Abstract

Background

The aim of this meta-analysis was to compare the outcomes of proximal femoral nail (PFN) and dynamic hip screw (DHS) in treatment of intertrochanteric fractures.

Material/Methods

Relevant randomized or quasi-randomized controlled studies comparing the effects of PFN and DHS were searched for following the requirements of the Cochrane Library Handbook. Six eligible studies involving 669 fractures were included. Their methodological quality was assessed and data were extracted independently for meta-analysis.

Results

The results showed that the PFN group had significantly less operative time (WMD: −21.15, 95% CI: −34.91 – −7.39, P=0.003), intraoperative blood loss (WMD: −139.81, 95% CI: −210.39 – −69.22, P=0.0001), and length of incision (WMD: −6.97, 95% CI: −9.19 – −4.74, P<0.00001) than the DHS group. No significant differences were found between the 2 groups regarding postoperative infection rate, lag screw cut-out rate, or reoperation rate.

Conclusions

The current evidence indicates that PFN may be a better choice than DHS in the treatment of intertrochanteric fractures.

MeSH Keywords: Bone Screws, Hip Fractures, Meta-Analysis as Topic

Background

The incidence of intertrochanteric fractures has been increasing significantly due to the rising age of modern human populations [1,2]. Generally, intramedullary fixation and extramedullary fixation are the 2 primary options for treatment of such fractures. The dynamic hip screw (DHS), commonly used in extramedullary fixation, has become a standard implant in treatment of these fractures [3,4]. Proximal femoral nail (PFN) and Gamma nail are 2 commonly used devices in the intramedullary fixation. Previous studies showed that the Gamma nail did not perform as well as DHS because it led to a relatively higher incidence of post-operative femoral shaft fracture [5,6].

PFN, introduced by the AO/ASIF group in 1997, has become prevalent in treatment of intertrochanteric fractures in recent years because it was improved by addition of an antirotation hip screw proximal to the main lag screw. However, both benefits and technical failures of PFN have been reported [7–9]

Although the effects of PFN and DHS in treatment of intertrochanteric fractures have been reported, the results and conclusions are not consistent [10–15]. Therefore, we conducted this meta-analysis to investigate whether there is a significant difference between PFN and DHS fixation in treatment of intertrochanteric fractures.

Our aim was to evaluate clinical results comparing PFN with DHS, including comparison of operative time, intraoperative blood loss, length of incision, postoperative infection rate, lag screw cut-out rate, and reoperation rate. We hypothesized that PFN would be a superior treatment for intertrochanteric fractures compared with DHS.

Material and Methods

We searched for randomized or quasi-randomized controlled studies comparing the effects of PFN and DHS according to the search strategy of the Cochrane Collaboration. It included searching of the Cochrane Musculoskeletal Injuries Group Trials Register, computer searching of MEDLINE, EMBASE, and Current Contents, and hand searching of orthopedic journals. All databases were searched from the earliest records to August 2012. The inclusion and exclusion criteria used in selecting eligible studies were: (1) target population – individuals with intertrochanteric fractures, excluding subtrochanteric and pathological fractures; (2) intervention – DHS fixation compared with PFN fixation; (3) methodological criteria – prospective, randomized, or quasi-randomized controlled trials; (4) duplicate or multiple publications of the same study were not included.

Data were collected by 2 independent researchers who screened titles, abstracts, and keywords both electronically and by hand; differences were resolved by discussion. Full texts of citations that could possibly be included in the present meta-analysis were retrieved for further analysis. The assessment method from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions was used to evaluate the studies in terms of blinding, allocation concealment, follow-up coverage, and quality level. The study quality was assessed according to whether allocation concealment was: adequate (A), unclear (B), inadequate (C), or not used (D). Operative time (min), intraoperative blood loss (ml), length of incision, post-operative infection, lag screw cut-out rate, and reoperation rate were the main measures in the studies included, which the present meta-analysis evaluated to compare the effects of PFN and DHS. We did not undertake a subgroup analysis for different fracture types because not all of the studies included described the fracture types.

