Abstract

Objective

Youths' ability to positively cope with negative emotions and their self-perceived friendship competence were examined as potential moderators of links between multiple aspects of romantic relationships and residualized increases in depressive symptoms from late adolescence into early adulthood.

Method

Participants included 184 teens (46% male; 42% non-white) assessed at ages 15-19 and 21, as well as a sub-sample of 62 romantic partners of participants assessed when teens were 18.

Results

Results of hierarchical linear regressions showed that positive coping served as a buffer against depressive symptoms for romantically involved adolescents and also for teens receiving more intense emotional support from their romantic partners, but not for youth whose relationship had ended and had not been replaced by a new relationship. Higher perceived friendship competence served as a buffer against depressive symptoms for youth enduring the dissolution and non-replacement of their romantic relationship.

Conclusions

Greater use of positive coping skills and higher perceived friendship competence may help protect adolescents from depressive symptoms in different types of romantic experiences.

Keywords: Romantic relationships, Adolescence, Depressive Symptoms, Emotion regulation, Friendships

Romantic involvement is a normative developmental occurrence in adolescence that typically culminates with the emergence of sustained dyadic romantic relationships (Collins, 2003). Initially conceptualized as relatively unimportant compared to adults' relationships, research has shown that adolescent romantic relationships are often long-term and bear significant resemblance to the features of adult romantic relationships (Collins, 2003; Levesque, 1993). It is only within the last two decades that researchers have considered the potential impact of romantic experiences on adolescents' functioning. During this time research has consistently documented links between different aspects of romantic relationships during adolescence and depressive symptoms (Compian, Gowen, & Hayward, 2004; Davila, Steinberg, Kachadourian, Cobb, & Fincham, 2004; Joyner & Udry, 2000; Quatman, Sampson, Robinson, & Watson, 2001; Stroud & Davila, 2008), suggesting that these relationships may confer a similar vulnerability to depressive symptoms for youth as has been observed in adult relationships (O'Leary, Christian, & Mendell, 1994; Weissman, 1987). Thus far, however, little research has sought to identify the conditions under which such associations may be more or less likely to occur for youth. As such, this study was designed to examine longitudinal associations between teens' romantic experiences and depressive symptoms. Moreover, it aimed to test the idea that teens' positive coping skills and positive perceptions of friendship competence would serve as protective factors against depressive symptoms for youth engaged in different romantic experiences.

One romantic experience for youth that has been associated with depressive symptoms is simply being involved in a romantic relationship. In their seminal study, Joyner and Udry (2000) found higher levels of depression for adolescent boys and girls who entered into romantic relationships during the time of the study as compared to those who did not become romantically-involved. This association between romantic involvement and depressive symptoms has since been replicated in other samples, though it remains poorly understood (e.g. Davila et al., 2004; Quatman et al., 2001). Unfortunately, the dissolution of a romantic relationship has also been associated with potential emotional costs. The breakup of a romantic relationship has been identified as a prospective risk factor for depression (Monroe, Rohde, Seeley, & Lewinsohn, 1999), which may be in part due to distorted interpretations of negative emotions associated with the event (Boelen & Reijntjes, 2009). One possible explanation that has been suggested for these associations is that both involvement in and the dissolution of romantic relationships may increase youths' vulnerability to depressive symptoms due to the novelty and difficulty of the emotional challenges youth face in managing these relationship events (Larson, Clore, & Wood, 1999).

To the extent that emotional processes within romantic relationships are indeed challenging for youth, another possible source of risk for depressive symptoms may be interactions in which there is a high level of emotionality expressed. Although such interactions could include conflict discussions, it is also possible that more intense discussions of emotions in other interaction contexts might contribute to negative outcomes. For example, though teens increasingly turn to romantic partners as sources of emotional support in late adolescence (Seiffge-Krenke, 2003), it is unclear how emotional support processes may play out in such relationships. Although the perception of support has been associated with positive outcomes within relationships (Sarason, Sarason, & Pierce, 1994), research from the adult literature has also consistently found that the actual receipt of support from others is often associated with depressed mood for the individual requesting support (Bolger, Zuckerman, & Kessler, 2006; Shrout, Herman, & Bolger, 2006). This may be because the support given calls further attention to the problem, may threaten one's self-esteem or feelings of competence, or is not delivered skillfully enough to have its intended effect (e.g., Shrout et al., 2006). However, research has yet to examine how the receipt of emotional support may play out in observable interactions between romantic partners during adolescence and whether or not it may predict youths' depressive symptoms, as shown in research examining these processes in adults' relationships.

From a developmental perspective, there are a few reasons to think that the aspects of romantic relationships noted above may be particularly challenging for adolescents and increase their risk for depressive symptoms. First, as previously suggested, the emotions experienced in romantic relationships are often unfamiliar to adolescents, complex, and powerful (Larson, Clore, & Wood, 1999). As such, teens may be more likely to distort or make misattributions about romantic feelings as compared to adults (Larson et al., 1999). Evidence also suggests that romantic relationship experiences are responsible for a substantial portion of fluctuation in teens' moods and contribute to a significant proportion of teens' negative mood states (Larson & Asmussen, 1991; Larson & Richards, 1994; Wilson-Shockley, 1995). Second, it is important to consider that psychosocial maturation increases steadily but slowly during adolescence, not reaching a peak until ages 26-30 (Steinberg et al., 2009). Though such maturity may partly develop in the context of increased experience in social relationships, it is also likely in part a reflection of improved coordination between areas of the brain that govern cognition and emotion (Steinberg, 2009). Such coordination may increasingly permit youth to access more metacognitive emotional coping strategies during difficult emotional experiences, such as the ability to positively cope with negative emotions by reframing distressing experiences into less negative and more balanced perspectives. Indeed, evidence suggests that the use of cognitively-based coping strategies appears to increase across development with age (Zimmer-Gembeck & Skinner, 2011). If the emotional challenges inherent in adolescent romantic relationships may be in part responsible for their associations with depressive symptoms, the likelihood of developing symptoms as a result of romantic experiences may depend on how well teens are able to cope with such emotional challenges. Thus, it may be that teens that have developed an increased ability to positively cope with negative emotions will be more likely to be buffered from depressive symptoms as compared to youth with less well-developed coping abilities.

