Abstract

Context

Lower IQ individuals have an increased risk of psychological disorders, mental health problems, and suicide; similarly, children with low IQ scores are more likely to have behavioural, emotional and anxiety disorders. However, very little is known about the impact of parental IQ on the mental health outcomes of their children.

Objective

To determine whether maternal and paternal IQ score is associated with offspring conduct, emotional and attention scores.

Design

Cohort.

Setting

General population.

Participants

Members of 1958 National Child Development Study and their offspring. Of 2,984 parent-offspring pairs, with non-adopted children aged 4+ years, 2,202 pairs had complete data on all variables of interest and were included in the analyses.

Outcome measure

Offspring conduct, emotional and attention scores based on Behavioural Problems Index for children aged 4-6 years or the Rutter A scale for children aged 7 and over.

Results

There was little evidence of any association of parental IQ with conduct or emotional problems in younger (aged 4-6) children. However, among children aged 7+, there was strong evidence from age- and sex-adjusted models to support a decrease in conduct, emotional and attention problems in those whose parents had higher IQ scores. These associations were linear across the full IQ range. Individual adjustments for socioeconomic status and child’s own IQ had limited impact while adjustments for Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment (HOME) scores and parental malaise attenuated associations with mother’s IQ but, again, had little impact on associations with father’s IQ. Strong associations were no longer evident in models that simultaneously adjusted for all four potential mediating variables.

Conclusions

Children whose parents score poorly on IQ tests may have an increased risk of conduct, emotional and attention problems. Home environment, parental malaise, and child’s own IQ may have a role in explaining these associations.

Introduction

Emerging evidence suggests that individuals who score poorly on IQ tests in childhood, adolescence or early adulthood are more likely as adults to experience psychological distress,1 are at increased risk of the whole range of mental disorders,2-3 and have higher rates of attempted4-5 and completed6-7 suicide. Lower IQ in children has also been associated with an increased risk of behavioural and emotional problems,8 and anxiety disorders.8-9 However, the extent to which these mental health outcomes are also influenced by parental IQ remains unknown.

A very sparse literature suggests that maternal10-11 or mean parental12 IQ may be associated with behavioural and emotional problems in their offspring. However, the overall evidence is inconsistent and mainly relies on small-scale studies that are based on non-representative groups and tend to focus specifically on children whose parents have below average IQ. Chen et al10, for example, used follow-up data from a trial of 656 children with high blood lead levels and found an increase in behavioural problems in those whose mothers had lower IQ scores. However, this association was attenuated after controlling for child’s own IQ. In a study of 121 adolescent mothers characterised by below average intelligence,11 maternal IQ was negatively correlated with children’s socio-emotional development scores. This association was not robust to adjustment for factors such as cognitive readiness for parenting and social support, although it is of note that both of these factors were correlated with maternal IQ and their inclusion might therefore have led to over-adjustment. Goodman et al12 targeted a sample of 411 twins and found that, after adjustment for socioeconomic status (SES) and own IQ, children whose parents’ had a higher average IQ had more emotional symptoms. Finally, results from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth,13 which includes 2,256 children aged 4 to 11, did not show any impact of maternal IQ on offspring behavioural scores in multivariable models that also included a number of factors such as family income, maternal smoking and maternal education. However, children whose parents provided less cognitive stimulation and emotional support, as measured by poorer scores on the Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment (HOME) Inventory, had more behavioural problems.

In this report from the 1958 National Child Development Study, we examine associations of parental IQ with offspring conduct, emotional and attention problem scores. Our analyses are based on data drawn from a large, British, representative cohort of parent-offspring pairs with IQ measurements in childhood available for both offspring and parents and with participants from across the full IQ range. A major advantage of this study is the availability of both maternal and paternal IQ test scores, which allows a comparison of the strength of association of each with offspring development and behaviours. Similar magnitudes of effect for maternal and paternal IQ would suggest that associations are generated by factors that are as likely to be transmitted from father to offspring as they are from mother to offspring; these might include e.g. nuclear genetic variation, socioeconomic position, or shared lifestyle factors. In contrast, a stronger maternal IQ association might suggest that maternal or intrauterine characteristics are more important in determining children’s development and behaviour. In addition, data are available on a number of potential mediating factors, which allows exploration of the possible mechanisms underlying any associations between parental IQ and offspring conduct, emotional and attention problem scores. These mediating variables include SES, child’s own IQ, quality and quantity of cognitive stimulation and emotional support, as measured by HOME scores, and parental malaise.

