Abstract

The DNA demethylating agent 5-azacytidine (5-azaC) has a teratogenic influence during rat development influencing both the embryo and the placenta. Our aim was to investigate its impact on early decidual cell proliferation before the formation of placenta. Thus, female Fischer rats received 5-azaC (5 mg/kg, i.p.) on the 2nd, 5th or 8th day of gestation and the decidual tissues were harvested on gestation day 9. They were then analysed immunohistochemically for expression of cell proliferation marker proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) in decidual cells and for global DNA methylation using the coupled restriction enzyme digestion, random amplification and pyrosequencing assays. We found that 5-azaC administered on the 5th and 8th (but not on 2nd) day of gestation led to increased PCNA expression in decidual cells compared with untreated controls. No significant changes in DNA methylation were detected, with either method, in any of the treated rat groups compared with untreated controls. Thus, we conclude that 5-azaC can stimulate decidual cell proliferation without simultaneously changing global DNA methylation level in treated cells.

Keywords: 5-azacytidine, decidua, DNA demethylation, proliferating cell nuclear antigen, rat, teratogen

Teratogen 5-azacytidine (5-azaC) is an analogue of cytosine and, thus, can be incorporated into the DNA chain in its place. In the fifth position of its pyrimidine ring, 5-azaC contains a nitrogen instead of a carbon atom, rendering it unable to accommodate the methyl group (Brank et al. 2002). The result of that change is the absence of DNA methylation on the site of 5-azaC incorporation (demethylation) and, consequently, a possible change in gene activity. As the differential gene expression has to be precisely regulated during gestation to assure normal embryonic and foetal development, changes in gene expression caused by the action of 5-azaC during pregnancy are thought to be the main reason for its marked teratogenic activity. In rats 5-azaC causes pronounced reduction in foetal growth and numerous skeletal malformations, particularly in the extremities (Vlahovic et al. 1999; Sincic et al. 2002), whereas in the placenta, it inhibits its growth and causes disordered placental structure and membrane glycoprotein expression (Serman et al. 2008).

Upon trophoblast invasion uterine endometrium responds with decidualization, a process of morphological and functional differentiation of stromal cells into specialized decidua cells, a key component of placental development and embryo implantation (Hess et al. 2007). Cellular differentiation, proliferation and apoptosis (Akcali et al. 2003; Penchalaneni et al. 2004) and changes in expression of extracellular matrix proteins (Iwahashi et al. 1996) are necessary for such uterine transformation.

Decidualization starts at the moment of establishment of communication between the trophoblast of the blastocyst and the uterine epithelium, with the purpose of establishing a common tissue. This tissue is simultaneously capable of regulating the trophoblast invasion from the side of the embryo and of immunological reaction from the mother's side (Gellersen et al. 2007). The decidual transformation is a precise, genetically regulated process, and its gene expression is controlled by, among other mechanisms, DNA methylation (Lind et al. 2007).

We previously found that administration of 5-azaC in the peri-implantation period (5th day of gestation) results in failure of labyrinth development in rat placentas and also in pronounced increase in trophoblast cell proliferation, determined by high proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) expression. If treated on gestation day 8, placentas become even more disorganized, but the PCNA expression levels drop to the lowest levels compared with control placentas (Serman et al. 2007).

These results led us to analyse in more detail the effects of 5-azaC on rat placental development during the critical gestation period (days 2–8) in a separate study of decidual proliferation. Decidual formation was investigated during the period of the yolk sac placenta, before the development of the hemochorial labyrinthine placenta. The proliferation of decidual cells was determined immunohistochemically using widely used marker of cell proliferation, PCNA (Maga & Hubscher 2003) and compared with levels of global DNA methylation in deciduas.

Materials and methods

Animals

Female Fisher rats were mated overnight and the appearance of the vaginal plug designated the day 0 of gestation. Pregnant females were injected intraperitoneally with 5-azaC, dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), at a concentration of 5 mg/kg of body mass on the 2nd, 5th or 8th day of gestation (six rats per group), whereas the control animals (n = 6) were not treated.

Ethical Approval

Animal experiments comply with local and national guidelines governing the use of experimental animals and were approved by the Ethical Committee, School of Medicine, University of Zagreb.

