Abstract

Background

Vitamin D is produced in the skin after sun-light exposure and can also be obtained through food. Vitamin D deficiency has recently been linked with a range of diseases including chronic pain. Observational and circumstantial evidence suggests that there may be a role for vitamin D deficiency in the aetiology of chronic pain conditions.

Objectives

To assess the efficacy and adverse events of vitamin D supplementation in chronic painful conditions.

Search methods

We searched Cochrane CENTRAL, MEDLINE, EMBASE and the Oxford Pain Relief Database for studies to September 2009. This was supplemented by searching the reference lists of retrieved articles, textbooks and reviews.

Selection criteria

Studies were included if they were randomised double blind trials of vitamin D supplementation compared with placebo or with active comparators for the treatment of chronic pain conditions in adults.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently selected the studies for inclusion, assessed methodological quality, and extracted data. Pooled analysis was not undertaken due to paucity and heterogeneity of data.

Main results

Four studies, with a total of 294 participants, were included. The studies were heterogeneous with regard to study quality, the chronic painful conditions that were investigated, and the outcome measures reported. Only one study reported a beneficial effect, the others found no benefit of vitamin D over placebo in treating chronic pain.

Authors’ conclusions

The evidence base for the use of vitamin D for chronic pain in adults is poor at present. This is due to low quality and insufficient randomised controlled trials in this area of research.

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH): Arthritis, Rheumatoid [drug therapy]; Chronic Disease; Ergocalciferols [adverse effects; therapeutic use]; Hydroxycholecalciferols [adverse effects; therapeutic use]; Pain [*drug therapy; etiology]; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Vitamin D [adverse effects; *therapeutic use]; Vitamin D Deficiency [complications; drug therapy]; Vitamins [adverse effects; *therapeutic use]

MeSH check words: Adult, Humans

BACKGROUND

Vitamin D is a fat-soluble vitamin that is synthesized from a precursor in the skin after exposure to ultraviolet B (UVB) radiation from the sun, and it is also obtained from dietary sources (e.g. oily fish, vitamin D-fortified milk and breakfast cereals, or dietary supplements). Vitamin D can be of plant origin (vitamin D2 or ergocalciferol) or of animal origin (vitamin D3 or cholecalciferol). Vitamin D from the skin and diet is metabolized in the liver to 25-hydroxy vitamin D, and further metabolized in the kidneys to its active form, 1,25-dihydroxy-vitamin D. Vitamin D exerts its effects by modulating gene expression after binding to a nuclear vitamin D receptor. Most tissues in the human body express vitamin D receptors (Holick 2007) supporting the concept of a wide-ranging importance of vitamin D.

Vitamin D deficiency can arise from a number of causes including insufficient UVB exposure, decreased bioavailability (e.g. malabsorption disorders), or diseases that affect the metabolism of vitamin D, such as liver and kidney disease. Some medications can also cause vitamin D deficiency. These include anticonvulsants, glucocorticoids, and antiretroviral drugs (Holick 2007).

Vitamin D is known to be implicated in diseases of the musculoskeletal system, where its deficiency is classically a cause of rickets (in children) and osteomalacia (‘softening of the bones’, in adults). Recently insufficient vitamin D has been implicated in a range of diseases involving other body systems, including disorders such as metabolic, autoimmune, psychiatric and cardiovascular disease, cancers (especially colon, prostate, and breast cancer), and chronic pain (Holick 2007). It has been suggested that there is widespread vitamin D deficiency in the population and that sensible sun exposure and vitamin D supplementation may be called for (Holick 2007). Indeed, a recent meta-analysis found a reduced all-cause-mortality (death rate from any cause) with vitamin D supplementation (Autier 2007). Recommended levels of vitamin D intake vary from 200 international units (IU) to 1000 IU per day (Holick 2007). One IU corresponds to 25 ng of vitamin D.

Description of the condition

Chronic pain is generally described as pain experienced on most days for at least three months. Chronic pain in its various forms is very common, one of the most common health problems of all. The prevalence of benign chronic back pain in adults alone has been estimated to be between 2% and 40%, depending on the population studied (Verhaak 1998). The prevalence of arthritis was estimated at almost 16% in a large multinational study (Alonso 2004). Fibromyalgia is another chronic pain disorder that affects 1 to 2% of the population (Bannwarth 2009; Mas 2008; McQuay 2007). Furthermore, acute pain can become chronic. For example, a systematic review showed that chronic pain after surgery was surprisingly common, up to 47% after thoracic surgery (Perkins 2000). A survey of adults from Scotland found that about half of them self-reported chronic pain (Elliott 1999). Not surprisingly, chronic pain conditions can have a profound effect on functioning and quality of life (Alonso 2004; Mas 2008), with considerable economic and social impact. Chronic pain is a very common cause of sickness absence from work (Saastamoinen 2009).

There is some controversy among the experts as to which levels of 25-hydroxy vitamin D actually constitute deficiency (Holick 2007), but low levels of 25-hydroxy vitamin D have been linked with a higher incidence of chronic pain (Atherton 2009; Benson 2006; Lotfi 2007). Additionally, associations of such diverse types of pain as headache, abdominal pain, knee pain, and back pain with season of the year and latitude may be taken as evidence to suggest that 25-hydroxy vitamin D levels are important in this context (Mitsikostas 1996; Saps 2008; Zeng 2004). It seems possible, therefore, that vitamin D deficiency is involved in the aetiology of chronic pain.

Description of the intervention

Vitamin D supplementation can be given orally or parenterally. A number of different preparations and dosing regimens of vitamin D treatment have been employed in clinical practice. This review will consider all vitamin D preparations or dosing regimens when used in the treatment of chronic pain. Treatment with vitamin D holds great appeal because it is cheap, has relatively few, and usually mild, side effects, and there is a positive public perception of vitamin supplementation which could result in high rates of adherence. Excessive vitamin D intake can result in hypercalcaemia, but this is rare.

