Abstract

Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 (TIMP1) regulates intracellular signaling networks for inhibition of apoptosis. Tetraspanin (CD63), a cell surface binding partner for TIMP-1, was previously shown to regulate integrin-mediated survival pathways in the human breast epithelial cell line MCF10A. In the current study, we show that TIMP-1 expression induces phenotypic changes in cell morphology, cell adhesion, cytoskeletal remodeling, and motility, indicative of an epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT). This is evidenced by loss of the epithelial cell adhesion molecule E-cadherin with an increase in the mesenchymal markers vimentin, N-cadherin, and fibronectin. Signaling through TIMP-1, but not TIMP-2, induces the expression of TWIST1, an important EMT transcription factor known to suppress E-cadherin transcription, in a CD63-dependent manner. RNAi-mediated knockdown of TWIST1 rescued E-cadherin expression in TIMP-1 overexpressing cells, demonstrating a functional significance of TWIST1 in TIMP-1 mediated EMT. Furthermore, analysis of TIMP-1 structural mutants reveals that TIMP-1 interactions with CD63 that activate cell survival signaling and EMT do not require the MMP-inhibitory domain of TIMP-1. Taken together, these data demonstrate that TIMP-1 binding to CD63 activates intracellular signal transduction pathways, resulting in EMT-like changes in breast epithelial cells, independent of its MMP-inhibitory function.

Keywords: TIMP, apoptosis, epithelial-mesenchymal transition, TWIST1

INTRODUCTION

The tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMP1-4) regulate the activities of the matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) critical for the precise turnover of the extracellular matrix (ECM) during morphogenesis and tissue remodeling in normal physiological conditions (1). Accordingly, deregulation of these enzymatic activities lead to the development or progression of many human diseases including cancers. Increased expression and/or activity of MMPs are thought to play a particular role for tumor cell invasion. Likewise, in vitro and animal studies have established a function of TIMPs in the inhibition of tumor cell invasion and metastasis. However, clinical studies revealed that TIMPs are often upregulated in many cancers. Especially, TIMP-1 overexpression correlates with a poor prognosis in certain malignancies including metastatic breast cancer (2–4). Although a prognostic value of TIMP-1 is now well established, it is unclear whether increased TIMP-1 expression contributes to tumor progression. Since many transcription factors shown to upregulate TIMP-1 expression can also induce expression of MMPs, it was postulated that increased TIMP-1 expression may be a reflection of stromal responses to the increased MMPs expression in cancer cells. However, increasing evidence suggests the existence of signaling pathways that lead to TIMP-1 upregulation without MMP induction (5). Importantly, we and others have demonstrated a role for TIMP-1 in the regulation of cell growth and apoptosis inhibition in many different cell types. TIMP-1 regulation of cell survival appears to occur through two co-existing pathways: an MMP-dependent pathway (6–8) or MMP-independent mechanism (9–15). Our discovery of CD63, a member of the tetraspanin family of proteins, as a TIMP-1 interacting protein provided molecular insight as to the action of TIMP-1 as a signaling molecule distinct from their MMP inhibitory activity (16). We demonstrated that TIMP-1 binds to CD63 in a complex with integrin β1, a main tetraspanin interacting integrin, on the cell surface and activates cell survival signaling pathways in a CD63-dependent manner (16). In agreement with our results, Egea et al. recently highlighted that TIMP-1 downregulates β-catenin signaling via a decrease of let-7f miRNA in a MMP-independent manner and the binding of CD63 to TIMP-1 on the surface is necessary for the TIMP-1-mediated signaling in human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) (17). Although these studies may have provided an explanation, at least in part, for a potential tumor-promoting activity of TIMP-1, the molecular actions of TIMP-1 aside from its MMP inhibitory function are still largely unknown. In this study, we made a novel finding that TIMP-1 induces phenotypic conversion of epithelial cells to a mesenchymal phenotype termed an epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT). EMT is a morphological conversion process initiated by master transcription factors such as Slug, Snail, the EF1 protein SIP1, and TWIST1 (18, 19) that drastically alter gene expression profiles including the repression of E-cadherin transcription and the induction of N-cadherin, vimentin, and fibronectin. Through an EMT process, epithelial cells undergo drastic remodeling of the cytoskeleton, lose their polarity and cell-cell contact, and acquire a migratory phenotype. Importantly, increasing evidence supports an hypothesis that many of these molecular and cellular changes associated with normal developmental EMT are recapitulated during the progression of human carcinomas, possibly as a transient, dynamic process utilizing the EMT transcription factors [reviewed in (18, 20, 21)]. Here, we report that TIMP-1 interaction with CD63 activates intracellular signal transduction pathways leading to upregulation of the EMT master transcription factor TWIST1, resulting in a decrease in the epithelial markers and an increase in the mesenchymal markers, along with phenotypic changes such as the transition to a fibroblast-like cell shape and increased cell scattering and cell motility. Importantly, a TIMP-1 mutant devoid of its MMP inhibitory domain was sufficient to interact with CD63 and to induce phenotypic changes of EMT in human breast epithelial MCF10A cells. These results unveiled an unexpected, novel function of TIMP-1 as an extracellular signal inducer that mediates an EMT-like phenotypic conversion in human breast epithelial cells by a mechanism independent of its MMP inhibitory activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and antibodies

Anti-TIMP-1 monoclonal antibody (mAb) was purchased from NeoMarkers, Inc. (Fremont, CA). Anti-CD63, anti-integrin α6 antibody, anti-laminin a5 mAb, and the FAK100 staining kit were purchased from Chemicon (Billerica, MA). Anti-β-actin, anti-vimentin, anti-mouse IgG peroxidase conjugate, and anti-Rabbit IgG peroxidase conjugate antibodies were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Anti-E-cadherin and anti-β-catenin mAbs were purchased from BD transduction laboratories (San Jose, CA). Anti-cow cytokeratin wide spectrum screening polyclonal antibody (pAb) was purchased from Dako (Carpinteria, CA). FITC-conjugated and Texas Red conjugated rabbit or mouse IgG antibodies and normal donkey serum were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories (West Grove, PA). Anti-TWIST1 pAb was generously donated by Carlotta Glackin (Beckman Institute of the City of Hope, Duarte, CA) and anti-TWIST1 mAb was purchased from Abcam. Growth factor-reduced matrigel was purchased from BD Biosciences.

