Abstract

Background

Endometrial carcinoma is the most common gynaecological cancer in western Europe and North America. Lymph node metastases can be found in approximately 10% of women who clinically have cancer confined to the womb prior to surgery and removal of all pelvic and para-aortic lymph nodes (lymphadenectomy) is widely advocated. Pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy is part of the FIGO staging system for endometrial cancer. This recommendation is based on non-randomised controlled trials (RCTs) data that suggested improvement in survival following pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy. However, treatment of pelvic lymph nodes may not confer a direct therapeutic benefit, other than allocating women to poorer prognosis groups. Furthermore, a systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs of routine adjuvant radiotherapy to treat possible lymph node metastases in women with early-stage endometrial cancer, did not find a survival advantage. Surgical removal of pelvic and para-aortic lymph nodes has serious potential short and long-term sequelae and most women will not have positive lymph nodes. It is therefore important to establish the clinical value of a treatment with known morbidity.

Objectives

To evaluate the effectiveness and safety of lymphadenectomy for the management of endometrial cancer.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) Issue 2, 2009. Cochrane Gynaecological Cancer Review Group Trials Register, MEDLINE (1966 to June 2009), Embase (1966 to June 2009). We also searched registers of clinical trials, abstracts of scientific meetings, reference lists of included studies and contacted experts in the field.

Selection criteria

RCTs and quasi-RCTs that compared lymphadenectomy with no lymphadenectomy, in adult women diagnosed with endometrial cancer.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently abstracted data and assessed risk of bias. Hazard ratios (HRs) for overall and progression-free survival and risk ratios (RRs) comparing adverse events in women who received lymphadenectomy or no lymphadenectomy were pooled in random effects meta-analyses.

Main results

Two RCTs met the inclusion criteria; they randomised 1945 women, and reported HRs for survival, adjusted for prognostic factors, based on 1851 women.

Meta-analysis indicated no significant difference in overall and recurrence-free survival between women who received lymphadenectomy and those who received no lymphadenectomy (pooled HR = 1.07, 95% CI: 0.81 to 1.43 and HR = 1.23, 95% CI: 0.96 to 1.58 for overall and recurrence-free survival respectively).

We found no statistically significant difference in risk of direct surgical morbidity between women who received lymphadenectomy and those who received no lymphadenectomy. However, women who received lymphadenectomy had a significantly higher risk of surgically related systemic morbidity and lymphoedema/lymphocyst formation than those who had no lymphadenectomy (RR = 3.72, 95% CI: 1.04 to 13.27 and RR = 8.39, 95% CI: 4.06, 17.33 for risk of surgically related systemic morbidity and lymphoedema/lymphocyst formation respectively).

Authors’ conclusions

We found no evidence that lymphadenectomy decreases the risk of death or disease recurrence compared with no lymphadenectomy in women with presumed stage I disease. The evidence on serious adverse events suggests that women who receive lymphadenectomy are more likely to experience surgically related systemic morbidity or lymphoedema/lymphocyst formation.

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH): *Lymph Node Excision [adverse effects], Endometrial Neoplasms [*surgery], Lymphedema [etiology], Lymphocele [etiology], Quality of Life, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

MeSH check words: Adult, Female, Humans

BACKGROUND

Description of the condition

Endometrial cancer encompasses a group of tumours affecting the lining of the womb (or uterus), known as the endometrium. Worldwide it is the seventh most common cancer in women (Ferlay 2004).

Endometrial cancer occurs predominately in postmenopausal women (91% of cases in women over 50 years old (Parkin 2005). Global incidences vary due to differences in risk factors, a higher risk being associated with a ‘western’ lifestyle; the age-standardised incidence is 13.6 per 100,000 women per year in more developed countries, compared with 3.0 per 100,000 per year in less developed countries (Ferlay 2004). One of the main risk factors for endometrial cancer is unopposed oestrogen. This may come from outside the body (exogenous), such as oestrogen-only hormone replacement therapy (HRT), or be produced within the body (endogenous), as with polycystic ovarian syndrome or an oestrogen-producing tumour. Adipose tissue is an important source of endogenous oestrogen in postmenopausal women, and obesity is associated with an increased risk of endometrial cancer (Calle 2003; Quinn 2001).

Most women will present to their physician with symptoms of abnormal vaginal bleeding. This is typically post-menopausal bleeding due to the ages of highest prevalence, although younger women may present with intermenstrual bleeding, menorrhagia or a change in bleeding pattern; current guidelines from the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists recommend endometrial sampling in all women over 45 years old with abnormal vaginal bleeding. Less common symptoms are those of low pelvic pain or vaginal discharge. Most women (75 to 80%) with postmenopausal bleeding present with early disease (International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage I), where the disease is confined to the womb (Shepherd 1989 -Table 1), (Jemal 2008 - Figure 1). FIGO staging describes how far the cancer has spread, giving information about the chance of curing the cancer and what treatments are recommended. It should be noted that the FIGO staging was changed in 2009, following the publication of the protocol for this review and also any of the included and excluded studies (Pecorelli 2009, Table 2). The old staging system will be used in this review, unless otherwise stated.

Table 1.

Old (pre 2009) FIGO staging

| Stage | Extent of disease | |

|---|---|---|

| I | Tumour limited to uterine body | |

| Ia | Limited to endometrium | |

| Ib | < 1/2 myometrial depth invaded | |

| Ic | > 1/2 myometrial depth invaded | |

| II | Tumour limited to uterine body and cervix | |

| IIa | Endocervical invasion only | |

| IIb | Invasion into cervical stroma | |

| III | Extension to uterine serosa, peritoneal cavity and/or lymph nodes | |

| IIIa | Extension to uterine serosa, adnexae, or positive peritoneal fluid (ascites or washings) | |

| IIIb | Extension to vagina | |

| IIIc | Pelvic or para-aortic lymph nodes involved | |

| IV | Extension beyond true pelvis and/or involvement of bladder/bowel mucosa | |

| IVa | Extension to adjacent organs | |

| IVb | Distant metastases or positive inguinal lymph nodes | |

Figure 1.

Distribution of stage of endometrial cancer at presentation, USA 1996-2003 (all races). Adapted from Jemal 2008.

Table 2.

FIGO staging (2009)

| Stage | Extent of disease | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tumour confined to the corpus uteri | |

| IA | No or less than half myometrial invasion | |

| IB | Invasion equal to or more than half of the myometrium | |

| II | Tumour invades cervical stroma, but does not extend beyond the uterus | |

| III | Local and/or regional spread of the tumour | |

| IIIA | Tumour invades the serosa of the corpus uteri and/or adnexae | |

| IIIB | Vaginal and/or parametrial involvement | |

| IIIC Metastases to pelvic and/or para-aortic lymph nodes | ||

| IIIC1 | Positive pelvic nodes | |

| IIIC2 | Positive para-aortic lymph nodes with or without positive pelvic lymph nodes | |

| Stage IV Tumour invades bladder and/or bowel mucosa, and/or distant metastases | ||

| IVA | Tumour invasion of bladder and/or bowel mucosa | |

| IVB | Distant | |

Pelvic washings/cytology should be recorded separately and now does not change the stage

Most endometrial cancers are endometrioid adenocarcinomas. Other histological types tend to have a poorer prognosis, since they are more aggressive (high grade = G3) and present at a more advanced FIGO stage. These include adenosquamous, clear cell and serous carcinomas.

Endometrial cancer spreads directly into surrounding tissues, most commonly into the muscle of the womb, (myometrium) and into the neck of the womb (cervix). Disease spread also occurs via lymphatic vessels. Lymph is tissue fluid which drains from tissues via small lymphatic vessels to lymph nodes (or glands), which contain cells of the immune system. The lymph nodes filter and monitor lymph for signs of infection or inflammation and also trap particles, including cancer cells within them. Lymphatic drainage of the womb is primarily via the pelvic lymph nodes, which surround the external and common iliac vessels (the major blood vessels which drain blood from the lower limbs and pelvis), and then on to the para-aortic lymph nodes. Results of histopathological studies demonstrated spread to pelvic and para-aortic lymph nodes in up to 10% of cases of early stage disease (Creasman 1987). Metastasis to more distant organs is via the blood stream (haematological spread).

Description of the intervention

Standard treatment for endometrial cancer is the surgical removal of the womb, tubes and ovaries: a total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) and washings. This may be performed via an incision in the abdomen (laparotomy) or by a laparoscopic approach (key-hole surgery). For patients with a more advanced FIGO stage, adjuvant radiotherapy (and increasingly chemotherapy) is administered to treat extra-uterine spread, including spread to the lymphatic system and blood vessels (lymphovascular space involvement).

