Abstract

Biodistribution data to-date using 111In- ibritumomab tiuxetan has been initially obtained in patients with <25% lymphomatous bone marrow involvement and adequate hematopoietic synthetic function. In this article we present the results of an analysis of the biodistribution data obtained from a cohort of patients with extensive bone marrow involvement, baseline cytopenias, and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). Thirty nine patients with diagnosis of B-cell lymphoma or CLL expressing the CD20 antigen, who had failed at least one prior regimen, and had evidence of persistent disease were included in this analysis, however only 38 of these completed the treatment. Semiquantitative analysis of the biodistribution was performed using regions of interest (ROI) over the liver, lungs, kidneys, spleen and sacrum. The observed interpatient variability including higher liver uptake in 4 patients is discussed. No severe solid organs toxicity was observed at the maximum administered activity of 1184 MBq (32 mCi) 90Yibritumomab tiuxetan. After accounting for differences in marrow involvement, patients with CLL exhibit comparable biodistributions to those with B-NHL. We found that the estimated sacral marrow uptake on 48 hour images in patients with bone marrow involvement may be an indicator of bone marrow involvement. There was no correlation between tumor visualization and response to treatment.

These data suggest that the imaging step is not critical when the administered activity is below 1184 MBq (32 mCi). However our analysis confirms that the semiquantitative imaging data can be used to identify patients at risk for liver toxicity when higher doses of 90Y- ibritumomab tiuxetan are used. Patients with CLL can have excellent targeting of disease by 111Inibritumomab tiuxetan, indicating potential efficacy in this patient population.

Introduction

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma is the seventh most common cancer in males and females in the United States and the incidence increases with age, with a median age of diagnosis of 65 (1). For patients with co-morbidities or advanced age who have fewer effective treatment options and little chance for cure, non-myeloablative allogeneic transplantation (NMAT) has been introduced as an alternative treatment and has the potential to eradicate disease when used in conjunction with chemotherapy and immunotherapy (2).

Radioimmunotherapy (RIT) using the anti-CD20 radioimmunoconjugate yttrium-90 (90Y) ibritumomab tiuxetan was approved for relapsed or refractory low-grade or follicular B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (3). In 2009, 90Y -ibritumomab tiuxetan at standard low-dose of 14.8 MBq/kg (0.4 mCi/kg) has been approved for consolidation in patients who achieved a partial or complete response to first-line chemotherapy (3). There is also a growing interest in the development of newer protocols for higher dose of 90Y- ibritumomab tiuxetan in some trials up to 55.5MBq/kg (1.5 mCi/kg).

The primary toxicity associated with 90Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan in the standard doses is a transient delayed myelosuppression (4, 5, 6). However, this is not correlated with the red marrow or total body radiation absorbed dose estimates or with effective half-life or residence time of 90Y- ibritumomab tiuxetan in blood, suggesting that hematologic toxicity is dependent on bone marrow reserve (7, 8, 9). Based on these findings, it is considered safe to administer 90Yibritumomab tiuxetan in standard low dose without pre-treatment dosimetry (10, 11). However, pre-treatment imaging with 111In- ibritumomab tiuxetan was used for clinical purposes until recently in the USA (and is still used in Switzerland and Japan) to guard against the hypothetical risk of altered biodistribution of the radioimmunoconjugate which could cause unintended end organ damage. Preclinical studies have demonstrated that the biodistribution of 90Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan is adequately predicted by the biodistribution of 111In- labeled antibody (12) since 90Y -ibritumomab tiuxetan cannot be used for imaging because it is a pure beta emitter. Nevertheless, biodistribution data to-date has been primarily limited to patients with <25% lymphomatous bone marrow involvement and adequate hematopoietic synthetic function. Furthermore, biodistribution data in the related B-cell malignancy chronic lymphocyic leukemia (CLL) are limited.

This study was conducted as part of an on-going prospective phase II trial evaluating a conditioning regimen of 90Y -ibritumomab tiuxetan to augment anti-tumor activity followed by fludarabine and low dose total body irradiation (TBI) to ensure engraftment prior to matched related or unrelated allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in such high-risk patients with persistent relapsed or refractory lymphoid malignancies (13). This trial included a unique patient population with extensive marrow involvement, baseline cytopenias, and CLL.

Given the fact that solid organs toxicity especially hepatotoxicity is a concern with this growing interest in the development of new protocols which include higher doses of 90Y- ibritumomab tiuxetan (in some trials up to 55.5MBq/kg), in this paper we proposed a semiquantitative method for assessment of 111In- ibritumomab tiuxetan biodistribution for a more objective detection of patients at risk for developing postradiation toxicity. This is important in high-dose 90Yibritumomab tiuxetan studies protocols which do not include a dosimetric approach but the imaging step is still performed.

The relationship between visualization of the cancerous tissue and response to treatment was also assessed (second aim).

Third aim of the paper was evaluation of the sacral uptake (obtained from 111In- ibritumomab tiuxetan biodistribution images) and the capacity to predict bone marrow involvement by disease.

Fourth aim of this paper was to assess if there are significant differences between CLL patients and the rest of the patients (non-HL patients) and between the group of low bone-marrow reserve patients and the rest of the patients. We hypothesized that there are significant differences in biodistribution between these groups which will have an impact in identifying the group of patients that will need dosimetry or at least imaging step before treatment especially in high – dose 90Y- ibritumomab tiuxetan protocols.

