Abstract

Background

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) is the most common pre-malignant lesion. Atypical squamous changes occur in the transformation zone of the cervix with mild, moderate or severe changes described by their depth (CIN 1, 2 or 3). Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia is treated by local ablation or lower morbidity excision techniques. Choice of treatment depends on the grade and extent of the disease.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness and safety of alternative surgical treatments for CIN.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Gynaecological Cancer Group Trials Register, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library), MEDLINE and EMBASE (up to April 2009). We also searched registers of clinical trials, abstracts of scientific meetings and reference lists of included studies.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of alternative surgical treatments in women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently abstracted data and assessed risks of bias. Risk ratios that compared residual disease after the follow-up examination and adverse events in women who received one of either laser ablation, laser conisation, large loop excision of the transformation zone (LLETZ), knife conisation or cryotherapy were pooled in random-effects model meta-analyses.

Main results

Twenty-nine trials were included. Seven surgical techniques were tested in various comparisons. No significant differences in treatment failures were demonstrated in terms of persistent disease after treatment. Large loop excision of the transformation zone appeared to provide the most reliable specimens for histology with the least morbidity. Morbidity was lower than with laser conisation, although the trials did not provide data for every outcome measure. There were not enough data to assess the effect on morbidity when compared with laser ablation.

Authors’ conclusions

The evidence suggests that there is no obvious superior surgical technique for treating cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in terms of treatment failures or operative morbidity.

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH): Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia [*surgery], Conization [methods], Cryosurgery, Laser Therapy [methods], Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Uterine Cervical Neoplasms [*surgery]

MeSH check words: Female, Humans

BACKGROUND

Description of the condition

Cervical cancer is the second most common cancer among women (GLOBOCAN 2009). A woman’s risk of developing cervical cancer by age 65 years ranges from 0.8% in developed countries to 1.5% in developing countries (IARC 2002). In Europe, about 60% of women with cervical cancer are alive five years after diagnosis (EUROCARE 2003). Cervical screening aims to identify women with asymptomatic disease and to treat the disease with a low morbidity procedure thus lowering the risk of developing invasive disease. In countries with effective screening programmes, dramatic reductions have occurred in the incidence of disease and the stage of cancer if disease is diagnosed (Peto 2004). Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) is the most common pre-malignant lesion, with atypical squamous changes in the transformation zone of the cervix. Mild, moderate or severe changes are described by their depth (CIN 1, 2 or 3). If CIN progresses it develops into squamous cancer. In contrast, the much rarer glandular pre-cancerous abnormalities (cervical glandular intraepithelial neoplasia or CGIN) becomes cervical adenocarcinoma.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the cause of pre-cancerous abnormalities of the cervix. HPV has over 100 subtypes and is present in over 95% of pre-invasive and invasive squamous carcinomas of the cervix. Serotypes associated with cervical squamous lesions may be designated as having a high or low risk for progression to malignancy. HPV infection in young women is commonly a transient infection and the body’s own immune response clears the disease from the cervical tissues. If pre-invasive disease has been present and the immunological response clears HPV infection then the pre-invasive disease will resolve. Sexually active young women under 30 years of age have a very high rate of HPV infection whilst women over 30 years of age have a much lower HPV infection rate (Sargent 2008). This is a reflection of the natural history of disease, with a 50% regression rate and only a 10% progression rate of low grade CIN in young women (Ostor 1993).

The frequency of abnormal Papanicolaou smear test results and subsequent CIN varies with the population tested, the test used and the reported accuracy. It is estimated to range between 1.5% to 6% (Cirisano 1999).

When CIN is identified, colposcopists generally treat CIN 2 or high grade disease and either observe or immediately treat CIN 1 depending on personal preference. The aim of this review was to compare different treatment modalities to assess their effectiveness for treating disease.

Description of the intervention

Current treatment for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) is by local ablative therapy or by excisional methods, depending on the nature and extent of disease. Traditionally, prior to colposcopy, all lesions were treated by knife excisional cone biopsy or by ablative radical point diathermy. Knife cone biopsy and radical point diathermy are usually performed under general anaesthesia and are no longer the preferred treatment as various more conservative local ablative and excisional therapies can be performed in an out-patient setting.

Patients are suitable for ablative therapy provided that:

the entire transformation zone can be visualised (satisfactory colposcopy);

there is no suggestion of micro-invasive or invasive disease;

there is no suspicion of glandular disease;

the cytology and histology correspond.

Excisional treatment is mandatory for a patient with an unsatisfactory colposcopy, suspicion of invasion or glandular abnormality. There is now a trend to utilise low morbidity excisional methods, either laser conisation or large loop excision of the transformation zone (LLETZ), in place of destructive ablative methods. Excisional methods offer advantages over destructive methods in that they can define the exact nature of disease and the completeness of excision or destruction of the transformation zone. Incomplete excision or destruction of the transformation zone is an important indicator of patients at risk of treatment failure or recurrence of disease.

The treatment modalities included in this review are described below.

Knife cone biopsy

Traditionally, broad deep cones were performed for most cases of CIN. Excision of a wide and deep cone of the cervix is associated with significant short and long term morbidity (peri-operative, primary and secondary haemorrhage, local and pelvic infection, cervical stenosis and mid-trimester pregnancy loss) (Jordan 1984;Leiman 1980; Luesley 1985). A less radical approach is now generally adopted, tailoring the width and depth of the cone according to colposcopic findings. The procedure is invariably performed under general anaesthesia. Peri-operative haemostasis can be difficult to achieve and various surgical techniques have been developed to reduce bleeding. Routine ligation of the cervical vessels is commonly performed. This technique also allows manipulation of the cervix during surgery. Sturmdorf sutures have been advocated by some surgeons to promote haemostasis; others recommend circumferential locking sutures, electrocauterisation or cold coagulation, or vaginal compression packing.

The treatment success (that is no residual disease on follow up) of knife cone biopsy is reported as 90% to 94% (Bostofte 1986;Larson 1983; Tabor 1990) in non-randomised studies.

Laser conisation

This procedure can be performed under general or local analgesia. A highly focused laser spot is used to make an ectocervical circumferential incision to a depth of 1 cm. Small hooks or retractors are then used to manipulate the cone to allow deeper incision and complete the endocervical incision. Haemostasis, if required, is generally achieved through laser coagulation by defocusing the beam. A disadvantage of laser conisation is that the cone biopsy specimen might suffer from thermal damage, making histological evaluation of margins impossible.

The treatment success of laser cone biopsy is reported as 93% to 96% (Bostofte 1986; Tabor 1990) in non-randomised studies. The major advantages are accurate tailoring of the size of the cone, low blood loss in most cases, and less cervical trauma than with knife cut cones.

Loop excision of the transformation zone

Large loop excision of the transformation zone is often abbreviated to LLETZ in the UK or LEEP (loop electrosurgical excisional procedure) in the USA. A wire loop electrode on the end of an insulated handle is powered by an electrosurgical unit. The current is designed to achieve a cutting and coagulation effect simultaneously. Power should be sufficient to excise tissue without causing a thermal artefact. The procedure can be performed under local analgesia.

Treatment success of LLETZ is reported as 98% (Prendeville 1989), 96% (Bigrigg 1990), 96% (Luesley 1990), 95% (Whiteley 1990), 91% (Murdoch 1992) and 94% (Wright TC 1992) in nonrandomised studies.

Laser ablation

A laser beam is used to destroy the tissue of the transformation zone. Laser destruction of tissue can be controlled by the length of exposure. Defocusing the beam permits photocoagulation of bleeding vessels in the cervical wound.

Treatment success of laser ablation is reported as 95% to 96% (Jordan 1985).

Cryotherapy

A circular metal probe is placed against the transformation zone. Hypothermia is produced by the evaporation of compressed refrigerant gas passing through the base of the probe. The cryonecrosis is achieved by crystallization of intracellular water. The effect tends to be patchy as sublethal tissue damage tends to occur at the periphery of the probe.

In non-controlled studies the success of treatment of CIN3 varied, between 77% and 93%, 87% (Benedet 1981), 77% (Hatch 1981), 82% (Kaufman 1978), 84% (Ostergard 1980), and 93% (Popkin et al 1978).

Utilising a double freeze-thaw-freeze technique improved the reliability in the observational study by Creasman 1984. Rapid ice-ball formation indicates that the depth of necrosis will extend to the periphery of the probe. The procedure can be associated with unpleasant vasomotor symptoms.

Why it is important to do this review

This systematic review examines the efficacy and morbidity of local ablative and excisional therapies for eradicating disease. The effectiveness and morbidity of the various forms of treatment have generally been evaluated in uncontrolled observational studies. Hence direct comparison of treatment effects of alternative treatmentsis unreliable because of variable patient selection, treatment outcomes and follow-up criteria. We have, therefore, only included trials which appear to be randomised in order to reduce selection bias and potentially provide results with greater certainty.

OBJECTIVES

To assess the effectiveness and safety of alternative surgical treatments for CIN

METHODS

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs). Quasi-randomised controlled trials were included in the first version of the review but excluded from the second version as they did not contribute to any meta-analyses.

Types of participants

Women with CIN confirmed by biopsy and undergoing surgical treatment. We have not included treatments for glandular intraepithelial neoplasia in our review.

Types of interventions

We considered direct comparisons between any of the following interventions.

Laser ablation.

Laser conisation.

Large loop excision of the transformation zone (LLETZ).

Knife conisation.

Cryotherapy.

Other types of surgical interventions for CIN were considered if relevant trials were found. We also compared variations in technique within a single intervention (for example blend versus cut setting for LLETZ, single versus double freeze cryotherapy).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Residual disease detected on follow-up examination.

Secondary outcomes

- Adverse events, classified according to CTCAE 2006:

- peri-operative severe pain;

- peri-operative severe bleeding, primary and secondary haemorrhage;

- depth and presence of thermal artifact;

- inadequate colposcopy at follow up;

- cervical stenosis at follow up;

- vaginal discharge.

Duration of treatment.

Search methods for identification of studies

There were no language restrictions.

Electronic searches

See: the Cochrane Gynaecological Cancer Group methods used in reviews.

The following electronic databases were searched:

The Cochrane Gynaecological Cancer Review Group Trial Register;

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library);

MEDLINE;

EMBASE.

The MEDLINE, EMBASE and CENTRAL search strategies are presented in Appendix 1, Appendix 2 and Appendix 3 respectively. Databases were searched from 1966 until 2000 in the original review and up to April 2009 in this updated version. All relevant articles found were identified on PubMed and, using the ‘related articles’ feature, a further search was carried out for newly published articles.

Searching other resources

Unpublished and grey literature

Metaregister, Physicians Data Query, www.controlled-trials.com/rct, www.clinicaltrials.gov and www.cancer.gov/clinicaltrials were searched for ongoing trials.

Handsearching

First version of the review

The citation lists of included studies were checked through handsearching and experts in the field were contacted to identify further reports of trials. Sixteen journals that were thought to be the most-likely to contain relevant publications were handsearched (Acta Cytologica, Acta Obstetrica Gynecologica Scandanavia, Acta Oncologica, American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Cancer, Cytopathology, Diagnostic Cytopathology, Gynecologic Oncology, International Journal of Cancer, International Journal of Gynaecological Cancer, Journal of Family Practice, Obstetrics and Gynaecology).

Second version of the review

This update is based on RCTs identified by electronic literature databases. All 16 previously handsearched publications are indexed in MEDLINE. As the accuracy of indexing RCTs is now very robust, further handsearching was not performed.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

First version of the review

In the original review, all the possible publications identified by manual and electronic searches were collated onto an Excel spreadsheet. Two authors (P M-H and EP) independently scrutinised the studies to see if they met the inclusion or exclusion criteria. Diasagreements were resolved after discussion.