Overexpression of TIMP-1 and Its Mutants in MCF10A Cells

Generation of TIMP-1 overexpressing (TIMP-1) MCF10A clones was previously described (12, 13). For the mutant study, full-length TIMP-1 (amino acids 1–184) (T1) or the partial N-terminal without MMP inhibitory domain and C-terminal domain (amino acids 66–184) of TIMP-1 (T1D) were amplified by PCR using a vector carrying hTIMP-1 cDNA from Open Biosystems (Huntsville, AL), and the various restriction enzyme sites were introduced respectively according to the target vector. The signal peptide was included in the constructs for protein to be secreted. The final PCR products containing the signal sequences were fused to p3XFLAG-CMV-14 expression vector at a BamH I site. The correct orientation and in-frame fusion were confirmed by DNA sequencing. The partial N-terminal and C-terminal TIMP-1-FLAG (T1D), pcDNA3.1-TIMP-1, and pcDNA3.1 control vectors were transfected into MCF10A cells using Lipofectamine 2000 from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Establishment of FLAG-tagged wild type TIMP-1 transfected MCF10A clone (WT TIMP-1/FLAG #9, referred as T1#9 in this paper) were described previously (13).

Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) Analysis of Mesenchymal and Epithelial Markers

Total RNA was isolated using the Qiagen RNA Easy Miniprep Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA using the SuperScript™ First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR. The thermal cycle profile consisted of an initial denaturation at 94°C for 5 minutes, followed by 25 cycles consisting of a 30 second denaturation at 94°C, a 1 minute annealing of primers at 55°C, and a 1 minute extension at 74°C, followed by a final 7 minute extension at 74°C. The PCR products were then electrophoresed through 1% agarose gels. The primers used are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Establishing Stable CD63-Knockdown Cell Lines

Plasmids carrying shRNA targeted to CD63 were constructed following Ambion’s web-based protocol. TIMP-1 MCF10A cells were transfected with either target 2 or control vector using Lipofectamine 2000 from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA) as described previously (16).

Real-Time PCR Analysis

Real-time PCR reactions were carried out using Brilliant® SYBR® Green QPCR Master Mix (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA.), and thermal cycling was carried out on the Mx4000 multiplex quantitative PCR system (Stratagene) using optimized PCR conditions in triplicate. The median cycle threshold value was used for analysis, and all cycle threshold values were normalized to the expression of the housekeeping gene GAPDH. The mRNA level in Neo cells were arbitrarily given as 1, and the relative mRNA levels in TIMP-1, TIMP-1 shCont-P, and TIMP-1 shCD63-2 MCF10A cells compared to the levels in the Neo control cells were determined as recommended by the manufacturer (Stratagene).

Immunoblot Analysis

Cell lysates were obtained by lysing the cell monolayer with SDS lysis buffer [2% SDS, 125 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), and 20% glycerol] and immunoblot analysis was performed according to the protocol described previously (16).

Immunofluorescent cell staining

For immunofluorescence analysis, cells were plated on chamber slides at 50% confluency overnight and immunostained with antibodies according to the previously published protocol (22).

MCF10A morphogenesis assay in three dimensional (3D) cultures

Three-dimensional culture of MCF10A cells and immunostaining was conducted according to the published protocol (16). Confocal immunofluorescence microscopic analysis was performed using a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscopy system equipped with a C-Apochromat (NA = 1.2) 63x korr objective lenses (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Inc.) or (NA = 1.3) 40x lens. Images for figures were colored and resized with Adobe Photoshop 5.5 software.

Knockdown of TWIST1 Using siRNA

TIMP-1 MCF10A cells were plated onto chamber slides and the next day transiently transfected with control or TWIST1 siRNA oligos (Invitrogen) for 72 hours according to the Lipofectamine protocol (Invitrogen). The cells were fixed and immunostaining of TWIST1 or E-cadherin and DAPI (nuclear) staining was conducted according to the protocol above. The TWIST1 siRNA and control oligos are listed in Table 2 of the supplementary section.

Low and High Confluent MCF10A Cell Experiment

MCF-10A cells were grown at the indicated cell densities [10% to 30% confluence (low confluency) or 80% to 90% confluence (high confluency) according to the following protocol in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37°C (23).

Production of Recombinant TIMP-1/TIMP-2 and treatment of MCF10A cells

Human recombinant TIMP-1 and TIMP-2 was expressed in HeLa cells using a vaccinia expression system and purified to homogeneity as described previously (12). MCF10A cells were treated with rTIMP-1 or rTIMP-2 for 4 days in DMEM/F-12 medium supplemented with 2% horse serum and cell lysate was collected with 2% SDS lysis buffer and RNA was collected using the Quiagen RNA Kit. Fresh media with rTIMP-1 was supplemented every day of the experiment. Western blot of E-cadherin and TWIST1 was performed with a β-actin loading control. RT-PCR was done to detect the expression of E-cadherin in these samples over time.

Cell Migration Assay

All cells were grown in complete medium and pretreated with mitomycin C (25 μg/ml) for 30 min. Transwell units with polycarbonate filters (Corning Costar, Cambridge, MA) were used for all cell migration assays according to the published protocol (15). Cells on the filters were fixed and stained using the Diff-Quik Stain Set (American Scientific Products, McGaw Park, IL), following the direction of the manufacturer.

