Abstract

Nanotechnology is widely used in cancer research. Models that predict nanoparticle transport and delivery in tumors (including subcellular compartments) would be useful tools. This study tested the hypothesis that diffusive transport of cationic liposomes in 3-dimensional (3D) systems can be predicted based on liposome-cell biointerface parameters (binding, uptake, retention) and liposome diffusivity.Liposomes comprising different amounts of cationic and fusogenic lipids (10-30 mol% DOTAP or 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine,1-20 mol% DOPE or 1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane, +25 to +44 mV zeta potential) were studied. We (a) measured liposome-cell biointerface parameters in monolayer cultures, and (b) calculated effective diffusivity based on liposome size and spheroid composition. The resulting parameters were used to simulate the liposome concentration-depth profiles in 3D spheroids. The simulated results agreed with the experimental results for liposomes comprising 10-30 mol% DOTAP and ≤10 mol% DOPE, but not for liposomes with higher DOPE content. For the latter, model modifications to account for time-dependent extracellular concentration decrease and liposomesize increase did not improve the predictions. The difference among low- and high-DOPE liposomessuggestsconcentration-dependent DOPE properties in 3D systems that were not captured in monolayers. Taken together, our earlier and present studies indicate the diffusive transport of neutral, anionic and cationic nanoparticles (polystyrene beads and liposomes, 20-135 nm diameter, -49 to +44 mV) in 3D spheroids, with the exception of liposomes comprising >10 mol% DOPE, can be predicted based on the nanoparticle-cell biointerface and nanoparticle diffusivity. Applying the model to low-DOPE liposomes showed that changes in surface charge affected the liposome localization in intratumoralsubcompartments within spheroids.

Keywords: Nanoparticle, cationic liposomes, fusogenic lipid, diffusive transport, 3-dimensional tumors, spatiokinetics

INTRODUCTION

Nanotechnology, an important tool in cancer translational research, can be used to deliver diagnostics and therapeutics to tumor interstitium, cell membrane (e.g., antibodies), or intracellular compartments (e.g., RNAi)[2-4]. As nanoparticles (NP)are made of different types of materials, with different sizes, surface charges and surface modifications, there is the potential to tailor the design of NP for its intended function. Such goals can be greatly facilitated by quantitative tools that predict the NP transport and residence in tumors, including delivery to intratumoralsubcompartments where the intended targets are located.

We hypothesize that diffusive transport of NP in 3-dimensional (3D) tumor spheroids can be predicted based on two groups of parameters. The first group that describes the interactions between NP and tumor cells (i.e., NP binding, uptake and retention in cells), as theyare specific to the selected NP and selected cells, can be experimentally measured in monolayer cultures. The second group is the parameters that determine the NP diffusivity in tumor interstitium; diffusivity is calculated based on NP size and tumor microenvironment parameters(i.e., tumor cell density, interstitial void volume fraction, extracellular matrix proteins/fibers, which jointly account for the effects of 3D spheroid structure and composition).We tested the above hypothesis in an earlier study and found that this approach successfully predicted the diffusive transport oftwo NP with different surface charges and different sizes (nearly neutral liposomes at -10 mV and 130 nm diameter, and negatively charged polystyrene beads at -49 mV and 20 nm diameter), with >96% of the predicted data within the 95% confidence intervals (CI) of the experimental results[1].On the other hand, the model yielded inferior performance (60% predicted data within 95% CI of experimental results) for a cationic liposome that contained a fusogenic lipid and underwent size increase in the presence of tumor cells.

As cationic liposomes are popular carriers of drugs and gene therapeutics, we conducted the present study to determine if the inability to predict their diffusive transport was due to positive surface charge or fusogenic lipid. Cationic liposomes with varying surface charge and varying fractions of fusogenic lipid were studied, including compositions desired for in vivo applications, e.g., 5 mol% pegylated lipids to achieve stealth property, and mixture of neutral and cationic lipids (50 mol% cholesterol plus 10-30 mol% DOTAP or 1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium propane)that has been used in clinical studies [5]. The content of fusogenic lipid DOPE (1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine), which destabilizes the endosomal membrane and promotes release of nucleic acid[6], was varied from 1 to 20 mol%. We further evaluated model modifications to account for the time-dependent changes in extracellular liposome concentrations and liposome sizes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Overview

We (a) established the governing equations for liposome transport and interactions with cells in spheroids, (b) measured the liposome-cell biointerface parameters in monolayer cultures, (c) calculated the effective liposome diffusivity in spheroid interstitium, (d) used the equations and model parameters to simulatethe diffusive transport of cationic liposomes in 3D systems, (e) experimentally measured the liposome concentration-depth profiles in 3D tumor cell spheroids, and (f) evaluated model performance by statistical comparison of the simulated data with the experimental data.Additional simulations depicted the effects of liposome properties of liposome concentrations/amounts in subcompartments within spheroids, as functions of time and spatial positions (i.e., spatiokinetics).

Calculation of diffusive transport of cationic liposomes in 3D spheroids

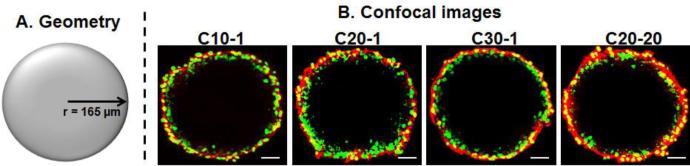

Figure 1A shows the geometry of a spheroid (330 μm diameter, average size of spheroids used in experiments). The three moieties in a spheroid are liposomesin the interstitium, liposomesbound to cell surface and liposomesinternalized into cells; the corresponding concentration terms are Cinterstitial,spheroid, Cbound,spheroid,and Cin,spheroid. Eq. 1 describes changes of Cinterstitial,spheroid as functions of time t and radial positionr (from spheroid center, as used in polar coordinate systems). Eq. 2 describes changes ofCbound,spheroid with time as a function of Cinterstitial,spheroid, assuming saturable liposome binding to cells. Eq. 3 describes changes ofCin,spheroid with time as a function of Cbound,spheroid, assuming liposome internalization follows binding to cell surface.Di is interstitial diffusivity. Bmax, spheroid is maximum binding sites in a spheroid. kinis rate constant for liposome internalization. kon and koff are rate constants of liposome association with cells and dissociation from cells. Because liposome penetration is from the outer perimeter to the center of a spheroid, the penetration distance is defined as spheroid radius (R) minus r or (R-r).

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

Figure 1. Geometry (A) and confocal images of spheroids treated with cationic liposomes (B).

12 hr incubation with 0.1 nM NP (C10-1, C20-1, and C30-1), or 0.55 nM liposomes (C20-20). Green: Nuclei. Red: Liposome NP. Yellow: Overlapping nuclei and liposomes. The results of C20-20 were obtained in our earlier study [1]. Bar, 50 μm. Color pictures are in the web version of the publication.