Isolation of deciduas

Pregnant females were euthanized on the morning of the 9th day of gestation. The abdominal cavity was opened, and the uterine horns held with forceps during separation of the mesometrium. Subsequent isolation procedures were carried out in sterile conditions under the dissecting microscope. The uterine wall was opened with the aid of watchmaker's forceps, and the deciduas were isolated. A total of 180 deciduas were collected: 50, 38 and 40 from 5-azaC given the 2nd, 5th and 8th day of gestation groups respectively, and 52 from control rats (an average of seven to eight deciduas per pregnant rat).

Histology and immunohistochemistry

After fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4 °C and dehydration, deciduas were transferred to paraffin, sectioned in 5-μm-thin slices, deparaffinized and stained with haematoxylin and eosin. For immunohistochemistry, serially cut sections were placed on silanized slides (S 3003; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark), air-dried for 24 h at room temperature, deparaffinized and placed in a PBS buffer (pH 7.4). After blocking with goat serum for 30 min, slides were incubated with monoclonal mouse anti-PCNA antibodies (clone PC10, cat. #M 0879; Dako) (1:100 dilution), for 2 h at 4 °C. For negative controls, incubation with primary antibodies was omitted. ARK (Animal Research Kit) Peroxidase (Dako), containing DAB chromogen, was used for primary antibody visualization, according to the manufacturer's instructions. Slides were then counterstained with haematoxylin and covered with 50% glycerol in PBS.

Quantitative stereological analysis of numerical density

Proliferating cell nuclear antigen-positive cells were analysed stereologically in randomly selected paraffin blocks of decidua tissues. Five consecutive serial sections were taken in a random fashion from each series. Quantitative stereological analysis of numerical density (Nv) was performed by Nikon Alphaphot binocular light microscope (Nikon, Vienna, Austria) using Weibel's multipurpose test system with 42 points (M 42) at 400× magnification (Weibel 1979). The area tested (At) was 0.0837 mm2. For each investigated group, the orientation/pilot stereological measurement was carried out in order to define the number of fields to be tested (Bulic-Jakus et al. 1999). The numerical density of PCNA-positive cells was determined by the point counting method. Nv was calculated by formula: Nv = N/At × D, where N was the number of PCNA-positive cells on tested area (Wicksell 1925, 1926). The mean tangential diameter (D), calculated by light microscopy at 400× magnification, was 0.013 mm for 100 cells.

Global DNA methylation analysis

Coupled restriction enzyme digestion and random amplification assay

Paraffin embedded tissues of three randomly chosen deciduas from each experimental group were treated with xylene, heated to 55 °C for 15 min and centrifuged at 16,000 g for 2 min at room temperature. Xylene was decanted and the whole procedure repeated. Absolute ethanol was added to the samples and incubated at room temperature for 15 min. After centrifugation, absolute ethanol was decanted and the procedure was repeated once more.

DNA extraction buffer (500 μl; 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-Cl, 25 mM EDTA, 0.5% SDS, pH 8) was added to the air-dried tissues, and 0.1 mg/ml of Proteinase K was added to the mixture. Samples were incubated at 37 °C overnight, and the next day 25 U of RNaze A was added. The incubation continued for 1 h before the same amount of phenol was added to the mixture and shaken by hand for 10 s. Each sample was centrifuged for 10 min (16,000 g, 10 °C), and the water phase removed and transferred into microtube. The phenol extraction procedure was repeated once more before extraction with chloroform. After the addition of chloroform the microtube was shaken by hand, centrifuged for 10 min (16,000 g, 10 °C) and the DNA precipitated with two volumes of ice-cold absolute ethanol. The samples were then centrifuged for 10 min (16,000 g at 10 °C), DNA pellet was washed once with ice-cold 70% ethanol, centrifuged as above, and the ethanol removed by decanting. The pellet was air-dried, and 50 μl of the sterile, ultrapure water was added. DNA concentration was measured using NanoDrop (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

