Abstract

Background

Rubefacients (containing salicylates or nicotinamides) cause irritation of the skin, and are believed to relieve various musculoskeletal pains. They are available on prescription, and are common components in over-the-counter remedies. A non-Cochrane review in 2004 found limited evidence for efficacy.

Objectives

To review current evidence for efficacy and safety of topically applied rubefacients in acute and chronic painful musculoskeletal conditions in adults.

Search methods

Cochrane CENTRAL, MEDLINE, EMBASE, the Oxford Pain Relief Database, and reference lists of articles were searched; last search December 2008.

Selection criteria

Randomised, double blind, placebo or active controlled clinical trials of topical rubefacient for musculoskeletal pain in adults, with at least 10 participants per treatment arm, and reporting outcomes at close to 7 (minimum 3, maximum 10) days for acute conditions and 14 (minimum 7) days or longer for chronic conditions.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed trials for inclusion and quality, and extracted data. Relative benefit or risk and number needed to treat to benefit or harm (NNT or NNH) were calculated with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Acute and chronic conditions were analysed separately.

Main results

Six placebo and one active controlled studies (560 and 137 participants) in acute pain, and seven placebo and two active controlled studies (489 and 90 participants) in chronic pain were included. All used topical salicylates. The evidence in acute conditions was not robust; using only better quality, valid studies, there was no difference between topical rubefacient and topical control, though overall, including lower quality studies, the NNT for clinical success compared with placebo was 3.2 (95% CI: 2.4 to 4.9). In chronic conditions the NNT was 6.2 (95% CI: 4.0 to 13) compared with topical placebo. Adverse events and withdrawals occurred more often with rubefacients than placebo, but analyses were sensitive to inclusion of individual studies, so not robust. There were insufficient data to draw conclusions against active controls.

Authors’ conclusions

The evidence does not support the use of topical rubefacients containing salicylates for acute injuries, and suggests that in chronic conditions their efficacy compares poorly with topical non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Topical salicylates seem to be relatively well tolerated in the short-term, based on limited data. There is no evidence at all for topical rubefacients with other components.

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH): Acute Disease; Administration, Topical; Chronic Disease; Irritants [* administration & dosage; adverse effects]; Musculoskeletal Diseases [*drug therapy]; Pain [*drug therapy]; Salicylates [*administration & dosage; adverse effects]

MeSH check words: Adult, Humans

BACKGROUND

Rubefacients cause irritation of the skin, and are believed to relieve pain in muscles, joints and tendons, and other musculoskeletal pains in the extremities by counter-irritation (BNF 2008). The term “counter-irritant” derives from the fact that these agents cause a reddening of the skin by causing the blood vessels of the skin to dilate, which gives a soothing feeling of warmth. The term counter-irritant refers to the idea that irritation of the sensory nerve endings alters or offsets pain in the underlying muscle or joints that are served by the same nerves (Morton 2002). By contrast, topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) penetrate the skin and underlying tissues where they inhibit cyclo-oxygenase enzymes responsible for prostaglandin biosynthesis and the development of inflammation.

There has been confusion about which compounds should be classified as rubefacients. Some compounds, such as salicylates, are related pharmacologically to aspirin and NSAIDs, but for the form that they are often used in for topical products (often as amine derivatives) their principal action is to act as skin irritants. Capsaicin applied topically can produce a burning sensation at the application site, and has also been grouped with rubefacients, although the mechanism of pain relief is to desensitise nociceptors (sensory receptors that send signals that cause the perception of pain in response to potentially damaging stimulus). This review will include salicylates and nicotinate esters, but not capsaicin as this is covered in another review (Derry 2008a).

In 2006 there were almost 1.8 million prescriptions for rubefacients in England, of which around half were for Movelat gel or cream (PACT 2006). Many products on sale directly to the public contain rubefacients. The quality and cost of these are unknown, but the latter is likely to be substantial.

A systematic review of rubefacients in 2004 (Mason 2004a) found only 12 trials that were small and of only moderate quality and validity. This review concluded that, at best, rubefacients containing salicylates had moderate to poor efficacy in chronic pain and good efficacy in acute pain. These results were not robust due to the very limited data. An updated review of evidence for their efficacy is needed for commissioners (purchasers of healthcare), prescribers and consumers to make informed choices about their use.

This review is one of a series on topical analgesics, including topical capsaicin (Derry 2008a), and topical NSAIDs in acute (Massey 2008) and chronic pain (Derry 2008b).

OBJECTIVES

To review the evidence from controlled trials on the efficacy and safety of topically applied rubefacients in acute and chronic pain in adults.

METHODS

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled double blind trials comparing topical rubefacient with placebo or other active treatment for acute pain (strains, sprains and sports injuries) or chronic pain (arthritis, musculoskeletal problems), with at least 10 participants per treatment arm. Outcomes close to seven days (minimum three days) for acute conditions, and 14 days (minimum seven days) for chronic conditions were sought. Trials published only as abstracts or studying experimentally induced pain were excluded.

Types of participants

Adult participants (16 years or more) with acute or chronic pain of at least moderate intensity resulting from any cause.

Types of interventions

Included studies had at least one treatment arm using a topical rubefacient (including salicylates and nicotinate esters, but not capsaicin alone, but capsaicin as an additional component of the principal ingredient will be included), and a comparator arm using placebo or other active treatment, with treatment applied at least once daily.

Types of outcome measures

Information was sought on participant characteristics: age, sex, and condition to be treated.

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome was “clinical success”, defined as a 50% reduction in pain, or equivalent measure such as a “very good” or “excellent” global assessment of treatment, or “none” or “slight” pain on rest or movement, measured on a categorical scale (Moore 1998). The following hierarchy of outcomes, in order of preference, was used to extract data for the primary outcome:

patient-reported reduction in pain of at least 50%;

patient-reported global assessment of treatment;

pain on movement;

pain on rest, or spontaneous pain;

undefined “improvement”.

Only patient-reported outcomes were used. Physician- or investigator-reported outcomes of efficacy were not used.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes sought were:

numbers of participants with adverse events: local and systemic, and cough;

numbers of withdrawals: all cause, lack of efficacy, adverse events.

Outcomes were reported after different durations of treatment, so care was taken to extract data reported as close to specified times as possible, and not less than the minimum. Longer duration outcomes were extracted where available. Care was also taken to determine whether reported adverse events were comprehensively reported, and the methods of ascertainment.

Search methods for identification of studies

The following databases were searched:

MEDLINE via Ovid (to December 2008);

EMBASE via Ovid (to December 2008);

Cochrane CENTRAL (December 2008);

Oxford Pain Relief Database (Jadad 1996a).

See Appendix 1 for the MEDLINE search strategy, Appendix 2 for the EMBASE search strategy and Appendix 3 for the CENTRAL search strategy.

Language

No language restriction was applied.

Unpublished studies

Manufacturers have previously been asked for details of unpublished studies (Mason 2004a), and new manufacturers or UK distributors were sought to ask them about unpublished studies.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently selected the studies for inclusion, assessed methodological quality, and extracted data. Disagreements were resolved through discussion with an adjudicator.

Selection of studies

Titles and abstracts of studies identified by the searches were reviewed on screen to eliminate those that clearly did not satisfy inclusion criteria. Full reports of the remaining studies were obtained to determine inclusion in the review. Cross-over trials were considered only if data from the first treatment period was reported separately. Studies in oral, ocular or buccal diseases were not included.

Assessment of methodological quality

Included studies were assessed for quality using a five-point scale (Jadad 1996b) that considers randomisation, blinding, and study withdrawals and dropouts.

Trial validity was assessed using a 16-point scale (Smith 2000).

Data extraction

Information on participants, interventions, and outcomes from the original reports was abstracted into a standard data extraction form. Study authors were not contacted for further information.

Data analysis

Intention-to-treat analyses were performed. Homogeneity was examined visually using L’Abbé plots (L’Abbé 1987).

Where appropriate, data for each dichotomous outcome was pooled and used to calculate relative benefit (RB) estimates with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using the fixed-effect model (Morris 1995). Numbers needed to treat to benefit (NNT) with 95% CIs were calculated using the pooled number of events by the method of Cook and Sackett (Cook 1995). A statistically significant benefit of active treatment over control was assumed when the lower limit of the 95% CI of the RB was greater than the number one. A statistically significant benefit of control over active treatment was assumed when the upper limit of the 95% CI was less than the number one. Number needed to treat to harm (NNH), and relative risk (RR) were calculated for these outcomes in the same way as for NNTs and RB.

Data for acute and chronic conditions were analysed separately for efficacy. For each category we combined data for all rubefacients versus placebo for analysis of the primary outcome of clinical success, with sensitivity analyses planned for:

outcome (undefined “improvement” versus others);

high versus low quality (two versus three or more) and validity (eight or less versus nine or more) scores;

study size (39 or less versus 40 or more participants in both treatment arms);

time of assessment of primary outcome (six days or less versus seven days or more for acute conditions and 13 days or less versus 14 days or more for chronic condition).

For secondary outcomes relating to adverse events and withdrawals, data for all rubefacients versus placebo were combined. Trials comparing rubefacients with an active comparator were also examined.

At least 200 patients were required in any of these different contexts before information was pooled (Moore 1998b).

RESULTS

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies.

No new manufacturers of topical rubefacients were identified, and so no new approaches for unpublished studies could be made.

Results of the search

Searches identified 28 potentially relevant studies. Twelve were excluded after reading the full publication (Crielaard 1986; Dettoni 1982; He 2006; Heindl 1977; Howell 1955; Jolley 1972; Kantor 1990; Kleinschmidt 1975; Pasila 1980; Shamszad 1986; von Batky 1971; Weisinger 1970) and 16 were included (Algozzine 1982; Camus 1975; Diebschlag 1987; Frahm 1993; Geller 1980; Ginsberg 1987; Golden 1978; Ibanez 1988; Lester 1981; Lobo 2004; Rothhaar 1982; Rutner 1995; Shackel 1997; Stam 2001; von Bach 1979; Wanet 1979). The review by Mason 2004a identified 14 of the studies included here. In addition our searches identified an active controlled study (Ibanez 1988), and a placebo controlled study (Lobo 2004). Neither provided useable efficacy data but both had information on adverse events. We also identified a publication (Shamszad 1986) that republished the results of another study (Golden 1978) alongside data from an additional study, which was subsequently excluded from the review because there were no extractable data.

Included studies

Six placebo controlled studies of acute injuries were included (Diebschlag 1987; Frahm 1993; Ginsberg 1987; Lester 1981; Rothhaar 1982; Stam 2001) with 560 participants in total, of which 236 were from two studies that did not have useable information for efficacy (Diebschlag 1987; Frahm 1993) and provided data for withdrawals and adverse events only. One acute study was identified with an active comparator and 137 participants (Ibanez 1988).

