Abstract

More than one-third of the world's population is infected with one or more helminthic parasites. Helminth infections are prevalent throughout tropical and subtropical regions where malaria pathogens are transmitted. Malaria is the most widespread and deadliest parasitic disease. The severity of the disease is strongly related to parasite density and the host's immune responses. Furthermore, coinfections between both parasites occur frequently. However, little is known regarding how concomitant infection with helminths and Plasmodium affects the host's immune response. Helminthic infections are frequently massive, chronic, and strong inductors of a Th2-type response. This implies that infection by such parasites could alter the host's susceptibility to subsequent infections by Plasmodium. There are a number of reports on the interactions between helminths and Plasmodium; in some, the burden of Plasmodium parasites increased, but others reported a reduction in the parasite. This review focuses on explaining many of these discrepancies regarding helminth-Plasmodium coinfections in terms of the effects that helminths have on the immune system. In particular, it focuses on helminth-induced immunosuppression and the effects of cytokines controlling polarization toward the Th1 or Th2 arms of the immune response.

1. Introduction

Currently, it is estimated that approximately one-third of the almost three billion people who live on less than two US dollars per day are infected with one or more helminths [1]. Human infections with these organisms remain prevalent in countries where the malaria parasite is also endemic [2]. Consequently, coinfections with both parasites occur frequently [3, 4]. These interactions could have potential fitness implications for both the host (morbidity and/or mortality) and the parasite (transmission). Several studies have shown that the ability of a parasite to successfully establish an infection will depend on the initial immune response of the exposed host [5, 6]. When entering the host, a parasite will experience an “immune environment” potentially determined by both previous and current infections [7–9]. It is widely recognized that, in the presence of Th2 effector response, Th1 response is suppressed and vice versa [10]. Thus, Th2-type response evoked in response to helminth infection would in theory have the ability to suppress proinflammatory Th1 response that generates immunopathology in Plasmodium infection.

Despite the fact that helminth parasites cause widespread, persistent human infection that results in a Th2 immune response, the influence of helminths on the duration of episodes of malaria in humans is not clear. The questions of how the coexistence of helminths and Plasmodium parasites within the same host might influence the immunological responses to each species and whether interactions affect resistance, susceptibility, and the clinical outcome of malaria has yet to be answered.

In this review, we attempt to answer these questions and particularly address whether the preexistence of a Th2/T regulatory response induced by helminths could affect the immune response against Plasmodium.

Before analyzing the influence of helminths infection on malaria, we must first briefly outline the immune response to Plasmodium infection and later outline the immune response to helminths parasites, as this is important to subsequent analyses of how malaria can be modified by the helminths.

2. Plasmodium

Malaria is caused by protozoan parasites belonging to the genus Plasmodium; it is transmitted by female Anopheles mosquitoes. Plasmodium is still one of the most successful pathogens in the world and is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in tropical countries. Five species of Plasmodium (i.e., P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. malariae, P. ovale, and P. knowlesi) are responsible for all human infections [11, 12].

Plasmodium parasites have a complicated, multistage lifecycle involving an Anopheline mosquito vector and a vertebrate host. The parasite develops in two stages in its human host: in the liver (the exoerythrocytic stage) and in the blood (the intraerythrocytic stage). The most characteristic features of malaria in humans are a fever that occurs every 48 to 72 h depending on the species of Plasmodium, chills, headache, and gastrointestinal symptoms. In a naive, untreated individual, these can rapidly escalate into cerebral malaria (CM), anemia, severe organ failure, and death [13].

2.1. Immune Response during Plasmodium Infection

The immune response to Plasmodium is poorly understood; it depends on the parasite species and the specific stage within the host [12]. In addition, it is dichotomized into the preerythrocytic response, which is directed against the sporozoite and liver-stage parasites, and the blood stage response, which is directed against merozoites and intraerythrocytic parasites.

Although animal models do not fully replicate human malaria, they are invaluable tools for elucidating immune processes that can cause pathology and death [14]. Several mouse strains have been used to study the immune response to different combinations of Plasmodium species, such as P. berghei [15–20], P. yoelii [15, 21–24], P. chabaudi [25–30], and P. vinckei [31] (Table 1). These malarial models suggest that the efficiency of parasite control requires both a humoral and a cellular immune response, most likely in cooperation, although the importance of each is not entirely clear. For example, immunity to the sporozoite depends on antibodies to surface proteins, such as CSP-2 [32, 33] and liver-stage antigen (LSA-1) [34]; these antigens induce the production of antibodies that neutralize or block the invasion of hepatocytes [35]. Once sporozoites have entered the hepatocyte, the parasite clearance in mice requires CD8+ T cells [36], natural killer cells (NK), and NKT and γ δ T cells that produce IFN-γ to eliminate infected hepatocytes [35]. When the parasite invades red blood cells (RBC), it dramatically alters the physiological and biochemical processes of its host cell. Parasite-infected RBCs (pRBC) express parasite-encoded molecules on their surface that affects the RBCs' mobility and trafficking within the body. The parasite biomass increases very rapidly and activates innate immune mechanisms, including NK cells and γ δ T cells [13].

Table 1.

Mouse models of malaria infection. ECM: experimental cerebral malaria, PvAS: P. vinckei petteri arteether sensitive, PvAR: P. vinckei arteether resistant, Py: P. yoelii, and KO: knockout.

| Species | Subspecies: clone | Mouse strain and anemia | Mouse strain and CM | Useful in research | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. berghei | P. berghei ANKA | C57BL/6: lethal CD-1: lethal C57BL/6J: non-lethal BALB/c: lethal |

C57BL/6: susceptible CBA: susceptible BALB/c: resistant |

Used as a model of ECM; there is genetic variation in the development of ECM between inbred strains | [15–17] |

| P. berghei K173 | C57BL/6: lethal | Used to study pathogenesis; differs in some aspects of pathogenesis, indicating the influence of parasite genetic variation | [18] | ||

| P. berghei NK65 | C57BL/6: lethal | Is a murine noncerebral malaria strain; induces a progressive increase in parasitemia, intense hepatic inflammation, and death | [19] | ||

| P. berghei XAT | Spontaneously cleared in immune competent mice | Irradiation-induced attenuated variant from lethal strain Pb NK65; comparison of immune responses induced by these lethal and attenuated parasites lead us to elucidate the mechanisms of protective immunity and pathogenesis | [20] | ||

|

| |||||

| P. yoelii | P. yoelii 17 NXL | BALB/c: non-lethal | Most strains resistant | Used to study immune mechanisms and pathogenesis; Py; line A1 is a mild line which is restricted to reticulocytes | [15] |

| P. yoelii 17XL | BALB/c: lethal C57BL/6: lethal |

Most strains susceptible |

Used to identify vaccine-induced immune response | [21, 22] | |

| P. yoelii YM | CBA: lethal | Py-YM is virulent infection which multiplies in both immature and mature erythrocytes | [23] | ||

| P. yoelii YA | CBA: non-lethal | YM parasites are responsible for normocyte invasion, increased virulence compared to mild line Py YA parasites; lines YM and A/C differed additionally in enzyme and drug-sensitivity markers | [24] | ||

|

| |||||

| P. chabaudi | P. chabaudi AS | A/J: lethal C57BL/6: non-lethal BALB/c: non-lethal |

C57BL/6 IL-10KO: susceptible |

Used to study immune mechanisms and immunoregulation by cytokines, to identify susceptibility loci, and to study the immune basis of pathology | [25–28] |

| P. chabaudi AJ | BALB/c: non-lethal | Used to study experimental vaccines and immunological processes that control hyperparasitaemia | [25, 27] | ||

|

P. chabaudi

adami DS |

C3H: lethal C57BL/6: non-lethal |

Is fast-growing and high pathogenicity, induces more anemia, weight loss, and is less infective to mosquitoes than DK strain | [29, 30] | ||

|

P. chabaudi

adami DK |

BALB/c: non-lethal C3H: non-lethal |

Is slower growing and less pathogenic and more selective in its invasion of subset of RBCs than DK | [29, 30] | ||

|

| |||||

| P. vinckei | P. vinckei vinckei | BALB/c: lethal AKR: lethal |

Used to study pathogenesis and for chemotherapy studies; it causes aggressive, overwhelming hyperparasitaemia | [31] | |

| P. vinckei petteri | AKR: lethal (PvAS) AKR: non-lethal (PvAR) |

Used for drug screening and immunological studies | [31] | ||

NK cells play an important role in restricting parasite replication. The absence of NK cells is associated with low IFN-γ serum levels and increased parasitemia in mice infected with P. chabaudi [37]. Likewise, the absence of IFN-γ reduces the ability of mice to control and eliminate parasites, eventually resulting in the death of the animals [38, 39]. Interestingly, macrophages (Mφ), but not IFN-γ, play a major role in the control of early peaks in lethal infections with P. yoelii [40]. In addition, IFN-γ produced by CD4+ T cells plays a pivotal role in protective immunity against non-lethal strains of Plasmodium [41, 42]. In contrast, the infection with P. berghei ANKA induces high levels of IFN-γ and TNF-α which are associated with cerebral malaria [43]. However, the peak of parasitemia in athymic mice tends to be similar to the peak in WT mice. These results suggest that extrathymic T cells are the major lymphocyte subset associated with protection against malaria [44].

