Abstract

Objectives

This study was designed to assess the knowledge acquired by very young children (<6 years) trained by their own teachers at nursery school. This comparative study assessed the effect of training before the age of 6 years compared with a group of age-matched untrained children.

Setting

Some schoolteachers were trained by emergency medical teams to perform basic first aid.

Participants

Eighteen classes comprising 315 pupils were randomly selected: nine classes of trained pupils (cohort C1) and nine classes of untrained pupils (cohort C2).

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The test involved observing and describing three pictures and using the phone to call the medical emergency centre. Assessment of each child was based on nine criteria, and was performed by the teacher 2 months after completion of first aid training.

Results

This study concerned 285 pupils: 140 trained and 145 untrained. The majority of trained pupils gave the expected answers for all criteria and reacted appropriately by assessing the situation and alerting emergency services (55.7−89.3% according to the questions). Comparison of the two groups revealed a significantly greater ability of trained pupils to describe an emergency situation (p<0.005) and raise the alert (p<0.0001).

Conclusions

This study shows the ability of very young children to assimilate basic skills as taught by their own schoolteachers.

Keywords: EDUCATION & TRAINING (see Medical Education & Training), PRIMARY CARE, PUBLIC HEALTH

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study was designed to assess the knowledge and the ability to analyse situations acquired by very young children (<6 years) trained by their own teachers at nursery school.

This study demonstrated that first aid programmes for very young children can improve their ability to assess and describe a medical emergency situation and alert the medical emergency centre.

As required by the French national education system, randomisation was performed post hoc by the Ministry of Education and the children's performance was assessed by their own teachers.

No correlation can be established between the simulation used in this study and the way in which children would react in a real life emergency situation.

Introduction

In France, all trainee schoolteachers must learn basic first aid to be applied in the classroom and to be taught to their pupils. More than 9 875 000 school children ranging from 4-year-old nursery schoolchildren to end of secondary school teenagers, about 14–15 years of age, should receive this first aid training. This programme is called “apprendre à porter secours” (learn how to help) and pupils can obtain a ‘basic-lifesaving diploma’ at the end of secondary school. In a medical emergency, it is essential for the first witness to raise the alert and provide emergency first aid as soon as possible. First aid has been defined as help given to any ‘sick or injured person until professional help arrives’.1 The challenge of enabling everyone to provide life-saving first aid when faced with a medical emergency implies that everyone should be trained at some point in their life. The construction of knowledge and skills can be easily mobilised in a medical emergency situation. Many experts and emergency medicine societies recommend teaching first aid at school so that every citizen knows how to perform first aid appropriately and raise emergency alerts at the earliest possible time.2–6 Children can provide first aid measures and save lives by recognising life-threatening emergency situations and by making an emergency call.7

So far, however, there is no proof of the positive effects of first aid measures on patient outcome, except from basic life support. In addition, there could be concern about the adverse effects of training, such as recovery position performed by lays during cardiac arrest. However, one important obstacle to perform bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is the attitude towards helping. This is a fundamental problem in the general population, which could be addressed by first aid training at early childhood.

The age and weight of schoolchildren are significant factors determining the quality of CPR,8 as the depth of chest compression correlates with physical factors such as weight, body mass index and height.9 Abelairas-Gómez et al10 showed that 13 years was the minimum age at which children are able to achieve a minimum CPR quality similar to that achieved by adults. However, determining an age is controversial.8–11 These results do not justify withholding CPR training from younger children. Children who underwent training in younger years significantly improved their performance after 3–4 years.9 11 12 Young children who are not yet physically able to compress the chest can nevertheless be taught how to perform appropriate first aid and can therefore be the first link in the Chain of Survival by calling for help.13

Published studies on emergency first aid training at school have focused on children aged 6 years or older, often trained by first aid instructors.14–20 A recent systematic review highlighted that no conclusions can be drawn concerning the most effective first aid training courses or programmes or the age at which training can be most effectively provided.21 It is important to assess the effectiveness of standardised first aid training as a basis for policy development and provision of first aid training. More evidence is required to determine the most appropriate types of training according to the child's age, taking into account the child's psychomotor development and degree of autonomy.

Very limited scientific literature is available concerning children under the age of 6 years. Studies on emergency first aid training at school have focused on children often trained by first aid instructors, while few studies have assessed emergency first aid training at school provided by teachers themselves.

