Abstract

Photoreceptor (PR) cells are prone to accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and oxidative stress. An imbalance between the production of ROS and cellular antioxidant defenses contributes to PR degeneration and blindness in many different ocular disease states. Yttrium oxide (Y2O3) nanoparticles (NPs) are excellent free radical scavengers due to their non-stoichiometric crystal defects. Here we utilize a murine light stress model to test the efficacy of Y2O3 NPs (~ 10–14 nm in diameter) in ameliorating retinal oxidative stress-associated degeneration. Our studies demonstrate that intravitreal injections of these NPs at doses ranging from 0.1 μM to 5.0 μM two weeks prior to acute light stress protects PRs from degeneration. This protection is reflected both structurally (i.e. decreased light-associated thinning of the outer nuclear layer) and functionally, i.e. in preservation of scotopic and photopic electroretinogram amplitudes. We also observe preservation of structure and function when NPs are delivered immediately after acute light stress, although the magnitude of the preservation is smaller, and only doses ranging from 1.0 μM to 5.0 μM were effective. We show that the Y2O3 NPs are non-toxic and well-tolerated after intravitreal delivery. Our results suggest that Y2O3 NPs have astonishing antioxidant benefits, and with further exploration, may be an excellent strategy for the treatment of oxidative stress associated with multiple forms of retinal degeneration.

Keywords: Nanoparticle, rescue, oxidative stress, photoreceptors, light-damage, Y2O3

Introduction

Progressive dysfunction and degeneration of photoreceptors (PR) is a leading cause of blindness [1]. PRs experience high light exposure compared to other parts of the body and also have been shown to experience oxidative stress and accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), processes which are implicated in the pathobiology of many retinal diseases including diabetic retinopathy [2] and age-related macular degeneration (for recent review of this literature, see [3]). Generation of ROS activates cellular antioxidant defense systems which promote cell survival [4–6], but overproduction of ROS creates oxidative stress [6]. This can severely damage multiple cellular processes, disrupt cellular physiology, and activate apoptosis. In PRs, the high levels of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) are particularly susceptible to lipid peroxidation [3, 7, 8], and oxidative damage to proteins, RNA, and DNA can also occur [4, 7].

A logical way to defend against these disease processes is antioxidant therapy [9, 10], and antioxidants can protect the retina and retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) [11] from oxidative damage. In patients, dietary supplementation with antioxidants was effective in preventing and slowing down the progression of AMD [12] and delaying retinitis pigmentosa [13]. These observations suggest that delivery of highly efficacious, non-enzymatic anti-oxidants directly to the eye (thus avoiding issues of oral bioavailability which have plagued other approaches) may significantly ameliorate some forms of retinal degeneration.

The transition metal yttrium (Y) has a high affinity for oxygen compared to other elements [14]. Yttrium oxide (Y2O3) is an important dopant for the rare earth metals and is gaining interest for application in photodynamic therapy and biological imaging [15–19]. Importantly, and in contrast to many other metals, the form of yttrium with the highest free energy is the oxide form [14], making it extremely stable. Y2O3 nanoparticles (NP) are an air stable white solid substance and are insoluble in water. A significant degree of nonstoichiometric defects occur on absorption of water and carbon dioxide from air under normal atmospheric conditions [14]. These defects are responsible for the free radical scavenging activity of the Y2O3 [14].

Previously, it has been reported that Y2O3 NPs promote survival of neuronal cells in vitro under glutamate-induced oxidative stress [14]. Endogenous ROS were quenched by Y2O3 NPs within 15 minutes (as measured by ROS-induced formation of the fluorescent compound dichlorofluorescein), indicating that Y2O3-mediated protection is due to fast-acting direct anti-oxidant effects, rather than indirect effects such as initiation of a complex cellular response (which occur on a longer time scale). Other studies have also shown that Y2O3 NPs have protective, antioxidant effects: rat pancreatic islets were protected from oxidative stress-mediated apoptosis by Y2O3 [20]. These antioxidant properties were found comparable to those of other commonly used metal antioxidants such as ceria [14, 21], which has also been shown to be effective at retarding retinal oxidative damage [21]. Here we test the hypothesis that Y2O3 NPs can be used to prevent oxidative retinal damage in a murine light damage model [22, 23]. Light damage models have been widely [22–29] and successfully used to test anti-oxidant therapies, and our results show that Y2O3 NPs confer significant protection against light-induced retinal damage suggesting that this could be an exciting approach to protect the retina.

Materials and methods

NP characterization

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis was carried out as described [30, 31] using one drop of a 1 mM or 5 μM Y2O3 NP (Sigma-Aldrich Inc.) dispersion which was prepared under 10W ultrasonication at room temperature.