Seven placebo controlled studies in chronic pain conditions were included (Algozzine 1982; Camus 1975; Lobo 2004; Rutner 1995; Shackel 1997; von Bach 1979; Wanet 1979), involving 489 participants (including 26 receiving both treatment and placebo in a cross-over trial), of which 52 were in a study providing adverse event data, but no useable data for efficacy (Lobo 2004). Two studies with active comparators in chronic pain conditions, involving 90 participants, were also included (Geller 1980; Golden 1978). All studies used salicylates as the rubefacient, with trolamine salicylate (Algozzine 1982; Golden 1978), diethylamine salicylate (Camus 1975; Geller 1980; Rothhaar 1982; Wanet 1979), salicylic acid (Diebschlag 1987; Frahm 1993; Lester 1981), benzydaminesalicylate (Ibanez 1988), methyl salicylate (Lobo 2004), glycol salicylate (Rutner 1995; Stam 2001), copper salicylate (Shackel 1997), ethylene glycol monosalicylate ester (von Bach 1979), or a mixture of salicylates (Ginsberg 1987). Formulations varied widely. A variety of additional components were added to the principal ingredient, such as the local anaesthetic myrtecaine (Camus 1975; Wanet 1979), capsicum oleoresin (Ginsberg 1987; Stam 2001), or adrenal extract (Diebschlag 1987; Lester 1981).

The active comparators used were oral aspirin (Golden 1978), the topical NSAIDs etofenamate (Geller 1980), and fepradinol (Ibanez 1988). In some studies participants received additional oral analgesics or physical therapy.

In two studies it was unclear as to whether the comparator was a placebo or active control, with one study in acute low back pain using a ‘homeopathic’ control (containing appreciable concentrations of herbal ingredients with no known analgesic effects) (Stam 2001), and one study in chronic musculoskeletal conditions using a lower concentration of salicylate (von Bach 1979). We analysed these studies as placebo controlled trials, but subject to sensitivity analysis.

Of the studies in acute conditions, two were of seven days duration (Lester 1981; Stam 2001), three between seven and 14 days (Frahm 1993; Ibanez 1988; Rothhaar 1982), and two for 14 days or more (Diebschlag 1987; Ginsberg 1987). Three studies in chronic conditions lasted for seven days (Algozzine 1982; Geller 1980; Golden 1978), one for ten days (Camus 1975), and five for 14 days or more (Lobo 2004; Rutner 1995; Shackel 1997; von Bach 1979; Wanet 1979).

Acute conditions studied were sprains (Diebschlag 1987; Frahm 1993; Lester 1981) and other sports injuries (Ibanez 1988; Rothhaar 1982), or acute lower back pain (Ginsberg 1987; Stam 2001). Chronic conditions included articular musculoskeletal pain (Algozzine 1982; Geller 1980; Golden 1978; Shackel 1997; von Bach 1979; Wanet 1979), extra-articular pain (Camus 1975; Geller 1980; Golden 1978; von Bach 1979), back pain (Geller 1980; Rutner 1995; von Bach 1979; Wanet 1979), and temporomandibular disorders (Lobo 2004).

Risk of bias in included studies

All studies were randomised and double blind. Of those in acute conditions, two had a quality score of two (Ibanez 1988; Lester 1981), two of three (Frahm 1993; Ginsberg 1987), two of four (Rothhaar 1982; Stam 2001), and one of five (Diebschlag 1987). One study had a validity score of seven (Ibanez 1988), one of eight (Rothhaar 1982), one of nine (Ginsberg 1987), one of 10 (Frahm 1993), one of 11 (Lester 1981), and two of 12 (Diebschlag 1987; Frahm 1993).

In chronic conditions there were five studies with a quality score of three (Camus 1975; Geller 1980; Lobo 2004; Rutner 1995; Wanet 1979), two of four (Algozzine 1982; Golden 1978), and two of five (Shackel 1997; von Bach 1979). Two studies had validity scores of seven (Geller 1980; Lobo 2004), two of nine (Golden 1978; Wanet 1979); three of 10 (Algozzine 1982; Camus 1975; von Bach 1979), one of 11 (Shackel 1997), and one of 12 (Rutner 1995).

A quality score of three out of five or more is considered to indicate reasonable study quality (Jadad 1996b) and five of the seven studies in acute conditions and all eight in chronic conditions met this criterion. Validity scores of nine out of 16 or more are considered to represent reasonable study validity (Smith 2000) and five of the seven studies in acute conditions and seven of the nine in chronic conditions met this criterion. Most studies lost points on the validity scale for not being convincingly double blind. Other common reasons were small sample size, low baseline pain or lack of internal sensitivity, unclear or inadequate management of withdrawals, and unclear or inadequate statistical analyses. Even if studies demonstrated internal sensitivity they typically included participants with levels of pain that were unclear or of only mild intensity.

Although outcomes were generally defined, a wide variety of scales were used to assess efficacy. Adverse events and withdrawals were generally poorly reported with little detail provided. Even if the application schedule was specified, most studies did not provide details of the volume of cream applied.

Effects of interventions

Summaries of efficacy outcomes are provided in Table 1 and of adverse events and withdrawals in Table 2. There were insufficient data for sensitivity analyses comparing two groups, such as higher versus lower quality studies, so sensitivity analyses were performed by omitting studies with less desirable characteristics (Table 3; Table 4; Table 5). Because there were a small number of studies with a wide variety of formulations it was not possible to assess dose-response relationships. Due to insufficient data it was not possible to perform additional post hoc sensitivity analyses of particular salicylate formulations, most additional active ingredients, and different musculoskeletal conditions.

Table 1.

Summary of outcomes - efficacy and rescue medication

| Analgesia | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study ID | Treatment | Outcome measure | Success | Rescue Medication |

| Acute | ||||

| Diebschlag 1987 | (1) Salicylate, adrenal extract, and mucopolysaccharide ointment (Mobilat) (2) Placebo ointment |

Movement pain on 100 mm VAS at: (a) 8 days (b) 15 days |

No dichotomous data (a) Significant difference in favour of (1) (b) Significant difference in favour of (1) |

No data |

| Frahm 1993 | (1) Salicylate and mucopolysaccharide cream (Movelat) (2) Placebo cream |

Movement pain on 100 mm VAS at: (a) 9 days (b) 11 days |

No dichotomous data (a) Significant difference in favour of (1) (b) No significant difference |

No data |

| Ginsberg 1987 | (1) Salicylate and capsicum oleoresin ointment (Rado-Salil) (2) Placebo ointment |

Patient global assessment (‘excellent’ or ‘good’) at: (a) 3 days (b) 14 days |

(a) (1) 5/20 (2) 0/20 (b) (1) 10/20 (2) 2/20 |

Total number of rescue tablets (250 mg paracetamol) used: (1) 24 (2) 36 |

| Ibanez 1988 | (1) Salicylate spray (2) Fepradinol spray active control |

‘Cure’ at 12 days | (1) 23/35 (2) 85/102 |

No data |

| Lester 1981 | (1) Salicylate, adrenal extract, and mucopolysaccharide gel (Movelat) (2) Placebo gel |

Relief of pain by 7 days | (1) 18/20 (2) 13/22 |

No data |

| Rothhaar 1982 | (1) Salicylate gel (Reparil-Gel) (2) Placebo gel |

Patient global assessment (‘very good’ or ‘good’) at 9 days | (1) 37/39 (2) 3/42 |

No data |

| Stam 2001 | (1) Salicylate, nicotinate, capsicum oleoresin, and histamine gel (Cremor Capsici Compositus FNA) (2) Herbal gel (Spiroflor SRL) active control |

80% reduction in pain on 100 mm VAS at 7 days | (1) 41/78 (2) 40/83 |

Number using rescue medication (paracetamol): (1) 65/82 (2) 56/75 |

| Chronic | ||||

| Algozzine 1982 | (1) Salicylate cream (Myoflex) (2) Placebo cream |

Pain relief score at 7 days favours (1) or (2) | (1) 10/26 (2) 8/26 |

No data |

| Camus 1975 | (1) Salicylate and myrtecaine cream (Algesal Suractive) (2) Placebo cream |

Improvement in rest pain score at 10 days | (1) 8/10 (2) 3/10 |

No data |

| Geller 1980 | (1) Salicylate and heparin gel (Dolo-Menthoneurin) (2) Etofenamate gel active control |

Patient global score (‘very good’ or ‘good’) after phase 1 at 7 days | (1) 24/25 (2) 8/25 |

No data |

| Golden 1978 | (1) Salicylate cream (Aspercreme) + placebo tablets (2) Aspirin tablets + placebo cream active control |

Patient global assessment of pain relief (‘excellent’ or ‘good’) at 7 days | (1) 13/20 (2) 10/20 |

No data |

| Lobo 2004 | (1) Salicylate cream(Theraflex-TMJ) (2) Placebo cream |

Spontaneous pain VAS (10 cm) at: (a) 15 days (b) 10 days |

No dichotomous data (a) Significant difference in favour of (1) (b) No significant difference |

No data |

| Rutner 1995 | (1) Salicylate gel (Phardol-Mono) (2) Placebo gel |

Drop-out ‘pain free’ by day 14 | (1) 21/54 (2) 18/59 |

No data |

| Shackel 1997 | (1) Salicylate gel (2) Placebo gel |

Patient global assessment (‘very good’ or ‘good’) at 28 days | (1) 22/58 (2) 21/56 |

Number using rescue medication (paracetamol): (1) 43/56 (2) 39/55 Average dose (mg/day): (1) 555 (2) 600 |

| von Bach 1979 | (1) Salicylate and nonivamide in heparin and salicylate ointment (Enelbin-Rheuma) (2) Salicylate in heparin and salicylate ointment active control |

Global assessment (‘very good’ or ‘good’) at 14 days | (1) 27/50 (2) 10/50 |

No data |

| Wanet 1979 | (1) Salicylate and myrtecaine cream (Algesal Suractive) (2) Placebo cream |

Rest pain score at 15 days | (1) 15/32 (2) 4/24 |

No data |

Table 2.