How the intervention might work

Vitamin D supplementation increases 25-hydroxy vitamin D blood levels (Holick 2007) (25-hydroxy vitamin D is the form of the vitamin usually measured, with assays normally detecting vitamin D2 and vitamin D3) and can therefore potentially correct the effects of vitamin D deficiency. The details of how this might work (molecular mechanism, time to effect, extent of reversibility of pain associated with vitamin D deficiency) are unclear at present.

Why it is important to do this review

While low levels of 25-hydroxy vitamin D have been linked with chronic pain conditions, no systematic review of vitamin D supplementation in chronic pain has been published in The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. A systematic review of vitamin D treatment for chronic pain is necessary to answer the questions of whether chronic pain can be helped by vitamin D supplementation and, indirectly, whether low levels of 25-hydroxy vitamin D in people with chronic pain are causal or coincidental. Our earlier review on this topic was published in “Pain”. This was based on a MEDLINE (PubMed) search and used evidence from a variety of study architectures (Straube 2009). We felt it was important to develop this further by using a more extensive search strategy and at the same time more stringent inclusion criteria to focus on the high quality evidence that is most relevant to clinical practice and present such a review in The Cochrane Library.

OBJECTIVES

To assess the efficacy and adverse events of vitamin D supplementation in chronic pain conditions when tested against placebo or against active comparators.

METHODS

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Studies were included if they were randomised double blind controlled trials of vitamin D supplementation compared with placebo or with active interventions in the treatment of chronic pain conditions. Randomisation and double blinding are known to minimise bias (Moore 2006). Parallel group design and cross-over studies were both acceptable.

We excluded the following:

review articles, case series, case reports and clinical observations;

studies of experimentally induced pain;

studies where pain relief (or pain intensity with baseline level) was not measured or not patient-reported.

Types of participants

Studies of adult participants (> 15 years) with all types of chronic pain conditions were eligible for inclusion. To qualify for inclusion, all study participants needed to have a chronic painful condition. Studies in conditions that were painful in some but could be asymptomatic in others (e.g. osteoporosis) did not qualify for inclusion if they did not explicitly state that all study participants had chronic pain.

Types of interventions

Vitamin D supplementation (oral or parenteral) compared with placebo or active comparator. No restriction was made regarding type, dose and frequency of vitamin D treatment. Studies that investigated combined treatment with vitamin D and other concurrent interventions were included only if the other interventions were available to the comparator group also, because we wanted to isolate the treatment effect due to vitamin D.

Types of outcome measures

We collected data on participant characteristics (age, sex, and condition to be treated, baseline 25-hydroxy vitamin D status) together with the following:

patient reported pain intensity or pain relief;

patient reported global impression of change;

patient reported “improvement ” in pain;

patient reported quality of life;

adverse events;

withdrawals.

Because different painful conditions may respond to vitamin D after different time periods (Leavitt 2008), we extracted outcome measures at different time points. We also collected data on baseline and end of trial 25-hydroxy vitamin D levels where they were reported.

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome was clinically significant pain relief. The following hierarchy of outcome measures, in order of preference, was used:

number of participants with at least 50% pain relief;

number of participants reporting a global impression of change of “much” or “very much” improvement;

number of participants with undefined “improvement” in pain.

Secondary outcomes

We investigated these secondary outcomes:

other patient-rated pain outcomes (reported as dichotomous responder outcomes or group mean values);

numbers of participants with adverse events: any adverse event, serious adverse events;

numbers of withdrawals: all cause, lack of efficacy, and adverse event withdrawals;

number of participants reporting improvement in quality of life (any scale).

Search methods for identification of studies

Studies were identified primarily by searching electronic databases, with no language restriction.

Electronic searches

The following electronic databases were searched. We searched as far back as databases allowed us, without specified start dates.

Cochrane CENTRAL (Issue 3, 2009);

MEDLINE (to September 2009);

EMBASE (to September 2009);

Oxford Pain Relief Database (Jadad 1996a).

See Appendix 1 for the MEDLINE search strategy, Appendix 2 for the EMBASE search strategy and Appendix 3 for the CENTRAL search strategy.

Searching other resources

Additional studies were sought from the reference lists of retrieved articles, textbooks and reviews. Manufacturers of vitamin D preparations were not contacted since vitamin D does not have an indication in chronic pain.

Data collection and analysis

Review authors were not blinded to the authors’ names and institutions, journal of publication, or study results at any stage of the review. Two review authors independently selected the studies for inclusion, assessed methodological quality, and extracted data. Disagreements were resolved through discussion with a third review author.

Selection of studies

Titles and abstracts of publications identified by the searches were assessed on screen to eliminate studies that obviously did not satisfy the inclusion criteria. Full publications of the remaining studies were obtained to determine inclusion in the review.

Data extraction and management

A standard form was used for data extraction.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed the included studies for quality using a five-point scale (Jadad 1996b) that considered randomisation, blinding, study withdrawals and dropouts. Studies needed to score at least two points, one for randomisation and one for blinding to be included in the review, i.e. studies needed to be randomised and double blind. Trial validity was assessed using a 16-point scale (Smith 2000) and a Risk of bias table was completed using the criteria of sequence generation, allocation concealment and blinding.

Measures of treatment effect

It was planned to estimate treatment effect for dichotomous outcomes by calculating relative benefit or harm, and numbers-needed-to-treat-to-benefit (NNT) or -harm (NNH). Any continuous outcome data would be analysed using RevMan 5.

Unit of analysis issues

Randomisation was to the individual patient.

Dealing with missing data

Analysis was conducted according to the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle.

Assessment of heterogeneity

It was planned to examine homogeneity of studies with regard to intervention effects visually using L’Abbé plots (L’Abbé 1987).

Assessment of reporting biases

Reporting biases were not formally assessed.

Data synthesis

It was planned to pool either dichotomous and continuous data where the same or comparable measures were used. Data for ‘at least 50% pain relief’ would be combined even when pain was assessed with different scales whenever the assessments in themselves were valid.

