Abstract

Ractopamine (RAC) is fed to an estimated 80% of all beef, swine, and turkey raised in the United States. It promotes muscle mass development, limits fat deposition, and reduces feed consumption. However, it has several undesirable behavioral side effects in livestock, especially pigs, including restlessness, agitation, excessive oral-facial movements, and aggressive behavior. Numerous in vitro and in vivo studies suggest RAC’s physiological actions begin with its stimulation of β1- and β2-adrenergic receptor–mediated signaling in skeletal muscle and adipose tissue; however, the molecular pharmacology of RAC’s psychoactive effects is poorly understood. Using human cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (hCFTR) chloride channels as a sensor for intracellular cAMP, we found that RAC and p-tyramine (TYR) produced concentration-dependent increases in chloride conductance in oocytes coexpressing hCFTR and mouse trace amine–associated receptor 1 (mTAAR1), which was completely reversed by the trace amine–associated receptor 1 (TAAR1)–selective antagonist EPPTB [N-(3-ethoxyphenyl)-4-pyrrolidin-1-yl-3-trifluoromethylbenzamide]. Oocytes coexpressing hCFTR and the human β2-adrenergic receptor showed no response to RAC or TYR. These studies demonstrate that, contrary to expectations, RAC is not an agonist of the human β2-adrenergic receptor but rather a full agonist for mTAAR1. Since TAAR1-mediated signaling can influence cardiovascular tone and behavior in several animal models, our finding that RAC is a full mTAAR1 agonist supports the idea that this novel mechanism of action influences the physiology and behavior of pigs and other species. These findings should stimulate future studies to characterize the pharmacological, physiological, and behavioral actions of RAC in humans and other species exposed to this drug.

Introduction

In the United States and 21 other countries, ractopamine hydrochloride (RAC; EL737, LY031537), a synthetic, racemic biogenic amine, is approved as a livestock feed additive to promote weight gain, increase muscle mass, limit fat deposition, reduce feed consumption, and lessen waste production (Yen, 1984; Yen et al., 1990, 1991; Gu et al., 1991; Rikard-Bell et al., 2009). The presence of RAC in swine has had an impact on the international trade of farm products, and there are reports of food poisonings from other β-receptor agonists (Wu et al., 2013). Due to human health concerns, the use of RAC as a feed additive is banned in 122 countries, including China, Russia, and members of the European Union. Although the physiologic effects of racemic RAC and its active R/R stereoisomer butopamine (BUT; LY131126) have been studied in several mammalian species, surprisingly only four human studies—involving a total of 20 male volunteers—have been reported (Marchant-Forde et al., 2003; Poletto et al., 2009, 2010a,b). The focus of these studies was on the cardiovascular effects of RAC and BUT. No study examining the pulmonary or psychological effects of RAC or BUT in humans has been published. Although statistically underpowered, the four published human studies continue to guide regulatory policies establishing safe limits of human exposure despite the serious adverse reactions to RAC, particularly in swine, that have been documented (Marchant-Forde et al., 2003; Poletto et al., 2009, 2010a,b).