Eq. 4 describes Ctotal,spheroid as the sum of Cbound,spheroid,Cin,spheroid and Cinterstitial,spheroid. The Cbound,spheroid(calculated as amount of cell-bound liposomes divided by spheroid volume) and Cin,spheroid(amount of internalized liposomes divided by spheroid volume) represented the volume-adjusted values; this is because their calculation used Bmax,spheroid, which reflects the total maximum binding provided by all cells in a spheroid. In comparison, Cinterstitial,spheroidis the concentration per unit volume of interstitial fluid and therefore was adjusted by thevolume fraction of interstitial space.

| (4) |

For the initial conditions when t equals 0, Cinterstitial,spheroid, Cbound,spheroid and Cin,spheroid equaled 0. For the boundary conditions, Cinterstitial,spheroidequaled the concentration in culture medium Cmedium,spheroidat spheroid perimeter (r=R) and equaled zero at spheroid center (r=0).

Experimental determination of liposome-cell biointerface parameter values

kin, kon, koff, and Bmax were experimentally determined using cells in monolayer cultures, as previously described[1].Briefly, cells were incubated with rhodamine-labeled liposomes at 4°C and 37°C. Afterward, culture medium and cells were collected. Cells were washed with ice-cold serum-free phosphate-buffered saline, trypsinized and solubilized with Triton-X100. The fluorescence signals were measured using a fluorescence spectrometer (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) at excitation/emissionwavelengths of 543/594 nm. Signals were corrected for the values in control groups (i.e., without liposomes), which were typically between 1-10% of liposome-treated groups. Liposome concentrations were calculated from fluorescence intensity using standard curves constructed with known concentrations of liposomes. All standard curves were linear at the stated concentration ranges. The liposomes in culture medium represented extracellular concentration (equaled Cmedium,monolayer). The liposomes associated with cells after incubation at 4°C represented surface-bound NP (Cbound,monolayer). The liposomes associated with cells after incubation at 37°C represented the sum of Cbound,monolayer and Cin,monolayer. Initial estimates of parameters were obtained as follows. Bmax,monolayer,total cellsfor all cells in monolayer cultures was calculated from the Cbound,monolayervs.Cmedium,monolayer plot. Assuming Cin,monolayer was 0 at time zero and Cbound,monolayer was constant over time, the slope of Cbound,monolayervs.Cin,monolayerplot yielded kin. Initial values of kon and koffwere estimated from Cbound,monolayervs. time plot. The initial estimates were then used to obtain the final parameter values by simultaneously fitting Eq. 5-7 to the experimentally determined Ctotal,monolayervs. time profiles using nonlinear regression. Dividing the Bmax,monolayer,total cellsvalue with the cell number in monolayer cultures yielded the Bmax for a single cell (Bmax,single cell), which was used to calculate Bmax,spheroid, the molar concentration of cell surface binding sites in a spheroid with a cell density ϕ. ϕ for individual spheroids was calculated as (volume of total cells in each spheroid) divided by (spheroid volume).

The study of concentration-dependent liposome uptake in cells used 8 concentrations (range,

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

0.05-3 nM) and a single time point (6 hr), whereas the time-dependent liposome uptake in cells used a single liposome concentration of 0.1 nMand 6 time points (range, 0-6 hr). Some results of liposomes containing 20 mol% DOPE obtained in our earlier study [1] were included for comparison.

Calculation of effective liposome diffusivity in spheroids

The effective diffusion coefficient in spheroid interstitium Diwas calculated in three steps as previously described [1]. First, the diffusion coefficient of liposomes in water at 37°C, D0, was calculated based on the liposome size (radius) using the Stokes-Einstein equation. Next, the diffusion coefficient in the interstitium Dint was calculated as for diffusion in a porous gel matrix (i.e., adjusting D0 to account for the presence of matrix proteins and fibers, assuming collagen as the major component). The third step was to convert Dint to Di , by correcting for the porosity in spheroids (Eq. 8). rp is radius of liposome and rf is radius of collagen fiber (equals 20 nm).ϕcell is volume fraction of tumor cells.ϕint is volume fraction of interstitial space

| (8) |

Computation methods

Eq. 1-3 were solved numerically with the finite element method, using Multiphysics COMSOL 3.5 (Comsol, Los Angeles, CA). For COMSOL simulations, we used the sphere geometry with a 330 μm diameter (equaled the average size of spheroids used in the experiments), and used the Cmedium,spheroid to generate the Ctotal,spheroid-depth profiles in 3D spheroids as functions of treatment times and Cmedium,spheroid. Eq. 5-7 were fitted to experimental data using WinNonlin 6.0 (Pharsight).

Chemicals and reagents

Phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4) and cell culture supplies (phenol red-free RPMI 1640 with L-glutamine, trypsin-EDTA, fetal bovine serum or FBS, antibiotic-antimycotic) were obtained from Invitrogen-GIBCO (Carlsbad, CA). Agarose and other chemicals were purchased from Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, MO), 10% buffered formalin phosphate from Fisher Scientific (Fair Lawn, NJ), Triton X-100 from RICCA Chemical (Arlington, TX), and 4’-6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, dihydrochloride (DAPI) from Invitrogen (Eugene, OR). Lipids (DOTAP, DOPE, 1,2-dipalmitoyl-snglycero-3- phosphocholine (DPPC), DOPE-N-(lissaminerhodamine B sulfonyl) ammonium salt (Rhod-DOPE), 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3- phosphoethanolamine-N-[methoxy(polyethylene glycol)-2000] (PEG-DSPE), cholesterol) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). All other reagents and solvents, analytical or chromatographic grade, were purchased from Fisher Chemicals (Pittsburgh, PA). All materials were used as received.

Liposomes: Preparation and characterization

A total of eight cationic liposomes were used to study the effects of positive surface charge (DOTAP concentration of 10-30 mol%) and fusogenic lipids (DOPE concentration of 0-20 mol%). The other lipids were PEG-DSPE, cholesterol, and DPPC (see Results). Allliposomes, except C20-0, were labeled with 1 mol% Rhod-DOPE to enable quantification. Liposomes were prepared using the standard thin-film hydration method and extrusion through a polycarbonate membrane (100 nm pore size), and the number of lipid molecules per liposome was calculated using lipid bilayer thickness and average head area for individual lipids,as we previously described [1].The average size, polydispersity index (PDI), and surface charge were measured using ZetasizerNano ZS90 (Malvern, Westborough, MA).

Cell and spheroid cultures

Human pharynx FaDu cells (ATCC, Manassas,VA)were maintained in RPMI1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic. Spheroids were prepared using the liquid over-lay technique [1]. Briefly, cells (200 μl of 1×104 cells/ml 10% FBS-containing medium) were added to a well in 96-well plates coated with solidified agarose solution (1% in PBS, pH 7.4); spheroids were established after 4 days.

