Abstract

Background

Recent investigation has demonstrated that approximately 75% of patients with medically refractory chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) report abnormal sleep quality, with strong correlation between worse sleep quality and more severe CRS disease severity. It remains unknown whether the treatment effect of endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS) for CRS results in appreciable sleep quality improvements.

Methods

Adult patients (aged ≥18 years) with a current diagnosis of recalcitrant chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS), who voluntarily elected ESS as the next treatment modality (n=301), were prospectively evaluated within four academic, tertiary care centers using treatment outcome instruments: the Rhinosinusitis Disability Index, the 22-item Sinonasal Outcome Test, the 2-item Patient Health Questionnaire, and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) both before and after ESS.

Results

72% of patients with CRS were found to have poor sleep (>5) at baseline with a mean global PSQI score of 9.4(4.6). Surgery improved overall mean global PSQI scores (2.2 points), and all 7 subdomain scores of the PSQI. Similarly, the odds of good sleep quality (PSQI ≤5) in patients treated with sinus surgery increased significantly (OR: 5.94, 95% CI: 3.06, 11.53; p<0.001). Stepwise multivariate linear regression found that ASA intolerance (β= −1.94(0.93); 95% CI: −3.77, −0.11; p=0.038), history of prior sinus surgery (β=1.10(0.54); 95% CI: 0.03, 2.16; p=0.044), and frontal sinusotomy (β= −1.03(0.62); 95% CI: −2.26, 0.20; p=0.099) were found to significantly associate with improvement in PSQI sleep scores.

Conclusions

Among patients with CRS, reduced sleep quality, poor disease-specific quality of life, and greater disease severity were improved following ESS.

MeSH Key Words: Sinusitis, rhinosinusitis, endoscopic sinus surgery, chronic disease, sleep, quality of life, rhinitis

INTRODUCTION

Chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) is a common and debilitating health condition afflicting ~11.1 million Americans, resulting in ~18.3 million physician office visits, 11.5 million lost workdays, and has a direct annual cost of $8.6 billion.1,2 Investigations have shown that patients with CRS have significant declines in general and disease-specific quality-of-life (QOL), with baseline health state utility values well below the normal for the U.S. population and similar to utility scores seen in other debilitating diseases such as coronary artery disease, end-stage renal disease, congestive heart failure, and pre-liver transplantation.3

Evidence has been accumulating that sleep disabilities impair the physical, psychological and social aspects of a patient’s wellbeing and overall QOL. Investigations have illuminated the association between sleep dysfunction and impaired QOL in several chronic inflammatory diseases, including fibromyalgia,4 rheumatoid arthritis,5,6 ankylosing spondylitis,7 myasthenia gravis,8 and cystic fibrosis.9,10 Consistent poor sleep can also have long-term health consequences, including but not limited to diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and even increased mortality.11,12 Furthermore, poor sleepers also demonstrate a higher prevalence of disease severity, with poor sleep directly relating to disease-specific disability.13 It has recently been demonstrated that upwards of 75% of patients with CRS report abnormal sleep quality, with worse sleep seen in those with more severe sinus disease.14 What remains unknown is whether CRS-specific treatments result in improved sleep quality.

Endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS) has typically been reserved for those patients with recalcitrant CRS-specific symptoms despite comprehensive medical management. It is now well accepted that lasting improvements in CRS-specific QOL3,15 occurs in patients with medically refractory CRS after ESS. It remains unknown, however, if similar improvements in sleep quality would be appreciated after ESS. The objective of this investigation was to examine the impact of sinus surgery on sleep quality in patients with medically refractory CRS.

METHODS

Patient Populations

Adult patients (aged ≥ 18 years) with a current diagnosis of medically refractory CRS were prospectively enrolled into an ongoing North American, multi-institutional, observational, treatment outcomes investigation between April, 2011 and January, 2014. Preliminary findings from this cohort have been described elsewhere.14,16 Diagnosis of CRS was defined by the 2007 Adult Sinusitis Guideline endorsed by the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery.17 All patients had been previously treated with an oral, broad spectrum, or culture directed antibiotic (≥2 weeks duration) and either topical nasal corticosteroid sprays (≥3 week duration) or a 5-day trial of systemic steroid therapy. Enrollment sites consisted of four academic, tertiary care rhinology practices, including Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU, Portland, OR, USA), the Medical Univeristy of South Carolina (Charleston, SC, USA), Stanford University (Palo Alto, CA, USA), and the University of Calgary (Calgary, Alberta, Canada). The Institutional Review Board at each enrollment location approved all investigational protocols and informed consent processes.

During the initial clinical / enrollment visit, all study subjects completed a medical history, head and neck clinical examinations, sinonasal endoscopy, and computed tomography (CT) imaging of the sinuses as part of the standard of care. Information was collected from patients and the medical record including age, gender, race, ethnicity, nasal polyposis, history of prior sinus surgery, asthma, acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) intolerance, current tobacco use (packs/day), alcohol consumption (grams/week), depression, allergies (reported by patient history or confirmed skin prick or radioallergosorbent testing), ciliary dysfunction / cystic fibrosis, recurrent acute rhinosinusitis (RARS), obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), and asthma / sinusitis related steroid dependency. Trained project coordinators at each enrollment site assisted with both informed consent and all study data collection.

Surgical Intervention- Endoscopic Sinus Surgery

All study subjects elected endoscopic sinus surgery as the next treatment modality for symptoms of CRS. Surgical procedures were based on the individual disease process and intraoperative clinical judgement of the enrolling physician and consisted of either unilateral or bilateral maxillary anstrostomy, partial or total ethmoidectomy, sphenoidotomy, middle turbinate resection or inferior turbinate reduction, frontal sinus procedures (Draf I, IIa, IIb, or III), or septoplasty. Subjects were considered either primary or revision surgery cases.

