycan was shown to interact with tropoelastin and MAGP-1 to form a ternary complex in vitro [32]. Over-expression of a glycosaminoglycan-deficient biglycan led to increased tropoelastin both in vitro and in vivo [33], further supporting a possible role of biglycan in regulating elastin and its associated microfibrils. However, over-expression of intact biglycan (with normal glycosaminoglycan chains) suppressed elastin [33], implying that the glycosaminoglycan chains play a role in biglycan regulation of elastin. In the current study, histological examination revealed prominent elastin degradation in aneurysms of biglycan-deficient mice. Thus, biglycan appears to play a role in normal elastin fiber formation and/or maintenance. Loss of biglycan in human aortae [26] and biglycan deficiency in murine aortae (Figure 2) may contribute to elastic fiber breakdown and the development of aortic aneurysms. Further studies are needed to define the mechanisms by which biglycan and its glycosaminoglycan chains affect vascular elastin content and integrity.

As outlined in the Response-to-retention hypothesis [16], atherosclerosis development is initiated by the subendothelial retention of atherogenic lipoproteins through their interactions with vascular proteoglycans. Studies in vitro have demonstrated that all arterial proteoglycans can bind apoB-lipoproteins. In human atherosclerosis, apoB is closely co-localized with biglycan [10, 11], and there is a relative increase in chondroitin sulfate and dermatan sulfate proteoglycans (including biglycan) and a relative decrease of heparan sulfate proteoglycans (including perlecan) in atherosclerotic lesions compared with adjacent non-atherosclerotic regions of the same artery [34, 35]. In previous studies, we demonstrated that angII infusions increased vascular biglycan content, which increased subsequent atherosclerosis development upon induction of hypercholesterolemia [9], and that this effect was mediated via angII induction of TGFß [13]. Furthermore, we recently demonstrated that prevention of angII-induced TGFß stimulation prevented angII induction of vascular biglycan and attenuated angII-induced atherosclerosis, without affecting the perlecan content of murine aortae [13]. Thus, we hypothesized that mice with biglycan deficiency would be protected from atherosclerosis development in response to angII. However, perlecan also co-localizes with apoB in murine arteries [13, 22], and mice with decreased or mutated perlecan had decreased atherosclerosis [23, 24]. The biglycan deficient mice had increased vascular perlecan content compared to biglycan wildtype mice. Thus, our findings that biglycan deficient and biglycan wildtype mice had similar development of angII-induced atherosclerosis was likely due to this increase in vascular perlecan.

In summary, this study demonstrates new roles for biglycan in vivo. Biglycan deficiency increases aortic aneurysm development and is not protective against the development of atherosclerosis. These vascular effects of biglycan deficiency are likely due to the up-regulation of vascular perlecan content, formation of loosely packed collagen fibers, and increased susceptibility of elastin fibers to angII-induced stress.

Highlights.

Biglycan deficient mice infused with angiotensinII develop thoracic aortic aneurysms

Biglycan deficiency does not alter atherosclerotic lesion area

Biglycan deficiency leads to loosely packed collagen fibers in the aorta

Biglycan deficient mice have increased vascular perlecan content

Acknowledgments

Funding support.

Research reported in this study was supported by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers R01-HL082772 and R01-HL082772-0351 (both to LRT) and R01-HL73898 (to KJW) and by the Swedish Heart-Lung Foundation (Hjärt-Lungfonden, to KJW). The contents of this report are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of these agencies. This work was previously presented in part at the Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology 2013 Scientific Sessions, Orlando, FL, April 2013.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: None