Methods

Study population

The National Child Development Study (1958 cohort) comprises over 17,000 live births in Great Britain occurring between 3rd and 9th March 1958.14 Follow-up sweeps were carried out in 1965, 1969, 1974, 1991 and 1999-2000. The 1991 follow-up collected data on the original cohort, then aged 33, and also from the offspring of one in three randomly selected cohort members. In the present analysis, parental data were obtained from the original study members of the 1958 cohort and offspring data from their children.

Parental data collection

The cohort member’s mental ability was assessed at school in 1969, at age 11, using a general ability test devised by the National Foundation for Educational Research in England and Wales.15 Scores from this test correlate strongly with verbal ability test scores used to select 11-year-olds for secondary school,15 suggesting a high degree of validity. Data on marital status and SES were collected 22 years later, in 1991; SES was based on own occupation for male cohort members and husband’s occupation for female cohort members. Psychological distress and depression in 1991 was measured using the Malaise Inventory.16

Offspring data collection

Offspring cognitive ability-related tests, performed in 1991, were administered by interviewers and included the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (PPVT), the McCarthy Scale of Child Abilities (verbal subscale) and the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (digit span subscale). PPVT scores were measured in all children aged 4+ and we present results based on these data. However, results based on other IQ measures, which were available for a smaller subgroup of children, are broadly similar (results not shown). PPVT is a widely used and recognised indicator of children’s cognitive function and has been shown to correlate well with IQ-type measures.17

The quality and quantity of cognitive stimulation and emotional support provided to children in the home was assessed using HOME scores,18 based on responses from mothers, regardless of the sex of the original cohort member. Similarly, conduct, emotional and attention difficulties were assessed using mothers’ responses to the Behavioural Problems Index19 for children aged 4 to 6 years or the Rutter A scale16 for children aged 7 and over. These scales have been widely used and validated.19-20 The Behavioural Problems Index consists of 32 items with 3 response options (often true, sometimes true, not true). We subjected the mothers’ responses to these 32 items to principal components analysis. The scree slope suggested the presence of two factors after oblique rotation (direct oblimin), which accounted for 23.2% of the total variance. High loading items (>0.50) were retained and the two extracted factors were labeled ‘Conduct problems and ‘Emotional problems’. Cronbach alpha for these scales were 0.84 and 0.75 respectively. The Rutter A scale consisted of 18 items with 3 response options (certainly applies, applies somewhat, does not apply). The scree slope from a principal components analysis of these items suggested the presence of three factors after oblique rotation (direct oblimin), which accounted for 24.3% of the total variance. High loading items (>0.50) were retained and the three extracted factors were labeled ‘Conduct problems, ‘Emotional problems’ and ‘Attention problems’. Cronbach alpha for these were 0.78, 0.60 and 0.80 respectively.

Data analysis

Parental IQ associations with offspring behavioural scores were based on cohort member-offspring pairs where the offspring was non-adopted and aged 4 to 18 years at the time of data collection. Analyses were carried out using least squares regression and associations are presented as mean change in outcome per standard deviation (SD) increase in parental IQ, having first checked that the associations were approximately linear. We performed separate analyses based on maternal vs. paternal IQ to allow for differential effects and carried out corresponding statistical tests for interaction/effect modification. 95% confidence intervals (CI) are based on robust standard errors which take account of the non-independence of children from the same family.

All analyses were adjusted for the potential confounding effects of offspring age and sex. There is evidence to suggest that lower IQ women are more likely to have their children at younger ages21 and it is therefore important to consider the role of parental age at the time of offspring birth in explaining any parental IQ associations. However, the parents in the current analysis were all born in the same week and data on their offspring were collected over a very short period of time in 1991, so adjustment for offspring age in this case is equivalent to adjustment for parental age at offspring birth; we have confirmed that additional adjustment for parental age has no impact on the results presented here (results not shown). Adjustment for marital status had no impact on the results as 99% of men and women stated that they were married in 1991 (results not shown).

Possible mechanisms underlying parental IQ-offspring behaviour associations were explored in more detail using models with additional adjustments for the mediating effect of parental SES and offspring IQ, both of which are likely to depend on parental IQ, and which might be expected to be associated with children’s psychological well-being. Separate adjustments were also similarly made for HOME scores, which have previously been associated with both maternal IQ22-24 and offspring behaviour,13 and for parental depression, which is known to be associated with IQ1-2 and with offspring psychological development.25-27 For information, we also present models that adjust for all four potential mediating factors simultaneously. As we show in the results, these factors are associated with parental IQ and offspring psychological development and also with each other. For example, offspring IQ depends on parental IQ; however, it may also be influenced by home environment (HOME score) which, in turn, may be affected by parental malaise. A model which includes all factors simultaneously may therefore be over-adjusted and should be interpreted with caution. Analyses are based on parent-offspring pairs with complete data on all variables of interest.

