Abstract

The complex interactions between aphids and their host plant are species-specific and involve multiple layers of recognition and defense. Aphid salivary proteins, which are released into the plant during phloem feeding, are a likely mediator of these interactions. In an approach to identify aphid effectors that facilitate feeding from host plants, eleven Myzus persicae (green peach aphid) salivary proteins and the GroEL protein of Buchnera aphidicola, a bacterial endosymbiont of this aphid species, were expressed transiently in Nicotiana tabacum (tobacco). Whereas two salivary proteins increased aphid reproduction, expression of three other aphid proteins and GroEL significantly decreased aphid reproduction on N. tabacum. These effects were recapitulated in stable transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana (Arabidopsis) plants. Further experiments with A. thaliana expressing Mp55, a salivary protein that increased aphid reproduction, showed lower accumulation of 4-methoxyindol-3-ylmethylglucosinolate, callose, and hydrogen peroxide in response to aphid feeding. Mp55-expressing plants also were more attractive for aphids in choice assays. Silencing Mp55 gene expression in M. persicae using RNA interference approaches reduced aphid reproduction on N. tabacum, A. thaliana, and Nicotiana benthamiana. Together, these results demonstrate a role for Mp55, a protein with as yet unknown molecular function, in the interaction of M. persicae with its host plants.

Introduction

Aphids feed from host plants by inserting their stylets and navigating between cells to reach the phloem where they ingest phloem sap. During feeding aphids produce two different types of saliva, gelling and watery (Tjallingii 2006). Gelling saliva forms a proteinaceous sheath around the stylets, protecting them as the aphids probe (Miles 1999). Watery saliva is injected into the phloem and is thought to influence aphid-host plant compatibility. Similar to bacterial pathogens, aphids secrete effector proteins into plant cells, thereby modulating cellular activities. Protein effectors in aphid watery saliva, which is discontinuously injected into the phloem during aphid feeding, are required to circumvent plant defenses, but may also allow the plant to recognize the presence of aphid feeding (Tjallingii 2006; Will et al. 2007; Moreno et al. 2011).

Several proteomic studies have identified potential effectors in aphid saliva and salivary glands (Harmel et al. 2008; Carolan et al. 2009; Cooper et al. 2010; Carolan et al. 2011; Cooper et al. 2011; Cui et al. 2012; Nicholson et al. 2012; Will et al. 2012; Rao et al. 2013). In addition to aphid-encoded proteins, proteins produced by Buchnera aphidicola, obligate bacterial endosymbionts of aphids, have been found in the secreted saliva (Filichkin et al. 1997; Vandermoten et al. 2014). The heat shock protein GroEL, which is the most abundant of these bacterial proteins, also has been reported in the aphid hemolymph (van den Heuvel et al. 1994; van den Heuvel et al. 1997), suggesting potential transport from the bacteriocytes to the salivary glands.

To date, only a few of the identified salivary proteins have been subjected to functional characterization. Calcium-binding proteins in aphid saliva can trigger the condensation of forisomes, protein bodies found in many Fabaceae that block phloem sieve elements in their dispersed form (Will et al. 2007; Will et al. 2009). However, a more recent study showed that this forisome phase reversal may occur only in vitro and not when aphids are actually feeding from plants (Walker and Medina-Ortega 2012).

Transgenic expression of individual aphid salivary proteins in plants can affect aphid fecundity (Atamian et al. 2013; Pitino and Hogenhout 2013). C002, the currently best-studied salivary effector, is aphid-specific and facilitates feeding (Mutti et al. 2008). Silencing of C002 transcription reduces aphid fitness (Mutti et al. 2006; Pitino et al. 2011) and, conversely, C002 overexpression in planta increases aphid reproduction (Bos et al. 2010). The latter effect is species-specific; Myzus persicae (green peach aphid) C002 protein expression in transgenic plants promotes colonization by this aphid species, whereas the Acyrthosiphon pisum (pea aphid) homolog does not (Pitino and Hogenhout 2013). In planta expression of two other proteins from M. persicae salivary glands, Mp10 and Mp42, reduced aphid reproduction (Bos et al. 2010).

Plants have evolved to recognize specific herbivores and have multiple defenses against aphid colonization. Plant hormone and signaling pathways, including the jasmonic acid (JA) and salicylic acid (SA) pathways, are activated upon aphid feeding (Thompson and Goggin 2006). Induction of the JA pathway reduces aphid growth on Arabidopsis thaliana (Arabidopsis) (Ellis et al. 2002). It is hypothesized that some phloem-feeding insects induce the SA-related signaling pathways, which negatively influence more effective defenses that are regulated by JA signaling (Walling 2008; Dicke et al. 2009).

Molecular interactions between M. persicae and A. thaliana have been studied extensively (Louis et al. 2012). In response to aphid feeding, A. thaliana specifically induces the production of indole glucosinolates and the conversion of indol-3-ylmethylglucosinolate (I3M) to 4-methoxyindol-3-ylmethylglucosinolate (4MI3M), which is a more effective feeding deterrent (Kim and Jander 2007). Natural variation in the production of 4MI3M affects A. thaliana resistance to M. persicae (Pfalz et al. 2009). Another plant defense strategy against aphids is callose deposition at the feeding site and in the phloem sieve elements (Botha and Matsiliza 2004; Kusnierczyk et al. 2008). By increasing callose formation and plugging the sieve elements, plants are able to inhibit feeding. Reactive oxygen species, particularly hydrogen peroxide, which is observed specifically at the site of aphid feeding (Martinez de Ilarduya et al. 2003) also have been implicated in aphid defense (Kusnierczyk et al. 2008). A mutation in the Arabidopsis respiratory burst oxidase homolog D (RbohD) gene, resulting in decreased H2O2 accumulation, causes increased aphid sensitivity (Miller et al. 2009).

In order to identify and characterize additional aphid salivary effectors, we cloned individual genes encoding secreted M. persicae salivary proteins for expression in A. thaliana, Nicotiana benthamiana, and Nicotiana tabacum (tobacco). Aphid bioassays determined whether these salivary proteins promote aphid feeding and/or are recognized by plants to mount defense responses. Further functional studies were conducted with one aphid effector protein to determine its effects on plant responses to aphid feeding.

Results

M. persicae effector proteins affect reproduction

Proteins that have been identified in proteomic studies of secreted aphid saliva are likely to be effectors that mediate plant-aphid interactions. We used twelve of these secreted M. persicae proteins (Table 1) in further experiments to determine their role in plant-aphid interactions. Following a published nomenclature for M. persicae salivary proteins (Bos et al. 2010), the nine previously un-studied aphid salivary proteins have been named Mp55-Mp63, respectively. Among the eleven proteins, seven are aphid-specific and have no known homologs in other species. No predicted functional domains were identified in these proteins with NCBI protein BLAST (blastp) and the Simple Modular Architecture Research Tool (Schultz et al. 1998; Letunic et al. 2012). Of the remaining four proteins, Mp56 is a predicted retinol dehydrogenase, Mp59 a regucalcin (SMP-30), Mp62 an AMP-dependent CoA ligase, and Mp63 a predicted hydroxyacyl dehydrogenase.

Table 1.

| Protein name |

Genbank ID | Size (kD) |

Predicted function |

Signal sequence |

Proteomic reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MpC002 | EC389503.1 | 28 | Unknown | Yes |

Harmel et al., 2008 Mutti et al., 2008 |

| Mp1 | EE571823.1 | 16 | Unknown | Yes |

Harmel et al., 2008 Carolan et al., 2009 Carolan et al., 2011 |

| Mp55 | EC389393.1 | 40 | Unknown | Yes | Harmel et al., 2008 |

| Mp56 | EC388700.1 | 32 | Retinol dehydrogenase | No | Harmel et al., 2008 |

| Mp57 | EC388952.1 | 44 | Unknown | Yes | Harmel et al., 2008 |

| Mp58 | ES225976.1 | 17 | Unknown | Yes |

Harmel et al., 2008 Carolan et al., 2009 Carolan et al., 2011 |

| Mp59 | EC387947.1 | 36 | Regucalcin SMP 30 | No |

Carolan et al., 2009 Carolan et al., 2011 |

| Mp60 | EC389958.1 | 12 | Unknown | Yes | Harmel et al., 2008 |

| Mp61 | EC389075.1 | 13 | Unknown | No | Harmel et al., 2008 |

| Mp62 | ES221969.1 | 19 | AMP dependent CoA ligase | No | Harmel et al., 2008 |

| Mp63 | DW010534.1 | 27 | Hydroxyacyl dehydrogenase | No | Harmel et al., 2008 |

