Abstract

Background

Vulval intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) is a pre-malignant condition of the vulval skin. This uncommon chronic skin condition of the vulva is associated with a high risk of recurrence and the potential to progress to vulval cancer. The condition is complicated by its’ multicentric and multifocal nature. The incidence of this condition appears to be rising particularly in the younger age group.

There is a lack of consensus on the optimal surgical treatment method. However, the rationale for surgical treatment of VIN has been to treat symptoms and exclude underlying malignancy with the continued aim of preservation of vulval anatomy and function. Repeated treatments affect local cosmesis and cause psychosexual morbidity thus impacting on the patients’ quality of life.

Objectives

To evaluate the effectiveness and safety of surgical interventions for high grade VIN.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Issue 3, 2010, Cochrane Gynaecological Cancer Group Trials Register, MEDLINE and EMBASE up to September 2010. We also searched registers of clinical trials, abstracts of scientific meetings, reference lists of included studies and contacted experts in the field.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that compared surgical interventions, in adult women diagnosed with high grade vulval intraepithelial neoplasia.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently abstracted data and assessed risk of bias.

Main results

We found only one RCT which included 30 women that met our inclusion criteria and this trial reported data on carbon dioxide laser (CO2 laser) versus ultrasonic surgical aspiration (USA).

There was no statistically significant difference in the risk of disease recurrence after one year follow-up, pain, presence of scarring, dysuria or burning, adhesions, infection, abnormal discharge and eschar between women who received CO2 laser and those who received USA. The trial lacked statistical power due to the small number of women in each group and the low number of observed events, but was at low risk of bias.

Authors’ conclusions

The included trial lacked statistical power due to the small number of women in each group and the low number of observed events. Therefore in the absence of reliable evidence regarding the effectiveness and safety of the two surgical techniques for the management of vulval intraepithelial neoplasia precludes any definitive guidance or recommendations for clinical practice.

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH): Carcinoma in Situ [pathology; *surgery]; Lasers, Gas [*therapeutic use]; Precancerous Conditions [pathology; *surgery]; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Suction [methods]; Ultrasonic Therapy [instrumentation; *methods]; Vulvar Neoplasms [pathology; *surgery]

MeSH check words: Adult, Female, Humans

BACKGROUND

Description of the condition

Vulval intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) is a condition in which pre-cancerous changes occur in the skin that covers the vulva of the female external genital organs. VIN can affect women at any age but most recent studies suggest it is more common under the age of 50 (Jones 2001). VIN is diagnosed by examination of a vulval biopsy and histologically has been classified as either low grade (VIN 1) or high grade (VIN 2/3). In 2004, the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease (ISSVD) Vulvar Oncology society modified this classification to reflect the two divergent types of VIN; the human papilloma virus (HPV) related type which precedes almost all vulval cancers in women under 45 and is described as usual type VIN, and the lichen sclerosus-related type causing vulval cancer in older women and is known as differentiated VIN (van derAvoort 2006). The VIN may be asymptomatic or present with a mixed variety of symptoms such as itching, discomfort, burning , painful intercourse and whitish patches over the vulva. These symptoms alone can lead to considerable morbidity. The concern with VIN however is the further development of this condition to cancer of the vulva. The true rate of progression to invasive vulval cancer in women with untreated high-grade VIN is debatable, although some studies suggest a rate as high as 9% (van Seters 2002), while the risk of progression in treated lesions over a period of years has been reported as between 2% and 5% (Jones 2001). A woman’s risk of developing cancer of the vulva by the age of 75 varies between countries, ranging from 0.01% to 0.28% , which corresponds to 0 to 3 cases per year in 100,000 women under 75 years (IARC 2002). More recently an increase in vulval cancer in women under the age of 50 has been documented (Joura 2000; Jones 1997; ONS 2004; WCISU 2004). This rising trend has been linked to increasing incidence of VIN in younger women which has been attributed to infection with HPV, smoking or a poor immunological status. Effective treatments for vulval cancer are available; however, they are associated with considerable morbidity.

Description of the intervention

The treatment of VIN depends on the grade and location on the vulva. VIN1 is generally monitored with comprehensive vulvoscopy and inspection of the perianal region; with liberal biopsying of any suspicious areas to ascertain progression to high grade disease. VIN 2/3 lesions are considered to have a high propensity for malignant conversion hence they are managed actively. Historically lesions of VIN were excised or ablated. Popular surgical treatment modalities include carbon dioxide (CO2) laser vaporization or ablation and surgical excision. Laser vaporisation involves destruction of the skin using pulsed laser which fails to provide tissue for histology whereas surgical excision involves removal of disease without the disadvantage of the former. Depending on the extent of the lesion surgery involves either a local excision, a hemi-vulvectomy or a simple vulvectomy. However, full vulvectomy is rarely indicated. Due to the disfiguring nature of these procedures and the younger population of women being treated, less invasive modalities were developed; many of which are still being evaluated such as photodynamic therapy (Hillemanns 2000) and more recently the topical use of immune modulators (Le 2007; Mathiesen 2007). Following recent studies the latter treatment has gained popularity and appears to be a promising treatment option for VIN in younger women who wish to maintain sexual activity and avoid radical surgery provided cancer is absent (Tristam 2005).

Why it is important to do this review

There is no consensus on the optimal management of high grade VIN. The ideal management of these patients is complicated by the broad age range, extent and occasional multifocal nature of this condition with a risk of recurrence of over 50%. Surgical intervention is often associated with deformity and loss of vulvar function which has significant somatic and psychosexual morbidity. More importantly, VIN and vulval cancer are being diagnosed in younger women where traditional surgical treatment would be warranted. A parallel systematic review examining medical management is being carried out. The impact of the various surgical interventions on the risk of recurrence and progression to vulval cancer remains unknown and thus, there was a need for a formal appraisal of the evidence available for effective surgical management of VIN.

OBJECTIVES

To evaluate the effectiveness and safety of surgical interventions for high grade VIN.

METHODS

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs)

Types of participants

Women aged over 18 years with a confirmed histological diagnosis of high-grade VIN. Women with either unifocal or multifocal disease of the vulva were included; those with a histological diagnosis of Paget’s were excluded. Trials that studied the management of vulval carcinoma were excluded.

Types of interventions

Intervention:

excisional (including wide local excision and simple vulvectomy)

ablative (CO2 and laser vaporisation)

excision and laser vaporisation as a combined technique

Control

observation

We additionally considered any direct comparisons between excisional and laser ablative surgical techniques, as well as comparing excisions and ablations with observation only.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Response to treatment (based on clinical and/or histological assessment for resolution, regression, persistence or progression of VIN).

Recurrence on long term follow up of high grade VIN (at 2 and 5 yrs).

Progression to vulval cancer.

Secondary outcomes

Quality of life (QoL), as measured by a validated scale

Sexual function, using a validated tool. e.g. the Sabbatsberg sexual self-rating scoring system (Garrat 1995; Naransingh 2000)

Control of symptoms i.e. Pain, Pruritis, Soreness and Superficial Dyspareunia.