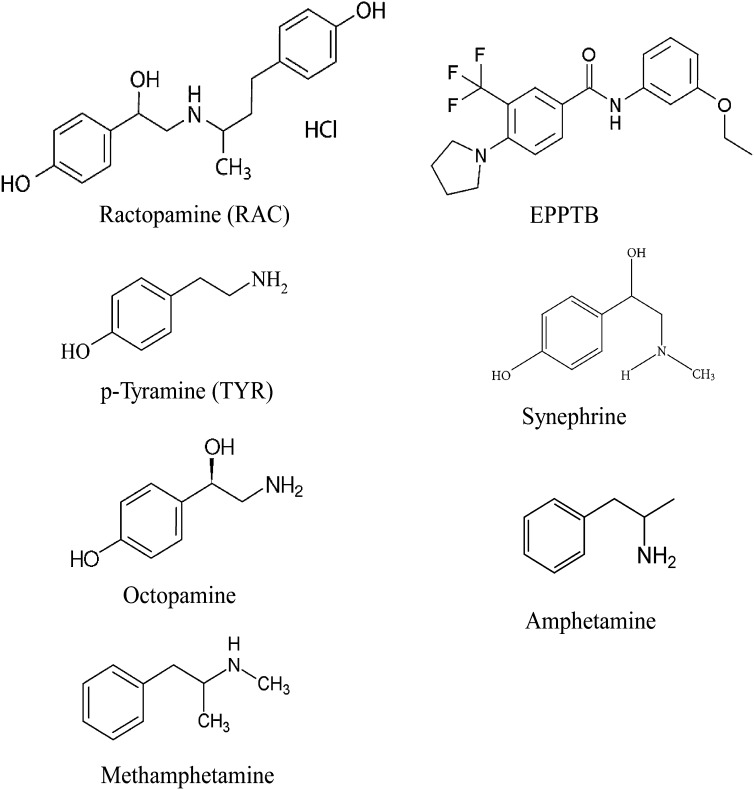

The structure of RAC resembles adrenergic agonists but also agonists of the recently discovered Gαs-coupled trace amine–associated receptor 1 (TAAR1) (Bunzow et al., 2001), including amphetamine, methamphetamine, p-tyramine (TYR), β-phenylethylamine (PEA), synephrine, octopamine, and 4-ethylphenol–substituted iodothyronamines (Scanlan et al., 2004) (Fig. 1). RAC and BUT are reported to exert their physiological effects by stimulating β1-adrenergic receptor (β1AR) and β2-adrenergic receptor (β2AR) expressed in skeletal muscle and adipose tissue (Mills et al., 1990). However, the molecular pharmacology of their effects has not been systematically investigated, even though it is structurally similar to the amphetamines, and elevated dopamine tone in the brains of RAC-fed swine has been reported (Marchant-Forde et al., 2003; Poletto et al., 2010b, 2011). Given the similarities between RAC and the pharmacophores recognized by TAAR1, we hypothesized RAC would be a TAAR1 agonist. To test this hypothesis, we monitored cAMP-dependent chloride conductances produced by Xenopus oocytes expressing the human cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (hCFTR) alone or together with either mouse TAAR1 (mTAAR1) or the human β2AR (hβ2AR). Our results indicate that RAC, contrary to expectations, is not an agonist of the hβ2AR but rather is a full agonist of the closely related mTAAR1. Since TAAR1-mediated signaling can influence cardiovascular tone (Fellows, 1947; Frascarelli et al., 2008; Herbert et al., 2008; Broadley, 2010; Fehler et al., 2010; Broadley et al., 2013) and behavior in several animal models (Miller, 2011; Revel et al., 2011; Achat-Mendes et al., 2012), our finding that RAC is a full mTAAR1 agonist constitutes a novel mechanism by which RAC can influence the physiology and behavior of pigs (Marchant-Forde et al., 2003; Poletto et al., 2009, 2010a,b) and other species. These findings should stimulate future studies to characterize the pharmacological, physiological, and behavioral actions of RAC in humans and other species exposed to this drug.

Fig. 1.

Structures of RAC, EPPTB, and other TAAR1 agonists: TYR, synephrine, octopamine, iodothyronamines, amphetamine, and methamphetamine.

Materials and Methods

Reagents.

IBMX (3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine), forskolin, isoproterenol, TYR, and racemic RAC were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). EPPTB [N-(3-ethoxyphenyl)-4-pyrrolidin-1-yl-3-trifluoromethylbenzamide] was synthesized in the Grandy laboratory according to previously published procedures (Bradaia et al., 2009), and its identity was verified using NMR. Purity was greater than 95%.

In Vitro Transcription.

hCFTR cDNA cloned into pBQ4.7 pasmid was a gift from Dr. D. C. Dawson (Department of Physiology and Pharmacology, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, OR). cRNAs for hCFTR and mTAAR1 (Bunzow et al., 2001) were generated using Ambion Messagem Machine T7 Ultra Transcription Kit (Ambion, Carlsbad, CA).

Preparation and Microinjection of Oocytes.

Xenopus laevis oocytes were prepared using our previously reported methods (Liu et al., 2012). In brief, oocyte follicular membranes were removed using 0.2 Wünsch units/ml Liberase TL (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN) for 1–2 hours in a Ca2+-free solution containing (in mM): 82.5 NaCl, 2 KCl, 1 MgCl2, and 5 HEPES (pH 7.5). Defolliculated oocytes were washed and maintained in a modified Barth’s solution containing (mM) 88 NaCl, 1 KCl, 0.82 MgSO4, 0.33 Ca(NO3)2, 0.41 CaCl2, 2.4 NaHCO3, 10 HEPES (hemisodium salt), and 250 mg/l Amikacin plus 150 mg/l gentamicin at pH 7.5. Stage V–VI oocytes were injected with 50 nl cRNA. The concentrations of cRNAs were as follows: 3.4 ng/μl for hCFTR, 1.2 ng/μl for hβ2AR, and 170 or 340 ng/μl for mTAAR1. RNA concentrations were adjusted so that the maximum steady-state stimulated conductance was less than 200 μS.

Whole-Cell Recordings.

