Abstract

Objectives

This study sought to examine the relationship between erectile problems and cardiovascular disease mortality.

Background

While there are plausible mechanisms linking erectile dysfunction with coronary heart disease and stroke, studies are scarce.

Methods and Results

In a cohort analysis of a trial population (‘ADVANCE’), 6304 men aged 55-88 years with type 2 diabetes participated in a baseline medical examination when enquiries were made about erectile dysfunction. Over 5 years of follow-up, during which study members attended repeat clinical examinations, the presence of fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular disease outcomes, cognitive decline and dementia were ascertained. After adjusting for a range of covariates including existing illness, psychological health and classic cardiovascular disease risk factors, relative to those who were free of the condition, baseline erectile dysfunction was associated with an elevated risk of all cardiovascular disease events (hazard ratio; 95% confidence interval: 1.19; 1.08, 1.32), coronary heart disease (1.35; 1.16, 1.56) and cerebrovascular disease (1.36; 1.11, 1.67). Additionally, men who experienced erectile dysfunction at baseline and at two year follow-up had the highest risk of these outcomes.

Conclusions

In this cohort of men with type 2 diabetes, erectile dysfunction was associated with a range of cardiovascular disease events.

Keywords: coronary heart disease, epidemiology, erectile dysfunction, stroke

Erectile dysfunction – the inability to achieve and maintain a penile erection for satisfactory sexual performance(1) – can be highly prevalent, with some estimates as high as 80% in elderly men with co-morbidities such as diabetes.(2) Originally thought to be psychogenic or neuropathic in origin, several lines of evidence now suggest that the predominant aetiology is vascular.(3-5) Thus, risk factors for erectile dysfunction (e.g., smoking, raised blood pressure, obesity) appear to be the same as those for cardiovascular disease,(3) and the occurrence of erectile dysfunction rises monotonically with a progressive clustering of these indices.

Erectile dysfunction appears to be associated with an increased risk clinical events of cardiovascular disease,(6,7) coronary heart disease (CHD)(8-10) and stroke(9), but prospective cohort studies, which provide the best observational evidence of association, are very scarce. We address this paucity of evidence by utilising data from cohort analyses of a large, well characterised, randomised controlled trial.