| GroEL | AF367248.1 | 58 | Heat shock protein | No | Vandermoten et al., 2014 |

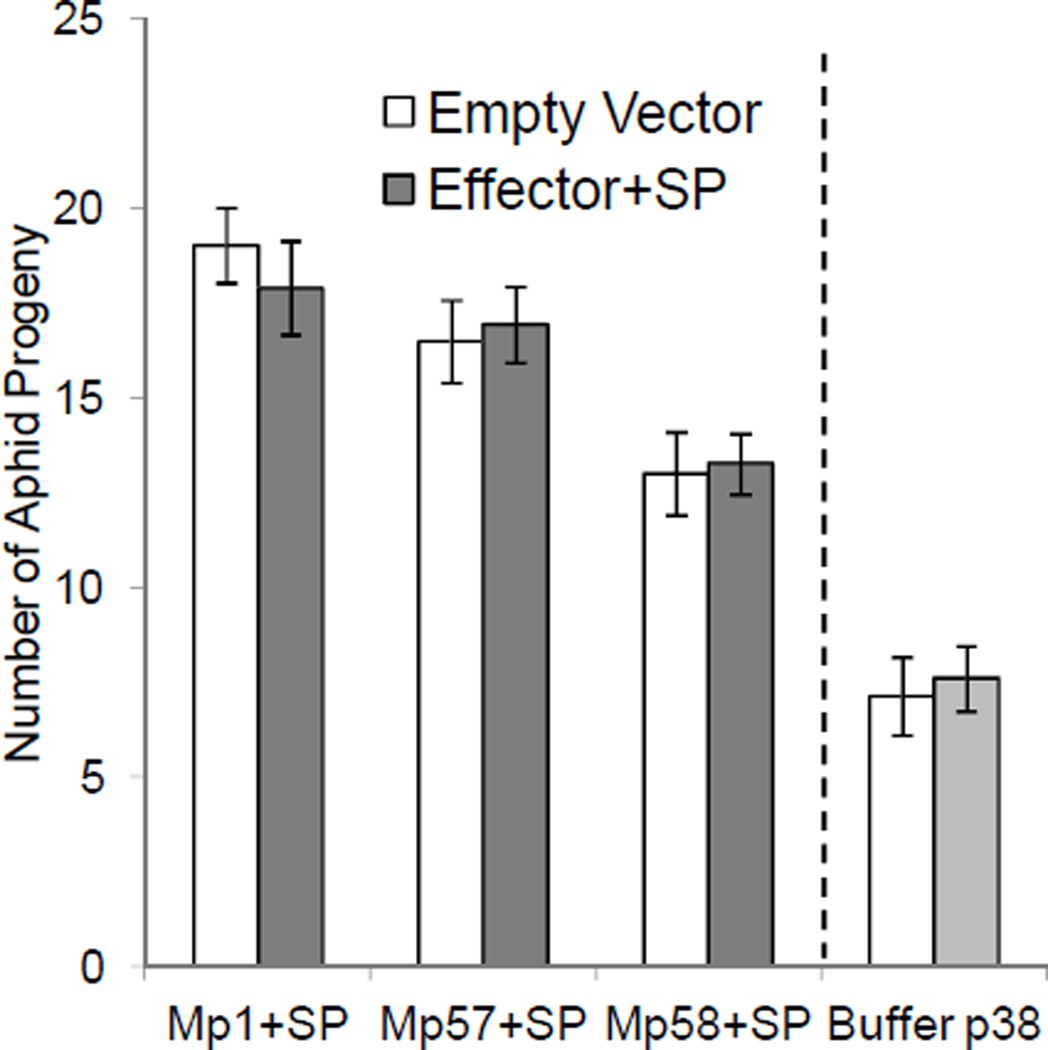

Full-length sequences for the predicted salivary proteins were obtained from salivary gland cDNA sequences (Ramsey et al. 2007) and the Buchnera Mp genome sequence (Jiang et al. 2013). Genes were amplified from cDNA or genomic DNA (GroEL) by PCR and were cloned into Agrobacterium plasmids for plant transformation. Although all twelve of the proteins were found in secreted aphid saliva, only six have predicted secretion signal sequences, as determined by SignalP v3 (Bendtsen et al. 2004) (Table 1). In initial experiments, three proteins (Mp1, Mp57 and Mp58), with their signal sequences intact, were expressed transiently from the constitutive cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter in N. tabacum for aphid bioassays (Fig. 1). In planta expression of the transgenes was verified by PCR (Supplementary Fig. 1A). A second Agrobacterium strain encoding a turnip crinkle virus coat protein, p38, which suppresses native plant gene silencing (Thomas et al. 2003), was co-infiltrated with each aphid effector construct to promote gene expression. In control experiments, transient expression of p38 alone had no significant effect on aphid reproduction (Fig. 1). Mp1, Mp57, and Mp58 expression did not affect aphid fecundity (Fig. 1), suggesting that cleavage of the signal sequences during secretion into the saliva might be required for in planta function of these proteins.

Fig. 1.

Overexpression of M. persicae salivary effector proteins with signal peptides does not alter aphid fecundity. Effector proteins with their signal peptides and a coat protein of the turnip crinkle virus p38, which suppresses silencing were expressed in N. tabacum using agroinfiltration. For each comparison, experimental and control samples were infiltrated into plants grown at the same time. Difference in aphid growth on control plants is due to environmental variation from one experiment to the next. After 3 days, a single adult aphid was caged on the infiltrated area and its progeny were counted after 7 days, (mean ± SE n = 15–20) *P<0.05, two-tailed Student's t-test comparing protein-expressing and empty vector samples and p38 to MgCl2 control buffer. SP = signal peptide.

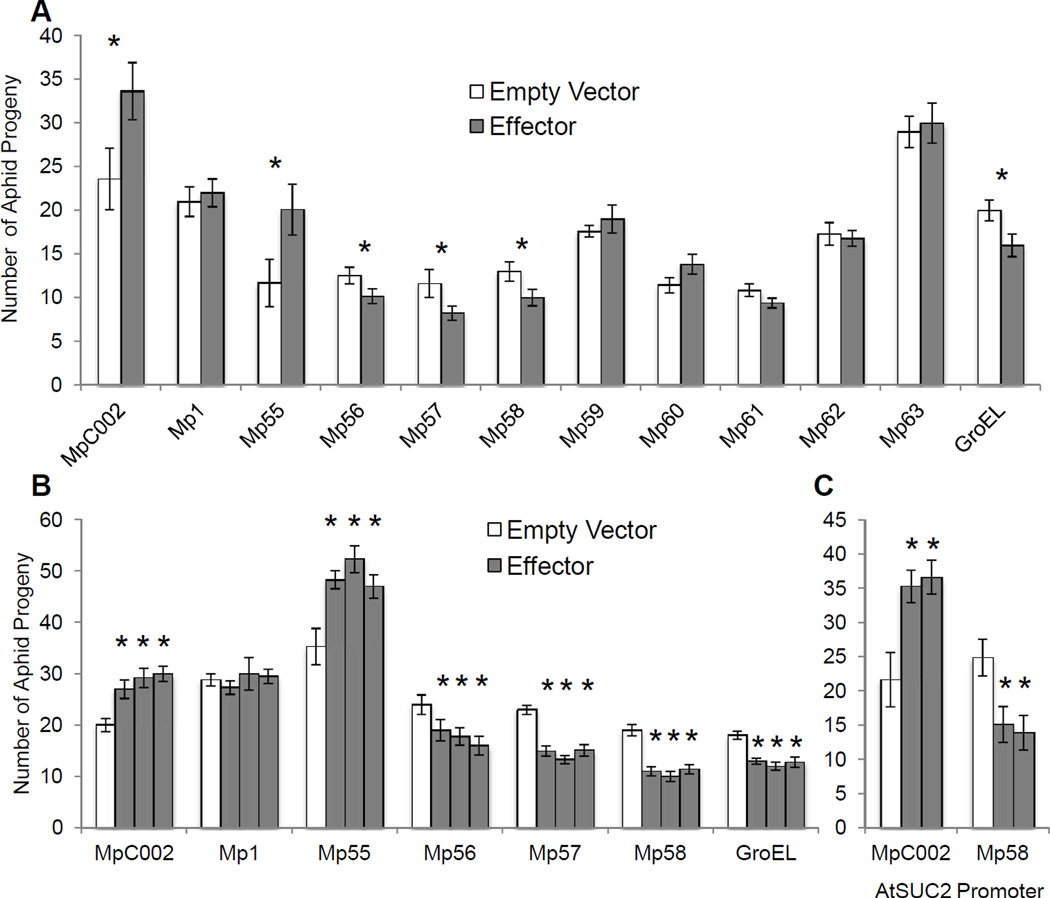

In further experiments, all salivary proteins with predicted signal sequences were cloned without these sequences for in planta expression and aphid bioassays. In planta expression of the transgenes was verified by PCR (Supplementary Fig. 1B). Two effector proteins, Mp55 and MpC002, increased aphid fecundity on N. tabacum (Fig. 2A). Three M. persicae salivary proteins (Mp56, Mp57, and Mp58) and GroEL decreased aphid reproduction, likely through activation of plant defense responses. Six other M. persicae effector proteins, Mp1, Mp59, Mp60, Mp60, Mp61, Mp62 and Mp63, did not significantly affect aphid fecundity on N. tabacum (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Overexpression of M. persicae salivary effector proteins alters aphid fecundity. (A) Effector proteins were expressed in N. tabacum using agroinfiltration and, after 3 days, a single adult aphid was caged on the infiltrated area and its progeny were counted after 7 days. For each comparison, experimental and control samples were infiltrated into plants grown at the same time. Difference in aphid growth on control plants is due to environmental variation from one experiment to the next. (B) Independent stable A. thaliana transgenic lines expressing M. persicae effector proteins under the constitutive 35S promoter. A single aphid was caged on a leaf of a three-week-old plant and its progeny counted after 7 days. (C) Independent stable A. thaliana transgenic lines expressing M. persicae effector proteins under the phloem specific promoter AtSuc2. A single aphid was caged on a leaf of a three-week-old plant and its progeny counted after 7 days (mean ± SE, n = 15–20) *P<0.05, two-tailed Student's t-test comparing protein-expressing and empty vector samples.

