Abstract

Background

Oxycodone is a strong opioid agonist used to treat severe pain. It is commonly combined with milder analgesics such as paracetamol. This review updates a previous review that concluded, based on limited data, that all doses of oxycodone exceeding 5 mg, with or without paracetamol, provided analgesia in postoperative pain, but with increased incidence of adverse events compared with placebo. Additional new studies provide more reliable estimates of efficacy and harm.

Objectives

To assess efficacy, duration of action, and associated adverse events of single dose oral oxycodone, with or without paracetamol, in acute postoperative pain in adults.

Search methods

Cochrane CENTRAL, MEDLINE, EMBASE and Oxford Pain Relief Database, searched in May 2009.

Selection criteria

Randomised, double blind, placebo‐controlled trials of single dose orally administered oxycodone, with or without paracetamol, in adults with moderate to severe acute postoperative pain.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed trial quality and extracted data. Pain relief or pain intensity data were extracted and converted into the dichotomous outcome of number of participants with at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours, from which relative risk and number‐needed‐to‐treat‐to‐benefit (NNT) were calculated. Numbers of participants remedicating over specified time periods, and time‐to‐use of rescue medication, were sought as additional measures of efficacy. Adverse events and withdrawals information was collected.

Main results

This updated review includes 20 studies, with 2641 participants. For oxycodone 15 mg alone compared with placebo, the NNT for at least 50% pain relief was 4.6 (95% Confidence Interval 2.9 to 11). For oxycodone 10 mg plus paracetamol 650 mg, the NNT was 2.7 (2.4 to 3.1). A dose response was demonstrated for this outcome with combination therapy. Duration of effect was 10 hours with oxycodone 10 mg plus paracetamol 650 mg, and 4 hours with half that dose. Fewer participants needed rescue medication over 6 hours at the higher dose. Adverse events occurred more frequently with combination therapy than placebo, but were generally described as mild to moderate in severity and rarely led to withdrawal.

Authors' conclusions

Single dose oxycodone is an effective analgesic in acute postoperative pain at doses over 5 mg; oxycodone is two to three times stronger than codeine. Efficacy increases when combined with paracetamol. Oxycodone 10 mg plus paracetamol 650 mg provides good analgesia to half of those treated, comparable to commonly used non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs, with the benefit of longer duration of action.

Plain language summary

Single dose oxycodone and oxycodone plus paracetamol (also known as acetaminophen) for analgesia in adults with acute postoperative pain

This review update assessed evidence from 2641 participants in 20 randomised, double blind, placebo‐controlled clinical trials of oxycodone, with or without paracetamol, in adults with moderate to severe acute postoperative pain. Oral oxycodone 10 mg plus paracetamol 650 mg provided effective analgesia. About half of those treated experienced at least half pain relief over 4 to 6 hours, and the effects lasting up to 10 hours. Higher doses gave more effect. Associated adverse events (predominantly nausea, vomiting, dizziness and somnolence) were more frequent with oxycodone or oxycodone plus paracetamol than with placebo, but studies of this type are of limited use for studying adverse effects. Limited information about oxycodone on its own suggests that it provided analgesia at doses greater than 5 mg, and that addition of paracetamol made it more effective.

Background

This review is an update of a previously published review in The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Issue 4, 2000) on 'Single dose oxycodone and oxycodone plus paracetamol (acetaminophen) for acute postoperative pain' (Edwards 2000). The title now states that the review is limited to adults and oral administration only.

Acute pain occurs as a result of tissue damage either accidentally due to an injury or as a result of surgery. Acute postoperative pain is a manifestation of inflammation due to tissue injury. The management of postoperative pain and inflammation is a critical component of patient care. This is one of a series of reviews whose aim is to increase awareness of the range of analgesics that are potentially available, and present evidence for relative analgesic efficacy through indirect comparisons with placebo, in very similar trials performed in a standard manner, with very similar outcomes, and over the same duration. Such relative analgesic efficacy does not in itself determine choice of drug for any situation or patient, but guides policy‐making at the local level. Recently published reviews include paracetamol (Toms 2008), celecoxib (Derry 2008), naproxen (Derry C 2009a), ibuprofen (Derry C 2009b), diclofenac (Derry P 2009) and etoricoxib (Clarke 2009).

Single dose trials in acute pain are commonly short in duration, rarely lasting longer than 12 hours. The numbers of participants are small, allowing no reliable conclusions to be drawn about safety. To show that the analgesic is working it is necessary to use placebo (McQuay 2005). There are clear ethical considerations in doing this. These ethical considerations are answered by using acute pain situations where the pain is expected to go away, and by providing additional analgesia, commonly called rescue analgesia, if the pain has not diminished after about an hour. This is reasonable, because not all participants given an analgesic will have significant pain relief. Approximately 18% of participants given placebo will have significant pain relief (Moore 2005), and up to 50% may have inadequate analgesia with active medicines. The use of additional or rescue analgesia is hence important for all participants in the trials.

Clinical trials measuring the efficacy of analgesics in acute pain have been standardised over many years. Trials have to be randomised and double blind. Typically, in the first few hours or days after an operation, patients develop pain that is moderate to severe in intensity, and will then be given the test analgesic or placebo. Pain is measured using standard pain intensity scales immediately before the intervention, and then using pain intensity and pain relief scales over the following 4 to 6 hours for shorter acting drugs, and up to 12 or 24 hours for longer acting drugs. Pain relief of half the maximum possible pain relief or better (at least 50% pain relief) is typically regarded as a clinically useful outcome. For patients given rescue medication it is usual for no additional pain measurements to be made, and for all subsequent measures to be recorded as initial pain intensity or baseline (zero) pain relief (baseline observation carried forward). This process ensures that analgesia from the rescue medication is not wrongly ascribed to the test intervention. In some trials the last observation is carried forward, which gives an inflated response for the test intervention compared to placebo, but the effect has been shown to be negligible over 4 to 6 hours (Moore 2005). Patients usually remain in the hospital or clinic for at least the first six hours following the intervention, with measurements supervised, although they may then be allowed home to make their own measurements in trials of longer duration.

Oxycodone is a strong opioid agonist, developed in the early 20th century, and chemically related to codeine. It is considered to be comparable to morphine for efficacy, and similar for adverse events, with the exception of hallucinations, which tend to occur rarely with oxycodone (Poyhia 1993). Like morphine, it can be administered via a variety of routes including oral or rectal, and intramuscular, intravenous, or subcutaneous injection. Its analgesic potency makes it useful for the management of severe pain, usually acute postoperative, post‐traumatic or cancer pain. Oxycodone is commonly combined with milder analgesics, such as paracetamol. The purpose is to increase efficacy by simultaneously using drugs with distinct mechanisms of action with the aim of reducing the amount of opioid required for a given level of response, and so reducing adverse events (Edwards 2002). Repeated administration of oxycodone can cause dependence and tolerance, and its potential for abuse is well known. Regulation of supply varies between countries, but in many, all oxycodone preparations are controlled substances.

This quantitative systematic review assesses the efficacy and adverse effects of single‐dose oral oxycodone, alone and in combination with paracetamol, compared with placebo in the treatment of adults with moderate to severe postoperative pain. The previous review (Edwards 2000) found seven studies with oxycodone alone, or with paracetamol, with oxycodone at oral doses of 5 mg to 30 mg. Results for efficacy and adverse events were based on small numbers of patients, emphasising the need to update the review with trials published since 2000.

Objectives

To evaluate the analgesic efficacy and safety of oral oxycodone alone or in combination with paracetamol in the treatment of acute postoperative pain, using methods that permit comparison with other analgesics evaluated in the same way, using wider criteria of efficacy recommended by an in‐depth study at the individual patient level (Moore 2005).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Studies were included if they were full publications of double blind trials of a single dose oral oxycodone, alone or in combination with paracetamol, compared with placebo for the treatment of moderate to severe postoperative pain in adults, with at least 10 participants randomly allocated to each treatment group. Multiple dose studies were included if appropriate data from the first dose were available, and cross‐over studies were included provided that data from the first arm were presented separately.

Studies were excluded if they were:

posters or abstracts not followed up by full publication;

reports of studies concerned with pain other than postoperative pain (including experimental pain);

studies using healthy volunteers;

studies where pain relief was assessed by clinicians, nurses or carers (i.e., not patient‐reported);

studies of less than 4 hours' duration or which failed to present data over 4 to 6 hours post‐dose.

Types of participants

Studies of adult participants (15 years old or above) with established moderate to severe postoperative pain were included. For studies using a visual analogue scale (VAS), pain of at least moderate intensity was assumed when the VAS score was greater than 30 mm (Collins 1997). Studies of participants with postpartum pain were included provided the pain investigated resulted from episiotomy or Caesarean section (with or without uterine cramp). Studies investigating participants with pain due to uterine cramps alone were excluded.

Types of interventions

Orally administered oxycodone, alone or in combination with paracetamol, and matched placebo for relief of postoperative pain.

Types of outcome measures

Data collected included the following.

characteristics of participants;

pain model;

patient‐reported pain at baseline (physician, nurse, or carer reported pain was not included in the analysis);

patient‐reported pain relief and/or pain intensity expressed hourly over 4 to 6 hours using validated pain scales (pain intensity and pain relief in the form of visual analogue scales (VAS) or categorical scales, or both), or reported total pain relief (TOTPAR) or summed pain intensity difference (SPID) at 4 to 6 hours;

patient‐reported global assessment of treatment (PGE), using a standard five‐point scale;

number of participants using rescue medication, and the time of assessment;

time to use of rescue medication;

withdrawals ‐ all cause, adverse event;

adverse events ‐ participants experiencing one or more, and any serious adverse event, and the time of assessment.

Search methods for identification of studies

The following electronic databases were searched:

Cochrane CENTRAL (Issue 3, 1999 for original search, Issue 2 2009 for the update);

MEDLINE via Ovid (1966 to October 1999 for the original search and 1999 to May 2009 for the update);

EMBASE via Ovid (1980 to October 1999 for the original search and 1999 to May 2009 for the update);

Oxford Pain Database (Jadad 1996a);

Biological Abstracts (to October 1999 for the original search).

Reference lists of retrieved articles were searched.

See Appendix 1 for the MEDLINE search strategy, Appendix 2 for the EMBASE search strategy, and Appendix 3 for the Cochrane CENTRAL search strategy.

Language

No language restriction was applied.

Unpublished studies

Abstracts, conference proceedings and other grey literature were not searched.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently assessed and agreed the search results for studies that might be included in the updated review. Disagreements were resolved by consensus or referral to a third review author.