However, there are a number of arguments in favour of training provided by teachers,22–25 as teachers know their pupils and their representations and can work on the basis of their previous knowledge and experience. Teachers are familiar with each child's sensitivity and can measure the emotional charge associated with emergency situations. The teacher establishes a relationship of trust with the child and can use situations experienced in the classroom as a pretext for learning and enhancing knowledge. The teacher is familiar with the required curriculum and skills. The teacher is a mentor, and the child is able to imitate the teacher's first aid skills.

The aims of this preliminary study were to assess the knowledge and abilities of very young children trained in the nursery by their own teacher and to compare the results with those of age-matched untrained children.

Methods

This study, carried out in the Somme department (560 000 inhabitants), was supervised by the University Hospital Emergency Medicine Department, National Education Teachers and a University Research Unit Specialised in Health Education. This study took place in ‘real life’. Owing to the importance of public health issue, we were required to adapt our research methodology to the national education system's educational, legal and ethical constraints.

Intervention

Training of teachers

A programme was initially developed to train teachers in basic first aid to deal with an emergency situation. The most common emergency situations occurring in elementary schools were used to design this programme. In the Somme department, 2200 of all 3300 elementary schoolteachers have been trained by emergency medical teams, assisted by the Ministry of Education health professionals, since 2002. During a 6 h training session, the teachers learned when to alert the medical call centre and how to act when faced with trauma, burns, bleeding, a choking victim or an unconscious person. Teachers received first aid training to improve their prior knowledge and then worked on educational applications in the context of nursery schools. This training was conducted by emergency medical teams and education specialists, assisted by Ministry of Education health professionals.

Training of children by teachers

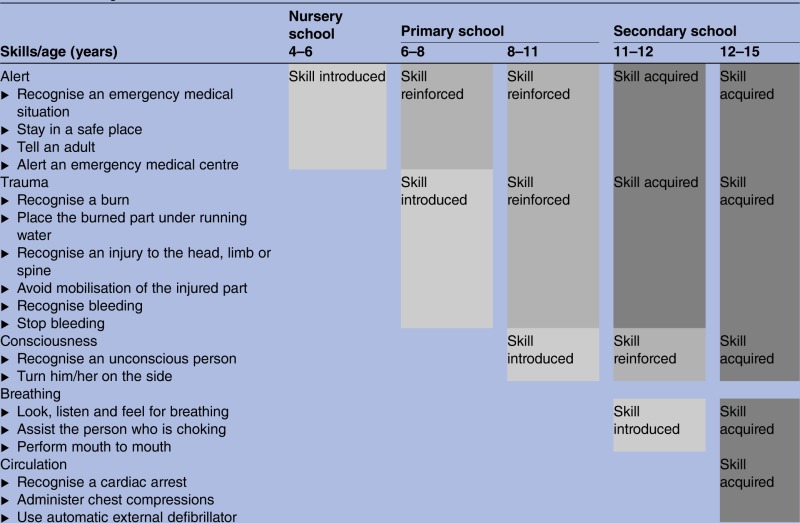

After training, the teachers had to integrate specific skills into various subjects of the curriculum, depending on the learning pace of the class. The children's psychological, cognitive and moral developments were taken into account when setting up the course. The principle of the course is to plan a yearly increase in complexity, allowing the revision of acquired skills and the learning of new skills.23–27 Young children in nursery schools should be able to recognise an ‘unusual’ situation and alert the medical emergency call centre. To do so, they need to dial the emergency medical number (phone: 15, Service d'Aide Médicale Urgente (SAMU) in France), describe what they have observed and name the various affected parts of the human body. Children aged between 6 and 8 years must be able to alert the SAMU by precisely locating the event. They must be able to describe injuries and perform simple tasks to deal with a burn, a bleeding wound or trauma. Children aged between 9 and 11 years must be able to recognise an unconscious patient, determine the presence of breathing and place the unconscious person on his or her side. In secondary education, they must learn how to assist a person who is choking and perform chest compression and defibrillation in the case of cardiac arrest. The progression of the child's abilities during the curriculum was assessed in the Somme department.

Teachers have introduced first aid knowledge and skills into the curriculum, suitable to the child's stage of psychological, cognitive and emotional development, as recommended by experts in the education of young children. For example, when teaching basic anatomy, teachers addressed the issue of how to deal with trauma. The number of hours of training therefore cannot be assessed in the context of this educational approach adapted to young children.