The data were acquired using an Oocyte 725 amplifier (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT) and the pClamp 8 data acquisition program (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Individual oocytes were placed in a recording chamber (RC-1Z; Warner Instruments) and continuously perfused with frog Ringer's solution containing (in mM:) 98 NaCl, 2 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 1.8 CaCl2, and 5 HEPES–hemi-Na (at pH 7.4) and at indicated times were exposed to various reagents dissolved in frog Ringer's solution for lengths of time as indicated in each graph. Oocytes were maintained in the open circuit condition, and the membrane potential was periodically ramped from −120 to +60 mV over 1.8 seconds.

Statistical Analysis.

Data are presented as the mean ± S.E.M. Significance was determined by Student’s t test with P ≤ 0.05 considered significant.

Results

Effects of RAC, TYR, and EPPTB Are Specific to mTAAR1.

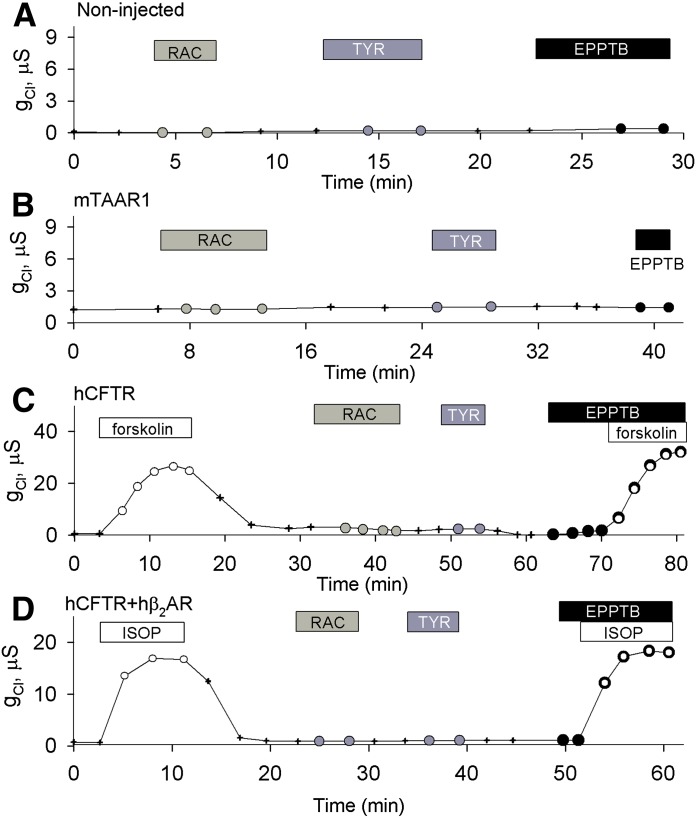

To assess the selectivity of RAC, TYR, and the TAAR1 antagonist EPPTB (Bradaia et al., 2009) for mTAAR1, we first determined no chloride conductance was evoked in uninjected oocytes, oocytes expressing hCFTR alone, mTAAR1 alone, or the combination of hCFTR and hβ2AR even at micromolar concentrations (Fig. 2). In contrast, oocytes expressing only hCFTR (Fig. 2C) responded to 10 μM forskolin by producing a robust chloride conductance, whereas oocytes coexpressing hCFTR and hβ2AR (Fig. 2D) responded to 10 μM β2AR agonist isoproterenol (Al-Nakkash and Hwang, 1999; Liu et al., 2005) by producing a chloride conductance that was insensitive to EPPTB (100 nM).

Fig. 2.

The effects of RAC, TYR, and EPPTB are specific to mTAAR1. (A) Shown is the response of a representative uninjected oocyte exposed sequentially, with washing in between, to 36 μM RAC (EC80), 76 nM TYR (EC80), and 100 nM EPPTB. (B) The response of a representative oocyte expressing mTAAR1 exposed sequentially, with washing in between, to 36 μM RAC, 76 nM TYR, and 100 nM EPPTB is shown. (C) The response of an oocyte expressing hCFTR exposed sequentially, with washing in between, to 10 μM forskolin, 36 μM RAC, 76 nM TYR, 100 nM EPPTB, and then 10 μM forskolin in the presence of 100 nM EPPTB is shown. The conductances stimulated by forskolin in the presence and absence of EPPTB were not significantly different (18 ± 5 μS, n = 4 versus 21 ± 6 μS, n = 4; P = 0.73). (D) The response of a representative oocyte coexpressing hCFTR and hβ2AR exposed sequentially, with washing in between, to 10 μM isoproterenol (ISOP), 36 μM RAC, 76 nM TYR, 100 nM EPPTB, and then 10 μM ISOP in the presence of EPPTB is shown. The conductances stimulated by ISOP in the presence and absence of EPPTB were not significantly different (12 ± 2 μS, n = 4 versus 13 ± 2 μS, n = 4; P = 0.66).

