Abstract

Background

Vulval intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) is a pre-malignant condition of the vulval skin; its incidence is increasing in women under 50 years. VIN is graded histologically as low grade or high grade. High grade VIN is associated with infection with human papilloma virus (HPV) infection and may progress to invasive disease. There is no consensus on the optimal management of high grade VIN. The high morbidity and high relapse rate associated with surgical interventions call for a formal appraisal of the evidence available for less invasive but effective interventions for high grade VIN.

Objectives

To evaluate the effectiveness and safety of medical interventions for high grade VIN.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Gynaecological Cancer Group Trials Register, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library 2010, Issue 3), MEDLINE and EMBASE (up to September 2010). We also searched registers of clinical trials, abstracts of scientific meetings, reference lists of included studies and contacted experts in the field.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that assessed medical interventions, in adult women diagnosed with high grade VIN.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently abstracted data and assessed risk of bias. Where possible the data were synthesised in a meta-analysis.

Main results

Four trials met our inclusion criteria: three assessed the effectiveness of topical imiquimod versus placebo in women with high grade VIN; one examined low versus high dose indole-3-carbinol in similar women.

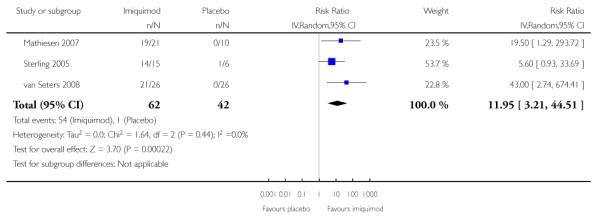

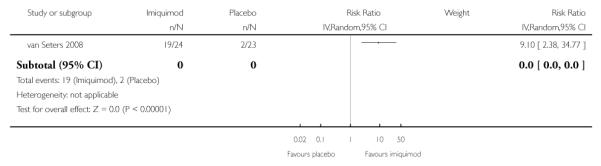

Meta-analysis of three trials found that the proportion of women who responded to treatment at 5 to 6 months was much higher in the group who received topical imiquimod than in the group who received placebo (relative risk (RR) = 11.95, 95% confidence interval (CI) 3.21 to 44.51). A single trial showed similar results at 12 months in (RR = 9.10, 95% CI 2.38 to 34.77). Only one trial reported adverse events, which were more common in the imiquimod group. One trial found no significant differences in quality of life (QoL) or body image between the imiquimod and placebo groups.

Authors’ conclusions

Imiquimod appears to be effective, but its safety needs further examination. Its use is associated with side effects which are tolerable, but more extensive data on adverse effects are required. Long term follow-up should be mandatory in view of the known progression of high grade VIN to invasive disease. Alternative medical interventions, such as cidofovir, should be explored.

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH): Administration, Topical; Aminoquinolines [*administration & dosage; adverse effects]; Anticarcinogenic Agents [administration & dosage]; Antineoplastic Agents [*administration & dosage; adverse effects]; Carcinoma in Situ [pathology; *therapy]; Indoles [*administration & dosage]; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Vulvar Neoplasms [pathology; *therapy]

MeSH check words: Adult, Female, Humans

BACKGROUND

Description of the condition

Vulval intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) is a condition in which pre-cancerous changes occur in the skin that covers the vulva of the female external genital organs. VIN can affect women at any age but most recent studies suggest it is more common under the age of 50 (Jones 2005). VIN is diagnosed by histological examination of a vulval biopsy and can be classified histologically as either low grade (VIN 1) or high grade (VIN 2/3) depending on the thickness of affected squamous cells. In 2004, the Vulvar Oncology Subcommittee of the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease modified this classification to reflect the two divergent types of VIN. The human papilloma virus (HPV) related type, which precedes almost all vulval cancers in women under 45 is described as usual type VIN, and the lichen sclerosus-related type, which precedes vulval cancer in older women and is known as the differentiated type VIN (Sideri 2005). Patients who smoke or are immunocompromised are more likely to have VIN (Jones 2005). VIN may be asymptomatic or present with a variety of symptoms such as itching, discomfort, burning of the vulva or dyspareunia. Clinical examination may reveal red, brown, or white vulval lesions which can be flat or condylomatous in appearance. These symptoms can lead to considerable morbidity. The additional concern with VIN, however, is the proven progression to invasive cancer of the vulva. The true rate of progression to invasive vulval cancer in women with untreated high-grade VIN is not clear, with reported rates ranging from 9% (Van Seters 2005) to 18.5% (Jones 2005). The risk of progression in spite of treatment has been reported as between 2 to 5% (Jones 2005) and 3.3 (Van Seters 2005). A woman’s risk of developing cancer of the vulva by the age of 75 varies between countries, ranging from 0.01% to 0.28%, which corresponds to 0 to 3 cases per year in 100,000 women under 75 years (IARC 2002). More recently an increase in vulval cancer in women under the age of 50 has been documented (Joura 2000; Jones 1997; ONS 2004; WCISU 2004). This rising trend has been linked to an increasing incidence of VIN in younger women which has been attributed to infection with oncogenic human papilloma virus (HPV) 16/18 infection (de Vuyst 2009).

Description of the intervention

The treatment of VIN depends on the grade and location of the lesion on the vulva. Once diagnosed, VIN is monitored with close inspection of the vulva and surrounding perianal region. Liberal biopsying of any suspicious areas is advocated to ascertain progression to invasive disease. High grade VIN lesions are considered to have a high propensity for malignant conversion, so historically they were managed actively by surgical excision (Kauffman 1995) or ablative techniques, such as laser treatment. Surgery involves a wide local excision for focal lesions or a simple vulvectomy, if the lesions are multifocal. Due to the high recurrence rate, the disfiguring nature of these procedures and the negative psychosexual impact on patients (Andreasson 1986), less invasive medical interventions have been developed and are still being evaluated. Agents utilised prior to the 1990s have largely been disregarded due to either their inefficacy or their unacceptable side effect profile. Medical chemotherapeutic interventions assessed in the 1980s included 5-fluorouracil (Sillman 1985), bleomycine (Roberts 1980) and trinitrochlorobenzene (Foster 1981). However, these chemother apeutic agents had intolerable side effects and are no longer used. α-IFN, was also investigated in the 1980s and early 1990s with initial promising results (Spirtos 1990). However, its high cost and side effects have also limited its use. Photodynamic therapy was evaluated in the late 1990s with varying results (Dougherty 1998; Hillemanns 2000; Fehr 2001). More recently imiquimod, an immune response modifier which was initially approved and used to treat genital warts (Moore 2001), has been investigated for the treatment of VIN (van Seters 2002). Imiquimod, either alone or in conjunction with photodynamic therapy, has been subjected to randomised controlled trials with promising results (Le 2007;Mathiesen 2007; Winters 2008; van Seters 2008). Cidofovir, a potent antiviral agent, has also been considered for treating high grade VIN. However, there are very few studies evaluating its efficacy (Tristram 2005). The phytochemical indole-3-carbinol (I3C) is a natural substance, derived from the breakdown of glucosinolates, and is present in large concentrations in cruciferous vegetables (cabbage, broccoli, brussel sprouts, and cauliflower). I3C has been shown to be effective in treating high grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) (Bell 2000) and high grade VIN (Naik 2006).

How the intervention might work

Medical interventions for high grade VIN are aimed at either directly destroying affected cells or indirectly enhancing the body’s immune response, with resulting increased destruction of cells infected with HPV. Immune modulators such as imiquimod, enhance immune response in a number of ways. The result is inhibition of viral replication of HPV in vulval squamous cells and enhancement of cell-mediated immunity targeted a destroying affected cells (Stanley 2002). VIN has been directly associated with HPV infection, which has been shown to increase 16-alpha-hydroxylation of oestradiol, thereby increasing the amount of 16-alpha-hydroxyestrone which is known to be carcinogenic (Newfield 1998). Dietary I3C acts as a potent inducer of 2-hydroxylation of oestradiol in rodents and humans, and increases production of the anti-proliferative metabolite 2-hydroxyestrone whilst decreasing production of the potentially carcinogenic metabolite 16-alpha-hydroxyestrone, which known to be associated with high grade VIN. Cidofovir is a deoxycytidine monophosphate analogue, which has potent antiviral activity against a broad range of DNA viruses, including HPV which is known to be associated with VIN. Cidofovir probably mediates its effects by causing death in HPV-infected cells within the affected vulval area. The use of cidofovir has been approved for treatment of other viral infections, but there are only a few studies demonstrating its efficacy in treating VIN (Tristram 2005).

