Summary

Ras-driven cancer cells upregulate basal autophagy that degrades and recycles intracellular proteins and organelles. Autophagy-mediated proteome degradation provides free amino acids to support metabolism and macromolecular synthesis, which confers a survival advantage in starvation and promotes tumorigenesis. While the degradation of isolated protein substrates by autophagy has been implicated in controlling cellular function, the extent and specificity by which autophagy remodels the cellular proteome and the underlying functional consequences were unknown. Here we compared the global proteome of autophagy-functional and -deficient Ras-driven cancer cells, finding that autophagy affects the majority of the proteome yet is highly selective. While levels of vesicle trafficking proteins important for autophagy are preserved during starvation-induced autophagy, deleterious inflammatory response pathway components are eliminated even under basal conditions, preventing cytokine-induced paracrine cell death. This reveals the global, functional impact of autophagy-mediated proteome remodeling on cell survival and identifies critical autophagy substrates that mediate this process.

Introduction

Macroautophagy (autophagy hereafter) is a stress-induced, self-cannibalization mechanism that captures damaged proteins and organelles in autophagosomes, which then fuse with lysosomes where their cargo is degraded. In normal cells, basal autophagy occurs at low levels to prevent chronic tissue damage and to maintain homeostasis (Mathew et al., 2007a; Mathew et al., 2007b). Autophagy substrates are degraded and recycled to provide carbon and nitrogen sources for metabolism and biosynthesis of macromolecules, and for production of cofactors for redox balance and energy (Mathew and White, 2011; Rabinowitz and White, 2010). The specificity of cargo delivery is poorly understood, but partly achieved by ubiquitin modification on cargo that is recognized by specific domains in the cargo receptor proteins such as p62/Sqstm1 (p62) (Vadlamudi and Shin, 1998). The captured cargo is then sequestered by autophagosomes that assemble around them, through coordinate action of the products of essential autophagy genes such as Atg5 and Atg7, deletions of which abrogate autophagy (Mizushima, 2007). While short-lived intracellular proteins are degraded primarily by the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS), autophagy remains the only known mechanism by which cells eliminate aggregated proteins and entire organelles.

Recent evidence suggests that autophagy is critical for cancer cell metabolism, survival and tumor maintenance (Guo et al., 2011; Guo et al., 2013a; Rao et al., 2014; Rosenfeldt et al., 2013; Strohecker et al., 2013). In contrast to normal cells, basal autophagy is dramatically upregulated in many cancers such as those driven by activation of Ras oncogenes, where it is critical for survival and for tumorigenesis (Guo et al., 2011; Guo et al., 2013b; Lock et al., 2011; Yang et al., 2011). Metabolic stress due to a deficient microenvironment and deregulated cell growth may contribute to this autophagy addiction (Degenhardt et al., 2006), but the mechanism for this autophagy-mediated survival and growth of Ras-driven cancers is only beginning to emerge.

Autophagy degrades the proteome, a major amino acid and energy source for metabolically stressed cancer cells, facilitating both survival and proliferation. Oncogenic mutations in Ras suppress mitochondrial production of acetyl-CoA and the utilization of fatty acids via β-oxidation, presumably elevating the demand for protein degradation by autophagy to support mitochondrial function through anaplerosis (Mathew and White, 2011; White, 2013). Consistent with this, autophagy deficiency in Ras-expressing tumors causes damaged proteins and defective mitochondria to accumulate, leading to impairment of energy metabolism and reduced tumor growth. Although the exact mechanism by which autophagy supports metabolism and stress survival is unknown, defects in autophagy cause deregulation of amino acid levels, and depletion of key substrates in mitochondrial metabolism, compromising mitochondrial respiration (Guo et al., 2011; Guo et al., 2013a; Rao et al., 2014; Rosenfeldt et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2011). Cancer cells are increasingly reliant on amino acids such as glutamine for mitochondrial function, and nucleotide and lipid synthesis, and redox homeostasis (DeBerardinis et al., 2007; Son et al., 2013). Despite this important role for autophagy in cancer metabolism and stress survival, a comprehensive understanding of autophagy substrates and the specific mechanisms by which autophagy supports cancer cell survival are currently lacking. Additionally, although autophagy is selective to certain cellular substrates in specific contexts, whether or not autophagy targets specific pathways to alter cell function is not understood (Mizushima and Komatsu, 2011).

Using isogenic cell models comparing autophagy-intact and -deficiency (Atg5+/+ and Atg5−/−) and the technique of Stable Isotope Labeling by Amino Acids in Cell Culture (SILAC) for proteomic analysis, we examined the role of autophagy in remodeling the proteome in basal and starvation conditions. We discovered that autophagy-mediated proteome remodeling affects the majority of the proteome and is selective, preserving cellular function of Ras-driven cancer cells. Our results show that autophagy selectively eliminates proteins (autophagy protein substrates) involved in pathways that are non-essential or toxic for survival under stress, while preferentially sparing those involved in pathways essential for the maintenance of functional autophagy and stress survival (autophagy-resistant proteins). Specifically, we found that proteins involved in the innate immune response, such as the retinoic-acid-inducible gene-I (RIG-I) pathway, accumulated in autophagy-deficient cells. Conversely, the soluble NSF attachment receptor (SNARE)-mediated vesicle trafficking, lysosome and endocytosis pathways essential for intracellular protein trafficking between endoplasmic reticulum (ER), Golgi apparatus, endosomes, and lysosomes, escaped autophagy-mediated elimination. These findings suggest that autophagy extensively remodels the proteome, and that defects in autophagy may prime non-immune cells for constitutive innate immune and inflammatory signaling with profound implications for cell survival, partly explaining the requirement for autophagy for sustaining aggressive cancer growth.

Results

Global impact of autophagy on the cellular proteome

To assess the impact of autophagy on the overall cellular proteome, we employed SILAC (Ong et al., 2002) to compare relative protein levels in isogenic wild-type (WT) (Atg5+/+) and autophagy-deficient (Atg5−/−), HRasG12V-transformed immortalized baby mouse kidney epithelial (iBMK) cells (Guo et al., 2011) in normal growth media and following 3 and 5 hours of starvation (Figure 1A). Ras expression levels in these iBMK cells are comparable to human cancer cell lines with activating Ras mutations and renders them tumorigenic, although Atg5 deficiency compromises tumor growth (Guo et al., 2011).

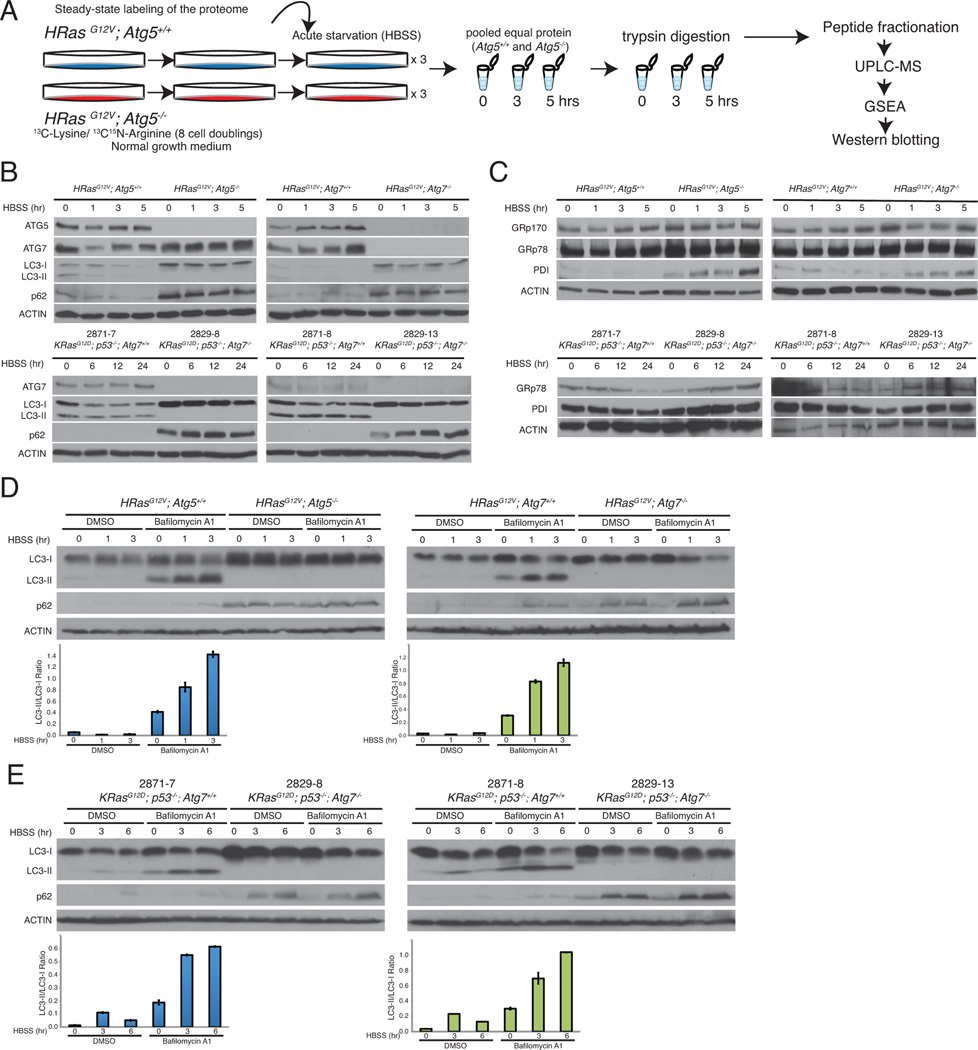

Figure 1. SILAC as a means to monitor proteome remodeling by autophagy.