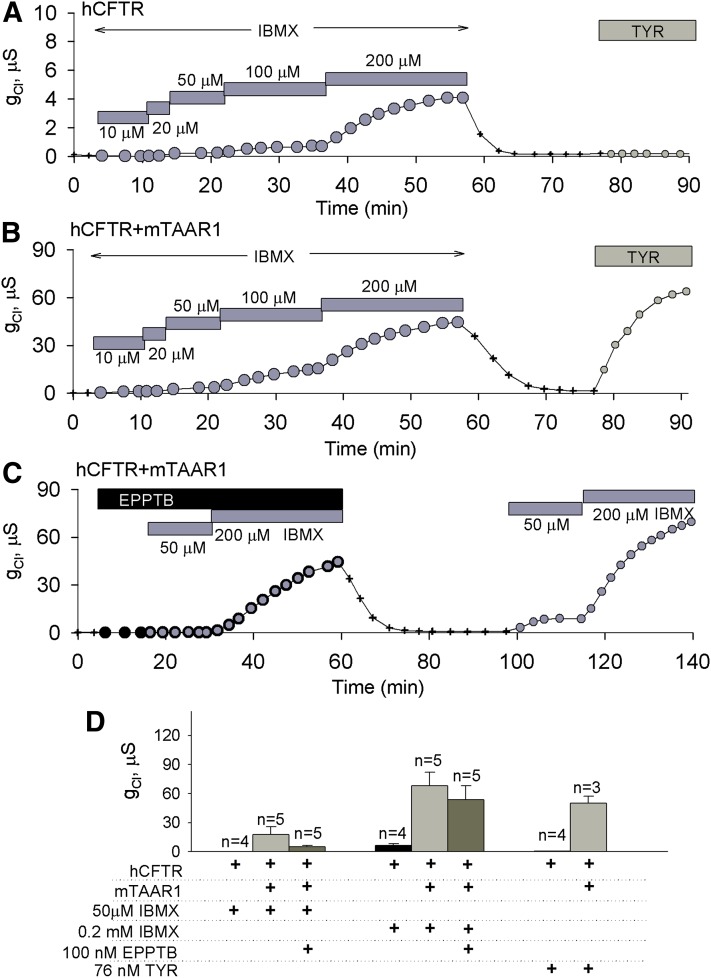

mTAAR1 Exhibits Constitutive Activity.

Given that mTAAR1 has been reported to display constitutive activity in other in vitro assays (Bradaia et al., 2009), we explored this possibility in oocytes by inhibiting the oocyte’s endogenous phosphodiesterase activity with IBMX. Oocytes expressing hCFTR alone or together with mTAAR1 were exposed to IBMX at concentrations ranging from 10 to 200 μM (Al-Nakkash and Hwang, 1999; Liu et al., 2005). As expected, increasing the concentration of IBMX resulted in small but significant increases in the chloride conductance produced by oocytes expressing only hCFTR that were insensitive to TYR at its EC80 concentration (76 ± 15 nM; Fig. 3, A and D). In contrast, exposing oocytes coexpressing hCFTR and mTAAR1 to either stepwise increases in IBMX (10, 20, 50, 100, and 200 μM) or TYR (76 nM) resulted in chloride conductances approximately 10 times those produced by oocytes expressing hCFTR alone (Fig. 3, B and D). To determine whether the robust chloride currents produced by oocytes coexpressing hCFTR and mTAAR1 were a function of mTAAR1-mediated increases in cAMP production, oocytes expressing both proteins were exposed to IBMX (50 and 200 μM) in the absence and presence of the TAAR1-selective antagonist EPPTB. We tested the effect of EPPTB over a wide range of CFTR conductance (the conductance stimulated by 200 μM IBMX ranged from 37 to 118 μS; n = 5). Within each oocyte, 100 nM EPPTB attenuated the response to 50 μM IBMX (Fig. 3C). The conductance averaged 18 ± 8 μS (n = 5) and 5 ± 1 μS (n = 5) in the absence and presence of 100 nM EPPTB (Fig. 3D). However, we are detecting a very small change in a data set with some variation, and so this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.14; n = 5). Nevertheless, the fact that EPPTB attenuated the response to 50 μM IBMX in every oocyte that we tested suggests that mTAAR1 is constitutively active.

Fig. 3.

mTAAR1 exhibits constitutive activity in Xenopus oocytes. (A) The response of a representative oocyte expressing hCFTR exposed to increasing concentrations of IBMX (10, 20, 50, 100, and 200 μM). After washout, TYR was added to the perfusate at its EC80 (76 nM) without effect. (B) The response of a representative oocyte coexpressing hCFTR and mTAAR1 exposed to increasing concentrations of IBMX (10, 20, 50, 100, and 200 μM). After washout, TYR (76 nM) produced a rapid and robust chloride current. (C) The response of a representative oocyte coexpressing hCFTR and mTAAR1 exposed to IBMX (50 and 200 μM) in the presence and absence of the TAAR1 antagonist EPPTB (100 nM). (D) A summary of the chloride conductances recorded from nine oocytes exposed to 50 and 200 μM IBMX.

