Abstract

Endothelial cells (EC) closely interact with circulating lymphocytes. Aggression or activation of the endothelium leads to an increased shedding of EC microparticles (MP). Endothelial MP (EMP) are found in high plasma levels in numerous immunoinflammatory diseases, e.g. atherosclerosis, sepsis, multiple sclerosis and cerebral malaria, supporting their role as effectors and markers of vascular dysfunction. Given our recently described role for human brain microvascular endothelial cells (HBEC) in modulating immune responses we investigated how HBEC-derived MP could interact with and support the proliferation of T cells. Like their mother cells, EMP expressed molecules important for antigen presentation and T cell co-stimulation, i.e., β2-microglobulin, MHC II, CD40 and ICOSL. HBEC were able to take up fluorescently labeled antigens with EMP also containing fluorescent antigens suggestive of antigen carryover from HBEC to EMP. In co-cultures, fluorescently labeled EMP from resting or cytokine-stimulated HBEC formed conjugates with both CD4+ and CD8+ subsets, with higher proportions of T cells binding EMP from cytokine stimulated cells. The increased binding of EMP from cytokine stimulated HBEC to T cells was VCAM-1 and ICAM-1-dependent. Finally, in CFSE T cell proliferation assays using anti-CD3 mAb or T cell mitogens, EMP promoted the proliferation of CD4+ T cells and that of CD8+ T cells in the absence of exogenous stimuli and in the T cell mitogenic stimulation. Our findings provide novel evidence that EMP can enhance T cell activation and potentially ensuing antigen presentation, thereby pointing towards a novel role for MP in neuro-immunological complications of infectious diseases.

Introduction

The EC that line the microvasculature, are in constant contact with blood cells such as T lymphocytes. CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes play a critical role in cellular immunity functioning synergistically to mount immune responses and eradicate infection. Nevertheless, the induction of adaptive cellular immunity is a function of professional antigen-presenting cells (APC) such as dendritic cells (DC). APC provide signal 1 (peptide-MHC), signal 2 (co-stimulatory molecules), and signal 3 (instructive cytokines) to naive T cells upon antigen encounter (1).

A body of evidence supports the role of EC as APC (2-5) with the hypothesis based upon the intimate interactions between EC and T cells during their transendothelial migration to lymph nodes or peripheral tissues. Moreover, EC may also qualify as APC as they express MHC antigens, co-stimulatory molecules (3, 5), and secrete cytokines (6). T cell-EC interactions are central in diseases such as multiple sclerosis (MS), cerebral malaria (CM) and viral neuropathologies, although the precise mechanisms underlying these interactions remain unknown (7-9). We have previously demonstrated that HBEC take up antigens by macropinocytosis (5) and, in a CM model, can adopt antigens from Plasmodium infected red blood cells, thereby becoming a target for the immune response (10).

EC express members of the immunoglobulin superfamily, including ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 that bind to leukocyte cell-surface antigens (11). ICAM-1 is a receptor for leukocyte cell surface β2 integrins such as LFA-1 and Mac-1 playing a key role in the adhesion and transmigration of blood leukocytes (12), while VCAM-1 is the endothelial receptor for VLA-4 (α4β1) and α4β7 (12, 13). HBEC are now known to express markers relevant for antigen presentation and T cell activation such as β2-microglobulin (MHC I), MHC II, ICOSL and CD40 (2, 5, 14-16). More recently, HBEC have been shown to display the potential for allo-antigen presentation (5).

Membrane vesiculation is a general physiological process that leads to the release of plasma membrane cell vesicles, called microparticles (MP). MP, a heterogeneous population of submicron elements, range in size from 100-1000 nm (17). MP are part of a family of extracellular vesicles, which may be characterized according to size range, phenotype and function. Exosomes (30-100 nm) are derived from endocytic compartments within the cell and apoptotic bodies (up to 4000 nm) are derived from endoplasmic membranes (18). MP can be generated by nearly every cell type during activation, injury or apoptosis (19-22). In circulation, MP are derived from various vascular cell types, including platelets, erythrocytes, leukocytes, and, of particular interest, EC (20, 23). All MP, regardless of their cell of origin, have negatively charged phospholipids, such as phosphatidylserine, in their outer membrane leaflet, accounting for their procoagulant properties (24). MP also participate in homeostasis under physiological conditions. MP carry biologically active surface, cytoplasmic and nucleotides allowing them to activate and alter the functionality of their target cells thereby leading to the exacerbation of normal physiological processes such as coagulation and inflammation (24).

Aggression or activation of the vascular endothelium leads to an increased shedding of endothelial MP (EMP). Although circulating EMP can be found in normal individuals, increased levels have been identified in a variety of pathological situations including thrombosis, atherosclerosis, renal failure, diabetes, systemic lupus erythematosus, MS and CM (21, 25-28). In these conditions, EMP express arrays of cell surface molecules reflecting a state of endothelial dysfunction. These data highlights the link between endothelial damage, EMP release and the modulation of inflammatory and/or immune responses.

Immune modulation by EMP has been described in very few settings. EMP induce plasmacytoid DC (pDC) maturation and inflammatory cytokine production by DC (29) and can influence Th1 cell activation and secretion of cytokines in patients with acute coronary syndrome (30). Of note, MP isolated from Plasmodium infected red blood cells contain Plasmodium antigens and activate macrophages and neutrophils (31, 32), demonstrating that MP from other cellular sources also can modulate the immune response. As endothelial alteration is associated with EMP release and T cell activation in numerous diseases, it provokes the question of whether EMP carry molecules that enable them to bind to T cells that modulate their function. Moreover, given for the potential of a HBEC line to modulate T cell responses (5), we aimed to investigate how EMP could interact with, and support the proliferation T cells.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Statement

Blood samples used in this study are from anonymous donors from the Australian Red Cross Blood Bank. Human ethics protocol was approved by the University of Sydney Human Ethics Committee (Approval #10218). The Animal Ethics Committee of the University of Sydney (K20/6-2011/3/5569 and K00/10-2010/3/5317) approved mouse experiments.

Cells and cell culture

Primary human brain microvascular endothelial cells isolated from normal human brain tissue (HBEC, cAP-0002) were purchased from Angio-proteomie (Boston, MA, USA, Supplementary Fig 4). cAP-0002 HBEC are >95% positive (by immunofluorescence) for cytoplasmic VWF / Factor VIII, cytoplasmic uptake of Di-IAc-LDL and cytoplasmic PECAM1. The HBEC are negative for HIV-1, HBV, HCV, and Mycoplasma. Mouse brain microvascular endothelial cells from C57BL/6 mice (MBEC, C1862) were purchased from Creative Bioarray (NY, USA). HBEC were cultured in supplemented EBM-2 medium (Lonza, Basel, CH, Cat No. CC-3156) and grown on plates pre-coated with rat-tail collagen type I (BD Biosciences, NJ, USA). MBEC were cultured in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 10% FCS (Life Technologies, CA, USA), and grown on plate pre-coated with 0.2% gelatin (SIGMA, MO, USA). THP-1 cells were obtained from ATCC and grown in RPMI with 10% FCS. Cytokine-induced EMP production by HBEC and MBEC was performed by treating the cells with 100 ng/ml TNF and 50 ng/ml IFNγ (Peprotech, London, UK) for 18h.

