Abstract

Objective

Therapeutic safety and efficacy are the basic prerequisites for clinical gene therapy. Herein we investigate the effect of high dose MCARD-mediated AAV9/SERCA2a gene delivery on clinical parameters, oxidative stress, humoral and cellular immune response, and cardiac remodeling.

Methods

Ischemic cardiomyopathy was generated in a sheep model. Then animals were assigned to one of two groups: control (n=10), and study (MCARD, n=6). The control had no intervention while the study group received 1014 gc of AAV9.SERCA2a 4 weeks post-infarction.

Results

Our ischemic model produced reliable infarcts leading to heart failure. The baseline ejection fraction (EF) in the MCARD group was 57.6±1.6 vs. 61.2±1.9 in the control group, (p>0.05). Twelve weeks post-infarction, the MCARD group had superior LV function compared to control: stroke volume index (46.6±1.8 vs. 35.8±2.5 mL/m2, p<0.05), EF (46.2±1.9 vs. 38.7±2.5%, p<0.05); and LV end systolic and end diastolic dimensions [41.3±1.7 vs. 48.2±1.4 mm; 51.2±1.5 vs. 57.6±1.7 mm], p<0.05. Markers of oxidative stress were significantly reduced in the infarct zone in the MCARD group. There was no positive T cell mediated immune response in the MCARD group at any time point. Myocyte hypertrophy was also significantly attenuated in the MCARD group compared to control.

Conclusions

Cardiac overexpression of the SERCA2a gene via MCARD is a safe therapeutic intervention. It significantly improves LV function, decreases markers of oxidative stress, abrogates myocyte hypertrophy, arrests remodeling and does not induce a T cell mediated immune response.

Introduction

Heart failure is a major public health problem affecting more than 23 million people worldwide. In recent decades there have been improvements in myocardial revascularization and medical therapies reducing 5-year mortality; however, the number of patients developing heart failure has steadily increased1. One explanation for these phenomena is that current surgical and therapeutic approaches are palliative and do not address the molecular pathogenesis of heart failure. Delivery of recombinant DNA to cardiac myocytes in situ for correction of genetically acquired transformations or by overexpression of critical signaling components which are down-regulated is an attractive proposition. It became clear, however that gene therapy is a complex process in which tissue targeting, route of delivery, cellular trafficking, regulation of gene expression, biological activity, dose of therapeutic transgene, and many other factors must be considered. In our view, prior to the advent of MCARD, systems allowing for gene delivery to the majority of myocytes in situ did not exist. Not surprisingly, the results of the CUPID trial using an inefficient intracoronary delivery route showed no demonstrable significant improvement in LV function in patients in any group, using doses up to and including 1013 gc of AAV1 encoding SERCA2a2. Preclinical data using the same dose of AAV1.SERCA2a and the same delivery approach resulted in detectable gene expression in 0% (3/6) and less than 1% (3/6) of myocytes the ovine heart3. In simple antegrade intracoronary delivery more than 99% of the vector promptly disappears into the systemic circulation4. Thus, we believe that gene delivery is the rate-limiting barrier to effective heart failure gene therapy.

We and others have shown that gene transfer with SERCA2a improves ventricular function in an experimental model of heart failure5, 6. However, SERCA2a overexpression enhances the heart’s energetic state and may potentially increase the probability of ventricular arrhythmias7, 8. Therefore, a careful analysis of the adverse cardiac effects of SERCA2a, especially in high doses, using an efficient delivery system like MCARD, must be completed prior to clinical translation.

For our study we chose adeno-associated virus (AAV), which is currently among the most frequently used viral vectors for gene therapy. The AAV1 vector was used in a phase I/II HF gene therapy clinical trial2. We have used AAV1 and AAV6 as well in previous studies5, 9. To achieve prolonged cardiotropic transgene expression stable for up to one year, it was shown that AAV9 may be superior to other serotypes10, 11. Nonetheless, AAV vectors have been shown to evoke cellular and humoral immune responses with T cells activated toward the expressed transgene and the vector capsid proteins12. Therefore we hypothesize that combining a high transgene dose with a highly efficient, cardiac-specific delivery method like MCARD would simultaneously enhance efficacy and limit potentially dangerous systemic exposure, abrogating an untoward immune response.

In the present study we aimed to investigate the effect of MCARD-mediated high dose AAV9/SERCA2a on left ventricular function, therapeutic safety of multiple organs, oxidative stress, cellular and humoral immune response, and cardiac remodeling in a relevant pre-clinical model of heart failure.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Study design

All animals received humane care in compliance with the NIH regulations and the protocol was approved by Carolinas Medical Center. An ischemic cardiomyopathy model was generated in sixteen Dorsett male sheep weighing 49.7±2.5 kg. The sheep were then randomly divided into two groups: control (n=10) and study (n=6) respectively. After four weeks, sheep in the study group underwent cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) including MCARD-AAV9/SERCA2a gene transfer. Hemodynamic and energetic studies were conducted at baseline, 3, and 12 weeks post infarction in both groups. The animals were then humanely euthanized and tissue was harvested and stored for further analysis.

