Abstract

Background

Mefenamic acid is a non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drug (NSAID). It is most often used for treating pain of dysmenorrhoea in the short term (seven days or less), as well as mild to moderate pain including headache, dental pain, postoperative and postpartum pain. It is widely available in many countries worldwide.

Objectives

To assess the efficacy of single dose oral mefenamic acid in acute postoperative pain, and any associated adverse events.

Search methods

We searched Cochrane CENTRAL, MEDLINE, EMBASE and the Oxford Pain Relief Database for studies to December 2010.

Selection criteria

Single oral dose, randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trials of mefenamic acid for relief of established moderate to severe postoperative pain in adults.

Data collection and analysis

Studies were assessed for methodological quality and the data extracted by two review authors independently. Summed total pain relief (TOTPAR) or pain intensity difference (SPID) over 4 to 6 hours was used to calculate the number of participants achieving at least 50% pain relief. These derived results were used to calculate, with 95% confidence intervals, the relative benefit compared to placebo, and the number needed to treat (NNT) for one participant to experience at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours. Numbers of participants using rescue medication over specified time periods, and time to use of rescue medication, were sought as additional measures of efficacy. Information on adverse events and withdrawals was collected.

Main results

Four studies with 842 participants met the inclusion criteria; 126 participants were treated with mefenamic acid 500 mg, 67 with mefenamic acid 250 mg, 197 with placebo, and 452 with lignocaine, aspirin, zomepirac or nimesulide. Participants had pain following third molar extraction, episiotomy and orthopaedic surgery. The NNT for at least 50% pain relief over 6 hours with a single dose of mefenamic acid 500 mg compared to placebo was 4.0 (2.7 to 7.1), and the NNT to prevent use of rescue medication over 6 hours was 6.5 (3.6 to 29). There were insufficient data to analyse other doses or active comparators, or numbers of participants experiencing any adverse events. No serious adverse events or adverse event withdrawals were reported in these studies.

Authors' conclusions

Oral mefenamic acid 500 mg was effective at treating moderate to severe acute postoperative pain, based on limited data. Efficacy of other doses, and safety and tolerability could not be assessed.

Plain language summary

Single dose oral mefenamic acid for acute postoperative pain in adults

Mefenamic acid is a non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drug (NSAID) that is used as a painkiller (analgesic). Four studies involving a total of 842 participants were included in this review. Because fewer than 200 participants were treated with mefenamic acid within these four studies, results must be treated with caution. A good level of pain relief is experienced by almost half (48%) of those with moderate to severe postoperative pain after a single dose of mefenamic acid 500 mg, compared to about 20% with placebo, and fewer will need additional analgesia within 6 hours (47% versus 62%). This level of pain relief is comparable to that experienced with paracetamol 1000 mg. Adverse events could not be assessed in these studies.

Background

Acute pain occurs as a result of tissue damage either accidentally due to an injury or as a result of surgery. Acute postoperative pain is a manifestation of inflammation due to tissue injury. The management of postoperative pain and inflammation is a critical component of patient care.

This is one of a series of reviews whose aim is to present evidence for relative analgesic efficacy through indirect comparisons with placebo, in very similar trials performed in a standard manner, with very similar outcomes, and over the same duration. Such relative analgesic efficacy does not in itself determine choice of drug for any situation or patient, but guides policy‐making at the local level. The series includes well established analgesics such as paracetamol (Toms 2008), naproxen (Derry C 2009a), diclofenac (Derry P 2009), and ibuprofen (Derry C 2009b), and newer cyclo‐oxygenase‐2 selective analgesics, such as lumiracoxib (Roy 2010), celecoxib (Derry 2008), etoricoxib (Clarke 2009), and parecoxib (Lloyd 2009).

Acute pain trials

Single dose trials in acute pain are commonly short in duration, rarely lasting longer than 12 hours. The numbers of participants are small, allowing no reliable conclusions to be drawn about safety. To show that the analgesic is working it is necessary to use placebo (McQuay 2005). There are clear ethical considerations in doing this. These ethical considerations are answered by using acute pain situations where the pain is expected to go away, and by providing additional analgesia, commonly called rescue analgesia, if the pain has not diminished after about an hour. This is reasonable, because not all participants given an analgesic will have significant pain relief. Approximately 18% of participants given placebo will have significant pain relief (Moore 2006), and up to 50% may have inadequate analgesia with active medicines. The use of additional or rescue analgesia is hence important for all participants in the trials.

Clinical trials measuring the efficacy of analgesics in acute pain have been standardised over many years. Trials have to be randomised and double blind. Typically, in the first few hours or days after an operation, patients develop pain that is moderate to severe in intensity, and will then be given the test analgesic or placebo. Pain is measured using standard pain intensity scales immediately before the intervention, and then using pain intensity and pain relief scales over the following four to six hours for shorter acting drugs, and up to 12 or 24 hours for longer acting drugs. Pain relief of half the maximum possible pain relief or better (at least 50% pain relief) is typically regarded as a clinically useful outcome. For patients given rescue medication it is usual for no additional pain measurements to be made, and for all subsequent measures to be recorded as initial pain intensity or baseline (zero) pain relief (baseline observation carried forward). This process ensures that analgesia from the rescue medication is not wrongly ascribed to the test intervention. In some trials the last observation is carried forward, which gives an inflated response for the test intervention compared to placebo, but the effect has been shown to be negligible over four to six hours (Moore 2005). Patients usually remain in the hospital or clinic for at least the first six hours following the intervention, with measurements supervised, although they may then be allowed home to make their own measurements in trials of longer duration.

Knowing the relative efficacy of different analgesic drugs at various doses can be helpful. An example is the relative efficacy in the third molar extraction pain model (Barden 2004).

Mefenamic acid

Mefenamic acid is a non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drug (NSAID). It is most often used for treating pain of dysmenorrhoea in the short term (seven days or less), as well as mild to moderate pain including headache, dental pain, postoperative and postpartum pain. In the USA, where mefenamic acid is licensed only for the treatment of moderate pain in adults, it is recommended that it should not be given for longer than seven days at a time. Mefenamic acid is widely available in many European counties, as well as Australia, New Zealand, Hong Kong, India, Malaysia, Thailand, Singapore, Brazil, Chile, USA and Canada. The usual oral dose is up to 500 mg three times daily, and there are different dosing schedules for children. In 2009 in England almost 403,00 prescriptions were issued in primary care. This compares with 2.4 million prescriptions for naproxen and 4.7 million prescriptions for ibuprofen in the same period (PACT 2010).

Clinicians prescribe NSAIDs on a routine basis for a range of mild to moderate pain. NSAIDs are the most commonly prescribed analgesic medications worldwide, and their efficacy for treating acute pain has been well demonstrated (Moore 2003). They reversibly inhibit cyclooxygenase (prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase), the enzyme mediating production of prostaglandins (PGs) and thromboxane A2 (Fitzgerald 2001). PGs mediate a variety of physiological functions such as maintenance of the gastric mucosal barrier, regulation of renal blood flow, and regulation of endothelial tone. They also play an important role in inflammatory and nociceptive processes. However, relatively little is known about the mechanism of action of this class of compounds aside from their ability to inhibit cyclooxygenase‐dependent prostanoid formation (Hawkey 1999).