Summary of outcomes - withdrawals and adverse events

| Withdrawals and exclusions | Adverse events | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study ID | Treatment | All withdrawals and exclusions | Lack of efficacy | Adverse events | All adverse events | Local adverse events |

| Algozzine 1982 | (1) Salicylate cream (Myoflex) (2) Placebo cream |

1/26 unrelated to study | (1) 0/25 (2) 0/25 |

(1) 0/25 (2) 0/25 |

(1) 0/25 (2) 0/25 |

(1) 0/25 (1) 0/25 |

| Camus 1975 | (1) Salicylate and myrtecaine cream (Algesal Suractive) (2) Placebo cream |

No data | No data | No data | No data | No data |

| Diebschlag 1987 | (1) Salicylate, adrenal extract, and mucopolysaccharide ointment (Mobilat) (2) Placebo ointment |

No data | No data | (1) 0/40 (2) 0/40 |

(1) 0/40 (2) 0/40 |

(1) 0/40 (2) 0/40 |

| Frahm 1993 | (1) Salicylate and mucopolysaccharide cream (Movelat) (2) Placebo cream |

7/16 violation of protocol | (1) 0/78 (2) 0/78 |

(1) 0/78 (2) 0/78 |

(1) 0/78 (2) 1/78 |

(1) 0/78 (2) 1/78 |

| Geller 1980 | (1) Salicylate and heparin gel (Dolo-Menthoneurin) (2) Etofenamate gel active control |

Phase 1: (1) 0/25 (2) 0/25 |

Phase 1: (1) 0/25 (2) 0/25 |

Phase 1: (1) 0/25 (2) 0/25 Phase 2: (1) 0/25 (2) 0/25 |

Phases 1 and 2 combined: (1) 2/50 (2) 2/50 |

Phases 1 and 2 combined: (1) 2/50 (2) 2/50 |

| Ginsberg 1987 | (1) Salicylate and capsicum oleoresin ointment (Rado-Salil) (2) Placebo ointment |

No data | No data | No data | (1) 4/20 (2) 1/20 |

(1) 4/20 (2) 1/20 |

| Golden 1978 | (1) Salicylate cream (Aspercreme) + placebo tablets (2) Aspirin tablets + placebo cream active control |

(1) 1/20 (2) 8/20 |

(1) 1/20 (2) 2/20 |

(1) 0/20 (2) 6/20 |

(1) 3/20 (2) 12/20 |

(1) 0/20 (2) 0/20 |

| Ibanez 1988 | (1) Salicylate spray (2) Fepradinol spray active control |

No data | No data | (1) 0/35 (2) 0/102 |

(1) 0/35 (2) 0/102 |

(1) 0/35 (2) 0/102 |

| Lester 1981 | (1) Salicylate, adrenal extract, and mucopolysaccharide gel (Movelat) (2) Placebo gel |

8/50 4 excluded due to fractures, 4 lost to follow-up | No data | No data | (1) 0/20 (2) 2/22 |

(1) 0/20 (2) 2/22 |

| Lobo 2004 | (1) Salicylate cream (Theraflex-TMJ) (2) Placebo cream |

No data | No data | No data | (1) 2/26 (2) 2/26 |

(1) 2/26 (2) 2/26 |

| Rothhaar 1982 | (1) Salicylate gel (Reparil-Gel) (2) Placebo gel |

(1) 13/50 11 with no data, rest lack of efficacy (2) 24/50 8 with no data, rest lack of efficacy |

(1) 2/39 (2) 16/42 |

(1) 0/39 (2) 0/42 |

(1) 0/39 (2) 0/42 |

(1) 0/39 (2) 0/42 |

| Rutner 1995 | (1) Salicylate gel (Phardol-Mono) (2) Placebo gel |

7/136 lost to follow-up | No data | No data | (1) 1/54 unrelated disc prolapse (2) 0/59 |

(1) 0/54 (2) 0/59 |

| Shackel 1997 | (1) Salicylate gel (2) Placebo gel |

(1) 15/58 14 withdrew during trial, 1 lost to follow-up (2) 10/58 2 withdrew before treatment, 7 withdrew during trial, 1 lost to follow-up |

(1) 3/58 (2) 2/56 |

(1) 10/58 (2) 1/56 |

(1) 48/58 (2) 29/56 |

Total number of adverse events: (1) 80 (2) 27 |

| Stam 2001 | (1) Salicylate, nicotinate, capsicum oleoresin, and histamine gel (Cremor Capsici Compositus FNA) (2) Herbal gel (Spiroflor SRL) active control |

(1) 4/78 lost to follow-up (2) 2/83 1 death, 1 lost to follow-up |

No data | (1) 8/74 (2) 1/82 unrelated death |

(1) 19/74 (2) 10/82 |

(1) 18/74 (2) 3/81 |

| von Bach 1979 | (1) Salicylate and nonivamide in heparin and salicylate ointment (Enelbin-Rheuma) (2) Salicylate in heparin and salicylate ointment active control |

(1) 0/50 (2) 2/50 |

(1) 1/50 (2) 0/50 |

(1) 0/50 (2) 2/50 |

(1) 0/50 (2) 2/50 |

(1) 0/50 (2) 2/50 |

| Wanet 1979 | (1) Salicylate and myrtecaine cream (Algesal Suractive) (2) Placebo cream |

No data | No data | No data | No data | No data |

Table 3.

Sensitivity analyses - acute efficacy

| Subgroup | Studies | Participants | Fixed-effect RR (95% CI) | NNT (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All acute studies | 4 | 324 | 1.9 (1.5 to 2.5) | 3.2 (2.4 to 4.9) |

| Excluding Lester 1981 1 | 3 | 282 | 2.0 (1.5 to 2.7) | 3.2 (2.4 to 5.0) |

| Excluding validity < 9 | 3 | 243 | 1.3 (1.01 to 1.7) | not calculated |

| Excluding quality < 3 or validity < 9 | 2 | 201 | 1.2 (0.90 to 1.7) | not calculated |

| Outcomes ≥ 7 days | 3 | 202 | 1.8 (1.4 to 2.4) | 3.1 (2.3 to 4.8) |

| Outcomes ≥ 7 days2 | 4 | 324 | 2.0 (1.5 to 2.5) | 3.1 (2.3 to 4.4) |

Quality score < 3, outcome measure unspecified ‘improvement’

Including additional data at 14 days from Ginsberg 1987

Table 4.

Sensitivity analyses - chronic efficacy

| Subgroup | Studies | Participants | Fixed-effect RR (95% CI) | NNT (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All chronic studies | 6 | 429* | 1.6 (1.2 to 2.0) | 6.2 (4.0 to 13) |

| Excluding von Bach 1979 1 | 5 | 329* | 1.4 (1.03 to 1.8) | 8.8 (4.7 to 70) |

| Excluding Shackel 1997 2 | 5 | 315* | 1.9 (1.4 to 2.5) | 4.6 (3.2 to 8.5) |

| Group size ≥ 40 | 3 | 327 | 1.5 (1.1 to 2.0) | 7.4 (4.2 to 31) |

| Outcome measure global assessment or categorical score | 4 | 290 | 1.8 (1.3 to 2.5) | 4.8 (3.2 to 10) |

| Duration ≥ 14 days | 4 | 383 | 1.6 (1.2 to 2.1) | 6.3 (4.0 to 16) |

Including 26 patients in a crossover trial (Algozzine 1982)

Lower dose salicylate control

Application to a site remote from pain

Table 5.

Sensitivity analyses - adverse events and withdrawals

| Event rate (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subgroup | Rubefacient | Placebo | Studies (with ≥ 1 event) | Participants (in studies with ≥ 1 event) | Fixed effect RR (95% CI) | NNH (95% CI) |

| Any adverse event | ||||||

| All studies | 74/484 (15%) | 47/500 (9%) | 8 | 773 | 1.6 (1.2 to 2.0) | 13 (7.9 to 43) |

| All studies excluding Shackel 1997 1 | 26/426 (6%) | 18/44 (4%) | 7 | 659 | 1.5 (0.88 to 2.6) | not calculated |

| All studies excluding Stam 2001 2 and von Bach 1979 3 | 55/360 (15%) | 35/368 (10%) | 6 | 517 | 1.5 (1.1 to 2.0) | 12 (6.8 to 67) |

| Acute studies only | 23/271 (8%) | 14/284 (5%) | 4 | 394 | 1.7 (0.96 to 3.2) | not calculated |

| Acute excluding Stam 2001 2 | 4/197 (2%) | 4/202 (2%) | 3 | 238 | 1.03 (0.30 to 3.5) | not calculated |

| Chronic studies only | 51/213 (24%) | 33/216 (15%) | 4 | 379 | 1.5 (1.1 to 2.0) | 10 (5.5 to 68) |

| Chronic excluding Shackel 1997 1 | 3/155 (2%) | 4/160 (3%) | 3 | 265 | 0.82 (0.23 to 2.9) | not calculated |

| Chronic excluding von Bach 1979 3 | 51/163 (31%) | 31/166 (19%) | 3 | 279 | 1.6 (1.2 to 2.1) | 6.7 (3.9 to 23) |

| Local adverse events | ||||||

| All studies | 24/426 (6%) | 11/443 (2%) | 6 | 545 | 2.2 (1.1 to 4.1) | 20 (11 to 140) |

| All studies excluding Stam 2001 2 and von Bach 1979 3 | 6/302 (2%) | 6/312 (2%) | 4 | 290 | 1.02 (0.37 to 2.8) | not calculated |

| Acute studies only | 22/271 (8%) | 7/283(2%) | 4 | 393 | 3.1 (1.4 to 6.7) | 13 (7.5 to 37) |

| Acute excluding Stam 2001 2 | 4/197 (2%) | 4/202 (2%) | 3 | 238 | 1.03 (0.30 to 3.5) | not calculated |

| Withdrawals due to adverse events | ||||||

| All studies | 18/364 (5%) | 4/373 (1%) | 3 | 370 | 4.2 (1.5 to 12) | 13 (7.9 to 35) |

| Chronic studies only | 10/133 (8%) | 3/131 (2%) | 2 | 214 | 2.9 (0.88 to 9.7) | not calculated |

High event rate

Herbal control

Lower dose salicylate control

There was considerable heterogeneity amongst trials, particularly for acute conditions. Using a random-effects rather than a fixed-effect model (Table 6) to estimate RBs made little difference to the chronic studies but increased the estimated effect size in acute studies. Examining relative harms reveals that estimates for all adverse events and all withdrawals remain similar, but the effect sizes for local adverse events and withdrawals due to adverse events decrease and become non significant.

Table 6.