For dichotomous outcomes, relative benefit (RB) and risk (RR) estimates would be calculated with 95% confidence intervals (CI) using a fixed-effect model (Morris 1995). A statistically significant benefit of active treatment over control would be assumed when the lower limit of the 95% CI of the RB was greater than the number one. A statistically significant benefit of control over active treatment was assumed when the upper limit of the 95% CI was less than the number one. NNT or NNH and 95% CI would be calculated from the pooled number of events using the method devised by Cook and Sackett (Cook 1995).

Continuous data suitable for pooling would be analysed using RevMan 5 software.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Subgroup analyses were planned for different pain conditions.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses were planned for different treatment regimens and for participants with different baseline levels of 25-hydroxy vitamin D (the effects of vitamin D treatment might differ in people who are deficient in 25-hydroxy vitamin D versus those who have ‘normal’ levels).

RESULTS

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies.

Results of the search

Searching identified 15 potentially relevant studies that were examined for inclusion.

Included studies

Four studies were included (Brohult 1973; Di Munno 1989; Warner 2008; Yamauchi 1989) with a total of 294 participants. Full details are in the “Characteristics of included studies” table.

Excluded studies

Eleven potentially relevant studies (Arden 2006; Björkman 2008; de Nijs 2006; Dottori 1982; Grove 1981; Krocker 2008; Lyritis 1994; Ringe 2000; Ringe 2004; Ringe 2005; Ringe 2007) had to be excluded largely for reasons of methodological inadequacy (not double blind) or because it was not clear that all participants had a chronic painful condition. Full details are in the “Characteristics of excluded studies” table.

Risk of bias in included studies

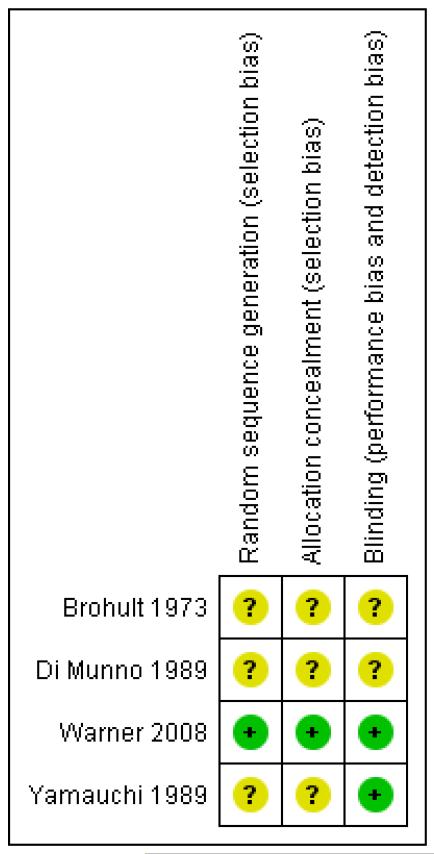

One recent study (Warner 2008) was of high methodological quality (Oxford Quality Score 5/5) suggesting little likelihood of methodological bias. Three older studies (Brohult 1973; Di Munno 1989; Yamauchi 1989) had lower Oxford Quality Scores and were potentially prone to bias. Points were lost mainly due to failure to adequately describe methods of randomisation and blinding. Studies scored between 9/16 and 16/16 on the Oxford Pain Validity Scale, indicating moderate to good validity. Points were lost due to inadequate details of study methods and because of small trial group sizes.

Full details are in the table of “Characteristics of included studies” and Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Methodological quality summary: review authors’ judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Effects of interventions

Four studies could be included (Brohult 1973; Di Munno 1989; Warner 2008; Yamauchi 1989) with a total of 294 participants. These studies investigated the effects of four different regimens of vitamin D administration, in participants with three different chronic pain conditions, from four different countries, were conducted at different times, and reported on different outcomes. The studies were therefore not sufficiently homogeneous to allow any meaningful pooled analysis.

Only one of the included studies investigated one of the primary efficacy outcomes that were selected as representing clinically significant benefit. A trial of alfacalcidol (1-hydroxycholecalciferol) for rheumatoid arthritis over 16 weeks (Yamauchi 1989) found that similar proportions of participants reported “very much” or “much” improvement in patient global impression of change in the two treatment groups (1-2 μg alfacalcidol) and in the placebo group.

In a trial of 100,000 IU daily calciferol for rheumatoid arthritis conducted over 12 months, Brohult 1973 showed that the consumption of analgesics and antiinflammatory medicines decreased significantly in the calciferol group while there was no change in the placebo group (no direct between groups comparison was reported). A trial of 25-hydroxy vitamin D (35 μg per day for 25 days a month) in participants with polymyalgia rheumatica over 9 months (Di Munno 1989) found that subjective pain on movement decreased in both vitamin D and placebo groups over time, with little difference between the groups (no statistics for between group comparisons reported). A recent study of 50,000 IU ergocalciferol for the treatment of diffuse musculoskeletal pain over 3 months (Warner 2008) investigated pain with a visual analogue scale (VAS) - finding no significant difference between vitamin D and placebo groups - and with a functional pain score - with an outcome that slightly favoured placebo in one comparison (Table 1).

Table 1. Summary of outcomes: efficacy.

| Study ID | Intervention | Baseline vit D 25-(OH)D ng/ml | End of trial vit D 25-(OH)D ng/ml | ≥50% pain relief | PGIC improvement | Any “improvement” | Other pain outcomes | QoL Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brohult 1973 |

|

no data | no data | no data | no data | no data | Consumption of “analgesics and antiinflammatory medicines” decreased significantly in calciferol group (P < 0.01), no change in control group (no direct between groups comparison reported) | no data |

| Di Munno 1989 |

All had 500 mg calcium and 6-methylprednisolone |

no data | no data | no data | no data | no data | Subjective pain on movement (scale 0-4): significantly decreased in both groups over time, no great difference between groups (no statistics for between groups comparison reported) | no data |

| Yamauchi 1989 |

|

no data | no data | no data |

|

no data | no data | no data |

| Warner 2008 |

|

|

(P<0.001) |

no data | no data | no data | Visual analogue scale: no significant difference between groups; functional pain score: slightly favours placebo (P = 0.05) | no data |

PGIC - patient global impression of change; QoL - quality of life

Yamauchi 1989 included 191 participants in total (65, 64, and 62 in the placebo, 1 μg, and 2 μg alphacalcidol groups, respectively). Of these, 20 (8, 5, and 7 in the previously mentioned groups) were excluded after randomisation due to violation of inclusion criteria or concurrent drugs. These 20 participants who were excluded from the original study due to protocol violation were not included in our intention to treat analysis.