Quality assessment

Two review authors independently assessed the included studies for quality using a five‐point scale (Jadad 1996b).

The scale used is as follows.

Is the study randomised? If yes give one point.

Is the randomisation procedure reported and is it appropriate? If yes add one point, if no deduct one point.

Is the study double blind? If yes then add one point.

Is the double blind method reported and is it appropriate? If yes add one point, if no deduct one point.

Are the reasons for patient withdrawals and dropouts described? If yes add one point.

The results are described in the 'Methodological quality of included studies' section below, and in the 'Characteristics of included studies' table.

Data management

Data were extracted by two review authors and recorded on a standard data extraction form. Data suitable for pooling were entered into RevMan 5.0.

Data Analysis

QUOROM guidelines were followed (Moher 1999). For efficacy analyses we used the number of participants in each treatment group who were randomised, received medication, and provided at least one post‐baseline assessment. For safety analyses we used number of participants who received study medication in each treatment group. Analyses were planned for different doses. Sensitivity analyses were planned for pain model (dental versus other postoperative pain), trial size (39 or fewer versus 40 or more per treatment arm), and quality score (two versus three or more). A minimum of two studies and 200 participants were required for any analysis (Moore 1998).

Primary outcome:

Number of participants achieving at least 50% pain relief

For each study, mean TOTPAR (total pain relief) or SPID (summed pain intensity difference) for active and placebo groups were converted to %maxTOTPAR or %maxSPID by division into the calculated maximum value (Cooper 1991). The proportion of participants in each treatment group who achieved at least 50%maxTOTPAR was calculated using verified equations (Moore 1996; Moore 1997a; Moore 1997b). These proportions were then converted into the number of participants achieving at least 50%maxTOTPAR by multiplying by the total number of participants in the treatment group. Information on the number of participants with at least 50%maxTOTPAR for active treatment and placebo was then used to calculate relative benefit, and number needed to treat to benefit (NNT) when there was a statistically significant effect. Pain measures accepted for the calculation of TOTPAR or SPID were:

five‐point categorical pain relief (PR) scales with comparable wording to "none, slight, moderate, good or complete";

four‐point categorical pain intensity (PI) scales with comparable wording to "none, mild, moderate, severe";

Visual analogue scales (VAS) for pain relief;

VAS for pain intensity.

If none of these measures were available, numbers of participants reporting "very good or excellent" on a five‐point categorical global scale with the wording "poor, fair, good, very good, excellent" were taken as those achieving at least 50% pain relief (Collins 2001).

Further details of the scales and derived outcomes are in the glossary (Appendix 4).

Secondary outcomes:

1. Use of rescue medication

Numbers of participants requiring rescue medication were used to calculate relative risk (RR) and numbers needed to treat to prevent (NNTp) use of rescue medication for treatment and placebo groups. Median (or mean) time to use of rescue medication was used to calculate the weighted mean of the median (or mean) for the outcome. Weighting was by number of participants.

2. Adverse events

Numbers of participants reporting adverse events for each treatment group were used to calculate RR and numbers needed to treat to harm (NNH) estimates for:

any adverse event;

any serious adverse event (as reported in the study);

withdrawal due to an adverse event.

3. Withdrawals

Withdrawals for reasons other than lack of efficacy (participants using rescue medication ‐ see above) and adverse events were noted, as were exclusions from analysis where data were presented.

Relative benefit (RB) or RR estimates were calculated with 95% confidence intervals (CI) using a fixed‐effect model (Morris 1995). NNT, NNTp and NNH with 95% CI were calculated using the pooled number of events by the method of Cook and Sackett (Cook 1995). A statistically significant difference from control was assumed when the 95% CI of the RB did not include the number one.

Homogeneity of studies was assessed visually (L'Abbè 1987). The z test (Tramèr 1997) was used to determine if there was a significant difference between NNTs for different doses of active treatment, or between groups in the sensitivity analyses.

Results

Description of studies

The original review included seven studies (Cooper 1980; Fricke 1997; Johnson 1997; Reines 1994; Sunshine 1993; Sunshine 1996; Young 1979). One of these studies (Young 1979) has not been included in the current review because on looking at the study again it appears that pain relief may not have been patient‐reported.

New searches in December 2008 identified 15 more recent studies that were potentially relevant; 14 of these fit the inclusion criteria (Aqua 2007; Chang 2004a; Chang 2004b; Daniels 2002; Desjardins 2007; Gammaitoni 2003; Gimbel 2004; Korn 2004; Litkowski 2005; Malmstrom 2005; Malmstrom 2006; Palangio 2000; Singla 2005; Van Dyke 2004). One study, de Beer 2005, was excluded after reading the full paper because it had no placebo control.

An updated search in May 2009 identified two additional studies (Daniels 2009; Stegmann 2008). These studies are awaiting classification and are not included in this analysis.

Twenty studies are included in total for this updated review. All of the included studies had more than one active treatment arm. The active treatments used were oxycodone alone (immediate release and controlled release formulations), oxycodone plus paracetamol, and other analgesic drugs (mostly non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) but also other opioids). Some studies used both oxycodone alone and oxycodone plus paracetamol active treatment arms.

The majority of studies used the immediate release form of oxycodone but in two studies controlled release oxycodone (oxycodone CR) was also used as an active treatment (Gammaitoni 2003; Sunshine 1996). There were no studies in which oxycodone CR was used as the only active treatment.

In studies using oxycodone alone (Aqua 2007; Cooper 1980; Gammaitoni 2003; Gimbel 2004; Singla 2005; Sunshine 1996; Van Dyke 2004), the dose of oxycodone ranged between 5 mg and 15 mg and the dose of oxycodone CR ranged between 10 mg and 30 mg. In studies using oxycodone plus paracetamol (Cooper 1980; Chang 2004a; Chang 2004b; Daniels 2002; Desjardins 2007; Fricke 1997; Gammaitoni 2003; Johnson 1997; Korn 2004; Litkowski 2005; Malmstrom 2005; Malmstrom 2006; Palangio 2000; Reines 1994; Sunshine 1993; Sunshine 1996) the dose of oxycodone ranged between 5 mg and 15 mg, and the dose of paracetamol ranged between 325 mg and 1000 mg. In studies using oxycodone plus paracetamol several different combinations of dosages of the two drugs were used. Higher doses of oxycodone tended to be used with higher doses of paracetamol.

Overall, 482 participants received oxycodone alone, 1192 received oxycodone plus paracetamol, and 967 received placebo. For the comparison of oxycodone alone versus placebo, 482 participants were treated with oxycodone and 363 with placebo. For the comparison of oxycodone plus paracetamol versus placebo, 1192 participants were treated with oxycodone plus paracetamol and 704 with placebo.

Twelve studies enrolled participants after extraction of at least one impacted molar ("dental pain") (Chang 2004a; Chang 2004b; Cooper 1980; Daniels 2002; Desjardins 2007; Fricke 1997; Gammaitoni 2003; Korn 2004; Litkowski 2005; Malmstrom 2005; Malmstrom 2006; Van Dyke 2004). The other studies enrolled participants with pain after a variety of different types of surgery including orthopaedic, abdominal surgery (including general, obstetric and gynaecological) (Aqua 2007; Gimbel 2004; Johnson 1997; Palangio 2000; Reines 1994; Singla 2005; Sunshine 1993; Sunshine 1996).

The duration of the single dose phase was 4 hours in one study (Cooper 1980), 6 hours in six studies (Aqua 2007; Litkowski 2005; Malmstrom 2006; Reines 1994; Singla 2005; Van Dyke 2004), 8 hours in 6 studies (Fricke 1997; Gammaitoni 2003; Gimbel 2004; Johnson 1997; Palangio 2000; Sunshine 1993) and 24 hours in six studies (Chang 2004a; Chang 2004b; Daniels 2002; Desjardins 2007; Korn 2004; Malmstrom 2005).

Full details are given in the 'Characteristics of included studies' table.

Risk of bias in included studies

All included studies were randomized, double‐blind, and placebo‐controlled. Five studies were given a quality score of five (Aqua 2007; Chang 2004a; Chang 2004b; Desjardins 2007; Malmstrom 2005), eleven a score of four (Cooper 1980; Daniels 2002; Gammaitoni 2003; Johnson 1997; Korn 2004; Malmstrom 2006; Palangio 2000; Singla 2005; Sunshine 1993; Sunshine 1996; Van Dyke 2004), and four a score of three (Fricke 1997; Gimbel 2004; Litkowski 2005; Reines 1994).

Full details are given in the 'Characteristics of included studies' table.

Effects of interventions

Oxycodone (Alone)

Seven studies had treatment arms using oxycodone alone (Aqua 2007; Cooper 1980; Gammaitoni 2003; Gimbel 2004; Singla 2005; Sunshine 1996; Van Dyke 2004); in five studies only the immediate release formulation of oxycodone was used (Aqua 2007; Cooper 1980; Gimbel 2004; Singla 2005; Van Dyke 2004), in one study only the controlled release formulation of oxycodone (oxycodone CR) was used (Gammaitoni 2003), and in one study (Sunshine 1996) both the immediate release and the controlled release formulations of oxycodone were used.

Primary outcome: Participants achieving at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours

(Table 1; Summary of results A).

Oxycodone 5 mg versus placebo

In three studies using oxycodone 5 mg (Cooper 1980; Singla 2005; Van Dyke 2004) there were data from 317 participants (Analysis 1.1).

The proportion of participants experiencing at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours was 25% (39/157; range 13% to 37%).

The proportion of participants experiencing at least 50% pain relief with placebo was 20% (32/160; range 11% to 29%).

The RB of treatment compared with placebo was 1.3 (0.84 to 1.9). The NNT was not calculated.

Oxycodone 10 mg versus placebo

One study used oxycodone 10 mg (99 participants in the comparison) (Gimbel 2004). There were insufficient data for analysis.

Oxycodone 15 mg versus placebo

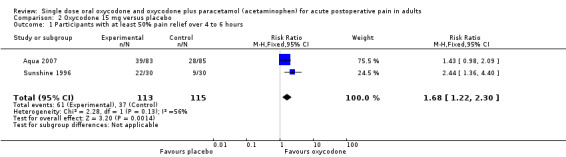

In two studies using oxycodone 15 mg (Aqua 2007; Sunshine 1996) there were data from 228 participants (Analysis 2.1).

The proportion of participants experiencing at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours was 54% (61/113; range 47% to 73%).

The proportion of participants experiencing at least 50% pain relief with placebo was 32% (37/115; range 30% to 33%).

The RB of treatment compared with placebo was 1.7 (1.2 to 2.3), giving an NNT for at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours of 4.6 (2.9 to 11).

