Abstract

Because homelessness assistance programs are designed to help families, it is important for policymakers and practitioners to understand how families experiencing homelessness make housing decisions, particularly when they decide not to use available services. This study explores those decisions using in-depth qualitative interviews with 80 families recruited in shelters across four sites approximately six months after they were assigned to one of four conditions (permanent housing subsidies, project-based transitional housing, community-based rapid re-housing, and usual care). Familiar neighborhoods near children’s schools, transportation, family and friends, and stability were important to families across conditions. Program restrictions on eligibility constrained family choices. Subsidized housing was the most desired intervention and families leased up at higher rates than in other studies of poor families. Respondents were least comfortable in and most likely to leave transitional housing. Uncertainty associated with community-based rapid re-housing generated considerable anxiety. Across interventions, many families had to make unhappy compromises, often leading to further moves. Policy recommendations are offered.

Keywords: Homelessness, Housing decisions, Housing subsidies, Rapid re-housing, Transitional housing, Housing assistance programs

On a single night in January 2012, over 600,000 people in the United States were homeless, including 239,403 who were homeless as part of a family (Cortes, Henry, de la Cruz, & Brown, 2012). Families experiencing homelessness confront a complex array of choices regarding housing, and must consider needs of both parents and children in the context of severe resource constraints. Homelessness assistance programs provide various forms of help, including a place to stay or help with paying rent, which are sometimes linked to required or optional social services. Families do not always pursue these options, and some of those who receive an offer of housing assistance or services elect not to use it; it remains unclear why. This study examines uses qualitative interviews to examine homeless families’ housing decisions and what makes particular options more and less attractive to them.

Shelter and Housing Assistance

Five types of federally funded shelter or housing assistance programs are potentially useful to homeless families: emergency shelters, transitional housing programs, permanent supportive housing, permanent subsidies, and temporary subsidies to promote rapid exit from shelter. Emergency shelters are typically the entry point to the homeless service system. They provide families a temporary place to stay, often in congregate settings. Many shelter systems provide supportive services to help families move on to more permanent forms of housing. A few communities have a “right to shelter” and attempt to house all families who are homeless; many have limited capacity and must turn some families away, or limit lengths of stay (Gilderbloom, Squires, & Wuerstle, 2013; Rossi, 1989). Families in the present study were recruited in shelters, and we examine their housing decisions after that point.

Transitional housing programs offer subsidized housing, case management, and supportive services for a period of up to two years. Transitional housing can be scattered throughout a community or project-based in a central location with services located on site. Some scattered-site transitional housing allows families to transition in place, that is, to assume the lease for the unit they are occupying at the end of the program. In project-based transitional housing (PBTH), families must leave and find housing elsewhere.

Permanent supportive housing provides families with social services on an ongoing basis in subsidized housing. Permanent supportive housing has been used successfully for single adults and families with mental illnesses and other disabilities. Because most families who experience homelessness have only one, relatively short-term episode of shelter use and then do not return to the homeless service system (Culhane, Metraux, Park, Schretzman, & Valente 2007), few seem to need such an expensive, intensive intervention to maintain housing in the community. We do not examine these programs in the present study.

Federally-funded permanent housing subsidies without specialized services are provided in a variety of ways: by public housing authorities in facilities they own and operate, via project-based rent subsidies tied to particular properties, or through Housing Choice Vouchers or similar programs that families use to rent market housing in the community. Subsidies are renewable, as long as the family remains eligible, and reduce families’ costs for rent and utilities to approximately 30% of their income. Most permanent housing programs have long waiting lists, so that subsidies are rarely offered to families at the time they experience homelessness. However, studies have shown that permanent subsidies effectively prevent poor families from becoming homeless (Wood, Turnham, & Mills, 2008), prevent returns to shelter (Cragg & O’Flaherty, 1999; Wong, Culhane, & Kuhn, 1997), and help formerly homeless families to maintain long-term stability (Shinn, 1998).

The newest entry to the homeless services system is community-based rapid re-housing (CBRR), funded under the Homelessness Prevention and Rapid Re-housing Program (HPRP) as part of the American Reinvestment and Recovery Act of 2009, although based on earlier models implemented by some localities (Burt, The Urban Institute, Pearson, Montgomery, & Walter R. McDonald & Associates, 2005). CBRR provides short-term subsidies (for a maximum of 18 months with quarterly recertification of eligibility), with services focused on housing and self-sufficiency. The goal is to provide each homeless family or individual with the minimum level of assistance needed until they can pay market rent, so subsidies are individually structured and may be shallow as well as short-term. The program is consistent with the call by Culhane, Metraux, and Byrne (2011) for “progressive engagement,” where intensive interventions are reserved for families for whom shorter or less expensive interventions fail. During the first year of CBRR under HPRP, 94% of program recipients had permanent housing when they left the program, and most had a unit they rented themselves (HUD, 2010).

Research on Families’ Housing Decisions and Ability to Use Assistance

Most of the research about families’ use of housing subsidies concerns Housing Choice Vouchers and typically involves families who are not homeless at the time they are offered a voucher. At the time the voucher program was created in the mid-1970s, it was expected to be an open-enrollment program like food stamps, available to all households qualifying based on income and household type. At this time, there was major concern regarding whether families would be successful using their assistance–in particular, whether the requirement that a housing unit pass a quality inspection would depress participation in the program. In the experimental program that tested variants of the voucher concept, researchers found that only 38% of a sample of households in Pittsburgh and Phoenix who were offered the type of assistance that became Housing Choice Vouchers participated. Participation in a voucher program is a product of signing up for the program and succeeding in leasing a qualifying housing unit. Of those receiving an offer of enrollment in the program, about 79% accepted the offer, but only 47% of those households met the program’s standards and began to receive assistance (i.e., leased a qualifying unit) (Kennedy, 1980).

Several subsequent studies have estimated the “success rate” of the voucher program nationally or across a large sample of places. The success rate is the lease up rate among those who (a) get on the waiting lists maintained by administrators of voucher programs, (b) are found to qualify for assistance, and (c) are issued a voucher—analogous to the 47% in the previous paragraph. In the mid 1980s, the national success rate was 68%, climbing to 81% in 1993, and then dropping back to 69% in 2000 (Finkel & Buron, 2001). Studies conducted at a sub-national level have found similarly low success rates. In a demonstration of the impacts of housing vouchers for welfare families, 62% of families who had been issued vouchers in six cities leased up (Mills et al., 2006), and only 50% of Chicago families who were offered a voucher leased up (Jacob & Ludwig, 2012).

There is reason to believe that the voucher type of housing assistance is attractive to families even beyond the financial benefit of the subsidy. For example, a study of the use of housing vouchers by welfare families found that many used the subsidy to reduce crowded conditions, often moving out of larger households headed by relatives (Wood, Turnham, & Mills, 2008). Additionally, families using vouchers move to neighborhoods that are somewhat better in terms of safety and average income than those without vouchers (Feins & Patterson, 2005; Gubits, Khadduri, & Turnham, 2009; Lens, Ellen, & O’Regan, 2011; Wood, Turnham, & Mills, 2008).

Recent literature on the voucher program has focused on why vouchers have not always enabled families to move to better neighborhoods that subsidies should put within their reach (Basolo & Nguyen, 2005; Devine, Gray, Rubin, & Taghavi, 2003; Galvez, 2010). HUD’s Moving to Opportunity (MTO) demonstration required some families to move to neighborhoods with low poverty rates as a condition of using the voucher, but many families either did not use the assistance or did not remain in the low poverty locations in which they first leased units (Edin, De Luca, & Owens, 2012; Sanbonmatsu et al., 2011).

Landlords may present barriers to successful voucher use. When landlords in relatively affluent neighborhoods refuse to accept vouchers as part of the rent payment, this refusal may be a disguised form of discrimination against racial and ethnic minorities. A few states and localities have fair housing laws that prohibit discrimination on the basis of the source of income that will be used to pay rent, and most of the evidence of discrimination against voucher holders is based on court cases that have attempted to enforce those laws (Bacon, 2005; Beck, 1996; Daniel, 2010; Freeman, 2012; Johnson-Spratt, 1999; Sterken, 2009). As yet no study has systematically measured the extent of discrimination against families with vouchers in different types of neighborhoods or overall (Galvez, 2010). Nevertheless, racial and ethnic discrimination does not in itself explain low success rates, as success rates are not lower for minority households than they are for non-minorities (Finkel & Buron, 2001, Kennedy & Finkel, 1994). Finkel and Kennedy (1992) conclude that the voucher program operates primarily in racial and ethnically defined “submarkets,” with high success rates for minorities who attempt to lease in places where they are the dominant group.