Methods

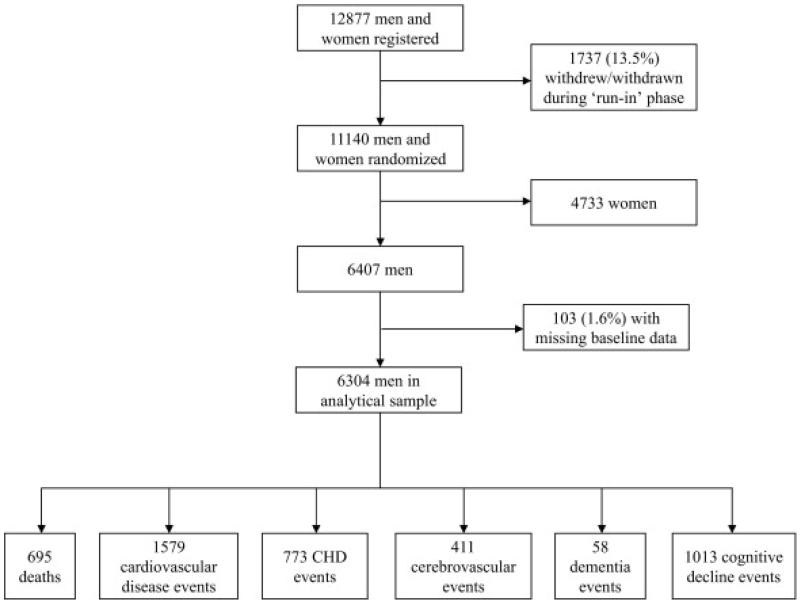

The Action in Diabetes and Vascular disease: Preterax and Diamicron Modified-Release Controlled Evaluation (ADVANCE) trial, described in detail elsewhere,(11) was designed to investigate the separate effects of routine blood pressure lowering and intensive blood glucose control on vascular outcomes in people with existing type 2 diabetes. In brief, in 2001/3, 12,877 men and women aged 55-88 years with type 2 diabetes and a history of major macro- or microvascular disease, or at least one other cardiovascular risk factor, were recruited from 215 centres (20 countries). After an initial ‘run-in’ phase, 11,140 individuals (6407 men) were randomised using a factorial design to perindopril-indapamide or placebo, and to intensive blood glucose control based on gliclazide MR or to standard blood glucose control. The flow of patients through the study is depicted in figure 1. For the purposes of the present analyses, data from the trial are utilised using a prospective cohort study design, as we have done previously.(12) Approval to conduct the trial was obtained from the ethics committee of each study centre; all participants provided written informed consent.

Figure 1. Flow of Study Participants Through the ADVANCE Trial.

Flow of participants into the ADVANCE (Action in Diabetes and Vascular Disease: Preterax and Diamicron Modified-Release Controlled Evaluation) trial, focusing on men who reported their erectile function and who had complete covariate data at baseline. The causes and numbers of deaths and events in these men after 5 years of follow-up are provided in the last row. CHD = coronary heart disease.

Baseline examination

At study induction, participants responded to questionnaire enquiries and took part in a medical examination. Glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c), blood cholesterol (and fractions), blood pressure, resting heart rate, and serum creatinine were measured using standard protocols. Height and weight were used to derive body mass index (weight[kg]/height[m]2). Nurses administered a series of questions regarding ethnicity, educational attainment, physical activity, alcohol intake, cigarette smoking habit, major chronic disease, assistance with activities of daily living, medications used to control diabetes (e.g., gliclazide MR, metformin) and related conditions (e.g. beta-blocker, thiazide). The presence of minor psychiatric disorder (anxiety and depression) was ascertained by use of the EuroQol5d.(13,14) Cognitive function was assessed using the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) where low scores indicate impaired performance.(15) Individuals with MMSE score < 24, or where the nurse suspected dementia, were referred to a medically-qualified specialist for diagnosis of dementia according to DSM criteria.(16) In order to maintain accurate self-reported information, those with either a contemporaneous or prior diagnosis of dementia did not enter the study. Nurses also asked all male subjects whether they had erectile dysfunction (response: yes/no).

Ascertainment of cardiovascular disease, dementia and cognitive impairment during follow-up

Fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular disease outcomes were ascertained using a variety of sources. Information on cause of death (certification, autopsy report, clinical notes) were scrutinised by an Endpoint Adjudication Committee and a coding made according to the 10th revision of the International Classification of Diseases.(17) For non-fatal outcomes, where applicable, clinical notes, computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging reports (for suspected stroke), laboratory biomarkers (e.g., creatine kinase, troponins) and ECG reports (for suspected myocardial infarction) were utilised. A coronary heart disease event was denoted by death due to this condition [including sudden death], non-fatal myocardial infarction, silent myocardial infarction, coronary revascularisation, or hospital admission for unstable angina.(18) A cerebrovascular event was defined as a death due to this condition or non-fatal stroke, transient ischaemic attack, or subarachnoid haemorrhage.(18) The protocol used to identify dementia at follow-up was the same as that for baseline (described above). Cognitive decline was defined as a reduction in MMSE score of 3 or more points as compared with baseline score.

Statistical analyses

Baseline data were missing for 103 men, resulting in an analytical sample of 6304. Having first determined that the proportional hazards assumption had not been violated, Cox models were used to estimate hazard ratios, with accompanying 95% confidence intervals, to summarise the association between erectile function and the various health outcomes.(19) Hazard ratios were first computed separately in the treatment and placebo groups. With no indication that treatment allocation modified the association of erectile dysfunction on the outcomes (p-value for interaction>0.1), data were pooled and all analyses were adjusted for treatment.

