Abstract

Background

This review updates parts of two earlier Cochrane reviews investigating effects of gabapentin in chronic neuropathic pain (pain due to nerve damage). Antiepileptic drugs are used to manage pain, predominantly for chronic neuropathic pain, especially when the pain is lancinating or burning.

Objectives

To evaluate the analgesic effectiveness and adverse effects of gabapentin for chronic neuropathic pain management.

Search methods

We identified randomised trials of gabapentin in acute, chronic or cancer pain from MEDLINE, EMBASE, and CENTRAL. We obtained clinical trial reports and synopses of published and unpublished studies from Internet sources. The date of the most recent search was January 2011.

Selection criteria

Randomised, double-blind studies reporting the analgesic and adverse effects of gabapentin in neuropathic pain with assessment of pain intensity and/or pain relief, using validated scales. Participants were adults aged 18 and over.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently extracted data. We calculated numbers needed to treat to benefit (NNTs), concentrating on IMM-PACT (Initiative on Methods, Measurement and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials) definitions of at least moderate and substantial benefit, and to harm (NNH) for adverse effects and withdrawal. Meta-analysis was undertaken using a fixed-effect model.

Main results

Twenty-nine studies (3571 participants), studied gabapentin at daily doses of 1200 mg or more in 12 chronic pain conditions; 78% of participants were in studies of postherpetic neuralgia, painful diabetic neuropathy or mixed neuropathic pain. Using the IMMPACT definition of at least moderate benefit, gabapentin was superior to placebo in 14 studies with 2831 participants, 43% improving with gabapentin and 26% with placebo; the NNT was 5.8 (4.8 to 7.2). Using the IMMPACT definition of substantial benefit, gabapentin was superior to placebo in 13 studies with 2627 participants, 31% improving with gabapentin and 17% with placebo; the NNT was 6.8 (5.6 to 8.7). These estimates of efficacy are more conservative than those reported in a previous review. Data from few studies and participants were available for other painful conditions.

Adverse events occurred significantly more often with gabapentin. Persons taking gabapentin can expect to have at least one adverse event (66%), withdraw because of an adverse event (12%), suffer dizziness (21%), somnolence (16%), peripheral oedema (8%), and gait disturbance (9%). Serious adverse events (4%) were no more common than with placebo.

There were insufficient data for comparisons with other active treatments.

Authors’ conclusions

Gabapentin provides pain relief of a high level in about a third of people who take if for painful neuropathic pain. Adverse events are frequent, but mostly tolerable. More conservative estimates of efficacy resulted from using better definitions of efficacy outcome at higher, clinically important, levels, combined with a considerable increase in the numbers of studies and participants available for analysis.

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH): Amines [adverse effects; *therapeutic use], Analgesics [adverse effects; *therapeutic use], Chronic Disease, Cyclohexanecarboxylic Acids [adverse effects; *therapeutic use], Fibromyalgia [*drug therapy], Neuralgia [*drug therapy], Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, gamma-Aminobutyric Acid [adverse effects; *therapeutic use]

MeSH check words: Humans

BACKGROUND

This new review is an update of a previous Cochrane review titled ‘Gabapentin for acute and chronic pain’ (Wiffen 2005), which was an extension to a review previously published in The Cochrane Library on ‘Anticonvulsant drugs for acute and chronic pain’ (Wiffen 2011a). The effects of gabapentin in established acute postoperative pain have been published as a separate review in 2010 (Straube 2010).

The decision to split the review was undertaken after discussions with the Editor-in-Chief of The Cochrane Collaboration at a meeting in Oxford in early 2009. That meeting was in response to controversy in the USA over the effectiveness of gabapentin as an analgesic (Landefeld 2009) together with calls for the 2005 review to be updated with the inclusion of unpublished information made available through litigation (Vedula 2009). It was agreed to update the review by splitting the earlier one into two components: this review looking at the role of gabapentin in chronic neuropathic pain (including neuropathic pain of any cause, and fibromyalgia), and a second one to determine the effects of gabapentin in acute postoperative pain (Straube 2010). Other reviews may examine gabapentin in chronic musculoskeletal pain. Since the earlier review was published in 2005, unpublished data have been released by the licence holders of the first gabapentin product to be marketed, and these data have been included in this updated review.

Description of the condition

Chronic pain is a major health problem affecting one in five people in Europe (Breivik 2006). Chronic pain is usually defined by a period of about three to six months during which pain is felt every day or almost every day. Any pain that is not chronic is acute, though there are always special circumstances, using these definitions, where either or neither are entirely satisfactory. Data for the incidence of neuropathic pain (pain resulting from a disturbance of the central or peripheral nervous system) are difficult to obtain. Estimates in the UK indicate incidences per 100,000 person-years observation of 40 (95% confidence interval (CI) 39 to 41) for postherpetic neuralgia, 27 (26 to 27) for trigeminal neuralgia, 1 (1 to 2) for phantom limb pain, and 15 (15 to 16) for painful diabetic neuropathy, with rates decreasing in recent years for phantom limb pain and postherpetic neuralgia and increasing for painful diabetic neuropathy (Hall 2006). The prevalence of neuropathic pain in Austria was reported as being 3.3% (Gustorff 2008), 6.9% in France (Bouhassira 2008), and in the UK as high as 8% (Torrance 2006).

Antiepileptic drugs (also known as anticonvulsants) have been used in pain management since the 1960s, very soon after they were first used for their original indication. The clinical impression is that they are useful for neuropathic pain, especially when the pain is lancinating or burning (Jacox 1994). There is evidence for the effectiveness of a number of antiepileptics including carbamazepine, pregabalin, phenytoin and valproate; these have been considered in other reviews published by the Cochrane Pain, Palliative and Supportive Care review group (Moore 2009a; Wiffen 2005; Wiffen 2011a; Wiffen 2011b). The use of antiepileptic drugs in chronic pain has tended to be confined to neuropathic pain (like painful diabetic neuropathy), rather than nociceptive pain (like arthritis). Antepileptics are sometimes prescribed in combination with antidepressants, as in the treatment of postherpetic neuralgia (Monks 1994). In the UK carbamazepine and phenytoin are licensed for the treatment of pain associated with trigeminal neuralgia, and gabapentin and pregabalin more generally for the treatment of neuropathic pain, though licensed indications vary in different parts of the world.

Description of the intervention

Gabapentin (original trade name Neurontin) is licensed for the treatment of peripheral and central neuropathic pain in adults in the UK at doses up to 3.6 grams (3600 mg) daily. It is given orally, as tablets or capsules. Guidance suggests that gabapentin treatment can be started at a dose of 300 mg per day for treating neuropathic pain. Based on individual patient response and tolerability, the dosage may be increased by 300 mg per day until pain relief (or intolerable adverse effects) is experienced (EMC 2009). US marketing approval for gabapentin was granted in 2002 for postherpetic neuralgia; in Europe, the label was changed to include peripheral neuropathic pain in 2006. Gabapentin is also now available as generic products in some parts of the world.

How the intervention might work

Gabapentin is thought to act by binding to calcium channels and modulating calcium influx as well as influencing GABAergic neurotransmission (i.e. neurotransmission affected by gabapentin). This mode of action confers antiepileptic, analgesic and sedative effects. The most recent research indicates that gabapentin acts by blocking new synapse formation (Barres 2009).

Why it is important to do this review

Gabapentin is widely prescribed for neuropathic pain and it is common practice in some countries to aim for the maximum tolerated dose. There is growing controversy over whether this practice is justified by experimental evidence from double-blind randomised trials.

Neuropathic pain is a complex and often disabling condition in which many people suffer moderate or severe pain for many years. Conventional analgesics are usually not effective in alleviating the symptoms, though opioids may be effective in some individuals. Treatment is usually by unconventional analgesics such as antidepressants or antiepileptics. The reason is that neuropathic pain, unlike nociceptive pain (pain that arises from nerve endings detecting unpleasant or painful stimuli), such as arthritis, or gout, is caused by nerve damage, often accompanied by changes in the central nervous system.

There have been several changes in how efficacy of both conventional and unconventional treatments is assessed in chronic painful conditions. The outcomes used today are better defined, particularly with new criteria of what constitutes moderate or substantial benefit (Dworkin 2008); older trials may only report participants with ‘any improvement’. Newer trials tend to be larger, avoiding problems from the random play of chance. Newer trials also tend to be longer, up to 12 weeks, and longer trials provide a more rigorous and valid assessment of efficacy in chronic conditions. New standards have evolved for assessing efficacy in neuropathic pain, we are now applying stricter criteria for inclusion of trials and assessment of outcomes, and we are more aware of problems that may affect our overall assessment.

To summarise, some of the recent insights into studies in neuropathic pain and chronic pain more generally that make a new review necessary, over and above including more trials are:

Pain relief results tend to have a U-shaped distribution rather than a bell-shaped distribution, with participants either achieving very good levels of pain relief, or little or none. This is the case for acute pain (Moore 2005a), fibromyalgia (Straube 2010), and arthritis (Moore 2009b); in all cases average results usually describe the actual experience of almost no-one in the trial. Continuous data expressed as averages should be regarded as potentially misleading, unless it can be proved to be suitable. Systematic reviews now frequently report results for responders (Lunn 2009; Moore 2010a; Straube 2008; Sultan 2008).

This means we have to depend on dichotomous results usually from pain changes or patient global assessments. The IMMPACT group has helped with their definitions of minimal, moderate, and substantial improvement (Dworkin 2008). In arthritis, trials shorter than 12 weeks, and especially those shorter than eight weeks, overestimate the effect of treatment (Moore 2009b); the effect is particularly strong for less effective analgesics. What is not always clear is how withdrawals are reported. Withdrawals can be high in some chronic pain conditions (Moore 2005b; Moore 2010b).

The proportion with at least moderate benefit can be small, falling from 60% with an effective medicine in arthritis, to 30% in fibromyalgia (Moore 2009b; Straube 2008; Sultan 2008). A Cochrane Review of pregabalin in neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia demonstrated different response rates for different types of chronic pain (higher in diabetic neuropathy and postherpetic neuralgia and lower in central pain and fibromyalgia) (Moore 2009a). This indicates that different neuropathic pain conditions should be treated separately from one another, and that pooling should not be done unless there are good grounds for doing so.

Finally, individual patient analyses indicate that patients who get clinically useful pain relief (moderate or better) have major benefits in many other outcomes, affecting quality of life in a major way (Hoffman 2010; Moore 2010c). Good response to pain predicts good effects for other troublesome symptoms like sleep, fatigue and depression.

These are by no means the only issues of trial validity that have been raised recently. A summary of what constitutes evidence in trials and reviews in chronic pain has been published (Moore 2010d), and this review has attempted to address all of them, so that the review is consistent with current best practice.

This Cochrane Review concentrates on evidence in ways that make both statistical and clinical sense. Studies included and analysed meet a minima of reporting quality (blinding, randomisation), validity (duration, dose and timing, diagnosis, outcomes, etc.), and size (ideally a minimum of 500 participants in a comparison with the Number needed to treat to benefit (NNTs) of four or greater (Moore 1998)).

This review covers chronic neuropathic pain (including fibromyalgia), concentrating for efficacy on dichotomous responder outcomes. We consider conditions individually, as there is evidence of different effects in different neuropathic pain conditions for some interventions like pregabalin (Moore 2009a), though less so for others (Lunn 2009). The review also considers additional risks of bias. These include issues of withdrawal (Moore 2010b), size (Moore 1998; Nuesch 2010), and duration (Moore 2010a) in addition to standard risks of bias.

OBJECTIVES

To assess the analgesic efficacy of gabapentin for chronic neuropathic pain.

To assess the adverse effects associated with the clinical use of gabapentin for chronic neuropathic pain.

METHODS

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included studies in this review if they were randomised controlled trials (RCTs) with double-blind (participant and observers) assessment of participant-reported outcomes, following two weeks of treatment or longer, though the emphasis of the review is on studies of 6 weeks or longer. Full journal publication was required, with the exception of extended abstracts of otherwise unpublished clinical trials (for example detailed information from PDFs of posters that typically include all important details of methodology used and results obtained). We did not include short abstracts (usually meeting reports with inadequate or no reporting of data). We excluded studies of experimental pain, case reports, and clinical observations.

Types of participants

We included adult participants aged 18 years and above. Participants could have one or more of a wide range of chronic neuropathic pain conditions including (but not limited to):

painful diabetic neuropathy (PDN);

postherpetic neuralgia (PHN);

trigeminal neuralgia;

phantom limb pain;

postoperative or traumatic neuropathic pain;

complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS);

cancer-related neuropathy;

HIV-neuropathy;

spinal cord injury;

fibromyalgia.

We also included studies of participants with more than one type of neuropathic pain. We analysed results according to the primary condition.