Oxygen-radical absorbance capacity (ORAC) assay

This assay was implemented according to methods previously described [32] with some modifications. Fluorescein sodium salt (FL, 0.05–4.8 μM, Sigma-Aldrich Inc.), 2,2′-Azobis(2-methylpropionamidine) dihydrochloride (AAPH, 0.15M, Sigma-Aldrich Inc.), (±)-6-Hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchromane-2-carboxylic acid (Trolox, 5–35 μM, Sigma-Aldrich Inc.) and the Y2O3 NPs (5–35 μM) were all prepared in 1x phosphate buffered saline (PBS) at pH= 7.4. Initially the fluorescence of FL was optimized within the range of 0.05–4.8 μM in 96 well plates (flat bottom, polystyrene). The fluorescence intensity was determined at 520 nm (emission) upon excitation at 485 nm using a microplate reader (FLUOstar optima, BMG labtech Inc.). The assay was carried out by taking 30 μl of FL (0.15 μM) + 60 μl of AAPH and varying concentrations of Y2O3 NPs or trolox. The NPs and AAPH were mixed in a 96 well plate first and warmed at 37°C for 15 min and then FL was added to the mixture in the dark right before the fluorescence measurements were recorded in the microplate reader. Antioxidant capacity was determined by measuring the area under the curve of the time dependent fluorescence intensity of FL from Y2O3 NPs and trolox treated experiments. Trolox (a vitamin E analogue) was taken as a positive control for the assay. The assay was repeated 4 separate times and each time was performed in triplicate. To assess whether soluble metal ions released from the NPs mediate the effect, the ORAC assay was repeated with NP supernatant vs. pellet. 35 μM of NPs was suspended in water in two separate tubes and they were centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 30 min to pellet the particles. The ORAC experiment was carried out in the same way as above with the supernatant vs NP pellet along with the respective controls.

Injections and light exposure protocols

Albino mice (Balb/C) were bred in-house and were maintained in the breeding colony under cyclic light (30 lux, 12L:12D) throughout the study except when specified in the light exposure paradigm. The University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all experiments and animal care, and all animal experiments complied with guidelines set forth by the Association of Research in Vision and Ophthalmology. For light exposure experiments, animals were dark-adapted for 48 hours. After the dark adaptation mice (2/cage) were placed in a transparent polycarbonate cage which had the food in the bottom of the cage and a water bottle placed at the side of the cage to ensure even light penetration. This cage was then placed in a light box for 2 hours with constant bright light at the specified intensity. Upon completion of the light exposure, mice were returned to their normal cages and replaced in their regular housing area under normal cyclic light (30 lux, 12L:12D) for the duration of the study. Light exposure and injections were carried out at the same time of day throughout the study. Trans-scleral intravitreal injections of 2μl NP suspension were performed as described previously [33].

Electroretinography

Full-field electroretinography was performed as described previously [33]. Maximum scotopic and photopic A- and B-wave amplitudes are plotted (n=8–12).

Morphometric analysis

Eyes were enucleated, dissected, and fixed as described previously [34]. H&E stained sections from each eye along the vertical meridian were used to measure outer nuclear layer (ONL) thicknesses and number of ONL nuclei using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health) [34]. Images for morphometry were collected from at least 3 eyes per group, starting from the optic nerve head (ONH) and proceeding towards the periphery at 435 μm intervals.

Statistical analyses

The standard deviation (SD) was used for the statistical analysis of area under the curve measurements from triplicates. One or two way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post-hoc comparison was used for all other statistical analysis. Significance was defined as P<0.05, and data in all other figures are presented as mean ±SEM. Throughout, * P<0.001, ** P<0.01, ***P<0.05.

Results

Nanoparticle characterization

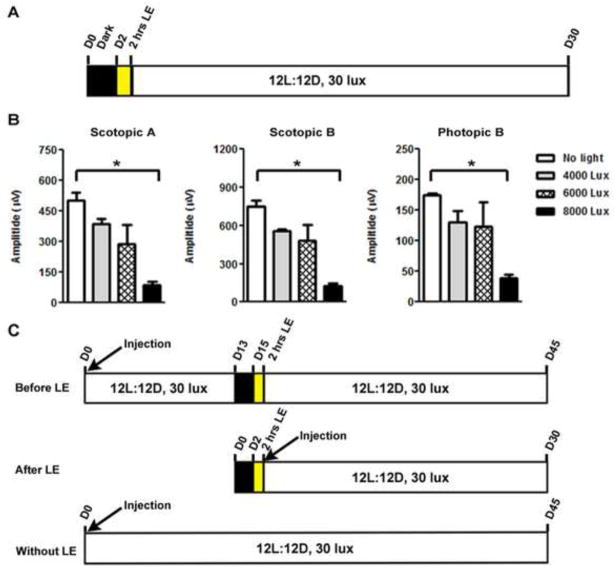

We first undertook a physical characterization of the Y2O3 NP suspension. High resolution TEM of Y2O3 NPs at 1mM demonstrated that the individual NPs were monodisperse and spherical in shape (arrows Fig. 1A, left), although at this high concentration they tended to aggregate. To confirm that the particle shape was retained at our working concentrations, we also conducted TEM on particles at 5 μM (Fig. 1A, right). While the particles were significantly rarer on the grid due to the lower concentration, they exhibited the same shape and size characteristics (inset in Fig. 1A, right, shows larger version of particle with arrowhead). Measurements from the TEM indicated that the particles are ~10–14 nm in diameter. The shape is as expected, and previously it has been demonstrated that spherical Y2O3 NPs possess less cellular toxicity than other shapes [17]. For subsequent studies we tested the efficacy of these NPs at 0.1, 1.0 and 5.0 μM, as similar doses have been tested for other non-enzymatic anti-oxidants [21].

Figure 1. Transmission electron microscopic (TEM) characterizations and oxygen-radical absorbance capacity (ORAC) assay of Y2O3 NPs.