Mefenamic acid has a large number of trade names (Algifemin, Beafemic, Clinstan, Conamic, Contraflam, Coslan, Dolcin, Dysman, Dyspen, Dysmen‐500, Fenamin, Flipal, Femen, Fenamin, Gandin, Hamitan, Hostan, Lysalgo, Manic, Medicap, Mefa, Mefac, Mefacap, Mefalgic, Mephadolor, Mefamic, Mefe‐basan, Mefen, Mefenacide, Mefenan, Mefenix, Mefic, Mefin, Meflam, Melur, Namic, Namifen, Napan, Opustan, Painnox, Panamic, Parkemed, Pefamic, Pinalgesic, Ponac, Ponalgic, Pondnadysmen, Pongesic, Ponlar, Ponmel, Ponnesia, Ponstan, Ponstel, Ponstil, Ponstyl, Pontacid, Pontalon, Pontin, Prostan, Pynamic, Sefmic, Sicadol, Spiralgin, Tanston, Templadol, Templadol). Mefenamic acid, an anthranilic acid derivative, is a member of the fenamate group of NSAIDs. It exhibits anti‐inflammatory, analgesic, and antipyretic activities. Similar to other NSAIDs, mefenamic acid inhibits prostaglandin synthetase. It is absorbed rapidly after oral administration, and has a short half life of about two hours.

We could find no useful reviews of the pharmacology of mefenamic acid, or systematic reviews of its use in acute postoperative pain, although in common with other NSAIDs there is some evidence that it reduces pain associated with dysmenorrhoea (Majoribanks 2010) and intrauterine devices (Grimes 2006). This review looks at its efficacy in the setting of acute postoperative pain.

Objectives

To assess the efficacy and adverse effects of single dose oral mefenamic acid for acute postoperative pain using methods that permit comparison with other analgesics evaluated in standardised trials using almost identical methods and outcomes.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised, double blind trials of single dose oral mefenamic acid compared with placebo for the treatment of moderate to severe postoperative pain in adults, with at least ten participants allocated to each treatment group. Multiple dose studies were included if appropriate data from the first dose were available. Cross‐over studies were included if data from the first arm were presented separately.

We excluded the following:

review articles, case reports, and clinical observations;

studies of experimental pain;

studies where pain relief is assessed only by clinicians, nurses or carers (i.e., not patient‐reported);

studies of less than four hours duration or studies that fail to present data over four to six hours post‐dose.

For postpartum pain, we included studies if the pain investigated was due to episiotomy or Caesarean section, irrespective of the presence of uterine cramps, but excluded studies investigating pain due to uterine cramps alone.

Types of participants

We included studies of adult participants (>15 years) with established postoperative pain of moderate to severe intensity following day surgery or in‐patient surgery. For studies using a visual analogue scale (VAS), pain of at least moderate intensity was equated to greater than 30 mm (Collins 1997).

Types of interventions

Mefanamic acid or matched placebo administered as a single oral dose for postoperative pain.

Types of outcome measures

We collected data on the following outcomes if available:

participant characteristics;

patient reported pain at baseline (physician, nurse or carer reported pain will not be included in the analysis);

patient reported pain relief expressed at least hourly over four to six hours using validated pain scales (pain intensity and pain relief in the form of VAS or categorical scales, or both);

patient global assessment of efficacy (PGE), using a standard categorical scale;

time to use of rescue medication;

number of participants using rescue medication;

number of participants with one or more adverse events;

number of participants with serious adverse events;

number of withdrawals (all cause, adverse event).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following electronic databases:

Cochrane CENTRAL (December 2010);

MEDLINE via Ovid (December 2010);

EMBASE via Ovid (December 2010);

Oxford Pain Relief Database (Jadad 1996a).

Please see Appendix 1 for the MEDLINE search strategy, Appendix 2 for the EMBASE search strategy and Appendix 3 for the Cochrane CENTRAL search strategy.

Language

No language restriction was applied to searches.

Searching other resources

Additional studies were sought from the reference lists of retrieved articles and reviews.

Unpublished studies

We did not search, or contact any manufacturing or distributing pharmaceutical company, for unpublished trial data.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently assessed and agreed the search results for studies that might be included in the review.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors extracted data and recorded it on a standard data extraction form. One author entered data, and another checked it in RevMan 5.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed the included studies for methodological quality using a five‐point scale (Jadad 1996b) that considers randomisation, blinding, and study withdrawals and dropouts.

The scale is used as follows:

Is the study randomised? If yes, give one point.

Is the randomisation procedure reported and is it appropriate? If yes, add one point; if no, deduct one point.

Is the study double‐blind? If yes, add one point.

Is the double‐blind method reported and is it appropriate? If yes, add one point; if no, deduct one point.

Are the reasons for patient withdrawals and dropouts described? If yes, add one point.

The scores for each study are reported in the 'Characteristics of included studies' table.

A Risk of bias table was completed using assessments of randomisation, allocation concealment and blinding.

Measures of treatment effect

Relative risk (or 'risk ratio', RR) was used to establish statistical difference. Numbers needed to treat (NNT) and pooled percentages were used as absolute measures of benefit or harm.

The following terms are used to describe adverse outcomes in terms of harm or prevention of harm:

When significantly fewer adverse outcomes occur with mefenamic acid than with control (placebo or active) we use the term the number needed to treat to prevent one event (NNTp).

When significantly more adverse outcomes occur with mefenamic acid compared with control (placebo or active) we use the term the number needed to harm or cause one event (NNH).

Unit of analysis issues

We accepted randomisation to individual participant only.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Heterogeneity of studies was assessed visually (L'Abbe 1987).

Assessment of reporting biases

We assessed publication bias by examining the number of participants in studies with zero effect (relative risk of 1.0) needed for the point estimate of the NNT to increase beyond a clinically useful level. In this case, we specified a clinically useful level as an NNT of eight or less (Moore 2008).

Data synthesis

We calculated effect sizes and combined data for analysis only for comparisons and outcomes where there were at least two studies and 200 participants (Moore 1998).

For each study, the mean TOTPAR, SPID, VAS TOTPAR or VAS SPID (Appendix 4) values for active and placebo were converted to %maxTOTPAR or %maxSPID by division into the calculated maximum value (Cooper 1991). The proportion of participants in each treatment group who achieved at least 50%maxTOTPAR were calculated using verified equations (Moore 1996; Moore 1997a; Moore 1997b). These proportions were then converted into the number of participants achieving at least 50%maxTOTPAR by multiplying by the total number of participants in the treatment group. Information on the number of participants with at least 50%maxTOTPAR for active and placebo were used to calculate relative benefit, and number needed to treat to benefit (NNT).

Pain measures accepted for the calculation of TOTPAR or SPID were:

five‐point categorical pain relief (PR) scales with comparable wording to "none, slight, moderate, good or complete";

four‐point categorical pain intensity (PI) scales with comparable wording to "none, mild, moderate, severe";

VAS for pain relief;

VAS for pain intensity.