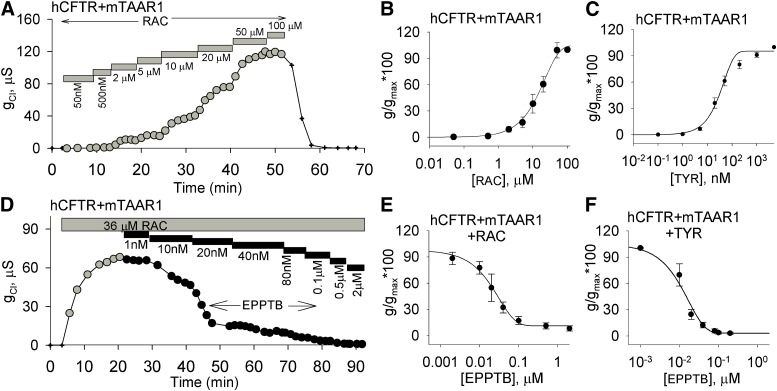

RAC Is a Full mTAAR1 Agonist.

Since the structure of RAC resembles the trace amine receptor agonists PEA and TYR (Fig. 1), and given RAC had no effect on oocytes coexpressing hβ2AR and hCFTR, we examined the effects of RAC on oocytes coexpressing mTAAR1 and hCFTR. Increasing concentrations of RAC (50 and 500 nM, and 2, 5, 10, 20, 50, and 100 μM) led to reversible stepwise increases in chloride conductance in oocytes coexpressing hCFTR and mTAAR1 (Fig. 4A), suggesting RAC binding to mTAAR1 resulted in an elevation of intracellular cAMP, the subsequent opening of hCFTR, and a concomitant increase in chloride current. The concentration-response profile for RAC was fit to a single exponential function from which an EC50 value of 16 ± 4 μM was calculated (Fig. 4B). TYR exerted a similar concentration-dependent response with an EC50 of 34 ± 6 nM (Fig. 4C). EPPTB blocked the effect of RAC (EC80 = 36 μM) in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 4D), with an IC50 of 20 ± 6 nM (Fig. 4E). EPPTB blocked TYR’s effect in a similar fashion with an IC50 of 12 ± 2 nM (Fig. 4F). These results demonstrate RAC is a full agonist for mTAAR1.

Fig. 4.

RAC and TYR elicit chloride conductances that are concentration-dependent and EPPTB-sensitive in oocytes coexpressing hCFTR and mTAAR1. (A) The response of a representative oocyte coexpressing hCFTR and mTAAR1 exposed sequentially to increasing concentrations of RAC from 50 nM to 100 μM is shown. (B) RAC produces concentration-dependent increases in chloride conductance. (C) TYR produces a concentration-dependent increase only in oocytes coexpressing hCFTR and mTAAR1. (D) The response of a representative oocyte coexpressing hCFTR and mTAAR1 exposed to 36 μM RAC. At steady-state stimulation, it was then exposed sequentially to increasing concentrations of EPPTB from 1 nM to 2 μM. (E) The concentration-response curve for EPPTB in the presence of RAC. (F) The concentration-response profile for EPPTB in the presence of TYR. The y-axis represents normalized conductance with the concentrations plotted on a log scale along the x-axis.

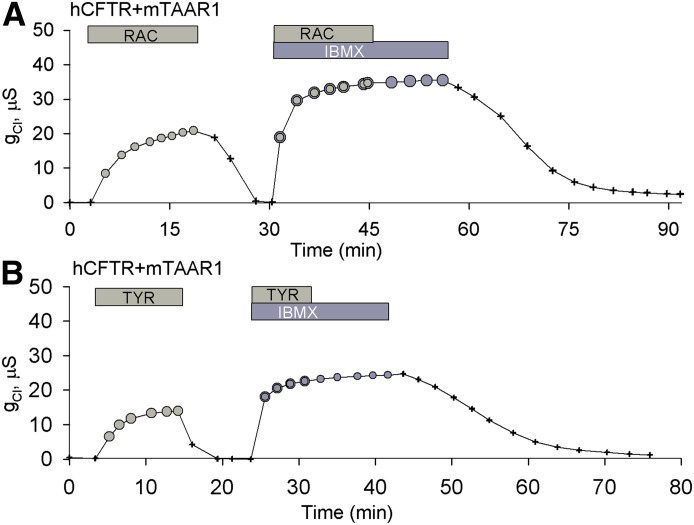

RAC and TYR Stimulate hCFTR via a mTAAR1 cAMP-Dependent Pathway.