RESULTS

TIMP-1 overexpression results in EMT-like changes in cell morphology and gene expression

During the course of our study of TIMP-1’s activity in human breast epithelial cell signaling, we observed a remarkable change in the morphology of MCF10A cells upon TIMP-1 overexpression. While control (Neo) MCF10A cells display cobble-stone-like, typical epithelial cell morphology, TIMP-1 overexpressing MCF10A cells show spindle shaped, fibroblast-like morphology with loss of cell-cell contacts and increased cell scattering (Fig. 1A, top panel), which may be associated with an epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT)-like conversion. Changes in the cytoskeletal structure in a 3D matrigel culture, as shown by phalloidin staining of F-actin (Fig. 1A, bottom panel), also suggested TIMP-1-mediated phenotypic changes. A semi-quantitative RT-PCR analysis detected changes in gene expression at the mRNA levels, showing a decrease in the epithelial cell-specific markers, E-cadherin, β-catenin, and γ-catenin and an increase in the mesenchymal markers, vimentin, N-cadherin, and fibronectin (Fig. 1B, left panel). Consistently, TIMP-1 overexpression resulted in a loss of E-cadherin and a gain of vimentin protein levels in MCF10A cells as detected by immunoblot analysis (Fig. 1B, right panel). Immunostaining in a 3D matrigel culture also revealed that TIMP-1-mediated a drastic decrease in E-cadherin and a marked induction of vimentin expression, whereas cytokeratin expression was detected in both control and TIMP-1 overexpressing MCF10A cells (Fig. 1C&D). It is thought that the cytoplasmic domain of E-cadherin forms a complex with the catenin protein family, linking E-cadherin to the actin filament network for the maintenance of the architectural integrity of the epithelium and intercellular adhesion (24). Studies show that loss of E-cadherin often coincides with the accumulation of β-catenin in the nucleus for activation of its target genes (25). Next, we examined the effects of TIMP-1 overexpression on the expression level and subcellular localization of the β-catenin protein. As shown in Fig 1D, β-catenin was found throughout the cells in TIMP-1 overexpressing cells with a loss of E-cadherin expression, whereas it was localized to the cytoplasmic membrane in control MCF10A cells, which also show E-cadherin expression. Immunoblot analysis confirmed a decreased expression of β-catenin in TIMP-1 overexpressing cells (data not shown).

Figure 1. TIMP-1 regulates EMT-like phenotypic changes and gene expression.

A, Phase contrast microscopy of control (Neo) and TIMP-1 overexpressing MCF10A (TIMP-1) cells at 20X magnification. Immunostaining of phalloidin (red) and nuclear DAPI (blue) staining in cross sections through the middle of developing acini of Neo and TIMP-1 overexpressing cells cultured in growth factor reduced matrigel for 8–14 days. B, RT-PCR analysis of the mesenchymal markers vimentin, N-cadherin, and fibronectin (fibro) as well as the epithelial markers E-cadherin, α-catenin, β-catenin, and γ-catenin. GAPDH was used as a loading control (left panel). Immunoblot analysis of E-cadherin and vimentin in control (Neo) and TIMP-1 MCF10A cells. β-actin was used as a loading control (right panel). C, Immunostaining of E-cadherin (green) and DAPI (blue) staining in cross sections through the middle of developing acini of Neo and TIMP-1 overexpressing cells (top panel). Immunostaining of cytokeratin (green), vimentin (red), and DAPI (blue) staining in cross sections of the middle of developing acini cultured in growth factor reduced matrigel (bottom panel). D, Immunostaining of E-cadherin or β-catenin (red) and DAPI (blue) staining in Neo and TIMP-1 MCF10A cells plated on chamber slides. Scale bars, 50 μM.

CD63 is essential for TIMP-1 regulation of EMT-like conversion and the EMT master transcription factor TWIST1

EMT, a vital process for morphogenesis during embryonic development, is initiated by master regulators such as Slug, Snail, the EF1 protein SIP1, and TWIST1 (18, 26) that drastically alter gene expression profiles including the repression of E-cadherin transcription and the induction of N-cadherin, vimentin, and fibronectin. Interestingly, many of these molecular and cellular changes associated with normal developmental EMT are often characteristics of invasive and metastatic carcinoma cells (18). Therefore, we examined whether TIMP-1-mediated EMT-like changes were associated with induction of transcription factors known to regulate EMT. We found that TWIST1 mRNA level was significantly induced by TIMP-1 expression (3.3 fold) as determined by real time Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) (Fig. 2A), while the levels of Snail and Slug were unaffected (data not shown). TWIST1 is a basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factor originally discovered as an essential factor for EMT during mesoderm formation in Drosophila (27). Consistent with a notion that TWIST1 regulates epithelial and mesenchymal markers at the transcriptional level, decreased mRNA expression of the epithelial markers, E-cadherin, β-catenin, and γ-catenin and increased mRNA expression of N-cadherin, vimentin, and fibronectin was found in TIMP-1 overexpressing MCF10A cells (Fig. 1B).

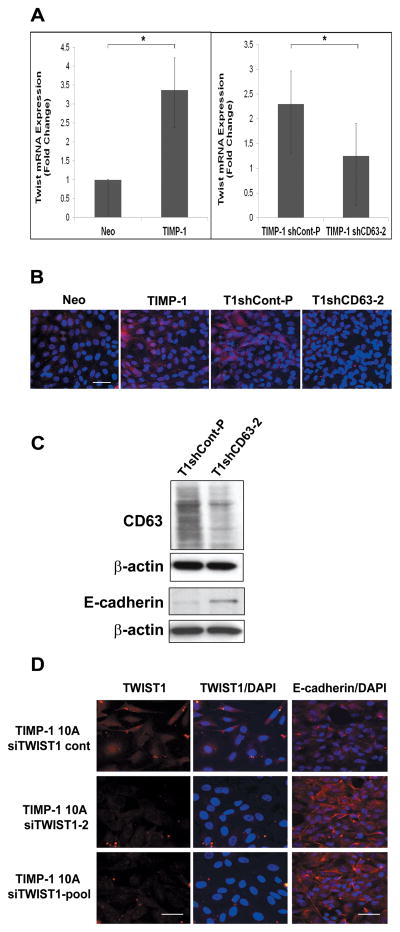

Figure 2. TIMP-1 increases the expression of the EMT transcription factor TWIST1 in a CD63 dependent manner.

