Abstract

While randomized controlled trials have demonstrated benefits of aldosterone antagonists for patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), they excluded patients with serum creatinine >2.5mg/dl and their use is contraindicated in those with advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD). In the current analysis, we examined the association of spironolactone use with readmission in hospitalized Medicare beneficiaries with HFrEF and advanced CKD. Of the 1140 patients with HFrEF (EF <45%) and advanced CKD (estimated glomerular filtration rate {eGFR} <45 ml/min/1.73m2), 207 received discharge prescriptions for spironolactone. Using propensity scores (PS) for the receipt of discharge prescriptions for spironolactone we estimated PS-adjusted hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for spironolactone-associated outcomes. Patients (mean age 76 years, 49% women, 25% African American) had mean EF 28%, mean eGFR 31 ml/min/1.73m2, and mean potassium 4.5 mEq/L. Spironolactone use had significant PS-adjusted association with higher risk of 30-day (HR, 1.41; 95% CI: 1.04–1.90) and 1-year (HR, 1.36; 95% CI: 1.13–1.63) all-cause readmission. The risk of 1-year all-cause readmission was higher among 106 patients with eGFR <15 ml/min/1.73m2 (HR, 4.75; 95% CI: 1.84–12.28) than among those with eGFR 15–45 ml/min/1.73m2 (HR, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.11–1.61; p for interaction, 0.003). Spironolactone use had no association with HF readmission and all-cause mortality. In conclusion, among hospitalized patients with HFrEF and advanced CKD, spironolactone use was associated with higher all-cause readmission but had no association with all-cause mortality or HF readmission.

Keywords: heart failure, chronic kidney disease, spironolactone, 30 day readmission

The efficacy of aldosterone antagonists in heart failure and reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) patients has been established in multiple randomized controlled trials.1-3 These randomized controlled trials generally excluded patients with serum creatinine >2.5mg/dl. Although post hoc analyses of randomized trials have suggested that spironolactone and eplerenone may improve outcomes in those with impaired renal function,4,5 they did not include patients with advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD). Because these drugs also increase the risk of hyperkalemia and worsening kidney function,4,5 the role of these drugs in patients with advanced CKD remains unclear and their use is contraindicated in those with advanced CKD. In one study based on the American Heart Association Get With the Guidelines-Heart Failure data, among real-world HFrEF patients that also excluded advanced CKD, the use of aldosterone antagonists had no association with mortality or cardiovascular readmission.6 These findings highlight the need for appropriate patient selection and monitoring so that the efficacy observed in randomized trials may be translated into clinical effectiveness in the real-world. Because HF is the leading cause for hospital readmission and under the new healthcare reform law hospitals are facing billions of dollars of loss in Medicare payments for higher than average 30-day all-cause readmission, in the current analysis, we examined if a discharge prescription of an aldosterone antagonist was associated with lower all-cause readmission in older HFrEF patients with advanced CKD.

Methods

Alabama Heart Failure Project was used for data analysis in the current study, the details of which have been described previously.7 Briefly, 9649 charts of fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries discharged from 106 Alabama hospitals between July 1, 1998 and October 31, 2001 with principal diagnosis of HF were identified and abstracted in 6 different 6-month periods.7 Of these, a unique cohort of 8555 patients was identified,7 of which 8049 were discharged alive. Of the 5479 with data on EF, 3067 had EF <45%, of which 1142 had estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <45 ml/min/1.73m2. After excluding 2 patients receiving potassium-sparing diuretics other than spironolactone, the final sample consisted of 1140 patients, of which 207 (18%) received a discharge prescription for spironolactone. Extensive data on baseline demographics, medical history including use of medications, hospital course, discharge disposition including medications, and physician specialty were collected. The primary outcome of the current analysis was 30-day all-cause readmission. Secondary outcomes included 30-day all-cause mortality, HF readmissions and combined end point of all-cause mortality or all-cause readmission. In addition, we also examined the association of spironolactone with these outcomes during longer follow-up. Data on outcomes and time to events were obtained from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Denominator File, Medicare Provider Analysis and Review File, and Inpatient Standard Analytical File.

Pearson chi-square and one-way ANOVA were used for descriptive analysis as appropriate. We estimated propensity scores (PS) for the receipt of spironolactone for each of the 1140 patients based on 45 variables that were used to estimate PS-adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) for the association of spironolactone with outcomes. All statistical tests were 2-tailed with a P value <0.05 considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS-21 for Windows (SPSS, Inc., 2012, Chicago, IL).