DNA methylation was analysed using coupled restriction enzyme digestion and random amplification (CRED-RA) assay (Cai et al. 1996). Total digestion of 1.2 μg of DNA from each sample was performed using isoschizomers, either HpaII or MspI (Fermentas, Vilnius, Lithuania), in standard buffer provided by the manufacturer, at 37 °C, overnight in 25 μl reaction volume (5 U of enzymes per μg DNA). Isoschizomers HpaII and MspI cut the 5′-C/CGG-3′ sequence, but each enzyme differs in its sensitivity to cytosine methylation. HpaII cuts very weakly if the outer C is methylated and does not cut at all if the inner C is methylated. MspI cuts if the inner C is methylated, but cannot cleave if the outer or both Cs are methylated. Therefore, the dominant DNA methylation differences considered by this method correspond to the methylation of inner C detected as specific electrophoretic band present in HpaII digest and absent in MspI digest. All other rarely obtained situations were excluded from analysis.

Complete digestion was confirmed with electrophoresis of 5 μl of each reaction mixture on a 1% agarose gel (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), 1 × TBE, stained with Stain G (Serva, Heidelberg, Germany) and examined under UV light. The resulting fragments of approximately 200 ng DNA were amplified by PCR method using three different primers (OPL-07 5′-AGG CGG CAA C-3′, OPL-13 5′-ACC GCC TGC T-3′ and OPBB-09 5′-AGG CCG GTC A-3′; Operno Technologies Inc., Alameda, CA, USA) in five different combinations: PCR1 − OPL-13; PCR2 − OPL-07 + OPL-13; PCR3 − only OPL-07; PCR4 − only OPBB-09; and PCR5 − OPL-07 + OPBB-09. Each reaction was performed in a total volume of 25 μl containing 2.5 μl of 10× PCR buffer, 3.0 mM of MgCl2 (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), 200 μM dNTP (Promega), 0.4 μM of each primer (alternatively double amount of primer was used in one-primer reactions) and 1 U of Taq polymerase (Promega). Initial denaturation temperature was 95 °C for 3 min followed by 38 cycles of denaturation (95 °C for 1 min), annealing (35 °C for 1 min) and elongation (72 °C for 2 min). Final extension was carried out at 72 °C for 7 min. PCR was performed in thermal cycler 2720 version 2.08 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Amplicons were separated on 1.5% agarose gels, 1 × TBE and visualized with DNA stain G (Serva). Differences in the electrophoretic patterns that resulted from total digestion with HpaII or MspI and amplification of the digested DNA fragments with individual primers or primer combinations represented the criteria for evaluating the level of DNA methylation. The first stage in data analysis was to determine the total number of unique bands and the banding patterns of all DNA samples produced by one primer. Then the presence/absence of each band in each primer-specific electrophoretic pattern was recorded. As a positive control uncut DNA was amplified with all tested primer combinations and obtained fragments were primer specific and almost identical in every sample, indicating that absence of electrophoretic fragments obtained after digestion with isoshizomers is related to DNA methylation. The differences that were not related to methylation were detected only sporadically and excluded from data analysis.

For each primer combination, experiments were performed in three independent repetitions and only clearly and consistently reproducible bands were counted and analysed using the rapddistance (ver. 1.04) computer program (Armstrong et al.). The relationship between HpaII- and MspI-cut DNA samples was calculated using the algorithm for estimating DNA sequence divergence based on a comparison of restriction endonuclease digests (Apostol et al. 1993).

Repetitive element pyrosequencing assay

Three randomly chosen deciduas from each experimental group were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4 °C. After dehydration, the specimens were transferred to paraffin and 10–11 sections (5 μm thick) per decidua were cut. Paraffin was removed by incubating slides in xylene (twice for 5 min), followed by incubation in 100%/95%/70% ethanols (3 min each) and water. Ectoplacental cones or areas of lateral decidual cells were carefully scrapped and brought into the DNA extraction buffer [TE (pH 9) with 0.1 Ag/AL of Proteinase K and 0.25% of Nonidet P40] and incubated at 56 °C. After 24 h, samples were heated for 10 min at 95 °C to inactivate Proteinase K. Genomic DNA extracts were spun and frozen at −20 °C. Bisulphite modification of genomic DNA was performed using the EZ DNA Methylation Kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Hot-start PCR of bisulphite modified gDNA was performed (HotStarTaq Master Mix kit; Qiagen, Venlo, the Netherlands) using already published primer set (Kim et al. 2007). For analysis of global DNA, we used published pyrosequencing assay (Kim et al. 2007) on PSQ 96MA, Biotage pyrosequencing system.

