Abstract

Internal jugular vein (IJV) thrombosis is a serious and potentially life-threatening occurrence in children, and is usually associated with malignancies, prolonged central venous catheterisation or deep seated head and neck infections or trauma. It has not been described in association with tuberculosis in children. The authors describe a 2-year-old child who presented with IJV thrombosis in association with clinical signs and symptoms of disseminated tuberculosis. There was complete resolution of symptoms after starting antitubercular drugs and warfarin. The authors emphasise that an active search for tuberculosis should be made routinely in patients with IJV thrombosis with an underlying mediastinal mass and/or generalised lymphadenopathy.

Background

Internal jugular vein (IJV) thrombosis among children is a rare occurrence. It is usually encountered in hospitalised patients with central venous catheters, hypercoagulability associated with malignancy, head and neck surgery, polycythaemia, hyperhomocysteinaemia and deep neck infections.1 2 IJV thrombosis has not been documented in children in association with tuberculosis. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first such report in the literature. The possible mechanisms are also discussed.

Case presentation

A 2-year-old female child presented with a 2-month history of intermittent low grade fever and slowly progressive upper abdominal distension. The child was also noticed to have diffuse swelling of the left side of the neck for 2 weeks duration along with significant weight loss and loss of appetite. There was no known contact with tuberculosis. No history of prolonged central venous catheterisation, deep seated head and neck infections or trauma was recorded.

At admission the child was looking sick. There was associated pallor and multiple bilateral matted cervical (left>right) axillary and inguinal lymph node enlargement along with diffuse tender swelling of the left side of the neck. Throat and dental examination were normal. Abdominal examination revealed firm hepatosplenomegaly (liver span 8 cm, spleen 3 cm below left costal margin).

Investigations

Haemoglobin was 9.3 g/dL, total leucocyte count 15×109/L, platelet count 250×109/L, erythrocyte sedimentation rate 40 mm in first hour, with normal prothrombin time and creatinine and liver function tests were normal. Mantoux test was negative. Gastric aspirate smears were positive for acid-fast bacilli. There was superior mediastinal widening in the chest X-ray. Ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration cytology of the cervical node was performed, which showed caseous necrosis and epitheloid granuloma, with acid-fast bacilli being negative. During the ultrasound of the neck, it was observed that the left IJV was showing evidence of thrombosis. Contrast-enhanced CT of the thorax and abdomen revealed multiple peripherally enhancing, centrally necrotic mediastinal nodes (figure 1) and intra-abdominal nodes, bilateral pleural effusion, pericardial effusion with enhancing pericardium and pericardial thickening, hepatomegaly and mild ascites. There was evidence of filling defect noted in the left IJV (figure 2). Echocardiography showed features of minimal pericardial effusion with fibrinous strands. Blood tests for proteins C and S, antithrombin III, homocysteine, antinuclear antibodies and antiphospholipid antibody were within normal limits. Bone marrow aspiration did not show any atypical cells or granuloma and acid-fast bacilli stain was negative. HIV serology was negative. Contact screening for tuberculosis was negative.

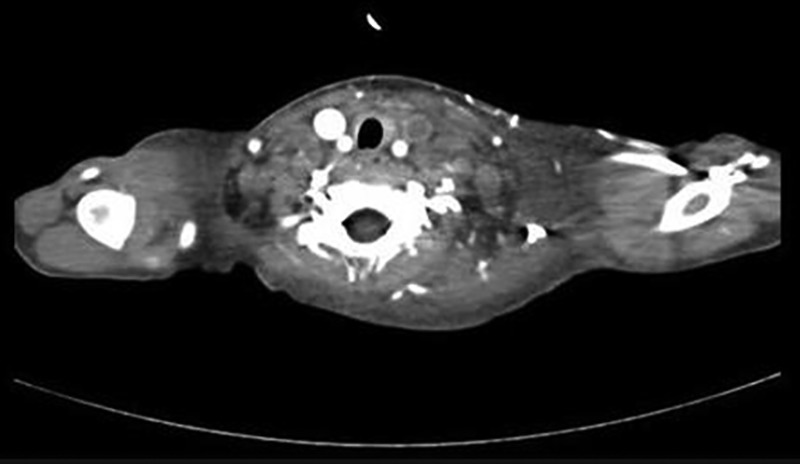

Figure 1.

Axial contrast-enhanced CT scan of thorax at the level of arch of aorta showing enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes with central areas of necrosis. Also seen are filling defects in superior vena cava due to the extension of thrombus from left internal jugular vein and brachiocephalic veins, bilateral pleural effusion and left axillary lymphadenopathy.

Figure 2.

Axial contrast-enhanced CT scan through of the neck shows non-enhancing filling defects within the left internal jugular vein suggestive of thrombosis.

Differential diagnosis

Based on these observations, the child was diagnosed as disseminated tuberculosis with IJV thrombosis. Although a possibility of malignancy was suspected, tissue diagnosis was suggestive of tuberculosis.

Treatment

The child was started on antitubercular drugs, steroids and low-molecular weight heparin followed later by warfarin. There was rapid resolution of fever. After 1 month, she demonstrated good weight gain. Repeat echocardiogram showed resolution of the pericardial effusion. Abdominal ultrasound showed a reduction in size of the para-aortic lymph nodes. The child has been on follow-up for the past 12 months and on antitubercular drugs and warfarin. The left IJV has recanalised on repeat ultrasound of the neck. Hepatosplenomegaly is not appreciable any more. Warfarin was stopped after 9 months.

