Abstract

Objective

This article describes the rigorous development process and initial feedback of the PRE-ACT (Preparatory Education About Clinical Trials) web-based- intervention designed to improve preparation for decision making in cancer clinical trials.

Methods

The multi-step process included stakeholder input, formative research, user testing and feedback. Diverse teams (researchers, advocates and developers) participated including content refinement, identification of actors, and development of video scripts. Patient feedback was provided in the final production period and through a vanguard group (N = 100) from the randomized trial.

Results

Patients/advocates confirmed barriers to cancer clinical trial participation, including lack of awareness and knowledge, fear of side effects, logistical concerns, and mistrust. Patients indicated they liked the tool’s user-friendly nature, the organized and comprehensive presentation of the subject matter, and the clarity of the videos.

Conclusion

The development process serves as an example of operationalizing best practice approaches and highlights the value of a multi-disciplinary team to develop a theory-based, sophisticated tool that patients found useful in their decision making process.

Practice implications Best practice approaches can be addressed and are important to ensure evidence-based tools that are of value to patients and supports the usefulness of a process map in the development of e-health tools.

Keywords: Decision support tools, Decision aids, Clinical trials, Cancer

1. Introduction

Despite the importance of cancer clinical trials in improving patient care and discovering effective new methods of prevention, treatment, and rehabilitation for many diseases [1], very few cancer patients participate [2–4]. Researchers have identified numerous barriers to clinical trial participation that may be broadly categorized as patient, provider and system-related factors [5–27]. Although the focus of most research on patient barriers has been on practical barriers (e.g. financial concerns and lack of access) [3,5,7], we [8,13,14,47] and others [6,7,9–12,15–22] have found that that there are also key psychosocial barriers that limit patient participation. These include lack of knowledge and concerns about side effects and randomization, fear of placebos, and feeling “like a guinea pig.” These barriers negatively impact patient preparedness to consider clinical trials as an option [28] and are difficult to adequately address during the physician consultation, potentially leading to suboptimal treatment decisions.

The PRE-ACT (Preparatory Education About Clinical Trials) e-health intervention sought to improve preparation for considering clinical trials as a treatment option by addressing individual patient psychosocial barriers. It is based on the Cognitive Social Health Information Processing Theory [29] and Ottawa Decision Support Framework [30] and is designed to address knowledge and other psychosocial factors that impact participation. Additionally, the PRE-ACT intervention was developed using a rigorous process based on health communication and decision support tool frameworks and best practices. It relied on an extensive multi-media platform delivered via a secure website and focused on key issues faced by patients in understanding clinical trials and making informed decisions about participation.

The intervention is a tailored interactive web-based preparatory decision aid designed to address psychosocial barriers (knowledge and attitudinal barriers) before a patient’s first oncologist visit with the aim to improve preparation for consideration of clinical trials as a treatment option. This preparatory process was designed to support informed decision making, where a reasoned choice is made by using relevant information about the personal advantages and disadvantages of the possible options [31]. With the ubiquity of computers and the internet, web- and computer-based decision aids (DAs) have become increasingly popular. Although traditional DAs such as booklets, pamphlets, decision boards, and videos have been shown to enhance knowledge and decrease decisional conflict regarding health decisions [32–36], computer-based DAs appear to result in better outcomes [32,37] and increased readiness for decision making [38], at least in the short-term [37,38]. Web- and computer-based DAs offer the ability to deliver tailored content based on individuals’ demographic characteristics, health beliefs, values, and treatment preferences [32,38,39]. This can lead to increased participant engagement and self-efficacy, as messages are viewed more positively and are more likely to be remembered and viewed as relevant [39] and consistent with patients’ personal values [40,41]. Additionally, web- and computer-based DAs have the ability to use multiple methods of presentation for tailored content, including audio, video, animation, and interactivity [32], facilitating information processing.

Although some web- and computer-based DAs have focused on prostate [32,42], breast [38], and colorectal cancers [36,43], there have been only a few examples [44] in the literature addressing web- or computer-based DAs to target decisions about cancer clinical trials. The PRE-ACT decision aid was guided by the International Patient Decision Aid Standards (IPDAS) Collaboration [45], which recommends that tools provide: balanced personalized information about options, sufficient information to ensure the patient is knowledgeable about options, facts about outcomes and probabilities, personal values related to options, and guidance in steps of deliberation and communication to match decisions with personal values. These guidelines have been operationalized by Elwyn et al. [46], promoting a systematic process map for developing tailored web-based decision support interventions for patients, based on best practices of health communication research and their own experiences. Elwyn et al.’s process map focused on the need for a multi-disciplinary advisory team, stakeholder involvement for content development, and usability testing during the developmental process.