Statistical analysis

The stereological data for PCNA-positive cells were evaluated by descriptive statistics. Distribution of the data was assessed by Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, Lilliefors test and Shapiro–Wilks W-test. The homogenicity of the variance was tested by Lavens test. Differences in Nv of PCNA-positive cells in experimental groups were analysed with multiple analyses of variance (manova) with the post hoc LSD test. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using statistica 6.0 software (Stat Soft, Tulsa, OK, USA).

For analysis of data obtained by pyrosequencing, one-way anova Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunns Post-test was used. Statistical analysis of CRED-RA data was performed using Duncan's New Multiple Range Test.

Results

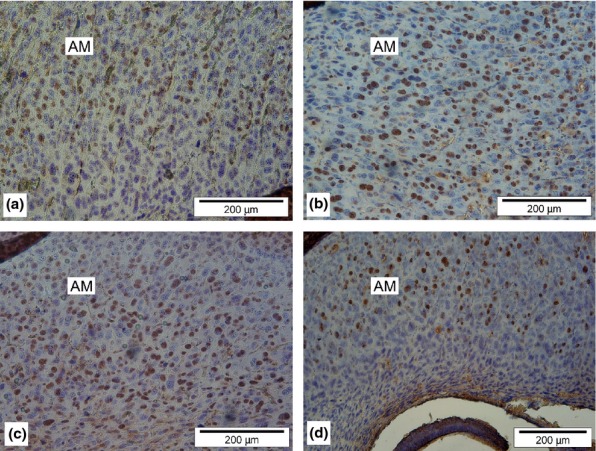

Proliferative capacity of decidual cells was determined immunohistochemically by measuring the number of PCNA-positive cells in pregnant rats treated with 5-azaC on the 2nd (pre-implantation period), 5th (implantation period) and 8th (pregastrulation period) day of gestation and compared them with those of untreated, control rats (Figure 1 and Table 1). One randomly chosen decidua (on two separate glass slides) from all six rats in each of the experimental and control groups was taken for analysis (total of 24 deciduas, or 48 slides).

Figure 1.

PCNA expression in rat decidua cells. Deciduas from female rats treated with 5-azaC on the 2nd (a), 5th (b) and 8th (c) day of gestation and a decidua from untreated control rat (d). DAB chromogen, counterstained with haematoxylin. AM, anti-mesometrial decidua.

Table 1.

Numerical density (Nv) of the PCNA expression in decidua

| Day of treatment | Nv/mm3 |  |

SD | SE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2nd day | 5azaC | 17,788 | 5345 | 535 |

| 5th day | 5azaC | 40,896 | 7257 | 726 |

| 8th day | 5azaC | 36,117 | 7900 | 790 |

| Control | 17,200 | 5046 | 505 |

Stereological analysis revealed higher Nv for PCNA in experimental groups treated with 5-azaC on either 5th or 8th day of gestation compared with untreated controls. However, rats treated with 5-azaC on the 2nd day of gestation showed no such difference when compared to untreated controls (Table 1).

The significance between the mean Nv values of the analysed groups was tested by LSD test (post hoc analysis). The most pronounced proliferation was detected in decidual cells of the experimental group treated with 5-azaC on the 5th day of gestation (Figure 1b), which was significantly higher than in deciduas treated on the 8th day of gestation (Figure 1c). Experimental group treated on the 2nd day of gestation, which did not statistically differ from the controls (Figure 1a), had the lowest Nv for PCNA.

Global DNA methylation analysis determined by CRED-RA method showed no statistically significant differences in decidual methylation status between 5-azaC treated and non-treated rats (Table 2). Thus, the total values of decidua DNA methylation levels from rats treated on gestation days 2, 5 and 8 were 0.28, 0.37 and 0.37, respectively, whereas in control rats, the measured value was 0.32.

Table 2.