Discussion

IJV thrombosis is a serious entity with a potentially fatal outcome. Its complications could include pulmonary embolism and sepsis as well as intracranial propagation of the thrombus. The history and examination in patients with IJV thrombosis may be vague and misleading, necessitating a high index of suspicion in order to arrive at the diagnosis. IJV thrombosis can occur anywhere from the intracranial IJV to the junction of the IJV and the subclavian vein where it forms the brachiocephalic vein.1 Common predisposing factors responsible for IJV thrombosis are central venous catheters in hospitalised patients, hypercoagulability of malignancy, head and neck surgery, polycythaemia, hyperhomocysteinaemia, deep neck infections, intravenous drug abuse, neck massage and assisted conception therapy.1 2 The pathophysiology behind the inherited and acquired factors leading on to development of thrombosis in neonates and children is based on Virchow’s triad of stasis, hypercoagulable state and vascular injury.3

In the present case, all these three factors may be in operation. In tuberculosis, large collective matted lymph node mass or mediastinal enlargement causing mechanical venous obstruction may cause stasis to blood flow.4 Tuberculosis has been postulated to be a hypercoagulable state that appears to develop secondary to the acute phase response.5 The production rate of fibrinogen, which is an acute-phase reactant, may increase greatly secondary to inflammation.5 6 Reduced antithrombin III and protein C levels, due to hepatic dysfunction secondary to tuberculosis, have been reported and may contribute to the hypercoagulable state.7 8 Vascular injury-induced increased platelet activity may be another mechanism for deep vein thrombosis in tuberculosis. In children with pulmonary tuberculosis, platelet activation occurs and has a good correlation with the extent of the disease.9 Vascular stasis secondary to the large matted tubercular lymph node mass in the mediastinum is a probable explanation for the IJV thrombosis in this patient. Complete response to antitubercular therapy also supports this view.

The thrombogenic potential of tuberculosis is not well known.10 Although there are occasional reports of thrombotic events (non-IJV thrombosis) in cervical tubercular lymphadenopathy,11 hepatic tuberculosis,12 gastrointestinal tuberculosis10 and pulmonary tuberculosis,13 the majority of these pertain to adults.11 13 It is notable that IJV thrombosis has not been documented in children in association with tuberculosis of any form. To the best of our knowledge, the present case report illustrates the first case of IJV thrombosis in association with paediatric tuberculosis. Thrombophilia work up for other causes other than tuberculosis was negative.

In conclusion, IJV thrombosis may complicate tuberculosis in children. The authors emphasise that an active search for tuberculosis should be made routinely in patients with IJV thrombosis with an underlying mediastinal mass and/or generalised lymphadenopathy. Although rare, IJV should be recognised as a complication of disseminated tuberculosis in order to initiate prompt therapy.

Learning points.

Tuberculous mediastinal lymph node can cause internal jugular vein (IJV) thrombosis.

Tuberculosis should be recognised as a treatable cause of IJV thrombosis.

Thrombosis in tuberculosis may occur without any coexisting thrombophilia state.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dr Ramesh Ananthakrishnan, Department of Radiodiagnosis for interpreting the radiological images.

Footnotes

Contributors: SD, RS, SK and SM managed the patient. SD and RS reviewed the literature and drafted the initial version of the manuscript. SK and SM contributed to literature review and critically revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to literature review, drafting of the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Badawi MA, Alam J, Khan Z. A rare presentation of mediastinal lymphoma: upper airway obstruction and internal jugular vein thrombosis. Ibnosina J Med BS 2012;4:60–2 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sheikh MA, Topoulos AP, Deitcher SR. Isolated internal jugular vein thrombosis: risk factors and natural history. Vasc Med 2002;7:177–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang JYK, Chan AKC. Pediatric thrombophilia. Pediatr Clin North Am 2013;60:1443–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gogna A, Pradhan GR, Sinha RS, et al. Tuberculosis presenting as deep vein thrombosis. Postgrad Med J 1999;75:104–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turken O, Kunter E, Sezer M, et al. Hemostatic changes in active pulmonary tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2002;6:927–32 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koster T, Rosendaal FR, de Ronde H, et al. Venous thrombosis due to poor anticoagulant response to activated protein C: Leiden Thrombophilia Study. Lancet 1993;342:1503–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindahl AK, Odegaard OR, Sandset PM, et al. Coagulation inhibition and activation in pancreatic cancer. changes during progress of disease. Cancer 1992;70:2067–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robson SC, White NW, Aronson I, et al. Acute-phase response and the hypercoagulable state in pulmonary tuberculosis. Br J Haematol 1996;93:943–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Büyükaşik Y, Soylu B, Soylu AR, et al. In vivo platelet and T-lymphocyte activities during pulmonary tuberculosis. Eur Respir J 1998;12:1375–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gupta R, Brueton M, Fell J, et al. An Afghan child with deep vein thrombosis. J R Soc Med 2003;96:289–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gowrinath K, Nizamiz MI, Kumar BEP, et al. Unusual complication of cervical tuberculous lymphadenopathy. Indian J Tuberc 2011;58:35–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Victor S, Jayanthi V, Madanagopalan N. Budd Chiari syndrome in a child with hepatic tuberculosis. Indian Heart J 1989;41:279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lang IM, Mackman N, Kriett JM, et al. Prothrombotic activation of pulmonary arterial endothelial cells in a patient with tuberculosis. Hum Pathol 1996;27:423–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]