Abstract

Macrophages function as phagocytes and antigen-presenting cells in the body. As has been demonstrated in mammals, administration of clodronate [dichloromethylene bisphosphonate (Cl2MBP)] encapsulated liposomes results in depletion of macrophages. Although this compound has been used in chickens, its effectiveness in depleting macrophages has yet to be fully determined. Here, we show that a single administration of clodronate liposomes to chickens results in a significant depletion of macrophages within the spleen and lungs of chickens up to 4 d post-treatment. This finding suggests that, in order to obtain depletion of macrophages in chickens for greater than 5 d, it is necessary to administer clodronate liposomes 4 d apart. The study also showed that 2 treatments of clodronate liposomes at 4-day intervals resulted in the depletion of macrophages for up to 10 d. The findings of the present study will encourage more precise studies to be done on the potential roles of macrophages in immune responses and in the pathogenesis of microbial infections in chickens.

Résumé

Les macrophages agissent comme phagocytes et cellules présentatrices d’antigènes dans l’organisme. Tel que démontré chez les mammifères, l’administration de liposomes encapsulés de clodronate [biphosphanate de dichlorométhylène (Cl2MBP)] cause une déplétion des macrophages. Bien que ce composé ait été utilisé chez les poulets, son efficacité à causer une déplétion des macrophages reste encore à être entièrement déterminée. Nous démontrons ici que l’administration d’une dose unique de liposomes de clodronate à des poulets a causé une déplétion significative des macrophages dans la rate et les poumons de poulets jusqu’à 4 j post-traitement. Cette trouvaille suggère qu’afin d’obtenir une déplétion des macrophages chez les poulets pour plus de 5 j, il est nécessaire d’administrer des liposomes de clodronate à un intervalle de 4 j. Cette étude a aussi démontré que deux traitements de liposomes de clodronate à 4 j d’intervalle a causé une déplétion des macrophages pour une durée allant jusqu’à 10 j. Les présentes trouvailles encourageront la mise en place d’études plus précises sur les rôles potentiels des macrophages dans la réponse immunitaire et dans la pathogénèse des infections microbiennes chez les poulets.

(Traduit par Docteur Serge Messier)

Introduction

Macrophages play an essential role in innate responses when protecting animals from the deleterious effects of microbial infections and potentially harmful substances. In addition to acting as phagocytes, they also act as antigen-presenting cells and sources of cytokines and chemokines, facilitating the development of antigen-specific adaptive immune responses. Unlike mammals, healthy birds have very few resident macrophages in the abdominal cavity as well as in the respiratory tract (1). Although, this may indicate that macrophages are quantitatively less important in avian species compared with mammals, avian species rely more on a rapid influx of macrophages into the site of infection for phagocytic activity against pathogens (1) than resident macrophages.

Macrophages are shown to play critical roles in the pathogenesis of many microbial infections (2–5). Avian macrophages express macrophage/monocyte marker KUL01 (6). The hyaluronan receptor CD44 has also been found to be expressed on macrophages in mammals (7). As has been described for mammals, the anti-CD44 monoclonal antibody is known to bind to the CD44 isoform present on avian macrophages but not monocytes (8).

Dichloromethylene bisphosphonate or clodronate (Cl2MBP), when encapsulated in liposomes, induces apoptosis of macrophages. As the cells phagocytose the liposomes1 and degrade them through fusion with components of the lysosomal pathway, clodronate is released into the interior of the cell where it accumulates to lethal levels. The use of this drug is considered to be the best and most efficacious approach for macrophage depletion in mammals (9,10), and clodronate-encapsulated liposomes have been used to determine the effects of macrophage depletion on the pathogenesis of various infection models, such as dengue (2), Taenia crassiceps cysticercosis (3), influenza virus (4) and measles (5).

Use of clodronate-encapsulated liposomes has not been extensively studied in chickens (11–14). Depletion efficiency of macrophages has been shown indirectly using reduced nitric oxide (NO) or antibody production against the model antigen, keyhole limpet hemocyanin following clodronate treatment (11,14). Jeurissen et al (12) have qualitatively shown immunohistochemical evidence of macrophage depletion in clodronate-treated spleens after day 1, day 2, and day 4, but not day 7 post-treatments. However, this study did not record data of spleen macrophage depletion on days 5 and 6. Furthermore, there are no records of macrophage depletion in non-lymphoid organs. However, due to a lack of quantitative data on macrophage depletion following clodronate treatment in spleen and lungs, the effectiveness involved in depleting chicken macrophages using clodronate-encapsulated liposomes remains unclear. We hypothesized that the use of clodronate liposomes is effective in depleting macrophages in both lymphoid and non-lymphoid organs in chickens, and that the effectiveness of such depletion could be determined by quantifying macrophage loss using macrophage numbers in both treated and control animals. Using quantitative phenotypic data, we show that the administration of clodronate-encapsulated liposomes is effective in depleting macrophages in lymphoid and non-lymphoid organs.

Materials and methods

Animals

All procedures were approved by the University of Calgary’s Veterinary Sciences Animal Care Committee and conducted according to the ethical standards set by the Canadian Council on Animal Care (15). One-day-old, unsexed, commercial layer chickens (white leghorn), obtained from Rochester Hatchery (Westlock, Alberta), were raised up to 28 d of age and used in experiments. The chickens were not immunized to prevent any diseases and were housed in high containment poultry isolators at the University of Calgary’s Spyhill campus, with ample access to food and water that were both nutritionally complete and appropriate for the age of the chickens.