Types of interventions

Gabapentin in any dose, by any route, administered for the relief of neuropathic pain and compared to placebo, no interventionor any other active comparator. We did not include studies using gabapentin to treat pain resulting from the use of other drugs.

Types of outcome measures

Studies had to report pain assessment as either a primary or secondary outcome.

A variety of outcome measures were used in the studies. The majority of studies used standard subjective scales for pain intensity or pain relief, or both. Particular attention was paid to IMMPACT definitions for moderate and substantial benefit in chronic pain studies (Dworkin 2008). These are defined as at least 30% pain relief over baseline (moderate), at least 50% pain relief over baseline (substantial), much or very much improved on Patient Global Impression of Change (PGIC) (moderate), and very much improved on PGIC (substantial). These outcomes are different from those set out in the previous review, concentrating on dichotomous outcomes where pain responses do not follow a normal (Gaussian) distribution. People with chronic pain desire high levels of pain relief, ideally more than 50%, and with pain not worse than mild (O’Brien 2010).

Primary outcomes

Patient reported pain intensity reduction of 30% or greater.

Patient reported pain intensity reduction of 50% or greater.

Patient reported global impression of clinical change (PGIC) much or very much improved.

Patient reported global impression of clinical change (PGIC) very much improved.

Secondary outcomes

Any pain-related outcome indicating some improvement.

Withdrawals due to lack of efficacy.

Participants experiencing any adverse event.

Participants experiencing any serious adverse event.

Withdrawals due to adverse events.

Specific adverse events, particularly somnolence and dizziness.

During the updating process we discussed and reached consensus concerning a common core data set for pain reviews, and to reflect that we also used a working set of seven outcomes that might form a core data set. This overlapped to some extent with outcomes already identified:

at least 50% pain reduction;

proportion below 30/100 mm on a visual analogue scale (no worse than mild pain);

patient global impression;

functioning;

adverse event (AE) withdrawal;

serious AE;

death.

We considered the possibility of using these outcomes, but aside from functioning they were already included in primary and secondary outcomes chosen (with death noted as a serious adverse event).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

The following databases were searched:

the Cochrane Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library 2010, issue 12);

MEDLINE (via OVID) to January 2011; and

EMBASE (via OVID) to January 2011.

See Appendix 1 for the MEDLINE search strategy, Appendix 2 for the EMBASE search strategy, and Appendix 3 for the CENTRAL search strategy. All relevant articles found were identified on PubMed and using the ‘related articles’ feature, a further search was carried out for newly published articles.

There was no language restriction. All relevant articles found were identified on PubMed and using the ‘related articles’ feature, a further search was carried out for newly published articles.

Searching other resources

We searched reference lists of retrieved articles and reviews for any additional studies. We searched the PhRMA clinical study results database (www.clinicalstudyresults.org) for trial results of gabapentin in painful conditions.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

All potentially relevant studies identified by the search were read independently by two review authors to determine eligibility, and agreement reached by discussion. The studies were not anonymised in any way before assessment. All publications that could not clearly be excluded by screening the title and abstract were obtained in full and read.

Data extraction and management

Three review authors extracted data (RAM, PW, SD) using a standard data extraction form, and agreed data before entry into RevMan or any other analysis method. Data extracted included information about the pain condition and number of participants treated, drug and dosing regimen, study design, study duration and follow up, analgesic outcome measures and results, withdrawals and adverse events (participants experiencing any adverse event, or serious adverse event).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We used the ‘Risk of bias’ tool to assess the likely impact on the strength of the evidence of various study characteristics relating to methodological quality (randomisation, allocation concealment and blinding), study validity (duration, outcome reporting, and handling of missing data), and size (Appendix 4).

We also scored each report independently for quality using a three-item scale (Jadad 1996). We then met to agree a ‘consensus’ score for each report. Quality scores were not used to weight the results in any way.

The three-item scale is as follows:

Is the study randomised? If ‘yes’, then score one point.

If described, is the randomisation appropriate? If ‘yes’ then add one point, if not deduct one point.

Is the study double-blind? If ‘yes’, then add one point.

Is the double-blind method appropriate? If ‘yes’ then add one point, if not deduct one point.

Are withdrawals and drop-outs described? (i.e. the number and reason for drop-outs for each of the treatment groups).

If ‘yes’, then add one point.

Low quality scores of two and below have been associated with greater estimates of efficacy than studies of higher quality (Khan 1996).

Measures of treatment effect

Relative risk (or ‘risk ratio’, RR) was used to establish statistical difference. NNT and pooled percentages were used as absolute measures of benefit or harm.

The following terms are used to describe adverse outcomes in terms of harm or prevention of harm:

When significantly fewer adverse outcomes occurred with gabapentin than with control (placebo or active) we use the term the number needed to treat to prevent one event (NNTp).

When significantly more adverse outcomes occurred with gabapentin compared with control (placebo or active) we use the term the number needed to harm or cause one event (NNH).

Unit of analysis issues

The control treatment arm would be split between active treatment arms in a single study if the active treatment arms were not combined for analysis.

Dealing with missing data

We used intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis wherever possible. The ITT population consisted of participants who were randomised, took the assigned study medication and provided at least one post-baseline assessment. Missing participants were assigned zero improvement (baseline observation carried forward, BOCF) where this could be done. We were aware that imputation methods might be problematical and examined trial reports for information about them.

Assessment of heterogeneity

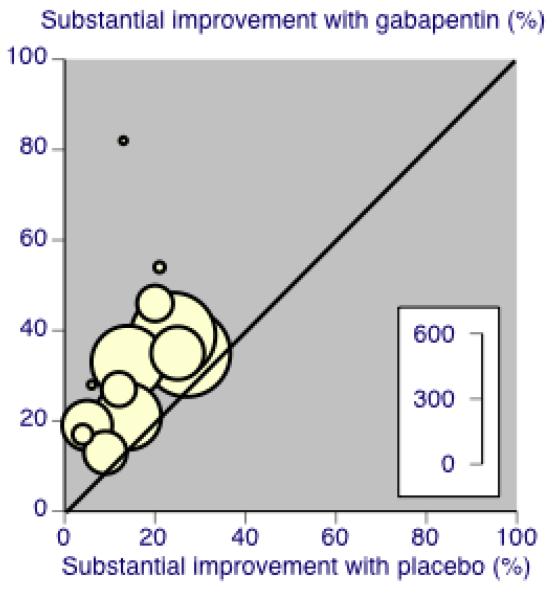

We dealt with clinical heterogeneity by combining studies that examined similar conditions. We assessed statistical heterogeneity visually (L’Abbe 1987) and with the use of the I2 statistic.

Assessment of reporting biases

The aim of this review was to use dichotomous data of known utility (Moore 2009b). The review did not depend on what authors of the original studies chose to report or not report, though clearly there were difficulties with studies failing to report any dichotomous results. Continuous data, which probably poorly reflect efficacy and utility, were extracted and used only when useful for illustrative purposes.

We undertook no statistical assessment of publication bias.

We looked for effects of possible enrichment, either complete or partial, in enrolment of participants into the studies. Enrichment typically means including participants known to respond to a therapy, and excluding those known not to respond, or to suffer unacceptable adverse effects, though for gabapentin no significant effects have been shown from partial enrichment (Straube 2008). Enriched enrolment randomised withdrawal studies, known to produce higher estimates of efficacy, would not be pooled (McQuay 2008).

Data synthesis

We used dichotomous data to calculate relative risk or benefit (risk ratio) with 95% CIs using a fixed-effect model, together with NNTs (Cook 1995). This was done for effectiveness, for adverse effects and for drug-related study withdrawal. We also undertook meta-analysis when sufficient clinically similar data were available. We calculated NNTs as the reciprocal of the absolute risk reduction (McQuay 1998). For unwanted effects, the NNT becomes the NNH (number needed to treat to harm), and is calculated in the same way. In the absence of dichotomous data, summary continuous data are reported where available and appropriate, but no analysis was carried out.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned subgroup analysis for:

dose of gabapentin;

duration of studies; and

different painful conditions.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned no sensitivity analyses because the evidence base was known to be too small to allow reliable analysis.

RESULTS

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies.

In this split update of the original review (Wiffen 2005) we made no attempt to contact authors or manufacturers of gabapentin. Clinical trial reports or synopses from previously unpublished studies became available as a result of legal proceedings in the USA. In the previous update, an author confirmed that one study was randomised but could provide no additional data (Perez 2000).

Included studies

The original chronic pain review included 14 studies with 1392 participants in 13 reports. Two of those studies were excluded in this review update: one postherpetic neuralgia (PHN) study because it was open (Dallocchio 2000), and one in Guillain Barré syndrome because it is now not considered to be a chronic neuropathic pain condition (Pandey 2002). Furthermore, the second of two studies in painful diabetic neuropathy (PDN) reported inSimpson 2001 was not considered because it was a test of additional venlafaxine, not of gabapentin.

An additional 18 studies with 2263 participants were included, bringing the total to 29 studies in 29 reports, involving 3571 participants. A number of chronic painful conditions were studied:

Postherpetic neuralgia; five studies, 1197 participants (Chandra 2006; Irving 2009; Rice 2001; Rowbotham 1998;Wallace 2010).

Painful diabetic neuropathy; eight studies, 1183 participants (Backonja 1998; CTR 945-1008; CTR 945-224;Gorson 1999; Morello 1999; Perez 2000; Sandercock 2009;Simpson 2001).

Mixed neuropathic pain; three studies, 418 participants (Gilron 2005; Gilron 2009; Serpell 2002).

Fibromyalgia; one study, 150 participants (Arnold 2007).

Complex regional pain syndrome type I; one study, 58 participants (van de Vusse 2004).

Spinal cord injury pain; three studies, 65 participants (Levendoglu 2004; Rintala 2007; Tai 2002).

Nerve injury pain; one study, 120 participants (Gordh 2008).

Phantom limb pain; two studies, 43 participants (Bone 2002; Smith 2005).

Cancer-related neuropathic pain; two studies, 236 participants (Caraceni 2004; Rao 2007).

HIV painful sensory neuropathy; one study, 26 participants (Hahn 2004).

Masticatory myalgia; one study, 50 participants (Kimos 2007).

Small fibre sensory neuropathy; one study, 54 participants (Ho 2009).

Three quarters of the participants (2398) were enrolled in studies of PHN, PDN, or mixed neuropathic pain. The other nine neuropathic pain conditions were studied in 802 participants, with the largest numbers in cancer-related neuropathic pain (236 participants), fibromyalgia (150) and nerve injury pain (120).

Sixteen of the studies had a parallel-group design and 13 had a cross-over design (Bone 2002; Gilron 2005; Gilron 2009; Gordh 2008; Gorson 1999; Ho 2009; Levendoglu 2004; Morello 1999;Rao 2007; Rintala 2007; Smith 2005; Tai 2002; van de Vusse 2004). We used whatever data were available from cross-over studies, including first period or multiple periods, though there are major issues with what constitutes the intention-to-treat (ITT) denominator where there are significant withdrawals.

Parallel-group trials were larger than cross-over trials. The 16 parallel-group studies involved 2967 participants (mean 185, median 154 participants, range 26 to 400), while the 13 cross-over studies involved 633 participants (mean 49, median 40 participants, range 7 to 120). Not all studies reported the results on an ITT basis, and this was particularly the case for cross-over studies with multiple comparisons.

Twenty-one studies either described enrolment processes that were not enriched, or had no exclusion criteria that would raise the possibility of enrichment (Straube 2008). Six studies were partially enriched (Caraceni 2004; Irving 2009; Rice 2001; Rowbotham 1998; Serpell 2002) or had previous treatment with gabapentin or pregabalin as an exclusion criterion, which may have led to enrichment (Arnold 2007; Wallace 2010). One study had complete enrichment (Ho 2009).

Twenty-five studies either made no mention of an imputation method for missing data (19) or declared use of last observation carried forward (LOCF) (6). Others performed analyses on completers only (van de Vusse 2004), one presented results without imputation (Rao 2007), and in one we could not decide how data had been treated (Ho 2009).

Details of all eligible studies are given in the ‘Characteristics of included studies’ table.

Excluded studies

Several other studies were considered but excluded for various reasons. These included open studies (Arai 2010; Dallochio 2000; Jean 2005; Keskinbora 2007; Ko 2010; Salvaggio 2008;Sator-Katzenschlager 2005; Yaksi 2007), studies in chronic conditions not considered for this review (McCleane 2001; Pandey 2002; Pandey 2005; Sator-Katzenschlager 2005; Yaksi 2007), acute treatment of herpes zoster (Berry 2005; Dworkin 2009), and trials in surgery to prevent chronic phantom pain (Nikolajsen 2006). We also excluded an n-of-1 study in chronic neuropathic pain (Yelland 2009) with complete enrichment, high withdrawals, and short (two-week) treatment periods because this design is rare and interpretation very difficult. Details of excluded studies are given in the ‘Characteristics of excluded studies’ table.