Random-effects model

| Outcome | Fixed-effect RR estimate (95% CI) | Random-effects RR estimate (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Acute efficacy | 1.9 (1.5 to 2.5) | 2.7 (1.05 to 7.0) |

| Chronic efficacy | 1.6 (1.2 to 2.0) | 1.6 (1.1 to 2.4) |

| Any adverse events | 1.6 (1.2 to 2.0) | 1.6 (1.3 to 2.1) |

| Local adverse events | 2.2 (1.1 to 4.1) | 1.3 (0.35 to 4.7) |

| All withdrawals | 0.85 (0.57 to 1.3) | 0.92 (0.41 to 2.1) |

| Withdrawal due to adverse events | 4.2 (1.5 to 12) | 3.4 (0.40 to 28) |

Number of participants achieving clinical success (at least 50% pain relief or equivalent)

(Table 1)

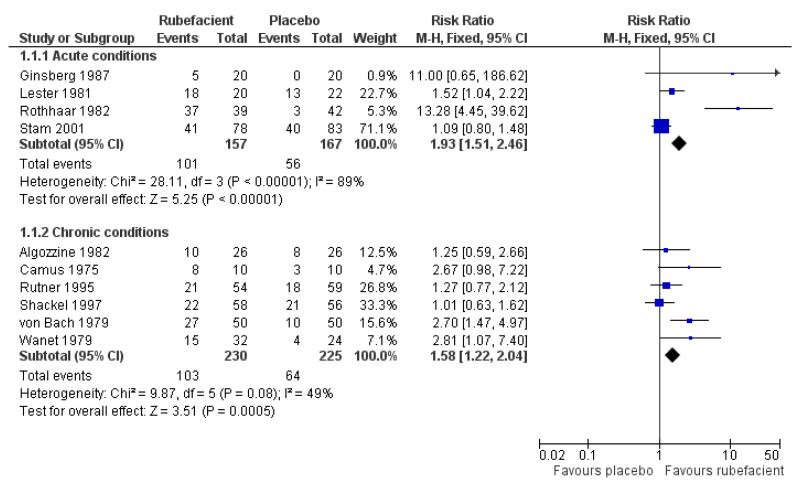

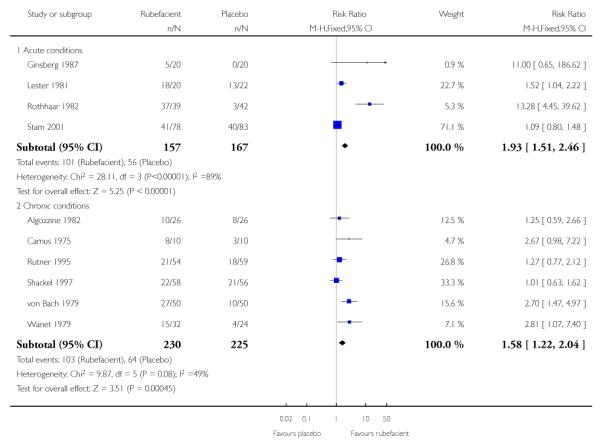

Acute conditions

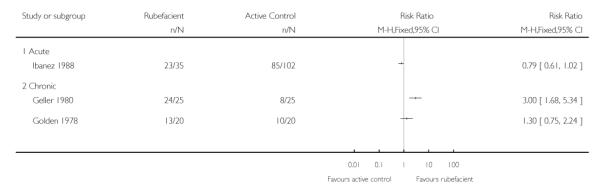

Four placebo controlled studies with 324 participants provided data for efficacy analysis (Ginsberg 1987; Lester 1981; Rothhaar 1982; Stam 2001). The proportion of participants achieving 50% pain relief or equivalent at seven days was 64% (range 25 to 95%; 101/157) for the rubefacient group, and 34% (0 to 59%; 56/167) for the placebo group, giving a RB of treatment of 1.9 (95% CI 1.5 to 2.5) and a NNT of 3.2 (95% CI 2.4 to 4.9) (Analysis 1.1; Figure 1; Table 3). Because studies were small, with high variability between them, we also checked this results using random-effects; it remained significant, with a RR of 2.7 (95% CI 1.1 to 7.0) (Table 6).

Figure 1.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Rubefacient versus placebo, outcome: 1.1 Clinical success (e.g. 50% reduction in pain).

Only one active controlled study was identified (Ibanez 1988); this was of low quality and validity. There were insufficient data for statistical analysis.

Sensitivity analyses

Study size

Only one study (Stam 2001) had 40 participants in both treatment arms, so a sensitivity analysis could not be performed for effect of study size.

Study quality and validity

Excluding the single study with a quality score < 3 (Lester 1981)did not strongly affect the estimated RB of treatment (2.0 (95% CI 1.5 to 2.5)), but excluding the single study with a validity score < 9 (Rothhaar 1982) reduced the estimated benefit to minimal statistical significance (1.3 (95% CI 1.0 to 1.7)) and excluding both these studies (leaving Ginsberg 1987 and Stam 2001) resulted in an estimated benefit that was not statistically significant (1.2 (95% CI 0.90 to 1.7)).

Study outcome

Only one study used an undefined ‘improvement’ measure of clinical success (Lester 1981) and excluding this study did not strongly affect the estimated benefit, as described above. One study had the efficacy outcome measured at < 7 days (Ginsberg 1987) and excluding this study did not strongly affect the estimated RB (1.8 (95% CI 1.4 to 2.4)), nor did including additional data from this study measured at 14 days (2.0 (95% CI 1.5 to 2.5)).

Post hoc analyses

The acute study of Stam 2001 used a control treatment containing herbal ingredients that could potentially represent an active control and underestimate the effect of the rubefacient treatment. With 161 participants it was not possible to remove this study from the analysis without reducing the overall number of participants to below 200, but it is worth noting that this study did not demonstrate a benefit of rubefacient compared with placebo (RB of treatment 1.1 (0.80 to 1.5)) and thus biases downwards the estimated benefit of rubefacients in acute conditions.

Excluding the single study using adrenal extracts and mucopolysaccharide (Lester 1981) made minimal difference to the overall effect, whilst analysis of the two rubefacients containing low levels of capsicum oleoresin (Ginsberg 1987; Stam 2001) resulted in no significant benefit with rubefacient when these studies were combined (see above under ‘Study quality and validity’).

Chronic conditions

Six placebo controlled studies with 455 participants provided data for efficacy analysis (Algozzine 1982; Camus 1975; Rutner 1995; Shackel 1997; von Bach 1979; Wanet 1979). The proportion of participants achieving 50% pain relief or equivalent at 14 days was 45% (range 38 to 80%; 103/230) for the rubefacient group, and 28% (17 to 38%; 64/225) for the placebo group, giving a RB of treatment of 1.6 (1.2 to 2.0) and a NNT of 6.2 (4.0 to 13) (Analysis 1.1; Figure 1; Table 4).

Two active controlled studies with outcomes at seven days were identified, the first (Geller 1980) had low validity and found a benefit of rubefacient compared with the topical NSAID etofenamate (though this topical NSAID has no evidence of efficacy (Mason 2004b)), and the second (Golden 1978) found no benefit compared with oral aspirin (Analysis 2.1). Studies were too small for any of these results to be robust.

Sensitivity analyses

Study quality and validity

There were no low quality or low validity placebo controlled trials in chronic pain, so sensitivity analyses were not performed for these criteria.

Study size

There were insufficient data for a formal analysis of study size. Three placebo controlled studies had group sizes < 40 (Algozzine 1982; Camus 1975; Wanet 1979) and excluding these studies slightly reduced the RB to 1.5 (1.1 to 2.0), giving a NNT 7.4 (4.2 to 31).

Study outcome

Two placebo controlled studies used undefined ‘improvement’ measures of clinical success (Algozzine 1982; Rutner 1995) and excluding these studies increased the estimated RB (1.8 (95% CI 1.3 to 2.5)). Two studies had efficacy outcomes measured at < 14 days (Algozzine 1982; Camus 1975) but excluding these did not strongly affect the estimated benefit (1.6 (1.2 to 2.1)).

Post hoc analyses

One study in chronic pain (von Bach 1979) used a control treatment containing lower doses of salicylate, which could be considered an active control and underestimate the beneficial effect of rubefacients. Excluding this study reduced the estimated RB of rubefacients to bare statistical significance (1.4 (95% CI 1.03 to 1.8)). In Shackel 1997 the rubefacient was applied distant to the site of pain, which could underestimate the benefit, and excluding this study increased the RB of rubefacients (1.9 (95% CI 1.4 to 2.5)). Omitting studies using the local anaesthetic myrtecaine (Camus 1975; Wanet 1979) did not strongly affect the estimated RB (1.4 (95% CI 1.1 to 1.9)).

Adverse events

(Table 2)

Data were collected over periods of seven to 15 days, except for one study in which data were collected over four weeks (Shackel 1997).