Macrophage depletion

Clodronate, encapsulated in liposomes, was used to deplete macrophages in chicken lung and spleen. Clodronate liposomes were prepared as described earlier (9). Control liposomes contained phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) only. Each animal received 0.5 mL (5 mg of clodronate per 1 mL of the total suspension volume) of clodronate liposomes or control liposomes intra-abdominally. For intra-abdominal administration, the birds were restrained so that the ventral side of the bird was up and a 28-gauge needle and 1 mL syringe was used to deliver the liposomes in the middle of ventral midline between scar of yolk sac attachment and cloaca. The clodronate and control liposomes were obtained from the Foundation Clodronate Liposomes, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Experimental design

Design of the experiments has been summarized in Table I. The first experiment was done to evaluate the macrophage depletion using immunohistochemical analysis of the spleen and lungs. A flow cytometry assay was optimized for the quantification of macrophages in the lungs and spleen using 28-day-old chickens (n = 2). This optimized flow cytometry technique was then used for evaluation of macrophage depletion in the spleen and lungs 1 and 5 d post-treatment (single dose of clodronate) and 6 d post-treatment of second clodronate treatment (2 doses of clodronate administered 4 d apart).

Table I.

Outline of experimental design

| Age/number of chickens | Time of treatment | Days-post treatment (dpt) of sampling | Tissue collected | Method of analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14-days-old; | Time zero | 1 and 5 dpt | Lung and spleen | Immunohistochemistry |

| PBS, n = 3; | ||||

| Clodronate, n = 3 | ||||

| 8 to 14-days-old; | Time zero | 1 dpt | Lung and spleen | Flow cytometry |

| PBS, n = 10; | ||||

| Clodronate, n = 11 | ||||

| 8 to 14-days-old; | Time zero | 5 dpt | Lung and spleen | Flow cytometry |

| PBS, n = 8; | ||||

| Clodronate, n = 8 | ||||

| 11-days-old; | Time zero for 1st treatment and 4 dpt for 2nd treatment | 6 dpt from second treatment | Lung and spleen | Flow cytometry |

| PBS, n = 5; | ||||

| Clodronate, n = 5 | ||||

PBS — phosphate-buffered saline.

Spleen and lung mononuclear cell isolation

The chicken spleen and lungs were dissected out from the animals and rinsed multiple times in cold Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS) to reduce the blood contamination. The spleens were crushed using a sterile syringe bottom, filtered through a 40 μm cell strainer (VWR, Edmonton, Alberta) and the cells were collected. Using a sterile scalpel and forceps, the lungs were minced to approximately 5 mm fragments and soaked in 400 U/mL collagenase type I solution (Sigma-Aldrich, Oakville, Ontario) for 30 min at 37°C. Dispersed cells and tissue fragments were separated from larger pieces using a 40 μm cell strainer. The filtered lung and spleen cells were pelleted at 233 × g for 10 min (4°C), followed by re-suspension in HBSS and carefully layered onto 4 mL Histopaque 1077 (GE Health Care, Mississauga, Ontario) in a 15 mL conical tube at room temperature (with a 1:1 ratio of cell suspension). The layered cells were spun for 40 min at 400 × g at 20°C. The cloudy layer, rich in mononuclear cells, was collected and pelleted, washed with HBSS, and the cells were suspended in complete medium (Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium 1640 supplemented with 2 mM/l L-glutamine, 1% penicillin-streptomycin and 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum) and the cells were counted.

Immunohistochemistry and histological observations

The dissected lung and spleen tissues were placed on cryomolds filled with optimal cutting temperature compound (OCT) and maintained in dry ice. The lung and spleen tissue samples preserved in embedding medium, OCT (−80°C) were sectioned at 5 μm using a microtome-cryostat (LEICA CM 3050 S; Vashaw Scientific, Norcross, Atlanta, Georgia, USA), adhered to high affinity micro slides (Superfrost plus; VWR Labshop, Batavia, Illinois, USA), and kept at −20°C until used. On the day of staining, the sections (kept overnight at room temperature) were fixed in ice cold acetone, the endogenous peroxidase activity of the section was quenched by treating the tissue section with 3% hydrogen peroxide made in 0.3% goat serum-PBS for 10 min and then blocked (30 min) with 5% goat serum in PBS (v/v). Then, the sections were incubated in a 1:400 dilution of mouse anti-chicken macrophage/monocyte monoclonal antibody, KUL01 (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, Alabama, USA) for 30 min followed by incubation in 1:250 biotinylated goat anti-mouse IgG (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, California, USA). Avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex (ABC) system (Vectastain® ABC kit, Vector Laboratories) was used for staining. Localization of the antigen was visualized by incubation of the sections with 3,3-diaminobenzidine-H2O2 solution (DAB substrate kit for peroxidase; Vector Laboratories). The slides were counterstained with Harris hematoxylin (Fisher Scientific, Kalamazoo, Michigan, USA) and mounted in Cytoseal-60 (Richard-AllanScientific, Kalamazoo, Michigan, USA).