- Adverse events classified according to CTCAE 2006:

- direct surgical morbidity (death within 30 days, injury to bladder, ureter, vascular, small bowel or rectum, wound healing), febrile morbidity, haematoma, local infection, indwelling catheter)

- surgically related systemic morbidity (chest infection, thrombo-embolic events (deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism), cardiac events (cardiac ischemias and cardiac failure), cerebrovascular accident

- long-term pain

- unscheduled re-admission, delayed discharge

Search methods for identification of studies

Papers in all languages were sought and translations carried out when necessary.

Electronic searches

See: Cochrane Gynaecological Cancer Group methods used in reviews.

The following electronic databases will be searched:

The Cochrane Gynaecological Cancer Collaborative Review Group’s Trial Register

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (Central), Issue 3, 2010

MEDLINE

EMBASE

The Medline, Embase and Central search strategies aiming to identify RCTs comparing surgical interventions of high grade VIN before September 2009 are presented in Appendix 1, Appendix 2 and Appendix 3 respectively.

Databases were searched up to September 2010.

All relevant articles found were identified on PubMed and using the ‘related articles’ feature, a further search was carried out for newly published articles.

Searching other resources

Unpublished and Grey literature

Metaregister, Physicians Data Query, www.controlled-trials.com/rct, www.clinicaltrials.gov and www.cancer.gov/clinicaltrials were searched for ongoing trials.

Handsearching

Reports of conferences were handsearched in the following sources:

Gynecologic Oncology (Annual Meeting of the American Society of Gynecologic Oncologist).

International Journal of Gynecological Cancer (Annual Meeting of the International Gynecologic Cancer Society).

British Journal of Cancer.

British Cancer Research Meeting.

Annual Meeting of European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO).

Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

Reference lists and Correspondence

The citation lists of included studies were checked and experts in the field contacted to identify further reports of trials. Two experts (Mr R Naik and Miss A Tristam) in the field were contacted who confirmed that there were currently no trials underway that assessed surgical interventions for the management of VIN.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

All titles and abstracts retrieved by electronic searching were downloaded to the reference management database Endnote, duplicates were removed and the remaining references examined by two review authors (LP, SK) independently. Those studies which clearly did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded and copies of the full text of potentially relevant references were obtained. The eligibility of retrieved papers were assessed independently by two review authors (LP, SK). Disagreements were resolved by discussion between the two review authors and where necessary by a third review author (AN). Reasons for exclusion are documented.

Data extraction and management

For included studies, data were abstracted as recommended in chapter 7 of the Cochrane Handbook 2008. This included data on the following:

Author, year of publication and journal citation (including language)

Country

Setting

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Study design, methodology

- Study population

- ○ Total number enrolled

- ○ Patient characteristics

- ○ Age

- ○ co-morbidities

- ○ Previous treatment

- VIN details

- ○ grade

- ○ size of lesion

- ○ unifocal or multifocal lesion

- Intervention details: Surgery or Control

- ○ For surgical interventions: Type of excision or ablation

Risk of bias in study (see below)

Duration of follow-up

- Outcomes - response to treatment, QoL, sexual function, symptom assessment, and adverse events.

- ○ For each outcome: Outcome definition (with diagnostic criteria if relevant);

- ○ Unit of measurement (if relevant);

- ○ For scales: upper and lower limits, and whether high or low score is good

- ○ Results: Number of participants allocated to each intervention group;

- ○ For each outcome of interest: Sample size; Missing participants

Data on outcomes were extracted as below:

For dichotomous outcomes (e.g. adverse events or number of patients with disease recurrence as it was not possible to use a hazard ratio), we extracted the number of patients in each treatment arm who experienced the outcome of interest and the number of patients assessed at endpoint, in order to estimate a risk ratio (RR).

For continuous outcomes (e.g. subjective pain), we extracted the final value and standard deviation of the outcome of interest and the number of patients assessed at endpoint in each treatment arm at the end of follow-up, in order to estimate the mean difference (if trials measured outcomes on the same scale) or standardised mean differences (if trials measured outcomes on different scales) between treatment arms and its standard error.

Both unadjusted and adjusted statistics were extracted, where reported.

Where possible, all data extracted were those relevant to an intention-to-treat analysis, in which participants were analysed in groups to which they were assigned.

The time points at which outcomes were collected and reported was noted.

Data were abstracted independently by two reviewers (LP, SK) onto a data abstraction form specially designed for the review. Differences between reviewers were resolved by discussion or by appeal to a third review author (AN or AB) when necessary.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The risk of bias in the included RCT was assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool and the criteria specified in chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook 2008. This included assessment of:

sequence generation

allocation concealment

blinding (of participants, healthcare providers and outcome assessors)

- incomplete outcome data:

- ○ We recorded the proportion of participants whose outcomes were not reported at the end of the study; we noted if loss to follow-up was not reported. We coded the satisfactory level of loss to follow-up for each outcome as:

- ◇ Yes, if fewer than 20% of patients were lost to follow-up and reasons for loss to follow-up were similar in both treatment arms

- ◇ No, if more than 20% of patients were lost to follow-up or reasons for loss to follow-up differed between treatment arms

- ◇ Unclear if loss to follow-up was not reported

selective reporting of outcomes

other possible sources of bias

The risk of bias tool was applied independently by two review authors (LP, SK) and differences resolved by discussion or by appeal to a third review author (AN). Results are presented in both a risk of bias graph and a risk of bias summary.

Measures of treatment effect

We used the following measures of the effect of treatment:

For dichotomous outcomes, we used the RR.

For continuous outcomes, we used the mean difference between treatment arms.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted the trial authors of von Gruenigen 2007 to request data on the outcomes only among participants with high grade VIN who were assessed.

Data synthesis

We only identified one included trial so it was not possible to perform meta-analyses. Therefore it was not relevant to assess heterogeneity between results of trials and we were unable to assess reporting biases using funnel plots or conduct any subgroup analyses or sensitivity analyses.

RESULTS

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies.

Results of the search

The search strategy identified 2584 unique references. The abstracts of these were read independently by three review authors and articles which obviously did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded at this stage. Eight articles were retrieved in full and translated into English where appropriate and up-dated versions of relevant studies were identified. The full text screening of these eight references excluded seven of them for the reasons described in the table Characteristics of excluded studies. However, one completed RCT, was identified that met our inclusion criteria and is described in the table Characteristics of included studies. Searches of the grey literature did not identify any additional trials.

Included studies

The one included trial (von Gruenigen 2007) included women with vulvar and vaginal dysplasia, but reported the two diseases separately. Although not reported in the original paper, the trial authors provided us with outcome data for women with high grade VIN. The trial randomised 110 women, of whom 30 had high grade VIN and were assessed at the end of the trial.

This multi-centre trial recruited patients with vaginal and vulval dysplasia from 2000 to 2005.