A recent phase II trial has used sequential treatment with imiquimod and photodynamic therapy with promising results (Winters 2008). Photodynamic therapy is not considered a medical intervention. It causes direct destruction of VIN lesions using the interaction between a tumour-localising photo-sensitiser and light of an appropriate wavelength to bring about molecular oxygen-induced cell death. It is occasionally used in conjunction with a topical agent called 5-aminolaevulinic acid (ALA), since the resultant chemical reaction reduces incidental damage to surrounding normal tissues (Dougherty 1998).

Why it is important to do this review

Currently there is no consensus on the optimal and acceptable medical management of high grade VIN. Surgical and ablative intervention only removes visible lesions and has significant psychosexual implications. The need for a clinically proven, safe and tolerable medical intervention to avoid surgical interventions has never been more apparent. VIN and vulval cancer are being diagnosed in younger women where traditionally surgical treatment was indicated. The high morbidity and high relapse rate associated with surgical intervention (Kuppers 1997) calls for a formal appraisal of the evidence available for alternative less invasive but effective interventions for high grade VIN.

OBJECTIVES

To evaluate the effectiveness and safety of medical interventions for high grade VIN.

METHODS

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs).

Types of participants

Women aged over 18 years with a confirmed histological diagnosis of high-grade VIN (VIN 2 or VIN 3). Women with either unifocal or multifocal disease of the vulva were included; those with a histological diagnosis of Paget’s were excluded. Trials that studied the management of vulval carcinoma were excluded.

Types of interventions

Medical agents used to treat high grade VIN. These could be topically (cream or ointment) or orally administered. Trials either comparing a single agent to placebo or a varying dose of a single agent.

immune modulators

food additive

any other medical intervention, excluding those targeted exclusively at symptomatic control

Control:

placebo

We considered direct comparisons of different types of interventions and also comparisons of interventions and control.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Response to treatment (based on clinical and histological evidence of resolution, regression, persistence or progression of high grade VIN).

Recurrence of VIN at long term follow

Progression to vulval cancer

Secondary outcomes

Pain due to disease

Pruritis due to disease

Superficial dyspareunia

Quality of life (QoL), as measured by a validated scale

Sexual Function using validated tool. (e.g. Sabbatsberg sexual self rating scoring; Garrat 1995; Naransingh 2000)

- Adverse events of local treatment classified according toCTCAE 2006, including:

- skin reactions (erythema, excoriation, pruritus, erosion, papular rash)

- severe skin reactions (hypopigmentation, hyperpigmentation, crusting, erosions, indurations, urticaria)

- oedema and discharge

- pain and tenderness

- bleeding

Search methods for identification of studies

Papers in all languages were sought and translations carried out when necessary.

Electronic searches

See: Cochrane Gynaecological Cancer Group methods used in reviews.

The following electronic databases were searched:

The Cochrane Gynaecological Cancer Collaborative Review Group’s Trial Register

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), (The Cochrane Library 2010, Issue 3)

MEDLINE up to September 2010

EMBASE up to September 2010

The, Embase and Central search strategies aiming to identify RCTs comparing medical interventions of high grade VIN before September 2010 are presented in Appendix 1, Appendix 2 and Appendix 3 respectively.

Databases were searched from January 1950 until September 2010.

All relevant articles found were identified on PubMed and using the ’related articles’ feature, a further search was carried out for newly published articles.

Searching other resources

Unpublished and Grey literature

Metaregister, Physicians Data Query, www.controlled-trials.com/rct, www.clinicaltrials.gov and www.cancer.gov/clinicaltrials were searched for ongoing trials. The main investigators of the one relevant ongoing trial RT3VIN (RT3VIN Clinical Trial) were contacted for further information and they have informed us that the expected completion date of this trial is September 2011.

Hand-searching

Reports of conferences were handsearched in the following sources:

Gynecologic Oncology (Annual Meeting of the American Society of Gynecologic Oncologist).

International Journal of Gynecological Cancer (Annual Meeting of the International Gynecologic Cancer Society).

British Journal of Cancer.

British Cancer Research Meeting.

Annual Meeting of European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO).

Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

Reference lists and Correspondence

We checked for any relevant registered ongoing trials and contacted the authors accordingly. RT3VIN Clinical Trial was the only identified ongoing trial. We contacted the authors of the Sterling 2005 trial to obtain more information about the trial. The authors of the van Seters 2008 trial also provided additional information as did various experts in the field who reviewed the manuscript prior to publication.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

All titles and abstracts retrieved by electronic searching were downloaded to the reference management database Endnote. Duplicates were removed and the remaining references examined by two review authors (LP, SK) independently. Those references which did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded and copies of the full text of potentially relevant references were obtained. The eligibility of retrieved papers was assessed independently by two reviewers (LP, SK). Disagreements were resolved by discussion between the two review authors and when necessary by a third review author (AB). Reasons for exclusion were documented.

Data extraction and management

For included studies, data were abstracted as recommended in chapter 7 of the Cochrane Handbook 2008. This included data on the following:

Author, year of publication and journal citation (including language)

Country

Setting

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Study design, methodology

- Study population

- ○ Total number enrolled

- ○ Patient characteristics

- ○ Age

- ○ co-morbidities

- ○ Previous treatment

- VIN details

- ○ unifocal or multifocal lesion

- ○ grade

- ○ size of lesion

- Local immune modulator intervention details

- ○ Dose

- ○ Duration

and/or

- Details of dose and duration of any other therapy used

- ○ Type of therapy

- ○ Dose (if appropriate)

- ○ Duration (if appropriate)

Risk of bias in study (see below)

Duration of follow-up

- Outcomes - Response of treatment, recurrence on long term follow up, progression to vulval cancer, symptom assessment, QoL, pain, itching, soreness, superficial dyspareunia and adverse events.

- ○ For each outcome: Outcome definition (with diagnostic criteria if relevant);

- ○ Unit of measurement (if relevant);

- ○ For scales: upper and lower limits, and whether high or low score is good

- ○ Results: Number of participants allocated to each intervention group;

- ○ For each outcome of interest: Sample size; Missing participants.

Data on outcomes were extracted as below:

For dichotomous outcomes (e.g. adverse events, response to treatment, pain due to disease, pruritis due to disease), we extracted the number of patients in each treatment arm who experienced the outcome of interest and the number of patients assessed at endpoint, in order to estimate a risk ratio (RR).

Where possible, all data extracted were relevant to an intention-to-treat analysis, in which participants were analysed in groups to which they were assigned.

The time points at which outcomes were collected and reported was noted.

Data were abstracted independently by two review authors (LP, SK) onto a data abstraction form specially designed for the review. Differences between review authors were resolved by discussion or by appeal to a third review author (AB) when necessary.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The risk of bias in included RCTs was assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool and the criteria specified in chapter 8 of theCochrane Handbook 2008. This included assessment of:

sequence generation

allocation concealment

blinding (of participants, healthcare providers and outcome assessors)

- incomplete outcome data:

- ○ We recorded the proportion of participants whose outcomes were not reported at the end of the trial; we noted if loss to follow-up was not reported. We coded the satisfactory level of loss to follow-up for each outcome as:

- ◇ Yes, if fewer than 20% of patients were lost to follow-up and reasons for loss to follow-up were similar in both treatment arms

- ◇ No, if more than 20% of patients were lost to follow-up or reasons for loss to follow-up differed between treatment arms

- ◇ Unclear if loss to follow-up was not reported

selective reporting of outcomes

other possible sources of bias

The risk of bias tool as applied independently by two review authors (LP, SK) and differences resolved by discussion or by appeal to a third review author (AB). Results are presented in both a risk of bias graph and a risk of bias summary. Results of meta-analyses were interpreted in light of the findings with respect to risk of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

We used the following measures of the effect of treatment:

For dichotomous outcomes, we used the RR.

Dealing with missing data

We did not impute missing outcome data for any outcomes.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Heterogeneity between trials was assessed by visual inspection of forest plots, by estimation of the percentage heterogeneity between trials which cannot be ascribed to sampling variation (Higgins 2003) and by a formal statistical test of the significance of the heterogeneity (Deeks 2001). If there was evidence of substantial heterogeneity, the possible reasons for this were investigated and reported.

Assessment of reporting biases

We did not produce a funnel plot to assess the potential for small study effects, since there were only three trials in the primary meta-analysis.