Results

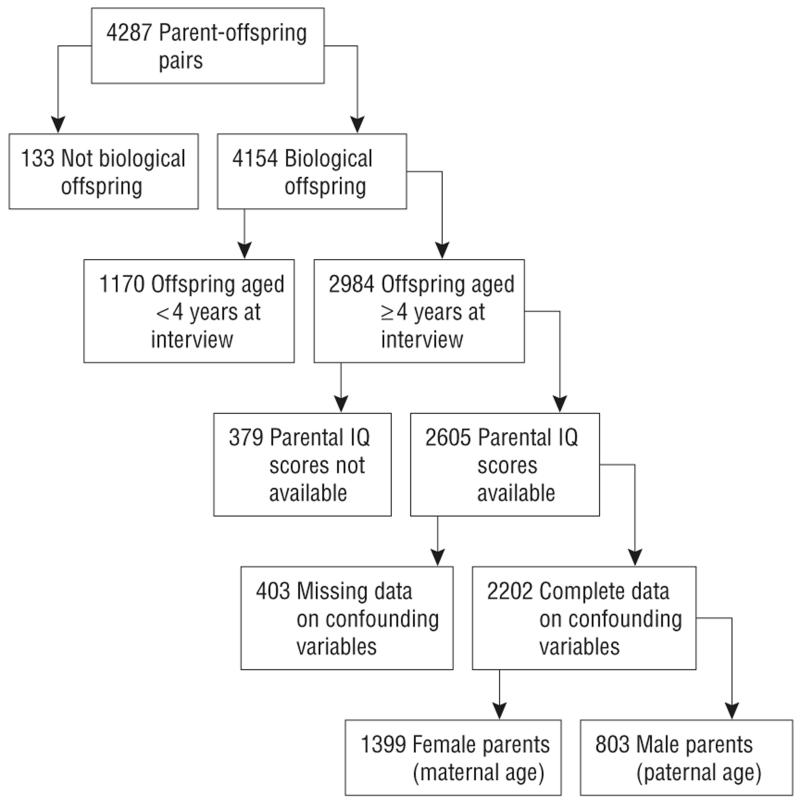

The original sample consisted of 4,287 parent-offspring pairs (Figure 1) and the offspring of 2,984 (69.6%) were known to be non-adopted and aged 4+ years in 1991(when offspring IQ measurements were made). Parental IQ was unavailable for 379 (12.7%) of these pairs and there were missing data on confounding variables for a further 403 (13.5%), leaving an analytical sample of 2,202 pairs. The characteristics of parents and offspring excluded from the analyses as a result of missing data were similar although parental IQ, where available, was somewhat lower (mean (SD) parental IQ in those with missing vs. complete confounding data: 38.4 (15.5) vs. 42.8 (15.4)). Parental IQ and SES were higher in parent-offspring pairs who were excluded because the child was aged <4 years in 1991, which would be consistent with higher IQ cohort members choosing to have their children at later ages.

Figure 1. Selection of analytical sample.

The analytical sample included a total of 1,399 (63.5%) mother-offspring and 803 (36.5%) father-offspring pairs and their characteristics are shown in Table 1. Just under half of offspring were male and this proportion, along with average offspring IQ, was very similar in mother- vs. father-offspring pairs. Almost two thirds of cohort members were from SES III (lowest category), although fathers were slightly more likely to be from SES I or II, in spite of a slightly lower average IQ at age 11. The main difference between mother- and father-offspring pairs was the average offspring age in 1991 which was 1.3 years lower in father-offspring pairs, suggesting that men tended to be slightly older than women when their children were born.

Table 1. Characteristics of 2,202 parent-offspring pairs.

| Mother-offspring pairs (N=1,399) |

Father-offspring pairs (N=803) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Parental IQ (NEFR) score at age 11 (Mean (SD)) | 43.6 (15.5) | 42.0 (15.3) |