A, Q-RT-PCR analysis of TWIST1 mRNA in control (Neo), TIMP-1 MCF10A cells, and TIMP-1 MCF10A cells transfected with shRNA control or CD63 shRNA (TIMP-1 shCont-P, TIMP-1 shCD63–2, respectively). The experiment was done in triplicates and the data is representative of three or more independent experiments. Each bar represents the mean ± S.D. Asterisk (*) denotes a P value < 0.05 using a Paired T-test. B, Immunostaining of TWIST1 (red) and DAPI (blue) in Neo, TIMP-1, TIMP-1shCont-P, and TIMP-1shCD63-2. C, Immunoblot analysis of CD63 and E-cadherin in TIMP-1 MCF10A cells stably transfected with control or CD63 shRNA. β-actin was used as a loading control. D, Immunostaining of TWIST1 (red) or E-cadherin (red) and DAPI (blue) staining in TIMP-1 MCF10A cells transiently transfected with control or TWIST1 siRNA oligos for 72 hours. TIMP-1 10A siTWIST1-2 cells were treated with oligo 2 and TIMP-1 10A siTWIST1-pool cells were treated with a pool of TWIST1 siRNA oligos. Scale bars, 50 μM.

Previously, we demonstrated that TIMP-1 binding to CD63 on the cell surface regulates cell survival signaling pathways involving the tetraspanin/integrin complex. TIMP-1-mediated constitutive activation of CD63/integrin signaling was shown to disrupt MCF10A cell polarization and formation of acini-like structures in 3D matrigel culture (16). Here, we asked whether CD63 is required for TIMP-1 induction of TWIST1 and/or downregulation of E-cadherin, a hallmark of EMT. To this end, we examined TWIST1 expression in MCF10A cells overexpressing TIMP-1 with or without CD63-knockdown using small hairpin RNA (shRNA). CD63-knockdown significantly reduced TWIST1 expression in TIMP-1 overexpressing MCF10A cells as determined by real-time RT-PCR analysis (Fig. 2A) and immunostaining (Fig. 2B). CD63 knockdown also partially reversed the TIMP-1 mediated downregulation of E-cadherin expression (Fig. 2C).

The above results suggest that TIMP-1/CD63 signaling upregulates TWIST1 expression leading to EMT-like conversion in MCF10A cells. To evaluate the functional significance of TWIST1 in TIMP-1-mediated EMT, we downregulated TWIST1 expression in TIMP-1 overexpressing MCF10A cells using an siRNA approach. Whereas E-cadherin expression was barely detected in TIMP-1 overexpressing MCF10A with TWIST1 expression, E-cadherin was readily detected in TIMP-1 overexpressing cells upon TWIST1 knockdown (Fig. 2D). Taken together, these results indicate that TIMP-1/CD63 signaling upregulates TWIST1 expression, resulting in EMT-like conversion in human breast epithelial MCF10A cells.

TIMP-1 induction of EMT is independent of cell confluency

Although increasing evidence has suggested a critical role for the EMT master transcription factors in cancer progression and metastasis, it has been debated whether “oncogene”-mediated EMT-like changes observed in vitro reflects the in vivo tumor biology or it is just a phenomenon only associated with a particular tissue culture condition. Interestingly, Sarrió et al. discovered that MCF10A cells undergo spontaneous morphologic and phenotypic EMT-like changes in response to different cell confluencies (23). EMT was induced at sparse confluency (15–30%), and the EMT expression pattern was lost when the cells were highly confluent. This study led us to examine if TIMP-mediated EMT is dependent on the confluency of the cell culture.

The control MCF10A cells at subconfluence or confluence displayed a cobblestone-like epithelial cell phenotype. In contrast, TIMP-1 overexpressing cells show a spindle-shaped, fibroblast-like morphology regardless of the cell density (Fig. 3A). Interestingly, TIMP-1 overexpressing cells reached confluence at lower cell density compared to the control MCF10A cells. Immunoblot and RT-PCR analyses confirmed that TIMP-1 overexpression downregulates the epithelial cell marker E-cadherin and induces the mesenchymal makers N-cadherin and vimentin regardless of cell density (Fig 3B, left panel and 3C). In addition, immunostaining of the mesenchymal markers N-cadherin and vimentin shows that in the Neo control cells N-cadherin and vimentin expression is much lower than in the TIMP-1 overexpressing cells, while these cells had a higher expression of cytokeratin (Fig. 3D, red staining). With TIMP-1 overexpression, we see expression of N-cadherin and vimentin at both low and high confluency (Fig. 3D, green staining). Lastly, with CD63 knockdown the TIMP-1 overexpressing cells are more rounded in shape (Fig. 3A) and E-cadherin expression was increased to some degree, although not completely, in both conditions (Fig. 3B, right panel).

Figure 3. TIMP-1 mediates EMT-like conversion independent of cell confluency.

Neo, TIMP-1 MCF10A cells, TIMP-1 shCont-P, and TIMP-1 shCD63-2 cells were plated at about 30% (low) and about 90% (high) confluency. A, Phase contrast microscope pictures are shown for each cell line. B, Immunoblot for E-cadherin and vimentin with β-actin as a loading control. C, RT-PCR for E-cadherin, N-cadherin with GAPDH as a loading control. D, Immunostaining of N-cadherin (green, top row); vimentin (green) and cytokeratin (red, second row) along with DAPI nuclear staining (blue).