Cationic liposome size change: Qualitative and quantitative measurements

We used two methods to measure changes in the size and PDI of cationic liposomes upon incubation with monolayer cells,spheroids, and conditioned medium (collected after incubating 1×106 cells in 3 ml serum-free culture medium for 6 hr at 37°C). The first method used the particle size analyzer to quantify the average size and PDI. The second, qualitative method was time-lapse confocal scanning microscopy. Briefly, cells (1×105) were seeded onto a slide and allowed to attach overnight at 37°C. The slide was placed in an environmental chamber (37°C, 5% CO2, 95% humidity) on a Leica inverted microscope connected to a laser-scanning head (Leica TCS SP8 Microsystems, Germany) with an immersion corrective objective(numerical aperture, 0.75). Excitation of rhodamine was accomplished at 552 nm (3% power) and live-cell images were taken at two focus planes (slide surface and 50 μm above the surface; 2048×2048 resolution). One-minute videos were taken (512×512, 1000 Hz) every 5 min over 24 hr. Data was processed using the Leica LAS AF software.

Liposome transport in spheroids and quantitative image analysis

Spheroid structure was monitored by the movement of the nucleus dye DAPI as previously described [1]; treatment with cationic liposomes for up to 12 hrhad no effect on spheroid structure (not shown).After incubation with liposomes for 2, 6 and 12 hr, spheroids were collected, washed, fixedin 10% formalin for 20 min, and analyzed with confocal microscopy and quantitative imaging. For each spheroid (5 spheroids per condition), a total of 20 lines were drawn from the center to the periphery using the Zeiss LSM META 510 software, with each line separated by 18° angles. For each line, changes in fluorescence intensity with distance from spheroid periphery were measured. Due to the unavoidable unevenness of the spheroid surface, the point of highest intensity was taken as the outermost boundary. We used the average values of the 20 lines to minimize the spatial variability. Only data points with fluorescence intensities that exceeded 2 standard deviations of the background fluorescence (of untreated spheroids) were included. The area under fluorescence intensity-penetration depth curve (AUC) was calculated using the linear trapezoidal rule. Half-width W1/2 was the distance in a spheroidover which the Ctotal,spheroid declined by 50% from its maximal value (Cmax,spheroid), and was determined using log-linear regression over a 8- to 10-fold concentration decline. A higher AUC value indicates an increase in the amount of liposomes whereas a longer W1/2 indicates a deeper penetration and a more shallow concentration decline.

To determine the total amountof liposomestaken up in spheroids after incubation, spheroids (50 per data point) were washed, trypsinized, solubilized using Triton X-100 and analyzed for fluorescence intensity.

Effects of time-dependent changes in Cmedium,spheroid and Di: In silicostudies

Eq. 1-3 were the original model in our previous study (Original Model). This earlier modelused a constant Cmedium,spheroidvalue because the depletion of NP due to uptake into spheroids was relatively minor (<5%). In view of the different extents of depletion for the different liposomes in the current study (ranging from 1.4% to 8.7%), we modified the Original Model to account for changes of Cmedium,spheroidwith time (Dynamic Cmedium Model). In addition, different liposomes showed different extents of size increase in the presence of tumor cells (ranging from <20% to 220%). Because size determines diffusivity, the model was modified to account for the time-dependent changes of Di (Dynamic Di Model).For Dynamic Cmedium Model, wemeasured the Cmedium,spheroidvalues at 2, 6, and 12 hr, and input these values into COMSOL to create a polynomial (piecewise cubic) curve to generate Cmedium,spheroidas a function of time; these Cmedium,spheroidvalues were used with Eq. 1-3 to simulate the liposome concentration-depth profiles in spheroids. The Dynamic Di Model was similarly derived using the Divalues calculated from liposomes sizes at 2, 6, and 12 hr. Profiles simulated using Dynamic and Original Models were compared to experimental results, to determine whether inclusion of the dynamic processes improved the model performance.

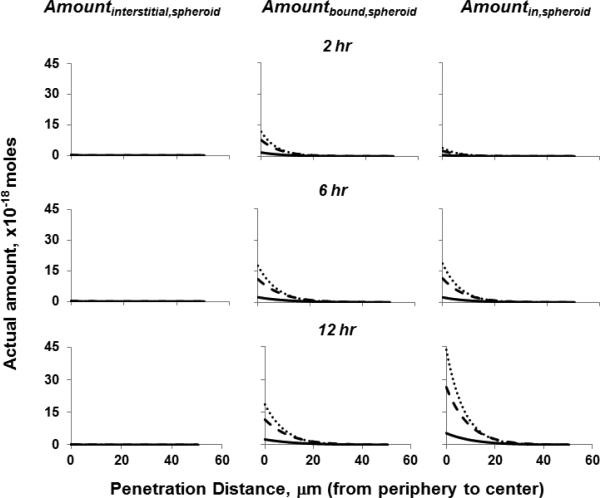

Application of diffusive transport model: Effects of liposome properties on distribution in subcompartments within spheroids

The experimental results indicated 2-fold differences in the liposome amounts in 50 spheroids (see Results). In order to determine if these differences were due to differences in liposome binding or internalization in cells, we used Eq. 1-3 to simulate the relative concentrations of liposomes in spheroid interstitium, bound to cell surface and internalized in cells, as functions of time and spatial positions. The concentration profiles were then converted to amount profiles in the corresponding subcompartments, and further normalized to the experimentally determined total liposome amounts for individual liposomes.

Statistical analysis

For analysis of differences in liposome parameters (size, PDI, uptake amount) and the effect of time, we used analysis of covariance with time as the covariate. Differences between individual formulations were assessed by post hoc Student's t-test at α of 0.05, with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.

RESULTS

Liposome properties

We studied eight cationic liposomes that contained 5 mol% PEG-DSPE, 50 mol% cholesterol, varying DOTAP content (10-30 mol%) and varying DOPE content (0-20 mol%); the remaining lipid was DPPC and ranged from 5 to 34 mol%. These liposomes had an initial average size of about 135 nm, about 2-fold range in PDI (0.3-0.5), and about 1.7-fold range in zeta potential (25 to 44 mV). Liposomes were denoted by their DOTAP and DOPE contents, i.e., C10-1 indicates 10 mol% DOTAP plus 1 mol% DOPE whereas C20-20 indicates 20 mol% DOTAP plus 20 mol% DOPE. For liposomes comprising 1 mol% Rhod-DOPE, increasing the DOTAP content from 10 to 20 and 30% increased the surface charge by about 80%, from 25 to 36 and 44 mV, respectively.

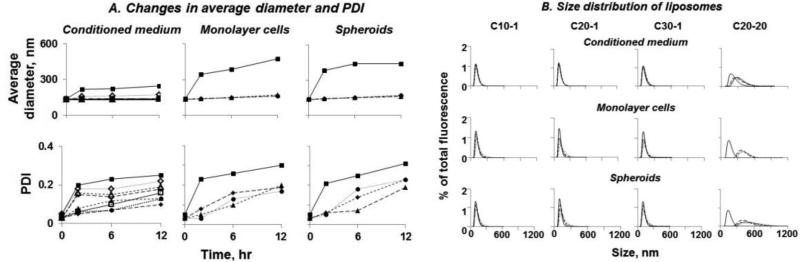

Figure 2A shows that increasing the DOTAP content had no or minimal effects on the average size and PDIover time (i.e., no change in serum-free medium or conditioned medium, <30% increase after incubation with cells for 12 hr). This was not the case for DOPE. First, liposomes with lower DOPE content (1 to 10 mol%, defined as low-DOPE liposomes) had no size change with or without cells, whereasthe liposomes with higher DOPE contents of 15 and 20 mol%(defined as high-DOPE liposomes) showed substantial size increase in conditioned medium and/or in presence of cells(p<0.0001); the increases in size progressed with time (p<0.0001). Second, the size distribution, indicated by PDI values,widened for all formulations in cells and conditioned medium relative to serum-free medium (p<0.05) with greater widening for formulations containing 5 mol% DOPE and greater (p<0.01). The increases in PDI also progressed with time (p<0.0001).