A. SILAC-based proteomics comparing autophagy-deficient and competent cells. Autophagy-deficient cells were given medium containing 13C-Lysine and 13C15N Arginine for at least 8 doublings to fully label their proteome. Cells were then subjected to a starvation timecourse (0, 3, and 5 hours HBSS), trypsin digested, and analyzed by UPLC-MS.

B. Atg5 or Atg7-deficient cell lines do not have functional autophagy. Starved iBMK cells or TDCLs were lysed and immunoblotted for the indicated antibodies. β-Actin was used as a loading control.

C. Autophagy-deficient cells have ER stress in starvation. Starved iBMK cells or TDCLs were lysed and immunoblotted for the indicated antibodies. β-Actin was used as a loading control.

D-E. Starvation robustly induces autophagy in iBMK cells and TDCLs. iBMK cells or TDCLs were starved with and without lysosomal inhibitor Bafilomycin A1, lysed, and immunoblotted for the indicated antibodies. Quantitation of LC3-II/LC3-I ratio is shown as bar graphs. Quantitation is represented as mean ± SD (n=2). Data is representative of at least two independent experiments.

Western blot analysis revealed robust induction of autophagy in the WT cells in starvation as indicated by the absence of LC3-I to LC3-II processing in the autophagy-deficient cell lines, which instead accumulated the autophagy substrate p62 (Figure 1B). Autophagy defects also caused accumulation of ER chaperones GRp170 and GRp78 and protein disulphide isomerase (PDI) in both iBMK cell lines (Figure 1C; top panel), consistent with previous findings (Mathew et al., 2009). We then examined the autophagy flux with the lysosomal inhibitor Bafilomycin A1, which resulted in the accumulation of LC3-II in the WT cells, but not in the autophagy-deficient cells (Figure 1D). In tumor-derived cell lines (TDCLs) from the KRasG12D;p53−/− genetically engineered mouse model (GEMM) for non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (Guo et al., 2013a), starvation robustly induced autophagy in the WT cells, while autophagy defects resulted in p62 accumulation and elevated expression of ER stress markers (Figure 1B, 1C, and 1E). Thus the Ras-transformed Atg5 iBMK cells used for the SILAC are representative of autophagy functionality independent of tissue type and Ras subfamily.

SILAC-based mass spectrometry coupled with strong cation exchange (SCX) and off-gel fractionations (OG) and protein identification by MaxQuant (MQ) and Proteome Discoverer (PD) (Supplemental Experimental Procedures) enabled identification of 7184 proteins (~25% of the total estimated mouse proteome) present during at least one of the conditions tested (0, 3 and 5 hours of starvation) (Figure 2A; red) comparable to the most comprehensive description of the mouse kidney proteome to date (dotted circle) (Huttlin et al., 2010) (Figure 2A). Of these, 5300 proteins were identified by both MQ and PD algorithms, with 845 unique to PD and 1039 unique to MQ (Figure 2B). Similarly, 5441 proteins were identified by both fractionation techniques, with 931 unique to SCX and 812 unique to OG separations (Figure 2B), consistent with other observations of partial complementarity between the two fractionation techniques and algorithms (Barbhuiya et al., 2011; Chang et al., 2013). A substantial overlap between the proteins was identified in each starvation condition, indicating the relatively minor qualitative alterations to the proteomes (Figure 2B).

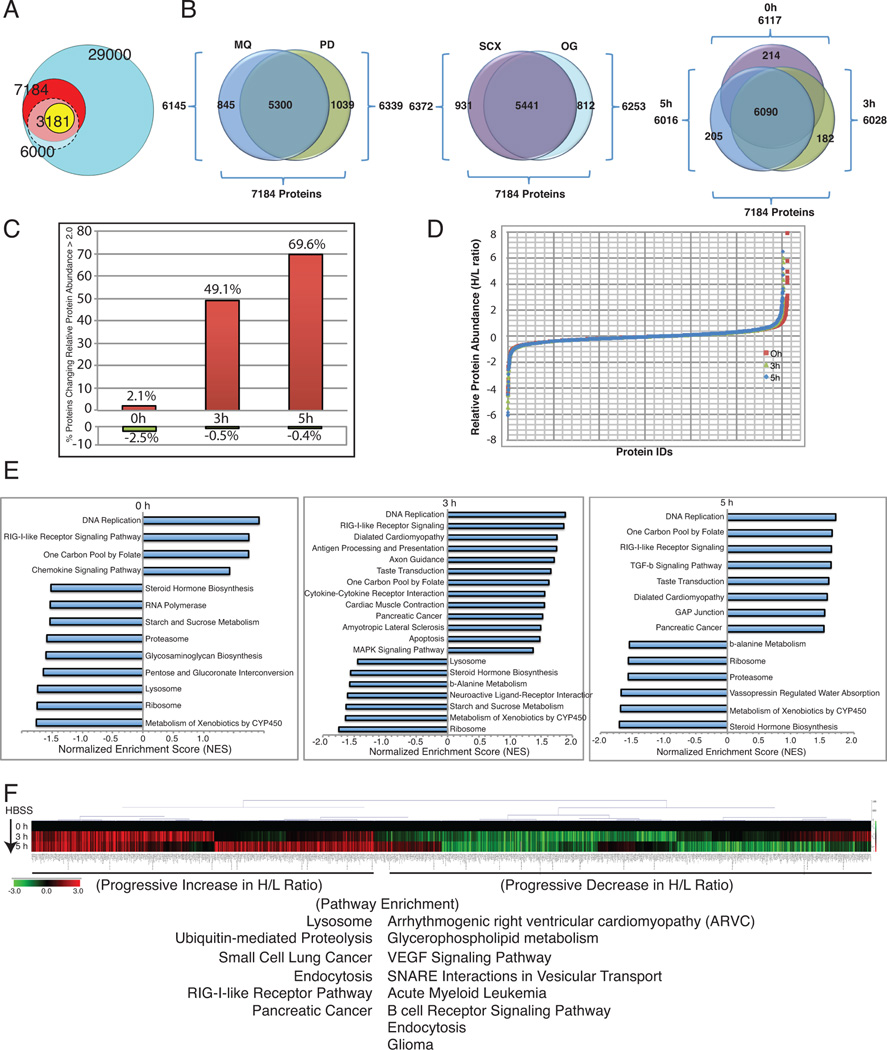

Figure 2. Effect of autophagy deficiency on the cellular proteome.

A. Venn diagrams showing statistically validated proteins by SI LAC-MS, compared to the total proteins identified in our study (red), a previously published mouse proteome (gray), and the total estimated mouse proteome (turquoise).

B. Venn diagrams showing proteins identified using MQ, and PD, and different fractionation techniques (SCX and OG), as well as the distribution of protein identifications at three different time points (0, 3 and 5 hours).

C. Bar graph showing increase in the total number of proteins that showed relative (>2 fold) increase (red) or decrease (green) in the autophagy-defective compared to the WT cells at 0, 3, and 5 hours of starvation on a per cell basis (normalized to cell number).

D. S-curve displaying relative protein abundances of all the proteins between autophagy-deficient vs. WT cells (log2 H/L ratios) shown in (A) normalized to total protein.

E. Bar graphs showing NES for pathways enriched among extremes of changes in relative protein abundances (H/L ratios) in starvation due to autophagy deficiency (only normalized p-value <0.05 are shown). Positive NES indicates enrichment for H/L ratios >1 (relative increase in autophagy-defective) and negative NES indicates enrichment for H/L ratios <1 (relative increase in autophagy-competent).