To explore whether RAC exerts its effect on hCFTR via a cAMP-dependent pathway, we exposed oocytes coexpressing hCFTR and mTAAR1 to RAC (Fig. 5A) or TYR (Fig. 5B) at their respective EC80 values. After washout, oocytes exposed to a combination of RAC plus IBMX or TYR plus IBMX produced larger conductances than those produced by either agonist alone. Furthermore, IBMX treatment prevented the rapid drop in conductance that typically follows the removal of agonist from the perfusate. These results support the interpretation that both RAC and TYR exert their actions via a cAMP-dependent pathway coupled to the activation of mTAAR1.

Fig. 5.

RAC and TYR stimulate hCFTR via a mTAAR1-mediated cAMP-dependent pathway. (A) The response of a representative oocyte coexpressing hCFTR and mTAAR1 exposed to 36 μM RAC. After washing out, it was then exposed to 36 μM RAC and 1 mM IBMX. At steady state of stimulation, RAC was removed from the perfusate with no effect on conductance. Afterward, IBMX was removed from the perfusate, and the conductance gradually returned to background level. (B) The response of a representative oocyte coexpressing hCFTR and mTAAR1 exposed to 76 nM TYR (EC80). After washout, it was then exposed to 76 nM TYR and 1 mM IBMX. At steady state of stimulation, TYR was removed from the perfusate with no effect on conductance. Afterward, IBMX was removed from the perfusate, and the conductance gradually returned to background level.

Discussion

Contrary to expectations based on the literature (Mills et al., 1990, 2003), our in vitro results failed to confirm RAC as an agonist of the hβ2AR coexpressed with hCFTR in Xenopus oocytes. Importantly, whether the other documented target of RAC’s actions, human β1AR, responds to RAC when coexpressed with hCFTR in Xenopus oocytes remains to be investigated. Using an in vitro cAMP assay, Mills et al. (2003) reported RAC-stimulated cAMP accumulation in Chinese hamster ovary cells expressing cloned porcine β1AR and β2AR. Consequently, the differences between their results and ours could be due to the fact that the two studies used receptors from different species, different expression systems, and different methods of monitoring changes in intracellular cAMP levels. Therefore, a systematic re-examination of RAC’s pharmacology in vitro and in vivo seems warranted.

Furthermore, the results presented herein are consistent with the interpretation that RAC is a full agonist of mTAAR1. This Gαs protein–coupled receptor, the best-studied member of a 15-gene family in mice (16 in rats and 6 in humans; Lindemann and Hoener, 2005), is homologous to other biogenic amine receptors, including those that recognize norepinephrine, dopamine, and serotonin (Borowsky et al., 2001; Bunzow et al., 2001). In fact, mouse, rat, and human TAAR1 are all activated by these three important neurotransmitters, as well as by PEA, TYR, octopamine, synephrine, 3-iodothyronamine, amphetamine, methamphetamine, and methylenedioxymethamphetamine (ecstasy; Bunzow et al., 2001; Scanlan et al., 2004; Reese et al., 2007, 2014; Wainscott et al., 2007; Lewin et al., 2009). The conservation of TAAR1’s pharmacological profile across these three species supports the hypothesis that RAC is also a full agonist of bovine, porcine, and turkey species of TAAR1. Of course, additional experiments with the TAAR1 of those species will have to be performed to confirm this prediction. However, if RAC is confirmed to be an agonist of hTAAR1, it will be important to explore the extent to which variation in the hTAAR1 gene contributes to RAC responsivity and potentially constitutes a human health risk factor. Furthermore, it could be informative to determine whether RAC can influence the activity of other receptors coded for by this large gene family.

Although our results provide unequivocal evidence that RAC is a TAAR1 agonist, the relatively high EC50 value reported here (16 µM) exceeds the estimated total concentration in livestock flesh of about 1.25 µM (based on livestock feed of about 200 mg/head per day without consideration of metabolism). Further work will be needed to evaluate the potential impact on human health of the RAC residue present in meat prepared from RAC-fed livestock. Interestingly, two independent reports (Ungemach, 2004; Bories et al., 2009) conclude a minimum safe level for human exposure to RAC cannot be determined from the available evidence and recommend more extensive studies with larger sample sizes. Nevertheless, in light of our current findings, we suggest additional studies be undertaken to investigate the extent to which human, porcine, turkey, and bovine species of TAAR1 respond to RAC. The results of such an analysis are likely to be of interest to those concerned about animal welfare, the meat-eating public, the scientific community, and policy makers.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank A. Hamilton, Oregon Health and Science University librarian, for researching the background of RAC, and acknowledge the support provided by D. C. Dawson.