To confirm the observed effects, salivary proteins that altered aphid reproduction on N. tabacum, were expressed in stable transgenic A. thaliana. Mp1, a highly expressed salivary protein that was previously investigated (Pitino and Hogenhout 2013), also was included in this experiment. In planta expression of the transgenes was verified by PCR (Supplementary Fig. 1C). For each salivary protein construct, three independent transgenic A. thaliana lines were created and tested with aphids, showing similar results in each case (Fig. 2B). For each tested salivary protein, the effect on aphid reproduction on A. thaliana was similar to that previously observed with transient expression in N. tabacum (Fig. 2A): Mp55 and MpC002 increased reproduction; Mp58, Mp56, Mp57, and GroEL decreased reproduction; and Mp1 caused no significant effect (Fig. 2B).

Aphids feed primarily from the plant phloem, suggesting that this could be where salivary proteins function in plant-aphid interactions. Therefore, we generated stable transgenic lines expressing MpC002 and Mp58 under the sucrose transporter promoter, AtSuc2, which is phloem-specific (Gottwald et al. 2000). In planta expression of the transgenes was verified by PCR (Supplementary Fig. 1C). As in the case of expression from the constitutive 35S promoter in N. tabacum and A. thaliana, expression of MpC002 and Mp58 from the AtSuc2 promoter increased and decreased aphid reproduction, respectively (Fig. 2C). To confirm protein accumulation in the vascular tissue, MpC002 was fused to GFP and the localization of the protein produced from the 35S and AtSuc2 promoters was visualized in tobacco (Supplementary Fig. 2).

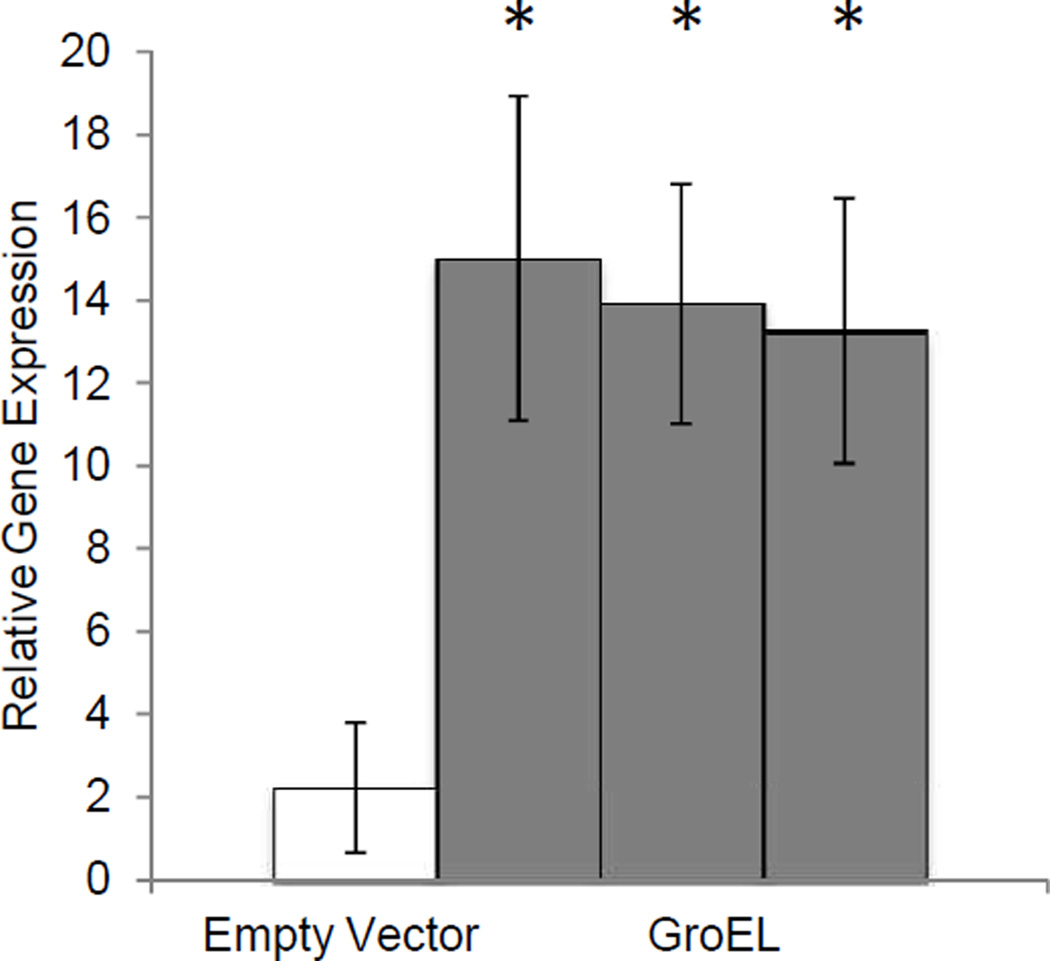

GroEL is a highly conserved bacterial protein (Baumann et al. 1996; Humphreys and Douglas 1997), with over 80% sequence identity between the Buchnera Mp and Escherichia coli homologs (Hara and Ishikawa 1990). Thus it is possible that plants would recognize this protein as an indicator of bacterial infection and mount a defense response. Induction of PR1 gene expression by transgenic expression of GroEL in A. thaliana is consistent with this hypothesis of up-regulated anti-microbial defense responses (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

PR1 gene expression analysis of pathogenesis response gene PR-1 in GroEL-expressing A. thaliana. Gene expression was measured by quantitative RT-PCR relative to a control gene, Elongation Factor a, in 3 week old A. thaliana stably expressing the B. Aphidicola GroEL gene. Three independent transgenic lines, were tested in the absence of aphid feeding. Mean ± SE, n=6, *P<0.05, two-tailed Student's t-test relative to the empty vector control.

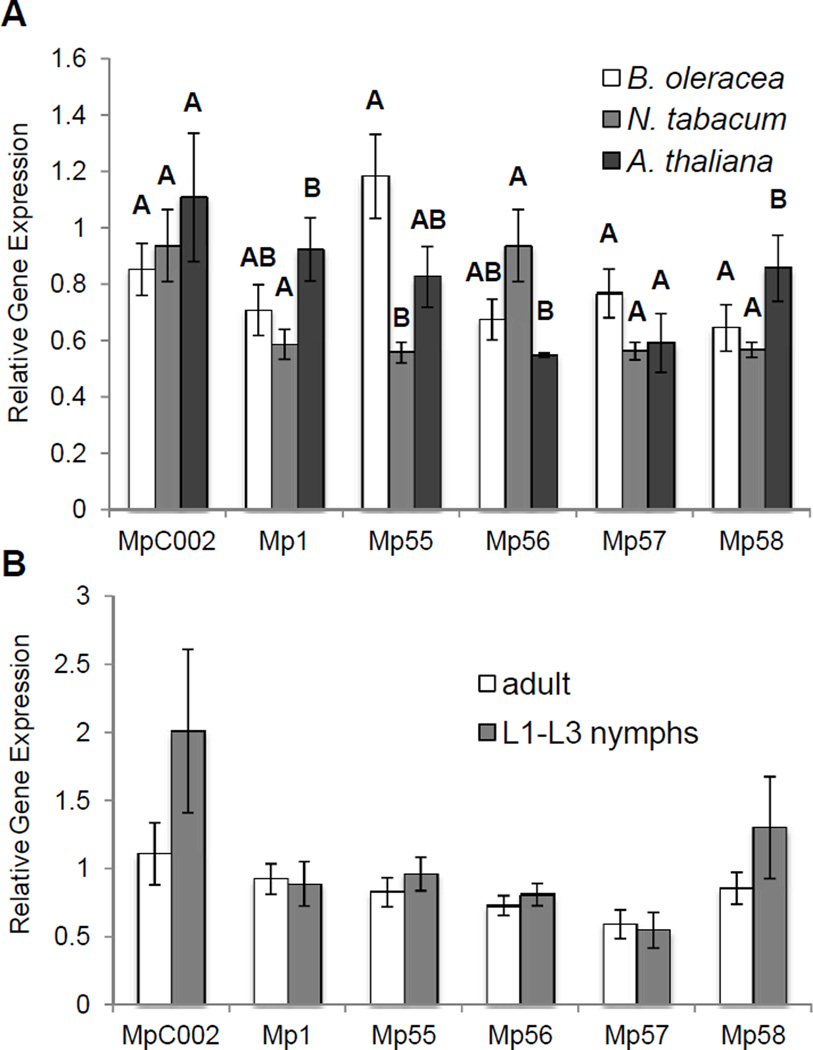

M. persicae effector gene expression depends on the host plant

Different effector proteins may be important for M. persicae feeding from multiple host plants. To determine whether this is the case, expression of the six previously identified aphid effector genes (Mp1, C002, Mp55, Mp56, Mp57, and Mp58) was measured in aphids feeding from Brassica oleracea (cabbage), N. tabacum, and A. thaliana. (Fig. 4A). These host plants differentially affect Mp55 expression in the aphids, with the highest expression on B. oleracea, twice as high as when feeding from N. tabacum. In contrast to the host plant effects, expression of six tested M. persicae salivary genes was not affected by aphid age; no differences in salivary effector gene expression were seen when comparing adults and nymphs (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