F. Hierarchical clustered heatmap with the 0h normalized log2 H/L values showing time dependent changes in relative protein levels across time points in starvation using the top and bottom 10% most pronounced changes.

We normalized the data in two ways; first we took into account difference in viability during starvation to which the autophagy-deficient cells are more sensitive, by normalizing the proteomes on a per-cell basis. The first observation was that a strikingly large percentage of the observed proteome was impacted by the functional status of autophagy, as evident by differential relative protein abundances between WT and autophagy-deficient cell lines consistent across the duration of starvation. We observed that autophagy was involved in the predicted degradation of nearly half of the overall proteome on a per cell basis within 3 hours of starvation that increased to 70% at 5 hours (Figure 2C). This suggests that autophagy is a significant mechanism for turnover and remodeling of the cellular proteome.

Second, to examine the specificity by which autophagy impacts the global proteome, proteins in each SILAC channel were normalized to total protein for each cell type and examined for relative protein abundance ratios (ratios of levels in autophagy-deficient compared to WT; Atg5−/−/Atg5+/+: Heavy/Light (H/L)) in normal growth and starvation conditions. Each condition contained groups of proteins with isproportionately higher or lower levels in autophagy-deficient cells compared to the WT, representing proteins that appear to be selectively eliminated or spared by autophagy, respectively (Figure 2D). Out of the 7184 total proteins identified, under normal conditions, 6.4% (462 proteins) were elevated (>1.5-fold) in the autophagy-deficient cells, while 6.7% (484 proteins) showed decreased levels compared to the WT cells. Following 3 hours of starvation, 5.8% (419 proteins) showed elevation and 7.2% (517 proteins) showed a decrease in relative protein levels. Similarly, after 5 hours of starvation 4.9% (352 proteins) were elevated while 7.2% (520 proteins) showed reduced relative proteins levels (Figure 2B and 2D). Thus, autophagy has a dramatic impact on the overall proteome, with its loss surprisingly producing both up and down regulation of specific proteins relative to the WT.

To examine if the changes in the proteome caused by autophagy deficiency were specific to cellular activities, we looked at the molecular functions enriched among proteins with extreme changes in their relative abundance in each condition using Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) as described previously (Subramanian et al., 2005). Interestingly, the Rig-I like Receptor (RLR) signaling pathway, DNA replication, and one carbon pool by folate metabolism were highly enriched among proteins elevated in autophagy-deficient cells at all the conditions tested (Figure 2E). Alternatively, proteins involved in cellular processes that include proteasomes and ribosomes were selectively preserved with functional autophagy as indicated by low H/L ratios.

We then examined how relative protein abundances changed across time during starvation, by subjecting the log geometric means of the relative abundance values normalized to their basal ratio (0h) to hierarchical clustering (Figure 2F). While the majority of proteins had relative protein abundances (H/L ratio) consistent across all conditions, there were clusters of proteins whose relative levels decreased (green) or increased (red) during starvation. Interestingly, pathways related to glycerophospholipid metabolism, angiogenesis (VEGF signaling), SNARE vesicle trafficking, etc. were enriched among proteins that showed progressive decrease in protein abundance in starvation (Figure 2F). In contrast, pathways related to lysosome, protein degradation (ubiquitin mediated proteolysis), etc. were enriched among proteins that showed increase (Figure 2F), consistent with the need to preserve autophagy machinery and protein homeostasis during starvation.

To examine any inherent basal difference due to the autophagy defect, and to identify a subset of proteins that showed statistically significant changes in normal and starvation conditions, we compared the overall data in Figure 2D by t-statistics calculated for each methodology, and performed hierarchical clustering of relative abundance measurements across the starvation time course. We then computed p-values based on t-statistics to determine whether the time zero intercept of proteins log2(H/L) relative abundances differed significantly over time from time zero (Figures 3A and 3B). We identified a subset of 3181 proteins that were either elevated (yellow) or depressed (blue) due to autophagy deficiency (Figure 3A), with over 50% of the proteins showing autophagy-dependent alteration.

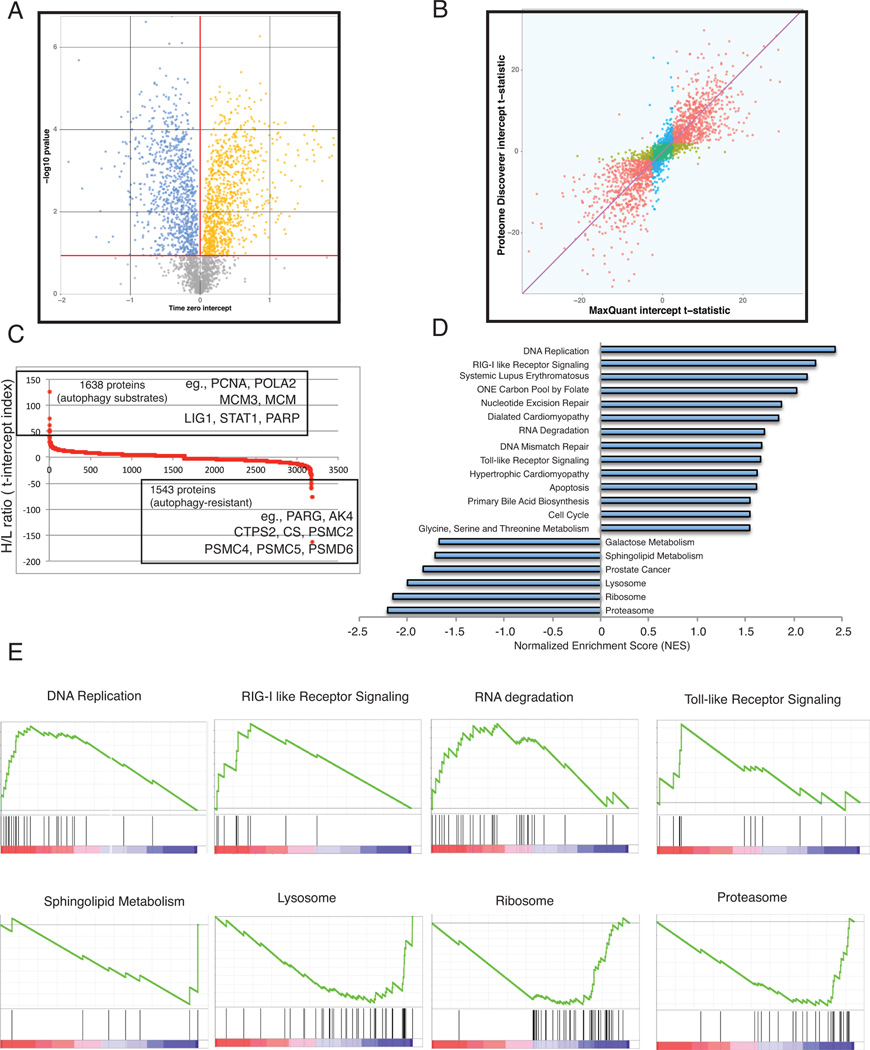

Figure 3. Pathway enrichment in autophagy-deficient cells due to defects in protein degradation.

A. Volcano plot showing statistical significance of pre-starvation differences in proteins abundance due to autophagy function. Proteins whose abundance is significantly altered due to autophagy are shown: A total of 1638 proteins (51.5%) were preferentially degraded in autophagy-competent cells (orange), while 1543 (46.7%) were selectively preserved (blue). Significance of PD based quantification is shown.

B. Scatter plot comparing statistical significance as determined by either MQ or PD. Proteins found to be elevated or depleted due to autophagy were those that exceeded an FDR of 0.05 when analyzed with both MQ and PD platforms.

C. S-plot showing relative protein abundance (H/L ratio) in 3181 proteins found to be significantly altered due to autophagy deficiency. Some select examples of proteins that showed extreme changes are highlighted.

D. NES from GSEA analysis of the 3181 proteins found to be significantly altered due to autophagy deficiency with normalized p-value <0.05 are shown.

E. Enrichment plots showing enrichment scores for significantly enriched pathways in GSEA analysis in (D).

See also Table S1.

Autophagy-mediated protein remodeling is selective

In the subset of 3181 proteins that had statistically significant changes in normal and starvation conditions that were attributable to autophagy defect, 1638 behaved as major autophagy substrates (high H/L ratio) and thus are potential markers for autophagy-mediated protein degradation (Figure 3C). Surprisingly, 1543 proteins behaved as if they were resistant to degradation (low H/L ratio), that is their levels were retained in autophagy-competent cells in starvation (Figure 3C).