Antigen uptake analysis

The ability of EMP to carry antigens from mother cells in both resting and cytokine stimulated conditions was assessed using the FITC-Ovalbumin (FITC-OVA) antigen uptake assay (33). Briefly, HBEC were incubated with 1 mg/ml FITC-OVA (Invitrogen, CA, USA) at 37 °C for 45min and washed three times with PBS. Cytokine-induced EMP release by HBEC was then performed by treating the cells with 100 ng/ml TNF and 50 ng/ml IFNγ (Peprotech) for 18h. FITC/CD105-positive EMP were enumerated on the Cytomics FC500 MPL flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, CA, USA), with the number of fluorescent-positive MP counted per 60 seconds. All cytometric analysis in this article was performed using Flowjo software (Tree Star, OR, USA).

Human PBMC preparation

PBMC were separated from leukopacks by conventional Ficoll gradient and frozen in 10% DMSO in FCS and stored in liquid nitrogen. PBMC were then thawed and washed twice in cold medium before use in assays.

Mouse LN cell preparation

Mouse lymph node (LN) cells from the LNs and spleen of both CBA and C57BL/6 mice were isolated by mechanical disruption of the organs and incubated in RBC lysis buffer (0.156 M ammonium chloride, 0.01 M sodium bicarbonate, and 1 mM EDTA) on ice. Cells were washed twice in cold medium before use in assays.

T cell isolation

CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were isolated from freshly thawed PBMC using an Easysep® (Stemcell Technologies, BC, Canada) negative selection kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Purity was assessed by flow cytometric analysis of monoclonal antibodies against CD4 and CD8 (eBioscience, CA, USA) with purity always greater than 95%.

CFSE staining

For labelling isolated T cells and whole PBMCs with Carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE; Invitrogen), cells (at a density of 107 cells/ml) were incubated for 10 min at 37 °C in 5 mM CFSE in FCS free RPMI. Labelling was stopped with FCS and cells were washed 3 times prior to use. For the quantification of cell proliferation, cells were analysed by flow cytometry with a reduction in CFSE MFI indicative of cell division.

EMP purification

HBEC or MBEC culture supernatants were centrifuged for 5 min at 1800 g; large cellular debris were discarded and supernatants were spun for 45 min at 18,000 g. MP pellets were resuspended in cell culture-grade PBS and samples were spun once more for 45 min at 18,000 g in PBS to ensure removal of any remaining soluble cytokine. Final MP pellets were resuspended in RPMI/10% FCS for quantification and use in assays.

Enumeration of EMP by flow cytometry

Purified EMP were enumerated according to positivity for CD105. EMP were diluted in PBS and stained with either anti-human CD105-PE (Beckman Coulter) or anti-mouse CD105-PE (eBioscience) for 30 min at RT. Samples were further diluted with PBS prior to flow cytometric analysis, analyzed on the FC500 flow cytometer and the numbers of C105-positive MP recorded per 60 sec. All analysis parameters were set to log scale, as described previously (34). Light forward scatter (FS) was plotted against the side-angle scatter (SS), and MP were gated in the FS as a population of <1 μm in size using calibrated latex beads. Fluorescence was plotted against SS, with the number of positive fluorescent events representing the number of EMP.

Fluorescent labelling of EMP

Purified EMP were labelled with either PKH26 (red) or PKH67 (green) fluorescent cell linker kit for general cell membrane labelling (Sigma) as previously described (35). The labelled EMP were then washed twice in RPMI/10% FCS (18,000 g for 45 min) and leached overnight at 4 °C. EMP were centrifuged (18,000 g for 45 min) and resuspended in RPMI/10% FCS prior to EMP enumeration using CD105.

Surface phenotype by flow cytometry

For flow cytometric analysis of HBEC, cells were incubated in the presence of fluorochrome-conjugated mAbs against CD105 (SN6), VCAM-1 (STA), B7-1/CD80 (2D10.4), B7-2/CD86 (IT2.2), CD40 (5C3), HLA-DR/MHC II (LN3) and CD275 (MIH12) (all from eBioscience), ICAM-1 (5.6E; Beckman Coulter) and β2-microglobulin/MHC I (TÜ99; BD Biosciences) as per manufacturer’s instructions. Flow cytometric analysis was performed on the FC 500 flow cytometer. For flow multi-colour cytometric analysis of the activation status of donor T cells, cells were incubated with the following antibody cocktail: CD69-FITC (FN50), CD40L-PE (CD154, 24-31) (eBioscience), CD8-Alexa Fluor 700, CD4-Pacific Blue, CD45RA-Alexa Fluor 750, CD3-Krome Orange (Beckman Coulter) and CD62L-APC (Miltenyi Biotec). Cells were washed once prior to flow cytometry using a Gallios™ Flow Cytometer (Beckman Coulter). Naive and memory T-cell populations were distinguished by CD45RA and CD62L expression, as described previously (37). For EMP phenotyping, HBEC supernatant following stimulation was incubated with mAb and diluted 1:1 in PBS prior to flow cytometric analysis on the FC 500 flow cytometer. EMP production per 100,000 HBEC was determined by triplicate supernatant analysis. The supernatant was collected from 400,000 cultured HBEC per well following 18 h stimulation.

Conjugation assays

The ability of EMP to form conjugates with T cells was assessed using an in vitro conjugation assay (5, 36). Briefly, EMP were co-incubated with freshly thawed PBMC (human) or isolated LN cells (mouse) (ratio of 1 PBMC: 3 EMP) for 45 min at 37 °C. Cells were washed once prior to staining at 4° C with fluorochrome-conjugated mAbs against hCD4/mCD4 (eBioscience) and hCD8/mCD8 (Biolegend/eBioscience). Samples were analysed by flow cytometry. Conjugates were deemed to be positive for PKH and either CD4 or CD8. To block binding of EMP to T cells through ICAM-1 and VCAM-1, EMP were incubated with specific blocking antibodies prior to conjugation. αICAM-1 (Clone BBIG-I1, 10 μg/ml, RnD Systems, MN, USA), αVCAM-1 (Clone BBIG-V1, 10 μg/ml, RnD Systems) and isotype control (mouse IgG1) were added to purified EMP for 1 hr at 37 °C. EMP were co-cultured with PBMC for conjugation as outlined above. EMP binding to specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell subtypes was examined by surface staining with the following antibody cocktail after EMP conjugation to PBMC: CD8-Alexa Fluor 700, CD4-Pacific Blue, CD45RA-Alexa Fluor 750, CD3-Krome Orange (Beckman Coulter) and CD62L-APC (Miltenyi Biotec). Cells were washed once prior to flow cytometry using a Gallios™ Flow Cytometer. Naive and memory T-cell populations were distinguished by CD45RA and CD62L expression, as described previously (37). Flow cytometric analysis of the naïve/effector/memory subsets for both CD4+ and CD8+ donor T cells are shown in Supplementary Figure 2.

Confocal microscopic analysis of EMP/T cell conjugates

CFSE-labeled isolated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were co-cultured with PKH26 labeled EMP at a ratio of 1:4 for 45 min at 37 °C. Cell/EMP conjugates were then mounted in PBS and imaged with the Zeiss LSM 510 Meta Confocal microscope at ×63/1.40 oil with 1× and 1.6× optical zoom.

