Abstract

The differential diagnosis between hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and regenerative liver nodules and other primary liver tumors may be very difficult, particularly when performed on liver biopsies. Difficulties in histological typing may be often minimized by immunohistochemistry. Among the numerous markers proposed, CK18, Hep Par1 and glypican 3 (GPC3) are considered the most useful in HCC diagnosis. Here we report a case of HCC in a 72-year-old male with HBV-related chronic liver disease, characterized by a marked morphological and immunohistochemical intratumoral variability. In this case, tumor grading ranged from areas extremely well differentiated, similar to regenerative nodule, to undifferentiated regions, with large atypical multinucleated cells. While almost all sub nodules were immunostained by Hep Par 1, immunoreactivity for glypican 3 and for Ck18 was patchy, with negative tumor region adjacent to the highly immunoreactive areas. Our case stresses the relevance of sampling variability in the diagnosis of HCC, and indicates that caution should be taken in grading an HCC and in the interpretation of immunohistochemical stains when only small core biopsies from liver nodules are available.

Keywords: Liver, Hepatocellular carcinoma, Sampling variability, Hep Par 1, GPC3, Differentiation

INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the 5th most frequent malignancy worldwide[1]. The prognosis is generally poor; therefore, the early diagnosis is critical for successful treatment and clinical behaviour[2]. For evaluation of HCC, computerized tomography-guided needle biopsy represents the most accurate diagnostic procedure. HCC has distinct morphologic features and, in the majority of cases, it can be identified by routine H-E stained sections. However, distinguishing a well-differentiated HCC from a regenerative nodule or from a dysplastic nodule may be very difficult, particularly in small needle aspiration or core biopsies[3]. Furthermore, some of the unusual morphologic variants, including clear-cell, pleomorphic, and sarcomatoid variants, may be mistaken for metastases. Similarly, metastases to the liver from various hepatoid variants of extra-hepatic neoplasms and other primary hepatic tumors, such as cholangiocarcinoma (CC), may be mistaken for HCC[4]. The differential diagnosis of these lesions is often difficult, especially because of the scant material obtained by needle biopsy[5]. The current literature shows that difficulties in histological typing of liver tumors, particularly in the differential diagnosis between HCC and CC and metastases can be minimized by using immunohistochemistry[4,6]. Among the numerous diagnostic immunohistochemical markers studied, alpha-fetoprotein (AFP)[7], CK7[8], CK20[9], CK19[10], hepatocyte paraffin 1 (Hep Par 1)[11,12] and glypican 3 (GPC3)[3,5,13] have been found to be valuable in the diagnosis of HCC. The sensitivity and specificity of the monoclonal antibody Hep Par 1 for HCC are considered very high; as a consequence, the usefulness of this marker in the differential diagnosis of hepatic tumors is widely accepted[14-19], although it stains normal hepatocytes as well. Moreover, expression profiling of primary hepatic tumors has demonstrated that GPC3, a membrane-anchored heparan sulfate proteoglycan, is markedly expressed in HCC, particularly in well differentiated cases[20]. In spite of the availability of such armamentarium, daily experience shows that diagnostic mistakes can occur more frequently than generally expected. Indeed, some cases of HCC have been reported that do not show immunoreactivity for Hep Par 1, nor for GPC3[5,17]. The reason for this heterogeneity in immunoreactivity of HCCs could be related to multiple factors: different etiology, variable degree of differentiation, size of the bioptic core and sampling variability. Here we report a case of HCC characterized by marked morphological and phenotypical intratumoral variability, which underlines a previously unreported major role for sampling variability in the interpretation of needle biopsies from HCC.

CASE REPORT

A 72-year-old man with a clinical history of HBV-related chronic liver disease (Child-Pugh A5) was admitted the Hospital San Giovanni di Dio of Cagliari. Ultrasonography (US) revealed a liver nodule in the VIIth hepatic segment, measuring 25 mm in diameter, which was later confirmed by CT scan. Surgical excision was performed. Gross examination of the surgical specimen showed a light nodule, white-yellow on cut surface, characterized by a multinodular pattern. The surrounding parenchyma showed an active chronic hepatitis with porto-central bridging septa. Histological examination of the nodule revealed an HCC organized in multiple sub-nodules, some of which were capsulated. The morphology of each sub-nodule varied greatly from well to scantly differentiated HCC (Figure 1A-C). According to the sub-nodular organization of the neoplastic cells and to the degree of differentiation of the lesion, 17 different sub-nodules were detected. Immunohistochemical analyses showed a marked heterogeneity among the different sub-nodules (Table 1). While almost all sub-nodules showed immunoreactivity for Hep Par 1 (Figure 2A), the immunoreactivity for CK18 was patchy, with negative tumor regions adjacent to intensely immunoreactive areas (Figure 2B). We found immunoreactivity for GPC3 in 6 out of the 17 subclones; immunoreactivity for GPC3 was constantly absent in well differentiated areas and positive in several, but not all, poorly differentiated ones (Figure 2C). Immunoreactivity for CK7 was observed in scattered neoplastic cells within some sub-nodules. p53 was unevenly distributed among different sub-nodules; in the 5 positive sub-nodules, immunoreactivity for p53 ranged from 10% up to 40% of tumor cells. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) was evenly distributed through the entire tumor, without any significant difference among the sub-nodules. No immunoreactivity for AFP, nor for CK20 was observed.

