Abstract

Background

Amebic liver abscess (ALA) is endemic in Bangladesh since historical age but its epidemiology and sociodemographic determinants are not well described in the literatures. This paper focuses on the endemicity, sociodemographic determinants and clinical outcomes of ALA patients from certain northern districts in Bangladesh. Ninety hospitalized ALA patients enrolled from 6 northern districts of Bangladesh during July 2008 to June 2010 were analyzed.

Findings

Clinical presentations of ALA was initially substantiated by ultrasound imaging and later confirmed by detection of small subunit rRNA gene of E. histolytica using a Real Time PCR. Structured questionnaire and data sheet were used to record sociodemographic characteristics, clinical presentations and outcomes. Patients were followed for immediate and late treatment outcomes up to 2 years since diagnosis. Northern districts those situated on the Ganges basin were noted as endemic areas. Male significantly outnumbered the female with a male to female ratio of 21:1 and majority of patients (58%) were in their 3rd and 4th decades. A significant (21%) number of patients were aborigines despite their ethnic minority as population under investigation and overall 68% belonged to low socioeconomic group. Habit of indigenous alcohol consumption was very high (78%) among ALA patients with overwhelming majority was illiterate (74.44%) and from rural population (70%). Fever with right hypochondriac pain of variable duration was the principal presenting complains. Gross fluid derangements including pleural effusion, edema and ascities were observed in 39% cases and 6% had rupture of abscess. All patients were treated with standard antimicrobial regimen and discharged with initial recovery. Recurrent attack was observed in 6% cases and 3 (3.33%) patients died during 2 years follow-up period. Complicated (37.78%) ALA patients showed significant Odds ratio (P < 0.05) for major sociodemographic determinants in comparison to non-complicated patients.

Conclusions

Amebic liver abscess is endemic in certain northern districts of Bangladesh especially on the Ganges basin with relatively high prevalence among aborigines. Rural habitat, ethnicity (Aborigine) and habit of indigenous alcohol consumption were found to be strong determinants, especially for complicated ALA, which were associated with different grades of morbidity and a few mortalities.

Keywords: Amebic liver abscess, E. histolytica, Sociodemographic determinants, Clinical outcomes, Bangladesh

Background

Amebic liver abscess (ALA) is an extra intestinal form of amebiasis and described since antiquity. It was first recognized as a deadly disease by Hippocrates (460–377 B.C.) and Losch first linked E. histolytica as a cause of this disease [1, 2]. In 1912, Leonard Rogers designated emetine as the first effective treatment for amebiasis [3]. Brompt revealed in 1925 that E. histolytica and E. dispar are morphologically identical but only E. histolytica is pathogenic for humans [4]. E. histolytica was first recognized as an agent of amebic liver abscess in 1945 by famous Robert Koch [5].

Global burden of amebiasis and amebic liver abscess has not been estimated precisely till to date. In older textbooks it is often stated that 10% of the world’s population is infected with E. histolytica but it is now known that at least 90% of these infections are due to E. dispar [4]. The last estimate on the global magnitude of this disease was made more than two decades ago [6]. According to WHO fact sheet, it is prevalent throughout the under developed and developing nations of the tropics with up to 50 million true E. histolytica infections and approximately 100,000 deaths occur each year mostly from liver abscesses or other complications [7]. Despite its medical importance, little is known about the current epidemiology of amebic liver abscess but it is assumed that the disease is prevalent within E. histolytica endemic countries. A few sporadic reports and hospital records claimed that amebic liver abscess is also endemic in Bangladesh but its exact annual incidence has not been figured out. International center for diarrhoeal diseases research, Bangladesh (ICDDR.B) has done a few extensive studies but those were mostly on intestinal amebiasis [8].

Rajshahi Medical College Hospital (RMCH) is a tertiary care teaching hospital homing for patients of many northern districts and its records show that a significant number of ALA patients are being treated over the years. A few investigators documented some sociodemographic aspects of these patients attended at RMCH, however, spectra of morbidity and mortality of ALA were not reported in those studies [9, 10]. More over, precise geographical distribution of ALA cases in the northern areas was not recorded by any investigator. This paper presents sociodemographic determinants, clinical presentations and treatment outcomes of amebic liver abscess patients with emphasis on its endemicity in certain northern districts of Bangladesh.