Figure 2. Liposome size change over time.

Changes in liposome size distribution upon incubation with conditioned medium, monolayer cells or spheroids were monitored. A. Changes in average diameter and polydispersity index (PDI). C10-1 ( ). C20-1 (

). C20-1 ( ). C30-1 (

). C30-1 ( ). C20-0 (

). C20-0 ( ). C20-5 (

). C20-5 ( ). C20-10 (

). C20-10 ( ). C20-15 (

). C20-15 ( ). C20-20 (

). C20-20 ( ). B. Comparison of three low-DOPE liposomes (C10-1, C20-1, C30-1) and one high-DOPE liposomes (C20-20). Solid line: 0 hr. Dotted lines from left to right: 2, 6, and 12 hr. The results of C20-20, obtained in our earlier study[1], are included for comparison. Note the C20-20 liposomes in the current study is the same as the C20-5 liposomes in the earlier study.

). B. Comparison of three low-DOPE liposomes (C10-1, C20-1, C30-1) and one high-DOPE liposomes (C20-20). Solid line: 0 hr. Dotted lines from left to right: 2, 6, and 12 hr. The results of C20-20, obtained in our earlier study[1], are included for comparison. Note the C20-20 liposomes in the current study is the same as the C20-5 liposomes in the earlier study.

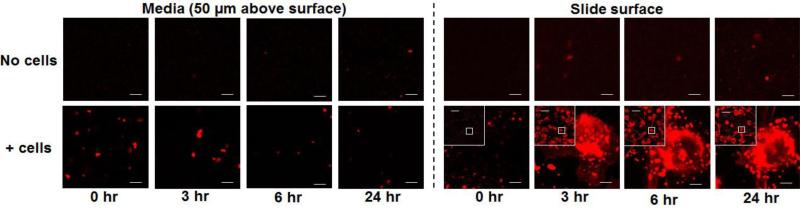

The time-dependent size increase for the high-DOPE liposomeswas confirmed by live cell confocal microscopy results. Figure 3 shows that in serum-free medium, the size of C20-20 was below the lower visible limit of ~300 nm for about 3 hr, indicating minimal size increase in the absence of cells. In contrast, the same liposomes, upon addition to cells, immediately formed visible aggregates (>300 nm diameter) that continued to enlarge to 4,000-5,000 nm at about 2 hr, after which time the larger aggregates settled on the slide surface. Additional time-lapse microscopy data, obtained every 5 min over 24 hr, show the progressive size increase and aggregation of C20-20 in the presence of cells over 24 hr (Video 1 and 2). In comparison, the low-DOPE liposomes with a similar surface charge, C20-1, did not show appreciable size change (Video 3 and 4).

Figure 3. Instability of C20-20 liposomes: Confocal microscopic results.

Live-cell images were taken at two focal planes (slide surface and 50 μm above the surface). Culture in serum-free medium. Bars in main pictures: 5 μm. Bars in insets: 50 μm. Color pictures are in the web version of the publication.

In view of the minimal size change at 1mol% Rhod-DOPE, subsequent studies compared the transport of three low-DOPE liposomescomprising 10, 20 and 30mol% DOTAP and 1mol% Rhod-DOPE (i.e., C10-1, C20-1, and C30-1) to the transport of the high-DOPE liposomes comprising 20mol% DOTAP plus 1mol% Rhod-DOPE and 19 mol% DOPE (total of 20 mol% DOPE, C20-20).

Measurement of liposome-cell biointerface parameters in monolayer cells: Effects of surface charge and DOPE content

Eq. 5-7 describe saturable liposome binding to cells. Because the binding curve of C10-1 shows the characteristics of combination of saturable and nonsaturable binding, we also evaluated a model that included nonsaturable binding. Based on the results of AkaikeInformation Criterion, which favored the saturable binding model(lower Akaike value of -201vs.-130), subsequent analysis used the saturable binding model.

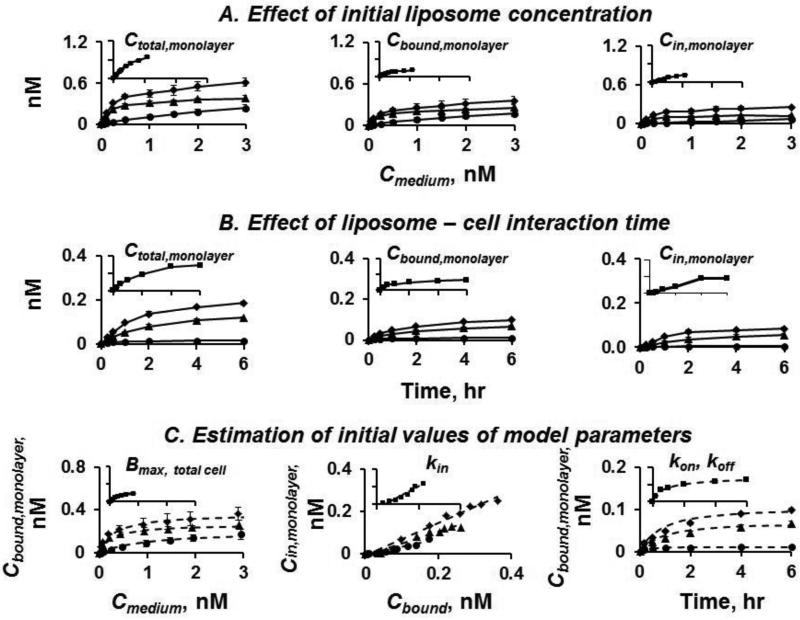

Figures 4A and 4B show the concentration- and time-dependent uptake and accumulation of three low-DOPE liposomes in monolayer cells; Cbound,monolayer, Cin,monolayer, and Ctotal,monolayer increased with Cmedium,monolayer, treatment time, DOTAP content and positive surface charge. Analysis of these results yielded the values of liposome-cell biointerface parameters (Figure 4C, Table 2). These parameter values showed a trend of positive correlation between liposome binding and uptake in cells (i.e., kon, kin, Bmax,single cell) with DOTAP content whereas the parameter of liposome dissociation (koff) showed a negative correlation. There are noteworthy differences between the low-DOPE and high-DOPEliposomes. Among the three low-DOPE liposomes, changes in the biointerface parameter values were within a relatively narrow range of ≤50%. In comparison, while C20-20 had similar Bmax, konand koffvalues, it displayed a 3-times higher kin value (e.g., compared to C20-1). As shown below, the differences in liposome-cell biointerface parameters resulted in differences in diffusive transport in 3D tumor cell spheroids.