Sleep Quality Evaluation

All study subjects were directed to complete the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) preoperatively following the initial enrollment meeting and in subsequent post-operative visits. The PSQI is a validated, widely utilized, 19-item, self-rated measure of sleep quality and duration. Subjects are instructed to recall sleep quality during the month prior to survey completion. The PSQI yields a total score (range: 0–21) and seven component scores including: sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, sleep efficiency, sleep disturbance, sleep medication usage, and daytime dysfunction (range: 0–3). Higher PSQI scores suggest greater sleep disturbance. A PSQI score ≤ 5 is considered the threshold for “good” sleep quality, whereas a score > 5 is characterized as “poor” sleep quality.18 The PSQI component scores have high internal homogeneity (Cronbach’s α=0.83) while global PSQI scores > 5 have been shown to have a sensitivity of 89.6% and specificity of 86.5% (Kappa=0.75; p<0.001).

Disease-Specific Quality of Life Measures

Study case subjects completed two CRS-specific QOL instruments: the Rhinosinusitis Disability Index (RSDI)19 and the 22-item Sinonasal Outcome Test (SNOT-22, All rights reserved. ©2006 by Washington University in St. Louis, MO, USA).20 The RSDI is a 30-item, disease-specific survey instrument consisting of three subscales that evaluate the impact of CRS on a patient’s physical (score range: 0–44), functional (score range: 0–36), and emotional (score range: 0–40) sub-domains using a Likert scale. Higher sub-domain and total RSDI scores indicate greater impacts of chronic sinonasal disease (total score range: 0–120). The SNOT-22 is a validated, 22-item treatment outcome measure applicable to chronic sinonasal conditions. Lower total scores on the SNOT-22 suggest better patient functioning and reduced symptom severity (total score range: 0–110). The 2-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2) is an abridged version of the PHQ-9 instrument developed as a depression screening tool (total score range: 0–6). A score of 3 or more is indicated as optimal cut-point for a positive indication for depression.21 These three instruments were chosen because they are validated instruments that evaluate different aspects of CRS-specific health impacts in a comprehensive fashion. The enrolling physicians at each site were blinded to all patient-based survey responses for the study duration. Subjects were asked to complete the PSQI, RSDI, SNOT-22, and PHQ-2 surveys preoperatively and at subsequent post-operative clinic visits. Patients were “lost to follow-up” if they had not completed any survey evaluations postoperatively within 18 months.

Semi-Quantitative Disease Severity Measures

Computed tomography (CT) images were evaluated and staged in accordance with the Lund-Mackay bilateral scoring system where higher scores represent higher severity of disease (score range: 0–24).22 This scoring system quantifies the severity of image opacification in the maxillary, ethmoidal, sphenoidal, ostiomeatal complex, and frontal sinus regions. Endoscopic examinations were scored using the Lund-Kennedy endoscopy scoring system where again higher scores represent worse disease severity (score range: 0–20).23 This staging system grades bilateral, visual pathologic states within the paranasal sinuses including polyposis, discharge, edema, scarring, and crusting. Each enrolling physician quantitatively evaluated all baseline scans at the time of enrollment and was blinded to other study data.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Study case subjects diagnosed with a current exacerbation of recurrent acute sinusitis were excluded from final analyses due to the heterogeneity of the disease process. Subjects were removed from final analyses if they failed to complete the baseline PSQI evaluation or had not yet reached the 6-month follow-up appointment window. Study subjects diagnosed with sleep disorders including OSA (via recent, positive polysomnogram or past medical history), or a history of steroid dependency due to sinusitis or concurrent asthma were excluded due to the known negative influence of those comorbidities on sleep.24

Data Management and Statistical Analysis

De-identified study data was collected and transferred from each enrollment site to a central coordinating site (OHSU) to be entered into a relational database (Microsoft Access, Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA) using standardized clinical research forms. Statistical analysis was performed using a commercially available statistical software program (SPSS v.22.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Mean improvement in PSQI scores was the main criterion for sample size determination. Based on former analytic findings, we expected a baseline mean PSQI score of 9.4 and standard deviation of 4.4.14 Assuming a conservative correlation coefficient (r=0.300) between preoperative and postoperative PSQI total scores, and equal variances between dependent matched pairs, a total of 215 study subjects were required to detect significance in the smallest average one-point unit improvement in PSQI total scores with a 1-β error probability of 80.0% and α=0.050.

Descriptive metrics were completed for all demographic variables, clinical measures of CRS disease severity, and PSQI survey responses. Assumptions of data normality were verified for all continuous measures using graphical analysis. Differences in demographics and medical comorbidities between study subjects with and without postoperative follow-up were evaluated using two-sided sample t-tests and Pearson’s chi-square (χ2) tests. Wilcoxon signed-rank tests and matched pair t-tests were used to assess significant changes between preoperative and postoperative mean PSQI scores where appropriate. The primary outcome of interest was operationalized two ways including: (a) change in mean PSQI component and total scores (postoperative minus preoperative), and (b) dichotomized groups above and below the traditional PSQI total score threshold for “good” and “poor” sleepers. Improvement in the prevalence of poor sleep after ESS was calculated using McNemar’s χ2 test for paired samples and corresponding odds ratio (OR) tests. Spearmans’ rank correlation coefficient (rs) was used to assess associations between all PSQI, RSDI, and SNOT-22 survey score responses.

Manual, stepwise multivariate linear regression was used to identify potential significant independent risk factors associated with improvement in mean PSQI total scores employing a forward selection and backwards elimination (p<0.010) technique. The main outcome of interest was operationalized by subtracting preoperative scores from postoperative scores. Univariate screening of 30 separate covariates was employed to identify preliminary model factors using a conventional alpha level of 0.250. Without adjustment for preoperative PSQI scores, final model construction adjusted for potential differences between enrollment sites and collinearity was assessed using variance inflation factors (VIFs) when appropriate. Regression coefficients (β) with corresponding standard errors were generated to provide an estimate of linear change while the coefficient of multiple determinations was used to determine the percentage of explained final model variance.