(A) TEM image of monodispersed spherical Y2O3 NPs (1 mM and 5 μM), the arrows are indicating spherical NPs. Inset shows a single Y2O3 NP, scale bar = 100 nm, inset scale bar 25 nm. (B) Plot of fluorescence intensity vs concentration of fluorescein. (C) The antioxidant capacity with varying concentrations of Y2O3 NPs. The antioxidant capacity was calculated from area under the curve of the time dependent fluorescence intensity from Y2O3 NP treatments. (D) The antioxidant capacity with varying concentrations of trolox. The antioxidant capacity was calculated from area under the curve of the time dependent fluorescence intensity from trolox treated assay. (E) The antioxidant capacities of supernatant and pellet from Y2O3 NPs were assessed by ORAC. Results are plotted as mean ± SD (in the trolox studies, the SD was within the size of the graph symbol, n=3).

To assess the direct free radical scavenging activity of the Y2O3 NPs, we used the standard oxygen-radical absorbance capacity (ORAC) assay in which the ability of antioxidants to suppress 2,2′-Azobis(2-methylpropionamidine) dihydrochloride (AAPH)-derived free radicals is measured by assessing the extent to which the antioxidants block radical-mediated quenching of fluorescein fluorescence [32]. To determine the optimum concentration of fluorescein for the assay, the fluorescence intensity was plotted as a function of fluorescein concentration (Fig. 1B), and 0.15 μM fluorescein was selected as an appropriate non-saturating concentration for the later studies. We assessed and plotted fluorescence over time after adding varying concentrations of Y2O3 NPs (5–35 μM) or the positive control anti-oxidant (Trolox, a vitamin E analogue) to a constant concentration of AAPH/fluorescein of 0.15 μM. Shown in Figs. 1C–D are mean areas under the curve as a function of anti-oxidant concentration for the NPs and positive control, respectively. ORAC assay revealed that the Y2O3 NPs (Fig. 1C) directly scavenged AAPH-derived free radicals, i.e. by rescuing fluorescein-mediated fluorescence from the free radical quenching effect generated by AAPH. Interestingly, this antioxidant effect plateaued at concentrations higher than 9 μM, likely due to the formation of agglomerates that mask the NP crystal defects which facilitate the electron scavenging activity of Y2O3. Because soluble metal ions can have anti-oxidant effects, we wanted to make sure that the observed scavenging effects of the NPs were not due to soluble yttrium released from the Y2O3 crystals. Therefore we dispersed the NPs in water (35 μM), and then pelleted them. The ORAC assay was repeated on both the NP pellet and the soluble component (supernatant). As shown in Fig. 1E, the supernatant alone possessed no scavenging properties, while the NP pellet fraction performed as in the previous assay confirming that soluble yttrium is not responsible for the observed effect. This hypothesis is indirectly supported by the observation that non-particulate forms of Y2O3 do not have the same anti-oxidant effects as the NP form [14].

Establishment of light damage protocol

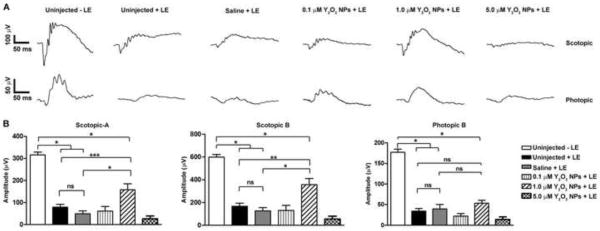

To study the effects of Y2O3 on light-induced retinal damage, we needed to identify conditions under which retinal function was significantly reduced but not completely obliterated. We therefore tested the damaging effect of several light intensities. Adult (approximately postnatal day 30) albino mice were dark adapted for 48 hours and then exposed to either 4000, 6000 or 8000 lux for 2 hours (Fig. 2A). Animals were returned to normal housing conditions (12L:12D, 30 lux) for 30 days and then underwent functional testing by electroretinography (ERG). Scotopic and photopic ERG amplitudes were significantly reduced at the maximum intensity (Fig. 2B, * P<0.001), so 8000 lux was selected for the next sets of experiments.

Figure 2. Optimization of light intensity and exposure paradigm.

(A) Schematic diagram showing the experimental protocol for optimizing light exposure. (B) Maximum scotopic and photopic ERG amplitudes of adult mice exposed to 4000, 6000 and 8000 lux for 2 hours after 48 hours of dark adaptation. Results are plotted as mean ± SEM (* P<0.001, n=4/group). (C) Schematic diagram of the three light exposure paradigms used in the subsequent studies. D: days, LE: light exposure

Subsequent experiments are grouped into three treatment paradigms (Fig. 2C). In the first set of experiments, the pre-treatment paradigm, Y2O3 NPs are delivered 15 days prior to light exposure and follow-up is at 30 days post-light exposure. In the second case, the post-treatment paradigm, the NP injection occurs immediately after light exposure, (with follow-up at 30 days post-light exposure). The third set is the no light paradigm wherein NPs are delivered as in the first case, but no light exposure is given, and follow-up is 45 days after injection (the equivalent of 30 days post-light exposure for the other paradigms).