In early stage disease (FIGO stage 1 without G3 disease or without evidence of invasion into lymphatic or blood vessels in the womb - for FIGO staging see Table 1), RCTs have demonstrated that adjuvant radiotherapy does not improve overall survival, although it does reduce the number of pelvic recurrences (Kong 2007; Kong 2007a). The reason that reducing the number of pelvic recurrences does not affect survival rates is because pelvic recurrences can usually be successfully treated with radiotherapy in patients who have not previously received any pelvic radiotherapy.

Lymphadenectomy is the removal of lymph nodes. This can be the clearance of all lymph nodes from an anatomical area, or sampling of a few lymph nodes from an area. Lymphadenectomy can be used for the treatment of cancers which spread to the lymph nodes draining the site of the cancer, e.g. in breast surgery. Lymphadenectomy often refers to the systematic removal of all lymph nodes within a defined area, as opposed to lymph node sampling, which refers either to removal of a few representative lymph nodes, or removal of suspiciously enlarged nodes.

How the intervention might work

Knowledge of cancer spread gives prognostic information and guides the need for adjuvant treatment, in the form of radiotherapy, or possibly chemotherapy. There is also the possibility that lymphadenectomy is directly therapeutic; surgery removes involved lymph nodes, which may be the source of pelvic recurrences. However, lymph node involvement is rare if the tumour is of low grade (G1) or confined to the inner half of the myometrium. Hence, surgical staging involving a lymphadenectomy may only be recommended to women who are more at risk of pelvic lymph node involvement: i.e. those with higher grade tumours (G2 or G3, identified by biopsy) or those with evidence of spread to the outer half of the myometrium on pre-operative imaging (Kim 1993).

Nevertheless, lymphadenectomy is not without serious short- and long-term morbidity. Many women with endometrial cancer are elderly or obese, with serious co-morbidities, and the prolonged operative time required to perform a full lymphadenectomy may increase the risks of surgery and anaesthesia. Complications from lymphadenectomy include: damage to blood vessels during the operation; development of a blood clot in the veins of the legs or the lungs (deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolus) in the post operative period; lymphoedema (swelling of the legs due to poor lymphatic drainage) and/or pelvic lymphocyst formation (collections of lymphatic fluid). These complications can be severe and disabling, and lymphoedema and lymphocyst formation may be under-reported or under-recognised in studies.

Why it is important to do this review

There is ongoing debate regarding lymphadenectomy for the treatment of endometrial cancer. The extent of disease, as assessed by pre-operative imaging (such as MRI) and the grade of tumour (as identified through biopsies), may influence the decision to undertake lymphadenectomy or not. Lymphadenectomy may not routinely be performed and if it is, the extent of lymphadenectomy can range from taking a few lymph nodes for sampling to complete dissection of pelvic and para-aortic lymphatic tissue (pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy) depending on the experience, training and opinion of the surgeon. However, the both the new and old FIGO staging systems specifically include involvement of lymph nodes (Pecorelli 2009, Table 2).

Evidence from one retrospective non-randomised study suggested that multiple site lymph node sampling may increase survival compared to those who do not have lymph node sampling (Kilgore 1995). In this retrospective review of 649 patients with endometrial cancer, women who had multiple site lymph node sampling had an improved 5 year survival (extrapolated from survival curves) compared to women who had no pelvic node sampling (5-year survival ~90% versus ~75%; P = 0.002). Furthermore, one study found that patients who undergo extensive lymph node sampling may have an increased survival as compared with those who have fewer lymph nodes removed (Chan 2006). This retrospective analysis of 12,333 patients with endometrioid endometrial cancer demonstrated that patients with high risk disease (stage IB, grade 3 or greater) appeared to have improved 5 year survival rates following extensive lymph node removal (75.3% with one node removed versus 86.8% with ≧ 20 nodes removed; P = 0.001) However, lymphadenectomy, similar to pelvic radiotherapy (Kong 2007), may not be beneficial, since most women with endometrial cancer present at an early stage, and are therefore unlikely to have lymph node involvement. Therefore the additional surgery would make no difference to their chance of cure, or need for further treatment, and would benefit only a small minority of women, to the detriment of the majority, who would be cured by hysterectomy and BSO alone. A previous systematic review found that a survival advantage had not yet been demonstrated by an RCT, although lymph node status gave prognostic information and reduced the need for adjuvant radiotherapy in women found to have negative lymph nodes (Look 2004). A large, population-based, study of 9185 women with stage I and 881 women with stage II endometrial cancer compared outcomes stratified by whether lymph node sampling had been performed (Trimble 1998). Overall there was no significant difference in 5-year survival for women with either stage I and II disease for women who did or did not undergo lymph node sampling. In contrast, a recent retrospective study of 63 women with stage III endometrial cancer did demonstrate an improvement in disease-related survival for women who had para-aortic lymphadenectomy performed in addition to pelvic lymphadenectomy (Fujimoto 2007).

As these data demonstrate, there is scientific and clinical controversy about the role of lymphadenectomy in endometrial cancer. It is a procedure that carries significant long-term morbidity for a large minority of patients and should therefore only be performed if there is good evidence from RCTs, demonstrating improvements in survival and QOL, to support its role.

This review aimed to address the value of removing the lymph nodes to which the endometrial cancer cells may spread. This included routine removal of all of the pelvic lymph nodes (pelvic lymphadenectomy) and also the effect of routinely removing para-aortic lymph nodes. The review also assessed evidence for the value of removing clinically suspicious (enlarged) lymph nodes.

OBJECTIVES

To evaluate the effectiveness and safety of lymphadenectomy for the management of endometrial cancer.

METHODS

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

RCTs and quasi-RCTs. Crossover trials and cluster randomised trials were excluded.

Types of participants

Adult women diagnosed with endometrial cancer. Women with other concurrent malignancies were excluded.

Types of interventions

The following comparisons were included:

Pelvic lymphadenectomy versus no lymphadenectomy;

Pelvic lymphadenectomy versus pelvic lymph node sampling;

Pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy versus no lymphadenectomy;

Pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy versus pelvic lymphadenectomy;

Removal of bulky pelvic lymph nodes versus no removal of lymph nodes.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Overall survival (OS)

Secondary outcomes

Progression-free survival (PFS)

QOL measured by a validated scale

Adverse events, for example:

Direct surgical morbidity (e.g. injury to bladder, ureter, vascular, small bowel or colon), presence and complications of adhesions, febrile morbidity, intestinal obstruction, haematoma, local infection)

Surgically related systemic morbidity (chest infection, thrombo-embolic events (deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism), cardiac events (cardiac ischemias and cardiac failure), cerebrovascular accident

Recovery: delayed discharge, unscheduled re-admission

Lymphoedema and lymphocyst formation

Other side effects not categorised above

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

See: Cochrane Gynaecological Cancer Group methods used in reviews.

The following electronic databases were searched:

The Cochrane Gynaecological Cancer Collaborative Review Group’s Trial Register

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Issue 2, 2009

MEDLINE - 1966 to June 2009

EMBASE - 1966 to June 2009

For MEDLINE we developed a search strategy based on the terms related to the review topic (see Appendix 1)

See Appendix 2 for the EMBASE search strategy and Appendix 3 for the CENTRAL search strategy. Databases were searched from 1966 until 2009.

All relevant articles found were identified on PubMed and using the ‘related articles’ feature, a further search was carried out for newly published articles.

Searching other resources

Unpublished and Grey literature

Metaregister, Physicians Data Query, www.controlled-trials.com/rct, www.clinicaltrials.gov and www.cancer.gov/clinicaltrials were searched for ongoing trials. The main investigators of the relevant ongoing trials were contacted for further information, as were the major co-operative trials groups active in this area.

Hand searching

The reference lists of all relevant trials obtained by this search were hand searched for further trials.

Correspondence

Authors of relevant trials were contacted to ask if they knew of further data which may or may not have been published.

Language

Papers in all languages were sought and translations carried out if necessary.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

All titles and abstracts retrieved by electronic searching were downloaded to the reference management database Endnote, duplicates were removed and the remaining references were examined by three review authors (KM, JM, AB) independently. Those studies which clearly did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded and copies of the full text of potentially relevant references were obtained. The eligibility of retrieved papers was assessed independently by two review authors (JM, KM). Disagreements were resolved by discussion between the two review authors and if necessary by a third review author (AB). Reasons for exclusion were documented.