RESULTS

Demographic Data

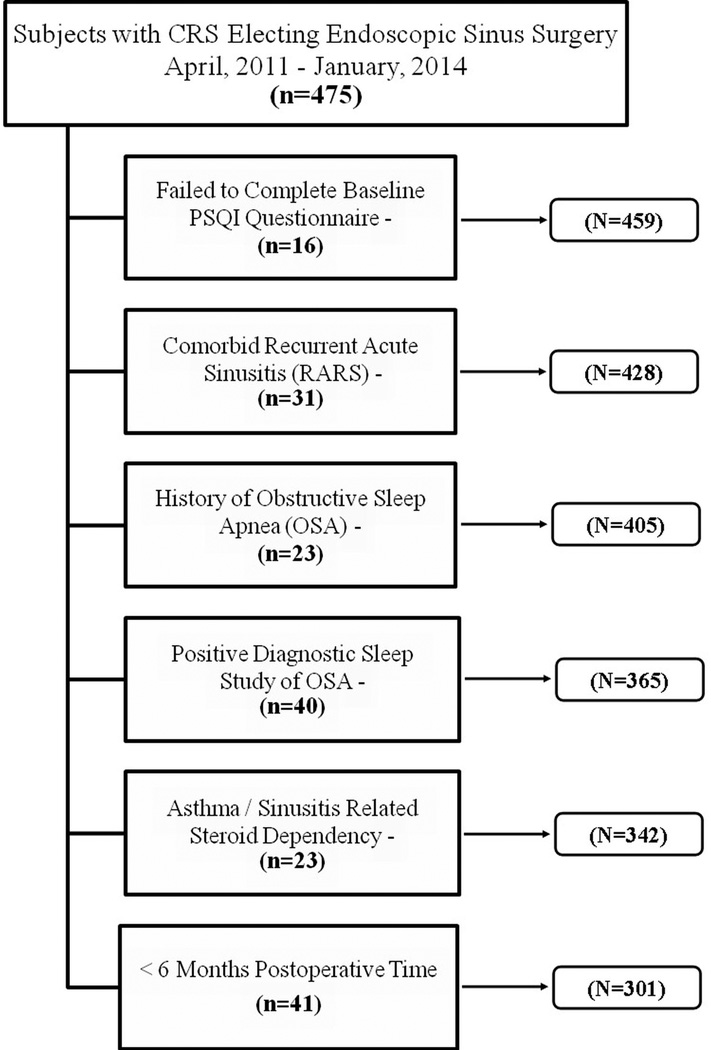

After all inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied, a total of 301 subjects completed all eligibility requirements and were included for final study analysis (Figure 1). Demographics, general clinical characteristics, disease severity measures, and sleep quality scores were compared between 219 study subjects with follow-up (72.8%) and 82 subjects without follow-up (27.2%) evaluations (Table 1). The mean age of subjects lost to follow-up were significantly younger, reported a higher prevalence of current tobacco smoking, and were found to have lower average baseline CT scores. There was no significant difference in PSQI scores or sinus-specific QOL scores between those with follow-up and those lost to follow-up (p-value >0.446).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for final cohort selection after exclusion criteria.

Table 1.

Comparison of demographics, general clinical characteristics, disease severity measures, and sleep quality scores in subjects with and without study follow-up.

| With ≥6 month study follow-up (n=219) |

Without study follow-up (n=82) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics: | Mean (SD) | Range | N(%) | Mean (SD) | Range | N(%) | p-value |

| Age (years) | 50.7 (14.7) | [18 – 86] | 46.0 (15.2) | [19 – 82] | 0.016 | ||

| Male | 101 (46.1) | 38 (46.3) | |||||

| Female | 118 (53.9) | 44 (53.7) | 0.972 | ||||

| Race: | |||||||

| White/Caucasian | 185 (84.5) | 67 (81.9) | |||||

| African American | 11 (5.0) | 1 (1.2) | |||||

| Asian | 9 (4.1) | 5 (6.1) | |||||

| NH / PI | -- | 1 (1.2) | |||||

| Reported Other | 14 (6.4) | 7 (8.5) | 0.218 | ||||

| Ethnicity: | |||||||

| Hispanic/Latino | 11 (5.0) | 4 (4.9) | 0.959 | ||||

| Nasal polyps | 84 (38.4) | 23 (28.0) | 0.096 | ||||

| Prior sinus surgery | 110 (50.2) | 43 (52.4) | 0.733 | ||||

| Asthma | 74 (33.8) | 27 (32.9) | 0.888 | ||||

| ASA intolerance | 20 (9.1) | 4 (4.9) | 0.338 | ||||

| Current smoker/tobacco use | 11 (5.0) | 11 (13.4) | 0.013 | ||||

| Alcohol consumption | 103 (47.0) | 44 (53.7) | 0.306 | ||||

| Depression (self-report) | 36 (16.4) | 11 (13.4) | 0.520 | ||||

| Allergies | 78 (35.6) | 26 (31.7) | 0.525 | ||||

| Ciliary dysfunction / CF | 5 (2.3) | 4 (4.9) | 0.262 | ||||

| Baseline PSQI total score | 9.4 (4.6) | [1 – 21] | 9.9 (4.4) | [2 – 21] | 0.446 | ||

| Poor Sleep Quality (>5) | 158 (72.1) | 65 (79.3) | 0.209 | ||||

| Baseline RSDI total score | 46.5 (25.0) | [1 – 116] | 47.9 (25.2) | [4 – 110] | 0.646 | ||

| Baseline SNOT-22 score | 53.2 (19.5) | [11 – 106] | 51.7 (22.0) | [0 – 102] | 0.564 | ||

| Baseline PHQ-2 score | 1.7 (1.7) | [0 – 6] | 1.7 (1.7) | [0 – 6] | 0.912 | ||

| Baseline CT score | 12.4 (6.0) | [0 – 24] | 10.8 (5.3) | [0 – 24] | 0.044 | ||

| Baseline Endoscopy score | 6.1 (3.9) | [0 – 18] | 5.9 (3.8) | [0 – 14] | 0.590 | ||

SD=standard deviation. NH/PI=Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander. ASA=acetylsalicylic acid. Gr=grams. CF=cystic fibrosis. PSQI=Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. SNOT-22=Sinonasal outcome test. PHQ-2=Patient Health Questionnaire. CT=computed tomography. Comparisons were assessed using two-tailed independent sample t-tests and chi-square testing where appropriate.