If none of these measures were available, the number of participants reporting "very good or excellent" on a five‐point categorical global scale with the wording "poor, fair, good, very good, excellent" would be used for the number of participants achieving at least 50% pain relief (Collins 2001).

The number of participants reporting treatment‐emergent adverse effects was extracted for each treatment group.

Relative benefit or risk estimates were calculated with 95% confidence intervals (CI) using a fixed‐effect model (Morris 1995). NNT and number needed to treat to harm (NNH) and 95% CI were calculated using the pooled number of events by the method of Cook and Sackett (Cook 1995). A statistically significant difference from control was assumed when the 95% CI of the relative benefit or risk did not include the number one.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to analyse separately different doses of mefenamic acid.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned sensitivity analyses to determine the effect of the presenting condition (pain model), and low versus high (two versus three or more) quality studies. A minimum of two studies and 200 participants had to be available in any sensitivity analysis (Moore 1998). The z test (Tramer 1997) would be used to determine if there was a significant difference between NNTs for different groups in the sensitivity analyses when the 95% CIs do not overlap.

Results

Description of studies

Included studies

The four included studies, reporting on a total of 842 participants, all examined the effectiveness of mefenamic acid on pain in participants following a surgical procedure.

Harrison 1987 recruited 103 participants with moderate to severe pain following episiotomy, with 25 receiving 500 mg mefenamic acid, 26 receiving a single spray of alcoholic lignocaine (5%), 26 receiving a single spray of aqueous lignocaine (5%), and 26 receiving placebo. Study duration was 6 hours.

Or 1988 recruited 120 participants with severe pain following surgical removal of impacted third molars, although 12 had major protocol violations and so were excluded from the analyses. There were therefore 27 in each group of 250 mg mefenamic acid, 650 mg aspirin, 250 mg mefenamic acid with 650 mg aspirin, and placebo. Study duration was 4 hours.

Pujalte 1982 recruited 200 participants with moderate to severe pain following orthopaedic surgery, with 40 in each group of 250 mg mefenamic acid, 25 mg zomepirac, 50 mg zomepirac, 100 mg zomepirac, and placebo. Study duration was 4 hours.

Ragot 1994 recruited 431 participants with moderate to severe pain following surgical removal of impacted third molars, with 101 receiving 500 mg mefenamic acid, 112 receiving 100 mg nimesulide, 114 receiving 200 mg nimesulide, and 104 receiving placebo tablets. Study duration was 6 hours.

Excluded studies

Ten studies were excluded after reading the full reports (Fassolt 1974; Hackl 1967; Lee 2007; Mariani 1966; Mohing 1981; Ohnishi 1983; Ragot 1991; Rowe 1980; Rowe 1981; Vaidya 1974). Reasons for exclusion are in the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table.

Risk of bias in included studies

Studies were assessed for methodological bias using the three‐point Oxford Quality Score (Jadad 1996b). All studies were randomised and double blind. One study (Ragot 1994) scored 5/5, two (Harrison 1987; Or 1988) scored 4/5 and one (Pujalte 1982) scored 3/5. Points were lost for not giving adequate details of the methods of randomisation and, in one case (Pujalte 1982), blinding. Withdrawals and exclusions were reported, and were considered unlikely to influence the results.

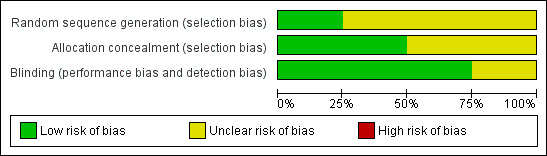

The Risk of bias table assessing randomisation, allocation concealment and blinding, indicates that no studies were at high risk of bias (Figure 1).

1.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Effects of interventions

All studies compared mefenamic acid with placebo, but only for the 500 mg dose were there sufficient data (≥2 studies, ≥200 participants) for statistical analysis. No two studies compared mefenamic acid with the same active comparator, so no statistical analysis was possible.

Number of participants achieving at least 50% pain relief

Mefenamic acid 250 mg versus placebo

Two studies compared mefenamic acid 250 mg with placebo (Or 1988; Pujalte 1982); 38/67 participants experienced at least 50% pain relief over four to six hours with mefenamic acid, and 24/67 did so with placebo. There were too few data for statistical analysis.

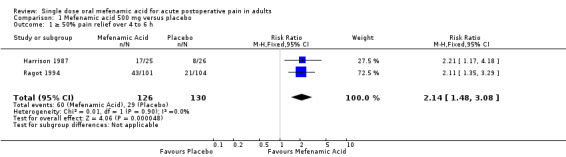

Mefenamic acid 500 mg versus placebo

Two studies compared mefenamic acid 500 mg with placebo (Harrison 1987; Ragot 1994).

The proportion of participants experiencing at least 50% pain relief over 6 hours with mefenamic acid 500 mg was 48% (60/126);

The proportion of participants experiencing at least 50% pain relief over 6 hours with placebo was 22% (29/130);

The relative benefit of treatment compared with placebo was 2.1 (1.5 to 3.1);

The NNT for at least 50% pain relief over 6 hours for mefenamic acid 500 mg compared with placebo was 4.0 (2.7 to 7.1) (Analysis 1.1, Figure 2).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Mefenamic acid 500 mg versus placebo, Outcome 1 ≥ 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 h.

2.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Mefenamic acid 500 mg versus placebo, outcome: 1.1 ≥50% pain relief over 4 to 6 h.

Assessment of potential publication bias

Studies with an additional 256 participants, demonstrating no difference between mefenamic acid 500 mg and placebo, would be needed to give an NNT of eight, which we have specified as the limit of clinical usefulness.

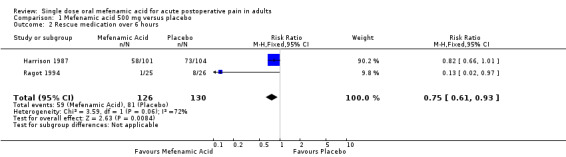

Use of rescue medication

Two studies comparing mefenamic acid 500 mg with placebo reported numbers of patients requiring rescue medication within 6 hours (Harrison 1987; Ragot 1994).

The proportion of participants requiring rescue medication within 6 hours with mefenamic acid 500 mg was 47% (59/126);

The proportion of participants requiring rescue medication within 6 hours with placebo was 62% (81/130);

The relative benefit of treatment compared with placebo was 0.75 (0.60 to 0.94), giving an NNTp of 6.5 (3.6 to 29) (Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Mefenamic acid 500 mg versus placebo, Outcome 2 Rescue medication over 6 hours.

It is noteworthy that the event rates in the two studies differed widely and the analysis was dominated by the larger study.

Median time to rescue medication was not reported in any study.

Adverse events

Adverse events were recorded by means of questionnaires and verbal questioning during the trial. There were no serious adverse events reported for mefenamic acid or placebo, and no participants withdrew from any of the trials due to adverse effects. Two studies (Pujalte 1982; Ragot 1994) did not provide adequate information to determine the number of participants experiencing adverse events in each group, and therefore cannot be included in the data analysis.