Findings

Methods

Clinically suspected liver abscess patients presented with fever and right hypochondriac pain those who were admitted into the Rajshahi Medical College Hospital, Bangladesh during July 2008 to June 2010 were included. Informed written consent was obtained from each patient and the protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Institute of Biological Sciences (IBSc), University of Rajshahi, Bangladesh. All clinical and sociodemographic information of patients were recorded using structured questionnaires and data recording sheet. Privacy and confidentiality was maintained during collection, compilation and analysis of data.

Presence of space occupying lesion in the liver detected by ultrasound imaging substantiated initial clinical suspicion for ALA which was later confirmed as amebic liver abscess through detection of small-subunit rRNA (ssu rRNA) gene of E. histolytica in liver abscess aspirates by Real Time PCR. The number of confirmed ALA patients was 90.

Real time PCR

Liver abscess pus (1 μL) was used as sample for PCR following standard procedure as described by Roy et al. [11]. The oligonucleotide primers and TaqMan probes (Eurogentec, United Kingdom) were designed to specifically amplify a 135 bp fragment inside the 16S-like small-subunit rRNA gene of E. histolytica (Gene Bank accession number X64142). Amplification reactions were performed in a volume of 25 μL with Qiagen super mix. Amplification results were analyzed using i-Cycler software.

Results

Epidemiology

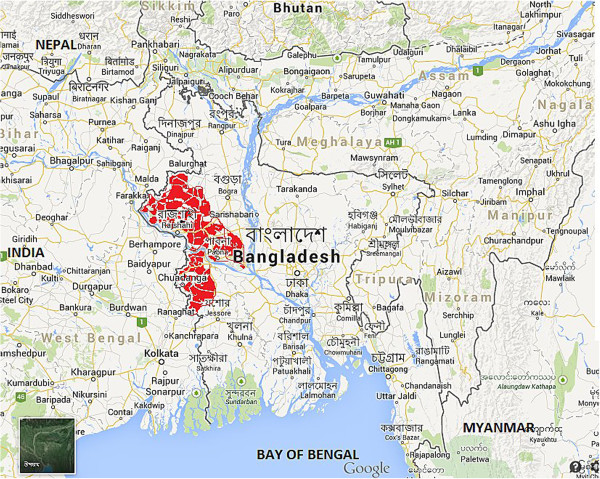

Amebic liver abscess patients of this study were from 6 northern districts situated in the Ganges basin of Bangladesh (Figure 1). The highest number of ALA cases was recorded from Rajshahi (34.44%) followed by Naogaon (27.78%), Chapainawabgonj (16.67%), Kushtia (10%), Natore (7.78%) and Pabna (3.33%).

Figure 1.

Geographical distribution of amebic liver abscess endemic areas (marked in red color) of northern districts situated on the Ganges basin in Bangladesh. (Source: https://www.google.com.bd/maps; accessed on 29/08/2014).

Sociodemographic characteristics

Gender distribution showed high male preponderance with a male to female ratio of approximately 21.5:1. Patients were grouped into 21–29 years, 30–39 years, 40–49 years, 50–59 years, and ≥ 60 years for their age groups with a mean age of 44.3 years. Majority of cases (58%) were from 3rd and 4th decade of their life. Overwhelming majority of ALA patients was illiterate (74.44%), from rural habitat (70%) with low socioeconomic (67.67%) condition and alcoholic (78.77%). A significant number of patients (21.11%) were from aborigine (Santal), which represents only about 2% of population under investigation. History of drug addiction (cannabis) was noted only in 2.22% patients (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic profile of amebic liver abscess patients (n = 90)