Patients and methods

Eligibility

Patients included in this retrospective analysis were part of a clinical trial (approved by the FHCRC Institutional Review Board Protocol FHCRC 1726) and were 18 years or older, had a histologically confirmed diagnosis of B-cell lymphoma or CLL expressing the CD20 antigen, and failed at least one prior regimen of systemic therapy. Histologies included: diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) (14 patients, including 7 that had transformed from indolent disease), chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic leukemia (CLL/SLL) (10 patients), mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) (6 patients), follicular lymphoma (FL) (6 patients), hairy cell leukemia HCL (1 patient), and marginal zone lymphoma (MZL) (1 patient). CLL/SLL,FL,HCL and MZL were considered indolent. They all had evidence of persistent disease and were excluded from the clinical trial if they had major organ dysfunction, had received systemic anti-lymphoma therapy within 30 days of the 90Y- ibritumomab tiuxetan treatment, had active central nervous system tumor involvement, an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status >2, had active infection, or were in complete remission. Patients that had received a prior murine antibody were required to have no evidence of human anti-mouse antibody (HAMA) formation. From the total of forty-five patients with advanced B-NHL which were consented for this trial 5 patients did not complete the therapy (including one patient with altered 111In- ibritumomab tiuxetan biodistribution as detailed below). We analyzed biodistribution for 38 patients included in this clinical trial (2 patients from the 40 patients which completed the therapy were excluded from the biodistribution analysis given the fact that the archived gamma camera images were not available). Biodistribution analysis was made also for one patient excluded from the trial due to the pattern of biodistribution but could not be included in the evaluation of the significance of tumor uptake given the fact that this patient did not complete the study.

Treatment plan

Briefly, on day -21 before transplant patients received 250 mg/m2 of the monoclonal antibody rituximab (unlabeled chimeric Mab) followed by 175 MBq (5 mCi) of 111In- ibritumomab tiuxetan as previously published (5,13). A minimum of one gamma camera image was obtained (24 and/or 48 hours) to confirm the expected biodistribution of the radiotracer (from 38 patients 4 did not have 48 hour images acquired and other 2 patients did not have 24 hour images acquired). On day -14 before the transplant, 250 mg/m2 of rituximab was administered prior to the therapy with 14.8 MBq/kg (0.4 mCi/kg) of 90Y–ibritumomab tiuxetan (with a maximum administered activity of 1184 MBq/32 mCi). There was no reduction of administered activity for pre-existing cytopenias. The remainder of the conditioning and allogeneic transplant was carried out as previously published (please refer to the previously published article regarding this trial Gopal et al. ref 13). The overall treatment schema is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Treatment schema. CSP=cyclosporine, MMF=mycophenolate mofetil

Image analysis

After 185 MBq (5 mCi) of 111In- ibritumomab tiuxetan injection, 24 and /or 48 hour planar whole body scans were performed in anterior and posterior projections at a speed of 10 cm/min (20 minute scan) using a medium energy collimator, a 256 × 1024 computer acquisition matrix and acquisition photo peak settings of 172 and 247 keV with 20% windows. Scans were acquired using a GE Millennium gamma camera (GE, Milwaukee, USA).

For the trial purpose, the evaluation of biodistribution post 111In- ibritumomab tiuxetan administration was qualitative by visual assessment only. The standard criteria for normal and altered biodistribution described in Zevalin prescription information (3) was not used since the CLL patients were included in the study and the initial criteria was made for non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

The semiquantitative analysis was performed retrospectively, for each patient, using regions of interest (ROI) manually drawn over the liver, lungs, kidneys, spleen, sacrum. ROI counts (background corrected) were obtained in the anterior and posterior views from which the square root of their product was calculated for each ROI at 24 and 48 hours available. The whole body counts were obtained separately at 24 and 48 hours (using geometric mean for the whole body counts obtained from the anterior and posterior images). The percentage of counts for the regions of interest from the whole body counts was then calculated.

For the sacral uptake analysis, the counts were obtained only from the posterior acquired images (given the more superficial location of the sacral marrow). A region of interest (ROI) was drawn around the sacrum with exclusion of any apparent activity in the urinary bladder. Comparison of sacral uptake between different group of patients (with and without bone marrow involvement) was performed.