Less is known about decisions to use transitional housing. Studies without comparison groups suggest that families who experience different configurations of housing subsidies (often permanent subsidies) linked to supportive services have good outcomes in areas such as housing stability, family preservation, employment and income (see Bassuk & Geller, 2006 for a review), but families frequently leave programs before they are required to do so. The 2011 Annual Homeless Assessment Report to Congress (HUD, 2012) notes that families stay in transitional housing for an average of 154 nights when measured over a single-year period, and very few are there during the entire year. Few stay for the full two-year period typically permitted (Burt, 2010; Spellman, Khadduri, Sokol, & Leopold, 2010). In some cases families may depart because they run afoul of program rules (Fogel, 1997). There may be a tradeoff, in which intensive service models that make restrictive demands on families yield shorter tenures but greater benefits for families who remain (Shinn, 2009). Even less is known about what motivates families to accept or decline an offer of transitional housing in the first place.

We were unable to find research on reasons families might accept, or fail to take up, offers of CBRR. While the HUD program under which CBRR was funded requires a housing quality inspection, the local agencies that administered the program were not public housing authorities (PHAs) and likely did not apply the quality standard as rigorously as the voucher program does. CBRR also differs from a housing voucher in being temporary. The only research to date on the use of temporary rental assistance relates to people with HIV/AIDs (Dasinger & Speiglman, 2007) and to hurricane victims (Buron & Locke, 2013). The assistance for hurricane victims did not have a work requirement, and most hurricane victims used the assistance for as long as they were permitted to do so.

Homeless families without offers of assistance beyond a stay in shelter also make housing decisions, often because of limits on their time in shelter. They frequently double up with others, or move from place to place, with stays in regular housing sometimes interspersed with returns to shelter (Spellman et al., 2010; Stojanovic, Weitzman, Shinn, Labay, & Williams, 1999). This is consistent with Rossi’s (1980) findings that families move in response to their changing needs. As needs change, families leave places for both “push” reasons (evictions, time limits on stays, or undesirable features of the places they are staying), as well as “pull” reasons (desirable features of other housing situations) while attempting to overcome any obstacles to their move (Lee, 1966).

Simon’s (1955; 1956) theory of bounded rational choice suggests that people rarely optimize by selecting the best option from an exhaustive buffet of options (as the traditional form of rational choice theory would suggest), but “satisfice” by making decisions that meet their highest priority needs and are satisfactory for the given time. Time constraints play an important role in decision-making, as people typically make decisions sequentially, without full knowledge of all available options. In addition, when people find it easy to discover satisfactory alternatives, their aspiration level rises; when it is difficult their aspiration level falls (Simon, 1955). The limited options afforded to families who are experiencing poverty and an instance of homelessness means that many of their goals may be mismatched with the options available to them; Simon’s theory of satisficing suggests that some of these goals will go unmet. In this study, we examine how homeless families make the housing decisions they do, with particular regard to those who choose not to take up an offer of housing assistance or stop using it before they must. Using qualitative interviews, we draw upon the words and experiences of parents to describe considerations that affect housing decisions of families experiencing homelessness, across and within offers of different types of housing assistance.

Methods

Participants in this study were drawn from a large-scale experiment comparing the effectiveness of housing and service options for families experiencing homelessness (see Gubits et al., 2013 for more information). Families were recruited from homeless shelters that typically had limits on lengths of stay (commonly about 90 days) and where they shared bathrooms and often kitchens and sleeping rooms with other families. The experiment randomized families to one of three offers of housing assistance: a permanent housing subsidy (SUB) usually provided by a Housing Choice Voucher, a temporary housing subsidy provided by a community-based rapid re-housing program (CBRR), project-based transitional housing (PBTH),2 or to a fourth control group that received usual care (UC). UC families continued to work with shelter staff to find housing, using whatever resources were available in the community.

Sampling

For the larger study from which this qualitative study was drawn, 2,307 families were recruited after having spent at least seven days in shelters in 12 different sites across the United States. For the purposes of this research, a family was defined as a minimum of one caregiver and one child. Families were screened for eligibility for available programs in each of three interventions: SUB, PBTH, CBRR (all families were eligible for UC). To be eligible for SUB, families could not have drug or other recent felony convictions, have been evicted by a federal housing agency, or owe arrears to a PHA. Many sites also required residence within the PHA’s jurisdiction. Eligibility for PBTH was largely determined by local agencies, and families often had to be sober, meet income requirements, have a clean criminal history, and have the right family size and composition for the unit that was vacant. For CBRR, families had to be homeless and without financial means to secure housing. On the other hand, families selected for CBRR were supposed to be self-sufficient at the end of a temporary period of financial assistance, which led most sites to impose minimum requirements for income. Further details about eligibility are available in Gubits et al., 2013.

After screening, families were randomly assigned to UC or to an offer of assistance in a particular intervention arm (e.g., PBTH) and (non-randomly) to a program within that arm for which they appeared eligible.3 Programs could and did further screen families for eligibility. Then families could accept the offer of assistance or decline it and seek whatever other opportunities they could find. These choices are the focus of the current study.

Eighty participants (77 women, 3 men) in the larger study were recruited to participate in open-ended interviews lasting about two hours and conducted between three and 10 months (mean = 6.4 months, SD = 1.9 months) after the family had been randomly assigned to one of the study conditions. We selected four locations for geographical diversity: Alameda County, CA (Oakland and surrounding communities); Kansas City, MO; New Haven and Bridgeport, CT; and Phoenix, AZ. Participants were 52.5% black, 30.0% white (including 11.3% white, Hispanic), 3.7% Native American, and 13.7% other. We sought five families in each condition in each city. When fewer than five families in a particular condition were interviewed in one city, families from that same condition were oversampled in other cities.

Procedures

Interviewers from Abt Associates conducted and recorded semi-structured, in-depth interviews with the participants. During each interview, one researcher spoke with the participant, and another researcher took notes in order to capture relevant information that might be lost in the case of a recorder malfunction. All recorded interviews (and notes, where needed) were converted to de-identified transcriptions. Each interview contained questions focusing on four main themes: housing decisions, family composition, parenting, and social support. This paper analyzes participants’ responses to questions about their housing decisions, including questions about when, where, why, and how they moved from one place to another.

Data Analysis and Efforts to Ensure Credibility

A team of researchers at Vanderbilt University coded the interview transcripts using Nvivo 9, conducting thematic coding of the data in pairs, holding weekly reliability checks in an iterative process for codebook development (as described in more detail in Mayberry et al., in press). The use of regular reliability checks and codebook iterations had two major advantages. First, it ensured that the participants’ responses, and not our preconceived expectations, guided our coding. We were careful to ground all of our codes in the words and phrases of the participants, with many of the code names representing the terminology used by participants. Second, the final iteration of the codebook represents what we believe to be a reliable way of coding. By the end of the coding process, the discrepancies in coding were usually only differences in the amount of context we captured for a given code. In other words, one person would code four sentences and the other would code five sentences as Code X. We considered these discrepancies less serious than attaching entirely different codes to a block of text, although we still resolved any discrepancies we encountered.

Once the final coding scheme was applied to all of the interviews, we began analyzing the data identified as relevant to housing decisions. We used axial coding principles (Strauss & Corbin, 1990) to create specific categories and dimensions within the themes. For example, the original codebook contained a theme called “Exclusionary Rules,” under which we coded participants’ discussion about rules with consequences that could result in either ineligibility for a program or termination of the program’s services. Axial coding helped us to identify certain types of rules that were more common than others and ones that were especially important in the minds of the participants. Thus, the data analyzed in this report have been coded by multiple coders using grounded theory principles and the constant comparative method with axial coding techniques that served to provide more specificity in the coding scheme. Authors B.W.F. and L.S.M. conducted a reliability check by independently coding a random sample of 10 interviews using the final coding scheme. To measure our reliability, we averaged Cohen’s κ across all 12 themes in the final codebook (including themes and axial codes; κ = .84, SD=.17).