Prevalence of Interventional Procedures

Endoscopic sinus surgery procedures for this investigation were contingent on physician discretion and disease progression for each study subject per normal standard of care. For subjects with study follow-up (n=219), procedures consisted of either unilateral or bilateral maxillary antrostomy (n=210; 95.9%), partial ethmoidectomy (n=39; 17.8%), total ethmoidectomy (n=179; 81.7%), sphenoidotomy (n=160; 73.1%), middle turbinate reduction (n=38; 17.4%), inferior turbinate reduction (n=34; 15.5%), frontal sinusotomy (Draf I, IIa/b, or III; n=161; 73.5%), and septoplasty (n=89, 40.6%).

Sleep Quality Outcomes

Improvement in Mean PSQI scores

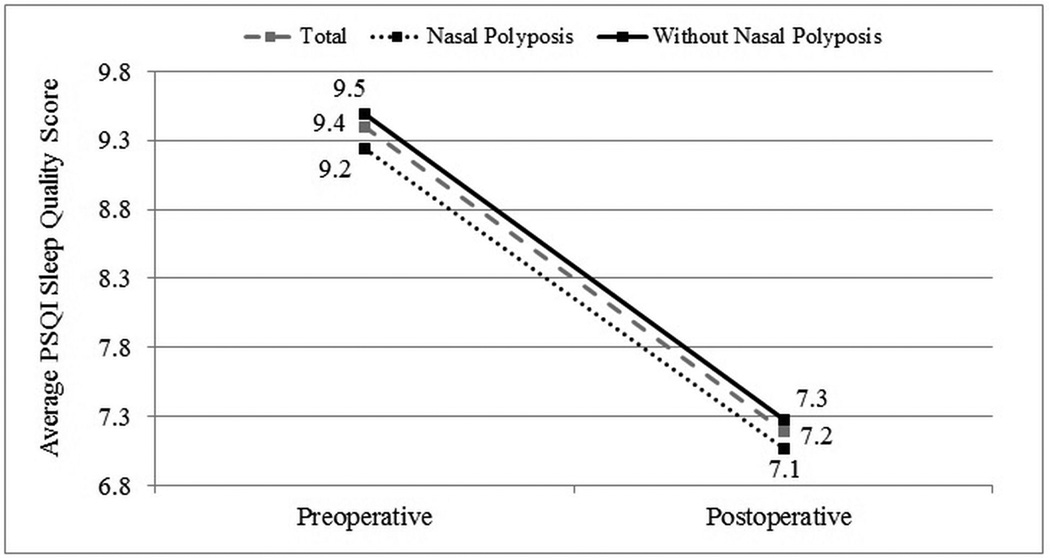

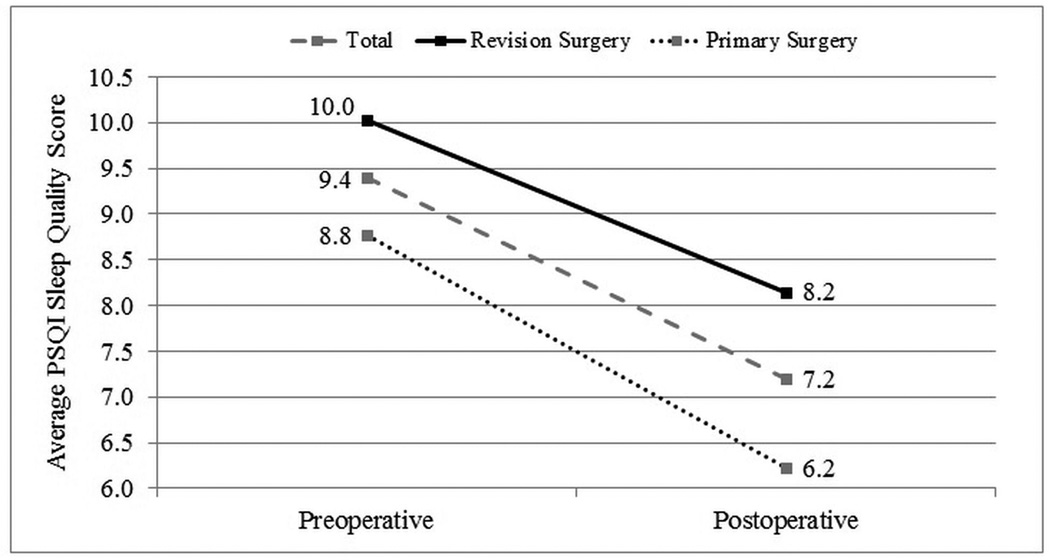

Case subjects were followed for an average of 13.1(5.4) months postoperatively. Improvement in average PSQI total and component scores was evaluated for all subjects with postoperative follow-up. Statistically significant improvement was found for all PSQI subdomain scores (p<0.001) with an overall mean improvement in the global PSQI score of 2.2 points (Table 2). Average PSQI score improvement in subgroups with (n=84) and without (n=135) nasal polyposis (Figure 2) and subjects with (n=110) and without (n=109) a history of prior sinus surgery (Figure 3) were compared. Each discrete subgroup was found to have similar statistically significant improvements in PSQI over time (p<0.001).

Table 2.