Methylation of cytosine in deciduoma cells of rats treated with 5-azacytidine. DNA-banding patterns obtained by coupled restriction enzyme digestion and random amplification followed by electrophoresis were analysed using the RAPDDISTANCE software (Armstrong et al. http://www.anu.edu.au/BoZo/software). The numerical values represent criteria for DNA methylation and are obtained by using algorithm specific for estimating DNA sequence divergence based on a comparison of restriction endonuclease digests

| Treatment with 5-azacytidine on gestation day | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primer combination | 2nd GD | 5th GD | 8th GD | Untreated control |

| OPL-13 | 0.19 | 0.50 | 0.44 | 0.38 |

| OPL-07 + OPL-13 | 0.22 | 0.39 | 0.33 | 0.39 |

| OPL-07 | 0.45 | 0.30 | 0.40 | 0.20 |

| OPBB-09 | 0.22 | 0.23 | 0.32 | 0.27 |

| OPL-07 + OPBB-09 | 0.31 | 0.43 | 0.38 | 0.38 |

| Mean | 0.28 | 0.37 | 0.37 | 0.32 |

Statistical analysis of data was performed using Duncan's New Multiple Range Test.

Means were not significantly different at the 95% level of confidence! GD-gestation day.

Statistical analysis of data was performed using Duncan's New Multiple Range Test with means not significantly different at the 95% level of confidence.

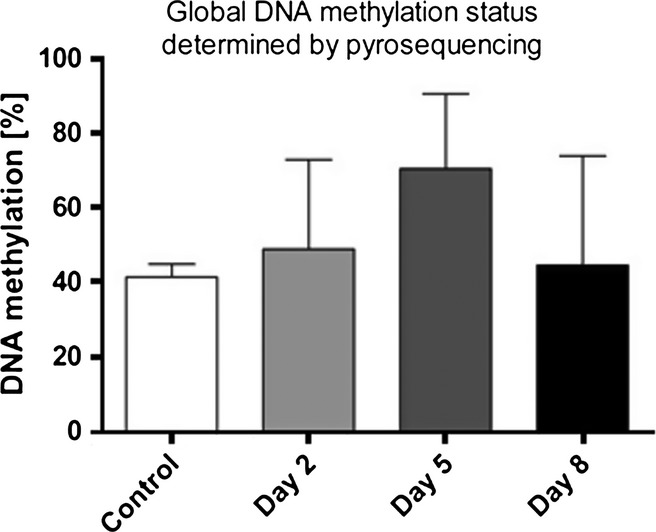

We found no statistically significant difference in global DNA methylation status in decidual samples analysed by pyrosequencing assay as well (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Global DNA methylation status determined by pyrosequencing. 5azaC did not induce any statistically significant change in global DNA methylation (P = 0.8346, Kruskal–Wallis test).

Discussion and conclusion

In this study, stage-specific changes in proliferative capacity of decidual cells, induced by the teratogen and the DNA demethylating agent 5-azacytidine, are described.

Decidual cells formation is the result of uterine endometrial decidualization, a process which is an important prerequisite for successful embryo implantation (Yuhki et al. 2011). Decidualization is characterized by tissue morphological changes and by active synthesis of prolactin and insulin-like growth factor binding protein 1 (IGFBP-1) (Gellersen et al. 2007). Unlike in humans, where decidualization spontaneously develops during each menstrual cycle, decidualization in rats requires a stimulus, in the form of embryo implantation, to commence. In rats, anti-mesometrial decidua develops first, situated opposite from the placental attachment site, and then regresses entirely with the progression of gestation, whereas permanent mesometrial decidua develops on the opposite side (Fonseca et al. 2012).

Exposure of human endometrial cell lines in vitro with decitabine (demethylating agent 5-Aza-2′-deoxycytidine) initiates a decidualization-like response and up-regulation of decidual markers prolactin and IGFBP1, although at the level of protein expression, no differences are found compared with untreated endometrial cell lines (Logan et al. 2010).

We have used immunohistochemical analysis of PCNA cell proliferation marker expression to determine the impact of DNA demethylating agent 5-azaC on proliferation of rat decidual cells. Results showed that 5-azaC administered to rats on the 2nd day of gestation caused no change in the proliferative capacity of decidual cells. However, as demethylation is widespread during the early phases of mammalian development (Heby 1995), it is possible that the demethylating agent applied as early as the 2nd day of gestation does not have an impact on decidual cells at all.