Results

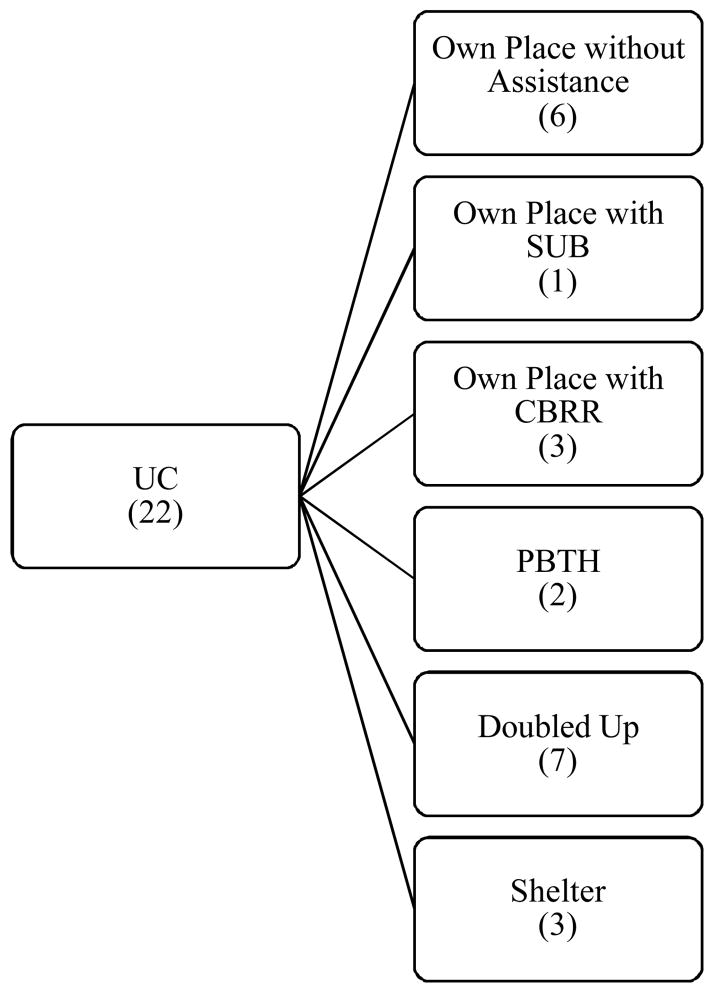

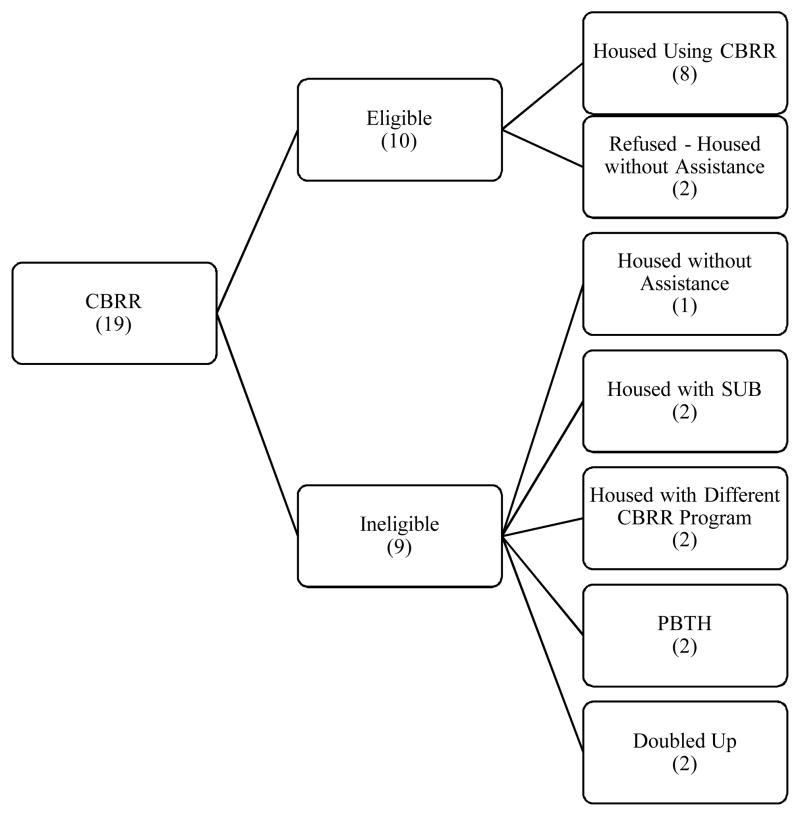

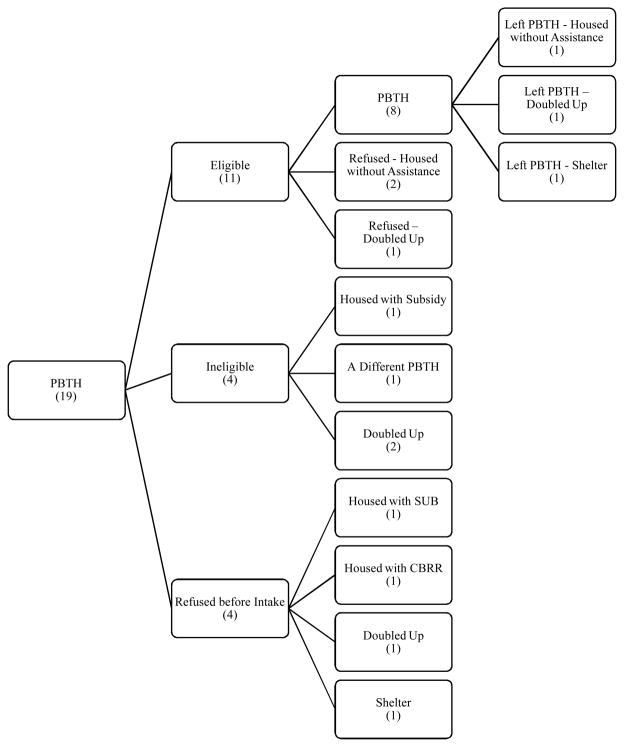

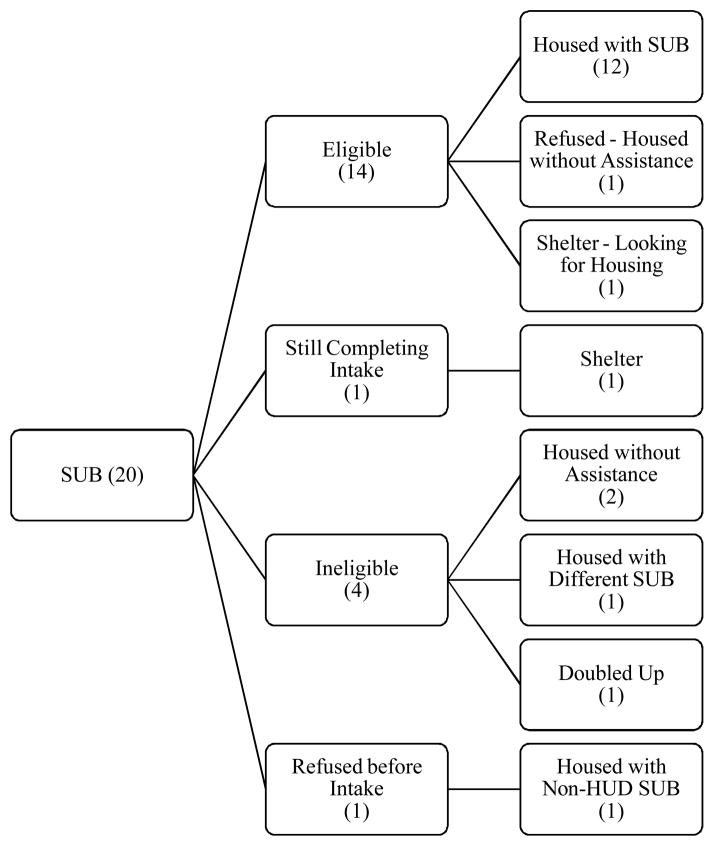

Figures 1, 2, 3 and 4 show the housing outcomes of families assigned to the three experimental interventions and UC: those found eligible or ineligible for each condition, the location of eligible families at the time of the interview (including “doubled up” when living temporarily with friends or family), and, if in their own place, whether or not they had a subsidy. The housing trajectories are quite complex. Three key factors affected them: eligibility for interventions, the location of housing, and the degree of stability it provided.