Exogenous treatment of MCF10A cells with rTIMP-1, but not rTIMP-2, induces EMT-like changes in gene expression

To further establish the role for TIMP-1 in EMT, we asked whether exogenously added TIMP-1 proteins can upregulate the EMT master transcription factor TWIST1 and/or downregulate E-cadherin expression. To this end, MCF10A cells were treated daily with 500 ng/ml of rTIMP-1 for 4 days and subjected to daily collection of RNAs and cell lysates. After 3 days of rTIMP-1 treatment there was a significant increase in TWIST1 expression followed by a reduction in E-cadherin expression (Fig. 4A). Interestingly, rTIMP-2, a closely related MMP inhibitor, had little effect on the expression of E-cadherin, suggesting that the regulation of cell signaling leading to the EMT-like conversion in MCF10A cells overexpressing TIMP-1 was specific to TIMP-1 (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4. Treatment with exogenous rTIMP-1 induces loss of E-cadherin in MCF10A cells.

MCF10A cells were treated daily with 500 ng/ml of rTIMP-1 (A) or rTIMP-2 (B) for 4 days. RT-PCR analysis of E-cadherin and immunoblot analysis for E-cadherin and TWIST1 was conducted. GAPDH is the loading control for the RT-PCR analysis and β-actin is the loading control for the immunoblot analysis.

TIMP-1-mediated EMT does not require the N-terminal MMP inhibitory domain

TIMP-1 has a two-domain structure with its N- and C-terminal regions each containing six conserved cysteine residues forming three disulfide bonds. The N-terminal domain contains a region of higher homology among TIMPs (TIMP-1 to -4) and is sufficient for inhibition of matrix metalloproteinases. This domain contains residues that interact with the Zn2+-binding pocket of active MMPs. The C-terminal domain of TIMPs is thought to be critical for protein-protein interactions [reviewed in (4)]. We previously showed that the C-terminal domain of TIMP-1 interacts with CD63, suggesting that TIMP-1’s signaling activity is independent of its MMP-inhibitory domain. To establish the structural/functional basis for TIMP-1 regulation of EMT via its interactions with CD63, we generated MCF10A cell clones expressing a full-length TIMP-1 (T1) or a deletion mutant of TIMP-1 lacking the MMP inhibitory domain (encoding aa 66–184, referred to as T1D) as depicted in Fig. 5A, left panel. When we examined the cell morphology, T1D expressing cells (T1D #66 and T1D #69) displayed elongated and fibroblast-like cell shapes similarly to that of the full-length TIMP-1 expressing cells (T1 #9) (Fig. 5A, right panel). T1D expression upregulated mRNA expression of the EMT transcription factor TWIST1 as well as the mesenchymal markers vimentin, and N-cadherin, and this was accompanied with a decrease in the epithelial marker E-cadherin as seen in wild-type TIMP-1 expressing cells (Fig. 5B). Consistently, T1D expression resulted in a decrease in the expression of the epithelial cell markers, E cadherin and β-catenin, and an increase in the mesenchymal marker vimentin as effectively as wild-type TIMP-1 expression as shown by immunoblot analysis (Fig. 5C). Immunostaining of control MCF10A cells showed expression of E-cadherin and β–catenin on the cell-cell junctions (Fig. 5D). Upon TIMP-1 or TID expression, E-cadherin and β-catenin were barely detectable on the cell surface. Instead, there was an induction of the mesenchymal markers N-cadherin and vimentin (Fig. 5D) compared to the control MCF10A cells. These results clearly demonstrate the TIMP-1-mediated EMT-like transition does not involve its MMP-inhibitory domain.

Figure 5. The MMP-inhibitory domain is not necessary for TIMP-1 to induce an EMT-like rearrangement of the cytoskeleton and regulate EMT gene expression.

A, A diagram of the number of amino acids in wild type full length TIMP-1 (F-TIMP-1), MMP inhibitory domain alone (T1N), and TIMP-1 mutants (T1D) devoid of the MMP-inhibitory domain (left panel). Phase contrast microscope pictures of MCF10A control, T1 #9, T1 D #66 and #69 (right panel). B, RT-PCR of E-cadherin, TWIST1, vimentin, and N-cadherin with GAPDH as a loading control in MCF10A control, T1 #9, T1D #66 and 69 cells. C, Immunoblot of E-cadherin, β-catenin, and vimentin, with β-actin as the loading control. D, Immunostaining of E-cadherin, β-catenin, or N-cadherin (green) and DAPI nuclear staining (blue) in control MCF10A cells, T1 #9, and T1D #66 and #69. In the bottom row the cells were immunostained with Vimentin (green), and cytokeratin (red), and DAPI staining (blue). Scale bars, 50 μM.

TIMP-1 and T1D induces MCF10A cell migration

The ability of the cells to acquire a migratory phenotype is a functional hallmark of EMT. Thus, we assessed the effects of TIMP-1 expression on cell motility using a transwell chamber assay. TIMP-1 overexpression resulted in ~5 fold increased cell migration (Fig. 6A). Upon CD63 knockdown, TIMP-1’s ability to induce cell motility was significantly reduced to less than 2 fold, demonstrating a critical role of CD63 for the TIMP-1 mediated cell motility (Fig. 6B). Importantly, the cell motility rates were comparable between MCF10A cells overexpressing wild-type TIMP-1 (T1#9) and the T1D mutants (T1D #66 and #69) (Fig. 6C). These data clearly indicate that TIMP-1 regulates EMT gene expression, cellular phenotypes and cell motility in a CD63-dependent manner, independent of TIMP-1’s MMP-inhibitory domain.

Figure 6. TIMP-1 increases MCF10A cell migration in a CD63-dependent manner and is independent of TIMP-1’s MMP-inhibitory domain.

Transwell migration assay with Neo, TIMP-1 (A) and TIMP-1 shCont-P and TIMP-1 shCD63-2 cells (B). C, Transwell migration assay with Control MCF10A, T1 #9, T1D #66 and T1D #69 cells. For all of these experiments, cells were pretreated with mitomycin C (25 μg/ml) for 30 min. The total number of cells that migrated to the lower side of the filter were counted using microscopy at 20X. The experiment was done in triplicates and the data is representative of two or more independent experiments. Each bar represents the mean ± S.D. Asterisk (*) denotes a P value < 0.05 using a Paired T-test and is considered significant and (***) denotes a P value < 0.001 using a Paired T-test and is considered extremely significant.