Effects of NP pretreatment on light-induced retinal damage

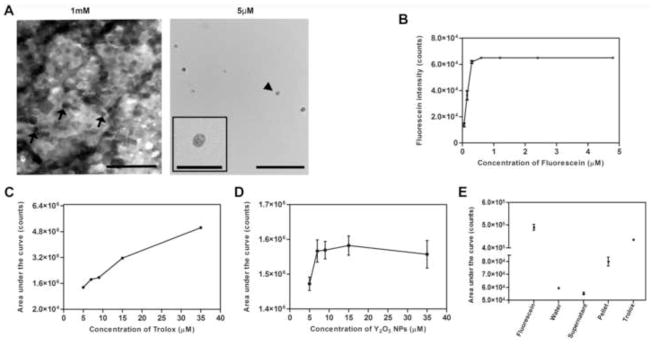

We injected 2 μl of 0.1, 1.0 and 5 μM of Y2O3 NPs in saline or 2 μl of saline alone (control) into the vitreous of adult mice. At 13 days post injection, animals were dark adapted for two days then exposed to 8,000 lux for two hours. At 30 days post-light exposure, full-field scotopic and photopic ERGs were performed (representative traces shown in Fig. 3A). Consistent with our results reported above, uninjected light exposed eyes exhibited significant declines in scotopic and photopic ERG amplitudes (Fig. 3B) compared to untreated animals, and saline provided no significant benefit. Eyes treated with 0.1, 1.0 and 5 μM NPs showed significant improvement in scotopic and photopic ERG function (* P<0.001) compared to uninjected/saline injected animals. Strikingly, the 5 μM group showed complete functional protection; scotopic and photopic wave amplitudes were not significantly different from controls that had received no light exposure.

Figure 3. Pre-treatment with Y2O3 NPs protects retinal function after light stress.

Animals were intravitreally injected with the indicated dose of NPs 15 days prior to acute light exposure at 8,000 lux. (A) Representative scotopic (top) and photopic (bottom) ERGs traces measured at 30 days post light exposure. (B) Quantitation of maximum scotopic and photopic ERG amplitudes. Results are plotted as mean ± SEM. ns: non-significant, * P<0.001, n=10–12/group. LE: light exposure.

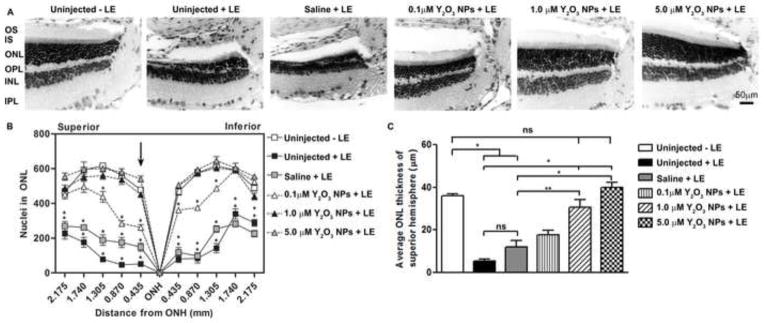

To determine whether this dramatic functional protection was evident on a structural level, retinal histology was assessed (Fig. 4A). The number of photoreceptor nuclei in the outer nuclear layer (ONL) was counted on digitized images obtained at increasing distances from the optic nerve head (ONH) on both inferior and superior regions and plotted as a spider diagram (Fig. 4B). To minimize clutter on the graph, the * indicates P<0.001 only for pairwise comparisons with uninjected controls which did not receive light exposure. We observe that uninjected and saline injected light exposed animals exhibited significant reductions in the number of PRs compared to uninjected animals that were not exposed to light. In contrast, eyes treated with 0.1, 1.0 and 5.0 μM of NPs showed significant rescue in the number of PRs in the ONL, and animals who received 1.0 and 5.0 μM of NPs had PR cell numbers that were not significantly different from controls that were not exposed to light. We also measured ONL thickness in the central superior region which is known to be particularly susceptible to light damage, and observed similar improvements in ONL thickness (Fig. 4C) in groups which received 1.0 or 5.0 μM Y2O3 compared to light exposed controls which did not receive NPs. These results indicate that pre-treatment with Y2O3 NPs can prevent light-induced PR degeneration.

Figure 4. Pre-treatment with Y2O3 NPs protects retinal structure after light stress.

Animals were intravitreally injected with the indicated dose of NPs 15 days prior to 8,000 lux exposure. (A) Representative light micrograph images of H&E stained sections collected at 30 days post-light exposure. Shown are representatives of the regions immediately superior to the optic nerve head (ONH) of treated eyes. Scale bar = 50 μm. (B) The spider diagram quantifies the number of ONL nuclei in a 20x microscope field at increasing distances (indicated on the x-axis) from the ONH along the vertical meridian. Results are mean ± SEM, * P<0.001 for comparison between indicated group and uninjected-light exposed. (C) Plotted is mean ± SEM ONL thickness in the central superior hemisphere (within 435 μm from ONH) ns: non-significant, *p<0.001, **p<0.01, n=3/group. LE: light exposure.

Effects of NP post-treatment on light-induced retinal damage

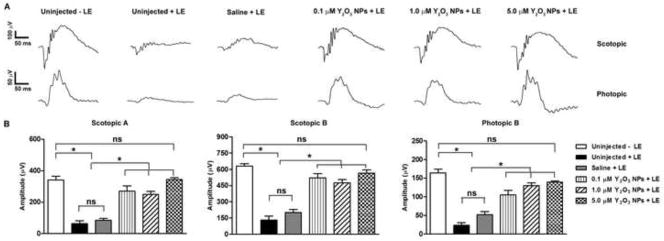

While beneficial effects of NP pre-treatment are useful, often treatment before the insult is not possible. Therefore we asked whether Y2O3 NP-mediated neuroprotection remained when delivered after the insult. After 48 hours of dark adaptation followed by exposure to 8000 lux for 2 hours, mice were kept at 30 lux for 2 hours and then underwent intravitreal injection of Y2O3 NPs or saline. At 30 days post-light exposure, full-field scotopic and photopic ERGs were performed (representative traces shown in Fig. 5A). Delivery of 1.0 μM of Y2O3 NP suspension led to significant improvement in scotopic ERG amplitudes (Fig. 5B) compared to uninjected/saline injected light exposure controls. Mean photopic ERG amplitudes in eyes that received 1.0 μM NPs were slightly higher than negative controls; however the improvement was not statistically significant. Under this treatment paradigm, neither 0.1 nor 5.0 μM NPs mediated significant functional improvement.