The web-based PRE-ACT intervention (including assessments and interactive e-health software) had four main components: (1) pre-consultation survey with personalized ranking of barriers to clinical trials, (2) tailored patient feedback to address individual barriers and values including delivery of short video clips, (3) post-intervention assessment prior to the oncologist consultation, and (4) post-consultation assessment. This article focuses on the rigorous development process and user feedback about the PRE-ACT tailored web-based DA.

2. Methods

A multi-step development process was used to create the PRE-ACT intervention and is described in detail.

2.1. Infrastructure for development: multi-disciplinary teams

Development of the PRE-ACT intervention required an infrastructure comprised of multi-disciplinary decision makers, creators, and stakeholders (Fig. 1). These teams were essential to ensure we addressed both content and approach from multiple perspectives and to had a sufficient team to undertake the complex, expensive, and time-consuming process required to develop a high-quality interactive decision aid [46].

Fig. 1.

Multi-disciplinary PRE-ACT development teams.

2.2. Content refinement: identification of barriers

The content refinement phase for PRE-ACT was similar to what Elwyn et al. referred to as a content specification phase – an important first phase during which patients’ needs are assessed and evidence is synthesized to ensure that the intervention is tailored as effectively as possible to the target population [46]. Since an important component of PRE-ACT was to investigate background and psychosocial variables that might be associated with preparedness, barriers, and treatment outcomes, identification and validation of the relevant barriers for the patient population required involvement from our stakeholders in the form of survey research and focus groups to identify the relevant factors.

Findings from a previously conducted pilot study with 156 patients receiving care at one of two NCI-designated comprehensive cancer centers [47] guided our development process. These patients completed a survey that contained eight background and demographic questions, 19 knowledge-based items, and 29 attitudinal barrier questions. Results confirmed the prevalence of the barriers surveyed, and revealed associations of demographic characteristics with knowledge-based and attitudinal barriers, including: (1) lower educational level associated with all subcategories of barriers; (2) non-white race was associated with barriers in unadjusted analyses, but may not be an independent predictor when adjusting for other factors; and (3) women had more fear and emotional concerns regarding clinical trial participation.

To further validate the salience, scope, and wording of these barriers for the patient population targeted by PRE-ACT, we conducted focus groups early in the development process. Using a convenience sample of cancer patients, patient advocates, and community members, we conducted three focus groups, with an age range between 40 and 70 years old. Two groups were recruited at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) in Chicago. These groups included Caucasian patient advocates (n = 5), as well as Caucasian cancer patients and patient advocates (n = 7). A third focus group was recruited with the assistance of patient advocates from Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia. This group consisted of African American community members (n = 10), four of whom had cancer. All three focus groups were told about the standard psychosocial barriers to cancer clinical trials (Table 1) and participants were asked to: (1) rank what they perceived to be the top 5 barriers for most people; (2) indicate which barriers would be most difficult to address, and/or most pervasive and widely held; and (3) identify any additional barriers.

Table 1.

Psychosocial barriers for cancer clinical trial participation presented to stakeholder focus groups.

| 1. Awareness |

| Patients are unaware of clinical trials as a treatment option. |

| 2. General clinical trial knowledge |

| Patients are aware of clinical trials, but do not have an accurate understanding of clinical trial processes (e.g., informed consent, randomization, phase differences). |

| 3. Side effects |

| Patients are fearful of side effects of the treatment received while enrolled in a clinical trial. |

| 4. Randomization |

| Patients are uncomfortable with being randomized to a particular treatment arm in a clinical trial. |

| 5. Placebo |

| Patients are fearful of receiving a placebo as their treatment in a clinical trial. |

| 6. Distrust in medical establishment |

| Patients do not trust that their physician and health care team have the patients’ best interests in mind when conducting clinical trials. |

| 7. Fear of being used as a Guinea pig |

| Patients fear being used as an experimental subject while participating in a clinical trial. |

| 8. Standard vs. experimental care |

| Patients believe they will receive worse care from their health care team while enrolled in a clinical trial as compared to standard treatment. |

| 9. Clinical trials are a last resort |

| Patients believe that clinical trials are only a treatment option after all other treatment options have proven ineffective. |

| 10. Self-efficacy |

| Patients do not believe that they would be able to handle the requirements of participating in a clinical trial. |

| 11. Altruism |

| Patients would not choose to participate in a clinical trial to help improve cancer treatments for future patients. |

| 12. Logistics/transportation |

| Patients are unable to participate in a clinical trial because of time constraints or the inability to travel to the treatment site. |

| 13. Financial costs |

| Patients are unable to afford the costs of participating in a clinical trial. |

| 14. Negative affect/worry |

| Patients are worried and anxious about participating in a clinical trial. |

| 15. Financial and/or professional conflicts of interest |

| Patients would not choose to participate in a clinical trial if their doctor were to gain financially from enrolling them in the trial. |

| 16. Physician referral |

| Patients would only participate in a clinical trial if their physician brought it up as a treatment option/referred them. |