The level of methylation was shown to be lowest in the blastocyst and at the pregastrulation stage, when the process of de novo methylation commences (Novakovic & Saffery 2012). The epigenetic reprogramming of the somatic cell lineages of the embryonic genome and trophoblast cell lineages are occurring simultaneously (Heby 1995). We have now shown that treatment with DNA demethylating agent 5-azaC on the 5th day of gestation (implantation period) and on the 8th day of gestation (pregastrulation period) causes pronounced changes in decidual cell proliferation.

Although direct correlation between transcription of the PCNA gene and DNA methylation has not been found (Liu et al. 1993), our results indicate that certain correlation between the methylation and expression of PCNA gene is unquestionable. Namely, administration of 5-azaC causes statistically significant rise of Nv value for PCNA, both in the experimental group treated with 5-azaC on the 5th day of gestation and in the experimental group treated on the 8th day of gestation. Differences did not exist only in the first experimental group (treatment on the 2nd day of gestation) which may be related to the low degree of DNA methylation in this period of development (Reik et al. 2003).

Results presented here, on the effects of the 5-azaC on decidual proliferation, undoubtedly point to the DNA methylation as the mechanism crucially important for the development of future placenta, especially for its decidual part. Gathering knowledge on the regulation of placental development at the epigenetic level is of great importance for understanding all the future events in the process of placentation; thus, future research should concentrate on discovery and identification of genes whose expressions are regulated at the level of DNA methylation.

Although a number of such genes, related to mouse placental development, have already been described, it is necessary to widen the search in a rat model as well. Namely, whereas the trophoblast invasion in mice stops at the border between endometrium and myometrium, it was recently found that the trophoblast invasion in rats is much deeper, that is, analogous to the trophoblast invasion in humans (Pijnenborg et al. 2004). This fact has been recognized long ago by histologist and embryologist Mathias Duval in his studies on the sites of implantation and placentation in mice and rats. He described the existence of the ‘mesometrial triangle’, which reaches into myometrium (Pijnenborg & Vercruysse 2003). Future research should exploit this fact and broaden it in the direction of epigenetic regulation of expression of genes of importance for the development of placenta, both at the protein level and at the level of mRNA expression.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mariana Druga for technical support and assistance, and Dr Natasa Delimar for help in statistical analysis of results. This work was supported by research grant from the Ministry of Science, Republic of Croatia: 108-1080399-0335, 119-1191192-1215 and support-grant (F. Bulic-Jakus) from the University of Zagreb, Croatia.

Authorship

All listed authors meet ICMJE authorship criteria.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