Combining data from the remaining two studies (Harrison 1987; Or 1988), 7/52 (13%) of participants treated with mefenamic acid (250 mg or 500 mg) reported adverse events, compared with 3/53 (5.7%) of participants treated with placebo. There were too few data for statistical analysis.

Withdrawals

All studies reported on withdrawals and exclusions. Two studies (Or 1988; Ragot 1994) reported exclusions due to failure to take medication or protocol violations; these amounted to < 10%, appear to have been evenly distributed between mefenamic acid and placebo, and are unlikely to have influenced the results. There were no withdrawals due to adverse events.

Discussion

Summary of main results

This review examined the efficacy of mefenamic acid, an NSAID, in providing postoperative pain relief. Four studies were identified as fulfilling the inclusion criteria. Participants were experiencing moderate to severe pain following dental surgery in two studies (Or 1988; Ragot 1994), following episiotomy in one (Harrison 1987), and following orthopaedic surgery in one (Pujalte 1982). For mefenamic acid 500 mg the relative benefit compared to placebo was 2.1, and the NNT was 4.0 (2.7 to 7.1) for at least 50% pain relief over six hours. Fewer participants needed rescue medication over the first 6 hours with mefenamic acid than with placebo. There were insufficient data for analysis of different doses of mefenamic acid compared with placebo, or to compare mefenamic acid with any active comparator. No serious adverse events or adverse event withdrawals were reported in any of the studies.

No study reported median time to use of rescue medication, and the two that reported numbers of participants needing rescue medication within six hours gave widely differing results, so it is difficult to draw any conclusion on duration of action from these data.

Indirect comparisons of NNTs for at least 50% pain relief over four to six hours in reviews of other analgesics using identical methods indicate that mefenamic acid 500 mg is less effective than etoricoxib 120 mg (NNT 1.9 (1.7 to 2.1) Clarke 2009), probably less effective than commonly used analgesics such as ibuprofen 400 mg (2.5 (2.4 to 2.6) Derry C 2009b), naproxen 500 mg (2.7 (2.3 to 3.2) Derry C 2009a) or diclofenac 50 mg (2.7 (2.4 to 3.0) Derry P 2009), and of similar efficacy to paracetamol 1000 mg (3.6 (3.4 to 4.0) Toms 2008).

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The most important limitation of this review is the small numbers of included studies and participants in each treatment arm. This restricted the analyses to a single dose of mefenamic acid compared to placebo. Furthermore, the numbers in those analyses were small resulting in wide confidence intervals for the point estimates for efficacy, and with consequent uncertainty over the true size of the treatment effect (Moore 1998).

The four studies used different models to investigate pain relief: two studied pain relief following dental surgery, one used pain following episiotomy and one used pain following orthopaedic surgery. The use of different procedures is a potential confounding factor, but it does demonstrate the effectiveness of mefenamic acid as an analgesic following a range of surgical procedures, in addition to its better known clinical use in dysmenorrhoea (Grimes 2006; Lethaby 2007; Oehler 2003).

All studies reported pain relief and pain intensity difference, but data on other outcomes, such as participants experiencing any adverse event or needing rescue medication within six hours, and time to use of rescue medication were inconsistently reported, which limited analysis.

No serious adverse events were reported by the included studies, but single dose studies are of limited use for determining the safety and tolerability of analgesics; they are underpowered to do so, and reporting of events is frequently inconsistent, making pooling of data impossible.

Quality of the evidence

The methodological quality of the evidence was assessed using to the Oxford Quality Scoring System, based on whether the study was randomised, double‐blinded and if withdrawals were accounted for (Jadad 1996b). All scored ≥3/5 indicating that they are relatively free of bias (Jadad 1996b). Points were lost for failure to provide details of the method of randomisation and allocation concealment, and also details of blinding by one study (Pujalte 1982); these details were frequently not reported in older studies.

Only one study (Ragot 1994) was explicit in its approach to handling data after use of rescue medication: the scores for pain measurement after rescue medication were set equal to the last score prior to administration (last observation carried forward). Harrison 1987 gave the numbers of participants requiring rescue medication without detailing how the data for these participants were subsequently treated. Pujalte 1982 implied that rescue medication may have been available after 4 hours but gave no further information, and Or 1988 did not mention rescue medication at all. Although baseline observation carried forward following use of rescue medication, or other missing data, gives a more conservative estimate of efficacy, it has been shown that in acute pain over four to six hours the imputation method makes little difference (Moore 2005).

No competing interests are declared in any of the studies.

Potential biases in the review process

Studies were identified from a comprehensive search of published papers, and all stages of the review process were carried out in duplicate, with data entry cross‐checked, according to established methods. However, the fact that only 256 participants would need to be included in zero‐effect unpublished trials must mean that the result should be interpreted with caution, because that level of unpublished data is possible. Given that mefenamic acid has "proven" utility in other painful conditions, such as dysmenorrhoea (Grimes 2006) and menstrual migraine (Pringsheim 2008), it is unlikely that it has no analgesic effects, but rather the size of the effect demonstrated here may not be robust.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

We are not aware of any other reviews of mefenamic acid in acute postoperative pain.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Mefenamic acid 500 mg is likely to be an effective analgesic, but there is insufficient evidence from this limited data set to give a reliable estimate of the size of its effect. No serious adverse events were reported in any of the studies, though numbers were too small to exclude rare but serious harm.

Implications for research.

Given the large number of available drugs of this and similar classes to treat postoperative pain, there is no urgent research agenda. More studies could more accurately determine efficacy, but are unlikely to be performed because of well known alternatives. Such studies would need to improve reporting of outcomes other than pain relief and pain intensity difference, such as adverse events and time to remedication.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 29 May 2019 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

| 11 October 2017 | Review declared as stable | No new studies likely to change the conclusions are expected. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 2009 Review first published: Issue 3, 2011

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 3 August 2016 | Review declared as stable | See Published notes. |

| 15 September 2011 | Review declared as stable | The authors are confident that this review will not need an update until at least 2015. |

Notes

A restricted search in August 2016 did not identify any potentially relevant studies likely to change the conclusions. Therefore, this review has now been stabilised following discussion with the authors and editors. If appropriate, we will update the review if new evidence likely to change the conclusions is published, or if standards change substantially which necessitate major revisions.

Appendices

Appendix 1. MEDLINE search strategy (via OVID)

Mefenamic acid/

(Algifemin or Beafemic or Clinstan or Conamic or Contraflam or Coslan or Dolcin or Dysman or Dyspen or Dysmen‐500 or Fenamin or Flipal or Femen or Fenamin or Gandin or Hamitan or Hostan or Lysalgo or Manic or Medicap or Mefa or Mefac or Mefacap or Mefalgic or Mephadolor or Mefamic or Mefe‐basan or Mefen or Mefenacide or Mefenan or Mefenix or Mefic or Mefin or Meflam or Melur or Namic or Namifen or Napan or Opustan or Painnox or Panamic or Parkemed or Pefamic or Pinalgesic or Ponac or Ponalgic, orPondnadysmen or Pongesic or Ponlar or Ponmel or Ponnesia or Ponstan or Ponstel or Ponstil or Ponstyl or Pontacid or Pontalon or Pontin or Prostan or Pynamic or Sefmic or Sicadol or Spiralgin or Tanston or Templadol or Templadol).mp.