Figure 1.

Housing outcomes at time of interview for families assigned to UC.

Figure 2.

Housing outcomes at time of interview for families assigned to CBRR.

Figure 3.

Housing outcomes at time of interview for families assigned to PBTH.

Figure 4.

Housing outcome at time of interview for families assigned to SUB.

Eligibility

Although families in the larger study were pre-screened for eligibility to available programs for the interventions to which they were assigned, programs could apply their own rules and find additional families ineligible after randomization. Additionally, families could drop out between random assignment and the eligibility determination—for example because they knew they would be found ineligible. The combined rates of dropout prior to an eligibility determination and because of ineligibility in our sample (47% CBRR, 42% PBTH, 25% SUB) were close to those from the larger study (37, 58, and 19%, respectively, Gubits et al., 2013). Our sample included the two sites of twelve in the larger study where CBRR agencies’ eligibility requirements were most restrictive. Families who were ineligible for or who declined their assigned intervention still had to choose housing from other options available to them, and most (86%) of our sample had left shelter by the time of the interview.

Location, Location, Location

Location restrictions affected families’ decisions to take or keep an assigned housing intervention. Vouchers were restricted for a year to the service area of the PHA that issued them (generally a political jurisdiction); thereafter users were allowed to move with their voucher, or “port,” to a new service area. In three of the four sites, some families either declined to lease up because of location restrictions or planned to port at a later date. One participant who declined to lease up with a voucher did so because the housing options available to her in the service area of the local public housing authority lacked public transportation. Three families planned to port to a different location at the end of the first year, even though this would require an additional move, and another family planned to port at an unspecified future time.

PBTH is more restrictive than vouchers, requiring participants to live not just in the jurisdiction but at the program site. Participants turned down those programs when they were too distant from family and friends or in neighborhoods that they believed would have a negative impact on children. Five participants declined PBTH because of such concerns about location, with one participant citing several other reasons as well.

Across intervention conditions, families wanted to live in a familiar location, one that would allow children to remain in the same schools, and one near family, friends, and transportation. Proximity to members of the social network was important for both emotional and practical support. Several participants wanted simply to be able to spend time with their family. One poignant example was a participant who wanted to live near her sick 79-year-old mother in order to provide care and support in what were likely her mother’s last few months of life. Another participant assigned to UC explained that she wanted to live near family so that her children could have relationships with their relatives in a way that she did not:

It’s because my mom, she now has my little brothers and my sister and I want to spend time with them. I haven’t seen them in about 10 years and I want my children to know their auntie and uncles.

Lacking financial resources, participants found it important to live near infrastructure or people who could provide tangible resources such as childcare, transportation, and other help they needed to maintain their jobs and other patterns of daily living. One SUB user reflected on these positive changes associated with her family’s new housing location:

…it made everything a lot easier. It was easier to go to school because I go to [College] in [Neighborhood]…And then daycare is also out here. My grandmother will watch [my daughter] for me, so that’s been a lot easier.

Many participants relied on public transportation to get from place to place and needed to live near a bus stop in order to maintain their ability to move about the city. As one participant assigned to UC explained:

I work on this side of town, so transportation might be a little problem, because it’s like, I don’t have a car right now, so I don’t want to go live in the country somewhere where I can’t even get to the grocery store or, you know, get back and forth to work, drop my daughter off at school, so that would–might be the only thing, transportation.

Another described why the place she chose to obtain with her CBRR subsidy was superior to shelter:

[The shelter] was inconvenient because my kid’s school was on this side of town and school buses–during snow the school bus didn’t come to pick them up at the shelter, getting back and forth. [The current location is] more local to everything that we’re [used] to as far as our support systems, church, the school, so it’s more stable for us, more of a comfort zone.

Stability

Location was also important because certain locations were perceived to offer more stability, something almost all participants expressly desired. Although the definition of stability varied from family to family, four components seemed important: (a) living in their own residence; (b) that is affordable; (c) with no family separations; (d) for an extended time. One participant’s words represent well the sentiment that was expressed by many. When asked about the best thing about her home obtained with a CBRR subsidy, she explained:

Well for one because I was in my own unit, privacy, the assistance was awesome, I was then able to bring [my child] back. I felt stable for a minute, I felt like I could breathe for a minute and it was right away I recognized that it was a place for me to help myself, to better myself. It was rough though too, it was very rough but those were the best things about it, it was a place for me to help myself.

Participants frequently talked about stability as important for their children. When asked why she wanted to stay in her current living situation using SUB, one participant said:

Mainly for my kids and some stability, for them not having to move school to school.

Participants assigned PBTH and SUB both faced policies that would not allow their families to remain housed together. The PBTH facility did not allow men to stay there, and the criminal history requirements of SUB made one family member ineligible:

I do think it would be easier if Section 8 allowed my fiancé to live here. That definitely would make it easier, you know? … Especially since I mean like if he was like a violent criminal or something like that, I could understand. But I mean, he’s a shoplifter. So it’s like they’re protecting people from the big, bad shoplifters.

Compromises

The need to make major decisions without much time or many resources frequently led families to make choices that they later regretted. One participant assigned to CBRR reported:

When I saw this apartment, it was basically I was on my way. I was supposed to. You know how they give you three months at the shelter? My three months was up and I took this apartment.

However, she did not realize at first the extent to which the apartment was not a good fit for her:

The cops are constantly here kicking down doors for drugs. We have prostitution running out the building. I was told that don’t worry about it, it’s a good building. We have a security guard downstairs 24/7. The only time I saw a security guard is when the landlord is coming to pick up his rent and the security guard walks into your door. We don’t have heat in the wintertime… I have mold in my bathroom. They came and cleaned four different times. Now they threw white paint over the walls but there’s still mold around the tub, mold underneath the sink, in my kitchen I have mice holes everywhere. They knew I had to hurry up and leave the shelter because the shelter already gave me two extra weeks to stay there so they told me everything was gonna be fixed. It’s been a year. Nothing is fixed yet. Nothing is fixed… If you see I have no smoke detectors or carbon monoxide detectors. You’ll see I came out four different times and told the landlord to put those detectors in. … My house has been broken into four different times because you can take a credit card and actually open the door, open doors with them.

This participant explained that the local CBRR program encouraged many of the other shelter residents to move into this apartment building, where they had equally terrible experiences. Other participants described moving quickly into a neighborhood where they did not feel comfortable letting their children play outside or where drugs were sold. Participants also described shoehorning large families into very small apartments.

Other families avoided clearly inappropriate dwellings, but were still not able to optimize:

I wasn’t being too picky at the time because the shelter I was in was a short-term shelter, and they were getting ready to kick us out. So I could not afford, really, to be picky. So I seen one unit, I didn’t like it at all. It was on a third floor, it was really small, and can you imagine six people in a small apartment? So then I saw this one and I said “Well, this is decent.” And it had a washer and dryer, first floor which I felt I wouldn’t bother anyone with the kids and everything, and I just said, “I’ll just take this.”

These compromises were especially prevalent in interventions where participants were responsible for finding their own housing: CBRR, SUB, and UC. The added stress of finding funds for housing made the participants assigned to UC especially vulnerable to having to make unwanted compromises.

In addition, families often sacrificed things that were important to them in order to obtain housing, but these sacrifices were not overriding factors in their housing decisions. Participants mentioned their regret at not having such features as space for their children to play outside the home, a safe, child-friendly neighborhood, and enough bedrooms for each family member. The pressure they experienced to find housing quickly made some of these important housing features less important.

Intervention-specific Concerns

Desires for stability and living near family, transportation, and other familiar resources were common across conditions, and families in all conditions felt pressured to leave shelters because of time limits. Other concerns were more particular to specific interventions, as detailed next.