| Socioeconomic status (N (%)) | ||

| I | 42 ( 3.0) | 32 ( 4.0) |

| II | 102 ( 7.3) | 98 (12.2) |

| III | 919 (65.7) | 481 (59.9) |

| IV | 191 (13.7) | 105 (13.1) |

| V | 145 (10.4) | 87 (10.8) |

| Parental malaise score in 1991 (Mean (SD)) | 3.1 (3.5) | 2.0 (2.8) |

| HOME score in 1991 (Mean(SD)) | 22.0 (3.7) | 22.5 (3.3) |

| Offspring sex (N (%)) | ||

| Male | 691 (49.4) | 390 (48.6) |

| Female | 708 (50.6) | 413 (51.4) |

| Offspring age in 1991 (Mean (SD)) | 8.6 (3.2) | 7.3 (2.6) |

| Offspring IQ (PPVT) score in 1991 (Mean (SD)) | 34.4 (11.1) | 33.8 (10.6) |

Correlations between parental IQ scores and malaise, HOME, and offspring IQ are shown in Table 2. Offspring IQ and HOME scores were both strongly positively correlated with maternal and paternal IQ. Malaise scores were negatively correlated with parental IQ, most markedly in mothers, indicating that parents with higher IQ scores were less likely to be depressed. Pairwise correlations between SES, offspring IQ, HOME, and malaise scores were modest in magnitude but statistically significant (p<0.001 for all correlations), with coefficients ranging from −0.10 (offspring IQ-parental malaise) to 0.22 (offspring IQ-HOME score).

Table 2. Correlations of parental IQ score with parental malaise, HOME, and offspring IQ scores.

| Maternal IQ score | Paternal IQ score | |

|---|---|---|

| Offspring IQ score | 0.30 | 0.31 |

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| HOME score | 0.28 | 0.24 |

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Parental malaise score | −0.24 | −0.17 |

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Associations of parental IQ with behavioural problem scores are presented in Tables 3a (mothers) and 3b (fathers). Approximately one third of children were aged 4 to 6 years at data collection. Among this group there were no marked associations between conduct problem scores and either maternal or paternal IQ. In adjusted models, there was a suggestion that children with higher IQ fathers and, to a lesser extent, higher IQ mothers might have slightly higher scores for emotional problems but this association was only of borderline statistical significance.

Table 3a. Association (regression coefficient (95% confidence interval)) of mother’s IQ at age 11 with offspring conduct, emotional and attention problem scores at age 4+ years.

| Adjustments | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N / Mean (SD) | Offspring age and sex | Offspring age, sex and SES | Offspring age, sex and IQ | Offspring age, sex and HOME score | Offspring age, sex and parental malaise | Multiple1 | |

| Children aged 4 to 6 2 | |||||||

| Conduct problems score | |||||||

| SD increase3 | 420 / 22.8 (5.1) | −0.33 (−0.91, 0.25) | −0.33 (−0.93, 0.28) | −0.20 (−0.79, 0.40) | 0.04 (−0.55, 0.63) | −0.14 (−0.66, 0.37) | 0.17 (−0.40, 0.74) |

| P 4 | 0.26 | 0.29 | 0.52 | 0.89 | 0.58 | 0.55 | |

| Emotional problems score | |||||||

| SD increase3 | 422 / 15.9 (3.3) | 0.05 (−0.31, 0.41) | 0.08 (−0.30, 0.45) | 0.04 (−0.32, 0.40) | 0.21 (−0.15, 0.57) | 0.13 (−0.21, 0.47) | 0.23 (−0.13, 0.59) |

| P 4 | 0.79 | 0.69 | 0.83 | 0.25 | 0.46 | 0.22 | |

|

| |||||||

| Children aged 7+ 5 | |||||||

| Conduct problems score | |||||||

| SD increase3 | 833 / 9.4 (2.3) | −0.49 (−0.73, −0.25) | −0.53 (−0.78, −0.28) | −0.44 (−0.69, −0.19) | −0.33 (−0.57, −0.09) | −0.31 (−0.54, −0.09) | −0.22 (−0.45, 0.02) |

| P 4 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.07 | |

| Emotional problems score | |||||||

| SD increase3 | 831 / 7.5 (1.9) | −0.16 (−0.31, −0.02) | −0.19 (−0.34, −0.03) | −0.17 (−0.32, −0.02) | −0.11 (−0.27, 0.04) | −0.03 (−0.17, 0.11) | −0.05 (−0.21, 0.11) |

| P 4 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.15 | 0.66 | 0.56 | |

| Attention problems score | |||||||

| SD increase3 | 835 / 4.3 (1.6) | −0.25 (−0.36, −0.13) | −0.24 (−0.36, −0.11) | −0.22 (−0.34, −0.09) | −0.18 (−0.30, −0.05) | −0.14 (−0.26, −0.02) | −0.08 (−0.21, 0.06) |

| P 4 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.27 | |

Adjusted for offspring age, sex, IQ, HOME score, SES, and parental malaise;

Based on Behaviour Problems Index;

Mean change per SD increase;

P for linear trend;

Based on Rutter A scale

Table 3b. Association (regression coefficient (95% confidence interval)) of father’s IQ at age 11 with offspring conduct, emotional and attention problem scores at age 4+ years.