Results

Patient characteristics

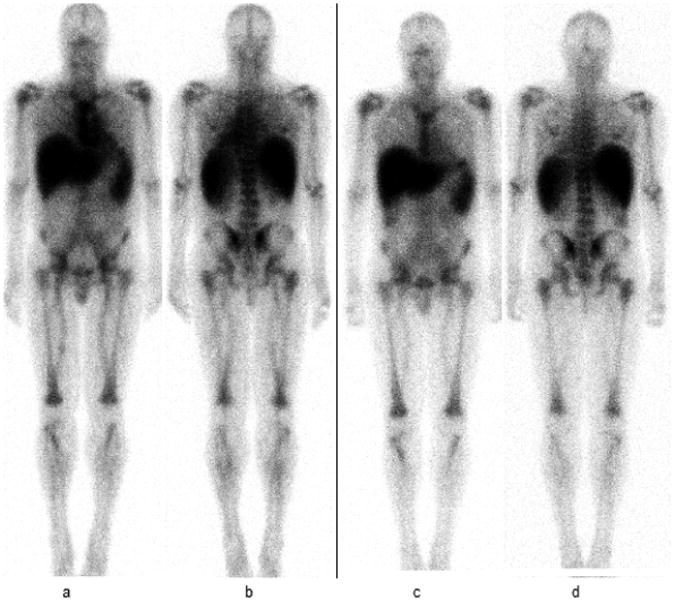

Thirty eight patients (from a total of 40 who completed the therapy on the research protocol) were included in this biodistribution analysis, as detailed in the patient eligibility section. An additional one patient from the five who initially consented but did not complete the therapy was excluded due to altered 111In- ibritumomab tiuxetan biodistribution (on 48 hours images there was intense tracer uptake in the liver and only faint visualization of the spleen) (Figure 2). Baseline characteristics of these 38 evaluable patients are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 2.

52 year old male with history of CD20 positive CLL/SLL which was excluded from the trial due to safety reasons concerning liver toxicity.

Whole body planar anterior image (a) and posterior image (b) obtained at 24 hours show intense radiotracer uptake in the liver and only faint uptake in the spleen and kidneys. At 48 hours images (c and d) there is uptake in the liver without significant uptake in other organs worrisome for progressive accumulation of radiotracer in the liver for the next several days, concerning for liver toxicity. Uptake values were 55% at 24 hours and 60% at 48 hours.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics for the group included in the study.

| Demographics | Total |

|---|---|

| No of patients | 38 |

| Age, median (range) | 59 years (29-68 years) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 13 |

| Male | 35 |

| Y-90 dose (MBq), median(range) | 1143 (802.9 –1206.2) |

| BM involvement on biopsy | 15 (42.1%) |

| BM involvement > 25% | 10 (26.3%) |

| Percent of BM involvement, median (range) | 57% (3%-95%)* |

| Ann Arbor Stage III/IV | 28 out of 28 patients with NHL (100%) |

| Median prior regimens (range) | 6(3-12) |

| Prior autologous transplant | 17 (44.7%) |

| Splenectomy | 3 |

| Baseline platelet count less 25,000/μL | 7 (18.4 %) |

| Histology | |

| Indolent (CLL, FL, MZL, HCL) | 18 |

| De-novo Diffuse Large B-cell | 7 |

| Transformed Diffuse Large B-cell | 7 |

| Mantle Cell | 6 |

Median and range of bone marrow involvement included only those 15 patients with a positive bone marrow biopsy.

Biodistribution data

In order to obtain a more objective information regarding biodistribution a semiquantitative evaluation of the uptake in the liver, lungs, kidneys, spleen, and sacrum was obtained (as described above) and is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Percentage of counts from the whole body counts obtained for regions of interest drawn over the liver, lungs, kidney, spleen, and sacrum for the 38 patients treated with 90Y- ibritumomab tiuxetan.

| Lungs 24h | Lungs 48h | Kidneys 24h | Kidneys 48h | Liver 24h | Liver 48h | Spleen 24h | Spleen 48h | Sacrum 24h | Sacrum 48h | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Max | 6.4 | 5 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 62 | 32.75 | 10.75 | 14.09 | 4 | 3.2 |

| Min | 1.3 | 1.5 | 0.22 | 0.7 | 5.3 | 6 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Median | 3.8 | 2.9 | 1.9 | 1.885 | 9.25 | 9.8 | 1.9 | 2.2 | 1.2 | 1.35 |

| Mean | 3.75 | 3.10 | 1.89 | 1.84 | 10.97 | 11.09 | 2.97 | 3.11 | 1.46 | 1.53 |

Liver uptake presented a wide range of values between 5.3% and 62%; however further analysis of the data show that in fact the liver uptake has a narrow range for the patients included in the study with the exception of 4 patients out of 39 patients who underwent evaluation of biodistribution by imaging (including one patient who did not finished the study due to high liver uptake). The range of uptake at 24 hours is 8.5 % +/- 3.2 % and at 48 hours 11% +/-5 % if we exclude those 4 patients who from the statistical point of view are outliers (liver uptake higher than 20%). These findings are better illustrated in the Figure 3. There was no prior murine treatment in any of these 4 patients to suspect HAMA antibodies. Not significant liver toxicity was seen posttreatment in any of the patients who were treated. From these 4 patients one patient had CLL/SLL with liver uptake 26.49 % and 32.7% at 24 respective 48 hours; one patient with mantle cell lymphoma (Figure 4) had liver uptake 62% at 24 hours (48 hours images were not available), one patient with diffuse large B cell lymphoma had liver uptake 13.2% and 20.15% at 24 and respective 48 hours; this last patient had prior splenectomy. A 4th patient from the group of patients with high liver uptake was a patient with CLL and calculated liver uptake of 55% and 60% at 24 and respective 48 hours. This patient was excluded from the study due to safety reasons given the intense liver uptake without significant visualization of other organs, worrisome for progressively increased uptake in the liver over the next several days since there was no significant uptake in other organs (Figure 2).

Figure 3.

Figure illustrating percentage of liver uptake values at 24 and 48 hours after administration of 111In- ibritumomab tiuxetan for the patients included in this analysis. Higher than 20 % liver uptake was seen in 4 patients one with 62% liver uptake at 24 hours, one with 26.5 % and 33% at 24 and respective at 48 hours. A 3rd patient with 55% and 60% liver uptake at 24 hours and respective 48 hours who was excluded from the trial. A 4th patient had 13.15 % at 24 hours however at 48 hours percentage of liver uptake increased to 20.15%.