Abbreviations

- β1AR

β1-adrenergic receptor

- β2AR

β2-adrenergic receptor

- BUT

butopamine

- EPPTB

N-(3-ethoxyphenyl)-4-pyrrolidin-1-yl-3-trifluoromethylbenzamide

- hβ2AR

human β2AR

- hCFTR

human cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator

- IBMX

3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine

- mTAAR1

mouse trace amine–associated receptor 1

- PEA

β-phenylethylamine

- RAC

ractopamine

- TAAR1

trace amine–associated receptor 1

- TYR

p-tyramine

Author Contributions

Participated in research design: Grandy, Janowsky, Liu.

Conducted experiments: Liu.

Performed data analysis: Liu.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Grandy, Janowsky, Liu.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by the Methamphetamine Abuse Research Center [Grant P50-DA018165]; the VA Merit Review [5I01-BX000939]; and Research Career Scientist programs.

References

- Achat-Mendes C, Lynch LJ, Sullivan KA, Vallender EJ, Miller GM. (2012) Augmentation of methamphetamine-induced behaviors in transgenic mice lacking the trace amine-associated receptor 1. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 101:201–207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Nakkash L, Hwang TC. (1999) Activation of wild-type and deltaF508-CFTR by phosphodiesterase inhibitors through cAMP-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Pflugers Arch 437:553–561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bories G, Brantom P, Brufau de Barberà J, Chesson A, Cocconcelli P, Debski B, Dierick N, Gropp J, Halle I, Hogstrand C, et al. (2009) Scientific opinion of the panel on additives and products or substances used in Animal Feed (FEEDAP) on a request from the European Commission on the safety evaluation of ractopamine. EFSA J 1041:1–52 [Google Scholar]

