Abstract

Juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM) is a rare autoimmune disease, characterised by a systemic capillary vasculopathy that typically affects skin and muscle. Gastrointestinal involvement is relatively rare. We report the case of an 11-year-old girl admitted for investigation of skin rash, progressive symmetric proximal muscle weakness, dysphagia and weight loss. The diagnosis of JDM was confirmed and during hospitalisation the patient developed abrupt and intense right hypocondrium pain associated with nausea and vomiting. Abdominal ultrasound revealed a thick gallbladder wall (8 mm) with pericholecystic fluid and no evidence of gallstones. An acute acalculous cholecystitis was assumed and the patient was started on intravenous fluids, prednisolone and analgaesic therapy. Clinical resolution was verified after 48 h. We hypothesised that the vasculitic process of JDM could have been the basis for this complication as described in other autoimmune diseases.

Background

Juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM) is the most common idiopathic inflammatory myopathy of childhood with a reported annual incidence of 2–3 cases per one million children.1 2 It is a severe systemic autoimmune condition, involving primarily small vessel vasculopathy. Its aetiology remains unclear, and most likely results from the interaction of environmental triggers, immune dysfunction and specific tissue responses in genetically susceptible individuals.3 Typically it affects skin and muscle, with a characteristic rash and a symmetric proximal muscle weakness. These together with elevation of muscle enzymes, myopathic pattern on electromyography and typical muscle biopsy findings support the diagnosis of JDM according to the classical Bohan and Peter criteria.4 Extended criteria have been proposed in 2006,5 including the results of non-invasive examinations such as MRI.

Besides skin and muscle, the systemic vasculopathy may involve joints (arthritis), heart (conduction defects, myocarditis, dilated cardiomyopathy), lungs (interstitial lung disease) and the gastrointestinal tract (GI). GI involvement is present in up to 40% of patients with JDM2 6 and is mostly related to impaired pharyngeal and upper oesophageal motility, resulting in dysphagia. Acute abdominal pain may also occur. We report the case of a GI complication, which to the best of our knowledge has not yet been described in association with JDM.

Case presentation/investigation/treatment

We report the case of an 11-year-old Caucasian girl, with family history of type 1 diabetes mellitus (sister aged 9). Eleven months before admission, the patient progressively presented a heliotrope rash, Gottron's papules over the extensor surfaces, proximal muscle weakness (with repercussion in daily activities), mild intermittent abdominal pain, dysphagia for solid food and a weight loss of 6 kg. Given the cutaneous, muscular and GI involvement, the diagnosis of JDM was suspected and the patient was referred to paediatric rheumatology. The patient was then hospitalised for further investigation. Laboratory results revealed: normocytic normochromic anaemia (haemoglobin 9.6 g/dL; laboratory reference (LR) 10–14.5 g/dL); normal leukocytes (5.1×109/L; LR 4–11×109/L); elevation of the sedimentation rate (66 mm/1st hour; LR <16 mm/1st hour), aspartate aminotransferase (45 IU/mL; LR <38 IU/mL) and lactate dehydrogenase (994 IU/mL; LR 240–480 IU/mL); normal alanine aminotransferase (19 IU/mL; LR <40 IU/mL), creatine kinase (69 IU/mL; LR <170 IU/mL) and aldolase (16.2 U/L; LR <20 U/L); and negative antinuclear and anti-JO1 antibodies. MRI showed a hyperintense signal on T2-weighted images of the upper thighs and shoulder girdle muscles. Guided by those images, a right deltoid muscle biopsy was performed and the histopathological examination revealed a lymphocytic infiltration with a perivascular pattern, perifascicular muscle fibre atrophy and basophilic regeneration of muscle fibres. At admission, an investigation of other possible organ affections was also conducted. The ECG and echocardiogram were normal. Pulmonary function tests showed a reduced diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide. The abdominal ultrasound documented an upper limit liver dimension (major axis 14.9 cm), with a thin wall gallbladder without distension, oedema, pericholecystic fluid or lithiasis (figure 1).