Three clodronate-treated and 3 PBS liposome-treated animals were examined randomly for 1 and 5 d post-treatment for the enumeration of macrophages in spleen and lungs. The intensity of immunoperoxidase-positive cells in 5 highly infiltrated fields at 20× magnification were assessed using computer software (Photoshop Creative Suite 6, Adobe Systems Incorporated, San Jose, California, USA). Briefly, the total number of pixels present in each image was recorded. Then the image was zoomed in 500% and using the eyedropper tool, a reference color was selected. Then the pencil tool was used to place a reference color pixel. The magic wand tool was used to select a single pixel for the reference color, which then selected all pixels of that color with a tolerance rate of 70. The tolerance rate helped pick pixels across a span of multiple shades of the reference color. The number of pixels were then counted and recorded.

Flow cytometry

Standard flow cytometry procedures were used in the experiments. Briefly, the isolated mononuclear cells were washed with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) fraction V (w/v; OmniPur; EMD, Darmstadt, Germany) made in PBS and centrifuged for 10 min at 211 × g (4°C) and then suspended in 100 μL of 1:100 chicken serum (diluted in 1% BSA) for fragment crystallizable (Fc) region blocking. Following centrifugation once again, cells were resuspended in the dark with a final concentration of 0.5 μg/mL (100 μL) phycoerythrin (PE)-labelled mouse anti-chicken KUL01 (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, Alabama, USA) or 0.5 μg/mL allophycocyanin (APC)-labelled mouse anti-chicken cluster of differentiation (CD) 44 (Southern Biotech) monoclonal antibodies, with respective isotype controls or 1% BSA (unstained controls) on ice for 30 min. Finally, cells were washed twice with 1% BSA. Flow cytometry samples were analyzed with a BD LSR II (BD Biosciences, Mississauga, Ontario). Excitation was done with a 488 nm argonion laser and the emission collected using a 660/20 nm band pass filter for APC conjugates and 585/42 nm BP filter for PE conjugates.

Data analysis

Computer software (FlowJo, version 7.6.4; Ashland, Oregon, USA) was used to complete the flow cytometry data visualization and analysis. Data were analyzed using a 2-tailed Student’s t-test (GraphPad Prism 5 Software, La Jolla, California, USA). A 2-tailed Student’s t-test was also done to quantify and compare the intensity of immunoperoxidase-stained macrophages in PBS- and clodronate liposome-treated animals. Significance was measured at a P-value of ≤ 0.05.

Results

Clodronate liposomes administered as a single treatment are efficacious in depleting avian macrophages from spleen and lungs at 1 d but not 5 d following treatment

Immunohistochemical analysis of spleen and lung sections

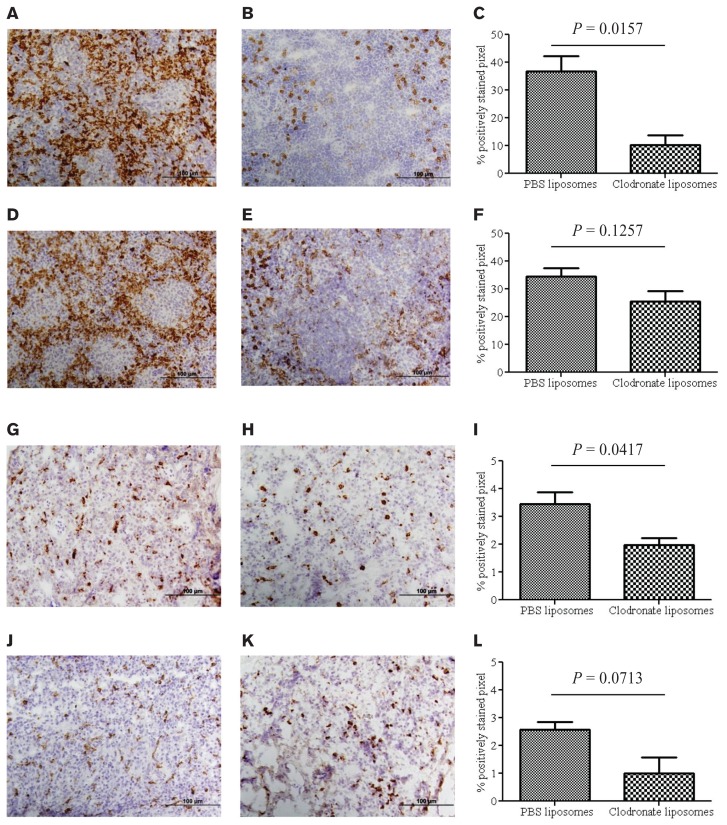

Lung and spleen sections of clodronate and PBS liposome-treated chickens were subjected to immunohistochemistry staining using the monocyte/macrophage monoclonal antibody KUL01. A significant depletion of macrophages (Figure 1C; P = 0.0157) was observed in clodronatetreated chicken spleens 1 d post-treatment compared to PBS liposome-treated chickens (Figures 1A, 1B, 1C). Contrary to 1-day post-treatment data, the number of macrophages within the spleen was not significantly altered (Figure 1F; P = 0.127) 5 d after treatment between PBS-treated and clodronate-treated chickens (Figures 1D, 1E, 1F).

Figure 1.