The objective of the trial was to compare pain, adverse effects and recurrence in patients with vulval intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) or vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia (VAIN) randomised to treatment with carbon dioxide laser or ultrasonic surgical aspiration. A preoperative biopsy was performed to confirm the presence of dysplasia. Patients aged 18 years or younger and those who were pregnant were excluded from the trial. Patients were provided with informed consent before being randomly assigned to one of the treatment modalities. Patients completed a visual analogue scale to measure their level of pain and were evaluated at 2 to 4 weeks to assess scarring, wound healing and adverse effects. Patients returned every 3 months for one year for pelvic examination and cytology to assess recurrence. Follow-up colposcopy and biopsy were used at the discretion of the treating physician.

At enrolment, race, marital status, tobacco use, history of sexually transmitted infection, diethylstilbestrol exposure, immunodeficiency, hysterectomy, history of genital tract neoplasia and previous treatment were recorded.

Carbon dioxide laser surgery was performed to a depth of tissue destruction of 1 mm in non-hairy vulvar regions and 3 mm in hairy vulvar regions. Ultrasonic surgical aspiration was performed with the Cavitron Ultrasonic Surgical Aspirator Excel System (Valley- lab, Boulder, CO). The handheld tool vibrates and contains separate irrigation and suction channels. Lesions were removed to the reticular layer of the dermis. Surgeries were performed in an outpatient setting, with patients given standard discharge instructions regarding postoperative care.

The outcomes reported were recurrence after a year of follow-up, pain, scarring, dysuria, adhesions, abnormal discharge, infection and eschar. Additionally, the authors carried out multiple logistic regression to assess the relative risk of disease recurrence after 1 year follow-up in the two groups. The odds ratio was adjusted for age (continuous), history of dysplasia and smoking status.

Excluded studies

Seven references were excluded, after obtaining the full text, for the following reasons:

Four references (Bruchim 2007; Hillemanns 2005; Jones 1994; Jones 2005) were not RCTs. Bruchim 2007, Hillemanns 2005 and Jones 1994 were retrospective studies and Jones 2005 was a prospective case series.

In two references describing one trial (Ferenczy 1992; Ferenczy 1994), half the lesional area in each patient was randomised and treated with either CO2 laser surgery or loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP). However, 10/25 of the areas were treated with both LEEP and CO2 laser after relapse prior to the 9 month assessment. The trial also included women with co-existing condylomata of the vagina (n = 5) or intraepithelial neoplasia of the cervix (n = 16).

One reference (van Seters 2005) was a systematic review that yielded no further included trials.

For further details of all the excluded studies see the table Characteristics of excluded studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

The one included trial (von Gruenigen 2007) was at low risk of bias as it satisfied four criteria used to assess risk of bias (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Methodological quality summary: review authors’ judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

The trial reported the method of generation of the sequence of random numbers used to allocate women to treatment arms and made an effort to conceal this allocation sequence from patients and healthcare professionals involved in the trial. However, it was not reported whether the patients, health care professionals or outcome assessors were blinded. No woman with VIN 2 or higher was lost to follow up and it seemed unlikely that outcomes had been selectively reported as the authors provided us with data on request. It was unclear if any other bias may have been present.

Effects of interventions

Carbon dioxide laser (CO2 laser) versus ultrasonic surgical aspiration (USA)

We found only one trial (von Gruenigen 2007) which included 30 women that met our inclusion criteria and this trial reported data on CO2 laser versus USA. For dichotomous outcomes, we were unable to estimate finite confidence intervals for the RR for presence of scarring and adhesions outcomes, as women in the USA group did not experience any events.

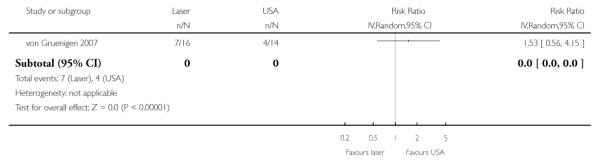

Disease recurrence after 1 year follow-up

(see Analysis 1.1)

There was no statistically significant difference in disease recurrence after 1 year follow-up between women who received CO2 laser and those who received USA (RR= 1.53, 95% CI: 0.56 to 4.15). The authors also carried out multiple logistic regression which adjusted for age (continuous), history of dysplasia and smoking status, where no statistically significant difference was observed between the two types of surgical procedures (Adjusted odds ratio= 0.68, 95% CI: 0.27 to 1.83). None of the prognostic factors appeared to be predictive of recurrence, although the trial lacked statistical power due to the small number of women in each group and the low number of observed events.

Subjective pain

(see Analysis 1.2)

There was no statistically significant difference in subjective pain between women who received CO2 laser and those who received USA (Mean Difference= −1.70, 95% CI −26.80 to 23.40).

Presence of scarring

Presence of scarring was observed in five women who received CO2 laser compared to no women who received USA (5/16 versus 0/14 in the laser and USA groups respectively).

Dysuria or burning

(see Analysis 1.3)

There was no statistically significant difference in the risk of dysuria or burning in women who received CO2 laser and those who received USA (RR= 0.66, 95% CI: 0.18 to 2.44).

Adhesions

There was no statistically significant difference in the risk of adhesions between women who received CO2 laser and those who received USA. The trial reported only one adhesions case, which was in a woman who received CO2 laser.

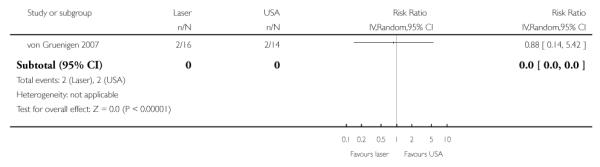

Infection (yeast, UTI, other)

(see Analysis 1.4)

There was no statistically significant difference in the risk of infection in women who received CO2 laser and those who received USA (RR= 0.88, 95% CI: 0.14 to 5.42).

Abnormal discharge

(see Analysis 1.5)

There was no statistically significant difference in the risk of abnormal discharge between women who received CO2 laser and those who received USA (RR= 1.75, 95% CI: 0.18 to 17.29).

Eschar

(see Analysis 1.6)

There was no statistically significant difference in the risk of eschar in women who received CO2 laser and those who received USA (RR= 0.88, 95% CI: 0.14 to 5.42).

DISCUSSION

Summary of main results

We found only one RCT which included 30 women that met our inclusion criteria and this trial reported data on CO2 laser versus USA. However, our primary outcomes were incompletely documented and the trial seemed to focus on adverse events. Disease recurrence was assessed in the trial, but follow-up was only one year. Long term follow up of between at least two to five years follow-up would have been more beneficial and it would have allowed other outcomes such as progression to vulvar cancer to have been investigated.

There was no statistically significant difference in the risk of disease recurrence after one year follow-up, pain, presence of scarring, dysuria or burning, adhesions, infection, abnormal discharge and eschar between women who received CO2 laser and those who received USA. There is no evidence as to whether CO2 or USA is the most effective and safe ablative surgical method for the treatment of high grade VIN and these ablative techniques have not been compared to surgical excision which is the traditional surgical modality.