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 86 (95.56) |

| Female | 4 (4.44) |

| M:F ratio | 21.5:1 |

| Mean age in years | 44.3 |

| Socioeconomic class | |

| Low class | 60 (67.67) |

| Lower middle class | 30 (32.33) |

| Education | |

| Illiterate | 67 (74.44) |

| Literate | 23 (25.56) |

| Habitat | |

| Rural | 63 (70) |

| Urban | 27 (30) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Ethnic majority (Inhabitant) | 71 (78.89) |

| Ethnic minority (Aborigine) | 19 (21.11) |

| Habit of Alcohol consumption | |

| Alcoholics | 70 (77.78) |

| Non-alcoholics | 20 (22.22) |

| Drug addiction | |

| Addict | 02 (2.22) |

| Non addict | 88 (97.78) |

Clinical presentations, complications and outcomes

Amebic liver abscess patients presented with fever (98.89%), right hypochondriac pain (76.67%), abdominal tenderness (97.78%) and dysentery (7.78%). Past history of dysentery and antibiotic intake before enrollment were noted in 13.33% and 70% cases respectively. A significant number of patients 29 (32.22%) developed hemodynamic changes (edema, effusion and ascites), while 4 (4.11%) persons had rupture of liver abscess and 1 (1.11%) had bronchopulmonary fistula. During 2 years post-treatment follow-up, 6 (6.67%) patients developed recurrent infections while 3 (3.33%) persons died (Table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical presentation, complications and treatment outcomes of amebic liver abscess patients (n = 90)

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Clinical features | |

| Fever | 89 (98.89) |

| Right hypochondriac pain | 69 (76.67) |

| Abdominal tenderness | 88 (97.78) |

| Dysentery | 07 (7.78) |

| Past history of | |

| Dysentery | 12 (13.33) |

| Antibiotics | 63 (70) |

| Complications | |

| Hemodynamic changes (edema, effusion & ascites) | 29 (32.22) |

| Rupture of liver abscess | 4 (4.44) |

| Bronchopulmonary fistula | 1 (1.11) |

| Treatment outcomes | |

| Initial recovery | 90 (100) |

| Recurrent infections within 2 years follow-up | 6 (6.67) |

| Death within 2 years follow-up | 3 (3.33) |

Correlation of sociodemographic determinants to the gravity of illness

ALA patients were divided into two groups; complicated and non-complicated in order to correlate the sociodemographic determinants to the gravity of illness. Out of 90 patients, 34 were categorized as complicated ALA cases who developed gross hemodynamic derangements, rupture of liver abscess and bronchopulmonary fistula. Complicated ALA cases showed significant odds ratio (P < 0.05) for major determinants like rural habitat, aborigine and alcohol consumption in comparison to 56 non-complicated ones (Table 3).

Table 3.

Correlation of sociodemographic determinants to the gravity of illness

| Determinants | Gravity of illness | Odds ratio | 95% CI | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complicated ALA n (%) | Non-complicated ALA n (%) | ||||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 33 (97.06) | 53 (94.64) | 0.53 | 0.05–5.36 | 0.59 |

| Female | 01 (2.94) | 03 (5.36) | |||

| Ethnicity | |||||

| Aborigine | 17 (50) | 02 (3.57) | 27.00 | 5.66–128.91 | 0.001 |

| Native | 17 (50) | 54 (96.43) | |||

| Habitat | |||||

| Rural | 33 (97.06) | 30 (53.57) | 13.75 | 2.99–63.04 | 0.007 |

| Urban | 01 (2.94) | 26 (46.43) | |||

| Alcohol | |||||

| Alcoholic | 29 (85.29) | 41 (73.21) | 16.95 | 2.15–133.62 | 0.007 |

| Non alcoholic | 05 (14.71) | 15 (26.79) | |||

Discussion

Historically amebiasis, both amebic colitis and amebic liver abscess have been endemic disease among people living in the Ganges basin of both India and Bangladesh probably due to the fact of fecal-oral transmission of these diseases. Catchment areas of the present study is within the Bangladeshi part of Ganges basin and our findings have corroborated with previous investigations and supports that ALA is endemic in certain northern districts of Bangladesh especially those situated in the Ganges basin [9, 10, 12].