DISCUSSION

The present study unveiled a novel function of TIMP-1 in mediating EMT-derived phenotypic conversion in human breast epithelial cells. Although EMT has not been conclusively confirmed in human cancers by pathologists, increasing evidence supports a notion that subprograms of developmental EMTs are involved during the progression of human carcinoma, possibly as a transient, dynamic process occurring in a small subpopulation of tumor cells at any given time [reviewed in (18, 20, 21)]. Accordingly, loss or downregulation of E-cadherin expression is frequently found in carcinoma cells, and is often inversely correlated with malignancy (28). While promoter hypermethylation and inactivating mutations account for loss of E-cadherin expression/function in some tumors, epigenetic mechanisms also play a critical role in downregulation of E-cadherin expression during carcinoma progression (29, 30). Interestingly, the PI3K/Akt axis has emerged as a key signaling pathway for induction of EMT-mediating transcription factors that downregulate E-cadherin (26, 31, 32). Importantly, this study found that TIMP-1 signaling induces TWIST1 expression, a basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factor known to suppress E-cadherin gene transcription and upregulate mesenchymal markers, providing molecular insight into TIMP-1’s role in EMT. The prominent phenotype of TWIST1 knockout mice was a failure of the cranial neural folds to fuse and differentiation of the cranial neural crest cells (33, 34). Whereas, a critical role for TWIST1 has been proposed in the metastatic process, linking the developmental EMT process with tumor metastasis (35). A study showed that 70% of invasive lobular breast carcinomas have increased expression of TWIST1 and decreased E-cadherin, whereas most normal breast tissue samples expressed TWIST1 at a very low level (35). TWIST1 has also been shown to play a role in the regulation of apoptosis. TWIST1 haploinsufficiency in Saethre-Chotzen syndrome (SCS), a human autosomal dominant disorder characterized by premature fusion of cranial sutures, alters osteoblast apoptosis (36). Consistently, downregulation of TWIST1 by DNazymes, a group of catalytic nucleic acids designed to cleave target mRNA molecules, resulted in an increase of cellular apoptosis (37). In cancer cells, increased TWIST1 expression was shown to inhibit oncogene- and p53-dependent cell death (38) and result in resistance to certain chemotherapeutic drugs, angiogenesis, and chromosomal instability (39, 40).

A study showed that TWIST1 transcriptionally upregulates Akt2 by binding to the E-box elements on the promoter of Akt2 in breast carcinoma cells and that silencing Akt2 reverses TWIST1-mediated EMT, cell migration, invasion and paclitaxel resistance (41), suggesting a positive feed-back signaling loop between the Akt and TWIST1 for the regulation of EMT and cell survival. Importantly, we have previously showed that TIMP-1 activates CD63/integrin survival signaling pathways involving the PI3K/Akt pathways for the regulation of apoptosis. In fact, our recent report also showed TIMP-1 induces an EMT-like process independent of the MMP-inhibitory domain in MDCK cells (15), although we could not investigate the involvement of CD63 in the TIMP-1 mediated EMT process in this model because of the limitation of the unidentified canine CD63. However, the MDCK study demonstrated similar results to the TIMP-1 interaction with CD63 and subsequent activation of signal transduction pathways we have found previously in breast epithelial cells. Thus, it appears that TIMP-1 binding to the CD63/integrin signaling complex activates both cell survival and EMT pathways and subsequently undergoes signal amplification by cross-talk between these pathways.

A functional hallmark of EMT is acquisition of migratory characteristics, a critical component of tumor cell invasion during the metastatic process which requires degradation and remodeling of extracellular matrix (ECM) components. The involvement of MMPs including MMP-2, MMP-3, MMP-9, MMP-28 and MMP-14 (MT1-MMP) was suggested in EMT-derived phenotypic conversion in cancer cells (42–44). In addition to MMPs’ ability to remodel ECM, MMP-modulation of EMT signaling has been demonstrated in cancer cells. Exposure of mammary epithelial cells to stromelysin (MMP-3) resulted in EMT involving increased expression of an alternative splicing variant of Rac1, resulting in an increase in cellular reactive oxygen species leading to upregulation of the EMT transcription factor Snail (45). Epilysin (MMP-28) was shown to induce EMT through proteolytic processing of latent TGF-β complexes into the active form, resulting in TGF-β-mediated EMT signaling in lung carcinoma cells (46). These MMP-mediated EMT processes can be prevented by chemical inhibitor of MMPs such as BB3103 or GM6001 (46, 47). Considering a well-established role for TIMP-1 in inhibition of MMPs and therefore inhibition of tumor cell invasion, our finding of a novel function of TIMP-1 in mediating EMT is completely unexpected. Importantly, we demonstrated that TIMP-1 mediated EMT is independent of its MMP-inhibitory domain, establishing TIMP-1 as a critical signaling molecule for the regulation of breast epithelial cell morphology and migratory phenotype. Similarly to our study, an association of TIMP-1 with the EMT process was suggested in Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells (48). In these cells, MAPK activation which regulates gene expression including MMP-13 and TIMP-1 was necessary to induce the first stage of tubulogenesis, the partial epithelial to mesenchymal transition (p-EMT), whereas matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) were necessary for the second redifferentiation stage. If MMP-mediated proteolytic events were responsible for EMT, TIMP-1 knockdown was expected to enhance or not to affect the EMT processes. TIMP-1 knockdown however, was shown to result in partial inhibition of EMT in MDCK cells (48), indirectly suggesting a TIMP-1 role in EMT without its inhibition of MMPs, consistent with the present study.

