Abstract

Lingual mandibular bone defect, also known as Stafne bone cavity, is mostly seen in the posterior portion of the mandible. Cavities in the anterior region are very unusual, with around 50 cases reported in the English literature. They are often asymptomatic and found during routine radiographic examinations. This article describes a case of anterior Stafne bone cavity in a 56-year-old male patient.

Keywords: non-odontogenic cysts, cone beam CT, magnetic resonance imaging

Introduction

Stafne bone defects (SBDs) are asymptomatic bone lesions that were first described by Stafne who reported 35 cases.1 They are well-circumscribed ovoid radiolucent bone defects usually located lingually on the posterior mandible below the inferior alveolar canal. SBDs mostly affect men in their fifth or seventh decade of life. Their prevalence is reported to be between 0.10% and 0.48%.2,3 They usually contain ectopic salivary gland tissue and do not require treatment. They are sometimes referred to as idiopathic bone cavities, static bone defects or ectopic salivary glands.

The anterior variant of the lesion, which is described as a radiolucent, ellipsoid or ovoid concavity in the canine–pre-molar mandibular region, was first reported in 1957 by Richard and Ziskind.4 The clinical and radiographic properties of the anterior SBD are similar to the posterior variant. Posterior SBDs can be easily diagnosed because of their unique location on radiographs; however, the anterior variants may be misdiagnosed and confused with other pathological entities owing to their unusual locations.

The purpose of this article is to describe a new case of SBD in the anterior mandible with its clinical, radiographic and pathological features. The differential diagnosis and the treatment options are also discussed.

Case report

A 56-year-old male was referred to our clinic by his general dentist for consultation of a radiolucent lesion in the anterior mandible, which was discovered during a routine radiographic examination. The panoramic radiograph revealed an oval-shaped radiolucency just medial to the mental foramen with well-defined borders located beneath the apices of the left mandibular canine and pre-molars (Figure 1). The lesion was asymptomatic and appeared to have no relationship with the adjacent teeth that gave positive responses to the vitality tests. The patient's medical history was not significant. There were no abnormal findings in the oral examination of the patient. The lesion was aspirated, but no contents were obtained. The lack of aspirate suggested the presence of a soft tissue mass. To reveal the exact borders of the lesion, it was decided to perform a CBCT (I-CAT® FLX; Imaging Sciences International, Hatfield, PA). In axial cross sections, it can easily be seen that the radiolucency lies just beneath the apices of the right mandibular pre-molars leaving the apices intact. The lesion reached the medial side of the buccal cortex extending both mesially and distally. The lesion eroded the lingual cortical bone and caused a buccal expansion leaving a thin layer of bone. In three-dimensional remodelling, this thin layer of bone cannot be seen owing to the burn out effect causing a false image of a complete defect through the mandible (Figure 2). Because of the wide range of possible pathologies that can cause expansions such as ameloblastomas or keratocystic odontogenic tumour, considering the age, clinical and radiographic findings of the patient, surgical exploration and a biopsy were planned. SBD was excluded from the initial diagnosis because expansion is an unusual finding, which is interesting in this case. During the surgical intervention, a soft, firm pink mass was found (Figure 3). An incisional biopsy was taken from the site and was sent to the Pathology Department of Oncology Institute, Istanbul University, Istanbul, Turkey, for histopathological examination (Figure 4). The healing period was uneventful. The histopathological examination revealed the absence of any cystic lesion but rather the presence of a mixed salivary gland tissue consistent with normal sublingual gland (Figure 5).