Comparison of mean preoperative and postoperative PSQI scores for all case subjects with follow-up (n=219).

| Preoperative | Postoperative | Change | Range | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean(SD) | Mean(SD) | Mean(SD) | [LL, UL] | p-value | |

| PSQI Sleep quality | 2.4 (0.9) | 2.1 (1.1) | −0.3 (1.2) | [−3, 3] | <0.001 |

| PSQI Medication | 2.3 (1.0) | 2.0 (1.1) | −0.3 (1.0) | [−3, 3] | <0.001 |

| PSQI Duration | 1.0 (1.1) | 0.7 (0.9) | −0.3 (0.9) | [−3, 2] | <0.001 |

| PSQI Sleep disturbance | 1.9 (0.7) | 1.6 (0.7) | −0.3 (0.9) | [−2, 1] | <0.001 |

| PSQI Sleep latency | 1.5 (1.1) | 1.2 (1.1) | −0.3 (0.9) | [−3, 2] | <0.001 |

| PSQI Daytime dysfunction | 1.3 (0.8) | 0.9 (0.8) | −0.4 (0.9) | [−3, 2] | <0.001 |

| PSQI Sleep efficiency | 1.0 (1.1) | 0.7 (1.0) | −0.3 (1.1) | [−3, 3] | <0.001 |

| PSQI Total score | 9.4 (4.6) | 7.2 (4.4) | −2.2 (4.0) | [−16, 6] | <0.001 |

SD=standard deviation. PSQI=Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. Comparisons were made using a two-tailed, paired samples t-test.

Figure 2.

Improvement in average PSQI sleep quality scores for subjects with and without nasal polyposis.

Figure 3.

Improvement in average PSQI sleep quality scores for subjects with and without a history of prior endoscopic sinus surgery.

Change in the Prevalence of Sleep Quality

Baseline PSQI total survey scores were dichotomized into those with “good” and “poor” sleep quality as previously defined. The prevalence of poor sleep between subjects with and without study follow-up is reported in Table 1. For case subjects with follow-up, the prevalence of poor sleep was significantly reduced from 72.1% before ESS to 56.6% (124/219) after ESS (χ2=30.81; df=1, p<0.001).

Correlation between Sleep Quality and Quality of Life

Bivariate correlation analysis was used to determine if patients who report improved sleep quality scores have a corresponding association with disease-specific QOL as measured by RSDI and SNOT-22 survey scores. Non-linear associations between sleep quality scores and disease-specific QOL scores were evaluated preoperatively, postoperatively, and between postoperative change scores as previously defined (Tables 3–5). Preoperative and postoperative PSQI total scores positively correlated with both corresponding RSDI total scores (p<0.001) and SNOT-22 total scores (p<0.001), suggesting poor sleep quality moderately correlates with worse disease or symptom severity before and after surgical intervention for CRS. The magnitude of correlation between PSQI, RSDI, and SNOT-22 change scores was significant (p<0.001) but slightly less than that found for preoperative and postoperative associations.

Table 3.

Correlation coefficients between preoperative PSQI, RSDI, and SNOT-22 scores.

| RSDI Physical |

RSDI Functional |

RSDI Emotional |

RSDI Total | SNOT-22 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative scores (n=301): | Rs | Rs | Rs | Rs | Rs |

| PSQI Sleep quality | 0.329** | 0.306** | 0.281** | 0.325** | 0.353** |

| PSQI Medication | 0.169* | 0.198* | 0.167* | 0.192* | 0.181* |

| PSQI Duration | 0.281** | 0.223** | 0.228** | 0.261** | 0.351** |

| PSQI Sleep disturbance | 0.443** | 0.442** | 0.401** | 0.465** | 0.512** |

| PSQI Sleep latency | 0.389** | 0.311** | 0.295** | 0.358** | 0.403** |

| PSQI Daytime dysfunction | 0.409** | 0.536** | 0.526** | 0.534** | 0.405** |

| PSQI Sleep efficiency | 0.320** | 0.255** | 0.250** | 0.293** | 0.374** |

| PSQI Total score | 0.533** | 0.512** | 0.494** | 0.552** | 0.600** |

indicates significant correlation p<0.050.

indicates significant correlation p<0.001.

Spearman’s correlation coefficients (Rs) for nonparametric distributions were used.

Table 5.

Correlation coefficients between PSQI, RSDI, and SNOT-22 postoperative change scores.

| RSDI Physical |

RSDI Functional |

RSDI Emotional |

RSDI Total | SNOT-22 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Postoperative change scores (n=219): | Rs | Rs | Rs | Rs | Rs |

| PSQI Sleep quality | 0.375** | 0.314** | 0.201* | 0.332** | 0.377** |

| PSQI Medication | 0.172* | 0.098 | 0.039 | 0.119 | 0.185* |

| PSQI Duration | 0.128 | 0.173* | 0.149* | 0.152* | 0.237** |

| PSQI Sleep disturbance | 0.402** | 0.279** | 0.212* | 0.327** | 0.394** |

| PSQI Sleep latency | 0.309** | 0.285** | 0.265** | 0.313** | 0.432** |

| PSQI Daytime dysfunction | 0.441** | 0.460** | 0.455** | 0.503** | 0.411** |

| PSQI Sleep efficiency | 0.147* | 0.137* | 0.107 | 0.143* | 0.201* |

| PSQI Total score | 0.365** | 0.363** | 0.338** | 0.383* | 0.456** |

indicates significant correlation p<0.050.

indicates significant correlation p<0.001.

Spearman’s correlation coefficients (Rs) for nonparametric distributions were used.

Due to potential bias of disease-specific survey questions directly relating to sleep quality, correlations were further assessed after sleep quality specific survey item scores were removed from both the RSDI Physical subscale (#9) and SNOT-22 (#11,12,13,14) survey instruments. Correlations between preoperative, postoperative, and postoperative change scores continued to show significant correlations, with only small decreases in correlations, as expected.