In a resistant strain of mice, the presence of the parasite induces the production of proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and IFN-γ. Furthermore, IL-12 is also necessary for elimination of P. chabaudi AS [45], P. berghei XAT [20], and P. yoelii XNL [46].

Besides, the inflammatory cytokine MIF (macrophage migration inhibitory factor) induces pathogenesis and susceptibility on BALB/c mice infected with P. chabaudi, high serum levels of MIF correlated with severity of disease [47]. In addition, infection of MIF knockout mice with P. chabaudi increases survival [48].

CD4+ T cells, together with B cells, are crucial to develop efficient protection in murine experimental models [49, 50]. Whereas IFN-γ, produced by TCD4+, activates Mφ-mediated responses [51], the antibodies produced by B cells inhibit invasion of RBCs by the parasites [52], opsonize parasitized RBCs, block pRBC adhesion to the vascular endothelium, and neutralize parasite toxins [35]. In addition, mice rendered B cell deficient by treatment with anti-μ antibodies or B cell knockout mice (μMT) are unable to clear the erythrocytic infection of P. chabaudi [50, 53, 54]. Specifically, the early acute infection is controlled to some extent, giving rise to chronic relapsing parasitemia that cannot be cleared. Finally, parasitemia can be reduced by adoptive transfer of B cells [50].

Antibodies also induce pathology due to parasite antigens that are freed and adhere to healthy erythrocytes; this generates anemia or autoimmune reactions that cause damage to the kidneys and other tissues [55–58]. For example, pathogenesis of malaria nephropathy is linked to subendothelial deposits of immune complexes containing IgG and IgM [59, 60]. The antibodies involved in the elimination of the parasite mainly belong to cytophilic subclasses (IgG1 and IgG3) [50, 61]. In addition, high levels of immunoglobulin E (IgE) correlate with protection against severe malaria [62–64].

Interestingly, after the peak of parasitemia, cellular immune responses should switch from Th1- to Th2-type response in P. chabaudi infected mice [65], because the malaria pathogenesis is caused by inappropriate or excessive inflammatory responses to eliminate the parasite [43, 66].

Interestingly, Plasmodium can modulate the response of antigen presenting cells, such as Mφ and dendritic cells (DC), which leads to suppression of the immune response [67]. In the infection with P. yoelii YM, the DC function is affected by the presence of TNF-α [68]. Wykes et al. suggested that damage to the activity of DCs is due to a virulence factor that is present in certain parasite strains because, when DCs were transferred from mice infected with a “nonlethal” strain to mice infected with a “lethal” parasite strain, the mice were protected [46].

The regulatory T cells are extremely important to control the inflammatory process in malaria, the number of CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells (Treg) increases in mice infected with P. yoelii [69] or P. berghei [70]. In addition, mice infected with the lethal P. yoelii XL17 show higher levels of IL-10 and TGF-β compared to mice infected with the nonlethal strain P. yoelii XNL, at early time points during infection [71]. Furthermore, the suppression of T cells induces lethality in mice infected with P. yoelii, while neutralization of TGF-β and IL-10 decreases parasitemia and prolongs the survival of infected mice [71, 72]. Accordingly, Couper et al. reported that the main sources of IL-10 in lethal infection with P. yoelii are Treg cells [73]. Finally, the ablation of Treg cells from P. yoelii-infected DEREG-BALB/c mice significantly increases T cell activation and decreases parasitemia [74]. In addition, in mice infected with nonlethal strains of P. yoelii, the presence of cytokines such as IL-10 and TGF-β during the chronic phase of infection was detected [71]. Thus, these data together suggest that the outcome of malaria infection could be determined by the balance of proinflammatory and regulatory immune responses, which could inhibit pathology (Figure 1).

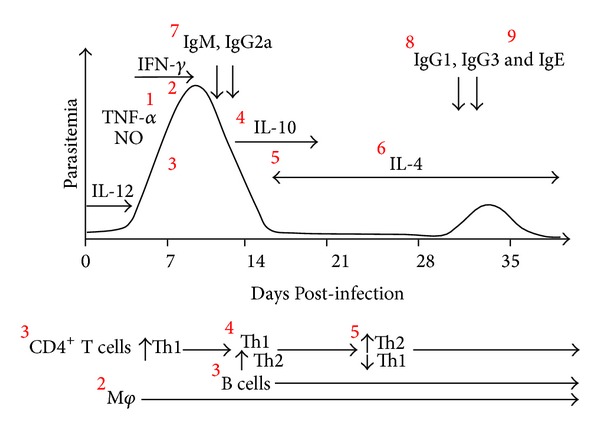

Figure 1.

Representation of the course of Plasmodium chabaudi infection. Early infection with the erythrocytic stage is characterized by the production of proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-12 and TNF-α, and a pronounced IFN-γ response. In addition, NO produced by Mφ helped control parasitemia (1). IFN-γ activates Mφ-mediated responses, in particular phagocytosis and elimination of pRBC (2). CD4+ T cells, together with B cells, are crucial for developing efficient protection (3). Th1 production is downregulated later by an increased Th2-type immune response following primary infection (4). In a later stage of infection, after the peak parasitemia has been reached, CD4 T cells switch from a Th1 to a Th2 cytokine profile (5). This switch helps B cells produce antibodies (6). The antibodies inhibit the invasion of RBCs by the parasites, opsonize parasitized RBCs, or block pRBC adhesion to the vascular endothelium (7, 8). The slow late switch from noncytophilic (IgM and IgG2a) (7) to cytophilic subclasses (i.e., IgG1 and IgG3) (8) is involved in parasite elimination (9). However, IgE correlates with protection against severe malaria. Figure modified from Langhorne et al. 2004 [75] and Stevenson and Urban 2006 [67].

3. Helminths

Helminths are multicellular worms, some of which have adapted successfully to a parasitic lifestyle. They can be classified into three taxonomic groups: cestodes (e.g., Taenia solium), nematodes (e.g., Ascaris lumbricoides), and trematodes (e.g., Schistosoma mansoni). Helminths vary in their biology in terms of size, lifecycle, and the diseases they cause. However, despite this complexity, helminths usually cause asymptomatic and chronic infections [76]. Helminths are among the most widespread infectious agents in human populations, especially in developing countries; they affect more than a third of the world's population, and more than 20 species infect humans (Table 2) [1, 77–83].

Table 2.

Prevalence of common helminths in the world. These are estimates of the number of people with active infections. The number of people potentially exposed or with subclinical helminthic infections is much higher.

| Helminth | Estimated number of infected people | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nematodes | Ascaris lumbricoides | 1450 billion | [77] |