Fig 4.

61 year-old female with mantle cell lymphoma with splenomegaly, lymphadenopathy and 40% bone marrow involvement. Whole body planar anterior image (a) and posterior image (b) show intense liver uptake on 24 hours images with 62% of liver uptake, on our quantification, yet no severe liver toxicity was noted post-treatment with 90Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan.

Prior splenectomy did not clearly impact the liver uptake (the median value for liver uptake after 48 hours was 16% with a range of 8.5% to 20.15% whereas the median value for nonsplenectomized patients was 9.6% with a range of 6% to 32.7%) however there were only 3 patients with prior splenectomy so data is limited.

Likewise, the kidneys and lung uptake varied between 0.22% and 3.1%, and 1.3 % and 6.4%, and no abnormal kidneys and lung uptake was identified by visual assessment. The patient with lung uptake of 6.4% at 24 hour and 5 % at 48 hours had resolving pulmonary edema (with interstitial thickening and centrilobular nodularity) at the time of imaging however by visual assessment the uptake at 24 hours was significantly lower than the cardiac blood pool. There were no cases considered to have abnormal kidney uptake. Splenic uptake varied between 0.6 and 14.06%.

Table 3 portrays the percentage of 111In- ibritumomab tiuxetan uptake in the sacrum for different groups of patients (with and without bone marrow involvement by lymphoma). The t-test analysis of 48-hour images showed that the group of patients with bone marrow involvement has higher bone marrow uptake values (calculated percentage of counts over the sacrum) when compared to the group of patients without bone marrow involvement (p = 0.005). An example of intense bone marrow uptake is shown in Figure 5. Importantly, none of the 11 patients with high bone marrow uptake on qualitative visual analysis had a negative bone marrow biopsy. In the 24-hour images, the average and median values for sacrum uptake was also higher for the group with bone marrow involvement compared to the group without bone marrow involvement, though the difference did not achieve statistical significance (p = 0.18).

Table 3.

Comparison of sacrum uptake according to bone marrow involvement

| Bone marrow involvement | Negative BM (23 patients) | Up to 25% BM involvement (5 patients) | >25% BM involvement (10 patients) | p-value* | p-value** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Sacrum uptake 24h | Mean 1.31 | Mean 1.432 | Mean 1.93 | 0.18 | 0.18 |

| Median 1.1 | Median 1.2 | Median 1.75 | |||

| Range 0.5-3.8 | Range 0.76 – 2.6 | Range 0.8-4 | |||

|

| |||||

| Sacrum uptake 48h | Mean 1.24 | Mean 1.66 | Mean 2.237 | 0.018 | 0.005 |

| Median 1.1 | Median 1.3 | Median 2.4 | |||

| Range 0.5-2.1 | Range 1.1-2.8 | Range 0.5-3.2 | |||

BM, bone marrow

p-values represents comparisons between the group with no bone marrow involvement and >25%.

p-values represents comparison between the group with no bone marrow involvement versus any bone marrow involvement (i.e., all 15 patients with positive bone marrow).

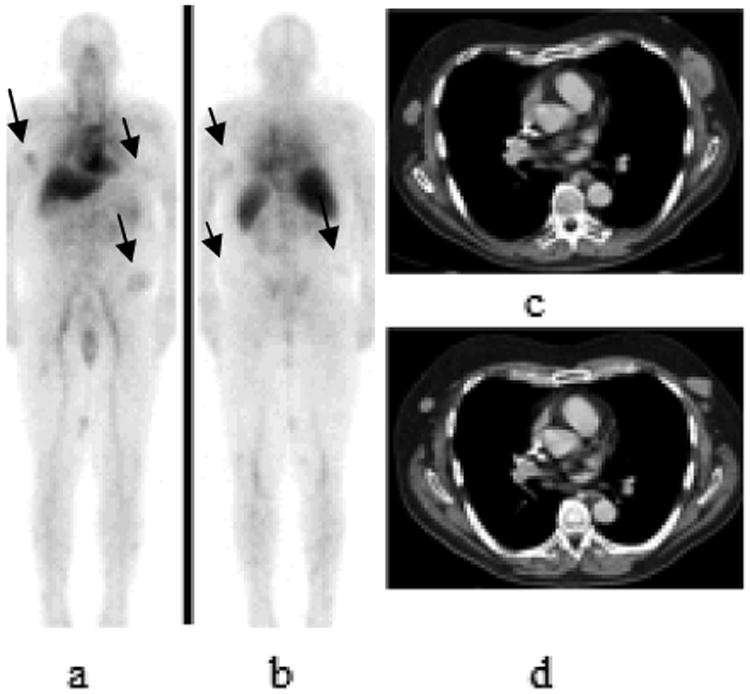

Figure 5.

111In- ibritumomab tiuxetan images at 24 (a and b) and 48 hours (c and d) in a patient with CLL and 95% bone marrow involvement on biopsy and sacral uptake of 2.3%. Intense uptake associated with bone marrow (uptake seen in the skull, sternum, ribs, scapulae, vertebral spine, pelvic bones including sacrum, proximal appendicular skeleton-humeri and femurs) is noted.