Immunohistochemical analysis of spleen and lung sections, showing significant reduction of macrophages 1 d, but not 5 d, post-treatment with intra-abdominal single dose of clodronate liposomes. A group of 14-day-old commercial chickens were treated intra-abdominally once with 0.5 mL of clodronate- or PBS-liposomes. One day or 5 d post-treatment macrophages were stained. A, B — Macrophages in spleen treated with PBS- or clodronate-liposomes, respectively, 1 d post-treatment. C — Percentage of positively stained pixels from PBS- and liposome-treated macrophages in the spleen 1 d post-treatment. D, E — Macrophages in the spleens of PBS- or liposome-treated chickens, respectively, 5 d following treatment. F — Percentage of positively stained pixels from PBS- and liposome-treated macrophages in the spleen 5 d post-treatment. G, H — Macrophages in lungs treated with PBS- or clodronate-liposomes, respectively, 1 d post-treatment. I — Percentage of positively stained pixels from PBS- and liposome-treated macrophages in the spleen 1 d post-treatment. J, K — Macrophages in lungs of PBS- or liposome-treated bird, respectively, 5 d following treatment. L — Positively stained pixels from PBS- and liposome-treated macrophages in the spleen 5 d post-treatment. The scale bar in Figures 1A, B, D, E, G, H, J, and K represents 100 μm.

Consistent with data obtained from spleen samples, the clodronate-treated chickens showed a significant reduction (Figure 1I; P = 0.0417) in the number of macrophages in the lungs 1 d post-treatment compared to PBS liposome-treated chickens (Figures 1G, 1H, 1I). Five days post-treatment, the percentage of positively stained macrophages in both treated and control lungs showed no statistically significant difference (Figure 1; P = 0.0713, Figures 1J, 1K, 1L).

Flow cytometry analysis of spleen and lung mononuclear cells

Establishment of flow cytometry technique for the quantification of macrophages from chicken spleen and lung

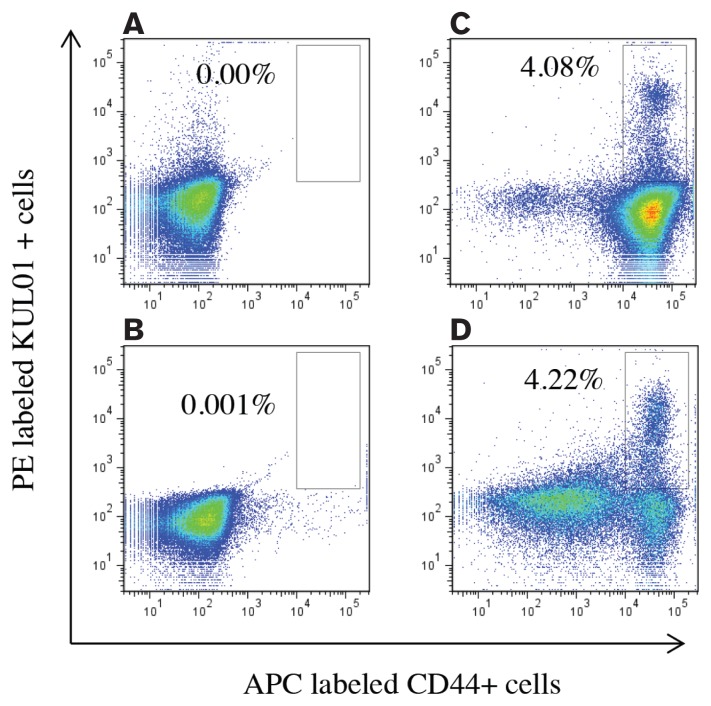

Anti-chicken KUL01 and CD44 antibodies were used to quantify the macrophages in lung and spleen mononuclear cell populations using flow cytometry. The level of non-specific binding of PE-labelled anti-chicken KUL01 (0.00%) and APC-labelled mouse anti-chicken CD44 (0.001%), as assessed against isotype controls, are displayed in Figures 2A and 2B, respectively. Figures 2C and 2D display the specific quantification of macrophage using PE-labelled mouse anti-chicken KUL01 and APC-labelled mouse anti-chicken CD44 antibodies in untreated chickens. Of the mononuclear cells isolated, 4.08% of cells in the spleen (Figure 2C) and 4.22% in the lungs (Figure 2D) were macrophages.

Figure 2.

Flow cytometry analysis for the quantification of macrophages from chicken spleens and lungs. Commercial chickens (n = 2), 28-days-old, were used to isolate mononuclear cells from spleen and lungs and to stain for macrophages (CD44+ KUL01+ cells) using phycoerythrin (PE) labelled mouse anti-chicken KUL01 and allophycocyanin (APC) labelled mouse anti-chicken CD44 monoclonal antibodies for flow cytometry. A, B — Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) plots of isotype control for PE labelled mouse anti-chicken KUL01 antibody and APC labelled mouse anti-chicken CD44 antibody, respectively. C, D — FACS plots showing CD44+ KUL01+ macrophages in spleen and lung respectively.