1 OR 2

Pain, postoperative.sh

((postoperative adj4 pain*) or (post‐operative adj4 pain*) or post‐operative‐pain* or (post* NEAR pain*) or (postoperative adj4 analgesi*) or (post‐operative adj4 analgesi*) or ("post‐operative analgesi*")).mp.

((post‐surgical adj4 pain*) or ("post surgical" adj4 pain*) or (post‐surgery adj4 pain*)).mp.

(("pain‐relief after surg*") or ("pain following surg*") or ("pain control after")).mp.

(("post surg*" or post‐surg*) AND (pain* or discomfort)).mp.

((pain* adj4 "after surg*") or (pain* adj4 "after operat*") or (pain* adj4 "follow* operat*") or (pain* adj4 "follow* surg*")).mp.

((analgesi* adj4 "after surg*") or (analgesi* adj4 "after operat*") or (analgesi* adj4 "follow* operat*") or (analgesi* adj4 "follow$ surg*")).mp.

OR/4‐10

randomized controlled trial.pt.

controlled clinical trial.pt.

randomized.ab.

placebo.ab.

drug therapy.fs.

randomly.ab.

trial.ab.

groups.ab.

OR/12‐19

3 AND 11 AND 20

Appendix 2. Search strategy for EMBASE (via Ovid)

Mefenamic acid/

(Algifemin or Beafemic or Clinstan or Conamic or Contraflam or Coslan or Dolcin or Dysman or Dyspen or Dysmen‐500 or Fenamin or Flipal or Femen or Fenamin or Gandin or Hamitan or Hostan or Lysalgo or Manic or Medicap or Mefa or Mefac or Mefacap or Mefalgic or Mephadolor or Mefamic or Mefe‐basan or Mefen or Mefenacide or Mefenan or Mefenix or Mefic or Mefin or Meflam or Melur or Namic or Namifen or Napan or Opustan or Painnox or Panamic or Parkemed or Pefamic or Pinalgesic or Ponac or Ponalgic or Pondnadysmen or Pongesic or Ponlar or Ponmel or Ponnesia or Ponstan or Ponstel or Ponstil or Ponstyl or Pontacid or Pontalon or Pontin or Prostan or Pynamic or Sefmic or Sicadol or Spiralgin or Tanston or Templadol or Templadol).mp.

OR/1‐2

Postoperative pain.sh.

((postoperative adj4 pain*) or (post‐operative adj4 pain*) or post‐operative‐pain* or (post* NEAR pain*) or (postoperative adj4 analgesi*) or (post‐operative adj4 analgesi*) or ("post‐operative analgesi*")).mp.

((post‐surgical adj4 pain*) or ("post surgical" adj4 pain*) or (post‐surgery adj4 pain*)).mp.

(("pain‐relief after surg*") or ("pain following surg*") or ("pain control after")).mp.

(("post surg*" or post‐surg*) AND (pain* or discomfort)).mp.

((pain* adj4 "after surg*") or (pain* adj4 "after operat*") or (pain* adj4 "follow* operat*") or (pain* adj4 "follow* surg*")).mp.

((analgesi* adj4 "after surg*") or (analgesi* adj4 "after operat*") or (analgesi* adj4 "follow* operat*") or (analgesi* adj4 "follow* surg*")).mp.

OR/4‐10

Clinical trials.sh.

Controlled clinical trials.sh.

Randomized controlled trial.sh.

Double‐blind procedure.sh.

(clin* adj25 trial*).ab.

((doubl* or trebl* or tripl*) adj25 (blind* or mask*)).ab.

placebo*.ab.

random*.ab.

OR/12‐19

3 AND 11 AND 20

Appendix 3. Search strategy for Cochrane CENTRAL

(Algifemin or Beafemic or Clinstan or Conamic or Contraflam or Coslan or Dolcin or Dysman or Dyspen or Dysmen‐500 or Fenamin or Flipal or Femen or Fenamin or Gandin or Hamitan or Hostan or Lysalgo or Manic or Medicap or Mefa or Mefac or Mefacap or Mefalgic or Mephadolor or Mefamic or Mefe‐basan or Mefen or Mefenacide or Mefenan or Mefenix or Mefic or Mefin or Meflam or Melur or Namic or Namifen or Napan or Opustan or Painnox or Panamic or Parkemed or Pefamic or Pinalgesic or Ponac or Ponalgic or Pondnadysmen or Pongesic or Ponlar or Ponmel or Ponnesia or Ponstan or Ponstel or Ponstil or Ponstyl or Pontacid or Pontalon or Pontin or Prostan or Pynamic or Sefmic or Sicadol or Spiralgin or Tanston or Templadol or Templadol):ti,ab,kw

MESH descriptor Pain, Postoperative

((postoperative near4 pain*) or (post‐operative near4 pain$) or post‐operative‐pain* or (post* near pain*) or (postoperative near4 analgesi*) or (post‐operative near4 analgesi*) or ("post‐operative analgesi*")):ti,ab,kw

((post‐surgical near4 pain*) or ("post surgical" near4 pain*) or (post‐surgery near4 pain*)):ti,ab,kw

(("pain‐relief after surg*") or ("pain following surg*") or ("pain control after")):ti,ab,kw

(("post surg*" or post‐surg*) AND (pain* or discomfort)):ti,ab,kw

((pain* near4 "after surg*") or (pain* near4 "after operat*") or (pain* near4 "follow* operat*") or (pain* near4 "follow* surg*")):ti,ab,kw

((analgesi* near4 "after surg*") or (analgesi* near4 "after operat*") or (analgesi* near4 "follow* operat*") or (analgesi* near4 "follow* surg*")):ti,ab,kw

OR/2‐8

1 AND 9

Limit 10 to Clinical Trials (CENTRAL)

Appendix 4. Glossary

Categorical rating scale:

The commonest is the five category scale (none, slight, moderate, good or lots, and complete). For analysis numbers are given to the verbal categories (for pain intensity, none = 0, mild = 1, moderate = 2 and severe = 3, and for relief none = 0, slight = 1, moderate = 2, good or lots = 3 and complete = 4). Data from different subjects is then combined to produce means (rarely medians) and measures of dispersion (usually standard errors of means). The validity of converting categories into numerical scores was checked by comparison with concurrent visual analogue scale measurements. Good correlation was found, especially between pain relief scales using cross‐modality matching techniques. Results are usually reported as continuous data, mean or median pain relief or intensity. Few studies present results as discrete data, giving the number of participants who report a certain level of pain intensity or relief at any given assessment point. The main advantages of the categorical scales are that they are quick and simple. The small number of descriptors may force the scorer to choose a particular category when none describes the pain satisfactorily.