The only patient whose bone marrow was heavily infiltrated (50% bone marrow involvement) yet not imageable had CD20 absent as measured by flow cytometry, yet identified intracellularly by immunohistochemistry, potentially due to blocking of surface CD20 antigens by prior rituximab.

No statistically significant difference in sacral uptake values was noted for the group of 7 patients with thrombocytopenia compared to the rest of the patients (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of sacrum uptake between the group of 7 patients with platelets less than 25,000/μL and the rest of the patients.

| Platelets | Less than 25,000/μL (7 patients) | More than 25,000/μL (31 patients) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| 24h | Mean 1.87 | Mean 1.36 | 0.26 |

| Median 1.4 | Median 1.2 | ||

| Range 0.8- 4 | Range 0.5 – 3.8 | ||

|

| |||

| 48h | Mean 1.74 | Mean 1.49 | 0.58 |

| Median 1.7 | Median 1.35 | ||

| Range 0.5- 2.9 | Range 0.5 – 3.2 | ||

A separate analysis was performed for the unique subgroup of 10 CLL patients, 9 of whom had bone marrow involvement by biopsy, with 6 having over 25% marrow disease and 6 being imageable on 111In- ibritumomab tiuxetan images (evaluated by visual analysis). The average and median values of sacrum uptake were higher for the CLL subgroup compared to the rest of the patients. While this difference was not statistically significant, it correlated with the known bone marrow involvement in these patients (Table 5).

Table 5.

Comparison of sacrum uptake between the group of patients with CLL and the patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma and positive bone marrow involvement.

| Histology | CLL (10 patients) | Others (28 patients) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| 24h | Mean 1.73 | Mean 1.38 | 0.40 |

| Median 1.25 | Median 1.2 | ||

| Range 1.2 – 4 | Range 0.5 - 3.8 | ||

|

| |||

| 48h | Mean 1.94 | Mean 1.38 | 0.1 |

| Median 2 | Median 1.3 | ||

| Range 0.5-3.2 | Range 0.5 -2.9 | ||

Liver uptake values were not higher in CLL patients compared to the rest of the group at 24 hours (p= 0.43) and at 48 hours (p= 0.25).

These data imply that after taking into account differences in marrow involvement, patients with CLL exhibit comparable biodistributions to those with B-NHL.

There was no correlation between tumor visualization and response to treatment. Importantly, the CLL population, which typically has low CD20 surface density, can still be effectively targeted by 111In- ibritumomab tiuxetan. In the 10 patients with CLL, 4 have visible tumors, all of them with bulky disease (larger than 5 cm). There were a total of 9 patients with imageable tumor visualized in the non-Hodgkin lymphoma group (non-CLL), with bulky disease in all but 2 patients (Figure 6). Relationship with progression of the disease (PD), complete response (CR), complete response undocumented (CRu) and stable disease (SD) is show in Figure no 7. From a total of 13 patients with tumor visualization the follow- up by CT scan at 3 months show: 2 patients with stable disease (versus 5 from the group of 25 patients which did not have tumor visualization), 5 patients with partial response (versus 11 from the group which did not have tumor visualization), 2 patients with progression of the disease (versus 6 from the group which did not have tumor visualization), 4 patients with CR/CRu (versus 8 from the group which did not have tumor visualization). However, 56 % percent of patients with ≥5cm masses could be imaged as compared to 18% in those with disease <5cm.The median bulk of visualizable disease was 6.4 cm as compared to 4.2 cm for those that were non-imageable.

Figure 6.

68 year old patient with history of CLL with Richter transformation from B lineage chronic lymphocytic leukemia to diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with 111In- ibritumomab tiuxetan uptake seen on lymphoma lesions. 111In- ibritumomab tiuxetan whole body planar 48 hours images anterior and posterior views (arrows in a and b) show uptake in subcutaneous nodules consistent with lymphoma involvement. Axial contrast- enhanced CT images show multiple subcutaneous masses. This patient presented with progression of the disease at 3 months posttreatment with increase in size of subcutaneous lesions on follow-up CT scan (image c) compared to pretreatement CT scan (image d).

Figure 7.

Assessment of relationship between response to treatment and tumor visualization

Regardless of the uptake percentage in different organs there were no significant side effects except for myelosuppression. The median number of days after transplant to a neutrophil >500/μL was 13 (range 0 to 28) and platelets >50,000/μL was 9 (range 0 to 130).

Discussion

There were a couple of objectives of the study presented in this article: one was to assess the pattern of 111In- ibritumomab tiuxetan biodistribution, another one to assess the relationship between the visualization of the tumors and response to treatment. Assessment of the bone marrow uptake (estimated by sacral uptake on 111In- ibritumomab tiuxetan images) and the capacity to predict bone marrow involvement by disease was also performed. We also performed subset analyses regarding biodistribution on 3 unique subgroups of patients which have not previously been described in this context: patients with CLL, patients with extensive bone marrow involvement, and the third group of patients with profound cytopenias (thrombocytopenia).