Figure 5. Post-treatment with Y2O3 NPs protects retinal function after light stress.

Animals were intravitreally injected with the indicated dose of NPs two hours after acute light exposure at 8,000 lux. (A) Representative scotopic (top) and photopic (bottom) ERGs traces measured at 30 days post light exposure. (B) Quantitation of maximum scotopic and photopic ERG amplitudes. Results are plotted as mean ± SEM. ns: non-significant, * P<0.001, n=10–12/group. LE: light exposure.

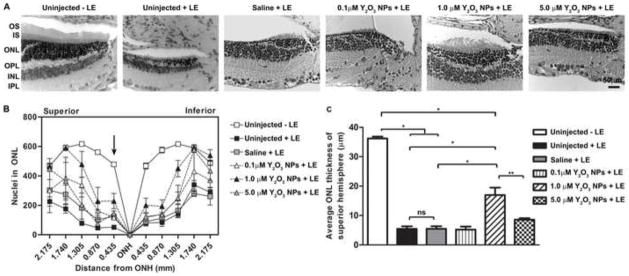

Histological assessment (Fig. 6A) confirmed these findings. Treatment with 1.0 μM NPs mediated improvement in the number of PR nuclei, a change again reflected by ONL thickness (Fig. 6B–C) although histological parameters were not as high as in control animals not exposed to light. Interestingly, the improvement in retinal structure observed in animals receiving 1.0 μM NPs occurred almost entirely in the peripheral retina (both superior and inferior), likely because these regions of the retina receive the least amount of direct light. No structural improvement was observed in retinas which received 0.1 or 5.0 μM NPs. These results suggest that treatment with Y2O3 NPs after light exposure can provide appreciable benefit to the retina; however the magnitude of the effect is not as pronounced as with pre-treatment.

Figure 6. Post-treatment with Y2O3 NPs protects retinal structure after light stress.

Animals were intravitreally injected with the indicated dose of NPs 2 hours after acute light exposure at 8,000 lux. (A) Representative light micrograph images of H&E stained sections collected at 30 days post light exposure. Shown is the region immediately superior to the optic nerve head (ONH). Scale bar = 0 50 μm. (B) The spider diagram quantifies the number of photoreceptor nuclei in a 20x microscope field at increasing distances (indicated on the x-axis) from the ONH along the vertical meridian. Results are mean ± SEM. (C) Plotted is mean ± SEM ONL thickness in the central superior hemisphere (within 435 μm from ONH) ns: non-significant, *p<0.001, **p<0.01, n=3/group. LE: light exposure.

Y2O3 NPs alone do not elicit retinal toxicity

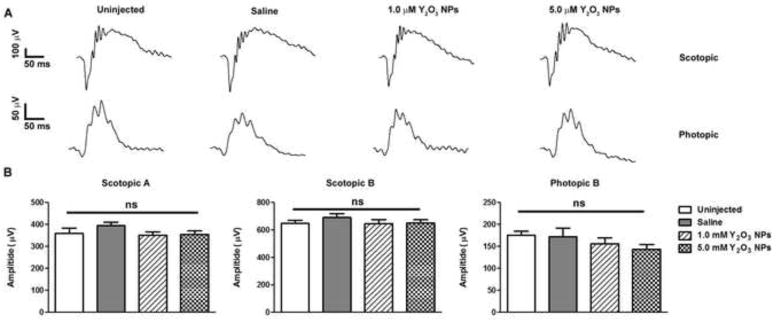

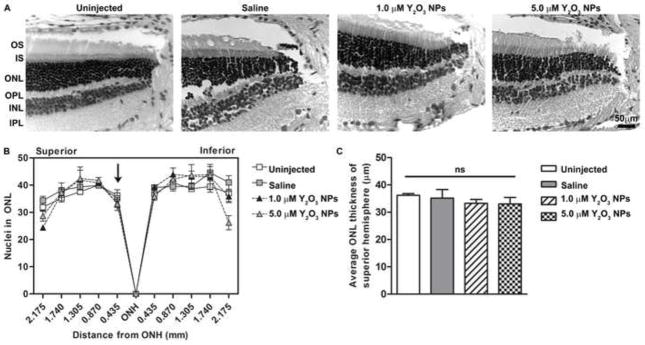

Finally, we conducted studies using 1.0 and 5.0 μM of Y2O3 NPs without light exposure to confirm that the NPs alone exerted no detrimental effects. The lowest dose was eliminated from these studies as it was insufficiently useful to merit additional testing. End-point analysis was conducted at PI-45 days to mimic the first injection protocol (Fig. 2C). ERG and histological analysis at post-injection 45 days showed that the Y2O3 NPs led to no decrease in scotopic or photopic ERG amplitudes (Fig. 7A–B) compared to uninjected or saline-injected controls. This unaltered functional effect was also reflected on a structural level (Fig. 8A). Morphometric analysis (Fig. 8B–C) indicated that delivery of Y2O3 NPs did not result in retinal degeneration as measured by the number of PR nuclei in the ONL or by the ONL thickness in the superior hemisphere. These data suggest that the Y2O3 NPs are well-tolerated after intravitreal delivery and do not elicit any gross negative effects on retinal structure or function and do not physically impair light entry into the retina.