Risk of bias in included studies

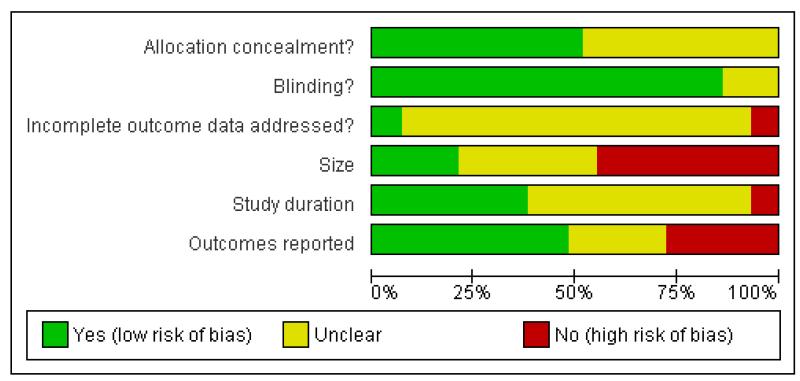

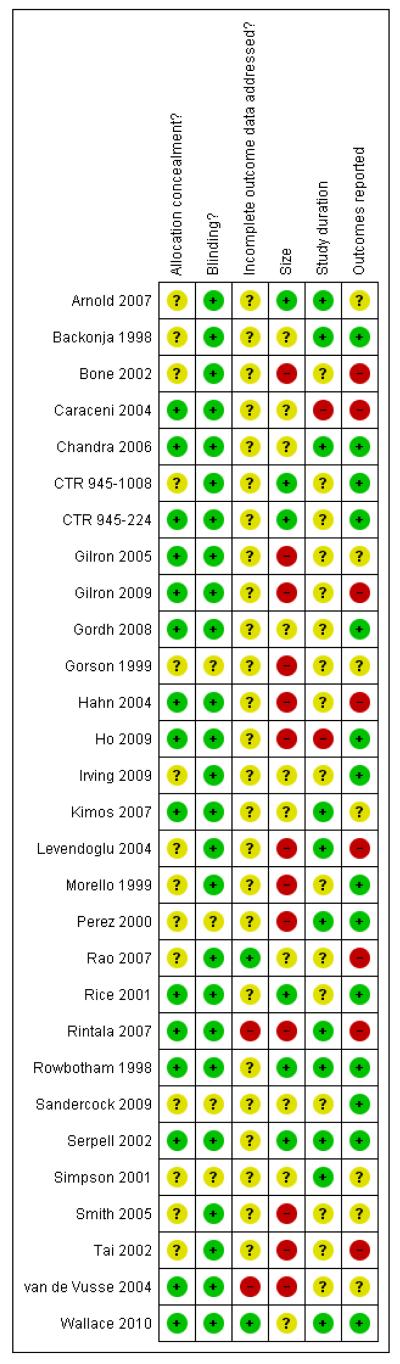

Reporting quality was largely good. On the five point Oxford Scale addressing randomisation, blinding, and withdrawals, two studies scored 2/5 points, two 3/5 points, eight 4/5 points, and 17 5/5 points. Studies with scores of 3/5 and above are considered unlikely to be subject to major systematic bias (Khan 1996). Points were lost mainly for inadequate descriptions of randomisation. The risk of bias assessments (Figure 1; Figure 2) emphasised this, with adequate sequence generation and allocation concealment being most often inadequately reported. Additional risk of bias also derived from studies being small, reporting unhelpful outcomes, rarely describing how efficacy data were handled on withdrawal, and being of short duration.

Figure 1.

Methodological quality graph: review authors’ judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Figure 2.

Methodological quality summary: review authors’ judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Effects of interventions

Appendix 5 contains details of withdrawals, efficacy, and adverse events in the individual studies.