In sub-group analyses of men who did not develop any of the outcomes of interest between baseline and follow-up at 24 months (N=5427), we examined the possibility that incident erectile problems may be related to cardiovascular disease and other outcomes. Based on the dichotomous questionnaire responses from baseline and 24 month follow-up, we therefore derived four groups: men without erectile dysfunction at either time point; men who had erectile problems at baseline but reported no such dysfunction at follow-up; men who developed erectile dysfunction between baseline and follow-up; and men who had erectile dysfunction at both baseline and follow-up (‘unrelenting’ erectile dysfunction). All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC).

Results

In table 1 we show the baseline characteristics of study participants according to erectile dysfunction status. Half of the men in ADVANCE (3158/6304) reported erectile dysfunction at the baseline examination. With few exceptions, men with erectile dysfunction had less favourable levels of baseline cardiovascular disease risk factors, morbidity and drug use than those reporting no such problems. However, although statistically significant at conventional levels owing to the large sample size, absolute differences in these characteristics between men with and without erectile dysfunction were generally modest in magnitude. Men with erectile dysfunction were older, heavier, and had lower cognitive function. These men were also more likely to have chronic ill health as indexed by a range of baseline indices. While men with erectile dysfunction were also less likely to be physically active, contrarily, they were less likely to smoke and had lower total blood cholesterol, diastolic blood pressure, and resting heart rate.

Table 1. Erectile dysfunction and baseline characteristics in men in ADVANCE (N=6304).

| Erectile dysfunction | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| No (n=3146) | Yes (n=3158) | ||

| Mean (SD) | |||

| Age at baseline examination (yr) | 64.8 (6.3) | 67.0 (6.4) | 0.001 |

| Age at completion of education (yr) | 19.8 (7.4) | 19.0 (7.2) | 0.001 |

| Haemoglobin A1c (%) | 7.4 (1.5) | 7.5 (1.50) | 0.004 |

| Height (cm) | 171.2 (7.0) | 171.2 (7.3) | 0.843 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 27.8 (4.5) | 28.2 (4.9) | 0.005 |

| Total blood cholesterol (mmol/L) | 5.0 (1.1) | 4.9 (1.1) | 0.002 |

| High density lipoprotein blood cholesterol (mmol/L) | 1.19 (0.3) | 1.19 (0.3) | 0.634 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 143.8 (20.9) | 145.8 (21.2) | 0.002 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 81.6 (11.0) | 81.0 (10.7) | 0.026 |

| Resting heart rate (BPM) | 73.4 (12.5) | 73.0 (12.4) | 0.283 |

| Serum creatinine (umol/L) | 91.9 (22.1) | 94.7 (26.4) | 0.001 |

| Cognitive function (MMSE) | 28.8 (1.7) | 28.5 (1.8) | 0.001 |

| Quality of life (EQ-5d) | 0.86 (0.2) | 0.82 (0.2) | 0.001 |

| Diabetes duration (years) | 7.5 (6.2) | 8.5 (6.7) | 0.001 |

| No. occasions exercise ≥ 15 mins/week | 4.0 (6.3) | 3.3 (5.6) | 0.001 |

| Number of alcoholic drinks/week | 4.5 ( 9.7) | 5.0 ( 9.8) | 0.057 |

| N (Percentage) | |||

| Caucasian/European ethnicity | 1852 (58.9) | 2037 (64.5) | 0.001 |

| Current cigarette smoker | 604 (19.2) | 485 (15.4) | 0.001 |

| Use of Metformin or Beta-blocker | 2210 (70.2) | 2227 (70.5) | 0.814 |

| Require assistance with daily activities | 67 (2.1) | 111 (3.5) | 0.001 |

| History of major macrovascular diseasea | 1060 (33.7) | 1267 (40.1) | 0.001 |

| History of major microvascular diseaseb | 280 (8.9) | 385 (12.2) | 0.001 |

| History of major diabetic disease | 183 (5.8) | 267 (8.5) | 0.001 |

A history of major macrovascular disease is defined as any of the following: stroke, myocardial infarction, hospital admission for transient ischaemic attack, hospital admission for unstable angina, coronary revascularisation, peripheral revascularisation, or amputation secondary to vascular disease.