Second version of the review

All titles and abstracts retrieved by electronic searching were downloaded to the reference management database Endnote, duplicates were then removed and the remaining references examined by four review authors (AB, HD, PM-H, SK) working independently. Those studies which clearly did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded and copies of the full text of potentially relevant references were obtained. The eligibility of retrieved papers were assessed independently by two review authors (PM-H, SK). Disagreements were resolved by discussion between the two authors. Reasons for exclusion were documented.

Data extraction and management

For included studies, data were extracted on the following.

Author, year of publication and journal citation (including language).

Country.

Setting.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Study design, methodology.

- Study population:

- ○ total number enrolled,

- ○ patient characteristics,

- ○ age.

CIN details.

- Intervention details:

- ○ variations in technique.

Risk of bias in study (see below).

Duration of follow up.

Outcomes - see below.

Data on outcomes were extracted as below for:

dichotomous outcomes (e.g. residual disease, pain, haemorrhage, inadequate colposcopy, cervical stenosis, vaginal discharge), where we extracted the number of patients in each treatment arm who experienced the outcome of interest and the number of patients assessed at the end point in order to estimate a risk ratio;

continuous outcomes (e.g. depth of thermal artifact, duration of procedure), where we extracted the final value and standard deviation of the outcome of interest and the number of patients assessed at the end point in each treatment arm at the end of follow up in order to estimate the mean difference between treatment arms and its standard error.

Where possible, all data extracted were those relevant to an intention-to-treat analysis, in which participants were analysed in groups to which they were assigned.

The time points at which outcomes were collected and reported were noted.

Data were abstracted independently by two review authors (AB, SK) onto a data abstraction form specially designed for the review. Differences between review authors were resolved by discussion.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The risk of bias in included RCTs was assessed using the following questions and criteria.

Sequence generation

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated?

Yes, e.g. a computer-generated random sequence or a table of random numbers

No, e.g. date of birth, clinic identity number or surname

Unclear, e.g. if not reported

Allocation concealment

Was allocation adequately concealed?

Yes, e.g. where the allocation sequence could not be foretold

No, e.g. allocation sequence could be foretold by patients, investigators or treatment providers

Unclear, e.g. if not reported

Blinding

Assessment of blinding was restricted to blinding of outcome assessors since it is generally not possible to blind participants and treatment providers to surgical interventions.

Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented during the study?

Yes

No

Unclear

Incomplete reporting of outcome data

We recorded the proportion of participants whose outcomes were not reported at the end of the study; we noted whether or not loss to follow up was reported.

Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed?

Yes, if fewer than 20% of patients were lost to follow up and reasons for loss to follow up were similar in both treatment arms

No, if more than 20% of patients were lost to follow up or reasons for loss to follow up differed between treatment arms

Unclear, if loss to follow up was not reported

Selective reporting of outcomes

Are reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting?

Yes, e.g. if the report included all outcomes specified in the protocol

No, if otherwise

Unclear, if insufficient information available

Other potential threats to validity

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a high risk of bias?

Yes

No

Unclear

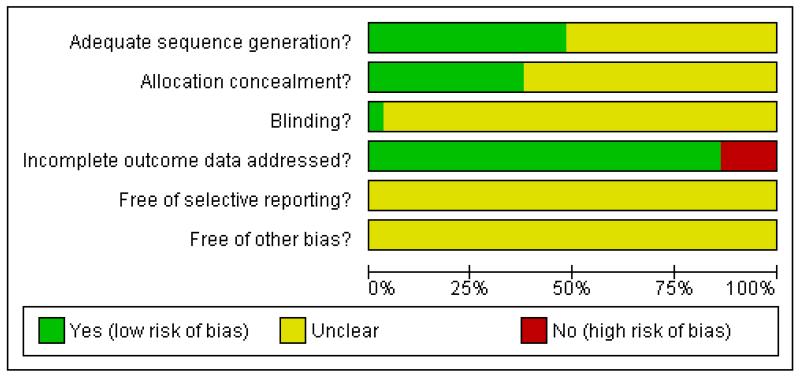

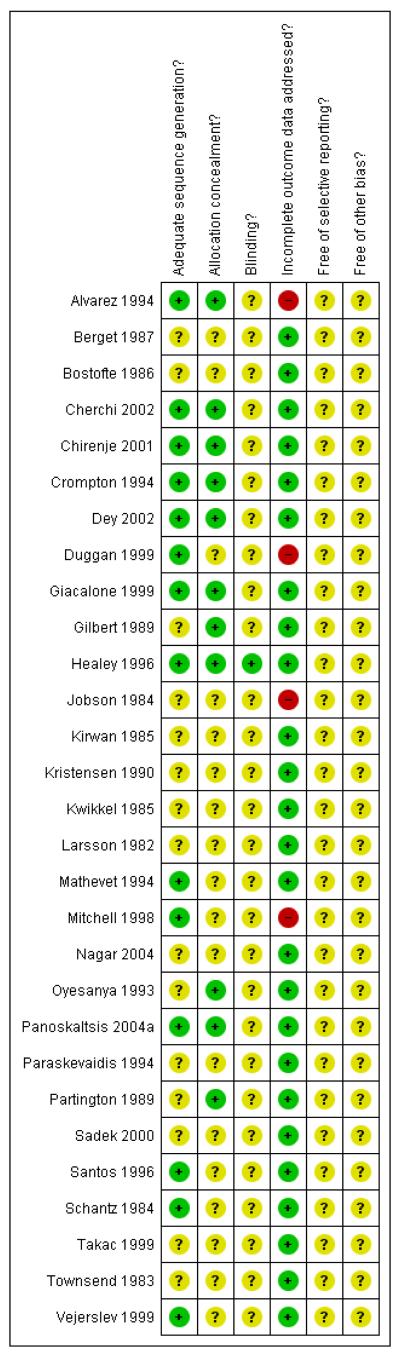

The risk of bias tool was applied independently by two review authors (AB, SK) and differences were resolved by discussion. Results were presented in both a risk of bias graph and a risk of bias summary. Results of the meta-analyses were interpreted in light of findings with the risk of bias assessment.

Measures of treatment effect

We used the following measures of the effect of treatment.

For dichotomous outcomes, we used the risk ratio.

For continuous outcomes, we used the mean difference between treatment arms.

Dealing with missing data

We did not impute missing outcome data for any outcome.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Heterogeneity between studies was assessed by visual inspection of forest plots, estimation of the percentage of the heterogeneity between trials which cannot be ascribed to sampling variation (Higgins 2003), a formal statistical test of the significance of the heterogeneity (Deeks 2001) and, where possible, by subgroup analyses (see below). If there was evidence of substantial heterogeneity, the possible reasons for this were investigated and reported.

Data synthesis

The results of clinically similar studies were pooled in meta-analyses.

For any dichotomous outcomes, the risk ratio was calculated for each study and these were then pooled.

For continuous outcomes, the mean difference between the treatment arms at the end of follow up was pooled, if all trials measured the outcome on the same scale; otherwise standardised mean differences were pooled.

A random-effects model with inverse variance weighting was used for all meta-analyses (DerSimonian 1986).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Subgroup analyses were performed where possible, grouping the trials by:

CIN stage (CIN1, CIN2, CIN3).

RESULTS

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies.

Results of the search

The original search strategy identified references which were then screened by title and abstract in order to identify 29 studies as potentially eligible for the review. The updated search strategy identified 1225 unique references. The title and abstract screening of these references identified 10 studies as potentially eligible for the review. Overall, the full text screening of these 39 studies excluded 10 for the reasons described in the table Characteristics of excluded studies. The remaining 29 RCTs met our inclusion criteria and are described in the table Characteristics of included studies. Searches of the grey literature did not identify any additional relevant studies.

Included studies

The 29 included trials randomised a total of 5441 women, of whom 4509 were analysed at the end of the trials. The largest of these studies recruited 498 participants (Mitchell 1998) and the smallest recruited 40 women (Cherchi 2002; Paraskevaidis 1994). The majority of studies were performed in single centres in a university setting, with multi-centre designs being used by the minority (Alvarez 1994; Berget 1987; Dey 2002; Vejerslev 1999). These trials were mainly from Europe and North America with the exceptions being Peru (Santos 1996) and Zimbabwe (Chirenje 2001).

A total of 865 women participating in the trials had a diagnosis of CIN 1,1185 had CIN2, 1843 had CIN3, 25 had micro-invasion or carcinoma and 52 were negative at final histology, with the remainder having unknown histology or their status was not given. The average age of the participants within the trials was 31.8 years. Eighteen studies included laser techniques as part of their methodology. These trials compared the use of laser surgery to cryotherapy (Berget 1987; Jobson 1984; Kirwan 1985; Kwikkel 1985;Mitchell 1998; Townsend 1983), knife conisations (Bostofte 1986; Kristensen 1990; Larsson 1982; Mathevet 1994), LLETZ using either conisation techniques (Crompton 1994; Mathevet 1994; Oyesanya 1993; Paraskevaidis 1994; Santos 1996; Vejerslev 1999) or laser ablation (Alvarez 1994; Dey 2002; Mitchell 1998) and the different laser techniques (ablation versus conisation (Partington 1989).

Nine studies included knife conisation as part of their methodology, including comparisons with loop excision (Duggan 1999;Giacalone 1999; Mathevet 1994; Takac 1999), laser surgery (Bostofte 1986; Kristensen 1990; Larsson 1982; Mathevet 1994) or NETZ (Sadek 2000) with or without the insertion of haemo-static sutures (Gilbert 1989; Kristensen 1990).

Eighteen trials investigated diathermy excision of the transformation zone using LLETZ (or LEEP) or similar techniques such as needle excision of the transformation zone (NETZ). These included comparisons of LLETZ with knife conisation (Duggan 1999; Giacalone 1999 Mathevet 1994; Takac 1999), cryotherapy (Chirenje 2001), laser conisation techniques (Crompton 1994;Mathevet 1994; Oyesanya 1993; Paraskevaidis 1994; Santos 1996;Vejerslev 1999) or laser ablative techniques (Alvarez 1994; Dey 2002; Mitchell 1998). Further trials compared LLETZ with radical diathermy (Healey 1996), NETZ (Sadek 2000; Panoskaltsis 2004a) or using different techniques (bipolar electrocautery scissors versus monopolar energy scalpel (Cherchi 2002) or pure cut versus blend settings (Nagar 2004)).

Eight trials included the use of cold coagulation as a technique, comparing this to LLETZ (Chirenje 2001) or laser surgical techniques (Berget 1987; Jobson 1984; Kirwan 1985; Kwikkel 1985;Mitchell 1998; Townsend 1983). A further trial compared differing types of cryotherapy, single versus double freeze techniques (Schantz 1984).

Excluded studies

Eleven references were excluded from this review as they were found to be non-randomised studies (Bar-AM 2000; Lisowski 1999), quasi-RCTs (Ferenczy 1985; Girardi 1994; Gunasekera 1990; O’Shea 1986; Singh 1988), a review or commentary of earlier trials (Gentile 2001; Panoskaltsis 2004b) or an RCT which did not report any of the outcomes specified in this review (Boardman 2004).

Risk of bias in included studies

Most trials were at moderate or high risk of bias: 22 trials satisfied less than three of the criteria that we used to assess risk of bias, six satisfied three of the criteria, and only one trial was at low risk of bias (Healey 1996) as it satisfied four of the criteria (see Figure 1; Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Methodological quality graph: review authors’ judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Figure 2.

Methodological quality summary: review authors’ judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Sequence generation

Adequacy of randomisation was confirmed in 14 trials (Alvarez 1994; Cherchi 2002; Chirenje 2001; Crompton 1994; Dey 2002;Duggan 1999; Giacalone 1999; Healey 1996; Mathevet 1994;Mitchell 1998; Panoskaltsis 2004a; Santos 1996; Schantz 1984;Vejerslev 1999), where an appropriate method of sequence generation was used to assign women to treatment groups. The method of randomisation was not reported in the other 15 trials.