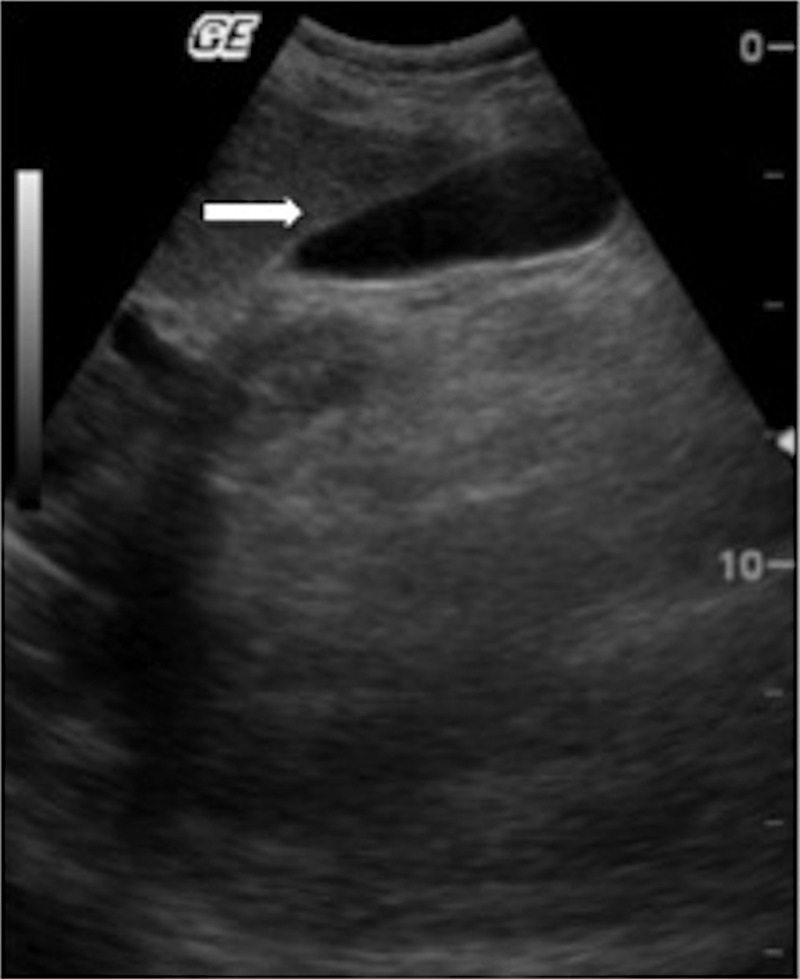

Figure 1.

First abdominal ultrasound (performed at admission). The arrow points to the thin gallbladder wall.

During this hospitalisation the patient was started on intravenous pulse methylprednisolone therapy (1 g/day—maximum dosage), maintained during 3 days followed by oral prednisolone (0.75 mg/kg/day), subcutaneous methotrexate (15 mg/m2/week) and folic acid supplementation (5 mg/week).

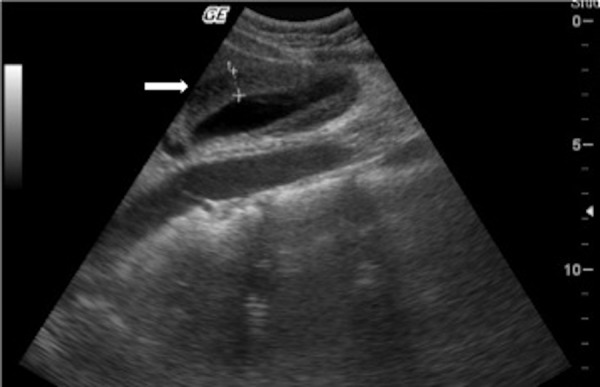

On the third day of hospitalisation the patient had a sudden, intense right upper quadrant pain, associated with nausea and vomiting. She was non-feverish and the abdomen was painful in the right hypochondrium, without signs of peritoneal irritation. Laboratory results revealed: normal leukocytes (5.0×109/L; LR 4–11×109/L); negative C reactive protein (0.1 mg/dL; LR <0.2 mg/dL); high sedimentation rate but similar to admission (66 mm/1st hour; LR <16 mm/1st hour); normal amylase (32 IU/mL; LR <100 IU/mL); slight elevation of aspartate aminotransferase (56 IU/mL; LR <38 IU/mL) and normal alanine aminotransferase (35 IU/mL; LR <40 IU/mL). An abdominal ultrasound was performed (figure 2) and revealed a thickening of the gallbladder wall of 8 mm, with pericholecystic and subhepatic fluid. There was no ultrasound evidence of gallstones, intrahepatic stones and common bile duct was of normal calibre. The hypothesis of an acute acalculous cholecystitis was assumed and after surgical consultation the patient was started on intravenous fluids and analgaesic therapy. Glucocorticoid therapy was maintained. Abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting resolved within 48 h. The patient was discharged after 72 h, medicated with prednisolone, methotrexate and folic acid.

