Abstract

To maximize tumor excision and minimize collateral damage is the primary goal of cancer surgery. Emerging molecular imaging techniques have to “image-guided surgery” developing into “molecular imaging-guided surgery”, which is termed “targeted surgery” in this review. Consequently, the precision of surgery can be advanced from tissue-scale to molecule-scale, enabling “targeted surgery” to be a component of “targeted therapy”. Evidence from numerous experimental and clinical studies has demonstrated significant benefits of fluorescent imaging in targeted surgery with preoperative molecular diagnostic screening. Fluorescent imaging can help to improve intraoperative staging and enable more radical cytoreduction, detect obscure tumor lesions in special organs, highlight tumor margins, better map lymph node metastases, and identify important normal structures intraoperatively. Though limited tissue penetration of fluorescent imaging and tumor heterogeneity are two major hurdles for current targeted surgery, multimodality imaging and multiplex imaging may provide potential solutions to overcome these issues, respectively. Moreover, though many fluorescent imaging techniques and probes have been investigated, targeted surgery remains at a proof-of-principle stage. The impact of fluorescent imaging on cancer surgery will likely be realized through persistent interdisciplinary amalgamation of research in diverse fields.

Keywords: Targeted therapy, Targeted surgery, Molecular imaging, Fluorescent imaging, Image-guided surgery, Multimodality imaging, Multiplex imaging, System molecular imaging

1. Introduction: the concept of targeted surgery

Tremendous advancement in molecular biology research has revolutionized clinical oncology practice and has led to the emergence of “targeted therapy” in the last century. Targeted therapy of cancer is a new type of regimen that involves the use of drugs or other modalities to precisely identify and eradicate cancer cells and tissues while generally causing minimal damage to normal cells and tissues. Through extensive preclinical research, targeted therapy has begun to be translated into certain clinical practices including medical, radiation and surgical oncology[1].

In medical oncology, targeted therapy can be termed “molecular targeted therapy” and refers to development and application of a class of medications that block the growth and spread of cancer by interrupting the specific molecular abnormalities that drive growth and progression[2]. Traditional chemotherapy kills both normal and malignant dividing cells by interrupting essential cellular events, such as DNA replication and microtubule assembly. Molecular targeted therapy focuses on molecular abnormalities that are specific to cancer cells, such as aberrant proteins or receptors expressed solely or dominantly in cancerous tissues [3]. Therefore, this strategy offers higher response rates with fewer adverse effects when compared with conventional chemotherapy. The target of molecular targeted therapy is a cancer biomarker, and the impetus for driving the progress of the technique is our burgeoning understanding of the molecular biology of cancers.

In radiation oncology, targeted therapy can be termed as “targeted radio therapy” and refers to radiating cancerous tissues or organs more precisely, which allows for higher radiation dose delivery with less toxicity. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy and image-guided radiation therapy are two such targeted radiotherapy strategies, and they allow further dose escalation and a reduction in normal tissue radiation exposure [4, 5]. Moreover, therapeutic radiation on the molecular scale has further expanded the application of targeted radiotherapy through delivering radioactivity specifically to cancer cells by targeting cancer biomarkers, molecular pathways, or gene expression [6–9]. Similarly, the targets of targeted radiotherapy are either tumor foci or specific molecular or genetic characteristics of cancer, and the impetus for driving the field forward is improvement in imaging and radiation technology.

However, in surgical oncology, the concept of targeted therapy remains ambiguous and largely undefined. What does targeted surgery mean? For solid tumors in particular, it can simply imply a surgery with a definite target. In the target-specific context, surgeons can work towards their ultimate goals of maximizing tumor excision, minimizing collateral damage, and minimizing the risk of metastasis or recurrence. Therefore, the following two issues are essential for targeted surgery: (1) how to define the target (tumor) and from what aspects will a surgeon evaluate the target; and (2) what strategies can be taken to realize the process of targeted cancer tissue resection. To address both issues, one indispensable approach is the use of non-invasive imaging techniques.

Current imaging modalities such as ultrasonography (US), computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and positron emission tomography (PET) may facilitate the accurate diagnosis, staging and visualization of tumors (target), which are prerequisites for successful surgical therapy. Furthermore, advances in optical fluorescence imaging (FI), which uses fluorochromes to enhance the visualization capability of the operating surgeon beyond that of white-light reflectance, provides a major opportunity to improve surgical outcomes. Subsequently, “image-guided surgery” has been increasingly adopted, which involves the use of imaging as surgical navigation to visualize the tumor intra-operatively and allows the surgeon to maximize tumor excision and minimize collateral damage at the tissue-scale[10]. With the explosion of molecular imaging, “molecular diagnostic screening” and “molecular image-guided surgery” using targeted molecular probes are emerging and have the potential to improve the visualization, characterization, and measurement of biological processes at the molecular and cellular levels for surgery[11]. These advances have expanded the current concept of surgery and hold significant promise to improve surgical precision from tissue-scale to molecule-scale. Therefore, the term “targeted surgery” will be used in this paper to indicate surgical approaches that are assisted by molecular imaging.

“Targeted surgery” can be defined as the precise, specific and radical resection of cancerous tissue according to histologic characteristics or even molecular signatures that are acquired by radiology and/or molecular imaging. This method results in high resectability rates with little damage to normal tissues and better outcome, under the precondition of ensuring minimal metastatic potential. The critical part of the definition is to match a surgical approach with the biology of the tumor. Therefore, the target of targeted surgery is cancerous tissue, and the impetus for driving progress of the technique is molecular imaging that promotes surgical precision from tissue-scale to molecule-scale. Targeted surgery includes, but is not limited to, image-guided surgery, and it emphasizes the assessment of the molecular characteristic of cancerous tissue beyond morphological changes and/or discoloration. Furthermore, surgeons use imaging techniques both during operation and also before and after surgery coordinately. Unlike “minivasive surgery”, such as endoscopic, laparoscopic and robotic technologies, which has a goal of minimizing collateral damage, targeted surgery stresses maximum tumor excision while minimizing the potential for metastasis and recurrence in terms of tumor biology through either open-field surgery or minivasive surgery. In the era of targeted surgery, we must understand that the goal is not the simply safe excision but more importantly an understanding of how and if surgery will alter a tumor's inherent biology in vivo.

A variety of non-invasive molecular imaging modalities can be used in targeted surgery. Optical imaging using near-infrared (NIR) fluorescence light is an emerging non-invasive in vivo cancer imaging modality, and it is an ideal methodology for targeted surgery. In this review we first offer a framework for conceptualizing targeted surgery. Next, we provide a summary of target-specific fluorescence imaging probes, which serve as the key components that accelerate the development of fluorescent imaging for targeted surgery. Then, we give an overview of the current status in fluorescent imaging of cancerous tissues for targeted surgery in order to identify advantages and limitations. Special emphasis will be placed on discussing the obstacles that impede the future development of fluorescent imaging in targeted surgery and offering potential solutions. Finally, the concept of “systems molecular imaging” will be defined in this review. While fluorescent imaging techniques have been widely explored in preclinical research, targeted surgery remains in the stage of proof-of-principle for clinical research. Optimizing the impact of fluorescent imaging for cancer patient is expected to be realized through the persistent interdisciplinary amalgamation of research in diverse fields.

2. Fluorescent imaging for targeted surgery

2.1Inherent characteristics enable fluorescent imaging suitable for targeted surgery

Molecular imaging techniques serve as the most important prerequisite for targeted surgery. Until now, many different non-invasive molecular imaging modalities have been used in targeted surgery, either with or without combination with a navigation system. Those that could provide intraoperative guidance for the tumor resection, mainly including MRI [12, 13], US[14], and FI were of special focus. Each of these modalities has its own merits and limitations in visualizing tumors for targeted surgery, as reviewed previously[11]. Among them, FI is the most suitable for targeted surgery because of its inherent properties and advantages: (1) no ionizing radiation is required;(2) high-resolution images are produced at a high speed; (3) the readout of fluorescence imaging is in real time, making it the optimal choice for intraoperative guidance; (4) the coverage field is wide; (5) it is easy to complement with other imaging modalities and combine with multiple modalities; and (6) it is possible to detect multiple signals concomitantly and to track multiple molecules in vivo in order to probe the diverse pathobiological processes that underlie disease states. For example, by exciting quantum dots (QDs) with a single wavelength to obtain emissions at several different wavelengths, multiplex detection of multiple targets can be acquired in a single study. More importantly, the introduction of exogenous fluorescent probes can provide images that can overlay molecular or cellular information onto the pre-existing anatomical and pathological images, which has the potential to substantially improve the outcome of targeted surgery [15]. Another advantage of fluorescence imaging that should be emphasized is that the fluorescence signal of a target can potentially be dramatically modulated by designing novel activatable probes. Such probes with signal amplification capability will be illustrated in the following sections. The aforementioned significant advantages of fluorescence imaging facilitate its widespread use in image-guided surgery and will enable its gradual translation into clinical applications.