Allocation

Concealment of allocation was satisfactory in 11 trials (Alvarez 1994; Cherchi 2002; Chirenje 2001; Crompton 1994; Dey 2002;Giacalone 1999; Gilbert 1989; Healey 1996; Oyesanya 1993;Panoskaltsis 2004a; Partington 1989) but was not reported in any of the other 18 trials.

Blinding

None of the trials reported whether or not the outcome assessor was blinded, except for the trial of Healey 1996 where the investigators collecting and analysing the data were blinded to the treatment mode.

Incomplete outcome data

Loss to follow up was low in 25 of the trials, with at least 80% of women being assessed at the end of the trial. It was unsatisfactory in the other four trials (Alvarez 1994; Duggan 1999; Jobson 1984;Mitchell 1998) as, in at least one of the outcomes, less than 80% of women were assessed at the end point.

Selective reporting

In all 29 trials it was unclear whether outcomes had been selectively reported as there was insufficient information to permit judgement.

Other potential sources of bias

In all 29 trials there was insufficient information to assess whether any important additional risk of bias existed.

Effects of interventions

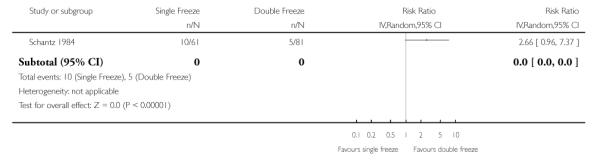

Single freeze cryotherapy compared with double freeze cryotherapy

In the trial of Schantz 1984, the single freeze technique was associated with a statistically non-significant increase in the risk of residual disease within 12 months compared with the double freeze technique (RR 2.66, 95% CI 0.96 to 7.37). (See Analysis 1.1).

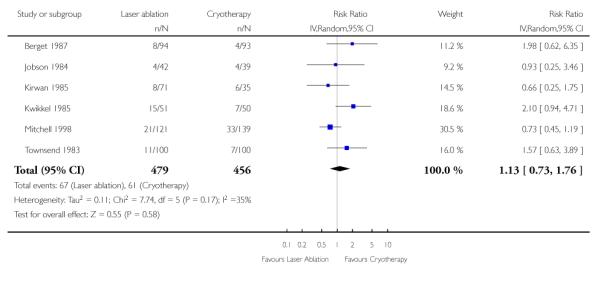

Laser ablation compared with cryotherapy

Residual disease

Meta-analysis of six RCTs (Berget 1987; Jobson 1984; Kirwan 1985; Kwikkel 1985; Mitchell 1998; Townsend 1983), assessing 935 participants, found no significant difference between the two treatments (RR 1.13, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.76). The percentage of the variability in effect estimates that was due to heterogeneity rather than sampling error (chance) may represent moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 35%).

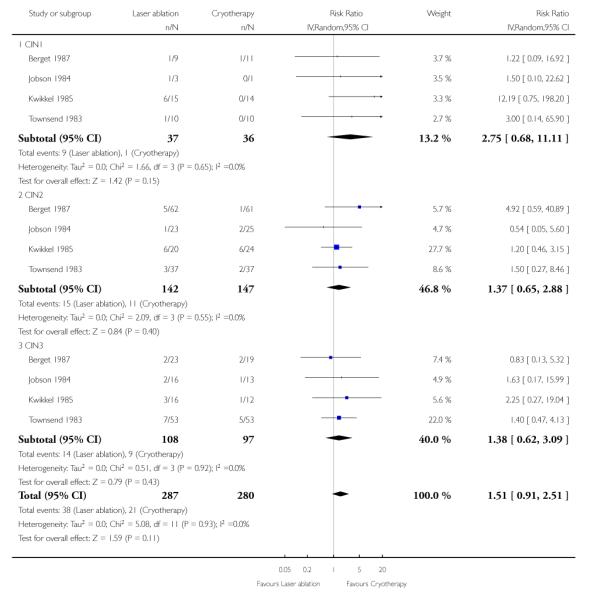

Since only six studies were included in meta-analysis, funnel plots were not examined.

The conclusions above were robust to subgroup analyses examining CIN1, CIN2 and CIN3 separately. Meta-analysis of four trials assessing 73 women with CIN1, 289 women with CIN2 and 205 women with CIN3 showed no statistically significant differences between laser ablation and cryotherapy in the risk of residual disease in each of the subgroups (RR 2.75, 95% CI 0.68 to 11.11, I2 = 0%; RR 1.37, 95% CI 0.65 to 2.88, I2 = 0%; and RR 1.38, 95% CI 0.62 to 3.09, I2 = 0%; respectively). (See Analysis 2.1; Analysis 2.2).

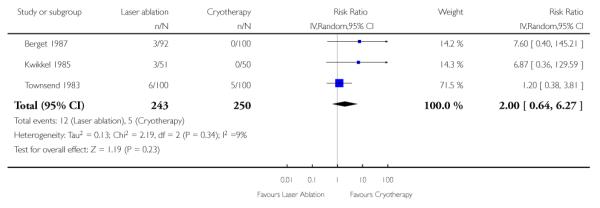

Peri-operative severe pain

Meta-analysis of three RCTs (Berget 1987; Kwikkel 1985;Townsend 1983), assessing 493 participants, showed no statistically significant difference in the risk of peri-operative severe pain in women who received either laser ablation or cryotherapy (RR 2.00, 95% CI 0.64 to 6.27). The percentage of the variability in effect estimates that was due to heterogeneity rather than by chance did not appear to be important (I2 = 9%). (See Analysis 2.3).

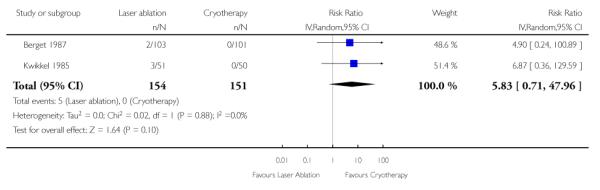

Peri-operative severe bleeding

Meta-analysis of two RCTs (Berget 1987; Kwikkel 1985), assessing 305 participants, showed no statistically significant difference in the risk of peri-operative severe bleeding in women who received either laser ablation or cryotherapy (RR 5.83, 95% CI 0.71 to 47.96). The percentage of the variability in effect estimates that was due to heterogeneity rather than by chance was not important (I2 = 0%). (See Analysis 2.4).

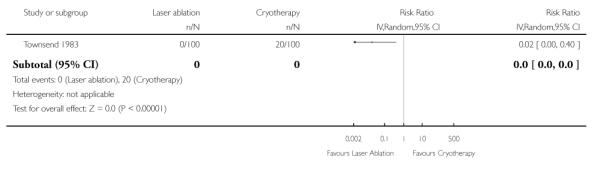

Vasomotor symptoms

In the trial of Townsend 1983, laser ablations were associated with a statistically large and significant decrease in the risk of vasomotor symptoms compared with cryotherapy (RR 0.02, 95% CI 0.00 to 0.40). (See Analysis 2.5).

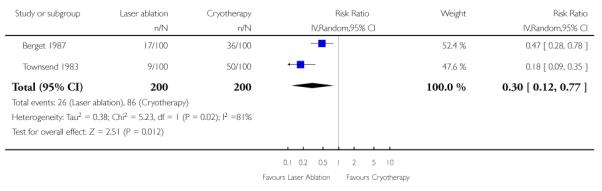

Malodorous discharge

Meta-analysis of two trials (Berget 1987; Townsend 1983), assessing 400 participants, found that laser ablations were associated with a statistically significant decrease in the risk of malodorous discharge compared with cryotherapy (RR 0.30, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.77). The percentage of the variability in effect estimates that was due to heterogeneity rather than by chance may represent considerable heterogeneity (I2 = 81%). (See Analysis 2.6).

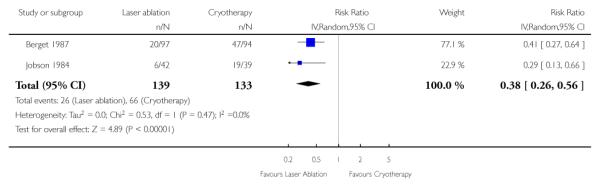

Inadequate colposcopy

Meta-analysis of two trials (Berget 1987; Jobson 1984), assessing 272 participants, found that laser ablations were associated with a statistically significant decrease in the risk of an inadequate colposcopy when compared with cryotherapy (RR 0.38, 95% CI 0.26 to 0.56). The percentage of the variability in effect estimates that was due to heterogeneity rather than by chance was not important (I2 = 0%). (See Analysis 2.7).

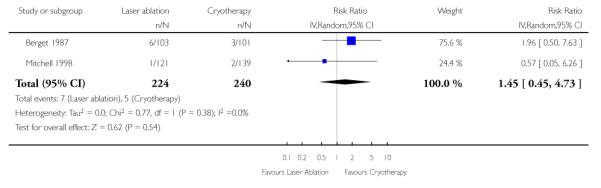

Cervical stenosis

Meta-analysis of two trials (Berget 1987; Mitchell 1998), assessing 464 participants, showed no statistically significant difference in the risk of cervical stenosis in women who received either laser ablation or cryotherapy (RR 1.45, 95% CI 0.45 to 4.73). The percentage of the variability in effect estimates that was due to heterogeneity rather than by chance was not important (I2 = 0%). (See Analysis 2.8).

Laser conisation compared with knife conisation

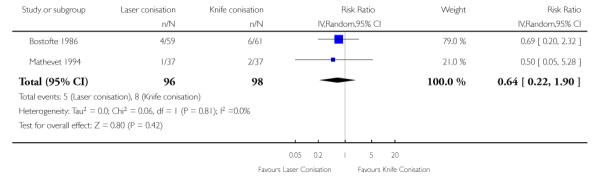

Residual disease (all grades)

Meta-analysis of two trials (Bostofte 1986; Mathevet 1994), assessing 194 participants, found no evidence that residual disease differed between laser conisation and knife conisation (RR 0.64, 95% CI 0.22 to 1.90). The percentage of the variability in effect estimates that was due to heterogeneity rather than by chance was not important (I2 = 0%). (See Analysis 3.1).

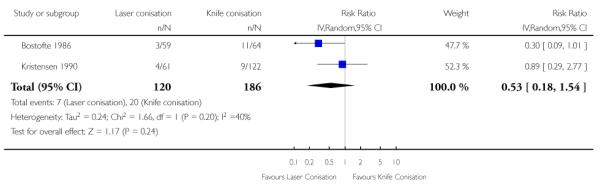

Primary haemorrhage

Meta-analysis of two trials (Bostofte 1986; Kristensen 1990), assessing 316 participants, found no statistically significant difference between laser conisation and knife conisation in the risk of primary haemorrhage (RR 0.53, 95% CI 0.18 to 1.54). The percentage of the variability in effect estimates that was due to heterogeneity rather than by chance may represent moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 40%). (See Analysis 3.2).

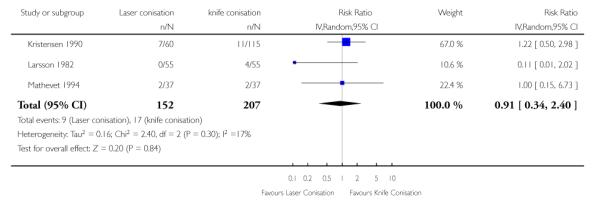

Secondary haemorrhage

Meta-analysis of three trials (Kristensen 1990; Larsson 1982;Mathevet 1994), assessing 359 participants, showed little difference in the risk of secondary haemorrhage in women who received either laser conisation or knife conisation (RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.34 to 2.40). The percentage of the variability in effect estimates that was due to heterogeneity rather than by chance did not appear to be important (I2 = 17%). (See Analysis 3.3).

