Abstract

BACKGROUND

Under the Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Accreditation and Quality Improvement Program, hospitals will receive risk-adjusted outcome feedback for peer comparisons and benchmarking. It remains uncertain whether bariatric outcomes have adequate reliability to identify outlying performance, especially for hospitals with low caseloads that will be included in the program. We explored the ability of risk-adjusted outcomes to identify outlying hospital performance with bariatric surgery over a range of hospital caseloads.

STUDY DESIGN

We used the 2009-10 State Inpatient Databases for 12 states (N=31,240 patients) to assess different outcomes (complications, reoperation, and mortality) following bariatric stapling procedures. We first quantified outcome reliability on a 0 (no reliability) to 1 (perfect reliability) scale. We then assessed whether risk- and reliability-adjusted outcomes could identify outlying performance among hospitals with different annual caseloads.

RESULTS

Overall and serious complications had the highest overall reliability, but this was heavily dependent upon caseload. For example, among hospitals with the lowest caseloads (mean 56 cases/yr), reliability for overall complications was 0.49 and 6.0% of hospitals had outlying performance. For hospitals with the highest caseloads (mean 298 cases/yr), reliability for overall complications was 0.79 and 30.3% of hospitals had outlying performance. Reoperation had adequate reliability for hospitals with caseloads higher than 120 cases/yr. Mortality had unacceptably low reliability regardless of hospital caseloads.

CONCLUSIONS

Overall complications and serious complications have adequate reliability for distinguishing outlying performance with bariatric surgery, even for hospitals with low annual caseloads. Rare outcomes such as reoperations have inadequate reliability to inform peer-based comparisons for hospitals with low annual caseloads, and mortality has unacceptably low reliability for bariatric performance profiling.

INTRODUCTION

Bariatric surgery is one of the most common gastrointestinal operations performed in the United States.(1, 2) With growing national emphasis on surgical quality improvement, the American Society of Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery and American College of Surgeons partnered to create the Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Accreditation and Quality Improvement Program (MBSAQIP) in 2012.(3) Participating centers will be expected to monitor their outcomes both to evaluate internal opportunities for improvement as well as to compare their risk-adjusted outcomes to other centers.(4) It will be important, both for targeted quality improvement and for stakeholder buy-in, to use reliable risk-adjusted outcome metrics for accurate benchmarking and peer comparisons in the quality improvement program.

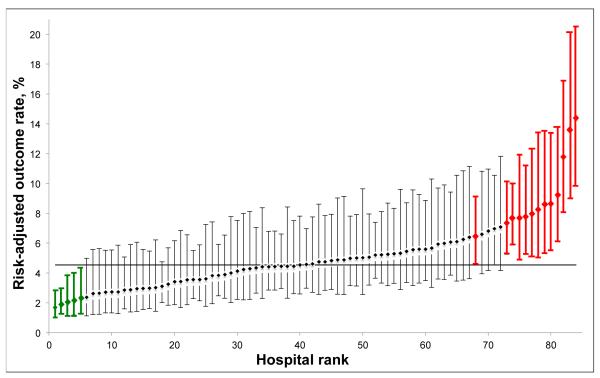

However, bariatric outcomes may not have sufficient reliability to differentiate hospital performance and promote quality improvement efforts. Due to low event rates and small caseloads, many surgical outcomes cannot reliably differentiate hospital performance for a variety of procedures.(5-7) Given national trends towards improved safety in bariatric surgery, the ability for bariatric outcomes in particular for identifying outlying hospital performance is unclear.(8-11) Outlier detection is an important criterion of an outcome’s usefulness in quality improvement platforms, because information from centers with statistically better performance (low outliers) can be used to develop best practices and centers with statistically worse performance (high outliers) to identify quality improvement targets (Figure 1). MBSAQIP will include hospitals with caseloads ranging from very small (>50 annual stapling cases) to very large.(4) Among hospitals with small caseloads, many outcomes may prove to be unreliable indicators of outlier performance status. It is, therefore, of paramount importance to identify reliable outcomes to guide quality improvement efforts.