| Trichuris trichiura | 1050 million | [77] | |

| Ancylostoma duodenale | 740 million | [78] | |

| Trichinella spiralis | 600 million | ||

| Necator americanus | 576 million | [1] | |

| Brugia malayi | 157 million | [1] | |

| Wuchereria bancroftiand Brugia malayi | 120 million | [79] | |

| Strongyloides stercoralis | 100 million | [80] | |

| Onchocerca volvulus | 37 million | [81] | |

| Loa loa | 13 million | [1] | |

|

| |||

| Trematodes | Schistosoma spp. | 207 million | [82] |

| Fasciola hepatica | 17 million | ||

|

| |||

| Cestodes | Taenia spp. | 0.4 million | [81] |

| Hymenolepis nana | 75 million | ||

| Echinococcus spp. | 2–3.6 million | [83] | |

3.1. Immune Response during Helminth Infections

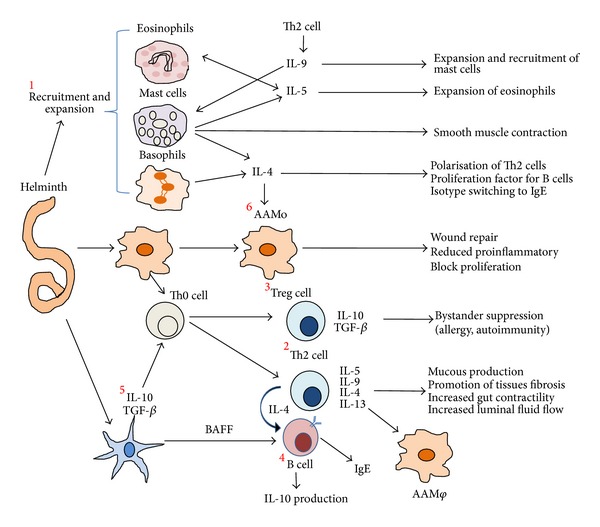

Infection of mammals by helminth parasites typically results in a conserved series of immune events that are orchestrated and dominated by T helper cell type (Th2) events, characterized by the activation of eosinophils, basophils, and mast cells; high levels of immunoglobulin E (IgE); and the proliferation of T cells that secrete IL-4, IL-5, IL-9, and IL-13 [84, 85]. Despite this response, helminths are able to modulate and suppress the host immune response to promote their own survival and their persistence in the host for a long time, resulting in chronic infection [76, 86, 87]. These mechanisms include the ability to induce regulatory responses via regulatory T cells (Treg) which express molecules that inhibit the immune response, such as glucocorticoid-induced TNF-R-related protein (GITR) and the receptor cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4) [88–91]. Treg cells also secrete suppressive cytokines, such as IL-10 and TGF-β [92]. On the other hand, B regulatory cells (Breg) also contribute to immune modulation and can release IL-10 and restrict proinflammatory responses [93]. Helminths also induce the differentiation of anti-inflammatory Mφ, called alternatively activated Mφ (AAMφ) [94, 95], as well as regulatory dendritic cells (DCreg), which are characterized by the expression of the regulatory cytokines IL-10 and TGF-β [96, 97] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Helminth infections are strong inducers of a Th2-type immune response. These infections are characterized by the expansion and activation of eosinophils, basophils, and mast cells (1). Their upregulation due to high levels of immunoglobulin E (IgE) and the proliferation of T cells that secrete IL-4, IL-5, IL-9, and IL-13 are part of the host immune response against the parasite (2). However, helminth infections tend to be long-lived and largely asymptomatic because helminth infections are sustained through a parasite-induced immunomodulatory network, in particular through activation of regulatory T cells (3) and systemically elevated levels of IL-10 produced by B regulatory cells (4). They are additionally affected by the expression of the regulatory cytokines IL-10 and TGF-β, produced by regulatory dendritic cells (5) and alternatively activated Mφ (AAMφ) (6).

This anti-inflammatory or regulatory response could be potentially detrimental to the host if it interferes with the development of protection against other infections that require an inflammatory response, such as Leishmania major [9, 98] or Trypanosoma cruzi [8].

The hyporesponsive immune response induced during chronic helminth infection affects not only the response to helminth antigens but also to other antigens. Several studies have examined the effect of infections on the immune response to other unrelated antigens. In particular, it has been shown that the response to vaccines can be modified by the presence of concomitant helminth infection. For example, chronic Onchocerca infection [99], Lymphatic filariasis [42], or Schistosoma [100] reduces the effectiveness of the tetanus vaccine. Likewise, chronic Onchocerca infection affects Bacillus Calmette-Guérin and Rubella vaccinations [101]. Similarly, Ascaris lumbricoides reduces the response to the oral cholera vaccine, which can be restored by albendazole treatment [102]. However, helminthic infections are beneficial in the control of excessive inflammatory reactions, such as Crohn's disease [103] and ulcerative colitis [104], as well as in allergic diseases [105–107] and autoimmune diseases, such as encephalomyelitis [108, 109] and arthritis [110].

Despite the widespread acceptance that helminthic infections influence each other directly or indirectly, little attention has been paid to helminth-Plasmodium coinfections. One reason is that the interactions involved are complex and difficult to understand. Here, we will try to discuss several reports about helminth-malaria coinfections to clarify the consequences of this interaction.

4. Human Plasmodium-Helminth Coinfection

Plasmodium spp. infect between 349 and 552 million people and kill over one million each year; approximately 40% of the world's population is at risk of being infected [2, 111]. Importantly, people living in malaria-endemic regions are exposed to other pathogens, especially those associated with poverty, such as helminths.

Several studies have been carried out to explore the influence of helminths on Plasmodium infection in humans (Table 3). However, the evidences described in these researches are controversial. While some studies have reported that helminth infection favors protection because reduces the Plasmodium parasite density [112], promotes protection against clinical malaria [113, 114], reduces anemia [113, 115, 116], cerebral malaria [117] and renal failure [118] (Table 3(a)). Other studies showed no influence of helminths on the curse of Plasmodium infection [119–121] (Table 3(b)). In contrast, others showed an increased susceptibility to Plasmodium infection [114, 122], increased risk of complications [123–125], anemia [125, 126], hepatosplenomegaly [127, 128], and increased Plasmodium parasite load [129, 130] (Table 3(c)).

Table 3.

Human studies of coinfection. ARF: acute renal failure, MSM: moderately severe malaria, S: Schistosoma, A: Ascaris, and T: Trichuris.

(a).

| Study area | Age of group | Sample (size) | Study design | Helminth type | Outcome for malaria diseases in coinfection | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Senegal (Niakhar) |

Children | 178 | Over a 2-year followup period |

S. haematobium | Children with a light S. haematobium infection presented lower P. falciparum parasite densities than children not infected by S. haematobium | [112] |

| Mali (Tieneguebougou and Bougoudiana) |

Children and young adults | 62 | Followed prospectively through a malaria transmission season |

Wuchereria bancrofti

Mansonella perstans |

Pre-existent filarial infection attenuates immune responses associated with severe malaria and protects against anemia, but has little effect on susceptibility to or severity of acute malaria infection | [113] |

| Southern Ethiopia |

1 to 82 years Mean 18.6 years |

1,065 febrile patients | Cross-sectional |

A. lumbricoides

T.trichiura, S. mansoni, and hookworm |

The chance of developing non-severe malaria were 2.6–3.3 times higher in individuals infected with helminth, compared to intestinal helminth-free individuals The odds ratio for being infected with non-severe P. falciparum increased with the number of intestinal helminth species |

[114] |

| South-central Côte d'Ivoire |

Infants (6–23 months), children (6–8 year), and young women (15–25 years) |

732 subjects | Cross-sectional survey | Soil-transmitted helminth | Coinfected children had lower odds of anemia and iron deficiency. Interaction between P. falciparum and light-intensity hookworm infections vary with age. |

[115] |

| Brasil (Careiro) | School children 5 to 14 years |

236 | Cohort and cross-sectional |

A. lumbricoides

hookworm and T. trichiura |

Helminthes protect against hemoglobin decrease during an acute malarial attack by Plasmodium. | [116] |

| Thailand (Bangkok) |

Mean 24 years (range 15–62) |

537 files | Retrospective case-control | A. lumbricoides | Percentage protection for mild controls against cerebral malaria ranged from 40% for Ascaris (present/absent) to 70% for Ascaris medium infection. For intermediate controls protection against cerebral malaria was 75% for Ascaris (present/absent). | [117] |

| Thailand (Bangkok) |

19–37 years 22 patients with malaria-associated ARF and 157 patients with MSM |

179 | Retrospective case-control |

A. lumbricoides, T. trichiura, hookworm, and Strongyloides

stercoralis |

Helminths were associated with protection from renal failure Helminth-infected controls were less likely to have jaundice or to have peripheral mature schizonts than controls without helminths |

[118] |

(b).

| Study area | Age of group | Sample (size) | Study design | Helminth type | Outcome for malaria diseases in coinfection | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kenya (Kingwede) | 8 years and older | 561 | cross-sectional | S. haematobium | Children had 9.3 times the odds of coinfection compared to adults |

[119] |

| Nigeria (Osun) |

preschool children (6–59 months) |

690 | Double-blind and randomized | A. lumbricoides | There was no significant difference in the severity of anaemia. | [120] |

| Kabale, Uganda |

All ages (856) | 856 | Retrospective; 18 months |

A. lumbricoides, T. trichiura, and hookworm | Non evidence for an association and risk of malaria | [121] |

(c).

| Study area | Age of group | Sample (size) | Study design | Helminth type | Outcome for malaria diseases in coinfection | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Senegal (Niakhar and Bambey) | Children, mean 6.6 years | 105 | Prospective case-control | A. lumbricoides | Prevalence of A. lumbricoides infection was higher in cases of severe malaria | [123] |

| Northern Senegal |

Children aged 6–15 years | 512 | Cohort | S. mansoni | The incidence rate of malaria attacks was higher among S. mansoni-infected individuals carrying the highest worm loads. In contrast, the rate of malaria attacks were lower in medium grade S. mansoni infections | [124] |

| Ghana (Kumasi) |

Women (15–48 years) mean 26.8 years |

746 | Cross-sectional | A. lumbricoides, T. trichiura, S. stercoralis, and E. vermicularis | Coinfection resulted in increased risks of anemia, low birth weight, and small for gestational age infants | [125] |

| Ethiopia (Alaba Kulito) |

Children <5 years, children 5–14 years, and adults ≥15 years | 1802 acute febrile patients | case-control | Hookworm, A. lumbricoides, and T. trichiura |

Coinfection is associated with higher anaemia prevalence and low weight status than single infection with Plasmodium in children | [126] |

| Kenya (Makueni) |

Primary school children 4–17 years |

(221 and 228) | Cross-sectional | S. mansoni | Hepatosplenomegaly due to proinflammatory mechanism exacerbated by schistosomiasis | [127] |

| Kenya (Mangalete) | Children 4–17 years |

79 | Cross-sectional | S. mansoni | Hepatosplenomegaly is associated with low regulatory and Th2 response to Schistosome antigens | [128] |

| Zimbabwe (Burma Valley) | Children 6–17 years | 605 | 12-month followup of a cohort of children | Schistosome | Increased prevalence of malaria parasites and had higher sexual stage malaria parasite in children coinfected with schistosomiasis | [129] |

| Cameroon (Bolifamba) |

9 months to 14 years | 425 children |

A. lumbricoides, T. trichiura, and hookworm |

Coinfections in which heavy helminth loads showed high P. falciparum parasite loads compared with coinfections involving light helminth burden | [130] |

Although a Th2 phenotype is a conserved response to helminth infection in human and mice, the nature of the host immune response varies considerably between species of helminths; in some cases Th1 immune response predominates, depending on both the time of infection and the helminth development stage [131, 132]. The time that Th1 immune response is sustained until it polarizes toward Th2, could vary between species [133–135]. Thus, the controversial results related to helminth-Plasmodium coinfection in humans could be explained because many studies did not consider critical features of the helminth parasite biology. For example, the biological niche or parasite stage within the host. Neither the previous time of infection with the helminth nor the nutrition state and age of the host were taken into account.