In vitro T cell proliferation assays

5×104 CFSE-labeled PBMCs were added per well with the following conditions; PBMC alone, 1 μg/ml Concanavalin A (ConA; Sigma) or 0.3 μg/ml for anti-CD3 mAb (eBioscience; Clone HIT3a). The agonistic anti–CD3 mAb was added to the assay to mimic T cell receptor (TCR) stimulation (38) and ConA was used as a T cell mitogen (39). Resting or TNF+IFNγ EMP were added to the proliferation assay at a ratio of 3 EMP: 1 PBMC. THP-1, resting HBEC or TNF+IFNγ stimulated HBEC were γ-irradiated (3,000 rads) and added at a ratio of 1 cell:1 PBMC. The co-cultures were incubated for 5 days at 37°C and then stained with PE conjugated anti-human CD4 (eBioscience; Clone OKT4) and PE-Cy5 anti-human CD8a (Biolegend; Clone HIT8a).

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6.0 (GraphPad Software Inc.). The Mann-Whitney test was used to evaluate the statistical significance, p-values of < 0.05 were deemed significant.

Results

EMP express key molecules for antigen presentation and T cell activation

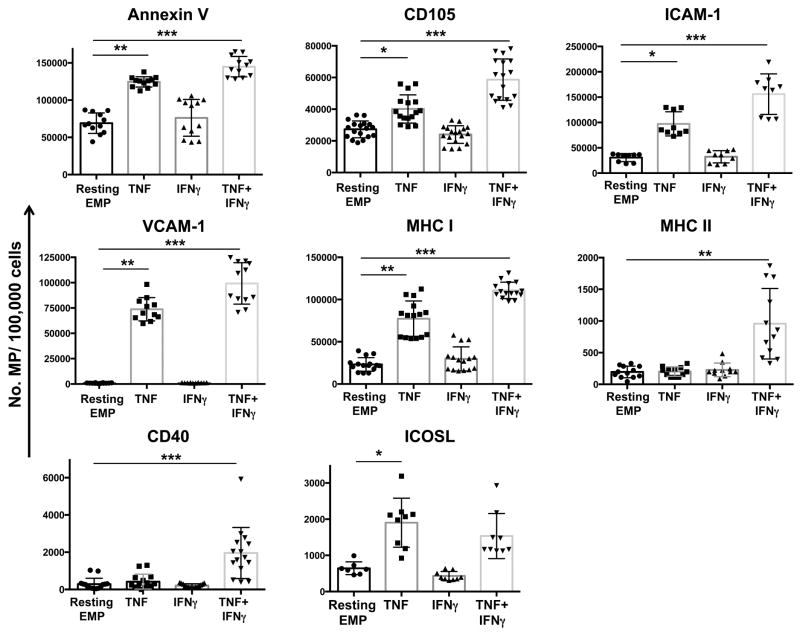

Given that EMP express markers of the parent EC, we sought to examine whether EMP released from our HBEC expressed such markers relevant to antigen presentation and T cell co-stimulation. Numbers of annexin V+- an CD105+ MP, both considered as constitutive markers of MP, were significantly increased following stimulation with TNF and further increased with a TNF+IFNγ dual stimulation (Fig 1). This increase in CD105+ EMP numbers following TNF or TNF+IFNγ occurred without any change in CD105 expression on parent HBEC following the stimulations (Supplementary Fig 1). Resting HBEC released low levels of ICAM-1 positive EMP, compatible with their low basal expression, after TNF or TNF+IFNγ stimulation, a significantly greater number of ICAM-1+ MP was detected following stimulation of HBEC (Fig 1). While VCAM-1 was not detected on EMP released from resting cells, nor on the resting cells themselves (Fig 1, Supplementary Fig 1), significantly higher numbers of VCAM-1+ MP were detected following TNF or TNF+IFNγ stimulation of HBEC (Fig 1). Unlike hCMEC/D3 line where the constitutive expression of MHC I (β2-microglobulin) is unchanged following cytokine stimulation (5), MHC I expression was upregulated by cytokine stimulation in primary cells (Supplementary Fig 1). In the case of the EMP, MHC I+ MP were released by resting HBEC, and their numbers increased following stimulation of the HBEC with either TNF or TNF+IFNγ (Fig 1). Most interestingly, both MHC II+ and CD40+ MP were detected following TNF+IFNγ stimulation (Fig 1), while ICOSL+ MP were detected in both TNF and TNF+IFNγ stimulation conditions (Fig 1). This EMP phenotype mirrors that seen on parent cells (Supplementary Fig 1). The primary cells used in this assays did not express other co-stimulatory molecules such as B7-1 and B7-2 (Supplementary Fig 1).

FIGURE 1. Expression of markers relevant to antigen presentation and T cell activation on EMP.

Graphs represent flow cytometry results of EMP quantification from unstimulated and cytokine stimulated HBEC cells 18 h following stimulation. HBEC were stimulated with either 100ng/ml TNF (TNF), 50ng/ml IFNγ (IFNγ), or 100ng/ml TNF + 50ng/ml IFNγ (TNF+IFNγ) and compared to EMP from unstimulated cells (Resting EMP). EMP were stained with Annexin V or mAbs against Endoglin (CD105), ICAM-1, VCAM-1, MHC I (β2-microglobulin), MHC II (HLA-DR), CD40 and ICOSL (CD275). Data is represented as number of positive MP for each respective cell surface antigen per 100,000 cells. Data is pooled from four independent experiments. Data are expressed as means ± SD. *P <0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

EMP carry foreign antigens from the parent cell following vesiculation

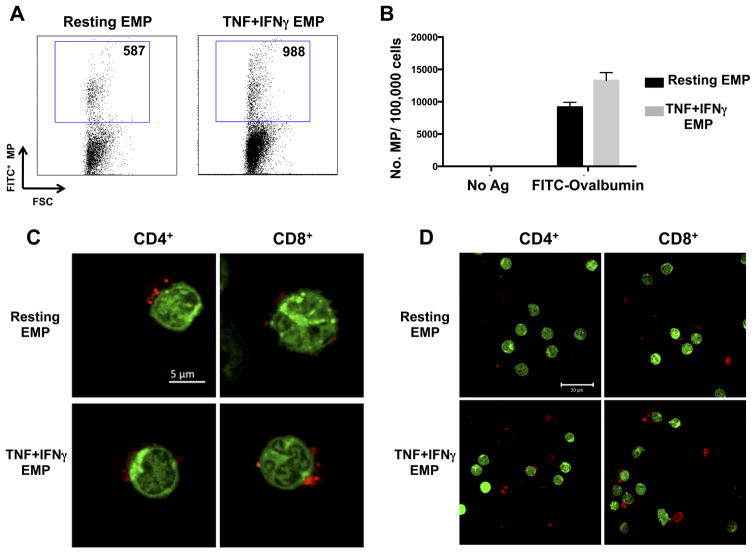

As antigen presentation to T cells is a fundamental step in an adaptive immune response, here we examined whether EMP carried antigens from their mother cell following vesiculation using the FITC-Ovalbumin (FITC-OVA) antigen uptake assay. Ovalbumin is widely used as a model antigen for the characterization of antigen uptake and processing in APCs. Following antigen uptake with FITC-OVA, resting HBEC produced detectable levels of FITC-positive EMP (Fig 2A) indicating transfer of the antigen to the MP following vesiculation. Moreover, when HBEC were stimulated with TNF+IFNγ following antigen uptake, increased numbers of FITC-positive EMP were detected (Fig 2A,B).