2.3. Digital content design phase: identifying actors and developing scripts

The digital content design phase for PRE-ACT included the development and testing of the tailored web-based decisional aid (DA). Since the PRE-ACT intervention was multi-media rich, extensive work was required to identify actors and develop appropriate scripts. Therefore, this phase required the most significant involvement from the stakeholders – patients and patient advocates – to assist in video design and usability testing for the PRE-ACT intervention. Two of the three focus groups were also asked to assist with video development by indicating their preferences for appropriate actors and providing feedback on the video script messages. Additionally, cancer patients assisted in the design phase by providing feedback about the usability of the web-based DA and making suggestions for improvements.

2.3.1. Identification of actors

We used a rigorous process to identify the actors for the videos, relying on testing triads of actor headshots. Triads are a cognitive anthropology method used to understand similarities and differences between concepts within a domain [48,49]. This allowed us to identify the preferred demographic characteristics in case a given actor was unavailable after selection, and to learn the dimensions participants unconsciously used to make classifications.

The focus group participants were shown photographs of actor headshots for thirty-six potential PRE-ACT video actors (African American, Caucasian, Asian, and Hispanic race and ethnicity, males and females, wide age distribution), in the form of randomized triads. For each triple, participants were asked to select the image that looks most like a specific role patient, doctor, or nurse. A Lambda-2 balanced incomplete block design, which holds two images constant for each permutation to reduce order bias and force choices among racial minorities and genders, was used to select the final set of actors. The elimination process included randomizing the 36 actors into three groups (12 in each group). We calculated frequency of selection – defined as the number of times an actor was selected for a role/total number of appearances – as well as salience – defined as the average consensus score/number times an actor was selected.

Given that the actors who provided headshots were not available for this project, the physical characteristics of the actors selected by focus groups were prioritized. A casting call was subsequently held and actors were videotaped while reading scripts. These video samples were then used to select the final actors for PRE-ACT.

2.3.2. Development of scripts

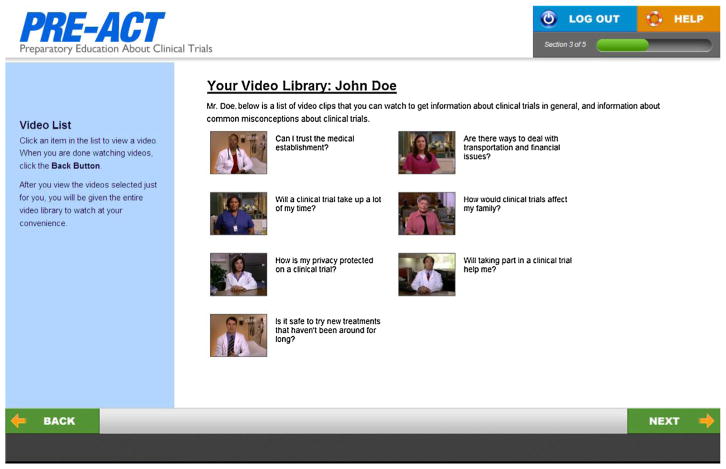

The focus groups also assisted in the development and selection of culturally sensitive video scripts. Patients and patient advocates were shown mockup screen shots of the web-based DA and were given video script messages. Based on these images and scripts, participants were asked to provide feedback on: (1) overall comprehensibility (semantics, length, cognitive/information load and organization); (2) whether the material was sufficiently diverse (for cultural background of patients, as well as for representativeness of different cancer stages and cancer types); and (3) visual impact (overall appeal and actor believability). Fig. 2 is a screen shot from the final DA.

Fig. 2.

Screen shot from PRE-ACT decision support tool.

Focus group participants were also questioned about how they would make the DA more appealing and easier to use for other patients, and the scripts more easily understood. Additionally, participants were instructed to think about their own experiences and those of people they know to provide feedback about whether the scripts adequately covered the concerns cancer patients might have about clinical trials.

2.4. User feedback

Patient feedback on the PRE-ACT decision tool was obtained at two points: at the final production stage and through a vanguard group of the first 100 users of the PRE-ACT decision tool from the randomized trial which tested the impact of PRE-ACT vs. a control condition of informational text without tailored video delivery. At the final production stage, a small group of cancer patients recruited at one of the test sites reviewed both the web-based intervention as well as NCI print materials (used in the control arm) to make certain the intervention worked as intended and there were no major concerns with the materials.