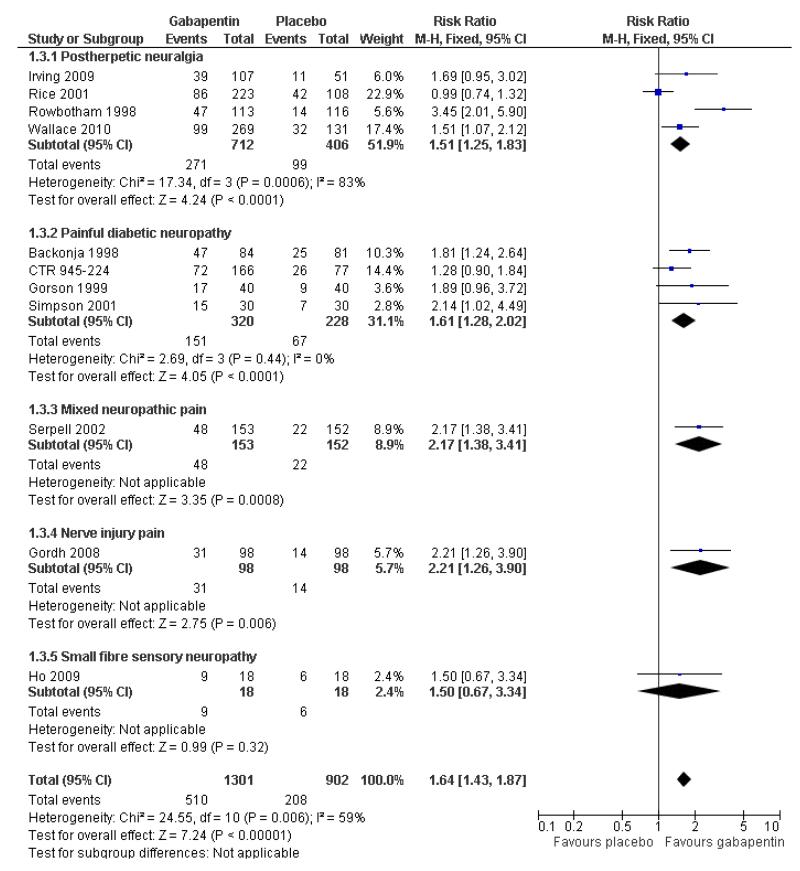

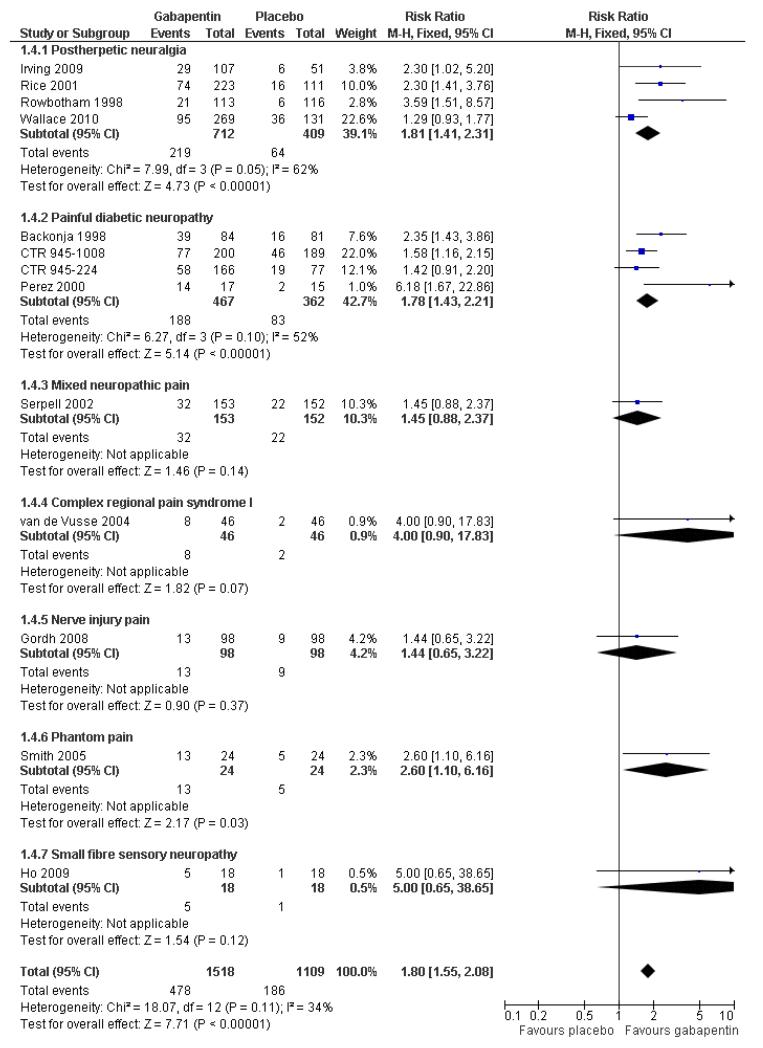

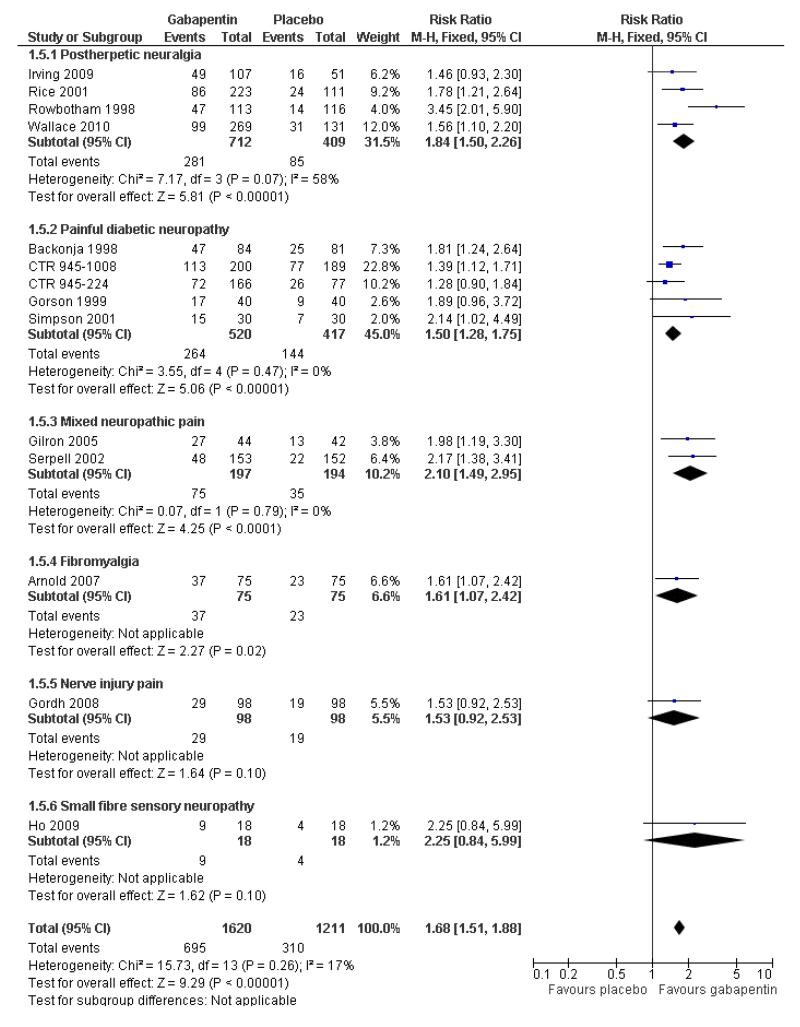

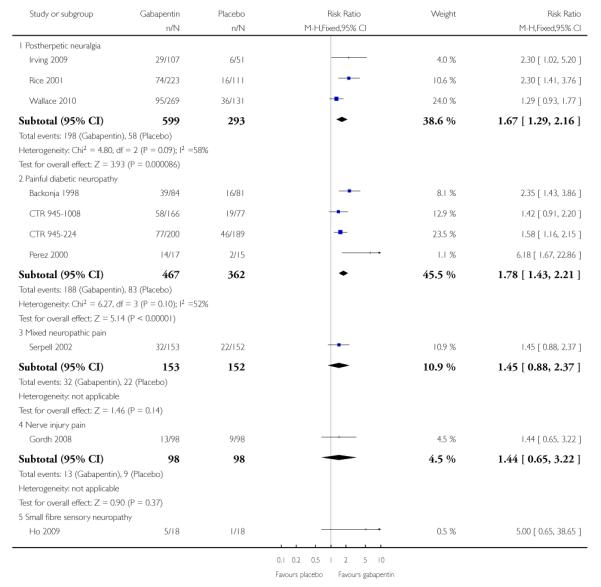

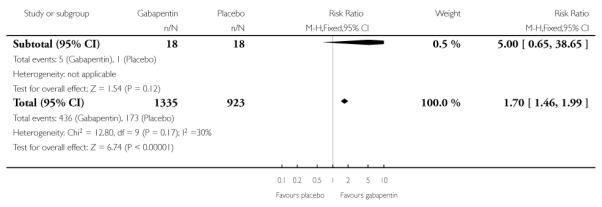

Efficacy outcomes

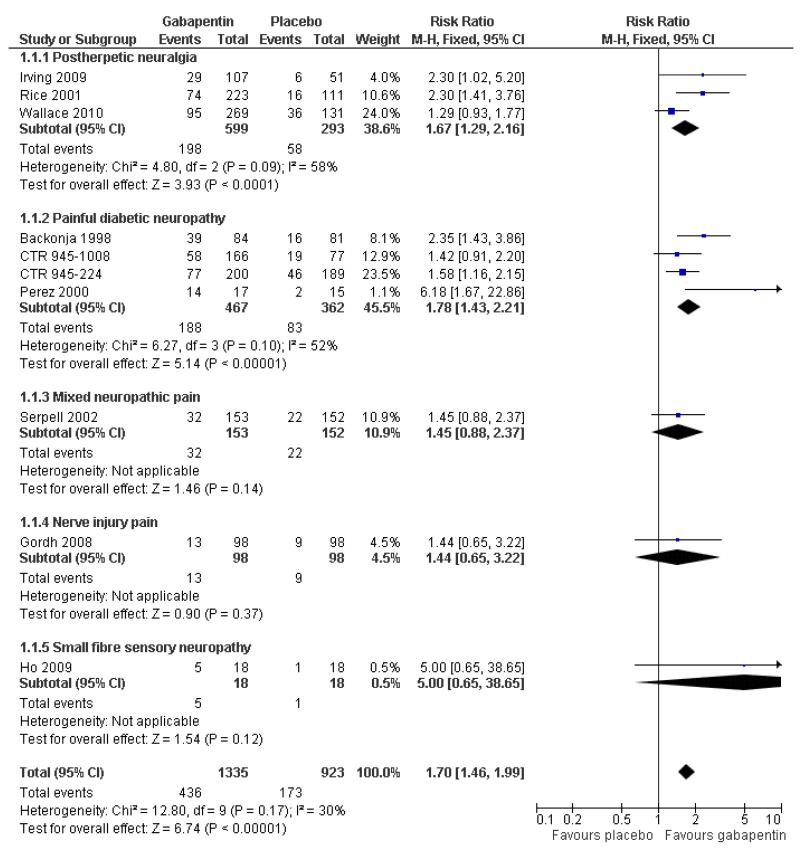

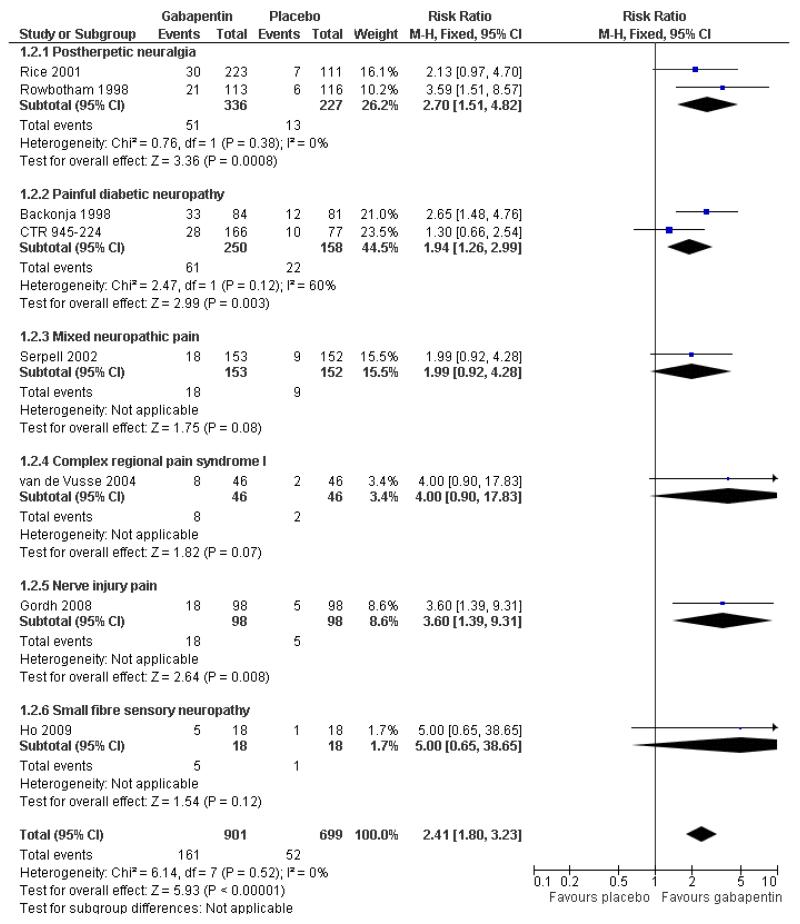

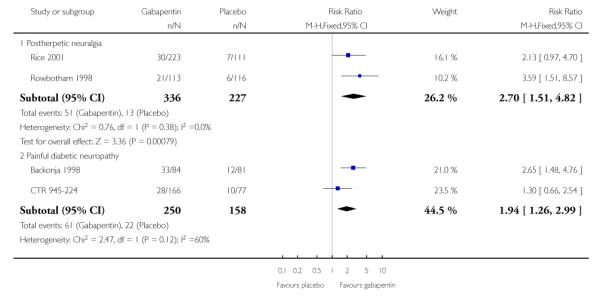

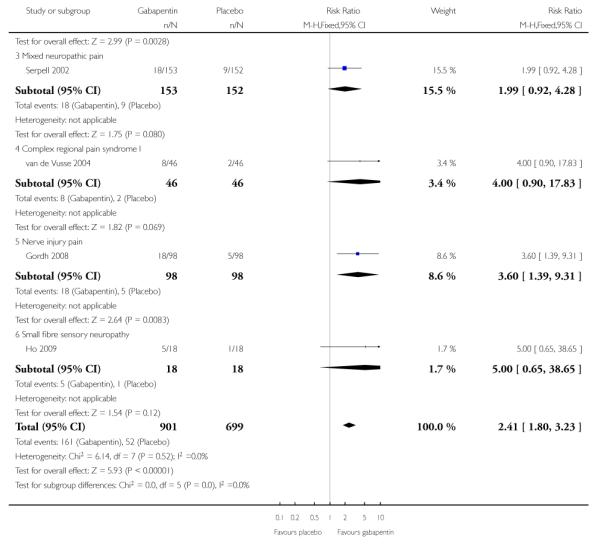

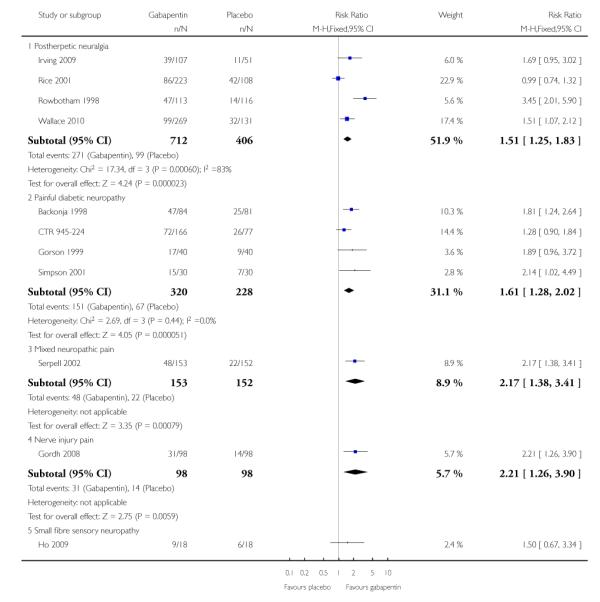

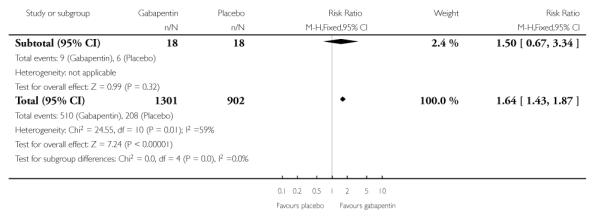

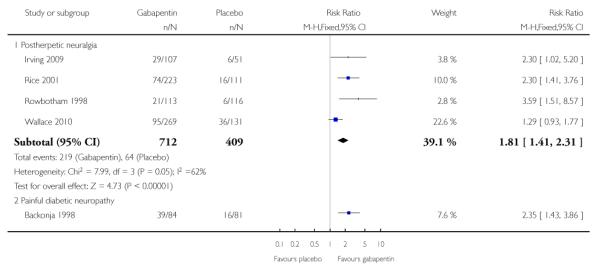

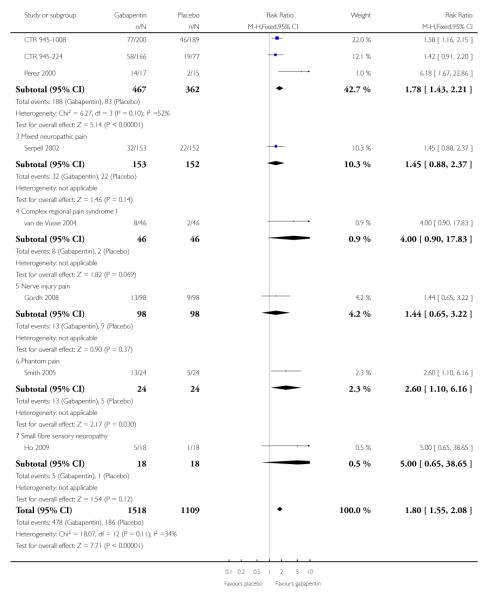

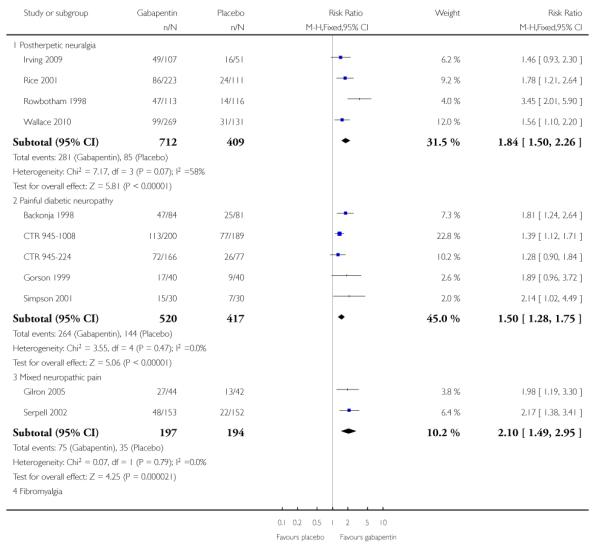

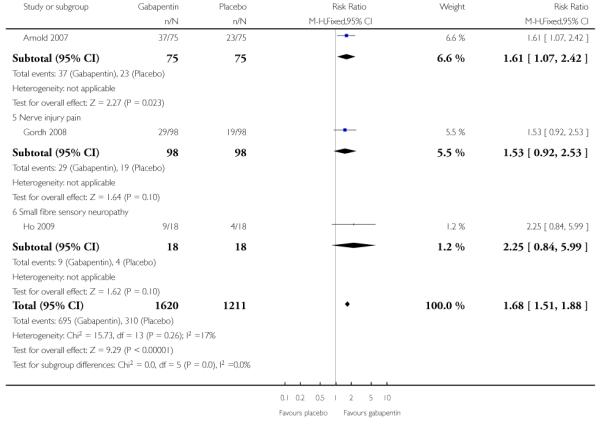

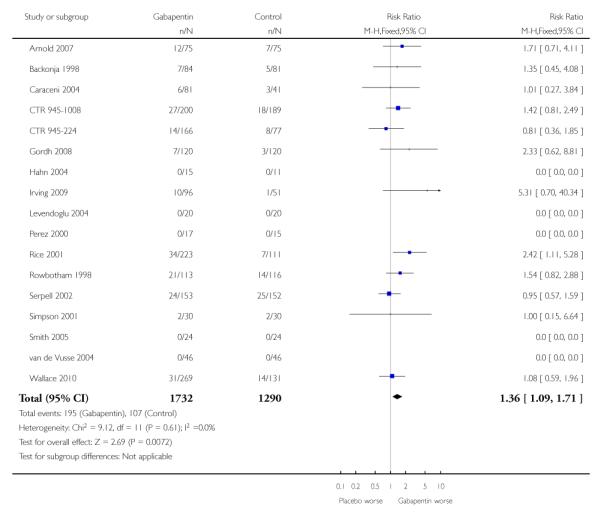

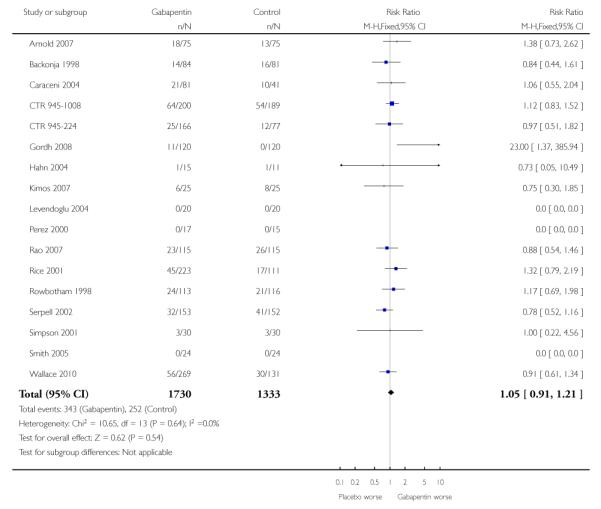

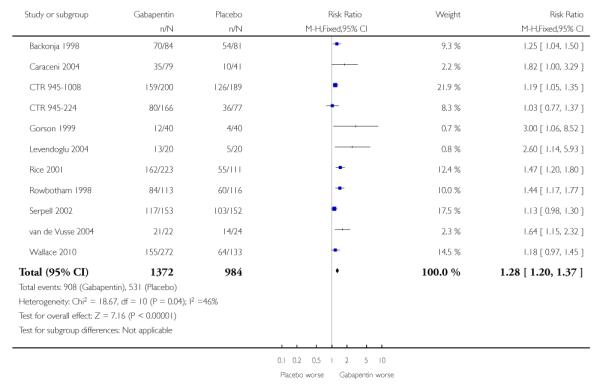

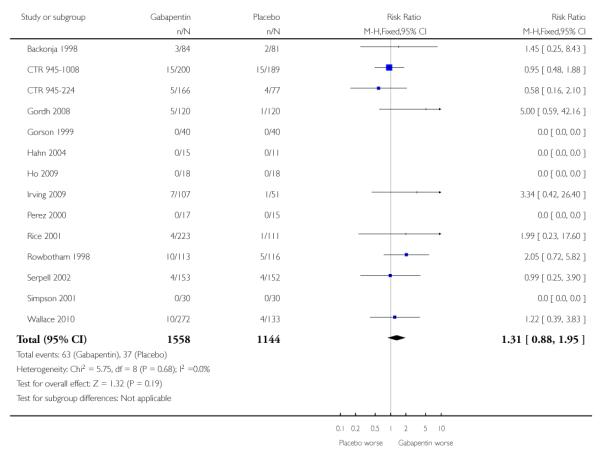

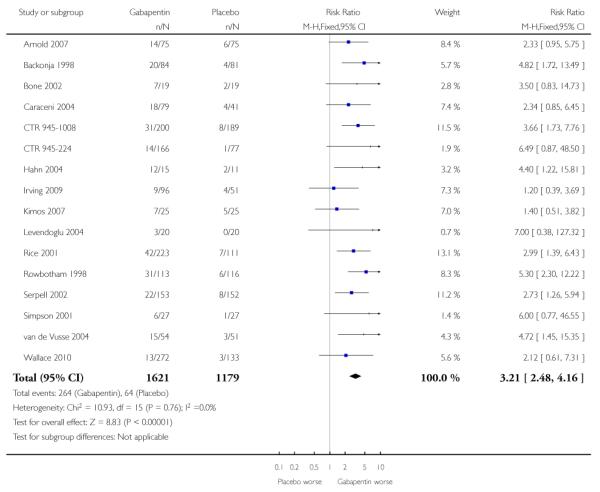

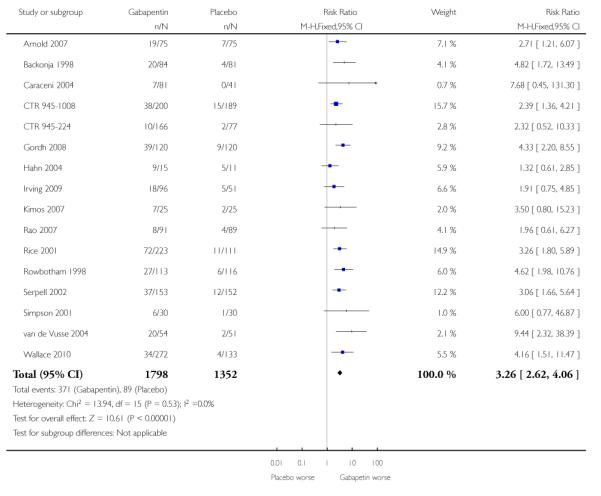

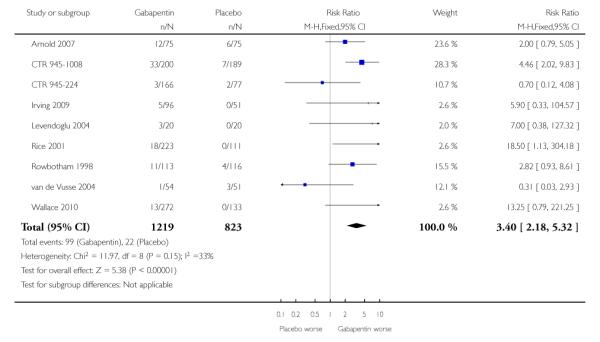

Analyses 1.1 to 1.5 show results for the following outcomes: at least 50% reduction in pain (Analysis 1.1; Figure 3); PGIC very much improved (Analysis 1.2; Figure 4); PGIC much or very much improved (Analysis 1.3; Figure 5); IMMPACT outcome of substantial improvement in pain (Analysis 1.4; Figure 6); IMMPACT outcome of at least moderate improvement in pain (Analysis 1.5; Figure 7).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 All placebo-controlled studies, outcome: 1.1 At least 50% pain reduction over baseline.

Figure 4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 All placebo-controlled studies, outcome: 1.2 Very much improved.

Figure 5.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 All placebo-controlled studies, outcome: 1.3 Much or very much improved.

Figure 6.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 All placebo-controlled studies, outcome: 1.4 IMMPACT outcome of substantial improvement.

Figure 7.

Percentage of participants achieving outcomes equivalent to IMMPACT at least moderate improvement, all doses, all conditions

Postherpetic neuralgia (PHN)

Of the five studies in PHN, four (Irving 2009; Rice Rowbotham 1998; Wallace 2010) had a placebo control only, one (Chandra 2006) an active control only. All four trolled studies had a parallel-group design, with study of four, seven, eight, and 10 weeks respectively; daily gabapentin doses varied between 1800 mg and 3600 mg.

A number of outcomes consistent with IMMPACT recommendations for substantial and moderate benefit were reported in two or more placebo-controlled studies, and the results showed gabapentin at doses of 1800 mg daily or more to be more effective than placebo (Summary of results A). For a PGIC (Patient Global Impression of Change) of much or very much improved; 39% of participants achieved this level of improvement with gabapentin and 18% with placebo. There were insufficient data for subgroup analyses based on dose or duration of studies.

Summary of results A: Efficacy outcomes with gabapentin in postherpetic neuralgia

| Number of | Percent with outcome | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Studies | Participants | Gabapentin | Placebo | Risk ratio (95% CI) | NNT (95% CI) |

| Substantial benefit | ||||||

| At least 50% pain relief | 3 | 892 | 33 | 20 | 1.7 (1.3 to 2.2) | 7.5 (5.2 to 14) |

| PGIC very much improved | 2 | 563 | 15 | 6 | 2.7 (1.5 to 4.8) | 11 (7.0 to 22) |

| Moderate benefit | ||||||

| PGIC much or very much improved | 4 | 1121 | 38 | 20 | 1.9 (1.5 to 2.3) | 5.5 (4.3 to 7.7) |

In the active controlled study involving 76 participants, gabapentin at doses of up to 2700 mg daily was compared to nortriptyline at doses of up to 150 mg daily over nine weeks. At least 50% improvement in pain over baseline using a VAS pain scale was achieved by 13/38 (34%) on gabapentin and 14/38 (37%) on nortriptyline, broadly in line with event rates in placebo-controlled studies (Chandra 2006).

Painful diabetic neuropathy (PDN)