- Borowsky B, Adham N, Jones KA, Raddatz R, Artymyshyn R, Ogozalek KL, Durkin MM, Lakhlani PP, Bonini JA, Pathirana S, et al. (2001) Trace amines: identification of a family of mammalian G protein-coupled receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98:8966–8971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradaia A, Trube G, Stalder H, Norcross RD, Ozmen L, Wettstein JG, Pinard A, Buchy D, Gassmann M, Hoener MC, et al. (2009) The selective antagonist EPPTB reveals TAAR1-mediated regulatory mechanisms in dopaminergic neurons of the mesolimbic system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:20081–20086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadley KJ. (2010) The vascular effects of trace amines and amphetamines. Pharmacol Ther 125:363–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadley KJ, Fehler M, Ford WR, Kidd EJ. (2013) Functional evaluation of the receptors mediating vasoconstriction of rat aorta by trace amines and amphetamines. Eur J Pharmacol 715:370–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunzow JR, Sonders MS, Arttamangkul S, Harrison LM, Zhang G, Quigley DI, Darland T, Suchland KL, Pasumamula S, Kennedy JL, et al. (2001) Amphetamine, 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, lysergic acid diethylamide, and metabolites of the catecholamine neurotransmitters are agonists of a rat trace amine receptor. Mol Pharmacol 60:1181–1188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehler M, Broadley KJ, Ford WR, Kidd EJ. (2010) Identification of trace-amine-associated receptors (TAAR) in the rat aorta and their role in vasoconstriction by β-phenylethylamine. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 382:385–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fellows EJ. (1947) The circulatory action of a number of phenylpropylamine derivatives. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 65:261–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frascarelli S, Ghelardoni S, Chiellini G, Vargiu R, Ronca-Testoni S, Scanlan TS, Grandy DK, Zucchi R. (2008) Cardiac effects of trace amines: pharmacological characterization of trace amine-associated receptors. Eur J Pharmacol 587:231–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y, Schinckel AP, Forrest JC, Kuei CH, Watkins LE. (1991) Effects of ractopamine, genotype, and growth phase on finishing performance and carcass value in swine: I. Growth performance and carcass merit. J Anim Sci 69:2685–2693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert AA, Kidd EJ, Broadley KJ. (2008) Dietary trace amine-dependent vasoconstriction in porcine coronary artery. Br J Pharmacol 155:525–534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin AH, Navarro HA, Gilmour BP. (2009) Amiodarone and its putative metabolites fail to activate wild type hTAAR1. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 19:5913–5914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindemann L, Hoener MC. (2005) A renaissance in trace amines inspired by a novel GPCR family. Trends Pharmacol Sci 26:274–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, O’Donnell N, Landstrom A, Skach WR, Dawson DC. (2012) Thermal instability of ΔF508 cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) channel function: protection by single suppressor mutations and inhibiting channel activity. Biochemistry 51:5113–5124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Veilleux A, Zhang L, Young A, Kwok E, Laliberté F, Chung C, Tota MR, Dubé D, Friesen RW, et al. (2005) Dynamic activation of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator by type 3 and type 4D phosphodiesterase inhibitors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 314:846–854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchant-Forde JN, Lay DC, Jr, Pajor EA, Richert BT, Schinckel AP. (2003) The effects of ractopamine on the behavior and physiology of finishing pigs. J Anim Sci 81:416–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GM. (2011) The emerging role of trace amine-associated receptor 1 in the functional regulation of monoamine transporters and dopaminergic activity. J Neurochem 116:164–176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills SE, Liu CY, Gu Y, Schinckel AP. (1990) Effects of ractopamine on adipose tissue metabolism and insulin binding in finishing hogs. Interaction with genotype and slaughter weight. Domest Anim Endocrinol 7:251–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills SE, Spurlock ME, Smith DJ. (2003) Beta-adrenergic receptor subtypes that mediate ractopamine stimulation of lipolysis. J Anim Sci 81:662–668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poletto R, Cheng HW, Meisel RL, Garner JP, Richert BT, Marchant-Forde JN. (2010a) Aggressiveness and brain amine concentration in dominant and subordinate finishing pigs fed the beta-adrenoreceptor agonist ractopamine. J Anim Sci 88:3107–3120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poletto R, Cheng HW, Meisel RL, Richert BT, Marchant-Forde JN. (2011) Gene expression of serotonin and dopamine receptors and monoamine oxidase-A in the brain of dominant and subordinate pubertal domestic pigs (Sus scrofa) fed a β-adrenoreceptor agonist. Brain Res 1381:11–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poletto R, Meisel RL, Richert BT, Cheng HW, Marchant-Forde JN. (2010b) Behavior and peripheral amine concentrations in relation to ractopamine feeding, sex, and social rank of finishing pigs. J Anim Sci 88:1184–1194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poletto R, Rostagno MH, Richert BT, Marchant-Forde JN. (2009) Effects of a “step-up” ractopamine feeding program, sex, and social rank on growth performance, hoof lesions, and Enterobacteriaceae shedding in finishing pigs. J Anim Sci 87:304–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reese EA, Bunzow JR, Arttamangkul S, Sonders MS, Grandy DK. (2007) Trace amine-associated receptor 1 displays species-dependent stereoselectivity for isomers of methamphetamine, amphetamine, and para-hydroxyamphetamine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 321:178–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reese EA, Norimatsu Y, Grandy MS, Suchland KL, Bunzow JR, Grandy DK. (2014) Exploring the determinants of trace amine-associated receptor 1’s functional selectivity for the stereoisomers of amphetamine and methamphetamine. J Med Chem 57:378–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revel FG, Moreau JL, Gainetdinov RR, Bradaia A, Sotnikova TD, Mory R, Durkin S, Zbinden KG, Norcross R, Meyer CA, et al. (2011) TAAR1 activation modulates monoaminergic neurotransmission, preventing hyperdopaminergic and hypoglutamatergic activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108:8485–8490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rikard-Bell C, Curtis MA, van Barneveld RJ, Mullan BP, Edwards AC, Gannon NJ, Henman DJ, Hughes PE, Dunshea FR. (2009) Ractopamine hydrochloride improves growth performance and carcass composition in immunocastrated boars, intact boars, and gilts. J Anim Sci 87:3536–3543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scanlan TS, Suchland KL, Hart ME, Chiellini G, Huang Y, Kruzich PJ, Frascarelli S, Crossley DA, Bunzow JR, Ronca-Testoni S, et al. (2004) 3-Iodothyronamine is an endogenous and rapid-acting derivative of thyroid hormone. Nat Med 10:638–642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungemach F(2004) Addendum in: Toxicological evaluation of certain veterinary drug residues in food, in 62nd meeting of the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives; 4–12 February 2003; Rome, Italy. Series 53, pp 118–164, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- Wainscott DB, Little SP, Yin T, Tu Y, Rocco VP, He JX, Nelson DL. (2007) Pharmacologic characterization of the cloned human trace amine-associated receptor1 (TAAR1) and evidence for species differences with the rat TAAR1. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 320:475–485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu ML, Deng JF, Chen Y, Chu WL, Hung DZ, Yang CC. (2013) Late diagnosis of an outbreak of leanness-enhancing agent-related food poisoning. Am J Emerg Med 31:1501–1503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen TT. (1984) The antiobesity and metabolic activities of LY79771 in obese and normal mice. Int J Obes 8:69–78 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen JT, Mersmann HJ, Hill DA, Pond WG. (1990) Effects of ractopamine on genetically obese and lean pigs. J Anim Sci 68:3705–3712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen JT, Nienaber JA, Klindt J, Crouse JD. (1991) Effect of ractopamine on growth, carcass traits, and fasting heat production of U.S. contemporary crossbred and Chinese Meishan pure- and crossbred pigs. J Anim Sci 69:4810–4822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]