Research staff observed and timed the participants as they completed their login to the web site, the baseline assessment survey, the online text from the NCI (control group) or the tailored PRE-ACT videos (intervention), the post-intervention assessment survey, and the post-consultation assessment survey. Participants navigated the website and were asked questions about the layout, content with directions, audio/video, and navigation throughout the PRE-ACT tool. In addition to watching and recording users’ actions, research staff also asked user-specific questions based upon difficulties/actions observed throughout the process. For example, if a participant took more time in one section, research staff asked, “I noticed you reviewed the _____ section very closely; do you have any questions or concerns about the information provided?” If a user skipped a question, research staff asked, “I noticed you did not answer question _____; was the question difficult to understand or answer?” User-specific questions were asked after each section of the PRE-ACT control text or intervention tool to ensure immediate feedback.

The first 100 users of the PRE-ACT decision tool from the randomized trial were used as a vanguard group to gather initial feedback about the tool from patients in the randomized trial. Responses from process evaluation questions on the first follow-up survey were reviewed. These questions were to gather feedback about the PRE-ACT decision aid including:

Which of the following best describes your feelings about the length of this program? (reasonable length, a little long, much too long).

What did you like about the program? (open-ended).

What suggestions do you have to improve the program? (open-ended).

2.5. Analysis approach

Both qualitative and quantitative data were collected and analyzed for this process evaluation of the development of the intervention as well as the pilot test. For the development process, the research team reviewed data collected from the focus groups and usability testing, and developed themes based on extensive discussion and consensus. For the evaluation of video actors, we used a Lambda-2 incomplete block design. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the characteristics of the pilot group demographics and independent sample t-tests and Fisher’s exact tests were used to determine differences in participant feedback regarding the web-based intervention.

3. Results

3.1. Infrastructure for development: multi-disciplinary teams

The diverse working teams (Fig. 1) included the Primary Research Team, the Research and Specialists Team, and a group of Stakeholders, all of which were integral to the development of the PRE-ACT intervention. The Primary Research Team had editorial control; made all final decisions on content, design, and testing; obtained resources for the research; and was responsible for the overall protocol and early evaluation during prototype testing. These duties were described as being essential for what Elwyn et al. referred to as a Project Management Group [46] in health communication research. The Primary Research Team for PRE-ACT was comprised of a medical oncologist, behavioral research specialists, and cancer education and health communication specialists from two NCI-designated comprehensive cancer centers.

The Research and Specialists Team supported The Primary Research Team, acting as an advisory group for the research, providing expert advice about the content, suggesting implementation and dissemination strategies, and assisting with obtaining resources for the project [46]. Opinions from this group were carefully considered during the development phases. The Research and Specialists Team for PRE-ACT was multi-disciplinary and well-balanced, including: a specialist in patient-provider communication; two behavioral researchers; a cancer education and health communication specialist; a health literacy/plain language specialist; a medical oncologist; two patient advocates; a production company responsible for creating the videos for the DA; and a technical group responsible for the development of the website that delivered the PRE-ACT survey and videos.

Another group that was integral to the development infrastructure was a group of Stakeholders. Consultations from stakeholders throughout the development process of a web-based DA are essential for feedback about potential reactions and assessments from persons who represent the ultimate patient user [46]. The PRE-ACT intervention made use of Stakeholders through usability testing and development focus groups with patients and patient advocates. Both of these stakeholder groups were significant to the content refinement and design phases of PRE-ACT, further described below.

3.2. Content refinement: identification of barriers

We were fortunate to rely on our previous research as a starting point for the content development of the PRE-ACT intervention [14,47]. Using the existing literature and our prior research, we identified core psychosocial barriers to cancer clinical trials (Table 1). In addition to the barriers presented to the participants, one of the focus groups suggested a barrier of “fear of the unknown.”

3.3. Design phase: identifying actors and developing scripts

3.3.1. Identification of actors

The focus group participants (3 focus groups with 22 participants) had clear preferences for actor selection of each role, with an overall partiality toward minority actors of an older age. In accordance with focus group preferences, we narrowed our actor selection criteria and arranged additional tests of actors who fit the preferred demographics. Since selected actors were unavailable in the production phase, actors with similar demographic characteristics were selected. In addition to actors, it was decided to film an actual oncologist (the Principal Investigator) for introductory clips and three core barrier messages to be delivered to all participants. However, it was critical that it was clear that these were actors and not actual patients In the welcome to the video portion of the PRE-ACT study the Principal Investigator clearly states that “the following videos have been carefully selected just for you based on your survey responses. In these videos, you’ll either see me or actors portraying the roles of doctor, nurse, and patient and providers”.

3.3.2. Development of scripts

Based on focus group feedback, video scripts were further developed with careful attention to “readability,” use of plain language, sensitivity, and applicability to a diverse group of participants that would vary in education level, socio-demographics, and race/ethnicity. Special efforts were applied to present general information about clinical trials in an unbiased fashion. Patient advocates emphasized the importance of utilizing language that empowers patients to ask questions and participate in decision making; the final video scripts reflect this input.