Gender distribution in ALA cases shows a very high male preponderance and has coincided with most of the previous studies [13–15]. The fact that the gender discrimination can be correlated with iron deficiency state commonly present among rural females that brings an inhibitory effect to E. histolytica growth [16]. Further, complement mediated killing of E. histolytica was found more pronounced in female than male by some investigators [17] and failure to produce early cytokine like IFN γ was documented in case of male in mouse model [18]. Illiteracy, low socioeconomic condition and rural habitat are all coined together to poor hygiene and concomitant increased vulnerability to develop such pathology, which was also noted in other studies [19–21].

Most striking finding in the present investigation was a large number of cases (21%) were from small aborigine group which represents only 2.34% of total population in this study [22]. Few earlier local studies also showed such cluster of ALA cases among aborigines [9, 10]. Low socioeconomic condition with malnutrition, regular consumption of indigenous alcohol, which is a part of their social custom, poor sanitation as well as less access to health care facility are all essential factors that can be correlated with high ALA incidence among this ethnic minority population. Alcoholic persons develop fatty liver and low cellular immunity which lead to deposition of large amount of iron that facilitates E. histolytica growth in the liver parenchyma leading to liver abscess has been revealed by Makkar et al. [23] and this correlation has been reinforced in our findings support this too.

As far as the clinical presentations of ALA patients are concerned, overwhelming majority of patients presented with typical features of fever, right hypochondriac pain and abdominal tenderness of varying duration that are similar to other previous findings [10, 12, 14]. Association of concomitant dysentery (7.78%) or past history of dysentery (13.33%) were both noted in very low number of patients and similar low prevalence of colitis among ALA was also found by others [13, 15]. This raises the long controversial issue of whether same or different strains of parasite causing amebic colitis and liver abscess.

Different grades of morbidity including gross hemodynamic derangements (38.89%), rupture of abscess (4.44%) and bronchopulmonary fistula (1.11%) were noted among ALA patients and similar complications were also observed in other studies [12, 20]. Patients with these complications were categorized as complicated ALA and found to have strong correlation with major sociodemographic determinants like rural habitat, aborigine and alcohol consumption. All patients had initial cure with treatment by standard antimicrobial drugs but in the course of 2 years follow-up, 3 ALA cases died and 6 (6.67%) developed recurrent infections, which refer to fatal outcome as well as incomplete immunity involved in this chronic illness.

Conclusions

Present investigation has documented that amebic liver abscess is prevalent and endemic in the northern districts situated on the Ganges basin in Bangladesh. Illiteracy, rural habitat, low socioeconomic condition, habit of indigenous alcohol consumption and male in their active age are important sociodemographic determinants for amebic liver abscess and majority of these factors has significant association with morbid complications in ALA. It leads to a significant number of morbidities and a few mortality, so early diagnosis and timely intervention are essential measures to reduce the detrimental outcomes. It is expected that findings of present investigation would help to bridge the knowledge gap in regards to the epidemiology, risk factors and clinical outcomes of amebic liver abscess.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Professor Emiritus Dr. Nadakavukaren, department of Biology of Illinois State University, USA for his time in editing the language of the manuscript. Dr. Md. Jawadul Haque, Professor of Community Medicine, Rajshahi Medical College is also acknowledged for his kind assistance in data analysis.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

FA and RH conceived and designed the study. MAS contributed for editing and critical review of the manuscript. IM was responsible for patient care and follow-up. PH and RH have supervised the study and MK has done the laboratory tests. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Faisal Alam, Email: faisal_imm@yahoo.com.

Md Abdus Salam, Email: drsalamrmc@yahoo.com.

Pervez Hassan, Email: hassanpru1@gmail.com.

Iftekhar Mahmood, Email: i_mahmood@live.com.

Mamun Kabir, Email: mkabir69@yahoo.com.

Rashidul Haque, Email: rhaque@icddrb.org.