VAS:

Visual analogue scale: lines with left end labelled "no relief of pain" and right end labelled "complete relief of pain", seem to overcome this limitation. Patients mark the line at the point which corresponds to their pain. The scores are obtained by measuring the distance between the no relief end and the patient's mark, usually in millimetres. The main advantages of VAS are that they are simple and quick to score, avoid imprecise descriptive terms and provide many points from which to choose. More concentration and coordination are needed, which can be difficult post‐operatively or with neurological disorders.

TOTPAR:

Total pain relief (TOTPAR) is calculated as the sum of pain relief scores over a period of time. If a patient had complete pain relief immediately after taking an analgesic, and maintained that level of pain relief for six hours, they would have a six‐hour TOTPAR of the maximum of 24. Differences between pain relief values at the start and end of a measurement period are dealt with by the composite trapezoidal rule. This is a simple method that approximately calculates the definite integral of the area under the pain relief curve by calculating the sum of the areas of several trapezoids that together closely approximate to the area under the curve.

SPID:

Summed pain intensity difference (SPID) is calculated as the sum of the differences between the pain scores over a period of time. Differences between pain intensity values at the start and end of a measurement period are dealt with by the trapezoidal rule.

VAS TOTPAR and VAS SPID are visual analogue versions of TOTPAR and SPID.

See "Measuring pain" in Bandolier's Little Book of Pain, Oxford University Press, Oxford. 2003; pp 7‐13 (Moore 2003).

Appendix 5. Summary of efficacy outcomes in individual studies

| Analgesia | Rescue medication | |||||

| Study ID | Treatment | PI or PR | Number with 50% PR | PGE: very good or excellent | Median time to use (h) | Number using |

| Harrison 1987 | (1) Mefenamic acid 500mg, n = 25 (2) Single spray of alcoholic lignocaine (5%), n = 26 (3) Single spray of aqueous lignocaine (5%), n = 26 (4) Placebo, n = 26 |

SPID 6: (1) 7.89 (4) 3.62 |

(1) 17/25 (4) 8/26 |

No usable data | No data | At 6 h: (1) 1/25 (4) 8/26 |

| Or 1988 | (1) Mefenamic acid 250 mg, n = 27 (2) Aspirin 650 mg, n = 27 (3) Aspirin 650 mg plus Mefenamic acid 250 mg, n = 27 (4) Placebo, n = 27 |

TOTPAR 4: (1) 8.6 (4) 5.1 |

(1) 16/27 (4) 8/27 |

No data | No data | No data |

| Pujalte 1982 | (1) Mefenamic acid 250 mg, n = 40 (2) Zomepirac 25 mg, n = 40 (3) Zomperirac 50 mg, n = 40 (4) Zomepirac 100 mg, n = 40 (5) Placebo, n = 40 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 12.13 (5) 9.40 |

(1) 22/40 (5) 16/40 |

No usable data | No data | No data |

| Ragot 1994 | (1) Mefenamic acid 500 mg, n = 101 (2) Nimesulide 100 mg, n = 112 (3) Nimesulide 200 mg, n = 114 (4) Placebo, n = 104 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 9.75 (4) 5.73 |

(1) 43/101 (4) 21/104 |

No usable data | No data | At 6 h: (1) 58/101 (4) 73/104 |

Appendix 6. Summary of adverse events, withdrawals and exclusions

| Adverse events | Withdrawals | ||||

| Study ID | Treatment | Any | Serious | Adverse event | Other/Exclusions |

| Harrison 1987 | (1) Mefenamic acid 500mg, n = 25 (2) Single spray of alcoholic lignocaine (5%), n = 26 (3) Single spray of aqueous lignocaine (5%), n = 26 (4) Placebo, n = 26 |

(1) 3/25 (4) 0/26 All events were stinging associated with spray |

None | None | None |

| Or 1988 | (1) Mefenamic acid 250 mg, n = 27 (2) Aspirin 650 mg, n = 27 (3) Aspirin 650 mg plus Mefenamic acid 250 mg, n = 27 (4) Placebo, n = 27 |

(1) 4/27 (4) 3/27 All mild and transient |

None | None | Exclusions: 12 due to incorrect protocol (8), confounding medication (4) |

| Pujalte 1982 | (1) Mefenamic acid 250 mg, n = 40 (2) Zomepirac 25 mg, n = 40 (3) Zomperirac 50 mg, n = 40 (4) Zomepirac 100 mg, n = 40 (5) Placebo, n = 40 |

"No unusual or unexpected side effects" | None | None | None |

| Ragot 1994 | (1) Mefenamic acid 500 mg, n = 101 (2) Nimesulide 100 mg, n = 112 (3) Nimesulide 200 mg, n = 114 (4) Placebo, n = 104 |

I participant in (3) had severe migraine and moderate fever the next day ‐ judged unrelated | None | None | Exclusions: 5.5% of randomised participants did not take study medication or were lost to follow‐up |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Mefenamic acid 500 mg versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 ≥ 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 h | 2 | 256 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.14 [1.48, 3.08] |

| 2 Rescue medication over 6 hours | 2 | 256 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.75 [0.61, 0.93] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Harrison 1987.

| Methods | RCT, DB, DD, placebo‐controlled parallel‐group study, single oral dose after moderate‐severe pain, 6 hour study. | |

| Participants | Perineal pain post‐episiotomy N = 103 All F Mean age 22 years |

|

| Interventions | Mefenamic acid 500mg, n = 25 Single spray of alcoholic lignocaine (5%), n = 26 Single spray of aqueous lignocaine (5%), n = 26 Placebo, n = 26 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: standard 4 point scale PR: standard 5 point scale PGE: non‐standard 4 point scale Numbers using rescue medication Adverse events: any, serious Withdrawals: all cause, adverse event |

|

| Notes | Pain relief assessed only at 10 minutes Qxford Quality Score = 4 (R1, DB2, W1) |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "allocated at random". No further description |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Identical numbered canisters |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Placebo tablet and placebo (distilled water) spray, double‐dummy method |

Or 1988.

| Methods | RCT, DB, placebo‐controlled parallel‐group study, single oral dose after onset of severe pain, 4 hour study | |

| Participants | Postoperative dental surgery ‐ third molar tooth extraction. N = 108 M = 54, F = 54 Mean age 26 years |

|

| Interventions | Mefenamic acid 250 mg, n = 27 Aspirin 650 mg, n = 27 Aspirin 650 mg plus Mefenamic acid 250 mg, n = 27 Placebo, n = 27 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: VAS 0‐100 PR: standard 5 point scale Adverse events: any, serious Withdrawals: all cause, adverse event |

|

| Notes | Qxford Quality Score = 4 (R1, DB2, W1) | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "Randomly allocated". No further description |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No description |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Identical two‐capsule doses |

Pujalte 1982.

| Methods | RCT, DB, placebo‐controlled parallel‐group study, single oral dose after onset of moderate‐severe pain, 6 hour study | |

| Participants | Orthopaedic surgery N = 200 M = 140, F = 60 Mean age 34 years |

|

| Interventions | Mefenamic acid 250 mg, n = 40 Zomepirac 25 mg, n = 40 Zomperirac 50 mg, n = 40 Zomepirac 100 mg, n = 40 Placebo, n = 40 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: standard 4 point scale PR: standard 5 point scale PGE: standard 5 point scale Adverse events: any, serious Withdrawals: all cause, adverse event |

|

| Notes | Qxford Quality Score = 3 (R1, DB1, W1) | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "assigned randomly". No further description |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No description |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | "double‐blind". No further description |