Twenty-eight educational video clips (30- to 90-s each) were subsequently produced to address 48 clinical trial barriers. All videos were filmed on location at Fox Chase Cancer Center in a variety of clinical and office settings (2 physician offices, an exam room, 2 patient waiting rooms, and an infusion suite). Several actors were filmed in the roles of provider and patient for each video clip and final video clips were selected by the Primary Research Team to ensure actor diversity.

Although videos were produced for numerous clinical trial barriers, one of the important benefits of web-based DAs is their facilitation of tailored intervention messages. PRE-ACT aimed to tailor the videos to participants’ individual psychosocial barriers, and to ultimately test them in a randomized trial. To accomplish this goal, web developers used component-based architecture to build and deploy secure, web-enabled data entry/retrieval interfaces and applications (i.e., Java 2 Platform, Enterprise Edition [J2EE]). The computer-based intervention was finalized to include an interactive algorithm for selection of video clips for each participant, based upon their individual scoring and subsequent ranking of identified clinical trials barriers.

3.4. Patient feedback

Table 2 summarizes the feedback (N = 5 participants) received during the user testing at the final production phase. Although participants found the web-based tool generally easy to use and informative, they provided many specific examples to improve the tool’s navigation and instruction, as well as to make the tool easier for users to understand. Based on participant comments and feedback, changes were made including increasing the font size and placement of navigation buttons.

Table 2.

User feedback – final stage of development.

| Functionality | Formatting/utilization | Relevance |

|---|---|---|

Goals:

|

Goals:

|

Goal:

|

Feedback:

|

Feedback:

|

Feedback:

|

For this paper, the process evaluation items from the first 100 participants (Vanguard group) who were assigned the PRE-ACT decision aid from the randomized trial were analyzed. This group was predominately female, Caucasian, Non-Hispanic, and employed with a college degree. The average age of participants was 59 years (Table 3). The participants represented twenty-two different types of cancer, with the largest numbers of diagnoses coming from breast (26%), prostate (14%), colorectal (13%) and lung (12%) cancers.

Table 3.

Demographic characteristics of first 100 PRE-ACT users.

| N | (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 59 | (59) |

| Male | 41 | (41) |

| Race | ||

| Caucasian | 92 | (92) |

| Black or African American | 6 | (06) |

| Asian | 1 | (01) |

| Mixed race | 1 | (01) |

| Employment | ||

| Employed | 33 | (33) |

| Homemaker | 9 | (09) |

| Out of work | 17 | (17) |

| Retired | 40 | (40) |

| Student | 1 | (01) |

| Education | ||

| Some HS | 1 | (01) |

| HS graduate | 23 | (23) |

| Some college | 32 | (32) |

| College graduate | 44 | (44) |

In response to the question about the length of the PRE-ACT program, evaluation data from the first 100 patients revealed that 73% of users found the program length reasonable. Independent sample t-tests revealed that those who felt PRE-ACT was too long tended to be older (mean = 63 years old) than those who felt the length was reasonable (mean = 57 years old). Fisher’s exact tests were used to determine whether perception that the survey length was reasonable or too long was associated with other key variables of the patients (e.g. gender, race, ethnicity, type of cancer diagnosis, employment status, and level of education). However, none of these variables showed statistically significant associations.

In response to the second question, asking what they liked about the program, 63% of users responded with at least one quality that they liked about the PRE-ACT tool. While feedback varied, users identified seven common themes in their responses (see Table 4). Patients’ responses tended to focus on the tool’s user-friendly nature, the organized and comprehensive presentation of the subject matter, and the clarity of the videos. Eighty-two percent completed the initial assessment on their home computer, 9% on a friend or family member’s computer, 4% at work, and 4% at a hospital before their appointment (1 person did not answer this question).

Table 4.

Summary themes and sample quotes – what patient users liked most.

Prepared me to ask questions

|

Format was easy to follow

|

Liked the videos

|

Language was easy to understand

|

Informative

|

Convenient

|

Provided reassurance and hope

|

The third question asked patients what suggestions they would make to improve the PRE-ACT tool. Many participants did not provide an answer (42%), and of those that did write a response to this question, as many as 19% indicated that they did not have any suggestions to make. The 39% of patients who did offer suggestions tended to focus their feedback on the numbers of questions, technical problems they had when navigating the program or watching the videos, concerns about the value of the information at such an emotional time and miscellaneous suggestions for additional questions and materials (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Summary themes and sample quotes – what patient users suggest for improvement.

Reduce the number and questions

|

Technical problems

|

Provide more tailored and unbiased information

|

Other comments – concerns, additional materials and recommended resources

|

3.5. Limitations

There are a number of limitations including that all the data are self-reported and that the user feedback from the vanguard group (the first 100 participants) may not be representative of the entire study group and may have limited generalizability.