Figure 7. Y2O3 NPs alone do not affect retinal function.

Animals were intravitreally injected with NPs at the indicated doses without light exposure. (A) Representative scotopic (top) and photopic (bottom) ERG traces recorded at post-injection 45 days (refer to Fig. 2C). (B) Quantitation of maximum scotopic and photopic ERG amplitudes are presented as means ± SEM. ns: non-significant, n=8–10/group.

Figure 8. Y2O3 NPs alone do not affect retinal structure.

Animals were intravitreally injected with NPs at the indicated doses without light exposure. (A) Representative light micrograph images of H&E stained sections collected at post-injection 45 days (refer to Fig. 2C). Shown is the region immediately superior to the optic nerve head (ONH). Scale bar = 50 μm. (B) The spider diagram quantifies the number of photoreceptor nuclei in a 20x microscope field at increasing distances (indicated on the x-axis) from the ONH along the vertical meridian. Results are mean ± SEM. (C) Plotted is mean ± SEM ONL thickness in the central superior hemisphere (within 435 μm from ONH) ns: non-significant, n=3/group.

Discussion

The photoreceptor degeneration in the rodent light-damage model has been extensively used and widely characterized as a model in which oxidative stress and the accumulation of ROS is an early part of the death mechanism (for an excellent review, see [28]). In this model there is continuous bleaching of photoreceptor opsin proteins that consecutively absorb radiant energy and cause the excitation of electrons from the ground state to the excited state [25, 35]. Due to the instability of the excited state, the energy is dissipated in different ways. One of them is the return of excited electrons to the ground state while the other option is to disperse through several interactions into ROS. PR cells have abundant polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) which undergo lipid peroxidation in the presence of toxic ROS [3, 7, 8], eventually resulting in extensive damage to the membranous structures of the PR outer segment. In this study we clearly demonstrate that Y2O3 NPs possess direct free radical scavenging activity, supporting the idea that reduction in oxidative stress underlies Y2O3-mediated protection of photoreceptor cells from light-mediated damage. Interestingly, we observe that the NPs are most effective when delivered prior to the oxidative insult, but also provide some protection when delivered post-insult. The atomic properties of yttrium contribute to its functionality as an anti-oxidant. Although technically a transition metal with no f-orbital electron ([Kr]5s24d1), yttrium’s cationic (Y+3) radius falls into the range for lanthanide elements. This, combined with similarities in many other physical properties makes yttrium very lanthanide-like contributing to its anti-oxidant properties. Yttrium remains exclusively in a +3 oxidation state in its stable, virtually inert, oxide (Y2O3) form. In addition, Y2O3 crystals (as in the NPs) exhibit nonstoichiometric defects under normal temperature and pressure [14]. These non-stoichiometric crystal defects coupled with the energetics that favor the oxide form work as a trap for reactive free radicals. The free radicals generated by the AAPH were directly scavenged by Y2O3 NPs showing that these NPs could be a potential antioxidant material with significant free radical scavenging capacity.

Importantly, we show here that the Y2O3 NPs are well-tolerated and non-toxic in the retina. The lack of functional groups on the surface of these NPs make them an excellent candidate for any kind of biomolecular interaction in vivo [36]. Furthermore, the yttrium (+3) cations are not able to diffuse out from the oxide lattice and therefore don’t show any metal ion induced toxicity as observed with other soluble metal oxides [37]. In support of this safe, inert profile, Y2O3 NPs are used in bioimaging applications [38] without toxicity. Finally, Y2O3 protects neuronal cells against oxidative damage in vitro at concentrations similar to what we show here with no toxic response [14].

One of the most interesting outcomes we report is the dual observation that pretreatment with the Y2O3 NPs is more effective than treatment after light exposure, and that the highest dose of NPs (5.0 μM) is not effective when delivered after light exposure. This suggests that efficacy is improved when the particles have more time to penetrate through the vitreous and retina, and that transport of NPs through the vitreous and retina may be impaired at higher concentrations (possibly due to aggregation). Previously it has been observed that Y2O3 NPs with bared surface tend to aggregate with increasing concentration [36]. At low concentrations (0.1 and 1.0 μM) the NPs tend to be less aggregated and their mobility through the vitreous will not be retarded, allowing them to diffuse to the retina with ease compared to the higher dose (5.0 μM). If sufficient time is given (i.e. in the pre-treatment paradigm), the NPs at all three doses can diffuse through the vitreous and penetrate the retina where they can exert their beneficial effect. However, when treatment is delivered right after the light exposure, the higher dose is not as effective, likely since it is slower to reach the target area (i.e. photoreceptors), while the lower doses can penetrate through the vitreous more quickly thus providing some protection against degeneration.