| Adjustments | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N / Mean (SD) | Offspring age and sex | Offspring age, sex and SES | Offspring age, sex and IQ | Offspring age, sex and HOME score | Offspring age, sex and parental malaise | Multiple1 | |

| Children aged 4 to 6 2 | |||||||

| Conduct problems score | |||||||

| SD increase3 | 313 / 22.9 (5.2) | −0.36 (−1.05, 0.32) | −0.30 (−1.00, 0.40) | −0.29 (−0.98, 0.40) | −0.03 (−0.68, 0.62) | −0.22 (−0.91, 0.48) | 0.05 (−0.62, 0.72) |

| P 4 | 0.29 | 0.40 | 0.41 | 0.92 | 0.54 | 0.88 | |

| Emotional problems score | |||||||

| SD increase3 | 320 / 15.5 (2.7) | 0.33 (−0.07, 0.73) | 0.42 (−0.01, 0.84) | 0.30 (−0.09, 0.69) | 0.42 (0.01, 0.83) | 0.38 (−0.02, 0.79) | 0.47 (0.05, 0.88) |

| P 4 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.13 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.03 | |

|

| |||||||

| Children aged 7+ 5 | |||||||

| Conduct problems score | |||||||

| SD increase3 | 388 / 9.4 (2.3) | −0.29 (−0.56, −0.01) | −0.23 (−0.51, 0.05) | −0.22 (−0.50, 0.06) | −0.20 (−0.47, 0.07) | −0.29 (−0.57, −0.01) | −0.12 (−0.42, 0.17) |

| P 4 | 0.04 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.05 | 0.41 | |

| Emotional problems score | |||||||

| SD increase3 | 387 / 7.4 (1.9) | −0.09 (−0.28, 0.11) | −0.08 (−0.27, 0.12) | −0.11 (−0.32, 0.10) | −0.07 (−0.28, 0.13) | −0.06 (−0.26, 0.14) | −0.06 (−0.28, 0.16) |

| P 4 | 0.38 | 0.45 | 0.31 | 0.46 | 0.58 | 0.58 | |

| Attention problems score | |||||||

| SD increase3 | 393 / 4.3 (1.7) | −0.26 (−0.42, −0.10) | −0.25 (−0.41, −0.08) | −0.21 (−0.38, −0.04) | −0.22 (−0.39, −0.06) | −0.25 (−0.41, −0.09) | −0.16 (−0.35, 0.02) |

| P 4 | 0.001 | 0.004 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.002 | 0.09 | |

Adjusted for offspring age, sex, IQ, HOME score, SES, and parental malaise;

Based on Behaviour Problems Index;

Mean change per SD increase;

P for linear trend;

Based on Rutter A scale

Age- and sex-adjusted maternal IQ associations for offspring aged 7+ (Table 3a) indicated that children whose mothers had higher IQ at age 11 tended to have lower scores for conduct problems, emotional problems and attention problems. These associations were only marginally affected by adjustments for SES and child’s own IQ. Individual adjustments for HOME score and, in particular, mother’s malaise score led to a more marked attenuation of associations; however, 95% confidence intervals for those with conduct and attention problems remained below 0. Associations adjusted for all four factors simultaneously were no longer statistically significant at conventional levels. Paternal IQ associations (Table 3b) were based on smaller numbers of parent-offspring pairs but were similar to those for maternal IQ, with the children of higher IQ fathers having lower conduct, emotional and attention scores, although associations with emotional scores were not conventionally statistically significant. Again, these associations were largely unaffected by individual adjustment for SES and offspring IQ. However, in contrast to maternal IQ associations, individual adjustment for HOME scores and paternal malaise also had little or no impact on these results. Again, multiply adjusted models were not conventionally statistically significant.

The marked attenuation of associations in multiply adjusted models is consistent with a mediating role of at least one of SES, offspring IQ, HOME score, or parental malaise. However, results from individually adjusted models suggest that these mediating effects were modest and there was no evidence that any single factor explained the associations between parental IQ and offspring conduct, emotional and attention scores.

Discussion

We have explored associations between parental IQ and offspring conduct, emotional and attention problems. There was no evidence to suggest that parental IQ had an impact on the conduct problems of children aged 4-6 and an unexpected weak suggestion of an increase in emotional problems in younger children whose fathers, in particular, had a higher IQ score. Conversely, among children aged 7+, age- and sex-adjusted analyses indicated that those with higher IQ parents had fewer conduct, emotional and attention problems. These associations were attenuated to some extent by individual adjustments for SES, child’s own IQ and, in the case of mothers, particularly HOME scores and malaise; simultaneous adjustment for all four factors markedly attenuated associations.