In each eligible study the relative risk (RR) was calculated for dichotomous outcomes and the weighted mean difference for continuous outcomes using the software Review Manager 5.0, with a 95% confidence interval (CI) adopted in both. Heterogeneity was tested using both the chi-square test and the I-square test. A significance level of less than 0.10 for the chi-square test was interpreted as evidence of heterogeneity. The I-square was used to estimate total variation across studies. When there was no statistical evidence of heterogeneity, a fixed-effect model was adopted; otherwise, a random-effect model was chosen. We did not include the possibility of publishing bias due to the small number of studies included.

Results

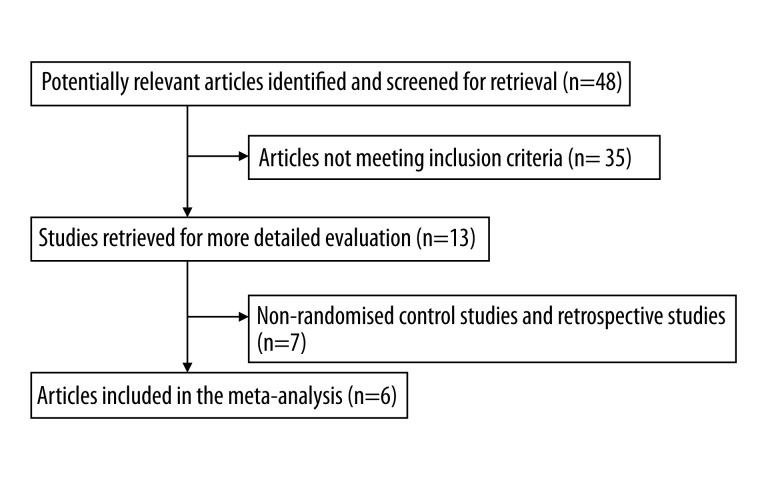

A total of 48 articles comparing PFN and DHS that had been published from 1969 to August 2012 were retrieved: 37 were from MEDLINE, 6 from the Cochrane Library, and 5 from the EMBASE Library. Among them, 13 trials met the inclusion criteria. After excluding non-randomized control trials and retrospective articles, 6 randomized and quasi-randomized controlled trials [10–15] were included (Figure 1). The number of fractures included in a single study ranged from 64 to 206. There were a total of 669 fractures. Three research papers targeted Asian patients, and the other 3 targeted Caucasians. All studies except 1 had more female than male patients; 308 fractures were managed with PFN and 361 managed with DHS. The quality of the 6 studies included was level B because the allocation concealment was unclear according to the evaluation criteria mentioned above (Tables 1 and 2).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study search and selection for the meta-analysis.

Table 1.

Description of the studies included in the meta-analysis.

| Studies | Age (years): PFN/DHS | Men (%) | Target population | Length of follow-up | Number of fractures | Outcomes* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFN | DHS | ||||||

| Saudan et al. [10] | 83±9.7/83.7±10.1 | 22.3 | Switzerland | 12 months | 100 | 100 | 1, 4, 5, 6 |

| PAN et al. [12] | 70±6.8/69±7.11 | 73 | Asia | 16 months | 30 | 34 | 1, 2, 3, 4 |

| Papasimos et al. [13] | 79.4/81.4 | 38.6 | Greece | 12 months | 40 | 40 | 4, 5, 6 |

| Pajarinen et al. [11] | 80.9±9.1/80.3±10.8 | 25 | Finland | 4 months | 54 | 54 | 2, 4, 5, 6 |

| Shen et al. [14] | 72.1±6.61/71.2±7.11 | 40.2 | Asia | 16 months | 51 | 56 | 1, 2, 4 |

| ZHAO et al. [15] | 76 (63–87)/74.5 (61–92) | 40.4 | Asia | 19 months | 33 | 71 | 1, 2, 3, 5 |

1 – operative time; 2 – intraoperative blood loss; 3 – length of incision; 4 – postoperative infection rate; 5 – lag screw cut-out rate; 6 – reoperation rate.