Warner 2008 measured 25-hydroxy vitamin D levels in treatment and placebo groups at the start and end of the trial (the only study to do so). While at baseline there was no significant difference in 25-hydroxy vitamin D levels between groups, after three months of ergocalciferol treatment the levels in the active treatment group were significantly higher than in the placebo group (Table 1).

Two studies, with a total of 195 participants, reported on adverse events in a way that allowed data extraction (numbers of participants with any adverse events or serious adverse events). Adverse events were infrequent and occurred at similar rates with vitamin D and placebo (Di Munno 1989; Yamauchi 1989; Table 2).

Table 2. Summary of outcomes: adverse events and withdrawals.

| Study ID | Intervention | AnyAE | Serious AE | All cause withdrawal | LoE withdrawal | AE withdrawal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brohult 1973 |

|

no data | no data |

|

Worsening of disease:

|

Death:

|

| Di Munno 1989 |

All had 500 mg calcium and 6-methylprednisolone |

|

|

no data | no data | no data |

| Yamauchi 1989 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Warner 2008 |

|

no data | no data |

|

no data |

|

AE - adverse event; LoE - lack of efficacy; PE - pulmonary embolus

Yamauchi 1989 reported that there were two participants with adverse events in the placebo groups. However, because there were three adverse event withdrawals in those group the number of participants with adverse events is given as three in the above table.

Brohult 1973 reported that after 10 months of treatment one participant in the calciferol group had a serum calcium level (7.0 mEq/l) that exceeded the upper limit of the normal range, and that two participants in the calciferol group reported polydipsia and increased frequency of urination on one occasion (these can be symptoms of hypercalcaemia, but they are not specific for it). None of the other trials reported on hypercalcaemia as an adverse event.

Withdrawals were investigated in three studies with a total of 270 participants. There were similar rates of withdrawals in the vitamin D and placebo groups. Brohult 1973 reported that four out of 24 participants withdrew in the calciferol group (three due to worsening of disease, one death due to a pulmonary embolus) versus six out of 25 in the placebo group (all due to worsening of disease). Yamauchi 1989 found that 8/57 participants withdrew in the placebo group, 14/59 in the 1 μg alfacalcidol group, and 9/55 in the 2 μg alfacalcidol group. Of these, only one withdrawal was due to lack of efficacy (1 μg alfacalcidol group); adverse event withdrawals included three cases in the placebo group, one case in the 1 μg alfacalcidol group and two cases in the 2 μg alfacalcidol group. Warner 2008 stated that three out of 25 participants withdrew in the vitamin D group versus five out of 25 in the placebo group; there were no adverse event withdrawals in either group (Table 2).

No study reported on the number of participants with improvements in quality of life.

DISCUSSION

Summary of main results

On the basis of four heterogeneous studies there is at present no convincing evidence that vitamin D treatment is beneficial in chronic painful conditions in adults. Only one of the studies reported on one of the primary outcomes that this review was looking for, finding similar results with vitamin D and placebo. These primary outcomes were based on a recent description of clinically useful benefit (Dworkin 2008). With one exception (Yamauchi 1989) the studies reported only group means, rather than dichotomous responder outcomes (such as the proportions of participants achieving a certain defined level of pain intensity or pain relief). Relying on group mean values for pain intensity or pain relief is problematic because the underlying distributions are often skewed, and using average data from such skewed distributions can produce misleading results (McQuay 1996). This is why dichotomous responder analysis has been suggested to produce results more useful in clinical practice both in the acute (Moore 1998) and chronic pain setting (Moore 2008).

The only study that reported a beneficial effect (in a secondary pain outcome and not reporting dichotomous responder outcomes) was of lower methodological quality (Brohult 1973). The three other studies found no benefit of vitamin D over placebo (Di Munno 1989; Warner 2008; Yamauchi 1989).

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

A number of potentially eligible studies had severe methodological limitations and had to be excluded from this review. Of the four studies that could be included, three were of lower methodological quality (Brohult 1973; Di Munno 1989; Yamauchi 1989) and therefore potentially prone to bias. Only one studies investigated one of the primary pain outcomes that were chosen for clinical relevance and applicability (Yamauchi 1989). Furthermore, the clinical heterogeneity between studies made a meaningful pooled analysis impossible.

Quality of the evidence

The paucity of trials and participants in stringent studies, together with the laxness and inadequacy of outcome measures used, implies that the evidence base for the use of vitamin D in chronic painful conditions is weak.

Potential biases in the review process

Because of adherence to quality criteria and an extensive search strategy, bias in the review process were minimised.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

This study agrees with a previous review on the subject in that there is little high quality evidence for an effect of vitamin D in chronic pain, despite the existence of a number of studies of lower methodological quality (not double blind randomised controlled trials (RCTs)) that suggest an effect (Straube 2009). As we have previously stated, there is a ‘beguiling attraction’ in a link between low 25-hydroxy vitamin D levels and chronic pain (Straube 2009). If effective, vitamin D would be a simple and inexpensive treatment with limited side effects. Good evidence for this effectiveness is lacking, however. There are a number of examples where early observational studies and treatment studies of lower methodological quality appear to demonstrate effects that are not subsequently confirmed by high quality trials. For example, the use of hyperbaric oxygen in multiple sclerosis appeared beneficial based on observational and non-randomised studies, but subsequent RCTs found no benefit (Bennett 2001). Likewise for the use of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for postoperative pain, non-randomised trials were largely positive while randomised trials were largely negative (Carroll 1996). Our previous review on vitamin D for chronic pain came to a similar conclusion when comparing high and low quality treatment studies (Straube 2009). This present review - relying on a wider search and more strict inclusion criteria than our previous review - found few trials of a methodological quality sufficient for inclusion and with one exception these did not report on the most informative outcomes.