2.2The indications for targeted surgery with assistance of fluorescent imaging

In clinical practice, not all cancer patients can undergo targeted surgery with the assistance of fluorescent imaging. Suitable candidates must meet the following criteria, though additional requirements may exist as well. The location of the tumors must not be well defined. Targeted surgery is especially suitable for tumors that are difficult to differentiate from adjacent normal tissue (such as breast cancers) and those that are next to complex structures with crucial physiological functions (such as brain tumors). Furthermore, targeted surgery is well suited for tumors that have a high local recurrence or high positive margin rates and that do not have well-delineated surgical margins (for example, early-stage skin cancers) nor effective adjuvant therapies (for example, thyroid tumors that are treatable using 131I). Additionally, the stages of the tumor must be able to be graded accurately, and the tumors must remain operable without un-resectable metastasis. Finally, the molecular and biological characteristics of tumor must be available, which enable effective accumulation of the imaging agent in the targeted cancerous tissues. This permits analysis of the activity of specific molecules and biological processes that could affect tumor behavior and/or its response to therapy.

Targeted surgery is often more challenging to realize than conventional treatment regimens. Several conditions must be met for targeted surgery to be considered. For preoperative diagnostic screening, it is desirable to have the ability to distinguish localized tumors with minimal metastatic potential from those that are systemic from inception, to perform molecular subtyping and molecular staging, to identify the molecular signature that is used to guide surgical procedure, and to screen for suitable cases whose biology is most surgically relevant as well as to orientate the surgeons to make a surgery planning considerably. For image-guided surgery, it is desirable to have the ability to intraoperative visualize tumor in real time, to replicate the molecular signature obtained from preoperative imaging, and to guide surgeons to precise resection of the cancerous tissues. Finally, it is desirable to have post-operation follow-up at molecular level to guide post-operative neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

3. Target-specific fluorescent probes: the driving force for targeted surgery

Molecular imaging typically depends on acquisition of signals that are generated from cancer biomarkers after administration of target-specific agents with a modality-specific tag. Because fluorescent tags suffer the limitation of light penetration in biological tissues, the most successful clinical application of fluorescent imaging for targeted surgery is image-guided surgery, other than preoperative or postoperative imaging.

The past decade has witnessed the rapid expansion of fluorescent molecular imaging. Fluorescent molecular imaging is becoming more mature and has the potential to revolutionize image-guided surgery. Fluorescent molecular imaging enables improvement in the accuracy of excision from tissue-scale to molecule-scale, which is termed “molecular image-guided surgery”. However, before fluorescent molecular imaging can be realized clinically, one prerequisite is that more highly sensitive and target-specific fluorescent probes must be available for clinical use. Targeted surgery needs to use fluorescent probes with superior chemical and photo-physical properties for imaging targets. It is important that tumor targets can be detected at very low probe concentrations and that fluorescent probes can report molecular events by a wide variety of spectroscopic mechanisms.

3.1 Fluorochromes with high sensitivity and safety

Fluorescent imaging requires in situ excitation of fluorochromes to produce tissue-penetrating light emission. Considering the limited penetrating ability of light, selection of fluorochromes with suitable absorption and emission wavelengths is critical in order to ensure sufficient imaging sensitivity (Figure 1). To gain high sensitivity, wavelengths of incident excitation light are best when longer than 780 nm to avoid auto fluorescence[16]. In this case, the emission wavelengths of fluorochromes are always confined in the well-known first near-infrared window (NIR- I, 750–900 nm), which has the advantages of low absorption, relatively deep penetration ability, low auto-fluorescence, high spatial resolution and high sensitivity.

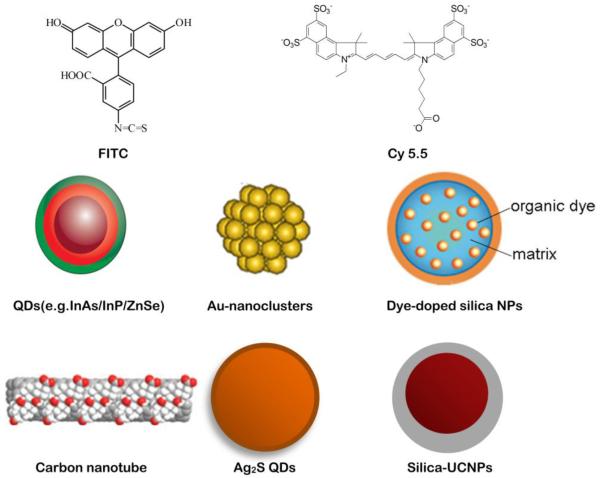

Figure 1.

Representative fluorescent materials for molecular imaging. (modified from ref [32], [205, 206])

Currently available NIR-I fluorochromes are mainly organic small molecule fluorophores, which are also the most efficient fluorescent materials for targeted surgery. This situation derives from the flexibility of NIR fluorescence dyes to serve as either labeling agents or activatable sensors, with additional features of high biocompatibility, in vivo application, low cost and ease of handling. Furthermore, they can generally provide high signal-to-noise ratios (greater than 1,000) as a result of ingenious chemical design[17]. The first fluorescent organic molecule is quinine sulfate, which was identified in 1845[18]. Subsequently, a variety of organic compounds have been discovered and prepared, including fluorescein[19], rhodamine[20], BODIPY(boron-dipyrromethene) dyes[21], cyanine dyes[22] and their derivatives. Currently, there are only two NIR fluorophores approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), indocyanine green (ICG) and methylene blue (MB), both of which are non-toxic small molecules that can be rapidly excreted from the body.

However, dyes that are readily available for in vivo imaging are still quite limited mainly because of poor hydrophilicity and photostability, low quantum yield, insufficient stability in biological systems and low detection sensitivity. Because bright and photostable dyes with red to NIR fluorescence are especially in demand for in vivo imaging, the development of novel fluorophores has been pursued through adding additional ring systems[23, 24]or heteroatoms to the existing fluorophores[25–27]. Significant progress has been achieved in the recent development of NIR dyes, including cyanine dyes, squaraine, phthalocyanines, porphyrin derivatives and BODIPY analogues with significantly improved chemical stability and photostability, high fluorescence intensity and long fluorescent life. Among them, cyanine and Alexa Fluor dyes and their derivatives have been most widely used for in vivo imaging. The IRDye family from LI-COR, HiLyte Fluor dyes from AnaSpec, and DyLight Fluor dyes produced by Dyomics are similar to Alexa Fluor dyes in spectrum characteristics and can be alternatively used. Safety and toxicity profiles have been reported on only one NIRF dye, IRDye 800CW, although numerous preclinical imaging studies have employed near infrared fluorescence (NIRF) dyes with functional groups for conjugation with antibodies, antibody fragments, peptides, sugars, or other biomolecules for noninvasive imaging of diseases, such as cancer, vascular disease and infection. [28].

NIR-I with longer emission wavelengths may promote less auto-fluorescence and light scattering, deeper tissue penetration, higher resolution and easier separation from standard white-light reflectance and may dramatically facilitate the development of targeted imaging and image-guided surgery. Recent work has demonstrated a dramatic improvement in imaging quality when using fluorophores that emit within the second near-infrared window (NIR-II, 1000–1700 nm)[29–31]. The advantages of NIR-II fluorophores include negligible tissue auto fluorescence, reduced photon scattering, and low levels of photon absorption. More importantly, when imaging at progressively longer wavelengths, they allow for the resolution of deep anatomic features (up to ~ 5 mm) that are otherwise unresolvable in the standard NIR-I region (~ 0.2 mm). Most of current NIR-II fluorophores consist of either nanomaterials or molecular dyes encapsulated in a polymer matrix. The NIR-II nanometer-sized NIR structures, such as inorganic quantum dots (QDs)[32–35], organic dye-encapsulated nanoparticles[36], carbon nanotubes[37, 38], as well as other nanoparticles (NPs)[39, 40], have rapidly emerged as fluorescent probes with superior sensitivity for targeted surgery. However, currently employed NIR-II nanometer-sized materials are generally excreted slowly and are largely retained within the organs of the reticuloendothelial system such as the liver and spleen. Small molecules with NIR-II emission that can be rapid clearly through by renal system and contain functional groups for attaching targeted ligands would be ideal for medical diagnostics. Recently, the first small molecule NIR-II fluorophore was prepared by modifying organic dye IR-1061[41]. This small molecule NIR-II fluorophore can be excreted through the renal route. It is expected that more work in this field will facilitate discovery of new NIR-II fluorophores, FDA approval of these new dyes and their eventual translation into a clinical setting.