Participants

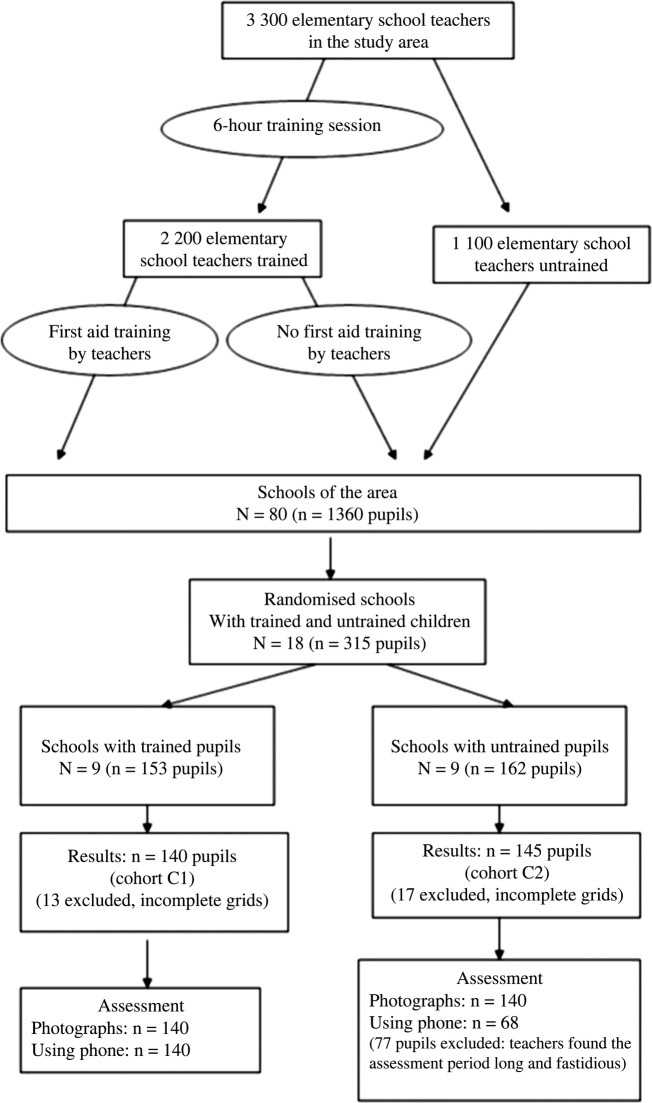

Owing to the requirements of the national education system, some children in nursery schools in this area were trained by their teachers, while others were not, either because their teachers did not wish to train them or were not trained themselves. This study was approved by the regional section of the Ministry of Education, which designated part of the region to participate in this study (80 schools, n=1360 pupils). Eighteen classes comprising 315 pupils were randomly selected: nine classes of trained pupils and nine classes of untrained pupils (figure 1). The untrained pupils had never received any first aid education.

Figure 1.

Flow chart.

Instrumentation

The children's ability to observe pictures and then to use a telephone to raise an alert were assessed. Three pictures illustrated three different situations, one of which did not require alerting the SAMU:

A boy who has fallen off a stepladder and who is holding his leg (figure 2).

A young girl crying because she has broken her doll (figure 3).

A young boy who has injured his hand while peeling an apple (figure 4).

Figure 2.

A boy who has fallen off a stepladder and is holding his leg.

Figure 3.

A young girl crying because she has broken her doll.

Figure 4.

A young boy who has injured his hand while peeling an apple.

Assessment of each child was based on nine criteria and was performed by the teacher 2 months after completion of first aid training. These nine criteria consisted of answers to the following questions, testing the child's ability to observe each picture and to decide whether or not to raise an alert: “What is happening?” and “You are alone with him (her), nobody is here to help you, what would you do?” The answers were classified into two categories: ‘expected answer’ (with keywords or synonyms) or ‘other answer’.