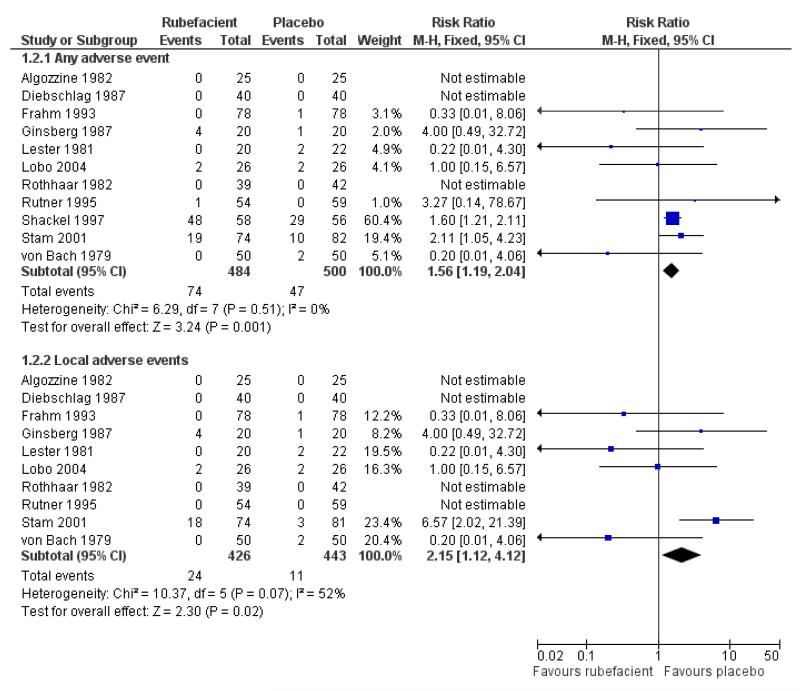

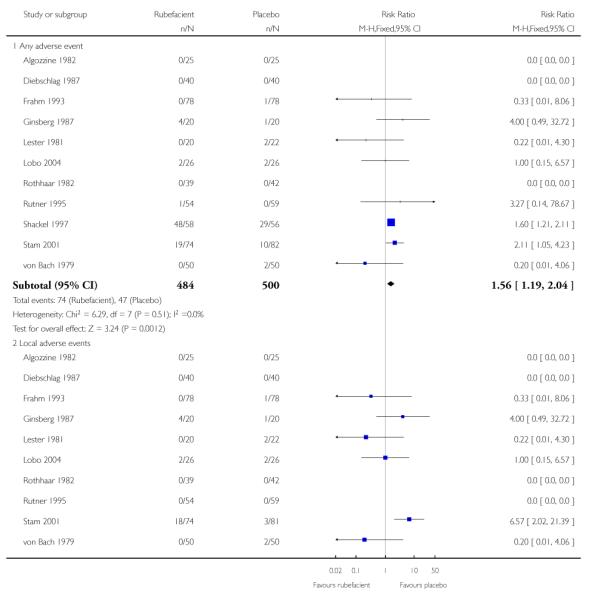

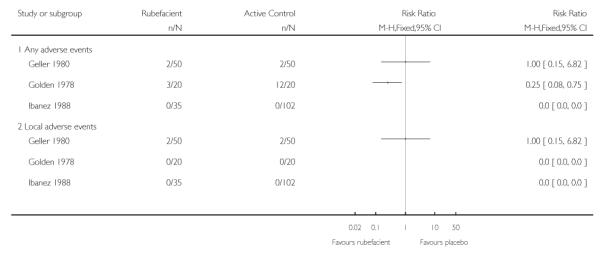

All adverse events

Eleven studies provided data on adverse events compared to placebo, six in acute conditions (Diebschlag 1987; Frahm 1993; Ginsberg 1987; Lester 1981; Rothhaar 1982; Stam 2001) and five in chronic conditions (Algozzine 1982; Lobo 2004; Rutner 1995; Shackel 1997; von Bach 1979). Three had no events in either study arm (Algozzine 1982; Diebschlag 1987; Rothhaar 1982). In all studies combined, adverse events were relatively rare with 15% (74/484, range 0 to 83%) of participants in the rubefacient group experiencing an adverse event and 9% (47/500, range 0 to 52%) in the placebo group. The relative harm with rubefacient compared to placebo was 1.6 (1.2 to 2.0), giving an NNH of 17 (9.9 to 58) (Analysis 1.2; Figure 2; Table 5). In two studies it was not clear that the control was truly a placebo (Stam 2001; von Bach 1979) and this could over estimate the rate of adverse events in the placebo group. Excluding these studies made little difference with event rates of 15% and 10% for rubefacient and placebo respectively, and the estimate of relative harm of 1.5 (1.1 to 2.0). Most of the events were in the single study lasting four weeks (Shackel 1997), which had high rates in both treatment arms, and excluding this study gave event rates of 6% and 4% for rubefacient and placebo respectively, and no significant difference between groups.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Rubefacient versus placebo, outcome: 1.4 Adverse events.

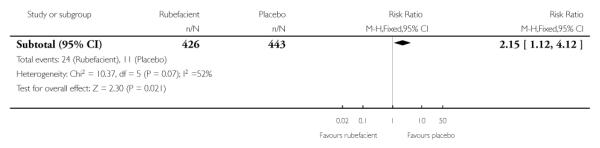

Local adverse events

Ten studies provided data on local adverse events, six in acute conditions (Diebschlag 1987; Frahm 1993; Ginsberg 1987; Lester 1981; Rothhaar 1982; Stam 2001) and four in chronic conditions (Algozzine 1982; Lobo 2004; Rutner 1995; von Bach 1979), with four having no events in either study arm (Algozzine 1982; Diebschlag 1987; Rothhaar 1982; Rutner 1995). The local adverse event rates were 6% (24/426, range 0 to 24%) and 2% (11/443, range 0 to 9%) for rubefacient and placebo groups respectively, with a significant relative harm of 2.2 (1.1 to 4.1) and an NNH of 31 (16 to 300) (Analysis 1.2; Figure 2). Excluding Stam 2001 and von Bach 1979 (control not true placebo) gave an event rate of 2% for both treatment arms.

Post hoc sensitivity analyses

Omitting the two studies in acute conditions that contained the potent irritant capsicum oleoresin (Ginsberg 1987; Stam 2001) reduced somewhat the estimated RR of adverse events to bare statistical significance (1.4 (1.03 to 1.8)). Local adverse events were reduced to 2/331 and 7/342 in the rubefacient and placebo groups respectively, with too few events for analysis.

The two active controlled trials using topical NSAIDs (Geller 1980; Ibanez 1988) found no difference in adverse event rates between the study arms, and the aspirin-controlled chronic study (Golden 1978) reported high rates of adverse events in the aspirin arm (Analysis 2.2).

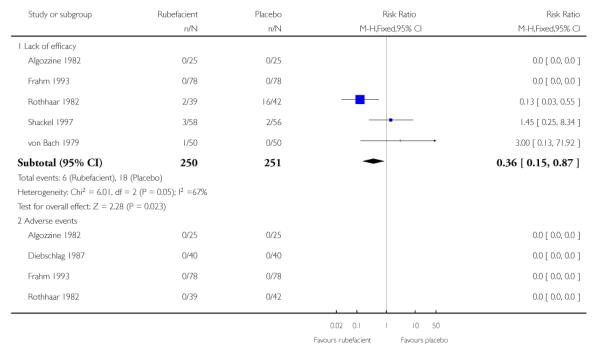

Withdrawals

(Table 2)

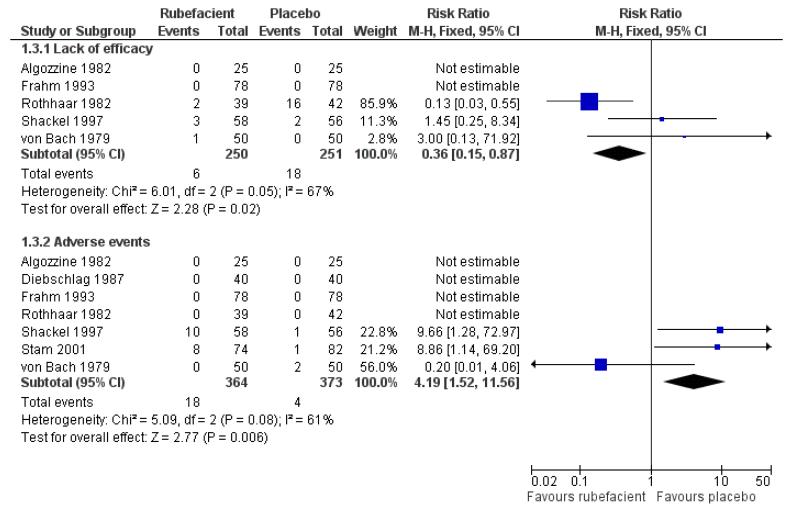

Data were collected over periods of seven to 15 days, except for one study in which data were collected over four weeks (Shackel 1997).

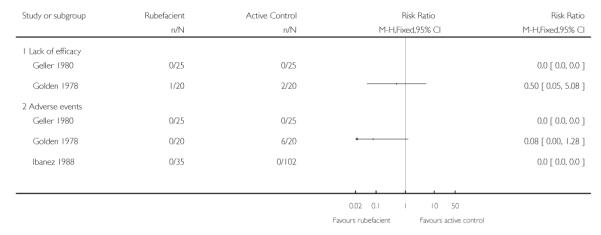

Five placebo controlled studies had information on withdrawals due to lack of efficacy, two in acute conditions (Frahm 1993; Rothhaar 1982) and three in chronic conditions (Algozzine 1982; Shackel 1997; von Bach 1979), with two having no events in either group (Algozzine 1982; Frahm 1993). The withdrawal rate due to lack of efficacy for all studies combined was 2% (6/250, range 0 to 5%) and 7% (18/251, 0 to 38%) for rubefacient and placebo respectively, giving a RR of 0.4 (0.2 to 0.9) and a number needed to treat to prevent one withdrawal (NNTp) of 21 (12 to 120) (Analysis 1.3; Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Rubefacient versus placebo, outcome: 1.2 Withdrawals.

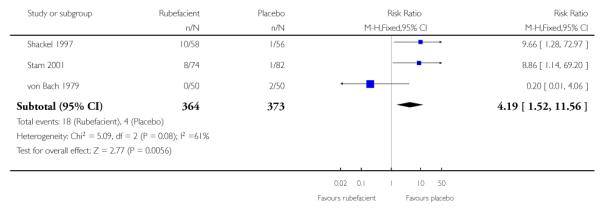

Seven placebo controlled studies provided data on withdrawals due to adverse events, four in acute conditions (Diebschlag 1987; Frahm 1993; Rothhaar 1982; Stam 2001) and three in chronic conditions (Algozzine 1982; Shackel 1997; von Bach 1979), and four of these had no events in either treatment arm (Algozzine 1982; Diebschlag 1987; Frahm 1993; Rothhaar 1982). The withdrawal rate due to adverse events was 5% (18/364, range 0 to 17%) and 1% (4/373, 0 to 4%) for rubefacient and placebo respectively, with a significant relative harm of 4.2 (1.5 to 12) and a NNH of 26 (15 to 85) (Analysis 1.3; Figure 3).

Post hoc sensitivity analyses

All 18 adverse event withdrawals with active treatment were in two studies (Stam 2001 (acute), Shackel 1997 (chronic)). Stam 2001 included the potent irritant capsicum oleoresin in the active treatment, and Shackel 1997 had data collected over four weeks. Although combining all studies gave a significantly greater risk of withdrawal due to adverse events with rubefacients than placebo, the result is not robust, since removing either of these studies resulted in no significant difference between treatment arms. The topical NSAID controlled study in chronic conditions (Geller 1980) had no withdrawals from either treatment arm, but the aspirin controlled study in chronic conditions (Golden 1978) reported one withdrawal due to lack of efficacy in the rubefacient arm, and two due to lack of efficacy and six due to adverse events in the aspirin arm (Analysis 2.3).

Withdrawals and exclusions for reasons other than lack of efficacy and adverse events were uncommon and generally due to protocol violations or loss to follow up.

See Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6 for further details.

DISCUSSION

This review identified relatively few studies of rubefacients, all of which used salicylate as the main ingredient. Studies were generally small. There were a variety of interventions and outcomes used in these studies, using a range of different methods for measuring pain intensity or pain relief.

Although the analysis of all studies in acute conditions produced a significant benefit compared with placebo at seven days, and a NNT for 50% pain relief of about three, suggesting a useful therapeutic effect of rubefacients in acute musculoskeletal injuries, this finding was based on only four heterogeneous studies. The NNT estimate was not robust to sensitivity analyses, and, in particular, exclusion of studies with low quality or validity scores produced a reduced benefit that was no longer statistically significant. We have no good evidence of efficacy of rubefacients in acute musculoskeletal conditions.

Analysis of six studies in chronic conditions produced a significant benefit compared with placebo at 14 days, with a NNT for 50% pain relief of about six, and the result was relatively robust to sensitivity analyses. This compares poorly to topical NSAIDs which have a NNT of about three compared with placebo, based on an extensive number of smaller, shorter studies, and also on recent convincing comparisons with both placebo and oral NSAIDs in large and high quality studies of up to 12 weeks in osteoarthritis (Moore 2008).

The limited data we have indicates that rubefacients were relatively well tolerated, with adverse events uncommon except for the study by Shackel 1997 which had high rates in both copper salicylate and placebo arms. Rubefacients showed a higher rate of adverse events than placebo with a risk of harm of over 1.5-fold, giving an NNH of 17 over 7 to 14 days, and a two-fold risk of local adverse events, giving an NNH of 31 over 7 to 14 days. Withdrawals due to adverse events were increased four-fold in the rubefacient group with a NNH of 26. All adverse event analyses were sensitive to the inclusion of individual studies, so should not be considered robust. There were significantly fewer withdrawals due to lack of efficacy with rubefacient than placebo, giving an NNTp of 21 over 7 to 14 days.