Flow cytometry analysis of spleen and lung mononuclear cells from chickens that were given single clodronate or PBS liposome treatment demonstrating macrophage depletion 1 d post-treatment, but not 5 d post-treatment

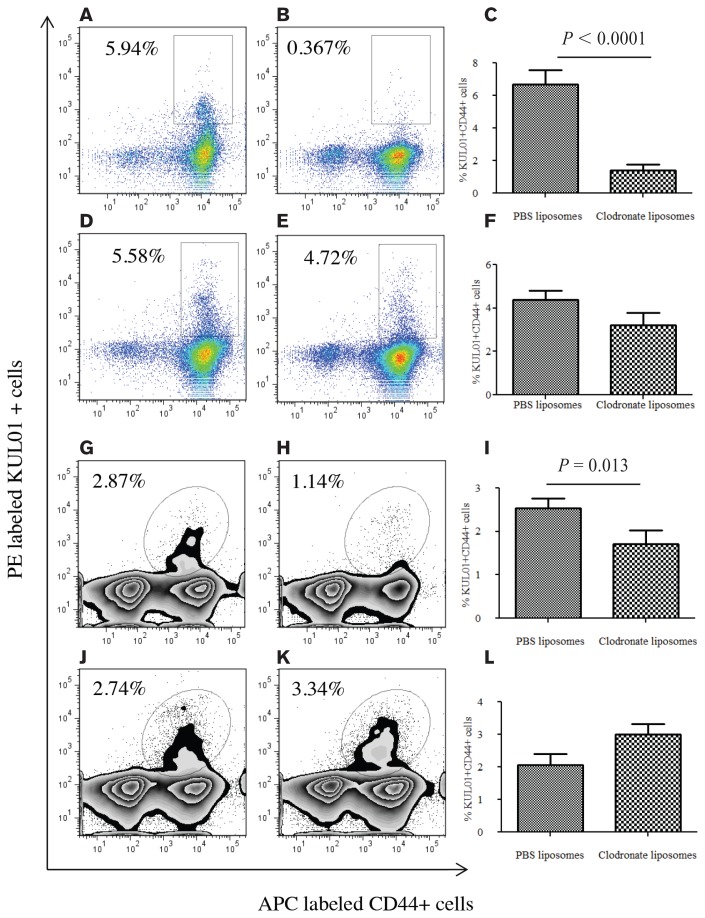

On day 1 post-treatment, clodronate treated-chickens had significantly lower numbers of macrophages (P < 0.0001) compared to the PBS liposome-treated control chickens (Figures 3A, 3B, 3C) in the spleen. To determine the duration of macrophage depletion in chickens, we detected and quantified macrophages on day 5 post-treatment in spleen. In contrast to day 1, we noted that there was no significant difference between treated and control birds on day 5 (P > 0.05; Figures 3D, 3E, 3F).

Figure 3.

Flow cytometry analysis of spleen and lung mononuclear cells from intra-abdominal clodronate and phosphate buffered saline (PBS) treated chickens demonstrating macrophage depletion 1 d post-treatment, but not 5 d post-treatment. A group of commercial chickens, 8- to 12-days-old, were treated intra-abdominally once with 0.5 mL of clodronate liposomes or PBS liposomes. One day or 5 d post-treatment, spleen and lung mononuclear cells were stained and subjected for flow cytometry analysis. A, B — Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) plots showing CD44+ KUL01+ macrophages in the spleens of PBS- or liposome-treated birds, respectively, 1 d following treatment. D, E — FACS plots showing CD44+ KUL01+ macrophages in the spleens of PBS- or liposome-treated birds, respectively, 5 d following treatment. G, H — FACS plots showing CD44+ KUL01+ macrophages in lung of PBS- or liposome-treated birds 1 d following treatment. J, K — Representative FACS plots showing CD44+ KUL01+ macrophages in the lungs of PBS- or liposome-treated birds, respectively, 5 d following treatment. C, F, I, L — Pooled data originated from 2–3 independent experiments. C — Percentage of CD44+ KUL01+ macrophages in the spleens of clodronate liposome-treated (n = 11) or PBS- liposome treated (n = 10) birds 1 d following treatment. F — Percentage of CD44+ KUL01+ macrophages in the spleens of clodronate liposome-treated (n = 8) or PBS liposome-treated (n = 8) birds 5 d following treatment. I — Percentage of CD44+ KUL01+ macrophages in the lungs of clodronate liposome-treated (n = 7) or PBS liposome-treated (n = 7) birds 1 d following treatment. L — Percentage of CD44+ KUL01+ macrophages in the lungs of clodronate liposome-treated (n = 5) or PBS liposome-treated (n = 5) birds 5 d following treatment.

One day post-treatment, clodronate-treated chickens had a significantly lower number of macrophages (P = 0.013) compared to the PBS liposome-treated control chickens (Figures 3G, 3H, 3I) in the lungs. Similar to the spleen, 5 d post-treatment, there was no difference observed in lung macrophages between clodronate-treated and PBS-treated control chickens (P > 0.05, Figures 3J, 3K, 3L).