There is a paucity of good quality data in this relatively rare disease. We did not expect to identify a large number of RCTs, but the review was restricted to high quality evidence as various retrospective case series are of inadequate quality and in many instances do not allow for comparison. The main limitation of this review, other than the fact the conclusions are based on small single trial analyses, is the fact that follow-up was for only one year. Many of the analyses showed the magnitude of the point estimate to be large, but due to the uncertainty, no statistically significant difference was observed. This was largely because the trial reported relatively few events and so lacked the statistical power to detect any difference in risk that might be present.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Overall, the quality of the evidence was low (GRADE Working Group), as it only included a small number of women with high grade VIN (n = 30) and outcomes were incompletely reported. We could not identify any prospective randomised trials that compared ablative with excisional techniques and/or with observation so no definitive conclusions can be drawn with respect to an optimal surgical technique for the surgical management of VIN. The single identified RCT does not address response to treatment, long term disease recurrence and progression to vulval cancer. The absence of quality of life data and sexual function data do not allow for any firm conclusions to be drawn in these respects.

Quality of the evidence

We reviewed one RCT assessing only 30 participants that evaluated two types of surgical procedures for the treatment of high grade VIN. All participants received the treatment to which they were allocated, with no loss to follow-up being reported. However, prognostic factors were only available for all stages of VIN and VAIN so it was not possible to assess whether there were any imbalances at baseline. The trial was not adequately powered to detect differences in disease recurrence or adverse events, especially as follow-up was only for one year (disease recurrence). Quality of life, response to treatment, recurrence on long term follow-up and sexual function of participants were inadequately documented. Therefore, from the included RCT, we cannot reach any definitive conclusions about the benefit of either type of surgery.

The trial was at low risk of bias. The only obvious risk of bias was from the uncertainty as to whether outcome assessors were blinded to the type of treatment that participants received. The authors did not estimate a hazard ratio which is the best statistic to summarise the difference in risk in two treatment groups over the duration of a trial, when there is “censoring” i.e. the time to disease recurrence is unknown for some women as they were still disease free at the end of the trial, but given that all patients were followed up for one year, an estimate at this time interval is probably acceptable and is unlikely to cause any major bias.

Few women experienced disease recurrence or adverse events and outcomes were incompletely reported, so there is a great need for more data to ensure higher quality evidence.

The two treatments examined in this review were both ablative methods so it was not possible to compare ablative with excisional techniques and/or with observation. Most of the available evidence is from non-randomised, non-controlled, retrospective case series with heterogenous data sets that do not allow for comparison. The main methodological limitations were:

Defination of Partcipants: In 2004, The ISSVD classification was devised that excluded VIN 1. However the above mentioned RCT and various other retrospective studies have continued with the use of the old histological classification.

Lack of standardisation in the recording of outcome measures negates comparison of observational studies.The clinical heterogeneity of VIN, uncontrolled and differing treatment modalities, short-term follow-up, and the varied health professionals involved in the management of VIN severely restrict comparison between studies.

The failure to define those patients who had previous multiple treatments with various modalities and the subsequent histological outcome to aid long term assessment of a treatment modality.

Defination of recurrence: The nature of the disease and the high risk of recurrence accentuates the difficulty in differentiating between disease persistence and disease recurrence.

Potential biases in the review process

A comprehensive search was performed, including a thorough search of the grey literature and all references were sifted and data extracted by at least two reviewers independently. We restricted the included studies to RCTs as they provide the strongest level of evidence available. Hence we have attempted to reduce bias in the review process.

The greatest threat to the validity of the review is likely to be the possibility of publication bias i.e. studies that did not find the treatment to have been effective may not have been published. We were unable to assess this possibility as the analyses were restricted to the results of a single trial.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

The exhaustive literature search confirmed only one RCT. One other systematic review was identified that included 68 studies and therefore, the outcome of 1921 patients treated with surgery for VIN (van Seters 2005). The aim of this systematic review was to assess both the risk of progression of VIN III in untreated patients and the effect of surgical treatment in relation to recurrences and progression of VIN III. After conducting a thorough search of the literature in November 2004, the authors criteria for inclusion were (1) articles written in English, German or French and (2) data, clearly retrievable, on the surgical treatment and/or progression and/or regression of VIN III. Case histories were excluded, except those concerning regression or progression of VIN III. This review included various study designs that were mainly retrospective in nature and did not include any additional RCTs.The authors reported recurrences after vulvectomy (N = 613) in 19%, after partial vulvectomy (N = 62) in 18%, after local excision (N = 808) in 22%, after laser-vaporisation (N = 253) in 23% and after cryo-coagulation (N = 16) in 56%. There was no statistically significant difference between recurrences after vulvectomy, partial vulvectomy, local excision and laser vaporisation. Recurrences were significantly lower after free surgical margins than after involved surgical margins (17% of 291 patients versus 47% of 189 patients, P < 0.001). A total of 215 invasive vulvar carcinomas (6.5%) were found. There were 107 occult carcinomas (3.2%) and 108 carcinomas (3.3%) were diagnosed during follow-up after treatment. In untreated patients the progression rate was found to be 9%.

Numerous studies have also since been published (Athavale 2008,Polterauer 2009, McFadden 2009), which contribute to available reported non-randomised, non-controlled, retrospective data apart from the one included RCT. Consequently, most of these studies were at a very high risk of bias as they were prone to selection bias or were not scientifically sound as a concurrent comparison was not available.

Both reviews suggest a decreasing age incidence of patients diagnosed with VIN probably due to increased awareness and an absolute increase in incidence (von Gruenigen 2007, van Seters 2005). Patient characteristics such as smoking and presence of multicentric disease were identified to be related to a diagnosis of VIN by some studies (von Gruenigen 2007, Athavale 2008). All authors suggest treatment was performed not only for relief of symptoms, but to remove the lesion for the purpose of cosmesis and, or to exclude or prevent progression to invasive disease. The one other systematic review and a large retrospective case note series quote the incidence of symptoms such as pain and pruritis in 60-85% of patients (van Seters 2005, Jones 2005).

The therapeutic effectiveness of loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP) compared to CO2 laser was studied (Ferenczy 1994) in 28 patients with VIN in an open trial where half the lesional area received either treatment. Treatment results are reported of the 25 patients who were compliant both with their short-term (6 to 24 weeks) and longer term (9 to 26 months, mean 12 months) follow-up schedule. At each visit, each patient received a physical and colposcopic examination, and those who recurred with disease, a biopsy was obtained to secure histologic ascertainment of disease.

A complete response was arbitrarily defined as no clinically visible disease at 9 months after the last treatment (maximum six treatment sessions). Patients with recurrent disease at 9 months or earlier were considered non-responders. Of the 25 patients who were compliant with a minimum of 9 months follow-up, a complete response at 9 months or longer was observed in 12 of 25 (48%) patients after a single laser/LEEP treatment, and seven of 13 (53%) patients who recurred after a single treatment became disease-free for 9 months or longer after two to six (mean 3) treatments with CO2 laser/LEEP. The linear extent of the lesional area in 11 of the 12 patients who responded after a single laser/LEEP was 6 cm2or less, whereas all but one patient in the multiple treatment group (mean 3) had lesions larger than 6 cm2. Most recurrences (86%) were observed at the first 6 week post-treatment visit, and the remaining 14% developed between 4 and 6 months. Recurrence rates were similar in the LEEP and CO2 laser treated areas (P = 0.5). This study reported overall complete response of 48% with recurrence rate of 52% after either a single LEEP or laser treatment. The potential advantage of LEEP over CO2 laser include the low cost and accuracy of excision of lesions versus ablation. Occult cancers are also more likely to be detected after an excisional technique for treatment rather than ablation.