In addition to the development of positive coping skills during adolescence, friendships also change to become increasing sources of intimacy and support for youth. Although parents are primary sources of support for youth during childhood, friends begin to equal parents in perceived availability of support during early adolescence and exceed them by age 18 (Bokhorst et al., 2010). Thus, friendships become significant sources of support for teens during a period of time in which they face a number of new challenges, including navigating dyadic romantic relationships. This may be particularly true when it comes to talking about such relationships; romantic relationships may be considered by teens to be outside of the purview of parents, or an uncomfortable topic to discuss with them (Buhrmester & Furman, 1987; Steinberg & Silk, 2002; Salisch, 2001). Supportive friendships have been associated with decreased depressive symptoms for youth (Feldman, Rubenstein, & Rubin, 1998; Nangle, Erdley, Newman, Mason, & Carpenter, 2003. Notably, simply perceiving support to be available from others – without necessarily receiving it – has the potential to reduce distress by increasing confidence that support is available if needed and reducing the level of threat perceived in difficult situations (Calvete & Connor-Smith, 2006). Additional research has also demonstrated the usefulness of assessing self-perceptions of social competence to attain support to predict adjustment. With regard to peer social relationships, previous work has shown that adolescents' self-rated perceptions of interpersonal competence are related to lower levels of depressive symptoms and also increased intimacy with friends (Buhrmester, 1990). Adolescents' self-perceived social acceptance has also been linked to peer ratings of adolescents as less socially withdrawn and more desirable companions (McElhaney et al., 2008). Believing that one is skilled at maintaining friendships and therefore has the support of friends available if needed may thus be another factor that buffers romantically-involved youth against depressive symptoms during times of emotional stress, and perhaps particularly if the relationship should end.

The present study utilized longitudinal, multi-method data obtained from adolescents and their romantic partners to examine whether youths' positive coping and self-perceived friendship competence would buffer against depressive symptoms in three different types of romantic experiences. Based on prior research, it was first hypothesized that romantic relationship involvement would predict residualized increases in depressive symptoms over time, but that greater positive coping skills and higher self-perceived competence in close friendships would buffer youth against such residualized increases in depressive symptoms. Second, it was similarly hypothesized that experiencing the non-continuity of a previously established relationship would predict residualized increases in depressive symptoms over time, and that greater positive coping skills and higher self-perceived competence in close friendships would buffer youth against such residualized increases in depressive symptoms. However, because it was thought that perceptions of friendship competence might be particularly important not only when youth are engaged in a romantic relationship but also when that relationship has been lost, this study sought to examine perceptions of friendship competence at both time points to determine the significance of such timing for predicting depressive symptoms. Finally, this study also aimed to examine whether or not receiving more intense emotional support from a romantic partner would predict a residualized increase in depressive symptoms, and, if so, whether such an association would be buffered by positive coping and self-perceived friendship competence. These hypotheses were examined within a diverse community sample of male and female adolescents.

Method

Participants and Procedure

This sample is drawn from a longitudinal study of adolescent social development. Participants included 184 adolescents (86 male and 98 female) and a sub-sample of 62 target adolescents and their romantic partners. Participants were interviewed when target adolescents were approximately 15 (age: M=15.20, SD=.81), 16 (age: M=16.33, SD=.89), 17 (age: M=17.31, SD=.88), 18 (age: M=18.29, SD=1.27), 19 (age: M=19.67, SD=1.07), and 21 (age: M=21.65, SD=.96) years old. The sample was racially/ethnically and socioeconomically diverse: 107 adolescents identified themselves as Caucasian, 53 as African American, 2 as Hispanic/Latino, 2 as Asian American, 1 as American Indian, 15 as mixed ethnicity, and 4 as part of an “other” minority group. Parents of target adolescents reported a median family income in the $40,000-$59,999 range (M=$43,618, SD=$22,420).

Target adolescents were initially recruited from a single public middle school drawing from suburban and urban populations in the Southeastern United States. Students were recruited via an initial mailing to all parents of students in the 7th and 8th grades of the middle school that gave them the opportunity to opt out of any further contact with the study (N = 298). Only 2% of parents opted out of such contact. Of all families subsequently contacted by phone, 63% agreed to participate and had an adolescent who was able to come in with both a parent and a close friend. Siblings of target adolescents and students already participating as a target adolescent's close friend were ineligible for participation. This sample appeared generally comparable to the overall population of the school in terms of racial/ethnic composition (42% non-white in sample vs. ∼ 40% non-white in school) and socio-economic status (mean household income = $43,618 in sample vs. $48,000 for community at large).

At participant ages 15-17, 19, and 21, adolescents participated in one individual visit. At participant age 18, adolescents first came in for an individual visit. Adolescents were asked to return for a second visit with their romantic partner if they endorsed being involved in a significant romantic relationship (i.e. two months or longer) at visit one. Of the original 184 adolescents who participated at visit one, 70 endorsed being in a romantic relationship of at least two months, and 62 adolescents (35 females; 35 self-identified as Caucasian, 20 as African-American, 6 as of mixed race/other ethnicity; median family income in the $40,000-59,999 range) and their romantic partners ultimately participated at visit two. At the second visit, teens participated in a 6-minute interaction task with their romantic partner, during which they asked their partner for help with a “problem they were having that they could use some support or advice about.” At participant age 18, participants' romantic partners were approximately 19 years old (M=19.23, SD=3.30). The average duration of adolescents' relationships with their romantic partners was approximately 14 months (M=14.40, SD=13.31). Same-gender relationships were not excluded from the study; however, no same-gender relationships were reported at the time of data collection. Participants who were in a romantic relationship of at least two months duration at age 18 relative to those who were not were more likely to be female (t (183) = -2.24, p < .05) and more likely to be a romantic relationship of at least two months duration at age 19 (t (118) = -3.47, p < .001). All interviews took place in private offices within a university academic building. Participating adolescents provided informed assent, and their parents provided informed consent until adolescents were 18 years of age, at which point adolescents provided informed consent. The same assent/consent procedures were used for romantic partners. Adolescents and romantic partners were paid for their participation.

Attrition Analyses

Attrition analyses indicated that youth who were not followed between age 15 and age 21 (n = 23) did not differ from youth followed at both time points on any of the study's variables. These analyses suggest that the relatively low attrition observed was not likely to have biased any of the findings reported. Participants whose romantic partners participated in the observed interaction task at age 18 relative to those whose partners did not participate did not differ on any of the variables of interest to this study. To best address any potential biases due to attrition in longitudinal analyses, occasional missing data at interim time points was handled using Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML). FIML procedures have been found to be superior in terms of showing less bias in parameter estimates and less sampling variability when all available data are used for longitudinal analyses (vs. listwise deletion of missing data; Enders, 2001). Thus, Ns for regression equations reflect the entire sample or subsample available for analysis: a) the full sample of 184 adolescents was utilized for analyses examining initial romantic involvement, b) a subsample of 62 adolescents who were observed with their romantic partner was used for analyses examining the intensity of emotional support received from romantic partners, and, c) a subsample of 70 adolescents initially reporting involvement in a romantic relationship of at least two months duration was used for analyses examining relationship non-continuity.