Nanoparticle-based NIRF probes can potentially overcome several limitations of conventional NIR organic dyes, such as poor hydrophilicity and photostability, low quantum yield and detection sensitivity, insufficient stability in biological systems and weak multiplexing capability. The biggest advantage of NIR NPs is the structural versatility that enables development of novel multi-functional NPs. These nanomaterials can be simultaneously conjugated with several functional molecules that include targeting moieties, therapeutic agents and imaging moieties, thus providing potentials for therapies and diagnostics. NIR NPs undoubtedly will play a critical role in targeted surgery. One of the classic applications of nanometer-sized NIRF probes is intraoperative assessment of the sentinel lymph node (SLN) for the presence of tumor cells by local injection of nanoprobes[42], or identification of tumor by nanoprobes such as QDs functionalized with arginine-glycine-aspartic (RGD) peptide[43]. Certain nanoprobes have demonstrated efficacy in cellular imaging of tissue samples in clinic[44]. However, applications of inorganic nanoparticles for in vivo imaging in clinic are rare because of several fundamental problems and technical barriers, such as the potential cytotoxicity of their heavy metals ingredient (such as Cd, Se) or surface-coated materials (CTAB, for example)[45–47], small-scale and expensive preparation[48], difficulties in reproducibility and comparability, poor biodistribution caused by phagocytic functions of the reticuloendothelial system (RES) and mononuclear phagocytic system, and difficulty with precise quantification[28].

Another type of promising fluorescent material are fluorescent lanthanide complexes. It is well known that enzymes are involved in multiple pathways in tumorigenesis and can drive tumor invasion and growth. The design of fluorescent lanthanide complexes could lead to imaging probes with optimized selectivity and response times, which can be applied to high-throughput screening of enzyme inhibitors and for real-time monitoring of enzyme kinetics[49]. Luminescent lanthanide complexes can be further used to monitor enzymatic conversions and therefore can serve as probes for the determination of enzyme activities. Specifically, erbium and ytterbium containing Y2O3 nanoparticles can absorb NIR light at 980 nm and emit higher energy and shorter wavelength photons in an anti-Stokes emission process[50]. These upconversion nanomaterials are very different from traditional dyes because they are capable of absorbing and combining multiple low energy photons and then releasing a single higher energy photon in an anti-Stokes emission process. Because no biological fluorophores are capable of producing similar behavior, interference from auto-fluorescence can be eliminated and thus high imaging quality can be achieved[51]. This feature renders upconversion fluorescent lanthanide complexes promising for targeted surgery, though so far there are no reports of their application to surgery guidance.

Fluorescent proteins such as green fluorescent protein (GFP) and red fluorescent protein (RFP) are powerful tools for biological research. It is important to note that they are generally limited to use in animal models. In preclinical experiments, the tumor cells can be genetically prelabelled with fluorescent proteins based on their genetic encodability [52]. In clinical settings, only cell and gene therapies provide a possible mechanism to enable genetically encoded fluorescent-protein expression from tumors. Even if all the technical obstacles for achieving tumor-selective gene delivery were eventually overcome, the value of fluorescent proteins for targeted surgery would still require further evaluation. Therefore their use in imaging will not be discussed in this review.

3.2 Available strategies enable NIRF probes with target-specific properties

Molecular imaging requires a fluorescent probe to be specific for a given tumor biomarker. Probes for targeted surgery must be biomolecules that can specifically localize to targeted cancerous tissues. As each tumor has its unique biologic profile, selection of a specific biomarker is essential for the success of tumor imaging. Cancer driver genes, proteins and molecular pathways have received significant attention and provide broad opportunities for targeted NIR imaging. Currently, three major methods have been explored to enable NIR probes with target-specific properties: passive targeting, active targeting, and target-activatable strategy.

The passive targeting strategy has been widely used in pre-clinical and clinical research. Through passive targeting, nonspecific fluorescent small-molecules, dyes, polymers, or nanoparticles can be delivered to tumors via the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect. EPR is characterized by leaky microvasculature and inefficient lymphatic drainage of tumors that allows nanoparticles or macromolecule probes to electively enter the tumor interstitial spaces and remain there [53, 54]. A successful example is the clinical implementation of ICG for in vivo fluorescent imaging. The rationale of this technique is that ICG binds to plasma proteins and forms macromolecular complexes that are excreted from biliary tract [55]. The macromolecular ICG complexes tend to remain in vascular compartment, leak into the tumor interstitial space through the leaky cancerous microvasculature, and accumulate in the SLN. ICG has been successfully used for intraoperative mapping of the SLN[56–58], visualization of gliomas [59, 60], hepatobiliary cancer[61, 62], head and neck cancer[63], assistance with breast-conserving surgery[64], and for NIR angiography and cholangiography [65–67]. However, its efficacy for imaging of many other solid tumors is limited[68]. Another successful example is 5-aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA), which elicits the synthesis of fluorescent porphyrins. Passive accumulation of porphyrins in tumors results in enhanced fluorescent signal in the tumor. Successful applications of 5-ALA were reported in resection guidance of intracranial tumors[69–73], spinal meningioma[74], hepatocellular carcinoma[75] and bladder tumors[76], as well as gastric cancer staging with fluorescence laparoscopy[77]. Nanoparticles are also a class of materials that can take advantage of passive targeting. Preclinical studies showed that nanoparticles in the size range from 10–100 nm might effectively escape from renal excretion and deposit in tumors after prolonged circulation[78]. The factors influencing the amount of nanoparticles that accumulate in tumors depend on properties of both the fluorescent nanoprobes (such as dimension, surface modification, and circulation half-life) and the tumor (including the leakiness of the neovasculature, the degree of tumor angiogenesis, and the extent of suppression of lymphatic filtration). However, the EPR effect was originally established in animal tumor models, and its clinical applications has been hampered by the uncertainty of relevance in humans, insufficient clinical characterization, and heterogeneity of the EPR effect between the different types of tumors[79].

Currently, the most promising fluorescent probe for tumor imaging is based on target-specific abilities. One strategy is active targeting. Active targeting utilizes the chemical or biological conjugation of fluorochromes with cancer targeting ligands (such as small molecules, peptides, proteins, antibodies, affibodies [80], or aptamers). Ongoing efforts for development of cancer tissue specific fluorescent probes are mainly focused on active targeting strategies. Various cancer hallmarks that are associated with malignant phenotypes have been exploited, such as growth factor signaling receptors, limitless replicative potential, sustained angiogenesis, and increased proteolytic activity resulting in tissue invasion and metastasis. Many of these hallmarks are suitable for active targeting, especially tumor cell-surface biomarkers. Active targeting has been proved to significantly improve the efficiency (specificity and selectivity) of delivery of the probes to cancerous tissue. A representative active targeting fluorescent probe has so far been reported in only one clinical study. In this clinical trial, folate receptor, which is overexpressed in 90–95% of epithelial ovarian cancers, was localized by fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) labeled folate through active targeting in the context of surgical resection of ovarian cancers[81]. Other promising active targeting strategies for clinical translation include but are not limited to the following. The alpha-v beta-3 (αvβ3) integrin and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptors are indicators of vascular angiogenesis. Integrin αvβ3 is uniquely expressed in tumor vasculature and aggressive tumor cells, making it a potential target for imaging of the tumor vascularity[82]. The preclinical applications of fluorescent labeled RGD peptides in targeted surgery were reported in ovarian cancer[83], fibrosarcomas[84] and colorectal intra-abdominal metastases[85]. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and its specific antibody, affibody, nanobody or aptamer[86] have also shown promise. Overexpression of EGFR contributes to oncogenesis by proliferation, dedifferentiation, inhibition of apoptosis, invasiveness and lack of adhesion dependence[87]. Related reports in targeted surgery is so far limited to head and neck cancers[88–90]. Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) is also a possible target, which in excess promotes the growth of cancer cells and exists in about 1/5 breast cancer patients. Anti-HER2 antibody conjugated to IRDye 800CW was used in targeted surgery assisted with fluorescent imaging in breast cancers[91, 92]. Finally, fluorescent labeled epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM) or probes targeting prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) may be helpful in targeted surgery procedures for prostate cancer[93, 94]. It is important to note that the aforementioned targeting ligands specific for biomarkers have also been labeled with numerous imaging moieties for other imaging applications such as nuclear imaging, MRI, optical, acoustic and photoacoustic imaging, as well as multimodal imaging. These applications are also very important for targeted surgery, which will be illustrated in detail later.