Data extraction and management

For included studies, data was abstracted as recommended in Chapter 7 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008). This included data on characteristics of patients (inclusion criteria, age, stage, co-morbidity, previous treatment, number enrolled in each arm) and interventions (extent of lymphadenectomy, number of lymph nodes removed, use of radiotherapy or chemotherapy), study quality, duration of follow-up, outcomes, any variables used to adjust HRs and deviations from protocol was abstracted independently by two review authors (AB, KM) onto a data abstraction form specially designed for the review. Where possible, all data extracted were those relevant to an intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis, in which participants will be analysed in groups to which they were assigned (to reduce bias). Differences between review authors would have been resolved by discussion or by appeal to a third review author (JM) if necessary.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The risk of bias in included RCTs was assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool and the criteria specified in Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook 2008 (Higgins 2008). This included an assessment of:

sequence generation

allocation concealment

blinding (assessment of blinding was restricted to blinding of outcome assessors, since it is generally not possible to blind participants and personnel to surgical interventions)

incomplete outcome data

selective reporting of outcomes

other possible sources of bias

The risk of bias tool was applied independently by two review authors (AB, KM) and differences resolved by discussion or by appeal to a third review author (HD). Results are presented in the risk of bias table and also in both a risk of bias graph and a risk of bias summary section. Results of meta-analyses were interpreted in light of the findings with respect to risk of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

For time-to-event data (overall survival, progression-free survival), we abstracted the HR and its variance from trial reports; if these were not presented, we would have attempted to abstract the data required to estimate them using Parmar’s methods (Parmar 1998) e.g. number of events in each arm and log-rank p-value comparing the relevant outcomes in each arm, or relevant data from Kaplan-Meier survival curves.

For dichotomous outcomes (adverse events), we abstracted the number of patients in each treatment arm who experienced the outcome of interest, in order to estimate a risk ratio (RR).

We also extracted the number of patients assessed at endpoint.

Dealing with missing data

We attempted to extract data on the outcomes only among participants who were assessed at endpoint. We did not impute missing outcome data; if only imputed outcome data were reported, we contacted trial authors to request data on the outcomes only among participants who were assessed.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Heterogeneity between studies was assessed by visual inspection of forest plots, by estimation of the percentage heterogeneity between trials which cannot be ascribed to sampling variation (Higgins 2003), by a formal statistical test of the significance of the heterogeneity (Deeks 2001), and if possible by sub-group analyses (see below). If there was evidence of substantial heterogeneity, the possible reasons for this were investigated and reported.

Assessment of reporting biases

We were unable to assess reporting bias as only two studies met our inclusion criteria.

Data synthesis

The findings of included trials were pooled in meta-analyses.

For time-to-event data (overall survival and progression-free survival), HRs were pooled using the generic inverse variance facility of RevMan 5. Adjusted HRs were used if available; otherwise unadjusted results were used.

For dichotomous outcomes, (adverse events), RRs were pooled.

Random effects models with inverse variance weighting were used for all meta-analyses (DerSimonian 1986).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

No sub-group analyses were performed, as only two trials met our inclusion criteria. These trials did not show any heterogeneity (I2=0).

Sensitivity analysis

No sensitivity analyses were performed as both included studies were at low risk of bias.

RESULTS

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies.

Results of the search

The search strategy identified 349 unique references. The abstracts of these were read independently by three authors and articles which obviously did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded at this stage. Eighteen articles were retrieved in full and translated into English where appropriate and up-dated versions of relevant studies were identified. The full text screening of these 18 studies excluded 11 trials for the reasons described in the table Characteristics of excluded studies. However, two completed RCTs, were identified that met our inclusion criteria and are described in the table Characteristics of included studies and there were five references which were preliminary results of the two included studies.

Searches of the grey literature did not identify any additional relevant studies.

Included studies

The two included trials (Kitchener 2009; Panici 2008) randomised 1945 women, of whom 1923 (99%) were assessed at the end of the trials and 1851 (95%) were assessed in multivariate survival analyses using Cox models.

Kitchener 2009 reported 191 (13.6%) deaths and 173 (12.3%) disease recurrences; Panici 2008 reported 53 (10.3%) deaths and 78 (15.1%) disease recurrences; Kitchener 2009 reported 38 (2.7%) instances of direct surgical morbidity, seven (0.5%) cases of surgically related systemic morbidity, 12 (0.9%) cases of lymphocyst formation and 26 (1.8%) cases of lymphoedema; Panici 2008 reported 13 (2.5%) instances of direct surgical morbidity, eight (1.6%) cases of surgically related systemic morbidity and 39 (7.6%) cases of lymphoedema/lymphocyst formation.

The Kitchener 2009 trial (ASTEC)

Design

Between 1998 and 2005, 1408 patients from 85 centres in four countries, with preoperative endometrial carcinoma thought clinically to be confined to the uterus (FIGO stage I), were randomised pre-operatively to have standard surgery (n = 704) (total hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and palpation of para-aortic lymph nodes) or standard surgery plus systematic pelvic lymphadenectomy (n = 704) (iliac and obturator lymph nodes). Patients with enlarged lymph nodes in the standard surgery arm could have these removed at the discretion of the surgeon. All operations were performed by specialist gynaecological surgeons with experience of pelvic lymphadenectomy and the operation was performed by the same surgeon, regardless of which arm the patient was randomised to. Following surgery, women with early-stage disease at intermediate or high risk of recurrence were randomised (independent of lymph-node status) into the ASTEC radiotherapy trial, in order to control for adjuvant treatment.

Participants

Patients were well matched between the two arms in terms of clinico-pathological features, although there were slightly more poor prognosis histopathological types in the lymphadenectomy arm (clear cell 10 (1%) versus 17 (2%); serous 21 (3%) versus 32 (5%)). In the lymphadenectomy arm, 58 (8%) women had no nodes removed for reasons including anaesthetic concerns, obesity, obvious late stage disease or patient request. For those in the lymphadenectomy arm who did undergo lymphadenectomy, a median of 12 nodes (range 1 to 59) were removed. Thirty-five (5%) women in the standard surgery arm underwent lymph node sampling, with a median of two nodes removed (range 1 to 27). Lymph nodes were invaded by cancerous cells in 9 patients in the standard surgery arm (27% of the 35 women who had suspicious nodes removed at the time of surgery), and in 54 (9%) of the 686 patients from the lymphadenectomy arm, who had lymph nodes removed.

Interventions

Median operating time differed significantly; 60 minutes (10 to 255) for standard surgery and 90 minutes (10 to 390) for the lymphadenectomy arm. Median hospital stay was 6 days (range 2 to 120 days) for standard surgery and 6 days (range 2 to 106 days) in the lymphadenectomy arm. Patients in the lymphadenectomy arm were more likely to have a vertical than a transverse (Pfannenstiel) abdominal incision (287 (45%) versus 384 (60%)).

One third of women in each group received adjuvant radiotherapy (standard surgery n = 227 (33%); lymphadenectomy n = 228 (33%)) with similar numbers receiving external beam radiotherapy plus vault brachytherapy (173 (25%) versus 165 (23%)) or brachytherapy only (54 (8%) versus 63 (9%))

Median follow up was 37 months (interquartile range = 24 to 58 months).

The Panici 2008 trial

Design

Over 9½ years, 514 patients, from 31 centres (30 in Italy and 1 in Chile), with preoperative endometrial carcinoma, which was clinically confined to the uterus (FIGO stage I), were randomly assigned to undergo pelvic systematic lymphadenectomy (n = 264) or no lymphadenectomy (n = 250). All eligible patients had frozen section performed on the uterus to confirm the presence of endometrioid or adenosquamous carcinoma, grade of disease and to evaluate the depth of myometrial invasion. Patients without myometrial invasion (FIGO stage IA) or those with a well-differentiated tumour and less than 50% myometrial invasion (G1, FIGO stage IB) were excluded. All other patients were randomised intraoperatively to one of the two trial arms by a block arrangement that balanced the treatment assignment within each site. Patients randomised to the pelvic lymphadenectomy arm had lymphatic tissue removed from the external iliac, superficial and common iliac regions. Dissection was considered appropriate only if 20 or more lymph nodes were removed for histopathological examination. Para-aortic node sampling or lymphadenectomy was at the discretion of the surgeon. In the no-lymphadenectomy group, no lymphatic tissue in the retroperitoneal region was removed other than bulky (>1 cm) lymph nodes detected at gross intraoperative inspection by palpation of lymph node sites.

Participants

Patients were well matched between the two arms in terms of clinico-pathological features, except for a higher proportion of FIGO stage IIIC patients in the lymphadenectomy arm, due to examination of lymph node status. All patients allocated to the lymphadenectomy arm received lymphadenectomy, with a median of 26 pelvic lymph nodes removed (range 21 to 35). In the no-lymphadenectomy arm, 56 (22%) patients had enlarged lymph nodes and underwent pelvic lymph node sampling or lymphadenectomy: 28 (11%) had more than 10 lymph nodes removed. Of these 56 patients with bulky lymph nodes, only eight (15% of those who had lymph nodes removed) had positive lymph nodes on histological examination. Aortic lymphadenectomy was performed in 69 (26%) of the 264 patients in the lymphadenectomy arm and in five (2%) of the 250 patients in the no-lymphadenectomy arm.