Table 2.

Methodological quality of studies included.

| Studies | Baseline | Randomisation | Allocation concealment | Blinding | Loss to follow-up | Level | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Sex | Fracture type | ||||||

| Saudan et al. [10] | Comparable | Comparable | Incomparable | Inadequate | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | B |

| PAN et al. [12] | Comparable | Comparable | Comparable | Inadequate | Unclear | Unclear | Not reported | B |

| Papasimos et al. [13] | Comparable | Comparable | Comparable | Adequate | Unclear | Unclear | None | B |

| Pajarinen et al. [11] | Comparable | Comparable | Comparable | Inadequate | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | B |

| Shen et al. [14] | Comparable | Comparable | Incomparable | Inadequate | Unclear | Unclear | None | B |

| ZHAO et al. [15] | Comparable | Comparable | Comparable | Inadequate | Unclear | Unclear | None | B |

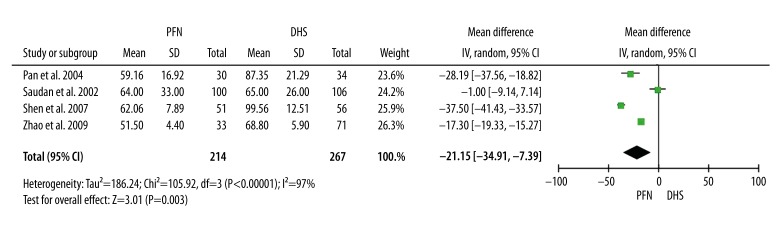

Operative time

Four studies [10,12,14,15] provided data on operative time. The random-effects model was used because of the statistical heterogeneity (I2=97%). The meta-analysis indicated that the operative time for the PFN group was significantly shorter than for the DHS group (WMD: −21.15, 95% CI: −34.91 – −7.39, P=0.003) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Operative time.

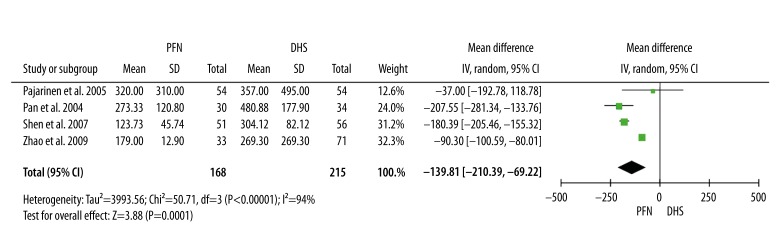

Intraoperative blood loss

Four studies [11,12,14,15] provided data on intraoperative blood loss. The random-effects model was used because of the statistical heterogeneity (I2=94%). The meta-analysis indicated that the intraoperative blood loss for the PFN group was significantly less than for the DHS group (WMD: −139.81, 95% CI: −210.39 – −69.22, P=0.0001) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Intraoperative blood loss.

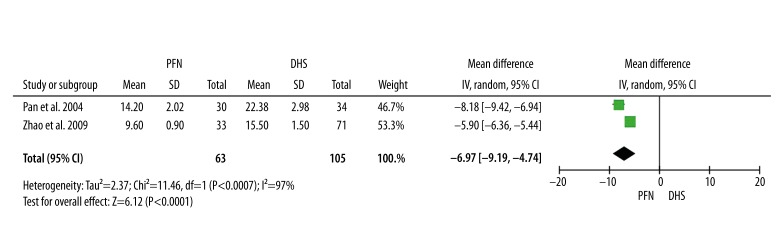

Length of incision

Two studies [12,15] provided data on length of incision. The random-effects model was used because of the statistical heterogeneity (I2=91%). The meta-analysis indicated that the length of incision in the PFN group was significantly shorter than in the DHS group (WMD: −6.97, 95% CI: −9.19 – −4.74, P<0.00001) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Length of incision.