Regression Modeling for Improvement in Sleep Quality Scores

Univariate screening procedures identified 12 potential cofactors for preliminary model building. Interestingly conventionally understood risk factors for poor sleep quality, such as, age, gender, depression, nasal obstruction, and self-reported alcohol use were not found to be significantly associated with improvement in PSQI sleep scores. After adjusting for enrollment site differences (p=0.045), the final model included ASA intolerance (β= −1.94(0.93); 95% CI: −3.77, −0.11; p=0.038), history of prior sinus surgery (β=1.10(0.54); 95% CI: 0.03, 2.16; p=0.044), and frontal sinusotomy procedures as part of the surgical intervention (β= −1.03(0.62); 95% CI: −2.26, 0.20; p=0.099). No evidence of collinearity (VIFs < 2.00), effect modification, or confounding was discovered between significant cofactors in the final model, while significant cofactors could only explain 22% of total model variability.

DISCUSSION

Sinus-specific symptoms are the hallmark of CRS and certainly contribute to the poor QOL reported in this population. However, recent investigations suggest that the health impacts of CRS extend beyond the sinuses and can impact one of our most basic functions: sleep. A total of 72% of patients in this cohort were found to have poor sleep (>5) at baseline with a mean global PSQI score of 9.4 (4.6). Sinus surgery was associated with a robust improvement in overall mean global PSQI scores (2.2 points), in addition to significantly improving all 7 subdomain scores of the PSQI. Similarly, the odds of good sleep quality (PSQI≤5) in patients treated with sinus surgery increased significantly (OR: 5.94, 95% CI: 3.06, 11.53; p<0.001). Sinus surgery was associated with a treatment response for poor sleep quality that is comparable to levels achieved by other treatment strategies for improving sleep quality.25

Poor sleep quality in patients with CRS significantly correlates with worse CRS disease-specific QOL as measured by the SNOT-22 and RSDI, which is consistent with prior investigations.14 The association between sleep quality and QOL persisted after ESS and after removing sleep quality specific survey items from both the SNOT-22 and RSDI. There is a large body of evidence that has shown that ESS improves not only disease-specific QOL but also general QOL and that it may do so in part by improving associated comorbidities. An example is depression, wherein CRS patients with depression have significant postoperative improvement in both QOL and depression severity.26 Likewise, QOL and sleep in CRS may have a bidirectional relationship - worse sleep in CRS leads to poor QOL, and subsequently poor QOL escalates poor sleep.

Although this study suggests sinus surgery may lead to improvements in sleep quality, the mechanisms through which these improvements may occur remains unknown. Nasal obstruction may be playing a role in CRS-associated sleep dysfunction, as nasal polyps have been associated with sleep breathing disorder (SBD)27 and reduced QOL.28,29 Unfortunately, we did not objectively evaluate nasal obstruction and are unable to decipher the role ESS plays in improving nasal obstruction as it relates to sleep or QOL. There have been many plausible hypotheses concerning the pathophysiology of sleep in both health and disease with increasing evidence implicating somnogenic pro-inflammatory cytokines.30 Excessive sleepiness and fatigue are common symptoms of both infection and inflammation. Promotion of non-rapid eye movement sleep is due, in part, to the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines locally or those induced in the brain. CRS is a chronic inflammatory disease that is associated with changes in cytokines, their receptors, and downstream products.31 Many pro-inflammatory cytokines promote NREMS after systemic or intracerebral administration. Interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα) are the two best-documented somnogenic cytokines and both are induced in CRS.32 In humans, sleep loss and altered pro-inflammatory cytokine levels are associated but not limited to fatigue,33,34 pain,35 depression,36 impaired cognition,37 and memory.38 There is a considerable amount of literature linking sleep regulatory peptides in CRS and sleep regulation suggesting plausibility of an immune-brain connection.39 The mechanisms by which this immune-brain connections occurs is currently being heavily investigated; although preliminary evidence suggests cytokines either act in the brain directly by passage across the blood brain barrier, stimulate afferent transmission, or alter the level or activity of another substance that subsequently signals the brain.40,41 We posit that the decline in local cytokines following sinus surgery may be one factor that is driving the improvements in sleep quality, but at present this remains conjecture. Certainly future studies which intend to explore the mechanisms underlying sleep improvement in CRS should explore both reduction in nasal obstruction and somnogenic cytokines in a rigorous fashion.

This study utilized the PSQI as a measure of patient reported sleep dysfunction, but the PSQI does not always positively correlate to polysomnography-measured sleep10,42,43 or daytime sleepiness as measured by Epworth sleepiness scale.44 Although the PSQI has been shown to have a high sensitivity to predict both insomnia45 and daytime sleepiness,46 without the ability to monitor physiologic measures during sleep with concomitant polysomnography, it is not known if the abnormal self-rated sleep disability in patients with CRS is due to the local/systemic effects of the disease itself, or if there is an underlying specific sleep disorder (independent or secondary to the CRS). Interestingly, those comorbidities such as depression, nasal obstruction as defined by polyps, tobacco use, allergies, age, and sex were not found to be independent predictors of sleep dysfunction in our cohort. Future investigations evaluating objective measures of sleep quality in patients with CRS alongside patient-reported measures such as the PSQI are needed, as it is not known whether case subjects have undiagnosed sleep-disordered breathing or another objective sleep disorder. Certainly the fact that 56.6% of patients still reported poor sleep after sinus surgery suggests that surgery may not fully alleviate the problem and that further diagnostic and therapeutic interventions could be appropriate.