Because all of these variables were not considered in existing studies in humans and in order to establish a possible consensus, we review in detail the murine Plasmodium-helminth coinfections, which in theory, controlled variables more rigorously.

5. Experimental Models of Coinfection

Although helminth infections in mice are a questionable model for chronic helminth infections in humans, the fact is that many intraintestinal helminths can reach large biomass which can change the cytokine environment and therefore the possible mechanisms of response. By establishing chronic infections and inducing strong Th2-type responses, helminths could have a potentially significant influence on the nature of the immune response in infected individuals and hence modify their susceptibility to subsequent infections with other important pathogens, at least those that require a Th1-type or mixed Th1-/Th2-type immune response, such as Plasmodium sp.

5.1. Schistosoma-Plasmodium Coinfection

According to the theory that Th2-type response evoked in response to helminth infection would have the ability to suppress proinflammatory Th1 response that generates immunopathology in Plasmodium-infected individuals, there are some reports of experimental models of coinfection with Plasmodium berghei ANKA (Pb) after Schistosoma mansoni (Sm) infection in ICR mice or with Schistosoma japonicum- (Sj-) Pb in C57BL/6 mice 7 or 8 weeks after helminthic infection, respectively; both coinfections showed a delay in death of mice [136, 137]. Interestingly, there was a reduction in the brain pathology associated with high levels of the anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-5, IL-10, and IL-13 [136–138].

In contrast, similar coinfection with Pb 7 or 8 weeks after Sm infection showed an increase in mortality and parasitemia in Swiss albino and C57BL/6 mice [138, 139]. Moreover, the coinfections in Swiss albino mice reduced the effectiveness of antimalarial treatments and delayed elimination of the parasite [139] (Table 4(a)). In these reports neither evidence of immune response nor pathology data were shown. Thus, we speculate that increase parasite load was probably due to the presence of helminth than inhibited Th1-type immune response which was able to contain the replication of Plasmodium, and the increased mortality was due to parasite load rather than a pathological Th1-state dependent. In line with this hypothesis, coinfection with Plasmodium chabaudi (Pc) at 8 weeks after Sm infection in C57BL/6 mice allowed high Pc replication. This increase was associated with low levels of the proinflammatory TNF-α [140].

Table 4.

Helminthic infection drives immune response to challenge with Plasmodium. *The time after helminth infection when the Plasmodium challenge was performed. ND: nondetermined, wks: weeks, KO: knockout, ECM: experimental cerebral malaria.

(a).

| Background mouse | Plasmodium strain | Helminth type | Coinfection time* | Malaria disease outcome | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICR HSD |

P. berghei

ANKA |

S. mansoni | 7 wks | Low rates of ECM (30%), delay in death associated with high levels of IL-4, IL-10 | [136] |

| C57BL/6 |

P. berghei

ANKA |

S. japonicum | 8 wks | Increased survival rate and reduction of the brain pathology. Th2 response induced by worm plays an important role in protecting against ECM | [137] |

| C57BL/6 |

P. berghei

ANKA |

S. mansoni | 8-9 wks | Increased parasitemia, mortality, weight loss, and hypothermia; decreased pathology in the brain associated with high levels of IL-5, IL-13 and low serum IFN-γ | [138] |

| Swiss albino |

P. berghei

ANKA |

S. mansoni | 7 wks | Increased parasitemia and mortality Delayed reduction/elimination of the parasite followed by administration of antimalarial treatment |

[139] |

| C57BL/6 | P. chabaudi | S. mansoni | 8 wks | Increased parasitemia associated with a deficiency in the production of TNF-α | [140] |

| BALB/c |

P. yoelii NXL (non-lethal) |

S. mansoni | 2, 4, and 6 wks | Increased parasitemia and death at 6 wks of coinfection. Hepatosplenomegaly was more marked in coinfected mice compared to either disease separately | [141] |

| A/J | P. chabaudi | S. mansoni | 8 wks | Mice escape death and showed high production of IFN-γ | [142] |

(b).

| Background mouse | Plasmodium strain | Helminth type | Coinfection time* | Malaria disease outcome | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C57BL/6 | P. chabaudi | H. polygyrus | 2, 3, or 5 wks | Increased parasitemia and mortality associated with low levels of IFN-γ and high levels of TGF-β, IL-10 | [143] |

| C57BL/6 | P. chabaudi AS | H. polygyrus | 2 wks | Increased parasitemia; however, it ameliorates severe hypothermia and hypoglycaemia; besides this, it induced earlier reticulocytosis than Pc-infected WT mice | [144] |

| C57BL/6 IFN−/− IL-23−/− |

P. chabaudi AS | H. polygyrus | At the same time | Increased mortality and severe liver disease, associated with increased IFN-γ, IL-17, and IL-22 in the liver. The coinfected IFN−/− and IL-23−/− mice survive | [145] |

| C57BL/6 BALB/c |

P. chabaudi AS | H. polygyrus | 2 wks with AgPc + adjuvant |

Suppresses the protective efficacy of the malaria vaccine. Deworming treatment before antimalarial immunization restored the protective immunity to malaria challenge | [146] |

| C57BL/6 | P. yoelii 17 XNL | H. polygyrus | 2 wks | Increased pathology due to reduced response against Py (low levels of IFN-γ) in the spleen cells, as a result of higher activation of Treg | [147] |

| BALB/c |

P. yoelii

17 NXL |

H. polygyrus | 3 wks | Reduction of pathology, low levels of IFN-γ, and high levels of IL-4 induced by helminthes | [148] |

| C57BL/6 | P. berghei ANKA | H. polygyrus | 2 wks | Hp infection did not alter ECM development, despite accelerated P. berghei growth in vivo | [149] |

| C57BL/6 BALB/c | P. berghei ANKA | H. polygyrus | 2 wks | No differences | [150] |

(c).

| Background mouse | Plasmodium strain | Helminth type | Coinfection time* | Malaria disease outcome | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BALB/c | P. yoelii 17 NXL | E. caproni | 3 wks | Ec showed counterregulatory antiparasite cytokine responses to non-lethal strain PyNXL (less IFN-γ and high IL-4 levels induced by Ec) | [148] |

| BALB/c | P. yoelii 17 NXL | E. caproni | 5 wks | Increased mortality and pathology; the pathology was reversible through clearance of Ec by praziquantel treatment | [151] |

| BALB/c | P. yoelii 17XL | E. caproni | 5 wks | Ec does not alter the course of Py17XL infection | [151] |

(d).

| Background mouse | Plasmodium strain | Helminth type | Coinfection time* | Malaria disease outcome | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C57BL/6 | P. yoelii 17NXL | Strongyloides ratti | 1 wk | Did not altered cytokine response | [152] |

| BALB/c | P. berghei ANKA | Strongyloides ratti | 1 wk | The coinfection did not change the efficacy of vaccination against Pb | [153] |

(e).

| Background mouse | Plasmodium strain | Helminth type | Coinfection time* | Malaria disease outcome | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BALB/c | P. chabaudi |

Nippostrongylus

brasiliensis |

Same day | Reduction of anemia and parasitemia. Th2 response was inhibited by Plasmodium | [154] |

| C57BL/6 | P. berghei | Nippostrongylus brasiliensis | 3 wks | Delayed peak parasitemia, increased survival | [155] |

(f).

| Background mouse | Plasmodium strain | Helminth type | Coinfection time* | Malaria disease outcome | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BALB/c | P. chabaudi | L. sigmodontis | 8 wks | Increased severity of the anemia and weight loss associated with increased IFN-γ | [156] |

| C57BL/6 IL-10KO |

P. berghei

(ANKA) |

L. sigmodontis | 8 wks | Reduction of ECM associated with increased IL-10 IL-10KO mice coinfected with Pb-Ls die of ECM |