The expected answer in relation to the first picture was: “He has fallen over, his leg hurts”. The expected answer in relation to the second picture was: “She has broken her doll and is crying” and the expected answer in relation to the third photograph was “He has cut himself, he is bleeding”. The child was required to “alert the SAMU” for the first and third situations. The teacher then tested the pupil's ability to alert the SAMU in relation to the third picture. The teacher gave the children access to a standard landline telephone, playing the role of the SAMU emergency doctor. When the child did not use the telephone spontaneously, the teacher encouraged the child to do so. The teacher's instructions were: “You see, he has cut himself, he is bleeding. You are alone at home with him, the SAMU must be alerted, do it!” The assessment of the child's reaction was binary: did or did not. The three criteria were:

using the telephone;

introducing himself, explaining where he is;

describing the situation.

The pictures had been previously tested on two classes (not included in this study).

Procedure

The national education system required each child to be assessed by his/her own teacher because children of this age are not usually assessed, especially by an unknown adult not part of the classroom. In order to obtain the most objective results possible, written instructions were given and discussed individually with each teacher approximately 2 months after completion of first aid training.

Data analysis

To ensure anonymous grids, the results were collected by Ministry of Education staff. For reasons of confidentiality required by the national education system, the researchers did not have access to personal data from children. Only fully completed assessments were analysed. Data were presented as percentages with 95% CIs. Statistical analysis of the results was performed using a χ2 test (significance level: p<0.05). Analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (V.11.0, SPSS, Inc).

Results

For the overall analysis, 315 pupils were prospectively evaluated, 285 with complete grids were included: 140 trained children (cohort C1) and 145 untrained children (cohort C2; figure 1). The sex ratio (male/female) was 0.94 and the mean age was 5.4 years.

Only 68 children in cohort C2 were tested for their use of the telephone, as some teachers decided not to complete this assessment, which they considered to be time-consuming and fastidious.

Children's ability to observe pictures, describe the situation and raise the alert are shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Results: children's ability to observe pictures

| Exercise | Question and expected answers | C1 cohort percentage of expected answers (n=140) |

C2 cohort percentage of expected answers (n=145) |

OR | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Photograph 1 | What is going on? –He has fallen over, his leg hurts (criterion 1) |

67.9 (95) | 45.5 (66) | 2.5 | <0.001 |

| You are alone at home, what do you do? –I call the SAMU (criterion 2) |

62.1 (87) | 8.3 (12) | 18.2 | <0.0001 | |

| Photograph 2 | What is going on? –She has broken her doll and is crying (criterion 3) |

71.4 (100) | 41.4 (60) | 3.5 | <0.0001 |

| You are alone at home, what do you do? –I do not call the SAMU (criterion 4) |

75 (105) | 75.9 (110) | – | 0.24 | |

| Photograph 3 | What is going on? –He has cut himself, he is bleeding (criterion 5) |

75.7 (106) | 60.0 (87) | 2.8 | 0.01 |

| You are alone at home, what do you do? –I call the SAMU (criterion 6) |

66.4 (93) | 13.8 (20) | 12.4 | <0.0001 |

C1, trained pupils; C2, untrained pupils; SAMU, Service d'Aide Médicale Urgente.

The majority of trained pupils were able to describe the three pictures and gave the expected answers (67.9%, 71.4% and 75.7%, respectively). The ability to observe and describe the situation was significantly higher in cohort C1 for the three pictures (p<0.001 for the first and second pictures and p<0.01 for the third picture).

When the SAMU had to be alerted, the majority of trained pupils were willing to raise the alert.

A marked difference was observed between the two cohorts in terms of alerting the SAMU, which was significantly higher in cohort C1 (p<0.0001). In relation to the first picture, 61.9% of children in cohort C2 were willing to help the injured child after the picture had been explained to them, but did not know who to alert (73.8% for the third picture). Note that 23% of pupils in cohort C1 and 43.8% of pupils in cohort C2 misinterpreted picture 2 and the intention to act was not significantly different between the two groups (to help or comfort the girl; table 1).

Simulation exercise with a telephone using the third picture

This exercise involved the 140 trained children of cohort C1 and 68 children of the cohort C2. Overall, 55.7% pupils of cohort C1 knew how to use the telephone correctly and how to call the SAMU (vs 17.7% of children in cohort C2; p<0.0001; table 2), and 82.1% of children in cohort C1 gave their first name, last name and personal address (vs 33.8% of C2; p<0.0001; table 2). Lastly, 89.3% of children in cohort C1 correctly described the situation using the keywords “cut”, “hand” and “blood” (vs 75% of C2; p<0.01; table 2).

Table 2.