M. persicae salivary effector gene expression is host plant dependant, but not influenced by age. Expression levels of M. persicae salivary effector genes were measured by quantitative RT-PCR relative to a control ribosomal gene (RpL7). (A) Aphids were reared on cabbage (B. oleracea), tobacco (N. tabacum) and wild-type A. thaliana (Col-0), (mean ± SE n=6) ANOVA tukey HSD letters correspond to individual clusters only. (B) Adult, and L1-L3 nymphs were reared on wild-type A. thaliana (Col-0). Gene expression was measured by qRT-PCR, mean ± SE n=6, no significant differences, two-tailed Student's t-test.

Mp55 expression promotes aphid fecundity

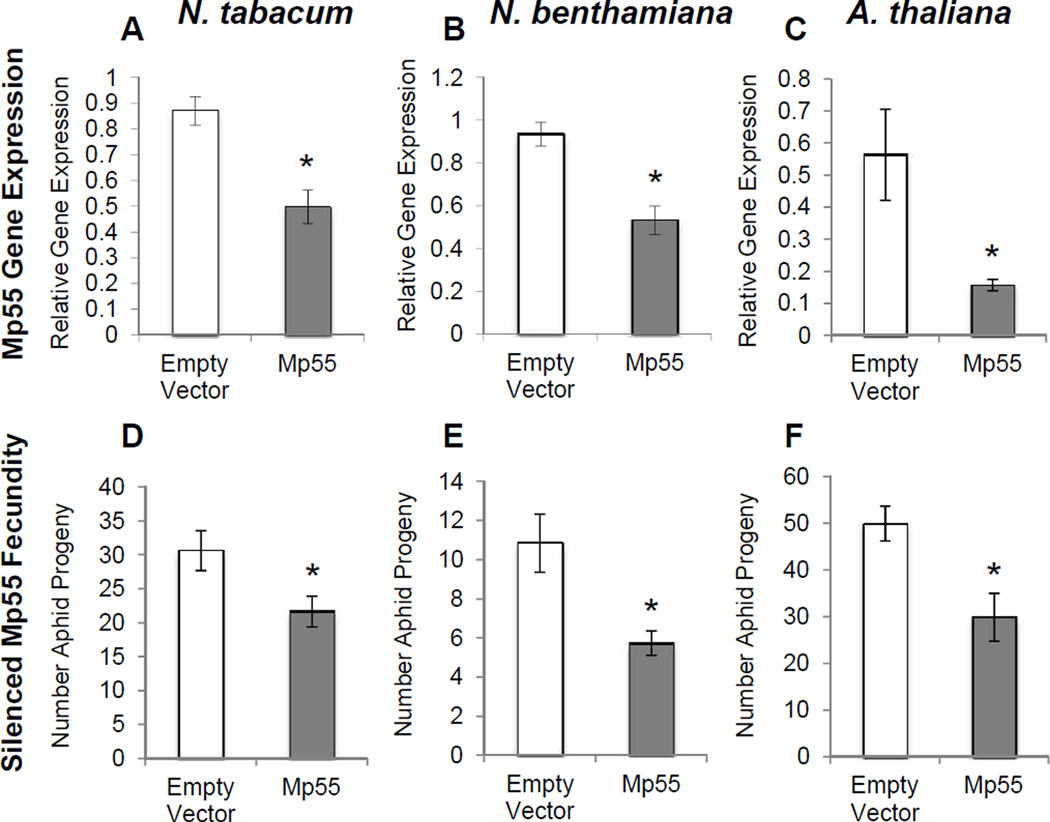

Mp55, which increases aphid fecundity when over-expressed in both N. tabacum and A. thaliana (Fig. 2), was chosen for further analysis. The Mp55 gene sequence is identical in two sequenced M. persicae lineages (American clone G006 and British clone O, available at www.aphidbase.com) and has a likely homolog in A. pisum with 53% sequence identity at the amino acid level (Supplementary Fig. 3). When Mp55 gene expression was silenced in M. persicae through plant-mediated RNA interference in N. tabacum (Fig. 5A), N. benthamiana (Fig. 5B) and A. thaliana (Fig. 5C), there was decreased aphid reproduction in each case (Fig. 5D–F).

Fig. 5.

M. persicae salivary effector protein Mp55 increases aphid fecundity. M. persicace expression levels of Mp55 relative to ribosomal control gene (RpL7) was measured by qRT-PCR when expressing a hairpin RNAi knock-down construct in (A) N. tabacum and (B) N. benthamiana using agroinfiltration and stably expressed in (C) A. thaliana. Knock-down of M. persicae Mp55 reduces aphid fecundity using agroinfiltration in (D) N. tabacum (E) N. benthamiana and stable transformation in (F) A. thaliana. For agroinfiltration after 3 days a single adult aphid was caged on the infiltrated area and for stable A. thaliana transformants a single adult aphid was caged on a three-week-old leaf. Aphid progeny were counted after 7 days (mean ± SE, bioassays n=20; qRT-PCR n=6) *P<0.05, two-tailed Student's t-test.

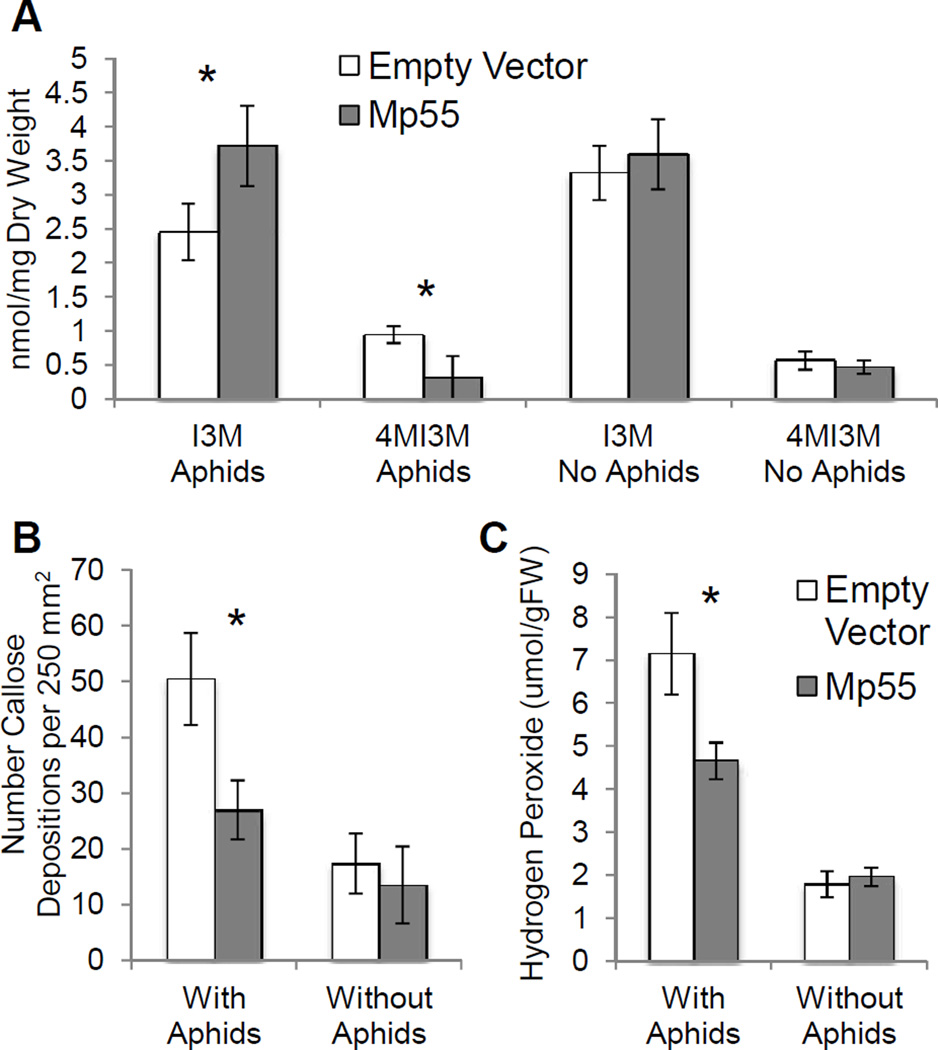

Suppression of defenses is a possible cause for the increased aphid reproduction on plants expressing Mp55. As aphid feeding induces conversion of I3M to 4MI3M, which is a more deterrent glucosinolate for M. persicae (Kim and Jander 2007), leaf indole glucosinolates were measured in Mp55-expressing A. thaliana and control plants. The 4MI3M levels were significantly lower in Mp55-expressing plants compared to those transformed with the empty vector (Fig. 6A). Conversely, I3M was more abundant in Mp55-transgenic A. thaliana, suggesting a lower level of I3M to 4MI3M conversion.