An alternative target-activatable strategy has also been developed for surgery guidance. In this strategy, the probes are designed to be silent until they interact with the target proteins, a specific microenvironment, or reactive species presented in the tumor. The major consequences of the interaction are to maximize the signal from the target, and/or minimize signal from the background, which both lead to improved target-to-background ratio (TBR). Several strategies can be used to design activatable fluorescence probes. A typical method involves the enzymatic activation of the probe by secreted extracellular or cell-surface enzymes. In this strategy, the probe is silent until it is activated by specific microenvironments. Enzymatic cleavage leads to generation of fluorescence signal mostly in the extracellular or intracellular space depending on the location of the stimuli. Because enzymatic activity is a key factor required for tumor invasiveness, using enzymes as imaging targets in a target-activatable strategy could help to identify invasive tumor edges, which can directly contribute to more radical resection in targeted surgery[95, 96]. In this way, urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA) is considered a promising agent for targeted surgery, which is helpful for delineation of tumor margins. uPA and its receptor (uPAR) is a ligand/cell surface target pair that regulates multiple pathways involved in matrix degradation, cell motility, metastasis, and angiogenesis[97]. In one study, recombinant peptides of the amino terminal fragment (ATF) of the receptor-binding domain of uPA were labeled with NIR fluorescence dyes either as peptide-imaging or peptide-conjugated nanoparticle probes. Systemic delivery of the uPAR-targeted imaging probes in mice bearing orthotopic breast or pancreatic tumor xenografts led to the accumulation of the probes in the tumor and stromal cells, resulting in strong signals for optical imaging of tumors and identification of tumor margins[98]. Another class of representative proteases is matrix metalloproteinase (MMP). MMP2 and MMP9 are the best characterized proteases overexpressed by tumors. The activity of MMP-2 and -9 are intimately involved in multiple processes of tumor invasion and metastasis in a wide range of tumors in clinic[99], and they have served as important biomarkers for targeted surgery through target-activatable strategies.

3.3 Delivery of the fluorescent probes to the target sites

For successful targeted surgery, target-specific fluorescence agents have to be delivered to the cancerous tissue. Furthermore, the probes require adequate time to fully interact with the target in order to achieve stable binding and must be retained in the targeted sites until non-bound probes are cleared from the circulation. At saturation doses, the uptake of high-affinity probes such as antibody-based probes depends heavily on antigen expression level, whereas at sub-saturation doses, the imaging signal is primarily limited by the efficiency of probe delivery. It should be noted that many fluorescent dyes have relatively low hydrophilicity and tend to accumulate in tumor non-specifically, suggesting that these fluorescent dyes may compromise the delivery and targeting specificity of probes. To minimize this impact, suitable fluorochromes should be selected carefully for labeling of biomolecules in many cases. For example, IRDye® 800CW was found to be less “sticky” to cells than Cy5.5, which partly enabled EGF-IRDye® 800CW to have higher specificity and subsequently a higher TBR than those of EGF-Cy5.5[16]. Moreover, through appropriate chemical modifications, the hydrophilicity or hydrophobicity of fluorochromes can be modulated to reduce the overall “stickiness” of probes.

In general, fluorescent probes can be introduced to a subject by either systemic or local administration. After systemic administration by intravenous injection, the first hurdle for probes is the risk of nonspecific binding by inhibitor proteins present in plasma. This may reduce the amount of target specific binding and cause high background in the surgical tissues, or even have serious systemic side effects. Secondly, the blood vessel walls provide a barrier for fluorescent probe delivery to targeted tumor tissues. For tumors whose size is larger than 2mm, abnormal neovascularization occurs causing the EPR effect, which enables probes to infiltrate into the interstitium of tumor tissues passively and then accumulate. Once extravasation has occurred, the fluorescent probes encounter the third barrier for adequate binding with their targets—the extracellular matrix (ECM) tissues that surround the target cells. The only way to cross the ECM tissue is through diffusion. The process of diffusion into the tumor can be prevented by high hydrostatic pressure, leading to inhomogeneous infiltration of the probes. Once the third barrier is overcome, the target-specific binding between probes and their target present on or in the cell has to occur. The fourth barrier, the cellular basement membrane, is by-passed by receptor-mediated endocytosis or passive transport. The process of internalization results in further amplification of the fluorescence signal. In addition, systemic administration allows the probes to distribute throughout the whole body and thus avoids missing satellite lesions surrounding the main tumor mass that are separated by normal tissue, though this route does associate with increased systemic side effects.

In smaller lesions that are less than 1–2 mm in size or in hypovascular tumors, neoangiogenesis has not been “switch on” yet, therefore the angiogenesis-directed targeting may not be possible due to the lack of adequate vascularization[100, 101]. Hypovascular tumors present extensive desmoplastic reaction, which may inevitably cause hypovascularity and perfusion impairment and create barriers that fence off tumor cells from circulating active fluorescent probes[102–104]. Consequently, despite remarkable advances in molecular imaging in the past decade for detection of most tumors, similar success has not been achieved in both small and hypovascular tumors. In the situation of hypovascularity, though diffusion is very poor and likely to be limited to a fraction of a millimeter, it remains an indispensable delivery avenue. Therefore, necessary strategies must be undertaken to break these barriers. In these cases, indirect instead of direct indicators of tumor growth could be useful for detection of hypovascular tumors as well as small tumors in the earliest stages of carcinogenesis. Many hypovascular tumors such as pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma are not characterized by the abundance of malignant epithelial cells but by ECM, also called as desmoplasia. These ECM components include collagen, fibronectin, catalytically active enzymes and proteinases proteoglycans, hyaluronic acid, cytokines and growth factors, and other biomarkers; they are associated with tumor hypoxia, and can thus serve as indirect indicators for imaging. Several novel in vivo NIRF imaging techniques have been developed utilizing MMP[105, 106], cathepsin cysteine proteases[107–109] and hypoxia markers[110]. Additionally, the experience gained in development of relatively new therapeutic strategies for breaching the stromal barrier may be applied to effectively deliver florescent probes. For example, a potential strategy has been explored to improve the efficiency of drug delivery by depletion of tumor stroma [111–113]. By co-administration of a smoothened inhibitor (IPI-926) to deplete tumor-associated stromal tissue, a transient improvement of gemcitabine delivery occurred with a detectable depletion of tumor stroma and increase of angiogenesis[111]. Another possible strategy for aiding drug delivery is to relieve vessel compression by breaking down the ECM scaffold[114, 115]. Similar efforts for gaining imaging benefit may be devoted to deplete the desmoplastic stroma or restore the vasculature. However, future research is needed to validate this idea.

It is important to note that local administration is an ideal choice especially for intraoperative fluorescent imaging. Local administration could minimize the risk of systemic side effects and the overall dose. However, probe delivery mainly depends on penetration into the targeted tissue. This inefficient diffusion may sacrifice discrimination of deeper structures or would require frequent re-application. Finally, an important determinant for eliminating the background signal and optimal imaging time of probes is the clearance of non-bound probe rapidly through the liver and/or the kidney in time. Both clearance route and rate are critical for determination of the probe blood half-life time, which affects surgical scheduling.

4. The status quo of development of targeted surgery

4.1Preoperative molecular diagnostic screening

The preconditions for undergoing targeted surgery include the following: to detect and localize the tumor, to exclude the patients who have metastasized beyond eligibility for resection, to identify the molecular signatures which can be used to guide surgical procedure, to screen the suitable cases whose biology are surgically most relevant, and to orientate the surgeons to enable surgery planning.

For targeted surgery planning, it is critical to identify biochemical activity of a tumor before surgery by non-invasive scanning using a closely related molecular imaging agent. Such non-invasive whole-body scanning includes PET, MRI, and single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT). Whole-body scanning would enable early detection when tumors are still operable, assist with pre-operative staging and therapy planning, and facilitate postoperative monitoring and adjuvant treatment. Pre-operative staging would exclude patients whose tumors do not accumulate the targeted probes or those have metastasized beyond eligibility for resection. To maximize comparability between whole-body scanning (PET, MRI, etc.) and intra-operative imaging, and to minimize the number of injections, it is advantageous that the molecular probe ideally carries labels for both the whole-body modality and fluorescence.

In clinical settings, ex vivo high-throughput assays on patient-derived tissues are partially suitable for the above purposes to document the molecular characteristics and metastatic potential of the target tumor before surgery. These high-throughput assays mainly include single nucleotide polymorphisms, immunohistochemical markers, and deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) microarray gene signatures. These new powerful assays facilitate the simultaneous collection of many thousands of biological data items from a single biopsy or blood sample from an individual. For example, a 70-gene signature derived from a DNA microarray analysis of 78 young patients with breast cancer that was associated with a short interval to distant metastases was published recently [116]. However, high-throughput assays are dependent on surgical procurement of tissue, yielding a host of risks and potential complications, and make it an unrealistic option for every cancer patient.

Another clinically applicable strategy is non-invasive scanning using a closely related molecular imaging agent. Whole-body scans, such as X-ray, CT, MRI, US, PET or SPECT provide the surgeon with useful anatomical and morphological information about the tumors. This information can include the location, size, shape, and margins (edges) of tumor and the important relationship to adjacent normal tissue, and it help to rule out tissue-scale metastases. “Radiogenomics” or “radioproteomics”, which correlate unique features of tumor morphology and physiology garnered through non-invasive imaging with specific patterns of gene/protein expression, can further serve as surrogates for high-throughput assays and try to link high-throughput molecular diagnostics and diagnostic imaging[117, 118]. In clinical settings, both high-throughput assays and “radiogenomics” /“radioproteomics” have been adopted mainly for molecular diagnostic screening in medical or radiation oncology[119, 120]. However, “radiogenomics” or “radioproteomics” are still based on tissue-scale analysis. There is no report so far for their application in targeted surgery.