A history of major microvascular disease is defined as any of the following: macroalbuminuria (urinary albumin-creatinine ratio, >300 μg/mg), proliferative diabetic retinopathy, retinal photocoagulation therapy, macular oedema, or blindness in one eye thought to be caused by diabetes.

During a mean of 5 years of follow-up, there were 695 deaths from any cause, 1579 fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular disease events, 773 fatal and non-fatal CHD events, 411 fatal and non-fatal cerebrovascular disease events, 58 incident cases of dementia and 1013 of cognitive decline. In table 2 we show the relation between erectile dysfunction and a range of health outcomes. Considering first the outcomes of total mortality, cardiovascular disease, CHD and cerebrovascular disease, it is unsurprising that, with both exposure and outcomes strongly age-related, controlling for age had a marked attenuating effect on all the hazard ratios. In analysis adjusted for age and treatment group, relative to men who were free of erectile problems at baseline, those with erectile dysfunction experienced an elevated risk of between 34% and 53%. Adjusting for existing illness and medication led to some attenuation in these effects. Of the cardiovascular disease risk factors, adding the psychological indices (quality of life and cognitive function) to the multivariable model appeared to explain some of the effect of erectile problems on total mortality, all cardiovascular disease events, all CHD and cerebrovascular events. After multiple adjustment for a range of baseline characteristics, some attenuation was again apparent but, with the exception of total mortality, gradients held at conventional levels of statistical significance. Erectile problems was associated with an increased risk of both these outcomes but most effect estimates were not statistically significant at conventional levels.

Table 2. Hazard ratios (95% CI) for the relation of baseline erectile dysfunction with selected outcomes in men in ADVANCE (N=6304).

| Adjustment | Total mortality (n=695) | Cardiovascular disease (n=1579) | CHD (n=773) | Cerebrovascular disease (n=411) | Dementia (n=58) | Cognitive decline (n=1013) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | 1.58 (1.36, 1.84) | 1.43 (1.30, 1.58) | 1.62 (1.40, 1.87) | 1.57 (1.29, 1.91) | 2.09 (1.19, 3.65) | 1.25 (1.11, 1.42) |

| Treatment + age | 1.34 (1.15, 1.56) | 1.35 (1.22, 1.49) | 1.53 (1.32, 1.78) | 1.46 (1.19, 1.78) | 1.54 (0.88, 2.70) | 1.14 (1.00, 1.29) |

| Treatment, age + existing illness | 1.25 (1.07, 1.45) | 1.27 (1.15, 1.41) | 1.42 (1.22, 1.64) | 1.37 (1.12, 1.68) | 1.50 (0.85, 2.64) | 1.13 (0.99, 1.28) |

| Treatment, age + behavioural cardiovascular risk factors | 1.33 (1.14, 1.55) | 1.34 (1.21, 1.48) | 1.52 (1.31, 1.76) | 1.46 (1.19, 1.78) | 1.59 (0.91, 2.80) | 1.15 (1.01, 1.30) |

| Treatment, age + physiological cardiovascular risk factors | 1.29 (1.10, 1.50) | 1.30 (1.18, 1.44) | 1.48 (1.28, 1.72) | 1.45 (1.19, 1.77) | 1.54 (0.87, 2.71) | 1.14 (1.00, 1.29) |

| Treatment, age + psychological cardiovascular risk factors | 1.25 (1.07, 1.46) | 1.28 (1.16, 1.42) | 1.46 (1.26, 1.70) | 1.41 (1.15, 1.73) | 1.56 (0.88, 2.78) | 1.13 (1.00, 1.28) |

| Treatment, age + socio-economic cardiovascular risk factors | 1.32 (1.13, 1.54) | 1.34 (1.21, 1.48) | 1.53 (1.32, 1.77) | 1.45 (1.19, 1.77) | 1.52 (0.87, 2.68) | 1.13 (1.00, 1.28) |

| Multiple adjusted | 1.16 (0.99, 1.35) | 1.19 (1.08, 1.32) | 1.35 (1.16, 1.56) | 1.36 (1.11, 1.67) | 1.58 (0.88, 2.82) | 1.12 (0.98, 1.27) |