These findings differ slightly from the review by Mason 2004a which found a greater benefit for rubefacients in acute studies, a similar level of benefit for chronic studies, and no significant increase in the risk of adverse events. These differences are due to Mason 2004a using physician and investigator assessments of efficacy, whereas the present study only used patient assessments (or unspecified ‘improvement’), our inclusion of Stam 2001 as a placebo controlled trial, identifying additional data on adverse events, and combining events from acute and chronic trials for analysis of adverse events and withdrawals.

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) recently published a national clinical guideline for osteoarthritis, and concluded that “rubefacients are not recommended for the treatment of osteoarthritis” (NICE 2008), but these conclusions were based on only two of the studies in chronic conditions included in the current review (Algozzine 1982; Shackel 1997) plus two single dose studies (Rothacker 1994; Rothacker 1998).

There is no commonly agreed definition of a rubefacient, and considerable overlap in the chemical properties of salicylates, the most commonly used rubefacient, and other compounds such as NSAIDs or capsaicin. It is still unclear whether topical salicylates relieve pain via cyclo-oxygenase inhibition but there is little evidence that there is significant systemic absorption (Martin 2004). This is consistent with the study by Shackel 1997 which found no benefit to using a rubefacient applied distal to the site of pain.

Capsaicin is often considered distinct from other rubefacients (not least because of its extremely potent irritant effect) but recent evidence suggests that salicylates and other rubefacients, as well as miscellaneous compounds such as menthol, may act via the transient receptor potential (TRP) ion channels involved in thermal and pain sensation (Nilius 2007; Stanos 2007) in a similar manner to capsaicin and the vanilloid receptor (Nagy 2004). However, meta-analysis of topical capsaicin for chronic musculoskeletal pain calculated an NNT of eight (Mason 2004c) suggesting that capsaicin is also marginally effective.

An outstanding issue in trials of rubefacients is the question of whether it is actually possible to conduct a truly blinded trial when the definitive mechanism of action of a rubefacient is to cause local irritation to the skin, any placebo which attempted to mimic this effect would be de facto a rubefacient.

Although it has been suggested that the efficacy of topical analgesics is largely due to local rubbing, this is not compatible with results presented here, nor with large amounts of good quality studies of topical NSAIDs in acute and chronic conditions, and with comparisons both with placebo (also applied with rubbing) and oral analgesics of known efficacy (Moore 2008).

AUTHORS’ CONCLUSIONS

Implications for practice

The evidence does not support the prescription of topical rubefacients containing salicylates for either acute or chronic musculoskeletal pain, and there is no evidence at all to support the use of topical rubefacients with other components. There are insufficient data of adequate quality to judge whether rubefacients are effective for acute injuries, and the evidence for chronic conditions suggests that their efficacy compares poorly with topical NSAIDs. Topical salicylates do appear to be relatively well tolerated in the short-term, though the conclusion is limited by a relatively small number of participants.

Implications for research

Good quality RCTs of topical rubefacients are needed to legitimise their clinical use. These trials need to be large to provide evidence about harm as well as efficacy, of long duration if the intention is to use topical rubefacients in chronic painful conditions, and should use validated outcomes.

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY.

Topical rubefacients for acute and chronic musculoskeletal pain in adults

Rubefacients cause irritation and reddening of the skin, due to increased blood flow. They are believed to relieve pain in various musculoskeletal conditions, and are available on prescription and in over-the-counter remedies. This review found evidence that was limited by the quality, validity and size of the available studies, particularly for studies in acute pain conditions like strains and sprains, where there was inadequate information to support the use of rubefacients. In chronic pain conditions such as osteoarthritis the evidence was more robust, but rubefacients appear to provide useful levels of pain relief in one in six individuals over and above those who also responded to placebo. This compares poorly with topical NSAIDs where substantial amounts of good quality evidence indicate that one in every three individuals treated will experience useful levels of pain relief over and above those who also responded to placebo.

Acknowledgments

SOURCES OF SUPPORT

Internal sources

Pain Research Funds, UK.

External sources

NHS Cochrane Collaboration Programme Grant Scheme, UK.

NIHR Biomedical Research Centre Programme, UK.

Appendix 1. MEDLINE search strategy

exp Irritants/

(rubefacient OR “counter-irritant” OR “ammonium salicylate” OR “radian B” OR “benzyl nicotinate” OR kausalpunkt OR pykaryl OR rubriment OR “bornyl salicylate” OR camphor OR “choline salicylate” OR “diethylamine salicylate” OR algesal OR algoderm OR algoflex OR artogota OR “Lloyd’s cream” OR physiogesic OR rheumagel OR “transvasin heat spray” OR “diethyl salicylate” OR “ethyl nicotinate” OR mucotherm OR transvasin “PR heat spray” OR “ethyl salicylate” OR “glycol monosalicylate” OR ralgex OR salonpas OR intralgin OR “glycol salicylate” OR “algipan rub” OR menthol OR “methyl butetisalicylate” OR doloderm OR “methyl gentisate” OR “methyl nicotinate” OR “nella red oil” OR wintergreen OR “sweet birch oil” OR “methyl salicylate” OR aezodent OR argesic OR aspellin OR balmosa OR “bengue’s balsam” OR “chymol emollient balm” OR “ deep heat” OR dencorub OR dermacreme OR dubam OR eftab OR exocaine OR germolene OR “gone balm” OR gordogesic OR linsal OR salonpas OR intralgin OR mentholatum OR monophytol OR nasciodine OR phlogont rheuma OR “PR heat spray” OR ralgex OR rheumabad OR rheumax OR salonair OR thermo-rub OR nicoboxil OR finalgon OR ortholan OR nonivamide OR Warme-Pflaster OR picolamine OR salicylate OR algiospray OR reflex OR “propyl nicotinate” OR elacur OR nicodan OR salicylamide OR isosal OR salicylate OR salycilic OR movelat OR radian OR “thurfyl salicylate” OR “triethanolamine salicylate” OR “analgesia crme” OR antiphlogistine OR aspercreme OR Ben-Gay OR bexidermil OR dencorub OR exocaine OR metsal OR miosal OR mobisyl OR myoflex OR pro-gesic OR royflex OR sportscreme OR topicrem).ti,ab,kw.

1 OR 2

exp Administration, topical/

(topical$ OR cutaneous OR dermal OR transcutaneous OR transdermal OR percutaneous OR skin OR massage OR embrocation OR gel OR ointment OR aerosol OR cream OR crme OR lotion OR mousse OR foam OR liniment OR spray OR rub OR balm OR salve OR emulsion OR oil OR patch OR plaster).ti,ab,kw.

4 OR 5

exp Athletic injuries/

(strain OR sprain$ OR “sports injury”).ti,ab,kw.

exp Musculoskeletal diseases/

(arthrit$ OR rhemat$ or osteoarth$ OR tend?nitis OR sciatica OR lumbago OR fibrositis).ti,ab,kw.

OR/7-10

(pain OR painful OR analgesi$).ti,ab,kw.

randomized controlled trial.pt.

controlled clinical trial.pt.

randomized.ab.

placebo.ab.

drug therapy.fs.

randomly.ab.

trial.ab.

groups.ab.

OR/13-20

Humans.sh.

21 AND 22

3 AND 6 AND 11 AND 12 AND 23

Appendix 2. EMBASE search strategy

exp Irritants/

(rubefacient OR “counter-irritant” OR “ammonium salicylate” OR “radian B” OR “benzyl nicotinate” OR kausalpunkt OR pykaryl OR rubriment OR “bornyl salicylate” OR camphor OR “choline salicylate” OR “diethylamine salicylate” OR algesal OR algoderm OR algoflex OR artogota OR “Lloyd’s cream” OR physiogesic OR rheumagel OR “transvasin heat spray” OR “diethyl salicylate” OR “ethyl nicotinate” OR mucotherm OR transvasin “PR heat spray” OR “ethyl salicylate” OR “glycol monosalicylate” OR ralgex OR salonpas OR intralgin OR “glycol salicylate” OR “algipan rub” OR menthol OR “methyl butetisalicylate” OR doloderm OR “methyl gentisate” OR “methyl nicotinate” OR “nella red oil” OR wintergreen OR “sweet birch oil” OR “methyl salicylate” OR aezodent OR argesic OR aspellin OR balmosa OR “bengue’s balsam” OR “chymol emollient balm” OR “ deep heat” OR dencorub OR dermacreme OR dubam OR eftab OR exocaine OR germolene OR “gone balm” OR gordogesic OR linsal OR salonpas OR intralgin OR mentholatum OR monophytol OR nasciodine OR phlogont rheuma OR “PR heat spray” OR ralgex OR rheumabad OR rheumax OR salonair OR thermo-rub OR nicoboxil OR finalgon OR ortholan OR nonivamide OR Warme-Pflaster OR picolamine OR salicylate OR algiospray OR reflex OR “propyl nicotinate” OR elacur OR nicodan OR salicylamide OR isosal OR salicylate OR salycilic OR movelat OR radian OR “thurfyl salicylate” OR “triethanolamine salicylate” OR “analgesia crme” OR antiphlogistine OR aspercreme OR Ben-Gay OR bexidermil OR dencorub OR exocaine OR metsal OR miosal OR mobisyl OR myoflex OR pro-gesic OR royflex OR sportscreme OR topicrem).ti,ab,kw.

1 OR 2

exp Administration, topical/

(topical$ OR cutaneous OR dermal OR transcutaneous OR transdermal OR percutaneous OR skin OR massage OR embrocation OR gel OR ointment OR aerosol OR cream OR crme OR lotion OR mousse OR foam OR liniment OR spray OR rub OR balm OR salve OR emulsion OR oil OR patch OR plaster).ti,ab,kw.

4 OR 5

exp Athletic injuries/

(strain OR sprain$ OR “sports injury”).ti.ab.kw.

exp Musculoskeletal diseases/

(arthrit$ OR rhemat$ or osteoarth$ OR tend?nitis OR sciatica OR lumbago OR fibrositis).ti,ab,kw.