Among the proteins that were enriched on both extremes, a common theme of molecular functions suggested that autophagy selectively targets protein substrates to enable cell survival. For example, DNA replication proteins including PCNA, POLA2, MCM3, MCM, and LIG1 were among the proteins elevated in autophagy-deficient cells (Figure 3C and Table S1). Importantly, levels of poly ADP ribose polymerase (PARP), a critical component of the single-stranded DNA repair, energy sensing machinery and apoptotic cell death, and STAT1, an important mediator of interferon-mediated cell death were significantly elevated in the autophagy-deficient cells (Figure 3C and Table S1) suggesting pro-survival role for autophagy through selective targeting of protein substrates.

Proteins preserved during autophagy

Consistent with a stress survival role for autophagy, specific proteins with purported roles in cellular functions essential for stress survival such as poly-(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase (PARG, poly (ADP-ribose) catabolism), adenylate kinase 4 (AK4, ATP/ADP homeostasis), CTP synthase 2 (CTPS, glutaminolysis), and citrate synthase (CS) were among ones that showed relative accumulation in the WT cells (low H/L ratio) (Figure 3C and Table S1). Similarly, several of the proteasome components (PSMC2, PSMC4, PSMC5, PSMD6, etc.) were among the proteins highly retained by autophagy in starvation (Figure 3C and Table S1). Importantly, critical components of vesicle trafficking and endocytosis such as synaptosomal-associated protein 29 (SNAP29) were also selectively preserved, indicating that maintaining functional autophagy is critical in remodeling the proteome. This suggests that autophagy selectively retains protein components of distinct pathways that are essential for cell survival.

Defects in proteome remodeling alter cellular signaling pathways

Alterations in protein homeostasis of signaling pathway components may impact the function of these pathways. Therefore, in order to test the functional consequences of this preferential proteome remodeling by autophagy on cellular stress signaling, 3181 proteins (Uniprot IDs) ranked by change in relative abundance were subjected to GSEA that allowed statistical enrichment of pathways and cellular functions on both extremes of changes. Interestingly, proteins related to DNA replication and innate immunity-related pathways such as RLR signaling, Toll-like Receptor (TLR) signaling and RNA-degradation were among the most significantly enriched in the autophagy-defective cells (Figures 3D and 3E). In contrast, pathways such as the proteasome, ribosome, and lysosome pathway were enriched in the autophagy-competent cells (Figures 3D and 3E), supporting the importance of these processes in cell survival. This consistently indicated a high degree of selectivity during starvation.

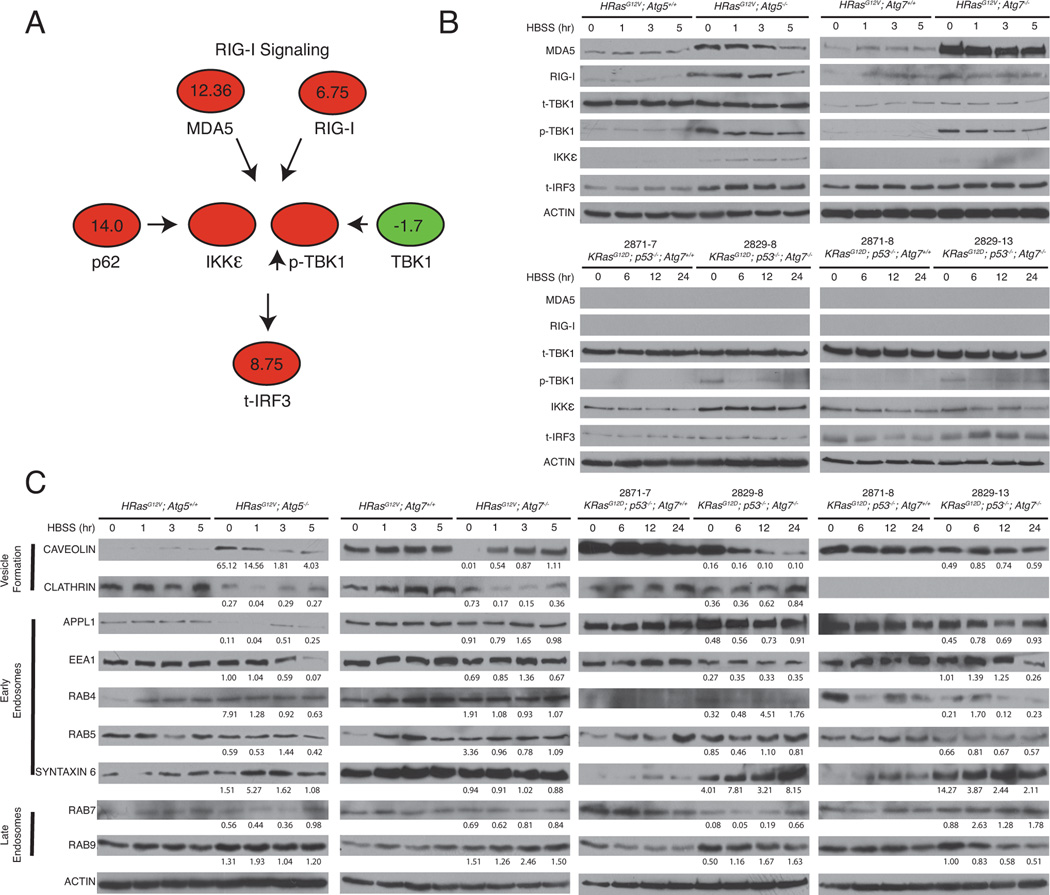

To verify the major implicated pathways by means orthogonal to SILAC-based proteomics, we explored the constituents of these pathways by Western blotting. Consistent with the SILAC data as indicated by H/L ratios for major members of the pathway (Figure 4A; red indicates high; green indicates low or unchanging), proteins in the RIG-I pathway were upregulated in the autophagy-deficient compared to the WT cells. Members of the RIG-I pathway including the double-stranded RNA virus (dsRNA) sensing RNA helicases, melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (MDA-5), and retinoid acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I), and the downstream kinases, the phosphorylated form of TANK-binding kinase 1 (p-TBK1) and the inhibitor of nuclear factor kappa-B kinase subunit epsilon (IKKε), accumulated in autophagy-deficient cells, consistent with SILAC observations (Figures 4A and 4B). Autophagy-deficient TDCLs showed similar accumulation of these proteins, although MDA-5 or RIG-I were undetectable, consistent with the requirement for p53 for the expression of these proteins (Munoz-Fontela et al., 2008). Note that the TDCLs are p53-deficient whereas the iBMKs express dominant negative p53 (p53-DD) and perhaps do not have a complete p53 block.

Figure 4. Validation of proteins designated as autophagy substrates and proteins designated as selectively preserved.

A. Pathway diagram indicating t-intercept estimates from maxQuant log2 H/L ratios for RIG-I pathway members, showing high (red) and low or unchanging ratio (green). Blank circles indicate proteins not designated by SILAC.

B. Autophagy-deficient cells accumulate RIG-I pathway proteins. iBMK cells and TDCLs were starved, lysed, and immunoblotted for the indicated antibodies. β-Actin was used as a loading control.

C. Autophagy-competent cells retain vesicle trafficking proteins in starvation. iBMK cells and TDCLs were starved, lysed, and immunoblotted for the indicated antibodies. β-Actin was used as a loading control. Quantitation of the ratio of protein between autophagy-deficient to autophagy-competent cells at the indicated timepoint normalized to p-Actin is shown as well. Quantitation is represented as mean ± SD (n=2).

Data is representative of at least two independent experiments.

In order to validate that autophagy selectively retains specific proteins essential to preserve functional autophagy and protein homeostasis, we examined proteins in different subdivisions of the endosome-lysosome pathway. Proteins involved in vesicle formation at the cell surface (caveolin and clathrin) and early endosome/vesicle fusion proteins including DCC-interacting protein 13-alpha (APPL1), early endosome antigen 1 (EEA1), RAB4, RAB5, and SYNTAXIN 6 were generally retained in the autophagy-WT cells, suggesting selective resistance to degradation (Figure 4C). Interestingly, there were differences in the mechanisms of vesicle internalization that were cell type dependent: higher levels of clathrin, but not caveolin were detected in WT iBMK cells, whereas the opposite trend was observed in the TDCLs. Thus, although mechanisms may differ depending on cell type, in general autophagy preserves functional vesicle trafficking.