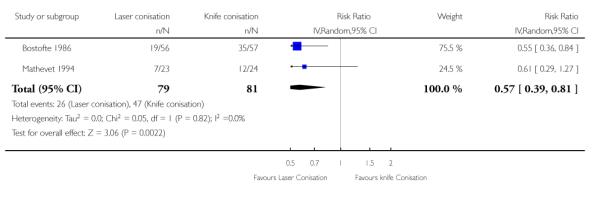

Inadequate colposcopy at follow up

Meta-analysis of two trials (Bostofte 1986; Mathevet 1994), assessing 160 participants, found that laser conisation was associated with a statistically significant decrease in the risk of inadequate colposcopy compared with knife conisation (RR 0.57, 95% CI 0.39 to 0.81). The percentage of the variability in effect estimates that was due to heterogeneity rather than by chance was not important (I2 = 0%). (See Analysis 3.4).

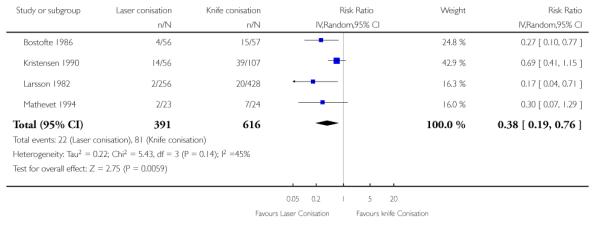

Cervical stenosis at follow up

Meta-analysis of four trials (Bostofte 1986; Kristensen 1990;Larsson 1982; Mathevet 1994), assessing 1009 participants, found that laser conisation was associated with a statistically significant decrease in the risk of cervical stenosis compared with knife conisation (RR 0.38, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.76). The percentage of the variability in effect estimates that was due to heterogeneity rather than by chance may represent moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 45%). (See Analysis 3.5).

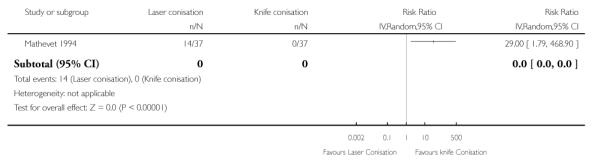

Ectocervical and endocervical margins with disease

In the trial of Mathevet 1994, laser conisation was associated with a large and statistically significant increase in the risk of thermal artifact compared with knife conisation (RR 29.00, 95% CI 1.79 to 468.90). (See Analysis 3.6).

Laser conisation compared with laser ablation

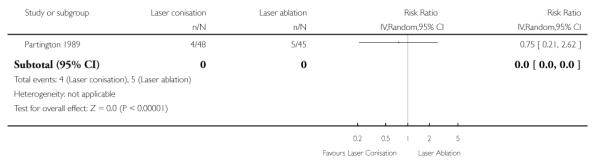

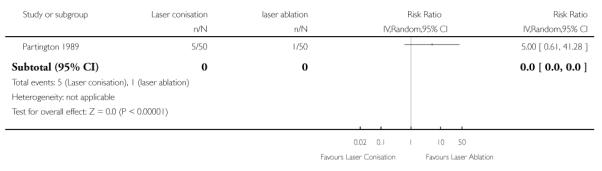

Only the trial of Partington 1989 reported data on laser conisation versus laser ablation.

Residual disease (all grades)

There was no statistically significant difference in the risk of residual disease in women who received either laser conisation or laser ablation (RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.21 to 2.62). (See Analysis 4.1).

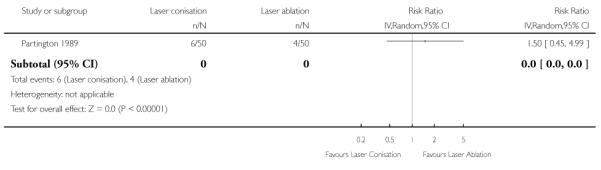

Significant peri-operative bleeding

There was no statistically significant difference in the risk of significant peri-operative bleeding in women who received either laser conisation or laser ablation (RR 1.50, 95% CI 0.45 to 4.99). (See Analysis 4.2).

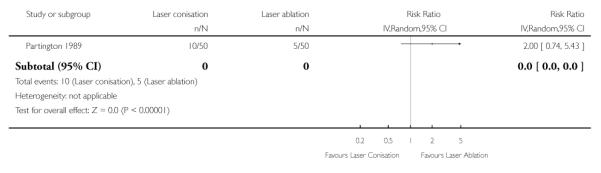

Secondary haemorrhage

There was no statistically significant difference in the risk of secondary haemorrhage in women who received either laser conisation or laser ablation (RR 2.00, 95% CI 0.74 to 5.43). (See Analysis 4.3).

Inadequate colposcopy at follow up

There was no statistically significant difference in the risk of inadequate colposcopy in women who received either laser conisation or laser ablation (RR 5.00, 95% CI 0.61 to 41.28). (See Analysis 4.4).

Laser conisation compared to loop excision

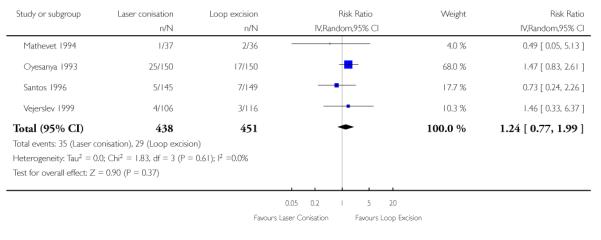

Residual disease

Meta-analysis of four trials (Mathevet 1994; Oyesanya 1993;Santos 1996; Vejerslev 1999), assessing 889 participants, showed little difference in the risk of residual disease in women who received laser conisation or loop excision (RR 1.24, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.99). The percentage of the variability in effect estimates that was due to heterogeneity rather than by chance was not important (I2 = 0%). (See Analysis 5.1).

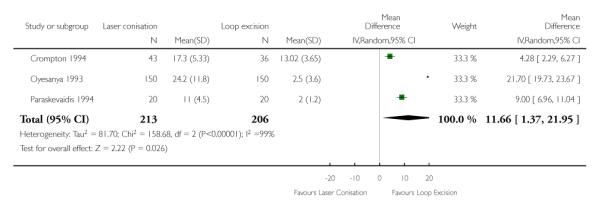

Duration of procedure

Meta-analysis of three trials (Crompton 1994; Oyesanya 1993;Paraskevaidis 1994), assessing 419 participants, found that laser conisation was associated with a statistically significant increased operating time compared with loop excision (mean difference (MD) 11.66, 95% CI 1.37 to 21.95). The percentage of the variability in effect estimates that was due to heterogeneity rather than by chance represented highly variable findings across trials (I2 = 99%), although it appears sensible to pool the results as findings were consistent in that all trials favoured loop excision. (See Analysis 5.2).

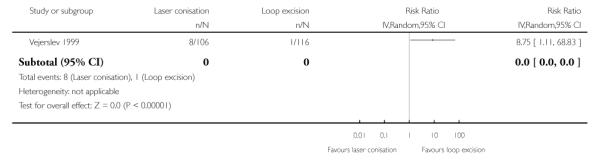

Peri-operative severe bleeding

In the trial of Vejerslev 1999, laser conisation was associated with a statistically large and significant increase in the risk of peri-operative severe bleeding compared with loop excision (RR 8.75, 95% CI 01.11 to 68.83). (See Analysis 5.3).

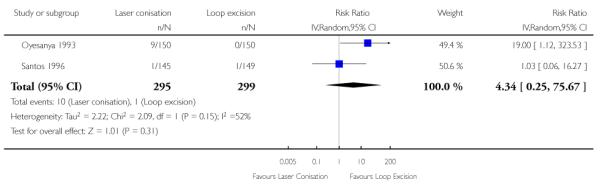

Peri-operative severe pain

Meta-analysis of two trials (Oyesanya 1993; Santos 1996), assessing 594 participants, showed no statistically significant difference in the risk of peri-operative severe pain in women who received either laser conisation or loop excision (RR 4.34, 95% CI 0.25 to 75.67). The percentage of the variability in effect estimates that was due to heterogeneity rather than by chance may represent moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 52%). (See Analysis 5.4).

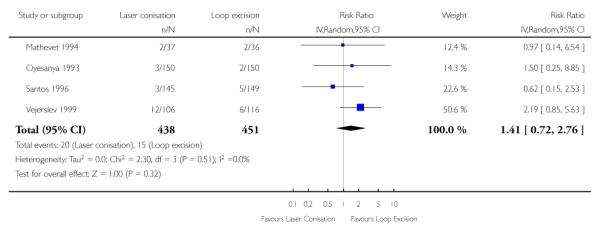

Secondary haemorrhage

Meta-analysis of four trials (Mathevet 1994; Oyesanya 1993;Santos 1996; Vejerslev 1999), assessing 889 participants, showed no statistically significant difference in the risk of secondary haemorrhage in women who received laser conisation or loop excision (RR 1.41, 95% CI 0.72 to 2.76). The percentage of the variability in effect estimates that was due to heterogeneity rather than by chance was not important (I2 = 0%). (See Analysis 5.5).

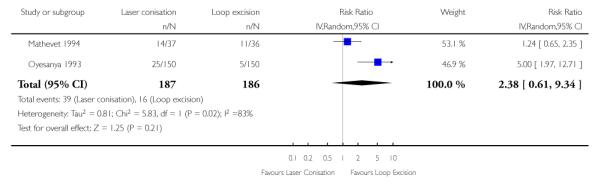

Significant thermal artefact

Meta-analysis of two trials (Mathevet 1994; Oyesanya 1993), assessing 373 participants, showed no statistically significant difference in the risk of significant thermal artefact in women who received laser conisation or loop excision (RR 2.38, 95% CI 0.61 to 9.34). The percentage of the variability in effect estimates that was due to heterogeneity rather than by chance may represent considerable heterogeneity (I2 = 83%). (See Analysis 5.6).

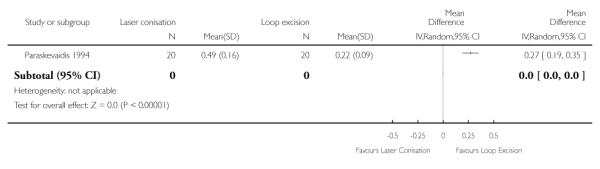

Depth of thermal artefact

In the trial of Paraskevaidis 1994, there was statistically significantly more depth of thermal artefact for laser conisation compared with loop excision (MD 0.27, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.35). (See Analysis 5.7).

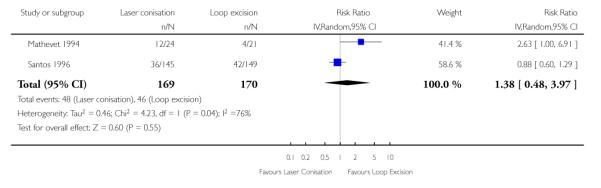

Inadequate colposcopy at follow up

Meta-analysis of two trials (Mathevet 1994; Santos 1996), assessing 339 participants, showed no statistically significant difference in the risk of inadequate colposcopy in women who received laser conisation or loop excision (RR 1.38, 95% CI 0.48 to 3.97). The percentage of the variability in effect estimates that was due to heterogeneity rather than by chance may represent substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 76%). (See Analysis 5.8).

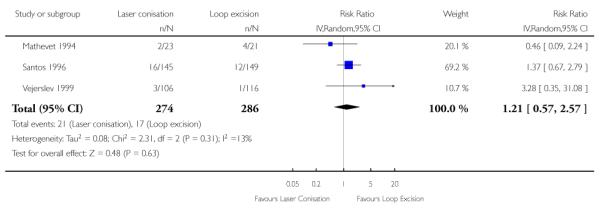

Cervical stenosis at follow up

Meta-analysis of three trials (Mathevet 1994; Santos 1996;Vejerslev 1999), assessing 560 participants, found that there was no statistically significant difference in the risk of cervical stenosis between laser conisation and loop excision (RR 1.21, 95% CI 0.57 to 2.57). The percentage of the variability in effect estimates that was due to heterogeneity rather than by chance did not appear to be important (I2 = 13%). (See Analysis 5.9).