Measures

Romantic relationship involvement

Romantic relationship involvement was assessed by asking participants whether they were currently involved in a romantic relationship of at least two months duration at age 18 (n = 70 in a relationship).

Non-continuity of romantic relationship

The non-continuity of adolescents' romantic relationships from age 18 to 19 was assessed by asking teens who reported being in a romantic relationship of at least two months duration at age 18 (n = 70) to answer “yes” (n = 44) or “no” (n = 26) to whether or not they were currently dating someone for at least two months at age 19.

Intensity of emotional support from teen and romantic partner

At age 18 participants were invited to ask their romantic partner for help with a “problem they were having that they could use some support or advice about.” These interactions were coded using the Supportive Behavior Coding System (Allen et al., 2001), which was based on several related coding systems (Crowell et al., 1998; Haynes & Fainsilber Katz, 1998; Julien, Markman, Lindahl, Van Widenfelt, & Herskovitz, 1997). Teens' calls for emotional support were assessed by rating the intensity and persistence of the emotional distress that the teen conveyed to their romantic partner. Behaviors that reflected the intensity of emotional support given by romantic partners consisted of the degree to which the romantic partner continued to draw out, discuss, and empathize with the teen's emotions during the discussion. Scores on these individual scales were rated on a 0 to 4 continuum, with higher scores indicating more intense levels of calls for emotional support and emotional support given. Each interaction was coded as an average of scores obtained by two trained coders blind to the rest of the data from the study and study purpose. Interrater reliability was calculated using intraclass coefficients, and was in the excellent range (ICCs=.82 for both scales; Cicchetti & Sparrow, 1981).

Positive coping

Adolescents' ability to positively cope with negative emotions was assessed using the emotional repair scale from the Trait Meta-Mood Scale (Salovey, Mayer, Goldman, Palfai, 1995). This self-report measure is designed to assess relatively stable individual differences in people's ability to think positively when faced with negative experiences, and has demonstrated good reliability and validity (Extremera & Fernández-Berrocal, 2006; Fernández-Berrocal et al., 2006; Mavroveli, Petrides, Rieffe, & Bakker, 2007; Salovey, Mayer, Goldman, Palfai, 1995). This scale has demonstrated significant links with lower levels of perceived stress and higher levels of life satisfaction among a large sample of adolescents, even after controlling for dispositional variables (Extremera, Durán, & Rey, 2007) The six items on the emotional repair scale are rated from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) and summed to create an overall emotional repair scale. Emotional repair was assessed at teen ages 15 (M=22.29, SD=4.37), 16 (M=22.33, SD=4.77), and 17 (M=22.68, SD=4.73) and aggregated into a composite variable by taking the mean score across the 3 time points to capture a more stable picture of adolescents' ability to positively cope with negative emotions during adolescence. Correlations between emotional repair assessed at ages 15, 16, and 17 ranged from r = .56 to .66. The emotional repair composite scale showed good internal consistency in the current study (Cronbach's α = .72, .79, .79 at teen ages 15, 16, and 17, respectively.)

Perceived close friendship competence

Adolescents self-reported on their level of perceived competence in close friendships at ages 18 and 19 using the friendship competence subscale of the Harter Self-Perception Profile for Adolescents (Harter, 1988). The format for this measure asks teens to choose between two contrasting descriptors and then rate the extent to which their choice is sort of true or really true about themselves. Item responses are scored on a 4-point scale and then summed, with higher scores indicating higher levels of self-rated close friendship competence. The close friendship scale includes five items. The friendship competence subscale showed good internal consistency in the current study at ages 18 and 19 (Cronbach's α = .83 and .89, respectively).

Depressive symptoms

At ages 18 and 21, adolescents completed the Child Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs & Beck, 1977) and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck & Steer, 1987), respectively. The CDI is a 27-item measure designed to assess depressive symptoms in children and adolescents; the BDI is a 21-item inventory designed to assess depressive symptoms in adults. On both measures, each item is rated on a 0 to 3 scale, yielding one total depression score with higher scores indicating more severe depressive symptoms. These measures of depressive symptoms showed excellent internal consistency at participant ages 18 and 21 (Cronbach's α =.83 and .88, respectively).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Univariate statistics

Means and standard deviations for all primary variables are presented in Table 1. Measures of depression were standardized for all analyses. Initial analyses also examined the role of gender and family income on teen depressive symptoms, and neither variable was related to depression at age 18 or at age 21. Both variables, however, were retained as covariates in all regression analyses to account for any possible effects that may not have reached conventional levels of statistical significance.

Table 1. Univariate Statistics and Intercorrelations Among Study Variables.

| Mean (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Income | $43,618 ($22,420) | - | |||||||||

| 2. Gender | 46% male | -.12 | - | ||||||||

| 3. Depressive Symptoms (18) | 5.41 (5.12) | -.05 | .05 | - | |||||||

| 4. Depressive Symptoms (21) | 5.48 (6.16) | .02 | .03 | .48*** | - | ||||||

| 5. Romantic Involvement (18) | 38% in a relationship | -.09 | .16* | -.01 | .11 | - | |||||

| 6. Non-continuity of Romantic Relationship (19) | 37% ceased | -.02 | -.17 | -.04 | -.09 | -.30*** | - | ||||

| 7. Teen Call for Support from Romantic Partner (18) | .91 (1.02) | .23 | .14 | .05 | .22 | -.05 | .19 | - | |||

| 8. Intensity of Support from Romantic Partner (18) | .67 (.85) | .26* | .11 | -.01 | .12 | .17 | .11 | .73*** | - | ||

| 9. Positive Coping (15-17) | 22.37 (3.96) | .00 | .14* | -.30*** | -.25*** | .14 | -.08 | .09 | -.05 | - | |

| 10. Close Friendship Competence (18) | 16.28 (3.14) | .15* | .13 | -.29*** | -.13 | .03 | -.04 | .01 | -.16 | .26*** | - |

| 11. Close Friendship Competence (19) | 17.53 (2.54) | .11 | .15 | -.34*** | -.24** | .01 | -.17 | -.08 | .17 | .26*** | .59*** |

Note. Gender coded as: 1 = males, 2 = females; Romantic involvement coded as: 0 = Not in a romantic relationship, 1 = In a romantic relationship of at least two months; Non-continuity of romantic relationship coded as: 0 = Continuity, 1 = Non-continuity. N = 184 for constructs 1-5, 9-11; n = 62 for constructs 7-8; n = 70 for construct 6.

p ≤ .05,

p ≤ .01,

p ≤ .001.

Correlational analyses

For descriptive purposes, simple univariate (or point biserial where relevant) correlations were examined between all key variables of interest using pairwise deletion methods and are presented in Table 1.