Results

Mean age of the patients (n=1140) was 76 (±10) years, 49% were women, 25% were African American. The mean EF was 28 (±9)%, mean eGFR 31 (±10) ml/min/1.73m2, mean serum creatinine 2.47 (±1.59) mg/dl, mean serum potassium 4.5 (±0.75) mEq/L. Patients receiving vs. not receiving spironolactone at discharge were similar in respect to most baseline characteristics (Table 1). However, patients in the spironolactone group were more likely to have prevalent HF and lower serum creatinine levels, and be prescribed digoxin, diuretics, and angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers than those not receiving spironolactone (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized for heart failure who had ejection fraction <45% and estimated glomerular filtration rate <45 mL/min/1.73m2 by spironolactone.

| n (%) or mean (±SD) | Spironolactone on discharge | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| No (n=933) | Yes (n=207) | P value | |

| Age (years) | 76 ±10 | 76 ±8 | 0.860 |

| Female | 451 (48%) | 106 (51%) | 0.455 |

| African American | 228 (24%) | 55 (27%) | 0.520 |

| Smoker | 88 (9%) | 17 (8%) | 0.583 |

| Admission from nursing home | 50 (5%) | 9 (4%) | 0.552 |

| Past medical history | |||

| Prior heart failure | 771 (83%) | 186 (90%) | 0.010 |

| Coronary artery disease | 654 (70%) | 158 (76%) | 0.073 |

| Myocardial infarction | 322 (35%) | 72 (35%) | 0.941 |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention | 165 (18%) | 37 (18%) | 0.948 |

| Coronary artery bypass graft | 323 (35%) | 82 (40%) | 0.174 |

| Hypertension | 682 (73%) | 147 (71%) | 0.543 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 252 (27%) | 54 (26%) | 0.786 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 465 (50%) | 97 (47%) | 0.438 |

| Stroke | 214 (23%) | 46 (22%) | 0.825 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 306 (33%) | 61 (30%) | 0.354 |

| Dementia | 84 (9%) | 15 (7%) | 0.417 |

| Cancer | 21 (2%) | 7 (3%) | 0.342 |

| Clinical and laboratory data | |||

| Pulse (beats per minute) | 91 ±23 | 90 ±22 | 0.686 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 144 ±33 | 134 ±30 | <0.001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 79 ±20 | 76 ±18 | 0.122 |

| Respiratory rate (breaths/minute) | 24 ±6 | 23 ±5 | 0.070 |

| Peripheral edema | 665 (71%) | 164 (79%) | 0.020 |

| Pulmonary edema by chest x-ray | 679 (73%) | 149 (72%) | 0.816 |

| Serum sodium (mEq/L) | 138 ±4.5 | 138 ±5 | 0.040 |

| Serum potassium (mEq/L) | 4.5 ±0.76 | 4.42 ±0.70 | 0.269 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 2.6 ±1.7 | 2.1 ±0.7 | <0.001 |

| Glomerular filtration rate (mL/min/1.73m2) | 30 ±11 | 33 ±8 | <0.001 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dL) | 42 ±21 | 42 ±22 | 0.720 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 36 ±6 | 37 ±6 | 0.033 |

| White blood cell (cell/μL) | 10 ±9 | 9 ±5 | 0.184 |

| In hospital events | |||

| Pneumonia | 271 (29%) | 52 (25%) | 0.257 |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 58 (6%) | 13 (6%) | 0.973 |

| Pressure ulcer | 97 (10%) | 23 (11%) | 0.762 |

| Hospital and care characteristics | |||

| Rural hospital | 209 (22%) | 44 (21%) | 0.720 |

| Cardiology care | 610 (65%) | 156 (75%) | 0.006 |

| Intensive care | 47 (5%) | 11 (5%) | 0.870 |

| Length of stay (days) | 7.76 ±6.5 | 7.77 ±5 | 0.977 |

| Discharge medications | |||

| Renin angiotensin system antagonists | 492 (53%) | 133 (64%) | 0.003 |

| Beta-adrenergic blockers | 235 (25%) | 56 (27%) | 0.578 |

| Loop diuretics | 742 (80%) | 192 (93%) | <0.001 |

| Digoxin | 429 (46%) | 130 (63%) | <0.001 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 196 (21%) | 28 (14%) | 0.014 |

| Potassium supplementation | 348 (37%) | 78 (38%) | 0.918 |

| Anti-arrhythmic drugs | 174 (19%) | 48 (23%) | 0.136 |

| Antidepressants | 196 (21%) | 38 (18%) | 0.393 |

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | 62 (7%) | 11 (5%) | 0.479 |