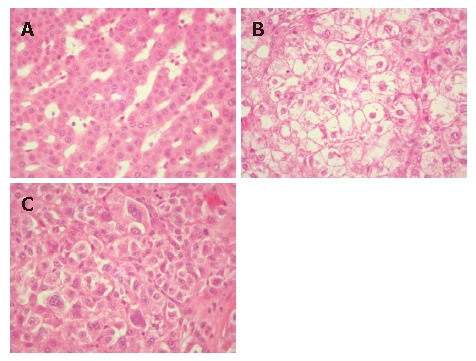

Figure 1.

The morphology of each sub-nodule varied greatly including well differentiated (A), moderately differentiated (B) and poorly differentiated HCC (C).

Table 1.

Immunohistochemical patterns of the different sub-nodules

| Sub-nodule | Hep-Par 1 | CK18 | GPC3 | CK7 | p53 | PCNA |

| L | + | + | - | - | - | + |

| 1 | + | + | - | +/- | - | + |

| 2 | + | + | - | +/- | - | + |

| 3 | + | + | - | - | + | |

| 4 | + | + | - | +/- | - | + |

| 5 | + | + | - | +/- | - | + |

| 6 | + | + | + | - | - | + |

| 7 | + | +/- | - | - | - | - |

| 8 | + | - | - | - | - | - |

| 9 | + | - | + | - | - | + |

| 10 | + | - | - | - | - | + |

| 11 | +/- | - | - | - | - | + |

| 12 | + | - | - | - | - | + |

| 13 | + | - | + | - | + | + |

| 14 | ± | - | - | - | + | + |

| 15 | + | ± | + | - | + | + |

| 16 | + | ± | + | - | + | + |

| 17 | + | - | + | - | + | + |

L: Normal liver; ±: Scattered reactivity; +/−: Focal reactivity.

Figure 2.

Sub-nodules localization and their different immunoreactivity for Hep Par1 (A), CK18 (B) and GPC3 (C).

DISCUSSION

Currently, the diagnosis of HCC is based on a multi-disciplinary approach, including imaging modalities and serum markers, such as AFP. However, the diagnosis of HCC still rests on the incontrovertible histological evidence obtained by CT scan or echo-guided needle biopsy. The histological appearance of HCC has been described in detail over the years and criteria for diagnosis and nomenclature have been clarified[1].

In the present case, we observed a striking variability in the degree of differentiation of the tumor cells among the 17 different sub-nodules detected. As a consequence, in the case that, before the surgical resection, a needle biopsy had been performed, we may hypothesize that the interpretation of the bioptic core could have lead to different diagnoses, depending on the different tumor region sampled. Tumor samples from well differentiated areas (Figure 1A) should lead to a differential diagnosis between well differentiated HCC and a regenerative nodule; a bioptic core from the poorly differentiated sub-nodules (Figure 1C) should lead to a differential diagnosis between a polymorphous aggressive variant of HCC and a metastasis from a poorly differentiated carcinoma.

Moreover, even the expression of the immunohisto-chemical markers utilized in this study varied greatly among different tumor regions. This finding underlines the possibility that, in clinical practice, when a very small fragment of the liver tumor is obtained by an ultrasound-guided biopsy, immunoreactivity of the observed tumor cells could not represent the distribution of tumor markers in the whole neoplasm, leading to sampling variability-related diagnostic mistakes. In fact, the majority of sub-nodules were negative for GPC3, a marker which is considered a valuable tool in distinguishing HCC from dysplastic liver nodules[3].

In conclusion, our case highlights the role of sampling variability in the interpretation of a needle biopsy from a liver nodule, not only for defining tumor grading but even in the differential diagnosis between primary and secondary liver tumor.