Animal model of heart failure

The proximal portion of the first and second branches of the circumflex artery were identified and surgically ligated as previously described5.

MCARD and Gene Delivery

Surgical details of the MCARD procedure have been described previously in detail5, 9. Briefly, following sternotomy CPB was established via bicaval and right carotid artery cannulation. The aorta was cross-clamped. Cold (4°C) Del Nido cardioplegia solution was delivered antegrade. Closed-loop cardiac isolated circuit flow was initiated. The virus solution consisting of 1014 genome copies of AAV9/SERCA2a was injected into the retrograde coronary catheter and recirculated for 20 min. The circuit was then flushed to wash out residual vector. After cross clamp removal the animals were weaned from bypass and the chest was closed. All animals received critical cardiac postoperative care.

Recombinant AAV9/SERCA2a vector construction

Vector production, harvest, purification and testing were done from cell lysates by the Penn Vector Core (http://www.med.upenn.edu/gtp/vectorcore/). The recombinant AAV9.SERCA2a vector used in this study contains an AAV serotype-9 viral capsid and a single strand: ~4.5-kb DNA containing the human SERCA2a cDNA driven by a Cytomegalovirus immediate-early promoter/enhancer, a hybrid intron, and a bovine growth hormone polyadenylation signal.

Cardiac parameter measurements

Six-lead electrocardiography (MAC 1600, Hewlett-Packard, CA) was performed in all resting animals at baseline, immediately post-infarction and at twelve weeks with analysis of waveform components. Transthoracic and transepicardial echocardiography with color flow Doppler was performed with a 7-MHz transducer (Acuson, CA). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Signa LX, GE Healthcare, UK) acquisition and analysis of cardiac hemodynamics were generated for each animal at selected timepoints. Evaluation of cardiac cycles was obtained with cardiac MRI software (//segment.heiberg.se/).

PCR detection of AAV vector genome

RNA and DNA were isolated from specimens using the Chemagen MSM1 kits to set up separate RT-PCR and qPCR assays for SERCA2a mRNA and viral AAV9.CMV.SERCA2a DNA. To examine the expression of SERCA2a, customized kits designed by Abiomed Systems generated the SERCA2a primers. The level of ovine GAPDH RNA was used to calculate normalized expression with the ΔΔCt method for the RT-PCR values. Absolute genomic copies of SERCA2a DNA were quantified with the standard normal curve.

Histology and Electron microscopic assessment of mitochondrial abundance and fractional volume

LV sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Each field was scanned with a computer-generated microscale and analyzed blindly using 9–11 randomly selected tissue sections from each of the hearts with image analysis software. For mitochondrial assessment samples were analyzed with a Phillips Transmission Electron Microscope (CM 10, MI). Images were captured with a digital camera system. Mitochondrial abundance per unit area and fractional volume of mitochondria were estimated using the unbiased morphometric stereology approach as previously described13.

Oxidative markers (MDA, 4-HNE)

LV tissue was homogenized and centrifuged (Fisher Scientific, GA). Protein concentration was measured using Protein Assay kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Bio-Rad, CA). Protein conjugates of malondialdehyde (MDA) and 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) were measured using enzyme immunoassays (Cell Biolabs, Inc., CA).

Total antioxidant capacity (TAOC)

Total antioxidant capacity was measured in LV samples using colorimetric microplate assay for total antioxidant power (Oxford Biomed. Res., MI). TAOC was expressed in Cu2+-reducing equivalents against a uric acid standard and normalized for the protein content of the sample.

T cell-mediated response (IFN-γ ELISPOT assay)

IFN-γ ELISPOT assays were performed according to a previously described protocol14. Peptide specific cells were represented as spot-forming cells (SFC) per 106 cells and were calculated by subtracting spot numbers.

AAV9 Neutralizing antibody (NAb) assay

NAb assays were performed by incubating the serotype 9 of AAV.CMV.LacZ with 2-fold dilutions of heat-inactivated sheep serum and determining b-galactosidase expression in Huh7 cells. The limit of detection for the assay is 1:5 serum dilution. AAV9-specific total NAb titers were determined by ELISA14.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as average ± standard error of the mean. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for normality was applied to each data set. Single analysis of variance was performed across time (e.g. Baseline, 3 Weeks, 12 Weeks) for each parameter, then unpaired t-tests (p<0.05 significance) were used to assess differences between any two time points or differences at the same time point between groups (e.g. study vs. Control).

Results

Model of ovine post-ischemic HF and operative results

All animals in both groups sustained a large transmural postero-lateral infarct with moderate to severe LV dysfunction. In the study group (MCARD-AAV9/SERCA2a) all sheep survived without incident and were humanely euthanized at 12 weeks. Average CPB and cross-clamp times were 143±6 and 77±5 minutes respectively. In one case in the control group the sheep developed refractory ventricular fibrillation after coronary ligation and was excluded from the study. LV infarct size was similar between the control and study groups (19.4±2.1% vs. 20.6±1.6%, p>0.05).