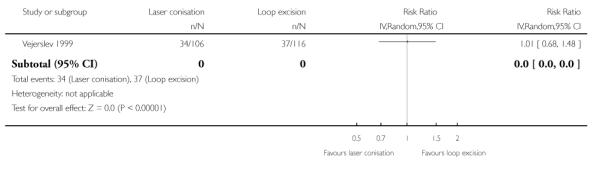

Vaginal discharge

In the trial of Vejerslev 1999 there was no statistically significant difference between laser conisation and loop excision in the amount of vaginal discharge after the operation (RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.68 to 1.48). (See Analysis 5.10).

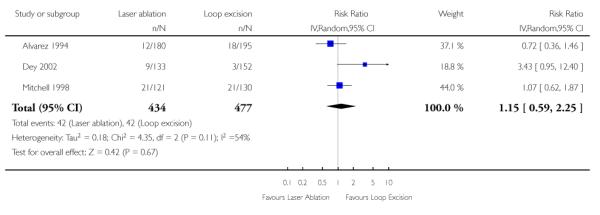

Laser ablation compared to loop excision

Residual disease

Meta-analysis of three trials (Alvarez 1994; Dey 2002; Mitchell 1998), assessing 911 participants, showed little difference in the risk of residual disease in women who received either laser ablation or loop excision (RR 1.15, 95% CI 0.59 to 2.25). The percentage of the variability in effect estimates that was due to heterogeneity rather than by chance may represent moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 54%). (See Analysis 6.1).

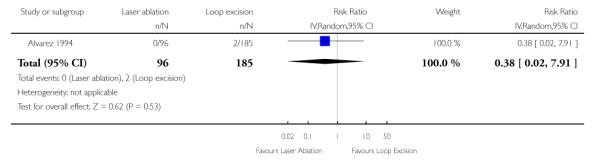

Severe peri-operative pain

The trial of Alvarez 1994, which assessed 185 participants, showed no statistically significant difference in the risk of severe peri-operative pain in women who received laser ablation compared with loop excision (RR 0.38, 95% CI 0.02 to 7.91). (See Analysis 6.2).

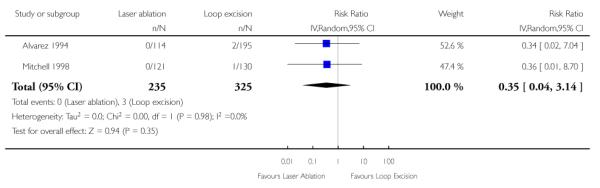

Primary haemorrhage

Meta-analysis of two trials (Alvarez 1994; Mitchell 1998), assessing 560 participants, showed no statistically significant difference in the risk of primary haemorrhage in women who received laser ablation or loop excision (RR 0.35, 95% CI 0.04 to 3.14). The percentage of the variability in effect estimates that was due to heterogeneity rather than by chance was not important (I2 = 0%). (See Analysis 6.3).

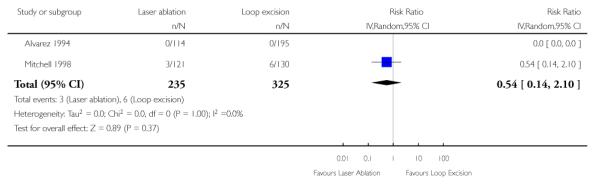

Secondary haemorrhage

Analysis of two trials (Alvarez 1994; Mitchell 1998) assessed only the 231 participants from the Mitchell 1998 trial since a relative risk was not estimable for the trial of Alvarez 1994. The trial ofMitchell 1998 showed no statistically significant difference in the risk of secondary haemorrhage in women who received either laser ablation or loop excision (RR 0.54, 95% CI 0.14 to 2.10). (See Analysis 6.4).

Knife cone biopsy compared to loop excision

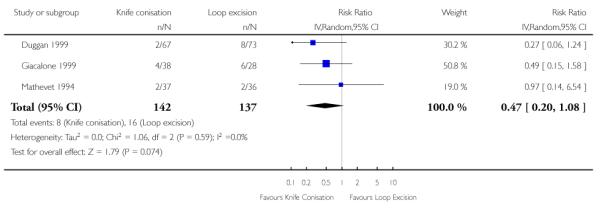

Residual disease

Meta-analysis of three trials (Duggan 1999; Giacalone 1999;Mathevet 1994), 279 participants, found no statistically significant between knife conisation and loop excision in the risk of residual disease (RR 0.47, 95% CI 0.20 to 1.08). The percentage of the variability in effect estimates that was due to heterogeneity rather than by chance was not important (I2 = 0%). (See Analysis 7.1).

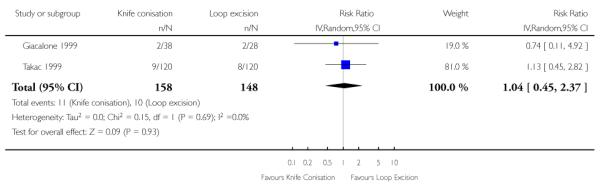

Primary haemorrhage

Meta-analysis of two trials (Giacalone 1999; Takac 1999), assessing 306 participants, showed little difference in the risk of primary haemorrhage in women who received knife conisation or loop excision (RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.45 to 2.37). The percentage of the variability in effect estimates that was due to heterogeneity rather than by chance was not important (I2 = 0%). (See Analysis 7.2).

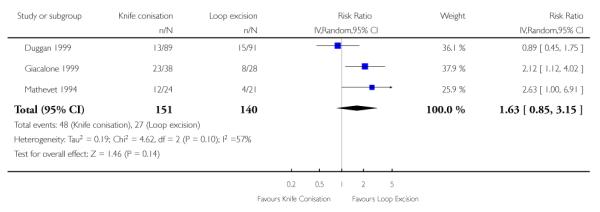

Inadequate colposcopy at follow up

Meta-analysis of three trials (Duggan 1999; Giacalone 1999;Mathevet 1994), assessing 291 participants, showed no statistically significant difference in the risk of inadequate colposcopy in women who received knife conisation or loop excision (RR 1.63, 95% CI 0.85 to 3.15). The percentage of the variability in effect estimates that was due to heterogeneity rather than by chance may represent moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 57%). (See Analysis 7.3).

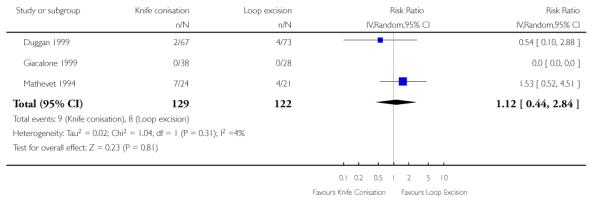

Cervical stenosis

Meta-analysis of three trials (Duggan 1999; Giacalone 1999;Mathevet 1994), assessing 249 participants, showed little difference in the risk of cervical stenosis in women who received knife conisation or loop excision (RR 1.12, 95% CI 0.44 to 2.84). The percentage of the variability in effect estimates that was due to heterogeneity rather than by chance did not appear to be important (I2 = 4%). (See Analysis 7.4).

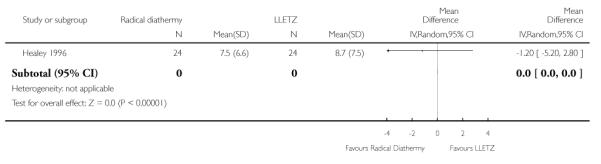

Radical diathermy compared to loop excision

Only the trial of Healey 1996 reported data on radical diathermy versus loop excision.

Duration of blood loss

There was little difference between the duration of blood loss in women who received either radical diathermy or loop excision (MD −1.20, 95% CI −5.20 to 2.80). (See Analysis 8.1).

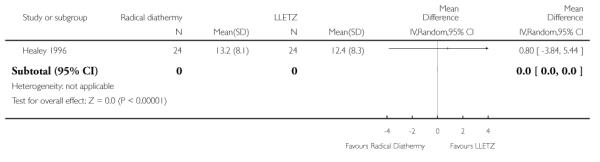

Blood stained or watery discharge

There was little difference between the amount of blood stained or watery discharge in women who received radical diathermy or loop excision (MD 0.80, 95% CI −3.84 to 5.44). (See Analysis 8.2).

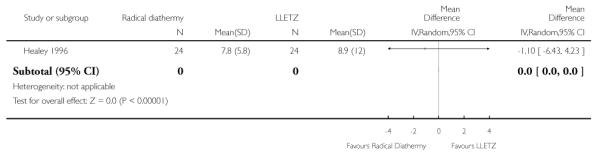

Yellow discharge

There was little difference between the amount of yellow discharge in women who received either radical diathermy or loop excision (MD −1.10, 95% CI −6.43 to 4.23). (See Analysis 8.3).

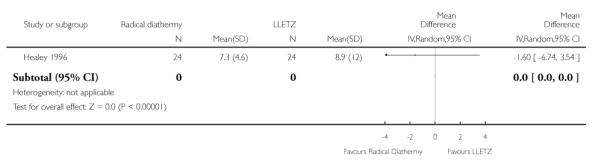

White discharge

There was little difference between the amount of white discharge in women who received radical diathermy or loop excision (MD −1.60, 95% CI −6.74 to 3.54). (See Analysis 8.4).

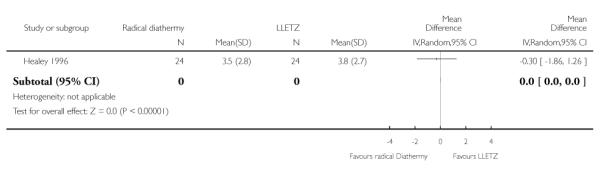

Upper abdominal pain

There was little difference in upper abdominal pain in women who received radical diathermy or loop excision (MD −0.30, 95% CI −1.86 to 1.26). (See Analysis 8.5).

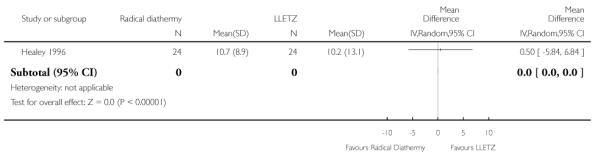

Lower abdominal pain

There was little difference in lower abdominal pain in women who received either radical diathermy or loop excision (MD 0.50, 95% CI −5.84 to 6.84). (See Analysis 8.6).

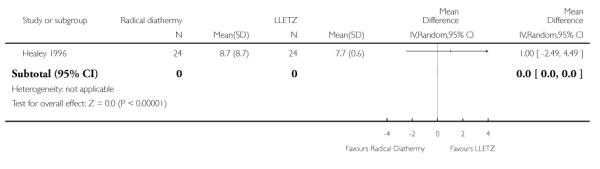

Deep pelvic pain

There was no evidence of a difference in deep pelvic pain in women who received radical diathermy or loop excision (MD 1.00, 95% CI −2.49 to 4.49). (See Analysis 8.7).

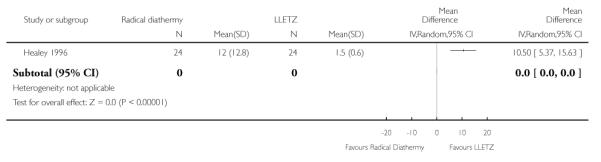

Vaginal pain

Radical diathermy was associated with statistically significant increased vaginal pain compared with LLETZ (MD 10.50, 95% CI 5.37 to 15.63). (See Analysis 8.8).