FIGURE 2. EMP transfer fluorescently labelled antigen following vesiculation and bind to T cells.

(A) Flow cytometry dot-plots depicting the number of FITC+ EMP following antigen uptake of FITC-OVA by HBEC mother cells. HBEC were either left unstimulated following antigen uptake (Resting EMP) or stimulated with 100ng/ml TNF + 50ng/ml IFNγ (TNF+IFNγ EMP) 18 h prior to EMP quantitation by flow cytometry. (B) Graph represents flow cytometry results of number of FITC+ EMP/100,000 cells from unstimulated and cytokine stimulated HBEC cells 18 h following stimulation. Data are representative of three independent experiments with mean ± SD shown. (C, D) Single plane confocal microscopy images of purified CFSE-labelled CD4+ and CD8+ T cells with bound PKH26 (red) EMP. Conditions are as follows: Resting EMP: EMP isolated from resting HBEC; TNF+IFNγ EMP: EMP isolated from HBEC stimulated with 100ng/ml TNF + 50ng/ml IFNγ 18 h prior. Binding performed at a ratio of 3 EMP: 1 T cell. Magnification: 63x/1.40 oil with 1.6x optical zoom (C) and 63x/1.40 oil (D). Scale bars are labelled in micrometres.

EMP bind to and form conjugates with CD4+ and CD8+ T cells

Given the expression of a number of surface molecules on EMP that have corresponding ligands/receptors on T cells, we next sought to examine these interactions in vitro. EMP isolated from both resting and cytokine (TNF+IFNγ) stimulated HBEC were fluorescently labelled with PKH26 (red) and co-cultured with green fluorescently labeled (CFSE) CD4+ and CD8+ T cells prior to confocal microscopic analysis. Of note, flow cytometric analysis of the T cell activation markers CD69 and CD40L on both CD4+ and CD8+ donor T cells indicated that the donor T cells were not activated (Supplementary Figure 2). EMP purified from both resting and cytokine stimulated HBEC bound readily to both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Fig 2C). Interestingly, more than one EMP was found bound per T cell (Fig 2C), however, not every T cell imaged had EMP bound (Fig 2D).

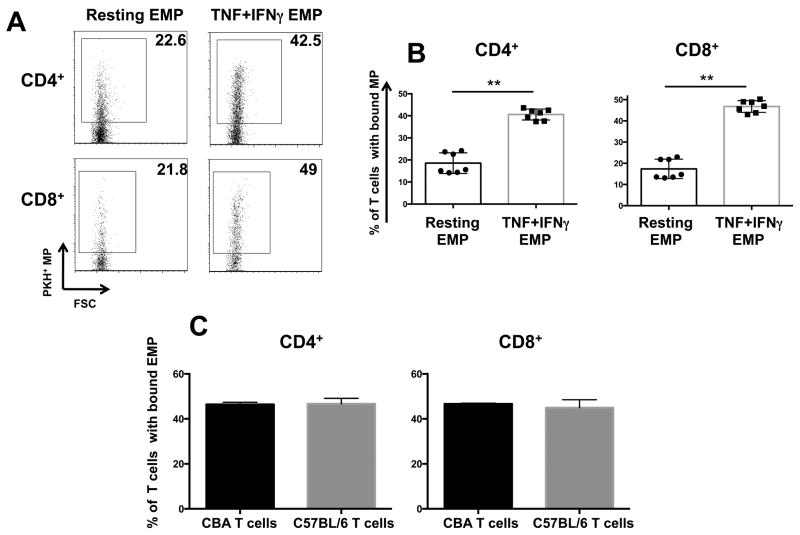

As optimal T-cell activation and differentiation in vivo requires long-lasting T–APC interaction, a classical in vitro conjugate forming assay was adapted to assess the ability of EMP to form conjugate-like interactions with T cells. CD4+ or CD8+ T cells purified from PBMC were incubated in suspension with red fluorescently labeled (PKH26) EMP and the adherence between EMP and T cells was examined using cell specific staining and flow cytometry. Conjugates were defined as cells positive for both PKH26 and the subset specific mAb for CD4 or CD8. EMP from both resting and TNF+IFNγ stimulated HBEC formed conjugates with CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Fig 3A). There were significantly higher percentages of T cell/EMP conjugates when EMP were purified from TNF+IFNγ stimulated than from resting cells (Fig 3B). In the case of resting EMP, 18.5% of CD4+ and 17.4% CD8+ T cells had EMP bound. When T cells were co-cultured with EMP from TNF+IFNγ stimulated HBEC, the increase in conjugation lead to 40.6% of CD4+ and 46.8% CD8+ T cells with EMP bound.

FIGURE 3. EMP form conjugates with CD4+ and CD8+ T cells.

(A) Representative flow cytometry plots indicating the levels of conjugation between EMP and CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Numbers shown are the percentage of CD4+ and CD8+ cells (respectively) with EMP conjugated. EMP were labeled with PKH67 and PBMC labeled with CD4/CD8 mAbs after 45 min of conjugation. Conjugation was performed at a ratio of 3 EMP: 1 PBMC. Conditions are as follows: Resting EMP: EMP isolated from resting HBEC; TNF+IFNγ EMP: EMP isolated from HBEC stimulated with 100ng/ml TNF + 50ng/ml IFNγ 18 h prior. (B) Graphs represent flow cytometry results of EMP conjugation to T cells. Data is represented as percentage CD4+ or CD8+ T cells with bound EMP. Data are pooled from three independent experiments. Data are expressed as means ± SD. **P < 0.01. (C) Conjugation assay graphs representing the conjugation of EMP isolated from resting MBEC and conjugated to allogeneic (C57BL/6) and syngeneic (CBA) T cells. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments, n = 4 per experiment. Data are expressed as means ± SD.

Role of MHC mismatch in EMP/T cell binding

In the human system, syngeneic EMP/T cells are not available, therefore, as the donor of HBEC is different to that of PBMC, potential allogeneic differences may result in the EMP/T cell binding and conjugation observed. To ensure this was not the case, EMP purified from MBEC were put into a conjugation assay with donor T cells from two different mouse strains. The C1862 MBEC line used was isolated from C57BL/6 (H-2b). EMP from C1862 cells were purified and conjugated to LN cells from two different donor strains; C57BL/6 (H-2b; syngeneic) and CBA/J (H-2k; allogeneic). Mouse EMP conjugated at equivalent levels to both syngeneic and allogeneic T cells (Fig 3C) suggesting the binding of human EMP to donor T cells was not due to any MHC mismatch between the EMP and T cells.