Six of the eight studies in PDN were of parallel-group design (Backonja 1998; CTR 945-1008; CTR 945-224; Perez 2000;Sandercock 2009; Simpson 2001); two had a cross-over design (Gorson 1999; Morello 1999). Seven had a placebo comparator only, while one (Morello 1999) had an active control only. Six placebo-controlled parallel-group studies had a study duration between four and 14 weeks; all but one (Sandercock 2009) of seven weeks or longer. Daily gabapentin doses varied between 600 mg and 3600 mg; doses below 1200 mg were used in two studies, 900 mg daily as the only gabapentin dose in one (Gorson 1999), and 600 mg daily in one arm of another (CTR 945-224).

A number of outcomes consistent with IMMPACT recommendations for substantial and moderate benefit were reported in two or more placebo-controlled studies, and the results showed gabapentin at doses of 1200 mg daily or more to be more effective than placebo (Summary of results B). For PGIC much or very much improved; 43% of participants achieved this level of improvement with gabapentin and 31% with placebo, with very similar results when results from Simpson 2001 were omitted because of concerns one reviewer expressed about this study; no other efficacy outcome included data from this study. For the largest data set of at least 50% pain relief over baseline, there was consistency between studies (Figure 8). There were insufficient data for subgroup analyses based on dose or duration of studies.

Figure 8.

Painful diabetic neuropathy: Percentage of participants achieving at least 50% pain relief over baseline with gabapentin 1200-3600 mg daily, or placebo

Summary of results B: Efficacy outcomes with gabapentin in painful diabetic neuropathy (1200 mg daily or greater)

| Number of | Percent with outcome | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Studies | Participants | Gabapentin | Placebo | Risk ratio (95% CI) | NNT (95% CI) |

| Substantial benefit | ||||||

| At least 50% pain relief | 4 | 829 | 40 | 23 | 1.8 (1.4 to 2.2) | 5.8 (4.3 to 9.0) |

| PGIC very much improved | 2 | 408 | 24 | 14 | 1.9 (1.3 to 3.0) | 9.6 (5.5 to 35) |

| Moderate benefit | ||||||

| PGIC much or very much improved | 3 | 466 | 43 | 31 | 1.5 (1.1 to 1.9) | 8.1 (4.7 to 28) |

| PGIC much or very much improved (excluding Simpson 2001) | 2 | 406 | 42 | 32 | 1.4 (1.1 to 1.8) | 9.9 (5.1 to 190) |

One other placebo-controlled study indicated that 41% of participants taking gabapentin 3000 mg daily achieved at least 50% reduction in average daily pain over four weeks compared with 12% with placebo (Sandercock 2009), but without giving the numbers of participants in each study treatment arm. Gabapentin 600 mg daily produced lesser effects than 1200 mg and 2400 mg daily in a study that compared them (CTR 945-224). In one placebo-controlled cross-over study involving 40 randomised participants, moderate or excellent pain relief was achieved by 17/40 (43%) with gabapentin 900 mg daily over six weeks, compared with 9/ 40 (23%) with placebo (Gorson 1999).

In one active controlled study involving 25 participants, gabapentin at 1800 mg daily was compared to amitriptyline 75 mg daily over six weeks. Complete or a lot of pain relief was achieved by 6/21 (29%) with gabapentin and 5/21 (24%) with amitripty-line (Morello 1999).

Mixed neuropathic pain

Three studies examined the effects of gabapentin in mixed neuropathic painful conditions (Gilron 2005; Gilron 2009; Serpell 2002); two included participants with PHN and PDN (Gilron 2005; Gilron 2009) and in the other the most common conditions were complex regional pain syndrome and PHN (Serpell 2002). One had a parallel-group comparison with placebo over eight weeks (Serpell 2002). The others had cross-over designs that included placebo and morphine alone and in combination with gabapentin over five weeks (Gilron 2005), and nortriptyline alone or in combination with gabapentin over six weeks (Gilron 2009). The parallel-group comparison with placebo (Serpell 2002) used gabapentin titrated to a maximum of 2400 mg daily in 305 participants. Only for the PGIC outcome of much or very much improved was there a significant benefit of gabapentin (Summary of results C).