In all analyses the referent group is men without erectile dysfunction at baseline. Existing illness: comprises one or more of the following: use of Metformin/beta-blockers, history of macrovascular or microvascular disease, or those requiring assistance with daily activities, plus diabetes duration; Behavioural cardiovascular disease risk factors: Cigarette smoking, alcohol intake, vigorous physical activity in previous week; Physiological cardiovascular disease risk factors: Haemoglobin A1c, Creatinine, body mass index, total cholesterol, high density lipoprotein cholesterol, resting heart rate, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure; Psychological cardiovascular disease risk factors: Quality of life (EQ-5d score), and Mini Mental State Exam Score; Socio-economic cardiovascular disease risk factors: Age at completion of highest level of education, height; Multiple adjusted: All above covariates plus treatment allocation and ethnicity.

Finally, we examined the association of change in erectile function status between baseline and 24 month follow-up with the future risk of new events and deaths in a sub-sample of the population who remained free of these outcomes during this 2 year period (table 3). For total mortality, cardiovascular disease, CHD and cerebrovascular disease, as anticipated, the highest rates were evident in men whose symptoms of erectile dysfunction persisted between baseline and follow-up 24 months later, although the confidence intervals for total mortality included unity. Similar patterns of association were apparent for dementia and cognitive decline, although the number of events for the former was very low.

Table 3. Multiple adjusted hazard ratios (95% CI) for the relation of change in erectile dysfunction status between baseline and 24 months follow-up with selected outcomes in men in ADVANCE (N=5427).

| ED at baseline | ED at 24months | N | Total mortality (n=388) | Cardiovascular disease (n=965) | CHD (n=399) | Cerebrovascular disease (n=221) | Dementia (n=48) | Cognitive decline (n=913) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | No | 1964 | 1 (ref) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | No | 814 | 1.05 (0.75, 1.48) | 1.24 (1.01, 1.52) | 1.13 (0.81, 1.56) | 1.18 (0.76, 1.83) | 1.30 (0.34, 5.00) | 1.34 (1.10, 1.65) |

| No | Yes | 618 | 1.08 (0.74, 1.56) | 0.98 (0.78, 1.25) | 1.07 (0.74, 1.56) | 1.05 (0.65, 1.70) | 3.70 (1.19, 11.46) | 1.07 (0.85, 1.36) |

| Yes | Yes | 2031 | 1.29 (1.00, 1.66) | 1.28 (1.09, 1.50) | 1.45 (1.13, 1.85) | 1.44 (1.04, 2.01) | 3.11 (1.18, 8.18) | 1.32 (1.12, 1.55) |

| P-trend | - | 0.0419 | 0.0081 | 0.0032 | 0.0365 | 0.0089 | 0.0051 |

Multiple adjustment as per table 2. Analytical sample is based on a sub-group of men who did not develop any of the outcomes of interest between baseline and follow-up at 24 months

Discussion

The main finding of this study was that erectile dysfunction was associated with total mortality, cardiovascular disease, CHD and cerebrovascular disease. This is one of the few prospective cohort investigations to examine these associations and, by virtue of the high number of events, the most powerful. Although controlling for the classic cardiovascular disease risk factors (smoking, raised blood pressure and blood cholesterol) had little impact on the magnitude of these gradients, marked attenuation was apparent when other covariates such as existing illness, medication and psychological distress were added to the multivariable model. However, statistical significance at conventional levels was typically retained.

Prior studies

Our finding that erectile dysfunction apparently confers an increased risk of CHD is supported in the few other prospective cohort studies conducted which are generally less well controlled than our own, and, with few exceptions,(9) markedly smaller in scale. To our knowledge, only one other study has examined the role of erectile problems in the aetiology of stroke,(9) and that too found a positive association.