Interventions

Median operating time (180 minutes versus 120 minutes) and hospital in-patient stay (6 days versus 5 days) were significantly greater in the lymphadenectomy arm than the no-lymphadenectomy arm.

Rates of adjuvant therapy (pelvic external beam, brachytherapy, chemotherapy or combination of chemotherapy and radiotherapy) did not differ significantly between the two arms. The majority of patients received no adjuvant therapy (69% in the lymphadenectomy arm and 65% in the no-lymphadenectomy arm). Median follow-up was 49 months (interquartile range = 27 to 79 months).

Outcomes reported

Both trials reported overall and recurrence-free survival and used appropriate statistical techniques (HRs to correctly allow for censoring). Prognostic factors were adjusted for in the analysis of survival outcomes in each trial.

The HR in the trial of Kitchener 2009 was adjusted for: age (continuous), WHO performance status (0, 1, 2, 3, or 4), weeks between diagnosis and randomisation (<=6 weeks versus >6 weeks), surgical technique intended (open vs laparoscopic), type of incision (vertical vs Pfannenstiel vs other transverse), extent of tumour (confined vs spread), histology (endometrioid/adenocarcinoma vs other), depth of invasion (inner half vs endometrium, outer half vs endometrium), differentiation (grade 1, 2, 3), and centre (dummy variables and centres with less than five patients were grouped as one new centre). 71 patients were not included (37 standard surgery group, 34 lymphadenectomy group): 39 with no disease and 32 with differentiation not applicable (histology mixed epithelial stromal, sarcoma).

The HR in the trial of Panici 2008 was adjusted for: age (<= 65 years, >65 years), tumour grade (grade 1, 2, 3), myometrial invasion (<= 50%, >50%), and tumour stage (stage I-II, III-IV). For the distribution of these factors at baseline for each trial by treatment arm see the table Characteristics of included studies.

Adverse events (direct surgical morbidity, surgically related systemic morbidity and lymphoedema or lymphocyst formation) were reported in both trials.

Excluded studies

Eleven references were excluded, after obtaining the full text, for the following reasons:

six studies were non-RCTs including retrospective reviews where results were compared between patients receiving systematic lymphadenectomy and those who did not;

two papers were systematic reviews for the role of lymphadenectomy in endometrial cancer, neither of which identified any RCT-level evidence;

three studies were RCTs but had no randomisation for lymphadenectomy (comparing hormonal therapy or histological processing of lymph node specimens). One of these included a retrospective review comparing women who had or did not have lymphadenectomy, although there was no surgical randomisation;

For further details of all the excluded studies see the Characteristics of excluded studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

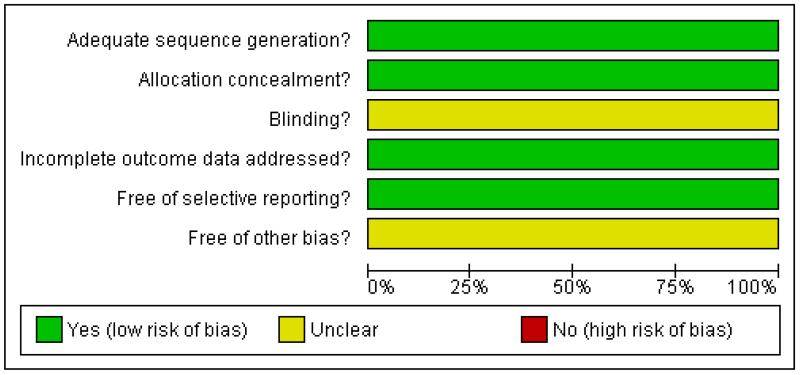

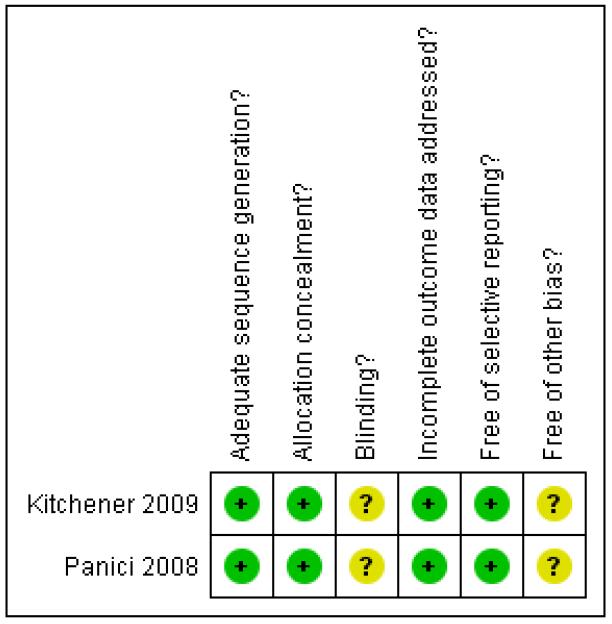

Both trials were at low risk of bias: they satisfied four of the criteria that we used to assess risk of bias - see Figure 2, Figure 3.

Figure 2.

Methodological quality graph: review authors’ judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Figure 3.

Methodological quality summary: review authors’ judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Both trials reported the method of generation of the sequence of random numbers used to allocate women to treatment arms and concealment of this allocation sequence from patients and healthcare professionals involved in the trial. Neither trial reported whether the outcome assessors were blinded. It was highly likely that both trials reported all the outcomes that they assessed, but it was not clear whether any other bias may have been present. At least 95% of women who were enrolled were assessed at endpoint in both trials.

Effects of interventions

See: Summary of findings for the main comparison SoF table All meta-analyses pooled data from the two included trials (Kitchener 2009; Panici 2008).

Meta-analyses of survival are based on HRs that were adjusted for prognostic variables.

Overall survival

Meta-analysis, assessing 1851 participants, showed no statistically significant difference in the risk of death in women who received lymphadenectomy and those who received no lymphadenectomy, after adjustment for important prognostic factors including age and tumour grade (HR= 1.07, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.43). The percentage of the variability in effect estimates that is due to heterogeneity rather than sampling error (chance) is not important (I2 = 0%).

Recurrence-free survival

Meta-analysis, assessing 1851 participants, showed no statistically significant difference in the risk of disease recurrence in women who received lymphadenectomy and those who received no lymphadenectomy, after adjustment for important prognostic factors including age and tumour grade (HR= 1.23, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.58). The percentage of the variability in effect estimates that is due to heterogeneity rather than by chance is not important (I2 = 0%).

Adverse events

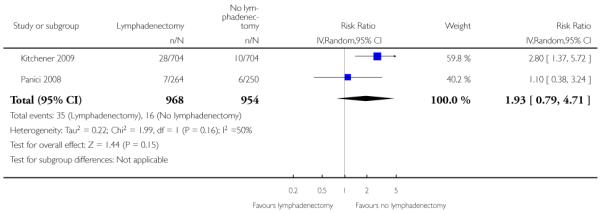

Direct surgical morbidity

Meta-analysis, assessing 1922 participants, showed no statistically significant difference in the risk of direct surgical morbidity in women who received lymphadenectomy and those who received no lymphadenectomy (RR= 1.93, 95% CI 0.79 to 4.71). The percentage of the variability in effect estimates that is due to heterogeneity rather than by chance may represent moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 50%).

Surgically related systemic morbidity

Meta-analysis of both trials, assessing 1922 participants, found that women given lymphadenectomy had a significantly higher risk of surgically related systemic morbidity than those given no lymphadenectomy (RR= 1.23, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.45). The percentage of the variability in effect estimates that is due to heterogeneity rather than by chance is not important (I2 = 0%).

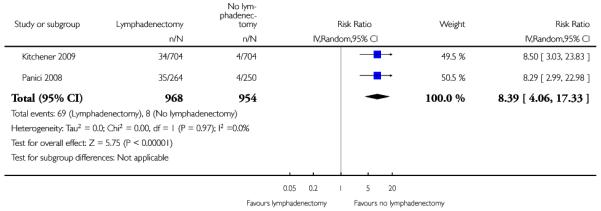

Lymphoedema or lymphocyst

Meta-analysis assessing 1922 participants, found that women given lymphadenectomy had a significantly higher risk of lymphoedema or lymphocyst formation than those given no lymphadenectomy (RR= 8.39, 95% CI 4.06, 17.33). The percentage of the variability in effect estimates that is due to heterogeneity rather than by chance is not important (I2 = 0%).