This trial of Ferenczy 1994 did not randomise the patients to either treatment, but either side of the lesion was assigned to one of the two treatments by computer and the randomisation numbers appeared on each patient’s trial record. 10 of the 25 patients had both treatments prior to the 9 month follow-up assessment with many of the recurrences observed at the first 6 week follow up. It is therefore not possible to assess the benefits of either treatment in terms of recurrence. This trial was therefore excluded from the analyses.

One prospective observational study (Jones 2005) of 405 cases of VIN is unable to reliably conclude on the comparison of surgical excision versus laser ablation. This study reports that the clinical heterogeneity of VIN, uncontrolled and differing treatment modalities, short-term follow-up, and the varied physician specialties involved in the management of VIN severely restrict comparison between different treatment methods. To further illustrate this, of the 405 women in the study, one hundred ninety-four women had an initial excisional treatment, of whom 34% (95% CI: 28-41%) required further treatment, while, of the 118 women having initial laser vaporization, 39% (95% CI: 31 to 48%) required further treatment (P = 0.4). A small number of women with extensive disease (sometimes involving almost the entire vulva) were deliberately managed with 2 or more treatments, often combining excisional and laser vaporization techniques. Other treatments included 5-fluorouracil and imiquimod. Of the 198 treated unifocal lesions, 69% (95% CI: 62 to 75%) had a single treatment, while a smaller proportion of the 120 treated multifocal lesions (58%, 95% CI: 49-67%) had a single treatment (P = 0.05).

To assess the accuracy of preoperative vulva biopsy and the outcome of surgery in vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) 2 and 3 in one study, 186 consecutive patients with VIN 2 and 3 were observed (Polterauer 2009). These patients were treated with local wide excision or skinning vulvectomy. VIN 2 and 3 were correctly diagnosed by preoperative vulva biopsy in 56% (29/52) and 88% (118/134) patients, respectively. Underdiagnosis occurred in 44% (23/52) and 12% (16/134) of preoperative vulva biopsies with an occult cancer rate of 4% (2/52) and 12% (16/ 134) for VIN 2 and 3, respectively. Complete resection was achieved in 43% (80/186) of patients. Presence of multifocal VIN was the only factor that was associated with incomplete resection in the study population in univariate and multivariate analyses (P = 0.001). In another study preoperative vulval biopsies failed to exclude early stromal cancer (7%) in a series of 48 patients treated by skinning vulvectomy (Rettenmaier 1987). A recent study (Eva 2009) reviewed the histologic reports of 1309 specimens from 802 women and analysed the proportional risk of metachronous or subsequent squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva (VSCC) from pre-malignant conditions of the vulva. Five hundred eighty women had biopsy specimens containing a pre-malignant pathologic condition which was classified as either differentiated VIN (dVIN), usual VIN (uVIN), Lichen scleroses (LS) or squamous hyperplasia (SH). The results showed a significant association between the presence of dVIN and the risk of developing VSCC with an OR of 15.3 compared with an OR of 0.5 for uVIN and an OR of 0.6 for LS

The recurrent nature of the disease indicates the possible need for multiple treatments and therefore an altering effect on the cosmetic appearance of the vulva. Case studies suggest that following vulval surgery women report a reduction in sexual function and global quality of life (Andersen 1983). The psychological component is further impacted by the possibility of underlying cancer which recurs with every treatment. A study conducted by Likes 2007 examined sexual function after vulvectomy. This study of 43 women concluded that older age and a more extensive vulvar excision was associated with poorer sexual function and QoL in women following surgical treatment for VIN.

A small prospective pilot study (McFadden 2009) of eight patients found that careful observation is not a realistic option for most women with a new diagnosis of VIN 2 to 3; the majority require surgical treatment eventually. In addition, VIN appears to have an adverse impact on quality of life and sexual functioning in these women. This led to the authors abandoning plans for a randomised controlled trial of initial observation versus immediate primary surgical treatment in women with VIN.

AUTHORS’ CONCLUSIONS

Implications for practice

The included trial lacked statistical power due to the small number of women in each group and the low number of observed events. Therefore the absence of reliable evidence regarding the effectiveness and safety of the two surgical techniques for the management of vulval intraepithelial neoplasia precludes any definitive conclusions to be made.

Implications for research

Further retrospective case-series are unlikely to reveal significant new insights into VIN. Good quality prospective multi-centre randomised trials are required and there is a need to examine excisional surgical techniques and observation as well as ablative techniques. It is essential that these trials are adequately powered to allow for a satisfactory comparison of outcomes. Future trials should report long term outcomes for a recommended duration of 2-5 years to allow for assessment of treatment response, recurrence and progression to vulval cancer. Definition of disease persistence, recurrence and the participants must be standardised for the purposes of the trial. Quality of life and sexual function scores using the appropriate validated scales or tools should be considered as outcomes in women with high grade VIN receiving these surgical interventions in future trials. These outcomes are extremely important and may also contribute to the psychological well being of women with VIN.

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY.

Comparison of surgical procedures for women diagnosed with precancerous changes of the vulva (high grade vulval intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN))

Vulval intraepithelial neoplasia is regarded as a precancerous condition of the skin of the vulva that may further develop into vulval cancer. This is usually treated by surgery. The various surgical techniques are either ablative (where the lesion is removed by destruction of tissue using an energy source) or excisional (the lesion is simply ‘cut out’) and sometimes, may involve a combination of the two. There is currently no consensus on the most effective and safe surgical technique. The treatment options available to the patient are currently based on the preference of the treating physician and their skills and these vary both nationally and internationally. Due to the inherent nature of the disease to present itself repeatedly in spite of multiple treatments, various conservative surgical and medical modalities of treatment are currently being explored.

This review is based on one randomised controlled trial (RCT) of 30 patients and therefore the results are restricted to the analyses of a single study. This RCT compared two ablative techniques, the use of the carbon dioxide laser (CO2 laser) with ultrasonic surgical aspiration (USA). There was no evidence of a difference in the risk of disease recurrence after one year follow-up, pain, presence of scarring, painful/uncomfortable urination (dysuria) or burning, adhesions, infection, abnormal discharge and the presence of dead tissue shedding from healthy skin (eschar) between women who received CO2 laser and those who received USA. Due to the small number of patients with high grade VIN in the trial there was insufficient evidence to conclude that either surgical technique is superior over the other. This review highlights the need for future high quality, well designed trials.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Chris Williams for clinical and editorial advice, Jane Hayes for designing the search strategy and Gail Quinn and Clare Jess for their contribution to the editorial process. We thank the referees for their helpful comments and Dr Heidi Frasure and her clinical colleagues in Ohio for providing us with important data on women with high grade VIN. We would like to acknowledge assistance from Miss Amanda Tristam, Senior lecturer gynaecological oncology, Cardiff University and Mr Raj Naik, Consultanat Gynaecological Oncologist, Queen Elizabeth Hospital Gateshead, as experts contacted for information on ongoing trials.