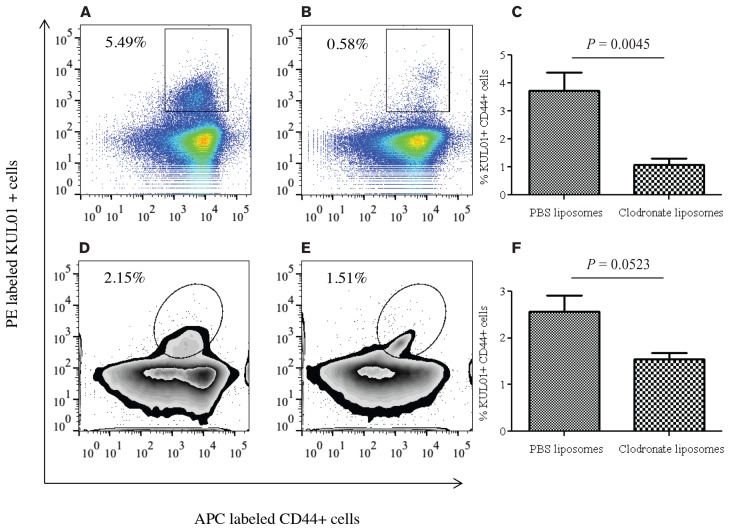

Flow cytometry analysis of spleen and lung mononuclear cells from chickens that were given single clodronate or PBS liposome treatment demonstrating macrophage depletion 4 d posttreatment

Since single treatment of clodronate was not effective in significantly reducing macrophages from the spleen and lungs 5 d post-treatment, we hypothesized that a single treatment of clodronate may be effective in reducing macrophages from the observed tissues 4 d post-treatment, based on our results in a previous experiment (data not shown). In agreement with our hypothesis, clodronate liposome-treated chickens had significantly lower macrophages in spleen compared with the controls (P = 0.0045, Figures 4A, 4B, 4C). Similarly, clodronate liposome-treated chickens had marginally lower macrophages in lungs compared with the controls (P = 0.0523, Figures 4D, 4E, 4F). However, the percentage of macrophage depletion in the spleen was higher than that observed in the lungs.

Figure 4.

Flow cytometry analysis of spleen and lung mononuclear cells from intra-abdominal clodronate and phosphate buffered saline (PBS) treated chickens demonstrating macrophage depletion 4 d post-treatment. Ten commercial chickens, 8- to 12-days old, were treated by intra-abdominal injection once with 0.5 mL of clodronate liposome or PBS liposome. Four days post-treatment, spleen and lung mononuclear cells were isolated and stained. A, B — Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) plots showing CD44+ KUL01+ macrophages in spleen of PBS- or liposome-treated birds, respectively, 4 d following treatment. C — Percentage of CD44+ KUL01+ macrophages in the spleens of clodronate liposome-treated (n = 5) or PBS liposome-treated (n = 5) birds 4 d following treatment. D, E — FACS plots showing CD44+ KUL01+ macrophages in the lungs of PBS- or liposome-treated birds 4 d following treatment. F — Percentage of CD44+ KUL01+ macrophages in the lungs of clodronate liposome-treated (n = 5) or PBS liposome-treated (n = 5) birds 4 d following treatment.

Two clodronate liposome treatments administered 4 d apart are efficacious in depleting avian macrophages from the spleen and lungs longer

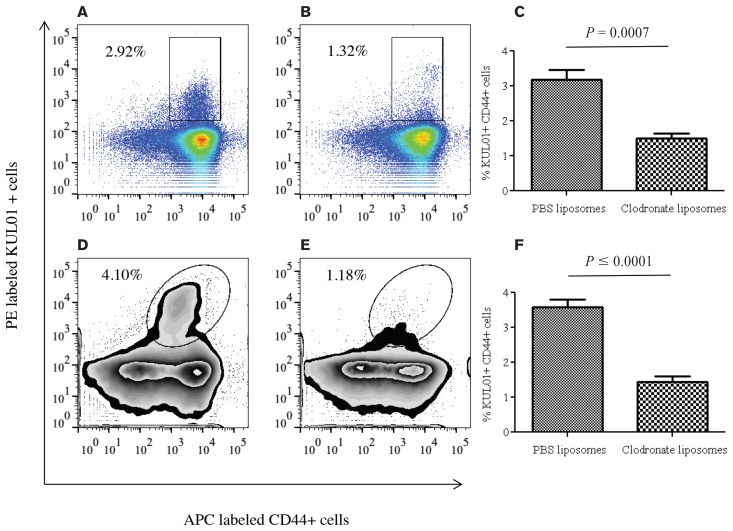

Since a single clodronate liposome treatment reduced macrophages in spleen and lungs 4 d, but not 5 d post-treatment, we then investigated whether 2 clodronate treatments 4 d apart may be effective in significantly depleting macrophages in the spleen and lung for 6 d following the second treatment. As expected, PBS liposome-treated chickens had significantly lower macrophages in the spleen compared with the controls 6 d following the last clodronate treatment (P = 0.0007, Figures 5A, 5B, 5C). Similarly, PBS liposome-treated chickens had significantly lower macrophages in the lungs compared with the controls 6 d following the last clodronate treatment (P ≤ 0.0001, Figures 5D, 5E, 5F).

Figure 5.

Flow cytometry analysis of spleen and lung mononuclear cells from chickens that were given 2 clodronate liposome treatments intra-abdominally, demonstrating macrophage depletion 6 d following the second clodronate treatment. Ten commercial chickens, 11-days-old, were treated by intra-abdominal injection twice 4 d apart with 0.5 mL of clodronate- or PBS-liposomes. Six days following the last treatment, spleen and lung mononuclear cells were isolated and stained. A, B — Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) plots showing CD44+ KUL01+ macrophages in spleen of PBS- or clodronate liposome-treated birds 6 d following treatment. C — Percentage of CD44+ KUL01+ macrophages in the spleens of clodronate liposome-treated (n = 5) or PBS liposome-treated (n = 5) birds 6 d following treatment. D, E — FACS plots showing CD44+ KUL01+ macrophages in the lungs of PBS or clodronate liposome-treated birds 6 d following treatment. F — Percentage of CD44+ KUL01+ macrophages in the lungs of clodronate (n = 5) or PBS liposome-treated (n = 5) birds 6 d following treatment.