4. Discussion and conclusion

4.1. Discussion

Our experience in developing and pilot testing the PRE-ACT clinical trial decision support tool serves as an example of how to operationalize best practice approaches in the development of decision aids. The value of our multi-disciplinary team brought many perspectives to the development process and allowed us to design a theory-based, sophisticated tool that addressed a wide range of issues critical to understanding clinical trial participation. In addition, systematically engaging patients and advocates throughout the entire development process was essential to ensure the patient voice was an integral to the fabric of the tool. Although the term “patient-centered” has become a part of our health care language, often their voice and perspectives are not integral to the entire development process. In this work, patients and patient advocates participated in every step from early stage conceptualization, development of scripts and selection of actors, to providing feedback in the randomized trial to improve next iterations of the decision aid. The patients and patient advocates that participated in the preliminary focus groups confirmed numerous significant barriers to clinical trial participation, including lack of awareness and knowledge, logistical concerns, fear of side effects, and other concerns. Patients and patient advocates also provided insights into the language and types of people (medical, demographics) they preferred to deliver the various messages and information.

The process evaluation results from the vanguard group were important to ensure that the intervention was well received. Almost 3 in 4 patients in the vanguard group found the program to be reasonable in length, and those who found it too long tended to be older. When asked about how to improve the program, some patients commented that the survey could be shorter since “we asked the same questions 4 or 5 different ways.” This feedback assured us that the tool was well received and although it could not be shorten for the research study, this information was important to sensitize the research team when introducing the study. And if the tool is found effective, future dissemination efforts can include a shortened survey to collect only critical data for the tailoring. Additional feedback from patients pointed out the value of comprehensive information, and how it helped them prepare for their appointment, providing an important foundation for an open dialogue with their provider and critical element to an informed decision. The comments about format (e.g. friendly nature, videos) remind us of the importance of creating interesting, multi-media approaches to engage patients in this difficult and serious topic. They also highlighted that they valued the diversity of “presenters” in the videos which required careful planning and testing during the development process. Patients also mentioned that they liked that the videos were tailored to their individual needs, but also liked the option of being able to view all the videos as well. This is an important finding since recognizing the value of computer-based tailoring in conjunction with user-driven exploration of the content. Finally, the majority of patients in the vanguard group accessed the tool from home and comments from the patients highlighted the value of using it at home where they could review it with their family.

Our findings support the value of a best-practice approach, but it is also important to point out that this is a labor- and time-intensive process. The stakeholder group met frequently during the development process and considerable staff time was required for all the related activities. In addition, the production timeline needed to accommodate this collaborative process. However, this developmental process is necessary to ensure the quality and acceptability of decision tools which are essential ingredients to effectiveness and ultimately dissemination.

4.2. Conclusion

Integrating best practice approaches; including a multi-disciplinary team and stakeholders; and careful vetting of evidence-based content and usability testing, as suggested by IPDAS quality standards, is both feasible and essential to a high quality, patient-centered DA. However, this approach requires considerable resources of time and an abiding commitment of the research team. The investment in structured development of web-based educational tools will hopefully increase the likelihood of success when these interventions are subjected to formal evaluation in randomized comparisons to existing standard approaches [50].

4.3. Practice implications

This article focuses on the rigorous development process and initial feedback from study participants regarding the PRE-ACT tailored web-based decision aid. Our experience highlights that these best practice guidelines and approaches can be addressed and are important to ensure evidence-based tools that are of value to patients. This work cannot only serve as an example of best practices in health communication, but also supports the usefulness of the process map suggested by Elwyn et al. [46].

“I confirm all patient/personal identifiers have been removed or disguised so the patient/person(s) described are not identifiable and cannot be identified through the details of the story.”

Acknowledgments

Financial support

Financial support for this study was provided entirely by a grant from the National Cancer Institute to NJM (NCI grant: R01 CA127655). The funding agreement ensured the authors’ independence in designing the study, interpreting the data, writing, and publishing the report.

Nicholas Solarino, Jonathan Trinastic, Allison Silver, Susan Echtermeyer and Fox Chase Cancer Center’s Behavioral Research Core Facility and Office of Health Communications and Health Disparities. A special thanks to all of the patients who generously participated in this study.