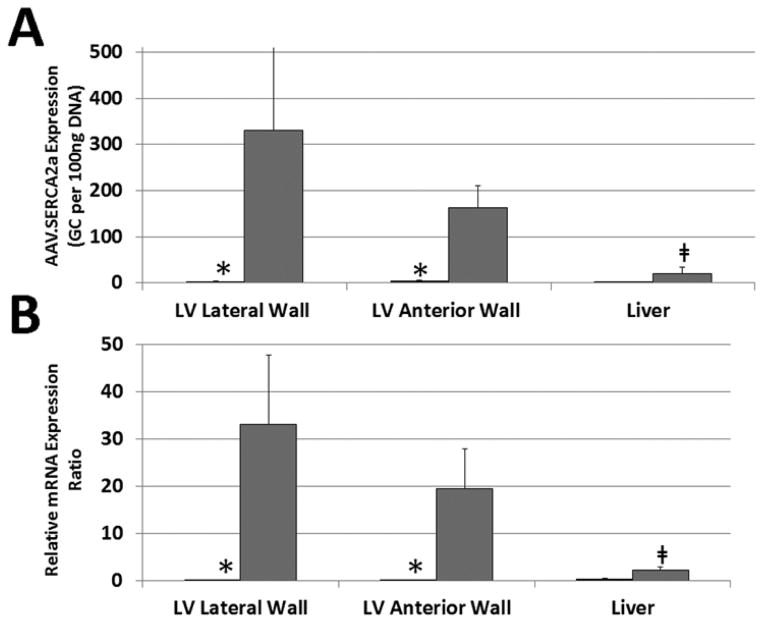

Cardiac and Liver Expression after high dose AAV9/SERCA2a gene transfer

Cardiac tissue delivery of SERCA2a genome copies (GC) in the MCARD-AAV9/SERCA2a group was significantly increased in the LV anterior and lateral walls compared to the liver and to heart tissue from the control group, both p<0.05 (Fig. 1A). Conversely, there was no difference in SERCA2a GC in the liver between the two groups. The same trends were observed using RT-qPCR to assess the relative expression of SERCA2a in cardiac samples in the study group compared with control (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

A. QPCR of SERCA2a biodistribution in heart and liver tissue (genome copies per 100ng DNA). B. Relative expression by RT-qPCR of SERCA2a/GAPDH in heart and liver tissue. MCARD-AAV9/SERCA2a group: Grey columns. Control group: Black columns. *p0.05 difference between groups. ╪p<0.05 difference within groups.

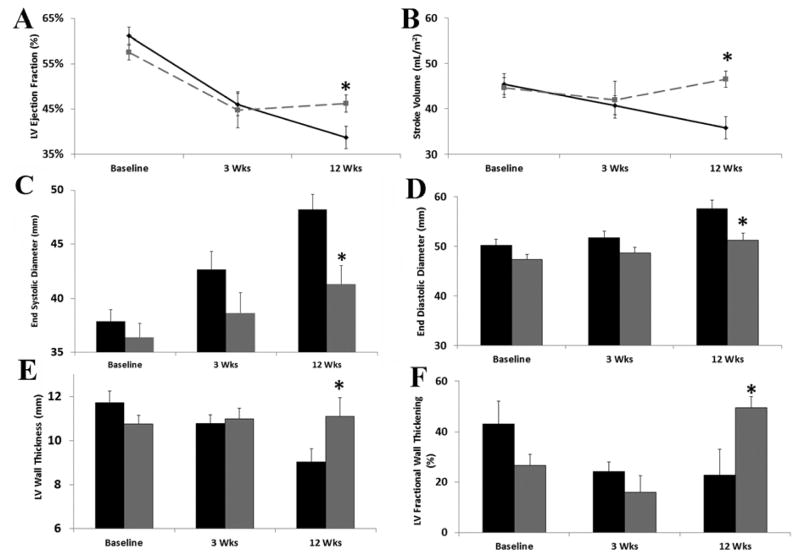

Cardiac function and LV remodeling

Global cardiac function was not significantly different between groups at baseline MRI. Creation of a myocardial infarction resulted in deterioration of heart performance in both groups: at 3 weeks in the MCARD and control groups respectively there was a decrease in ejection fraction (EF) by 22.6±5.5% and 24.7±3.4%, an increase in end-diastolic volume (EDV) by 22.7±6.0% and 22.0±6.7%, and an increase in end-systolic volume (ESV) by 57.8±6.2% and 71.0±11.4%, respectively (all p>0.05). At twelve weeks, MCARD-AAV9/SERCA2a treated HF animals showed significant improvement in systolic and diastolic LV function compared to the control group (EF: 46.2±1.9 vs. 38.7±2.5%; stroke volume index (SVi): 46.6±1.8 vs. 35.8±2.5 ml/m2; ES diameter: 41.3±1.7 vs. 48.2±1.4 mm; ESV: 66.7±5.0 vs. 80.3±5.1 ml; ED diameter: 51.2±1.5 vs. 57.6±1.7 mm; all p<0.05). Analysis of LV remodeling revealed significantly decreased LV end-systolic volumes and end-diastolic dimensions after gene therapy (Fig. 2A,B,C,D).