Autophagy limits the interferon response by suppressing IRF3 activation

Selective accumulation of members of the RIG-I pathway in the autophagy-defective cells suggested that autophagy may be involved in suppressing innate immune and type I interferon (IFN) responses. Therefore, we examined the activation of the transcription factor interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3), which is the target of p-TBK1 and IKKε. The dimerization of IRF3 is a hallmark of its activation (Takahasi et al., 2003) and we assessed this by starving or treating cells with the synthetic dsRNA virus analog poly I:C in complexed as well as uncomplexed forms (Figure 5A). Uncomplexed poly I:C stimulates TLR3 and complexed poly I:C is detected by MDA-5. Consistent with our hypothesis, dimerized IRF3 was increased in autophagy-deficient cells, especially in response to complexed poly I:C (Figure 5A). IRF3 activation and subsequent nuclear translocation results in the transcription of genes involved in IFN response. Therefore, we investigated if the activation of the innate immune response resulted in the transcriptional activation of the IFN response by gene expression profiling of these cells under similar conditions of cellular stress (Figure 5B and Table S2). GSEA analysis identified the cytokine-cytokine receptor interactions, TLR, and JAK-STAT signaling pathways as the most significantly enriched pathways, consistent with our hypothesis (Figure 5C). Importantly, autophagy defects caused significant alterations in the expression of several IRF3 and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) target genes even under basal conditions (Figure 5D). Interestingly, JAK-STAT mediates the interferon response upon interferon alpha or beta (IFN-α or IFN-β) stimulation and autophagy defective cells showed >10 fold higher levels of STAT1 by SILAC (Table S1). This further supported our recent finding of an elevated inflammatory response with tumor-specific Atg7 deletion in KRas-driven spontaneous lung cancer (Guo et al., 2013a). Thus, autophagy functions to suppress IRF3 activation and the interferon response.

Figure 5. Autophagy suppresses IRF3 activation and subsequent transcription of IRF3-target genes.

A. Autophagy-deficient cells have increased IRF3 activation. iBMK cells were either starved or treated with Poly I:C, lysed, and probed by Native PAGE for dimerized IRF3.

B. Gene expression for HRasG12V-expressing Atg5+/+ (top) and Atg5−/− (bottom) iBMK cells in starvation. Functionally enriched genes in Atg5−/− iBMK cells (red) included those involved in the inflammatory response as shown in (C) and (D) below.

C. GSEA analysis of data in (B), showing enrichment of cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction and Toll-like Receptor signaling pathways in Atg5−/− iBMK cells under basal condition (0h).

D. Table of inflammatory genes identified in (B), by gene expression as enriched in Atg5−/− iBMK cells (0h).

E. Luciferase-reporter assays in iBMK cells showing increased IL-6 and IFN-β activity in autophagy-deficient iBMK cells. Relative fold changes of Atg5−/− as compared to Atg5+/+iBMK cells are also shown.

F. Autophagy-deficient cells have elevated secretion of inflammatory cytokines. Supernatants from iBMK cells in normal media or poly I:C treated were collected and ELISA was performed for IL-6 and IFN-β.

Data in (E–F) are represented as mean ± SD (n=2). n.s.=not significant, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, and ***p<0.001 by unpaired Student’s t-test. See also Figure S1 and Table S2.

Defects in protein homeostasis induced by autophagy deficiency deregulate protein components of the innate immunity pathway sufficient to trigger and elicit activation of IFN response. To further confirm this hypothesis, we performed interleukin-6 (IL-6) and IFN-β luciferase reporter assays. Despite similar basal levels, autophagy-deficient iBMKs showed increased IL-6 promoter activity in response to different stimuli including tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), a known inducer of NF-κB signaling, poly I:C, and starvation (Figure 5E). In contrast to IL-6, IFN-β expression was increased in the autophagy-deficient cells by poly I:C but not by TNFα or starvation. Uncomplexed poly I:C significantly increased IL-6 and IFN-β expression, pointing to simultaneous IFN and NF-κB activation. Recently, it was reported that activation of RIG-I signaling activates the mitochondrial protein MAVS by aggregation, which in turn activates IRF3 and NF-κB upon viral infection (Hou et al., 2011). In order to test if the IRF3 activation due to autophagy-deficiency was mediated through MAVS, we expressed increasing amounts of MAVS, which showed a dose-dependent decrease in cell viability (Figure S1A and S1B). We then performed luciferase assays with increasing levels of MAVS expression to see if we could further induce IRF3 signaling (Figure S1C). In general, the reporter activity for IFN-β increased with ectopic MAVS expression in a dose-dependent manner under basal and poly I:C treatment but not starvation. This suggests that the level of MAVS protein, or potentially other RIG-I components, correlates with levels of signaling through the pathway even under basal conditions. To further confirm increased expression of these cytokines, we performed ELISA for IL-6, IFN-α, and IFN-β (Figures 5F, S1D), which showed dramatically increased levels in media from poly I:C treated autophagy-deficient cells, compared to that from the WT.

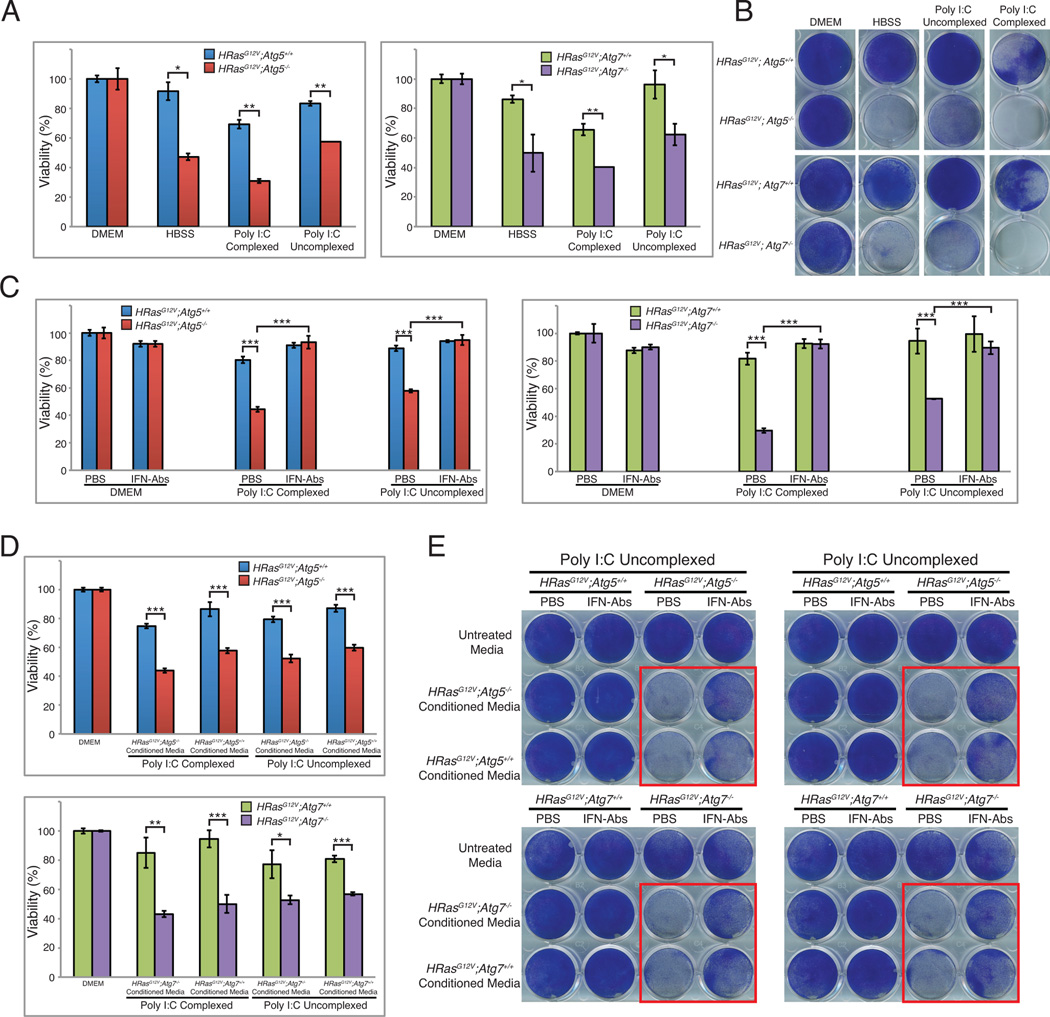

Autophagy defects disrupt proteome composition and prime non-immune cells for innate immunity and the interferon response