SOURCES OF SUPPORT

Internal sources

No sources of support supplied

External sources

Department of Health, UK.

NHS Cochrane Collaboration programme Grant Scheme CPG-506

Appendix 1. MEDLINE search strategy

Ovid Medline 1950 to September week 1 2010

(VIN or VIN2 or VIN3).mp.

(vulva* adj5 intraepithelial neoplasia).mp.

1 or 2

exp Vulva/

vulva*.mp.

4 or 5

exp Precancerous Conditions/

(pre-cancer* or precancer*).mp.

dysplasia.mp.

unifocal.mp.

multifocal.mp.

exp Carcinoma in Situ/

carcinoma in situ.mp.

7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13

6 and 14

3 or 15

key: mp=title, original title, abstract, name of substance word, subject heading word

Appendix 2. EMBASE search strategy

Embase Ovid 1980 to 2010 week 36

(VIN or VIN2 or VIN3).mp.

(vulva* adj5 intraepithelial neoplasia).mp.

1 or 2

exp Vulva/

vulva*.mp.

4 or 5

exp Precancer/

(pre-cancer* or precancer*).mp.

dysplasia.mp.

unifocal.mp.

multifocal.mp.

exp Carcinoma in Situ/

carcinoma in situ.mp.

8 or 11 or 7 or 13 or 10 or 9 or 12

6 and 14

3 or 15

key: mp=title, abstract, subject headings, heading word, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer name

Appendix 3. CENTRAL search strategy

CENTRAL Issue 3, 2010

(VIN or VIN2 or VIN3):ti,ab,kw

(vulva* near/5 intraepithelial neoplasia):ti,ab,kw

(#1 OR #2)

MeSH descriptor Vulva explode all trees

vulva*

(#4 OR #5)

MeSH descriptor Precancerous Conditions explode all trees

pre-cancer* or precancer*

dysplasia

unifocal

multifocal

MeSH descriptor Carcinoma in Situ explode all trees

carcinoma in situ

(#7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13)

(#6 AND #14)

(#3 OR #15)

key: ti,ab,kw = title, abstract, keyword

CHARACTERISTICS OF STUDIES

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | Multi-centre RCT Age (50 years or younger and older than 50 years) and site location were used as stratification variables in the randomisation assignment |

|

| Participants | 30 women with high grade VIN out of a total of 110 which included VIN 1 and all grade VAIN. 16 of the 30 women with high grade VIN were randomised to carbon dioxide laser (laser) and 14 women to ultrasonic surgical aspiration (USA) | |

| Interventions |

Interventions: Carbon dioxide laser surgery: Depth of tissue destruction was 1 mm in non-hairy vulvar regions and 3 mm in hairy vulvar regions Ultrasonic surgical aspiration: Surgery was performed with the Cavitron Ultrasonic Surgical Aspirator Excel System (Valley- lab, Boulder, CO). The handheld tool vibrates and contains separate irrigation and suction channels. Lesions were removed to the reticular layer of the dermis Surgeries were performed in an outpatient setting, with patients given standard discharge instructions regarding postoperative care. The use of topical postoperative symptom control therapies (for example, silver sulfadiazine) were ordered at the discretion of the attending physician All patients were seen preoperatively and treated by one of three gynaecologic oncologists |

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes | Patients were followed up quarterly for a year. Fifty-three percent of patients treated in this study had received prior therapy for intraepithelial disease |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Yes | “Blocked randomization was carried out by a computer-generated table of random numbers corresponding to treatment assignment” |

| Allocation concealment? | Yes | “Randomization assignment was given to the treating physician by personnel not involved in the patient’s medical care” |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Unclear | Not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Yes | % analysed: 30/30 (100%) |

| Free of selective reporting? | Yes | It seems unlikely that outcomes were selectively reported as trial authors provided us with data for VIN 2 or higher grade women on request |

| Free of other bias? | Unclear | Insufficient information to assess whether an additional risk of bias exists |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Bruchim 2007 | This study was a retrospective, non-randomised, non-controlled, case-series evaluation |

| Ferenczy 1992 | Abstract that was later published in full in 1994 and is one of the excluded studies in the review (Ferenczy 1994) |

| Ferenczy 1994 | This study was an RCT. Each patient had half the lesional area treated with CO2 laser excision/vaporisation and the other half was electro-excised/fulgurated. However, 10 of the areas were treated both LEEP and CO2 laser after relapse prior to the 9 month assessment. Consequently this primary objective could not be assessed by treatment arm. The trial also included women with co-existing condylomata of the vagina (n=5) or intraepithelial neoplasia of the cervix (n=16) |

| Hillemanns 2005 | This study is a retrospective case note analysis of 93 cases, 8 of which were VIN1. The treatment methods were subject to selection bias and were based on surgeon choice. Treatment failure, persistence of VIN and recurrence are not well defined secondary to a retrospective analysis |

| Jones 1994 | This study is a retrospective case note analysis to assess the outcome of untreated VIN with relation to the development of cancer |

| Jones 2005 | Prospective case series review of 405 cases. |

| van Seters 2005 | This systematic review of surgical interventions for women with VIN III yielded no further included RCTs |

DATA AND ANALYSES

Comparison 1.

Carbon dioxide laser versus ultrasonic surgical aspiration

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Disease recurrence after 1 year follow-up | 1 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2 Subjective pain | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3 Dysuria or burning | 1 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4 Infection (yeast, UTI, other) | 1 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 5 Abnormal discharge | 1 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 6 Eschar | 1 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only |

Analysis 1.1. Comparison 1 Carbon dioxide laser versus ultrasonic surgical aspiration, Outcome 1 Disease recurrence after 1 year follow-up

Review: Surgical interventions for high grade vulval intraepithelial neoplasia

Comparison: 1 Carbon dioxide laser versus ultrasonic surgical aspiration

Outcome: 1 Disease recurrence after 1 year follow-up

|

Analysis 1.2. Comparison 1 Carbon dioxide laser versus ultrasonic surgical aspiration, Outcome 2 Subjective pain

Review: Surgical interventions for high grade vulval intraepithelial neoplasia

Comparison: 1 Carbon dioxide laser versus ultrasonic surgical aspiration

Outcome: 2 Subjective pain

|

Analysis 1.3. Comparison 1 Carbon dioxide laser versus ultrasonic surgical aspiration, Outcome 3 Dysuria or burning

Review: Surgical interventions for high grade vulval intraepithelial neoplasia

Comparison: 1 Carbon dioxide laser versus ultrasonic surgical aspiration

Outcome: 3 Dysuria or burning

|

Analysis 1.4. Comparison 1 Carbon dioxide laser versus ultrasonic surgical aspiration, Outcome 4 Infection (yeast, UTI, other)