In summary, we report a novel activity of TIMP-1 as a signaling molecule for induction of EMT-derived phenotype in human breast epithelial cells. We propose that TIMP-1 has duel, rather paradoxical, functions during cancer progression: When the cell surface binding partner for TIMP-1 such as CD63 is readily available, TIMP-1 interaction with its cell surface signaling partner activates intracellular signaling pathways leading to EMT-derived phenotype including cell migratory characteristics, exerting a potential oncogenic activity. In a microenvironment where TIMP-1 predominantly interacts with MMPs, TIMP-1 is likely to inhibit tumor cell metastasis via its inhibition of MMPs. Thus, TIMP-1’s function as an endogenous inhibitor of MMP or as a “cytokine-like” signaling molecule may be a critical determinant for tumor cell behavior, and the molecular actions of TIMP-1 may be determined by the localization (soluble vs. pericellular ) and the levels of its cell surface partner and MMPs.

Supplementary Material

IMPLICATIONS.

TIMP-1’s function as an endogenous inhibitor of MMP or as a “cytokine-like” signaling molecule may be a critical determinant for tumor cell behavior.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by NIH/National Cancer Institute Grant CA089113 (to H-R. C. K.) and the DOD Breast Cancer Research Program (BC061743 to RCD). Microscopy and Imaging Resources Laboratory is supported in part by center grants P30 ES06639 from the National Institutes of Environmental Health Sciences and P30CA22453 from the National Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Kleiner DE, Jr, Stetler-Stevenson WG. Structural biochemistry and activation of matrix metalloproteases. Current opinion in cell biology. 1993;5:891–7. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(93)90040-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wurtz SO, Schrohl AS, Mouridsen H, Brunner N. TIMP-1 as a tumor marker in breast cancer--an update. Acta oncologica. 2008;47:580–90. doi: 10.1080/02841860802022976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moller Sorensen N, Vejgaard Sorensen I, Ornbjerg Wurtz S, Schrohl AS, Dowell B, Davis G, et al. Biology and potential clinical implications of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 in colorectal cancer treatment. Scandinavian journal of gastroenterology. 2008;43:774–86. doi: 10.1080/00365520701878163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chirco R, Liu XW, Jung KK, Kim HR. Novel functions of TIMPs in cell signaling. Cancer metastasis reviews. 2006;25:99–113. doi: 10.1007/s10555-006-7893-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Logan SK, Garabedian MJ, Campbell CE, Werb Z. Synergistic transcriptional activation of the tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 promoter via functional interaction of AP-1 and Ets-1 transcription factors. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1996;271:774–82. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.2.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boudreau N, Sympson CJ, Werb Z, Bissell MJ. Suppression of ICE and apoptosis in mammary epithelial cells by extracellular matrix. Science. 1995;267:891–3. doi: 10.1126/science.7531366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alexander CM, Howard EW, Bissell MJ, Werb Z. Rescue of mammary epithelial cell apoptosis and entactin degradation by a tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 transgene. The Journal of cell biology. 1996;135:1669–77. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.6.1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murphy FR, Issa R, Zhou X, Ratnarajah S, Nagase H, Arthur MJ, et al. Inhibition of apoptosis of activated hepatic stellate cells by tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 is mediated via effects on matrix metalloproteinase inhibition: implications for reversibility of liver fibrosis. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277:11069–76. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111490200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Docherty AJ, Lyons A, Smith BJ, Wright EM, Stephens PE, Harris TJ, et al. Sequence of human tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases and its identity to erythroid-potentiating activity. Nature. 1985;318:66–9. doi: 10.1038/318066a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hayakawa T, Yamashita K, Tanzawa K, Uchijima E, Iwata K. Growth-promoting activity of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 (TIMP-1) for a wide range of cells. A possible new growth factor in serum. FEBS letters. 1992;298:29–32. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guedez L, Stetler-Stevenson WG, Wolff L, Wang J, Fukushima P, Mansoor A, et al. In vitro suppression of programmed cell death of B cells by tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1998;102:2002–10. doi: 10.1172/JCI2881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li G, Fridman R, Kim HR. Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 inhibits apoptosis of human breast epithelial cells. Cancer research. 1999;59:6267–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu XW, Bernardo MM, Fridman R, Kim HR. Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 protects human breast epithelial cells against intrinsic apoptotic cell death via the focal adhesion kinase/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and MAPK signaling pathway. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278:40364–72. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302999200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu XW, Taube ME, Jung KK, Dong Z, Lee YJ, Roshy S, et al. Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 protects human breast epithelial cells from extrinsic cell death: a potential oncogenic activity of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1. Cancer research. 2005;65:898–906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jung YS, Liu XW, Chirco R, Warner RB, Fridman R, Kim HR. TIMP-1 induces an EMT-like phenotypic conversion in MDCK cells independent of its MMP-inhibitory domain. PloS one. 2012;7:e38773. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jung KK, Liu XW, Chirco R, Fridman R, Kim HR. Identification of CD63 as a tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 interacting cell surface protein. The EMBO journal. 2006;25:3934–42. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Egea V, Zahler S, Rieth N, Neth P, Popp T, Kehe K, et al. Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 (TIMP-1) regulates mesenchymal stem cells through let-7f microRNA and Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:E309–16. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115083109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kang Y, Massague J. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions: TWIST1 in development and metastasis. Cell. 2004;118:277–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin TA, Goyal A, Watkins G, Jiang WG. Expression of the transcription factors snail, slug, and TWIST1 and their clinical significance in human breast cancer. Annals of surgical oncology. 2005;12:488–96. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2005.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Birchmeier C, Birchmeier W, Brand-Saberi B. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in cancer progression. Acta anatomica. 