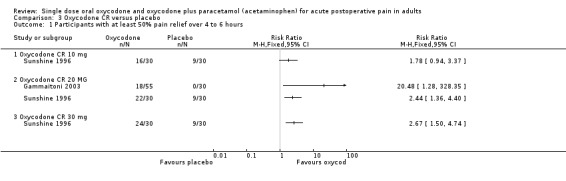

Oxycodone CR 10 mg, Oxycodone CR 20 mg, Oxycodone CR 30 mg

One treatment arm used oxycodone CR 10 mg in 30 participants (Sunshine 1996) two used oxycodone CR 20 mg in a total of 85 participants (Gammaitoni 2003; Sunshine 1996), and one used oxycodone CR 30 mg in 30 participants (Sunshine 1996). There were insufficient data at each dose for formal analysis but the limited data available suggest that treatment with oxycodone CR 20 mg shows benefit compared with placebo (Analysis 3.1).

| Summary of results A: participants with ≥ 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours | |||||

| Dose (mg) | Studies | Participants | Oxycodone(%) | Placebo (%) | NNT (95%CI) |

| Oxycodone 5 mg | 3 | 317 | 25 | 20 | Not calculated |

| Oxycodone 15 mg | 2 | 228 | 54 | 32 | 4.6 (2.9 to 11) |

See also Analysis 1.1; Analysis 2.1 and Analysis 3.1.

Sensitivity analysis of primary outcome

Methodological quality

All studies scored three or more for quality, so no sensitivity analysis was carried out for this criterion.

Pain model dental versus other surgery and trial size

There were insufficient data at any dose to compare dental surgery with other types of surgery, or for larger versus smaller studies.

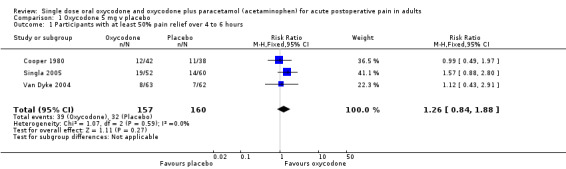

Secondary outcome: Use of rescue medication

Six studies reported on participants requiring rescue medication, four studies at 6 hours (Aqua 2007; Gammaitoni 2003; Singla 2005; Van Dyke 2004 ), one study at 8 hours (Gimbel 2004) and one study (Sunshine 1996) at 12 hours (Table 1).

Oxycodone 5 mg

In two studies using oxycodone 5 mg (Singla 2005; Van Dyke 2004), there were data from 237 participants on the requirement for rescue medication at 6 hours (Analysis 1.2).

The proportion of participants requiring rescue medication after active treatment was 83% (95/115; range 83% to 83%).

The proportion of participants requiring rescue medication after placebo was 88% (107/122; range 84% to 92%).

The RB of treatment compared with placebo was 0.94 (0.85 to 1.1).

There were few data on time to use of rescue medication. The weighted mean of the median time to use of rescue medication was 2.3 hours for oxycodone 5 mg and 2.1 hours for placebo (237 participants) (Singla 2005; Van Dyke 2004). One study (Cooper 1980) reported a similar result for mean time to use of rescue medication.

Oxycodone other doses

In one study using oxycodone 10 mg (Gimbel 2004) there were data on participants using rescue medication at 8 hours. In studies using oxycodone 15 mg, there were data on participants using rescue medication at 6 hours (Aqua 2007), and at 12 hours (Sunshine 1996). There were insufficient data for analysis. There were no data for time to use of rescue medication.

Oxycodone CR

In one study using oxycodone CR 10 mg there were data on participants using rescue medication at 12 hours (Sunshine 1996). In studies using oxycodone CR 20 mg there were data on participants using rescue medication at 6 hours (Gammaitoni 2003), and at 12 hours (Sunshine 1996). In one study using oxycodone CR 30 mg there were data on participants using rescue medication at 12 hours (Sunshine 1996). There were insufficient data for analysis. Only one study (Gammaitoni 2003), using oxycodone CR 20 mg, reported on time to use of rescue medication.

Secondary outcome: Adverse events

(Table 2)

Five studies reported the number of participants with one or more adverse events for each treatment arm in single dose studies (Cooper 1980; Gammaitoni 2003; Singla 2005; Sunshine 1996; Van Dyke 2004). The time over which the information was collected was not always explicitly stated and varied between trials. In some cases, the rescue medication was a further dose of the active drug, or was not specified. In multiple dose studies, there was either no single dose data (Aqua 2007) or active treatment data but no placebo data (Gimbel 2004). Adverse events, where described, were mild to moderate in severity, and predominantly nausea, vomiting, and dizziness. There was no unambiguous report of a serious adverse event in a single dose study or during the single dose phase of a multiple dose study. Gimbel 2004 reported two serious adverse events in the single dose phase, but it is not stated in in which of the five treatment arms these adverse events occurred.

Oxycodone 5 mg versus placebo

In three studies using oxycodone 5 mg (Cooper 1980; Singla 2005; Van Dyke 2004), there were data on having an adverse event from 317 participants (Analysis 1.3).

The proportion of participants having an adverse event after active treatment was 31% (48/157; range 19% to 44%).

The proportion of participants having an adverse event after placebo was 29% (46/160; range 11% to 55%).

The RR of treatment compared with placebo was 1.1 (0.80 to 1.6).

Oxycodone other doses

In one study using both oxycodone 10 mg and oxycodone 15 mg (Sunshine 1996), there were insufficient data for analysis.

Oxycodone CR

One study using oxycodone CR 10 mg (Sunshine 1996), two studies using oxycodone CR 20 mg (Gammaitoni 2003; Sunshine 1996), and one study using oxycodone CR 30 mg (Sunshine 1996) provided data on participants with at least one adverse event; there were insufficient data for analysis.

Secondary outcome: Withdrawals

(Table 2)

Exclusions may not be of any particular consequence in single dose acute pain studies, where most exclusions result from patients not having moderate or severe pain (McQuay 1982).

Participants who took rescue medication were classified as withdrawals due to lack of efficacy, and details, where available, are reported under 'Use of rescue medication' above. Withdrawals due to adverse events were uncommon. In active treatment arms, one participant vomited at an unknown time (Singla 2005). There were two withdrawals because of unspecified adverse events in a placebo arm (Gimbel 2004). In one multi‐dose study there were no data specifically from the single dose phase (Aqua 2007).

Withdrawals for other reasons, such as loss to follow up, were generally rare. A number of studies (e.g., Cooper 1980; Gammaitoni 2003; Gimbel 2004) reported exclusions from efficacy analyses due to protocol violations and invalid data.

Oxycodone plus paracetamol

In all studies using oxycodone plus paracetamol, the immediate release formulation of oxycodone was used.

Primary outcome: Participants achieving at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours

(Table 1; Summary of results B)

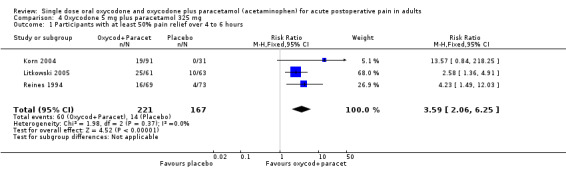

Oxycodone 5 mg plus paracetamol versus placebo

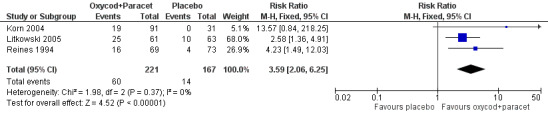

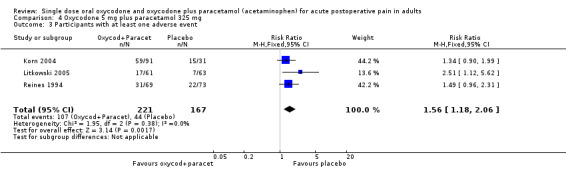

In three studies using oxycodone 5 mg plus paracetamol 325 mg (Korn 2004; Litkowski 2005; Reines 1994), there were data from 388 participants (Analysis 4.1; Figure 1).

1.

Forest plot of comparison: 4 Oxycodone 5 mg plus paracetamol 325 mg, outcome: 4.1 Participants with at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours.

The proportion of participants experiencing at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours with active treatment was 27% (60/221; range 21% to 41%).

The proportion of participants experiencing at least 50% pain relief with placebo was 8% (14/167; range 0% to 16%).

The RB of treatment compared with placebo was 3.6 (2.1 to 6.3), giving an NNT for at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours of 5.4 (3.9 to 8.8).

One treatment arm used oxycodone 5 mg with paracetamol 500 mg in 45 participants (Cooper 1980), and another treatment arm used oxycodone 5 mg with paracetamol 1000 mg in 40 participants (Cooper 1980). There were insufficient data for analysis of these dose combinations.

Oxycodone 10 mg plus paracetamol versus placebo

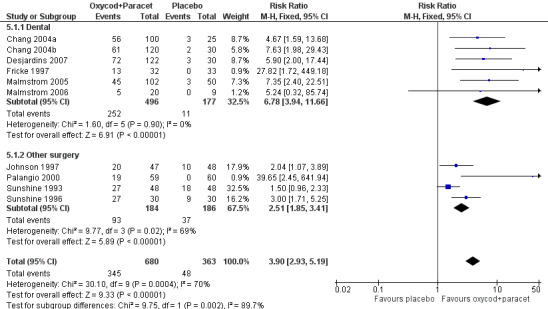

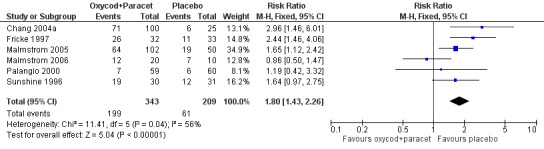

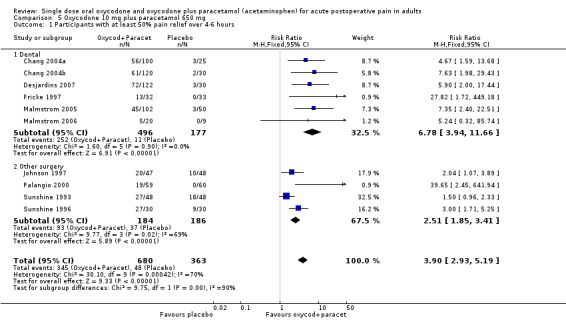

In ten studies using oxycodone 10 mg plus paracetamol 650 mg (Chang 2004a; Chang 2004b; Desjardins 2007; Fricke 1997; Johnson 1997; Malmstrom 2005; Malmstrom 2006; Palangio 2000; Sunshine 1993; Sunshine 1996), there were data from 1043 participants (Analysis 5.1; Figure 2 ‐ see total).