Footnotes

S- Editor Liu Y L- Editor Kumar M E- Editor Liu Y

References

- 1.Lopez JB. Recent developments in the first detection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Biochem Rev. 2005;26:65–79. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou L, Liu J, Luo F. Serum tumor markers for detection of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:1175–1181. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i8.1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Libbrecht L, Severi T, Cassiman D, Vander Borght S, Pirenne J, Nevens F, Verslype C, van Pelt J, Roskams T. Glypican-3 expression distinguishes small hepatocellular carcinomas from cirrhosis, dysplastic nodules, and focal nodular hyperplasia-like nodules. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:1405–1411. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000213323.97294.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Varma V, Cohen C. Immunohistochemical and molecular markers in the diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Adv Anat Pathol. 2004;11:239–249. doi: 10.1097/01.pap.0000131822.31576.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhu ZW, Friess H, Wang L, Abou-Shady M, Zimmermann A, Lander AD, Korc M, Kleeff J, Büchler MW. Enhanced glypican-3 expression differentiates the majority of hepatocellular carcinomas from benign hepatic disorders. Gut. 2001;48:558–564. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.4.558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ma CK, Zarbo RJ, Frierson HF, Lee MW. Comparative immunohistochemical study of primary and metastatic carcinomas of the liver. Am J Clin Pathol. 1993;99:551–557. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/99.5.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang L, Vuolo M, Suhrland MJ, Schlesinger K. HepPar1, MOC-31, pCEA, mCEA and CD10 for distinguishing hepatocellular carcinoma vs. metastatic adenocarcinoma in liver fine needle aspirates. Acta Cytol. 2006;50:257–262. doi: 10.1159/000325951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Durnez A, Verslype C, Nevens F, Fevery J, Aerts R, Pirenne J, Lesaffre E, Libbrecht L, Desmet V, Roskams T. The clinicopathological and prognostic relevance of cytokeratin 7 and 19 expression in hepatocellular carcinoma. A possible progenitor cell origin. Histopathology. 2006;49:138–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2006.02468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chu P, Wu E, Weiss LM. Cytokeratin 7 and cytokeratin 20 expression in epithelial neoplasms: a survey of 435 cases. Mod Pathol. 2000;13:962–972. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Eyken P, Sciot R, Paterson A, Callea F, Kew MC, Desmet VJ. Cytokeratin expression in hepatocellular carcinoma: an immunohistochemical study. Hum Pathol. 1988;19:562–568. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(88)80205-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zimmerman RL, Burke MA, Young NA, Solomides CC, Bibbo M. Diagnostic value of hepatocyte paraffin 1 antibody to discriminate hepatocellular carcinoma from metastatic carcinoma in fine-needle aspiration biopsies of the liver. Cancer. 2001;93:288–291. doi: 10.1002/cncr.9043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siddiqui MT, Saboorian MH, Gokaslan ST, Ashfaq R. Diagnostic utility of the HepPar1 antibody to differentiate hepatocellular carcinoma from metastatic carcinoma in fine-needle aspiration samples. Cancer. 2002;96:49–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Capurro M, Wanless IR, Sherman M, Deboer G, Shi W, Miyoshi E, Filmus J. Glypican-3: a novel serum and histochemical marker for hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:89–97. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00689-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chu PG, Ishizawa S, Wu E, Weiss LM. Hepatocyte antigen as a marker of hepatocellular carcinoma: an immunohistochemical comparison to carcinoembryonic antigen, CD10, and alpha-fetoprotein. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:978–988. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200208000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saad RS, Luckasevic TM, Noga CM, Johnson DR, Silverman JF, Liu YL. Diagnostic value of HepPar1, pCEA, CD10, and CD34 expression in separating hepatocellular carcinoma from metastatic carcinoma in fine-needle aspiration cytology. Diagn Cytopathol. 2004;30:1–6. doi: 10.1002/dc.10345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamauchi N, Watanabe A, Hishinuma M, Ohashi K, Midorikawa Y, Morishita Y, Niki T, Shibahara J, Mori M, Makuuchi M, et al. The glypican 3 oncofetal protein is a promising diagnostic marker for hepatocellular carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:1591–1598. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sugiki T, Yamamoto M, Aruga A, Takasaki K, Nakano M. Immunohistological evaluation of single small hepatocellular carcinoma with negative staining of monoclonal antibody Hepatocyte Paraffin 1. J Surg Oncol. 2004;88:104–107. doi: 10.1002/jso.20144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maharaj B, Maharaj RJ, Leary WP, Cooppan RM, Naran AD, Pirie D, Pudifin DJ. Sampling variability and its influence on the diagnostic yield of percutaneous needle biopsy of the liver. Lancet. 1986;1:523–525. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)90883-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zardi EM, Uwechie V, Picardi A, Costantino S. Liver focal lesions and hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic patients: from screening to diagnosis. Clin Ter. 2001;152:185–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hytiroglou P, Theise ND. Differential diagnosis of hepatocellular nodular lesions. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1998;15:285–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]