Results: simulation exercise with a telephone

| Exercise | Criteria | C1 cohort percentage of expected answers (n=140) |

C2 cohort percentage of expected answers (n=68) |

OR | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Use of the phone | 1—Using the telephone (criterion 7) | 55.7 (78) | 17.7 (12) | 5.9 | <0.0001 |

| 2—Introducing oneself, explaining the location (criterion 8) | 82.1 (115) | 33.8 (23) | 9 | <0.0001 | |

| 3—Describing the situation (criterion 9) | 89.3 (125) | 75 (51) | 2.8 | 0.01 |

C1, trained pupils; C2, untrained pupils.

Discussion

For all criteria, the majority of trained pupils gave expected answers and presented an appropriate reaction to the situation by recognising the medical problem and appropriately raising the alert. Comparison of the two cohorts revealed significant differences in terms of the ability of pupils to describe an emergency situation and raise the alert.

Observation capacity

The situation shown in each picture had not been previously raised or discussed in class. The teachers were not aware of the assessment methods used and therefore could not have prepared their pupils beforehand. The vast majority of trained pupils spontaneously gave expected answers without prompting from their teacher, making this result even more relevant. The results related to the non-emergency situation (young girl with a broken doll) showed that the observation capacity of trained pupils was significantly better than that of untrained pupils. The teachers of the trained cohort may have more generally emphasised observation capacities, as an emergency call to the SAMU (or to an adult) required an oral description of the situation. It would be interesting to test these capacities with other assessments comprising less obvious situations.

The situations described in the pictures focused on trauma and injuries, which correspond to common situations encountered by children.28–30 Many emergencies in western countries deal with acute emergencies in the field of internal medicine (heart attack, stroke, etc), but education experts from the Ministry of Education thought that it would be too emotionally disturbing for a young child to be faced with an adult in a life-threatening situation and therefore proposed that young children should act out situations involving injured children.

Intention to alert the SAMU

A highly significant difference was observed between the two cohorts in the two situations in which the SAMU had to be alerted. This study can be compared with Bollig's et al20 study in which the same ability was assessed. Despite the obvious willingness of untrained children to help, they did not know which number to dial or what role the SAMU played. It is noteworthy that trained pupils did not associate the picture of a broken doll with the need to alert emergency services as they were able to differentiate the various situations. This indicates that pupils are able to distinguish according to severity and that the induction over-sending is less likely.

Ability to raise the alert

Overall, trained pupils felt more confident than their untrained counterparts. Although two-thirds of trained pupils intended to call the SAMU in a medical emergency situation, only about one-half of them really knew how to call the SAMU with a landline. However, as a result of age-related psychological and cognitive maturity, the child's comprehension and the intention to take a particular action may not be automatically linked.

Integrating a first aid course in the curriculum

In a pilot study of 10 children, Bollig et al26 showed that kindergarten children aged 4–5 years can learn basic first aid with training provided by a first aid instructor and kindergarten teachers. The results of the present study support training by teachers themselves. It was considered important for teachers to learn first aid in order to be subsequently able to teach first aid to their pupils at school as part of ‘daily life education’. In contrast with first aid training provided by external instructors, teachers know their pupils. They can plan emergency first aid training along with other topics and assess the children in different ways. Finally, the teachers’ active participation in ‘role-playing games’, placing the child in a situation in which he/she is responsible for somebody else's health, appears to be a more efficient method of imparting complex skills, according to the concept of situated learning.27

Teacher training lasted 6 h. Our experience and an unpublished evaluation suggest that a 6 h training course is sufficient. Teachers have satisfactory prior first aid knowledge and are trained in science education. This 6 h training upgraded their knowledge and helped them to integrate first aid training in the curriculum. The effectiveness of this training needs to be evaluated and further studies are required to define the optimal design.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. As stated in the Methods section, randomisation was not performed before setting up the study for ethical reasons, as the Ministry of Education refused the idea of predefining two groups with and without first aid training. Assessment of the children's performance by their own teachers could constitute a bias in favour of the trained group. As explained in the Methods section, each child was assessed by his/her own teacher. It would be interesting to investigate differences between schoolteacher and first aid instructor interventions during a limited training period, as teachers integrate specific skills into various subjects of the curriculum, depending on the learning pace of the class. In addition, some teachers decided not to perform this assessment, which they considered to be ‘time-consuming and fastidious’. This study was conducted under ‘real life’ conditions. We had to adapt our research methodology to the educational, legal and ethical requirements of the French national education system.