Ragot 1994.

| Methods | RCT, DB, DD, placebo‐controlled parallel‐group study, single oral dose after onset of moderate‐severe pain, 6 hour study | |

| Participants | Postoperative dental surgery ‐ third molar tooth extraction. N = 431 M = 190, F = 241 Age 14‐61 years Mean age 24 years |

|

| Interventions | Mefenamic acid 500 mg, n = 101 Nimesulide 100 mg, n = 112 Nimesulide 200 mg, n = 114 Placebo, n = 104 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: standard 4 point scale PR: standard 5 point scale PGE: non‐standard 4 point scale Number using rescue medication Adverse events: any, serious Withdrawals: all cause, adverse event |

|

| Notes | Qxford Quality Score = 5 (R2, DB2, W1) | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | A computer‐based pseudo random number generator |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Remote allocation implied |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Each active treatment indistinguishable from its placebo, double‐dummy method |

DB ‐ double blind; DD ‐ double dummy; F ‐ female; M ‐ male; N ‐ total number in study; n ‐ number in treatment arm; PGE ‐ patient global assessment; PI ‐ pain intensity; PR ‐ pain relief; R ‐ randomised; RCT ‐ randomised controlled trial; VAS ‐ visual analogue scale; W ‐ withdrawals

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Fassolt 1974 | Rectal administration of analgesia |

| Hackl 1967 | No single dose data |

| Lee 2007 | Not single dose, no placebo arm |

| Mariani 1966 | No placebo arm |

| Mohing 1981 | No placebo arm |

| Ohnishi 1983 | No representative placebo group, no placebo data presented |

| Ragot 1991 | No placebo arm |

| Rowe 1980 | Analgesic administration is pre‐emptive to surgical intervention |

| Rowe 1981 | No 4 to 6 h data |

| Vaidya 1974 | Not moderate to severe pain, no 4 to 6 h data |

Contributions of authors

SD and RAM wrote the protocol. RM and SD performed searching, data extraction, and analysis, including assessment of study quality. RAM helped with analysis and acted as arbitrator. All authors contributed to writing the final review. It is unlikely that an update of this review will be required in the near future.

Sources of support

Internal sources

Oxford Pain Research Funds, UK.

External sources

NHS Cochrane Collaboration Grant, UK.

NIHR Biomedical Research Centre Programme, UK.

Declarations of interest

SD and RAM have received research support from charities, government and industry sources at various times. RAM has consulted for various pharmaceutical companies and has received lecture fees from pharmaceutical companies related to analgesics and other healthcare interventions. Support for this review came from Oxford Pain Research, the NHS Cochrane Collaboration Programme Grant Scheme, and NIHR Biomedical Research Centre Programme.

Stable (no update expected for reasons given in 'What's new')

References

References to studies included in this review

Harrison 1987 {published data only}

- Harrison RF, Brennan M. Comparison of two formulations of lignocaine spray with mefenamic acid in the relief of post‐episiotomy pain: a placebo‐controlled study. Current Medical Research and Opinion 1987;10(6):375‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Or 1988 {published data only}

- Or S, Bozkurt A. Analgesic effect of aspirin, mefenamic acid and their combination in post‐operative oral surgery pain. Journal of International Medical Research 1988;16(3):167‐72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pujalte 1982 {published data only}

- Pujalte J, Valdez E, Regalado De La Paz N, Makalinaw F. Postoperative orthopedic pain: Zomepirac sodium, mefenamic acid, and placebo. Current Therapeutic Research ‐ Clinical and Experimental 1982;31(2):119‐28. [Google Scholar]

- Valdez EV. Treatment of postoperative pain. Zomepirac, mefenamic acid and placebo [Behandlung postoperativer Schmerzen. Zomepirac, Mefenaminsaure und Plazebo]. Munchener Medizinische Wochenschrift 1982;124(40):869‐70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ragot 1994 {published data only}

- Ragot J‐P, Giorgi M, Marinoni M, Macchi M, Mazza P, Rizzo S, et al. Acute activity of nimesulide in the treatment of pain after oral surgery ‐ Double blind, placebo and mefenamic acid controlled study. European Journal of Clinical Research 1994;5:39‐50. [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Fassolt 1974 {published data only}

- Fassolt A. The control of pain after tonsillectomy with mefenamic acid [Mefenaminsaure (Ponstan) zur Kontrolle des Wundschmerzes nach Tonsillektomie]. Schweizerische Rundschau für Medizin Praxis = Revue suisse de médecine Praxis 1974;63(34):1040‐3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hackl 1967 {published data only}

- Hackl J. Treatment of postoperative pain with mefenamic acid [Zur Behandlung postoperativer Schmerzzustande mit Mefenaminsaure]. Die Medizinische Welt 1967;46:2796‐9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lee 2007 {published data only}

- Lee LA, Wang PC, Chen NH, Fang TJ, Huang HC, Lo CC, et al. Alleviation of wound pain after surgeries for obstructive sleep apnea. Laryngoscope 2007;117(9):1689‐94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mariani 1966 {published data only}

- Mariani L, Carli A. The use of mefenamic acid in the treatment of postoperative pain. (Clinico‐statistical data) [L'impiego dell'acido mefenamico nel trattamento del dolore postoperatorio. (Dati clinico‐statistici)]. Atti della Accademia Dei Fisiocritici in Siena ‐ Sezione Medico‐Fisica 1966;15(1):541‐51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mohing 1981 {published data only}

- Mohing W, Suckert R, Lataste X. Comparative study of fluproquazone in the management of post‐operative pain. Arzneimittel‐Forschung 1981;31(5a):918‐20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ohnishi 1983 {published data only}

- Ohnishi M, Kawai T, Ogawa N. Double‐blind comparison of piroxicam and mefenamic acid in the treatment of oral surgical pain. European Journal of Rheumatology and Inflammation 1983;6(3):253‐58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ragot 1991 {published data only}

- Ragot JP. Comparison of analgesic activity of mefenamic acid and paracetamol in treatment of pain after extraction of impacted lower 3d molar [Comparaison de l'activite antalgique de l'acide mefenamique et du paracetamol dans le traitement de la douleur apres extraction d'une 3eme molaire inferieure incluse]. L' Information Dentaire 1991;73(21):1659‐64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Rowe 1980 {published data only}

- Rowe NH, Shekter MA, Turner JL, Spencer J, Dowson J, Petrick TJ. Control of pain resulting from endodontic therapy: a double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology 1980;50(3):257‐63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Rowe 1981 {published data only}

- Rowe NH, Cudmore CL, Turner JL. Control of pain by mefenamic acid following removal of impacted molar. A double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, and Oral Pathology 1981;51(6):575‐80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Vaidya 1974 {published data only}