Figure 2.

Second abdominal ultrasound (performed 3 days after admission). The arrow points to the thick gallbladder wall (8 mm).

Outcome and follow-up

One month after discharge, at the paediatric rheumatology consultation, the patient was without abdominal pain, nausea or vomiting. In this period, the patient gained 3 kg. There was also an evident improvement in muscle strength, with reacquired autonomy for daily activities. The sedimentation rate decreased from 66 to 25 mm/1st hour (LR <16 mm/1st hour). Aspartate aminotransferase and lactate dehydrogenase were normal.

Discussion

Abdominal pain that persists or progresses in a patient with JDM demands prompt investigation since it could indicate a complication that can be life-threatening. Intestinal wall ulceration or perforation is the most common cause. Rare cases of acute pancreatitis have also been described as a cause of abdominal pain in patients with JDM.7 The GI involvement might be related to an immune vasculitic mechanism. Endothelial dysfunction and damage resulting from antibody deposition, complement activation and inflammatory cytokines are likely to contribute to this small vessel vasculopathy.3 The histopathological process is evident as an acute endarteropathy, with arterial and venous intimal hyperplasia and occlusion of vessels by fibrin thrombi in the submucosa, muscularis and serosal layers.8 9 Chronic vasculopathy characterised by narrowing or complete occlusion of small-sized and medium-sized vessels has also been described in GI ulceration and perforation cases.10

In our patient, the acute abdominal pain raised the first hypothesis of intestinal vasculitis. Rare causes such as pancreatitis were in second line. The hypothesis of an acute cholecystitis was suspected based on the right hypocondrium pain. Later it was supported by the second ultrasound findings of thickening of gallbladder wall with pericholecystic and subhepatic fluid. These findings were not present in the first ultrasound performed only 3 days earlier (figure 1 vs figure 2). Gallstones were absent and bile ducts were of normal calibre. During these 3 days the patient was hospitalised, with an adequate oral food intake. Therefore we assumed an acute process, not related to fasting or lithiasis. Despite the possible utility of an hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid (HIDA) scan, we could not use one because of non-availability of HIDA at our centre; we supported our diagnosis with clinical and ultrasound findings. Acalculous cholecystitis accounts for approximately 10%11 12 of all cases of acute cholecystitis and its diagnosis can be challenging. It demands a high index of suspicion based on clinical features. Laboratory tests are non-specific. Ultrasound is the first-line examination and diagnostic criteria have been established, with gallbladder wall thickening (>3.5–4 mm) in the absence of gallstones considered as a major criterion.12

As far as we know, there are no published cases reporting this complication in relation with JDM. However, there are reported cases of acalculous cholecystitis related to a vasculitic mechanism in diseases such as juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus,13 14 polyarteritis nodosa,15 Shöenlein-Henoch syndrome16 and Churg-Strauss vasculitis.17 Russo et al18 have also described three cases of cholestasis in patients with JDM. This complication was functional, reversible and seemed to respond to steroid treatment.

In our patient, we hypothesise that the vasculitic process described for GI involvement in JDM led to an endothelial injury, ischaemia with local inflammatory response in the gallbladder wall and subsequent stasis. This process could have been the basis for the acalculous cholecystitis, similarly to what is described in the pathogenesis of other vasculopathies.

The treatment option was conservative management, based on maintaining steroids, adequate analgaesic therapy and intravenous fluids. Clinical resolution was verified after 48 h. The acalculous and unlikely infectious aetiology supported this treatment choice, avoiding surgery and its related morbidity. In the literature there are also other case reports of acalculous cholecystitis with clinical recovery using a conservative approach.16 17 19 Nevertheless, mortality in patients with acalculous cholecystitis can range from 10% (in community-acquired cases or with early diagnosis) to 90% (in critically ill patients or with late diagnosis).11 12 Therefore, with the conservative approach, it is essential to maintain strict surveillance for clinical deterioration, in which case surgical intervention would be required.

In summary, we described the case of a patient with JDM who developed an acute abdominal pain related to an acute acalculous cholecystitis. We proposed that this was a GI complication related to the vasculitic mechanism of JDM.

Learning points.