References

- 1.Baquet CR, Ellison GL, Mishra SI. Analysis of Maryland cancer patient participation in National Cancer Institute – supported cancer treatment clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3380–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.6027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Refaie WB, Vickers SM, Zhong W, Parsons H, Rothenberger D, Habermann EB. Cancer trials versus the real world in the United States. Ann Surg. 2011;254:438–42. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31822a7047. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e31822a7047 [discussion 42–3] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Go RS, Frisby KA, Lee JA, Mathiason MA, Meyer CM, Ostern JL, et al. Clinical trial accrual among new cancer patients at a community-based cancer center. Cancer. 2006;106:426–33. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Michaels M, Seifer S Education Network to Advance Cancer Clinical Trials (ENACCT) and Community-Campus Partnerships for Health (CCPH) Pract Policy. Silver Spring, MD: 2008. Communities as Partners in Cancer Clinical Trials: Changing Research. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klabunde CN, Springer BC, Butler B, White MS, Atkins J. Factors influencing enrollment in clinical trials for cancer treatment. South Med J. 1999;92:1189–93. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199912000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ellis PM, Butow PN, Tattersall MH, Dunn SM, Houssami N. Randomized clinical trials in oncology: understanding and attitudes predict willingness to participate. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3554–61. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.15.3554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ellis PM, Butow PN, Tattersall MH. Informing breast cancer patients about clinical trials: a randomized clinical trial of an educational booklet. Ann Oncol. 2002;13:1414–23. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gaskin DJ, Weinfurt KP, Castel LD, Depuy V, Li Y, Balshem A, et al. An exploration of relative health stock in advanced cancer patients. Med Decis Making. 2004;24:614–24. doi: 10.1177/0272989X04271041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jenkins V, Fallowfield L. Reasons for accepting or declining to participate in randomized clinical trials for cancer therapy. Br J Cancer. 2000;82:1783–8. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin JS, Finlay A, Tu A, Gany FM. Understanding immigrant Chinese Americans’ participation in cancer screening and clinical trials. J Community Health. 2005;30:451–66. doi: 10.1007/s10900-005-7280-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Llewellyn-Thomas HA, McGreal MJ, Thiel EC. Cancer patients’ decision making and trial-entry preferences: the effects of framing information about short-term toxicity and long-term survival. Med Decis Making. 1995;15:4–12. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9501500103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Melisko ME, Hassin F, Metzroth L, Moore DH, Brown B, Patel K, et al. Patient and physician attitudes toward breast cancer clinical trials: developing interventions based on understanding barriers. Clin Breast Cancer. 2005;6:45–54. doi: 10.3816/CBC.2005.n.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meropol NJ, Weinfurt KP, Burnett CB, Balshem A, Benson AB, 3rd, Castel L, et al. Perceptions of patients and physicians regarding phase I cancer clinical trials: implications for physician–patient communication. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2589–96. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.10.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meropol NJ, Buzaglo JS, Millard JL, Damjanov N, Miller SM, Ridgway CG, et al. Barriers to clinical trial participation as perceived by oncologists and patients. J Natl Comp Cancer Netw. 2007;5:655–64. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2007.0067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mills EJ, Seely D, Rachlis B, Griffith L, Wu P, Wilson K, et al. Barriers to participation in clinical trials of cancer: a meta-analysis and systematic review of patient-reported factors. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:141–8. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70576-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nguyen TT, Somkin CP, Ma Y, Fung LC, Nguyen T. Participation of Asian-American women in cancer treatment research: a pilot study. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2005;35:102–5. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgi046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paterniti DA, Chen MS, Jr, Chiechi C, Beckett LA, Horan N, Turrell C, et al. Asian Americans and cancer clinical trials: a mixed-methods approach to understanding awareness and experience. Cancer. 2005;105:3015–24. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pinto HA, McCaskill-Stevens W, Wolfe P, Marcus AC. Physician perspectives on increasing minorities in cancer clinical trials: an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) Initiative. Ann Epidemiol. 2000;10:S78–84. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00191-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ross S, Grant A, Counsell C, Gillespie W, Russell I, Prescott R. Barriers to participation in randomised controlled trials: a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52:1143–56. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00141-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Townsley CA, Selby Ri Siu LL. Systematic review of barriers to the recruitment of older patients with cancer onto clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3112–24. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.00.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tu SP, Chen H, Chen A, Lim J, May S, Drescher C. Clinical trials: understanding and perceptions of female Chinese-American cancer patients. Cancer. 2005;104:2999–3005. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Winn RJ. Obstacles to the accrual of patients to clinical trials in the community setting. Semin Oncol. 1994;21:112–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brown DR, Fouad MN, Basen-Engquist K, Tortolero-Luna G. Recruitment and retention of minority women in cancer screening, prevention, and treatment trials. Ann Epidemiol. 2000;10:S13–21. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00197-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cassileth BR, Lusk EJ, Miller DS, Hurwitz S. Attitudes toward clinical trials among patients and the public. J Amer Med Assoc. 1982;248:968–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Comis RL, Miller JD, Aldige CR, Krebs L, Stoval E. Public attitudes toward participation in cancer clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:830–5. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.02.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lewis JH, Kilgore ML, Goldman DP, Trimble EL, Kaplan R, Montello MJ, et al. Participation of patients 65 years of age or older in cancer clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1383–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Siminoff LA, Zhang A, Colabianchi N, Sturm CM, Shen Q. Factors that predict the referral of breast cancer patients onto clinical trials by their surgeons and medical oncologists. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:1203–11. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.6.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller SM, Hudson S, Egleston B, Manne S, Buzaglo J, Devarajan K, Fleisher L, Millard J, Solarino N, Trinastic J, Meropol N. The relationships among knowledge, self-efficacy, preparedness, decisional conflict and decisions to participate in the cancer clinical trial. Psycho-Oncology. 2013;22(3):481–9. doi: 10.1002/pon.3043. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pon.3043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller SM, Diefenbach MA. The Cognitive-Social Health Information-Processing (C-SHIP) model: a theoretical framework for research in behavioral oncology. In: Krantz D, editor. Perspectives in behavioral medicine. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1998. pp. 219–44. [Google Scholar]