AUTHORS’ CONCLUSIONS

Implications for practice

At present, the evidence base for the use of vitamin D supplementation for chronic painful conditions in adults is rather poor and we do not think the evidence is of sufficient quality to guide clinical practice.

Implications for research

There is clearly a need for more work in this area. An effect of vitamin D on chronic pain is theoretically possible, even in the absence of a clear mode of action, because of the wide range of effects of vitamin D (Holick 2007) and the many molecular and neural mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis of various chronic pain conditions. While there is little evidence from double blind RCTs, other study types do suggest that there may be a link (Straube 2009). Because vitamin D is cheap and relatively safe, a use in chronic pain could be advocated even if the benefit was of modest size.

More and better evidence is called for. What is needed are large, double blind, RCTs in a variety of chronic pain conditions conducted over long enough periods of time with multiple assessments to capture short, medium, and long term effects. To provide the highest quality evidence, these trials need to be stratified by baseline 25-hydroxy vitamin D levels, with defined treatments, with clinically relevant pain outcomes (such as the primary outcomes that this review looked for), and ideally with outcomes analysed by post-treatment 25-hydroxy vitamin D level. Because it is unclear whether vitamin D has an effect at all, trials need to include a placebo group; and because it is unclear which dose of vitamin D - if any - is effective, different treatment regimens need to be compared. Finally, trials need to report on adverse events (including hypercalcaemia) and give details of withdrawals and drop-outs (all cause, lack of efficacy, and adverse event withdrawals), as is now commonly done in the pain field.

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY.

Vitamin D for the treatment of chronic painful conditions in adults

Vitamin D has a variety of roles in the body. It is made in the skin through the action of sunlight and can also be obtained from food. A lack of vitamin D has been implicated in a number of diseases, including chronic painful conditions. Additionally, associations of such diverse types of pain as headache, abdominal pain, knee pain, and back pain with season of the year and latitude provide indirect support for a role for vitamin D. The possibility of a link between vitamin D and chronic pain has attracted interest because - if it was true - vitamin D would be a cheap and relatively safe treatment for chronic pain. There is some evidence supporting this link but it is not of high quality and is at risk of bias. This review sought out high quality evidence from Randomised Controlled Trials on the treatment of chronic pain with vitamin D. There were few high quality studies of which only one reported a beneficial effect. At present, therefore, there is insufficient evidence for an effect of vitamin D in chronic pain conditions. More research is needed to determine if vitamin D is a useful pain treatment at all and if so, whether the effect is restricted to those who are vitamin D deficient, how much vitamin D is useful, in which conditions, and for how long.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Pain Research is supported in part by the Oxford Pain Research Trust, which had no role in design, planning, execution of the study, or in writing the manuscript. RAM is funded by NIHR Biomedical Research Centre Programme. We thank Mari Imamura for translating a paper from Japanese (Yamauchi 1989).

SOURCES OF SUPPORT

Internal sources

Oxford Pain Research Funds, UK.

External sources

NHS Cochrane Collaboration Grant, UK.

NIHR Biomedical Research Centre Programme, UK.

CHARACTERISTICS OF STUDIES

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, placebo controlled trial. Trial duration: 12 months | |

| Participants | Participants (n = 49) with rheumatoid arthritis of at least two years’ duration (average duration of disease 7 years). Mean age 52 years (range 18 to 69 years), 68% female | |

| Interventions | 100 000 IU calciferol (no more details given) per day (n = 24) Placebo (n = 25) |

|

| Outcomes | Consumption of analgesics and antiinflammatory medicines, all cause withdrawals, and other outcomes | |

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, D1, W1 = 3/5 Oxford Pain Validity Score: 11/16 |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Stated to be randomised. One of the authors chose whether participants received placebo or active treatment, but it is not stated by which method |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | One of the authors chose whether patients received placebo or active treatment (though it is not stated how) and was therefore possibly aware of the allocation. However, the authors arrived at their assessments independently and the other author’s opinion (not aware of allocation or blood calcium data) was adopted in case of disagreement |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Stated to be double blind. One of the authors was blinded but the other was possibly aware of treatment allocation |

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, placebo controlled trial. Trial duration: 9 months | |

| Participants | Participants (N = 24) with polymyalgia rheumatica of recent onset receiving 6-methol-prednisolone. Mean age 67.9 years (range 51 to 82 years), 63% female | |

| Interventions | 35 micrograms 25-OH vitamin D3/day for 25 days per month (n = 12) Placebo (n = 12) All participants received 500 mg calcium/day |

|

| Outcomes | Pain on movement, number with adverse events, and other outcomes | |

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, D1, W0 = 2/5 Oxford Pain Validity Score: 9/16 |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Stated to be randomised |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Stated to be double blind |

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, placebo controlled trial. Trial duration 3 months | |

| Participants | Participants (n = 50) with diffuse musculoskeletal pain and 25-OH vitamin D levels between 9 and 20 ng/ml. Mean age 56.2 ± 9.3 years, 100% female | |

| Interventions | 50 000 IU ergocalciferol/week (n = 25) Placebo (n = 25) |

|

| Outcomes | Visual analogue pain scale, functional pain score, all cause and adverse event withdrawals, and 25-OH vitamin D levels at trial start and end | |

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R2, D2, W1 = 5/5 Oxford Pain Validity Score: 14/16 |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Random number table |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Vitamin D and placebo capsules (identical appearance) dispensed in identical prescription containers by hospital pharmacy |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Colour matched, identical appearing capsules of vitamin D and placebo |

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, placebo controlled trial. Trial duration 16 weeks | |

| Participants | Patients (n = 171) with rheumatoid arthritis. Data for 140 participants (excluding 31 dropouts): no mean age reported; age groups: under 29 years (n = 3), 30-39 years (n = 12), 40-49 years (n = 19), 50-59 years (n = 51), 60-69 years (n = 32), above 70 years (n = 23); 83% female | |

| Interventions | Alfacalcidol (1-hydroxycholecalciferol) 1.0 μg/day (n = 59) Alfacalcidol 2.0 μg/day (n = 55) Placebo (n = 57) |

|

| Outcomes | Patient global impression of change, number with any and serious adverse events, withdrawals (all cause, adverse event, and lack of efficacy withdrawals), and other outcomes | |