Ideally, surgical planning with a tumor-targeted probe using a pre-operative whole-body scan would be carried out in conjunction with intra-operative fluorescence guidance for tumor resection. Molecular imaging has experienced a rapid growth in the past decade, and many molecular imaging techniques have entered into clinical trial phase. Besides the well-known [18F]-Fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) PET, several radiolabeled ligands of integrin αvβ3 have been tested in humans[121–124]. Integrin αvβ3 is a cell-surface transmembrane heterodimeric glycoprotein, which plays a key role in both tumor angiogenesis and tumor cell migration. Because it is overexpressed in various cancer types, integrin αvβ3 serves as a very promising target for tumor detection, staging, anti-angiogenesis therapy guidance and therapy response monitoring, in addition to surgery guidance. It should be emphasized that postoperative imaging is an important component of targeted surgery. After surgery, imaging is needed to monitor the outcome of the surgery, to detect residual tumor and recurrence, and to guide further adjuvant treatment. The developmental trends of postoperative imaging are similar to preoperative molecular diagnostic screening, and will not be discussed in further depth here.

Because of many obstacles for translating probes into clinical use, molecular screening using molecular imaging techniques has not yet achieved routine practical application for targeted surgery. With powerful propulsion of molecular imaging into clinical applications, the extensive use of targeted surgery is likely just around the corner, though how to coordinate intraoperative molecular image-guided surgery with preoperative or postoperative whole-body imaging remains a large challenge.

4.2Molecular imaging-guided surgery

The great challenge for intraoperative imaging is to replicate the findings from preoperative imaging and provide surgeons with detailed information about tumor margins, the tumor volume for resection, lymph nodes and vital structures such as nerves, lymphatics and ureters. It is known that insufficient visual difference between tumor and normal tissue when using white-light reflectance alone contributes to potentially preventable cancer persistence or recurrence, and unacceptable morbidity when too much tissue is resected. With the exciting frontiers in the field of cancer surgery afforded by fluorescent imaging, it is expected that this hurdle will be overcome. Because there are not yet tumor-specific NIRF probes approved for clinical use, initial clinical studies were conducted using the FDA approved nonspecific fluorescent probes such as untargeted dyes ICG[125, 126] and fluorescein sodium[127, 128]. The increasing application of untargeted dyes in surgery guidance has expanded the surgeon's visual capability beyond that of white-light reflectance. Discussions of fluorescence-guided surgery have been comprehensively reviewed recently, including summary of the currently available fluorescent probes[32, 129, 130], instrumentations[56, 131, 132] and application status[133–136], as well as challenges and limitations[137–139]. Here, these topics will not be repeatedly discussed.

It is no doubt that “molecular image-guided surgery” is the most fascinating part of targeted surgery. However, “molecular fluorescence imaging-guided surgery” has not matured enough to be regularly used in clinic, and its future still heavily depends on the development of high-quality target-specific fluorescent molecular probes. Until now, one clinical trial has been reported and it demonstrated that the biggest benefit of intraoperative tumor-specific fluorescence imaging is to improve intraoperative staging as well as more radical cytoreductive surgery. In this first-in-human trial of fluorescent imaging guided resection of ovarian cancer, folate receptor-alpha (FR-α) was selected as the target and folate-FITC was used as the probe. The results show that folate-FITC appears to be safe as an intravenously injected formulation. Interestingly, using the strategy of target-specific fluorescent imaging, the surgeon found a significantly higher number of tumors through fluorescent deposits than with conventional visual inspection. Clinical studies such as this could certainly lead to improved intraoperative staging and more radical cytoreductive surgery in patients with ovarian cancer[81](Figure 2). Despite these exciting results, clinical reports on fluorescent imaging are still quite limited, and more translational efforts are required to harness this burgeoning technology. The volume of work relating to molecular fluorescence imaging in guiding cancer surgery has expanded over the last two decades in preclinical experiments. Numerous results highlight that fluorescent molecular imaging guided surgery with target-specific probes can yield more significant benefits than fluorescent imaging guided surgery with nonspecific agents.

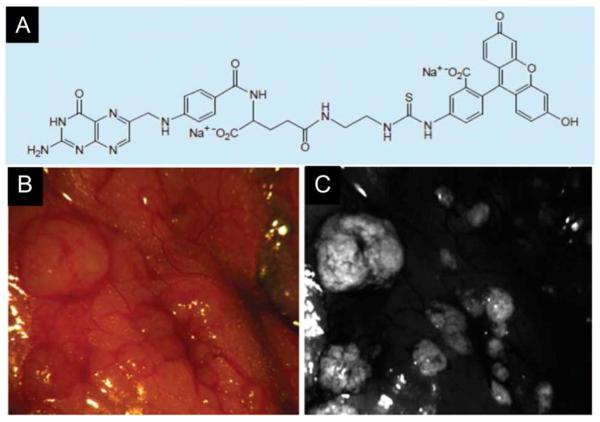

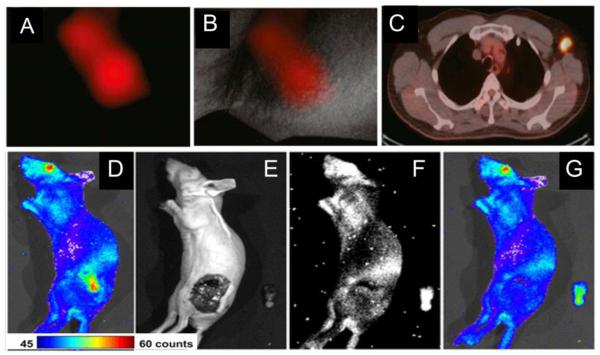

Figure 2.

The first clinical trial of fluorescent molecular imaging-guided surgery in ovarian cancer by folate receptor-α targeting.

(A): Schematic of folate-FITC (molecular weight: 917 kDa). Folate-FITC was synthesized by conjugating folate to FITC through an ethylenediamine spacer.

(B): Color image of a representative area in the abdominal cavity.

(C): The corresponding tumor-specific fluorescence image with A in the same area in the abdominal cavity, which demonstrated that the biggest benefit of intraoperative tumor-specific fluorescence imaging would be improved intraoperative staging as well as more radical cytoreductive surgery.

Reprinted with permission from[81]. Copyright 2011, Nature medicine.

Another potential benefit is to detect ignored primary and potential metastatic lesions in certain special organs, which are otherwise impossible to detect with white light. Evidence to support this finding comes from surgery guided by NIR targeted imaging of integrin αvβ3expression. In the study, colorectal liver metastases and mesenteric metastases were clearly demarcated during surgery by using IntegriSense 680 (VisEn Medical, Woburn, USA), which consists of an integrin αvβ3antagonist labeled with a NIRF dye[140]. This study indicates that fluorescent imaging of liver metastases is highly challenging, because liver tissue often manifests high absorption of visible light, and many fluorescent dyes are also characterized by hepatic uptake and clearance. Integrin αvβ3 expression is constantly low in hepatocytes and high in tumor, however, and it is possible to clearly delineate hepatic and peritoneal metastases during surgery. Once translated into the clinic, this imaging strategy holds great potential to improve the quality of abdominal cancer surgery[85](Figure 3A).

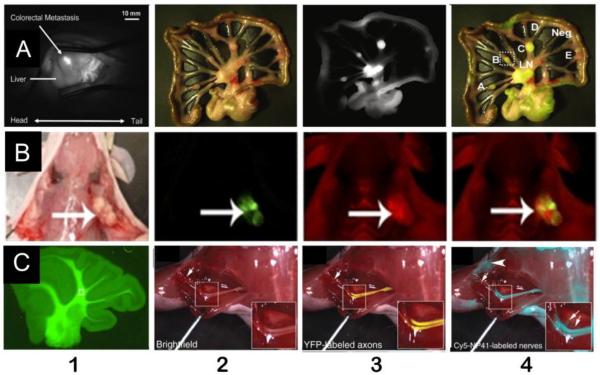

Figure 3.

Representative experimental results manifest the potential breakthroughs that may result from fluorescent molecular imaging-guided surgery.

(A): Colorectal liver and peritoneal metastases can be clearly demarcated during surgery using an integrinαvβ3 targeted NIRF probeIntegriSense®680. A1:Intraoperative NIRF image of a colorectal liver metastasis lesion in a rat 24 h after injection of IntegriSense®680. A2–4: Shown are a color image (A2), a NIR fluorescence image (A3), and a pseudo-colored green merge of the two images (A4) of a part of the jejunum and adjacent mesentery of a rat bearing multiple mesenteric metastases, which were all acquired intraoperatively.