DISCUSSION

Summary of main results

We found two trials (Kitchener 2009; Panici 2008), enrolling 1945 women, that met our inclusion criteria. These trials compared lymphadenectomy with no lymphadenectomy in women with endometrial cancer, which was thought to be confined to the womb on clinical grounds.

When we combined the findings from these two trials, adjusted for important prognostic factors, we found that the risk of death and disease recurrence was higher among women who received lymphadenectomy than among women who did not (HR = 1.07, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.43 and HR = 1.23, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.58 for overall and recurrence-free survival respectively), although this was not statistically significant. Risk of adverse events was significantly higher in women who received lymphadenectomy (lymphoedema and lymphocyst formation RR = 8.39, 95% CI 4.06, 17.33).

The trials had many strengths. They gave HRs which correctly allowed for censoring and they provided information about adverse events. Both trials recruited a substantial number of participants and a reasonably large number of events were observed in the two survival outcomes and the number of women with lymphoedema. Overall there was no significant different in overall or recurrence-free survival in the two groups of women, but the risk of adverse events was consistently higher among women who received lymphadenectomy.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

We did not find any studies that assessed either pelvic lymph node sampling, pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy or the removal of bulky pelvic lymph nodes.

Although we specified QOL as an outcome of interest, neither trial reported this. QOL after treatment for cancer is an extremely important outcome, as treatment-related morbidity very often degrades the quality of the time that patients live in the future. This is especially important for a condition that has relatively good survival rates.

Surgical treatment of endometrial cancer varies between different hospitals, and until recently there has been no clear evidence to suggest whether lymphadenectomy has a role in the management of early stages of the disease. However, the evidence from these RCTs suggests that there is not a clear benefit of radical treatment for women with early stage endometrial cancer.

Quality of the evidence

Both included studies had a low risk of bias concealment of the randomisation sequence from healthcare providers and patients. Inadequate concealment of allocation are often associated with an over-estimate of the effects of treatment (Moher 1998; Schulz 1995). However, blinding of outcome assessors was not reported in either study. The evidence on overall survival is therefore more robust than that for recurrence-free survival, since blinding of outcome assessors is of less relevance for death than for disease progression.

Both trials reported a HR which is the best statistic to summarise the difference in risk in two treatment groups over the duration of a trial, when there is “censoring” i.e. the time to death (or disease progression) is unknown for some women as they were still alive (or disease free) at the end of the trial.

The two studies gave consistent evidence about all outcomes, with the exception of direct surgical morbidity where the trial of Kitchener 2009 reported a significantly higher risk of direct surgical morbidity for women who received lymphadenectomy than for those who do not, whereas the trial of Panici 2008 found no significant difference. For survival outcomes we cannot be sure whether a lymphadenectomy improves survival or increases the risk of death or recurrence. A substantial number of women experienced disease recurrence, adverse events or death, which helps to ensure high quality evidence.

Both studies randomised women who were thought on clinical evidence to have disease confined to the uterus. However, the timing of randomisation varied: one randomised pre-operatively (Kitchener 2009) and one following examination of the uterus at time of surgery (Panici 2008). Another difference between the two trials was the median number of lymph nodes removed: 12 (range 1 to 59) in the Kitchener 2009 study and 26 (range 21 to 35) in the Panici 2008 study. However, despite this, 5-year disease-free survival rates were similar and a pre-defined sub-group analysis within the Kitchener 2009 found there was a trend to poorer survival, if more lymph nodes were removed. One major difference between the studies was that the Kitchener 2009 study contained low risk early stage patients (49% of the standard surgery group and 42% of the lymphadenectomy group), who were specifically excluded from Panici 2008, following examination of the uterus by frozen section intra-operatively. However, a pre-defined subgroup analysis within the Kitchener 2009 study found no evidence for a difference in the relative effect of lymphadenectomy (p = 0·55 for overall survival and p=0·35 for recurrence-free survival) when groups were stratified into low-risk early-stage disease, intermediate-risk and high-risk early-stage disease, and advanced disease. From a clinical management point of view, routine use of whole uterine frozen section is not universally available and resource intensive, and in addition, as the two studies had similar outcomes in their high risk groups, unlikely to have had a major influence on the results.

Both trials permitted removal of suspicious lymph nodes in patients allocated to no lymphadenectomy, at the discretion of the surgeon. Although relatively small numbers of patients had lymph nodes removed in the control groups of each study (35 women in Kitchener 2009, 56 women in Panici 2008), this may cause some difficulty in interpretation of the results, although would reflect clinical practice, if lymphadenectomy was not standard treatment in the absences of suspicious lymph nodes.

Potential biases in the review process

A comprehensive search was performed, including a thorough search of the grey literature and all studies were sifted and data extracted by three review authors independently. We restricted the included studies to RCTs as they provide the strongest level of evidence available. Hence we have attempted to reduce bias in the review process.

The greatest threat to the validity of the review is likely to be the possibility of publication bias i.e. studies that did not find the treatment to have been effective may not have been published. We were unable to assess this possibility as we found only two included studies. However, as neither study found a statistically significant difference between lymphadenectomy and no lymphadenectomy, publication bias seems unlikely.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Two previous systematic reviews did not find any RCT data examining the role of lymphadenectomy (Look 2004; Salvesen 2001), although these studies pre-date the two studies identified in this review. A pooled HR for overall survival in the Kitchener 2009 and Panici 2008 studies was reported as 1·17 (95%CI 0·91 to 1·50) (Kitchener 2009a), which differs from this meta-analysis, where combined data were adjusted for prognostic factors.

Previous studies and reviews have been based on data from nonrandomised studies. As discussed above, some retrospective studies have demonstrated benefit from pelvic lymphadenectomy (Chan 2006; Kilgore 1995), whereas other studies have not (Trimble 1998; van Lankveld 2006).

One retrospective review of 649 patients with endometrial cancer, found that women who had multiple site lymph node sampling had an improved 5-year survival (extrapolated from survival curves) compared to women who had no pelvic node sampling (5-year survival ~90% versus ~75%; P= 0.002) (Kilgore 1995). However, only disease specific survival was recorded, non-endometrial cancer deaths were censored, and there were no details about patient characteristics, which are known to have an influence on endometrial cancer survival, e.g. age. Furthermore, retrospective population-based studies, either did not demonstrate a survival advantage to lymphadenectomy (van Lankveld 2006), or only for women in high-risk sub-groups (high grade (G3) stage I disease who did undergo lymph node sampling (five-year relative survival for no node sampling 0.83 ± 0.05 (n = 497) versus node sampling 0.92 ± 0.04 (n = 553); P = 0.0110 (Trimble 1998).

AUTHORS’ CONCLUSIONS

Implications for practice

These data do not support the routine use of pelvic lymphadenectomy in the treatment of endometrial cancer thought to be confined to the uterus at presentation. There was no statistically significant difference in survival between the groups, and, in terms of harmful effects of treatment, women who did not receive lymphadenectomy showed a clear benefit. No good quality data were found which assessed the role of para-aortic lymphadenectomy, or removal of grossly enlarged lymph nodes.

It is interesting that results demonstrating no benefit of routine lymphadenectomy in presumed early stage endometrial cancer reflect results of RCTs which have examined the role of pelvic radiotherapy in these women (Kong 2007). In addition, as there was no difference in pattern of recurrence between the pelvic lymphadenectomy and standard surgery groups in the Kitchener 2009 study, which further supports the survival evidence that lymphadenectomy gives prognostic information only, rather than a direct therapeutic benefit. Whilst prognostic information is useful, these data also demonstrate that there is a real cost to gathering this information, and studies which do not look at the long term sequelae of lymphadenectomy do not allow patients to make fully informed decisions about their healthcare.

Implications for research

There are still important questions to be answered about the role of lymphadenectomy in endometrial cancer. However, neither this meta-analysis of pelvic lymphadenectomy in early-stage endometrial cancer nor a meta-analysis of radiotherapy for early-stage endometrial cancer (Kong 2007) support routine adjuvant treatment for early stage disease.

Both of the studies identified in this review examined pelvic lymphadenectomy. We were unable to identify any studies which assessed lymph node sampling, rather than lymph node removal, or looked at the difference between pelvic and para-aortic lymph node removal. These interventions have yet to be assessed by RCTs.

It is not known whether pelvic and para-aortic lymph node dissection confers any benefit over pelvic lymphadenectomy alone. Importantly, the Kitchener 2009 and Panici 2008 data caution against the assumption that even more surgery will result in improved survival and the role of pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy remains to be tested in an RCT.

Studies to determine the role of adjuvant treatment in early stage cancer have highlighted that for most women, simple surgery alone is sufficient to provide cure. Further research is needed to allow more individualised treatment strategies, ensuring that women with more aggressive cancers receive appropriate treatment, whilst not exposing women with a better prognosis to potentially serious side effects. In addition, it is imperative to assess the impact of any intervention on quality of life in any future study, particularly for a cancer with good survival rates.