- 30.O’Connor AM, Tugwell P, Wells G, Elmslie T, Jolly E, Hollingworth G. A decision aid for women considering hormone therapy after menopause: decision support framework and evaluation. Patient Educ Counsel. 1998 Mar;33:267–79. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(98)00026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bekker H, Thornton JG, Airey CM, Connelly JB, Hewison J, Robinson MB, et al. Informed decision making: an annotated bibliography and systematic review. Vol. 3. Winchester, England: Health Technology Assessment; 1999. pp. 1–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Allen JD, Berry DL. Multi-media support for informed/shared decision-making before and after a cancer diagnosis. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2011;27:192–202. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Belkora JK, Volz S, Teng AE, Moore DH, Loth MK, Sepucha KR. Impact of decision aids in a sustained implementation at a breast care center. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86:195–204. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neuman HB, Charlson ME, Temple LK. Is there a role for decision aids in cancer-related decisions. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2007;62:240–50. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O’Brien MA, Whelan TJ, Villasis-Keever M, Gafni A, Charles C, Roberts R, et al. Are cancer-related decision aids effective? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:974–85. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.16.0101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Manne SL, Meropol NJ, Weinberg DS, Vig H, Ali-Khan Catts Z, Manning C, et al. Facilitating informed decisions regarding microsatellite instability testing among high-risk individuals diagnosed with colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1366–72. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.0399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sheehan J, Sherman KA. Computerised decision aids: a systematic review of their effectiveness in facilitating high-quality decision-making in various health-related contexts. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;88:69–86. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sivell S, Edwards A, Manstead ASR, Reed MWR, Caldon L, Collins K, et al. Increasing readiness to decide and strengthening behavioral intentions: evaluating the impact of a web-based patient decision aid for breast cancer treatment options (BresDex. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;88:209–17. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2012.03.012. www.bresdex. com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lustria ML, Cortese J, Noar SM, Glueckauf RL. Computer-tailored health interventions delivered over the Web: review and analysis of key components. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;74:156–73. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stacey D, Bennett CL, Barry MJ, Col NF, Eden KB, Holmes-Rovner M, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;10:CD001431. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abhyankar P, Bekker H, Summers B, Velikova G. Why values elicitation techniques enable people to make informed decisions about cancer trial participation. Health Expect. 2010;14:12. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2010.00615.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Holmes-Rovner M, Stableford S, Fagerlin A, Wei JT, Dunn RL, Ohene-Frempong J, et al. Evidence-based patient choice: a prostate cancer decision aid in plain language. BMC Med Inform Dec Making. 2005;5:16. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-5-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Trevena LJ, Irwig L, Barratt A. Randomized trial of a self-administered decision aid for colorectal cancer screening. J Med Screen. 2008;15:76–82. doi: 10.1258/jms.2008.007110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wells KJ, Quinn GP, Meade CD, Fletcher M, Tyson DM, Jim H, et al. Development of a cancer clinical trials multi-media intervention: clinical trials: are they right for you. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;88:232–40. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2012.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Holmes-Rovner M. International Patient Decision Aid Standards (IPDAS): beyond decision aids to usual design of patient education materials. Health Expect. 2007;10:103–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2007.00445.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Elwyn G, Kreuwel I, Durand MA, Sivell S, Joseph-Williams N, Evans R, et al. How to develop web-based decision support interventions for patients: a process map. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;82:260–5. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eads JR, Albrecht TL, Egleston B, Buzaglo JS, Cohen RB, Fleisher L, et al. Identification of barriers to clinical trials: the impact of education level. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:6003. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Burton M, Nerlove S. Balanced designs for triad tests: two examples from English. Soc Sci Res. 1976;5:247–67. [Google Scholar]

- 49.D’Andrade R. The development of cognitive anthropology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Meropol N, Albrecht T, Wong Y, Benson A, Buzaglo J, Collins M, et al. Randomized trial of a web-based intervention to address barriers to clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(Suppl):6500. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.2257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]