Plausible explanations

Potential non-causal explanations for the apparent impact of erectile dysfunction on these chronic cardiovascular disease outcomes include bias and confounding. In the present study, drop-out by the original study members was very low. We also adjusted for a very wide range of confounding variables and these gradients, while attenuated, remained statistically significant at conventional levels. The effect that remained for erectile dysfunction in relation to the various outcomes is probably too large to be explained by residual confounding in this well characterised study but we of course cannot rule out the explanatory power of unmeasured (e.g., systemic inflammation) or unknown covariates.

The absence of convincing alternative explanations for these associations raises the possibility of a real effect of erectile dysfunction on the outcomes herein. One obvious possibility is that erectile dysfunction results from peripheral neuropathy – that is, damage to nerves of the peripheral nervous system. Another option is that, given that the penis is an extensively vascularised organ, erections are, to a large degree, a vascular event. With the penile (1-2 mm) arteries being substantially narrower than those of the coronary (3-4 mm), carotid (5-7 mm) and femoral (6-8 mm) arteries,(20) as described, for the same quantity of atherosclerosis, erectile dysfunction may precede a similar vascular event in the heart.

Study strengths and limitations

While the present study has a number of strengths, including the detailed range of covariates collected, the large sample size, repeat measurement of erectile dysfunction, and the fact that it is the first to examine links with dementia and cognitive function, it of course also has its limitations. While it may be testimony to the robustness of the relation that a very simple question regarding erectile dysfunction was linked to cardiovascular disease, we did not capture information on severity of exposure by, for instance, utilising the International Index of Erectile Dysfunction.(21) This would have allowed us to examine dose-response effects.

In conclusion, we demonstrated associations between erectile dysfunction and a range of cardiovascular disease outcomes. However, rather than having a direct, independent effect on cardiovascular disease, it is more likely that erectile dysfunction is a marker of CVD risk.

Acknowledgments

ADVANCE was funded by grants from Servier and the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. These sponsors had no role in the design of the study, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, and the writing of the manuscript.. The Management Committee, whose membership did not include any sponsor representatives, had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. The authors had full access to the study data and take responsibility for the accuracy of the analysis. The Medical Research Council (MRC) Social and Public Health Sciences Unit receives funding from the UK MRC and the Chief Scientist Office at the Scottish Government Health Directorates. The Centre for Cognitive Ageing and Cognitive Epidemiology is supported by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, the Economic and Social Research Council, the Medical Research Council, and the University of Edinburgh as part of the cross-council Lifelong Health and Wellbeing initiative. David Batty is a Wellcome Trust Career Development Fellow (WBS U.1300.00.006.00012.01). Rachel Huxley holds a Career Development Award from the National Heart Foundation of Australia. Sébastien Czernichow is supported by a fellowship from the Institut Servier-France and Assistance Publique – Hôpitaux de Paris, France.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: John Chalmers holds research grants from Servier; John Chalmers, Bruce Neal, Anushka Patel, and Mark Woodward have received lecturing fees from Servier.