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY.

The role of removing lymph nodes as part of standard surgery for endometrial cancer

Cancer arising from the lining of the womb, known as endometrial carcinoma, is now the most common gynaecological cancer in western Europe and North America. Most women (75%) still have their tumour confined to the body of the womb at diagnosis and three-quarters of women with endometrial cancer will survive for five years after diagnosis. Lymph node metastases can be found in approximately 10% of women, who clinically have cancer confined to the womb at diagnosis, and removal of all pelvic and para-aortic lymph nodes is widely advocated, even for women with presumed early stage cancer. Lymph node removal is part in the international staging sytem (FIGO) for endometrial cancer. This recommendation is based on non-randomised studies that suggested improvement in survival following removal of pelvic and para-aortic lymph nodes. However, treatment of pelvic lymph nodes may not be directly therapeutic and may just indicate that a woman has a more aggressive cancer and therefore a poorer prognosis. Results of a systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs of routine radiotherapy to treat possible lymph node metastases in women with early-stage endometrial cancer, did not improve survival, which was contrary to previously recommended treatment, based on evidence from non-randomised studies. Hence, more treatment to lymph nodes might not necessarily be better treatment, especially as surgical removal of pelvic and para-aortic lymph nodes has serious potential short and long-term harmful effects and most women will not have positive lymph nodes.

We found only two trials that compared lymphadenectomy with no lymphadenectomy in women with endometrial cancer. These two trials enrolled 1945 women. When we combined the findings from these two trials, we found that there was no evidence that women who received lymphadenectomy were less likely or more likely to die or have a relapse of their cancer. There were a considerable number of deaths and disease recurrences in the trials. Kitchener 2009 reported 191 deaths and 173 disease recurrences; Panici 2008 reported 53 deaths and 78 disease recurrences, so the estimates are likely to be accurate. The uncertainty of whether lymphadenectomy or no lymphadenectomy is best probably reflects the fact that there is no benefit in undertaking lymphadenectomy, rather than a lack of statistical power to detect a difference. More women experienced severe adverse events as a consequence of lymphadenectomy than those having no lymphadenectomy. The main limitations of the review were that we did not find any trials that evaluated either pelvic lymph node sampling, pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy or the removal of bulky pelvic lymph nodes and the fact that quality of life (QOL) was not reported in either trial. The QOL for women following treatment is especially important for a condition that has relatively good survival rates.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

JM is a Clinical Lecturer and Subspecialist Trainee in Gynaecological Oncology and her post is funded jointly by Macmillan Cancer Support and NIHR NCRCCD through Oxford University Clinical Academic Graduate School (OUCAGS@medsci.ox.ac.uk), to whom she is very grateful. KM is a Academic Clinical Fellow, also funded by NIHR NCRCCD through OUCAGS. We thank Chris Williams for clinical and editorial advice, Jane Hayes for designing the search strategy and running the searches, Gail Quinn and Clare Jess for their contribution to the editorial process and the reviewers for their helpful comments.

SOURCES OF SUPPORT

Internal sources

No sources of support supplied

External sources

Department of Health, UK.

NHS Cochrane Collaboration programme Grant Scheme CPG-506

CHARACTERISTICS OF STUDIES

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | Multi-centre RCT randomising patients from 85 centres in four countries (UK, South Africa, Poland, and New Zealand) | |

| Participants | 1408 women with histologically proven endometrial carcinoma thought preoperatively to be confined to the corpus Median age at the time of randomisation was 63 years (range:36 to 89) for standard surgery and 63 years (range: 34 to 93) for lymphadenectomy Time from diagnosis to randomisation was ≤ 6 weeks for 576 (82%) women in the standard surgery group versus 588 (84%) in the lymphadenectomy arm and >6 weeks for 128 (18%) women in the standard surgery group vs 116 (16%) in the lymphadenectomy arm. 1057 patients (75%) had WHO performance status 0; 295 (21%) status 1; 45 (3%) status 2; nine (1%) status 3; and two (0%) women had performance status 4, similarly spread between the two groups 650 (92%) of women had open surgery and 54 (8%) had laparoscopic surgery in the standard surgery group vs 659 (94%) open and 45 (6%) laparoscopic in the lymphadenectomy group Baseline characteristics below exclude patients whose pathology details did not confirm endometrial cancer: 39 women (21 standard surgery group, 18 lymphadenectomy group) who had no other tumour in the surgical specimen; atypical hyperplasia; or cervical, ovarian, or colorectal cancer Tumour was confined to the corpus uteri in 1091 (80%) women and spread beyond the corpus in 274 (20%) women: 553 (81%) standard surgery; 538 (79%) lymphadenectomy Depth of invasion was as follows for standard surgery: endometrium only: 96 (14%); inner half of myometrium: 369 (55%); outer half of myometrium: 212 (31%): unknown: 6 (0.9%). Depth of invasion was as follows for lymphadenectomy: endometrium only: 89 (13%); inner half of myometrium: 310 (46%); outer half of myometrium: 274 (41%): unknown: 13 (1.9%) FIGO staging. Stage IIIC was not included and women with positive lymph nodes were classified irrespective of nodal status. In the standard surgery group 553 patients (81%) were stage I according to FIGO, 86 (13%) were stage II and 38 (5.6%) were stage III or IV. FIGO stage was unknown in 6 (0.9%) patients. In the lymphadenectomy group 532 patients (78%) were stage I according to FIGO, 91 (13%) were stage II and 52 (7. 5%) were stage III or IV. FIGO stage was unknown in 11 (1.6%) patients Histological cell types were as follows for standard surgery vs lymphadenectomy: Endometrioid: 545 (80%) vs 541 (79%); Adenocarcinoma NOS: 46 (7%) vs 37 (5%); Clear cell: 10 (1%) vs 17 (2%); Serous: 21 (3%) vs 32 (5%); Squamous: 6 (1%) vs 5 (1%); Mucinous: 1 (<1%) vs 4 (1%); Mixed epithelial stromal: 7 (1%) vs 8 (1%); Sarcoma: 10 (1%) vs 9 (1%); Other epithelial: 4 (1%) vs 6 (1%); Mixed epithelial: 31 (5%) vs 25 (4%); Unknown: 2 (0.5%) in both groups. Tumour grade was as follows for standard surgery vs lymphadenectomy: 225 women (33%) vs 213 (31%) had tumour grade 1; 300 (44%) vs 290 (43%) grade 2; 139 (20%) vs 158 (23%) grade 3; and in 19 (3%) vs 25 (4%) women the grade was unknown or not applicable. Of the 1403 women who completed surgery, surgical technique used in the standard surgery group was as follows: laparoscopic: 42 (6%); vertical incision: 287 (45%); Pfannenstiel incision: 311 (49%); other transverse: 43 (7%); unknown: 6. Surgical technique used in the lymphadenectomy group was as follows: laparoscopic: 45 (6%); vertical incision: 384 (60%); Pfannenstiel incision: 208 (32%); other transverse: 49 (8%); unknown: 7. Five women (2 standard surgery; three lymphadenectomy) did not have completed surgery |

|

| Interventions |

Intervention: Lymphadenectomy: Women in the lymphadenectomy group had standard surgery plus a systematic dissection of the iliac and obturator nodes. If the nodes could not be dissected thoroughly because of obesity or anaesthetic concern, sampling of suspect nodes was recommended and para-aortic node sampling was at the discretion of the surgeon Comparison: Standard surgery: Women in the standard surgery group had a hysterectomy and BSO, peritoneal washings, and palpation of para-aortic nodes. Nodes that were suspicious could be sampled if the surgeon believed it to be in the woman’s best interest |

|

| Outcomes | Overall survival Recurrence-free survival Surgical complications |

|

| Notes | The median duration of follow up was 37 months (IQR 24 to 58 months) Specialist gynaecological surgeons who were experienced in pelvic lymphadenectomy undertook all surgical procedures 69 women in the lymphadenectomy group received a different intervention from the one to which they were assigned: Three women had no surgery, two had subtotal hysterectomy, in six women it was unknown and in 58 patients (8%) no nodes were taken In the Standard surgery group two had no surgery, six subtotal hysterectomy, in 11 women details were unknown and 35 women (5%) had nodes taken No adjuvant radiotherapy was received by 471 (67%) in the standard surgery group and 469 (67%) in the lymphadenectomy group |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Yes | “We used a method of minimisation. Stratification factors were centre, WHO performance status (0-1 versus 2 to 4), time since diagnosis (<= 6 weeks versus > 6 weeks), and planned surgical approach (open versus laparoscopic)” Minimisation is a method which attempts to randomise while at the same time balancing the groups for several prognostic variables, so the method of sequence generation was adequate in this trial |