The current analyses have a number of advantages over previous studies. In addition to the relatively large sample size, the original cohort from which our sample was drawn is representative of all men and women born in Britain at around this time and, most importantly, includes those with IQ scores from across the full “normal” range in both mothers and fathers. Parental IQ was measured in childhood, before any substantial impact of education on IQ test performance and we also had data on potential mediating factors such as SES, offspring IQ, HOME scores, and parental malaise, which has allowed a more detailed exploration of the possible mechanisms underlying parental IQ-offspring behaviour associations. The Behavioural Problems Index and Rutter scores used to measure children’s conduct, emotional and attention problems are well validated and widely used. In addition, this analysis is, as far as we are aware, unique in using IQ data from both mothers and fathers.

However, there are also a number of limitations. Although all cohort members were included in the main study follow up, only a third of cohort members with children were invited to take part in the parts of the survey that involved the children. Cohort members excluded from our analyses tended to have somewhat higher SES, although it is reassuring that their mean IQ was almost identical to those included in the analyses. Also, although we adjusted for age and sex and also looked at the additional impact of adjustments for potential mediating factors such as SES, offspring IQ, HOME scores and parental malaise, we cannot rule out residual confounding by other unmeasured confounding/mediating factors. Conversely it is important to recognise that the four mediating factors were all highly correlated with parental IQ and with each other, and that models that contain all four simultaneously (multiply adjusted models presented in Tables 3a and b) may therefore be over-adjusted. In addition, although it is informative to consider the degree of attenuation due to statistical adjustment for these factors, we cannot draw any conclusions regarding direct causality. Finally, the possibility of biases cannot be ruled out. Children with behavioural problems may have performed particularly poorly in IQ tests which could potentially inflate the confounding effects of offspring IQ. In addition, all of our outcome measures were based on maternal responses rather than direct observation of the children and may therefore be subject to reporting biases if mothers with higher or lower IQ were more likely to perceive or report problems with their children’s behaviour.

Parental IQ generally had little impact on the conduct scores of younger (aged 4-6) offspring in these data, although it is worth noting that analyses were based on smaller numbers than those for older (aged 7+) children and that psychological assessments in this younger group are likely to have been less reliable. The isolated finding of increased emotional problems in younger children with higher IQ parents, particularly fathers, is consistent with a previous finding by Goodman et al,12 who reported an increased risk of behavioural problems in children whose parents had a higher mean IQ. These authors suggested a number of mechanisms for this association including higher academic expectations and pressures applied by higher IQ parents, or a style of parenting that is more over-protective or more sensitive to the child. While plausible, it is difficult to explain why these factors would apply more to fathers in the present analyses and, although associations in offspring aged 7+ were weakest for the emotional dimension of the Rutter scores, they were nonetheless consistent with a decrease in problems in children of higher IQ parents. It may therefore be the case that this result is simply a chance finding as a result of multiple comparisons.

In contrast, age- and sex-adjusted associations in older (7+) offspring were consistent with decreasing problems in children whose parents had higher IQ scores. Although there is a literature regarding the delayed development and worse behaviour of children born to mothers with specific intellectual disabilities,28-30 or below average IQ scores,10-11 very little is known about the impact of parental IQ in the normal range on child behaviour problems. The associations among older children in the current analyses were linear across all parental IQ scores, suggesting that it is not parents’ intellectual disability per se that is associated with behavioural difficulties, but rather that there is a gradient of effect across the full “normal” IQ range. In order to explore the possible mechanisms underlying these associations, we examined the impact of adjusting for a number of potential mediators, namely SES, child’s own IQ, HOME scores, and parental malaise. The strong associations observed in age- and sex-adjusted models were no longer apparent in multiply adjusted models, suggesting that at least some of these factors had a mediating effect. However, results from analyses that adjusted for each factor individually showed only a modest degree of attenuation, if any, so that, although they each appeared to play some part, no single factor completely explained parental IQ-childhood behaviour associations.

It is not surprising that adjustment for child’s own IQ attenuated some of these associations but what is of note is that the degree of attenuation was relatively small and, in some cases, nonexistent, indicating that parental IQ may have an independent impact on these outcomes beyond that conferred by inherited intellectual ability. Similarly, adjustment for SES had very little impact on our results, suggesting that the potential material aspects of low parental IQ, such as unemployment, low household income, or living in a deprived area, did not play a substantial role in explaining these associations.