Figure 2.

Baseline, 3 weeks post-infarction, and 12 weeks post-infarction values for A. Left ventricular ejection fraction (%), B. stroke volume index (mL/m2), C. end systolic diameter (mm), D. end diastolic diameter (mm), E. left ventricular wall thickness (mm), F. left ventricular fractional wall thickening (%). MCARD-AAV9/SERCA2a group: Grey. Control group: Black. *p<0.05 difference between groups.

In line with improvements in global cardiac function, assessment of regional contractility demonstrated that LV wall thickness in the MCARD group is relatively stable and remains approximately 11 mm across time points. This finding suggests a high likelihood of recovery of regional contractile function after myocardial infarction15, whereas control group LV thickness was significantly decreased after 12 weeks for which the chances of recovery are very low (Fig. 2E). Also, LV fractional systolic wall thickening was significantly greater in the MCARD-AAV9/SERCA2a group at 12 weeks than in the control group (48.3±2.9% vs. 17.6±3.7%, p<0.01) (Fig. 2F).

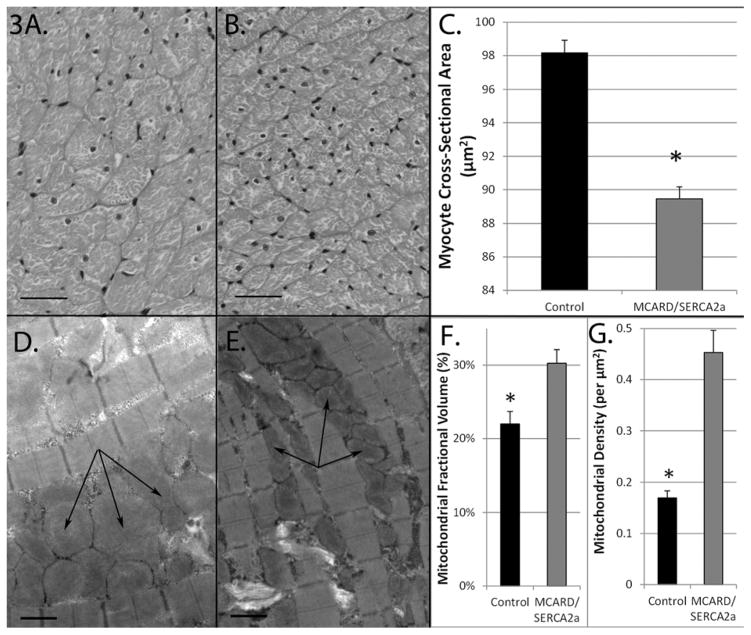

Myocardial hypertrophy and mitochondrial abundance and fractional volume

The cross sectional areas of myocytes from MCARD sheep were significantly smaller than those in control sheep (98±0.7 vs. 89±0.7 μm2, p<0.01, Fig. 3A,B,C), indicating significantly less myocyte hypertrophy. The mitochondria in the control group occupied a smaller fraction of total tissue volume than MCARD (22.0±1.7 vs. 30.2±1.9%, p<0.05), and also exhibited a lower mitochondrial density (0.16±0.01 vs. 0.45±0.04 per μm2, p<0.05). These findings are consistent with an increase in mitochondrial swelling in the control group (Fig. 3D,E,F,G).

Figure 3.

Morphometric analysis of myocytes and mitochondria. Hematoxylin and eosin stained infarct border zone tissue cross section (scale bar = 40μm) from A. Control, B. MCARD-AAV9/SERCA2a. C. Average cross sectional cardiac myocyte area in infarct border zone (μm2). D. Transmission electron microscopy of infarct border zone tissue (scale bar = 1μm) (control, arrows indicate mitochondrial swelling). E, MCARD-AAV9/SERCA2a (arrows indicate normal-appearing mitochondria). F. Average stereological estimates of: F. mitochondrial fractional volume (%) and, G. mitochondrial density (per μm2). MCARD-AAV9/SERCA2a group: Grey columns. Control group: Black columns. *p<0.05 difference between groups.