As shown in the result section and Table no 2 there is a relatively narrow range of percentage uptake for the kidneys and lungs. None of the patients included in the study were considered to have abnormal distribution in regard to kidneys and lungs uptake. The evaluation of liver and spleen uptake is very important since after bone marrow toxicity the highest risk involves spleen followed by liver (8, 14). Recently published study on a small number the patients show a similar result but with liver absorbed dose higher than the spleen however the analysis was performed with 89Zr-ibritumomab tiuxetan (15). Therefore, the most important toxicity after the myelosupresion is liver toxicity given the fact that splenic toxicity is not as important as liver toxicity and is not considered a limiting factor. Statistical analysis of the liver uptake show 4 patients with higher liver uptake than the rest of the group (outliers). Our results show a range of uptake at 24 and 48 hours for the liver relatively homogeneous for our group of patients at 24 hours being 8.5 % +/- 3.2 % and at 48 hours 11% +/-5 % (excluding outliers values). The patients with uptake values (4 patients as presented in the results section) that are outliers are potentially at a higher risk of liver toxicity. Although one patient was excluded from the study, the other 3 were treated and did not developed any liver toxicity. By our method of calculation these patients who have a relative percentage of liver uptake higher than 20 % at 48 hours present a higher risk of liver toxicity compared to the rest of the patients in protocols that include high-dose Y90-ibritumomab radiotherapy.

There was a slightly wider range for splenic uptake at 24 hour 0.7 %- 10.75 %and at 48 hours (0.6 %– 14.9 %) however splenic toxicity is not as important as liver toxicity and was not considered a limiting factor.

Patients included in this trail did not have significant side effects other than myelosupression, although one patient was excluded from the study before being treated for safety reasons due to progressive radiotracer accumulation in the liver, as mentioned above. These findings support the prior report by Kylstra (16) which also suggested that there is no additional information gained regarding the risk of toxicity from 111In -ibritumomab tiuxetan images acquired before the treatment for the low-dose 90Y- ibritumomab tiuxetan (14.8 MBq/kg, max 1184 MBq). On the other hand, dosimetry performed in a clinical trial including patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma using higher 90Y- ibritumomab tiuxetan doses (17- Arico et al) presented 2 cases of high accumulation of radiotracer in the liver with an unfavorable risk benefit ratio; in this study one of these patients would have received a radiation absorbed dose higher than 20 Gy even if treated with 14.8 MBq/kg (21). Attention to the liver toxicity is drawn by other studies also (8, 18).

Until recently, 111In- ibritumomab tiuxetan imaging was required in the US prior to 90Yibritumomab tiuxetan radioimmunotherapy to ensure the expected biodistribution. In November 2011, the FDA approved removing the 111In- ibritumomab tiuxetan imaging step, based on additional analysis of clinical studies and post-marketing surveillance of patient toxicities (16). Presented analysis of data from 253 patients by Kylstra et al. showed that the In-111 imaging and biodistribution scan were not reliable predictors of altered 90Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan biodistribution or of possible side-effects for the low-dose 90Y- ibritumomab tiuxetan treatment (16). Also the same study mentioned that three patients (from 233 patients reviewed by a trained reader in central review) with true altered biodistribution who had proceeded with 90Yibritumomab tiuxetan treatment based on a scan result locally judged normal, showed safe and efficacious outcomes within the range of those shown by rest of the patients on that study (16). According to this study the incidences of bone marrow toxicity failure were similar in regions that did and did not require the Indium-111 bioscans (USA, Switzerland, and Japan versus Rest of World) (3 % vs. 4%) (16). Our study also shows that, regardless of the semiquantitative uptake measurements in different organs (liver, lungs, spleen, kidneys), there were no corresponding significant side effects noted except for bone marrow toxicity, at administered activity of Y-90 ibritumomab tiuxetan of 1184 MBq (32 mCi) or less. For example, one patient in our study with 62% uptake in the liver did not develop severe liver toxicity posttreatment (Figure 4). For this patient there was an increase in liver enzymes (aspartate aminotransferaseGOT and alanine aminotransferase -GPT) 4 weeks post 90Y- ibritumomab tiuxetan administration and respective 2 weeks post allogenic bone marrow transplant which resolved in 10 days and there was not a specific pattern to suggest radiation induced liver toxicity. There was no long term change in the liver morphology to suggest fibrosis and no change in the liver function. Patient survived for 31 months and died due to disease progression.

There are prior publications which showed that red marrow dosimetry may be accurately determined using sacral scintigraphy as an alternative method to estimate the red marrow dose (19). In our study, we did not evaluate the relationship between bone marrow uptake and marrow toxicity, since previous studies have shown that the toxicity depends more on the bone marrow reserve than on the radiotracer distribution (7, 8, 9, 11). Nevertheless, we analyzed the ability to predict bone marrow involvement by lymphoma based on image analysis.

For patients with positive bone marrow involvement included in our study, we found higher sacral uptake values compared to the group of patients without bone marrow involvement, however statistical significance was obtained only for 48 hours images. This suggests that high sacral uptake could be an indicator of bone marrow involvement by disease. Prior studies also showed similar results (19, 20). This information is important and can be used as a surrogate in cases with negative bone marrow biopsy results and a high sacral uptake. Such a finding may be suggestive of bone marrow involvement and thus may warrant another bone marrow biopsy (for instance in the iliac bone but in a slightly different region). At 24 hours there was no statistically significant correlation between the sacral marrow uptake and bone marrow involvement. The absence of statistical significance at 24 hours is likely due to the fact that the normal bio-distribution of 111In- Ibritumomab tiuxetan shows significant blood pool activity during the initial period likely because of circulating normal B lymphocytes. Slower localization in other tissues is the hallmark of many radioimmunoconjugates especially those that target normal cellular antigens such as CD20.