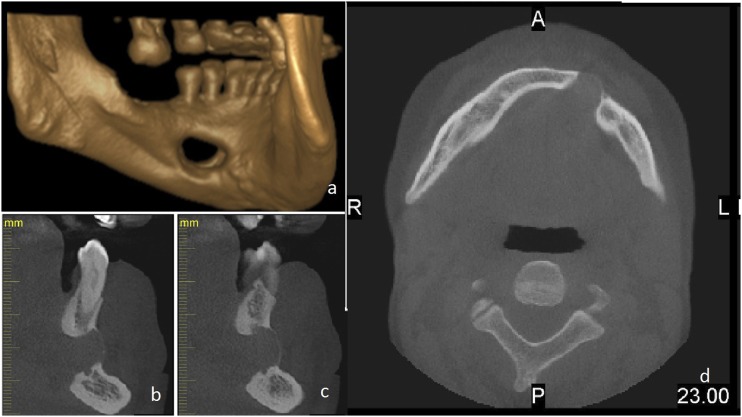

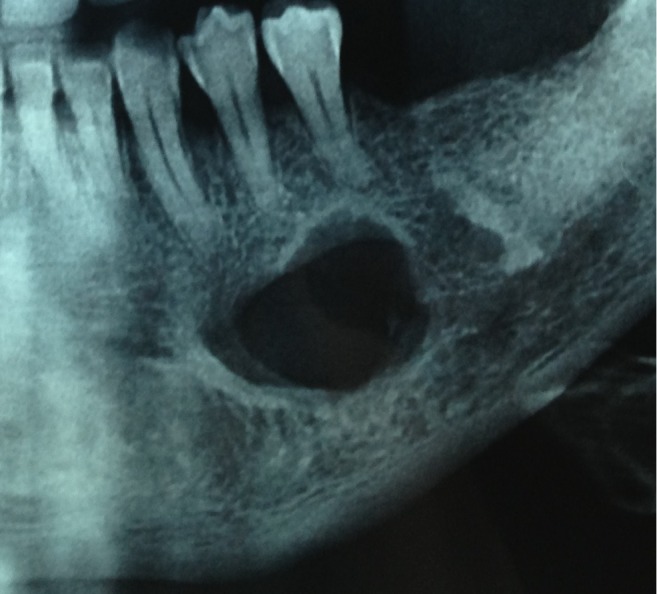

Figure 1.

Pre-operative panoramic radiograph showing a well-defined oval radiolucency just inferior to the pre-molar apices.

Figure 2.

Images taken from the CBCT examination. (a) Three-dimensional rendering of the mandible. The defect seems to have eroded the buccal cortex because of the burn out effect. (b, c) Cross-sectional images of the defect area showing the relationship of the inferior alveolar nerve and the apices of the teeth to the defect. (d) Axial image showing the buccal expansion caused by the defect. A, anterior; L, left; P, posterior; R, right.

Figure 3.

Intra-operative view showing the lobular soft tissue that is completely different from a cystic epithelium covering the whole radiolucency leaving the apices of the teeth intact.

Figure 4.

Biopsy specimen taken from the surgical site similar to the appearance of glandular tissue.

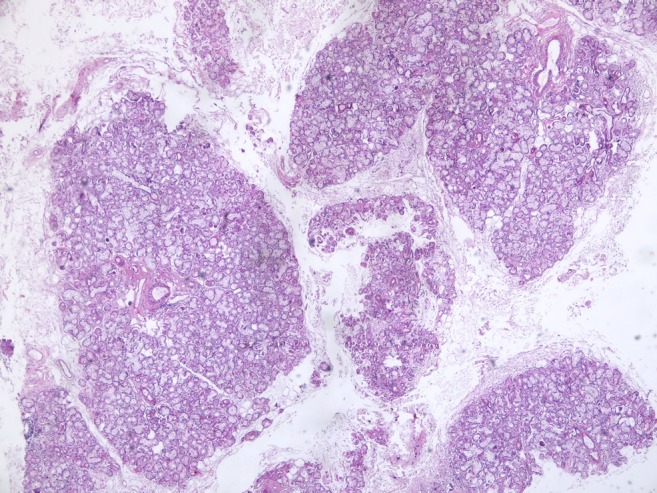

Figure 5.

Salivary gland acini, ducts and lobulus are seen within the loose connective tissue representing a normal gland (haematoxylin and eosin, ×40).

Discussion

SBDs in the posterior part of the mandible have typical location and radiographic properties, allowing an easy diagnosis. The lesion may sometimes interrupt the continuity of the inferior border of the mandible. Most lesions are asymptomatic, and, rarely, the lingual defect can be clinically palpated. It is also established that these lesions are non-progressive5 and sometimes may regress.6

Anterior SBDs are considered to be rare and in contrast to posterior variant of the lesion, they may be difficult to diagnose. They may be located between or below the roots. Sometimes, they may be seen superimposed over the roots or at the sites of previous extractions. Therefore, they may be misdiagnosed as other radiolucencies, such as various benign tumours, bone metastases or more frequently cysts (e.g. radicular, residual, lateral periodontal cyst, keratocystic odontogenic tumour).7–11 In atypical cases like ours, further investigation can be carried out by cross-sectional imaging (CBCT or MRI). Although CBCT is non-invasive and effective in the evaluation of bone borders, it does not allow the clinician to examine soft tissues in detail. On the other hand, MRI can offer much better resolutions when studying soft tissue. Therefore, preference is given to MRI. MRI has the advantages of multiple imaging planes and different echo sequences while not exposing the patient to ionizing radiation. Its major disadvantages are cost and field distortion artefacts from dental material. The diagnosis of Stafne bone cavity may be confirmed with a limited MR examination that shows the mandibular defect containing soft tissue continuous with, and isointense with, the submandibular gland on both T1 and T2 weighted sequences. The inherent soft-tissue contrast of MRI studies should be adequate to make the diagnosis of a Stafne bone cavity without the need for intravenous contrast material. Should contrast material be administered, the salivary gland contents of a Stafne bone cavity should enhance to the same degree as the adjacent submandibular gland.9,12,13 Sialography may also be considered owing to the salivary gland content of the lesion but its use in the anterior SBDs is limited because of the numerous ducts of Rivinus that are smaller in diameter therefore making the procedure harder to perform.14 Therefore, the use of different imaging techniques to aid in the final diagnosis of anterior Stafne defects without the need for invasive surgery would be beneficial.