Fig. 6.

Salivary protein Mp55 suppresses A. thaliana defenses. Control plants and plants expressing the Mp55 protein were fed upon by aphids for 48 hours. (A) Indole glucosinolate profile of three-week-old A. thaliana leaves (mean ± SE of n = 8) *P<0.05, two-tailed student's t-test; (B) Callose deposits in a 250 mm2 area in three-week-old A. thaliana leaves (mean ± SE of n = 48) *P<0.05, two-tailed student's t-test; (C) Hydrogen peroxide levels in 3 week old A. thaliana leaves (mean ± SE of n = 5) *P<0.05, two-tailed Student's t-test.

Callose, which can plug phloem sieve elements, thereby inhibiting aphid feeding, is a common plant defense response against aphids (Botha and Matsiliza 2004). To determine whether this effect is reduced in plants expressing Mp55, aphids were fed for 48 hours on Mp55-transgenic and control plants. Mp55-transgenic A. thaliana had fewer callose deposits than the empty vector controls (Fig. 6B), suggesting that aphids could feed more easily on the Mp55-expressing plants. Additionally, aphids feeding from Mp55-transgenic A. thaliana induced less hydrogen peroxide accumulation in the leaves (Fig. 6C), a further indication of suppressed defense responses.

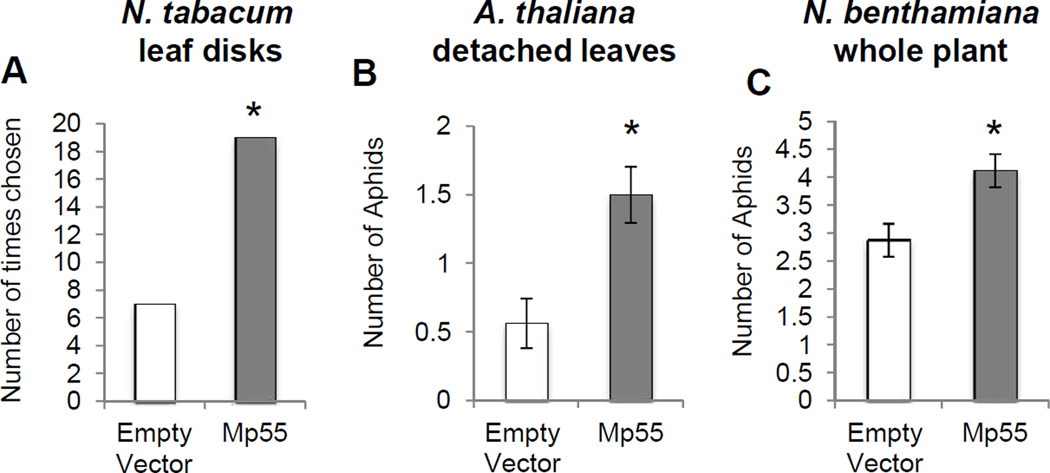

M. persicae prefer Mp55 plants

To determine whether M. persicae prefer plants overexpressing Mp55, N. tabacum leaf disks transformed with either Mp55 or an empty vector were placed in Petri dishes with a single adult aphid in the middle. After 24 hours, significantly more aphids chose leaf disks expressing Mp55 (Fig. 7A). In a similar experiment with detached leaves from Mp55- and empty vector-transgenic A. thaliana, aphids also chose the Mp55 leaves (Fig. 7B). In subsequent experiments, aphids were given a choice between entire N. benthamiana plants transiently expressing either Mp55 or the empty vector, growing together in the same pot. As in the case of leaf disks and whole leaves, aphids showed a significant preference for N. benthamiana expressing Mp55 compared to the empty vector controls (Fig. 7C).

Figure 7.

M. persicae has a preference for plants expressing Mp55. Expression of Mp55 in (A) N. tabacum leaf disks through agroinfiltration, a single aphid was given a choice between Mp55 and empty vector disks placed in a Petri dish, *P<0.05; χ2-test, n=35. (B) Detached A. thaliana leaves stably expressing Mp55, three adult aphids were given a choice between Mp55 and empty vector leaves placed in a petri dish, (mean ± SE, n=30) *P<0.05, two-tailed Student's t-test. (C) Expression of Mp55 through agroinfiltration of 4 week old whole N. benthamiana plants. Five adult aphids were given a choice between Mp55 and empty vector expressing plants in the same pot, (mean ± SE, n=20) *P<0.05, two-tailed Student's t-test.

Discussion

Aphids modulate plant cellular processes by injecting pulses of salivary proteins into the phloem as they are feeding. Among twelve tested M. persicae salivary proteins, two promote aphid reproduction, four decrease aphid progeny production, and six have no significant effects (Fig. 2). Our results showing no difference in aphid reproduction on plants expressing Mp1 are in agreement with a previous M. persicae effector screen in N. benthamiana (Bos et al. 2010). However, a follow-up study showed increased aphid reproduction on stable transgenic A. thaliana expressing Mp1. Although silencing Mp1 had no effect on aphid reproduction (Pitino and Hogenhout 2013), this could be explained by the incomplete reduction in the RNA levels of this abundantly expressed gene. Mp58 is homologous to Me10, a previously investigated Macrosiphum euphorbiae (potato aphid) effector protein. When overexpressed in N. benthamiana and Solanum lycopersicum (tomato) Me10 increased M. persicae and M. euphorbiae reproduction respectively (Atamian et al. 2013). This is in contrast to our findings with Mp58 (Fig. 2), but it is known that aphid effectors can act in a plant and aphid species-specific manner (Pitino and Hogenhout 2013).

In cases where salivary protein expression decreases aphid reproduction, this could be caused by plant recognition mechanisms and induction of defense responses. GroEL expression increases expression of the defense-related PR1 gene (Fig. 3). Although PR1 is induced by aphid feeding (Moran and Thompson 2001; Divol et al. 2007; Kusnierczyk et al. 2007), this protein has not been associated with aphid resistance in plants and may not be a direct cause of aphid resistance in our experiments (Fig. 2). However, consistent to our observations, expression of GroEL from a bacterial endosymbiont of Bemisia tabaci (silverleaf whitefly) confers resistance to some viruses in S. lycopersicum and N. benthamiana (Akad et al. 2007; Edelbaum et al. 2009), suggesting a general up-regulation of antimicrobial defenses.

Suppression of plant defense responses by M. persicae salivary protein Mp55 causes increased aphid reproduction (Fig. 2) and makes plants more attractive in choice assays (Fig. 7). The indole glucosinolate 4MI3M is an effective feeding deterrent for M. persicae (Kim and Jander 2007). Aphids feeding on Mp55-expressing A. thaliana induce lower levels of 4MI3M than on empty vector controls (Fig. 6A), suggesting reduced defense induction. In accordance with this, the level of the precursor indole glucosinolate, I3M, is increased in Mp55-transgenic plants. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that altered indole glucosinolate content in this experiment is an indirect effect of altered aphid feeding behavior or reproduction. Interestingly, it was previously shown that 4MI3M degradation is required for flg22-induced callose deposition in A. thaliana (Clay et al. 2009), suggesting that a 4MI3M breakdown product is a signaling intermediate in this pathway. Consistent with this, leaves of Mp55-expressing A. thaliana have less callose deposition in response to M. persicae feeding than the empty vector controls. Additionally, the defense signaling molecule hydrogen peroxide is less abundant in Mp55-expressing A. thaliana.

When feeding from different host plants M. persicae modifies its expression of salivary effector proteins (Fig. 4A), presumably to avoid activation of defenses and facilitate feeding. If Mp55 reduces 4MI3M glucosinolate production and perhaps other crucifer-specific defenses, it would be advantageous for aphids to increase expression of this gene in a targeted manner. Consistent with this hypothesis, Mp55 gene expression is higher on B. oleracea and A. thaliana than on N. tabacum (Fig. 4A). Further research will be required to determine whether modulation of salivary protein expression contributes to the ability of M. persicae to feed from a wide variety of host plants.