References

- 1.NIH Consensus Conference Impotence. NIH Consensus Development Panel on Impotence. JAMA. 1993;270:83–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giuliano FA, Leriche A, Jaudinot EO, de Gendre AS. Prevalence of erectile dysfunction among 7689 patients with diabetes or hypertension, or both. Urology. 2004;64:1196–1201. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.08.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kloner RA. Erectile dysfunction as a predictor of cardiovascular disease. Int J Impot.Res. 2008;20:460–465. doi: 10.1038/ijir.2008.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fung MM, Bettencourt R, Barrett-Connor E. Heart disease risk factors predict erectile dysfunction 25 years later: the Rancho Bernardo Study. J Am.Coll.Cardiol. 2004;43:1405–1411. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chew KK, Bremner A, Jamrozik K, Earle C, Stuckey B. Male erectile dysfunction and cardiovascular disease: is there an intimate nexus? J Sex Med. 2008;5:928–934. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gazzaruso C, Solerte SB, Pujia A, Coppola A, Vezzoli M, Salvucci F, Valenti C, Giustina A, Garzaniti A. Erectile dysfunction as a predictor of cardiovascular events and death in diabetic patients with angiographically proven asymptomatic coronary artery disease: a potential protective role for statins and 5-phosphodiesterase inhibitors. J Am.Coll.Cardiol. 2008;51:2040–2044. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.10.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schouten BW, Bohnen AM, Bosch JL, Bernsen RM, Deckers JW, Dohle GR, Thomas S. Erectile dysfunction prospectively associated with cardiovascular disease in the Dutch general population: results from the Krimpen Study. Int J Impot.Res. 2008;20:92–99. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ma RC, So WY, Yang X, Yu LW, Kong AP, Ko GT, Chow CC, Cockram CS, Chan JC, Tong PC. Erectile dysfunction predicts coronary heart disease in type 2 diabetes. J Am.Coll.Cardiol. 2008;51:2045–2050. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thompson IM, Tangen CM, Goodman PJ, Probstfield JL, Moinpour CM, Coltman CA. Erectile dysfunction and subsequent cardiovascular disease. JAMA. 2005;294:2996–3002. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.23.2996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Montorsi P, Ravagnani PM, Galli S, Rotatori F, Veglia F, Briganti A, Salonia A, Deho F, Rigatti P, Montorsi F, Fiorentini C. Association between erectile dysfunction and coronary artery disease. Role of coronary clinical presentation and extent of coronary vessels involvement: the COBRA trial. Eur.Heart J. 2006;27:2632–2639. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The ADVANCE Collaborative group Study rationale and design of ADVANCE: action in diabetes and vascular disease--preterax and diamicron MR controlled evaluation. Diabetologia. 2001;44:1118–1120. doi: 10.1007/s001250100612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kengne AP, Czernichow S, Huxley R, Grobbee D, Woodward M, Neal B, Zoungas S, Cooper M, Glasziou P, Hamet P, Harrap SB, Mancia G, Poulter N, Williams B, Chalmers J. Blood Pressure Variables and Cardiovascular Risk. New Findings From ADVANCE. Hypertension. 2009 doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.133041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The EuroQol Group EuroQol--a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16:199–208. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kind P, Dolan P, Gudex C, Williams A. Variations in population health status: results from a United Kingdom national questionnaire survey. BMJ. 1998;316:736–741. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7133.736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crum RM, Anthony JC, Bassett SS, Folstein MF. Population-based norms for the Mini-Mental State Examination by age and educational level. JAMA. 1993;269:2386–2391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Psychological Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. American Psychological Association; Washington DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anon. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems. 10th revision. WHO; Geneva: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patel A, MacMahon S, Chalmers J, Neal B, Billot L, Woodward M, Marre M, Cooper M, Glasziou P, Grobbee D, Hamet P, Harrap S, Heller S, Liu L, Mancia G, Mogensen CE, Pan C, Poulter N, Rodgers A, Williams B, Bompoint S, de Galan BE, Joshi R, Travert F. Intensive blood glucose control and vascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N.Engl.J.Med. 2008;358:2560–2572. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cox DR. Regression models and life-tables. J R Stat Soc Series B Stat Methodol. 1972;34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Montorsi P, Montorsi F, Schulman CC. Is erectile dysfunction the “tip of the iceberg” of a systemic vascular disorder? Eur. Urol. 2003;44:352–354. doi: 10.1016/s0302-2838(03)00307-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Montorsi F, Briganti A, Salonia A, Rigatti P, Margonato A, Macchi A, Galli S, Ravagnani PM, Montorsi P. Erectile dysfunction prevalence, time of onset and association with risk factors in 300 consecutive patients with acute chest pain and angiographically documented coronary artery disease. Eur.Urol. 2003;44:360–364. doi: 10.1016/s0302-2838(03)00305-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]