Figure 4. Measurement of liposome-cell biointerface parameters.

C10-1 (●). C20-1 (▲).C30-1 (◆). (A) Effect of initial liposome concentration (range, 0.05-3 nM). 6 hr incubation.(B) Effect of liposome-cell interaction time. The initial concentration was 0.1 nM for liposomes with 1 mol% DOPE (C10-1, C20-1, and C30-1). 6 time points (0-6 hr).Solid lines in A and B: Experimentally observed data.(C) Determination of model parameter values; goodness-of-fit of nonlinear regression results against experimental data shown in dashed lines.Note the differences in y-axis. Data for high-DOPE C20-20 obtained in our earlier study[1] are included for comparison (insets, same units for the x and y scales as main plots; ■).

Table 2.

Effect of surface charge and DOPE content on uptake of cationic liposomes in spheroids.

| Liposome | % Cmedium,spheroid in spheroids | fmole-equivalent | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 hr | 6 hr | 12 hr | 2 hr | 6 hr | 12 hr | |

| C10-1 | 0.40±0.06 | 0.70±0.11 | 0.84±0.01 | 1.21±0.19 | 2.10±0.33 | 2.52±0.04 |

| C20-1 | 1.58±0.07 | 2.51±0.08 | 2.97±0.01 | 4.75±0.21 | 7.53±0.24 | 8.91±0.02 |

| C30-1 | 2.13±0.26 | 3.14±0.30 | 3.74±0.24 | 6.39±0.78 | 9.42±0.89 | 11.2±0.72 |

| C20-20 | 1.85±0.20 | 3.37±0.09 | 3.68±0.10 | 5.54±0.60 | 10.1±0.26 | 11.0±0.29 |

Spheroids were incubated with liposomes, at initial Cmedium,spheroid of 0.1 nM(C10-l, C20-1, C30-1) and 0.55 nM(C20-20); data were normalized to 0.1 nMCmedium/spheroid. Results are liposome amounts in 50 spheroids (average ± 0.5 range of 2 experiments).

Calculation of effective liposome diffusivity in interstitium

The volume fraction of tumor cells in spheroids was 56.0 ± 7.3% (mean±SD of 10 spheroids; range, 50.0-68.9%). The volume fraction of extracellular collagen fibers was 0.06 (equals the multiplication product of (collagen concentration of 0.032 g/cm3 in spheroid interstitiumand (effective volume of collage fibers, which equals 1.89 cm3/g) [1]. Hence, the volume fraction of interstitial space, which equals the remaining volume fraction, was 44%. Table 1 shows the calculated values of D0, Dint and Di.

Table 1. Liposome-cell biointerface and liposome transport parameters.

Mean ± SD (n=3).

| Parameters | C10-1 | C20-1 | C30-1 | C20-20* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model parameters measured in monolayers | ||||

| kon, cell-liposome association rate constant, M−1s−1×105 | 1.70 ± 0.14 | 1.78 ± 0.27 | 2.18 ± 0.41 | 2.02 ± 0.04 |

| koff, cell-liposome dissociation rate constant, s−1×10−4 | 1.77 ± 0.02 | 1.25 ± 0.38 | 0.95 ± 0.42 | 1.41 ± 0.30 |

| kin, liposome internalization rate constant, s−1×10−4 | 0.55 ± 0.06 | 0.60 ± 0.11 | 0.63 ± 0.14 | 1.69 ± 0.01 |

| Bmax,single cell, number of binding sites per cell, ×105 | 0.89 ± 0.01 | 1.08 ± 0.02 | 1.33 ± 0.09 | 1.26 ± 0.27 |

|

Model parameters calculated for spheroids | ||||

| Bmax spheroid, cell surface binding capacity for NP in spheroids, M×10−8 | 4.23 ± 0.10 | 5.15 ± 0.13 | 6.31 ± 0.41 | 5.64 ± 2.01 |

| D0, diffusion coefficient in serum-free medium, mm2s−1×10−6 | ||||

| Calculated using initial liposome size | 4.06 | 3.98 | 4.13 | 4.00 |

| Calculated using liposome size at 2 hr | 3.92 | 3.97 | 3.92 | 1.59 |

| Calculated using liposome size at 6 hr | 3.66 | 3.68 | 3.66 | 1.43 |

| Calculated using liposome size at 12 hr | 3.43 | 3.21 | 3.43 | 1.17 |

| Dint, diffusion coefficient in tumor interstitium, mm2s−1×10−6 | ||||

| Calculated using initial liposome size | 1.77 | 1. 7 | 1.82 | 1.72 |

| Calculated using liposome size at 2 hr | 1.65 | 1.7 | 1.65 | 0.19 |

| Calculated using liposome size at 6 hr | 1.45 | 1.47 | 1.45 | 0.13 |

| Calculated using liposome size at 12 hr | 1.28 | 1.12 | 1.28 | 0.06 |

| Di, diffusion coefficient in spheroids, mm2s−1×10−6 | ||||

| Calculated using initial liposome size | 0.34 | 0.33 | 0.35 | 0.33 |

| Calculated using liposome size at 2 hr | 0.32 | 0.33 | 0.32 | 0.04 |

| Calculated using liposome size at 6 hr | 0.28 | 0.28 | 0.28 | 0.03 |

| Calculated using liposome size at 12 hr | 0.25 | 0.22 | 0.25 | 0.01 |

|

Boundary conditions for simulations | ||||

| Cmedium,spheroid (experimentally determined) | ||||

| Initial (0 hr), % | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| At 2 hr, % | 99.4 | 97.7 | 96.5 | 97.4 |

| At 6 hr, % | 98.9 | 96.0 | 93.5 | 96.3 |

| At 12 hr, % | 98.6 | 94.6 | 91.3 | 95.8 |

Some results on C20-20, obtained in our earlier study [1], are included for comparison.

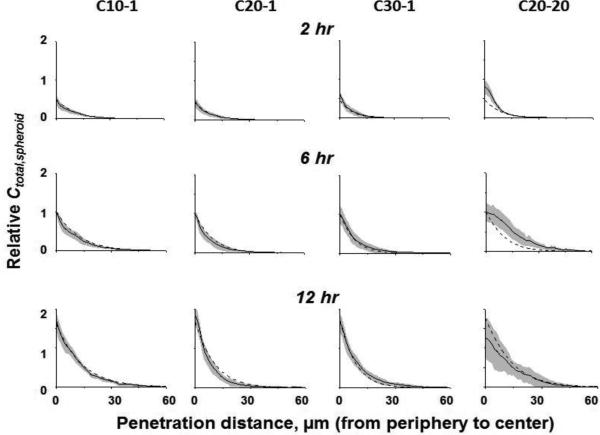

Simulation of diffusive transport of cationic liposomes

Simulations using the Original Model and the biointerface model parameters in Table 1 yielded the Ctotal,spheroid-depth profiles in Figure 5. All profiles were expressed as values relative to the 6-hr results of individual liposomes. All liposomes showed two common features. First, the Ctotal,spheroid were at the highest levels at the spheroid periphery, followed by rapid decline to undetectable levels at ≤40 μm. Second, Ctotal,spheroid increased with time, by about 4-fold from 2 hr to 12 hr. These findings indicate the diffusion of liposomes in spheroids was a slow process (occurring over hours) and was limited to the first few cell layers. Comparison of the profiles for the three low-DOPE liposomes to the profile of the high-DOPE liposome show a trend of less steep decline for the latter.