OR/7-10

(pain OR painful OR analgesi$).ti,ab,kw.

clinical trials.sh

controlled clinical trials.sh

randomized controlled trial.sh

double-blind procedure.sh

(clin$ adj25 trial$).ab

((doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj25 (blind$ or mask$)).ab

placebo$.ab

random$.ab

OR/13-20

3 AND 6 AND 11 AND 12 AND 21

Appendix 3. CENTRAL search strategy

exp MESH descriptor Irritants

(rubefacient OR “counter-irritant” OR “ammonium salicylate” OR “radian B” OR “benzyl nicotinate” OR kausalpunkt OR pykaryl OR rubriment OR “bornyl salicylate” OR camphor OR “choline salicylate” OR “diethylamine salicylate” OR algesal OR algoderm OR algoflex OR artogota OR “Lloyd’s cream” OR physiogesic OR rheumagel OR “transvasin heat spray” OR “diethyl salicylate” OR “ethyl nicotinate” OR mucotherm OR transvasin “PR heat spray” OR “ethyl salicylate” OR “glycol monosalicylate” OR ralgex OR salonpas OR intralgin OR “glycol salicylate” OR “algipan rub” OR menthol OR “methyl butetisalicylate” OR doloderm OR “methyl gentisate” OR “methyl nicotinate” OR “nella red oil” OR wintergreen OR “sweet birch oil” OR “methyl salicylate” OR aezodent OR argesic OR aspellin OR balmosa OR “bengue’s balsam” OR “chymol emollient balm” OR “ deep heat” OR dencorub OR dermacreme OR dubam OR eftab OR exocaine OR germolene OR “gone balm” OR gordogesic OR linsal OR salonpas OR intralgin OR mentholatum OR monophytol OR nasciodine OR phlogont rheuma OR “PR heat spray” OR ralgex OR rheumabad OR rheumax OR salonair OR thermo-rub OR nicoboxil OR finalgon OR ortholan OR nonivamide OR Warme-Pflaster OR picolamine OR salicylate OR algiospray OR reflex OR “propyl nicotinate” OR elacur OR nicodan OR salicylamide OR isosal OR salicylate OR salycilic OR movelat OR radian OR “thurfyl salicylate” OR “triethanolamine salicylate” OR “analgesia crme” OR antiphlogistine OR aspercreme OR Ben-Gay OR bexidermil OR dencorub OR exocaine OR metsal OR miosal OR mobisyl OR myoflex OR pro-gesic OR royflex OR sportscreme OR topicrem):ti,ab,kw.

1 OR 2

exp MESH descriptor Administration, topical

(topical$ OR cutaneous OR dermal OR transcutaneous OR transdermal OR percutaneous OR skin OR massage OR embrocation OR gel OR ointment OR aerosol OR cream OR crme OR lotion OR mousse OR foam OR liniment OR spray OR rub OR balm OR salve OR emulsion OR oil OR patch OR plaster:ti,ab,kw.

4 OR 5

exp MESH descriptor Athletic injuries

(strain OR sprain$ OR “sports injury”):ti,ab,kw.

exp MESH descriptor Musculoskeletal diseases

(arthrit$ OR rhemat$ or osteoarth$ OR tend?nitis OR sciatica OR lumbago OR fibrositis):ti,ab,kw.

OR/7-10

(pain OR painful OR analgesi$):ti,ab,kw.

Clinical trials:pt.

Controlled Clinical Trial:pt.

Randomized Controlled Trial:pt.

MESH descriptor Double-Blind Method

(clin$ adj25 trial$):ti,ab,kw.

((doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj25 (blind$ or mask$)):ti,ab,kw.

placebo$:ti,ab,kw.

random$:ti,ab,kw.

OR/13-20

3 AND 6 AND 11 AND 12 AND 21

CHARACTERISTICS OF STUDIES

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | RCT DB crossover groups Duration 7 days in each phase |

| Participants | Chronic osteoarthritis of the knee (mean 17 years duration, not secondary to other arthritis or acute trauma, confirmed by X-ray) All patients had at least moderate pain N = 26 (one excluded from analysis due to unrelated medical problem) M = 24, F = 1 Mean age 62 years (range 35-72) |

| Interventions | Triethanolamine salicylate (10%) cream (Myoflex), n = 25 Placebo cream, n = 25 3.5 g × 4 daily to affected knee |

| Outcomes | Preferred drug or placebo or neither based on: Pain 4 point scale Pain 11 point scale Patient assessed pain relief 5 point scale Physician assessed pain relief 5 point scale Physician assessed tenderness 4 point scale Patient preference Continuous measures of swelling, stiffness, and activity Withdrawals Adverse events |

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1 DB2 W1 Oxford Pain Validity Scale: 10 Ineligible for inclusion if salicylates within two days before test period Eligible if on other drug treatment, if taking NSAIDs included only if stable on stated dose for preceding month No change in dose of existing drugs or new analgesics started during the study period No intra-articular steroids within last 6 weeks No other treatment (heat, exercise, massage) during study period |

| Methods | RCT DB parallel groups Duration 10 days |

| Participants | Musculoskeletal pain (e.g. tendon, muscle, or ligament injury) Patients had moderate or mild pain N = 20 M = 8, F = 12 Age range 19-86 years |

| Interventions | Diethylamine salicylate (10%), myrtecaine (1%) cream (Algesal Suractive), n = 10 Placebo cream, n = 10 × 3 daily at the site of pain |

| Outcomes | Rest pain 4 point scale Functional limitation 5 point scale Presence of: Spontaneous pain Swelling Heat Composite score based on above (20 points) Improvement in: Rest pain 4 point scale Composite score |

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1 DB2 W0 Oxford Pain Validity Scale: 10 Myrtecaine (Nopoxamine) is a local anaesthetic agent |

| Methods | RCT DB parallel groups Duration 15 days Assessment on days 2, 3, 4, 8, 15, 29 |

| Participants | Acute ankle sprain presenting within 48 h Injury severity rated moderate or severe N = 80 M = 63, F = 17 Mean age 27 years (range 18-50) |

| Interventions | Salicylic acid (2%), adrenal extract (1%), mucopolysaccharide polysulphate (.2%) ointment (Mobilat), n = 40 Placebo ointment, n = 40 10-15 cm × 2 daily |

| Outcomes | Pressure distribution on walking Swelling Ankle joint movement Rest pain 100 mm VAS Movement pain 100 mm VAS Adverse events |

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R2 DB2 W1 Oxford Pain Validity Scale: 12 Suprarenal extract results in 0.02% corticosteroids |

| Methods | RCT DB parallel groups Duration 11 days Assessment at on days 2, 4, 9, 11 |

| Participants | Acute ankle or knee sprain within 24 h Patients had moderate or slight pain N = 156 M = 98, F = 58 Mean age 32 years (range 18-65) |

| Interventions | Salicylic acid (2%), mucopolysaccharide polysulphate (.2%) cream (Movelat), n = 78 Placebo cream, n = 78 10 cm × 2 daily |

| Outcomes | Movement pain 100 mm VAS Rest pain 100 mm VAS Swelling Physician global assessment 4 point scale Withdrawals Adverse events |

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1 DB2 W0 Oxford Pain Validity Scale: 10 No concomitant treatment allowed except max 1 g paracetamol x3 daily |

| Methods | RCT DB active control crossover groups Duration 7 days in each phase 4 day washout between phases |

| Participants | Chronic musculoskeletal disorders (extra-articular, articular, and vertebral musculoskeletal illness, some sprains) N = 50 M = 25, F = 25 Average age 49 years |

| Interventions | Diethylamine salicylate (10%), sodium heparin (50 IU/g), menthol (0.2%) gel (Dolo-Menthoneurin), n = 25 Etofenamate (5%), n = 25 |

| Outcomes | Spontaneous pain 4 point scale Tenderness 4 point scale Swelling 4 point scale Movement restriction 4 point scale After first phase: Patient global assessment 4 point scale Physician global assessment 4 point scale After second phase: Patient global assessment 3 point scale Physician global assessment 3 point scale Withdrawals Adverse events |

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1 DB1 W1 Oxford Pain Validity Scale: 7 Etofenamate is an NSAID Adverse events reported for both phases combined |

| Methods | RCT DB parallel groups Duration 14 days Assessment on days 3, 14 |

| Participants | Acute mechanical low back pain N = 40 |

| Interventions | Methylsalicylate (2.6%), ethylsalicylate (1.8%), glycol salicylate (.9%), salicylic acid (.9%), camphor (0.4%), menthol (5.5%), capsicum oleoresin (1.5%) ointment (Rado-Salil), n = 20 Placebo ointment, n = 20 Frequency of application not stated |

| Outcomes | Pain 100 mm VAS Duration of confinement to bed Muscular reflex contracture 5 point scale Spine mobility: Schober’s index Finger-floor distance Lumbar extension Patient global assessment 5 point scale Physician global assessment 5 point scale Number of rescue paracetamol (250 mg) tablets Amount of ointment used Adverse events |

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1 DB2 W0 Oxford Pain Validity Scale: 9 No analgesics, anti-inflammatories, or physical treatments allowed other than rescue medication (max 45 × 250 mg paracetamol) |

| Methods | RCT DB double dummy active control parallel groups Duration 7 days Daily assessment |

| Participants | Chronic musculoskeletal pain (articular, e.g. osteoarthritis, and non-articular, e.g. bursitis) for at least weeks (mean 3 years’ duration, range weeks to 25 years) Baseline pain at least mild to moderate N = 40 M = 10, F = 30 Mean age 53 years (range 20-81) |

| Interventions | Triethanolamine salicylate (10%) cream (Aspercreme) + placebo tablets, n = 20 Aspirin (325 mg) tablets + placebo cream, n = 20 Cream applied to affected area and two tablets taken × 4 daily (mealtimes and bedtime) |

| Outcomes | Pain relief 4 point scale Speed of pain relief Pain severity Patient global assessment of pain relief 4 point scale Physician global assessment of pain relief 4 point scale Combined physician and patient global assessment 4 point scale Withdrawals Adverse events |

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1 DB2 W1 Oxford Pain Validity Scale: 9 One week washout of aspirin before trial All other anti-inflammatories allowed during trial Excluded if pre-existing high dose aspirin therapy |

| Methods | RCT DB active control parallel group Duration 12 days Assessment on days 4, 8, 12 |

| Participants | Slight articular and extra-articular sports injuries in last 24 h N = 137 Average age 23 years (range 13-59) |

| Interventions | Benzydamine salicylate (6%) spray (Benzasal), n = 35 Fepradinol (6%) spray (Dalgen), n = 102 One spray × 4 daily |

| Outcomes | Pain on passive movement 5 point scale Pain on active movement 5 point scale Inflammation 5 point scale Functional limitation 5 point scale Time to cure Physician global assessment 5 point scale Adverse events |

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1 DB1 W0 Oxford Pain Validity Scale: 7 Baseline scores for inflammation differed between the two groups Fepradinol is an NSAID |

| Methods | RCT DB parallel groups Duration 7 days Assessment on days 3, 7 |

| Participants | Sprained ankle Baseline pain slight to severe N = 42 M = 20, F = 22 Age range 15 to 60+ years |

| Interventions | Salicylic acid (2%), adrenal extract (1%), mucopolysaccharide polysulphate (0.2%) gel (Movelat), n = 20 Placebo gel, n = 22 |

| Outcomes | Relief of pain Time to return to normal activity Adverse events Composite score based on above plus ankle ROM, swelling Withdrawals |