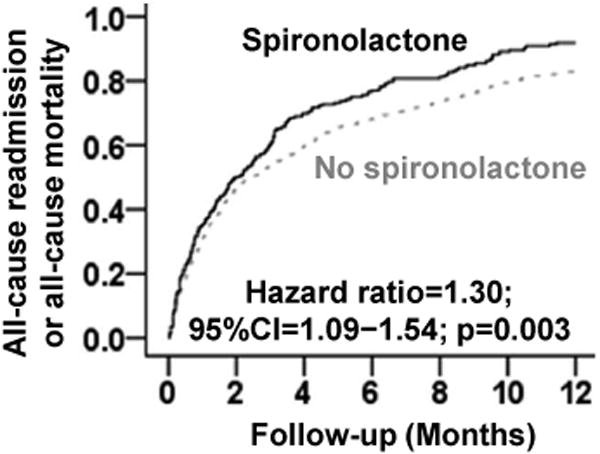

Within 30 days post-discharge, unadjusted all-cause readmissions rates were 30% and 25% for patients receiving and not receiving spironolactone, respectively. PS-adjusted HR (95% CI) associated with spironolactone use was 1.41 (1.04–1.90; Table 2). There was no association with all-cause mortality or HF readmission during 30 days post-discharge, though there was a near-significant association with 30-day combined end point of all-cause readmission or all-cause mortality (Table 2). The risk of all-cause readmission (PS-adjusted HR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.13–1.63) and the combined end point of all-cause readmission or all-cause mortality (PS-adjusted HR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.09–1.54; Table 3 and Figure 1) during one year post-discharge was higher among patients in the spironolactone group. The adverse association of spironolactone use with 1-year all-cause readmission was significantly higher in the 106 patients with eGFR <15 ml/min/1.73m2 (HR, 4.75; 95% CI: 1.84–12.28) than in the 1034 with eGFR 15-45 ml/min/1.73m2 (HR, 1.34; 1.11–1.61; p for interaction is 0.003). Similar differences were observed for 1-year combined end point of all-cause readmission or all-cause mortality (p for interaction, 0.007).

Table 2. Associations of discharge prescription for spironolactone with outcomes at 30 days post-discharge among Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized for heart failure with ejection fraction <45% and estimated glomerular filtration rate <45 mL/min/1.73m2.

| % (total events / total patients) Spironolactone on discharge | Hazard ratio†(95% CI); p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| No | Yes | Unadjusted | Propensity score adjusted | |

| All-cause readmission | 25% (237/933) | 30% (61/207) | 1.19 (0.90–1.57); p=0.233 | 1.41 (1.04–1.90); p=0.027 |

| Heart failure readmission | 12% (116/933) | 12% (25/207) | 0.97 (0.63–1.49); p=0.872 | 0.90 (0.57–1.41); p=0.635 |

| All-cause mortality | 8% (75/933) | 8% (17/207) | 1.01 (0.60–1.72); p=0.961 | 1.05 (0.60–1.82); p=0.866 |

| All-cause mortality or readmission | 31% (285/933) | 34% (70/207) | 1.13 (0.87–1.47); p=0.352 | 1.31 (0.99 –1.73); p=0.058 |

Hazard ratios comparing patients receiving spironolactone on discharge with those not receiving it

Table 3. Associations of discharge prescription for spironolactone with outcomes at 1 year post-discharge among Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized for heart failure with ejection fraction <45% and estimated glomerular filtration rate <45 mL/min/1.73m2.

| % (total events / total patients) Spironolactone on discharge | Hazard ratio† (95% CI); p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| No | Yes | Unadjusted | Propensity adjusted | |

| All-cause readmission | 70% (656/933) | 77% (160/207) | 1.24 (1.04–1.48); p=0.014 | 1.36 (1.13–1.63); p=0.001 |

| Heart failure readmission | 40% (370/933) | 44% (91/207) | 1.14 (0.91–1.44); p=0.260 | 1.02 (0.80–1.30); p=0.847 |

| All-cause mortality | 46% (432/933) | 49% (102/207) | 1.09 (0.88–1.35); p=0.441 | 1.05 (0.83–1.31); p=0.706 |

| All-cause mortality or readmission | 84% (779/933) | 91% (188/207) | 1.22 (1.04–.143); p=0.014 | 1.30 (1.09–1.54); p=0.003 |

Hazard ratios comparing patients receiving spironolactone on discharge with those not receiving it

Figure 1.