(B): Cy5-labeled free activatable cell-penetrating peptides (ACPPs) delineated tumor at the margin of resection. B1: White light image of a MDA-MB-435 xenograft following skin incision and tumor (large arrow) exposure. B2: Fluorescence image of GFP-labeled tumor cells from the same animal as in A. B3: Fluorescence image 6 h following i.v. administration of Cy5-labeled free ACPPs showing increased uptake by the tumor (large arrow) compared to surrounding tissue. B4: Overlay fluorescence image showing co-localization of the Cy5 free ACPP with the GFP-labeled tumor. Following gross tumor excision by standard (unguided) technique, the tumor bed (*) seen with white light.

(C) Nerve-highlighting fluorescent imaging for image-guided surgery.

C1: After i.p. injection, BMB stains the cerebellar white matter. C2–4: Cy5-NP41 (acetyl-SHSNTQTLAKAPEHTGC-(Cy5)-amide) labeling of the sciatic nerve in Thy1-YFP transgenic mice. C2: Low-power bright field view of left exposed sciatic nerve. Inset shows magnified view of central boxed region. C3: Same nerve as in C2 with YFP fluorescence (pseudocolored yellow) superimposed on the bright field image, showing transgenic expression of YFP in axons. C4: Same nerve as in a and C2 viewed with Cy5 fluorescence(pseudocolored cyan for maximal contrast during live surgery) superimposed on the bright field image, showing nerve labeling with Cy5-NP41. Arrows in C3 and C4 point to thin buried nerve branches that are better revealed by the long-wavelength Cy5 fluorescence than by bright field reflectance or shorter wavelength YFP fluorescence. There is some nonspecific labeling of skin(asterisk) and cut edges of muscle (arrowhead) by Cy5-NP41. Fortunately, such nonspecific labeling hardly ever has the filamentous appearance of nerves, so an experienced surgeon can usually distinguish nonspecific from specific targets.

Reprinted with permission from [85, 143, 145, 147].

Copyright 2011, the journal of the European Society of Surgical Oncology and the British Association of Surgical Oncology; Copyright 2010, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America; Copyright 2011, Nature biotechnology; Copyright 2006, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.

The third potential benefit is to highlight tumor margins more clearly[141–143]. This advantage has been well confirmed in the literature[143]. In one study, a method was developed to delineate the tumor margins during surgery using activatable cell-penetrating peptides (ACPPs). The ACPPs are coupled to inhibitory polyanions via a cleavable linker, which can be cut upon exposure to proteases (MMP-2 and MMP-9). Cleavage of the linker leads to dissociation the inhibitory polyanions and release of the polycationic peptides that bind to the target and enter cells[144]. Cy5-labeled ACPPs (Cy5-ACPPs) and ACPPs conjugated with dendrimers (ACPPDs) were prepared in this study. Both Cy5-ACPPs and ACPPDs delineate the margin clearly between tumor and adjacent normal tissue (Figure 3B)[143].

The fourth potential benefit is to specifically identify important normal structures that are invisible when using nonspecific fluorochromes (Figure 3C). Although cure is the primary goal of cancer surgery, the preservation of important structures such as nerves, blood vessels, ureters and bile ducts is equally crucial in achieving optimal patient outcome. With the exception of nerves, they all can be visualized by ICG. Recently, nerve-targeted probes have been developed and used in animals during fluorescent molecular imaging guided surgery in order to avoid nerve injury [145–147]. 4,4' -[(2-methoxy-1,4-phenylene)-di-(1E)-2,1-ethenediyl] bis-benzenamine (BMB, excitation at 480nm) and its red-shifted derivative 4-[(1E)-2-[4-[(1E)-2-[4-aminophenyl]ethenyl]-3-methoxyphenyl]ethenyl]-benzonitrile (GE3082) were developed as nerve highlighting agents [146, 147]. BMB is a Congo red derivative and a synthesized fluorescent molecule. Available data suggests that BMB binds selectively to myelin; therefore BMB and its derivative have the potential to be used intraoperatively to visualize nerves. After systemic injection, BMB can also cross the blood–brain barrier, so it could be used in both central nervous system (CNS) and peripheral nervous system (PNS) (Figure3C1)[147]. To this point, BMB has been tested in mice, rats and pigs and showed promising results. BMB can also be easily radiolabeled with 11C, which opens the possibility for dual fluorescent-PET imaging. Similarly, by phage display screening, the peptide NP41 (NTQTLAKAPEHT) was identified that can bind preferentially to peripheral nerves (Figure3C2–4) [145]. NP41 was then labeled with either fluorescein amidite (FAM, excitation 488nm, emission 520 nm) or Cyanine Dyes (Cy5, excitation 650nm, emission 670 nm). These two probes were evaluated in the thy1-yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) transgenic mice whose axons appear yellow by white light to the naked eye, because these axons were genetically encoded with YFP [148]. After systemic injection of Cy5-NP41, the sciatic nerves were seen clearly by intraoperative fluorescent imaging, even though they were buried by normal tissue. Furthermore, by co-administration of FAM-NP41 with Cy5-ACPPs, which was used to highlight tumor margins, sciatic nerves could be differentiated from surrounding tumor tissue during the resection by means of fluorescent imaging with different excitation light in different wavelengths. These results are especially important to avoid nerve injury during targeted surgery. Using this technique, nerve arborizations as small as 50 μm could be detected. One pitfall is that these probes can only be taken up by PNS as the blood–brain barrier (BBB) prevents CNS uptake.

In addition, many target-specific fluorescent probes have been developed for identification of nodal metastases. Strategies include active targeting to HER2 receptor[149] and macrophages[150],as well as passive targeting by nanoparticles[151]. NIRF mapping of SLN with non-specific ICG has been used efficiently in breast cancer[152], lung cancer[153],melanoma[154, 155], and cervical cancer[156]. It is expected that target-specific fluorescent imaging can significantly improve the identification of nodal metastases. More data are necessary to support this hypothesis, especially head-to-head comparison studies between nonspecific fluorochromes and target-specific fluorescent imaging probes. With the rapid development of molecular imaging, it is likely that more benefits of “fluorescent molecular image-guided surgery” will be uncovered.

5. Multimodality imaging: a potential solution for the conundrum of fluorescent imaging of whole-body

The major challenge of fluorescence imaging is limited depth of tissue penetration. For fluorescence imaging-guided surgery, this drawback is overcome because overlying tissues are progressively reflected or resected in the surgical procedure. However, it still prevents the use of fluorescence imaging for whole-body scanning, especially in large living subjects such as humans. Moreover, fluorescent imaging provides effective assistance during intra-operative image-guided surgery, but careful coordination is required to gain and use the data from preoperative whole body imaging and intraoperative real time fluorescent imaging, or from postoperative following up imaging and the outcome of surgery. A possible solution to these issues is to develop multimodality imaging techniques by which fluorescent imaging is combined with another clinical applicable whole-body molecular imaging modality (such as PET, SPECT, MRI or US). These imaging modalities have their own features and advantages and may provide desirable complements to fluorescent imaging during targeted surgery. Multimodality imaging generally requires combination of multiple imaging instruments accompanied with multimodality imaging probes. To maximize comparison between whole-body imaging and intra-operative fluorescent imaging and to minimize the number of injections, it is ideal that the molecular probe carries multiple labels for both the whole-body modality and fluorescence imaging.

5.1 Hybrid nuclear and fluorescence imaging

Hybrid nuclear and fluorescence imaging combines the beneficial properties of both radio-guidance and fluorescence imaging. Hybrid nuclear and fluorescence imaging coordinates preoperative molecular diagnostic screening with intraoperative guidance into a consistent and unified whole; it is the ideal candidate for the purpose of targeted surgery. Currently, nuclear imaging is the “gold standard” for clinical molecular imaging. Positron and gamma-emitting radionuclides enable nuclear imaging with high sensitivity and without any depth-penetrated limitation, which provides effective support and complement for NIRF imaging. Moreover, nuclear and NIRF imaging share common physical attributes in that both modalities involve the administration of a contrast agent that, upon decay, produces photons that propagate through tissues and are collected to generate an image.

Hybrid nuclear and fluorescent probes can be achieved either by using two separate chemical entities including a radioactive probe and a fluorescent probe, or by exploiting a single entity containing both nuclear and optical properties. With advances in bioconjugation and labeling chemistry, it is typically straightforward to chelate or isotopically substitute radionuclides, or to simultaneously couple NIRF dyes on targeting moieties such as peptides, antibodies, or sugars. The dual labeled probes can then be used for further imaging applications. It is also reasonable to perform preoperative nuclear imaging and intraoperative NIRF imaging separately by introducing either nuclear probes or NIRF probes sequentially or by mixing the two probes together for imaging purposes. This type of combination is not strictly hybrid nuclear and fluorescence imaging, as the biological characteristics of these two probes, especially biodistribution and pharmacokinetics, may be very different for probes labeled with nuclear or NIRF reporting moieties, even though the targeting ligand is exactly the same. This strategy is still a viable and useful option for targeted surgery, since it can easily combine “molecular image-guided surgery” with “molecular diagnostic screening” before surgery, especially while translation of target-specific probes into clinic remains highly challenging.