Permanent Subsidies

Participants housed using SUB were generally the most satisfied with their housing. For example, this mother expressed profound relief at the opportunity to live in subsidized housing and also belittled problems some people have with using subsidies:

If it wasn’t for this, I don’t know where I’d be. Honest, to tell you the truth. I don’t know what we would be. It’s all just fine. Anybody who can’t do it, I don’t believe them. Without a car. Without a job. I don’t believe them. Because I have four kids and no job and no car, and I did it. Yeah, so it’s awesome.

Four participants encountered landlords who would not accept their vouchers, although they all eventually found other landlords who would accept them.

Another participant spoke favorably about SUB:

Very grateful because we’ve been paying fair market and I’ve never had Section 8 or anything or any kind of HUD assistance. So for me to actually have a nice house for our children without having to be completely worried about rent, rent, rent for this month because my husband is trying to go back to school full-time and so am I… that way we know we’re supported and we don’t have to worry about losing the house because we are trying to go to school and work and we’re safe, we’re okay and we’ll get things back on track.

One family who came to the top of a waiting list for SUB left PBTH to take advantage of it, and five of the 10 families in PBTH at the time of the interview said they would do so if they got the chance. A participant who was assigned to and living in PBTH stated:

I just really need someone to help me get a Section 8 voucher. That’s it because, like I said, I’m grateful that we got this. I mean it’s cute and everything but it’s not safe.

Transitional Housing

PBTH was the offer most frequently declined by families. In addition to location, a reason sometimes mentioned was the inability to bring all family members. One participant offered a few reasons for declining PBTH, including being allowed to bring only one bag per person. Three participants left PBTH early: one because she could afford housing independently and wanted her daughter in a better environment, one because he found PBTH stressful and was able to afford housing on his own (although he later returned to shelter after losing a job), and one who left for a doubled-up situation because she felt unsupported:

And they wasn’t helping me. They get fundings for you to go back to school and do what you want to do, but she kept telling me she did not have the–”Well I don’t know if we have the fundings for you to go back to school.” If you’re here to help me, I understand you want me to go out there and do what I have to do; that’s okay, but if I–I know ya’ll pay for classes. I wanted to take phlebotomy. She did not want to pay for that. She did not want to give me the money to pay for that class.

Families also planned to leave PBTH early because they felt it was not a good place to raise children:

I don’t like being in a building because I fear for my daughter to come through the hallway. She always have to come to the side door because I don’t want–there’s too many young men in the building, and I don’t want her to get snatched or anything like that. So I have a few concerns.

[There’s a] lot of arguing. All the cigarette smoking going on. It’s always some kind of drama going on up in here. And I’m not–you know, I left the shelter because… there was some drama there, and I didn’t want my daughter to be in that situation. So that’s another reason. And I’m really considering just like just getting out of this program period and just doing it on my own. Cause it’s not helping me.

The second participant even considered returning to shelter rather than staying at the transitional program.

A unique feature of PBTH was the availability of supportive services. No family mentioned this as a reason for moving into PBTH, but some participants found services helpful once they were there:

I mean, when you go down there, they help you. They already have the listings of work that you can go through. And everything was helpful as far as getting into the right agencies, finding work, making you feel like you are still a part of something, you know? They never downed you for any reason. So yeah, that was comforting.

No families were dissuaded from PBTH by required service use, although families who would have found this burdensome may have been screened out by responses to eligibility questions.

Community-based Rapid Re-housing

Time limits in CBRR engendered considerable anxiety in participants. By statute CBRR under HPRP was limited to 18 months, with requirements for recertification of eligibility every 3 months, but many communities aimed for shorter periods of assistance in order to spread the funds more broadly. Because of the recertification requirements, participants were often uncertain about how long their assistance would last, how much assistance they would receive, or on what this all depended. The uncertainty engendered feelings of instability and lack of control. When asked how much longer they expected to receive CBRR assistance, three participants replied:

Good God, I don’t know. They told me it was six to–every three months they evaluate you. And the longest you can stay on there is 18 months. And usually they try to get you off within six to 12 months. But they don’t communicate with you.

Well she said up to a year, so it’s kind of in the air, I guess. Every three months they let me know, and it depends on the funding, which is nerve wracking for me.

[The assistance] will stay steady for three months, and then they do an evaluation to see how my income is going; and if it’s lower, higher, and according to that, that’s the amount that I got to pay.

Recipients of CBRR funds also expressed uncertainty about their future after the assistance ended. Some participants hoped to be able to stay in their current living situation but were unsure whether they would be able to afford it. Others knew that they would have to find a different place to live once the assistance expired. One participant who was trying to balance employment, further skills training, and care for her family articulated her frustration with the time limits very clearly:

Okay, we get out of a shelter, find a place for who knows really how long, and then what? Wind up back in a shelter? It seems kind of counter-productive to me. Although I appreciate the help, certainly, but ultimately it seems kind of failed in that aspect… because if by the end of the year I don’t have a way…Where do we go from there? Everything seems to be closed.

Another major concern expressed by families in CBRR was the requirement to demonstrate income quickly. Several families felt that this created a double bind: they had to find a job quickly to become eligible for assistance, but the kinds of jobs that were available quickly would not sustain them after assistance expired. As one participant put it:

But something like rapid re-housing, when you’re a student and you’re working towards a goal and you have a real goal, that’s not fair because it’s like what you’re going to do? Is the person is going to have to struggle to get a job? And it’s hard to get a job, but there are jobs out there. You know, it’s not easy. However, they’re going to like–you’re going to have to wind up almost cutting out school, because if you don’t have someone to watch your child at night, and you can’t go to school at night… And that’s the downfall of everything.

This participant chose not to pursue employment to stay in school, ensuring her ineligibility and effectively giving up the opportunity for housing assistance via CBRR.

Another participant who took the first job she found to qualify for CBRR assistance later realized that she was stuck working for wages so low that she could not save enough money or take time off to find a better job.

I felt like I had to get a job, fine I’ll work, that’s not the problem. It’s just the type of job–I had to in such a hurry I grabbed what I could. And basically it ended up being a job that I wasn’t happy with and a job that was a dead end and low paying of course and physically working you butt off and tired…I work at a daycare, I’m exhausted when I come home, I get $8.25 an hour, how am I supposed to survive off of that? I need a degree, that’s what I would like and not only just for to get out there and to get a better job, a higher paying job but just because I want it, I want to earn it, I want it and I want to set the example to my children… So now I’m like there and what do I do, do I resign? Now you’re there and it’s not easy to get back out because of course [I’m] getting paid now, if I resign and I can’t look for work, I can’t, I got two days off I can’t, it’s impossible.

This participant was unsure whether she would be able to afford to stay in her current home when assistance ended. Her ability to maintain her housing was hampered by her efforts to become eligible for CBRR in the first place.

A third participant articulated the problem more globally:

I’ve always had the mindset of getting out of the programs because I think that partly they’re designed to keep you down because the minute you make too much money they start taking everything away from you so you’re always here. You can never go above. You can never save money. You can’t ever do anything. So I felt like I’m always going to be here if I’m in a program.

These participants felt that the homelessness assistance system in general, and CBRR in particular, was stacked against them. If their time ran out in shelter, they were forced to find a place to use CBRR quickly. If they could not maintain a regular income, their CBRR funding was taken away. If they made too much money, their benefits were decreased.

Shelter and Usual Care

An important constraint on stability, and one of the most common reasons that people gave for moving from one place to another, was a limit on the amount of time they were allowed to stay in shelter or continue receiving assistance after shelter. Many people moved out of shelter because their time was running out, even if they had little plan for what would come next. One woman moved in with a friend at the end of her time in shelter in order to buy herself more time to find a place to live:

I was staying with my girlfriend that was also in [shelter]… she let us stay with her until we was able to get an apartment that came available for us.

On the other hand, some participants used their knowledge of time limits strategically to maximize the total period when they would have help with a place to stay. For example, one participant who was offered CBRR assistance in December did not take it until May:

I got the assistance [but] I didn’t take it until… May … [Shelter 1] it’s like really temporary–it’s an overflow–and then I went to [Shelter 2] and I stayed there literally 120 days, literally that’s your maximum amount and I literally lived there for 120 days. I moved out on the day I was supposed to exit, yeah I lucked out, it worked out really good. And so that was … May 13th, so that’s when the lease started here so we’ve been here May, June, now July.