Expression of aphid salivary genes in plants can serve as a useful tool for identifying candidate effectors for further experiments. However, there are also limitations to this approach. For instance, it is likely that in planta expression from the 35S promoter will produce higher protein amounts than are biologically relevant. Aphids appear to modulate their salivary gene expression on different host plants (Fig. 4A). Thus, a certain amount of salivary protein may be optimal for M. persicae feeding and overexpression could result in either false positive or false negative effects in our experiments. Correct sub-cellular localization also may not be achieved through in planta expression of salivary proteins. Although aphids feed primarily from the phloem, the identified effectors also could mediate plant-aphid interactions in other cell types or in intercellular spaces. Nevertheless, the similar aphid growth effects that we see with salivary effectors expressed from the constitutive 35S promoter (Fig. 2B) and the phloem-specific AtSuc2 promoter (Fig. 2C), suggest that the location of expression may not be critical for some aphid salivary effectors. Once the molecular functions of these salivary effectors have been identified, it will be possible to conduct more detailed experiments to localize their functions during natural aphid feeding.

In summary, our results show that specific M. persicae effector proteins can influence aphid fecundity on host plants. Mp56, Mp57 and Mp58 decrease aphid reproduction, likely by activating plant defense responses, whereas MpC002 and Mp55 increase aphid fecundity. M. persicae effector gene expression varies on different host plants, suggesting this as a mechanism of host plant adaptation. Mp55, a protein with as yet unknown molecular function, reduces accumulation of a toxic glucosinolate, inhibits callose deposition, and lowers accumulation of hydrogen peroxide in A. thaliana. These results indicate that M. persicae secretes this effector into the plant in order to suppress plant defense responses and improve aphid performance.

Methods

Plants and Growth Conditions

Wild-type A. thaliana landrace Columbia-0 (Col-0) was obtained from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center (www.arabidiopsis.org). Wildtype and transgenic Col-0 were grown in Cornell Mix [(by weight, 56% peat moss, 35% vermiculite, 4% lime, 4% Osmocoat slow-release fertilizer (Scotts), and 1% Unimix (Peters)] in Conviron growth chambers in 20 × 40-cm nursery flats with at a photosynthetic photon flux density of 200 µmol m−2 s−1 and a 16 h photoperiod at 23°C and 50% relative humidity. Experiments were performed with three-week-old plants before flowering. Cabbage (Brassica oleracea var. Wisconsin Golden Acre; Seedway), N. tabacum (var. NC95), and N. benthamiana were germinated in Metro Mix 360 (Scotts), transplanted after 2 weeks to Cornell Mix, and grown in Conviron chambers as described above. Experiments were performed using plants that were 5 to 7 weeks old.

Insect rearing

Aphid experiments were conducted with a tobacco-adapted red lineage of M. persicae (Ramsey et al. 2007), which was obtained from S. Gray (USDA Plant Soil and Nutrition Laboratory, Ithaca, NY, USA). Aphids were raised on N. tabacum unless otherwise noted, with a 16 h day and a photosynthetic photon flux density of 200 µmol m−2 s−1 at 23°C and 50% relative humidity.

Aphid cDNA Synthesis

RNA was extracted from groups of 10 to 50 aphids. Aphids were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and ground to a fine powder using a paint shaker (Harbil) and 3 mm steel balls. Following homogenization, RNA was extracted using TRI Reagent (Sigma) and purified with the SV Total RNA Isolation Kit with on-column DNase treatment (Promega). From 1 µg of RNA, cDNA was reverse-transcribed using SMART MMLV reverse transcriptase (Clonetech) and oligo-dT12–18 as a primer.

Gene Cloning

Using cDNA sequences from M. persicae salivary glands (Ramsey et al. 2007), full-length sequences of salivary proteins were obtained. Only proteins that were verified to be found in M. persicae saliva through proteomics studies (Harmel et al. 2008; Carolan et al. 2009; Carolan et al. 2011) were chosen. Using the Gateway cloning system (Invitrogen) primers were designed corresponding to the coding regions with or without signal peptides (Supplemental Table 1). Using EX Taq DNA polymerase (Takara) genes were cloned into entry vector pDONR207 using BP clonase (Invitrogen). Followed by an LR reaction with LR clonase (Invitrogen) into destination vector pMDC32 or pMDC85 (Curtis and Grossniklaus 2003) for overexpression constructs driven by the 2x Cauliflower Mosaic Virus 35S promoter. Phloem specific constructs were also made by cutting out the 35S promoter and inserting the A. thaliana sucrose transporter promoter AtSuc2 (Gottwald et al. 2000). Restriction enzyme cut sites hindIII and kpnI were used for the pMDC32 vector and hindIII and pacI for pMDC85, primers were designed for the AtSuc2 promoter including the corresponding restriction site.

For knock-down by RNAi in aphids, at least 900 bp of MpC002, Mp1, Mp55, Mp56, Mp57, Mp58, Mp59, Mp60, Mp61, Mp62, Mp63 and GroEL, without the signal peptide, were cloned into pDONR207 (Invitrogen) following an LR reaction into destination vector pANDA 35HK (Miki and Shimamoto 2004) driven by the Cauliflower Mosaic Virus 35S promoter. The final destination plasmids containing a specific salivary effector gene sequence were transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101.

Stable A. thaliana Transformants

Using an established protocol (Clough and Bent 1998), A. thaliana Col-0 was grown until flowering and dipped in a sucrose solution containing A. tumefaciens GV3101 containing an expression vector with a single effector gene. T1 seed was collected and hygromycin-resistant transformants were selected on Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium (Murashige and Skoog 1962) containing 50µg/mL hygromycin. Hygromycin-resistant plants were transferred to soil, and T2 seeds were collected. Plants showing hygromycin resistance and expression of the transformed effector gene in the T2 generation were used for further analysis. RT-PCR was performed on all independent lines to verify effector gene expression (Supplementary Fig. 1)

Transient Overexpression Assays

Recombinant A. tumefaciens GV3101 cultures, at a final OD600 (optical density at 600 nm) of 0.2, expressing an empty vector, a single effector protein, or hairpin RNAi structure were pressure infiltrated into N. tabacum or N. benthamiana using a 1 ml plastic syringe. A vector expressing the capsid protein of turnip crinkle virus tomato (p38), which suppresses native plant protein silencing (Thomas et al. 2003), was co-infiltrated to increase the duration of protein expression. Experiments for each empty vector and effector comparison were conducted at the same time, two spots per leaf, two leaves per plant were infiltrated with the same construct and plants were randomized in the flats. Three days after infiltration, a single adult aphid was caged on the infiltrated area and its progeny were counted after 7 days. Expression of the effector transcript was verified for each aphid bioassay (Supplementary Fig. 1).

A. thaliana Bioassays

Transgenic A. thaliana was grown as described above, a single adult aphid was caged on a leaf, and its progeny were counted after 7 days. A. thaliana plants transformed with an empty vector were used as controls. For each effector vs. control comparison, plants were grown at the same time in the same pots.

Quantitative Gene Expression Analysis

Total RNA was extracted using the SV Total RNA Isolation Kit with on-column DNase treatment (Promega). Abundance of all transcripts was analyzed by quantitative real-time reverse transcription qRT-PCR, using ribosomal protein RpL7, ubiquitously expressed and likely a single copy gene, as an internal standard. After extraction and DNAse treatment, 1µg of RNA was reverse transcribed using SMART MMLV reverse transcriptase (Clonetech) and oligo-dT12–18 as a primer. Gene specific primers were designed using Primer3 (iotools.umassmed.edu/bioapps/primer3_www.cgi) and can be found in (Supplemental Table 1). Reactions were performed with 5 µl of 2x Power SYBR Green (Applied Biosystems) and 800 nM primer in the 7900HT instrument (Applied Biosystems) with an initial incubation at 95°C for 10 min. The following cycle was repeated 40 times: 95°C for 15s, 60°C for 15s, and 72°C for 15s. The CT values were quantified and analyzed according to the standard curve method.

Glucosinolate Assays

Wildtype Col-0 and transgenic A. thaliana were grown as described above, and 30 aphids were caged for 48 hours on individual leaves. Leaf tissue was collected, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and lyophilized. Extraction and preparation of desulfoglucosinolates from leaf tissue was described previously (Barth and Jander 2006; Kim et al 2008). Desulfoglucosinolates were separated using a Waters 2695 HPLC and detected using a Waters 2996 photodiode array detector. For HPLC separation, the mobile phases were water (A) and 90% acetonitrile (B) with a flow rate of 1 mL min−1 at 23°C. Column linear gradients for samples were as follows: 0 to 1 min, 98% A; 1 to 6 min, 94% A; 6 to 8 min, 92% A; 8–16 min, 77% A; 16–20 min, 60% A; 20–25 min, 0% A; 25 to 27 min, hold at 0% A; 27 to 28 min, 98% A; 28–37 min, 98% A.