| Allocation concealment? | Yes | “Randomisation was done by a telephone call to the Medical Research Council Clinical Trials Unit (MRC CTU)” |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Unclear | Not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Yes | For multivariate Cox model: % analysed: 1337/1408 (95%) |

| Free of selective reporting? | Yes | All important survival and adverse event outcomes have been reported. Survival outcomes have been analysed using appropriate statistical techniques to account for censoring |

| Free of other bias? | Unclear | Insufficient information to assess whether an important risk of bias exists |

| Methods | Multicentre RCT randomising patients from Italy and Chile | |

| Participants | Women with preoperative International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics stage I endometrial carcinoma Median age at the time of randomisation was 62 years (IQR: 56-68): standard surgery 63 (IQR: 55 to 68); lymphadenectomy 63 (IQR: 56 to 68) 386 patients (75%) were stage I according to FIGO (standard surgery: 195 (78%); lymphadenectomy: 191 (72%)); 43 (8%) were stage II (standard surgery: 21 (8%); lymphadenectomy: 22(8%)); 71 (14%) were stage III (standard surgery: 27 (11%); lymphadenectomy: 44 (17%)); and six (1%) were stage IV (standard surgery: 3 (1%); lymphadenectomy: 3 (1%)). FIGO stage was unknown in eight (2%) patients (two in each group) Histological cell types were similar between the two groups and were as follows: Endometrioid: 474 (92%); Adenosquamous: 33 (6.4%); Clear cell: 1 (0%); Serous: 3 (0. 6%); Mullerian mixed malignant tumour: 2 (0.4); Tumour not found: 1 (0%) 38 women (7%) had tumour grade 1 (standard surgery: 19 (8%); lymphadenectomy: 19 (7%)); 298 (58%) grade 2 (standard surgery: 148 (59%); lymphadenectomy: 150 (57%)); 169 grade 3 (33%) (standard surgery: 78 (31%); lymphadenectomy: 91 (35%)); and in nine (2%) women the grade was unknown (standard surgery: 5 (2%) ; lymphadenectomy 4 (1.5%)) |

|

| Interventions | For both the lymphadenectomy arm and the no-lymphadenectomy arm, primary surgery included standard hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy Intervention: Lymphadenectomy group underwent external/common iliac and superficial obturator node dissection. Systematic /para-aortic lymphadenectomy at surgeons discretion Comparison: Removal of bulky (>1cm) nodes at surgeons discretion in no lymphadenectomy arm |

|

| Outcomes | Overall survival Disease-free survival (defined as the time from random assignment to the earliest occurrence of relapse or death from any cause) Severe intraoperative complications Postoperative complications |

|

| Notes | The median duration of follow up was 49 months (IQR 27-79 months) 38 women in the Lymphadenectomy group had fewer than 20 nodes resected In the Standard surgery group 56 women (22%) underwent lymph node sampling/removal, where 17 patients had 20 pelvic lymph nodes or more resected Para-aortic lymphadenectomy was performed in 69 (26%) of the 264 patients in the lymphadenectomy group and in 5 (2%) in the standard surgery group Adjuvant treatment (chemotherapy and radiotherapy) did not vary significantly between the two arms (no adjuvant therapy in 182 (69%) of the lymphadenectomy group and in 162 (65%) of the standard surgery group (P = 0.07) |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Yes | “Patients were randomly assigned to one of the two trial arms by a block arrangement that balanced the treatment assignment within each site” |

| Allocation concealment? | Yes | “Intraoperative random assignment was performed centrally by telephone at the Mario Negri Institute, Milan” |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Unclear | Not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Yes | For all outcomes: % analysed: 514/537 (96%) By treatment arm: Intervention: 264/273 (97%) Comparison: 250/264 (95%) |

| Free of selective reporting? | Yes | All important survival and adverse event outcomes have been reported. Survival outcomes have been analysed using appropriate statistical techniques to account for censoring |

| Free of other bias? | Unclear | Insufficient information to assess whether an important risk of bias exists |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Babilonti 1989 | Retrospective review; comparison of lymphadenectomy versus no lymphadenectomy looking at short-term complications |

| Chan 2006 | Retrospective notes review |

| Huh 2008 | All patients had lymph node dissection. Study randomised processing of samples |

| Look 2004 | Systematic review - no RCT evidence found. |

| Mannel 1989 | Retrospective study, no lymphadenectomy randomisation |

| Mariani 2000 | Retrospective study |

| Nahhas 1980 | Retrospective review of treatment of patients with stage II endometrial cancer. No randomisation |

| Quinn 1993 | RCT of progesterone therapy for high risk endometrial ca - no surgical randomisation. Comparison of outcomes of 238 women who received pelvic lymphadenectomy versus 774 women who did not. Women who had lymphadenectomy were younger and had less myometrial invasion. Longer overall survival in women with lymphadenectomy. No difference in pattern of recurrence |

| Rubin 1990 | retrospective review of management |

| Salvesen 2001 | Systematic review of role of lymphadenopathy in gyn ae malignancies - no RCT found for endometrial cancer |

| Schulz 1986 | RCT of adjuvant hormonal therapy after surgery for endometrial cancer |

DATA AND ANALYSES

Comparison 1.

Survival

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Overall survival | 2 | 1851 | Hazard Ratio (Random, 95% CI) | 1.07 [0.81, 1.43] |

| 2 Recurrence-free survival | 2 | 1851 | Hazard Ratio (Random, 95% CI) | 1.23 [0.96, 1.58] |

Comparison 2.

Adverse events

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Direct surgical morbidity | 2 | 1922 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.93 [0.79, 4.71] |

| 2 Surgically related systemic morbidity | 2 | 1922 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 3.72 [1.04, 13.27] |

| 3 Lymphoedema or lymphocyst | 2 | 1922 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 8.39 [4.06, 17.33] |

Analysis 1.1. Comparison 1 Survival, Outcome 1 Overall survival

Review: Lymphadenectomy for the management of endometrial cancer

Comparison: 1 Survival

Outcome: 1 Overall survival

|

Analysis 1.2. Comparison 1 Survival, Outcome 2 Recurrence-free survival

Review: Lymphadenectomy for the management of endometrial cancer

Comparison: 1 Survival

Outcome: 2 Recurrence-free survival

|

Analysis 2.1. Comparison 2 Adverse events, Outcome 1 Direct surgical morbidity

Review: Lymphadenectomy for the management of endometrial cancer

Comparison: 2 Adverse events

Outcome: 1 Direct surgical morbidity

|

Analysis 2.2. Comparison 2 Adverse events, Outcome 2 Surgically related systemic morbidity

Review: Lymphadenectomy for the management of endometrial cancer

Comparison: 2 Adverse events

Outcome: 2 Surgically related systemic morbidity

|

Analysis 2.3. Comparison 2 Adverse events, Outcome 3 Lymphoedema or lymphocyst

Review: Lymphadenectomy for the management of endometrial cancer

Comparison: 2 Adverse events

Outcome: 3 Lymphoedema or lymphocyst

|

Appendix 1. MEDLINE search strategy

1 exp Lymph Node Excision/

2 (lymph adj node adj5 (excision* or dissection* or surg* or removal or clearance)).mp.

3 lymphadenectom*.mp.

4 1 or 2 or 3

5 exp Endometrial Neoplasms/

6 (endometr* adj5 (neoplas* or carcinom* or malignan* or cancer* or tumor* or tumour*)).mp.

7 5 or 6

8 randomized controlled trial.pt.

9 controlled clinical trial.pt.

10 randomized.ab.

11 randomly.ab.

12 trial.ab.

13 groups.ab.

14 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13

15 4 and 7 and 14

Key:

mp=title, original title, abstract, name of substance word, subject heading word, pt=publication type, ab=abstract

Appendix 2. EMBASE search strategy

1 exp lymphadenectomy/

2 (lymph adj node adj5 (excision* or dissection* or surg* or removal or clearance)).mp.

3 lymphadenectom*.mp.

4 1 or 2 or 3

5 exp endometrium tumor/

6 (endometr* adj5 (neoplas* or carcinom* or malignan* or cancer* or tumor* or tumour*)).mp.

7 5 or 6

8 exp controlled clinical trial/

9 randomized.ab.

10 randomly.ab.

11 trial.ab.

12 groups.ab.