Although all participants lived in shelter at the beginning of their participation in the study, those assigned to UC or deemed ineligible for their assigned intervention seemed to experience the anxiety associated with time limits most strongly. As is usual in their communities, they were not provided with an alternative to shelter and were responsible for finding housing on their own before their time in shelter expired. Some families assigned to UC, SUB, or CBRR did receive help from the shelter in locating housing, but this assistance ranged from being beneficial (one staffer drove a participant to visit housing options) to burdensome (when families were referred to housing they deemed inadequate or to non-helpful resources).

Like SUB and PBTH, informal housing situations could require choices between particular housing possibilities and preservation of the family. As one participant put it:

If I was moving from place to place it was harder for me to be able to find a place with both my kids … so I would say I only have my oldest son… It was more convenient so. [Interviewer: So someone was more likely to say it’s okay if you only had one of your sons with you?] Yeah.

Participants who were doubled up with others (in UC or after being turned down by housing programs) also faced implicit limits on length of stay, which could lead them to move frequently from one doubled-up situation to the next:

Well like if I go stay with my friend for a few days, I’ll wait like a week, and then I’ll go to my mother’s house. And then like she’s about to go out of town in July, I mean August 1st, so then I’ll go stay with my auntie. And I just–how do I go about this homelessness?

Discussion

Securing stable, affordable housing in neighborhoods of their choosing was a challenge for many of the families interviewed here. It is clear that many families felt hedged in by the systems in which they were embedded. The complex array of factors that affect families’ housing decisions can be organized into “push” and “pull” factors (Table 1). Push factors such as a stressful environment influence people to leave housing situations. Pull factors, on the other hand, are factors that influence people to go to a particular housing situation. For example, the opportunity to sign a one-year lease for an apartment near family using SUB could have three different pull factors: stability (with the one-year lease), location (being near family), and affordability (using SUB).

Table 1.

Push and Pull Factors

| Push Factor | Pull Factor |

|---|---|

| Time Limits | Availability |

| Unaffordability | Near Friends/Family |

| Stressful Environment | Transportation Good Environment for Children School Stability for Children Stability Avoiding Family Separation Improved Housing Conditions |

Even though families in our study described a relatively large number of pull factors, these were frequently trumped by much stronger push factors. For example, time limits in shelter forced families to find housing elsewhere quickly, limiting their ability to attain other goals such as finding a good neighborhood for their children or finding a place they could afford long-term and therefore compromising their goal of stability. This is consistent with the steep learning curve for voucher users who had only a limited time to learn enough about vouchers to use them successfully (Wood, Turnham, & Mills, 2008). Families often did not have resources such as transportation to visit multiple housing options and reported few options that were affordable for them. Certain policies within each intervention also constrained families’ abilities to pursue multiple goals simultaneously. SUB recipients who had family members with certain types of criminal records had to choose whether to use their subsidies or keep their family together. Similarly, some PBTH facilities were single-sex facilities, forcing families to choose between receiving assistance and remaining intact. The income requirement and recertification process of CBRR meant that some families had to quickly accept low-wage jobs or give up on post-secondary education in order to qualify. Families without an offer of assistance may have been limited by the low quality and lack of geographic diversity of low rent housing (Hoch, 2000). Moreover, a lack of time and resources limited the ability of families in shelter to satisfice before they reached limits on their stays or felt they needed to leave shelter, leading to attenuated aspirations for their next residence. One SUB user, speaking of her first residence after shelter, explained:

Well, I mean, this really didn’t fit my standards because at the time I wasn’t worried about my standards. I was just worried about getting out of [shelter]. So, after I moved here, then, yeah, I figured out it didn’t fit my standards because it’s small.

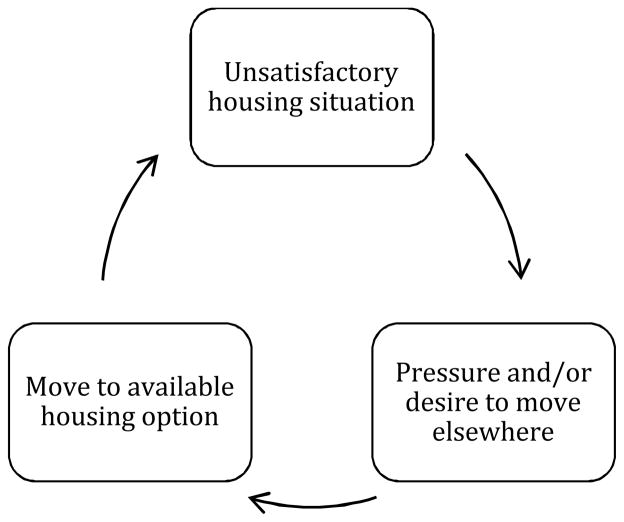

Limited resources forced families to prioritize their goals in order to find housing that met at least some of them. Sometimes they were meeting only one goal–to move out of their current living situation. Thus, the “best” options were often ones that left families dissatisfied, prompting the desire and/or need to move to another location, in a cycle of unsatisfactory housing situations shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Cycle of unsatisfactory housing situations.

The housing decisions of families in this study can be conceptualized as reflecting both (a) how families balance their goals with the options available to them in the context of their limited resources and (b) the inherent limitations of the housing options afforded to them through the larger housing market and the policies of programs designed to help them become stably housed. Although bounded rational choice theory (e.g., Simon, 1955; Simon, 1956) builds on traditional rational choice theory by emphasizing families’ reasoned decision making within the context of time and other constraints, it does not fully account for the limited agency that families faced in the presence of both random assignment and strong push factors such as time limits and eligibility rules. Lee (1966) suggests that in addition to push factors at the residence of origin and pull factors at potential destinations, intervening obstacles and personal factors can direct families into decisions that are not completely rational. In our study, the intervening obstacles (i.e., limited resources and constraining policies) were often so difficult to overcome that the first housing situation after shelter was unsatisfactory, prompting successive moves. The concept of intervening obstacles may also explain why so many families moved to less desirable housing situations than those offered to them through the study. For example, sometimes families who were pursuing a desirable housing option declined their intervention offer and then encountered obstacles that interrupted their planned trajectory.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study offered resources, particularly SUB and CBRR, that are not typically available to families experiencing homelessness, thus families usually experience even more constraints than described here. The study also allocated resources in a way that disrupted the usual geographical pattern of service allocation. For example, in Alameda County prior to the study, shelters sent families to particular PBTH programs that were often operated by the same agency, thus keeping families in the same geographical area. Although the study established geographical preferences, when openings in their preferred geographic area were unavailable, families were referred to a program in another city. For example, the Oakland Housing Authority provided the most Housing Choice Voucher openings at the Alameda County site, but most families came from locations outside of Oakland. Thus, the desire of families to move to new areas when permitted to do so and the prominence of location as a concern for families in electing not to take offered housing assistance may be exaggerated relative to a more usual service environment.

Our interviews (occurring an average of 6.4 months after enrollment in the randomized evaluation study) did not capture families who had reached time limits for either CBRR subsidies or PBTH. Further, no families had achieved financial independence following CBRR assistance by the time of the interviews. Therefore, we cannot be certain whether the cycle of unsatisfactory housing situations will continue, or whether this is only a short-term phenomenon before families stabilize. Because of the short-term nature of the data, we rely in part on participants’ responses about their plans for future housing. This information is certainly important but may not correspond to actual decisions and actions as they play out over time. Additionally, there was only a small sample of families that declined an offer or left an intervention early, potentially limiting the generalizability and exhaustiveness of our findings. Still, the responses from the 80 families in this study will be useful for understanding some of the patterns that emerge from the larger experiment involving 2307 families and 12 sites over a longer time period.