Separate analyses were also performed for two additional subgroups of patients: one with CLL and another one in patients with thrombocytopenia. As per the review of literature, this is the first study which discuss 111In- ibritumomab tiuxetan biodistribution in patients with CLL. Interestingly, CLL, which typically has low expression of CD20 (21), can still be targeted by the anti-CD20 radioimmunoconjugates such as 90Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan and 111In- ibritumomab tiuxetan. In 10 patients from our study with CLL, 4 had visible tumors, all with bulky tumor or a conglomerate of lymph nodes larger than 5 cm. It is also noteworthy that the CLL patients with positive bone marrow involvement had intense bone marrow visualization on 111In- ibritumomab tiuxetan images except one patient. The comparison of the sacral uptake in the CLL group and those with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma shows a higher median and average values for CLL patients. This can be explained by the fact that leukemic patients have more diffuse and higher degree of bone marrow involvement (based on bone marrow biopsy results). Since patients with CLL may present with diffuse infiltration of the liver (2 of the cases of high liver uptake considered “outliers” correspond to patients with CLL) we analyzed the correlation between the liver uptake between this group and the rest of the patients. However there was no statistical significance at 24 hours (p=0.43) and at 48 hours (p= 0.25) to prove that patients with CLL have higher percentages of liver uptake therefore a higher risk for liver toxicity compared to non-Hodgkin lymphoma patients. This can be explained by the fact that when there is liver involvement there is likely involvement of other solid organs that may affect the relative overall uptake (and ultimately the absorbed dose) in the liver.

In our patients, all cases of intense bone marrow uptake could be explained by the high degree of bone marrow involvement, though HAMA measurement was not obtained in all of the patients. Murine monoclonal antibodies like ibritumomab elicit human anti-mouse antibody (HAMA) which usually does not cause significant adverse reactions, however can significantly alter the murine antibodies pharmacokinetics through the formation of antibody/HAMA complexes therefore limiting the effectiveness of re-treatment if necessary. These complexes are quickly removed by the reticuloendothelial system which decreases circulating levels of antibody and impairs tumor targeting (22). In our patients, all cases of intense bone marrow uptake could be explained by the high degree of bone marrow involvement, though HAMA measurement was not obtained in all of the patients.

There was no correlation between visualization of tumor uptake and response to treatment. A possible explanation is that larger lesions are easier to be visualized given the fact that 56 % percent of patients with ≥5cm masses could be imaged as compared to 18% in those with disease <5cm and also the fact that the median bulk of visualizable disease was 6.4 cm as compared to 4.2 cm for those that were non-imageable. Although this can be partially explained by the size of tumor, a patient from this study with CLL and the largest bulky mass 18.55 cm did not have tumor visualization but showed partial response at 3 month. Another explanation for the lack of correlation between tumor visualization and response to treatment could be the fact that the protocol included also chemotherapy and total body irradiation which also contribute to response to therapy.

Conclusions

There were no significant side effects noted in patients treated with standard low-dose 90Yibritumomab tiuxetan except for the anticipated bone marrow toxicity, indicating that the imaging step may not be critical in the range of radioactivity used clinically for therapy (i.e. ≤ 1184 MBq/32 mCi). Thus we feel that the semiquantitative imaging data can be used to identify patients at risk for liver toxicity when higher doses of 90Y- ibritumomab tiuxetan are used. For patients with bone marrow involvement, the percentage of sacral uptake on images acquired at 48 hours correlates with the presence of bone marrow involvement, indicating that sacral uptake could be a robust indicator of bone marrow involvement by B-cell malignancies. This information is important and can be used in situations where bone marrow biopsy results are negative but there is a high sacral uptake on imaging which may be suggestive of bone marrow involvement. This could be used ultimately to guide decisions regarding the benefits of repeating the bone marrow biopsy and the safety of proceeding to the 90Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan treatment.

Another interesting observation in our study is that patients with CLL can have excellent targeting of disease by 111In-ibritumomab tiuxetan, opening up the potential for its use in that disease type. After accounting for differences in marrow involvement, patients with CLL exhibit comparable biodistributions to those with B-NHL.

There was no correlation between tumor visualization and response to treatment.

Patients who are being considered for marrow supportive regimens, will benefit from imaging and possibly prospective organ based dosimetry to avoid potentially serious complications. Additional patients and longer follow-up would help establish the role of this therapeutic regimen in these clinical situations that have limited options available.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: SCOR Grant 7040 from the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, Lymphoma Research Foundation Mantle Cell Lymphoma Research Initiative, Biogen-IDEC, CLL Topics, the Mary A. Wright and Frederick Kullman Memorial Funds, and philanthropic gifts from Frank and Betty Vandermeer. AKG is a Scholar in Clinical Research for the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society. Financial support provided also by NCI P01CA44991, NCI 632 R01CA076287, NCI R01 CA138720, The Hutchinson Center/University of Washington Cancer Consortium Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA015704, PO1 CA 78902 and K12 CA076930.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest:

Dr. D. Maloney has received funding from Roche/Genentech and Spectrum Pharmaceuticals.

Dr. A.Gopal has received funding from Spectrum Pharmaceuticals.

References

- 1.Leukemia and lymphoma society Facts 2010-2011.