Figure 5. Diffusive liposome transport in 3D spheroids: Simulated results (dashed lines) vs. experimentally observed results (mean values: solid lines; 95% CI: shaded areas).

Relative Ctotal (sum of Cinterstitial,spheroid, Cbound,spheroid and Cin,spheroid) normalized to the values at 6 hr. The C20-20 data obtained from our previous study [1] are included for comparison.

Experimental determination of liposome diffusion in 3D tumor cell spheroids: Effects of surface charge and DOPE content

We used spheroids with average diameter of 330 ± 8.6 μm (mean ±SD; n=45). For low- and high-DOPE liposomes, the Cmedium,spheroid dropped by 1.4% to 8.7% after 12 hr incubation with spheroids(Table 1); the rank order of depletion is consistent with the % of liposome dose recovered in spheroids (Table 2). The sum of post-incubation Cmedium,spheroid and amount in spheroids accounted for >95% of the liposome dose.

Figures 1B-1E show the confocal images of spheroids after 12 hr incubation with three low-DOPE liposomes (C10-1, C20-1, C30-1) and a high-DOPE liposome (C20-20). Figure 5 shows the image analysis results of Ctotal,spheroid-depth profiles (with 95% CI). Table 3 shows the AUC, Cmax,spheroid, and W1/2 values. These results indicate both surface charge and DOPE content affected the cationic liposome diffusion in 3D spheroids. Among the three low-DOPE liposomes, increasing the surface charge significantly enhanced the liposome uptake in spheroids, such that the amount of C30-1 was 4-5-times higher compared to C10-1 (p<0.0001). This finding is consistent with the surface charge-dependent changes in kin, kon, koffand Bmaxvalues. In contrast, the 12-hr uptake of the high-DOPE liposome was higher than that of the low-DOPE liposome with similar surface charge (C20-1) and was about equal to that of C30-1 with a higher charge.

Table 3.

Effects of changes in liposome size, Cmedium, and Di: Comparison of simulated data with experimental data.

| C10-1 | C20-1 | C30-1 | C20-20* | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orig | Cmed | Di | Cmed+Di | Orig | Cmed | Di | Cmed+Di | Orig | Cmed | Di | Cmed+Di | Orig | Cmed | Di | Cmed+Di | |

|

% Agreement, average & range

|

||||||||||||||||

| 95% CI | 97 | 97 | 100 | 100 | 85 | 85 | 95 | 94 | 85 | 82 | 68 | 67 | 48 | 48 | 20 | 20 |

| 92-100 | 92-100 | 55-100 | 55-100 | 86-100 | 82-100 | 81-88 | 72-88 | 34-85 | 31-85 | 17-98 | 17-98 | 0-54 | 0-54 | |||

| 97.5% CI | 99 | 99 | 100 | 100 | 94 | 95 | 100 | 100 | 97 | 97 | 97 | 97 | 61 | 61 | 28 | 28 |

| 96-100 | 96-100 | 82-100 | 86-100 | 92-100 | 92-100 | 92-100 | 92-100 | 38-100 | 38-100 | 0-70 | 0-70 | |||||

|

% Deviation |

||||||||||||||||

| Relative Cmax,spheroid | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 10 | 9 | 20 | 9 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 32 |

| W1/2, μm | 19 | 19 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 17 | 18 | 24 | 24 | 31 | 31 | 68 | 68 |

| Relative AUC | 10 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 13 | 13 | 9 | 9 | 17 | 18 | 22 | 23 | 30 | 33 | 70 | 70 |

Data, experimental results. CI: confidence intervals of experimental results. Simulated results of Ctotal,spheroid-depth profiles using the original model (Orig), dynamic Cmedium(Cmed), dynamic Di(Di), and combined dynamic Cmed+Di models. The average number of simulated data points for each profile was 20. % Deviation, difference between simulated and experimental results (absolute values). Cmax,spheroid and AUC are expressed as relative values normalized to the values at 6 hr. Results represent averages of data at 3 time points (2, 6 and 12 hr). For C10-1, C20-1, C30-1, and C20-20, the respective average 95% and 97.5% CI values were 0.18 (range, 0.14-0.21) and 0.24 (range, 0.19-0.27), 0.19 (range, 0.13-0.27) and 0.26 (0.17-0.36), 0.19 (range 0.14-0.22) and 0.35 (range, 0.16-0.44), and 0.23 (range, 0.06-0.38) and 0.30 (range, 0.08-0.50); the respective average relative Cmax,spheroid values were 1.1, 1.1, 1.1, and 1.0; the respective W1/2(μm) were 7, 7, 6 and 9; the relative AUC were 1.2, 1.1, 1.1 and 0.8.

The C20-20 data and the analysis using the Original Model were obtained from our earlier study [1].

In general, increasing the liposome-cell interaction time resulted in higher AUC, Cmax,spheroid and W1/2 for all liposomes, but there are quantitative differences among the low-DOPE and high-DOPE liposomes. For example, the low-DOPE liposomes showed increasing AUC with time and relatively constant W1/2 , whereas the high-DOPE liposome showed maximal AUC at 6 hr and doubling W1/2 between 2 and 6 hr.

Comparison of simulated results with experimental results

Figure 5 also compares the Original Model-simulated Ctotal,spheroid-depth profiles with the experimentally observed profiles. For the three low-DOPE liposomes, the simulated results closely aligned with the experimental results, with 85-97% and 94-99% of individual data points (20 data points per curve) falling within the 95% (equivalent to 1.24 standard deviations) and 97.5% CI (1.47 standard deviations), respectively (Table 3). In contrast, the high-DOPE liposome showed inferior performance, with 48 and 61% of individual data points within the 95% and 97.5% CI, respectively. Similarly, the three low-DOPE liposomes showed better agreement between model-simulated AUC, Cmax,spheroid and W1/2 values with the experimentally determined values.

Model modifications to account for time-dependent changes in Cmedium,spheroid and Di: In silicostudies

We observed changes in medium concentration and size of liposomes upon incubation with spheroids. Increases in liposome size resulted in reductions in Di (Table 1). The Di reductions for the low-DOPE liposomes were relatively small in the absence or presence of cells, at about 30%. In comparison, the Di reductions for the high-DOPE liposome were significantly greater, ranging from about 300% in serum-free medium to about 3,000% in the presence of cells. The Dynamic Cmedium and Di Models, which accounted for changes in Cmedium,spheroidand Di , yielded improved predictions in some cases (e.g., C10-1 and C20-1) and worsened predictions in other cases (C30-1 and C20-20) (Table 3). Because the large liposomes would be less likely to penetrate the spheroids, we evaluated an additional model that limited the Cmedium,spheroid to only the small NP of <140 nm diameter. This additional modification, however, also did not significantly improve the predictions (not shown). That the inferior prediction was not due to depletion of the smaller liposomes was further supported by the finding that the model overestimated the Ctotal,spheroid at the time when the corrected Cmedium,spheroid would have been at its lowest value (i.e., at 12 hr).