2.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Oxycodone 10 mg plus paracetamol 650 mg, outcome: 2.1 Participants with at least 50% pain relief over 4‐6 hours.

The proportion of participants experiencing at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours with active treatment was 51% (346/680; range 28% to 90%).

The proportion of participants experiencing at least 50% pain relief with placebo was 14% (49/363; range 0% to 38%).

The RB of treatment compared with placebo was 3.9 (2.9 to 5.2), giving an NNT for at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours of 2.7 (2.4 to 3.1).

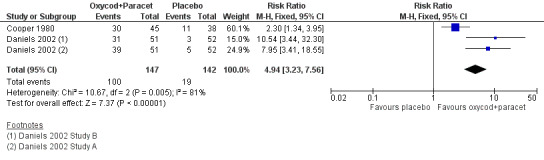

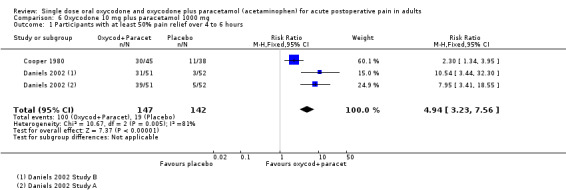

In two studies (three active treatment arms) using oxycodone 10 mg with paracetamol 1000 mg (Cooper 1980; Daniels 2002), there were data from 289 participants. (In Daniels 2002, efficacy data from two centres were reported as separate sets of data ‐ shown as Study A and Study B in 'Characteristics of included studies'.) (Analysis 6.1; Figure 3).

3.

Forest plot of comparison: 6 Oxycodone 10 mg plus paracetamol 1000 mg, outcome: 6.1 Participants with at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours.

The proportion of participants experiencing at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours with active treatment was 68% (100/147; range 61% to 76%).

The proportion of participants experiencing at least 50% pain relief with placebo was 13% (19/142; range 6% to 29%).

The RB of treatment compared with placebo was 4.9 (3.2 to 7.6), giving an NNT for at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours of 1.8 (1.6 to 2.2).

There was a significant difference between oxycodone 5 mg plus paracetamol 325 mg and oxycodone 10 mg plus paracetamol 650 mg (z = 4.15, P < 0.00006), and between oxycodone 10 mg plus paracetamol 650 mg and oxycodone 10 mg plus paracetamol 1000 mg (z = 3.14, P < 0.0019).

| Summary of results B: participants with ≥ 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours | |||||

|

Dose (mg) (Oxycodone/paracetamol) |

Studies | Participants |

Oxycodone/ paracetamol(%) |

Placebo (%) | NNT (95%CI) |

| 5/325 | 3 | 388 | 27 | 8 | 5.4 (3.9 to 8.8) |

| 10/650 | 10 | 1043 | 51 | 14 | 2.7 (2.4 to 3.1) |

| 10/1000 | 2 | 289 | 68 | 13 | 1.8 (1.6 to 2.2) |

Sensitivity analysis of primary outcome

Methodological quality

All studies scored three or more for quality, so no sensitivity analysis was carried out for this criterion.

Pain model dental versus other surgery

For this analysis there were sufficient data only for the oxycodone 10 mg plus paracetamol 650 mg dose (Analysis 5.1; Figure 2).

In the six studies in dental pain using oxycodone 10 mg with paracetamol 650 mg (Chang 2004a; Chang 2004b; Desjardins 2007; Fricke 1997; Malmstrom 2005; Malmstrom 2006) there were data from 673 participants.

The proportion of participants experiencing at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours with active treatment was 51% (252/496; range 28% to 59%).

The proportion of participants experiencing at least 50% pain relief with placebo was 6% (11/177; range 0% to 12%).

The RB of treatment compared with placebo was 6.8 (3.9 to 12) giving an NNT for at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours of 2.3 (2.0 to 2.6).

In the four studies in other types of surgery (mainly obstetric and gynaecological) using oxycodone 10 mg with paracetamol 650 mg (Johnson 1997; Palangio 2000; Sunshine 1993; Sunshine 1996), there were data from 370 participants.

The proportion of participants experiencing at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours with active treatment was 51% (93/184; range 32% to 90%).

The proportion of participants experiencing at least 50% pain relief with placebo was 20% (37/186; range 0% to 38%).

The RB of treatment compared with placebo was 2.5 (1.9 to 3.4) giving an NNT for at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours of 3.3 (2.5 to 4.7).

The NNT for at least 50% pain relief in these studies was lower (better) for dental studies than other types of surgery, but the difference was not statistically significant.

Trial size

Seven studies (eight active treatment arms, 934 participants) using oxycodone 10 mg plus paracetamol 650 mg, had more than 40 participants in each treatment arm (Daniels 2002; Johnson 1997; Litkowski 2005; Malmstrom 2005; Palangio 2000; Reines 1994; Sunshine 1993), and three studies (156 participants) had fewer than 40 in each treatment arm (Fricke 1997; Malmstrom 2006; Sunshine 1996). (In Daniels 2002, efficacy data from two centres were reported as separate sets of data‐ shown as Study A and Study B in 'Characteristics of included studies'.) There were insufficient data from small studies for this analysis.

Secondary outcome: Use of rescue medication

(Table 1; Summary of results C)

Thirteen studies reported on participants requiring rescue medication: one at 2 hours (Fricke 1997), nine at 6 hours (Chang 2004a; Desjardins 2007; Gammaitoni 2003; Johnson 1997; Korn 2004; Litkowski 2005; Malmstrom 2006; Reines 1994; Sunshine 1996), three at 8 hours (Johnson 1997; Palangio 2000; Sunshine 1993) and two at 24 hours (Korn 2004; Daniels 2002). Two studies (Cooper 1980); Malmstrom 2005) did not provide usable data on participants requiring rescue medication.

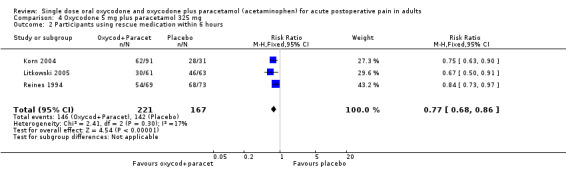

Oxycodone 5 mg plus paracetamol versus placebo

In three studies using oxycodone 5 mg plus paracetamol 325 mg (Korn 2004; Litkowski 2005; Reines 1994), there were data from 388 participants on the requirement for rescue medication at 6 hours (Analysis 4.2).

The proportion of participants requiring rescue medication after active treatment was 66% (146/221; range 49% to 78%).

The proportion of participants requiring rescue medication after placebo was 85% (142/167; range 73% to 93%).

The RB of treatment compared with placebo was 0.77 (0.68 to 0.86), giving an NNTp for rescue medication at 6 hours of 5.3 (3.7 to 9.3).

In one study using oxycodone 5 mg plus paracetamol 325 mg (Korn 2004) reporting participants using rescue medication over 24 hours, there were insufficient data for analysis.

Oxycodone 10 mg plus paracetamol

Eight studies using oxycodone 10 mg plus paracetamol 650 mg provided data on numbers of participants using rescue medication, one at 2 hours (Fricke 1997), five at 6 hours, and three at 8 hours.

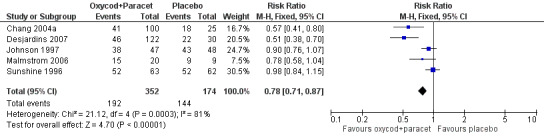

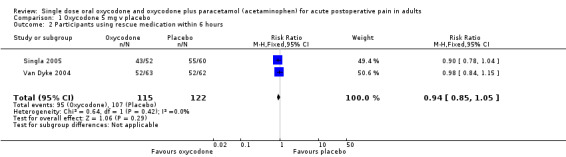

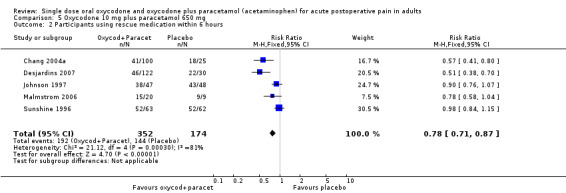

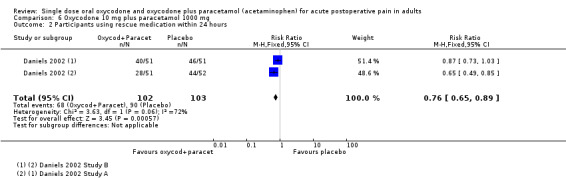

In five studies using oxycodone 10 mg plus paracetamol 650 mg (Chang 2004a; Desjardins 2007; Johnson 1997; Malmstrom 2006; Sunshine 1996), there were data from 526 participants on the requirement for rescue medication at 6 hours (Analysis 5.2; Figure 4).

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Oxycodone 10 mg plus paracetamol 650 mg, outcome: 2.3 Participants using rescue medication within 6 hours.

The proportion of participants requiring rescue medication after active treatment was 55% (192/352; range 38% to 83%).

The proportion of participants requiring rescue medication after placebo was 83% (144/174; range 72% to 100%).

The RB of treatment compared with placebo was 0.78 (0.71 to 0.87), giving an NNTp for rescue medication at 6 hours of 3.5 (2.8 to 4.9).

In three studies using oxycodone 10 mg plus paracetamol 650 mg(Johnson 1997; Palangio 2000; Sunshine 1993), there were data from 310 participants on the requirement for rescue medication at 8 hours (Analysis 5.3).

The proportion of participants requiring rescue medication after active treatment was 86% (133/154; range 73% to 93%).

The proportion of participants requiring rescue medication after placebo was 88% (138/156; range 73% to 100%).

The RB of treatment compared with placebo was 0.98 (0.90 to 1.1).

In one study (two active treatment arms) using oxycodone 10 mg plus paracetamol 1000 mg(Daniels 2002), there were data from 205 participants on the requirement for rescue medication at 24 hours. (In Daniels 2002, rescue medication data from two centres were reported as separate sets of data ‐ shown as 'Study A' and 'Study B' in the 'Characteristics of included studies'.) (Analysis 6.2).

The proportion of participants requiring rescue medication after active treatment was 67% (68/102; range 55% to 78%).

The proportion of participants requiring rescue medication after placebo was 87% (90/103; range 85% to 90%).