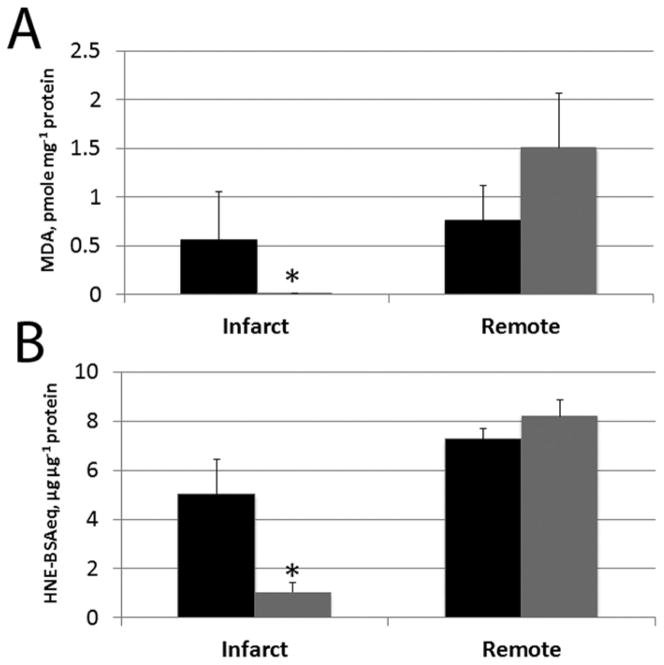

Oxidative stress and TAOC markers

In the MCARD group MDA and HNE conjugate concentrations were significantly suppressed in the infarct zone compared to the remote zone (MDA: 0.00±0.00 vs. 1.51±0.24 pmole/mg protein; HNE: 1.04±0.41 vs. 8.22±0.96 μg/μg protein; p<0.05), whereas the control group showed no significant difference between these zones (Fig. 4A, B). We did not find any significant differences in antioxidant capacity (TAOC) between groups or within groups, p>0.05).

Figure 4.

Oxidative markers. In infarct and remote tissue zones: A. 4-hydroxynonenal (HNE)-protein conjugates, in HNE-bovine serum albumin equivalents (μg/μg protein), B. Malondialdehyde (MDA) concentration (pmole/mg protein. MCARD-AAV9/SERCA2a group: Grey columns. Control group: Black columns. *p<0.05 difference within groups.

Blood work and ECG safety profile

Complete blood counts and chemistry analysis for comprehensive metabolic evaluation of all major organs and physiological systems were conducted preoperatively and postoperatively at 12 weeks post-infarction. All data are summarized in Table E1. The mean post MCARD-AAV9/SERCA2a serological values at 12 weeks were generally within normal limits. In particular, levels of creatinine, blood urea nitrogen, alanine aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, and total bilirubin remained well within the reference ranges.

Electrocardiographic assessment at 12 weeks after infarct showed that the QRS interval was significantly lengthened at 12 weeks in the control group, whereas the MCARD group maintained baseline levels (60±15 vs. 34±4ms, p<0.05). The PQ interval, QT interval, and heart rate were unaffected by treatment. As expected the ST segments were significantly elevated after infarct creation, and at 12 weeks remained slightly perturbed (Table E2). No arrhythmias were detected in either group.

Immune response to AAV9 and SERCA2a transgene

T cell immune response to AAV9 and SERCA2a transgene was evaluated by IFN-γ ELISPOT assay at selected time points. None of the MCARD-AAV9/SERCA2a animals had evidence of a T-cell mediated immune response to AAV9 capsid or to human SERCA2a at any of the timepoints tested in all animals (Fig. 5). The presence of preexisting antibodies is an important barrier to gene therapy as it strongly impacts transgene expression. Therefore, the animals were prescreened for the presence of NAbs against the administered AAV9. AAV9 neutralizing antibody levels at baseline in animals who had not previously received AAV9 vector were non-detectable by ELISA, meaning all showed corresponding titers below 1:5. The 6 MCARD animals that received rAAV9 vector had increases in NAb titers >1/120 against AAV9 at 9 and 12 weeks after MCARD procedure.

Figure 5.

Time course of transgene specific T cell responses to pools of AAV9 capsid peptides and pools of SERCA2a transgene in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) after administration ofAAV9/SERCA2a. SFU - Number of IFN-γ spot-forming units in ELISPOT assay of LV tissue samples. No stim: negative control. PMA+ION: positive control. Red line: positive result threshold. A, B, C and D each refer to a specific animal in the MCARD-AAV9/SERCA2a group.

Discussion

Consistent coronary arterial anatomy in sheep, similar to that of humans, and a lack of collateral vessels provides substantial advantages for creation of a clinically relevant ischemic cardiomyopathy model with a predictable myocardial infarct size in this species16. This physiologically appropriate large-animal model, involving ligation of the circumflex artery’s first two branches, is accompanied by almost zero mortality and is highly suitable for demonstrating ventricular remodeling after gene therapy.

In this study we confirmed our previous efficacy claims by showing that MCARD delivery of AAV9/SERCA2a results in robust expression in the lateral and anterior walls of the LV with an almost 100-fold higher level of expression than in the liver. MRI analysis shows the favorable effects of SERCA2a expression through improved global and regional cardiac mechanics and the substantial arrest of remodeling.