Data synthesis

The trials of Mathiesen 2007, Sterling 2005 and van Seters 2008 were clinically similar enough to pool their results in a meta-analysis of response to treatment.

For the dichotomous outcome, response to treatment, the risk ratio (RR) was calculated for each trial and these RRs were then pooled.

Random effects models with inverse variance weighting was used for all meta-analyses (DerSimonian 1986).

RESULTS

Description of studies

Results of the search

The search strategy identified 2584 unique references. The abstracts of these were read independently by three review authors. The articles which did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded at this stage. Twelve articles were retrieved in full and translated into English where appropriate and up-dated versions of relevant studies were identified. The full text screening of these 12 references excluded eight of them for the reasons described in the table Characteristics of excluded studies. However four completed RCTs were identified that met our inclusion criteria; these are described in the table Characteristics of included studies. A recent publication in 2011(Terlou 2011) reported the seven year follow-up of patients in the treatment arm of one of the included studies (van Seters 2008). However, data from Terlou 2011 could not be included in meta-analysis as data for the control group at a comparable time-point were not available.

There is one ongoing randomised phase II multi-centre trial based in Cardiff UK. RT3VIN Clinical Trial (EudraCT no: 2006-004327-11) has two research arms and will assess the activity, safety and feasibility of use of two topical treatments, imiquimod and cidofovir (RT3VIN Clinical Trial). At the time of writing, no interim results were available and we await completion of this trial in September 2011.

Included studies

Design of studies

Four trials met our inclusion criteria. Mathiesen 2007, Sterling 2005 and van Seters 2008 examined the effect of imiquimod, whereas the trial of Naik 2006 assessed the use of the food additive I3C. In total these four trials assessed 113 patients. The three trials of Mathiesen 2007, Sterling 2005 and van Seters 2008 were conducted in Denmark, the United Kingdom and the Netherlands respectively and were prospective, randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trials. The Sterling 2005 trial was published as an abstract and, although we contacted the authors in October 2010 to request further information on the trial, we did not receive any further detailed information. This trial was included as it reported the data required for meta-analysis of the primary outcome. The Naik 2006 trial was conducted in a single centre in Gateshead, UK and was a randomised, unblinded trial where patients were randomised to receive two different doses of I3C; the trial had no placebo control.

Patient characteristics

All four trials randomised women with histologically proven VIN 2 or 3 (high grade VIN). The investigators gave histological definitions as either VIN 2 or 3 (van Seters 2008 and Mathiesen 2008 or high-grade VIN (Sterling 2005 and Naik 2006). None of the studies used the updated definitions of usual or differentiated types of VIN (Sideri 2005). All four trials included women aged between 21 and 72 years. All four trials reported that there was no difference in smoking status of women in each arm of the trials at randomisation. Mathiesen 2007, Sterling 2005 and van Seters 2008 reported that there were no difference in HPV infection between women in each treatment arm. Similarly, in the Naik 2006 trial there was no significant difference between women randomised to the two different dose groups, in terms of administration of hormonal therapy.

Intervention

Mathiesen 2007, Sterling 2005 and van Seters 2008 randomised patients to receive either topical imiquimod 5% or placebo. In the Mathiesen 2007 trial 21 patients received imiquimod and 10 received placebo. All patients applied topical treatment for 16 weeks. The regimen involved application once a week for two weeks, twice a week during the following two weeks and, if tolerated, three times a week for the last 12 weeks. The end-point of the study was 2 months after the end of treatment. In the van Seters 2008 trial, 26 patients received imiquimod and 26 received placebo. The patients applied treatment overnight twice a week for a period of 16 weeks. They were advised to use topical sulphur precipitate 5% in zinc oxide the day after application of treatment to avoid superinfection. In both these trials patients were reviewed every fourth week and a post treatment biopsy was taken after 6 months (24 weeks). In the van Seters 2008 trial further assessments were preformed at 7 and finally at 12 months following treatment, after which the randomisation code was revealed.

In the Sterling 2005 trial, 15 patients received imiquimod and six received placebo. It was not possible to ascertain the frequency of application, however active treatment continued for 16 weeks. Histological assessment was carried out 8 weeks after the end of treatment and at again after five months (20 weeks).

In the Naik 2006 trial, of the women completing the trial (three patients dropped out, one could not access the medication and two did not attend the six month follow-up), six were randomised to receive I3C 200 mg/day and seven received 400 mg/day. Vitamin C was also administered at the discretion of the treating clinician and five patients were prescribed this. Patients were reviewed at six weeks, three months and six months. Histological assessment was performed at six months (24 weeks).

Outcomes

All four trials reported outcomes in terms of clinical response, described as reduction of the size of the lesion(s) at vulvoscopic assessment, and histological response. Histological response was determined by a repeat biopsy either from the lesion or lesions, if they were still present, or from the area where a lesion had been at initial assessment, when it had regressed entirely.

van Seters 2008 defined clinical response as a reduction in total lesion size. The clinical responses were classified as either a complete response (CR) or partial response (PR). Partial responses were further subdivided into a strong partial response (76 to 99% reduction in lesion size) or a weak partial response (26 to 75% reduction in lesion size), or no response (reduction in lesion size of 25% or less). Histological response was described as change from high grade VIN to a lower grade or complete clearance. Mathiesen 2007 and Sterling 2005 both defined responses as either complete response (CR), which was defined as complete histological and clinical clearance, partial response (PR) ( > 50% clearance) and no response (< 50% clearance). Naik 2006 commented on the size of the lesions and histological assessments without grouping responses further.

van Seters 2008 was the only trial to document progression to invasive cancer after 12 months. Sterling 2005 and van Seters 2008 tested for HPV status at the beginning of the trial. However onlyvan Seters 2008 described the proportion of initially HPV-positive patients who cleared the virus at end of the study period.

van Seters 2008 was the only trial to report QoL comprehensively by means of recognised questionnaires administered at baseline, 20 weeks and 12 months. The questionnaires used to assess QoL were: the mental health scale of the Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form General Health Survey (ranging from 0 to 100, with higher numbers indicating a better health-related QoL); the overall QoL scale of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) QoL questionnaire (QLQ-C30) used to assess generic and cancer-specific health-related QoL; and the EORTC QLQBR23 to assess body image and sexuality.

Mathiesen 2007 asked patients to keep a diary of compliance to treatment and to respond to a questionnaire at home on local side effects. Naik 2006 asked patients to report symptoms of pruritus and pain using a visual analogue scale at recruitment and at each subsequent visit. One patient reported stomach upset, a known side effect of this treatment. We were unable to ascertain whetherSterling 2005 requested patients to report on side effects or symptoms.

Excluded studies

Eight references listed were excluded after obtaining the full text (see Characteristics of excluded studies).

Spirtos 1990 (also reported in abstract form prior to full publication) was a prospective randomised blinded cross-over trial using topical α-IFN with and without 1% nonoxynol-9. However, only patients who did not respond to the initial treatment were crossed over to the other treatment arm, so interpretation of this trial’s results was not possible. Todd 2005 was a review; Iavazzo 2008 andMahto 2010 were systematic reviews; van de Nieuwenhof 2008 and Mathiesen 2008 were letters replying to comments on theMathiesen 2007 RCT by the same group; Melamed 1965 was not an RCT.

Risk of bias in included studies

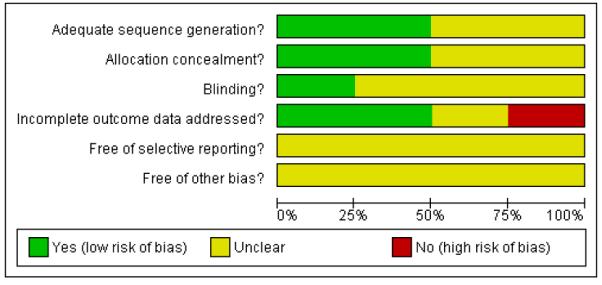

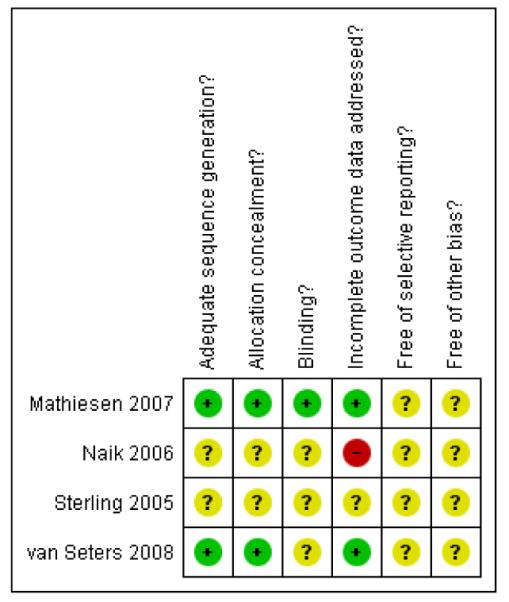

Only the trial of Mathiesen 2007 was at low risk of bias, as it satisfied four of the criteria that we used to assess risk of bias. Thevan Seters 2008 trial was at moderate risk of bias as it satisfied three criteria, whereas the trials of Naik 2006 and Sterling 2005 were at high risk of bias, as they did not satisfy any of the criteria (see Figure 1, Figure 2). Sterling 2005 was in abstract form and the full paper was not available, so we were unable to assess its risk of bias.