Most hybrid nuclear and fluorescence imaging studies have been performed by introducing dual-labeled NIR/PET (or SPECT) imaging agents. For clinical use, the hybrid radioactive and fluorescent probe ICG-99mTc-nanocolloid was developed and recently applied successfully in clinical SLN biopsy of 65 patients with penile cancer. After peritumoral injection, the hybrid radioactive and fluorescent probe contributed to a complete targeted surgery that allowed preoperative SLN mapping using lymphoscintigraphy and SPECT/CT, intraoperative SLN identification using a gamma camera, followed by fluorescence imaging, and postoperative confirmation of SLN excision using a portable gamma camera (Figure 4)[157]. For comparison purposes, blue dye (Laboratoire Guerbet, Aulnay-Sous-Bois, France) was intradermally administered in all patients in the same way as the ICG-99mTc-nanocolloid injection shortly before surgery. The results showed that the improved tissue penetration of fluorescence imaging enabled clearer visualization of the SN and its borders compared with blue dye. This surgery technique utilized a non-targeted probe instead of target-specific agents. Many preclinical studies on animals have also validated serials of dual-labeled NIRF/PET (or SPECT) imaging target-specific agents[158]. By using the dual labeled (64Cu and IRDye 800CW) Trastuzumab[159], the metastases in mice with highly metastatic breast cancers can be successfully simultaneously detected with PET and NIRF imaging. It was concluded that (64Cu-DOTA)n-trastuzumab- (IRDye800)m may play an important role in preoperative staging and intraoperative resection of HER-2– positive breast cancer[160]. In a similar experiment in mice, SLN metastases in prostate cancer were identified using a dual labeled (64Cu and IRDye 800CW) Ab for EpCAM targeted imaging. It was found that the probe,(DOTA)n– anti-EpCAM – (IRDye 800)m, has potential for applications in intraoperative prostate cancer treatment[161].

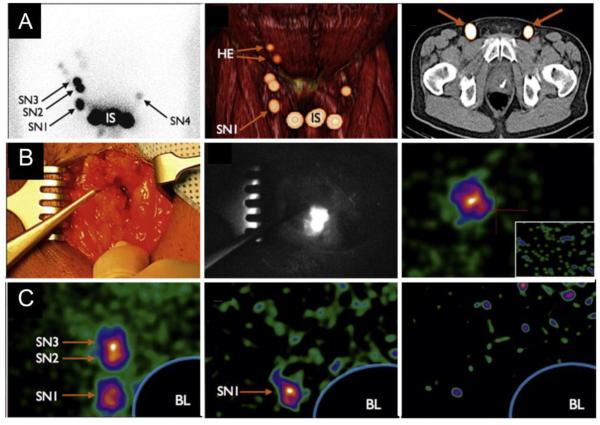

Figure 4.

Intraoperative metastases and sentinel node identification in clinical settings with the hybrid radioactive and fluorescent tracer indocyanine green (ICG)-99mTc-nanocolloid.

(A) Preoperative detection of metastases in sentinel lymph nodes.

A1: Lymphoscintigraphy showing the injection site (IS) with three sentinel lymph nodes on the right side and one sentinel lymph node on the left side. A2: Three-dimensional volume-rendered single-proton emission computed tomography supplemented with computed tomography image revealing that the most caudal sentinel lymph node on the right side is located in an inferior Daseler zone. A3: Axial fused SPECT/CT images depicting both radioactive SNs.

(B) Intraoperative identification of metastases in sentinel lymph nodes.

B1–2: a color image (B1) and the corresponding NIR image (B2) showed that a radioactive, non-blue sentinel lymph node is clearly seen using fluorescence imaging.

B3: The portable gamma camera provides an overview image of the sentinel lymph nodes that can be used to verify complete SN removal after excision (figure inlay).

(C)Post-excision confirmation of complete sentinel node (SN) removal using a portable gamma camera. C1: Blocking the injection site using the Sentinella suite software visualizes the three SNs on the right side. C2: Post-excision image after removal of three radioactive/fluorescent nodes (as shown in A2) shows that the most caudal SN is still in situ. C3: After excision of the remaining SN, which proved to be tumor positive at histopathology, complete SN removal is verified. BL = blocked injection site using Sentinella Suite software; HE = higher echelon nodes.

Reprinted with permission from [157]. Copyright 2014, European urology.

Another strategy to realize hybrid nuclear and fluorescence imaging is to utilize radioluminescent materials to establish optical imaging as an expansion of nuclear medicine and radiology. Two types of such hybrid strategies are available: (1) Cerenkov luminescence imaging (CLI) using high energetic β-emitters to achieve optical imaging ability [162, 163]and (2) nanophosphor platform excited by X-ray irradiation. Cerenkov luminescence was first described in 1934 as a phenomenon that occurs when high-speed Compton electrons cause emission of optical photons when a charged particle moves faster than the speed of light in a dielectric medium[164]. This phenomenon has not been utilized by the imaging field for in vivo molecular imaging until very recently[162, 165, 166]. Moreover, CLI has been successfully validated in humans using either 131I or 18F-FDG as a probe (Figure5A)[167, 168]. Using CLI for tumor-targeted surgery was also demonstrated for the first time in small animal models[169]. In this study, 18F-FDG, the most popular PET probe used in clinic, was applied as the radioluminescent agent to detect tumor and guide tumor resection surgery with a prototype customized fiberscopic Cerenkov imaging system (Figure 5B). Similarly, the feasibility of Cerenkov luminescence endoscopy (CLE) was built in order to use Cerenkov light that originates from radionuclides to guide endoscopic surgery. This CLE system was composed of an optical fiber bundle/ clinical endoscope, an optical imaging lens system, and a sensitive low-noise charge coupled device (CCD) camera. The subsequent in vivo imaging study conducted on tumor bearing mice injected with 18F-FDG showed that endoscopic Cerenkov luminescence imaging is promising for targeted surgery by providing preoperative whole PET imaging and intraoperative guidance for endoscopic surgery[170]. Furthermore, the ability of CLI to map metastatic spread to local lymph nodes was also reported[171, 172]. The potential advantage of CLI is that it can easily implement hybrid nuclear and optical imaging through choosing various existing clinically approved nuclear imaging tracers. Compared to nuclear imaging alone, CLI has higher throughput, easy handling and greater surface resolution. However, the signal from CLI is still weak and it is urgent to further improve the sensitivity of the current system for fluorescent imaging guided surgery.

Figure 5.

Cerenkov luminescence imaging in clinical settings and for providing guidance in experimental targeted cancer surgery.

A: Representative CL images of 18F-FDG–positive axillary lymph node (left axillae).

B: White-light photograph from left axilla, overlaid with significant CL signal (A).

C: PET/CT images of 18F-FDG–positive left axillae lymph node. This signal colocalized with CL finding. D: Mouse bearing C6 glioma after tail-vein administration of 37 MBq (1 mCi) of 18F-FDGwas imaged by commercially available optical IVIS system. E–G: Mouse was imaged by IVIS optical system (E) and fiber-based system (F) after surgery to remove tumor tissues. Ambient-light images are on left, luminescent images are in middle, and fused images are on right (G).

Reprinted with permission from[168, 169]. Copyright 2012 and 2014, Journal of nuclear medicine.

Intriguingly, strong efforts have been made to further harness the energies of Cerenkov photons. The radiation luminescence was firstly demonstrated to be an efficient internal light source to excite QDs both in vitro and in vivo. In vivo multiplexing fluorescence imaging was readily achieved by using multiple QDs with different emission wavelength and a single type of radiation source such as 131I instead of laser illumination[173]. More recently, activatable nanoparticles that are excited by an 18F-FDG decay-derived signal were designed to produce secondary Cerenkov-induced fluorescence[174]. In this report, gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) was conjugated to FAM-labeled and MMP2 cleavable peptides (IPVSLRSG) to produce biocompatible activatable probe (AuNP-IPVSLRSG-FAM)[175]. The fluorescence was quenched when FAM was coupled to the AuNP surface by the peptide IPVSLRSG until the linker was cleavage by MMP-2. Once activation occurs, FAM was released and its emission becomes detectable. Furthermore, free FAM can also excited by the colocalized18F- FDG Cerenkov luminescence and emit additional fluorescence, which could be spectrally separated from Cerenkov luminescence produced by 18F-FDG directly by means of multispectral codependent imaging, and hence to quantify the activation of the probe. After injection of 18F-FDG and AuNP-IPVSLRSG-FAM together into the mice bearing a MMP-2–overexpressing tumor subcutaneously, the glucose metabolism and enzymatic (MMP-2) activity could be readout separately by PET and fluorescent imaging. The idea of using the secondary Cerenkov-induced fluorescence imaging (SCIFI) by co-localized radiopharmaceutical can also be extended to other fluorochromes or fluorescent nanoparticles. Importantly, besides using Cerenkov photons as an illumination source for excitation of fluorophores, X-ray radiation can also be used to excite some fluorescent materials (such as nanophosphor) to produce optical signal[176]. This X-ray resulted fluorescent imaging coupled with CT is highly promising and may find applications in image guided surgery.