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, D1, W1 = 3/5 Oxford Pain Validity Score: 16/16 |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Randomly allocated by ‘controller’; no further details given |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Administered by (presumably independent) ‘controller’ |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Identical placebo; verified by ‘controller’ |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Arden 2006 | Not all participants had chronic pain. Does not report on outcomes of vitamin D therapy |

| Björkman 2008 | Pain not always self-rated (“self- or nurse-reported”). No other outcomes of interest |

| de Nijs 2006 | Participants were not required to have chronic pain |

| Dottori 1982 | Not explicitly described as double-blind |

| Grove 1981 | Fluoride and calcium administered concurrently with calciferol but not given to comparator group |

| Krocker 2008 | All patients received vitamin D. Described as “pseudorandomised”. Not described as double-blind |

| Lyritis 1994 | Not clear that all participants had chronic pain |

| Ringe 2000 | Not clear that all participants had chronic pain. Not described as double-blind |

| Ringe 2004 | Not clear that all participants had chronic pain. Not described as double-blind |

| Ringe 2005 | Not clear that all participants had chronic pain. Not described as double-blind. Reports on same results as Ringe 2004 |

| Ringe 2007 | Not clear that all participants had chronic pain. Not described as double-blind |

DATA AND ANALYSES

This review has no analyses.

Appendix 1. MEDLINE search strategy

Vitamin D/explode

vitamin D

vitamin D2

vitamin D3

1-alpha hydroxyvitamin D3

1-alpha-hydroxy-vitamin D3

1-alpha hydroxycalciferol

1-alpha-hydroxy-calciferol

1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D3

1,25-dihydroxy-vitamin D3

1,25 dihydroxycholecalciferol

1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol

25-hydroxycholecalciferol

25 hydroxycholecalciferol

25 hydroxyvitamin D

25-hydroxy-vitamin D

alfacalcidol

calcidiol

calcitriol

calcifediol

calciferol

ergocalciferol

cholecalciferol

OR/1-23

pain*

randomized controlled trial.pt

controlled clinical trial.pt

randomized.ab

placebo.ab

drug therapy.fs

randomly.ab

trial.ab

groups.ab

OR/26-33

humans.sh

34 AND 35

24 AND 25 AND 36

Appendix 2. EMBASE search strategy

Vitamin D/explode

vitamin D

vitamin D2

vitamin D3

1-alpha hydroxyvitamin D3

1-alpha-hydroxy-vitamin D3

1-alpha hydroxycalciferol

1-alpha-hydroxy-calciferol

1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D3

1,25-dihydroxy-vitamin D3

1,25 dihydroxycholecalciferol

1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol

25-hydroxycholecalciferol

25 hydroxycholecalciferol

25 hydroxyvitamin D

25-hydroxy-vitamin D

alfacalcidol

calcidiol

calcitriol

calcifediol

calciferol

ergocalciferol

cholecalciferol

OR/1-23

pain*

random*.ti,ab

factorial*.ti,ab

(crossover* or cross over* or cross-over*).ti,ab

placebo*.ti,ab

(doubl* adj blind*).ti,ab

((doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj25 (blind$ or mask$)).ab

assign*.ti,ab

allocat*.ti,ab

CROSSOVER PROCEDURE.sh

DOUBLE-BLIND PROCEDURE.sh.

RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIAL.sh

OR/26-36

24 AND 25 AND 37

Appendix 3. CENTRAL search strategy

MeSH descriptor Vitamin D explode tree 1

vitamin D:ti,ab,kw

vitamin D2:ti,ab,kw

vitamin D3:ti,ab,kw

1-alpha hydroxyvitamin D3:ti,ab,kw

1-alpha-hydroxy-vitamin D3:ti,ab,kw

1-alpha hydroxycalciferol:ti,ab,kw

1-alpha-hydroxy-calciferol:ti,ab,kw

1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D3:ti,ab,kw

1,25-dihydroxy-vitamin D3:ti,ab,kw

1,25 dihydroxycholecalciferol:ti,ab,kw

1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol:ti,ab,kw

25-hydroxycholecalciferol:ti,ab,kw

25 hydroxycholecalciferol:ti,ab,kw

25 hydroxyvitamin D:ti,ab,kw

25-hydroxy-vitaminD:ti,ab,kw

alfacalcidol:ti,ab,kw

calcidiol:ti,ab,kw

calcitriol:ti,ab,kw

calcifediol:ti,ab,kw

calciferol:ti,ab,kw

ergocalciferol:ti,ab,kw

cholecalciferol:ti,ab,kw

OR/1-23

pain*:ti,ab,kw

Randomized Controlled Trial.pt

random*:ti,ab,kw

MeSH descriptor Double-Blind Method

OR/26-28

24 AND 25 AND 29

Limit 30 to Clinical Trials (CENTRAL)

WHAT’S NEW

Last assessed as up-to-date: 2 October 2009.

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 27 June 2012 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

| 25 April 2012 | Review declared as stable | The authors will update this review in 2014 or sooner if evidence comes to light to alter the current conclusions |

HISTORY

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 2009

Review first published: Issue 1, 2010

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 24 September 2010 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

DIFFERENCES BETWEEN PROTOCOL AND REVIEW

After the search and examination of the retrieved studies it was decided to include an additional secondary outcome (“other patientrated pain outcomes”).

Since the included studies were both clinically and methodologically heterogeneous, no pooled analysis was possible, no formal assessment of heterogeneity was undertaken, and no sensitivity analyses were undertaken. It had been planned to assess efficacy at different time points but there were insufficient data to do this.

Footnotes

DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST

SS, RAM, HJM, SD have received research support from charities, government and industry sources at various times. RAM and HJM have consulted for various pharmaceutical companies and have received lecture fees from pharmaceutical companies related to analgesics and other healthcare interventions.