- 2.Khouri IF, McLaughlin P, Saliba RM, et al. Eight year experience with allogeneic stem cell transplantation for relapsed follicular lymphoma after nonmyeloablative conditioning with fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab. Blood. 2008;111(12):5530–5536. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-136242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zevalin (90-Y ibritumomab tiuxetan) prescribing information. Available at: http://patient.cancerconsultants.com/druginserts/Ibritumomab_tiuxetan.pdf.

- 4.Hendrix CS, de Leon C, Dillman RO. Radioimmunotherapy for Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma with yttrium 90 ibritumomab tiuxetan. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2002;6(3):144–148. doi: 10.1188/02.CJON.144-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Witzig TE, White CA, Gordon KI, et al. Safety of yttrium-90 ibritumomab tiuxetan radioimmunotherapy for relapsed low-grade follicular, or transformed non-Hodgkin lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1263–1270. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wiseman GA, Gordon LI, Multai PS, et al. Ibritumomab tiuxetan radioimmunotherapy for patients with relapsed or refractory non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and mild thrombocytopenia: a phase II multicenter trial. Blood. 2002;99(12):4336–4342. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.12.4336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wiseman GA, White CA, Stabin M, et al. Phase I/II 90Y-Zevalin (yttrium-90 ibritumomab tiuxetan, IDEC-Y2B8) radioimmunotherapy dosimetry results in relapsed or refractory non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. European Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2000;27:766–777. doi: 10.1007/s002590000276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wiseman GA, Kornmehl E, Leigh B, et al. Radiation dosimetry results and safety correlations from 90Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan radioimmunotherapy for relapsed or refractory no-Hodgkin's lymphoma: combined data from 4 clinical trials. Nucl Med. 2003;44:465–474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wiseman GA, Leigh BR, Dunn WL, et al. Additional radiation absorbed dose estimates for Zevalin radioimmunotherapy. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2003;18:253–258. doi: 10.1089/108497803765036436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wiseman GA, White CA, Sparks RB, et al. Biodistribution and dosimetry results from a phase III prospectively randomized controlled trial of Zevalin radioimmunotherapy for low-grade, follicular, or transformed B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2001;39(1-2):181–94. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(01)00107-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delaloye AB, Antonescu C, Louton T, et al. Dosimetry of 90Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan as consolidation of first remission in advanced-stage follicular lymphoma: results from the international phase 3 first-line indolent trial. J Nucl Med. 2009;50(11):1837–43. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.067587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chinn PC, Leonard JE, Rosenberg J, et al. Preclinical evaluation of 90Y-labeled anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody for treatment of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Int J Oncol. 1999 Nov;15(5):1017–25. doi: 10.3892/ijo.15.5.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gopal AK, Guthrie KA, Rajendran J, et al. 90Y-Ibritumomab tiuxetan, fludarabine, and TBI-based nonmyeloablative allogeneic transplantation conditioning for patients with persistent high-risk B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2011;118(4):1132–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-324392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wiseman GA, Leigh B, Erwin WD, et al. Radiation dosimetry results for Zevalin radioimmunotherapy of rituximab-refractory non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Cancer. 2002;94(4 Suppl):1349–1357. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rizvi SN, Visser OJ, Vosjan MJWD, et al. Biodistribution, radiation dosimetry and scouting of 90Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan therapy in patients with relapsed B-cell non-Hodkin's lymphoma using 89Zr-ibritumomab tiuxetan and PET. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2012;39:512–520. doi: 10.1007/s00259-011-2008-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jelle W Kylstra. Discriminatory power of the 111-indium scan (111-In) in the prediction of altered biodistribution of radio-immunoconjugate in the 90-yttrium ibritumomab tiuxetan therapeutic regimen: Meta-analysis of five clinical trials and 9 years of post-approval safety data. Meeting: 2011 ASCO Annual Meeting Presenter: Jelle W Kylstra. Session: Lymphoma and Plasma Cell Disorders (General Poster Session)

- 17.Aricò D, Grana CM, Vanazzi A, et al. The role of dosimetry in the high activity 90Yibritumomab tiuxetan regimens: two cases of abnormal biodistribution. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2009 Apr;24(2):271–5. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2008.0541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferrucci PF, Vanazzi A, Grana CM, et al. High-activity 90Y-ibritumomab-tiuxetan (Zevalin_) with peripheral blood progenitor cells support in patients with refractory=resistant B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. Br J Haematol. 2007;139 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siegel JA, Lee RE, Pawlyk DA, et al. Sacral scintigraphy for bone marrow dosimetry in radioimmunotherapy. International Journal of Radiation Applications and Instrumentation. Part B. Nuclear Medicine and Biology. 1989;16(6):553–555. 557–559. doi: 10.1016/0883-2897(89)90070-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Juweid M, Sharkey RM, Siegel JA. Estimates of red marrow dose by sacral scintigraphy in radioimmunotherapy patients having non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and diffuse bone marrow uptake. Cancer research. 1995;55(23):5827s–5831s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Almasri NM, Duque RE, Iturraspe J, et al. Reduced expression of CD20 antigen as a characteristic marker for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Am J Hematol. 1992 Aug;40(4):259–63. doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830400404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Juweid ME. Radioimmunotherapy of B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: from clinical trials to clinical practice. J Nucl Med. 2002;43:1507–1529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]