The RB of treatment compared with placebo was 0.76 (0.65 to 0.89) giving an NNTp for rescue medication at 24 hours of 4.8 (3.1 to 10).

| Summary of results C: participants using rescue medication | |||||

| Time assessed | Studies | Participants |

Oxycodone/ paracetamol (%) |

Placebo (%) | NNTp (95%CI) |

| 6 hours (5/325 mg) | 3 | 388 | 66 | 85 | 5.3 (3.7 to 9.3) |

| 6 hours (10/650 mg) | 5 | 526 | 55 | 83 | 3.5 (2.8 to 4.9) |

| 8 hours (10/650 mg) | 3 | 310 | 86 | 88 | Not calculated |

| 24 hours (10/1000 mg) | 1 | 205 | 67 | 87 | 4.8 (3.1 to 10) |

Ten studies reported on the median time to use of rescue medication (Summary of results D).

The weighted mean of the median time to use of rescue medication was 4.3 hours for oxycodone 5 mg plus paracetamol 325 mg (388 participants) (Korn 2004; Litkowski 2005; Reines 1994), 9.8 hours for oxycodone 10 mg plus paracetamol 650 mg (727 participants) (Chang 2004a; Chang 2004b; Desjardins 2007; Malmstrom 2005; Malmstrom 2006; Palangio 2000), and 8.7 hours for oxycodone 10 mg plus paracetamol 1000 mg (206 participants) (Daniels 2002). The corresponding median times to use of rescue medication with placebo were 2.0, 1.5 and 1.1 hours respectively. (In Daniels 2002, rescue medication data from two centres were reported as separate sets of data ‐ shown as 'Study A' and 'Study B' in the 'Characteristics of included studies'.)

| Summary of results D: weighted mean of median time to use of rescue medication | |||||

| Dose (mg) | Studies | Participants |

Oxycodone/ paracetamol (h) |

Placebo (h) | |

| 5/325 | 3 | 388 | 4.3 | 2.0 | |

| 10/650 | 6 | 727 | 9.8 | 1.5 | |

| 10/1000 | 1 | 206 | 8.7 | 1.1 | |

Secondary outcome: Adverse events

(Table 2; Summary of results E)

Twelve studies reported the number of participants with one or more adverse event for each treatment arm in single dose studies (Chang 2004a; Cooper 1980; Daniels 2002; Fricke 1997; Gammaitoni 2003; Korn 2004; Litkowski 2005; Malmstrom 2005; Malmstrom 2006; Palangio 2000; Reines 1994; Sunshine 1996). The time over which the information was collected was not always explicitly stated and varied between trials. There were no specific single dose adverse event data in the multiple dose studies, and it was not clear whether reported adverse events occurred during the single or multiple dose phases. Few studies reported whether adverse event data continued to be collected after rescue medication had been taken. In some cases, the rescue medication was a further dose of the active drug, or was not specified. Adverse events, where described, were mild to moderate in severity, and predominantly nausea, vomiting, dizziness and somnolence. There was no report of a serious adverse event in a single dose study or during the single dose phase of a multiple dose study.

Oxycodone 5 mg plus paracetamol versus placebo

In three studies using oxycodone 5 mg plus paracetamol 325 mg (Korn 2004; Litkowski 2005; Reines 1994), there were data from 388 participants (Analysis 4.3).

The proportion of participants having an adverse event after active treatment was 48% (107/221; range 28% to 65%).

The proportion of participants having an adverse event after placebo was 26% (44/167; range 11% to 48%).

The RR of treatment compared with placebo was 1.6 (1.2 to 2.1), giving an NNH of 4.5 (3.2 to 7.9).

In one study using oxycodone 5 mg plus paracetamol 500 mg (Cooper 1980) and in one study using oxycodone 5 mg plus paracetamol 1000 mg(Cooper 1980) there were insufficient data for analysis of this outcome.

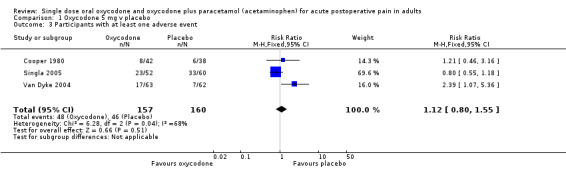

Oxycodone 10 mg plus paracetamol versus placebo

In one study using oxycodone 10 mg plus paracetamol 325 mg (Gammaitoni 2003) there were insufficient data for analysis.

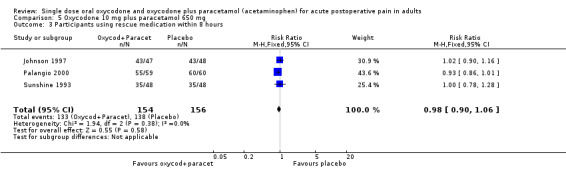

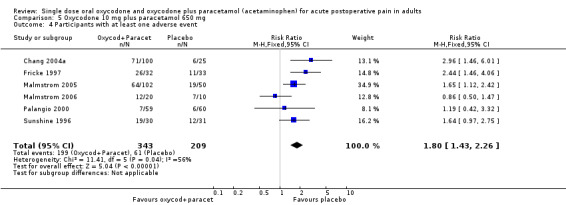

In six studies using oxycodone 10 mg plus paracetamol 650 mg (Chang 2004a; Fricke 1997; Malmstrom 2005; Malmstrom 2006; Palangio 2000; Sunshine 1996), there were data from 552 participants (Analysis 5.4; Figure 5).

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Oxycodone 10 mg plus paracetamol 650 mg, outcome: 2.2 Participants with at least one adverse event.

The proportion of participants having an adverse event after active treatment was 58% (199/343; range 12% to 81%).

The proportion of participants having an adverse event after placebo was 29% (61/209; range 10% to 70%).

The RR of treatment compared with placebo was 1.8 (1.4 to 2.3), giving an NNH of 3.5 (2.7 to 4.8).

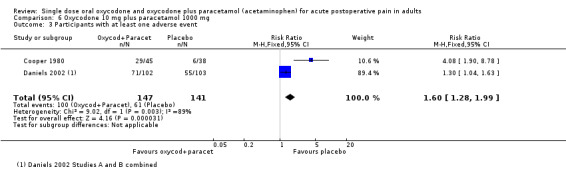

In two studies using oxycodone 10 mg plus paracetamol 1000 mg (Cooper 1980; Daniels 2002) there were data from 288 participants (Analysis 6.3).

The proportion of participants having an adverse event after active treatment was 68% (100/147; range 64% to 70%).

The proportion of participants having an adverse event after placebo was 43% (61/141; range 16% to 53%).

The RR of treatment compared with placebo was 1.6 (1.3 to 2.0), giving an NNH of 4.0 (2.8 to 7.3).

No clear dose response for this outcome was seen in these studies.

| Summary of results E: participants with at least one adverse event | |||||

|

Dose (mg) (Oxycodone/paracetamol) |

Studies | Participants |

Oxycodone/ paracetamol (%) |

Placebo (%) | NNH (95%CI) |

| 5/325 | 3 | 388 | 48 | 26 | 4.5 (3.2 to 7.9) |

| 10/650 | 6 | 552 | 58 | 29 | 3.5 (2.7 to 4.8) |

| 10/1000 | 2 | 288 | 68 | 43 | 4.0 (2.8 to 7.3) |

Secondary outcome: Withdrawals

(Table 2)

Exclusions may not be of any particular consequence in single dose acute pain studies, where most exclusions result from participants not having moderate or severe pain (McQuay 1982).

Participants who took rescue medication were classified as withdrawals due to lack of efficacy, and details are reported under 'Use of rescue medication' above. Withdrawals for other reasons (e.g., adverse events, protocol violations) and exclusions were not reported consistently.

Apart from lack of efficacy, in most studies, most reported withdrawals were due to adverse events. No withdrawal data were given in one study (Chang 2004a) and in one multi‐dose study (Desjardins 2007) there were no data specifically from the single dose phase. No withdrawals or exclusions were reported in seven studies (Chang 2004b; Daniels 2002; Fricke 1997; Korn 2004; Malmstrom 2006; Palangio 2000; Sunshine 1993).

In active treatment arms, in one study (Reines 1994) there was one withdrawal for nausea, and in one study (Desjardins 2007) there was one exclusion for syncope, headache and vomiting (but the time of withdrawal was not stated). There was only one withdrawal because of an adverse event in a placebo arm (one participant with severe headache in Litkowski 2005).

Withdrawals for other reasons, such as loss to follow up, were generally rare. A number of studies (e.g., Cooper 1980; Gammaitoni 2003; Gimbel 2004; Reines 1994) reported exclusions from efficacy analyses due to protocol violations and invalid data, including insufficient baseline pain, not taking the medication, vomiting within 1 hour, and use of rescue medication within 1 hour.

See also Table 1; Table 2; Analysis 1.1; Analysis 1.2; Analysis 1.3; Analysis 2.1; Analysis 3.1; Analysis 4.1; Analysis 4.2; Analysis 4.3; Analysis 5.1; Analysis 5.2; Analysis 5.3; Analysis 5.4; Analysis 6.1; Analysis 6.2; Analysis 6.3.

1. Summary of outcomes: analgesia and rescue medication.

| Analgesia | Rescue medication | |||||

| Study ID | Treatment | PI or PR | Number with 50% PR | PGR: v good or excellent | Median time to use (h) | % using |

| Aqua 2007 | (1) Oxycodone 15 mg, n = 83 (2) Oxymorphone 10 mg, n = 82 (3) Oxymorphone 20 mg, n = 81 (4) Placebo, n = 85 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 10.5 (4) 8.1 |

(1) 39/83 (4) 28/85 |

No single dose data | No single dose data | (1) 32 (4) 41 |

| Chang 2004a | (1) Oxycodone 10 mg + paracetamol 650 mg, n = 100 (2) Etoricoxib 120 mg, n = 100 (3) Placebo, n = 25 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 12.1 (3) 4.1 |

(1) 56/100 (3) 3/25 |

(1) 43/97 (3) 1/24 |

(1) 7.4 (3) 1.5 |

at 6 h: (1) 41 (3) 72 |

| Chang 2004b | (1) Oxycodone 10 mg + paracetamol 650 mg, n = 120 (2) Rofecoxib 50 mg, n = 121 (3) Placebo, n = 30 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 11.3 (3) 3.1 |

(1) 61/120 (3) 2/30 |

(1) 56/116 (3) 0/30 |

(1) 5.1 (3) 1.6 |

No data |

| Cooper 1980 | (1) Oxycodone 5 mg, n = 42 (2) Oxycodone 5 mg + paracetamol 500 mg, n = 45 (3) Oxycodone 5 mg + paracetamol 1000 mg, n = 40 (4) Oxycodone 10 mg + paracetamol 1000 mg, n = 45 (5) Paracetamol 500 mg, n = 37 (6) Placebo, n = 38 |