Reliance on participants’ own words to describe their motivations and experiences is both a strength and limitation of the study. These interviews provide important insights into how homeless families make the housing decisions that they do and why options designed by policy makers do not always seem attractive to families who experience them. These insights can help to explain patterns unveiled by future quantitative analyses and help researchers and policy makers consider ways in which policies might productively be modified. However, families may not give the whole story (for example, misdemeanor shoplifting might not disqualify a family from use of a Housing Choice Voucher as described by one participant), and several important voices are still unheard, notably those of children and service providers. One study interviewed providers of HPRP-funded homelessness prevention programs (which provided the CBRR intervention in our study) and demonstrated how perspectives may vary (Urban Institute, 2013). One of our respondents complained that CBRR staff had directed her and others in her site to housing she perceived as inadequate. The Urban Institute (2013) report notes that HPRP staff in some sites saw it as a helpful service that they made arrangements with landlords who could serve their clients. Also, several of our respondents expressed considerable anxiety about the end of CBRR funding and uncertainty over whether it would continue or not. Some programs that initially offered families longer periods of support later shortened those periods because they felt that families were not pursuing self-sufficiency goals until their funding was about to run out (Urban Institute, 2013).

Policy Implications

CBRR aims to be a flexible and cost-effective alternative to permanent housing subsidies by giving each family only the minimum amount of help necessary to stabilize. Therefore, help is time-limited and titrated, and families must be re-certified for eligibility every three months. The findings of this study suggest that these arrangements create considerable anxiety for families. It remains to be seen whether this anxiety is productive, spurring families to greater independence, or debilitating. The 18-month follow-up survey to be conducted as part of the larger study will be helpful here. Nevertheless, families’ anxiety suggests a downside to “progressive engagement” strategies in which clients who are not stabilized with limited assistance are screened for eligibility for additional assistance on a phased basis (Culhane, Metraux, & Byrne, 2011). It is possible that fixed grants of time-limited support, perhaps with clear criteria of what families must accomplish to obtain an extension, would both reduce anxiety and maintain motivation.

Some families found the push to secure income rapidly required them to take jobs with little prospect for advancement or give up opportunities to develop human capital such as further education or training. This tension between human capital development and employment is not a new issue. While research on training programs often has failed to show positive results for employment, a recent study of training programs focused on particular sectors and targeted to disadvantaged populations found substantial gains for both employment and earnings (Maguire, Freely, Clymer, Conway, & Schwartz, 2010). Although in-depth interviews of participants in a study of the use of housing vouchers by welfare families suggested that vouchers might free up additional time or money for education and training, those receiving vouchers were in fact no different from those not receiving vouchers in the amount of education and training they sought during the follow-up period (Mills et al., 2006). Moreover, evidence suggests that families achieve greater earnings in short- and medium-term when employed immediately rather than seeking education or other sorts of human capital, and that their long-term earnings do not suffer as a result (Ashworth, Cebulla, Greenberg, & Walker, 2004; Bloom, Hilly, & Riccio, 2003; Greenberg, Cebulla, & Bouchet, 2005). So, even though some participants in this study reported giving up education or training opportunities in favor of immediate employment and a CBRR subsidy, prior research suggests that this tradeoff may not be harmful for families.

PBTH was the intervention that was hardest for families in the larger study to get into (Gubits et al., 2013) and also the intervention that families were most likely to turn down or leave. Families encountered facilities in undesirable locations, rules that excluded men (including fathers of children), and various environmental stressors. This study did not include scattered-site transitional housing that may have fewer drawbacks than congregate living programs. PBTH is expensive because of the additional costs of the services that are part of the intervention (Spellman et al., 2010). The 18-month follow-up survey in the larger study will be helpful in understanding whether it repays the investment, but it is already clear that families who might benefit most from the intensive services provided are often barred from receiving them (Gubits et al., 2013).

Participants in this study were most satisfied with vouchers: they took them when available, and hoped to receive them, even if assigned to other interventions. In the larger study of which this is a part, 94% of families who were issued vouchers had leased up as of September 1, 2012 (Gubits et al., 2013), higher than any success rate found by previous studies of voucher use. Although families encountered landlords who would not accept vouchers, they persevered and found other landlords who would. Previous research suggests that housing vouchers are successful in reducing returns to shelter and enhancing stability. This study suggests that homeless families can use vouchers successfully and supports analysts who suggest that more targeting of the limited supply of vouchers to households with greatest needs, including homeless families, would reduce rates of homelessness (e.g., Early & Olsen, 2002).

Until the parent study is farther along, many questions will remain unanswered. Researchers in other studies have noted a surprisingly high percentage of families who discontinue using their vouchers when they could renew (Lubell, Shroder, & Steffen, 2003; Gubits, Khadduri, & Turnham, 2009). As the larger study continues to track the experience of families, we will learn more about whether this is true in our sample of families that started out in shelter and whether vouchers create more long-term stable housing than other types of assistance. The potentially long-term character of voucher assistance may make it more expensive per family than either CBRR or PBTH.

In sum, this study provides insights into how families experiencing homelessness make housing decisions and how they view particular options offered them by the homelessness service system. It suggests that some constraints–for example, the reluctance of owners of rental housing in some types of locations to accept vouchers–are less important to homeless families, who may be more desperate for options than housed families. This study also helps to explain why families often leave PBTH before they must. Perhaps most importantly, it suggests that options such as CBRR have previously unreported drawbacks from families’ perspectives. More generally, it highlights the constraints of policies, time, and resources that homeless families face in making housing decisions and the resultant compromises they make. Finally, our findings demonstrate that homeless families and stably housed families have similar goals and similar decision making processes. Goals and priorities described by our participants included being close to work or school, family, and friends, and a desire for stability and safe environments in which to raise their children. Families, whether in shelter or elsewhere, have similar goals for housing and they prioritize and balance their family goals with the options and resources available to them.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded with support from the National Institute of Child and Human Development, grant # 5R01HD066082 to Vanderbilt University. The larger randomized evaluation study was funded by contract C-CHI-00943, Task Orders T-0001 and T-0003 from the Department of Housing and Urban Development to Abt Associates.

Thanks to Jacob Klerman and Anne Fletcher for comments on an earlier version of this paper.

Footnotes

Families were not assigned to scatter-site transitional housing programs in this study to distinguish PBTH more clearly from CBRR, in which families receive a temporary subsidy in scattered locations, and from SUB. Scattered-site transitional housing often follows a transition-in-place model, in which a Housing Choice Voucher is used to support first housing with services and then housing without services when the family no longer needs them.

In the larger study, comparisons of outcomes for any two intervention arms will include only families eligible for both arms, to preserve the integrity of the experiment.

Contributor Information

Benjamin W. Fisher, Vanderbilt University

Lindsay Mayberry, Vanderbilt University.

Marybeth Shinn, Vanderbilt University.

Jill Khadduri, Abt Associates.

References

- Ashworth K, Cebulla A, Greenberg D, Walker R. Meta-evaluation: Discovering what works best in welfare provision. Evaluation. 2004;10:193–216. [Google Scholar]

- Bacon L. Godinez v. Sullivan-Lackey: Creating a meaningful choice for Housing Choice Voucher holders. DePaul Law Review. 2005;55:1273–1308. [Google Scholar]

- Basolo V, Nguyen MT. Does mobility matter? The neighborhood conditions of Housing Voucher holders by race and ethnicity. Housing Policy Debate. 2005;16:297–324. [Google Scholar]

- Bassuk EL, Geller S. The role of housing and services in ending family homelessness. Housing Policy Debate. 2006;17:781–806. [Google Scholar]

- Beck P. Fighting Section 8 discrimination: The Fair Housing Act’s new frontier. Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review. 1996;31:155–186. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom HS, Hilly CJ, Riccio JA. Linking program implementation and effectiveness: Lessons from a pooled sample of Welfare-to-Work experiments. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. 2003;22:551–575. [Google Scholar]

- Buron L, Locke G. Study of household transition from the Disaster Housing Assistance Program (DHAP-Katrina) Bethesda MD: Abt Associates, Inc; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Burt M. Life after transitional housing for homeless families. Washington DC: Urban Institute and Planmatics, Inc; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Burt MR, Pearson CL, Montgomery AE The Urban Institute, Walter R. McDonald & Associates, Inc. Strategies for preventing homelessness. Washington, D.C and Rockville, MD: Urban Institute and Walter R. McDonald & Associates, Inc; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cortes A, Henry M, de la Cruz R, Brown S. The 2012 Point-in-time Estimates of Homelessness: Volume 1 of the 2012 Annual Homeless Assessment Report. 2012 Retrieved from U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development website: https://www.onecpd.info/resources/documents/2012AHAR_PITestimates.pdf.