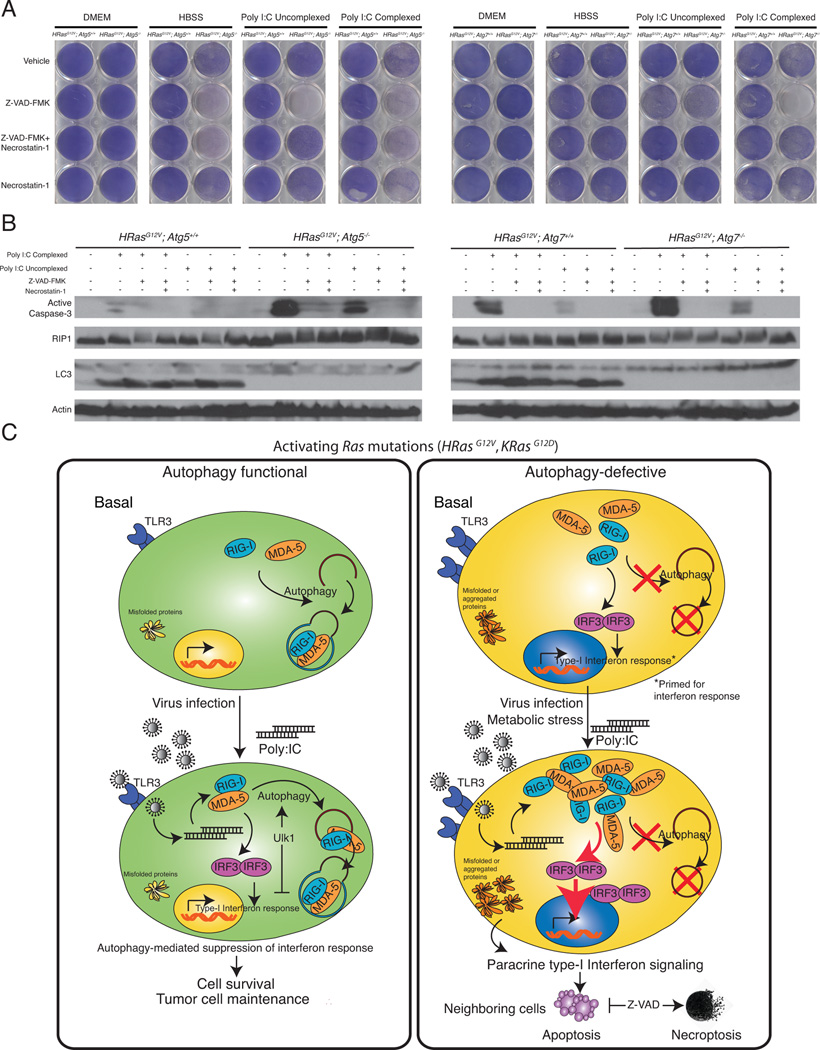

We hypothesized that accumulation of RIG-I-related proteins produced by autophagy defects allows non-immune cells to be primed to mount an innate immune response, leading to cell death. We assessed the viability and clonogenicity of these cells when exposed to starvation or poly I:C and found that autophagy-deficient iBMK cells were more sensitive to all stressors, most prominently complexed poly I:C (Figures 6A, 6B, and S2A). To confirm that cytokines in the media caused the reduced viability, we treated cells with Poly I:C in the presence of neutralizing antibodies against IFN-α and IFN-β, which efficiently rescued the cell death (Figure 6C). Next, we performed conditioned media experiments to determine if interferon acts through a paracrine mechanism. Autophagy-deficient iBMK cells had reduced viability and clonogenicity when given media from either autophagy-competent or –deficient cells that had been treated with poly I:C (Figures 6D and S2B), which was rescued by addition of neutralizing antibodies to the media (Figure 6E, red boxes). IFNα/β activate JAK-STAT signaling, which ultimately increases transcription of interferon-stimulated genes, possibly leading to apoptosis (Stawowczyk et al., 2011). To determine the mechanism of cell death, we blocked apoptotic cell death by treating cells with a pan-caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK. Unexpectedly, cell death was much more pronounced upon treatment with Z-VAD-FMK (Figures 7A and S3A). It was previously shown in macrophages that treatment with poly I:C and Z-VAD-FMK activates programmed necrosis (He et al., 2011). Consistently, we found that treatment with poly I:C in the presence of Z-VAD-FMK amplifies cell death. Addition of the Receptor-interacting serine/threonine-protein kinase 1 (RIP1) inhibitor Necrostatin-1 (Nec-1) effectively reduced this increased cell death while Nec-1 alone did not have any effect (Figures 7A and S3A). Levels of RIP1 confirmed that Nec-1 had available substrate (Figure 7B). We then sought to determine the mechanism of this cell death in response to poly I:C by assessing caspase-3 cleavage. Indeed, we observed higher levels of cleaved caspase-3 in autophagy-deficient cells when treated with complexed poly I:C, consistent with diminished viability and clonogenic survival. Together, these results suggest that autophagy-deficient cells are primed to mount a robust interferon response upon stress stimulus such as RNA-helicase-mediated detection of cytoplasmic dsRNAs. Activation of interferon signaling occurs through a paracrine mechanism, which leads to cell death by apoptosis.

Figure 6. Autophagy defects prime cells for innate immune response and subsequent cell death.

A. Autophagy-deficient cells are more susceptible to metabolic stress or poly I:C treatment. iBMK cells were treated with HBSS, uncomplexed Poly I:C, or complexed Poly I:C and cell viability was examined.

B. Cells treated as in A were allowed to recover in normal medium and assessed for clonogenic survival. Triplicate wells are shown in Figure S2A.

C. Neutralizing antibodies rescue Poly I:C induced cell death. iBMK cells were stimulated with complexed or uncomplexed Poly I:C in the presence or absence of neutralizing antibodies to IFN-α and IFN-β and cell viability was assessed.

D. Autophagy-deficient cells have reduced viability with conditioned media. iBMK cells were stimulated with complexed or uncomplexed Poly I:C and then given fresh media to allow for interferon production. This media was then collected and overlayed onto untreated cells overnight after which cell viability or clonogenic survival was assessed.

E. Neutralizing antibodies rescue cell death in conditioned media. iBMK cells were treated as in D and collected media was mixed with either PBS or neutralizing antibodies to IFN-α and IFN-β and overlayed onto untreated cells overnight upon which cells were assessed for clonogenic survival.

Data is represented as mean ± SD (n=3). n.s.=not significant, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, and ***p<0.001 by unpaired Student’s t-test. Data is representative of at least two independent experiments. See also Figure S2.

Figure 7. Activation of interferon response triggers cell death by apoptosis.

A. Z-VAD-FMK accelerates cell death under poly I:C treatment by activating necroptosis. iBMK cells were pretreated with Z-VAD-FMK, Nec-1, or Z-VAD-FMK+Nec- 1 followed by HBSS, uncomplexed Poly I:C, or complexed Poly I:C. Cells were allowed to recover in normal medium and assessed for clonogenic survival.

B. Poly I:C induces cell death by apoptosis. iBMK cells were treated as in D, lysed, and immunoblotted for the indicated antibodies. β-Actin was used as a loading control.

C. A model for autophagy-mediated immune suppression. In normal cells, autophagy functions to suppress accumulation of RIG-I pathway proteins thereby limiting IRF3 activation and the interferon response. Autophagy deficiency causes deregulation of protein homeostasis and accumulation of RIG-I pathway members, which is sufficient to prime the host cells for interferon response. Upon activation by appropriate stress stimulus, host cells activate paracrine IFN signaling leading to cell death by apoptosis, which when blocked reverts to necroptosis.

Data is represented as mean ± SD (n=3). n.s.=not significant, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, and ***p<0.001 by unpaired Student’s t-test. Data is representative of at least two independent experiments. See also Figure S3.

Discussion

Autophagy promotes the stress survival, growth and aggressiveness of Ras-driven lung cancers (Guo et al., 2013b) by recycling macromolecules to fuel mitochondrial respiration and metabolism (Mathew and White, 2011; Rabinowitz and White, 2010; White, 2013), but the mechanism is still under investigation. In the absence of external nutrients, a selective autophagy-mediated degradation of the cellular proteome may facilitate this process, promoting survival. Recently, a model for selective autophagosome formation was proposed wherein autophagy receptors p62 and NBR1 directly engage ubiquitin-like modifiers (UBLs) for selective autophagosome formation around the cargo in a context-dependent manner (Rogov et al., 2014). In addition, it was shown that autophagosomes are enriched in specific cargo receptors that mediate iron metabolism indicating the selectivity of autophagy substrates (Mancias et al., 2014). However, a comprehensive understanding of the selectivity for autophagy substrates and if or how this impacts cellular function to promote tumor growth, have been lacking.