Review: Surgical interventions for high grade vulval intraepithelial neoplasia

Comparison: 1 Carbon dioxide laser versus ultrasonic surgical aspiration

Outcome: 4 Infection (yeast, UTI, other)

|

Analysis 1.5. Comparison 1 Carbon dioxide laser versus ultrasonic surgical aspiration, Outcome 5 Abnormal discharge

Review: Surgical interventions for high grade vulval intraepithelial neoplasia

Comparison: 1 Carbon dioxide laser versus ultrasonic surgical aspiration

Outcome: 5 Abnormal discharge

|

Analysis 1.6. Comparison 1 Carbon dioxide laser versus ultrasonic surgical aspiration, Outcome 6 Eschar

Review: Surgical interventions for high grade vulval intraepithelial neoplasia

Comparison: 1 Carbon dioxide laser versus ultrasonic surgical aspiration

Outcome: 6 Eschar

|

HISTORY

Protocol first published: Issue 3, 2009

Review first published: Issue 1, 2011

DIFFERENCES BETWEEN PROTOCOL AND REVIEW

Restriction to RCTs

The search strategy identified one RCT that met our inclusion criteria, so we restricted the review to RCTs as they provide the best level of evidence. We were also concerned about the threat of selection bias in non-randomised studies. In the protocol we had stated the following:

Since we expect to find few RCTs of surgical interventions (Johnson 2008), the following types of non-randomised studies with concurrent comparison groups will be included:

Quasi-randomised trials, non-randomised trials, prospective and retrospective cohort studies, and case series of 30 or more patients.

Case-control studies and case series of fewer than 30 patients will be excluded.

Searches

In the protocol, we stated:

“The main investigators of any relevant ongoing trials will be contacted for further information, as will any major co-operative trials groups active in this area.”

However, we did not find any relevant ongoing trials or active trials groups, so we did not make these contacts.

Risk of bias

Risk of bias was not examined in non-randomised studies as the review was restricted to RCTs. In the protocol we stated the following:

The risk of bias in non-randomised studies will be assessed in accordance with four additional criteria:

Cohort selection

- Were relevant details of criteria for assignment of patients to treatments provided?

- Yes

- No

- Unclear

- Was the group of women who received the experimental intervention representative?

- Yes, if representative of women with high grade VIN

- No, if group of patients was selected

- Unclear, if selection of group was not described

- Was the group of women who received the comparison intervention representative?

- Yes, if drawn from the same population as the intervention group

- No, if drawn from a different source

- Unclear, if selection of group not described

Comparability of treatment groups

- Were there no differences between the two groups or were differences controlled for, in particular with reference to age, ethnicity, smoking status, immunocompromised status, size of lesion, type of surgeon (gynaecological oncologist or general gynaecologist)

- Yes, if at least two of these characteristics were reported and any reported differences were controlled for

- No, if the two groups differed and differences were not controlled for.

- Unclear, if fewer than two of these characteristics were reported even if there were no other differences between the groups, and other characteristics had been controlled for.

Time to event outcome data

Time to event outcome data were not reported in the trial of von Gruenigen 2007 so the following sections in the protocol which discussed the handling of data for survival outcomes were removed as they were unnecessary:

“Data extraction and management

For time to event (disease recurrence and progression to vulvar cancer) data, we will extract the log of the hazard ratio [log(HR)] and its standard error from trial reports; if these are not reported, we will attempt to estimate them from other reported statistics using the methods of Parmar 1998.

Measures of treatment effect

For time to event data, we will use the HR, if possible. The HR summarises the chances of survival in women who received one type of treatment compared to the chances of survival in women who received another type of treatment. However, the logarithm of the HR, rather than the HR itself, is generally used in meta-analyses”.

Data synthesis

We only identified one included trial so it was not possible to perform meta-analyses. Therefore it was not relevant to assess heterogeneity between results of trials and we were unable to assess reporting biases using funnel plots or conduct any subgroup analyses or sensitivity analyses. The following sections of the protocol were therefore removed:

“Assessment of heterogeneity

Heterogeneity between studies will be assessed by visual inspection of forest plots, by estimation of the percentage heterogeneity between trials which cannot be ascribed to sampling variation (Higgins 2003), by a formal statistical test of the significance of the heterogeneity (Deeks 2001) and, where possible, by sub-group analyses (see below). If there was evidence of substantial heterogeneity, the possible reasons for this were investigated and reported.

Assessment of reporting biases

Funnel plots corresponding to meta-analysis of the primary outcome will be examined to assess the potential for small study effects such as publication bias. If these plots suggest that treatment effects may not be sampled from a symmetric distribution, as assumed by the random effects model, further meta-analyses will be performed using fixed effects models.

Data synthesis

If sufficient, clinically similar studies are available, their results will be pooled in meta-analyses. Adjusted summary statistics will be used if available; otherwise unadjusted results will be used.

For time-to-event data, HRs will be pooled using the generic inverse variance facility of RevMan 5.

For any dichotomous outcomes, the RR will be calculated for each study and these will then be pooled.

For continuous outcomes, the mean differences between the treatment arms at the end of follow-up will be pooled if all trials measured the outcome on the same scale, otherwise standardised mean differences will be pooled.

If any trials have multiple intervention groups, the control group will be divided between the intervention groups - to prevent double counting of participants in the meta-analysis - and comparisons between each intervention and a split control group will be treated independently. This is .

Random effects models with inverse variance weighting will be used for all meta-analyses (DerSimonian 1986).

If sufficient data are available, indirect comparisons, using the methods of Bucher 1997 will be used to compare competing interventions that have not been compared directly with each other.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Sub-group analyses will be performed, grouping the trials by multifocal and unifocal lesions as their treatment modalities may differ. Factors such as age, VIN stage, type of intervention and length of follow-up will be considered in interpretation of any heterogeneity.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses will be performed excluding non-randomised studies if RCTs have been included (ii) excluding studies at high risk of bias and (iii) using unadjusted results.

Footnotes

DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST None known.

References to studies included in this review

- von Gruenigen 2007 {published data only} .von Gruenigen VE, Gibbons HE, Gibbins K, Jenison EL, Hopkins MP. Surgical treatments for vulvar and vaginal dysplasia: a randomized controlled trial. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2007;Vol. 109(issue 4):942–7. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000258783.49564.5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

- Bruchim 2007 {published data only} .Bruchim I, Gotlieb WH, Mahmud S, Tunitsky E, Grzywacz K, Ferenczy A. HPV-related vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia: outcome of different management modalities. International Journal of Gynaecology & Obstetrics. 2007;99(1):23–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferenczy 1992 {published data only} .Ferenczy A. Comparison of CO2 laser ablation and loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP) for the treatment of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) Gynecologic Oncology. 1992;Vol. 45(issue 1):82. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1438.1994.04010022.x. Abstract 25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferenczy 1994 {published data only} .Ferenczy A, Wright TC, Jnr, Richart RM. Comparison of CO2 laser surgery and loop electrosurgical/fulguration procedure (LEEP) for the treatment of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) International Journal of Gynecological Cancer. 1994;Vol. 4(issue 1):22–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1438.1994.04010022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillemanns 2005 {published data only} .Hillemanns P, Wang X, Staehle S, Michels W, Dannecker C. Evaluation of different treatment modalities for vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN): CO(2) laser vaporization, photodynamic therapy, excision and vulvectomy. Gynecologic Oncology. 2005;100(2):271–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones 1994 {published data only} .Jones RW, Rowan DM. Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia III: a clinical study of the outcome in 113 cases with relation to the later development of invasive vulvar carcinoma. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 1994;84(5):741–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones 2005 {published data only} .Jones RW, Rowan DM, Stewart AW. Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia: aspects of the natural history and outcome in 405 women. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2005;106(6):1319–26. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000187301.76283.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Seters 2005 {published data only} .van Seters M, van Beurden M, de Craen AJ. Is the assumed natural history of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia III based on enough evidence? A systematic review of 3322 published patients.[see comment]. [Review] [112 refs] Gynecologic Oncology. 2005;97(2):645–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