Primary Analyses

Hypothesis 1

Higher levels of positive coping and self-perceived friendship competence will buffer romantically involved youth against residualized increases in depressive symptoms.

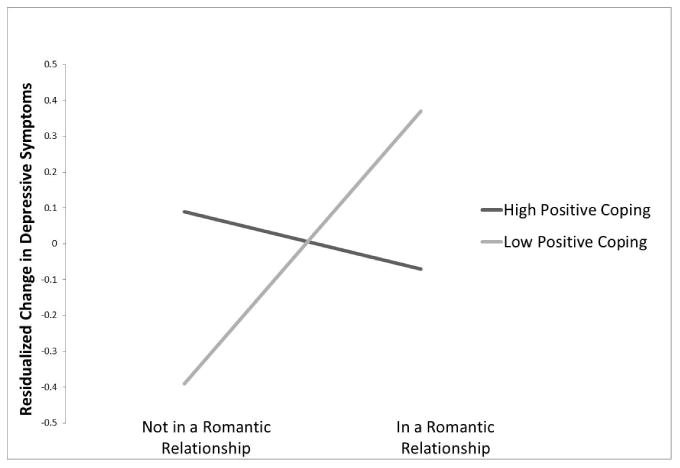

A series of hierarchical linear regressions were performed to examine predictions to depressive symptoms at age 21. Gender and income were entered together first in all models. Second, depressive symptoms at age 18 was entered. Third, romantic relationship involvement (age 18) was entered simultaneously with positive coping (ages 15-17) and self-perceived close friendship competence (age 18). Finally, interaction terms between positive coping and relationship involvement and perceived close friendship competence and relationship involvement were entered together into the model (see Table 2). Interaction terms for all analyses were created by standardizing the continuous predictor variables (M=0, SD=1) and multiplying them with the binary relationship involvement variable. The selected analytic approach of predicting the future level of a variable, such as depressive symptoms, while accounting for predictions from initial levels, yields one marker of residualized change in that variable by allowing assessment of predictors of future depressive symptoms while accounting for initial levels (Cohen & Cohen, 1983). In addition, covarying baseline levels of future behavior eliminates the spurious effect whereby observed predictions are simply a result of cross-sectional associations among variables that are stable over time. Romantic involvement at age 18 predicted a residualized increase in depressive symptoms at teen age 21, whereas higher levels of positive coping at ages 15-17 predicted a residualized decrease in symptoms. However, these main effects were subsumed by a significant interaction between teen romantic relationship involvement at age 18 and teen positive coping at ages 15-17 (see Figure 1). The interaction shows that romantically involved youth with higher positive coping skills reported lower levels of residualized depressive symptoms as compared to youth with lower positive coping skills. With regard to simple effects, romantic relationship involvement did not predict a residualized increase in teens' depressive symptoms at age 21 for youth with higher levels of positive coping (β = -.03, ns), but did predict a residualized increase in depressive symptoms for teens with lower levels of positive coping (β = .33, p = .001). The interaction between romantic relationship involvement and close friendship competence at age 18 was not significant.

Table 2.

Romantic Involvement, Positive Coping, and Perceived Close Friendship Competence as Predictors of Residualized Change in Youths' Depressive Symptoms.

| Depressive Symptoms | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| β entry | Change R2 | Total R2 | |

|

| |||

| Step 1. | |||

| Family Income | .04 | ||

| Gender | .04 | .00 | .00 |

|

| |||

| Step 2. | |||

| Depressive Symptoms (18) | .48*** | .23*** | .23*** |

|

| |||

| Step 3. | |||

| Romantic Involvement (18) | .14* | ||

| Positive Coping (15-17) | -.15* | ||

| Close Friendship Competence (18) | .07 | .03 | .26*** |

|

| |||

| Step 4. | |||

| Romantic Involvement (18) X Positive Coping (15-17) | -.23** | ||

| Relationship Status (18) X Close Friendship Competence (18) | .06 | .03* | .29*** |

Note. N = 184. Gender coded as: 1 = males, 2 = females. Romantic status coded as: 0 = Not in a relationship, 1 = In a relationship of at least two months.

p ≤ .05,

p ≤ .01,

p ≤ .001.

Figure 1.

Interaction between romantic involvement and positive coping predicting residualized change in depressive symptoms (all measures standardized). High and low values of constructs represent scores 1 SD above and below the mean, respectively.

Hypothesis 2

Higher levels of positive coping and self-perceived friendship competence will buffer youth who experience the non-continuity of a romantic relationship against residualized increases in depressive symptoms.