Free radicals are generated inside the cells under conditions of light stress. These ROS are very unstable redox active species with short half-lives (e.g. the cellular half-life of hydroxyl radical is only 10−9 s), and therefore they do not diffuse far from the site of production [6]. This phenomenon means that the Y2O3 NPs are most likely taken into the PR cells to exert their antioxidant effects but we have not yet confirmed the uptake mechanism for these particles in PR cells. The evaluation of the cellular uptake mechanisms of Y2O3 NPs is underway. Furthermore, the fact that we observe neuroprotection two weeks after NP delivery suggests that the particles are quite stable in the retina. One issue of interest is whether inhibition of PR cell death is due to induction of endogenous antioxidant defense systems in the cell or direct antioxidant effects of the NPs. Although the first option is a theoretical possibility, the chemistry of Y2O3 makes the second much more likely. Our ORAC assay demonstrates that Y2O3 NPs have direct free radical scavenging ability, and previous work has also demonstrated that Y2O3 has direct ROS scavenging activity [14, 20].

Here we show that antioxidant Y2O3 NPs efficiently protect PR cells from light-induced retinal degeneration and loss of vision. Our studies are limited to the eye, however this protective effect could likely be extended to other non-ocular neurodegenerative disorders in which ROS have been implicated such as Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, Huntington’s disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [39]. In conclusion, these results suggest that Y2O3 NPs may be an excellent addition to our available repertoire of retinal antioxidants and could be useful in targeting other disorders which are associated with oxidative-stress.

Highlights.

Oxidative stress is a major component of many blinding retinal diseases.

Antioxidant therapy is a necessary part of a multi-pronged therapeutic approach for these diseases.

Due to their unique chemistry, yttrium oxide (Y2O3) nanoparticles are excellent free radical scavengers.

Y2O3 is well-tolerated in the retina.