Our study presents a number of biases. Use of the telephone was tested in only 48% of untrained children (C2). The main bias is that some teachers failed to comply with the study protocol, leading to incomplete data collection for certain aspects of the study, highlighting the difficulties of working with teachers who are sometimes unwilling to comply with study protocols. This bias favours the trained group. The follow-up rates differ markedly between trained and untrained children (for photographs 91.5% vs 86.4% and for the phone call 91.5% vs 42%, respectively). This reduces the strength of our results.

Although the instructions were explained to all teachers, evaluation and interpretation of these instructions may have differed between teachers. The pictures had been previously tested on two classes, but interpretation of the pictures may nevertheless have been biased. As this study was based exclusively on pictures, it would be interesting to include the observation of videos or ‘role-playing games’.

As this is the first assessment of its kind, we confined ourselves to a global assessment and did not take into account variables such as gender, class atmosphere or family background.

The child's knowledge and ability to analyse a situation from photographs were assessed by the teacher, although it may have been preferable to assess the acquired skills in a role play situation, as performed by several authors.20 26 It could be difficult to ensure similar and reproducible scenarios in each school. Photographs were designed by teachers themselves and had been previously tested on a sample of 50 children not included in the present study. Another possibility would be to evaluate children in the context of a video or serious game.

Finally, simulations present a number of limitations. No correlation can be established between the simulation used in this study and the way in which children would react in a real life emergency situation.

Prospects

In collaboration with the Ministry of Education, we discussed the possibility of increasing the complexity of the exercises on a yearly basis, which would enable revision of acquired skills and learning of new skills.21 Assessment of pupils at the end of elementary school and in secondary school will be the subject of other studies in our research unit.

To adapt this training to the children's psychological and physical development, pupils at the end of elementary school were taught which behaviour to adopt when faced with an unconscious person who is still breathing (table 3). Cardiac arrest was not addressed until children attained an age of 10 years, in line with Bollig's propositions.20 31 32 In order to meet public health requirements, emergency first aid training is now a compulsory part of the national curriculum in France.

Table 3.

Skills/age in the French curriculum

|

Implications

The challenge of enabling everyone to give life-saving first aid when faced with a medical emergency implies that everyone should be trained at some point in their life. The complexity of the training suggests that this training should be started as early as possible in the educational curriculum.

The public health goal is that every pupil should learn first aid. To achieve this objective, schoolteachers must first acquire appropriate emergency skills in the classroom. The present study concerned children aged 6 years or younger attending nursery school, trained by their own teachers. It demonstrated that first aid programmes given to very young children may improve their ability to assess and describe a medical emergency situation and alert the medical emergency call centre, as necessary. The results of trained pupils were significantly better than those of untrained pupils.

These preliminary results demonstrate the advantages of integrating this first aid course into the national curriculum, mainly provided by teachers themselves. Since 2006, the assessments carried out by our team support the current general implementation of this training course in all French schools. This programme is now compulsory, starting at the age of 4–6 years.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are very grateful to Mrs Kerneur and Mrs Lagarde (Ministry of National Education, France) for their very helpful contribution to this research and to Mr Jean-Michel Mercieca (Amiens University Hospital) for his help.

Footnotes

Contributors: CA and RG participated in the conception of the work, analyses, creating the draft, revision of the draft critically for important intellectual content and gave their final approval. CA, BN and MG contributed in the interpretation of the data, creating the draft, revision of the draft critically for important intellectual content and gave their final approval.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Parental/guardian consent obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.IFRC. International first aid and resuscitation guidelines 2011. Geneva: International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guidelines for basic life support. A statement by the basic life support working party of the European Resuscitation Council, 1992. Resuscitation 1992;24:103–10 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on School Health. Basic life support training school. Pediatrics 1993;91:158–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lester CA, Weston CF, Donnelly PD, et al. The need for wider dissemination of CPR skills: are schools the answer? Resuscitation 1994;28:233–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eisenburger P, Safar P. Life supporting first aid training of the public—review and recommendations. Resuscitation 1999;41:3–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chamberlain DA, Hazinski MF, European Resuscitation Council et al. Education in resuscitation: an ILCOR symposium: Utstein Abbey, Stavanger Norway. June 22–24, 2001. Circulation 2003;108:2575–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amsallem C, Ammirati C, Gignon M, et al. Appel d'un enfant: rôle de la régulation médicale. In. Urgences 2011, Société Française de Médecine d'Urgences, 2011:1035–44