TOTPAR 4: (1) 4.8 (2) 7.5 (3) 8.1 (4) 9.4 (5) 5.1 (6) 4.8 |

(1) 12/42 (2) 23/45 (3) 22/40 (4) 30/45 (5) 12/37 (6) 11/38 |

No usable data | Mean: (1) 2.8 (2) 3.5 (3) 3.2 (4) 3.4 (5) 2.8 (6) 2.5 |

No data |

| Daniels 2002 | Study A: (1) Oxycodone 10 mg + paracetamol 1000 mg, n = 51 (2) Valdecoxib 20 mg, n = 52 (3) Valdecoxib 40 mg, n = 50 (4) Placebo, n = 52 Study B: (1) Oxycodone 10 mg + paracetamol 1000 mg, n = 51 (2) Valdecoxib 20 mg, n = 49 (3) Valdecoxib 40 mg, n = 50 (4) Placebo, n = 51 |

SPID 6: Study A (1) 8.7 (4) 1.4 Study B (1) 7.3 (4) 1.0 |

Study A: (1) 39/51 (4) 5/52 Study B: (1) 31/51 (4) 5/52 |

No usable data | Study A: (1) 11.3 (4) 1.1 Study B: (1) 6.1 (4) 1.1 |

at 24 h: Study A: (1) 55 (4) 85 Study B: (1) 78 (4) 90 |

| Desjardins 2007 | (1) Oxycodone 10 mg + paracetamol 650 mg, n = 122 (2) Rofecoxib 50 mg, n = 118 (3) Placebo, n = 30 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 12.8 (3) 3.9 |

(1) 72/122 (3) 3/30 |

No usable data | (1) >24 (3) 1.83 |

at 6 h: (1) 38 (3) 73 |

| Fricke 1997 | (1) Oxycodone 10 mg + paracetamol 650 mg, n = 32 (2) Bromfenac 25 mg, n = 30 (3) Bromfenac 50 mg, n = 33 (4) Placebo, n = 33 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 9.2 (4) 1.4 |

(1) 13/32 (4) 0/33 |

(1) 8/32 (4) 3/33 |

No data | at 2 h: (1) 25 (4) 85 |

| Gammaitoni 2003 | (1) Oxycodone 10 mg + paracetamol 325 mg, n = 59 (2) OxycodoneCR 20 mg, n = 61 (3) Placebo, n = 30 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 8.1 (2) 6.0 (3) 1.8 |

(1) 18/55 (2) 12/56 (3) 0/30 |

(1) 14/55 (2) 13/56 (3) 2/30 |

(1) 4.5 (2) 2.75 (3) 1.3 |

at 6 h: (1) 48 (2) 51 (3) 83 |

| Gimbel 2004 | (1) Oxycodone 10 mg, n = 60 (2) Oxymorphone 10 mg, n = 59 (3) Oxymorphone 20 mg, n = 59 (4) Oxymorphone 30 mg, n = 65 (5) Placebo, n = 57 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 6.9 (5) 5.8 |

(1) 15/55 (5) 9/44 |

(1) 15/55 (5) 9/44 |

No usable data | at 8 h: (1) 42 (5) 47 |

| Johnson 1997 | (1) Oxycodone 10 mg + paracetamol 650 mg, n = 47 (2) Bromfenac 50 mg, n = 47 (3) Bromfenac 100 mg, n = 48 (4) Ibuprofen 400 mg, n = 48 (5) Placebo, n = 48 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 9.7 (5) 5.8 |

(1) 20/47 (5) 10/48 |

(1) 33/47 (5) 17/47 |

No data | at 6 h: (1) 81 (5) 89 at 8 h: (1) 92 (5) 90 |

| Korn 2004 | (1) Oxycodone 5 mg + paracetamol 325 mg , n = 91 (2) Rofecoxib 50 mg, n = 90 (3) Placebo, n = 31 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 5.9 (3) 1.9 |

(1) 19/91 (3) 0/31 |

(1) 17/91 (3) 1/31 |

(1) 3.3 (3) 1.7 |

at 6 h: (1) 68 (3) 90 at 24 h: (1) 95 (3) 97 |

| Litkowski 2005 | (1) Oxycodone 5 mg + paracetamol 325 mg, n = 61 (2) Hydromorphone 7.5 mg + paracetamol 500 mg, n = 63 (3) Ibuprofen 400 mg + oxycodone 5 mg, n = 62 (4) Placebo, n = 63 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 9.5 (4) 5.1 |

(1) 25/61 (4) 10/63 |

No usable data | (1) > 6 (4) 2.14 |

at 6 h: (1) 49 (4) 73 |

| Malmstrom 2005 | (1) Oxycodone 10 mg + paracetamol 650 mg, n = 102 (2) Etoricoxib 120 mg, n = 100 (3) Codeine 60 mg + paracetamol 600 mg, n = 50 (4) Placebo, n = 50 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 10.1 (4) 2.4 |

(1) 45/102 (4) 1/50 |

(1) 47/102 (4) 3/50 |

(1) 5.3 (4) 1.7 |

at 6 h: (1) 57 (4) no data |

| Malmstrom 2006 | (1) Oxycodone 10 mg + paracetamol 650 mg, n = 20 (2) Lidocaine IV 4 mg/kg, n = 20 (3) Active placebo, n = 10 (4) Placebo, n = 10 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 6.8 (4) 0.8 |

(1) 5/20 (4) 0/9 |

No data | (1) 3.1 (4) 1.2 |

at 6 h: (1) 75 (4) 100 |

| Palangio 2000 | (1) Oxycodone 10 mg + paracetamol 650 mg, n = 59 (2) Hydrocodone 15 mg + ibuprofen 400 mg, n = 61 (3) Placebo, n = 60 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 8.0 (3) 1.4 |

(1) 19/59 (3) 0/60 |

No usable data | (1) 3.75 (3) 1.00 |

at 8 h: (1) 93 (3) 100 |

| Reines 1994 | (1) Oxycodone 5 mg + paracetamol 325 mg, n = 69 (2) Ketorolac 10 mg, n = 76 (3) Placebo, n = 73 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 6.3 (3) 3.1 |

(1) 16/69 (4) 4/73 |

No usable data | (1) 4.05 (3) 1.94 |

at 6 h: (1) 78 (3) 93 |

| Singla 2005 | (1) Oxycodone 5 mg, n = 52 (2) Oxycodone 5 mg + ibuprofen 400 mg, n = 169 (3) Ibuprofen 400 mg, n = 175 (4) Placebo, n = 60 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 8.6 (4) 6.4 |

(1) 19/52 (4) 14/60 |

No usable data | (1) 2.50 (4) 2.28 |

at 6 h: (1) 83 (4) 92 |

| Sunshine 1993 | (1) Oxycodone 10 mg + paracetamol 650 mg, n = 48 (2) Paracetamol 650 mg, n = 48 (3) Ketoprofen 50 mg, n = 48 (4) Ketoprofen 100 mg, n = 48 (5) Placebo, n = 48 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 12.4 (5) 8.8 |

(1) 27/48 (5) 18/48 |

No usable data | No usable data | (1) 73 (5) 73 |

| Sunshine 1996 | (1) Oxycodone 15 mg, n = 31 (2) Oxycodone 10 mg + paracetamol 650 mg, n = 30 (3) Oxycodone CR 10 mg, n = 30 (4) Oxycodone CR 20 mg, n = 30 (5) Oxycodone CR 30 mg, n = 30 (6) Placebo, n = 31 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 15.4 (2) 18.5 (3) 11.7 (4) 15.6 (5) 16.3 (6) 7.5 |

(1) 22/30 (2) 27/30 (3) 16/30 (4) 22/30 (5) 24/30 (6) 9/30 |

No usable data | No usable data | at 12 h: (1) 73 (2) 83 (3) 57 (4) 50 (5) 60 (6) 83 |

| Van Dyke 2004 | (1) Oxycodone 5 mg, n = 63 (2) Oxycodone 5 mg + ibuprofen 400 mg, n = 187 (3) Ibuprofen 400 mg, n = 186 (4) Placebo, n = 62 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 4.3 (4) 4.2 |

(1) 8/63 (4) 7/62 |

No usable data | (1) 2.1 (4) 2.0 |

at 6 h: (1) 83 (4) 84 |

2. Summary of outcomes: adverse events and withdrawals.

| Adverse events | Withdrawals | ||||

| Study ID | Treatment | Any | Serious | Adverse event | Other |

| Aqua 2007 | (1) Oxycodone 15 mg, n = 83 (2) Oxymorphone 10 mg, n = 82 (3) Oxymorphone 20 mg, n = 81 (4) Placebo, n = 85 |

No single dose data, but reported events were of mild to moderate severity | No single dose data | (1) 4/83 (4) 4/85 |

(1) 3/83 (4) 1/85 |

| Chang 2004a | (1) Oxycodone 10 mg + paracetamol 650 mg, n = 100 (2) Etoricoxib 120 mg, n = 100 (3) Placebo, n = 25 |

At 24 h: (1) 71/100 (3) 6/25 |

None | None reported | None reported |

| Chang 2004b | (1) Oxycodone 10 mg + paracetamol 650 mg, n = 120 (2) Rofecoxib 50 mg, n = 121 (3) Placebo, n = 30 |

No single dose data | No single dose data | None | None |

| Cooper 1980 | (1) Oxycodone 5 mg, n = 42 (2) Oxycodone 5 mg + paracetamol 500 mg, n = 45 (3) Oxycodone 5 mg + paracetamol 1000 mg, n = 40 (4) Oxycodone 10 mg + paracetamol 1000 mg, n = 45 (5) Paracetamol 500 mg, n = 37 (6) Placebo, n = 38 |

Before rescue medication: (1) 8/42 (2) 21/45 (3) 19/40 (4) 29/45 (5) 3/37 (6) 6/38 |

None reported | None reported | Total of 51 pts excluded from analyses: 21 lost to follow up, 10 did not take medication, 20 had protocol violations |

| Daniels 2002 | Study A: (1) Oxycodone 10 mg + paracetamol 1000 mg, n = 51 (2) Valdecoxib 20 mg, n = 52 (3) Valdecoxib 40 mg, n = 50 (4) Placebo, n = 52 Study B: (1) Oxycodone 10 mg + paracetamol 1000 mg, n = 51 (2) Valdecoxib 20 mg, n = 49 (3) Valdecoxib 40 mg, n = 50 (4) Placebo, n = 51 |