5.2Hybrid MRI and NIR imaging

MRI can provide an effective complement to fluorescent imaging in targeted surgery due to its high spatial resolution, relatively widespread availability, lack of radioactivity and no limitation of penetration. From a technology viewpoint, it is feasible to synthesize dual-modality probes that carry both an MRI reporter and a fluorescent molecule on the same targeting ligand. Yet the weakness of using MRI for molecular imaging rather than for anatomy imaging is its low sensitivity. The detection limit of MRI is on the order of 10−5 M Gd chelate or Fe[177, 178]. Therefore using highly sensitive MRI contrast agents such as nanoparticles are essential to generate sufficient MRI signal. To date, most MRI contrast agents are either T1 (such as Gd chelates) or T2-weighted (such as superparamagnetic iron oxide particles [SPIO]). Dendrimeric nanoparticles coated with ACPPs were recently used as nanoplatforms that were further labeled with Cy5 and Gd. The ACPPs also contained PLGLAG as a linker, which can be cut specifically by MMP-2 and MMP-9 in vivo[179]. The consequence of cleavage is to activate the probe and release Gd and Cy5 into the tumor, which can be detected by MRI and NIRF imaging, respectively. This clever dual-mode probe showed low background and high tumor to background ratios, which enables its use in targeted surgery for MRI-guided clinical screening, presurgical planning, intraoperative fluorescence-guided surgery, and postoperative evaluation of the completeness of resection[180]. Another dual MRI-NIRF imaging agent was prepared by conjugating HER-2 affibodies with NIR-830 and SPIO. The HER-2 targeted SPIO showed selective uptake by both primary and disseminated ovarian tumors in the peritoneal cavity of mice, indicating the potential for improvement of targeted surgery(Figure 6)[181].

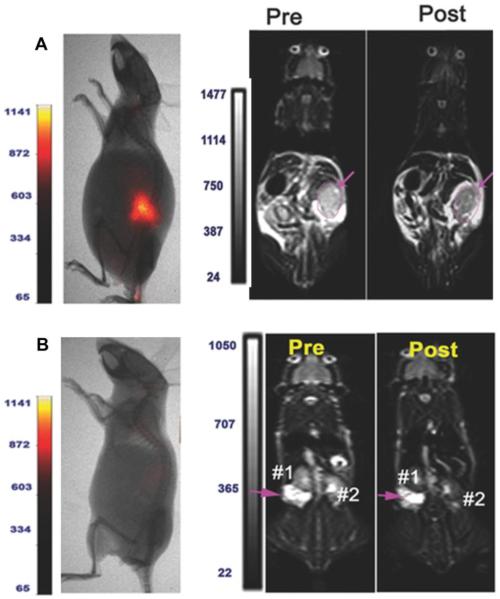

Figure 6.

Dual modality imaging of SKOV3 tumor bearing mice by hybrid MRI and NIR imaging.

(A) Optical imaging revealed strong signals in the primary tumor in the tumor bearing mice following NIR-830-ZHER2:342-IONP administration. T2-weighted MRI also showed marked signal decrease (16%) in a large primary tumor (pink arrow).

(B) MRI of SKOV3 tumor bearing mice after NIR-830-BSA-IONP injection. There was no contrast change in pre- and post-MR images of the tumor.

Reprinted with permission from[181]. Copyright 2014, Small.

5.3 Dual-modality photoacoustic and NIRF imaging

Laser-induced photoacoustic imaging (PAI) is an emerging imaging modality that provides the opportunity to combine existing optical contrast with acoustic imaging. To an extent, PAI breaks the limits of penetration of optical imaging by using laser excitation and acoustic emission waves[182]. PAI is able to map tumors located several centimeters beneath the tissue surface with high spatial resolution (30μm–1 mm, which is adjustable by changing ultrasound frequency). A number of photoacoustic contrast agents have been developed and validated to further improve the imaging and penetration ability of PAI[183–186].

By using a multifunctional target-specific nanoprobe, PAI can be easily combined with other imaging modality to guide tumor resection [187–189]. To date, PAI has been successfully combined with NIRF imaging. Specifically an uPAR-targeting probe was prepared through labeling with NIR-830 dye and conjugation to an amphiphilic polymer-coated SPIO. Interestingly, SPIO has been commonly used for MRI but also been approved to serve as a novel PA contrast agent[190]. With the guidance of this novel probe, a surgeon successfully resected the primary tumor and suspicious tissue in mice bearing mammary tumors. There are two deficiencies yet to be improved. First, the signal in liver is strong because of SPIO uptake by the RES, though the tumor signal was much stronger than that of the internal organs. Second, certain lymph nodes metastases were missed. The reason may be either insufficient sensitivity of NIRF/PAI, or the high signal from the liver overlapping the signal from the lymph nodes[191]. In addition, a HER-2/neu targeted probe for dual-modality PAI and fluorescence imaging was designed and synthesized. The study further demonstrated the potential use of the probe for intraoperative imaging of ovarian cancer using the PAI/fluorescence imaging guidance approach[192].

6. Multiplex imaging: strategies to conquer tumor heterogeneity

The rapid development of molecular biology in oncology has provided insight into the remarkable molecular complexity of malignant tumors. Increasing evidence indicates that subpopulations of cells, which may manifest distinct genotypes and phenotypes or harbor divergent biological behaviors, might coexist within the same solid tumor, or between a primary tumor and its metastases (inter - and intra –tumor heterogeneity) [193, 194]. Different cancer patients, even with the same histopathological subtype of tumor, may also exhibit large patient-to-patient variability of molecular signatures. Moreover, the molecular signature may change dynamically with progression, invasion and metastasis of cancer. Tumor heterogeneity is always a significant concern and hinders the progress of personalized medicine, targeted therapy and molecular imaging. With hundreds of molecular probes available, it is not a trivial task for a surgeon to choose one that is best for a patient who is a candidate for targeted surgery. One potential solution to address the tumor heterogeneity is to use a strategy of multiplex imaging, which was recently highlighted as “the simultaneous use of two or more techniques, contrast reagents, signaling methods, or the coupling of agent and tissue properties to achieve so-called multiplex imaging is a promising approach”[195]. As discussed above, most of the current molecular probes have been designed to specific driver molecules, pathways or genes. Theoretically, a tumor's unique molecular driver profile greatly helps to predict its invasive and metastatic potential, its tendency to evade immune surveillance, and its potential therapy response.

An example of multiplex imaging is molecular imaging of multiple tumor targets using novel probes. Dual receptor targeted imaging has been realized by means of immunofluorescence imaging using IRDye 800CW dye labeled antibodies separately targeting VEGF (Bevacizumab) or HER2 (Trastuzumab). With the mixed immunofluorescence imaging probes, tumor-specific detection was improved dramatically. The results showed that tumor lesions at even the submillimeter level were detected in real-time intraoperative imaging in tumor models of intraperitoneal dissemination [92]. However, because the emission peak of a fluorescent dye is relatively broad, it is technically difficult to differentiate multiple fluorophores. Therefore it remains a challenge to image many targets simultaneously when conventional dyes are used. To address this, nanoparticles such as QDs have been proposed as a promising strategy for multiplex imaging. In comparison with fluorescent dyes, QDs have size-tunable light emission and the ability to excite multiple fluorescent colors simultaneously[196]. Smaller QDs (<2 nm in diameter) can produce light with blue emission wavelengths, while larger QDs (>7 nm in diameter) produce light red emission wavelengths [197]. Another valuable property of QDs for imaging is the wide QD stokes shift. Depending upon the excitation wavelength, the difference between the excitation peak wavelength and emission peak wavelength can be as large as 300–400 nm. This large stokes shift in combination with the broadband absorption and sharp emission peaks of QDs make it possible to perform multiplex imaging applications in which one light source is used to simultaneously excite multicolor QDs. Therefore, by conjugating different antibodies or biomolecules to the surface of QDs, the protein level of several biomarkers and post-translational modifications may be detected and quantified simultaneously in the same tumor. Multi-targeting fluorescent probes based on nanostructures have been developed to detect various aberrant biomarkers in cancerous cells and tissues in vitro, in blood and directly on human tissue biopsies [44, 198–200]. With the ability to simultaneously detect multiple related biomarkers in a tumor, it is expected that QDs can be useful in whole-body multiplexed cancer biomarker imaging in vivo. This will identify the prominent molecular profile in different patients with the same histopathological subtype of tumor, or at different stages of tumor's evolution[200]. Therefore, this technique can eventually become an effective remedy for the problem of tumor heterogeneity. Furthermore, once the issue of QD toxicity is overcome, this technology will advance even further, which will help to make personalized medicine and targeted surgery a reality.

7.Targeted surgery and “systems molecular imaging”