Figure 1.

Methodological quality graph: review authors’ judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Figure 2.

Methodological quality summary: review authors’ judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Two trials (Mathiesen 2007; van Seters 2008) reported the method of generation of the sequence of random numbers used to allocate women to treatment arms and that this allocation was adequately concealed. These trials also analysed all of the women included in the trial. These risk of bias items were not reported in the other two trials (Naik 2006; Sterling 2005) and a very small number of women (12) were analysed in the Naik 2006 trial. Only theMathiesen 2007 trial reported whether the patients, health care professionals and outcome assessors were blinded. This was unclear in the remaining three trials. It was not certain whether all trials reported all the outcomes that they assessed and it was unclear whether any other bias may have been present.

Effects of interventions

In the meta-analysis comparing topical imiquimod with placebo for treatment of VIN, two studies (Mathiesen 2007 and Sterling 2005) had no responders in the placebo arm, so we added 0.5 to these cells to allow calculation of a RR. This is the default zero-cell correction within RevMan, and biases the result of the meta-analysis towards no difference between imiquimod and placebo. For dichotomous outcomes that were reported by only one study (severe erythema and oedema in the comparison of topical imiquimod versus placebo and mild bowel upset in the comparison of 200 versus 400 mg/day of I3C), we were unable to estimate a RR as one of the treatment groups experienced no events.

Topical imiquimod versus placebo

In Analysis 1.1 and Analysis 1.2 complete and partial response were grouped together and were deemed ’response’.

Response to treatment at 5 to 6 months

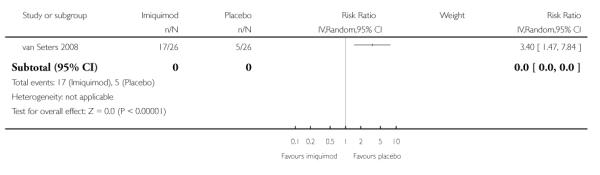

Meta-analysis of three RCTs (Mathiesen 2007; Sterling 2005; van Seters 2008), assessing 104 participants, found that the proportion of women who responded to treatment at 5 to 6 months was much higher in the group who received topical imiquimod than in the group who received placebo (RR = 11.95, 95% CI: 3.21 to 44.51). The percentage of the variability in effect estimates that was due to heterogeneity between studies rather than sampling error (chance) was not important (I2 = 0%). There were 18/62 and 1/42 partial responses and 36/62 and 0/42 complete responses in the topical imiquimod and placebo groups respectively. Analysis 1.1

Response to treatment at 12 months

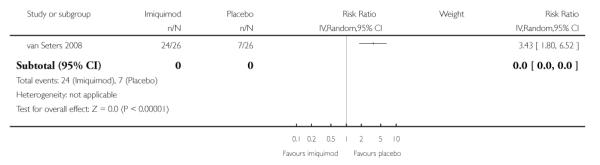

In the trial of van Seters 2008, the proportion of women who responded to treatment at 12 months was much higher in the group who received who received topical imiquimod than in the group who received placebo (RR = 9.10, 95% CI: 2.38 to 34.77). There were 10/24 and 2/23 partial responses and 9/24 and 0/23 complete responses in the topical imiquimod and placebo groups respectively. The response status was unknown for two women in the imiquimod group and three women in the placebo group, as they were lost to follow-up. Analysis 1.2

Progression to vulval cancer at 12 months

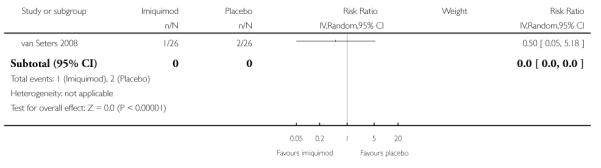

The trial of van Seters 2008 did not find any statistically significant difference in progression to vulval cancer at 12 months between women who received imiquimod and those who received placebo (RR = 0.50, 95% CI: 0.05 to 5.18). Analysis 1.3

Pain due to VIN

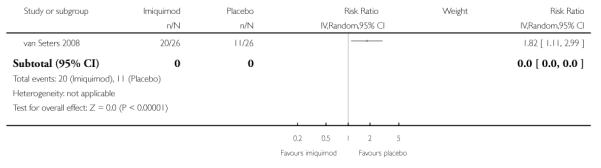

In the trial of van Seters 2008, women who received topical imiquimod had a higher risk of pain due to VIN than those who received placebo (RR= 1.82, 95% CI: 1.11 to 2.99). Analysis 1.4

Pruritis due to VIN

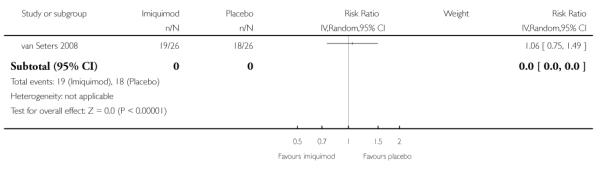

The trial of van Seters 2008 did not find any statistically significant difference in risk of pruritis due to VIN between women who received imiquimod and those who received placebo (RR = 1.06, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.49). Analysis 1.5

Adverse events

Erythema (Analysis 1.6), erosion (Analysis 1.7), oedema, pain or pruritis (Analysis 1.8) were reported only in the trial of van Seters 2008; local side effects (Analysis 1.9) were reported only in theMathiesen 2007 trial.

Mild to moderate erythema (see Analysis 1.6)

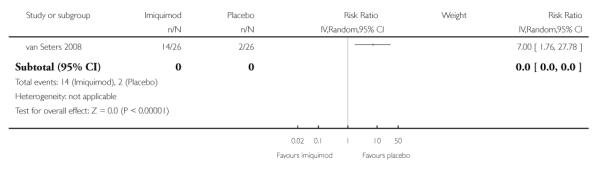

Women who received imiquimod were seven times more likely to suffer mild to moderate erythema than those who received placebo (RR = 7.00, 95% CI: 1.76 to 27.78).

Severe erythema

Women who received imiquimod had a significantly (P = 0.02) higher risk of severe erythema than those who received placebo, based on six cases, (6/26 in the imiquimod group and 0/26 in the placebo group).

Erosion

Women who received imiquimod had more than three times the risk of erosion compared to women who received placebo (RR = 3.40, 95% CI: 1.47 to 7.84). Analysis 1.7

Oedema

Women who received imiquimod had a significantly (P < 0.001) higher risk of oedema than those who received placebo, based on eleven cases, (11/26 in the imiquimod group and 0/26 in the placebo group).

Pain or pruritus due to VIN

Women who received imiquimod were over three times more likely to suffer pain or pruritus due to VIN than those who received placebo (RR= 3.43, 95% CI: 1.80 to 6.52). Analysis 1.8

Local side effects

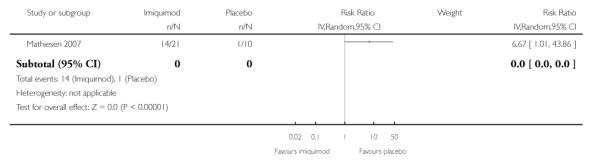

Women who received imiquimod were over six times more likely to suffer local side effects than those who received placebo, (RR = 6.67, 95% CI: 1.01 to 43.86), but this was of borderline statistical significance (P = 0.05). Analysis 1.9

Quality of life

The van Seters 2008 authors did not find any significant differences in any of the QoL questionnaires regarding self-reported health-related QoL, body image or sexuality scores at baseline, 20 weeks, and at 12 months between the treatment and the placebo groups. None of the other trials reported on QoL.