Propensity score-adjusted 1-year all-cause readmission rates for hospitalized heart failure patients with ejection fraction <45% and estimated glomerular filtration rate <45 ml/min/1.73m2 receiving and not receiving spironolactone on discharge (CI=confidence interval)

Discussion

The findings of the current analysis demonstrate that in hospitalized older patients with HFrEF (EF <45%) and advanced CKD (eGFR <45), a discharge prescription of spironolactone was associated with higher 30-day and 1-year all-cause readmission, and that this risk was higher in those with eGFR <15 than in patients with eGFR 15-45 mL/min/1.73 m2. Further, spironolactone had no significant association with all-cause mortality or HF readmission in this subset of high-risk patients. These findings further highlight the need for caution if prescribing spironolactone for hospitalized HFrEF patients with advanced CKD.

Severe hyperkalemia and worsening kidney function are the likely underlying mechanisms for poor outcomes among patients with advanced CKD in our study. Although mean baseline serum potassium in our patients was normal and similar between the two treatment groups, it is possible that patients in the spironolactone group were more likely to develop serious hyperkalemia during follow-up. Findings from a post hoc analysis of EMPHASIS-HF data suggest that those with diabetes and CKD had higher risk of developing hyperkalemia.8 Nearly half of the patients in our study had diabetes mellitus. Finally, although similar proportions of patients receiving and not receiving spironolactone received potassium supplements, those in the spironolactone group were more likely to develop life-threatening hyperkalemia. However, incident life-threatening hyperkalemia is unlikely to fully explain an isolated higher hospital readmission without an associated higher mortality among patients in the spironolactone group in our study as deaths associated with hyperkalemia would be expected to be due to cardiac arrhythmias that would also preclude hospital readmission. Spironolactone has also been shown to worsen kidney function,9 although it has been suggested to be temporary.10,11 Further, patients in the spironolactone group in our study had lower baseline serum creatinine levels. Finally, it is also possible that spironolactone was prescribed to patients with greater HF severity and these findings reflect selection bias and residual measured or unmeasured confounding.

According to the 2013 American College of Cardiology Foundation and American Heart Association Guidelines for the Management of HF, aldosterone antagonists should be avoided in HFrEF patients with eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2 and serum potassium >5.0 mEq/L, and both serum creatinine and potassium should be closely monitored (Level of Evidence: A).12 The guidelines also recommend that the inappropriate use of aldosterone antagonists in these patients is potentially harmful due to risks of life-threatening hyperkalemia or worsening kidney function (Level of Evidence: B).12 Thus, patient selection is important and it has been suggested that aldosterone antagonists should be used in patients similar to those enrolled in the randomized controlled trials.13 Findings from our study suggest that aldosterone antagonists need to be used with caution in HFrEF patients with CKD Stage 3B (eGFR between 30 and 44 mL/min/1.73 m2) and, consistent with guideline recommendations, avoided in those with eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2.12 HF is the leading cause for readmission,14 and if the findings from the current study can be replicated in other HF populations, it may be reasonable to delay prescriptions of aldosterone antagonists until after hospital discharge. Of note, in the same patient population (EF <45 and eGFR <45), ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers have been shown to reduce mortality without increasing all-cause readmission.15