The finding that autophagy deficiency altered amino acid and mitochondrial metabolism rendering lung cancer cells susceptible to stress (Guo et al., 2013b) raised several important questions. First, does autophagy-mediated protein degradation alter cellular proteome composition? Second, if true, do these autophagy-mediated proteome alterations modify cellular function? While defects in autophagy have been shown to have indirect effects on cells such as compromising the UPS, the extent to which autophagy deficiency affects proteins with long half-lives and its impact of cell survival signaling is unknown (Korolchuk et al., 2009). Herein, we report that in starvation, Atg5 deficiency in HRasG12V-transformed cells significantly altered relative proteins levels of the majority of cellular proteins compared to those in WT cells, revealing the magnitude of the impact of autophagy on protein homeostasis. The major downstream consequence of disruption in protein homeostasis was two-fold. First, when autophagy was functional, there was selective elimination of proteins detrimental for cell survival to stress, while those that support cell survival were preserved. Second, defects in autophagy caused accumulation of putative autophagy substrates, many of which were members of signaling pathways detrimental to cell survival. Moreover, their accumulation was sufficient to mediate cell death, providing an explanation, at least in part, for the requirement of autophagy for tumor maintenance. Importantly, autophagy-deficient cells accumulate levels of PARP family members while depleting their catabolic counterpart, PARG (Figure 3C). This alteration could occur in response to alterations in NAD+ regulation and changes in cellular energy homeostasis and likely leads to increased ADP-ribosylation of PARP targets. Alteration in PARP levels are implicated in NAD+ depletion, mitochondrial dysfunction, inflammatory-response gene expression, senescence and susceptibility to cell death, all of which are phenotypes we and others have observed in autophagy-defective cells.

Most striking was the observation that autophagy defects result in accumulation of proteins such as RIG-I (6.75-fold) and MDA-5 (12.36-fold) that in turn, primed cells for subsequent activation of the innate immune response. Ligand activation of RIG-I induces apoptosis in melanoma cells (Besch et al., 2009). A recent report showed that the autophagy-activating kinase, ULK1 inhibits IRF3 and the interferon response through phosphorylation of stimulator of interferon genes (STING) (Konno et al., 2013). In addition, conditional knockout of the essential autophagy gene FIP200 elevates interferon-response in mammary tumors (Wei et al., 2011). Hence, de-repression of innate immunity with autophagy deficiency was not surprising, although whether accumulation of pathway proteins in tumor cells was sufficient to activate interferon response was unclear.

The highlight of our study is the finding that selective protein accumulation due to autophagy defects alone is sufficient to prime cells for the interferon response, that upon activation by ligands lead to cell death by apoptosis via a paracrine mechanism. It was recently shown that in the absence of viral infection, RIG-I induction alone could trigger apoptosis-independent cell death via AKT-mTOR inhibition in an AML model, supporting our findings (Li et al., 2014). This inhibition also activated autophagy, possibly as a stress response indicating the importance of autophagy in this setting. Inherent metabolic stress and cell death in autophagy-deficient cancer cells can lead to incompletely digested nucleic acids that may mimic an anti-viral-like inflammatory response leading to reduced tumor burden. Indeed, failure to degrade mitochondrial DNA through mitophagy causes inflammation and heart failure in mice (Oka et al., 2012), and DNA and toxic radicals from depolarized mitochondria, a consequence of defective autophagy, activate inflammasomes (Zhou et al., 2011), producing proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and IL-18. Alternatively, autophagy may be required to degrade the protein components of inflammatory signaling as a negative feedback mechanism that is absent in autophagy-deficient cells, explaining the activated state of these pathways. Regardless, our data suggests that accumulation of autophagy substrates in autophagy-deficient cells may contribute to activation of the interferon response leading to apoptosis, and warrants further investigation.

In stark contrast to autophagy substrates, proteins whose levels were refractory to autophagy-mediated downregulation were found to be essential for maintaining autophagy-related processes, such as vesicle mediated trafficking, endocytosis and lysosomal protein degradation, among others. While autophagy machinery has been known to interact with vesicle trafficking components (Behrends et al., 2010), their selective retention in starvation-induced autophagy was not known. This underscores the importance of selective autophagy as a mechanism to preserve the autophagy process itself and cell survival in starvation. Strategies to inhibit these processes may provide additional opportunities to augment cell death by autophagy-inhibition for enhanced therapeutic efficacy.

In summary, our results indicate that autophagy plays a major role in modulating the cellular proteome and that deregulation of this process alters cell function. Autophagy-mediated suppression of the anti-tumor immune response may be a mechanism by which autophagy supports tumor growth (Figure 7C). We report that autophagy specifically targets mediators of inflammation to suppress inflammatory pathways, unraveling an important consequence of defective autophagy in activating the innate immune and interferon responses. This selective autophagic degradation may potentially explain the increased inflammation in mice with tumor-specific autophagy-defects (Guo et al., 2011; Guo et al., 2013a). Together, these observations suggest that autophagy selectively targets substrates to maintain cell survival and protein homeostasis, the deregulation of which has the potential to alter signaling pathways critical for survival in Ras-driven cancers. Autophagy substrates and autophagy-resistant proteins identified here will serve as biomarkers for monitoring autophagy function in clinical settings.

Experimental Procedures

Tissue Culture, SILAC, Viability and Clonogenic Assays

All cell lines were cultured as previously described (Guo et al., 2011; Guo et al., 2013a). SILAC labeling was performed using heavy arginine (613C, 415N) and lysine (613C) (Pierce, cat. # 1860972, 89990). Cell viability was assessed by Vi-CELL cell viability analyzer (Beckman Coulter, Inc.). For clonogenic assays, cells were treated, allowed to recover for two days in normal medium, fixed, and stained with Giemsa.

Luciferase Assays

Luciferase assays were performed as described previously (Mathew et al., 2009). A detailed description can be found in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Mass Spectrometry

SILAC-labeled cells were subjected to a starvation time course and lysed. Extracts were trypsin digested and separated by SCX or OG fractionation. Peptide fractions were subjected to reverse-phase nano-LC-MS and MS/MS performed on Nano Ultra 2D plus UPLC system (Eksigent, Dublin, CA) coupled to an LTQ-Orbitrap™ hybrid MS (ThermoFisher Scientific, San Jose, CA). The raw MS dataset acquired for this study can be downloaded at the following URL: https://chorusproject.org/anonymous/download/experiment/28d353ecd5924727900e231d0a11ecc5

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Autophagy selectively remodels the majority of the cellular proteome in starvation

Proteins that facilitate autophagy are preserved by starvation-induced autophagy

Autophagy prevents accumulation of pro-inflammatory signaling pathway components

Autophagy defects prime cells for the interferon response

Acknowledgements

We thank members of the White and Rabinowitz laboratories for insightful suggestions. We thank Drs. Z. J. Chen (UT Southwestern Medical Center, TX) for IFNβ-luciferase and FLAG-MAVS plasmids, C. Gelinas (Rutgers University, NJ) for pIL6κB-Luc plasmid, J. Y. Guo for generating TDCLs, and J. Y. Guo and H. Y. Chen for generating iBMK cell lines. We also thank C. Hulderman and J. Park for assistance with Western blotting and cell culture. This work was supported by grants from NIH (R37 CA53370 and R01 CA130893 to E. W., RC1 CA147961 and R01 CA163591 to E. W. and J. D. R), and DOE (DE-AC05-06OR23100 to S. H.)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Contributions

R.M., S.K., D.H.P., and E.W designed the experiments. R.M. and S.K performed the experiments and analyzed the data. S.H. performed the statistical analysis. R.M., S.K., D.H.P and E.W. interpreted the data and prepared the manuscript. J.D.R. provided advice.