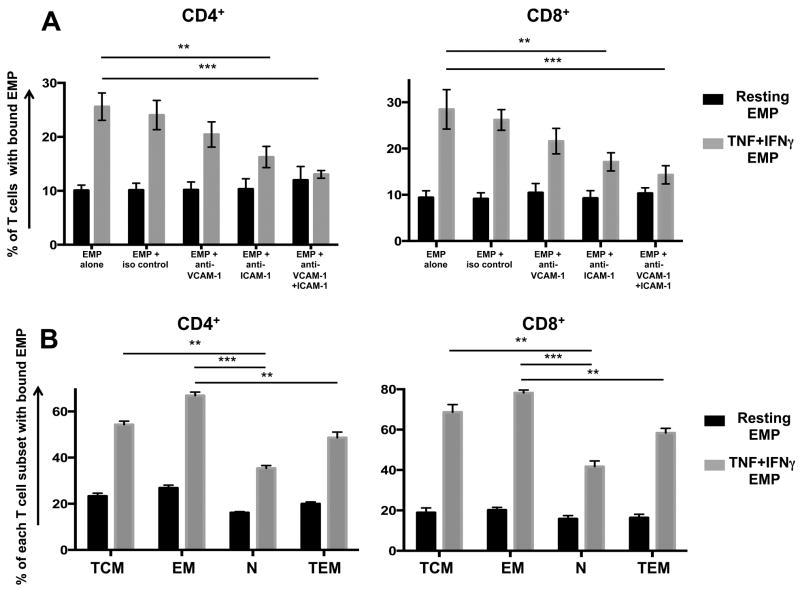

Identification of receptors involved in EMP/T cell binding

As EMP purified from HBEC (Fig 1B) and other sources (23, 40) express ICAM-1 and VCAM-1, we sought to determine whether these molecules play a role in EMP binding to T cells. Blocking either VCAM-1, ICAM-1 or both on EMP isolated from resting HBEC prior to conjugation to PBMC had no effect on their binding to CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Fig 4A). Similarly, blocking VCAM-1 on EMP isolated from TNF+IFNγ-stimulated cells did not change the level of EMP binding to either T cell subset (Fig 4A). However, blocking ICAM-1 on TNF+IFNγ EMP resulted in significantly decreased conjugation to both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Fig 4A). Moreover, blocking both VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 on TNF+IFNγ EMP resulted in an even greater reduction in conjugation to both T cell subsets, with the level of binding almost equivalent to that seen with resting EMP (Fig 4A).

FIGURE 4. EMP bind preferentially to memory T cells and TNF+IFNγ EMP bind to T cells in an ICAM-1/VCAM-1 dependent manner.

(A) Percentage of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells with conjugated EMP following blocking of VCAM-1 and/or ICAM-1 on EMP. PKH67-labelled EMP were treated with either αVCAM-1, αICAM-1, αVCAM-I/ICAM-1 or mouse IgG1 isotype control for 1 hour prior to conjugation assay with PBMC. Following conjugation, PBMC were labeled with CD4/CD8 mAbs and analysed by flow cytometry. Conjugation was performed at a ratio of 3 EMP: 1 PBMC. Conditions are as follows: Resting EMP: EMP isolated from resting HBEC (black bars); TNF+IFNγ EMP: EMP isolated from HBEC stimulated with 100ng/ml TNF + 50ng/ml IFNγ (grey bars). Data is pooled from three independent experiments, each with n=3-4 per experiment. Data are expressed as means ± SD. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 as determined using one way ANOVA. (B) Graphical representation of the percentage of specific CD4+ and CD8+ subsets with bound EMP. Numbers shown are the percentage of specific CD4+ and CD8+ cells with EMP conjugated. EMP were labeled with PKH67 and PBMC labeled with CD4/CD8/CD3/CD62L/CD45RA mAbs after 45 min of conjugation. Conjugation was performed at a ratio of 3 EMP: 1 PBMC. Conditions are as follows: Resting EMP: EMP isolated from resting HBEC (black bars); TNF+IFNγ EMP: EMP isolated from HBEC stimulated with 100ng/ml TNF + 50ng/ml IFNγ (grey bars). T cell subsets are defined as follows: naïve (N; CD45RA+, CD62L+), central memory (TCM; CD45RA−, CD62L+), effector memory (EM; CD45RA−, CD62L−) and terminal effector memory (TEM; CD45RA+, CD62L−) cells. Data is pooled from two independent experiments, each with n=4. Data are expressed as means ± SD. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 as determined by one way ANOVA.

EMP bind preferentially to memory T cells

To further examine which specific populations of T cells EMP bind to, six-colour flow cytometric analysis was conducted using the following gates on both CD4 and CD8 subsets: naïve (N; CD45RA+, CD62L+), central memory (TCM; CD45RA−, CD62L+), effector memory (EM;. CD45RA−, CD62L−) and terminal effector memory (TEM; CD45RA+, CD62L−) cells. For both CD4+ and CD8+ subsets, there was significantly more EMP binding to effector memory subsets than the naïve and terminally differentiated effector memory subsets (Fig 4B). Additionally, there were significantly more EMP bound to central memory than naïve T cells.

EMP promote the proliferation of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells

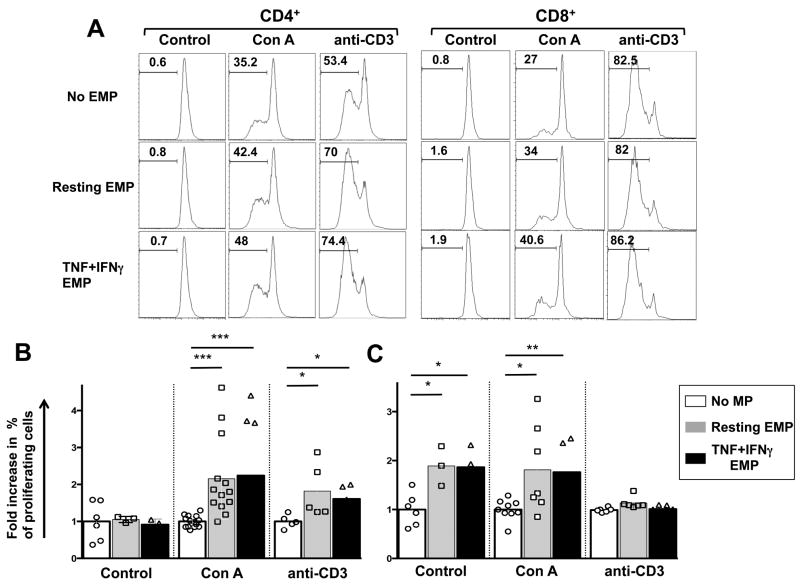

Because HBEC support and promote the proliferation of T cells (5) and since EMP were capable of binding to and forming conjugates with both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, the ability of HBEC to support T cell proliferation was assessed by co-culturing CFSE-labelled donor PBMCs with EMP isolated from either resting or TNF+IFNγ stimulated HBEC. Five days following co-culture, the percentage of proliferating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells was determined by measuring the reduction in CFSE MFI. In the case of CD4+ T cells, EMP had no effect in resting conditions (Fig 5A,B). However, in the presence of TCR or T cell mitogenic stimulation, both EMP from resting cells and TNF+IFNγ MP increased the percentage of proliferating cells (Fig 5A,B) when compared to stimuli alone. Interestingly, there was no significant difference between EMP from resting and cytokine-stimulated HBEC in the ability to promote CD4+ T cell proliferation. Of note, both resting EMP and TNF+IFNγ EMP significantly increased the percentage of proliferating CD8+ cells in the absence of any mitogen or TCR activation (Fig 5A,B). Similarly, when CD8+ T cells were stimulated with ConA and co-cultured with EMP from both resting and TNF+IFNγ stimulated HBEC, a significant increase in the percentage of proliferating cells was observed (Fig 5A,B). Like for CD4+, there was no significant difference between EMP from both resting and TNF+IFNγ stimulated HBEC in the ability to promote resting CD8+ T cell proliferation. Additionally, EMP had no effect on CD8+ proliferation when T cells were stimulated with anti-CD3 mAb (Fig 5A,B). Interestingly, both resting and TNF+IFNγ EMP did not increase the proliferation of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells to the same level as that seen by the parent HBEC or by professional APC such as THP-1 cells (Supplementary Fig 3).