- 8.Jones I, Whitfield R, Colquhoun M, et al. At what age can schoolchildren provide effective chest compressions?. An observational study from the Heartstart UK schools training programme. BMJ 2007;334:1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Plant N, Taylor K. How best to teach CPR to schoolchildren: a systematic review. Resuscitation 2013;84:415–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abelairas-Gómez C, Rodríguez-Núñez A, Casillas-Cabana M, et al. Schoolchildren as life savers: at what age do they become strong enough? Resuscitation 2014;85:814–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bohn A, Van Aken HK, Möllhoff T, et al. Teaching resuscitation in schools: annual tuition by trained teachers is effective starting at age 10. A four-year prospective cohort study. Resuscitation 2012;83:619–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bohn A, Van Aken H, Lukas RP, et al. Schoolchildren as lifesavers in Europe—training in cardiopulmonary resuscitation for children. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 2013;27:387–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koster RW, Baubin MA, Bossaert LL, et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2010 Section 2. Adult basic life support and use of automated external defibrillators. Resuscitation 2010;81:1277–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lester C, Donnelly P, Weston C, et al. Teaching schoolchildren cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Resuscitation 1996;31:33–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lewis RM, Fulstow R, Smith GB. The teaching of cardiopulmonary resuscitation in schools in Hampshire. Resuscitation 1997;35:27–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bernardo LM, Doyle C, Bryn S. Basic emergency lifesaving skills (BELS): a framework for teaching skills to children and adolescents. Int J Trauma Nurs 2002;8:48–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Uray T, Lunzer A, Ochsenhofer A, et al. Feasibility of life-supporting first aid (LSFA) training as a mandatory subject in primary schools. Resuscitation 2003;59:211–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lubrano R, Romero S, Scoppi P, et al. How to become an under 11 rescuers: a practical method to teach first aid to primary schoolchildren. Resuscitation 2005;64:303–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thurston M. Emergency life support training for school children: exploring local implementation and outcomes of the Heartstart UK School Programme within the context of the National Healthy School Standard. Centre for Public Health Research, University of Chester, externally commissioned research reports, 2005:1–86 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bollig G, Walh HA, Svendsen MV. Primary school children are able to perform basic life-saving first aid measures. Resuscitation 2009;80:689–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.He Z, Wynn P, Kendrick D. Non-resuscitative first-aid training for children and laypeople: a systematic review. Emerg Med J 2014;31:763–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tardif J. Pour un enseignement stratégique. L'apport de la psychologie cognitive. 2ème edition. Ed Logiques 1997.

- 23.Kohlberg L. Moral stages and moralization: the cognitive-developmental approach. In: Lickona T, ed. Moral development and behavior: theory, research, and social issues. New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1976:31–53 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith PL, Ragan TJ. Strategies for psychomotor skill learning. In: Instructional design. 3rd edn Chap. 15 Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2005:276–83 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bruner J. The process of education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1960 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bollig G, Myklebust AG, Østringen K. Effects of first aid training in the kindergarten—a pilot study. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2011;19:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lave J, Wenger E. Situated learning: legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press, 1991 [Google Scholar]

- 28. Enquête Permanente sur les accidents de la vie courante. Résultats 2012. Institut de Veille Sanitaire, Saint Denis, 2012. http://www.invs.sante.fr/content/download/83774/306579/version/1/file/TR13G263_%28resultats_Epac2012%29.pdf (accessed 10 Jul 2014)

- 29. Principales causes de décès des jeunes et des enfants en 2011. Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques, 2011. http://www.insee.fr/fr/themes/tableau.asp?ref_id=NATCCJ06206®_id=0 (accessed 10 Jul 2014)

- 30.Philippakis A, Hemenway D, Alexe DM, et al. A quantification of preventable unintentional childhood injury mortality in the United States. Inj Prev 2004;10:79–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bollig G. First Aid and the family. In: Craft-Rosenberg M, Pehler SR. Encyclopaedia of family health. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bollig G. First aid training in the kindergarten: a review of the literature and reflections from practical experience in two countries. New York: NOVA Science Publishers, 2013 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.