[157] |

| BALB/c | P. berghei ANKA | L. sigmodontis | 2 wks | Reduced protection against P. berghei challenge infection for low frequencies of CSP-specific CD8 T cells, CSP-specific IFN-γ and TNF-α production | [153] |

(g).

| Background mouse | Plasmodium strain | Helminth type | Coinfection time* | Malaria disease outcome | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBA |

P. berghei

(ANKA) |

Brugia pahangi

irradiated attenuated |

1 wk | Increased survival and protected them against the ECM development; increase synthesis of IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-5, and IgE | [158] |

(h).

| Background mouse | Plasmodium strain | Helminth type | Coinfection time* | Malaria disease outcome | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C57BL/6 | P. berghei | Trichinella spiralis | 1–4 wks | Partially subdued parasitaemia and prolonged survival | [159] |

It is known that the immune response against Schistosoma shifts from an early helminth-protective Th1-type immune response to a late helminth-permissive Th2-type response during the course of infection [134]. Thus, the moment when the second infection is acquired (2, 4 and 6 weeks post-helminth infection) would be critical for disease outcome and pathology [141]. These findings could be supported by the fact that chronically Sm-infected BALB/c mice coinfected (6 weeks) with the nonlethal strain Plasmodium yoelii NXL (PyNXL) showed high mortality. In contrast, no mortality was observed in acutely (2 or 4 weeks) coinfected mice, although they developed high parasitemia and hepatomegaly was higher in coinfected mice compared with mice infected with each parasite separately [141] (Table 3(a)). Therefore, the time of previous infection may influence the response against Plasmodium.

Together, these reports suggested that the Th2 response, induced by Schistosoma, plays an important role in protecting against immunopathology in cerebral malaria. However, the presence of Schistosoma does not appear to modify the virulence of Pb and, consequently, it does not alter the lethality of Plasmodium infection.

Finally, one report scape to the theory that Th2-type immune response evoked by the helminth infection would possess the ability to suppress the proinflammatory Th1-type response in its host. Sm-infected A/J mice coinfected at 8 weeks with Pc were protected by the presence of concomitant Sm infection. The mice escaped death due to malaria; this effect was accompanied by enhanced levels of IFN-γ [142] (Table 4(a)).

5.2. Heligmosomoides polygyrus-Plasmodium Coinfection

Several studies used mice of the same genetic background. Additionally, equivalent helminth and Plasmodium strains have been used to explain whether previous helminthic infection plays an important role in the immune response against Plasmodium. Su et al. showed that C57BL/6 mice previously infected with Heligmosomoides polygyrus (Hp) and challenged with Pc either 3 or 5 weeks after helminthic infections developed high Pc-parasitemia and mortality, which was associated with low levels of IFN-γ and high levels of TGF-β and IL-10 [143]. However, Hp-Pc coinfection at 2 weeks resulted in less severe pathology (i.e., less hypothermia and hypoglycemia) and induced earlier reticulocytosis compared with mice infected only with Pc [144] (Table 4(b)).

Helmby in 2009 showed that mice developed high mortality in the Hp-Pc model when the two infections were introduced simultaneously. The mortality was due to severe liver pathology associated with increased IFN-γ, IL-17, and IL-22. Interestingly, when using an IFN-γ and IL-23 knockout strain, the mice survived the coinfection [145]. Thus, simultaneous Hp-Pc coinfection increased mortality, which may be a consequence of a synergistic effect that increased the inflammatory response (Table 4(b)).

In fact, in the first case, in which Hp-Pc coinfection was performed at 3 or 5 weeks after the initial helminthic infection, the high mortality observed may have been due to the anti-inflammatory response generated by the previous helminthic infection, which inhibited the inflammatory response necessary for control of the Plasmodium infection. However, when the coinfection was performed at the same time, mice developed a stronger inflammatory response, which generated greater pathology and mortality. This susceptibility is supported by the observation that chronic helminthic infection suppresses effective vaccine-induced protection against Plasmodium. However, when mice were administered with antihelminthic Hp treatment before malaria vaccination, the protective immunity against Pc was restored [146]. Therefore, the timing of the infection with Hp plays an important role in the type of immune response that is generated within the host, and it determines the susceptibility following challenge with Plasmodium.

The genetic background of mice infected with helminths has a crucial role in the outcome of the immune response to Plasmodium. For example, coinfection with the nonlethal PyNXL strain at 2 weeks after Hp infection in C57BL/6 mice resulted in exacerbated pathology and poor survival of mice. This susceptibility was associated with a reduced response against PyNXL (i.e., low levels of IFN-γ) in the spleen cells. As a consequence, it increased the activation of Treg cells [147]. However, the same coinfection at 3 weeks in BALB/c mice decreased the pathology associated with low levels of IFN-γ and increased levels of IL-4, but not IL-10 [148]. Therefore, the genetic background of mice infected with the helminth determines the outcome of PyNXL infection (Table 4(b)).

What happens when a lethal strain of Plasmodium was used in coinfection with Hp? The Pb ANKA infection in C57BL/6 mice induced typical symptoms of ECM [160, 161]. Coinfection with Hp-Pb ANKA 2 weeks after initial helminthic infection did not modify the development of ECM despite accelerated Pb growth in vivo [149]. Likewise, other results from the same model of coinfection in BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice showed no differences in parasitemia, anemia, or body weight in relation to mice infected only with Plasmodium [150]. Therefore, Hp infection does not affect the outcome of Pb ANKA (Table 4(b)).

5.3. Echinostoma caproni-Plasmodium Coinfection

Studies in BALB/c mice infected for 3 weeks with E. caproni (Ec) and then coinfected with the nonlethal strain PyNXL showed that exacerbation of Plasmodium-induced pathology was associated with a deficit in IFN-γ production [148]. Similarly, when Ec-infected mice were coinfected at 5 weeks, increased mortality was observed. The exacerbated pathology was reversible through the clearance of Ec worms via praziquantel treatment [151]. However, coinfection at 5 weeks with the lethal PyXL strain did not alter the course of infection; all mice infected with PyXL (i.e., alone, in combination with E. caproni, or praziquantel treated) died on day 10 after infection [151] (Table 4(c)). Therefore, Ec infection does not affect the outcome of lethal PyXL, but Ec infection affects the protective response against a nonlethal Plasmodium strain.

5.4. Strongyloides ratti-Plasmodium Coinfection

Murine Strongyloides ratti (Sr) infection is a transient helminthic infection that is resolved spontaneously within 3-4 weeks. This infection induces a strong Th2-type immune response at day 6 after infection [135]. When BALB/c mice were coinfected with the nonlethal strain PyNXL at day 6 after Sr infection, Sr induced a slightly enhanced peak of Plasmodium parasitemia and loss of body weight. In contrast, in C57BL/6 mice coinfected at day 6, parasitemia level and body weight were not altered. Interestingly, the Th2-type immune response induced by Sr was significantly reduced upon PyNXL coinfection [152]. In addition, PyNXL clearance was not affected by previous infection with Sr in either C57BL/6 or BALB/c mice. Moreover, infection with Sr in BALB/c mice did not change the efficacy of vaccination against Pb ANKA [153]. Therefore, infection with Sr does not affect the protective response against Plasmodium, although it generates small changes in parasitemia levels; which is not decisive for the outcome of Plasmodium infection (Table 4(d)).

5.5. Nippostrongylus brasiliensis-Plasmodium Coinfection

BALB/c mice infected with Nippostrongylus brasiliensis (Nb) exhibit a strong Th2-type immune response [162]. Even so, when BALB/c mice were coinfected with Nb and Pc simultaneously, the Th2 response against Nb was impaired by Plasmodium. Interestingly, the Nb-Pc coinfection had a beneficial effect; it slightly ameliorated the severity of malarial anemia (SMA) and decreased parasitemia levels [154]. Similarly, C57BL/6 mice infected for 3 weeks with Nb and then coinfected with Pb showed a delayed peak parasitemia and an increased survival time [155]. Thus, the presence of concomitant Nb infection plays an important role in inhibiting pathology associated with a challenge with Pc or Pb (Table 4(e)).

5.6. Coinfection with Other Helminths

Experimental models of coinfection with Litomosoides sigmodontis (Ls) 8 weeks and Pc infection in BALB/c mice showed increased SMA and weight loss associated with increased levels of IFN-γ [156]. In contrast, coinfection with Ls 8 weeks and Pb infection in C57BL/6 mice showed significantly reduced ECM rates associated with increased levels of IL-10. This protection was inhibited in IL-10 KO mice [157]. High levels of IL-10 were important in reducing pathology but also interfered with the protective response to Plasmodium in the liver. In particular, chronic infection with Ls interfered with the protective efficacy of a vaccine against sporozoite Pb in the liver [153]. Therefore, infection with Ls exacerbates the pathology of a Pc infection. In contrast, infection with Ls inhibits pathology in Pb infection due to an anti-inflammatory cytokine response (Table 4(f)).