200 versus 400 mg/day of indole-3-carbinol (I3C)

The trial of Naik 2006 reported that there were no significant differences in any of the outcomes between the six women taking 200 mg/day of I3C and the six on 400 mg/day. Both groups reported significant improvement in symptoms of pruritus and pain. However, nine out of 10 patients followed up for 6 months still had high grade VIN after biopsy. The authors did not comment on which of the two doses these patients had been randomised to. The trial reported only one case of mild bowel upset, which was of a woman who received the high dose regimen.

DISCUSSION

Summary of main results

Only imiquimod has been subjected to placebo-controlled RCTs (Mathiesen 2007; Sterling 2005; van Seters 2008). Our analysis showed that women with high grade VIN who received imiquimod had a much better response to treatment than those who received placebo , in terms of achieving either complete clearance of lesions or significant reduction in size and histological grade of residual lesions (RR = 11.95, 95% CI: 3.21 to 44.51 and RR = 9.10, 95% CI: 2.38 to 34.77 for response at 5 to 6 months and 12 months respectively).The analysis showed that imiquimod was relatively well tolerated although it was associated with significantly more local side effects than placebo. These side effects included localised pain, oedema, erythema and a single case of an erosion. Encouragingly, none of the patients discontinued treatment and these side effects were managed by reducing the number of applications. The total number of patients in these trials was small (n = 104). Only one trial followed patients up for 12 months (van Seters 2008), in this trial, three patients progressed to invasive disease, one in the imiquimod arm and two in the placebo arm. The same trial reported significantly increased clearance of HPV infection with imiquimod treatment. QoL was only addressed in a single trial where no differences were found between the two groups(van Seters 2008).

One trial (Naik 2006) that met our inclusion criteria, but included only 12 patients, this trial assessed low dose (200 mg/day) versus high dose (400 mg/day) 13C. Although both groups reported significant improvement in symptoms of pruritus and pain, nine out of 10 patients followed up for 6 months still had high grade VIN after biopsy. The authors did not report which of the two doses these patients had received.The authors reported that there were no significant differences in any of the outcomes recorded between those women taking 200 mg/day of I3C and those on 400 mg/day.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

VIN is a relatively rare condition which can cause significant morbidity for affected patients. The association of VIN with oncogenic human papilloma viruses (16/18) gives it the propensity to progress to invasive vulval cancer (Smith 2009). Surgical management has the advantage of removing discrete, unifocal small lesions but does not prevent recurrence and can have a significant psychosexual impact on younger patients.The outcomes of a systematic review of the surgical interventions for VIN are published in a separate review (Kaushik 2011). We were unable to identify any RCTs that compared medical intervention and surgical management for high grade VIN . The current review aimed to assess the available evidence for the efficacy and safety of alternative, less invasive, medical treatments for this condition. Only RCTs that assessed imiquimod and I3C for the medical management of VIN were included.

Overall, the quality of the evidence was moderate (GRADE Working Group) for the use of imiquimod to treat high grade VIN compared to placebo, although some of the outcomes were incompletely reported and many analyses were based on single trials. The analysis found that imiquimod compared to placebo is an effective and reasonably safe alternative for treating high grade VIN, provided patients are monitored closely to identify progression to invasive disease and warned of the temporary side effects.Mathiesen 2007 reported that 14 of 21 patients (67%) had to decrease the frequency of applications due to side effects, but none discontinued treatment. Likewise, van Seters 2008 reported that 25 of 26 patients reported symptoms, but again these were not sufficient to discontinue treatment. Imiquimod can be used in an individualised manner for patients wishing to avoid disfiguring surgery, provided regular assessments are performed to identify and manage possible invasion promptly. The analysis is limited by the relatively small number of patients enrolled and the lack of long term follow up (beyond 12 months). Although the RCTs included do not address disease recurrence or progression to cancer beyond 12 months, Terlou 2011 reported the seven year follow-up of 24 out of the 26 patients treated with imiquimod in the trial of van Seters 2008, where none of these patients developed vulval cancer.

The absence of sufficient data on QoL, sexual function and adverse events does not allow any firm conclusions to be drawn for these outcomes. Furthermore, the included trials have not clearly distinguished between the efficacy of treatment in unifocal and multifocal disease.

This review did not include HPV clearance as an outcome despite the association of high risk HPV infection with progression of VIN to vulval cancer (de Vuyst 2009). The studies included did not define whether patients had usual type (HPV related) or differentiated type (lichen-sclerosus related) of VIN at randomisation. Only van Seters 2008 described the proportion of initially HPV-positive patients who cleared the virus at end of the study period; they found that patients treated with imiquimod had a significantly higher rate of clearance than the placebo group (15 of 25 imiquimod group versus 2/25 in placebo group P < 0.001). Concerning other types of medical interventions, we identified only one other RCT, which compared two doses of the food additive, I3C (Naik 2006). This trial included only 12 patients and stated that there was a significant improvement in symptoms and reduction in the sizes of the lesions in all patients treated, which could be largely due to a placebo effect. There were no significant differences in outcomes between women receiving the two doses of I3C. This food additive was well tolerated, but we cannot assess its overall efficacy for the treatment of high grade VIN, since no placebo controlled trials were available.

Quality of the evidence

This review is based on three trials (Mathiesen 2007; Sterling 2005;van Seters 2008) that compared topical imiquimod with placebo and one trial (Naik 2006) that looked at low versus high dose I3C in women with high grade VIN. These trials included a total of 117 patients with the disease.

Risk of bias in the trials ranged from low to high, but this was largely due to the trial of Sterling 2005 being an abstract for which we were not able to obtain further details concerning patient outcome and follow up. The trials that evaluated imiquimod were randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trials without significant drop out rates, making them reliable sources of evidence. Only one of the trials followed up patients for 12 months (van Seters 2008). The short period of follow up was a significant draw back in the design of all three trials, as it did not allow long-term assessment of recurrence and progression to invasive disease. Finally, reporting of QoL and symptoms was poor in all trials, with only one trial (van Seters 2008) using validated instruments/ questionnaires. Adverse events, HPV clearance from lesion and pain and pruritis due to VIN outcomes were incompletely documented, since they were also restricted to single trial analyses.

The trial of Naik 2006 did not compare I3C to a control or alternative intervention so it was not possible to reach any conclusions about its efficacy.

Potential biases in the review process

A comprehensive search was performed, including a thorough search of the grey literature and all studies were sifted and data extracted by at least two reviewers independently. We restricted the included studies to RCTs as they provide the strongest level of evidence available. Hence we have attempted to reduce bias in the review process.

The greatest threat to the validity of the review is likely to be the possibility of publication bias i.e. studies that did not find the treatment to have been effective may not have been published. We were unable to assess this possibility as all the treatment comparisons were restricted to either a meta analysis of only three trials or single trial analyses.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

There are two recent comprehensive reviews of the use of imiquimod for VIN, as well as VAIN, by Iavazzo 2008 and anogenital intraepithelial neoplasia by Mahto 2010. The latter includedvan Seters 2008 and Mathiesen 2007, two of the three RCTs we included in our analysis. Our analysis also included Sterling 2005. However, Mahto 2010 also collected results from observational cohort studies (case series) and published case reports. Our analysis agreed with the conclusions these reviews presented, namely the favourable evidence for efficacy of imiquimod and the reasonably tolerable side-effects. None of the patients were hospitalised or discontinued treatment due to severe side effects. Mathiesen 2007 reported that 14 out of 21 patients (67%) had to decrease the frequency of applications due to side effects, and van Seters 2008 reported that 25 out of 26 patients reported symptoms, but again these were not sufficient to discontinue treatment. This is in agreement with a published case series (Todd 2002) where 13 out of 15 patients reported significant side effects resulting in reduction of frequency of applications per week, but none of the patients discontinued treatment. Wendling 2004 reported on a case series of 12 patients where three out of 12 patients (43%) discontinued treatment due to side effects Todd 2002 concluded that the lack of response to treatment could be attributed to decreased administration of the treatment and that local anaesthetics should be applied to improve compliance. The authors of the three RCTs included in this analysis did not make any reference to the need for local anaesthesia nor to an apparent relationship between the change in frequency of administrations and response to treatment. One of the draw backs of all published RCTs, is the lack of long term follow-up of patients treated with imiquimod. A recent publication by the authors of one of the included studies in this analysis (van Seters 2008), has shown the seven year follow-up of 24 out of 26 patients treated with imiquimod in their original trial (Terlou 2011). The median follow up period of complete responders to imiquimod was 7.3 years (range 5.6 to 8.3 years), and eight of the nine had no recurrence of VIN. One patient had a recurrence after 4 years, which was treated with laser vapourisation. Median follow up in the partial responders was 7.2 years (range 5.7 to 8.3 years) and all but two patients had local excision or laser treatment. There were no reported cases of invasive vulval carcinoma. Although they did not report the follow up of the control group, this study has added valuable information concerning the long term safety and efficacy of imiquimod (Terlou 2011).