- Cragg M, O’Flaherty B. Do homeless shelter conditions determine shelter population? The case of the Dinkins deluge. Journal of Urban Economics. 1999;46:377–415. [Google Scholar]

- Culhane DP, Metraux S, Park JM, Schretzman M, Valente J. Testing a typology of family homelessness based on patterns of public shelter utilization in four U.S. jurisdictions: Implications for policy and program planning. Housing Policy Debate. 2007;18:1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Culhane D, Metraux S, Byrne T. A prevention-centered approach to homelessness assistance: A paradigm shift? Housing Policy Debate. 2011;21:295–315. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel TH. Bringing real choice to the Housing Choice Voucher Program: Addressing voucher discrimination under the Federal Fair Housing Act. The Georgetown Law Journal. 2010;98:769–794. [Google Scholar]

- Dasinger LK, Speiglman R. Homeless prevention: The effect of a shallow rent subsidy program on housing outcomes among people with HIV or AIDs. AIDs and Behavior. 2007;11:128–139. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9250-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devine DJ, Gray RW, Rubin L, Taghavi LB. Housing Choice Voucher location patterns: Implications for participants and neighborhood welfare. 2003 Retrieved from U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development website: http://www.huduser.org/Publications/pdf/Location_Paper.pdf.

- Early D, Olsen E. Subsidized housing, emergency shelters, and homelessness: An empirical investigation using data from the 1990 census. Advances in Economic Analysis. 2002;2:1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Edin K, DeLuca S, Owens A. Constrained compliance: Solving the puzzle of MTO’s lease-up rates and why mobility matters. Cityscape. 2012;14:181–194. [Google Scholar]

- Feins JD, Patterson R. Geographic mobility in the Housing Choice Voucher Program: A study of families entering the program, 1995–2002. Cityscape. 2005;8(2):21–47. [Google Scholar]

- Finkel M, Buron L. Study on Section 8 vouchers success rates: Volume 1: Quantitative study of success rates in metropolitan areas. Cambridge, MA: Abt Associates, Inc; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Finkel M, Kennedy SD. Racial/ethnic differences in utilization of Section 8 existing rental vouchers and certificates. Housing Policy Debate. 1992;3:463–508. [Google Scholar]

- Fogel SJ. Moving along: An exploratory study of homeless women with children using a transitional housing program. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare. 1997;24(3):113–133. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman L. The impact of source of income laws on voucher utilization. Housing Policy Debate. 2012;22:297–318. [Google Scholar]

- Galvez MM. What do we know about Housing Choice Voucher Program location outcomes? 2010 Retrieved from Urban Institute website: http://www.urban.org/uploadedpdf/412218-housing-choice-voucher.pdf.

- Gilderbloom JI, Squires GD, Wuerstle M. Emergency homeless shelters in North America: An inventory and guide for future practice. Housing and Society. 2013;40(1):1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg D, Cebulla A, Bouchet S. Report on a meta-analysis of Welfare-to-Work programs. Baltimore, MD: Maryland Institute for Policy Analysis and Research; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gubits D, Spellman B, Dunton L, Brown S, Wood M. Interim report: Family options study. Bethesda, MD: Abt Associates, Inc; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gubits D, Khadduri J, Turnham J. Housing patterns of low income families with children: Further analysis of data from the Study of the Effects of Housing Vouchers on Welfare Families. Joint Center for Housing Studies: Harvard University; 2009. http://www.jchs.harvard.edu/sites/jchs.harvard.edu/files/w09-7.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Hoch C. Sheltering the homeless in the US: Social improvement and the continuum of care. Housing Studies. 2000;15(6):865–876. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob BA, Ludwig J. The effects of housing assistance on labor supply: Evidence from a voucher lottery. American Economic Review. 2012;102:272–304. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy S. The final report of the Housing Allowance Demand Experiment. Cambridge MA: Abt Associates, Inc; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy S, Finkel M. Section 8 rental voucher and rental certificate utilization study: Final report. Cambridge MA: Abt Associates, Inc; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson-Spratt K. Housing discrimination and source of income: A tenant’s losing battle. Indiana Law Review. 1999;32:457–480. [Google Scholar]

- Lee ES. A theory of migration. Demography. 1966;3(1):47–57. [Google Scholar]

- Lens MC, Ellen IG, O’Regan K. Do vouchers help low-income households live in safer neighborhoods? Evidence on the Housing Choice Voucher Program. Cityscape. 2011;13(3):135–159. [Google Scholar]

- Lubell JM, Shroder M, Steffen B. Work Participation and length of stay in HUD-assisted housing. Cityscape. 2003;6(2):207–223. [Google Scholar]

- Maguire S, Freely J, Clymer C, Conway M, Schwartz D. Tuning into local labor markets: Findings from the Sectoral Employment Impact Study. Philadelphia PA: Public Private Ventures; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mayberry LS, Shinn M, Benton JG, Wise J. Families experiencing housing instability. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. doi: 10.1037/h0098946. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills G, Gubits D, Orr L, Long D, Feins J, Kaul B, Wood M Amy Jones and Associates, Cloudburst Consulting, & The QED Group. Effects of housing vouchers on welfare families: Final report. Cambridge, MA: Abt Associates, Inc; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi PH. Why families move. 2. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications, Inc; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi PH. Down and out in America: The origins of homelessness. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Sanbonmatsu L, Ludwig J, Katz LF, Gennetian LA, Duncan GJ, Kessler RC, Adam E, McDade TW, Lindau ST. Moving to Opportunity for Fair Housing demonstration program: Final impacts evaluation. 2011 Retrieved from U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development website: http://www.huduser.org/publications/pdf/MTOFHD_fullreport_v2.pdf.

- Shinn M. Ending homelessness for families: The evidence for affordable housing from San Diego Housing Federation website. 2009 http://www.anendinten.org/pdf/file_Ending_Homelessness_for_Families.pdf.

- Shinn M, Weitzman BC, Stojanovic D, Knickman JR, Jimenez L, Duchon L, James S, Krantz DH. Predictors of homelessness among families in New York City: From shelter request to housing stability. American Journal of Public Health. 1998;88:1651–1657. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.11.1651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon HA. A behavioral model of rational choice. The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 1955;69:99–118. [Google Scholar]

- Simon HA. Rational choice and the structure of the environment. Psychological Review. 1956;63:129–138. doi: 10.1037/h0042769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spellman B, Khadduri J, Sokol B, Leopold J. Costs associated with first-time homelessness for families and individuals. Bethesda MD: Abt Associates, Inc; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sterken K. A different type of housing crisis: Allocating costs fairly and encouraging landlord participation in Section 8. Columbia Journal of Law and Social Problems. 2009;43:215–243. [Google Scholar]

- Stojanovic D, Weitzman BC, Shinn M, Labay LE, Williams NP. Tracing the path out of homelessness: The housing patterns of families after exiting shelter. Journal of Community Psychology. 1999;27:199–208. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss AL, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1990. Axial coding; pp. 96–115. [Google Scholar]

- Urban Institute, Abt Associates, and Cloudburst Consulting Group. Prevention programs funded by the Homelessness Prevention and Rapid Rehousing Program. 2013. Final Report to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) The 2010 Annual Homeless Assessment Report to Congress. 2010 Retrieved from U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development website: https://www.onecpd.info/resources/documents/2010HomelessAssessmentReport.pdf.

- U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) The 2011 Annual Homeless Assessment Report to Congress. Office of Community Planning and Development; 2012. https://www.onecpd.info/resources/documents/2011AHAR_FinalReport.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Wong YI, Culhane DP, Kuhn R. Predictors of exit and reentry among family shelter users in New York City. Social Services Review. 1997;71:441–462. [Google Scholar]

- Wood M, Turnham J, Mills G. Housing affordability and family well-being: Results from the housing voucher evaluation. Housing Policy Debate. 2008;19:367–412. [Google Scholar]