In addition, CBA/J mice infected with Brugia pahangi (Bp) for 1 week and then coinfected with Pb displayed a low mortality rate, and mice were protected against the development of ECM. This protection was associated with increased serum IgE levels and Th2 cytokine production [158] (Table 4(g)). Similarly, infection with Trichinella spiralis (Ts) for 1 or 4 weeks in C57BL/6 mice greatly enhanced their resistance against the fatal coinfection with Pb [159]. Therefore, these observations suggest that the Th2-type immune response reduces brain pathology and increases survival in Bp- or Ts-Pb coinfection, perhaps due to the anti-inflammatory environment generated by the previous helminth infection (Table 4(h)).

The studies described above lead to different conclusions, while some of them suggest that prior infection with helminths induces resistance to Plasmodium [136, 137, 142, 148, 154, 155, 157–159], other studies do not show effects [149–153] and finally some others demonstrated an increased susceptibility to Plasmodium infection [138–141, 143–148, 151, 153, 156]. These contrasting results may partially be explained because this interaction is affected by the timing between the hosts' exposure to the helminth and Plasmodium. In addition, the strain of each parasite is also important, coinfection with nonlethal Plasmodium strains in the early stages of a helminthic infection delayed the onset of parasitemia due to early, specific high production of IFN-γ, but this response increased pathology. In contrast, a significant increase in susceptibility to nonlethal Plasmodium was observed when mice were coinfected with Plasmodium in the late stages of helminthic infection, when the Th2-type immune response is predominant.

Coinfection with lethal strains of Plasmodium in the late stages of a helminthic infection inhibits severe pathology and increases the survival of mice due to a decrease inflammatory response (mainly IFN-γ and TNF-α). In addition, the presence of a late anti-inflammatory Th2-type immune response induced by helminthic infection extended the survival of mice susceptible to Plasmodium infection; this may be due to a reduced pathological Th1-type immune response or may be due to induction of protective mix of Th1 and Th2 immune response. Recruitment and activation of Mφ are essential for the clearance of malaria infections, but these have also been associated with adverse clinical outcomes [163]. Specifically, immunopathology of severe malaria is often originated from an excessive inflammatory Th1-type immune response. The expansion of Treg cells and the alternative activation of Mφ by helminth infections may modulate the excessive inflammatory response to Plasmodium. Therefore, the chronic helminth infections inhibited pathology and increased survival in the challenge with lethal strains of Plasmodium.

6. Conclusions

The findings in this review demonstrate that the immune environment generated by a previous helminthic infection influences the response against Plasmodium. A helminth that persists in its host is able to significantly modify the host's susceptibility to or protection from Plasmodium. These modifications are dependent on the genetic background of mice, the type of helminth, and the time-course of the initial helminthic infection, which is crucial to the resulting immune response to Plasmodium.

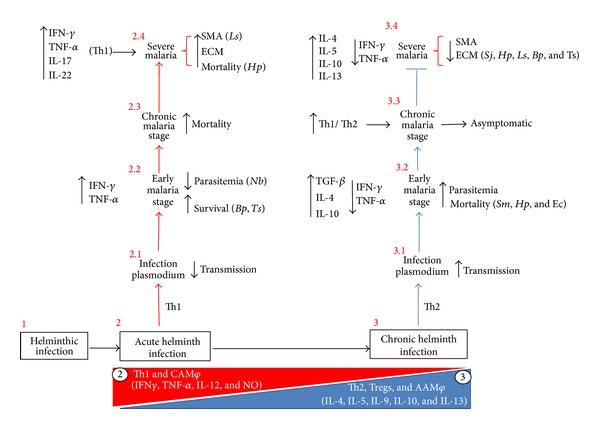

The impact of helminth-Plasmodium coinfection on acute helminthic infection increased or synergized the Th1-type immune response. This might be successful in inducing a response that inhibits Plasmodium replication, but it increases the pathology and mortality in the host. Alternatively, chronically helminth-infected mice showed a shift toward Th2-type immune responses. This could render the host more susceptible to Plasmodium infection and favor their replication; however, this response protected the host from severe malaria (Figure 3). Overall, these results suggest that malarial immunity is influenced by helminth infections. Therefore, the study and manipulation of antimalarial immunity seems difficult in the absence of any information concerning the effects of helminths on this response.

Figure 3.

Concomitant helminth infection modified the immune response and susceptibility to Plasmodium infection. Helminth parasites have developed complicated strategies to infect and successfully colonize their host. (1) In an acute helminth infection, an initial Th1-like immune response (i.e., IFN-γ, IL-12, and classical activation macrophage (CAMφ)) is associated with low parasite growth. (2) However, as the parasite colonizes the host, the immune response rapidly shifts toward a Th2-dominant response (IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, IL-13, and AAMφ) in parallel with increased helminth parasitemia. (3) This “immune environment” determined by helminth infection modifies the immune response and the susceptibility to Plasmodium. That is, acutely helminth-infected mice exhibited (2) decreased transmission of Plasmodium (2.1), decreased parasitemia and increased survival (2.2) due to high levels of IFN-γ and TNF-α in the early stage. However, this immune response increased mortality during the chronic stage of malaria (2.3) and increased severe pathology, such as ECM and severe malaria anemia (SMA) (2.4). In contrast, chronically helminth-infected mice (3) increased the transmission of Plasmodium (3.1), parasitemia and mortality (3.2) due to high levels of IL-4, IL-10, and TGF-β and low levels of IFN-γ and TNF-α. However, during the course of the coinfection, the Th1 response against Plasmodium was increased. In fact, a mixed Th1/Th2 response during the chronic stage induced low levels of parasitemia and was asymptomatic (3.3). Interestingly, chronic helminth infections inhibited severe pathologies caused by Plasmodium, such as ECM and SMA (3.4), and increased the survival due to a decreased inflammatory response. Abbreviations: Schistosoma mansoni (Sm), Heligmosomoides polygyrus (Hp), Echinostoma caproni (Ec), Strongyloides ratti (Sr), Nippostrongylus brasiliensis (Nb), Litomosoides sigmodontis (Ls), Brugia pahangi (Bp), and Trichinella spiralis (Ts).

7. Perspectives

The helminth-Plasmodium interaction may have undesirable implications for global public health; for example, malaria vaccines trials do not consider the immune response to helminths, and this could result in decreased performance or cause adverse effects. Thus, a better understanding of helminth-induced regulation in the antimalarial response is indispensable for the rational development of effective antimalarial vaccines and novel therapies to alleviate or prevent the symptoms of severe malaria. The risk that entire populations may have an increased susceptibility to Plasmodium should invite study regarding the possible epidemiological relevance of helminth infections and the impact of controlling them on malaria incidence. The presence of helminth infections could represent a much more important challenge for public health than previously recognized. Therefore, we would emphasize that it is extremely important to carry out experiments in animal models that use more rigorous criteria to define exhaustively all the ramifications of immune regulation and potential side effects of helminth infection in the context of malaria. These results would allow extrapolate the observation in human populations presenting malaria.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Pascal Hérion for critical review of the paper. They also thank CONACYT-México no. 0443480 for supported Ph.D. fellowship for the first author, Víctor H. Salazar-Castañon, to obtain his degree in biomedical sciences, UNAM. This work was supported by Grants 152224 from CONACYT and IN212412 from UNAM-DGAPA-PAPIIT.

Conflict of Interests

The authors have no financial or other conflicts to declare.