Post infarction remodeling is usually divided into early and late phases. The early phase involves expansion of the infarct zone. Late remodeling is caused in part by failure to normalize increases in wall stress and is associated with time-dependent progressive LV dilatation, distortion of ventricular shape, deterioration of contractile function and myocyte hypertrophy. Alterations to myocyte architecture initially stabilize the distending forces and prevent further ventricular deformation but are associated with increased energy consumption. Studies have indicated that in the healthy heart the mitochondrial function and structure match the maximal energy demand, but in a failing myocardium there is energy/demand mismatch17. As expected, we found through histological analysis that there is loss of mitochondrial density in the control group, while MCARD/SERCA2a treatment prevents mitochondrial loss thereby preserving high aerobic capacity of the muscle tissue. In fact, the decrease in mitochondrial density is proportionally greater than the decrease in fractional volume, suggesting evidence of maladaptive mitochondrial swelling in the control group. Indeed, morphometric analysis of electron microscopic images in our study show that the number of mitochondria per myocyte decrease and the volume of individual mitochondria increase in the controls but not in the treatment group. Reduction in the number of mitochondria is probably explained by the activation of pro-apoptotic pathways in HF and the relative increase in mitochondrial volume (swelling) is a failed compensatory response.

It is accepted that oxidative stress is caused by an imbalance between the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and antioxidant defense mechanisms, and is an important regulator of cardiac remodeling18. In contrast to the direct actions on cellular injury, ROS also play an important role in cell protection by the activation and expression of antioxidant enzymes19. Among biological processes, the level of lipid peroxidation is widely used as a biomarker of oxidative stress because lipids are most susceptible to ROS. Myocytes can accumulate ROS as a result of either increased numbers of total mitochondria producing ROS, or the production of higher levels of ROS by damaged mitochondria20. This may lead to the deterioration of cellular function and viability

Natural AAV infections or AAV gene therapy can cause the development of AAV neutralizing antibodies (NAbs) in animal species and humans. Pre-existing antibodies can modulate the efficacy of gene therapy by blocking vector transduction or by redirecting distribution of AAV vectors21. One of the most important aspects of the development of AAV for clinical gene therapy is the impact of the host humoral immune response against its capsid. No pre-existing AAV9 antibodies were found in any sheep in either group, but moderate titers were found in the treatment group after gene therapy. One strategy to overcome AAV NAbs in AAV-mediated gene therapy includes immunosuppression. It was demonstrated in a dog model that after LV intramyocardial injection of low dose 1011gc AAV6/SERCA2a all animals developed positive AAV-NAb titers >1/120. Immunosuppression commencing 4 weeks after AAV injection reduced NAb titers to baseline levels22. However, our finding of positive NAb titers 9 to 12 weeks after gene delivery is not unexpected and is will not affect efficacy given that this is a single dose therapy with no need for readministration.

Immune responses with activation of T cells directed against the viral capsid constitute an important safety concern in the use of AAV vectors. This response is dose dependent, and delivery 1012–1013 viral genomes (less than in our study) was associated with specific T-cells directed against the vector capsid23. Also, it is thought that capsid-directed T cell mediated cellular destruction was implicated in the observed toxicity in subjects of the high-dose group in the AAV2 clinical trial for the treatment of hemophilia24. In our study we found no positive T cell immune response in any sheep at any time point. This protective effect of MCARD is likely due to the closed-loop recirculation technique used to deliver the vector in a highly organ-specific fashion minimizing the exposure of antigen presenting cells to capsid antigens, an important and unique safety feature of the MCARD delivery platform.

This study demonstrates that MCARD delivery of a high dose of AAV9/SERCA2a is safe and efficacious with no toxic effect on major organ systems, no T cell mediated immune response, no increase in the prevalence of arrhythmias, decreased myocardial hypertrophy, improved mitochondrial ultrastructure, density and function. Finally, MCARD-mediated delivery of AAV9 expressing SERCA2a leads to markedly improved global LV function and significantly arrests maladaptive ventricular remodeling.

Study limitations

This study uses a relatively small number of animals due to the high cost and time demands of the study. A period of follow-up greater than 12 weeks would be desirable. We did not incorporate a control group with intracoronary delivery or an MCARD-null vector and other AAV serotypes because of the high time and material cost. Furthermore studies using AAV1 and AAV6 have been previously published5, and the inefficiency of intracoronary delivery – resulting in sequestration of over 99% of the injected vector in the liver is well documented3, 4.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH grant 1-R01 HL083078-01A2 (C.R.B.), and by the Charlotte Research Institute and UNC Charlotte Faculty Research Grant (I.M.S.). We would like to acknowledge the NHLBI Gene Therapy Resource Program (GTRP). We thank Dr. Roger J. Hajjar and Dr. Roberto Calcedo for helpful discussion. We would like to thank Haddit Godoy for imaging and analysis of myocyte cross-sectional area, Einar Heiberg for MRI software, Tracy L. Walling for histology, Daisy M. Ridings for electron microscopy and the staff of the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine of University of Pennsylvania for immunology. Further, we gratefully acknowledge the veterinarians and veterinary technicians for excellent care of the animals in the Cannon Research Center Vivarium.

TABLE E1.