At 24 h: Study A + B (1) 71/102 (4) 55/103 Most mild to moderate in severity |

None reported | None | None |

| Desjardins 2007 | (1) Oxycodone 10 mg + paracetamol 650 mg, n = 122 (2) Rofecoxib 50 mg, n = 118 (3) Placebo, n = 30 |

No single dose data | None | (1) I pt had syncope, headache, vomiting ‐ time of withdrawal not given | (1) 1 pt had protocol violation |

| Fricke 1997 | (1) Oxycodone 10 mg + paracetamol 650 mg, n = 32 (2) Bromfenac 25 mg, n = 30 (3) Bromfenac 50 mg, n = 33 (4) Placebo, n = 33 |

At 8 h: (1) 26/32 (4) 11/33 |

None | None | None reported |

| Gammaitoni 2003 | (1) Oxycodone 10 mg + paracetamol 325 mg, n = 59 (2) Oxycodone CR 20 mg, n = 61 (3) Placebo, n = 30 |

At 6 h: (1) 26/59 (2) 34/61 (3) 5/30 |

None | Vomiting in 1st hr: (1) 4/59 (2) 5/61 (3) 0/30 so excluded from efficacy analysis |

None reported |

| Gimbel 2004 | (1) Oxycodone 10 mg, n = 60 (2) Oxymorphone 10 mg, n = 59 (3) Oxymorphone 20 mg, n = 59 (4) Oxymorphone 30 mg, n = 65 (5) Placebo, n = 57 |

Single dose phase: (1) 16/60 (5) no data |

2 pts, but treatment group not given. No further details | (1) 0/60 (5) 2/57 |

None reported 42 pts had invalid data (early remedication or vomiting) or protocol violations and were excluded from the efficacy analysis |

| Johnson 1997 | (1) Oxycodone 10 mg + paracetamol 650 mg, n = 47 (2) Bromfenac 50 mg, n = 47 (3) Bromfenac 100 mg, n = 48 (4) Ibuprofen 400 mg, n = 48 (5) Placebo, n = 48 |

At 8 h: CNS AEs (mostly somnolence, dizziness): (1) 10/47 (5) 2/48 |

Unclear, probably none in single dose phase | None reported | 2 protocol violations, one each in (2) and (5) |

| Korn 2004 | (1) Oxycodone 5 mg + paracetamol 325 mg , n = 91 (2) Rofecoxib 50 mg, n = 90 (3) Placebo, n = 31 |

At 14 days: (1) 59/91 (2) 46/90 (3) 15/31 |

None reported | None | None |

| Litkowski 2005 | (1) Oxycodone 5 mg + paracetamol 325 mg, n = 61 (2) Hydromorphone 7.5 mg + paracetamol 500 mg, n = 63 (3) Ibuprofen 400 mg + oxycodone 5 mg, n = 62 (4) Placebo, n = 63 |

At 6 h: (1) 17/61 (4) 7/63 |

None | (4) 1/63 (severe headache) | None reported |

| Malmstrom 2005 | (1) Oxycodone 10 mg + paracetamol 650 mg, n = 102 (2) Etoricoxib 120 mg, n = 100 (3) Codeine 60 mg + paracetamol 600 mg, n = 50 (4) Placebo, n = 50 |

At 24 h (unclear, possibly at 7 days): (1) 64/102 (2) 40/100 (3) 30/50 (4) 19/50 |

None | None reported | (1) 1 pt did not return for post study follow up ‐ all other data analysed |

| Malmstrom 2006 | (1) Oxycodone 10 mg + paracetamol 650 mg, n = 20 (2) Lidocaine IV 4 mg/kg, n = 20 (3) Active placebo, n = 10 (4) Placebo, n = 10 |

At 6 h: (1) 12/20 (4) 7/10 |

None reported | None | None (4) 1/10 had invalid data (inadequate baseline pain) so excluded from efficacy analysis |

| Palangio 2000 | (1) Oxycodone 10 mg + paracetamol 650 mg, n = 59 (2) Hydrocodone 15 mg + ibuprofen 400 mg, n = 61 (3) Placebo, n = 60 |

At 8 h: (1) 7/59 (3) 6/60 |

None | None | None |

| Reines 1994 | (1) Oxycodone 5 mg + paracetamol 325 mg, n = 69 (2) Ketorolac 10 mg, n = 76 (3) Placebo, n = 73 |

At 6 h: (1) 31/69 (3) 22/73 Most mild to moderate in severity |

None reported | (1) 1/69 (nausea) (3) 0/73 |

None reported 24 pts had protocol violations or inadequate baseline pain so were excluded from analyses |

| Singla 2005 | (1) Oxycodone 5 mg, n = 52 (2) Oxycodone 5 mg + ibuprofen 400 mg, n = 169 (3) Ibuprofen 400 mg, n = 175 (4) Placebo, n = 60 |

At 6 h: (1) 23/52 (4) 33/60 Most mild to moderate in severity |

(1) 3/52 (4) 1/60 |

(1) 1/52 (vomiting) (4) 0/60 |

None reported |

| Sunshine 1993 | (1) Oxycodone 10 mg + paracetamol 650 mg, n = 48 (2) Paracetamol 650 mg, n = 48 (3) Ketoprofen 50 mg, n = 48 (4) Ketoprofen 100 mg, n = 48 (5) Placebo, n = 48 |

No single dose data | "No cases of possible clinical concern" (multiple dose included) | None | None |

| Sunshine 1996 | (1) Oxycodone 15 mg, n = 31 (2) Oxycodone 10 mg + paracetamol 650 mg, n = 30 (3) Oxycodone CR 10 mg, n = 30 (4) Oxycodone CR 20 mg, n = 30 (5) Oxycodone CR 30 mg, n = 30 (6) Placebo, n = 31 |

Before rescue medication: (1) 22/31 (2) 19/30 (3) 14/30 (4) 15/30 (5) 22/30 (6) 12/31 |

None | (1) 1 pt vomited within 1 h, so excluded from efficacy analysis | (6) 1 pt had protocol violation, so excluded from efficacy analysis |

| Van Dyke 2004 | (1) Oxycodone 5 mg, n = 63 (2) Oxycodone 5 mg + ibuprofen 400 mg, n = 187 (3) Ibuprofen 400 mg, n = 186 (4) Placebo, n = 62 |

At 6 h: (1) 17/63 (4) 7/62 |

None | None | One pt in (2) had no post baseline efficacy data so excluded from efficacy analysis |

pt ‐ participant

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oxycodone 5 mg v placebo, Outcome 1 Participants with at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oxycodone 5 mg v placebo, Outcome 2 Participants using rescue medication within 6 hours.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oxycodone 5 mg v placebo, Outcome 3 Participants with at least one adverse event.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Oxycodone 15 mg versus placebo, Outcome 1 Participants with at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Oxycodone CR versus placebo, Outcome 1 Participants with at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours.

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Oxycodone 5 mg plus paracetamol 325 mg, Outcome 1 Participants with at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Oxycodone 5 mg plus paracetamol 325 mg, Outcome 2 Participants using rescue medication within 6 hours.

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Oxycodone 5 mg plus paracetamol 325 mg, Outcome 3 Participants with at least one adverse event.

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Oxycodone 10 mg plus paracetamol 650 mg, Outcome 1 Participants with at least 50% pain relief over 4‐6 hours.

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Oxycodone 10 mg plus paracetamol 650 mg, Outcome 2 Participants using rescue medication within 6 hours.

5.3. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Oxycodone 10 mg plus paracetamol 650 mg, Outcome 3 Participants using rescue medication within 8 hours.

5.4. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Oxycodone 10 mg plus paracetamol 650 mg, Outcome 4 Participants with at least one adverse event.

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Oxycodone 10 mg plus paracetamol 1000 mg, Outcome 1 Participants with at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours.

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Oxycodone 10 mg plus paracetamol 1000 mg, Outcome 2 Participants using rescue medication within 24 hours.

6.3. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Oxycodone 10 mg plus paracetamol 1000 mg, Outcome 3 Participants with at least one adverse event.

Discussion

This updated review includes 14 additional studies, but excluded one study (Young 1979) that had been included in the previous version. Results are now available from 2641 participants in 20 studies, compared with 769 in the seven studies in the previous review. All the studies were of adequate methodological quality to minimize bias. The additional data available in this updated review results in substantial changes to measures of efficacy and harm compared with the previous review, where most comparisons were based on small numbers of participants.

Most of the data were for the combination of oxycodone 10 mg with paracetamol 650 mg, where there were more than 1000 participants in comparisons with placebo. Results for other dose combinations and for oxycodone alone are based on many fewer participants and should be interpreted with caution.

As before, no benefit could be shown of oxycodone 5 mg alone over placebo, but oxycodone 15 mg was again shown to be superior to placebo with NNT for at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours compared to placebo of 4.6 (2.9 to 11) based on two trials, a higher (worse) NNT than in the previous review where it was calculated as 2.4 (1.5 to 4.9) based on a single trial. This underlines the fact that small data sets do not accurately measure effect size (Moore 1998). About half of the participants treated with oxycodone 15 mg achieved at least 50% pain relief, compared with about a third treated with placebo. There were insufficient data for analysis of oxycodone 10 mg.

In comparison with placebo, at doses of oxycodone 5 mg plus paracetamol 325 mg, oxycodone 10 mg plus paracetamol 650 mg, and oxycodone 10 mg plus paracetamol 1000 mg, the NNTs were 5.4 (3.9 to 8.8), 2.7 (2.4 to 3.1), and 1.8 (1.6 to 2.2) respectively. For the combination of oxycodone 10 mg plus paracetamol 650 mg there were sufficient numbers (over 1000 participants) to be confident of the result. Again, this comparison differs from the findings in the previous version of the review, with much smaller numbers, in which NNTs were about 2.5 in each case.

There now appears to be a dose response. As increased efficacy is associated with higher dosages of both oxycodone and paracetamol, it is not clear how much the increase in efficacy is due to either drug individually, or is due to their use in combination (Edwards 2002). There were insufficient data for direct comparison of efficacy of oxycodone plus paracetamol with the same dose of oxycodone alone (as there were few studies using oxycodone alone, and fewer studies which included active treatment arms of both oxycodone alone and oxycodone plus paracetamol at the same dose of oxycodone). However, there was sufficient information for indirect comparison of oxycodone 5 mg and oxycodone 5 mg plus paracetamol 325 mg; oxycodone 5 mg was no more effective than placebo, but the NNT for at least 50% pain relief for oxycodone 5 mg plus paracetamol 325 mg was 5.4.