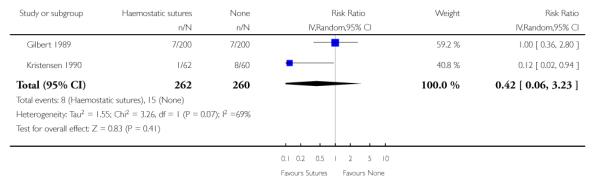

Knife cone biopsy with or without haemostatic sutures

Primary haemorrhage

Meta-analysis of two trials (Gilbert 1989; Kristensen 1990), assessing 522 participants, showed no statistically significant difference in the risk of primary haemorrhage in women who received knife conisation with or without haemostatic sutures (RR 0.42, 95% CI 0.06 to 3.23). The percentage of the variability in effect estimates that was due to heterogeneity rather than by chance may represent substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 69%). (See Analysis 9.1).

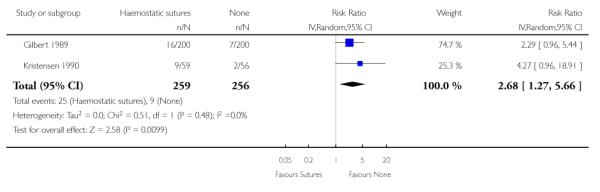

Secondary haemorrhage

Meta-analysis of two trials (Gilbert 1989; Kristensen 1990), assessing 515 participants, found that knife cone biopsy with haemo-static sutures was associated with a statistically significant increase in the risk of secondary haemorrhage compared with using no sutures (RR 2.68, 95% CI 1.27 to 5.66). The percentage of the variability in effect estimates that was due to heterogeneity rather than by chance was not important (I2 = 0%). (See Analysis 9.2).

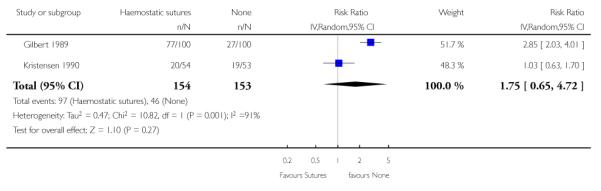

Cervical stenosis at follow up

Meta-analysis of two trials (Gilbert 1989; Kristensen 1990), assessing 307 participants, showed no statistically significant difference in the risk of cervical stenosis in women who received knife conisation with or without haemostatic sutures (RR 1.75, 95% CI 0.65 to 4.72). The percentage of the variability in effect estimates that was due to heterogeneity rather than by chance may represent considerable heterogeneity (I2 = 91%). (See Analysis 9.3).

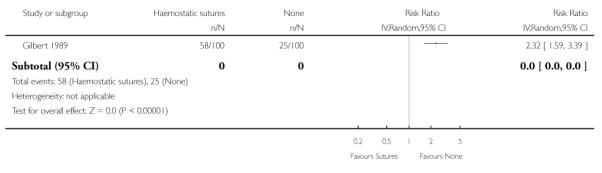

Inadequate colposcopy at follow up

In the trial of Gilbert 1989, knife cone biopsy with haemostatic sutures was associated with a statistically significant increase in the risk of inadequate colposcopy compared with using no sutures (RR 2.32, 95% CI 1.59 to 3.39). (See Analysis 9.4).

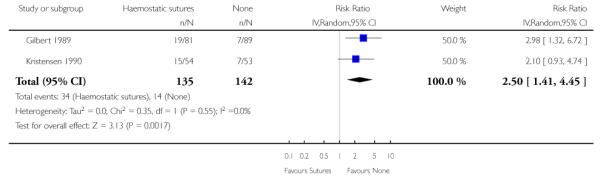

Dysmenorrhoea

Meta-analysis of two trials (Gilbert 1989; Kristensen 1990), assessing 277 participants, found that knife cone biopsy with haemo-static sutures was associated with a statistically significant increase in the risk of dysmenorrhoea compared with using no sutures (RR 2.50, 95% CI 1.41 to 4.45). The percentage of the variability in effect estimates that was due to heterogeneity rather than by chance was not important (I2 = 0%). (See Analysis 9.5).

Bipolar electrocautery scissors versus monopolar energy scalpel

Only the trial of Cherchi 2002 reported data on bipolar electro-cautery scissors versus a monopolar energy scalpel.

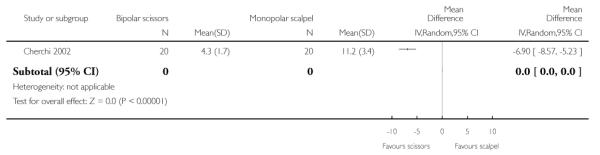

Peri-operative bleeding

Women who underwent surgery for LLETZ had statistically significant less peri-operative blood loss when the surgeon used bipolar electrocautery scissors compared to when the surgeon used a monopolar energy scalpel (MD −6.90, 95% CI −8.57 to −5.23). (See Analysis 10.1).

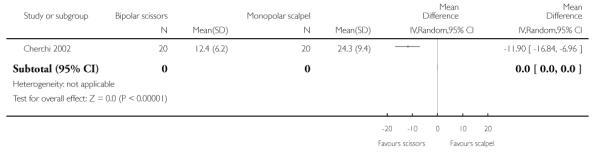

Duration of procedure

Bipolar electrocautery scissors were associated with statistically significant reduced operative time for LLETZ than for the monopolar energy scalpel (MD −11.90, 95% CI −16.84 to −6.96). (See Analysis 10.2).

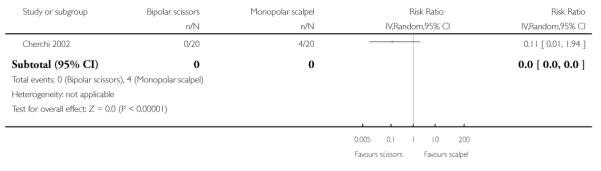

Primary haemorrhage

There was no statistically significant difference between bipolar scissors and monopolar scalpel for LLETZ in the risk of primary haemorrhage (RR 0.11, 95% CI 0.01 to 1.94). (See Analysis 10.3).

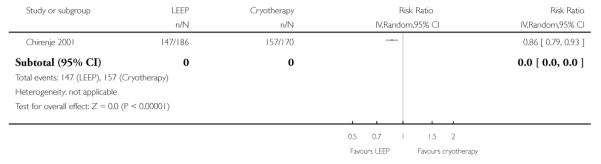

LEEP (loop electrosurgical excisional procedure) versus cryotherapy

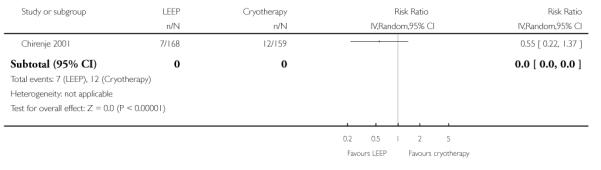

Only the trial of Chirenje 2001 reported data on LEEP versus cryotherapy.

Residual disease at six months

There was no statistically significant difference in the risk of residual disease at six months in women who received either LEEP or cryotherapy (RR 0.55, 95% CI 0.22 to 1.37). (See Analysis 11.1).

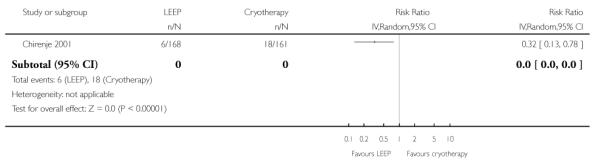

Residual disease at 12 months

There was a statistically significant decrease in the risk of residual disease at 12 months in women who received LEEP compared to those who received cryotherapy (RR 0.32, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.78). (See Analysis 11.2).

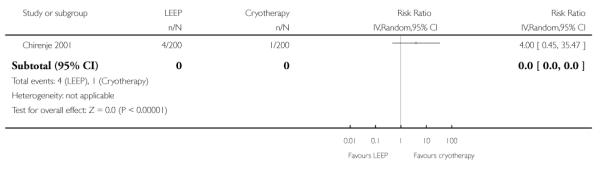

Primary haemorrhage

There was no statistically significant difference in the risk of primary haemorrhage in women who received LEEP or cryotherapy (RR 4.00, 95% CI 0.45 to 35.47). (See Analysis 11.3).

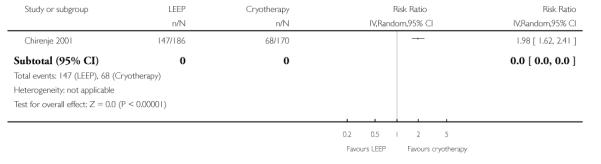

Secondary haemorrhage

There was a statistically significant increase in the risk of secondary haemorrhage in women who received LEEP compared to those who received cryotherapy (RR 1.98, 95% CI 1.62 to 2.41). (See Analysis 11.4).

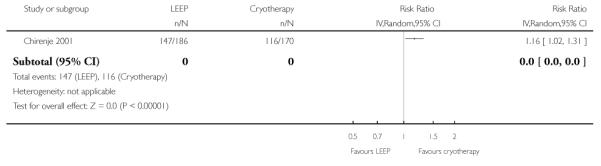

Offensive discharge

There was a statistically significant increase in the risk of offensive discharge in women who received LEEP compared to those who received cryotherapy (RR 1.16, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.31). (See Analysis 11.5).

Watery discharge

There was a statistically significant decrease in the risk of watery discharge in women who received LEEP compared to those who received cryotherapy (RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.79 to 0.93). (See Analysis 11.6).

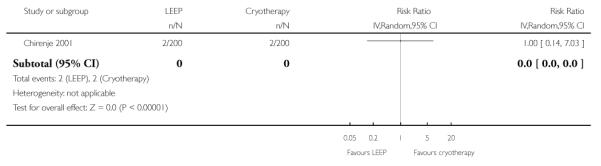

Peri-operative severe pain

There was no statistically significant difference in the risk of peri-operative severe pain in women who received LEEP or cryotherapy (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.14 to 7.03). (See Analysis 11.7).

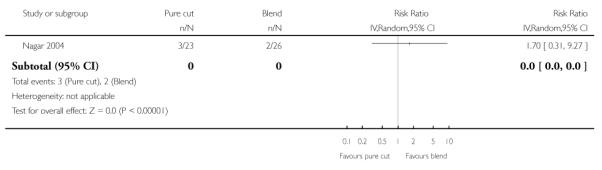

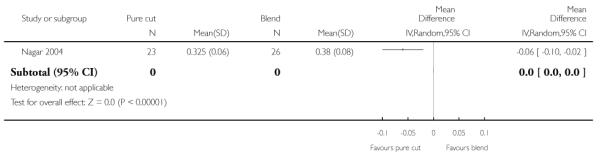

Pure cut setting versus blend setting when performing LLETZ (large loop excision of the transformation zone)

Only the trial of Nagar 2004 reported data on pure cut setting versus blend setting for LLETZ.

Residual disease at six months

There was no statistically significant difference in the risk of residual disease at six months in women whose surgeon used either pure cut or blend setting when they performed LLETZ (RR 1.70, 95% CI 0.31 to 9.27). (See Analysis 12.1).

Depth of thermal artefact at deep stromal margin

There was a statistically significant shorter depth of thermal arte-fact at the deep stromal margin in women whose surgeon used pure cut for LLETZ than for women whose surgeon used the blend setting when they performed LLETZ (MD −0.06, 95% CI −0.10 to −0.02). (See Analysis 12.2).

LLETZ (large loop excision of the transformation zone) versus NETZ (needle excision of the transformation zone)

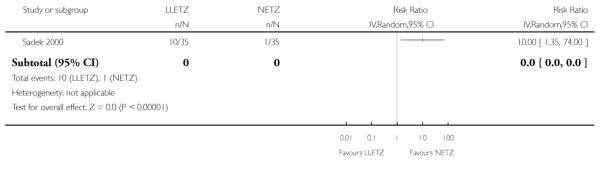

Residual disease at 36 months

In the trial of Sadek 2000, there was a statistically significant increase in the risk of residual disease at 36 months in women who received LLETZ compared to those who received NETZ (RR 10.00, 95% CI 1.35 to 74.00). (See Analysis 13.1).