Application of diffusive transport model to evaluate effects of liposome properties on liposome spatiokineticsin subcompartments within spheroids

We applied the Original Model to simulate the amounts of C10-1, C20-1 and C30-1 liposomes in interstitial space, bound to cells and internalized in cells, as function of time and spatial positions within a spheroid (Figure 6). The results show, for all liposomes, the sum of Amountbound,spheroid and Amountin,spheroidaccounted for >98% of the total amount in spheroids whereas the Amountinterstitial,spheroid was negligible. Increasing the DOTAP content and surface chargesignificantly enhanced the Amountbound,spheroid and Amountin,spheroid, in the rank order of the surface charge, i.e., C30-1>C20-1>C10-1. For all three liposomes, the Amountbound,spheroid increased about 70% from 2 to 6 hr, and then remained relatively constant from 6 to 12 hr (<16% change), suggesting saturation of cellular binding sites at or before 6 hr. In contrast, the Amountin,spheroid continued to increase with time, by about 400% from 2 to 6 hr and another 150% from 6 to 12 hr. Comparison of the spatiokinetics of Amountbound,spheroid and Amountin,spheroid for C10-1, C20-1, and C30-1 liposomesfurther indicates the differences among these three low-DOPE liposomesin the first 6 hrwere primarily due to their different binding to cells, whereas the differences in the next 6 hr were primarily due to their different internalization in cells.

Figure 6. Application of diffusive transport model to depict effects of liposome properties on liposome spatiokinetics in various subcompartments within spheroids.

C10-1 (solid lines), C20-1 (dashed lines), C30-1 (dotted lines). The Amountinterstitial,spheroid for all three liposomes at all time points were below 0.3×10−18 moles (all lines located near the x-axis).

DISCUSSION

Clinical utility of NP depends on successful delivery to the target site.Studies in the last two decades have identified multiple barriers to NP delivery and transport in solid tumors [4, 7-9]. In addition, some NP properties produce opposite outcomes. For example, NP are frequently surface-modified with targeting ligands to enhance selectivity, but ligand binding to cellsretards NP transport. Similarly, pegylation increases circulation times but also decreases the endocytosis of NP [10]. Another complication is tumor properties. Solid tumors are highly heterogeneous with respect to size, vascularization, blood flow, growth rate, capillary permeability, extracellular proteins, and tumor cell density. Many of these properties are dynamic, dependent on the host (e.g., larger tumors in humans than in mice), and can change with time (e.g., tumor growth) or with treatments (e.g., apoptosis and increased porosity due to chemotherapy [7, 11]. Furthermore, changes in one property can affect other properties.For example, increase in tumor size may retard vascularization and NP delivery whereas treatment-induced changes in vasculature and vessel pore size may favor extravasation of larger NP. A new trend in cancer combination therapy is adding anti-angiogenic therapy to other standards-of-care, e.g., combinations of carboplatin/paclitaxel with bevacizumab. The dual and time-dependent effects of anti-angiogenic therapy, with initial destruction of less mature vessels and stabilization of other vessels (resulting in temporary increases in tumor blood flow) followed by reduction in blood flow, are likely to affect drug/NP delivery and retention in tumors.

Predictive models of NP transport in solid tumors offer a means to optimize NP design. The present study and our earlier study [1]are focused on diffusion, one of the two major transport mechanisms. These studies tested the hypothesis that the diffusive NP transport can be predicted using (a) NP-cell biointerface parameters (binding, association, dissociation, internalization) measured in monolayer cultures, plus (b) NP diffusivity in tumor interstitium calculated based on NP size and on spheroid structure and composition (i.e., cell density, void fraction, concentration and diameter of extracellular matrix proteins). The collective results indicate that this approachis generally applicable to NP with different sizes (20-135 nm) and surface charges (negative, near neutral, positive, -49 to +44 mV) in 3D tumor spheroids. The potential utility of the model is demonstrated by the simulation results in Figure 6, which indicate the properties of liposomes determine their spatiokinetics in various intra-spheroid subcompartments. Such information may help optimize the NP design to achieve the desired delivery and retention at the intended target sites (e.g., tumor interstitium for therapeutics that act on extracellular targets, cell membrane for antibodies, or cytosol for RNAi).

The diffusive transport model described in Eq. 1-3 was not successful in predicting the transport of cationic liposomes comprising >10 mol% fusogenic lipid DOPE. This inferior performance, in view of the in silico results showing no improvements from using the Dynamic Cmedium and Di Models, was not caused by liposomeaggregation or depletion (due to sedimentation). These high-DOPE liposomesexhibited several interesting behaviors in the presence of cells. The increase in size over time is likely due to the fusogenic property of DOPE[12, 13], attributed to its conical shape and ability to adopt an inverted lipid phase[6], and a shift of lipids towards a fusion-favorable equilibrium[14]. Second, compared to low-DOPE liposomes, the high-DOPE liposome showed similar extent and rate of cell binding, but a 3-times more extensive internalization rate. This indicates DOPE did not alter the liposome binding to cells but altered the liposome internalization into cells, possibly due to fusion with cells or additional endocytosis mechanisms.Third, Eq. 1-3 state that increasing NP binding to cells or increasing NP internalization in cells reduces the free Cinterstitial,spheroidavailable for diffusive transport in interstitium. While this was the case for the three low-DOPE liposomes (showing a trend of lower W1/2 with increasing surface charge) and other cationic liposomes in an earlier study [15], the high-DOPE liposome C20-20 did not follow this relationship. Instead, C20-20 showed deeper penetration and longer W1/2compared to C10-1 that had a lower surface charge.Fourth, for the low-DOPE liposomes, the plots of Cin,monolayervs.Cbound,monolayer yielded straight lines, indicating constant kinover time (Figure 4C). In contrast, the C20-20 liposome yielded a curve that showed two distinct phases, a slow phase at Cbound,monolayer below 0.2nMfollowed by a more rapid incline at higher Cbound,monolayervalues. The reasons for the changing kin are not apparent, but could be due to membrane changes secondary to lipid mixing, e.g., increased fusion at a critical level. Finally, the concentration-dependent effect of DOPE on promoting the diffusive transport of cationic liposomes into spheroids is consistent with an earlier study showing that adding ~30 mol% DOPE to DOTAP-containing liposomes promoted the penetration whereas adding 6 mol% PEG-DOPE had no effect [15]. Taken together, these findings indicate the presence of >10 mol% DOPE in cationic liposomesaltered the liposomeinteraction with cells or cellular components, resulting in changes in liposome structure and diffusion in tumor spheroids. We speculate there are concentration-dependent DOPE properties occurring in 3D systems thatwere not captured in the biointerface in monolayers. Fusogenic lipids, due to their ability to promote endosomal escape, are a popular choice for carriers of nucleic acid gene therapeutics [13]. Additional studies are needed to establish the in vivo fate of fusogenic liposomes.