There are a number of caveats to consider when interpreting the findings of this study. There was a 27.2% loss to follow-up for all subjects meeting inclusion criteria, which introduces the possibility of follow-up bias, if postoperative outcomes influenced whether subjects followed-up or not. We found no meaningful differences in baseline patient characteristics between those with follow-up data and those without, including PSQI or QOL scores, suggesting that differential follow-up was not driving results of this study to a significant degree. Secondly, this study did not include a control arm of patients with CRS not undergoing surgery, so one cannot fully exclude the impact of placebo effects or the natural history of disease on reported outcomes. This study was conducted within tertiary rhinology practices across North America. Although the inclusion of multiple enrollment centers suggests results are not typical of only one center or surgeon, findings may not necessarily be externally generalizable to all patients having sinus surgery, or to the average follow-up time period beyond 13 months. Additionally, this analysis did not evaluate potential variations in average PSQI follow-up scores between 6 and 18 month intervals when available. Future investigation of sleep quality data may incorporate generalized linear modeling to evaluate the durability of longitudinal mean changes over discrete follow-up time points.

CONCLUSION

This investigation demonstrates significant improvement across all seven component score of the PSQI, however mean postoperative PSQI total scores were still above the threshold score value for poor sleep quality. Thus, on average sinus surgery was associated with significantly improved sleep quality in patients with CRS but the majority of patients are left with some burden of sleep dysfunction. Sleep quality in CRS is likely a complex, multi-factorial process and further study is warranted to better understand the interaction of these comorbid conditions.

Table 4.

Correlation coefficients between postoperative PSQI, RSDI, and SNOT-22 scores.

| RSDI Physical |

RSDI Functional |

RSDI Emotional |

RSDI Total | SNOT-22 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Postoperative scores (n=219): | Rs | Rs | Rs | Rs | Rs |

| PSQI Sleep quality | 0.376** | 0.368** | 0.325** | 0.380** | 0.471** |

| PSQI Medication | 0.218* | 0.153* | 0.127 | 0.189* | 0.193* |

| PSQI Duration | 0.287** | 0.282** | 0.283** | 0.294** | 0.420** |

| PSQI Sleep disturbance | 0.616** | 0.535** | 0.484** | 0.594** | 0.678** |

| PSQI Sleep latency | 0.316** | 0.311** | 0.288** | 0.335** | 0.427** |

| PSQI Daytime dysfunction | 0.573** | 0.691** | 0.686** | 0.692** | 0.609** |

| PSQI Sleep efficiency | 0.283** | 0.298** | 0.268** | 0.286** | 0.374** |

| PSQI Total score | 0.570** | 0.598** | 0.564** | 0.616** | 0.710** |

indicates significant correlation p<0.050.

indicates significant correlation p<0.001.

Spearman’s correlation coefficients (Rs) for nonparametric distributions were used.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors would like to thank Peter H. Hwang, MD and Luke Rudmik, MD for their ongoing dedication to patient enrollment in this multi-institutional cohort.

Financial Disclosure: Zachary M. Soler, MD, MSc, Jess C. Mace, MPH, and Timothy L. Smith, MD, MPH are supported by a grant from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD), one of the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD. (2R01 DC005805; PI/PD: T.L. Smith). Timothy L. Smith, MD is also a consultant for Intersect ENT (Menlo Park, CA.), which is not affiliated in any way with this investigation. There are no financial disclosures for Jeremiah A. Alt or Rodney J. Schlosser for this investigation.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None

Submitted for oral presentation to the American Rhinologic Society at the annual American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery meeting, Orlando, Florida, September 20th, 2014 (Abstract submission #720).