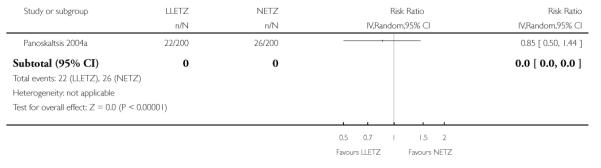

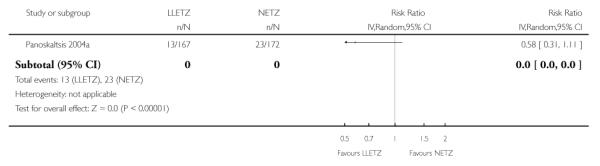

Peri-operative pain

In the trial of Panoskaltsis 2004a, there was no statistically significant difference in the risk of perioperative pain between women who received LLETZ and those who received NETZ (RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.50 to 1.44). (See Analysis 13.2).

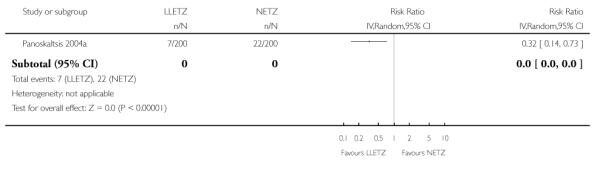

Peri-operative blood loss interfering with treatment

In the trial of Panoskaltsis 2004a, there was a statistically significant decrease in the risk of peri-operative blood loss in women who received LLETZ compared to those who received NETZ (RR 0.32, 95% CI 0.14 to 0.73). (See Analysis 13.3).

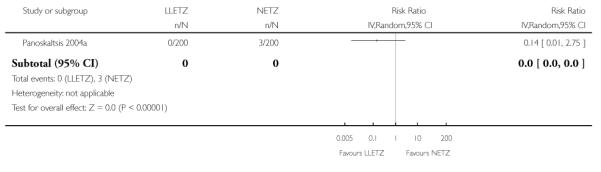

Bleeding requiring vaginal pack

In the trial of Panoskaltsis 2004a, there was no statistically significant difference in the risk of bleeding requiring a vaginal pack between women who received LLETZ and those who received NETZ (RR 0.14, 95% CI 0.01 to 2.75). (See Analysis 13.4).

Cervical stenosis at follow up

In the trial of Panoskaltsis 2004a, there was no statistically significant difference in the risk of cervical stenosis between women who received LLETZ and those who received NETZ (RR 0.58, 95% CI 0.31 to 1.11). (See Analysis 13.5).

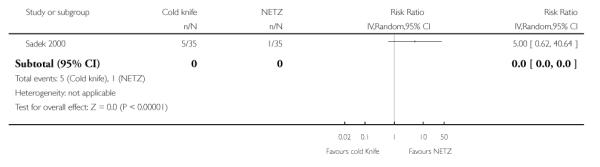

Knife conisation versus NETZ (needle excision of the transformation zone)

Residual disease at 36 months

In the trial of Sadek 2000, there was no statistically significant difference in the risk of residual disease at 36 months between women who received knife conisation and those who received NETZ (RR 5.00, 95% CI 0.62 to 40.64). (See Analysis 14.1).

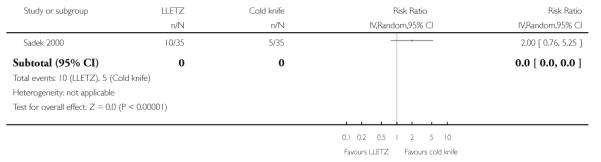

LLETZ (large loop excision of the transformation zone) versus knife conisation

In the trial of Sadek 2000, there was no statistically significant difference in the risk of residual disease at 36 months between women who received LLETZ and those who received knife conisation (RR 2.00, 95% CI 0.76 to 5.25).

DISCUSSION

Summary of main results

(1) For double versus single freeze technique cryotherapy, the evidence suggests that cryotherapy should be used with a double freeze technique rather than single freeze in order to reduce the risk of residual disease within 12 months, although statistical significance was not reached. The single freeze technique had higher treatment failure rates.

(2) Laser ablation demonstrated no overall difference in residual disease after treatment for CIN compared with cryotherapy. Cryosurgery appears to have a lower success rate but the majority of authors used a single freeze thaw technique. Creasman (Creasman 1984) demonstrated that using a double freeze-thaw-freeze technique improves results towards those achieved by destructive and excisional methods. However, analysis of results demonstrated that there was no significant difference for the treatment of CIN1 and 2; laser ablation appeared to be better, but not significantly so, for treating CIN3. The clinician’s choice of treatment of low grade disease must therefore be influenced by the side effects related to the treatments.

Laser ablation was associated with significantly fewer vasomotor symptoms and less malodorous discharge or inadequate colposcopy at follow up compared with cryotherapy. No other statistical differences were observed in any other side effects, although there may be more peri-operative pain and bleeding for laser ablation. Since the number of events was low, this needs to be explored further.

(3) Four trials compared laser conisation and knife conisation (Bostofte 1986; Kristensen 1990; Larsson 1982; Mathevet 1994). For the two trials that evaluated residual disease after laser conisation or knife conisation, no significant difference was observed between the two groups. There was also no evidence of a difference between the two interventions for primary and secondary haemorrhage. Significant thermal artefact prevented interpretation of resection margins in 38% of laser cones compared to none in the knife cones, which was statistically significant. Laser conisation produced significantly fewer inadequate colposcopes (transformation zone seen in its entirety) at follow up and cervical stenosis was significantly less common after this treatment.

(4) Only the trial of Partington 1989 compared laser conisation with laser ablation for ectocervical lesions. There was no significant difference with respect to residual disease at follow up, peri-operative severe bleeding, secondary haemorrhage or inadequate colposcopy at follow up.

(5) Six trials compared laser conisation with large loop excision of the transformation zone (LLETZ) (Crompton 1994; Mathevet 1994; Oyesanya 1993; Paraskevaidis 1994; Santos 1996; Vejerslev 1999). There was no significant difference with respect to residual disease at follow up, peri-operative severe pain, secondary haemorrhage, significant thermal artefact, inadequate colposcopy or cervical stenosis. However, laser conisation takes significantly longer to perform, has a significantly higher rate of perioperative bleeding and produces a greater depth of thermal artefact.

(6) Laser ablation compared to LLETZ was evaluated by four trials. Alvarez 1994 was included in the comparison but its methodology differed from the trials of Dey 2002, Gunasekera 1990 andMitchell 1998. The Alvarez 1994 trial performed LLETZ on all the patients randomised to that group whereas laser ablation was only performed if colposcopic directed biopsies were performed. There was no difference in residual disease rates between the two treatments. There was no significant difference in the risk of primary or secondary haemorrhage or peri-operative severe pain.

(7) For knife cone biopsy compared to loop excision, (a) six randomised trials evaluated knife cone biopsy and loop excision (Duggan 1999, Giacalone 1999, Girardi 1994, Mathevet 1994,Sadek 2000, Takac 1999). The trials found that there was no evidence of a difference between the two interventions on residual disease rate.

(b) Measuring primary haemorrhage, the trials of Giacalone 1999,Duggan 1999, Mathevet 1994 found that there was no statistical difference in inadequate colposcopy rates between knife conisation and loop excision. There was also no clear evidence that there was any difference in primary haemorrhage or cervical stenosis rates.

(8) For radical diathermy versus LLETZ, there was no significant difference between these two modalities with regards to the side effects reported, with exception of significantly increased vaginal pain in those undergoing radical diathermy. Residual disease rates were not an outcome measure in the single trial identified.

(9) For haemostatic sutures, there was no evidence that haemo-static sutures were significantly different for the risk of primary haemorrhage or cervical stenosis compared to using no routine sutures or vaginal packing in the two included trials (Gilbert 1989;Kristensen 1990). Use of haemostatic sutures did however increase the risk of secondary haemorrhage, dysmenorrhoea and inadequate follow-up colposcopy.

(10) One trial compared the use of bipolar electrocautery scissors with a monopolar energy scalpel during LLETZ (Cherchi 2002). Bipolar electrocautery scissors were associated with a significant reduction in perioperative bleeding and duration of the procedure but no change in the rate of primary haemorrhage.

(11) One trial compared the use of LEEP versus cryotherapy (Chirenje 2001). This trial found that women who received the loop electrosurgical excisional procedure (LEEP) had significantly lower rates of watery discharge and residual disease at 12-month follow up but an increased risk of secondary haemorrhage and offensive discharge. There was no significant difference in the rates of primary haemorrhage, residual disease at six months or perioperative severe pain.

(12) One trial compared pure cut settings versus blend settings for LLETZ (Nagar 2004) and found no significant difference in the rates of residual disease between the settings but a reduced depth of thermal artefact at the deep stromal margin in women whose surgeon used a pure cut setting for LLETZ.

(13) Two trials compared LLETZ and needle excision of the transformation zone (NETZ) (Panoskaltsis 2004a; Sadek 2000) but reported on different outcomes. There was no significant difference between the techniques in terms of perioperative pain, bleeding requiring vaginal packing or cervical stenosis at follow up. LLETZ was associated with a reduction in peri-operative blood loss but an increase in residual disease rates at 36-month follow up. There was no difference in residual disease rates for NETZ compared to knife conisation.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The incidence of treatment failures following surgical treatment of CIN has been demonstrated by case series reports, as illustrated in the Background section, to be low. The reports from randomised and non-randomised studies suggest that most surgical treatments have around 90% success rate. In these circumstances, several thousand women would have to be treated to demonstrate a significant difference between two techniques. The vast majority of RCTs evaluating the differences in treatment success are grossly underpowered to demonstrate a significant difference between treatment techniques and no real conclusions can be drawn on differences of treatment effect. The largest of these studies recruited 498 participants (Mitchell 1998) and the smallest recruited 40 women (Cherchi 2002; Paraskevaidis 1994). It might be the case that if a well-conducted mega-trial was conducted no difference in treatment effect would be demonstrated. The RCTs and meta-analyses have demonstrated some clear differences in morbidity and these should be considered as significant outcomes when deciding upon optimum management.

The trials compare different interventions and report different outcomes, which limits the analyses and means that many outcome measures include only one trial per treatment pairing.

Quality of the evidence

In total, 29 trials were included in this review. A total of 5441 women participated of whom 4509 were analysed. We have used a pragmatic approach to the RCTs included in the comparisons. Slight variations of surgical technique occur in some of the comparisons, which reflects the differences in clinical practice. If we considered that these differences did not seriously alter the intervention compared with the other interventions in the comparison, then the trial was considered in the same analysis. For example, when we compared laser ablation to cryotherapy, we included trials using single and double freeze techniques.

Many analyses included only one or two randomised trials due to the different outcome measures chosen and reported in the trials. This limits the conclusions which may be drawn from some of the analyses. Furthermore, the method of randomisation in many of the trials was not optimised so that the results might be prone to bias due to inherent methodological flaws in these trials.

Potential biases in the review process

A comprehensive search was performed, including a thorough search of the grey literature, and all studies were sifted and data extracted by at least two review authors working independently. We restricted the included studies to RCTs as they provide the strongest level of evidence available. Hence, we have attempted to reduce bias in the review process.

The greatest threat to the validity of the review is likely to be the possibility of publication bias. That is, studies that did not find the treatment to be effective may not have been published. We were unable to assess this possibility as the analyses were restricted to meta-analyses of a small number of trials or single trials.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

The conclusions reflect the previous findings from the original Cochrane review by the authors. Furthermore, a Canadian group published an independent systematic review on the same subject and the findings were the same as the original review (Nuovo 2000). The review by Nuovo 2000 used similar methodologies as the original Cochrane review and used quasi-randomised trials as well as gold standard RCTs within their meta-analyses.

The single RCT by Dey 2002 almost demonstrated a significant reduction in treatment failures with LLETZ compared to laser ablation, in contrast to other studies. This trial included HPV testing as well as cytology for screening for treatment failures, which enhances the detection of disease.