Abdominal pain in patients with juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM) demands prompt investigation of gastrointestinal involvement.

Acalculous cholecystitis should be considered in the differential diagnosis of acute abdominal pain in patients with JDM.

The systemic vasculitic mechanism may be responsible for the acalculous cholecystitis in JDM.

Conservative treatment with strict clinical surveillance can lead to complete resolution avoiding surgical intervention.

Acknowledgments

Dr Isabel Brito Lança: Paediatrician, Unidade Local de Saúde do Baixo Alentejo, EPE. Dr Fátima Furtado: Neuropaediatrician, Unidade Local de Saúde do Baixo Alentejo, EPE. Dr Sílvia Silva: Paediatrician, Unidade Local de Saúde do Baixo Alentejo, EPE. Dr Filipa Nunes: Paediatrician, Garcia de Orta's Hospital. Dr Teresa Alves: Radiologist, Garcia de Orta's Hospital. Dr Candida Barroso: Pathologist, Santa Maria's Hospital.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors were involved in the patient's care and contributed to the conception and design, acquisition , analysis and interpretation of the data, and gave the final approval of the version published. BFS and TM drafted the article. MJS and PA revised it critically for important intellectual content.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Mendez EP, Lipton R, Ramsey-Goldman R, et al. ; NIAMS Juvenile DM Registry Physician Referral Group . US incidence of juvenile dermatomyositis, 1995–1998: results from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases Registry. Arthritis Rheum 2003;49:300–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hutchinson C, Feldman B. Pathogenesis and clinical manifestations of juvenile dermatomyositis and polimyositis. In: Basow DS, ed. UpToDate. Waltham, MA: UpToDate, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wedderburn LR, Rider LG. Juvenile dermatomyositis: new developments in pathogenesis, assessment and treatment. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2009;23:665–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bohan A, Peter JB. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis. N Engl J Med 1975;292:344–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown VE, Pilkington CA, Feldman BM, et al. An international consensus survey of the diagnostic criteria for juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM). Rheumatology (Oxford) 2006;45:990–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feldman BM, Rider LG, Reed AM, et al. Juvenile dermatomyositis and other idiopathic inflammatory myopathies of childhood. Lancet 2008;371:2201–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.See Y, Martin K, Rooney M, et al. Severe juvenile dermatomyositis complicated by pancreatitis. Br J Rheumatol 1997;36:912–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laskin BL, Choyke P, Keenan GF, et al. Novel gastrointestinal tract manifestations in juvenile dermatomyositis. J Pediatr 1999;135:371–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crowe WE, Bove KE, Levinson JE, et al. Clinical and pathogenetic implications of histopathology in childhood polydermatomyositis. Arthritis Rheum 1982;25:126–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mamyrova G, Kleiner DE, James-Newton L, et al. Late-onset gastrointestinal pain in juvenile dermatomyositis as a manifestation of ischemic ulceration from chronic endarteropathy. Arthritis Rheum 2007;57:881–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Afdhal N Acalculous cholecystitis. In: Basow DS, ed. UpToDate. Waltham, MA: UpToDate, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huffman JL, Schenker S. Acute acalculous cholecystitis: a review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010;8:15–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shin SJ, Na KS, Jung SS, et al. Acute acalculous cholecystitis associated with systemic lupus erythematosus with Sjogren's syndrome. Korean J Intern Med 2002;17:61–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mendonça JA, Marques-Neto JF, Prando P, et al. Acute acalculous cholecystitis in juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 2009;18:561–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berengue C, Molto A, Kerr A, et al. Acalculous cholecystitis: first manifestation of polyarteritis nodosa in a patient with primary Sjögren. Med Clin (Barc) 2008;131:757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De la Peña A, Yuste JR, Beloqui O, et al. Acalculous cholecystitis in Shöenlein-Henoch syndrome: apropos of a case. Rev Med Univ Navarra 1995;39:126–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yüksel I, Ataseven H, Başar O, et al. Churg-Strauss syndrome associated with acalculous cholecystitis and liver involvement. Acta Gastroenterol Belg 2008;71:330–2 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Russo RA, Katsicas MM, Dávila M, et al. Cholestasis in juvenile dermatomyositis. Arthritis Rheum 2001;44:1139–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Juliano J, Wilson KD, Gertner E. Vasculitis of the gallbladder: case report and spectrum of disease. J Clin Rheumatol 2009;15:75–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]