Discussion

The phenotypic data demonstrates macrophage depletion, specifically from a secondary lymphoid organ, namely the spleen, and a non-lymphoid organ, the lung, following intra-abdominal administration of clodronate liposomes in chickens. First, in our immunohistochemistry experiments, we used the monoclonal antibody KUL01 (16) to show macrophage depletion following a single clodronate administration in chickens, in a semi-quantitative manner. Secondly, we used a flow cytometry technique to quantify macrophage depletion by way of an anti-CD44 monoclonal antibody combined with antibody KUL01, effectively demonstrating that single clodronate administration in chickens leads to significant macrophage depletion in the lungs and spleen at 1 and 4 d, but not 5 d, post-treatment. Finally, we showed that 2 clodronate treatments administered 4 d apart significantly deplete macrophages from the spleen and lung up to 10 d after the first clodronate treatment.

Treatment of macrophages by clodronate has been done in chickens in a number of earlier studies (11–14). Differences with the earlier studies are previous data having primarily demonstrated an indirect analysis of macrophage depletion following clodronate treatment (11,13,14). For example, some of these experiments focused on either the changes in nitrous oxide (NO) levels in the blood or the progression of various diseases within the organs of the animal as a criterion of macrophage depletion. Nitrous oxide is released by cells in response to viral assault or in the presence of tumors (17), and some experimental procedures showed NO concentration in serum decreasing after the chickens were treated with clodronate within 3 d and returning to normal concentration by 9 d post-treatment (13). A decline in the resistance of chickens to Marek’s disease has also been used as an indicator of macrophage depletion after the administration of clodronate (14). However, these results cannot directly correlate with macrophage depletion with clodronate treatment, since the source of NO can be other cell types such as dendritic cells, natural killer cells, and mast cells (18), and disease progression can be altered by a number of different pathways. Jeurissen and colleagues qualitatively showed histological evidence of macrophage depletion from the spleen of chickens on day 1, 2, and 4 d post-treatment (12). In the later study, the authors observed the effectiveness of macrophage depletion 7 d post-treatment as well and found a lack of depletion of macrophages in the spleen. In addition to providing the quantitative data, we have shown that 2 clodronate treatments can deplete macrophages from the spleen and lung up to 10 d from the first treatment.

Through the use of immunohistochemistry and flow cytometric analyses, we provided more direct evidence of the depletion of macrophages from chicken lungs and spleen. In addition, we provided data on the efficiency of clodronate liposomes in the depletion of macrophages. Also, previous avian studies focused on depleting macrophages via intravenous administration of clodronate with doses ranging from 0.1–0.3 mL (12–14). Since repeated administration of clodronate through an intravenous route in younger birds can sometimes create technical difficulties in terms of administration and dosage amounts, our study focused on administration of clodronate via the more convenient intra-abdominal route using a higher dosage (0.5 mL). Using the intra-abdominal route, we have shown that clodronate can reduce macrophage population significantly in the spleen and lung.

For studies focused on the pathogenesis of infectious diseases, it is necessary to establish long-term macrophage depletion. One important finding in this study was the difference in the number of days clodronate is effective in depleting the macrophages present in the lung parenchyma of chickens compared with other animal models. In the mouse model, long-term macrophage depletion has been achieved through administration of clodronate at weekly intervals (19–22), and the decline in the number of alveolar macrophages was found to remain stable up to 9 d post-treatment in pigs (23). In contrast, our study showed that a single treatment of clodronate decreased macrophage numbers 1 and 4 d post-treatment, but lost its effect by 5 d post-treatment. However, 2 clodronate treatments given 4 d apart were effective in depleting macrophages significantly for 6 d following the last treatment indicating that 2 treatments are sufficient to deplete macrophages up to 10 d.

In conclusion, we have shown that clodronate is an effective drug in depleting macrophages within the lungs and spleen of chickens when used intra-abdominally, but that it must be administered at higher doses and should be applied more frequently than in mammals in order to maintain constant depletion rates. Two clodronate treatments administered 4 d apart would be adequate in reducing macrophages in the spleen and lung at least for 10 d. Through the use of clodronate in chickens, further research could be carried out in determining the importance of macrophages in the avian immune response, which may allow a better understanding of the role of macrophages in the pathogenesis of microbial infections.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, Canadian Poultry Industry Council, Alberta Livestock and Meat Agency, and University of Calgary. Funding agencies were not involved in designing, conducting the experiments, or writing the manuscript. The authors acknowledge the staff, especially Brenda Roszell and Kenwyn White of the Veterinary Science Research Station at Spy Hill, University of Calgary for experimental animal management. The authors thank Chaturika Gunawardana and Hui Xia for optimizing the flow cytometry techniques and University of Calgary Veterinarian, Dr. Greg Muench for his support in the animal procedures.