REFERENCES

- 1.Bhattacharyya N. Functional limitations and workdays lost associated with chronic rhinosinusitis and allergic rhinitis. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2012;26:120–122. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2012.26.3752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhattacharyya N. Incremental health care utilization and expenditures for chronic rhinosinusitis in the United States. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2011;120:423–427. doi: 10.1177/000348941112000701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soler ZM, Wittenberg E, Schlosser RJ, Mace JC, Smith TL. Health state utility values in patients undergoing endoscopic sinus surgery. Laryngoscope. 2011;121:2672–2678. doi: 10.1002/lary.21847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ulus Y, Akyol Y, Tander B, Durmus D, Bilgici A, Kuru O. Sleep quality in fibromyalgia and rheumatoid arthritis: associations with pain, fatigue, depression, and disease activity. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2011;29:S92–S96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Omachi TA. Measures of sleep in rheumatologic diseases: Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), Functional Outcome of Sleep Questionnaire (FOSQ), Insomnia Severity Index (ISI), and Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011;63(Suppl 11):S287–S296. doi: 10.1002/acr.20544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wells GA, Li T, Kirwan JR, et al. Assessing quality of sleep in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:2077–2086. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.090362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Batmaz I, Sariyildiz MA, Dilek B, Bez Y, Karakoc M, Cevik R. Sleep quality and associated factors in ankylosing spondylitis: relationship with disease parameters, psychological status and quality of life. Rheumatol Int. 2013;33:1039–1045. doi: 10.1007/s00296-012-2513-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Lapiscina EH, Aguirre ME, Blanco TA, Pascual IJ. Myasthenia gravis: sleep quality, quality of life, and disease severity. Muscle Nerve. 2012;46:174–180. doi: 10.1002/mus.23296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jankelowitz L, Reid KJ, Wolfe L, Cullina J, Zee PC, Jain M. Cystic fibrosis patients have poor sleep quality despite normal sleep latency and efficiency. Chest. 2005;127:1593–1599. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.5.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Milross MA, Piper AJ, Norman M, et al. Subjective sleep quality in cystic fibrosis. Sleep Med. 2002;3:205–212. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(01)00157-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Azevedo Da Silva M, Singh-Manoux A, Shipley MJ, et al. Sleep duration and sleep disturbances partly explain the association between depressive symptoms and cardiovascular mortality: the Whitehall II cohort study. J Sleep Res. 2014;23:94–97. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cappuccio FP, Miller MA. Sleep and mortality: cause, consequence, or symptom? Sleep Med. 2013;14:587–588. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Redeker NS, Hilkert R. Sleep and quality of life in stable heart failure. J Card Fail. 2005;11:700–704. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alt JA, Smith TL, Mace JC, Soler ZM. Sleep quality and disease severity in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis. Laryngoscope. 2013;123:2364–2370. doi: 10.1002/lary.24040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soler ZM, Smith TL. Quality-of-life outcomes after endoscopic sinus surgery: how long is long enough? Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;143:621–625. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2010.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soler ZM, Rudmik L, Hwang PH, Mace JC, Schlosser RJ, Smith TL. Patient-centered decision making in the treatment of chronic rhinosinusitis. Laryngoscope. 2013;123:2341–2346. doi: 10.1002/lary.24027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenfeld RM, Andes D, Bhattacharyya N, et al. Clinical practice guideline: adult sinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;137:S1–S31. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2007.06.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benninger MS, Senior BA. The development of the Rhinosinusitis Disability Index. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surgery. 1997;123:1175–1179. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1997.01900110025004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hopkins C, Gillett S, Slack R, Lund VJ, Browne JP. Psychometric validity of the 22-item Sinonasal Outcome Test. Clin Otolaryngol. 2009;34(5):447–454. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-4486.2009.01995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. 2003;41:1284–1292. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lund VJ, Mackay IS. Staging in rhinosinusitus. Rhinology. 1993;31:183–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lund VJ, Kennedy DW. Staging for rhinosinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;117:S35–S40. doi: 10.1016/S0194-59989770005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mongrain V, Hernandez SA, Pradervand S, et al. Separating the contribution of glucocorticoids and wakefulness to the molecular and electrophysiological correlates of sleep homeostasis. Sleep. 2010;33:1147–1157. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.9.1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Irwin MR, Olmstead R, Motivala SJ. Improving sleep quality in older adults with moderate sleep complaints: A randomized controlled trial of Tai Chi Chih. Sleep. 2008;31:1001–1008. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Litvack JR, Mace J, Smith TL. Role of depression in outcomes of endoscopic sinus surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;144:446–451. doi: 10.1177/0194599810391625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tosun F, Kemikli K, Yetkin S, Ozgen F, Durmaz A, Gerek M. Impact of endoscopic sinus surgery on sleep quality in patients with chronic nasal obstruction due to nasal polyposis. J Craniofac Surg. 2009;20:446–449. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e31819b97ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith TL, Mendolia-Loffredo S, Loehrl TA, Sparapani R, Laud PW, Nattinger AB. Predictive factors and outcomes in endoscopic sinus surgery for chronic rhinosinusitis. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:2199–2205. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000182825.82910.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alobid I, Benitez P, Bernal-Sprekelsen M, et al. Nasal polyposis and its impact on quality of life: comparison between the effects of medical and surgical treatments. Allergy. 2005;60:452–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2005.00725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krueger JM, Majde JA. Microbial products and cytokines in sleep and fever regulation. Crit Rev Immunol. 1994;14(3-4):355–379. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v14.i3-4.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alt JA, Smith TL. Chronic rhinosinusitis and sleep: a contemporary review. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2013;3:941–949. doi: 10.1002/alr.21217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bolger WE, Joshi AS, Spear S, Nelson M, Govindaraj K. Gene expression analysis in sinonasal polyposis before and after oral corticosteroids: a preliminary investigation. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;137:27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2007.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thomas KS, Motivala S, Olmstead R, Irwin MR. Sleep depth and fatigue: role of cellular inflammatory activation. Brain Behav Immun. 25:53–58. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.07.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Omdal R, Gunnarsson R. The effect of interleukin-1 blockade on fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis--a pilot study. Rheumatol Int. 2005;25:481–484. doi: 10.1007/s00296-004-0463-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Illi J, Miaskowski C, Cooper B, et al. Association between pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine genes and a symptom cluster of pain, fatigue, sleep disturbance, and depression. Cytokine. 58:437–447. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2012.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anisman H, Merali Z. Cytokines, stress and depressive illness: brain-immune interactions. Ann Med. 2003;35:2–11. doi: 10.1080/07853890310004075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baune BT, Ponath G, Rothermundt M, Riess O, Funke H, Berger K. Association between genetic variants of IL-1beta, IL-6 and TNF-alpha cytokines and cognitive performance in the elderly general population of the MEMO-study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008;33(1):68–76. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Palin K, Bluthe RM, Verrier D, Tridon V, Dantzer R, Lestage J. Interleukin-1beta mediates the memory impairment associated with a delayed type hypersensitivity response to bacillus Calmette-Guerin in the rat hippocampus. Brain Behav Immun. 2004;18:223–230. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Obal F, Jr, Krueger JM. Biochemical regulation of non-rapid-eye-movement sleep. Front Biosci. 2003;8:d520–d550. doi: 10.2741/1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Turnbull AV, Rivier CL. Regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis by cytokines: actions and mechanisms of action. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:1–71. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Quan N, Banks WA. Brain-immune communication pathways. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21:727–735. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Backhaus J, Junghanns K, Broocks A, Riemann D, Hohagen F. Test-retest reliability and validity of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index in primary insomnia. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:737–740. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00330-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Buysse DJ, Hall ML, Strollo PJ, et al. Relationships between the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), and clinical/polysomnographic measures in a community sample. J Clin Sleep Med. 2008;4:563–571. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mariman A, Vogelaers D, Hanoulle I, Delesie L, Pevernagie D. Subjective sleep quality and daytime sleepiness in a large sample of patients with chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) Acta clinica Belgica. 2012;67:19–24. doi: 10.2143/ACB.67.1.2062621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Irwin MR, Cole JC, Nicassio PM. Comparative meta-analysis of behavioral interventions for insomnia and their efficacy in middle-aged adults and in older adults 55+ years of age. Health Psychol. 2006;25:3–14. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Braeckman L, Verpraet R, Van Risseghem M, Pevernagie D, De Bacquer D. Prevalence and correlates of poor sleep quality and daytime sleepiness in Belgian truck drivers. Chronobiol Int. 2011;28:126–134. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2010.540363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]