13 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12

14 4 and 7 and 13

Key

mp=title, abstract, subject headings, heading word, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer name, ab=abstract

Appendix 3. CENTRAL search strategy

#1 MeSH descriptor Lymph Node Excision explode all trees

#2 lymphadenectom*

#3 (lymph NEAR node) NEAR/5 excision*

#4 (lymph NEAR node) NEAR/5 dissection*

#5 (lymph NEAR node) NEAR/5 surg*

#6 (lymph NEAR node) NEAR/5 removal

#7 (lymph NEAR node) NEAR/5 clearance

#8 (#1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7)

#9 MeSH descriptor Endometrial Neoplasms explode all trees

#10 endometr* NEAR/5 neoplas*

#11 endometr* NEAR/5 carcinom*

#12 endometr* NEAR/5 malignan*

#13 endometr* NEAR/5 cancer*

#14 endometr* NEAR/5 tumor*

#15 endometr* NEAR/5 tumour*

#16 (#9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15)

#17 (#8 AND #16)

Appendix 4. Data abstraction form

Lymphadenectomy for the management of endometrial cancer

Paper ID:

Reviewer:

THE DATA COLLECTION CHECKLIST

April 2009

DATA COLLECTION

Once potentially relevant studies have been identified for a review, the following data should be extracted independently by two reviewers.

Please record your name and the Study ID (first author and year of publication) in the space provided on this page and on any page(s) which may be separated from the main checklist, e.g. Results section.

For all items reviewers should mark an X against the appropriate response in each case. In addition it will be helpful if you cut and paste relevant supporting text and state its original location in the paper (page/column/paragraph). This facilitates later comparisons of extracted data. Any other comments can also be recorded in the right-hand side boxes.

Data which is missing or ‘UNCLEAR’ in a published report should be marked clearly on the data collection form.

Items in the data extraction sheet which are clearly not applicable to the study in question should be marked accordingly (i.e. N/A). Following data extraction, reviewers should compare their completed data extraction sheets and attempt to reach agreement for each item on the checklist before submitting their completed data records to

SCOPE OF REVIEW: INCLUSION/EXCLUSION CRITERIA

| Inclusion criteria | Yes/No/Unclear | Relevant supporting text and location: (page/column/paragraph) |

|---|---|---|

| Were participants adult women diagnosed with endometrial cancer? | ||

Did the trial include at least one of the following comparisons?

|

||

|

Was the type of study design, as described by the authors either: Randomised controlled trial (RCT) Quasi-randomised controlled trial (Quasi-RCT) |

||

| Exclusion criteria | ||

| Did the trial not include women with other concurrent malignancies? | ||

| Was the trial not cluster randomised or not a crossover trial? | ||

| If any of the inclusion criteria are not satisfied and the answer to any of the questions above is “NO”, the study should be excluded from the review. COLLECT NO FURTHER DATA | ||

| STUDY DETAILS | Relevant supporting text and location. (page/column/paragraph) |

|---|---|

|

Country: If multi-centre please give details. Please state UNCLEAR if information is not available. |

|

| Setting: | |

|

Duration: Indicate N/A as appropriate |

|

| Median length of follow-up: | |

| Mean length of follow-up: | |

| Min length of follow-up: | |

| Max length of follow-up: | |

| Additional information: |

| Baseline characteristics of participants: | Relevant supporting text and location. (page/column/paragraph) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | Mean = Years SD = Median = Years Range: |

|

| FIGO stage | Number (%) stage I: Number (%) stage II: Number (%) stage III: Number (%) stage IV: Number (%) unknown: |

|

| Grade | Number (%) grade I: Number (%) grade II: Number (%) grade III: Number (%) unknown: |

|

| Co-morbidities | ||

| Previous treatment | ||

| Additional information |

ASSESSMENT OF RISK OF BIAS

|

Sequence Generation Was the allocation sequence adequately generated? Describe the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups |

Tick one row | Relevant supporting text and location. (page/column/paragraph) |

| Yes e.g. a computer-generated random sequence or a table of random numbers | ||

| No e.g. Non-randomised or Quasi-randomised (Participants allocated on basis of date of birth, clinic id-number or surname) | ||

| Unclear: Insufficient information about the sequence generation | ||

|

ALLOCATION CONCEALMENT Was the randomisation sequence for allocating participants to the different arms of the trial adequately concealed, to prevent both participants the clinicians providing treatment predicting in advance which arm of the trial a women would be assigned to? |

||

| Yes e.g. where the allocation sequence could not be foretold | ||

| No e.g. allocation sequence could be foretold by patients, investigators or treatment providers | ||

| Unclear e.g. if the use of assignment envelopes is described, but it remains unclear whether envelopes were sequentially numbered, opaque and sealed | ||

|

BLINDING OF OUTCOME ASSESSORS: Were the clinicians who assessed disease progression at the end of follow-up prevented from knowing which arm of the trial the women were assigned to? |

||

| Yes. Outcome assessors were blinded | ||

| No. No blinding or incomplete blinding of outcome assessors | ||

| Unclear. Insufficient information to permit judgement of ‘yes’ or ‘no’; |

| LOSS TO FOLLOW UP: | Enter numbers below | Relevant supporting text and location. (page/column/paragraph) |

|---|---|---|

| How many participants were enrolled in each treatment arm? Intervention group: Comparison group: |

||

| How many participants were assessed at the end of follow-up in each treatment arm? Intervention group: Comparison group: |

||

| What % of patients were lost to follow-up? Intervention group: Comparison group: Overall: |

||

| Now code satisfactory level of loss-to-follow up as Yes/No/unclear: | Tick one row below | |

| Yes: if fewer than 20% of patients were lost to follow-up and reasons for loss to follow-up were similar in both treatment arms | ||

| No: if more than 20% of patients were lost to follow or reasons for loss to follow-up were different in different treatment arms | ||

| Unclear: If loss to follow was not reported | ||

|

Selective Reporting of Outcomes: Are reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting? |

||

| Yes e.g if review reports all outcomes specified in the protocol | ||

| No | ||

| Unclear | ||

|

Other potential threats to validity: Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a high risk of bias? |

||

| Yes | ||

| No | ||

| Unclear |

CHARACTERISTICS OF THE INTERVENTIONS

|

Describe the intervention(s) for each study group. Report this in the words of the paper and give specific details if they are provided e.g. type of surgeon (gynaeoncologist, gynaecologist, general surgeon) and experience of surgeon, etc. |

Location of text (page/column/paragraph) |

| Intervention details: | |

| Comparison details: | |

|

Did any women receive a different intervention from the one to which they were assigned? Yes/No/Unclear |

|

| If the answer to the question above is YES, record any reported changes of assigned treatment | |

| Intervention: | |

| Comparison: | |

|

If women received treatments different from those to which they were assigned, were outcomes reported in the groups to which they were assigned? Yes/No/Unclear |

| OUTCOMES | ||

|---|---|---|

| Overall survival | ||

| If the following were reported, record the value | Value | Relevant supporting text and location. (page/column/paragraph) |

| Unadjusted hazard ratio (HR) Was the comparison group the reference group for the estimate of the HR? |

Yes/No/Unclear | |

| 95% confidence on unadjusted HR Lower 95% confidence limit Upper 95% confidence limit |

||

| Adjusted hazard ratio (HR) Was the comparison group the reference group for the estimate of the HR? List the factors for which the HR was adjusted: |

Yes/No/Unclear | |

| 95% confidence on adjusted HR Lower 95% confidence limit Upper 95% confidence limit |

||

| If a HR was reported, record the number of women in each treatment arm on whom the estimated HR was based: Number of women in intervention arm: Number of women in comparison arm: |

||

| If a HR was reported, and if the study was based on a pre-specified protocol for assigning women to intervention group or comparison group, was the HR based on an intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis? i.e. were women analysed in the groups to which they were assigned, regardless of what treatment they received? | Yes/No/Unclear | |

| SE(HR) | ||

| SE(ln(HR)) | ||

| Var(HR) | ||

| Var(ln(HR)) | ||

| Kaplan Meier plots | Yes/No | |

| Minimum follow up time | ||

| Maximum follow up time | ||

| Log rank p-value | ||

| Was Cox regression reported? | Yes/No | |

| Cox p-value |

| OUTCOMES | ||

|---|---|---|

| Progression-free survival | ||

| If the following were reported, record the value | Value | Relevant supporting text and location. (page/column/paragraph) |

| Unadjusted hazard ratio (HR) Was the comparison group the reference group for the estimate of the HR? |

Yes/No/Unclear | |

| 95% confidence on unadjusted HR Lower 95% confidence limit Upper 95% confidence limit |

||

| Adjusted hazard ratio (HR) Was the comparison group the reference group for the estimate of the HR? List the factors for which the HR was adjusted: |

Yes/No/Unclear | |

| 95% confidence on adjusted HR Lower 95% confidence limit Upper 95% confidence limit |

||

| If a HR was reported, record the number of women in each treatment arm on whom the estimated HR was based: Number of women in intervention arm: Number of women in comparison arm: |

||