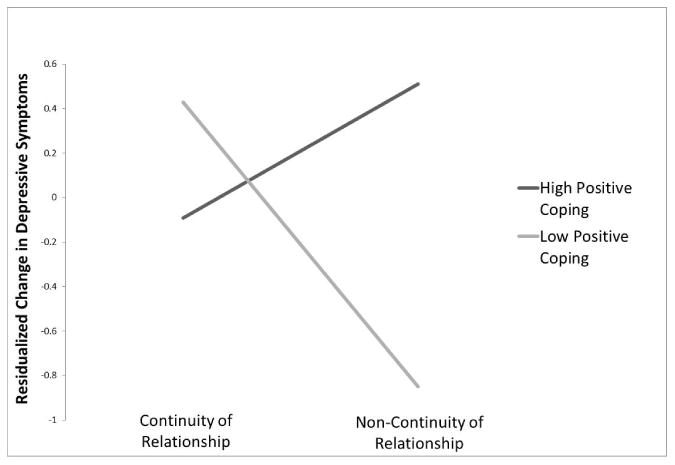

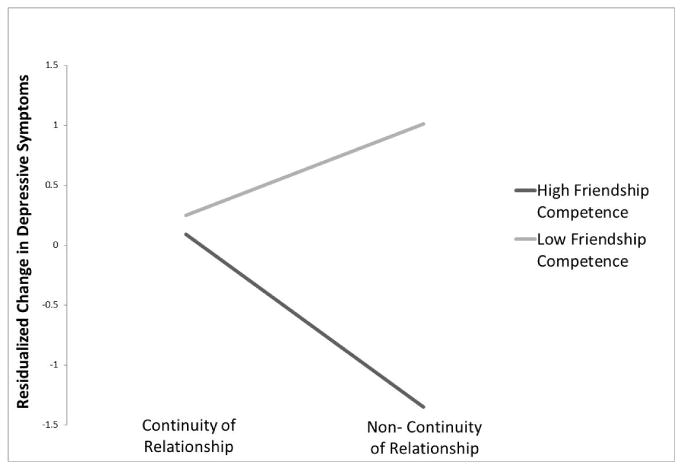

Analyses next examined romantic relationship non-continuity from ages 18-19, levels of positive coping at ages 15-17, self-perceived close friendship competence at ages 18 and 19, and interactions between relationship non-continuity and positive coping and perceived close friendship competence, after accounting for gender, income, and depressive symptoms at age 18, as predictors of depressive symptoms at age 21. Separate analyses were conducted with self-perceived friendship competence at age 18 and at age 19 to examine the significance of the timing of this construct for predicting depressive symptoms in the context of relationship non-continuity. The analysis conducted with perceived friendship competence at age 18 did not indicate a significant main effect (β = -.29, ns) of friendship competence nor an interaction effect with relationship non-continuity (β = -.31, ns). Table 3 shows the analysis including friendship competence at age 19. In this analysis, higher levels of positive coping at ages 15-17 predicted a residualized decrease in depressive symptoms at age 21. However, this result was subsumed by an interaction between relationship non-continuity from ages 18 to 19 and positive coping at ages 15-17 which significantly predicted depressive symptoms at age 21 (see Figure 2). The interaction shows that youth experiencing relationship non-continuity with higher positive coping skills reported higher levels of residualized depressive symptoms as compared to youth with lower positive coping skills. With regard to simple effects, romantic relationship non-continuity did not predicted a residualized change in teens' depressive symptoms at age 21 for youth with higher positive coping (β = .13, ns), but did predict a residualized decrease in depressive symptoms for teens with lower levels of positive coping (β = -.46, p = .01). The interaction between relationship non-continuity from ages 18 to 19 and close friendship competence at age 19 also significantly predicted depressive symptoms at age 21 (see Figure 3). The interaction shows that youth experiencing relationship non-continuity with higher perceived friendship competence reported lower levels of residualized depressive symptoms as compared to youth with lower positive coping skills. With regard to simple effects, relationship non-continuity predicted a residualized decrease in teens' depressive symptoms at age 21 for youth with higher self-perceived friendship competence (β = -.58, p < .01), but did not predict any residualized change in depressive symptoms for teens with lower levels of self-perceived friendship competence (β = .24, ns).

Table 3.

Relationship Non-Continuity, Positive Coping, and Perceived Close Friendship Competence as Predictors of Residualized Change in Youths' Depressive Symptoms.

| Depressive Symptoms | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| β entry | Change R2 | Total R2 | |

|

| |||

| Step 1. | |||

| Family Income | .01 | ||

| Gender | .14 | .02 | .02 |

|

| |||

| Step 2. | |||

| Depressive Symptoms (18) | .47*** | .22*** | .24** |

|

| |||

| Step 3. | |||

| Relationship Non-Continuity (19) | -.09 | ||

| Positive Coping (15-17) | -.31*** | ||

| Close Friendship Competence (19) | -.06 | .10* | .34*** |

|

| |||

| Step 4. | |||

| Relationship Non-Continuity (19) X Positive Coping (15-17) | .47* | ||

| Relationship Non-Continuity (19) X Close Friendship Competence (19) | -.55** | .08* | .42*** |

Note. n = 70. Gender coded as: 1 = males, 2 = females. Romantic relationship non-continuity coded as: 0 = Continuity of relationship, 1 = Non-continuity of relationship.

p ≤ .05,

p ≤ .01,

p ≤ .001.

Figure 2.

Interaction between romantic relationship non-continuity and positive coping predicting residualized change in depressive symptoms (all measures standardized). High and low values of constructs represent scores 1 SD above and below the mean, respectively.

Figure 3.

Interaction between romantic relationship non-continuity and perceived close friendship competence predicting residualized change in depressive symptoms (all measures standardized). High and low values of constructs represent scores 1 SD above and below the mean, respectively.

Hypothesis 3

Higher levels of positive coping and self-perceived friendship competence will buffer youth who receive more intense emotional support from their romantic partners against residualized increases in depressive symptoms.

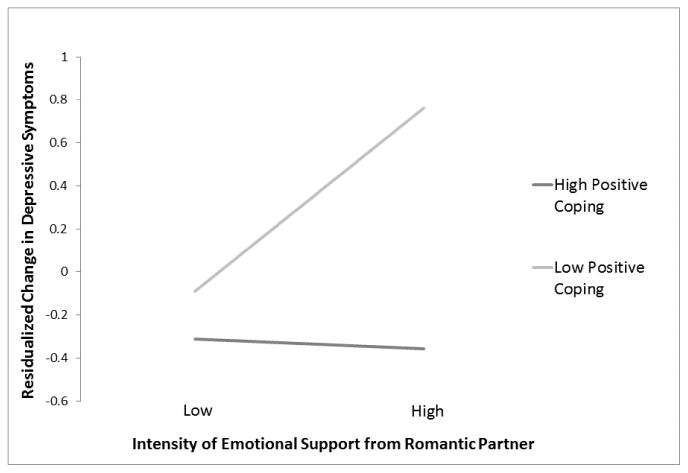

We next examined predictions to depressive symptoms at age 21 among a sub-sample of 62 adolescents who were in romantic relationships and who participated in an observed interaction task with their romantic partner at age 18. Intensity of emotional support received from romantic partners at age 18, level of positive coping at ages 15-17, level of self-perceived close friendship competence at age 18, and interactions between intensity of partner emotional support and the two other predictor variables were all examined as predictors of residualized change in depressive symptoms over time, after accounting for gender, income, and depressive symptoms at age 18, and teens' own calls for emotional support at age 18 (see Table 4). Higher levels of positive coping at ages 15-17 predicted a residualized decrease in depressive symptoms at age 21. However, there was a significant interaction between the intensity of partner emotional support given at age 18 and the level of teen positive coping at ages 15-17, as shown in Figure 4. The interaction shows that youth who received more intense emotional support from their romantic partners with higher positive coping skills reported lower levels of residualized depressive symptoms as compared to youth with lower positive coping skills. With regard to simple effects, more intense partner emotional support did not predict a residualized change in teens' depressive symptoms at age 21 for youth with higher levels of positive coping (β = -.11, ns), and did predict a residualized change in depressive symptoms for teens with lower levels of positive coping (β = .27, .ns). The interaction between intensity of emotional support and close friendship competence at age 18 was not significant. Post-hoc analyses examined interactions between teens' call for emotional support and positive coping (β = -13, ns) and perceived friendship competence (β = -12, ns), respectively; both interactions were not significant.

Table 4.