References

- Barbhuiya MA, Sahasrabuddhe NA, Pinto SM, Muthusamy B, Singh TD, Nanjappa V, Keerthikumar S, Delanghe B, Harsha HC, Chaerkady R, et al. Comprehensive proteomic analysis of human bile. Proteomics. 2011;11:4443–4453. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201100197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrends C, Sowa ME, Gygi SP, Harper JW. Network organization of the human autophagy system. Nature. 2010;466:68–76. doi: 10.1038/nature09204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besch R, Poeck H, Hohenauer T, Senft D, Hacker G, Berking C, Hornung V, Endres S, Ruzicka T, Rothenfusser S, et al. Proapoptotic signaling induced by RIG-I and MDA-5 results in type I interferon-independent apoptosis in human melanoma cells. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:2399–2411. doi: 10.1172/JCI37155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C, Zhang J, Han M, Ma J, Zhang W, Wu S, Liu K, Xie H, He F, Zhu Y. SILVER: an efficient tool for stable isotope labeling LC-MS data quantitative analysis with quality control methods. Bioinformatics. 2013 doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBerardinis RJ, Mancuso A, Daikhin E, Nissim I, Yudkoff M, Wehrli S, Thompson CB. Beyond aerobic glycolysis: transformed cells can engage in glutamine metabolism that exceeds the requirement for protein and nucleotide synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:19345–19350. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709747104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt K, Mathew R, Beaudoin B, Bray K, Anderson D, Chen G, Mukherjee C, Shi Y, Gelinas C, Fan Y, et al. Autophagy promotes tumor cell survival and restricts necrosis, inflammation, and tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:51–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo JY, Chen HY, Mathew R, Fan J, Strohecker AM, Karsli-Uzunbas G, Kamphorst JJ, Chen G, Lemons JM, Karantza V, et al. Activated Ras requires autophagy to maintain oxidative metabolism and tumorigenesis. Genes Dev. 2011;25:460–470. doi: 10.1101/gad.2016311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo JY, Karsli-Uzunbas G, Mathew R, Aisner SC, Kamphorst JJ, Strohecker AM, Chen G, Price S, Lu W, Teng X, et al. Autophagy suppresses progression of K-ras-induced lung tumors to oncocytomas and maintains lipid homeostasis. Genes Dev. 2013a;27:1447–1461. doi: 10.1101/gad.219642.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo JY, Xia B, White E. Autophagy-mediated tumor promotion. Cell. 2013b;155:1216–1219. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He S, Liang Y, Shao F, Wang X. Toll-like receptors activate programmed necrosis in macrophages through a receptor-interacting kinase-3-mediated pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:20054–20059. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116302108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou F, Sun L, Zheng H, Skaug B, Jiang QX, Chen ZJ. MAVS forms functional prion-like aggregates to activate and propagate antiviral innate immune response. Cell. 2011;146:448–461. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttlin EL, Jedrychowski MP, Elias JE, Goswami T, Rad R, Beausoleil SA, Villen J, Haas W, Sowa ME, Gygi SP. A tissue-specific atlas of mouse protein phosphorylation and expression. Cell. 2010;143:1174–1189. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konno H, Konno K, Barber GN. Cyclic dinucleotides trigger ULK1 (ATG1) phosphorylation of STING to prevent sustained innate immune signaling. Cell. 2013;155:688–698. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korolchuk VI, Mansilla A, Menzies FM, Rubinsztein DC. Autophagy inhibition compromises degradation of ubiquitin-proteasome pathway substrates. Mol Cell. 2009;33:517–527. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li XY, Jiang LJ, Chen L, Ding ML, Guo HZ, Zhang W, Zhang HX, Ma XD, Liu XZ, Xi XD, et al. RIG-I Modulates Src-Mediated AKT Activation to Restrain Leukemic Stemness. Mol Cell. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lock R, Roy S, Kenific CM, Su JS, Salas E, Ronen SM, Debnath J. Autophagy facilitates glycolysis during Ras-mediated oncogenic transformation. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22:165–178. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-06-0500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancias JD, Wang X, Gygi SP, Harper JW, Kimmelman AC. Quantitative proteomics identifies NCOA4 as the cargo receptor mediating ferritinophagy. Nature. 2014;509:105–109. doi: 10.1038/nature13148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew R, Karantza-Wadsworth V, White E. Role of autophagy in cancer. Nature reviews. Cancer. 2007a;7:961–967. doi: 10.1038/nrc2254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew R, Karp CM, Beaudoin B, Vuong N, Chen G, Chen HY, Bray K, Reddy A, Bhanot G, Gelinas C, et al. Autophagy suppresses tumorigenesis through elimination of p62. Cell. 2009;137:1062–1075. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew R, Kongara S, Beaudoin B, Karp CM, Bray K, Degenhardt K, Chen G, Jin S, White E. Autophagy suppresses tumor progression by limiting chromosomal instability. Genes Dev. 2007b;21:1367–1381. doi: 10.1101/gad.1545107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew R, White E. Autophagy, stress, and cancer metabolism: what doesn't kill you makes you stronger. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2011;76:389–396. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2012.76.011015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima N. Autophagy: process and function. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2861–2873. doi: 10.1101/gad.1599207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima N, Komatsu M. Autophagy: renovation of cells and tissues. Cell. 2011;147:728–741. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz-Fontela C, Macip S, Martinez-Sobrido L, Brown L, Ashour J, Garcia-Sastre A, Lee SW, Aaronson SA. Transcriptional role of p53 in interferon-mediated antiviral immunity. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2008;205:1929–1938. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oka T, Hikoso S, Yamaguchi O, Taneike M, Takeda T, Tamai T, Oyabu J, Murakawa T, Nakayama H, Nishida K, et al. Mitochondrial DNA that escapes from autophagy causes inflammation and heart failure. Nature. 2012;485:251–255. doi: 10.1038/nature10992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong SE, Blagoev B, Kratchmarova I, Kristensen DB, Steen H, Pandey A, Mann M. Stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture, SILAC, as a simple and accurate approach to expression proteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2002;1:376–386. doi: 10.1074/mcp.m200025-mcp200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowitz JD, White E. Autophagy and metabolism. Science. 2010;330:1344–1348. doi: 10.1126/science.1193497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao S, Tortola L, Perlot T, Wirnsberger G, Novatchkova M, Nitsch R, Sykacek P, Frank L, Schramek D, Komnenovic V, et al. A dual role for autophagy in a murine model of lung cancer. Nature communications. 2014;5:3056. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogov V, Dotsch V, Johansen T, Kirkin V. Interactions between Autophagy Receptors and Ubiquitin-like Proteins Form the Molecular Basis for Selective Autophagy. Mol Cell. 2014;53:167–178. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeldt MT, O'Prey J, Morton JP, Nixon C, MacKay G, Mrowinska A, Au A, Rai TS, Zheng L, Ridgway R, et al. p53 status determines the role of autophagy in pancreatic tumour development. Nature. 2013;504:296–300. doi: 10.1038/nature12865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son J, Lyssiotis CA, Ying H, Wang X, Hua S, Ligorio M, Perera RM, Ferrone CR, Mullarky E, Shyh-Chang N, et al. Glutamine supports pancreatic cancer growth through a KRAS-regulated metabolic pathway. Nature. 2013;496:101–105. doi: 10.1038/nature12040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stawowczyk M, Van Scoy S, Kumar KP, Reich NC. The interferon stimulated gene 54 promotes apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:7257–7266. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.207068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strohecker AM, Guo JY, Karsli-Uzunbas G, Price SM, Chen GJ, Mathew R, McMahon M, White E. Autophagy sustains mitochondrial glutamine metabolism and growth of BrafV600E-driven lung tumors. Cancer discovery. 2013;3:1272–1285. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, Paulovich A, Pomeroy SL, Golub TR, Lander ES, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahasi K, Suzuki NN, Horiuchi M, Mori M, Suhara W, Okabe Y, Fukuhara Y, Terasawa H, Akira S, Fujita T, et al. X-ray crystal structure of IRF-3 and its functional implications. Nature structural biology. 2003;10:922–927. doi: 10.1038/nsb1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vadlamudi RK, Shin J. Genomic structure and promoter analysis of the p62 gene encoding a non-proteasomal multiubiquitin chain binding protein. FEBS Lett. 1998;435:138–142. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01021-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei H, Wei S, Gan B, Peng X, Zou W, Guan JL. Suppression of autophagy by FIP200 deletion inhibits mammary tumorigenesis. Genes Dev. 2011;25:1510–1527. doi: 10.1101/gad.2051011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White E. Exploiting the bad eating habits of Ras-driven cancers. Genes Dev. 2013;27:2065–2071. doi: 10.1101/gad.228122.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S, Wang X, Contino G, Liesa M, Sahin E, Ying H, Bause A, Li Y, Stommel JM, Dell'antonio G, et al. Pancreatic cancers require autophagy for tumor growth. Genes & development. 2011;25:717–729. doi: 10.1101/gad.2016111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou R, Yazdi AS, Menu P, Tschopp J. A role for mitochondria in NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Nature. 2011;469:221–225. doi: 10.1038/nature09663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.