FIGURE 5. EMP support the proliferation of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells.

(A), CFSE histogram plots of gated CD4+ (left panel) and CD8+ (right panel) 5 days following the start of the co-culture of HBEC and donor PBMC. For co-culture 5×104 CFSE-labelled donor PBMC were co-cultured or not EMP purified from either resting MP or 100 ng/ml TNF + 50 ng/ml IFNγ pre-stimulated (TNF+IFNγ EMP) HBEC cells. PBMC were either subjected to resting conditions or stimulation with for anti-CD3 mAb or ConA. Following 5 days of culture, cells were harvested and stained with CD4 and CD8 mAbs and analysed by flow cytometry to identify proliferating cell populations. CFSE histograms depict the number of events (y-axis) and the fluorescence intensity (x-axis) with proliferating cells displaying a progressive 2-fold loss in fluorescence intensity following cell division, indicative of proliferating cells. Histograms are representative of four independent experiments with the same donor. (B) Graphical representation of the fold increase over control (No MP) in proliferating CD4+ and CD8+ PBMC following 5 days of culture either alone (white bars) or in the presence of Resting EMP (grey bars) or TNF+IFNγ EMP cytokine stimulated (black bars) as outlined above. Data is pooled from four independent experiments with the same donor. *P <0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 indicates statistically significant differences between control PBMC and respective co-culture conditions using a nonparametric Mann-Whitney test (p< 0.05).

Discussion

Here, we provide for the first time evidence that MP isolated from human brain MVEC possess the minimal machinery required to present antigens, interact with and support the activation of T cells.

Our analysis of MHC and co-stimulatory molecule expression on EMP shows for the first time that EMP are endowed with a co-stimulatory ligand of the B7 family and TNF-receptor superfamily, ICOSL and CD40, respectively. This, in conjugation with their expression of MHC II supports the notion of brain EMP being able to present antigens to and co-stimulate T cells promoting effector CD4+ and T cell responses. Additionally, with high numbers of MHC I+ EMP produced by HBEC, EMP possess the minimal requirement for antigen presentation to CD8+ T cells. Combined, these findings demonstrate expression of molecules relevant to antigen presentation on EMP and indicate that EMP have the capacity to interact with and modulate target T cells.

Previously, expression of MHC molecules on MP has been restricted to professional APCs. MP released from mature DCs may modulate local or distant adaptive immunologic responses by transferring MHC molecules to resting DCs, thereby allowing them to present alloantigens to T cells (41). Likewise, MP from bovine B cells confer antigen-presentation capabilities to bovine polymorphonuclear leukocytes by shuttling MHC class II molecules (42). Finally, MPs from both M. tuberculosis infected and uninfected macrophages express MHC II and CD40 (43). The data presented here provide for the first time evidence for endothelial alteration being able to modulate distal antigen recognition and co-stimulation in times of inflammation or infection through expression of MHC and co-stimulatory molecules.

Antigen uptake is the first step in antigen-presenting pathways, leading to the initiation of an adaptive immune response. EC have been previously shown to take up antigen using macropinocytosis, clathrin-coated pits (5) and the mannose receptor (44). Here we show that EMP are able to transfer the soluble fluorescent antigen, FITC-OVA following vesiculation, providing further evidence to support the immunogenic capacity of EMP, particularly to distal target cells. These data indicates that EMP, following antigen uptake by their mother cell HBEC have the capacity to carry antigen, participating thereby in a fundamental initial step in the primary immune response.

Despite evidence for EMP modulation of Th1 cell function (30), there is no published data showing EMP interacting directly with T cells. Here, using confocal microscopy and flow cytometry we are able to demonstrate binding between EMP and both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Interestingly, EMP produced by HBEC following TNF+ IFNγ stimulation bound more readily to T cells, with twice as many T cells binding these EMP compared to those from resting cells. Using mouse EMP in co-culture with syngeneic and allogeneic donor T cells, we were able to show equivalent conjugation to T cells demonstrating that the binding, in the human EMP system, is not due to any allogeneic differences between HBEC and PBMC donors.

Using blocking antibodies against the endothelial adhesion molecules VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 enabled us to define the specific interactions involved in the increased binding of EMP from cytokine stimulated cells to T cells. Both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells displayed increased binding of TNF+IFNγ EMP that was mediated predominantly through ICAM-1, thus indicating that EMP isolated from TNF+IFNγ HBEC bind to LFA-1 and Mac-1 expressed on target T cells (12). The addition of both blocking antibodies brought the binding of TNF+IFNγ EMP back to levels equivalent to those of resting EMP suggesting that the increased binding is only partially mediated though the VCAM-1 ligands, VLA-4 and α4β7 expressed on target T cells (12, 13). Given the high number of TNF+IFNγ EMP that express ICAM-1, it is not unsurprising that this is the adhesion molecule mediated binding in these conditions. Blocking ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 on the EMP had no effect on the binding of resting EMP to T cells, indicating that this binding occurs through other receptor/ligand pairs or phosphatidylserine at the surface of MP (46). Interestingly, binding experiments with EMP and pDC have been shown to be dependent on temperature, sodium-proton exchanges and an intact actin cytoskeleton (29). Moreover, in this study EMP bound to CD4+ T cells at both 37 °C and 4 °C (29), however the ratio of EMP: T cell used was 100:1, substantially higher than the 3:1 ratio used in our study. Finally, further flow cytometric analysis showed that EMP from cytokine stimulated cells have a greater propensity for binding to effector memory T cells over any other subset, with the least binding observed to naïve CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. These differences may in part be due to increased expression of LFA-1 and VLA-4 on memory T cells vs naïve cells (47, 48). Physiologically, EMP binding preferentially to memory and effector T cells, particularly during inflammatory situations, such as that mimicked here with TNF+IFNγ would lead to an exacerbated effector response to infection.

In the co-culture assays presented here, EMP were able to support and promote the proliferation of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Non-stimulated CD4+ cells, were unresponsive to both resting and TNF+IFNγ EMP. However, when the CD4+ T cells were stimulated via their TCR (anti-CD3 mAb) or with ConA, a significant increase in proliferation was observed in the presence of both resting and TNF+IFNγ EMP with interestingly, no difference in the proliferation induced by the 2 types of EMP. This may be due to the threshold of activation and proliferation being at a maximal level with no increase thus able to be observed in the presence of TNF+IFNγ EMP. Conversely, when non-stimulated CD8+ T cells were co-cultured with EMP, a significant increase in their proliferation was observed over no MP control, with this effect possibly due to differences in MHC between PBMC donor and HBEC donor. Similar increases in proliferation were observed for ConA stimulation, but not for anti-CD3 mAb and this may be due to the fact that a large majority of the CD8+ T cells alone were proliferating 5 days after co-culture in response to for anti-CD3. Combined, the data in these experiments indicate that EMP regardless of source (resting or cytokine activated) are able to support and promote the proliferation of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Given that elevated numbers of circulating EMP are often associated with disease severity in a number of T cell dependent immunoinflammatory diseases such as MS and CM (26, 49), these findings provide a novel mechanism for pathogenesis and pathology in such diseases.