References

- Akcali KC, Gibori G, Khan SA. The involvement of apoptotic regulators during in vitro decidualization. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2003;149:69–75. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1490069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apostol BL, Black WC4th, Miller BR, Reiter P, Beaty BJ. Estimation of the number of full sibling families at an oviposition site using RAPD-PCR markers: applications to the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1993;86:991–1000. doi: 10.1007/BF00211052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brank AS, Eritja R, Garcia RG, Marquez VE, Christman JK. Inhibition of Hhal DNA (Cytosine-C5) methyltransferase by oligodeoxyribonucleotides containing 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine: examination of the intertwined roles of co-factor, target, transition, state structure and enzyme conformation. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;323:53–67. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00918-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulic-Jakus F, Vlahovic M, Juric-Lekic G, Crnek-Kunstelj V, Serman D. Gastrulating rat embryo in a serum-free culture model: changes of development caused by teratogen 5-azacytidine. Altern. Lab. Anim. 1999;27:925–933. doi: 10.1177/026119299902700601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai QY, Guy CL, Moore GA. Detection of cytosine methylation and mapping of a gene influencing cytosine methylation in the genome of Citrus. Genome. 1996;39:235–242. doi: 10.1139/g96-032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca BM, Correia-da-Silva G, Teixeira NA. The rat as an animal model for fetoplacental development: a reappraisal of the post-implantation period. Reprod. Biol. 2012;12:97–118. doi: 10.1016/s1642-431x(12)60080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gellersen B, Brosens IA, Brosens JJ. Decidualization of the human endometrium: mechanisms, functions, and clinical perspectives. Semin. Reprod. Med. 2007;25:445–453. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-991042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heby O. DNA methylation and polyamines in embryonic development and cancer. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 1995;39:737–757. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess AP, Hamilton AE, Talbi S, et al. Decidual stromal cell response to paracrine signals from the trophoblast: amplification of immune and angiogenic modulators. Biol. Reprod. 2007;76:102–117. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.106.054791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwahashi M, Ooshima A, Nakano R. Increase in the relative level of type V collagen during development and ageing of the placenta. J. Clin. Pathol. 1996;49:916–919. doi: 10.1136/jcp.49.11.916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HH, Park JH, Jeong KS, Lee S. Determining the global DNA methylation status of rat according to the identifier repetitive elements. Electrophoresis. 2007;28:3854–3861. doi: 10.1002/elps.200600733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lind GE, Skotheim RI, Lothe RA. The epigenome of testicular germ cell tumors. APMIS. 2007;115:1147–1160. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2007.apm_660.xml.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YW, Chang KJ, Liu YC. DNA methylation is not involved in growth regulation of gene expression of proliferating cell nuclear antigen. Exp. Cell Res. 1993;208:479–484. doi: 10.1006/excr.1993.1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan PC, Ponnampalam AP, Rahnama F, Lobie PE, Mitchell MD. The effect of DNA methylation inhibitor 5-Aza-2′-deoxycytidine on human endometrial stromal cells. Hum. Reprod. 2010;25:2859–2869. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deq238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maga G, Hubscher U. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA): a dancer with many partners. J. Cell Sci. 2003;116:3051–3060. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novakovic B, Saffery R. The ever growing complexity of placental epigenetics – role in adverse pregnancy outcomes and fetal programming. Placenta. 2012;33:959–970. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penchalaneni J, Wimalawansa SJ, Yallampalli C. Adrenomedullin antagonist treatment during early gestation in rats causes fetoplacental growth restriction through apoptosis. Biol. Reprod. 2004;71:1475–1483. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.032086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pijnenborg R, Vercruysse L. Thomas Huxley and the rat placenta in the early debates on evolution. Placenta. 2003;25:233–237. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2003.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pijnenborg R, Aplin JD, Ain R, et al. Trophoblast and the endometrium – a workshop report. Placenta. 2004;(Suppl. A):S42–S44. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2004.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reik W, Santos F, Dean W. Mammalian epigenomics: reprogramming the genome for development and therapy. Theriogenology. 2003;59:21–32. doi: 10.1016/s0093-691x(02)01269-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serman L, Vlahovic M, Sijan M, et al. The impact of 5-azacytidine on placental weight, glycoprotein pattern and proliferating cell nuclear antigen expression in rat placenta. Placenta. 2007;28:803–811. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serman L, Sijan M, Kuzmic R, et al. Changes of membrane proteins expression in rat placenta treated with 5-azacytidine. Tierarztl. Umsch. 2008;63:391–395. [Google Scholar]

- Sincic N, Vlahovic M, Bulic-Jakus F, Serman L, Serman D. Acetylsalicylic acid protects rat embryos from teratogenic effects of 5-azacytidine. Period. Biol. 2002;104:441–444. [Google Scholar]

- Vlahovic M, Bulic-Jakus F, Juric-Lekic G, Fucic A, Maric S, Serman D. Changes in the placenta and in the rat embryo caused by demethylating agent 5-azacytidine. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 1999;43:843–846. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weibel ER. Stereological Methods, Vol. 1, Practical Methods for Biological Morphometry. London: Academic Press; 1979. pp. 1–415. [Google Scholar]

- Wicksell SD. The corpuscle problem. A mathematical study of a biometric problem. Biometrika. 1925;17:84–99. [Google Scholar]

- Wicksell SD. The corpuscle problem. Second memoir. Case of ellipsoidal corpuscles. Biometrika. 1926;18:151–172. [Google Scholar]

- Yuhki M, Kajitani T, Mizuno T, Aoki Y, Maruyama T. Establishment of an immortalized human endometrial stromal cell line with functional responses to ovarian stimuli. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2011;9:104. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-9-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]