Previous studies suggest that lower IQ parents may provide a less stimulating or supportive home environment22-24 and that this may impact negatively on their children’s IQ31-32 and behaviour.13 HOME scores in the current cohort were positively correlated with parental IQ and adjustments for HOME scores generally attenuated parental IQ-offspring behaviour associations, particularly those with mother’s IQ. Although adjustment for HOME scores did not completely explain these associations, the attenuation indicates that parenting quality and style may have a mediating role in explaining parental IQ-offspring behaviour associations, i.e. parents with lower IQ scores may provide less cognitive stimulation and emotional support and this may result in an increase in behavioural problems.

Similarly, lower IQ is known to be associated with an increased risk of depression both in this1 and other2 populations. Adjustment for paternal malaise left associations of father’s IQ with offspring behaviour almost unchanged. Conversely, adjustment for maternal malaise had the greatest impact of any variable on associations with mother’s IQ. There is evidence that parental psychiatric disorders are associated with behavioural problems in children,25-27 and the results from the current analyses would support a mediating role of depression in explaining mother’s IQ-offspring behaviour associations. However, it is also worth considering previous evidence which indicates that the presence of depression may influence how mothers rate childhood behaviour,33 with depressed mothers tending to over-report child behaviour problems. In this context it is of note that the attenuating influence of parental malaise in the current analyses was restricted to mothers and that, regardless of the sex of the original cohort member, it was the mother who provided responses to the behavioural questions regarding their children.

We are not aware of any previous studies that have looked directly at associations with maternal vs. paternal IQ. In the current analyses, associations based on mother- and father-offspring pairs were similar which is, perhaps, not surprising given that couples are likely to have similar IQ scores. What is of interest, is the relative impact of adjustments for mediating factors in mothers and fathers. While the effects of adjustment for SES and offspring IQ were similar for both groups of parents, the impact of adjustment for HOME scores and, in particular, malaise, was much greater in maternal IQ associations with offspring behaviour. It is possible that this greater impact is simply a result of mothers providing offspring behavioural data. However, it may also reflect the more influential parenting role amongst mothers, who are more commonly the primary care-giver.

The aetiology of child behavioural problems is complex with many interrelated factors playing an important role. Our results suggest that the children of lower IQ parents may be at high-risk of conduct, emotional and attention problems and that this may be a result, at least partially, of lower IQ in the child, a poorer home environment, and greater malaise in the parents. Further studies are needed to explore these mechanisms in more detail and to determine whether families of this type might benefit from additional or targeted education and support.

Acknowledgments

Funding: DB is a Wellcome Trust Fellow, funding from which also supports EW. The Medical Research Council (MRC) Social and Public Health Sciences Unit receives funding from the UK Medical Research Council and the Chief Scientist Office at the Scottish Government Health Directorates. The Centre for Cognitive Ageing and Cognitive Epidemiology is supported by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, the Economic and Social Research Council, the MRC, and the University of Edinburgh as part of the cross-council Lifelong Health and Wellbeing initiative. MK is supported by the Academy of Finland, the BUPA Foundation, UK, and the NIH/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01HL036310-20A2) and the National Institute on Aging (R01AG034454), US.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None