Complete Blood Count and Blood Chemistry Summary

| Units | Reference range | Baseline | 12 Weeks | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complete blood count | ||||

| A. Hemoglobin | g/dL | 9–15 | 12.2 ± 0.5 | 8.4 ± 0.6 |

| B. Total WBC | 103/μL | 4–12 | 9.0 ± 0.7 | 9.0 ± 0.7 |

| C. Total RBC | 10^6/uL | 9.0–15.8 | 11.4 ± 0.4 | 8.4 ± 0.6 |

| D. Hematocrit | % | 27–45 | 33.0 ± 1.2 | 24.7 ± 1.5 |

| E. Platelet Count | 10^3/uL | 100–800 | 430 ± 71 | 415 ± 61 |

| F. Neutrophils | % | 10–50 | 30.8 ± 2.3 | 35.2 ± 4.7 |

| G. Lymphocytes | % | 40–75 | 64.2 ± 3.1 | 63.8 ± 4.9 |

| Renal system | ||||

| A. Urea Nitrogen | mg/dL | 10–35 | 14.0 ± 1.2 | 13.4 ± 1.7 |

| C. Sodium | mEq/L | 145–152 | 146.5 ± 1.1 | 141.4 ± 0.8 |

| D. Potassium | mEq/L | 3.4–5.5 | 5.5 ± 0.3 | 4.7 ± 0.1 |

| B. Creatinine | mg/dL | 0.2–1.9 | 0.70 ± 0.06 | 0.64 ± 0.08 |

| Gastrointestinal system | ||||

| A. Liver function | ||||

| 1. Alanine Aminotransferase | U/L | 22–38 | 16.2 ± 1.4 | 29.0 ± 5.2 |

| 2. Alkaline Phosphatase | U/L | 70–390 | 180 ± 27 | 76 ± 11 |

| 3. Total Bilirubin | mg/dL | 0.1–0.5 | 0.18 ± 0.03 | 0.34 ± 0.05 |

| 4. Albumin | g/dL | 2.4–4.0 | 3.17 ± 0.08 | 2.21 ± 0.15 |

| B. Pancreatic function | ||||

| 1. Lipase | U/L | 5–35 | 15.0 ± 2.3 | 10.0 ± 8.0 |

| 2. Amylase | U/L | 22–35 | 13.2 ± 2.5 | 10.7 ± 1.4 |

| 3. Glucose | mg/dL | 50–80 | 62.3 ± 3.5 | 74.0 ± 3.1 |

TABLE E2.

Electrocardiogram Segment Analysis Summary

| Units | Baseline | Post-Acute MI | MCARD- SERCA2a 12 Week | Control-No Treatment 12 Week | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PQ interval | ms | 124 ± 8 | 136 ± 10 | 133 ± 17 | 126 ± 16 |