Intensity of Support from Romantic Partner, Positive Coping, and Perceived Close Friendship Competence as Predictors of Residualized Change in Youths' Depressive Symptoms.

| Depressive Symptoms | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| β entry | Change R2 | Total R2 | |

|

| |||

| Step 1. | |||

| Family Income | .06 | ||

| Gender | .05 | .01 | .01 |

|

| |||

| Step 2. | |||

| Depressive Symptoms (18) | .49*** | .23*** | .24** |

|

| |||

| Step 3. | |||

| Teen Call for Support (18) | .18 | ||

| Intensity of RP Support (18) | .06 | ||

| Positive Coping (15-17) | -.37*** | ||

| Close Friendship Competence (18) | .18 | .17** | .41*** |

|

| |||

| Step 4. | |||

| Intensity of RP Support (18) X Positive Coping (15-17) | -.22** | ||

| Intensity of RP Support (18) X Close Friendship Competence (18) | .00 | .05 | .46*** |

Note. n = 62. Gender coded as: 1 = males, 2 = females.

p ≤ .05,

p ≤ .01,

p ≤ .001.

Figure 4.

Interaction between intensity of emotional support from romantic partners and positive coping predicting residualized change in depressive symptoms (all measures standardized). High and low values of constructs represent scores 1 SD above and below the mean, respectively.

Discussion

From multiple perspectives, results of this study suggest that positive coping and self-perceived friendship competence may protect youth from depressive symptoms in the context of different romantic experiences. Three aspects of romantic relationships assessed at ages 18-19 were examined – the presence of a relationship of at least two months, the non-continuity of this relationship, and the intensity of romantic partners' emotional support to teens' problems – and, with one exception, results indicated that higher levels of positive coping or perceived friendship competence buffered against youths' depressive symptoms at age 21 as compared to lower levels of these constructs. Each of these findings and their limitations are discussed below.

Although this study found a direct link between romantic involvement in adolescence and higher levels of future depressive symptoms as documented in previous studies (Compian et al., 2004; Davila et al., 2004; Joyner & Udry, 2000; Quatman et al., 2001; Stroud & Davila, 2008), this result was subsumed by an interaction showing that the association between romantic involvement and depressive symptoms was dependent on teens' abilities to think positively when faced with negative experiences. Higher levels of positive coping at teen ages 15-17 buffered romantically involved teens against residualized increases in depressive symptoms. Notably, this result was found among a sample of late adolescent boys and girls, extending previous research in this area that has focused primarily on early adolescents, and mostly on girls. Research has shown that a substantial proportion of adolescents' daily stressors are related to interpersonal concerns, including their romantic relationships (Nieder & Seiffge-Krenke, 2001; Seiffge-Krenke, Aunola, & Nurmi, 2009). Though adolescents' ability to actively and cognitively cope with such stressors increases with age, teens are unfortunately less likely to use these types of coping strategies when faced with romantic relationship stressors as compared to stress in other areas of their lives (Seiffge-Krenke et al., 2009). However, when adolescents are able to positively cope with negative experiences, they report fewer symptoms of depression and anxiety as well as greater social functioning and higher self-esteem (Extremera & Fernández-Berrocal, 2006; Fernández-Berrocal, Alcaide, Extremera, & Pizzaro, 2006; Mavroveli et al., 2007). Thus, the present study's finding suggests that positive coping may have a similar positive effect of mitigating negative outcomes in the context of romantic involvement for adolescents who are able to successfully use it. Unexpectedly, lower levels of positive coping appeared to be associated with a relative decrease in depressive symptoms for romantically uninvolved youth. To the extent that both romantic involvement and use of positive coping skills are markers of stress, it is possible that youth who are not engaged in a romantic relationship have little need to engage in positive coping. Indeed, there is some evidence to suggest that positive coping is more likely to occur during times of greater, as compared to lessor, stress (Fabes & Eisenberg, 1997).

Inconsistent with hypotheses, however, findings suggested that youth whose known romantic relationship at age 18 had been discontinued and not replaced with another relationship at age 19 were buffered against a residualized increase in depressive symptoms when reporting lower (and not higher) levels of positive coping skills. One possible explanation for this finding may be related to the nature of the relationship non-continuity variable in the study. The measure of relationship non-continuity did not ascertain the reasons why relationships ended, who ended them, or when they were ended. Such variables have been shown to predict a significant amount of variance in depression scores when assessing the relationship between break-ups and depressive symptoms (Boelen & Reijntjes, 2009; Perilloux & Buss, 2008). As such, it is difficult to speculate to what extent negative emotions may have been experienced as a result of the endings of these relationships, and therefore how useful positive coping skills would be in such situations. As previously suggested, it is possible that positive coping may be a more helpful buffer against depressive symptoms for youth who are romantically involved, since the emotional stresses of involvement may be greater than those of non-involvement. At least this may be the case if non-involvement is not a result of a recent and emotionally-painful breakup. Further research that examines positive coping as moderator of more specific types of relationships non-continuity would be valuable for addressing these questions.

This study also found that that higher self-perceived friendship competence at age 19 buffered youth with non-continuous relationships against depressive symptoms. This result may be understood in the context of previous research examining breakups of romantic relationships in undergraduate students (Boelen & Reijntjes, 2009). These researchers noted that nearly half of these undergraduates were dating someone new at the time of the study, and that compared to individuals who were dating someone new, those who were still single had significantly higher levels of depression and anxiety. Although this study did not find a similar main effect of relationship non-continuity, the interaction speaks to the potential buffering effect that positive perceptions of an alternative relationship can have when a romantic partner is lost (Eshbaugh, 2010). Tashiro and Frazier (2003) also found that dating someone new was associated with less reported distress among a sample of youth who had previously broken up with their romantic partners, providing additional support for the idea that greater vulnerability to depressive symptoms may be conferred when a previous relationship has not been replaced by new one. Thus, it may be that youth who believe they are skilled at maintaining friendships are comforted by such knowledge in the event of a break up and its aftermath, believing that they will be able to find support from friends if they need it, even after a romantic partner is lost. It may also be the case that self-perceived friendship competence is correlated with other measures of friendships, such as friend network size or quality of friendships, and that such variables may also explain the associations found.