1996;156:217–26. doi: 10.1159/000147848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vincent-Salomon A, Thiery JP. Host microenvironment in breast cancer development: epithelial-mesenchymal transition in breast cancer development. Breast cancer research : BCR. 2003;5:101–6. doi: 10.1186/bcr578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taube ME, Liu XW, Fridman R, Kim HR. TIMP-1 regulation of cell cycle in human breast epithelial cells via stabilization of p27(KIP1) protein. Oncogene. 2006;25:3041–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sarrio D, Rodriguez-Pinilla SM, Hardisson D, Cano A, Moreno-Bueno G, Palacios J. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in breast cancer relates to the basal-like phenotype. Cancer research. 2008;68:989–97. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takeichi M. Cadherin cell adhesion receptors as a morphogenetic regulator. Science. 1991;251:1451–5. doi: 10.1126/science.2006419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lim SC, Lee MS. Significance of E-cadherin/beta-catenin complex and cyclin D1 in breast cancer. Oncology reports. 2002;9:915–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boyer B, Valles AM, Edme N. Induction and regulation of epithelial-mesenchymal transitions. Biochemical pharmacology. 2000;60:1091–9. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(00)00427-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thisse B, el Messal M, Perrin-Schmitt F. The TWIST1 gene: isolation of a Drosophila zygotic gene necessary for the establishment of dorsoventral pattern. Nucleic acids research. 1987;15:3439–53. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.8.3439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berx G, Becker KF, Hofler H, van Roy F. Mutations of the human E-cadherin (CDH1) gene. Human mutation. 1998;12:226–37. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1998)12:4<226::AID-HUMU2>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nass SJ, Herman JG, Gabrielson E, Iversen PW, Parl FF, Davidson NE, et al. Aberrant methylation of the estrogen receptor and E-cadherin 5′ CpG islands increases with malignant progression in human breast cancer. Cancer research. 2000;60:4346–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Graff JR, Gabrielson E, Fujii H, Baylin SB, Herman JG. Methylation patterns of the E-cadherin 5′ CpG island are unstable and reflect the dynamic, heterogeneous loss of E-cadherin expression during metastatic progression. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2000;275:2727–32. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.4.2727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Larue L, Bellacosa A. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in development and cancer: role of phosphatidylinositol 3′ kinase/AKT pathways. Oncogene. 2005;24:7443–54. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grille SJ, Bellacosa A, Upson J, Klein-Szanto AJ, van Roy F, Lee-Kwon W, et al. The protein kinase Akt induces epithelial mesenchymal transition and promotes enhanced motility and invasiveness of squamous cell carcinoma lines. Cancer research. 2003;63:2172–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen ZF, Behringer RR. TWIST1 is required in head mesenchyme for cranial neural tube morphogenesis. Genes & development. 1995;9:686–99. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.6.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Soo K, O’Rourke MP, Khoo PL, Steiner KA, Wong N, Behringer RR, et al. TWIST1 function is required for the morphogenesis of the cephalic neural tube and the differentiation of the cranial neural crest cells in the mouse embryo. Developmental biology. 2002;247:251–70. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang J, Mani SA, Donaher JL, Ramaswamy S, Itzykson RA, Come C, et al. TWIST1, a master regulator of morphogenesis, plays an essential role in tumor metastasis. Cell. 2004;117:927–39. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yousfi M, Lasmoles F, El Ghouzzi V, Marie PJ. TWIST1 haploinsufficiency in Saethre-Chotzen syndrome induces calvarial osteoblast apoptosis due to increased TNFalpha expression and caspase-2 activation. Human molecular genetics. 2002;11:359–69. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.4.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hjiantoniou E, Iseki S, Uney JB, Phylactou LA. DNazyme-mediated cleavage of TWIST1 transcripts and increase in cellular apoptosis. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2003;300:178–81. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02804-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maestro R, Dei Tos AP, Hamamori Y, Krasnokutsky S, Sartorelli V, Kedes L, et al. TWIST1 is a potential oncogene that inhibits apoptosis. Genes & development. 1999;13:2207–17. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.17.2207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang X, Ling MT, Guan XY, Tsao SW, Cheung HW, Lee DT, et al. Identification of a novel function of TWIST1, a bHLH protein, in the development of acquired taxol resistance in human cancer cells. Oncogene. 2004;23:474–82. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mironchik Y, Winnard PT, Jr, Vesuna F, Kato Y, Wildes F, Pathak AP, et al. TWIST1 overexpression induces in vivo angiogenesis and correlates with chromosomal instability in breast cancer. Cancer research. 2005;65:10801–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cheng GZ, Chan J, Wang Q, Zhang W, Sun CD, Wang LH. TWIST1 transcriptionally up-regulates AKT2 in breast cancer cells leading to increased migration, invasion, and resistance to paclitaxel. Cancer research. 2007;67:1979–87. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pulyaeva H, Bueno J, Polette M, Birembaut P, Sato H, Seiki M, et al. MT1-MMP correlates with MMP-2 activation potential seen after epithelial to mesenchymal transition in human breast carcinoma cells. Clinical & experimental metastasis. 1997;15:111–20. doi: 10.1023/a:1018444609098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gilles C, Polette M, Birembaut P, Brunner N, Thompson EW. Expression of c-ets-1 mRNA is associated with an invasive, EMT-derived phenotype in breast carcinoma cell lines. Clinical & experimental metastasis. 1997;15:519–26. doi: 10.1023/a:1018427027270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kuphal S, Wallner S, Schimanski CC, Bataille F, Hofer P, Strand S, et al. Expression of Hugl-1 is strongly reduced in malignant melanoma. Oncogene. 2006;25:103–10. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Radisky DC, Levy DD, Littlepage LE, Liu H, Nelson CM, Fata JE, et al. Rac1b and reactive oxygen species mediate MMP-3-induced EMT and genomic instability. Nature. 2005;436:123–7. doi: 10.1038/nature03688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Illman SA, Lehti K, Keski-Oja J, Lohi J. Epilysin (MMP-28) induces TGF-beta mediated epithelial to mesenchymal transition in lung carcinoma cells. Journal of cell science. 2006;119:3856–65. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brown NL, Yarram SJ, Mansell JP, Sandy JR. Matrix metalloproteinases have a role in palatogenesis. Journal of dental research. 2002;81:826–30. doi: 10.1177/154405910208101206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hellman NE, Spector J, Robinson J, Zuo X, Saunier S, Antignac C, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase 13 (MMP13) and tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase 1 (TIMP1), regulated by the MAPK pathway, are both necessary for Madin-Darby canine kidney tubulogenesis. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2008;283:4272–82. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708027200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.