Summary of results C: Efficacy outcomes with gabapentin in mixed neuropathic pain (Serpell 2002)

| Number of | Percent with outcome | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Studies | Participants | Gabapentin | Placebo | Risk ratio (95% CI) | NNT (95% CI) |

| At least 50% pain relief | 1 | 305 | 21 | 14 | 1.5 (0.9 to 2.4) | not calculated |

| PGIC very much improved | 1 | 305 | 12 | 6 | 2.0 (0.9 to 4.3) | not calculated |

| PGIC much or very much improved | 1 | 305 | 31 | 14 | 2.2 (1.4 to 3.4) | 5.9 (3.8 to 13) |

One placebo-controlled cross-over study (Gilron 2005) over five weeks provided results for moderate pain relief for participants who completed a given treatment period. Gabapentin alone (target dose 3200 mg daily), morphine alone (target dose 120 mg daily), and the combination (target dose gabapentin 2400 mg plus 60 mg morphine daily) were significantly better than placebo (Summary of results D). These results were calculated from the numbers and percentages with a moderate response. The total is larger than the 57 randomised, because some will have participated in more than one treatment arm.

Summary of results D: Efficacy outcomes with gabapentin in mixed neuropathic pain (Gilron 2005)

| Number of | Percent with outcome | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| At least moderate pain relief | Studies | Participants | Gabapentin | Placebo | Risk ratio (95% CI) | NNT (95% CI) |

| Gabapentin alone | 1 | 96 | 61 | 25 | 2.5 (1.5 to 4.2) | 2.8 (1.8 to 5.6) |

| Morphine alone | 1 | 96 | 80 | 25 | 3.2 (1.9 to 5.2) | 1.8 (1.4 to 2.7) |

| Gabapentin plus morphine | 1 | 93 | 78 | 25 | 3.1 (1.9 to 5.1) | 1.9 (1.4 to 2.8) |

The other cross-over study compared gabapentin alone (target dose 3600 mg daily), nortriptyline (target dose 100 mg daily) and the combination (target dose 3600 mg gabapentin plus 100 mg nortriptyline daily) over six weeks (Gilron 2009). Pain intensity was significantly lower with the combination, by less than one point out of 10 on a numerical rating pain scale.

Fibromyalgia

The efficacy of gabapentin in fibromyalgia at maximum doses of 2400 mg daily was compared with placebo in 150 participants in a single placebo (diphenhydramine) controlled parallel-group study lasting 12 weeks (Arnold 2007). The outcome of 30% reduction in pain over baseline was reported, with 38/75 participants (49%) achieving the outcome with gabapentin compared with 23/75 (31%) with placebo. The relative benefit was 1.6 (1.1 to 2.4) and the NNT was 5.4 (2.9 to 31).

Complex regional pain syndrome

The efficacy of gabapentin in complex regional pain syndrome at maximum doses of 1800 mg daily was compared with placebo in 58 participants in a single placebo-controlled cross-over study lasting three weeks in each period (van de Vusse 2004). Over both periods, and using per protocol reporting, “much” pain improvement (undefined) was achieved by 8/46 (17%) with gabapentin compared with 2/46 (4%) with placebo. There was no significant difference, with a relative benefit of 4.0 (0.9 to 18).

Spinal cord injury

The efficacy of gabapentin in spinal cord injury pain at maximum doses of 1800 mg or 3600 mg daily was compared with placebo in three cross-over trials (Levendoglu 2004; Rintala 2007; Tai 2002) over periods of four and eight weeks. None of the studies reported dichotomous outcomes equivalent to moderate or substantial pain relief.

One eight-week study randomised 20 participants to a maximum of 3600 mg gabapentin daily or placebo over eight weeks (Levendoglu 2004) and reported a 62% average fall in pain with gabapentin compared with a 13% fall with placebo.

A second eight-week study randomised 38 participants to a maximum of 3600 mg gabapentin daily, amitriptyline 150 mg daily, or placebo over eight weeks (Rintala 2007). It claimed statistical superiority for amitriptyline for the 22 participants completing all three phases, and no benefit of gabapentin over placebo.

The final study comparing gabapentin with placebo over four weeks in seven participants had no interpretable results (Tai 2002).

Nerve injury pain

A single cross-over study evaluated the efficacy of gabapentin at a maximum of 2400 mg daily compared with placebo over five-week treatment periods (Gordh 2008). Among the 98 participants of the 120 randomised and who completed both treatment periods, at least 50% pain relief was achieved by 13 (13%) on gabapentin and 9 (9%) on placebo, which did not reach statistical significance, risk ratio 1.4 (0.7 to 3.2). At least 30% pain relief was achieved by 29 (29%) on gabapentin and 19 (19%) on placebo, which did not reach statistical significance, risk ratio 1.5 (0.9 to 2.5).

Phantom limb pain

Two cross-over studies evaluated the efficacy of gabapentin compared with placebo in phantom limb pain (Bone 2002; Smith 2005). One (Bone 2002) randomised 19 participants to a maximum of 2400 mg gabapentin daily, or the maximum tolerated dose, with six-week treatment periods. Using an ITT approach, weekly VAS pain scores were lower at week six only with gabapentin, but not at any other time, nor with categorical pain measures. The other (Smith 2005) randomised 24 participants to gabapentin titrated to a maximum daily dose of 3600 mg. A “meaningful decrease in pain” (the top of a five-point scale) was achieved by 13 participants (54%) with gabapentin and 5 (21%) with placebo, a statistically significant difference, with risk ratio 2.6 (1.1 to 6.2).

Cancer-related neuropathic pain

Two studies examined gabapentin in the short term in cancer-related neuropathic pain (Caraceni 2004; Rao 2007). A parallel-group study (Caraceni 2004) randomised 121 participants to titration to a maximum of gabapentin 1800 mg daily or placebo, with 10 days of treatment. The average pain intensity was somewhat lower with gabapentin than with placebo, but the number of participants described as having pain under control was very similar with both treatments after six days, with 50% to 60% with pain under control over six to 10 days. A cross-over study (Rao 2007) compared gabapentin titrated to 2700 mg daily with placebo in chemotherapy-induced neuropathic pain over three weeks. There was no significant difference between gabapentin and placebo, but the study did recruit participants both with pain and sensory loss or paraesthesia, and baseline pain scores were only about 4/10 on a numerical rating scale. The study probably lacked sensitivity to detect any difference.

HIV-associated sensory neuropathies

A single parallel-group study compared gabapentin titrated to 2400 mg daily with placebo over four weeks in 24 participants with painful HIV-associated neuropathies (Hahn 2004). On average, pain and sleep improved substantially with gabapentin and placebo, though time courses differed.

Chronic masticatory myalgia

A single parallel-group study compared gabapentin titrated to 4200 mg daily with placebo over 12 weeks in 50 participants with painful chronic masticatory myalgia, where pain is associated with central sensitisation (Kimos 2007). Gabapentin was significantly better than placebo for VAS pain, pain reduction, and VAS function, and an NNT of 3.4 for gabapentin compared with placebo was reported, though no details were recorded about outcome.

Small fibre sensory neuropathies

A single cross-over study with complete enrichment, compared gabapentin at doses up to 4800 mg daily with tramadol 50 mg (probably four times a day), and placebo in 18 participants with small fibre sensory neuropathies using two-week treatment periods (Ho 2009). The number achieving at least 50% pain relief was 4/ 18 (22%) with gabapentin, 4/18 (22%) with tramadol, and 1/18 (6%) with placebo. Similar results were obtained for those feeling very much better.

Overall efficacy across all conditions

Assessing efficacy across all conditions was complicated by different reporting of outcomes, and the limited number of studies reporting the same outcome. This was possible for certain outcomes, including IMMPACT definitions of substantial and at least moderate improvement (Summary of results E). The following analyses include the single completely enriched study (Ho 2009), though this contributed 2% or fewer participants to the analyses, and its omission made no discernable difference to the results.

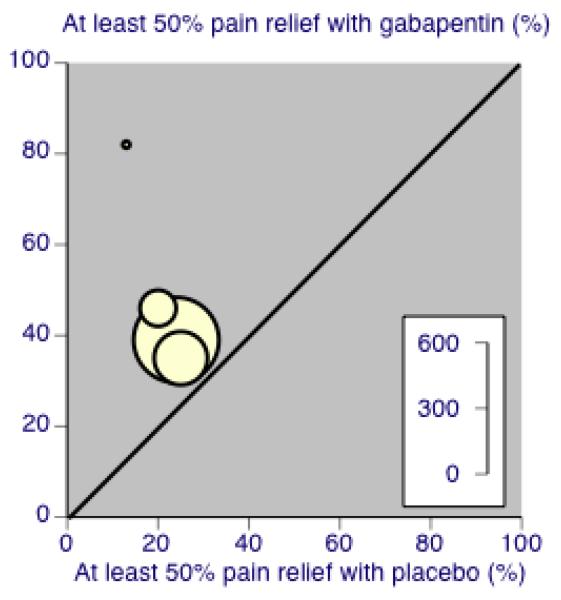

Nine studies with 1858 participants reported the outcome of at least 50% pain intensity reduction over baseline by the end of the study (Analysis 1.1; Figure 4). The outcome was achieved by 32% on gabapentin 1200 mg daily or greater, and 17% on placebo. The relative benefit was 1.8 (1.5 to 2.2) and the NNT 6.8 (5.4 to 9.2). Eight studies with 1600 participants reported the outcome equivalent to be very much improved (or top point on global rating scale) by the end of the study (Analysis 1.2; Figure 5). The outcome was achieved by 18% on gabapentin 1200 mg daily or greater, and 7% on placebo. The relative benefit was 2.4 (1.8 to 3.2) and the NNT 9.6 (7.4 to 14).

Ten studies with 1701 participants reported the outcome equivalent to be much or very much improved (or top two points on global rating scale) by the end of the study (Analysis 1.3; Figure 6). The outcome was achieved by 41% on gabapentin 1200 mg daily or greater, and 23% on placebo. The relative benefit was 1.7 (1.5 to 2.0) and the NNT 5.7 (4.6 to 7.6).

IMMPACT definitions (Summary of results E)

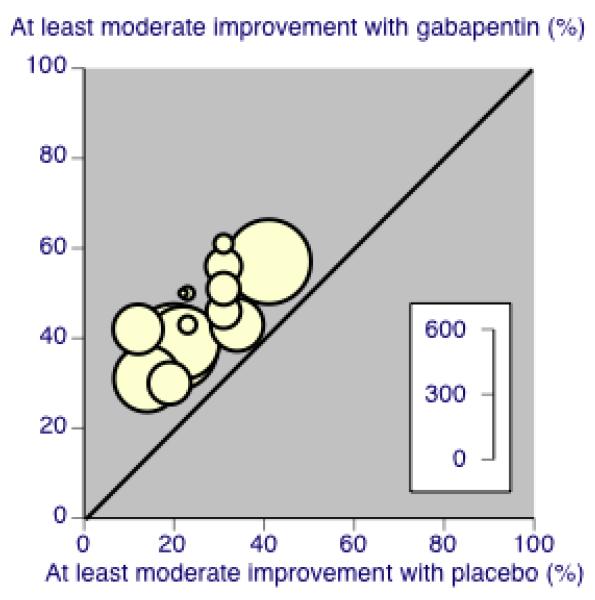

Two further analyses were conducted across all studies and all doses of gabapentin to assess efficacy according to IMMPACT definitions of substantial improvement (using at least 50% pain intensity reduction for preference over very much improved), and for moderate improvement (using at least 30% pain intensity reduction for preference over much or very much improved).

Twelve studies with 2227 participants reported the outcome equivalent to IMMPACT as “substantial” improvement by the end of the study (Analysis 1.4; Figure 6). The outcome was achieved by 31% on gabapentin 900 mg daily or greater, and 15% on placebo. The relative benefit was 1.9 (1.6 to 2.3) and the NNT 6.5 (5.3 to 8.4). Results were consistent across trials (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Percentage of participants achieving outcomes equivalent to IMMPACT substantial improvement, all doses, all conditions

Thirteen studies with 2431 participants reported the outcome equivalent to IMMPACT of “at least moderate” improvement by the end of the study (Analysis 1.5; Figure 10). The outcome was achieved by 44% on gabapentin 900 mg daily or greater, and 26% on placebo. The relative benefit was 1.7 (1.5 to 1.9) and the NNT 5.5 (4.5 to 6.8). Results were consistent across trials (Figure 7).

Figure 10.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 All placebo-controlled studies, outcome: 1.5 IMMPACT outcome of at least moderate improvement.

Subgroup analyses for both IMMPACT definitions limited to parallel-group studies lasting six weeks or more produced virtually identical results as those for the ‘all studies’ analysis that included cross-over studies, and those shorter than six weeks.