The incidence of anterior Stafne bone cavity is often varied in the literature from 0.009% 15 to 0.300%.16–18 It is three times more common in males than in females. The highest incidence for males is in the fifth and seventh decades as in our case.19 Most of the cases are located between the cuspid and the first molar (65%), whereas fewer cases involve the incisor area (24%). Sometimes, the jaws might be affected bilaterally (11%).20

Radiographic attributes of the Stafne bone cavity are not always the same. Usually, they appear as circumscribed, unilocular radiolucencies; however, multilocular appearance can be seen. Borders of the lesion are often sclerotic but may also not be clearly defined.

Whether Stafne defect is a mandibular cavity completely surrounded by bone or a concavity more or less widely open on the lingual cortex above the level of the mylohyoid attachment is not always clear. In the majority of the cases reported, the cavity content was connected with the adjacent salivary gland, implicating a defect in the lingual cortex. This was the same for our case, however, the dental CBCT scan shows that the lesion had also caused a defect on buccal cortex of the mandible. This was one of the main reasons that led to our decision to perform a biopsy. Because the thinning and expansion of the buccal cortex is not generally associated with SBDs, the appearance of the lesion gave us the idea of a pathology that was more aggressive.

The pathogenesis of SBD is not clearly understood either. Most authors recognize the hypothesis that these cavities are congenital. Others think that they develop later in life through pressure resorption. The first theory, originally supported by Stafne1 and then by other authors,7,21,22 suggests that a portion of the salivary gland becomes entrapped during the development and ossification of the mandible. The major flaw in this theory is that these defects are much more frequently diagnosed in adults than in children, suggesting that the development of these defects probably occurs later in life.23 It appears that the local pressure applied by the sublingual or the submandibular gland could cause such lesions.21,24 Some authors support the idea that there is a compensatory hypertrophy related to a lymphocytic infiltration and reduced secretory efficiency, which increases with age, whereas others believe that there is an increase of salivary gland size as part of general somatic growth.22 None of these hypotheses has been proven. More recently, embryonic rests of salivary gland tissue have been found in jawbone samples, which might explain the rare SBDs in which an intact thin lingual cortex is present, separating the lesion from the adjacent salivary gland.25

Unlike the posterior variant, the anterior Stafne bone cavity may be a diagnostic challenge. The absence of guiding anatomic locations such as the inferior alveolar canal and the relation of the lesion with the adjacent teeth make it easier to confuse the bone cavity with other pathologies. If the bone cavity is related to the root apices, it can mimic an inflammatory cyst. The presence of caries and changes in the lamina dura of the teeth adjacent to the lesion might give the clinician clues regarding the diagnosis. To avoid an unnecessary endodontic treatment, a pulp vitality test should be performed.13,19,20,26 A residual cyst that develops after the incomplete removal of an inflammatory cyst may mimic SBDs if the lesion is in an edentulous area. Residual cysts tend to expand, displace teeth and cause resorption in the bone unlike SBDs. Keratocystic odontogenic tumours can also appear as unilocular radiolucent lesions with smooth corticated borders. However, they are often associated with impacted teeth. Keratocystic odontogenic tumour are likely to grow more aggressively than other odontogenic cysts and cause cortical thinning and root resorption. Our case also had cortical thinning on both sides of the mandible. However these cysts often provide cystic fluid when an aspiration biopsy is performed. This aspect might be helpful in the differential diagnosis. Ameloblastomas on the other hand may not contain any fluid when punctured and could be hard to distinguish from SBDs. The radiographic appearance of ameloblastomas may vary from well-defined unilocular to multilocular radiolucencies. The unicystic type may mimic SBD. However, ameloblastomas are likely to cause tooth displacement/resorption and expansion of the jaws, which are uncommon for SBDs.

Odontogenic myxomas are benign, intraosseous neoplasms originating from the mesenchymal tissue. They are usually multilocular but small lesions may be unilocularly similar to SBDs; however, radiographically, they can be differentiated by a scalloped appearance between the roots and displacement with resorption of the teeth.