References to studies included in this review

- Brohult 1973 {published data only} .Brohult J, Jonson B. Effects of large doses of calciferol on patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Scandinavian Journal of Rheumatology. 1973;2(4):173–6. doi: 10.3109/03009747309097085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Munno 1989 {published data only} .Di Munno O, Beghe F, Favini P, Di Giuseppe P, Pontrandolfo A, Occhipinti G, Pasero G. Prevention of glucocorticoid-induced osteopenia: effect of oral 25-hydroxyvitamin D and calcium. Clinical Rheumatology. 1989;8(2):202–7. doi: 10.1007/BF02030075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner 2008 {published data only} .Warner AE, Arnspiger SA. Diffuse musculoskeletal pain is not associated with low vitamin D levels or improved by treatment with vitamin D. Journal of Clinical Rheumatology: Practical Reports on Rheumatic & Musculoskeletal Diseases. 2008;14(1):12–6. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0b013e31816356a9. DOI: 10.1097/RHU.0b013c31816356a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi 1989 {published data only} .Yamauchi Y, Tsunematsu T, Konda S, Hoshino T, Itokawa Y, Hoshizaki H. A double blind trial of alfacalcidol on patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) Ryumachi. [Rheumatism] 1989;29(1):11–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

- Arden 2006 {published data only} .Arden NK, Crozier S, Smith H, Anderson F, Edwards C, Raphael H, et al. Knee pain, knee osteoarthritis, and the risk of fracture. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2006;55(4):610–5. doi: 10.1002/art.22088. DOI: 10.1002/art.22088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Björkman 2008 {published data only} .Björkman M, Sorva A, Tilvis R. Vitamin D supplementation has no major effect on pain or pain behavior in bedridden geriatric patients with advanced dementia. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research. 2008;20(4):316–21. doi: 10.1007/BF03324862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Nijs 2006 {published data only} .de Nijs RN, Jacobs JW, Lems WF, Laan RF, Algra A, Huisman AM, et al. STOP Investigators Alendronate or alfacalcidol in glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;355(7):675–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053569. CTG: NCT00138983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dottori 1982 {published data only} .Dottori L, D’Ottavio D, Brundisini B. Calcifediol and calcitonin in the therapy of rheumatoid arthritis. A short-term controlled study [Calcifediolo e calcitonina nella terapia dell’artrite reumatoide. Studio controllato a breve termine] Minerva Medica. 1982;73(43):3033–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grove 1981 {published data only} .Grove O, Halver B. Relief of osteoporotic backache with fluoride, calcium, and calciferol. Acta Medica Scandinavica. 1981;209(6):469–71. doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1981.tb11631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krocker 2008 {published data only} .Krocker D, Ullrich H, Buttgereit F, Perka C. Influence of adjuvant pain medication on quality of life in the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis [Einfluss der adjuvanten Schmerztherapie in der Behandlung der postmenopausalen Osteoporose auf die Lebensqualität] Der Orthopäde. 2008;37(5):435–9. doi: 10.1007/s00132-008-1259-8. DOI: 10.1007/s00132-008-1259-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyritis 1994 {published data only} .Lyritis GP, Androulakis C, Magiasis B, Charalambaki Z, Tsakalakos N. Effect of nandrolone decanoate and 1-alpha-hydroxy-calciferol on patients with vertebral osteoporotic collapse. A double-blind clinical trial. Bone and Mineral. 1994;27(3):209–17. doi: 10.1016/s0169-6009(08)80194-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringe 2000 {published data only} .Ringe JD, Cöster A, Meng T, Schacht E, Umbach R. Therapy of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis with alfacalcidol/calcium and vitamin D/calcium [Therapie der Glucocorticoid-induzierten Osteoporose mit Alfacalcidol/Kalzium und Vitamin D/Kalzium] Zeitschrift für Rheumatologie. 2000;59(3):176–82. doi: 10.1007/s003930070078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringe 2004 {published data only} .Ringe JD, Dorst A, Faber H, Schacht E, Rahlfs VW. Superiority of alfacalcidol over plain vitamin D in the treatment of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Rheumatology International. 2004;24(2):63–70. doi: 10.1007/s00296-003-0361-9. DOI: 10.1007/s00296-003-0361-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringe 2005 {published data only} .Ringe JD, Faber H, Fahramand P, Schacht E. Alfacalcidol versus plain vitamin D in the treatment of glucocorticoid/inflammation-induced osteoporosis. Journal of Rheumatology Supplement. 2005;76:33–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringe 2007 {published data only} .Ringe JD, Farahmand P, Schacht E, Rozehnal A. Superiority of a combined treatment of Alendronate and Alfacalcidol compared to the combination of Alendronate and plain vitamin D or Alfacalcidol alone in established postmenopausal or male osteoporosis (AAC-Trial) Rheumatology International. 2007;27(5):425–34. doi: 10.1007/s00296-006-0288-z. DOI: 10.1007/s00296-006-0288-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