Summary of results E: Efficacy outcomes across all conditions

| Number of | Percent with outcome | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Studies | Participants | Gabapentin | Placebo | Risk ratio (95% CI) | NNT (95% CI) |

| Gabapentin doses 1200 mg daily or more | ||||||

| At least 50% pain relief | 10 | 2258 | 33 | 19 | 1.7 (1.5 to 2.0) | 7.2 (5.7 to 9.7) |

| PGIC very much improved | 8 | 1600 | 18 | 7 | 2.4 (1.8 to 3.2) | 9.6 (7.4 to 14) |

| PGIC much or very much improved | 11 | 2101 | 40 | 23 | 1.7 (1.5 to 1.9) | 6.1 (4.9 to 8.0) |

| Gabapentin doses 900 mg daily or more | ||||||

| IMMPACT definition - any substantial pain benefit | 13 | 2627 | 31 | 17 | 1.8 (1.6 to 2.1) | 6.8 (5.6 to 8.7) |

| IMMPACT definition - any substantial pain benefit parallel-group studies ≥ 6 weeks | 8 | 2097 | 33 | 19 | 1.7 (1.5 to 2.0) | 6.8 (5.4 to 9.0) |

| IMMPACT definition - any at least moderate pain benefit | 14 | 2831 | 43 | 26 | 1.7 (1.5 to 1.9) | 5.8 (4.8 to 7.2) |

| IMMPACT definition - any at least moderate pain benefit parallel-group studies ≥ 6 weeks | 9 | 2275 | 43 | 26 | 1.7 (1.4 to 2.0) | 5.9 (4.8 to 7.6) |

Withdrawals (see Summary of results F)

Adverse event withdrawals

Seventeen studies with 3022 participants reported on adverse event withdrawals, which occurred in 12% of participants on gabapentin at daily doses of 1200 mg or more, and in 8% on placebo (Analysis 2.1). The risk ratio was 1.4 (1.1 to 1.7), and the NNH 32 (19 to 100).

All-cause withdrawals

Seventeen studies with 3063 participants reported on withdrawals for any cause, which occurred in 20% of participants on gabapentin at daily doses of 1200 mg or more, and in 19% on placebo (Analysis 2.2). The risk ratio was 1.1 (0.9 to 1.2).

Adverse events (see Summary of results F)

Participants experiencing at least one adverse event

Eleven studies with 2356 participants reported on participants experiencing at least one adverse event, which occurred in 66% of participants on gabapentin at daily doses of 1200 mg or more, and in 51% on placebo (Analysis 3.1). The risk ratio was 1.3 (1.2 to 1.4), and the NNH was 6.6 (5.3 to 9.0).

Serious adverse events

Fourteen studies reported on 2702 participants experiencing a serious adverse event, which occurred in 4.0% of participants on gabapentin at daily doses of 1200 mg or more, and in 3.2% on placebo (Analysis 3.2). The risk ratio was 1.3 (0.9 to 2.0).

Particular adverse events

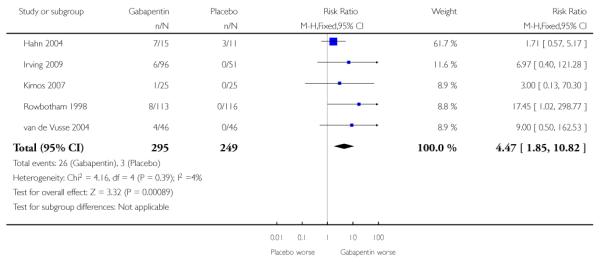

Somnolence, drowsiness, or sedation was reported as an adverse event in 16 studies with 2800 participants, and it occurred in 16% of participants on gabapentin at doses of 1200 mg daily or more, and in 5% on placebo (Analysis 3.3). The risk ratio was 3.2 (2.5 to 4.2), and the NNH was 9.2 (7.7 to 12).

Dizziness was reported as an adverse event in 16 studies with 3150 participants, and it occurred in 21% of participants on gabapentin at doses of 1200 mg daily or more, and in 7% on placebo (Analysis 3.4). The risk ratio was 3.2 (2.5 to 4.2), and the NNH was 7.0 (6.1 to 8.4).

Peripheral oedema was reported as an adverse event in nine studies with 2042 participants, and it occurred in 8.2% of participants on gabapentin at doses of 1200 mg daily or more, and in 2.9% on placebo (Analysis 3.5). The risk ratio was 3.4 (2.1 to 5.3), and the NNH was 19 (14 to 29).

Ataxia or gait disturbance was reported as an adverse event in five studies with 544 participants. It occurred in 26/295 (8.8%) participants on gabapentin at doses of 1200 mg daily or more, and in 3/249 (1.1%) on placebo, though all but one study reported no events with placebo (Analysis 3.6). This produced a risk ratio of 4.5 (1.9 to 11), and the NNH was 13 (9 to 24).

Summary of results F: Withdrawals and adverse events with gabapentin (1200 mg daily or more) compared with placebo

| Number of | Percent with outcome | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Studies | Participants | Gabapentin | Placebo | Risk ratio (95% CI) | NNH (95% CI) |

| Withdrawal due to adverse events | 17 | 3022 | 12 | 8 | 1.4 (1.1 to 1.7) | 32 (19 to 100) |

| Withdrawal - all-cause | 17 | 3063 | 20 | 19 | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.2) | Not calculated |

| At least one adverse event | 11 | 2356 | 66 | 51 | 1.3 (1.2 to 1.4) | 6.6 (5.3 to 9.0) |

| Serious adverse event | 14 | 2702 | 4.0 | 3.2 | 1.3 (0.9 to 2.0) | Not calculated |

| Somnolence/drowsiness | 16 | 2800 | 16 | 5 | 3.2 (2.5 to 4.2) | 9.2 (7.7 to 12) |

| Dizziness | 16 | 3150 | 21 | 7 | 3.2 (2.6 to 4.1) | 7.0 (6.1 to 8.4) |

| Peripheral oedema | 9 | 2042 | 8.2 | 2.9 | 3.4 (2.1 to 5.3) | 19 (14 to 29) |

| Ataxia/gait disturbance | 5 | 544 | 8.8 | 1.2 | 4.5 (1.9 to 11) | 13 (9 to 24) |

Death

Deaths were rare in these studies. Four deaths occurred in PHN studies; two with placebo - one in 116 participants (Rowbotham 1998) and one in 133 (Wallace 2010); two with gabapentin - one in 223 participants (Rice 2001) and one in 107 (Irving 2009). An unpublished study (CTR 945-1008) reported two deaths; one of 200 participants treated with gabapentin, and one of 189 treated with placebo. A further study reported two deaths in 152 participants taking placebo (Serpell 2002). Overall, three deaths occurred with gabapentin and five with placebo.

DISCUSSION

Summary of main results

Gabapentin is a reasonably effective treatment for a variety of neuropathic pain conditions. It has been demonstrated to be better than placebo across all studies for IMMPACT outcomes of substantial and to have at least moderately important benefit, producing almost identical results for all trials and those in parallel-group studies lasting six weeks or longer. Numbers needed to treat to benefit (NNTs) were 6.8 (5.6 to 8.7) and 5.8 (4.8 to 7.2) for substantial and at least moderately important benefits, respectively. Results were consistent across the major neuropathic pain conditions tested, though some uncommon conditions could only be tested in small numbers.

Though gabapentin was tested in 12 different neuropathic pain conditions, only for three was there sufficient information to be confident that it worked satisfactorily, namely PHN, PDN, and mixed neuropathic pain, itself principally, though not exclusively, PHN and PDN.

Benefit was balanced by more withdrawals due to adverse events, and participants taking gabapentin experienced more adverse events, including somnolence, dizziness, peripheral oedema, and gait disturbance than did those taking placebo. Serious adverse events were no more common with gabapentin than placebo, and death was an uncommon finding in these studies.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Efficacy and adverse event outcomes were not consistently reported across the studies, and this limited the analyses to some extent. However, for the most important efficacy and adverse event outcomes, analyses across all conditions were mostly based on between 1000 and over 3000 participants. All the larger studies (typically those with more than 100 participants) reported some efficacy outcome that fitted one or both of the IMMPACT outcomes of at least moderate or substantial benefit. Clearly, analysis at the level of the individual patient would facilitate a more robust estimate. There is one important unknown, namely whether the declaration of response in the trials was for participants who had both an analgesic response and were able to take gabapentin. If response included an LOCF assessment of efficacy from those who discontinued, this could have affected the results. Currently we have no knowledge of the size of any effect, and the practice in these studies is likely to have been the same as that in studies of other drug treatments in neuropathic pain - namely LOCF.

We understand that research has been done on a gabapentin pro-drug and a gabapentin gastric retention formulation. The total sample size of neuropathic pain subjects in these studies exceeds 1200 participants and so could meaningfully affect the numbers reported in this review. These studies are not yet published, but the review should be updated as soon as adequate data become available. Two studies of extended release gabapentin (Irving 2009;Wallace 2010) included in this review produced results not dissimilar from other formulations.

One difficulty is how to deal with relatively short term, relatively small, multiple cross-over studies that intensively study participants on a daily basis (Gilron 2005; Gilron 2009), but that do not report outcomes of clinical relevance (participants with adequate pain relief), but rather average pain scores, whose relevance has been questioned because of underlying skewed distributions (Moore 2010d). These studies can provide useful and clinically relevant information, like the relatively rapid onset of effect of therapies in neuropathic pain, even with average data.

There were almost no data for direct comparisons with other active treatments. This becomes important now that efficacy for gabapentin in neuropathic pain has been established, so that it’s place in relation to alternative therapy can be determined.

Quality of the evidence

The studies included in this review covered a large number of different painful conditions. For some, like HIV neuropathy for instance, it is unclear whether antiepileptic drugs such as gabapentin are effective in the condition. The main quality issues involve reporting of outcomes of interest, particularly dichotomous outcomes equivalent to IMMPACT, as well as better reporting of adverse events. The earliest study was published in 1998, and the past decade or so has seen major changes in clinical trial reporting. The studies themselves appear to be well-conducted, and individual patient analysis could overcome some of the shortcomings of reporting.

Potential biases in the review process

The review was restricted to randomised double-blind studies, thus limiting the potential for bias. Other possible sources of bias that could have affected the review included:

Duration - NNT estimates of efficacy in chronic pain studies tend to increase (get worse) with increasing duration (Moore 2010a). However, limiting studies to those of six weeks or longer did not change the main efficacy outcomes, mainly because most participants were in longer duration studies.

Outcomes may effect estimates of efficacy, but the efficacy outcomes chosen were of participants achieving the equivalent of IMMPACT-defined moderate or substantial improvement, and it is likely that lesser benefits, such as “any benefit” or “any improvement”, are potentially related to lesser outcomes, though this remains to be clarified.

The dose of gabapentin used differed between studies, in terms of maximum allowable dose, whether the dose was fixed, titrated to effect, or titrated up to the maximum irrespective of beneficial or adverse effects. We chose to pool data irrespective of dose, within broad limits, because it was the only practical way to deal with dose in a pooled analysis, and because of a lack of good evidence of any clear dose response for gabapentin in neuropathic pain.

The question of whether cross-over trials exaggerate treatment effects in comparison with parallel-group designs, as has been seen in some circumstances (Khan 1996), is unclear but unlikely to be the source of major bias (Elbourne 2002). Withdrawals meant that any results were more likely to be per protocol for completers than for a true ITT analysis. Parallel-group studies were larger than cross-over studies, and dominated analyses in terms of number of participants. The 15 parallel-group studies involved 2567 participants (median 150 participants), while the 13 cross-over studies involved 633 participants (median 40 participants). The cross-over studies were therefore dominated by results from larger parallel-group studies and, additionally, few cross-over studies reported outcomes that could be used in the analyses.

The absence of publication bias (unpublished trials showing no benefit of gabapentin over placebo) can never be proven. However, we can calculate the number of participants in studies of zero benefit (risk ratio of one) that would be required for the absolute benefit to reduce beneficial effects to a negligible amount (Moore 2008). If an NNT of 10 were considered a level that would make gabapentin clinically irrelevant, then for moderate benefit across all types of neuropathic pain there would have to be 1989 participants in zero effect studies, and for substantial benefit 1200 participants. With median study size for parallel-group studies, this would require a minimum of eight unavailable studies, or four studies of the largest size. This number of unavailable studies seems unlikely.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Previous version of this review

This review differs from the original review (Wiffen 2005) from which it was split in to two parts (acute pain (Straube 2010) and this review on Chronic neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia) in two major respects:

It uses strict definitions of what constitutes at least moderate and substantial benefit as defined by the 2008 IMMPACT criteria (Dworkin 2008). The previous review used a hierarchy of outcomes (pain relief of 50% or greater, global impression of clinical change, pain on movement, pain on rest or any other pain-related measure) that would have allowed any pain benefit to have been counted. That was reasonable, and continued a process of demonstrating that antiepileptic drugs effectively relieved pain in neuropathic pain conditions that began a decade earlier (McQuay 1995). This present review uses developing considerations that people with chronic pain want high levels of pain relief, ideally with more than 50% pain relief, and pain not worse than mild (O’Brien 2010), a result not dissimilar to that in cancer pain (Farrar 2000). Use of more stringent outcomes is likely to lead to lower estimates of efficacy, as has been described in acute migraine (Oldman 2002).