References

- 1.Maina JN. Some recent advances on the study and understanding of the functional design of the avian lung: Morphological and morphometric perspectives. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 2002;77:97–152. doi: 10.1017/s1464793101005838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reyes JL, Terrazas CA, Alonso-Trujillo J, van Rooijen N, Satoskar AR, Terrazas LI. Early removal of alternatively activated macrophages leads to Taenia crassiceps cysticercosis clearance in vivo. Int J Parasitol. 2010;40:731–742. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2009.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tate MD, Pickett DL, van Rooijen N, Brooks AG, Reading PC. Critical role of airway macrophages in modulating disease severity during influenza virus infection of mice. J Virol. 2010;84:7569–7580. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00291-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roscic-Mrkic B, Schwendener RA, Odermatt B, et al. Roles of macrophages in measles virus infection of genetically modified mice. J Virol. 2001;75:3343–3351. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.7.3343-3351.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mast J, Goddeeris BM. CD57, a marker for B-cell activation and splenic ellipsoid-associated reticular cells of the chicken. Cell Tissue Res. 1998;291:107–115. doi: 10.1007/s004410050984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Culty M, O’Mara TE, Underhill CB, Yeager H, Jr, Swartz RP. Hyaluronan receptor (CD44) expression and function in human peripheral blood monocytes and alveolar macrophages. J Leukoc Biol. 1994;56:605–611. doi: 10.1002/jlb.56.5.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zheng Z, Katoh S, He Q, et al. Monoclonal antibodies to CD44 and their influence on hyaluronan recognition. J Cell Biol. 1995;130:485–495. doi: 10.1083/jcb.130.2.485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Rooijen N, Sanders A. Liposome mediated depletion of macrophages: Mechanism of action, preparation of liposomes and applications. J Immunol Methods. 1994;174:83–93. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(94)90012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Rooijen N, Sanders A. Kupffer cell depletion by liposome-delivered drugs: Comparative activity of intracellular clodronate, propamidine, and ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid. Hepatology. 1996;23:1239–1243. doi: 10.1053/jhep.1996.v23.pm0008621159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fink K, Ng C, Nkenfou C, Vasudevan SG, van Rooijen N, Schul W. Depletion of macrophages in mice results in higher dengue virus titers and highlights the role of macrophages for virus control. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:2809–2821. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hala K, Moore C, Plachy J, Kaspers B, Bock G, Hofmann A. Genes of chicken MHC regulate the adherence activity of blood monocytes in Rous sarcomas progressing and regressing lines. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1998;66:143–157. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2427(98)00191-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jeurissen SH, Janse EM, van Rooijen N, Claassen E. Inadequate anti-polysaccharide antibody responses in the chicken. Immunobiology. 1998;198:385–395. doi: 10.1016/S0171-2985(98)80047-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quere P, Rivas C, van Rooijen N. Use of dichloromethylene bisphosphonate (Cl2MBP) to deplete macrophage function in the chicken. Br Poult Sci. 2003;44:828–830. doi: 10.1080/00071660410001667087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rivas C, Djeraba A, Musset E, van Rooijen N, Baaten B, Quere P. Intravenous treatment with liposome-encapsulated dichloromethylene bisphosphonate (Cl2MBP) suppresses nitric oxide production and reduces genetic resistance to Marek’s disease. Avian Pathol. 2003;32:139–149. doi: 10.1080/030794502100007163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.CCAC Guide to Care and Use of Experimental Animals. 2nd ed. Ottawa, Ontario: Canadian Council on Animal Care; 1993. pp. 1–298. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mast J, Goddeeris BM, Peeters K, Vandesande F, Berghman LR. Characterisation of chicken monocytes, macrophages and interdigitating cells by the monoclonal antibody KUL01. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1998;61:343–357. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2427(97)00152-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reiss CS, Komatsu T. Does nitric oxide play a critical role in viral infections? J Virol. 1998;72:4547–4551. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.6.4547-4551.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bogdan C. Nitric oxide and the immune response. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:907–916. doi: 10.1038/ni1001-907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abdul-Careem MF, Firoz Mian M, Gillgrass AE, et al. FimH, a TLR4 ligand, induces innate antiviral responses in the lung leading to protection against lethal influenza infection in mice. Antiviral Res. 2011;92:346–355. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2011.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lang PA, Recher M, Honke N, et al. Tissue macrophages suppress viral replication and prevent severe immunopathology in an interferon-I-dependent manner in mice. Hepatology. 2010;52:25–32. doi: 10.1002/hep.23640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tumpey TM, Garcia-Sastre A, Taubenberger JK, et al. Pathogenicity of influenza viruses with genes from the 1918 pandemic virus: Functional roles of alveolar macrophages and neutrophils in limiting virus replication and mortality in mice. J Virol. 2005;79:14933–14944. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.23.14933-14944.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Traeger T, Kessler W, Hilpert A, et al. Selective depletion of alveolar macrophages in polymicrobial sepsis increases lung injury, bacterial load and mortality but does not affect cytokine release. Respiration. 2009;77:203–213. doi: 10.1159/000160953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim HM, Lee YW, Lee KJ, et al. Alveolar macrophages are indispensable for controlling influenza viruses in lungs of pigs. J Virol. 2008;82:4265–4274. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02602-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]