References

- 1.Gale CR, Hatch SL, Batty GD, Deary IJ. Intelligence in childhood and risk of psychological distress in adulthood: The 1958 National Child Development Survey and the 1970 British Cohort Study. Intelligence. 2009;37(6):592–599. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gale CR, Deary IJ, Boyle SH, Barefoot J, Mortensen LH, Batty GD. Cognitive ability in early adulthood and risk of 5 specific psychiatric disorders in middle age: the Vietnam Experience Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:1410–1418. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.12.1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gale C, Batty G, Tynelius P, Deary I, Rasmussen F. Intelligence in Early Adulthood and Subsequent Hospitalization for Mental Disorders. Epidemiology. 2010;21:70–77. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181c17da8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Batty GD, Whitley E, Deary IJ, Gale CR, Tynelius P, Rasmussen F. Psychosis alters association between IQ and future risk of attempted suicide: cohort study of 1 109 475 Swedish men. BMJ. 340 doi: 10.1136/bmj.c2506. Article No: c2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Osler M, Nybo Andersen AM, Nordentoft M. Impaired childhood development and suicidal behaviour in a cohort of Danish men born in 1953. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62:23–28. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.053330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gunnell D, Magnusson PKE, Rasmussen F. Low intelligence test scores in 18 year old men and risk of suicide: cohort study. BMJ. 2004;330:167–170. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38310.473565.8F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andersson L, Allebeck P, Gustafsson JE, Gunnell D. Association of IQ scores and school achievement with suicide in a 40-year follow-up of a Swedish cohort. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2008;118:99–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Ridder EM. Show me the child at seven II: childhood intelligence and later outcomes in adolescence and young adulthood. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2005;46:850–858. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin LT, Kubzansky LD, LeWinn KZ, Lipsitt LP, Satz P, Buka SL. Childhood cognitive performance and risk of generalized anxiety disorder. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36(4):769–775. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen A, Schwarz D, Radcliffe J, Rogan WJ. Maternal IQ, child IQ, behavior, and achievement in urban 5-7 year olds. Pediatr Res. 2006;59(3):471–477. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000199910.16681.f0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sommer KS, Whitman TL, Borkowski JG, Gondoli DM, Burke J, Maxwell SE, Weed K. Prenatal maternal predictors of cognitive and emotional delays in children of adolescent mothers. Adolescence. 2000;35(137):87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goodman R, Simonoff E, Stevenson J. The impact of child IQ, parent IQ and sibling IQ on child behavioural deviance scores. J Child Psychol Psychiat. 1995;36(3):409–425. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1995.tb01299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weitzman M, Gortmaker S, Sobol A. Maternal Smoking and Behavior Problems of Children. Pediatrics. 1992;90(3):342–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Power C, Elliott J. Cohort profile: 1958 British birth cohort (National Child Development Study) Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35:34–41. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Douglas J. The home and the school: a study of ability and attainment in primary school. MacGibbon and Kee; London: 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rutter M, Tizard J, Whitmore K. Education, health and behaviour. Longman; London: 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dunn L, Dunn L. Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-Revised. American Guidance Service; Circle Pines, MN: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bradley RH, Caldwell BM, Rock SL, Hamrick HM, Harris P. Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment - Development of a Home Inventory for Use with Families Having Children 6 to 10 Years Old. Contemp Educ Psychol. 1988;13(1):58–71. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Graham P, Rutter M. The Reliability and Validity of the Psychiatric Assessment of the Child: II. Interview with the Parent. Br J Psychiatry. 1968;114(510):581–592. doi: 10.1192/bjp.114.510.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kresanov K, Tuominen J, Piha J, Almqvist F. Validity of child psychiatric screening methods. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;7(2):85–85. doi: 10.1007/s007870050052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neiss M, Rowe DC, Rodgers JL. Does education mediate the relationship between IQ and age at first birth? A behavioural genetic analysis. J Biosoc Sci. 2002;34(02):259–275. doi: 10.1017/s0021932002002596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Drotar D, Sturm L. Influences on the home environment of preschool children with early histories of nonorganic failure-to-thrive. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1989;10(5):229–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baker-Henningham H, Powell C, Walker S, Grantham-McGregor S. Mothers of undernourished Jamaican children have poorer psychosocial functioning and this is associated with stimulation provided in the home. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2003;57(6):786–792. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Watson JE, Kirby RS, Kelleher KJ, Bradley RH. Effects of poverty on home environment: an analysis of three-year outcome data for low birth weight premature infants. J Pediatr Psychol. 1996;21(3):419–431. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/21.3.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramchandani P, Psychogiou L. Paternal psychiatric disorders and children’s psychosocial development. Lancet. 2009;374(9690):646–653. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60238-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Downey G, Coyne JC. Children of Depressed Parents - an Integrative Review. Psychol Bull. 1990;108(1):50–76. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goodman SH, Gotlib IH. Risk for psychopathology in the children of depressed mothers: A developmental model for understanding mechanisms of transmission. Psychol Rev. 1999;106(3):458–490. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.106.3.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feldman MA, Walton-Allen N. Effects of maternal mental retardation and poverty on intellectual, academic, and behavioral status of school-age children. Am J Ment Retard. 1997;101(4):352–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McConnell D, Llewellyn G, Mayes R, Russo D, Honey A. Developmental profiles of children born to mothers with intellectual disability. J Intellect Dev Dis. 2003;28(2):122–134. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aunos M, Feldman M, Goupil G. Mothering with intellectual disabilities: Relationship between social support, health and well-being, parenting and child behaviour outcomes. J Appl Res Intellect. 2008;21(4):320–330. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bradley RH, Whiteside L, Caldwell BM, Casey PH, Kelleher K, Pope S, Swanson M, Barrett K, Cross D. Maternal IQ, the Home Environment, and Child IQ in Low Birthweight, Premature Children. Int J Behav Dev. 1993;16(1):61–74. [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Bakel HJA, Riksen-Walraven JM. Parenting and Development of One-Year-Olds: Links with Parental, Contextual, and Child Characteristics. Child Dev. 2002;73(1):256. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fergusson DM, Lynskey MT, Horwood LJ. The effect of maternal depression on maternal ratings of child behavior. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1993;21(3):245–269. doi: 10.1007/BF00917534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]