Results from this study also suggest that other aspects of romantic experiences may predict a vulnerability to depressive symptoms that may be buffered by positive coping. Adolescents who received more emotionally intense support from their romantic partners were protected against residualized increases in depressive symptoms when they reported a greater ability to positive cope with negative emotions. Although the provision of support from peers has mostly been associated with positive outcomes in the adolescent developmental literature (Feldman et al., 1998; Nangle et al., 2003), research in the adult literature suggests that support from relationship partners may also have negative effects (Bolger et al., 2006; Shrout et al., 2006). It has been suggested that direct support given by partners may simply call further attention to problems, unintentionally creating more emotional distress for youth (Shrout et al., 2006). Interestingly, research has suggested that support from relationship partners may be most effective when it is not actually explicitly noticed by the individual in distress (Bolger & Amarel, 2007; Bolger, Zuckerman, & Kessler, 2000). Simulation studies have supported the idea that partner support may exacerbate emotional distress by showing that the association between support and negative outcomes is unlikely to be driven by reverse causality processes in which distress leads to increased support or by an adverse third event that increases both support and distress (Seidman, Shrout, & Bolger, 2006). Notably, the buffering effect of self-perceived friendship competence against depressive symptoms was significant over and above teens' calls for emotional support and their own self-reported levels of depression symptoms at age 18, which may be viewed as two independent measures of teen distress, suggesting that this finding may not simply be explained by teen stress. Nevertheless, this study cannot rule out the possibility of alternative explanations for this finding, including the possibility that adolescents who engage in high levels of emotional support seeking may differ from those who do not on important constructs such as their level of stress (perhaps as assessed in another domain), the emotional intensity of the problem they chose to discuss, or whether they chose to seek emotional vs. instrumental support, all of which may also be associated with depressive symptoms. If replicated, this finding suggests that the capacity to cope successfully with negative emotions may be critical for youth to be able to adaptively integrate emotional support from a romantic partner into their own emotional experience. In support of this possibility, research has found that young adults are less likely to experience high levels of negative emotional arousal under intense stress when they are emotionally well regulated (Fabes & Eisenberg, 1997). Thus, for youth who are unprepared developmentally to cope with negative emotions, highly emotional experiences may indeed feel overwhelming. Additional support for this idea comes from research finding that romantically involved youth with a preoccupied attachment style are more likely to exhibit depressive symptoms as compared to less preoccupied youth (Davila et al. 2004). A preoccupied attachment style has been associated with experiencing ambivalent feelings of happiness, love, anxiety, and fear in response to positivity within close relationships (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2005), suggesting that some youth may interpret even positive behavior as emotionally unsettling if they do not possess the emotional skills to interpret it appropriately.

Although this study helps to identify important factors moderating the link between adolescents' involvement in romantic relationships and depressive symptoms, there are several limitations to keep in mind. First, although we attempted to examine meaningful adolescent romantic relationships by studying only relationships of at least two months duration, it should be noted that adolescents vary tremendously in their definitions of romantic relationships and that we cannot be certain that all relationships were similarly defined by teens. Additionally, although romantic partners' intensity of emotional support (and teens' calls for emotional support) was assessed via observational methods, the measures used to assess adolescents' abilities to positively cope with negative emotions, their perceived competence in close friendships, and their depressive symptoms were self-report. Although the use of observational measures means that all findings could not be a result of shared method variance among self-reports (a limit in prior research), it does not rule out the possibility that positive coping, perceived friendship competence, and depressive symptoms may all be markers of underlying distress. Future studies would benefit from controlling for general levels of stress when examining associations between romantic experiences and depressive symptoms to account for this possibility. It is also unclear as to whether difficulties with intense expressions of emotional support given might reflect a broader pattern of teens' struggles to manage emotions in multiple interactional contexts, such as with friends or parents. Examining these processes in alternative interaction and relationship contexts would help to clarify whether the effects found are specific to romantic relationships or extend to multiple domains of relational functioning.

It is also important to note that our assessment of relationship non-continuity does not necessarily refer to permanent ending of relationships. Moreover, we cannot be certain that adolescents who reported a significant relationship of at least two months at the follow-up time point did not also endure a break-up, or even multiple break-ups, during the interim period. Thus, these data primarily speak to the context of having had a significant romantic relationship at one point, and then not having one at a future time point. Future research might specifically explore the distinction between relationship dissolution and the potential stress of moving from a previous relationship to a new one. This study also does not directly address the possibility that depressed youth may be more likely than non-depressed youth to initially seek out romantic relationships, though in this study romantic involvement did not demonstrate a significant correlation with depressive symptoms concurrently at age 18. Finally, because depressive symptoms were measured on different scales, it was not possible to determine whether there was an overall change in depressive symptoms in the sample over time. Nonetheless, we were able to examine residualized change in depressive symptoms (relative to other young people in the sample) by assessing symptoms at 21 after accounting for symptom levels at 18.

These findings, if replicated and confirmed by further research, nevertheless have significant potential implications for parents, educators, and clinicians. Because parents typically have the benefit of experience and perspective from their own lives, they may regard romantic relationships during adolescence as fleeting and perhaps unimportant in the long-term, and may thus underestimate the importance of these relationships to teens' well-being. Educational programs for parents of teens and pre-teens would benefit from including information about how teens view these relationships and their effects on teens' moods. Additionally, it seems warranted to teach parents how to appropriately engage with teens about their romantic feelings and how to help them cope with these feelings, as well as to encourage teens to maintain friendships during the course of romantic relationships. Similarly, educators charged with teaching health-related curricula at the middle school and high school levels might consider integrating discussion about coping strategies into their classes. Such classes provide excellent opportunities for teens to gain exposure to emotional calming, self-soothing, and problem solving techniques that will help them both in their relationships and in other important areas of their lives. Finally, this research suggests that clinicians might be wise to consistently assess teens' romantic status and the role that experiences in such relationships may be causing or maintaining problems.

Acknowledgments

This study and its write-up were supported by grants from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Institute of Mental Health (9R01 HD058305-11A1 & R01-MH58066).

References

- Allen JP, Hall FD, Insabella GM, Land DJ, Marsh PA, Porter MR. Supportive behavior coding system. Charlottesville: University of Virginia; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA. Beck Depression Inventory Manual. New York: Psychological Corporation; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, Ameral D. Effects of social support vulnerability on adjustment to stress: Experimental evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;92:458–475. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.3.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, Zuckerman A, Kessler RC. Invisible support and adjustment to stress. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:953–961. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.6.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boelen PA, Reijntjes A. Negative cognitions in emotional problems following romantic relationship break-ups. Stress and Health. 2009;25:11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Bokhorst CL, Sumter SR, Westenberg PM. Social support from parents, friends, classmates, and teachers in children and adolescents aged 9 to 18 years: Who is perceived as most supportive? Social Development. 2010;19:417–426. [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester D. Intimacy of friendship, interpersonal competence, and adjustment during preadolescence and adolescence. Child Development. 1990;61:1101–1111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester D, Furman W. The development of companionship and intimacy. Child Development. 1987;58:1101–1113. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1987.tb01444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvete E, Connor-Smith JK. Perceived social support, coping, and symptoms of distress in American and Spanish students. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping. 2006;19:47–65. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti DV, Sparrow SA. Developing criteria for establishing interrater reliability of specific items: Applications to assessment of adaptive behavior. American Journal of Mental Deficiency. 1981;86:127–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA. More than myth: The developmental significance of romantic relationships during adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2003;13:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Compian L, Gowen LK, Hayward C. Peripubertal girls' romantic and platonic involvement with boys: Associations with body image and depression symptoms. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2004;14:23–47. [Google Scholar]