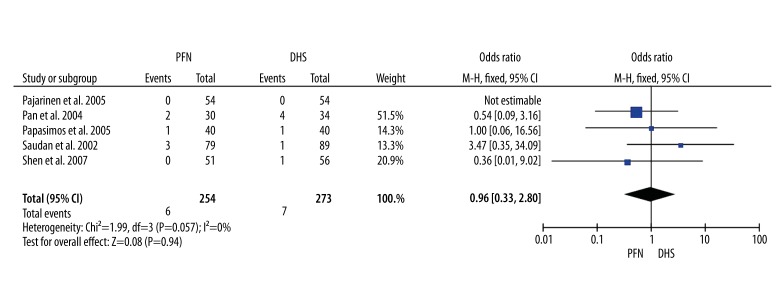

Postoperative infection rate

Five studies [10–14] provided data on postoperative infection rate. Postoperative infection was observed in 6 of the 254 fractures managed with PFN, and in 7 of the 273 fractures managed with DHS. Heterogeneity tests indicated no statistical evidence of heterogeneity (I2=0%). Data pooled by a fixed-effects model and the meta-analysis indicated an insignificantly higher rate of postoperative infection in the DHS group (RR: 0.96, 95% CI: 0.33–2.8, P=0.94) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Postoperative infection rate.

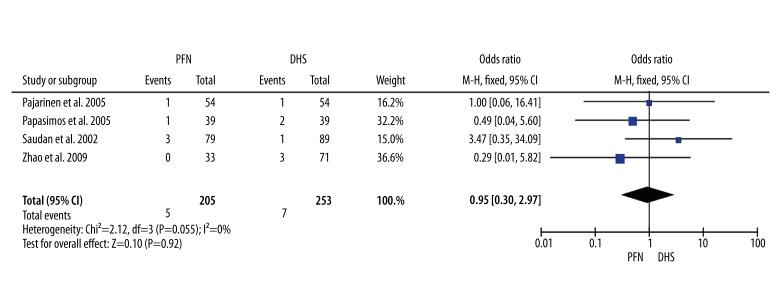

Lag screw cut-out rate

Four studies [10,11,13,15] provided data on lag screw cut-out rate. Lag screw cut-out was observed in 5 of the 205 fractures managed with PFN and in 7 of the 253 fractures managed with DHS. Heterogeneity tests indicated no statistical evidence of heterogeneity (I2=0%). Data pooled by a fixed-effects model and the meta-analysis indicated an insignificantly higher rate of lag screw cut-out in the DHS group (RR: 0.95, 95% CI: 0.30–2.97, P=0.92) (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Lag screw cut-out rate.

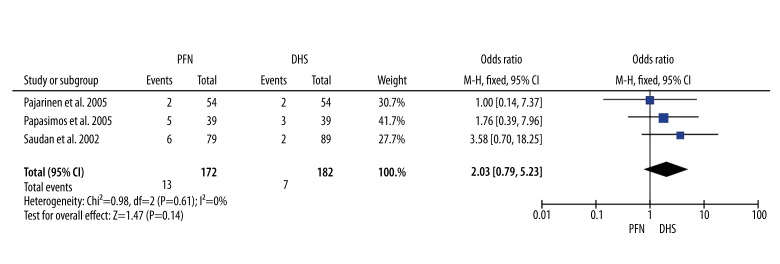

Reoperation rate

Three studies [10,11,13] provided data on reoperation rate. Reoperation was needed in 13 of the 172 fractures managed with PFN and in 7 of the 182 fractures managed with DHS. Heterogeneity tests indicated no statistical evidence of heterogeneity (I2=0%). Data pooled by a fixed-effects model and the meta-analysis indicated an insignificantly higher rate of reoperation in the PFN group (RR: 2.03, 95% CI: 0.79–5.23, P=0.14) (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Reoperation rate.

Discussion

The varus collapse of the head and neck caused by lag screw cut-out or lateral protrusion is one of most common post-operative complications that lead to surgical failure in treatment of intertrochanteric fractures. The cut-out (including ‘Z’ effect) rates were about 3–10% in PFN and DHS [16,17].