AUTHORS’ CONCLUSIONS

Implications for practice

The evidence from the 29 RCTs identified suggests that there is no overwhelmingly superior surgical technique for eradicating CIN. Cryotherapy appears to be an effective treatment of low grade disease but not of high grade disease.

Choice of treatment of ectocervical situated lesions must therefore be based on cost, morbidity and whether excisional treatments provide more reliable biopsy specimens for assessment of disease compared to colposcopic directed specimens taken before ablative therapy. Colposcopic directed biopsies have been shown to under diagnose micro-invasive disease compared with excisional biopsies performed by knife or loop excision, particularly if high grade disease is present (Anderson 1986; Chappatte 1991). However, the accuracy of colposcopic directed biopsies compared to excisional biopsies is not the objective of this review.

Cryotherapy is easy to use, cheap and, as demonstrated, associated with low morbidity. It should be considered a viable alternative for the treatment of low grade disease, particularly where resources are limited.

Laser ablation appears to cause more peri-operative severe pain and perhaps more primary and secondary haemorrhage compared to loop excision. The trials with adequate randomisation methods suggest that there is no difference in residual disease between the two treatments. It could be suggested that LLETZ is superior as equipment is cheaper and it also permits confirmation of disease status by providing an excision biopsy.

Laser conisation takes longer to perform, requires greater operative training and more expensive investment in equipment, produces more peri-operative pain, greater depth and severe thermal artefact than loop excision. Therefore, the use of LLETZ may be preferred rather than laser excision unless the lesion is endocervical. In this situation, a narrow and deep cone biopsy can be performed, reducing tissue trauma and providing a clear resection margin.

Knife cone biopsy still has a place if invasion or glandular disease is suspected. In both diseases adequate resection margins that are free of disease are important for prognosis and management. In such cases, LLETZ or laser conisation can induce thermal artefact so that accurate interpretation of margins is not possible.

Implications for research

We would advocate a large multi-centre trial of sufficient power to evaluate whether ablation is as effective as LLETZ in terms of treatment failures. A systematic review (Kyrgiou 2004) of pre-term delivery rates after treatment suggests that there is a higher rate after excisional treatment compared to ablation. The single RCT by Dey 2002 suggests that ablation is associated with higher failure rates after treatment. A definitive RCT of ablation compared with LLETZ, to see if the two modalities have similar outcomes, is needed. If one modality has genuinely poorer treatment outcomes, this might influence decision making based on pregnancy outcomes.

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY.

No clear evidence to show any one optimal surgical technique is superior for treating pre-cancerous cervix abnormalities

Cervical pre-cancer (cervical intraepithelial neoplasia) can be treated in different ways depending on the extent and nature of the disease. Less invasive treatments that do not require a hospital stay may be used. A general anaesthetic is occasionally needed, especially if the disease has spread locally, early invasion is suspected or previous out-patient treatment has failed. Surgery can be done with a knife, cryotherapy (freezing the abnormal cells), laser or cutting with a loop (an electrically charged wire). This review found there was not enough evidence to confidently select the most effective technique and that more research is needed.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

None

SOURCES OF SUPPORT

Internal sources

No sources of support supplied

External sources

Department of Health, UK.

NHS Cochrane Collaboration programme Grant Scheme CPG-506

CHARACTERISTICS OF STUDIES

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | 375 women with cervical smears suggesting CIN 2 or 3, or 2 smears equivalent to CIN1 Women with adequate colposcopy included with entire lesion visible, not pregnant Women with vaginitis, lesion extending to vagina, evidence of invasion excluded | |

| Interventions | Primary LLETZ Colposcopic directed biopsy and endocervical curettage, Only if positive laser ablation of transformation zone |

|

| Outcomes | Histological status of LLETZ or colposcopic specimens Operators impression of significant peri-operative bleeding Women’s subjective opinion of peri-operative pain Women’s subjective opinion of post-operative severe discomfort, heavy discharge, severe bleeding Residual disease (cytology) at 3 and 6 months |

|

| Notes | 195 randomised to LLETZ, 180 to Laser All women had paracervical 1% lidocaine with 1:100,000 ephedrine LLETZ group: 6 treated by laser ablation due to technical problems, 4 failed to attend for treatment Laser group: 66 women did not require treatment, 114 required treatment 4 women were treated by LLETZ, 2 by cryosurgery due to technical problems |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Yes | Computer generation was used to assign women to either LLETZ or laser, “they (patients) were assigned a treatment strategy by computer-randomised forms” |

| Allocation concealment? | Yes | “Computer-randomised forms contained in sealed opaque envelopes”, were used as a method of concealment |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Unclear | Not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

No | % analysed: 190/375 (51%) and 107/375 (29%) for residual disease at 3 and 6 months respectively, “of the 190 who were compliant with follow up 3 months after treatment … 107 returned for a second evaluation at 6 months” All other outcomes assessed more than 51% of women. |

| Free of selective reporting? | Unclear | Insufficient information to permit judgement |

| Free of other bias? | Unclear | Insufficient information to assess whether an important risk of bias exists |

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | 204 women with entire squamo-columnar junction visible CIN 1 on 2 biopsies 3-6 months apart, CIN 2 or 3 not extending 3 mm into crypts No extension onto vagina or lesion or 12.5 mm into canal |

|

| Interventions | Cryotherapy Laser ablation |

|

| Outcomes | Operators impression of significant peri-operative bleeding >25cc Women’s subjective opinion of peri-operative pain (mild, moderate severe, Severe being that the woman would not consider the treatment again) Women’s subjective opinion of post-operative discomfort, heavy discharge, bleeding (none, mild, moderate, severe) Post operative cervical stenosis Satisfactory follow-up colposcopy at 3 months Berget 1991 reports longer follow up for residual disease outcome: residual disease (histological) at 3, 9, 15, 21, 33, 45, 80 months |

|

| Notes | 103 randomised to laser, 101 randomised to cryotherapy Laser performed ablated 2 mm lateral to transformation zone to a depth of 5-7mm Cryo coagulation (double freeze thaw freeze technique) or more if the ice ball did not exceed the probe (25mm) by 4 mm. Local analgesia was not routinely administered 6 laser and 2 cryotherapy women refused to be followed up Women were offered repeat treatment with the same method of treatment as part of protocol. 3 laser and 6 cryotherapy women refused repeat treatment |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | Not reported, “patients fulfilling the criteria were randomized to either laser or cryo treatment” |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Not reported |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Unclear | Not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Yes | For residual disease: % analysed: 187/204 (92%) Laser; 94/103 (91%) Cryotherapy; 93/101 (92%) All other outcomes had less loss to follow up |

| Free of selective reporting? | Unclear | Insufficient information to permit judgement |

| Free of other bias? | Unclear | Insufficient information to assess whether an important risk of bias exists |

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | 123 women with CIN1,2,3 | |

| Interventions | Laser conisation Knife conisation |

|

| Outcomes | Duration Peri-operative bleeding (quantity mls) Post-operative bleeding (primary requiring treatment and secondary) Post-operative pain (use of analgesics) Adequate colposcopy Cervical stenosis (failure to pass cotton swab) Women complaining of dysmenorrhoea Residual disease (3-36 months) |

|

| Notes | All procedures performed under general anaesthesia Knife cone biopsy women had vaginal packing for 24 hours and 3 gms Tranexamic acid for 10 days. Sturmdorf sutures were not used, lateral cervical arteries used Laser conisation women did not have vaginal packing or tranexamic acid 59 women randomised to laser conisation, 64 to knife conisation |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | Not reported |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Not reported |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Unclear | Not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Yes | For Inadequate colposcopy and cervical stenosis at follow up outcomes: % analysed: 113/123 (92%) Laser: 56/59 (95%) Knife: 57/64 (89%) All other outcomes had less loss to follow up |

| Free of selective reporting? | Unclear | Insufficient information to permit judgement |

| Free of other bias? | Unclear | Insufficient information to assess whether an important risk of bias exists |

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | 40 women with severe dysplasia/in situ carcinoma of the uterine cervix who underwent cervical conisation Mean age in the trial was 34.8 years (SD=5.7 years) There were 31 (77.5%) women with CIN II and 9 (22.5%) with CIN 3 |

|

| Interventions |

Interventions: Unipolar energy scalpel (Medizin-Elektronik Elektroton 300, MARTIN, Tuttlingen, Germany) Biopolar electrocautery scissors (Power Star; Ethicon, Inc, Somerville, NJ) Biopolar electrocautery scissors are easy to handle; they have the same shape as surgical scissors, with an isolated nylon handle, and the two blades are separated by a thin ceramic layer, thus producing two active bipolar electrodes |

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes | Primary haemorrhage was deduced by fact that, haemorrhages was for number of women, therefore it had to be a woman’s first haemorrhage Adequacy of margins of the lesion: bipolar scissors: 11/20, monopolar scalpel: 9/20 Healing of cervix: bipolar scissors: 28.3 days (SD=4.4 days), monoploar scalpel: 35.2 days (SD=6.3 days) Duration of recovery: bipolar scissors: 3.5 days (SD=1.5 days), monoploar scalpel: 6.4 days (SD=3.2 days) There were no infections in either group. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Yes | “Monopolar or bipolar assignment was obtained by means of a table of random digits” |

| Allocation concealment? | Yes | “Surgical methods were assigned randomly by drawing a sealed envelope … An independent party filled and sealed the envelopes which were placed in a sealed box” |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Unclear | Not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Yes | % analysed: 40/40 (100%) |

| Free of selective reporting? | Unclear | Insufficient information to permit judgement |

| Free of other bias? | Unclear | Insufficient information to assess whether an important risk of bias exists |

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | 400 women with histologically confirmed high grade squamous intraepithelial lesions Mean age in the trial was 32.4 years (SD=6.2 years) | |

| Interventions |

LEEP: For each loop procedure the cervix was injected with 4 ml of 1% lignocaine with 1:100 000 epinephrine 1-2 mm beneath the cervical surface epithelium at 12, 3, 6 and 9 o’clock positions. We used a large speculum adapted for smoke evacuation and a 2×2 cm electrode was used for large lesions and 1×1 cm electrode for the smaller lesions. The electrosurgical generator (Surgitron Ellman International, New York, USA) was operated using the cutting mode recommended by the manufacturer Cryotherapy: The PCG-R Portable Cryosurgical Gun (Spembly Medical Ltd, UK) was used for cryotherapy. A large speculum was placed into the vagina and after the lesion was identified by colposcopy an appropriate-sized probe to cover lesion and transformation zone was selected. A lubricant (KY jelly, Johnson and Johnson, South Africa) was applied to the probe before treatment of the cervix. The cervix was treated for 2 minutes, thawed and treated again for 2 minutes to allow an ice ball to form across the lesion and transformation zone |

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Yes | “Treatment allocation was performed by a research nurse in a separate setting in accordance with computer-generated randomisation sequences stratified per treatment” |

| Allocation concealment? | Yes | “Treatment allocation was performed … using consecutively numbered opaque sealed envelopes” |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Unclear | “The colposcopist was blinded with regard to treatment allocation”. However, it was unclear as to whether the outcome assessor was blinded |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Yes | For residual disease at 6 months: % of women analysed: 327/400 (82%) By treatment arm: LEEP: 159/200 (80%) Cryotherapy: 168/200 (84%) All other outcomes assessed more than 327 women. |

| Free of selective reporting? | Unclear | Insufficient information to permit judgement |

| Free of other bias? | Unclear | Insufficient information to assess whether an important risk of bias exists |

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | 80 women recruited with CIN 3 Women with a history of previous cervical surgery, peri- or post-menopausal or whose lesion extends to vagina |

|

| Interventions | Laser conisation LLETZ |

|

| Outcomes | Subjective scoring of pain by attendant nurse Subjective scoring of pain by women by linear analogue scale Peri-operative bleeding (none, spotting, requiring coagulation) Operative time |

|