Immature lesions of ossifying fibroma, cemental dysplasia and florid osseous dysplasia in the first stages of development may appear radiolucent and can mimic SBDs; however, if left untreated over time, they will generally exhibit increasingly radio-opaque foci. Simple bone cysts may also be included in the differential diagnosis. These pseudocysts may appear to be oval shaped or scalloped between the roots of the teeth. Aspiration biopsy of these lesions would include a bloody content, which is helpful to diagnose the lesion.

Other lesions that can mimic SBDs are benign neurogenic tumours such as neurofibroma, arteriovenous fistulas, giant cell granulomas, brown tumours, eosinophilic granulomas, central haemangiomas and multiple myeloma.

In conclusion, no treatment is necessary for SBDs, both the posterior and the anterior variants. Surgical exploration and biopsy should be performed only to rule out other pathological entities in atypical cases when the diagnosis is not certain or there are clinical symptoms present.

References

- 1.Stafne EC. Bone cavities situated near the angle of the mandible. J Am Dent Assoc 1942; 29: 1969–72. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Layne EL, Morgan AF, Morton THJr. Anterior lingual mandibular bone concavity: report of case. J Oral Surg 1981; 39: 599–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ström C, Fjellström CA. An unusual case of lingual mandibular depression. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1987; 64: 159–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richard EL, Ziskind J. Aberrant salivary gland tissue in mandible. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1957; 10: 1086–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bergenholtz A, Persson G. Idiopathic bone cavities. A report of four cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1963; 16: 703–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shibata H, Yoshizawa N, Shibata T. Developmental lingual bone defect of the mandible. Report of a case. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1991; 20: 328–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salman L, Chaudhry AP. Malposed sublingual gland in the anterior mandible: a variant of Stafne's idiopathic bone cavity. Compendium 1991; 12: 42–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Apruzzese D, Longoni S. Stafne cyst in an anterior location. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1999; 57: 333–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anneroth G, Berglund G, Kahnberg KE. Intraosseous salivary gland tissue of the mandible mimicking a periapical lesion. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1990; 19: 74–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Childers EL, Johnson JD, Warnock GR, Kratochvil FJ. Asymptomatic periapical radiolucent lesion found in an area of previous trauma. J Am Dent Assoc 1990; 121: 759–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barak S, Katz J, Mintz S. Anterior lingual mandibular salivary gland defect—a dilemma in diagnosis. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1993; 31: 318–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grellner TJ, Frost DE, Brannon RB. Lingual mandibular bone defect: report of three cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1990; 48: 288–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katz J, Chaushu G, Rotstein I. Stafne's bone cavity in the anterior mandible: a possible diagnostic challenge. J Endod 2001; 27: 304–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Araiche M, Brode H. Aberrant salivary gland tissue in mandible. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1959; 12: 727–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Philipsen HP, Takata T, Reichart PA, Sato S, Suei Y. Lingual and buccal mandibular bone depressions: a review based on 583 cases from a world-wide literature survey, including 69 new cases from Japan. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2002; 31: 281–90. doi: 10.1038/sj.dmfr.4600718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith MH, Brooks SL, Eldevik OP, Helman JI. Anterior mandibular lingual salivary gland defect: a report of a case diagnosed with cone-beam computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2007; 103: e71–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.11.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Queiroz LM, Rocha RS, de Medeiros KB, da Silveira EJ, Lins RD. Anterior bilateral presentation of Stafne defect: an unusual case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2004; 62: 613–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Langlais RP, Cottone J, Kasle MJ. Anterior and posterior lingual depressions of the mandible. J Oral Surg 1976; 34: 502–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Courten A, Küffer R, Samson J, Lombardi T. Anterior lingual mandibular salivary gland defect (Stafne defect) presenting as a residual cyst. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2002; 94: 460–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silva PH, Sindermann DB, Rondanelli BM. Giant mandibular bone defect: report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2006; 64: 145–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choukas NC, Toto PD. Etiology of static bone defects of the mandible. J Oral Surg Anesth Hosp Dent Serv 1960; 18: 16–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seward GR. Salivary gland inclusions in the mandible. Braz Dent J 1960; 108: 321–5. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sandy JR, Williams DM. Anterior salivary gland inclusion in the mandible: pathological entity or anatomical variant?. Br J Oral Surg 1981; 19: 223–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dereci O, Duran S. Intraorally exposed anterior Stafne bone defect: a case report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2012; 113: e1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2011.07.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bouquot JE, Gnepp DR, Dardick I, Hietanen JH. Intraosseous salivary tissue: jawbone examples of choristomas, hamartomas, embryonic rests, and inflammatory entrapment: another histogenetic source for intraosseous adenocarcinoma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2000; 90: 205–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Turkoglu K, Orhan K. Stafne bone cavity in the anterior mandible. J Craniofac Surg 2010; 21: 1769–75. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3181f40347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]