Several limitations of our study need to be acknowledged. Due to the observational design and small sample size, both bias and chance are alternate explanations and confounding may account for some or all of these findings. We also had no data on the dose of spironolactone and follow-up data on serum creatinine and potassium. Crossover of treatment during follow-up may have resulted in regression dilution and underestimation of the associations.16 Finally, these findings based on a single state from an earlier era of HF therapy may limit generalizability. In conclusion, the higher all-cause readmission and lack of mortality benefit associated with spironolactone use among hospitalized HF patients with EF <45 and eGFR <45 highlight the need for caution in the use of aldosterone antagonists in these patients.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Dr. Ali Ahmed was supported by the National Institutes of Health through grants (R01-HL085561, R01-HL085561-S and R01-HL097047) from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and a generous gift from Ms. Jean B. Morris of Birmingham, Alabama.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Pitt B, Remme W, Zannad F, Neaton J, Martinez F, Roniker B, Bittman R, Hurley S, Kleiman J, Gatlin M. Eplerenone Post-Acute Myocardial Infarction Heart Failure E, Survival Study I. Eplerenone, a selective aldosterone blocker, in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1309–1321. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pitt B, Zannad F, Remme WJ, Cody R, Castaigne A, Perez A, Palensky J, Wittes J. The effect of spironolactone on morbidity and mortality in patients with severe heart failure. Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:709–717. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199909023411001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zannad F, McMurray JJ, Krum H, van Veldhuisen DJ, Swedberg K, Shi H, Vincent J, Pocock SJ, Pitt B, Group EHS. Eplerenone in patients with systolic heart failure and mild symptoms. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:11–21. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vardeny O, Wu DH, Desai A, Rossignol P, Zannad F, Pitt B, Solomon SD Investigators R. Influence of baseline and worsening renal function on efficacy of spironolactone in patients With severe heart failure: insights from RALES (Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:2082–2089. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eschalier R, McMurray JJ, Swedberg K, van Veldhuisen DJ, Krum H, Pocock SJ, Shi H, Vincent J, Rossignol P, Zannad F, Pitt B Investigators E-H. Safety and Efficacy of Eplerenone in Patients at High Risk for Hyperkalemia and/or Worsening Renal Function: Analyses of the EMPHASIS-HF Study Subgroups (Eplerenone in Mild Patients Hospitalization And SurvIval Study in Heart Failure) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:1585–1593. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.04.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hernandez AF, Mi X, Hammill BG, Hammill SC, Heidenreich PA, Masoudi FA, Qualls LG, Peterson ED, Fonarow GC, Curtis LH. Associations between aldosterone antagonist therapy and risks of mortality and readmission among patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. JAMA. 2012;308:2097–2107. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.14795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feller MA, Mujib M, Zhang Y, Ekundayo OJ, Aban IB, Fonarow GC, Allman RM, Ahmed A. Baseline characteristics, quality of care, and outcomes of younger and older Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized with heart failure: findings from the Alabama Heart Failure Project. Int J Cardiol. 2012;162:39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eschalier R, McMurray JJ, Swedberg K, van Veldhuisen DJ, Krum H, Pocock SJ, Shi H, Vincent J, Rossignol P, Zannad F, Pitt B. Safety and Efficacy of Eplerenone in Patients at High Risk for Hyperkalemia and/or Worsening Renal Function: Analyses of the EMPHASIS-HF Study Subgroups (Eplerenone in Mild Patients Hospitalization And SurvIval Study in Heart Failure) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:1585–1593. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.04.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams EM, Katholi RE, Karambelas MR. Use and side-effect profile of spironolactone in a private cardiologist's practice. Clin Cardiol. 2006;29:149–153. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960290405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wrenger E, Muller R, Moesenthin M, Welte T, Frolich JC, Neumann KH. Interaction of spironolactone with ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers: analysis of 44 cases. BMJ. 2003;327:147–149. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7407.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tamirisa KP, Aaronson KD, Koelling TM. Spironolactone-induced renal insufficiency and hyperkalemia in patients with heart failure. Am Heart J. 2004;148:971–978. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE, Jr, Drazner MH, Fonarow GC, Geraci SA, Horwich T, Januzzi JL, Johnson MR, Kasper EK, Levy WC, Masoudi FA, McBride PE, McMurray JJ, Mitchell JE, Peterson PN, Riegel B, Sam F, Stevenson LW, Tang WH, Tsai EJ, Wilkoff BL. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2013;128:e240–319. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31829e8776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Butler J, Ezekowitz JA, Collins SP, Givertz MM, Teerlink JR, Walsh MN, Albert NM, Westlake Canary CA, Carson PE, Colvin-Adams M, Fang JC, Hernandez AF, Hershberger RE, Katz SD, Rogers JG, Spertus JA, Stevenson WG, Sweitzer NK, Tang WH, Stough WG, Starling RC. Update on aldosterone antagonists use in heart failure with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction. Heart Failure Society of America Guidelines Committee. J Card Fail. 2012;18:265–281. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1418–1428. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0803563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahmed A, Fonarow GC, Zhang Y, Sanders PW, Allman RM, Arnett DK, Feller MA, Love TE, Aban IB, Levesque R, Ekundayo OJ, Dell'Italia LJ, Bakris GL, Rich MW. Renin-angiotensin inhibition in systolic heart failure and chronic kidney disease. Am J Med. 2012;125:399–410. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clarke R, Shipley M, Lewington S, Youngman L, Collins R, Marmot M, Peto R. Underestimation of risk associations due to regression dilution in long-term follow-up of prospective studies. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;150:341–353. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]