| QRS interval | ms | 32 ± 4 | 21 ± 7 | 34 ± 4 | 60 ± 15 |

| QT interval | ms | 305 ± 23 | 343 ± 25 | 339 ± 37 | 348 ± 17 |

| ST deviation | μV | −37.5 ± 14 | 346 ± 80 | 33 ± 17 | 27 ± 10 |

| Heart Rate | bpm | 113 ± 13 | 103 ± 17 | 100 ± 16 | 96 ± 7 |

Footnotes

No related disclosures or conflicts of interest to report

Presented at the 94-th Annual Meeting of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, Toronto, ON, Canada, April 26–30, 2014.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lee R, Homer N, Andrei AC, McGee EC, Malaisrie SC, Kansal P, McCarthy PM. Early readmission for congestive heart failure predicts late mortality after cardiac surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;144:671–676. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jessup M, Greenberg B, Mancini D, Cappola T, Pauly DF, Jaski B, Yaroshinsky A, Zsebo KM, Dittrich H, Hajjar RJ. Calcium Upregulation by Percutaneous Administration of Gene Therapy in Cardiac Disease (CUPID): a phase 2 trial of intracoronary gene therapy of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase in patients with advanced heart failure. Circulation. 2011;124:304–313. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.022889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Byrne MJ, Power JM, Preovolos A, Mariani JA, Hajjar RJ, Kaye DM. Recirculating cardiac delivery of AAV2/1SERCA2a improves myocardial function in an experimental model of heart failure in large animals. Gene Ther. 2008;15:1550–1557. doi: 10.1038/gt.2008.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bridges CR. ‘Recirculating cardiac delivery’ method of gene delivery should be called ‘non-recirculating’ method. Gene Ther. 2009;16:939–940. doi: 10.1038/gt.2009.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fargnoli AS, Katz MG, Yarnall C, Isidro A, Petrov M, Steuerwald N, Ghosh S, Richardville KC, Hillesheim R, Williams RD, Kohlbrenner E, Stedman HH, Hajjar RJ, Bridges CR. Cardiac surgical delivery of the sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase rescues myocytes in ischemic heart failure. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96:586–595. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beeri R, Chaput M, Guerrero JL, Kawase Y, Yosefy C, Abedat S, Karakikes I, Morel C, Tisosky A, Sullivan S, Handschumacher MD, Gilon D, Vlahakes GJ, Hajjar RJ, Levine RA. Gene delivery of sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase inhibits ventricular remodeling in ischemic mitral regurgitation. Circ Heart Fail. 2010;3:627–634. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.891184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.del Monte F, Lebeche D, Guerrero JL, Tsuji T, Doye AA, Gwathmey JK, Hajjar RJ. Abrogation of ventricular arrhythmias in a model of ischemia and reperfusion by targeting myocardial calcium cycling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:5622–5627. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305778101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen Y, Escoubet B, Prunier F, Amour J, Simonides WS, Vivien B, Lenoir C, Heimburger M, Choqueux C, Gellen B, Riou B, Michel JB, Franz WM, Mercadier JJ. Constitutive cardiac overexpression of sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase delays myocardial failure after myocardial infarction in rats at a cost of increased acute arrhythmias. Circulation. 2004;109:1898–1903. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000124230.60028.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katz MG, Fargnoli AS, Swain JD, Tomasulo CE, Ciccarelli M, Huang ZM, Rabinowitz JE, Bridges CR. AAV6-betaARKct gene delivery mediated by molecular cardiac surgery with recirculating delivery (MCARD) in sheep results in robust gene expression and increased adrenergic reserve. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;143:720–726. e723. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.08.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pacak CA, Mah CS, Thattaliyath BD, Conlon TJ, Lewis MA, Cloutier DE, Zolotukhin I, Tarantal AF, Byrne BJ. Recombinant adeno-associated virus serotype 9 leads to preferential cardiac transduction in vivo. Circ Res. 2006;99:e3–9. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000237661.18885.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bish LT, Morine K, Sleeper MM, Sanmiguel J, Wu D, Gao G, Wilson JM, Sweeney HL. Adeno-associated virus (AAV) serotype 9 provides global cardiac gene transfer superior to AAV1, AAV6, AAV7, and AAV8 in the mouse and rat. Hum Gene Ther. 2008;19:1359–1368. doi: 10.1089/hum.2008.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen J, Wu Q, Yang P, Hsu HC, Mountz JD. Determination of specific CD4 and CD8 T cell epitopes after AAV2- and AAV8-hF.IX gene therapy. Mol Ther. 2006;13:260–269. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cherkasov AS, Biswas PK, Ridings DM, Ringwood AH, Sokolova IM. Effects of acclimation temperature and cadmium exposure on cellular energy budgets in the marine mollusk Crassostrea virginica: linking cellular and mitochondrial responses. J Exp Biol. 2006;209:1274–1284. doi: 10.1242/jeb.02093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Calcedo R, Vandenberghe LH, Roy S, Somanathan S, Wang L, Wilson JM. Host immune responses to chronic adenovirus infections in human and nonhuman primates. J Virol. 2009;83:2623–2631. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02160-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Biagini E, Galema TW, Schinkel AF, Vletter WB, Roelandt JR, Ten Cate FJ. Myocardial wall thickness predicts recovery of contractile function after primary coronary intervention for acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:1489–1493. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gorman JH, 3rd, Gorman RC, Plappert T, Jackson BM, Hiramatsu Y, St John-Sutton MG, Edmunds LH., Jr Infarct size and location determine development of mitral regurgitation in the sheep model. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1998;115:615–622. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(98)70326-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goffart S, von Kleist-Retzow JC, Wiesner RJ. Regulation of mitochondrial proliferation in the heart: power-plant failure contributes to cardiac failure in hypertrophy. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;64:198–207. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dominguez-Rodriguez A, Abreu-Gonzalez P, de la Rosa A, Vargas M, Ferrer J, Garcia M. Role of endogenous interleukin-10 production and lipid peroxidation in patients with acute myocardial infarction treated with primary percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty, interleukin-10 and primary angioplasty. Int J Cardiol. 2005;99:77–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2003.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hori M, Nishida K. Oxidative stress and left ventricular remodelling after myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;81:457–464. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sena LA, Chandel NS. Physiological roles of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Mol Cell. 2012;48:158–167. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Calcedo R, Wilson JM. Humoral Immune Response to AAV. Front Immunol. 2013;4:341. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhu X, McTiernan CF, Rajagopalan N, Shah H, Fischer D, Toyoda Y, et al. Immunosuppression decreases inflammation and increases AAV6-hSERCA2a-mediated SERCA2a expression. Hum Gene Ther. 2012;23:722–732. doi: 10.1089/hum.2011.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mingozzi F, High KA. Immune responses to AAV vectors: overcoming barriers to successful gene therapy. Blood. 2013;122:23–36. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-01-306647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manno CS, Pierce GF, Arruda VR, Glader B, Ragni M, Rasko JJ, Ozelo MC, Hoots K, Blatt P, Konkle B, Dake M, Kaye R, Razavi M, Zajko A, Zehnder J, Rustagi PK, Nakai H, Chew A, Leonard D, Wright JF, Lessard RR, Sommer JM, Tigges M, Sabatino D, Luk A, Jiang H, Mingozzi F, Couto L, Ertl HC, High KA, Kay MA. Successful transduction of liver in hemophilia by AAV-Factor IX and limitations imposed by the host immune response. Nat Med. 2006;12:342–347. doi: 10.1038/nm1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]