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1 DB1 W0 Oxford Pain Validity Scale: 11 |

| Methods | RCT DB parallel groups Duration 15 days Assessment on days 10, 15, 20 |

| Participants | Temporomandibular disorders N = 52 M = 5, F = 47 |

| Interventions | Methylsalicylate, copper and zinc pyrocarboxylate, lysine-aspartic acid, herbal extracts cream (Theraflex-TMJ), n = 26 Placebo cream, n = 26 1/4 to 1/2 teaspoon cream onto affected area × 2 daily (morning, bedtime) |

| Outcomes | Spontaneous pain 10 cm VAS Adverse events |

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R2 DB1 W0 Oxford Pain Validity Scale: 7 |

| Methods | RCT DB parallel groups Duration 9 days Assessment on days 3, 7, 9 |

| Participants | Sports injuries Baseline pain mild to severe N = 100 M = 49, F = 32 Average age 30 years (range 14-58) |

| Interventions | Escin 1%, diethylamine salicylate 5% (Reparil-Gel), n = 50 Placebo gel, n = 50 Gel applied at least × 4 daily to affected area |

| Outcomes | Spontaneous pain 4 point scale Loaded pain 4 point scale Movement pain 4 point scale Pain on pressure 4 point scale Tightness 4 point scale Temperature 4 point scale Haematoma 4 point scale Swelling 4 point scale Ratio of range of movement to unaffected limb Ratio of size to unaffected limb Patient global assessment 5 point scale Physician global assessment 5 point scale Improvement in spontaneous pain 3 point scale Improvement in movement pain 3 point scale Remission in spontaneous pain 3 point scale Remission in movement pain 3 point scale Withdrawals Adverse events |

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1 DB2 W1 Oxford Pain Validity Score: 8 19 patients had no data and were not included |

| Methods | RCT DB parallel groups Duration 14 days Assessment days 7, 14 |

| Participants | Non-articular rheumatic back pain N = 113 Average age 56 years |

| Interventions | Glycol salicylate 10% gel (Phardol-Mono), n = 54 Placebo gel, n = 59 5 cm × 3 or × 4 on affected area |

| Outcomes | Drop-out pain-free at day 14 Drop-out pain-free at day 7 2 point reduction on 10 cm VAS at day 14 Withdrawals Adverse events |

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1 DB2 W0 Oxford Pain Validity Score: 12 16 patients excluded due to high rheumatoid factor levels |

| Methods | RCT DB parallel groups Duration 4 weeks Assessment weeks 2, 4 |

| Participants | Osteoarthritis of the hip or knee N = 116 M = 52, F = 64 Mean age 61 years (range 19-86) |

| Interventions | Copper (0.4%) salicylate (4%) gel in vehicle (methanol 2%, camphor 1%, eucalyptus oil 1%), n = 58 Placebo vehicle gel, n = 58 1.5 g × 2 daily applied to inner forearm |

| Outcomes | Rest pain 100 mm VAS Movement pain 100 mm VAS Patient rated efficacy 4 point scale Investigator rated 4 point scale Use of rescue medication Withdrawals Adverse events |

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R2 DB2 W1 Oxford Pain Validity Score: 11 Gel applied remote to site of injury 500 mg paracetamol rescue medication provided Excluded if: NSAIDs in last 7 days Corticosteroids in last 28 days Alterations in arthritis treatment in last 28 days |

| Methods | RCT DB pseudo-active control (assumed to be placebo in this review), parallel groups Duration 7 days Daily assessment One day washout if NSAIDs or other analgesia taken in last 24 h |

| Participants | Acute low back pain in last 72 h Moderate to severe pain on movement N = 161 M = 87, F = 74 Mean age 41 years |

| Interventions | Glycol salicylate (10%), methylnicotinate (1%), capsicum oleoresin (0.1%), histamine hydrochloride (0.1%) (Cremor Capsici Compositus FNA), n = 78 Comfrey (10%), poison ivy (5%), marsh Labrador tea (5%) gel (Spiroflor SRL), n = 83 3 g x3 daily applied to affected area |

| Outcomes | 80% reduction in pain 100 mm VAS 100% reduction in pain 100 mm VAS Nights of disturbed sleep Absence from work Use of rescue analgesia Patient global assessment 6 point scale Physician global assessment 6 point scale Withdrawals Adverse events |

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R2 DB1 W1 Oxford Pain Validity Score: 12 Spiroflor SRL, while officially classified as ‘homeopathic’ in some countries, would be better considered as a herbal remedy because the active ingredients are not diluted to homeopathic levels 500 mg paracetamol rescue medication (max 8 × 500 mg tablets daily) Treatments were not identical in smell, colour, or consistency Protocol compliance was poor (mainly due to under/over dosing) Concentration of capsaicin is only 0.008% |

| Methods | RCT DB pseudo-active control (assumed to be placebo in this review), parallel groups Duration 14 days Assessment at days 3, 6, 9, 14 |

| Participants | Musculoskeletal (knee, spinal or shoulder) disease N = 100 M = 48, F = 52 Average age 51 years |

| Interventions | Ethylene glycol monosalicylate ester (10%), nonivamide (0.2%) in ointment base of sodium heparin (50 IU/g), methylsalicylate (0.1%) and essential oils (Enelbin-Rheuma), n = 50 Salicylic acid (2%) in above ointment base n = 50 8-10 cm of ointment on affected site × 3 or × 4 daily |

| Outcomes | Restriction of movement 4 point scale Swelling 4 point scale Muscle tension 4 point scale Spontaneous pain 4 point scale Pain on pressure 4 point scale Movement pain 4 point scale Physician global assessment 4 point scale based on above scores Curative efficacy 4 point scale Withdrawals Adverse events |

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R2 DB2 W1 Oxford Pain Validity Score: 10 |

| Methods | RCT DB parallel groups Duration 15 days |

| Participants | Musculoskeletal disease (e.g. osteoarthritis) and traumatic injury (e.g. sprains) Baseline pain none to intense N = 56 M = 20, F = 36 Mean age 54 years |

| Interventions | Diethylamine salicylate (10%), myrtecaine (1%) cream (Algesal Suractive), n = 32 Placebo cream, n = 24 Application × 3 daily |

| Outcomes | Improvement in global assessment 4 point scale (global assessment based on 18 point scale ofbasic pain, paroxysmal pain, swelling, functional limitation) Improvement in rest pain 4 point scale Improvement in paroxysmal pain 4 point scale Improvement in swelling 4 point scale Improvement in functional limitation 4 point scale |

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R2 DB1 W0 Oxford Pain Validity Scale: 9 Myrtecaine (Nopoxamine) is a local anaesthetic agent Patients on anti-inflammatories or analgesics excluded |

DB - double blind; F - female; M - male; N - total number in study; n - number in treatment arm; R - randomised; RCT - randomised controlled trial; W - withdrawals

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Crielaard 1986 | Not RCT |

| Dettoni 1982 | Cannot extrapolate data |

| He 2006 | Not rubefacient, not blinded |

| Heindl 1977 | Not RCT |

| Howell 1955 | Not randomised |

| Jolley 1972 | Oral condition |

| Kantor 1990 | Too short duration |

| Kleinschmidt 1975 | Quasi-randomised |

| Pasila 1980 | No usable data |

| Shamszad 1986 | Study I is a republished version of Golden 1978 but no data could be extracted for either Study I or Study II |

| von Batky 1971 | Not RCT |

| Weisinger 1970 | Oral condition, not RCT |

DATA AND ANALYSES

Comparison 1.

Rubefacient versus placebo

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Clinical success (e.g. 50% reduction in pain) | 10 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Acute conditions | 4 | 324 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.93 [1.51, 2.46] |

| 1.2 Chronic conditions | 6 | 455 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.58 [1.22, 2.04] |

| 2 Adverse events | 11 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 Any adverse event | 11 | 984 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.56 [1.19, 2.04] |

| 2.2 Local adverse events | 10 | 869 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.15 [1.12, 4.12] |

| 3 Withdrawals | 7 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 Lack of efficacy | 5 | 501 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.36 [0.15, 0.87] |

| 3.2 Adverse events | 7 | 737 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.19 [1.52, 11.56] |

Comparison 2.

Rubefacient versus active control

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Clinical success (e.g. 50% reduction in pain) | 3 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.1 Acute | 1 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.2 Chronic | 2 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2 Adverse events | 3 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2.1 Any adverse events | 3 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.2 Local adverse events | 3 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3 Withdrawals | 3 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3.1 Lack of efficacy | 2 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.2 Adverse events | 3 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

Analysis 1.1. Comparison 1 Rubefacient versus placebo, Outcome 1 Clinical success (e.g. 50% reduction in pain)

Review: Topical rubefacients for acute and chronic pain in adults

Comparison: 1 Rubefacient versus placebo

Outcome: 1 Clinical success (e.g. 50% reduction in pain)

|

Analysis 1.2. Comparison 1 Rubefacient versus placebo, Outcome 2 Adverse events

Review: Topical rubefacients for acute and chronic pain in adults

Comparison: 1 Rubefacient versus placebo

Outcome: 2 Adverse events

|

|

Analysis 1.3. Comparison 1 Rubefacient versus placebo, Outcome 3 Withdrawals

Review: Topical rubefacients for acute and chronic pain in adults

Comparison: 1 Rubefacient versus placebo

Outcome: 3 Withdrawals

|

|

Analysis 2.1. Comparison 2 Rubefacient versus active control, Outcome 1 Clinical success (e.g. 50% reduction in pain)

Review: Topical rubefacients for acute and chronic pain in adults

Comparison: 2 Rubefacient versus active control

Outcome: 1 Clinical success (e.g. 50% reduction in pain)

|

Analysis 2.2. Comparison 2 Rubefacient versus active control, Outcome 2 Adverse events

Review: Topical rubefacients for acute and chronic pain in adults

Comparison: 2 Rubefacient versus active control

Outcome: 2 Adverse events

|

Analysis 2.3. Comparison 2 Rubefacient versus active control, Outcome 3 Withdrawals

Review: Topical rubefacients for acute and chronic pain in adults

Comparison: 2 Rubefacient versus active control

Outcome: 3 Withdrawals

|

HISTORY

Protocol first published: Issue 4, 2008

Review first published: Issue 3, 2009

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 24 September 2010 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

WHAT’S NEW

Last assessed as up-to-date: 14 September 2011.

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 15 September 2011 | Review declared as stable | The authors of this review scanned the literature in August 2011 and are confident that there will be no change to conclusions and therefore a need to update the search until at least 2015 |

Footnotes

DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST RAM, HJM, SD have received research support from charities, government and industry sources at various times. RAM and HJM have consulted for various pharmaceutical companies and have received lecture fees from pharmaceutical companies related to analgesics and other healthcare interventions. Support for this review came from Oxford Pain Research, the NHS Cochrane Collaboration Programme Grant Scheme, and NIHR Biomedical Research Centre Programme.

References to studies included in this review