A trial that did not meet our inclusion criteria because it was a phase II trial with no comparison arm, demonstrated the potential efficacy of sequential imiquimod and photodynamic therapy in treating high grade VIN (Winters 2008). This trial included 20 patients and the authors reported that there was evidence of response to imiquimod alone at 10 weeks. Of the patients who tolerated treatment at 26 weeks, four had complete response, eight had partial responses and eight had stable disease. There were no cases of progression to invasive disease over 52 weeks. The authors recognised that completion of the treatment regimen may have resulted in better outcomes. However, delivery of photodynamic therapy was intolerable for a large proportion of patients making this treatment modality difficult to adopt without effective pain relief. Similarly the van Seters 2008 trial the Winters 2008 trial reported that all 5 complete responders had cleared the HPV virus. A further RCT that did not meet our inclusion criteria based on the study design and reporting of outcomes, was a double-blinded cross-over trial testing α-IFN with or without nonoxynol-9, a surfactant used to improve absorption on patients with VIN III (Spirtos 1990). In this trial 21 patients were randomised initially to one of the two arms. Patients who failed to respond were crossed over to the other treatment arm. Therefore it is not possible to make any valid comparisons of the treatment regimens. The authors concluded that nonoxynol-9 did not add any benefit to treatment.

Concerning 13C, the Naik 2006 trial was the first trial to assess the efficacy of I3C in treating high grade VIN. It compared low and high doses of I3C. The trial only enrolled 12 women, so it was not possible to draw robust conclusions about its efficacy, although the results of the biopsies of nine patients showed that 8 still had high grade VIN at 6 months following treatment.

Finally, we await completion of the RT3VIN Clinical Trial, as this will allow further assessment of cidofovir and more importantly, its comparison with imiquimod for treatment of high grade VIN3. The results of this trial will be included in the update of this review.

AUTHORS’ CONCLUSIONS

Implications for practice

Compared to placebo imiquimod appears to be a relatively effective medical intervention for the treatment of high grade VIN. Its safety however, is yet to be fully established. From the single trial analyses, other reviews and the literature to-date it seems relatively safe, provided patients are warned of the temporary side effects and monitored closely to identify progression to invasive disease in the long term.

Implications for research

Well designed placebo-controlled double-blind randomised trials of sufficient power and duration are required to determine the efficacy of any new intervention in patients with high grade VIN. Such trials need to use outcome measures that are both objective and important to patients such as recurrence rates, disease-free interval, progression to invasive disease and effects on QoL. Future trials should use the new classification to differentiate between usual type and differentiated type of VIN as well as assess HPV clearance after treatment. In terms of imiquimod trials, we can be fairly confident of its efficacy and more evidence is accumulating concerning its long term safety; but more trials may be needed to establish whether adverse events are acceptable. Once effective and safe treatments have been identified, dose ranging trials can be conducted to attempt to find the optimal dosage. Ideally a multi-centre trial comparing surgical management to proven medical interventions should be undertaken. We also await development and completion of trials assessing adjuvant treatments such imiquimod and HPV vaccination for treatment of this condition.

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY.

Comparison of medical procedures for women diagnosed with precancerous changes of the vulva (high grade vulval intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN))

Vulval intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) is a skin condition affecting the vulval skin which if left untreated may become cancerous. Distressing symptoms include itching, burning, and soreness of the vulva or painful intercourse. There may be discolouration and various other visible changes to the vulval skin. There are two types of VIN: the most common type is associated with infection of the cells of the vulva with a virus called human papilloma virus (now known as usual type VIN), whereas the other type is not associated with this viral infection (now known as differentiated VIN). VIN is becoming more common in younger women. At the moment treatments are aimed at relieving distressing symptoms and ensuring that the condition does not become cancerous. At present the most common treatment option for women with this condition is surgery to remove the affected skin areas. Surgery however does not guarantee a cure and can be disfiguring, and may result in physical and psychological problems in younger women who are sexually active. The purpose of this review was to identify any alternative therapies that can be used to treat this condition safely.

The medical treatments identified included topical treatments such as imiquimod, cidofovir, alpha-interferon (α-IFN), 5-fluorouracil, bleomycine and trinitrochlorobenzene or oral tablets such as indole-3-carbinol (a food additive). Only trials that examined imiquimod and indole-3-carbinol met the inclusion criteria for the review. There is evidence that VIN persists and may progress to cancer when the body’s defence system (immune system) does not clear the affected cells. Most of these treatments (imiquimod, indole-3-carbinol, cidofovir and α-IFN) work by enhancing the body’s immune system, but some treatments (5-fluorouracil, bleomycine and trinitrochlorobenzene) work by destroying the affected cells. Treatments such as α-IFN and 5-fluorouracil cause distressing local side effects, including painful ulceration of the vulva without proving to be effective to patients, so they are no longer used.

We found four relevant trials (three trials of imiquimod and one of indole-3-carbinol). Although the trials assessing imiquimod included only 104 patients they showed that imiquimod appeared to be effective and reasonably safe in treating high grade VIN. It can cause side effects such as more soreness and itching of the skin over the vulva, but not enough to stop treatment completely. The trials only followed patients for 20 weeks, six months or 12 months so we cannot comment on the longer term outcomes and whether the disease progressed to cancer after 12 months despite treatment. The trial of indole-3-carbinol compared two different doses of the medication which appeared to be safe but we cannot tell if it is as effective as imiquimod or surgery.

More research is needed with larger numbers of patients in order to find an alternative medical treatment for high grade VIN that is safe. Currently imiquimod appears to be reasonably safe and effective but patients need to be monitored closely long term.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Chris Williams for clinical and editorial advice, Jane Hayes for designing the search strategy and Gail Quinn and Clare Jess for their contribution to the editorial process. We thank the peer reviewers for their helpful comments.

SOURCES OF SUPPORT

Internal sources

No sources of support supplied

External sources

Department of Health, UK.

NHS Cochrane Collaboration programme Grant Scheme CPG-506

CHARACTERISTICS OF STUDIES

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | RCT single centre 31 women (21 imiquimod arm and 10 in placebo arm) |

|

| Participants |

Age: mean 47.8 years, range 21-68 VIN grade/type: VIN2 (n=2), VIN 3 (n=29), unifocal lesion (n=22), multifocal lesions (n=9) Smoking status: active (n=25) , former (n=3) , never (n=2), unknown (n=1) HPV status: positive (n=18), negative (n= 8), missing (n=5) |

|

| Interventions | - imiquimod vs placebo - treatment for 16 weeks (once a week for 2 weeks, then twice a week the following 2 weeks, if tolerated three times a week for the last 12 weeks) |

|

| Outcomes | Response to treatment at 2, 6 and 12 months. Compliance to treatment Local side effects |

|

| Notes | Review every 4 weeks and a biopsy taken if suspicion of progression | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | “Randomisation was performed by computer programme at a study randomisation centre” |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | “The medicines were then packed into sachets at the University Hospital of Aarhus pharmacy in accordance with the randomisation list. The randomisation list was not available to the investigators until the last patient included had been evaluated clinically and histologically 2 months after end of treatment” |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Low risk | “The treatment modality was blinded to the pathologist as well as to the investigators and to the patients” |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Low risk | % analysed: 31/31 (100%) |

| Free of selective reporting? | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement |

| Free of other bias? | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to assess whether an important risk of bias exists |

| Methods | RCT. Single centre 13 women randomised |

|

| Participants |

Age: mean 44.6 years, range: 26-63, VIN grade: all 13 :high-grade, unifocal (n=9), multifocal (n=3) Smoking: smokers (n=9), non-smokers (n=3) Hormonal therapy: COP (n=1), HRT (n=1) HPV status: not documented |

|

| Interventions | Oral indole-3-carbinol: 200 mg/day vs 400 mg/day for 6 months | |

| Outcomes | Response to treatment: 6 weeks, 12 weeks and 6 months Urine: 2-hydroxyestrone:16-alpha-hydroxyestrone ratio Symptom improvement Side effects |

|

| Notes | Vitamin C was commenced at the discretion of the investigator | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