- Alonso 2004 .Alonso J, Ferrer M, Gandek B, Ware JE, Jr, Aaronson NK, Mosconi P, et al. Health-related quality of life associated with chronic conditions in eight countries: results from the International Quality of Life Assessment (IQOLA) Project. Quality of Life Research. 2004;13(2):283–98. doi: 10.1023/b:qure.0000018472.46236.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atherton 2009 .Atherton K, Berry DJ, Parsons T, Macfarlane GJ, Power C, Hypponen E. Vitamin D and chronic widespread pain in a white middle-aged British population: evidence from a cross-sectional population survey. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2009;68(6):817–22. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.090456. DOI: 10.1136/ard.2008.090456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Autier 2007 .Autier P, Gandini S. Vitamin D supplementation and total mortality: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2007;167:1730–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.16.1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannwarth 2009 .Bannwarth B, Blotman F, Roué-Le Lay K, Caubère JP, André E, Taïeb C. Fibromyalgia syndrome in the general population of France: A prevalence study. Joint Bone Spine. 2009;76(2):184–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett 2001 .Bennett M, Heard R. Treatment of multiple sclerosis with hyperbaric oxygen therapy. Undersea and Hyperbaric Medicine. 2001;28(3):117–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson 2006 .Benson J, Wilson A, Stocks N, Moulding N. Muscle pain as an indicator of vitamin D deficiency in an urban Australian Aboriginal population. The Medical Journal of Australia. 2006;185:76–7. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2006.tb00475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll 1996 .Carroll D, Tramèr M, McQuay H, Nye B, Moore A. Randomization is important in studies with pain outcomes: systematic review of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation in acute postoperative pain. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 1996;77(6):798–803. doi: 10.1093/bja/77.6.798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook 1995 .Cook RJ, Sackett DL. The number needed to treat: a clinically useful measure of treatment effect. BMJ. 1995;310:452–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6977.452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin 2008 .Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Wyrwich KW, Beaton D, Cleeland CS, Farrar JT, et al. Interpreting the clinical importance of treatment outcomes in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Journal of Pain. 2008;9(2):105–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.09.005. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott 1999 .Elliott AM, Smith BH, Penny KI, Smith WC, Chambers WA. The epidemiology of chronic pain in the community. Lancet. 1999;354(9186):1248–52. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)03057-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holick 2007 .Holick MF. Vitamin D deficiency. New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;357:266–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra070553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jadad 1996a .Jadad AR, Carroll D, Moore A, McQuay H. Developing a database of published reports of randomised clinical trials in pain research. Pain. 1996;66(2-3):239–46. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(96)03033-3. DOI: 10.1016/0304-3959(96)03033-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jadad 1996b .Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Controlled Clinical Trials. 1996;17:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. DOI: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- L’Abbé 1987 .L’Abbé KA, Detsky AS, O’Rourke K. Meta-analysis in clinical research. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1987;107:224–33. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-107-2-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leavitt 2008 .Leavitt SB. Vitamin D for chronic pain. Practical Pain Management. 2008;8(6):24–42. [Google Scholar]

- Lotfi 2007 .Lotfi A, Abdel-Nasser AM, Hamdy A, Omran AA, El-Rehany MA. Hypovitaminosis D in female patients with chronic low back pain. Clinical Rheumatology. 2007;26:1895–901. doi: 10.1007/s10067-007-0603-4. DOI: 10.1007/s10067-007-0603-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mas 2008 .Mas AJ, Carmona L, Valverde M, Ribas B, EPISER Study Group Prevalence and impact of fibromyalgia on function and quality of life in individuals from the general population: results from a nationwide study in Spain. Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology - Journal of Rheumatology. 2008;26(4):519–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQuay 1996 .McQuay H, Carroll D, Moore A. Variation in the placebo effect in randomised controlled trials of analgesics: all is as blind as it seems. Pain. 1996;64(2):331–5. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(95)00116-6. DOI: 10.1016/0304-3959(95)00116-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQuay 2007 .McQuay HJ, Smith LA, Moore RA. Chronic pain. In: Stevens A, Raferty J, Mant J, Simpson S, editors. Health Care Needs Assessment. Radcliffe Publishing Ltd; Oxford: 2007. pp. 519–600. ISBN: 978-1-84619-063-6. [Google Scholar]

- Mitsikostas 1996 .Mitsikostas DD, Tsaklakidou D, Athanasiadis N, Thomas A. The prevalence of headache in Greece: correlations to latitude and climatological factors. Headache. 1996;36:168–73. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.1996.3603168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore 1998 .Moore RA, Gavaghan D, Tramèr MR, Collins SL, McQuay HJ. Size is everything-large amounts of information are needed to overcome random effects in estimating direction and magnitude of treatment effects. Pain. 1998;78(3):209–16. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00140-7. DOI: 10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00140-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore 2006 .Moore A, McQuay H. Bandolier’s little book of making sense of the medical evidence. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Moore 2008 .Moore RA, Moore OA, Derry S, McQuay HJ. Numbers needed to treat calculated from responder rates give a better indication of efficacy in osteoarthritis trials than mean pain scores. Arthritis Research and Therapy. 2008;10(2):R39. doi: 10.1186/ar2394. DOI: 10.1186/ar2394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris 1995 .Morris JA, Gardner MJ. Calculating confidence intervals for relative risk, odds ratios and standardised ratios and rates. In: Gardner MJ, Altman DG, editors. Statistics with Confidence - Confidence Intervals and Statistical Guidelines. British Medical Journal; London: 1995. pp. 50–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins 2000 .Perkins FM, Kehlet H. Chronic pain as an outcome of surgery: a review of predictive factors. Anesthesiology. 2000;93:1123–33. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200010000-00038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saastamoinen 2009 .Saastamoinen P, Laaksonen M, Lahelma E, Leino-Arjas P. The effect of pain on sickness absence among middle-aged municipal employees. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2009;66(2):131–6. doi: 10.1136/oem.2008.040733. DOI: 10.1136/oem.2008.040733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saps 2008 .Saps M, Blank C, Khan S, Seshadri R, Marshall B, Bass L, et al. Seasonal variation in the presentation of abdominal pain. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 2008;46:279–84. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181559bd3. DOI: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181559bd3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith 2000 .Smith LA, Oldman AD, McQuay HJ, Moore RA. Teasing apart quality and validity in systematic reviews: an example from acupuncture trials in chronic neck and back pain. Pain. 2000;86:119–32. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(00)00234-7. DOI: 10.1016/S0304-3959 (00)00234-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhaak 1998 .Verhaak PF, Kerssens JJ, Dekker J, Sorbi MJ, Bensing JM. Prevalence of chronic benign pain disorder among adults: a review of the literature. Pain. 1998;77(3):231–9. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00117-1. DOI: 10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00117-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng 2004 .Zeng QY, Chen R, Xiao ZY, Huang SB, Liu Y, Xu JC, et al. Low prevalence of knee and back pain in southeast China; the Shantou COPCORD study. Journal of Rheumatology. 2004;31:2439–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to other published versions of this review

- Straube 2009 .Straube S, Moore RA, Derry S, McQuay HJ. Vitamin D and chronic pain. Pain. 2009;141(1-2):10–3. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.11.010. DOI: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Indicates the major publication for the study