- Andersen 1983 .Andersen B, Hacker N. Psychosexual adjustment after vulvar surgery. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1983;62(4):457–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Athavale 2008 .Athavale R, Naik R, Godfrey KA, Cross P, Hatem MH, de Barros Lopes A. Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia--the need for auditable measures of management. European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology. 2008;137(1):97–102. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucher 1997 .Bucher HC, Guyatt GH, Griffith LE, Walter SD. The results of direct and indirect treatment comparisons in meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1997;50(6):683–91. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00049-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane Handbook 2008 .Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. issue Version 5.0.1. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2008. www.cochrane–handbook.org [Google Scholar]

- CTCAE 2006 .CTCAE . Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events. Vol. v3.0. CTCAE; [9th August 2006]. http://ctep.cancer.gov/forms/CTCAEv3.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Deeks 2001 .Deeks JJ, Altman DG, Bradburn MJ. Statistical methods for examining heterogeneity and combining results from several studies in meta-analysis. In: Egger M, Davey Smith G, Altman DG, editors. Systematic Reviews in Health Care: Meta-Analysis in Context. 2nd edition BMJ Publication Group; London: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- DerSimonian 1986 .DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Controlled Clinical Trials. 1986;7:177–88. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eva 2009 .Eva LJ, Ganesan R, Chan KK, Honest H, Luesley DM. Differentiated-type vulval intraepithelial neoplasia has a high-risk association with vulval squamous cell carcinoma. International Journal of Gynaecological Cancer. 2009;19(4):741–4. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181a12fa2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrat 1995 .Garrat AM, Torgerson DJ, Wyness J, Hall MH, Reid DM. Measuring sexual function in premenopausal women. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1995;102:311–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1995.tb09138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRADE Working Group .GRADE Working Group Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2004;328:1490–94. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7454.1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins 2003 .Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillemanns 2000 .Hillemanns P, Untch M, Dannecker C. Photodynamic therapy of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia using 5-aminolevulinic acid. International Journal of cCancer. 2000;85(5):649–53. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(20000301)85:5<649::aid-ijc9>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IARC 2002 .Parkin DM, Whelan SL, Ferlay J, Teppo L, Thomas DB. IARC Scientific Publication No. 155. Vol. Volume VIII. IARC; Lyon: 2002. Cancer Incidence in Five Continents. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson 2008 .Johnson NP, Selman T, Zamora J, Khan KS. Gynaecologic surgery from uncertainty to science: evidence-based surgery is no passing fad. Human Reproduction. 2008;23(4):832–9. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones 1997 .Jones RW, Baranyai J, Stables S. Trends in squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva: the influence of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1997;90(3):448–52. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(97)00298-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones 2001 .Jones RW. Vulval intraepithelial neoplasia: current perspectives. European Journal of Gynaecological Oncology. 2001;22(6):393–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joura 2000 .Joura EA. Trends in vulvar neoplasia. Increasing incidence of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia and squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva in young women. Journal of Reproductive Medicine. 2000;45(8):613–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le 2007 .Le T, Menard C, Hicks-Boucher W. Final results of a phase 2 study using continuous 5% Imiquimod cream application in the primary treatment of high-grade vulva intraepithelial neoplasia. Gynecological Oncology. 2007;106:579–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Likes 2007 .Likes WM, Stegbauer C, Tillmanns T, Pruett J. Pilot study of sexual function and quality of life after excision for vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. Journal of Reproductive Medicine. 2007;52(1):23–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathiesen 2007 .Mathiesen O, Buus SK, Cramers M. Topical imiquimod can reverse vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia: A randomised double-blinded study. Gynecological Oncology. 2007;102:219–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFadden 2009 .McFadden KM, Sharp L, Cruickshank ME. The prospective management of women with newly diagnosed vulval intraepithelial neoplasia: Clinical outcome and quality of life. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2009 Nov;29(8):749–53. doi: 10.3109/01443610903191285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naransingh 2000 .Narayansingh GV, Cumming GP, Parkin DP, McConell DT, Honey E, Kolhe PS. Flap Repair: an effective strategy for minimising sexual morbidity associated with the surgical management of vulval intraepithelial neoplasia. Journal of the Royal College of Surgeons Edinburgh. 2000;45(2):81–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ONS 2004 .Office for National Statistics Cancer Registrations in England. 2004 http://www.statistics.gov.uk/statbase/Product.asp?vlnk=8843

- Parmar 1998 .Parmar MK, Torri V, Stewart L. Extracting summary statistics to perform meta-analyses of the published literature for survival endpoints. Statistics in Medicine. 1998;17(24):2815–34. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19981230)17:24<2815::aid-sim110>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polterauer 2009 .Polterauer S, Catharina Dressler A, Grimm C, Seebacher V, Tempfer C, Reinthaller A, et al. Accuracy of preoperative vulva biopsy and the outcome of surgery in vulvarintraepithelial neoplasia 2 and 3. International Journal of Gynecological Pathology. 2009 Nov;28(6):559–62. doi: 10.1097/PGP.0b013e3181a934d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rettenmaier 1987 .Rettenmaier MA, Berman ML, DiSaia PJ. Skinning vulvectomy for the treatment of multifocal vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1987;69(2):247–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tristam 2005 .Tristam A, Fiander A. Clinical responses to cidofir applied topically to women with high grade vulval intraepithelial neoplasia. Gynaecological Oncology. 2005;99(3):652–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.07.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van derAvoort 2006 .van derAvoort I, Shirango H, Hoevenaars BM. Vulval squamous cell carcinoma is a multifactorial disease following two separate and independent pathways. International Journal of Gynecological Pathology. 2006;25(1):22–9. doi: 10.1097/01.pgp.0000177646.38266.6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Seters 2002 .van Seters M, Fons G, van Buerden M. Imiquimod in the treatment of multifocal vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia 2/ 3. Results of a pilot study. Journal of Reproductive Medicine. 2002;47(9):701–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WCISU 2004 .Welsh Cancer Intelligence and Surveillance Unit Cancer Registrations in Wales. 2000–2004 http://www.wales.nhs.uk/sites3/page.cfm?orgid=242&pid=18135

- * Indicates the major publication for the study