It is noted that although the liposomes used in the present study comprised fluorescent lipids (i.e., lissaminerhodamine) that are known to promote fusion with cell membrane, the level of Rhod-DOPE was below the minimal level of 2.5 mol% required for such activities [16].

The present study used in vitro experimental systems devoid of blood flow and hence did not address the fluid flow-mediated convection, the second major transport mechanism. Depiction of NP disposition in a host would require extending the current model to account for the interstitial transport viafluid flow, transvascular transport (both into and out of vessels viadiffusion and convection) of NP, NP interaction with other tumor components (e.g., vessel wall, stromal tissues), and other processes that affect the NP disposition (e.g., distribution to other organs, elimination). Our long term goal is to extend the current diffusive transport model to include the above processes, in order to develop multiscale spatial-temporal kinetic model that links the blood pharmacokinetics to solid tumors, as functions of positions and time in different parts of a tumor. Such models may be used to account for the various and potentially counteracting dynamic processes that affect the delivery and disposition of NP in solid tumors, as well as account for the intratumoral heterogeneities (e.g., vascularization status, microenvironment) and the unavoidable dynamic changes in tumor structures due to tumor growth and treatment-induced cell death. We recently developed a multiscaletumor spatiokinetic model, based in part on diffusive and convective drug transport processes in tumor interstitium and tumor vessels, for intraperitoneal paclitaxel therapy[17]. Studies to establish analogous, multiscale models for intravenous NP therapy are ongoing.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research is supported in part by a research grant R01 EB015253 from the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, NIH, DHHS.

Abbreviations

- 3D

3-dimensional

- Amountbound,spheroid and Cbound,spheroid/Amountin,spheroid and Cin,spheroid/Amountinterstitial,spheroid and Cinterstitial,spheroid

amount and concentrationof liposomes bound to cell surface/internalized in cells/in interstitium,of a spheroid

- AUC

Area under curve

- Bmax,single cell/Bmax,monolayer,total cells/Bmax,spheroid

maximum liposome binding sites in a single cell/all cells in monolayer cultures/a spheroid

- Cbound,monolayer/Cin,monolayer/Cmedium,monolayer

concentration of liposome bound to cell surface/internalized in cells/culture medium, of monolayer cultures

- Cmax,spheroid/

maximum liposomeconcentration in spheroids

- Cmedium,spheroid

liposome concentration in spheroid culture medium

- CI

confidence intervals

- Di

diffusion coefficient in spheroids

- DAPI

4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride

- DOPE

1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine

- DOTAP

1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium propane

- DPPC

1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- kin/koff/kon

rate constants of liposome internalization in/dissociation from/association with cells

- NP

nanoparticles

- PDI

polydispersityindex

- PEG-DSPE

1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3- phosphoethanolamine-N-[methoxy(polyethylene glycol)-2000]

- Rhod-DOPE

DOPE-N-(lissaminerhodamine B sulfonyl) ammonium salt

- W1/2

half-width or distance in a spheroid over which the liposome concentration declines by 50%

- ϕcell/ϕint

volume fraction of cells/interstitial space in a spheroid

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gao Y, Li M, Chen B, Shen Z, Guo P, Wientjes MG, Au JL. Predictive models of diffusive nanoparticle transport in 3-dimensional tumor cell spheroids. AAPS J. 2013;15:816–831. doi: 10.1208/s12248-013-9478-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davis ME, Chen ZG, Shin DM. Nanoparticle therapeutics: an emerging treatment modality for cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:771–782. doi: 10.1038/nrd2614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang AZ, Langer R, Farokhzad OC. Nanoparticle delivery of cancer drugs. Annu Rev Med. 2012;63:185–198. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-040210-162544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang J, Lu Z, Wientjes MG, Au JL. Delivery of siRNA therapeutics: barriers and carriers. AAPS J. 2010;12:492–503. doi: 10.1208/s12248-010-9210-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lu C, Stewart DJ, Lee JJ, Ji L, Ramesh R, Jayachandran G, Nunez MI, Wistuba II, Erasmus JJ, Hicks ME, Grimm EA, Reuben JM, Baladandayuthapani V, Templeton NS, McMannis JD, Roth JA. Phase I clinical trial of systemically administered TUSC2(FUS1)-nanoparticles mediating functional gene transfer in humans. PLoS One. 2012;7:e34833. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hafez IM, Maurer N, Cullis PR. On the mechanism whereby cationic lipids promote intracellular delivery of polynucleic acids. Gene Ther. 2001;8:1188–1196. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Au JL, Jang SH, Wientjes MG. Clinical aspects of drug delivery to tumors. J Control Release. 2002;78:81–95. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(01)00488-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jang SH, Wientjes MG, Lu D, Au JL. Drug delivery and transport to solid tumors. Pharm Res. 2003;20:1337–1350. doi: 10.1023/a:1025785505977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li Y, Wang J, Wientjes MG, Au JL. Delivery of nanomedicines to extracellular and intracellular compartments of a solid tumor. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2012;64:29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li Y, Wang J, Gao Y, Zhu J, Wientjes MG, Au JL. Relationships between liposome properties, cell membrane binding, intracellular processing, and intracellular bioavailability. AAPS J. 2011;13:585–597. doi: 10.1208/s12248-011-9298-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu D, Wientjes MG, Lu Z, Au JL. Tumor priming enhances delivery and efficacy of nanomedicines. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;322:80–88. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.121632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wrobel I, Collins D. Fusion of cationic liposomes with mammalian cells occurs after endocytosis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1235:296–304. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(95)80017-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farhood H, Serbina N, Huang L. The role of dioleoyl phosphatidylethanolamine in cationic liposome mediated gene transfer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1235:289–295. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(95)80016-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lonez C, Lensink MF, Kleiren E, Vanderwinden JM, Ruysschaert JM, Vandenbranden M. Fusogenic activity of cationic lipids and lipid shape distribution. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2010;67:483–494. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0197-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kostarelos K, Emfietzoglou D, Papakostas A, Yang WH, Ballangrud A, Sgouros G. Binding and interstitial penetration of liposomes within avascular tumor spheroids. Int J Cancer. 2004;112:713–721. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kleusch C, Hersch N, Hoffmann B, Merkel R, Csiszar A. Fluorescent lipids: functional parts of fusogenic liposomes and tools for cell membrane labeling and visualization. Molecules. 2012;17:1055–1073. doi: 10.3390/molecules17011055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Au JL, Guo P, Gao Y, Lu Z, Wientjes MG, Tsai M. Multiscale Tumor Spatiokinetic Model for Intraperitoneal Therapy. AAPS J. 2014 doi: 10.1208/s12248-014-9574-y. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.