References

- 1.Adams F. The Genuine Works of Hippocrates. Vol. 1. New York: W Wood and Sydenham Company, London, UK; 1886. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Losch F. Massentafle Entwickenlong von amebon in dickdarm. Arch F Path Anat. 1875;65:196–211. doi: 10.1007/BF02028799. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rogers L. The rapid cure of amoebic dysentery and hepatitis by hypodermic injections of soluble salts of emetine. Brit Med J. 1912;1:14–24. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.2686.1424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brompt EE tude sommaire de I “Entamoeba dispar” n sp. Amibe a kystes quadrinucles’es parasite de I’ homme. Bull Acad Med (Paris) 1925;94:943–952. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koch R, Gaffky G. Bericht uber die Thatigkeit der zur Erforchung der Cholera in Jahre 1883 nach Egyten und Indien entsandten Kommission Arb. A.d. Kaiserf Gesundherstsamte, III, 1. 1887. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walsh JA. Problems in recognition and diagnosis of amebiasis. Estimation of the global magnitude of morbidity and mortality. Rev infect Dis. 1986;66:228–238. doi: 10.1093/clinids/8.2.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.WHO Scientific Working Group Parasitic Related Diarrheas. Bull world health Organization. 1980;58(6):819–830. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haque R, Duggal P, Ali IKM. Innate and acquired resistance to amoebiasis in Bangladeshi children. J Infect Dis. 2002;186:547–552. doi: 10.1086/341566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Islam QT, Ekram ARMS, Ahmed MI, Alim MA, Haque MA, Uddin MR, Ali ASMS, Azizul MH. Pyogenic liver abscess and indigenous alcohol consumption. Teachers Association Journal Rajshahi. 2005;18(1):21–24. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Siddiqui MA, Ekram ARMS, Islam QT, Haque MA, Masum QAAI. Clinico-pathological profile of liver abscess in a teaching hospital. Teachers Association Journal Rajshahi. 2008;21(8):46–48. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roy S, Kabir M, Mondal D, Ali IKM, Petri WA, Haque R. Real time PCR assay for diagnosis of Entamoeba histolytica infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(5):2168–2172. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.5.2168-2172.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharma N, Sharma A, Varma S, Lal A, Singh V. Amoebic liver abscess in the medical emergency of a North Indian hospital. BMC Res Notes. 2010;3:21. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-3-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hira PR, Iqbal J, Ali F, Philip R, Grover S. Invasive amebiasis: challeges in diagnosis in non endemic country (Kuwait) Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2001;65(4):341–345. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2001.65.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoffner RJ, Kilaghbian T, Henderson SO. Common presentation of amebic liver abscess. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;34:351–355. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0644(99)70130-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Congly SE, Shaheen AA, Medlings L, Kaplan GG, Myers RP. Amoebic liver abscess in USA: a population based study of incidence, temporal trends and mortality. Liver Int. 2011;31(8):1191–1198. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cruz-Castañeda A, López-Casamichana M, Olivares-Trejo JJ. Entamoeba histolytica secretes two haem-binding proteins to scavenge haem. Biochem J. 2011;434(1):10. doi: 10.1042/BJ20100897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stanley S, Jr, Margaret S, Minghe C, Guo J, Atkinson J, Samuel L. Short report: differences in complement-mediated killing of Entamoeba histolytica between men and women—an explanation for the increased susceptibility of invasive amebiasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;78(6):922–923. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lotter H, Jacobs T, Gawroski I, Tannich E. Sexual dimorphism in the control of amoebic liver abscess in a mouse model of disease. Infect Immun. 2006;74(1):118–124. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.1.118-124.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shamsuzzaman SM, Haque R, Petri WA. Socioeconomic status, clinical features, laboratory and parasitological findings of hepatic amebiasis patients – a hospital based prospective study in Bangladesh. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2000;31(2):399–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seeto RK, Rockey DC. Amebic liver abscess: epidemiology, clinical features and outcome. West J Med. 1999;170:104–109. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blessman J, Van LP, Tanich E. Epidemiology of amebiasis in a region of high incidence of amebic liver abscess in central Vietnam. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2002;66(5):578–583. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2002.66.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Banglapedia [http://www.bpedia.org/R_0079.php] accessed on 25/11/2013

- 23.Makkar RP, Sachdev GK, Malhotra V. Alcohol consumption, hepatic iron load and the risk of amoebic liver abscess: a case–control study. Intern Med. 2003;42(8):644–649. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.42.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]