- Crowell J, Pan H, Goa Y, Treboux D, O'Connor E, Waters EB. The secure base scoring system for adults Version 2.0. State University of New York at Stonybrook; 1998. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Davila J, Steinberg SJ, Kachadourian L, Cobb R, Fincham F. Romantic involvement and depressive symptoms in early and late adolescence: The role of a preoccupied relational style. Personal Relationships. 2004;11:161–178. [Google Scholar]

- Extremera N, Durán A, Rey L. Perceived emotional intelligence and dispositional optimism-pessimism: Analyzing their role in predicting psychological adjustment among adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;42:1069–1079. [Google Scholar]

- Extremera N, Fernández-Berrocal P. Emotional intelligence as predictor of mental, social, and physical health in university students. The Spanish Journal of Psychology. 2006;9:45–51. doi: 10.1017/s1138741600005965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabes RA, Eisenberg N. Regulatory control and adults' stress-related responses to daily life events. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;73:1107–1117. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.73.5.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman SS, Rubenstein JL, Rubin C. Depressive affect and restraint in early adolescents: Relationships with family structure, family process, and friendship support. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1988;8:279–296. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Berrocal P, Alcaide R, Extremera N, Pizarro D. The role of emotional intelligence in anxiety and depression among adolescents. Individual Differences Research. 2006;4:16–27. [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. Manual for the self-perception profile for adolescents Denver. Colorado: University of Denver; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Haynes C, Fainsilber Katz L. The asset coding manual: Adolescent social skills evaluation technique. University of Washington at Seattle; 1998. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Joyner K, Udry JR. You don't bring me anything but down: Adolescent romance and depression. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2000;41:369–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julien D, Markman H, Lindahl K, Johnson H, Van Widenfelt B, Herskovitz J. The interactional dimensions coding system. University of Denver; 1997. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M, Beck AT. An empirical clinical approach toward a definition of childhood depression. New York: Raven Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Larson R, Asmussen L. Anger, worry, and hurt in early adolescence: An enlarging world of negative emotions. In: Colten ME, Gore S, editors. Adolescent stress: Causes and consequences. New York: Aldine de Gruyter; 1991. pp. 21–41. [Google Scholar]

- Larson R, Richards M. Divergent realities: The emotional lives of mothers, fathers, and adolescents. New York: Basic Books; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Larson RW, Clore GL, Wood GA. The emotions of romantic relationships: Do they wreak havoc on adolescents? In: Furman W, Brown BB, Feiring C, editors. The development of romantic relationships in adolescence. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1999. pp. 19–49. [Google Scholar]

- Levesque RJR. The romantic experience of adolescents in satisfying love relationships. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1993;22:219–251. [Google Scholar]

- Mavroveli S, Petrides KV, Rieffe C, Bakker F. Trait emotional intelligence, psychological well-being, and peer-rated social competence in adolescence. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2007;25:263–275. [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M, Shaver PR. Attachment theory and emotions in close relationships: Exploring the attachment-related dynamics of emotional reactions to relational events. Personal Relationships. 2005;12:149–168. [Google Scholar]

- Monroe SM, Rohde P, Seeley JR, Lewinsohn PM. Life events and depression in adolescence: Relationship loss as a prospective risk factor for first onset major depressive disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1999;108:606–614. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.108.4.606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nangle DW, Erdley CA, Newman JE, Mason CA, Carpenter EM. Popularity, friendship quantity, and friendship quality: Interactive influences on children's loneliness and depression. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2003;32:546–555. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3204_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieder T, Seiffge-Krenke I. Coping with stress in different phases of romantic development. Journal of Adolescence. 2001;24:297–311. doi: 10.1006/jado.2001.0407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Leary KD, Christian JL, Mendell NR. A closer look at the link between marital discord and depressive symptomatology. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 1994;13:33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Perilloux C, Buss DM. Breaking up romantic relationships: Costs experienced and coping strategies deployed. Evolutionary Psychology. 2008;6:164–181. [Google Scholar]

- von Salisch M. Children's emotional development: Challenges in their relationships to parents, peers, and friends. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2001;25:310–319. [Google Scholar]

- Salovey P, Mayer JD, Goldman SL, Turvey C, Palfai TP. Emotion, disclosure, and health. Washington, DC, U.S.: American Psychological Association; 1995. Emotional attention, clarity, and repair: Exploring emotional intelligence using the Trait Meta-Mood Scale; pp. 125–154. [Google Scholar]

- Sarason IG, Sarason BR, Pierce GR. Social support: Global and relationship-based levels of analysis. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1994;11:295–312. [Google Scholar]

- Seidman G, Shrout PE, Bolger N. Why is enacted social support associated with increased distress? Using a simulation to test to possible sources of spuriousness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2006;32:52–65. doi: 10.1177/0146167205279582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiffge-Krenke I. Testing theories of romantic development from adolescence to young adulthood: Evidence of a developmental sequence. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2003;27:519–531. [Google Scholar]

- Seiffge-Krenke I, Aunola K, Nurmi J. Changes in stress perception and coping during adolescence: The role of situational and personal factors. Child Development. 2009;80:259–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Herman CM, Bolger N. The costs and benefits of practical and emotional support on adjustment: A daily diary study of couples experiencing acute stress. Personal Relationships. 2006;13:115–134. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Cauffman E, Woolard J, Graham S, Banich M. Are adolescents less mature than adults? Minors' access to abortion, the juvenile death penalty, and the alleged APA “flip flop”. American Psychologist. 2009;64:583–594. doi: 10.1037/a0014763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. Should the science of adolescent brain development inform public policy? American Psychologist. 2009;64:739–750. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.64.8.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Silk JS. Parenting adolescents. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of parenting: Vol 1: Children and parenting. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2002. pp. 103–133. [Google Scholar]

- Stroud CB, Davila J. Pubertal timing and depressive symptoms in early adolescents: The roles of romantic competence and romantic experiences. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2008;37:953–966. [Google Scholar]

- Tashiro TY, Frazier P. “I'll never be in a relationship like that again”: Personal growth following romantic relationship breakups. Personal Relationships. 2003;10:113–128. [Google Scholar]

- Quatman T, Sampson K, Robinson C, Watson CM. Academic, motivational, and emotional correlates of adolescent dating. Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs. 2001;127:211–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM. Advances in psychiatric epidemiology: Rates and risks for major depression. American Journal of Public Health. 1987;77:445–451. doi: 10.2105/ajph.77.4.445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson-Shockley S. MS thesis. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign; 1995. Gender differences in adolescent depression: The contribution of negative affect. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, Skinner EA. The development of coping across childhood and adolescence: An integrative review and critique of research. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2011;35:1–17. [Google Scholar]