It has available many more studies and participants - at 3571 participants nearly two and a half times as many as before, including two previously unpublished studies with over 700 participants in PDN. The new information available derives from more modern studies with better reporting, and especially better reporting of dichotomous efficacy outcomes, and includes previously unpublished information, as has been recommended (Vedula 2009).

A consequence of the stringent definition of outcome and the larger numbers available has resulted in a reduction in estimates of efficacy over all studies, and for PHN and PDN analysed separately, as shown by increased NNTs (Summary of results G). Decreased estimate of efficacy was most noticeable for PDN, for which previously unpublished results made a major contribution to the updated review.

Summary of findings G: Comparison of NNTs from previous and present reviews

| Previous review | Current review | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | Improvement | IMMPACT moderate benefit | IMMPACT substantial benefit |

| All studies | 4.3 (3.5 to 5.7) | 5.8 (4.8 to 7.2) | 6.8 (5.6 to 8.7) |

| PHN | 3.9 (3.0 to 5.7) | 5.5 (4.3 to 7.7) | 7.5 (5.2 to 14) |

| PDN | 2.9 (2.2 to 4.3) | 8.1 (4.7 to 28) | 5.8 (4.3 to 9.0) |

Other systematic reviews

One other review has provided NNTs for gabapentin in different neuropathic pain conditions based on 50% pain relief, quoting NNTs of 4.7 and 4.3 for neuropathic pain and peripheral pain, and 4.6 and PHN and 3.9 for PDN (Finnerup 2005). A systematic review of therapies for PHN considered gabapentin effective, with an NNT of 4.6 (Hempenstall 2005). These efficacy estimates are also more optimistic than NNTs for IMMPACT substantial benefit calculated for this review, and more optimistic than NNTs calculated for the same outcome of at least 50% pain relief for PHN of 5.7 and PDN of 5.8. The use of more stringent criteria for efficacy, and availability of more information from longer duration studies has led to more conservative efficacy results. Both pregabalin and duloxetine produce NNTs in the region of five to six for at least 50% pain relief over eight to 12 weeks compared with placebo in PHN and PDN (Lunn 2009; Moore 2009a; Sultan 2008).

A number of other systematic reviews have examined efficacy of gabapentin in neuropathic pain. Systematic reviews of gabapentin for neuropathic pain in spinal cord injury (Tzellos 2008) and fibromyalgia (Hauser 2009) found no more studies than those reported here. An examination of the effects of enriched enrolment found no more studies, and produced similar results for withdrawals and adverse events based on a more limited data set (Straube 2008). A review comparing gabapentin and duloxetine in PDN was limited to two gabapentin studies, was statistical in nature, and restricted to average changes in some efficacy parameters (Quilici 2009). The most directly relevant was a comparison between gabapentin and tricyclic antidepressants (Chou 2009), in which a meta-analysis of six placebo-controlled gabapentin studies in PHN, PDN, and mixed neuropathic pain was performed. Using a mixture of outcomes the relative benefit compared with placebo was 2.2, similar to those found for the ‘all studies’ analysis and for analyses for PHN, PDN, and mixed neuropathic pain in this review. A systematic review of pregabalin and gabapentin in fibromyalgia (Hauser 2009) reported only on the single study identified in this review, but reported overall good reductions in pain and other outcomes, with no major difference between gabapentin and pregabalin.

There is one further review in the public domain (Perry 2008) which was performed as part of a legal case in the United States ending in 2009. Perry 2008 did consider similar outcomes to this review; NRS/VAS pain score was given hierarchical priority between >50% reduction in pain score (higher priority) and PGIC (lower priority) mainly because it was the pre-defined primary end point in almost all studies, and for some studies it was difficult to determine how the secondary endpoints were manipulated during changes in statistical analysis plans post hoc. The Perry conclusions are very similar to those of the present review. The likely real differences would lie in the fact that Perry excluded Perez 2000 and Simpson 2001, and did not have access to Sandercock 2009,Irving 2009, and Wallace 2010 (not yet published).

Perry’s conclusion on effectiveness was a clinical judgement based on balancing NNH against NNT, using the Cochrane glossary definition of effectiveness, and presuming that inherent biases in the studies (enrichment, exclusion of many typical real world patients) implied that on balance the benefit of gabapentin use on average does not exceed the harm, which is a somewhat different issue than addressed by this Cochrane review.

AUTHORS’ CONCLUSIONS

Implications for practice

Gabapentin at doses of 1200 mg or more is effective for some people with painful neuropathic pain conditions. About 43% (almost one in two) can expect a moderately important benefit with gabapentin, and 31% (almost one in three) can expect a substantial benefit. Over half of those treated with gabapentin will not have worthwhile pain relief. Results might vary between different neuropathic pain conditions, and the amount of evidence for gabapentin in some conditions (all except PHN, PDN, mixed) is low, excluding any confidence that it works or does not work.

The levels of efficacy found for gabapentin are consistent with those found for other drug therapies in these conditions.

Implications for research

The main research directions that would help:

Analysis of all gabapentin studies at the level of the individual participant in order to have consistent outcomes, and analyses based on them. Individual patient analyses can provide important information, for example showing that good pain response delivers large functional and quality of life benefits beyond pain (Moore 2010c).

More research in to the efficacy of gabapentin in some painful neuropathic pain conditions where there is insufficient information. These conditions tend to be uncommon, and studies can be difficult, with few possible participants. Others, though, like fibromyalgia, are common.

The main issue, though, is not whether gabapentin is effective, as it clearly is highly effective in a minority of patients, but how best to use it in clinical practice. New study designs have been proposed to examine this (Moore 2009c).

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY.

Gabapentin for chronic neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia in adults

Antiepileptic drugs like gabapentin are commonly used for treating neuropathic pain, usually defined as pain due to damage to nerves. This would include postherpetic neuralgia (persistent pain experienced in an area previously affected by shingles), painful complications of diabetes, nerve injury pain, phantom limb pain, fibromyalgia and trigeminal neuralgia. This type of pain can be severe and long-lasting, is associated with lack of sleep, fatigue, and depression, and a reduced quality of life. In people with these conditions, gabapentin is associated with a moderate benefit (equivalent to at least 30% pain relief) in almost one in two patients (43%), and a substantial benefit (equivalent to at least 50% pain relief) in almost one in three (31%). Over half of those taking gabapentin for neuropathic pain will not have good pain relief, in common with most chronic pain conditions. Adverse events are experienced by about two-thirds of people taking gabapentin, mainly dizziness, somnolence (sleepiness), oedema (swelling), and gait disturbance, but only about 1 in 10 (11%) have to stop the treatment because of these unpleasant side effects. Overall gabapentin provides pain relief of a high level in about a third of people who take it for painful neuropathic pain. Adverse events are frequent, but mostly tolerable. This review looked at evidence from 29 studies involving 3571 participants.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We wish to thank Dr Thomas Perry for directing us to clinical trial reports and synopses of published and unpublished studies of gabapentin, and Dr Mike Clarke and colleagues for their advice and support.

SOURCES OF SUPPORT

Internal sources

No sources of support supplied

External sources

NHS Cochrane Collaboration Programme Grant Scheme, UK.

European Union Biomed 2 Grant no. BMH4 CT95 0172, UK.

CHARACTERISTICS OF STUDIES

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | Multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, partial enrichment, LOCF Titration to limit of tolerability or maximum 2400 mg daily over 6 weeks, then 6 weeks stable dose (12 weeks in total) |

|

| Participants | Fibromyalgia (ACR criteria for diagnosis). N = 150 , median age 48 years, 90% women. PI at randomisation ≥4/10, initial pain score 5.8/10 Excluded: individuals with prior treatment with gabapentin or pregabalin |

|

| Interventions | Gabapentin 2400 mg daily (max), n = 75 Placebo, n = 75 Maximum dose 2400 mg daily, placebo was diphenhydramine Paracetamol and OTC NSAIDs allowed (no dose limit stated) |

|

| Outcomes | ≥ 30% reduction in pain Adverse events Withdrawals |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R = 1, DB = 2, W = 1, Total = 4 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Not described |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Yes | “matching placebo” |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? Efficacy |

Unclear | LOCF |

| Size Efficacy |

Yes | 229 |

| Study duration Efficacy |

Yes | 8 weeks |

| Outcomes reported | Unclear | ≥ 30% reduction in pain |

| Methods | Multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, not enriched, LOCF Titration to maximum tolerated dose or 3600 mg daily over 4 weeks, then stable dose for 4 weeks (8 weeks in total) |

|

| Participants | Painful diabetic neuropathy. N = 165, mean age 53 years, 40% women. Pain duration > 3 months before treatment, PI ≥40/100 at randomisation, initial mean pain score 6.4/10 | |

| Interventions | Gabapentin 3600 mg daily (max), n = 84 Placebo, n = 81 Medication for diabetes control remained stable during study. Paracetamol (max 3 g daily) allowed |

|

| Outcomes | PGIC much or moderately improved ≥ 50% reduction in pain (CTR) PGIC much improved (CTR) PGIC moderately or much improved (CTR) Adverse events Withdrawals |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R = 2, DB = 2, W = 1, Total = 5 Parke-Davies/Pfizer sponsored |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Not reported |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Yes | “supplied in identical capsules in blinded fashion”. “All participants were supplied with an equal number of capsules” |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? Efficacy |

Unclear | LOCF |

| Size Efficacy |

Unclear | 165 |

| Study duration Efficacy |

Yes | 8 weeks |

| Outcomes reported | Yes | At least 50% reduction in pain |

| Methods | Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over, not enriched. No imputation method mentioned Titration to maximum tolerated dose or 2400 mg daily over 1 week, then stable dose for 5 weeks (6 weeks total); 1-week washout, then cross-over |

|

| Participants | Established phantom limb pain ≥ 6 months, N = 19, mean age 56 years, 21% women. PI before treatment > 3/10, initial pain score 6.4/10 14 completed both treatment periods |

|

| Interventions | Gabapentin 2400 mg daily (max) Placebo Paracetamol + codeine 500 mg/30mg (max 12 tablets daily) allowed as rescue medication. Stable, low doses of TCAs continued |

|

| Outcomes | No dichotomous efficacy data Adverse events |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R = 2, DB = 2, W = 1, Total = 5 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Not described - but probably OK - remote |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Yes | “identical, coded medication bottles containing identical tablets of gabapentin or placebo” |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? Efficacy |

Unclear | No imputation mentioned |

| Size Efficacy |

No | 19 randomised |

| Study duration Efficacy |

Unclear | 6 weeks each period |

| Outcomes reported | No | No dichotomous data |

| Methods | Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, partial enrichment. No imputation method mentioned Titration to pain ≤ 3/10 or limit of tolerability, or maximum 1800 mg daily (10 days in total) |

|

| Participants | Neuropathic cancer pain despite regular systemic opioid therapy. N = 121, mean age 60 years, 56% women. Pain at randomisation ≥ 5/10, initial pain intensity 7.3/10 | |

| Interventions | Gabapentin 1800 mg daily (max), n = 80 Placebo, n = 41 Any previous analgesics continued unchanged. One additional dose of opioid allowed for rescue medication |

|

| Outcomes | No dichotomous efficacy data Adverse events Withdrawals |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R = 2, DB = 2, W = 1, Total = 5 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Allocation concealment? | Yes | Remote pharmacy department provided numbered containers |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Yes | “identical capsules” |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? Efficacy |

Unclear | Imputation not mentioned |

| Size Efficacy |

Unclear | 121 randomised |

| Study duration Efficacy |

No | 10 days |

| Outcomes reported | No | No dichotomous outcomes |

| Methods | Randomised, double-blind, active controlled, parallel-group, no enrichment Dose escalation every 2 weeks until adequate pain relief obtained or limit of tolerability, to maximum nortriptyline 150 mg daily or gabapentin 2700 mg daily by 4 weeks, then stable dose for 5 weeks (9 weeks in total) |

|

| Participants | Postherpetic neuralgia. N = 76, mean age 54 years, 50% women. Pain > 2 months after healing of skin rash. PI at randomisation ≥ 40/100, initial average daily pain score 5.7/10 | |

| Interventions | Gabapentin 2700 mg daily (max), n = 38 Nortriptyline 150 mg daily (max), n = 38 Of ‘responders’ ~80% gabapentin took 2700 mg daily, ~66% nortriptyline took 75 mg daily |

|

| Outcomes | ≥ 50% pain relief over baseline pain ≥ 50% pain relief over (VAS) Adverse events Withdrawals |

|