References

- 1.Hotez PJ, Brindley PJ, Bethony JM, King CH, Pearce EJ, Jacobson J. Helminth infections: the great neglected tropical diseases. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2008;118(4):1311–1321. doi: 10.1172/JCI34261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hay SI, Okiro EA, Gething PW, et al. Estimating the global clinical burden of Plasmodium falciparum malaria in 2007. PLoS Medicine. 2010;7(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000290.e1000290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mboera LEG, Senkoro KP, Rumisha SF, Mayala BK, Shayo EH, Mlozi MRS. Plasmodium falciparum and helminth coinfections among schoolchildren in relation to agro-ecosystems in Mvomero District, Tanzania. Acta Tropica. 2011;120(1-2):95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brooker S, Akhwale W, Pullan R, et al. Epidemiology of Plasmodium-helminth co-infection in Africa: populations at risk, potential impact on anemia, and prospects for combining control. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2007;77(6):88–98. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Telfer S, Birtles R, Bennett M, Lambin X, Paterson S, Begon M. Parasite interactions in natural populations: insights from longitudinal data. Parasitology. 2008;135(7):767–781. doi: 10.1017/S0031182008000395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Telfer S, Lambin X, Birtles R, et al. Species interactions in a parasite community drive infection risk in a wildlife population. Science. 2010;330(6001):243–246. doi: 10.1126/science.1190333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marshall AJ, Brunet LR, Van Gessel Y, et al. Toxoplasma gondii and Schistosoma mansoni synergize to promote hepatocyte dysfunction associated with high levels of plasma TNF-α and early death in C57BL/6 mice. Journal of Immunology. 1999;163(4):2089–2097. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rodríguez M, Terrazas LI, Márquez R, Bojalil R. Susceptibility to Trypanosoma cruzi is modified by a previous non-related infection. Parasite Immunology. 1999;21(4):177–185. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3024.1999.00218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodríguez-Sosa M, Rivera-Montoya I, Espinoza A, et al. Acute cysticercosis favours rapid and more severe lesions caused by Leishmania major and Leishmania mexicana infection, a role for alternatively activated macrophages. Cellular Immunology. 2006;242(2):61–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matisz CE, McDougall JJ, Sharkey KA, McKay DM. Helminth parasites and the modulation of joint inflammation. Journal of Parasitology Research. 2011;2011:8 pages. doi: 10.1155/2011/942616.942616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeremiah S, Janagond AB, Parija SC. Challenges in diagnosis of Plasmodium knowlesi infections. Tropical Parasitology. 2014;4(1):25–30. doi: 10.4103/2229-5070.129156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stevenson MM, Riley EM. Innate immunity to malaria. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2004;4(3):169–180. doi: 10.1038/nri1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Good MF, Xu H, Wykes M, Engwerda CR. Development and regulation of cell-mediated immune responses to the blood stages of malaria: implications for vaccine research. Annual Review of Immunology. 2005;23:69–99. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hernandez-Valladares M, Naessens J, Iraqi FA. Genetic resistance to malaria in mouse models. Trends in Parasitology. 2005;21(8):352–355. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Asami M, Owhashi M, Abe T, Nawa Y. A comparative study of the kinetic changes of hemopoietic stem cells in mice infected with lethal and non-lethal malaria. International Journal for Parasitology. 1992;22(1):43–47. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(92)90078-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.White NJ, Turner GDH, Medana IM, Dondorp AM, Day NPJ. The murine cerebral malaria phenomenon. Trends in Parasitology. 2010;26(1):11–15. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Engwerda CR, Beattie L, Amante FH. The importance of the spleen in malaria. Trends in Parasitology. 2005;21(2):75–80. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oliveira-Lima OC, Bernardes D, Xavier Pinto MC, Esteves Arantes RM, Carvalho-Tavares J. Mice lacking inducible nitric oxide synthase develop exacerbated hepatic inflammatory responses induced by Plasmodium berghei NK65 infection. Microbes and Infection. 2013;15(13):903–910. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoshimoto T, Takahama Y, Wang C, Yoneto T, Waki S, Nariuchi H. A pathogenic role of IL-12 in blood-stage murine malaria lethal strain Plasmodium berghei NK65 infection. Journal of Immunology. 1998;160(11):5500–5505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoshimoto T, Yoneto T, Waki S, Nariuchi H. Interleukin-12-dependent mechanisms in the clearance of blood-stage murine malaria parasite Plasmodium berghei XAT, an attenuated variant of P. berghei NK65. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1998;177(6):1674–1681. doi: 10.1086/515301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weiss L, Johnson J, Weidanz W. Mechanisms of splenic control of murine malaria: tissue culture studies of the erythropoietic interplay of spleen, bone marrow, and blood in lethal (strain 17XL) Plasmodium yoelii malaria in BALB/c mice. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 1989;41(2):135–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Totino PRR, Magalhães AD, Silva LA, Banic DM, Daniel-Ribeiro CT, Ferreira-Da-Cruz MDF. Apoptosis of non-parasitized red blood cells in malaria: a putative mechanism involved in the pathogenesis of anaemia. Malaria Journal. 2010;9(1, article 350) doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-9-350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Panton LJ, Knowles G, Walliker D. Studies of antigens in Plasmodium yoelii. I. Antigenic differences between parasite lines detected by crossed immunoelectrophoresis. Parasitology. 1984;89(1):17–26. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000001098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jarra W, Brown KN. Protective immunity to malaria: studies with cloned lines of rodent malaria in CBA/Ca mice. IV. The specificity of mechanisms resulting in crisis and resolution of the primary acute phase parasitaemia of Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi and P. yoelii yoelii . Parasite Immunology. 1989;11(1):1–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.1989.tb00644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yap GS, Stevenson MM. Plasmodium chabaudi AS: erythropoietic responses during infection in resistant and susceptible mice. Experimental Parasitology. 1992;75(3):340–352. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(92)90219-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lamb TJ, Langhorne J. The severity of malarial anaemia in Plasmodium chabaudi infections of BALB/c mice is determined independently of the number of circulating parasites. Malaria Journal. 2008;7, article 68 doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-7-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fortin A, Stevenson MM, Gros P. Complex genetic control of susceptibility to malaria in mice. Genes and Immunity. 2002;3(4):177–186. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6363841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanni LA, Jarra W, Li C, Langhorne J. Cerebral edema and cerebral hemorrhages in interleukin-10-deficient mice infected with Plasmodium chabaudi . Infection and Immunity. 2004;72(5):3054–3058. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.5.3054-3058.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Villeval JL, Lew A, Metcalf D. Changes in hemopoietic and regulator levels in mice during fatal or nonfatal malarial infections. I. Erythropoietic populations. Experimental Parasitology. 1990;71(4):364–374. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(90)90062-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gadsby N, Lawrence R, Carter R. A study on pathogenicity and mosquito transmission success in the rodent malaria parasite Plasmodium chabaudi adami. International Journal for Parasitology. 2009;39(3):347–354. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Siddiqui AJ, Bhardwaj J, Puri SK. mRNA expression of cytokines and its impact on outcomes after infection with lethal and nonlethal Plasmodium vinckei parasites. Parasitology Research. 2012;110(4):1517–1524. doi: 10.1007/s00436-011-2656-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sina BJ, Wright C, Atkinson CT, Ballou R, Aikawa M, Hollingdale M. Characterization of a sporozoite antigen common to Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium berghei . Molecular and Biochemical Parasitology. 1995;69(2):239–246. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(94)00198-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Almeida AP, Dias MO, Vieira AAF, et al. Long-lasting humoral and cellular immune responses elicited by immunization with recombinant chimeras of the Plasmodium vivax circumsporozoite protein. Vaccine. 2014;32(19):2181–2187. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.02.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ferraro B, Talbotta KT, Balakrishnana A, et al. Inducing humoral and cellular responses to multiple sporozoite and liver-stage malaria antigens using exogenous plasmid DNA. Infection and Immunity. 2013;81(10):3709–3720. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00180-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Langhorne J, Ndungu FM, Sponaas A, Marsh K. Immunity to malaria: more questions than answers. Nature Immunology. 2008;9(7):725–732. doi: 10.1038/ni.f.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Imai T, Shen J, Chou B, et al. Involvement of CD8+ T cells in protective immunity against murine blood-stage infection with Plasmodium yoelii 17XL strain. European Journal of Immunology. 2010;40(4):1053–1061. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mohan K, Moulin P, Stevenson MM. Natural killer cell cytokine production, not cytotoxicity, contributes to resistance against blood-stage Plasmodium chabaudi AS infection. Journal of Immunology. 1997;159(10):4990–4998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Choudhury HR, Sheikh NA, Bancroft GJ, Katz DR, De Souza JB. Early nonspecific immune responses and immunity to blood-stage nonlethal Plasmodium yoelii malaria. Infection and Immunity. 2000;68(11):6127–6132. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.11.6127-6132.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fortin A, Stevenson MM, Gros P. Susceptibility to malaria as a complex trait: big pressure from a tiny creature. Human Molecular Genetics. 2002;11(20):2469–2478. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.20.2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Couper KN, Blount DG, Hafalla JCR, van Rooijen N, de Souza JB, Riley EM. Macrophage-mediated but gamma interferon-independent innate immune responses control the primary wave of Plasmodium yoelii parasitemia. Infection and Immunity. 2007;75(12):5806–5818. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01005-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Clark IA, Hunt NH, Butcher GA, Cowden WB. Inhibition of murine malaria (Plasmodium chabaudi) in vivo by recombinant interferon-γ or tumor necrosis factor, and its enhancement by butylated hydroxyanisole. The Journal of Immunology. 1987;139(10):3493–3496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kobayashi F, Morii T, Matsui T, et al. Production of interleukin 10 during malaria caused by lethal and nonlethal variants of Plasmodium yoelii yoelii . Parasitology Research. 1996;82(5):385–391. doi: 10.1007/s004360050133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hunt NH, Grau GE. Cytokines: accelerators and brakes in the pathogenesis of cerebral malaria. Trends in Immunology. 2003;24(9):491–499. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(03)00229-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mannoor MK, Halder RC, Morshed SRM, et al. Essential role of extrathymic T cells in protection against malaria. Journal of Immunology. 2002;169(1):301–306. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.1.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Su Z, Stevenson MM. IL-12 is required for antibody-mediated protective immunity against blood-stage Plasmodium chabaudi AS malaria infection in mice. Journal of Immunology. 2002;168(3):1348–1355. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.3.1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wykes MN, Liu XQ, Beattie L, et al. Plasmodium strain determines dendritic cell function essential for survival from malaria. PLoS Pathogens. 2007;3(7, article e96) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Martiney JA, Sherry B, Metz CN, et al. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor release by macrophages after ingestion of Plasmodium chabaudi-infected erythrocytes: possible role in the pathogenesis of malarial anemia. Infection and Immunity. 2000;68(4):2259–2267. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.4.2259-2267.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McDevitt MA, Xie J, Shanmugasundaram G, et al. A critical role for the host mediator macrophage migration inhibitory factor in the pathogenesis of malarial anemia. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2006;203(5):1185–1196. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.von der Weid T, Honarvar N, Langhorne J. Gene-targeted mice lacking B cells are unable to eliminate a blood stage malaria infection. Journal of Immunology. 1996;156(7):2510–2516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Langhorne J, Cross C, Seixas E, Li C, Von Der Weid T. A role for B cells in the development of T cell helper function in a malaria infection in mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95(4):1730–1734. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moser M, Murphy KM. Dendritic cell regulation of TH1-TH2 development. Nature Immunology. 2000;1(3):199–205. doi: 10.1038/79734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lazarou M, Guevara Patiño JA, Jennings RM, et al. Inhibition of erythrocyte invasion and Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein 1 processing by human immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) and IgG3 antibodies. Infection and Immunity. 2009;77(12):5659–5667. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00167-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.von der Weid T, Langhorne J. Altered response of CD4+ T cell subsets to Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi in B cell-deficient mice. International Immunology. 1993;5(10):1343–1348. doi: 10.1093/intimm/5.10.1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Taylor-Robinson AW, Phillips RS. Reconstitution of B-cell-depleted mice with B cells restores Th2-type immune responses during Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi infection. Infection and Immunity. 1996;64(1):366–370. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.1.366-370.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Haldar K, Mohandas N. Malaria, erythrocytic infection, and anemia. American Society of Hematology: Education Program. 2009:87–93. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2009.1.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pasvol G, Clough B, Carlsson J. Malaria and the red cell membrane. Blood Reviews. 1992;6(4):183–192. doi: 10.1016/0268-960x(92)90014-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Buffet PA, Safeukui I, Milon G, Mercereau-Puijalon O, David PH. Retention of erythrocytes in the spleen: a double-edged process in human malaria. Current Opinion in Hematology. 2009;16(3):157–164. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e32832a1d4b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nweneka CV, Doherty CP, Cox S, Prentice A. Iron delocalisation in the pathogenesis of malarial anaemia. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2010;104(3):175–184. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Barsoum RS. Malarial nephropathies. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 1998;13(6):1588–1597. doi: 10.1093/ndt/13.6.1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ehrich JHH, Eke FU. Malaria-induced renal damage: facts and myths. Pediatric Nephrology. 2007;22(5):626–637. doi: 10.1007/s00467-006-0332-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Troye-Blomberg M, Berzins K. Immune interactions in malaria co-infections with other endemic infectious diseases: implications for the development of improved disease interventions. Microbes and Infection. 2008;10(9):948–952. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2008.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bereczky S, Montgomery SM, Troye-Blomberg M, Rooth I, Shaw M, Färnert A. Elevated anti-malarial IgE in asymptomatic individuals is associated with reduced risk for subsequent clinical malaria. International Journal for Parasitology. 2004;34(8):935–942. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Safeukui I, Vatan R, Dethoua M, et al. A role of IgE and CD23/NO immune pathway in age-related resistance of Lewis rats to Plasmodium berghei ANKA? Microbes and Infection. 2008;10(12-13):1411–1416. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2008.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Duarte J, Herbert F, Guiyedi V, et al. High levels of immunoglobulin E autoantibody to 14-3-3 epsilon protein correlate with protection against severe Plasmodium falciparum malaria. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2012;206(11):1781–1789. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Langhorne J, Quin SJ, Sanni LA. Mouse models of blood-stage malaria infections: immune responses and cytokines involved in protection and pathology. Chemical Immunology. 2002;80:204–228. doi: 10.1159/000058845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lamb TJ, Brown DE, Potocnik AJ, Langhorne J. Insights into the immunopathogenesis of malaria using mouse models. Expert Reviews in Molecular Medicine. 2006;8(6):1–22. doi: 10.1017/S1462399406010581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stevenson MM, Urban BC. Antigen presentation and dendritic cell biology in malaria. Parasite Immunology. 2006;28(1-2):5–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.2006.00772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wykes MN, Liu XQ, Jiang S, Hirunpetcharat C, Good MF. Systemic tumor necrosis factor generated during lethal Plasmodium infections impairs dendritic cell function. Journal of Immunology. 2007;179(6):3982–3987. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.3982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hisaeda H, Hamano S, Mitoma-Obata C, et al. Resistance of regulatory T cells to glucocorticoid-viduced TNFR family-related protein (GITR) during Plasmodium yoelii infection. European Journal of Immunology. 2005;35(12):3516–3524. doi: 10.1002/eji.200526073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vigário AM, Gorgette O, Dujardin HC, et al. Regulatory CD4+CD25+ Foxp3+ T cells expand during experimental Plasmodium infection but do not prevent cerebral malaria. International Journal for Parasitology. 2007;37(8-9):963–973. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Omer FM, de Souza JB, Riley EM. Differential induction of TGF-beta regulates proinflammatory cytokine production and determines the outcome of lethal and nonlethal Plasmodium yoelii infections. The Journal of Immunology. 2003;171(10):5430–5436. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.10.5430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kobayashi F, Ishida H, Matsui T, Tsuji M. Effects of in vivo administration of anti-IL-10 or anti-IFN-γ monoclonal antibody on the host defense mechanism against Plasmodium yoelii yoelii infection. Journal of Veterinary Medical Science. 2000;62(6):583–587. doi: 10.1292/jvms.62.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Couper KN, Blount DG, Wilson MS, et al. IL-10 from CD4+CD25-Foxp3-CD127- adaptive regulatory T cells modulates parasite clearance and pathology during malaria infection. PLoS Pathogens. 2008;4(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000004.e1000004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Abel S, Lückheide N, Westendorf AM, et al. Strong impact of CD4+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells and limited effect of T cell-derived IL-10 on pathogen clearance during Plasmodium yoelii infection. The Journal of Immunology. 2012;188(11):5467–5477. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Langhorne J, Albano FR, Hensmann M, et al. Dendritic cells, pro-inflammatory responses, and antigen presentation in a rodent malaria infection. Immunological Reviews. 2004;201:35–47. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00182.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Moreau E, Chauvin A. Immunity against helminths: interactions with the host and the intercurrent infections. Journal of Biomedicine and Biotechnology. 2010;2010:9 pages. doi: 10.1155/2010/428593.428593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Savioli L, Albonico M. Soil-transmitted helminthiasis. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2004;2(8):618–619. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Brooker S, Clements ACA, Bundy DAP. Global epidemiology, ecology and control of soil-transmitted helminth infections. Advances in Parasitology. 2006;62:221–261. doi: 10.1016/S0065-308X(05)62007-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ottesen EA. Lymphatic filariasis: treatment, control and elimination. Advances in Parasitology. 2006;61:395–441. doi: 10.1016/S0065-308X(05)61010-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Olsen A, van Lieshout L, Marti H, et al. Strongyloidiasis—the most neglected of the neglected tropical diseases? Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2009;103(10):967–972. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2009.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lustigman S, Prichard RK, Gazzinelli A, et al. A research agenda for helminth diseases of humans: the problem of helminthiases. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2012;6(4):p. e1582. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chitsulo L, Engels D, Montresor A, Savioli L. The global status of schistosomiasis and its control. Acta Tropica. 2000;77(1):41–51. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(00)00122-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Giri S, Parija SC. A review on diagnostic and preventive aspects of cystic echinococcosis and human cysticercosis. Tropical Parasitology. 2012;2(2):99–108. doi: 10.4103/2229-5070.105174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Maizels RM, Yazdanbakhsh M. Immune regulation by helminth parasites: cellular and molecular mechanisms. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2003;3(9):733–744. doi: 10.1038/nri1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Anthony RM, Rutitzky LI, Urban JF, Jr., Stadecker MJ, Gause WC. Protective immune mechanisms in helminth infection. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2007;7(12):975–987. doi: 10.1038/nri2199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Maizels RM, Balic A, Gomez-Escobar N, Nair M, Taylor MD, Allen JE. Helminth parasites—masters of regulation. Immunological Reviews. 2004;201:89–116. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Borkow G, Leng Q, Weisman Z, et al. Chronic immune activation associated with intestinal helminth infections results in impaired signal transduction and anergy. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2000;106(8):1053–1060. doi: 10.1172/JCI10182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sakaguchi S, Yamaguchi T, Nomura T, Ono M. Regulatory T cells and immune tolerance. Cell. 2008;133(5):775–787. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]