High risk | % analysed: 10/13 (77%) “One patient was withdrawn from the study at the 6-week visit as there was difficulty in obtaining the I3C and two women did not attend the 6-month review” |

| Free of selective reporting? | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement |

| Free of other bias? | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to assess whether an important risk of bias exists |

| Methods | RCT Single centre. 21 women randomised |

|

| Participants |

Age: mean 47 years, range 26-63 years VIN grade: 21 high grade Smoking: not documented HPV status: “almost all women” |

|

| Interventions | Imiquimod vs placebo for 16 weeks | |

| Outcomes | Response to treatment: 8 weeks and 20 weeks. HPV clearance |

|

| Notes | Abstract not full paper | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Free of selective reporting? | Unclear risk | Unclear |

| Free of other bias? | Unclear risk | Unclear |

| Methods | RCT 52 women randomised |

|

| Participants |

Age: -intervention group: median 39 years, range 22-56; placebo group: median 44 years, range 31-71 VIN grade: VIN 2 (n=4), VIN 3 (n=47), not reported (n=1) Smoking status: smokers (n=46) and nonsmokers (n=6). HPV status: positive (n=50), negative (n=2) |

|

| Interventions | imiquimod vs placebo for 16 weeks (twice weekly) | |

| Outcomes | Response to treatment at 20 weeks (biopsy), 7 months and 12 months (+/− repeat biopsy) Symptoms (pain, pruritus), severe erythema QoL Side effects |

|

| Notes | Patients advised to use sulphur precipitate 5% in zinc oxide ointment the day after application to avoid superinfection 4 weekly review with biopsy if suspicion of progression |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | “Randomization was carried out by 3M Pharmaceuticals in blocks of four (with a two-by-two design) without stratification” |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | “Except for cases of serious side effects, the randomization code was not broken until all women had been seen at 12 months” |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Unclear risk | “Double-blind, randomized clinical trial“, but it was unclear as to whether the outcome assessors were blinded |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Low risk | % analysed: 52/52 (100%) at 20 weeks. All but three patients were followed up for 12 months. |

| Free of selective reporting? | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement |

| Free of other bias? | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to assess whether an important risk of bias exists |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Iavazzo 2008 | This is a review of the use of imiquimod in high grade VIN and vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia (VAIN). The studies included were either observational cohort studies (case series) or case reports published between 1997 and 2007. The only RCT included in this review was Mathiesen 2007 this trial was already included in our analysis. |

| Mahto 2010 | This was a recent review of the use of imiquimod in anogenital intraepithelial neoplasia, it included studies for VIN, penile and anal intraepithelial neoplasia. Similarly to Iavazzo 2008 it included observational cohort studies (case series) or case reports published between 1997 and 2008 with the addition of a second RCT van Seters 2008 also included in our review. |

| Mathiesen 2008 | This publication was a response to the letter by van de Nieuwenhof 2008 referring to the authors trial (Mathiesen 2007). |

| Melamed 1965 | This was a Russian article describing the condition and was not an RCT. There was no active medical treatment in 1965 |

| Spirtos 1990 | This was a cross over trial that did not use a true randomised cross over approach as cross over was conditional on patient response/non-response - lack of a clear time line of treatment for each patient. - the exact duration of treatment in each arm, for the patients that were crossed over was not stated |

| Todd 2005 | Review article looking at various modalities of treatment. |

| van de Nieuwenhof 2008 | Letter to the editor referring to the trial of Mathiesen 2007. |

Characteristics of ongoing studies [ordered by study ID]

| Trial name or title | RT3VIN EudraCT no: 2006-004327-11 |

|---|---|

| Methods | This is a multi centre trial based in Cardiff UK. This is a randomised phase II trial of two research arms comparing imiquimod and cidofovir |

| Participants | ≥16 years old (102 in each arm) Biopsy proven VIN 3 (including visible perianal disease not extending into the anal canal) , within three months At least one lesion measured using RECIST criteria) with longest diameter ≥ 20mm |

| Interventions | Application three times a week for a maximum of 24 weeks. Should a complete response be observed before 24 weeks, treatment will be stopped and repeat biopsies carried out six weeks later |

| Outcomes | Histologically confirmed complete response by 30 weeks. Symptomatic improvement, concordance and toxicities, viral clearance, HPV integration status and response to treatment and recurrence rate at two years (in complete responders) |

| Starting date | 2008 |

| Contact information | helen.phillips@wctu.wales.nhs.uk, tel: 029 2068 7461 |

| Notes | Completion September 2011 |

DATA AND ANALYSES

Comparison 1.

Topical imiquimod versus placebo

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Response to treatment at 5-6 months | 3 | 104 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 11.95 [3.21, 44.51] |

| 2 Response to treatment at 12 months | 1 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3 Progression to vulvar cancer at 12 months | 1 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4 Pain due to disease | 1 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 5 Pruritis due to disease | 1 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 6 Mild to moderate Erythema | 1 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 7 Erosion | 1 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 8 Pain or pruritus | 1 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 9 Local side effects | 1 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only |

Analysis 1.1. Comparison 1 Topical imiquimod versus placebo, Outcome 1 Response to treatment at 5-6 months

Review: Medical interventions for high grade vulval intraepithelial neoplasia

Comparison: 1 Topical imiquimod versus placebo

Outcome: 1 Response to treatment at 5-6 months

|

Analysis 1.2. Comparison 1 Topical imiquimod versus placebo, Outcome 2 Response to treatment at 12 months

Review: Medical interventions for high grade vulval intraepithelial neoplasia

Comparison: 1 Topical imiquimod versus placebo

Outcome: 2 Response to treatment at 12 months

|

Analysis 1.3. Comparison 1 Topical imiquimod versus placebo, Outcome 3 Progression to vulvar cancer at 12 months

Review: Medical interventions for high grade vulval intraepithelial neoplasia

Comparison: 1 Topical imiquimod versus placebo

Outcome: 3 Progression to vulvar cancer at 12 months

|

Analysis 1.4. Comparison 1 Topical imiquimod versus placebo, Outcome 4 Pain due to disease

Review: Medical interventions for high grade vulval intraepithelial neoplasia

Comparison: 1 Topical imiquimod versus placebo

Outcome: 4 Pain due to disease

|

Analysis 1.5. Comparison 1 Topical imiquimod versus placebo, Outcome 5 Pruritis due to disease

Review: Medical interventions for high grade vulval intraepithelial neoplasia

Comparison: 1 Topical imiquimod versus placebo

Outcome: 5 Pruritis due to disease

|

Analysis 1.6. Comparison 1 Topical imiquimod versus placebo, Outcome 6 Mild to moderate Erythema

Review: Medical interventions for high grade vulval intraepithelial neoplasia

Comparison: 1 Topical imiquimod versus placebo

Outcome: 6 Mild to moderate Erythema

|

Analysis 1.7. Comparison 1 Topical imiquimod versus placebo, Outcome 7 Erosion

Review: Medical interventions for high grade vulval intraepithelial neoplasia

Comparison: 1 Topical imiquimod versus placebo

Outcome: 7 Erosion

|

Analysis 1.8. Comparison 1 Topical imiquimod versus placebo, Outcome 8 Pain or pruritus

Review: Medical interventions for high grade vulval intraepithelial neoplasia

Comparison: 1 Topical imiquimod versus placebo

Outcome: 8 Pain or pruritus

|

Analysis 1.9. Comparison 1 Topical imiquimod versus placebo, Outcome 9 Local side effects

Review: Medical interventions for high grade vulval intraepithelial neoplasia

Comparison: 1 Topical imiquimod versus placebo

Outcome: 9 Local side effects

|

DIFFERENCES BETWEEN PROTOCOL AND REVIEW

Restriction to RCTs

We had initially specified in the protocol in the ’types of studies’ section that we would include RCTs and quasi-RCTs, but we decided to exclude quasi-RCTs to ensure higher quality evidence.

We did not find time-to-event or continuous data and adjusted statistics were not reported so the following text was removed from the data extraction and management and measures of treatment effect sections:

Data extraction and management

We did not find time-to-event or continuous data and adjusted statistics were not reported so the following text was removed from the data extraction and management and measures of treatment effect sections:

For time to event (disappearance or progression of lesion, time to progression to cancer) data, we will extract the log of the hazard ratio [log(HR)] and its standard error from trial reports; if these are not reported, we will attempt to estimate them from other reported statistics using the methods of Parmar 1998.