Indirect comparisons of NNTs for at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours in reviews of other analgesics using identical methods indicate that oxycodone 15 mg, and oxycodone 5 mg plus paracetamol 325 mg, have similar efficacy to aspirin 600 or 650 mg at 4.4 (4.0 to 4.9) (Oldman 1999) or paracetamol 600 or 650 mg at 4.6 (3.9 to 5.5.) (Toms 2008). Oxycodone 10 mg plus paracetamol 650 mg has equivalent efficacy to naproxen 500 mg (2.7 (2.3 to 3.3) (Derry C 2009a), ibuprofen 400 mg (2.5 (2.4 to 2.6)), (Derry C 2009b), lumiracoxib 400 mg (2.7 (2.2 to 3.5), Roy 2007) and celecoxib 400 mg (2.5 (2.2 to 2.9) (Derry 2008), and is better than paracetamol 1000 mg (3.6 (3.2 to 4.1), Toms 2008). Based on very limited data, oxycodone 10 mg plus paracetamol 1000 mg had equivalent efficacy to rofecoxib 50 mg (2.2 (2.0 to 2.5) (Barden 2005) and etoricoxib 120 mg (1.9 (1.6 to 2.1), (Clarke 2009). A current listing of reviews of analgesics in the single dose postoperative pain model can be found at www.medicine.ox.ac.uk/bandolier.

Indirect comparison of oxycodone plus paracetamol with codeine plus paracetamol (Toms 2009) suggests that paracetamol 650 mg combined with oxycodone 10 mg (NNT 2.7 (2.4 to 3.1)) provides better pain relief than when combined with codeine 60 mg (NNT 3.9 (3.3 to 4.7)) (z = 3.27; P < 0.001). This result is not surprising, since oxycodone 10 mg is 2 to 3 times stronger than codeine 60 mg, based on equivalent doses of morphine (Twycross 2006). Paracetamol 1000 mg plus oxycodone 10 mg (NNT 1.8 (1.6 to 2.2)) is very similar to paracetamol 1000 mg plus codeine 60 mg (NNT 2.2 (1.8 to 2.9)). However, there are many fewer participants providing data on the efficacy of oxycodone 10 mg with paracetamol 1000 mg or codeine 60 mg with paracetamol 800 to 1000 mg than is available for the corresponding doses of oxycodone or codeine when combined with paracetamol 600 to 650 mg (Summary of Discussion A).

| Summary of discussion A: comparison of oxycodone plus paracetamol with codeine plus paracetamol | |||||

| Treatment | Studies | Participants | Active (%) | Placebo (%) | NNT (95% CI) |

| Oxycodone/paracetamol 10/650 mg | 10 | 1043 | 51 | 14 | 2.7 (2.4 to 3.1) |

| Codeine/paracetamol 60/600‐650 mg | 17 | 1413 | 43 | 17 | 3.9 (3.3 to 4.7) |

| Oxycodone/paracetamol 10/1000 mg | 2 | 289 | 68 | 13 | 1.8 (1.6 to 2.2) |

| Codeine/paracetamol 60/800‐1000 mg | 3 | 192 | 53 | 7 | 2.2 (1.8 to 2.9) |

No sensitivity analyses could be carried out for trial quality (all studies adequate) or size (insufficient studies of small size). It was possible to compare the primary outcome in dental versus other surgery for oxycodone 10 mg plus paracetamol 650 mg, but no significant difference was found.

A controlled release formulation of oxycodone was used in two studies of oxycodone alone; in one study (Gammaitoni 2003) in dental pain oxycodone was used at one dose only (oxycodone CR 20 mg), and in one study (Sunshine 1996) in abdominal/gynaecological surgery pain oxycodone was used at three doses (oxycodone CR 10 mg, oxycodone CR 20 mg, oxycodone CR 30 mg). There are insufficient data to comment on the relative efficacy or harm of oxycodone CR in comparison with oxycodone.

It has been suggested that data on use of rescue medication, whether as a proportion of participants using it, or the median time to use of it, might be helpful both in assessing the usefulness of an analgesic, and possibly also in distinguishing between different doses (Moore 2005). There was limited information on which to base a conclusion, but there may be a dose response for the numbers of participants using rescue medication at 6 hours after treatment with oxycodone 5 mg plus paracetamol 325 mg or oxycodone 10 mg plus paracetamol 650 mg, with the NNTp values of 5.3 and 3.5 respectively.

The median time to use of rescue medication in the studies of oxycodone plus paracetamol did appear to be dose‐dependent, (about 4 hours for oxycodone 5 mg plus paracetamol 325 mg, about 10 hours for oxycodone 10 mg plus paracetamol 650 mg compared with about 2 hours for placebo). This relatively long duration of action for the higher dose compares favourably with analgesics such as paracetamol (alone) where the median time is under 4 hours (Toms 2008). There was insufficient data for further analysis of the trials in this review. The full implications of the importance of remedication as an outcome awaits completion of other reviews, allowing examination of a substantial body of evidence.

Reporting of data for adverse events, withdrawals (other than lack of efficacy) or exclusions, and handling of missing data was not always complete. Adverse events were collected using various methods (questioning, patient diary) over different periods of time. This may have included periods after the use of rescue medication, which may cause its own adverse events. A dose of the active treatment was used as rescue medication in some studies. Poor reporting of adverse events in acute pain trials has been noted before (Edwards 1999). The usefulness of single dose studies for assessing adverse events is questionable, but it is nonetheless reassuring that serious adverse events and adverse event withdrawals were rare. Significantly more participants experienced at least one adverse event with oxycodone plus paracetamol than placebo, with NNHs of 4.5, 3.5 and 4.0 for oxycodone 5 mg plus paracetamol 325 mg, oxycodone 10 mg plus paracetamol 650 mg, and oxycodone 10 mg plus paracetamol 1000 mg respectively. Where specific adverse events were reported, they were those which might be expected following a surgical procedure under anaesthetic, and/or treatment with an opioid drug or paracetamol. The earlier review considered individual adverse events, based on very limited data which was acknowledged as not being robust. We decided not to analyse individual adverse events because the limited amount of information and inconsistencies of reporting could give misleading results. Long‐term, multiple dose studies should be used for meaningful analysis of adverse events since, even in acute pain settings, analgesics are likely to be used in multiple doses.

Lack of information about withdrawals or exclusions may have led to an overestimate of efficacy, but the effect is probably not significant because it is as likely to be related to poor reporting as poor methods. In single dose studies most exclusions occur for protocol violations such as failing to meet baseline pain requirements, or failing to return for post treatment visits after the acute pain results are concluded. Where patients are treated with a single dose of medication and observed, often "on site" for the duration of the trial, it might be considered unnecessary to report on "withdrawals" if there were none. For missing data it has been shown that over the 4 to 6 hour period, there is no difference between baseline observation carried forward, which gives the more conservative estimate, and last observation carried forward (Moore 2005).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The earlier review had insufficient data to guide clinical practice. In this updated review the most robust evidence is for oxycodone plus paracetamol, with a clear dose response for both the proportion of patients achieving at least 50% pain relief and time to remedication. Of several combinations of oxycodone and paracetamol, most data are available for oxycodone 10 mg plus paracetamol 650 mg, with over 1000 participants. For this combination, the NNT was below three (indicating good effect) and median time to remedication was about 10 hours. This is at least comparable to typically used doses of NSAIDs, with probably longer duration. Since oxycodone 10 mg is two to three times stronger than codeine 60 mg, it is not surprising that oxycodone 10 mg plus paracetamol 650 mg is more effective than codeine 60 mg plus paracetamol 650 mg, which has an NNT of about four and a shorter time median time to remedication.

For oxycodone alone, and for other combinations of oxycodone plus paracetamol, the limited data available makes not only results, but also comparison with other data on other analgesics used in similar clinical situations, much less robust. Limited information on adverse events suggests they are more frequent with oxycodone plus paracetamol than placebo, and while they were reported as mild to moderate in severity, they may become problematic with repeated dosing.

Implications for research.

Randomised, double blind, placebo‐controlled trials in moderate to severe postoperative pain are required to better evaluate the effects of oxycodone, with or without paracetamol, and to better establish dose‐response relationships. Because the efficacy of oxycodone plus paracetamol is now established, it may be more appropriate for resources to be put towards clinical effectiveness trials to establish which postoperative analgesic protocol leads to the best results for the most patients.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 29 May 2019 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

| 11 October 2017 | Review declared as stable | No new studies likely to change the conclusions are expected. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 4, 2000 Review first published: Issue 4, 2000

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 18 August 2016 | Review declared as stable | See Published notes. |

| 24 September 2010 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

| 13 May 2009 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Revised estimates of efficacy and harm, new efficacy outcomes added. The new review includes 20 studies, with 2641 participants, compared with 7 studies and 769 participants from the original review. The new review, with more participants in comparisons, provides better estimates of efficacy and harm, some of which have changed substantially from the previous review, and show that single dose oxycodone is an effective analgesic at doses over 5 mg. Efficacy increases when combined with paracetamol. Oxycodone 10 mg plus paracetamol 650 mg provides good analgesia over four to six hours to about half of those treated, comparable to commonly used non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs, but with the benefit of longer duration of action. Nausea, vomiting, dizziness and somnolence were more common than with oxycodone than placebo. The title also now states that the review is limited to adults and oral administration only. Changes to authorship: Jayne Rees (neè Edwards) worked on the original version of this review but was not involved in this update and Sheena Derry and Helen Gaskell were involved with the update of this review. |

| 13 May 2009 | New search has been performed | New studies added in December 2008 and the analysis was updated. An updated search prior to publication in May 2009 found two additional studies that are awaiting classification. |

| 23 May 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

Notes

A restricted search in August 2016 identified one relevant study (Daniels 2013). However, we did not identify any potentially relevant studies likely to change the conclusions. Therefore, this review has now been stabilised following discussion with the authors and editors. If appropriate, we will update the review if new evidence likely to change the conclusions is published, or if standards change substantially which necessitate major revisions.

Daniels SE, Spivey RJ, Singla S, Golf M, Clark FJ. Efficacy and safety of oxycodone HCl/niacin tablets for the treatment of moderate‐to‐severe postoperative pain following bunionectomy surgery. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011 Mar;27(3):593‐603. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2010.548291. Epub 2011 Jan 13.

Acknowledgements

Jayne Rees (nee Edwards) was an author, and Dr Robert Kaiko and Dr Earle Lockhart helped in identifying additional citations for the original review.

The previous review received financial support from:

Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, UK

SmithKline Beecham Consumer Healthcare.

European Union Biomed 2 (#BMH4‐CT95‐0172).

NHS R&D Health Technology Evaluation Programmes, UK

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategy for MEDLINE via Ovid