Callose Staining

Leaves were destained in 95% ethanol for 24 hours and washed for 30 min 3 times with 0.07M phosphate buffer and then stained with 0.01% analine blue in 0.07M phosphate buffer for 2 hours. Following staining the leaves were rinsed with 0.07M phosphate buffer 3 times for 20 min. Callose deposition was visualized at 360–380 nm and spots were counted.

Diaminobenzidine Staining

Wildtype Col-0 and stable transgenic A. thaliana were grown as described above, and 30 aphids were caged for 48 hours on individual leaves. Following aphid feeding, leaves were vacuum-infiltrated and stained with 3,3'diaminobenzidine (DAB) (Sigma-Aldrich). After destaining and bleaching, the leaves were ground in liquid nitrogen, homogenized in 0.2M HClO4, and centrifuged at 12,000 g for 10 minutes. Absorption of the supernatant was measured at 450 nm and compared to a standard curve of known hydrogen peroxide levels.

Aphid Choice Assays

Recombinant A. tumefaciens strain GV3101 expressing an empty vector or a gene for a single M. persicae effector protein was pressure-infiltrated using a 1 mL syringe into N. tabacum at a final OD600 of 0.2. Two days after infiltration, leaf disks 2 cm in diameter of empty vector and effector protein expressing plants were placed in a Petri dish with moist Whatman paper, a single adult aphid was released in the center, and its choice was recorded.

Transgenic A. thaliana was grown as described above for three weeks and a single leaf detached and placed in a petri dish with moist Whatman paper. Mp55 overexpression and empty vector control leaves were placed on opposite sides, a single adult aphid was released in the center, and its choice recorded.

Recombinant A. tumefaciens GV3101 expressing an empty vector or a single effector protein was pressure infiltrated using a 1mL syringe into N. benthamiana, at a final OD600 of 0.2. Pairs of experimental and control plants were grown together in the same pot. Three days after infiltration, five adult aphids were placed in the center of the pot and their choice of host plant was recorded.

Statistical Analysis

Aphid bioassays were compared using unpaired two-tailed t-tests, with a significance cutoff of α = 0.05. Aphid gene expression was compared using an unpaired t-test (α = 0.05) and ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD test. Aphid choice assays were compared using a chi-squared test. All statistical comparisons were conducted using JMP (2010) for Windows (SAS Institute Inc.). All sequence alignments were done using ClustalW2 (Larkin et al. 2007).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Fig. 1. M. persicae salivary effector gene expression in planta. (A) Expression of Mp1, Mp57 and Mp58 through agroinfiltration in N. tabacum with and without their signal peptides, used for bioassays. (B) Expression of effector proteins through agroinfiltration in N. tabacum used for aphid bioassays. (C) Expression of effector proteins in multiple independent stable transgenic Col-0 lines used for bioassays. Driven by the 2x Cauliflower Mosaic Virus 35S promoter unless otherwise noted; AtSuc2, A. thaliana sucrose transporter; EV = empty vector control.

Supplementary Fig. 2. Visualization of MpC002 tagged with GFP. (A) Expression of MpC002 through agroinfiltration under the 2x Cauliflower Mosaic Virus 35S promoter, 2 days post infiltration, shows expression in the whole leaf. (B) Expression of MpC002 through agroinfiltration under the phloem-specific A. thaliana sucrose transporter, AtSuc2, shows expression in the vascular tissue.

Supplementary Fig. 3. Protein sequence alignment of Mp55 and its likely homolog in A. pisum. Alignment done in ClustalW2, with 53% sequence identity at the amino acid level; GenBank sequence IDs: A. pisum, LOC100569515; M. persicae, EC389393.1.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by United States Department of Agriculture – National Institute of Food and Agriculture awards 2010-65105-20558 and 2012-67013-19350 to GJ. DAE was funded by National Institutes of Health/National Institute of General Medical Sciences grant 5T32GM008500. DNA sequence data were Elzinga, MPMI downloaded from AphidBase, www.aphidbase.com. Funding for Myzus persicae clone O genomic sequencing was provided by The Genome Analyses Centre (TGAC) Capacity and Capability Challenge programme project CCC-15 and BB/J004553/1 from the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) and the John Innes Foundation.

References

- Akad F, Eybishtz A, Edelbaum D, Gorovits R, Dar-Issa O, Iraki N, Czosnek H. Making a friend from a foe: expressing a GroEL gene from the whitefly Bemisia tabaci in the phloem of tomato plants confers resistance to tomato yellow leaf curl virus. Arch. Virol. 2007;152:1323–1339. doi: 10.1007/s00705-007-0942-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atamian HS, Chaudhary R, Dal Cin V, Bao E, Girke T, Kaloshian I. In planta expression or delivery of potato aphid Macrosiphum euphorbiae effectors Me10 and Me23 enhances aphid fecundity. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2013;26:67–74. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-06-12-0144-FI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann P, Baumann L, Clark MA. Levels of Buchnera aphidicola chaperonin GroEL during growth of the aphid Schizaphis graminum. Curr. Microbiol. 1996;32:279–285. [Google Scholar]

- Bendtsen JD, Nielsen H, von Heijne G, Brunak S. Improved prediction of signal peptides: SignalP 3.0. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;340:783–795. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos JIB, Prince D, Pitino M, Maffei ME, Win J, Hogenhout SA. A functional genomics approach identifies candidate effectors from the aphid species Myzus persicae (green peach aphid) PLoS Genet. 2010;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botha CEJ, Matsiliza B. Reduction in transport in wheat (Triticum aestivum) is caused by sustained phloem feeding by the Russian wheat aphid (Diuraphis noxia) S. Afr. J. Bot. 2004;70:249–254. [Google Scholar]

- Carolan JC, Fitzroy CI, Ashton PD, Douglas AE, Wilkinson TL. The secreted salivary proteome of the pea aphid Acyrthosiphon pisum characterised by mass spectrometry. Proteomics. 2009;9:2457–2467. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carolan JC, Caragea D, Reardon KT, Mutti NS, Dittmer N, Pappan K, Cui F, Castaneto M, Poulain J, Dossat C, Tagu D, Reese JC, Reeck GR, Wilkinson TL, Edwards OR. Predicted effector molecules in the salivary secretome of the pea aphid (Acyrthosiphon pisum): a dual transcriptomic/proteomic approach. J. Proteome Res. 2011;10:1505–1518. doi: 10.1021/pr100881q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clay NK, Adio AM, Denoux C, Jander G, Ausubel FM. Glucosinolate metabolites required for an Arabidopsis innate immune response. Science. 2009;323:95–101. doi: 10.1126/science.1164627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough SJ, Bent AF. Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant. J. 1998;16:735–743. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper WR, Dillwith JW, Puterka GJ. Salivary proteins of Russian wheat aphid (Hemiptera: Aphididae) Environ. Entomol. 2010;39:223–231. doi: 10.1603/EN09079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper WR, Dillwith JW, Puterka GJ. Comparisons of salivary proteins from five aphid (Hemiptera: Aphididae) species. Environ. Entomol. 2011;40:151–156. doi: 10.1603/EN10153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui F, Smith CM, Reese J, Edwards O, Reeck G. Polymorphisms in salivary-gland transcripts of Russian wheat aphid biotypes 1 and 2. Insect Sci. 2012;19:429–440. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis MD, Grossniklaus U. A gateway cloning vector set for high-throughput functional analysis of genes in planta. Plant Physiol. 2003;133:462–469. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.027979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dicke M, van Loon JJ, Soler R. Chemical complexity of volatiles from plants induced by multiple attack. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2009;5:317–324. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Divol F, Vilaine F, Thibivilliers S, Kusiak C, Sauge MH, Dinant S. Involvement of the xyloglucan endotransglycosylase/hydrolases encoded by celery XTH1 and Arabidopsis XTH33 in the phloem response to aphids. Plant Cell Environ. 2007;30:187–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2006.01618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelbaum D, Gorovits R, Sasaki S, Ikegami M, Czosnek H. Expressing a whitefly GroEL protein in Nicotiana benthamiana plants confers tolerance to tomato yellow leaf curl virus and cucumber mosaic virus, but not to grapevine virus A or tobacco mosaic virus. Arch. Virol. 2009;154:399–407. doi: 10.1007/s00705-009-0317-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis C, Karafyllidis L, Turner JG. Constitutive activation of jasmonate signaling in an Arabidopsis mutant correlates with enhanced resistance to Erysiphe cichoracearum, Pseudomonas syringae, and Myzus persicae. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2002;15:1025–1030. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2002.15.10.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filichkin SA, Brumfield S, Filichkin TP, Young MJ. In vitro interactions of the aphid endosymbiotic SymL chaperonin with barley yellow dwarf virus. J. Virol. 1997;71:569–577. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.1.569-577.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottwald JR, Krysan PJ, Young JC, Evert RF, Sussman MR. Genetic evidence for the in planta role of phloem-specific plasma membrane sucrose transporters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2000;97:13979–13984. doi: 10.1073/pnas.250473797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara E, Ishikawa H. Purification and partial characterization of symbionin, an aphid endosymbiont-specific protein. Insect Biochem. 1990;20:421–427. [Google Scholar]