Most studies reported that lag screw position might be associated with the rate of cut-out in DHS fixation. Cut-out was thought to be caused either by improper lag screw placement in the anterior superior quadrant of the head or by not placing the screw close enough to the subchondral region of the head [18]. Baumgaertner et al. showed that a small tip apex distance (TAD) – less than 25 mm – was associated with a lower probability for cutout. Their conclusion was widely accepted by most surgeons [18–20]. Another explanation for cut-out is that because the screw is rotationally unstable within the bone when a single lag screw is used, flexion-extension of the limb results in loosening of the bone screw interface, leading to the secondary cut-out of the screw.

In 1997, PFN was introduced for treatment of intertrochanteric fractures. It was designed to overcome implant-related complications and facilitate the surgical treatment of unstable intertrochanteric fractures [21]. PFN uses 2 implant screws for fixation into the femoral head and neck. The larger femoral neck screw is intended to carry most of the load. The smaller hip pin is inserted to provide rotational stability. Biomechanical analysis of PFN showed a significant reduction of distal stress and an increase in overall stability compared with the Gamma nail [22]. Despite the mechanical advantages of PFN, lag screw cut-out remains a significant problem, especially in the more unstable fractures. This meta-analysis also found a higher rate of lag screw cut-out in the DHS group, though it was not statistically significant. This indicates that the anti-rotation screw of the PFN may not be beneficial enough. However, Herman et al. showed that the mechanical failure rate increased from 4.8% to 34.4% when the centre of the lag screw was not in the second quarter of the head-neck interface line (the so-called “safe zone”) (p=0.001) and that the lag screw insertions lower or higher than the head apex line by 11 mm were associated with failure rates of 5.5% and 18.6%, respectively (p=0.004) [23]. They suggested that placing the lag screw within the “safe zone” could significantly reduce the mechanical failure rate when PFN was used to treat intertrochanteric fractures [23].

PFN, inserted by means of a minimally invasive procedure, allows surgeons to minimize soft tissue dissection, thereby reducing surgical trauma and blood loss. The results of this meta-analysis also demonstrates that operative time, intraoperative blood loss, and length of incision in the PFN group are significantly less than in the DHS group. Therefore, because of its minimal invasiveness, we recommend PFN as a better choice than DHS in the treatment of elderly patients with intertrochanteric fracture.

There are several limitations in our meta-analysis. Firstly, the number of studies included and the sample size of patients were quite limited. In addition, the 6 studies were of relatively poor quality (Level B), which might weaken the strength of the findings. Secondly, we did not undertake a subgroup analysis of different fracture types because not all the studies included described the fracture types. Furthermore, not all the studies included had long enough follow-up periods, which also reduces the power of our research.

Conclusions

In summary, the current available data indicate that PFN may be a better choice than DHS in the treatment of intertrochanteric fractures.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the advice and assistance of Prof. Ping Liang.