- Vaidya AB, Sheth MS, Manghani KK, Shroff P, Vora KK, Sheth U. Double blind trial of mefenamic acid, aspirin and placebo in patients with post‐operative pain. Indian Journal of Medical Sciences 1974;28(12):532‐6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Barden 2004

- Barden J, Edwards JE, McQuay HJ, Wiffen PJ. Relative efficacy of oral analgesics after third molar extraction. British Dental Journal 2004;197(7):407‐11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Clarke 2009

- Clarke R, Derry S, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Single dose oral etoricoxib for acute postoperative pain in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009, Issue 2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004309.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Collins 1997

- Collins SL, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. The visual analogue pain intensity scale: what is moderate pain in millimetres?. Pain 1997;72:95‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Collins 2001

- Collins SL, Edwards J, Moore RA, Smith LA, McQuay HJ. Seeking a simple measure of analgesia for mega‐trials: is a single global assessment good enough?. Pain 2001;91(1‐2):189‐94. [DOI: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00435-8] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cook 1995

- Cook RJ, Sackett DL. The number needed to treat: a clinically useful measure of treatment effect. BMJ 1995;310(6977):452‐4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cooper 1991

- Cooper SA. Single‐dose analgesic studies: the upside and downside of assay sensitivity. The Design of Analgesic Clinical Trials. Advances in Pain Research Therapy 1991;18:117‐24. [Google Scholar]

Derry 2008

- Derry S, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Single dose oral celecoxib for acute postoperative pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2008, Issue 4. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004233] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Derry C 2009a

- Derry C, Derry S, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Single dose oral naproxen and naproxen sodium for acute postoperative pain in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009, Issue 1. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004234.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Derry C 2009b

- Derry C, Derry S, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Single dose oral ibuprofen for acute postoperative pain in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009, Issue 3. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001548.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Derry P 2009

- Derry P, Derry S, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Single dose oral diclofenac for acute postoperative pain in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009, Issue 1. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004768.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Fitzgerald 2001

- FitzGerald GA, Patrono C. The coxibs, selective inhibitors of cyclooxygenase‐2. New England Journal of Medicine 2001;345(6):433‐42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Grimes 2006

- Grimes DA, Hubacher D, Lopez LM, Schulz KF. Non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs for heavy bleeding or pain associated with intrauterine‐device use. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2006, Issue 4. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006034.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hawkey 1999

- Hawkey CJ. Cox‐2 inhibitors. Lancet 1999;353(9149):307‐14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jadad 1996a

- Jadad AR, Carroll D, Moore RA, McQuay H. Developing a database of published reports of randomised clinical trials in pain research. Pain 1996;66(2‐3):239‐46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jadad 1996b

- Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJM, Gavaghan DJ, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary?. Controlled Clinical Trials 1996;17:1‐12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

L'Abbe 1987

- L'Abbé KA, Detsky AS, O'Rourke K. Meta‐analysis in clinical research. Annals of Internal Medicine 1987;107:224‐33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lethaby 2007

- Lethaby A, Augood C, Duckitt K, Farquhar C. Nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2007, Issue 4. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000400.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lloyd 2009

- Lloyd R, Derry S, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Intravenous or intramuscular parecoxib for acute postoperative pain in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009, Issue 2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004771.pub4] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Majoribanks 2010

- Marjoribanks J, Proctor M, Farquhar C, Derks RS. Nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs for dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;1:CD001751. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001751.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

McQuay 2005

- McQuay HJ, Moore RA. Placebo. Postgraduate Medical Journal 2005;81:155‐60. [DOI: 10.1136/pgmj.2004.024737] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moore 1996

- Moore A, McQuay H, Gavaghan D. Deriving dichotomous outcome measures from continuous data in randomised controlled trials of analgesics. Pain 1996;66(2‐3):229‐37. [DOI: 10.1016/0304-3959(96)03032-1] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moore 1997a

- Moore A, Moore O, McQuay H, Gavaghan D. Deriving dichotomous outcome measures from continuous data in randomised controlled trials of analgesics: use of pain intensity and visual analogue scales. Pain 1997;69(3):311‐5. [DOI: 10.1016/S0304-3959(96)03306-4] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moore 1997b

- Moore A, McQuay H, Gavaghan D. Deriving dichotomous outcome measures from continuous data in randomised controlled trials of analgesics: verification from independent data. Pain 1997;69(1‐2):127‐30. [DOI: 10.1016/S0304-3959(96)03251-4] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moore 1998

- Moore RA, Gavaghan D, Tramer MR, Collins SL, McQuay HJ. Size is everything‐large amounts of information are needed to overcome random effects in estimating direction and magnitude of treatment effect. Pain 1998;78(3):209‐16. [DOI: 10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00140-7] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moore 2003

- Moore RA, Edwards J, Barden J, McQuay HJ. Bandolier's Little Book of Pain. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003. [ISBN: 0‐19‐263247‐7] [Google Scholar]

Moore 2005

- Moore RA, Edwards JE, McQuay HJ. Acute pain: individual patient meta‐analysis shows the impact of different ways of analysing and presenting results. Pain 2005;116(3):322‐31. [DOI: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.05.001] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moore 2006

- Moore A, McQuay H. Bandolier's Little Book of Making Sense of the Medical Evidence. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006. [ISBN: 0‐19‐856604‐2] [Google Scholar]

Moore 2008

- Moore RA, Barden J, Derry S, McQuay HJ. Managing potential publication bias. In: McQuay HJ, Kalso E, Moore RA editor(s). Systematic Reviews in Pain Research: Methodology Refined. Seattle: IASP Press, 2008:15‐24. [ISBN: 978‐0‐931092‐69‐5] [Google Scholar]

Morris 1995

- Morris JA, Gardner MJ. Calculating confidence intervals for relative risk, odds ratio and standardised ratios and rates. In: Gardner MJ, Altman DG editor(s). Statistics with Confidence ‐ Confidence Intervals and Statistical Guideline. London: BMJ, 1995:50‐63. [Google Scholar]

Oehler 2003

- Oehler MK, Rees MC. Menorrhagia: an update. Acta Obstetrica et Gynecologica Scandinavica 2003;82(5):405‐22. [DOI: 10.1034/j.1600-0412.2003.00097.x] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

PACT 2010

- The NHS Information Centre, Prescribing Support Unit. Prescription cost analysis, England 2009. 2010. [ISBN: 978‐1‐84636‐408‐2] [Google Scholar]

Pringsheim 2008

- Pringsheim T, Davenport WJ, Dodick D. Acute treatment and prevention of menstrually related migraine headache: evidence‐based review. Neurology 2008;70(17):1555‐63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Roy 2010

- Roy YM, Derry S, Moore RA. Single dose oral lumiracoxib for postoperative pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2010, Issue 7. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006865.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Toms 2008

- Toms L, McQuay HJ, Derry S, Moore RA. Single dose oral paracetamol (acetaminophen) for postoperative pain in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2008, Issue 4. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004602.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Tramer 1997

- Tramèr MR, Reynolds DJM, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Impact of covert duplicate results on meta‐analysis: a case study. BMJ 1997;315:635‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]