The demonstration of antigen-specific activation of human T cells by EMP is hampered by the requirement for MHC-matched HBEC and T cells. Some studies using MHC matched donors support the model that cultured human EC are able to present antigen to activated CD4+ T cells (50-52). However data indicate that mouse T cell clones or T cells from TCR-transgenic mice can be stimulated to proliferate in a peptide-antigen-specific manner by co-culture with MHC-matched EC and the relevant protein antigen (53, 54), providing evidence for antigen-specific activation by EC. Finally, the in vivo relevance of our observations remains to be explored further.

In summary, we have shown that MP isolated from human brain microvascular endothelium express molecules important for T cell stimulation and activation including CD40, ICOSL and MHC II. Additionally, they transfer soluble antigen following vesiculation and bind readily to T cells using both ICAM-1 dependent and independent mechanisms. Moreover, EMP promote the proliferation of T cells in vitro. The data presented here supports the hypothesis that EMP are immunomodulatory, and show, for the first time, direct interactions between EMP and target T cells. These data add to the evidence for EMP as effectors, as they have previously been shown to be involved in inflammatory processes, blood coagulation and regulation of vascular function (55). The findings presented here offer a novel mechanism for the role of EMP in neuroimmunological complications and are pertinent to our understanding of vascular dysfunction in immune and inflammatory responses.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NHMRC project grant APP1028241, APP571014, NHMRC training fellowship APP571397 (JW), NIH grant (NIH RO1NS0789873-1) and the Rebecca L. Cooper Medical Research Foundation.