Y2O3 prevents retinal degeneration in a murine light-damage disease model.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Muhammed Al Taai for his technical assistance. This work was supported by the National Eye Institute (EY018656-MIN, EY22778-MIN), the Foundation Fighting Blindness (MIN), the Oklahoma Center for the Advancement of Science and Technology (SMC, ZH, and MIN), and Fight for Sight (RNM).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Trifunovic D, Sahaboglu A, Kaur J, Mencl S, Zrenner E, Ueffing M, Arango-Gonzalez B, Paquet-Durand F. Neuroprotective strategies for the treatment of inherited photoreceptor degeneration. Curr Mol Med. 2012;12:598–612. doi: 10.2174/156652412800620048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Du Y, Veenstra A, Palczewski K, Kern TS. Photoreceptor cells are major contributors to diabetes-induced oxidative stress and local inflammation in the retina. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110:16586–16591. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1314575110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nowak JZ. Oxidative stress, polyunsaturated fatty acids-derived oxidation products and bisretinoids as potential inducers of CNS diseases: focus on age-related macular degeneration. Pharmacol Rep. 2013;65:288–304. doi: 10.1016/s1734-1140(13)71005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Auten RL, Davis JM. Oxygen toxicity and reactive oxygen species: the devil is in the details. Pediatr Res. 2009;66:121–127. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181a9eafb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lu L, Hackett SF, Mincey A, Lai H, Campochiaro PA. Effects of different types of oxidative stress in RPE cells. J Cell Physiol. 2006;206:119–125. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dickinson BC, Chang CJ. Chemistry and biology of reactive oxygen species in signaling or stress responses. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:504–511. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cabrera MP, Chihuailaf RH. Antioxidants and the integrity of ocular tissues. Veterinary medicine international. 2011;2011:905153. doi: 10.4061/2011/905153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Catala A. An overview of lipid peroxidation with emphasis in outer segments of photoreceptors and the chemiluminescence assay. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology. 2006;38:1482–1495. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fletcher AE. Free radicals, antioxidants and eye diseases: evidence from epidemiological studies on cataract and age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmic Res. 2010;44:191–198. doi: 10.1159/000316476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sasaki M, Ozawa Y, Kurihara T, Noda K, Imamura Y, Kobayashi S, Ishida S, Tsubota K. Neuroprotective effect of an antioxidant, lutein, during retinal inflammation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:1433–1439. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cai J, Nelson KC, Wu M, Sternberg P, Jr, Jones DP. Oxidative damage and protection of the RPE. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2000;19:205–221. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(99)00009-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chong EW, Wong TY, Kreis AJ, Simpson JA, Guymer RH. Dietary antioxidants and primary prevention of age related macular degeneration: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2007;335:755. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39350.500428.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martinez-Fernandez de la Camara C, Salom D, Sequedo MD, Hervas D, Marin-Lambies C, Aller E, Jaijo T, Diaz-Llopis M, Millan JM, Rodrigo R. Altered antioxidant-oxidant status in the aqueous humor and peripheral blood of patients with retinitis pigmentosa. PloS one. 2013;8:e74223. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schubert D, Dargusch R, Raitano J, Chan SW. Cerium and yttrium oxide nanoparticles are neuroprotective. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;342:86–91. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.01.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shih SJ, Yu YJ, Wu YY. Manipulation of dopant distribution in yttrium-doped ceria particles. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2012;12:7954–7962. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2012.6592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang M, Tie S. Fabrication of novel luminor Y(2)O(3):Eu(3+)@SiO(2)@YVO(4):Eu(3+) with core/shell heteronanostructure. Nanotechnology. 2008;19:075711. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/19/7/075711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andelman T, Gordonov S, Busto G, Moghe PV, Riman RE. Synthesis and Cytotoxicity of Y(2)O(3) Nanoparticles of Various Morphologies. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2009;5:263–273. doi: 10.1007/s11671-009-9445-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Traina CA, Dennes TJ, Schwartz J. A modular monolayer coating enables cell targeting by luminescent yttria nanoparticles. Bioconjugate chemistry. 2009;20:437–439. doi: 10.1021/bc800551x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Setua S, Menon D, Asok A, Nair S, Koyakutty M. Folate receptor targeted, rare-earth oxide nanocrystals for bi-modal fluorescence and magnetic imaging of cancer cells. Biomaterials. 2010;31:714–729. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.09.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hosseini A, Baeeri M, Rahimifard M, Navaei-Nigjeh M, Mohammadirad A, Pourkhalili N, Hassani S, Kamali M, Abdollahi M. Antiapoptotic effects of cerium oxide and yttrium oxide nanoparticles in isolated rat pancreatic islets. Human & experimental toxicology. 2013;32:544–553. doi: 10.1177/0960327112468175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen J, Patil S, Seal S, McGinnis JF. Rare earth nanoparticles prevent retinal degeneration induced by intracellular peroxides. Nat Nanotechnol. 2006;1:142–150. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2006.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tanito M, Agbaga MP, Anderson RE. Upregulation of thioredoxin system via Nrf2-antioxidant responsive element pathway in adaptive-retinal neuroprotection in vivo and in vitro. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;42:1838–1850. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tanito M, Elliott MH, Kotake Y, Anderson RE. Protein modifications by 4-hydroxynonenal and 4-hydroxyhexenal in light-exposed rat retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:3859–3868. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Song D, Song Y, Hadziahmetovic M, Zhong Y, Dunaief JL. Systemic administration of the iron chelator deferiprone protects against light-induced photoreceptor degeneration in the mouse retina. Free radical biology & medicine. 2012;53:64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Youssef PN, Sheibani N, Albert DM. Retinal light toxicity. Eye (Lond) 2011;25:1–14. doi: 10.1038/eye.2010.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Driscoll C, O’Connor J, O’Brien CJ, Cotter TG. Basic fibroblast growth factor-induced protection from light damage in the mouse retina in vivo. Journal of neurochemistry. 2008;105:524–536. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.05189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mandal MN, Patlolla JM, Zheng L, Agbaga MP, Tran JT, Wicker L, Kasus-Jacobi A, Elliott MH, Rao CV, Anderson RE. Curcumin protects retinal cells from light-and oxidant stress-induced cell death. Free radical biology & medicine. 2009;46:672–679. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wenzel A, Grimm C, Samardzija M, Reme CE. Molecular mechanisms of light-induced photoreceptor apoptosis and neuroprotection for retinal degeneration. Progress in retinal and eye research. 2005;24:275–306. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cingolani C, Rogers B, Lu LL, Kachi S, Shen JK, Campochiaro PA. Retinal degeneration from oxidative damage. Free Radical Bio Med. 2006;40:660–669. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mitra RN, Han Z, Merwin M, Al Taai M, Conley SM, Naash MI. Synthesis and characterization of glycol chitosan DNA nanoparticles for retinal gene delivery. Chem Med Chem. 2014;9:189–196. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201300371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mitra RN, Doshi M, Zhang X, Tyus JC, Bengtsson N, Fletcher S, Page BD, Turkson J, Gesquiere AJ, Gunning PT, Walter GA, Santra S. An activatable multimodal/multifunctional nanoprobe for direct imaging of intracellular drug delivery. Biomaterials. 2012;33:1500–1508. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.10.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee SS, Song W, Cho M, Puppala HL, Nguyen P, Zhu H, Segatori L, Colvin VL. Antioxidant properties of cerium oxide nanocrystals as a function of nanocrystal diameter and surface coating. ACS Nano. 2013;7:9693–9703. doi: 10.1021/nn4026806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Farjo R, Skaggs J, Quiambao AB, Cooper MJ, Naash MI. Efficient non-viral ocular gene transfer with compacted DNA nanoparticles. PLoS One. 2006;1:e38. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Han Z, Conley SM, Makkia RS, Cooper MJ, Naash MI. DNA nanoparticle-mediated ABCA4 delivery rescues Stargardt dystrophy in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:3221–3226. doi: 10.1172/JCI64833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wielgus AR, Roberts JE. Retinal photodamage by endogenous and xenobiotic agents. Photochemistry and photobiology. 2012;88:1320–1345. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2012.01174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Traina CA, Schwartz J. Surface modification of Y2O3 nanoparticles. Langmuir. 2007;23:9158–9161. doi: 10.1021/la701653v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Horie M, Fukui H, Endoh S, Maru J, Miyauchi A, Shichiri M, Fujita K, Niki E, Hagihara Y, Yoshida Y, Morimoto Y, Iwahashi H. Comparison of acute oxidative stress on rat lung induced by nano and fine-scale, soluble and insoluble metal oxide particles: NiO and TiO2. Inhal Toxicol. 2012;24:391–400. doi: 10.3109/08958378.2012.682321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hilderbrand SA, Shao F, Salthouse C, Mahmood U, Weissleder R. Upconverting luminescent nanomaterials: application to in vivo bioimaging. Chemical communications. 2009:4188–4190. doi: 10.1039/b905927j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bowling AC, Beal MF. Bioenergetic and oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases. Life Sci. 1995;56:1151–1171. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(95)00055-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]