For continuous outcomes (e.g. QoL measures), we will extract the final value and standard deviation of the outcome of interest and the number of patients assessed at endpoint in each treatment arm at the end of follow-up, in order to estimate the mean difference (if trials measured outcomes on the same scale) or standardised mean differences (if trials measured outcomes on different scales) between treatment arms and its standard error.

Both unadjusted and adjusted statistics will be extracted, if reported.

Measures of treatment effect

For time to event data, we will use the HR, if possible. The HR summarises the chances of survival in women who received one type of treatment compared to the chances of survival in women who received another type of treatment. However, the logarithm of the HR, rather than the HR itself, is generally used in meta-analyses.

For continuous outcomes, we will use the mean difference between treatment arms.

The review was restricted to only four included trials so the following section on reporting biases was removed:

Assessment of reporting biases

Funnel plots corresponding to meta-analysis of the primary outcome will be examined to assess the potential for small study effects. When there is evidence of small-study effects, publication bias will be considered as only one of a number of possible explanations. If these plots suggest that treatment effects may not be sampled from a symmetric distribution, as assumed by the random effects model, sensitivity analyses will be performed using fixed effects models.

We did not find time-to-event or continuous data and adjusted statistics were not reported so the following text was removed:

Data synthesis

Adjusted summary statistics will be used if available; otherwise unadjusted results will be used.

For time-to-event data, HRs will be pooled using the generic inverse variance facility of RevMan 5.

For continuous outcomes, the mean differences between the treatment arms at the end of follow-up will be pooled if all trials measured the outcome on the same scale, otherwise standardised mean differences will be pooled.

None of the trials had three or more arms so we removed the following two paragraphs:

If any trials have multiple intervention groups, the control group will be divided between the intervention groups to prevent double counting of participants in the meta-analysis and comparisons between each intervention and a split control group will be treated independently.

If sufficient data are available, indirect comparisons, using the methods of Bucher 1997 will be used to compare competing interventions that have not been compared directly with each other.

None of the trials subgrouped by unifocal and multifocal lesions so we removed the following section:

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Sub-group analyses will be performed, grouping the trials by multifocal and unifocal lesions as their treatment modalities may differ

Factors such as age, VIN stage, size of lesion, type of intervention and length of follow-up will be considered in interpretation of any heterogeneity.

The review was restricted to only four trials and a meta analysis of three trials for non-response to treatment so we did not carry out sensitivity analysis. We had specified the following in the protocol:

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses will be performed, excluding studies which did not report adequate (i) concealment of allocation, (ii) blinding of the outcome assessor.

Appendix 1. MEDLINE search strategy

Ovid Medline 1950 to September week 1, 2010

(VIN or VIN2 or VIN3).mp.

(vulva* adj5 intraepithelial neoplasia).mp.

1 or 2

exp Vulva/

vulva*.mp.

4 or 5

exp Precancerous Conditions/

(pre-cancer* or precancer*).mp.

dysplasia.mp.

unifocal.mp.

multifocal.mp.

exp Carcinoma in Situ/

carcinoma in situ.mp.

7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13

6 and 14

3 or 15

key: mp=title, original title, abstract, name of substance word, subject heading word

Appendix 2. Embase search strategy

Embase Ovid 1980 to week 36, 2010

(VIN or VIN2 or VIN3).mp.

(vulva* adj5 intraepithelial neoplasia).mp.

1 or 2

exp Vulva/

vulva*.mp.

4 or 5

exp Precancer/

(pre-cancer* or precancer*).mp.

dysplasia.mp.

unifocal.mp.

multifocal.mp.

exp Carcinoma in Situ/

carcinoma in situ.mp.

8 or 11 or 7 or 13 or 10 or 9 or 12

6 and 14

3 or 15

key: mp=title, abstract, subject headings, heading word, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer name

Appendix 3. Central search strategy

CENTRAL Issue 3, 2010

(VIN or VIN2 or VIN3):ti,ab,kw

(vulva* near/5 intraepithelial neoplasia):ti,ab,kw

(#1 OR #2)

MeSH descriptor Vulva explode all trees

vulva*

(#4 OR #5)

MeSH descriptor Precancerous Conditions explode all trees

pre-cancer* or precancer*

dysplasia

unifocal

multifocal

MeSH descriptor Carcinoma in Situ explode all trees

carcinoma in situ

(#7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13)

(#6 AND #14)

(#3 OR #15)

key: ti,ab,kw = title, abstract, keyword

HISTORY

Protocol first published: Issue 3, 2009

Review first published: Issue 4, 2011

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 26 February 2014 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

WHAT’S NEW

Last assessed as up-to-date: 7 March 2011.

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 27 March 2014 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

Footnotes

DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST None

References to studies included in this review

- Mathiesen 2007 {published data only} .Mathiesen O, Buus SK, Cramers M. Topical imiquimod can reverse vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia: A randomised, double-blinded study. Gynecologic Oncology. 2007;107(2):219–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naik 2006 {published data only} .Naik R, Nixon S, Lopes A, Godfrey K, Hatem MH, Monaghan JM. A randomized phase II trial of indole-3-carbinol in the treatment of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer. 2006;Vol. 16(issue 2):786–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2006.00386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterling 2005 {published data only} .Sterling JC, Smith NA, Loo WJ, Cohen C, Neill S, Nicholson A, et al. Randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled trial for treatment of high grade vulval intraepithelial neoplasia with imiquimod. Abstract FC06.1. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 2005;Vol. 19(issue Suppl 2):22. [Google Scholar]

- van Seters 2008 {published data only} .Terlou A, van Seters M, Ewing PC, Aaronson NK, Gundy CM, Heijmans-Antonissen C, et al. Treatment of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia with topical imiquimod: Seven years median follow-up of a randomized clinical trial. Gynecologic Oncology. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.12.340. doi:10.1016/ j.ygyno.2010.12.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; van Seters M, van Beurden M, Kate FJ, Beckmann I, Ewing PC, Eijkemans MJ, et al. Treatment of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia with topical imiquimod. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;358(14):1465–73. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

- Iavazzo 2008 {published data only} .Iavazzo C, Pitsouni E, Athanasiou S, Falagas ME. Imiquimod for treatment of vulvar and vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 2008;101(1):3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahto 2010 {published data only} .Mahto M, Nathan M, O’Mahony C. More than a decade on: review of the use of imiquimod in lower anogenital intraepithelial neoplasia. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 2010;21(1):8–16. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2009.009309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathiesen 2008 {published data only} .Mathiesen O. Topical imiquimod can reverse vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia: A randomised, double blinded study - an answer. Gynecological Oncology. 2008;109(3):431. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melamed 1965 {published data only} .Melamed EL. Precancerous lesions of the vulva and therapeutic methods. Data from the Leningrad Municipal oncological dispensary. [Russian] Voprosy. 1965:85–9. Onkologii. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spirtos 1990 {published data only} .Spirtos NM, Smith LH, Teng NN. Prospective randomized trial of topical alpha-interferon (alpha-interferon gels) for the treatment of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia III. Gynecol Oncol. 1990;37(1):34–8. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(90)90303-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Spirtos NM, Smith LH, Teng NNH. A prospective, randomized trial of topical interferon-alpha (INF) gels for the treatment of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia III (VIN III) Gynecological Oncology. 1989;Vol. 32(issue 1):112. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(90)90303-3. Abstract 76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd 2005 {published data only} .Todd RW, Luesley DM. Medical management of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. Journal of Lower Genital Tract Diseases. 2005;9(4):206–12. doi: 10.1097/01.lgt.0000179858.21833.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Nieuwenhof 2008 {published data only} .van de Nieuwenhof HP, van der Avoort IA, Massuger LF, de Hullu JA. Letter to the Editor concerning “Topical imiquimod can reverse vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia: a randomized, double blinded study. Gynecological Oncology. 2008;109(3):430–1. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.01.020. author reply 431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to ongoing studies

- RT3VIN Clinical Trial {unpublished data only} .Fiander A. A randomised phase II multi-centre clinical trial of topical treatment in women with vulval intraepithelial neoplasia. [RT3VIN] ISRCTN34420460 [Google Scholar]

Additional references

- Andreasson 1986 .Andreasson B, Moth I, Jensen SB, Bock JE. Sexual function and somatopsychic reactions in vulvectomy-operated women and their partners. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 1986;65(1):7–10. doi: 10.3109/00016348609158221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]