References

- 1.Banchereau J, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature. 1998;392:245–252. doi: 10.1038/32588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Male DK, Pryce G, Hughes CC. Antigen presentation in brain: MHC induction on brain endothelium and astrocytes compared. Immunology. 1987;60:453–459. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klingenberg R, Autschbach F, Gleissner C, Giese T, Wambsganss N, Sommer N, Richter G, Katus HA, Dengler TJ. Endothelial inducible costimulator ligand expression is increased during human cardiac allograft rejection and regulates endothelial cell-dependent allo-activation of CD8+ T cells in vitro. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:1712–1721. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lichtman A. Endothelial antigen presentation. In: WC A, editor. Endothelial Biomedicine. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2007. pp. 1098–1107. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wheway J, Obeid S, Couraud PO, Combes V, Grau GE. The brain microvascular endothelium supports T cell proliferation and has potential for alloantigen presentation. PLoS One. 2013;8:e52586. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Verma S, Nakaoke R, Dohgu S, Banks WA. Release of cytokines by brain endothelial cells: A polarized response to lipopolysaccharide. Brain Behav Immun. 2006;20:449–455. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grau GE, Behr C. T cells and malaria: is Th1 cell activation a prerequisite for pathology? Research in immunology. 1994;145:441–454. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2494(94)80175-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Monso-Hinard C, Lou JN, Behr C, Juillard P, Grau GE. Expression of major histocompatibility complex antigens on mouse brain microvascular endothelial cells in relation to susceptibility to cerebral malaria. Immunology. 1997;92:53–59. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1997.00297.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alexander JS, Zivadinov R, Maghzi AH, Ganta VC, Harris MK, Minagar A. Multiple sclerosis and cerebral endothelial dysfunction: Mechanisms. Pathophysiology : the official journal of the International Society for Pathophysiology / ISP. 2011;18:3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.pathophys.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jambou R, Combes V, Jambou MJ, Weksler BB, Couraud PO, Grau GE. Plasmodium falciparum adhesion on human brain microvascular endothelial cells involves transmigration-like cup formation and induces opening of intercellular junctions. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001021. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bevilacqua MP. Endothelial-leukocyte adhesion molecules. Annu Rev Immunol. 1993;11:767–804. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.11.040193.004003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Springer TA. Traffic signals for lymphocyte recirculation and leukocyte emigration: the multistep paradigm. Cell. 1994;76:301–314. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90337-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berlin C, Berg EL, Briskin MJ, Andrew DP, Kilshaw PJ, Holzmann B, Weissman IL, Hamann A, Butcher EC. Alpha 4 beta 7 integrin mediates lymphocyte binding to the mucosal vascular addressin MAdCAM-1. Cell. 1993;74:185–195. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90305-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pober JS, Gimbrone MA., Jr Expression of Ia-like antigens by human vascular endothelial cells is inducible in vitro: demonstration by monoclonal antibody binding and immunoprecipitation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982;79:6641–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.21.6641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Omari KM, Dorovini-Zis K. CD40 expressed by human brain endothelial cells regulates CD4+ T cell adhesion to endothelium. J Neuroimmunol. 2003;134:166–178. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(02)00423-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khayyamian S, Hutloff A, Buchner K, Grafe M, Henn V, Kroczek RA, Mages HW. ICOS-ligand, expressed on human endothelial cells, costimulates Th1 and Th2 cytokine secretion by memory CD4+ T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:6198–6203. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092576699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Curtis AM, Edelberg J, Jonas R, Rogers WT, Moore JS, Syed W, Mohler ER., 3rd Endothelial microparticles: Sophisticated vesicles modulating vascular function. Vasc Med. 2013;18:204–214. doi: 10.1177/1358863X13499773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boulanger CM, Amabile N, Tedgui A. Circulating microparticles: a potential prognostic marker for atherosclerotic vascular disease. Hypertension. 2006;48:180–186. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000231507.00962.b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ardoin SP, Shanahan JC, Pisetsky DS. The role of microparticles in inflammation and thrombosis. Scand J Immunol. 2007;66:159–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2007.01984.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Piccin A, Murphy WG, Smith OP. Circulating microparticles: pathophysiology and clinical implications. Blood reviews. 2007;21:157–171. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Combes V, El-Assaad F, Faille D, Jambou R, Hunt NH, Grau GE. Microvesiculation and cell interactions at the brain-endothelial interface in cerebral malaria pathogenesis. Progress in neurobiology. 2010;91:140–151. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2010.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Latham SL, Chaponnier C, Dugina V, Couraud PO, Grau GE, Combes V. Cooperation between beta- and gamma-cytoplasmic actins in the mechanical regulation of endothelial microparticle formation. FASEB J. 2013;27:672–683. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-216531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Combes V, Simon AC, Grau GE, Arnoux D, Camoin L, Sabatier F, Mutin M, Sanmarco M, Sampol J, Dignat-George F. In vitro generation of endothelial microparticles and possible prothrombotic activity in patients with lupus anticoagulant. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:93–102. doi: 10.1172/JCI4985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hugel B, Martinez MC, Kunzelmann C, Freyssinet JM. Membrane microparticles: two sides of the coin. Physiology (Bethesda) 2005;20:22–27. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00029.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.VanWijk MJ, VanBavel E, Sturk A, Nieuwland R. Microparticles in cardiovascular diseases. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;59:277–287. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(03)00367-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Combes V, Taylor TE, Juhan-Vague I, Mege JL, Mwenechanya J, Tembo M, Grau GE, Molyneux ME. Circulating endothelial microparticles in malawian children with severe falciparum malaria complicated with coma. JAMA. 2004;291:2542–2544. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.21.2542-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jimenez J, Jy W, Mauro LM, Horstman LL, Ahn ER, Ahn YS, Minagar A. Elevated endothelial microparticle-monocyte complexes induced by multiple sclerosis plasma and the inhibitory effects of interferon-beta 1b on release of endothelial microparticles, formation and transendothelial migration of monocyte-endothelial microparticle complexes. Mult Scler. 2005;11:310–315. doi: 10.1191/1352458505ms1184oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burger D, Schock S, Thompson CS, Montezano AC, Hakim AM, Touyz RM. Microparticles: biomarkers and beyond. Clin Sci (Lond) 2013;124:423–441. doi: 10.1042/CS20120309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Angelot F, Seilles E, Biichle S, Berda Y, Gaugler B, Plumas J, Chaperot L, Dignat-George F, Tiberghien P, Saas P, Garnache-Ottou F. Endothelial cell-derived microparticles induce plasmacytoid dendritic cell maturation: potential implications in inflammatory diseases. Haematologica. 2009;94:1502–1512. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.010934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu Y, Li L, Yan H, Su Q, Huang J, Fu C. Endothelial microparticles exert differential effects on functions of Th1 in patients with acute coronary syndrome. International journal of cardiology. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Couper KN, Barnes T, Hafalla JC, Combes V, Ryffel B, Secher T, Grau GE, Riley EM, de Souza JB. Parasite-derived plasma microparticles contribute significantly to malaria infection-induced inflammation through potent macrophage stimulation. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000744. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mantel PY, Hoang AN, Goldowitz I, Potashnikova D, Hamza B, Vorobjev I, Ghiran I, Toner M, Irimia D, Ivanov AR, Barteneva N, Marti M. Malaria-infected erythrocyte-derived microvesicles mediate cellular communication within the parasite population and with the host immune system. Cell host & microbe. 2013;13:521–534. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Werling D, Hope JC, Chaplin P, Collins RA, Taylor G, Howard CJ. Involvement of caveolae in the uptake of respiratory syncytial virus antigen by dendritic cells. J Leukoc Biol. 1999;66:50–58. doi: 10.1002/jlb.66.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pankoui Mfonkeu JB, Gouado I, Fotso Kuate H, Zambou O, Amvam Zollo PH, Grau GE, Combes V. Elevated cell-specific microparticles are a biological marker for cerebral dysfunctions in human severe malaria. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13415. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Faille D, Combes V, Mitchell AJ, Fontaine A, Juhan-Vague I, Alessi MC, Chimini G, Fusai T, Grau GE. Platelet microparticles: a new player in malaria parasite cytoadherence to human brain endothelium. FASEB J. 2009;23:3449–3458. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-135822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hauss P, Selz F, Cavazzana-Calvo M, Fischer A. Characteristics of antigen-independent and antigen-dependent interaction of dendritic cells with CD4+ T cells. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:2285–2294. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maldonado A, Mueller YM, Thomas P, Bojczuk P, O’Connors C, Katsikis PD. Decreased effector memory CD45RA+ CD62L- CD8+ T cells and increased central memory CD45RA- CD62L+ CD8+ T cells in peripheral blood of rheumatoid arthritis patients. Arthritis research & therapy. 2003;5:R91–96. doi: 10.1186/ar619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Trickett A, Kwan YL. T cell stimulation and expansion using anti-CD3/CD28 beads. J Immunol Methods. 2003;275:251–255. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(03)00010-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dwyer JM, Johnson C. The use of concanavalin A to study the immunoregulation of human T cells. Clin Exp Immunol. 1981;46:237–249. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jimenez JJ, Jy W, Mauro LM, Soderland C, Horstman LL, Ahn YS. Endothelial cells release phenotypically and quantitatively distinct microparticles in activation and apoptosis. Thrombosis research. 2003;109:175–180. doi: 10.1016/s0049-3848(03)00064-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Obregon C, Rothen-Rutishauser B, Gitahi SK, Gehr P, Nicod LP. Exovesicles from human activated dendritic cells fuse with resting dendritic cells, allowing them to present alloantigens. Am J Pathol. 2006;169:2127–2136. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.060453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Whale TA, Beskorwayne TK, Babiuk LA, Griebel PJ. Bovine polymorphonuclear cells passively acquire membrane lipids and integral membrane proteins from apoptotic and necrotic cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;79:1226–1233. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0505282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Walters SB, Kieckbusch J, Nagalingam G, Swain A, Latham SL, Grau GE, Britton WJ, Combes V, Saunders BM. Microparticles from mycobacteria-infected macrophages promote inflammation and cellular migration. J Immunol. 2013;190:669–677. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Knolle PA, Uhrig A, Hegenbarth S, Loser E, Schmitt E, Gerken G, Lohse AW. IL-10 down-regulates T cell activation by antigenpresenting liver sinusoidal endothelial cells through decreased antigen uptake via the mannose receptor and lowered surface expression of accessory molecules. Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;114:427–433. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00713.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dong C, Juedes AE, Temann UA, Shresta S, Allison JP, Ruddle NH, Flavell RA. ICOS co-stimulatory receptor is essential for T-cell activation and function. Nature. 2001;409:97–101. doi: 10.1038/35051100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Al-Nedawi K, Meehan B, Kerbel RS, Allison AC, Rak J. Endothelial expression of autocrine VEGF upon the uptake of tumor-derived microvesicles containing oncogenic EGFR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:3794–3799. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804543106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sanders ME, Makgoba MW, Sharrow SO, Stephany D, Springer TA, Young HA, Shaw S. Human memory T lymphocytes express increased levels of three cell adhesion molecules (LFA-3, CD2, and LFA-1) and three other molecules (UCHL1, CDw29, and Pgp-1) and have enhanced IFN-gamma production. J Immunol. 1988;140:1401–1407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mackay CR. T-cell memory: the connection between function, phenotype and migration pathways. Immunology today. 1991;12:189–192. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(91)90051-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Minagar A, Jy W, Jimenez JJ, Sheremata WA, Mauro LM, Mao WW, Horstman LL, Ahn YS. Elevated plasma endothelial microparticles in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2001;56:1319–1324. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.10.1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hirschberg H. Presentation of viral antigens by human vascular endothelial cells in vitro. Hum Immunol. 1981;2:235–246. doi: 10.1016/0198-8859(81)90015-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hirschberg H, Hirschberg T, Jaffe E, Thornsby E. Antigenpresenting properties of human vascular endothelial cells: inhibition by anti- HLA-DR antisera. Scand J Immunol. 1981;14:545–553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Burger DR, Ford D, Vetto RM, Hamblin A, Goldstein A, Hubbard M, Dumonde DC. Endothelial cell presentation of antigen to human T cells. Hum Immunol. 1981;3:209–230. doi: 10.1016/0198-8859(81)90019-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Perez VL, Henault L, Lichtman AH. Endothelial antigen presentation: stimulation of previously activated but not naive TCR-transgenic mouse T cells. Cell Immunol. 1998;189:31–40. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1998.1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rodig N, Ryan T, Allen JA, Pang H, Grabie N, Chernova T, Greenfield EA, Liang SC, Sharpe AH, Lichtman AH, Freeman GJ. Endothelial expression of PD-L1 and PD-L2 down-regulates CD8+ T cell activation and cytolysis. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:3117–3126. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Puddu P, Puddu GM, Cravero E, Muscari S, Muscari A. The involvement of circulating microparticles in inflammation, coagulation and cardiovascular diseases. The Canadian journal of cardiology. 2010;26:140–145. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(10)70371-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.