Footnotes

Source of support: Departmental sources

References

- 1.Cummings SR, Rubin SM, Black D. The future of hip fractures in the United States. Numbers, costs, and potential effects of postmenopausal estrogen. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;252:163–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kannus P, Parkkari J, Sievänen H, et al. Epidemiology of hip fractures. Bone. 1996;18(Suppl 1):57–63. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(95)00381-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bridle SH, Patel AD, Bircher M, Calvert PT. Fixation of intertrochanteric fractures of the femur. A randomized prospective comparison of the gamma nail and the dynamic hip screw. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1991;73(2):330–34. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.73B2.2005167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Radford PJ, Needoff M, Webb JK. Aprospective randomised comparison of the dynamic hip screw and the gamma locking nail. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1993;75(5):789–93. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.75B5.8376441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Butt MS, Krikler SJ, Nafie S, Ali MS. Comparison of dynamic hip screw and gamma nail: a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Injury. 1995;9:615–18. doi: 10.1016/0020-1383(95)00126-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saarenpää I, Heikkinen T, Ristiniemi J, et al. Functional comparison of the dynamic hip screw and the Gamma locking nail in trochanteric hip fractures: a matched-pair study of 268 patients. Int Orthop. 2009;33(1):255–60. doi: 10.1007/s00264-007-0458-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nuber S, Schönweiss T, Rüter A. Stabilisation of unstable trochanteric femoral fractures. Dynamic hip screw (DHS) with trochanteric stabilisation plate vs. proximal femur nail (PFN) Unfallchirurg. 2003;106(1):39–47. doi: 10.1007/s00113-002-0476-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boldin C, Seibert FJ, Fankhauser F, et al. The proximal femoral nail (PFN): a minimal invasive treatment of unstable proximal femoral fractures: a prospective study of 55 patients with a follow-up of 15 months. Acta Orthop Scand. 2003;74(1):53–58. doi: 10.1080/00016470310013662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pires RE, Santana EO, Jr, Santos LE, et al. Failure of fixation of trochanteric femur fractures: clinical recommendations for avoiding Z-efect and reverse Z-efect type complications. Patient Saf Surg. 2011;22:17. doi: 10.1186/1754-9493-5-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saudan M, Lübbeke A, Sadowski C, et al. Pertrochanteric fractures: is there an advantage to an intramedullary nail?: a randomized, prospective study of 206 patients comparing the dynamic hip screw and proximal femoral nail. J Orthop Trauma. 2002;16:386–93. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200207000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pajarinen J, Lindahl J, Michelsson O, et al. Pertrochanteric femoral fractures treated with a dynamic hip screw or a proximal femoral nail: a randomised study comparing postoperative rehabilitation. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87:76–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pan X-h, Xiao D-m, Lin B-w. Dynamic hip screws (DHS) and proximal femoral nails (PFN) in treatment of intertrochanteric fractures of femur in elderly patients. Chin J Orthop Trauma. 2004;7:785–89. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Papasimos S, Koutsojannis CM, Panagopoulos A, et al. A randomised comparison of AMBI, TGN and PFN for treatment of unstable trochanteric fractures. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2005;125:462–68. doi: 10.1007/s00402-005-0021-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shen H-m, Liang C-w, Fan Y-q. The Clinical Study of the Treatment of Intertrochanteric Fractures in the Elderly with DHS, Gamma nail and PFN. Chinese Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2007;2:226–28. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao C, Liu D-y, Guo J-j. Comparison of proximal femoral nail and dynamic hip screw for treating intertrochanteric fractures. China J Orthop & Trauma. 2009;7:535–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parker MJ, Pryor GA. Gamma versus DHS nailing for extracapsular femoral fractures. Meta-analysis of ten randomised trials. Int Orthop. 1996;20:163–68. doi: 10.1007/s002640050055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schipper IB, Steyerberg EW, Castelein RM, et al. Treatment of unstable trochanteric fractures. Randomised comparison of the gamma nail and the proximal femoral nail. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86:86–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baumgaertner MR, Solberg BD. Awareness of tip-apex distance reduces failure of fixation of trochanteric fractures of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1997;79:969–71. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.79b6.7949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goffin JM, Pankaj P, Simpson AH. The importance of lag screw position for the stabilization of trochanteric fractures with a sliding hip screw: A subject-specific finite element study. J Orthop Res. 2013;31:596–600. doi: 10.1002/jor.22266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Verhofstad MH, van der Werken C. DHS osteosynthesis for stable pertrochanteric femur fractures with a two-hole side plate. Injury. 2004;35:999–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2003.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simmermacher RK, Bosch AM, Van der Werken C. The AO/ASIF-proximal femoral nail (PFN): A new device for the treatment of unstable proximal femoral fractures. Injury. 1999;30:327–32. doi: 10.1016/s0020-1383(99)00091-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Götze B, Bonnaire F, Weise K, Friedl HP. Belast-bahrkeit von Osteosynthesen bei instabilen per-und subtrochanteren Femurfrakturen. Aktuelle Traumatol. 1998;28:197–204. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Herman A, Landau Y, Gutman G, et al. Radiological evaluation of intertrochanteric fracture fixation by the proximal femoral nail. Injury. 2012;43:856–63. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2011.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]