REFERENCES

- 1.Corsi A, et al. Phenotypic effects of biglycan deficiency are linked to collagen fibril abnormalities, are synergized by decorin deficiency, and mimic Ehlers-Danlos-like changes in bone and other connective tissues. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17(7):1180–9. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.7.1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ameye L, et al. Abnormal collagen fibrils in tendons of biglycan/fibromodulin-deficient mice lead to gait impairment, ectopic ossification, and osteoarthritis. FASEB J. 2002;16(7):673–80. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0848com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heegaard AM, et al. Biglycan deficiency causes spontaneous aortic dissection and rupture in mice. Circulation. 2007;115(21):2731–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.653980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pasquali-Ronchetti I, Baccarani-Contri M. Elastic fiber during development and aging. Microsc Res Tech. 1997;38(4):428–35. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(19970815)38:4<428::AID-JEMT10>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thom T, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2006 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2006;113(6):e85–151. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.171600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sakalihasan N, Limet R, Defawe OD. Abdominal aortic aneurysm. Lancet. 2005;365(9470):1577–89. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66459-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tamarina NA, et al. Proteoglycan gene expression is decreased in abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Surg Res. 1998;74(1):76–80. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1997.5201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Theocharis AD, Karamanos NK. Decreased biglycan expression and differential decorin localization in human abdominal aortic aneurysms. Atherosclerosis. 2002;165(2):221–30. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(02)00231-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang F, et al. Angiotensin II increases vascular proteoglycan content preceding and contributing to atherosclerosis development. J Lipid Res. 2008;49(3):521–30. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M700329-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakashima Y, et al. Early human atherosclerosis: accumulation of lipid and proteoglycans in intimal thickenings followed by macrophage infiltration. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27(5):1159–65. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.106.134080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O'Brien KD, et al. Comparison of apolipoprotein and proteoglycan deposits in human coronary atherosclerotic plaques: Co-localization of biglycan with apolipoproteins. Circulation. 1998;98(6):519–527. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.6.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thompson JC, et al. Increased atherosclerosis in mice with increased vascular biglycan content. Atherosclerosis. 2014;235(1):71–75. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.03.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tang T, et al. Prevention of TGFb induction attenuates angiotensinII-stimulated vascular biglycan and atherosclerosis in Ldlr−/− mice. J Lipid Res. 2013 doi: 10.1194/jlr.P040139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daugherty A, Manning MW, Cassis LA. Angiotensin II promotes atherosclerotic lesions and aneurysms in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2000;105(11):1605–12. doi: 10.1172/JCI7818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bruemmer D, et al. Relevance of angiotensin II-induced aortic pathologies in mice to human aortic aneurysms. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011;1245:7–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams KJ, Tabas I. The response-to-retention hypothesis of early atherogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1995;15(5):551–61. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.15.5.551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu T, et al. Targeted disruption of the biglycan gene leads to an osteoporosis-like phenotype in mice. Nat Genet. 1998;20(1):78–82. doi: 10.1038/1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tang T, et al. Decreased body fat, elevated plasma transforming growth factor-beta levels, and impaired BMP4-like signaling in biglycan-deficient mice. Connect Tissue Res. 2013;54(1):5–13. doi: 10.3109/03008207.2012.715700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coen M, et al. Altered collagen expression in jugular veins in multiple sclerosis. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2013;22(1):33–8. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Freudenberger T, et al. Proatherogenic effects of estradiol in a model of accelerated atherosclerosis in ovariectomized ApoE-deficient mice. Basic Res Cardiol. 2010;105(4):479–86. doi: 10.1007/s00395-010-0091-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tang T, et al. Decreased body fat, elevated plasma transforming growth factor-beta levels, and impaired BMP4-like signaling in biglycan-deficient mice. Connect Tissue Res. 2012 doi: 10.3109/03008207.2012.715700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kunjathoor VV, et al. Accumulation of biglycan and perlecan, but not versican, in lesions of murine models of atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22(3):462–8. doi: 10.1161/hq0302.105378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tran-Lundmark K, et al. Heparan sulfate in perlecan promotes mouse atherosclerosis: roles in lipid permeability, lipid retention, and smooth muscle cell proliferation. Circ Res. 2008;103(1):43–52. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.172833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vikramadithyan RK, et al. Atherosclerosis in perlecan heterozygous mice. J Lipid Res. 2004;45(10):1806–12. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M400019-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Westermann D, et al. Biglycan is required for adaptive remodeling after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2008;117(10):1269–76. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.714147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gomez D, et al. Syndromic and non-syndromic aneurysms of the human ascending aorta share activation of the Smad2 pathway. J Pathol. 2009;218(1):131–42. doi: 10.1002/path.2516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Majesky MW. Developmental basis of vascular smooth muscle diversity. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27(6):1248–58. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.141069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tromp G, et al. Novel genetic mechanisms for aortic aneurysms. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2010;12(4):259–66. doi: 10.1007/s11883-010-0111-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jacob MP. Extracellular matrix remodeling and matrix metalloproteinases in the vascular wall during aging and in pathological conditions. Biomed Pharmacother. 2003;57(5-6):195–202. doi: 10.1016/s0753-3322(03)00065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arteaga-Solis E, Gayraud B, Ramirez F. Elastic and collagenous networks in vascular diseases. Cell Struct Funct. 2000;25(2):69–72. doi: 10.1247/csf.25.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kainulainen K, et al. Mutations in the fibrillin gene responsible for dominant ectopia lentis and neonatal Marfan syndrome. Nat Genet. 1994;6(1):64–9. doi: 10.1038/ng0194-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reinboth B, et al. Molecular interactions of biglycan and decorin with elastic fiber components: biglycan forms a ternary complex with tropoelastin and microfibril-associated glycoprotein 1. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(6):3950–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109540200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hwang JY, et al. Retrovirally mediated overexpression of glycosaminoglycan-deficient biglycan in arterial smooth muscle cells induces tropoelastin synthesis and elastic fiber formation in vitro and in neointimae after vascular injury. Am J Pathol. 2008;173(6):1919–28. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cardoso L, Maurao PAS. Glycosaminoglycan fractions from human arteries presenting diverse susceptibilities to atherosclerosis have different binding affinities to plasma low density lipoprotein. Arterioscler. Thromb. 1994;14:115–124. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.14.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stevens RL, et al. The glycosaminoglycans of the human artery and their changes in atherosclerosis. J. Clin. Invest. 1976;58(2):470–481. doi: 10.1172/JCI108491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]