- Harmel N, Letocart E, Cherqui A, Giordanengo P, Mazzucchelli G, Guillonneau F, De Pauw E, Haubruge E, Francis F. Identification of aphid salivary proteins: a proteomic investigation of Myzus persicae. Insect Mol. Biol. 2008;17:165–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2008.00790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys NJ, Douglas AE. Partitioning of symbiotic bacteria between generations of insect: a quantitative study of a Buchnera sp in the pea aphid (Acyrthosiphon pisum) reared at different temperatures. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1997;63:3294–3296. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.8.3294-3296.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Z, Jones DH, Khuri S, Tsinoremas NF, Wyss T, Jander G, Wilson AC. Comparative analysis of genome sequences from four strains of the Buchnera aphidicola Mp endosymbion of the green peach aphid, Myzus persicae. BMC genomics. 2013;14:917. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JH, Jander G. Myzus persicae (green peach aphid) feeding on Arabidopsis induces the formation of a deterrent indole glucosinolate. Plant. J. 2007;49:1008–1019. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.03019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusnierczyk A, Winge P, Midelfart H, Armbruster WS, Rossiter JT, Bones AM. Transcriptional responses of Arabidopsis thaliana ecotypes with different glucosinolate profiles after attack by polyphagous Myzus persicae and oligophagous Brevicoryne brassicae. J. Exp. Bot. 2007;58:2537–2552. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusnierczyk A, Winge P, Jorstad TS, Troczynska J, Rossiter JT, Bones AM. Towards global understanding of plant defence against aphids - timing and dynamics of early Arabidopsis defence responses to cabbage aphid (Brevicoryne brassicae) attack. Plant Cell Environ. 2008;31:1097–1115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2008.01823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, Valentin F, Wallace IM, Wilm A, Lopez R, Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letunic I, Doerks T, Bork P. SMART 7: recent updates to the protein domain annotation resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D302–D305. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louis J, Singh V, Shah J. Arabidopsis thaliana-Aphid Interaction. The Arabidopsis Book. 2012;10:e0159. doi: 10.1199/tab.0159. 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez de Ilarduya O, Xie Q, Kaloshian I. Aphid-induced defense responses in Mi-1-mediated compatible and incompatible tomato interactions. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2003;16:699–708. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2003.16.8.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miki D, Shimamoto K. Simple RNAi vectors for stable and transient suppression of gene function in rice. Plant Cell Physiol. 2004;45:490–495. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pch048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles PW. Aphid saliva. Biol. Rev. 1999;74:41–85. [Google Scholar]

- Miller G, Schlauch K, Tam R, Cortes D, Torres MA, Shulaev V, Dangl JL, Mittler R. The plant NADPH oxidase RBOHD mediates rapid systemic signaling in response to diverse stimuli. Sci. Signal. 2009;2 doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran PJ, Thompson GA. Molecular responses to aphid feeding in Arabidopsis in relation to plant defense pathways. Plant Physiol. 2001;125:1074–1085. doi: 10.1104/pp.125.2.1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno A, Garzo E, Fernandez-Mata G, Kassem M, Aranda MA, Fereres A. Aphids secrete watery saliva into plant tissues from the onset of stylet penetration. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2011;139:145–153. [Google Scholar]

- Murashige T, Skoog FA. A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol. Plant. 1962;15:473–497. [Google Scholar]

- Mutti NS, Park Y, Reese JC, Reeck GR. RNAi knockdown of a salivary transcript leading to lethality in the pea aphid, Acyrthosiphon pisum. J. Insect Sci. 2006;6:1–7. doi: 10.1673/031.006.3801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutti NS, Louis J, Pappan LK, Pappan K, Begum K, Chen MS, Park Y, Dittmer N, Marshall J, Reese JC, Reeck GR. A protein from the salivary glands of the pea aphid, Acyrthosiphon pisum is essential in feeding on a host plant. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008;105:9965–9969. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708958105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson SJ, Hartson SD, Puterka GJ. Proteomic analysis of secreted saliva from Russian wheat aphid (Diuraphis noxia Kurd.) biotypes that differ in virulence to wheat. J. Proteomics. 2012;75:2252–2268. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2012.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfalz M, Vogel H, Kroymann J. The gene controlling the Indole Glucosinolate Modifier1 quantitative trait locus alters indole glucosinolate structures and aphid resistance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2009;21:985–999. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.063115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitino M, Hogenhout SA. Aphid protein effectors promote aphid colonization in a plant species-specific manner. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2013;26:130–139. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-07-12-0172-FI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitino M, Coleman AD, Maffei ME, Ridout CJ, Hogenhout SA. Silencing of aphid genes by dsRNA feeding from plants. PLoS One. 2011;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey JS, Wilson AC, de Vos M, Sun Q, Tamborindeguy C, Winfield A, Malloch G, Smith DM, Fenton B, Gray SM, Jander G. Genomic resources for Myzus persicae: EST sequencing, SNP identification, and microarray design. BMC genomics. 2007;8:423. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao SAK, Carolan JC, Wilkinson TL. Proteomic profiling of cereal aphid saliva reveals both ubiquitous and adaptive secreted proteins. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz J, Milpetz F, Bork P, Ponting CP. SMART, a simple modular architecture research tool: identification of signaling domains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998;95:5857–5864. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.5857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas CL, Leh V, Lederer C, Maule AJ. Turnip crinkle virus coat protein mediates suppression of RNA silencing in Nicotiana benthamiana. Virology. 2003;306:33–41. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(02)00018-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson GA, Goggin FL. Transcriptomics and functional genomics of plant defence induction by phloem-feeding insects. J. Exp. Bot. 2006;57:755–766. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erj135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjallingii WF. Salivary secretions by aphids interacting with proteins of phloem wound responses. J. Exp. Bot. 2006;57:739–745. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erj088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Heuvel JF, Verbeek M, van der Wilk F. Endosymbiotic bacteria associated with circulative transmission of potato leafroll virus by Myzus persicae. J. Gen. Virol. 1994;75(Pt 10):2559–2565. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-10-2559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Heuvel JF, Bruyere A, Hogenhout SA, Ziegler-Graff V, Brault V, Verbeek M, van der Wilk F, Richards K. The N-terminal region of the luteovirus readthrough domain determines virus binding to Buchnera GroEL and is essential for virus persistence in the aphid. J. Virol. 1997;71:7258–7265. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.10.7258-7265.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandermoten S, Harmel N, Mazzucchelli G, De Pauw E, Haubruge E, Francis F. Comparative analyses of salivary proteins from three aphid species. Insect Mol. Biol. 2014;23:67–77. doi: 10.1111/imb.12061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker GP, Medina-Ortega KJ. Penetration of faba bean sieve elements by pea aphid does not trigger forisome dispersal. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2012;144:326–335. [Google Scholar]

- Walling LL. Avoiding effective defenses: strategies employed by phloem-feeding insects. Plant Physiol. 2008;146:859–866. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.113142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Will T, Tjallingii WF, Thonnessen A, van Bel AJ. Molecular sabotage of plant defense by aphid saliva. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2007;104:10536–10541. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703535104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Will T, Steckbauer K, Hardt M, van Bel AJE. Aphid gel saliva: sheath structure, protein composition and secretory dependence on stylet-tip milieu. PLoS One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Will T, Kornemann SR, Furch ACU, Tjallingii WF, van Bel AJE. Aphid watery saliva counteracts sieve-tube occlusion: a universal phenomenon? J. Exp. Biol. 2009;212:3305–3312. doi: 10.1242/jeb.028514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Fig. 1. M. persicae salivary effector gene expression in planta. (A) Expression of Mp1, Mp57 and Mp58 through agroinfiltration in N. tabacum with and without their signal peptides, used for bioassays. (B) Expression of effector proteins through agroinfiltration in N. tabacum used for aphid bioassays. (C) Expression of effector proteins in multiple independent stable transgenic Col-0 lines used for bioassays. Driven by the 2x Cauliflower Mosaic Virus 35S promoter unless otherwise noted; AtSuc2, A. thaliana sucrose transporter; EV = empty vector control.

Supplementary Fig. 2. Visualization of MpC002 tagged with GFP. (A) Expression of MpC002 through agroinfiltration under the 2x Cauliflower Mosaic Virus 35S promoter, 2 days post infiltration, shows expression in the whole leaf. (B) Expression of MpC002 through agroinfiltration under the phloem-specific A. thaliana sucrose transporter, AtSuc2, shows expression in the vascular tissue.

Supplementary Fig. 3. Protein sequence alignment of Mp55 and its likely homolog in A. pisum. Alignment done in ClustalW2, with 53% sequence identity at the amino acid level; GenBank sequence IDs: A. pisum, LOC100569515; M. persicae, EC389393.1.