Figure 1.

Example performance report (any complication, hospitals with at least 125 cases/yr, laparoscopic gastric bypass procedures). Diamonds: hospital risk adjusted outcome rates with 95% confidence intervals. Green: low outliers, have 95% confidence intervals less than the average outcomes rate. Red: high outliers, have 95% confidence intervals greater than the average outcomes rate. Solid horizontal line, overall average outcomes rate.

In this study, we explored the ability of four commonly reported risk-adjusted outcomes to identify outlier performance for bariatric surgery. We assessed outcome reliability at different levels of hospital caseloads, and then assessed the ability of risk- and reliability-adjusted outcomes to identify outlying hospital performance at different caseloads and reporting thresholds.

METHODS

Data source and study population

We assessed the 2009-10 State Inpatient Databases for 12 states (Arizona, California, Florida, Iowa, Massachusetts, Maryland, North Carolina, Nebraska, New Jersey, New York, Washington, and Wisconsin), which contain all inpatient discharges from short-term, nonfederal, acute care, general and specialty hospitals in participating states.(12) Data include patient demographics and primary insurer information, as well as diagnoses and procedures identified by International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes. For the present study, we identified patients undergoing laparoscopic or open bariatric surgical procedures using a previously validated coding algorithm.(8) In brief, we identified patients with an ICD-9-CM procedure code corresponding to bariatric surgery, a primary or secondary diagnosis code indicating morbid obesity, and a diagnosis related group code for weight loss surgery. We excluded patients undergoing laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding procedures, patients younger than 18 years, and emergent procedures. In addition, we excluded patients who underwent surgery in hospitals that submitted fewer than 50 stapling procedures in 2009. This would allow our cohort to simulate hospitals with “Comprehensive Center” accreditation and avoid examining hospitals that may achieve other levels of accreditation under the new standards.(4)

Outcomes

Our main outcome variables were overall complications, serious complications, reoperation for any reason, and inpatient mortality. We identified complications and reoperations most applicable to bariatric surgery from secondary ICD-9-CM diagnosis and procedure codes.(13) Complications encompassed splenic injury/splenectomy (41.2, 41.43, 41.5), intraoperative or postoperative hemorrhage/hematoma or transfusion (998.11-12, 99.04, 99.09), anastomotic leak or percutaneous drainage (998.6, 54.91), wound infection/seroma/dehiscence (998.5-51, 998.59, 998.13, 998.3), bowel obstruction (560.0-9), pulmonary complications, pneumonia or tracheotomy (997.3, 481, 482.0-9, 485, 486, 518.81, 31,1, 31,29), cardiac complications or myocardial infarction (997.1, 410.0-9), neurological complications and stroke (997.01-03, 431.00-431.91, 433.00-91, 434.00-91, 436, 437.1), urinary tract complications (997.5), renal failure or dialysis (584.1-9, 38.95, 39.95), venous thromboembolism (415.1-11, 415.19, 453.8, 453.9) and postoperative shock (998.0). We defined serious complications as the presence of any complication and extended hospital stay (≥5 days), which has been used in other studies of bariatric outcomes.(8, 9) Reoperations were identified from ICD-9-CM procedure codes indicating secondary procedures during the index hospitalization and included reopening of surgical site, closure of dehiscence, control of hemorrhage, splenectomy, removal of retained foreign body, management of deep surgical site infection or organ injury repairs.

Statistical Analysis

The goals of our analysis were to explore the reliability of various bariatric surgery outcomes and to examine their ability to detect outlier hospitals. Analogous to statistical power calculations in clinical trials designed to reduce type II error (failure to detect a difference between groups when one truly exists), reliability represents the degree to which adjusted outcome rates reflect true quality differences between providers.(14) The main determinant of outcome reliability is sample size, i.e. hospital caseload.(5, 14, 15) To explore the influence of hospital caseloads on performance reporting, we first compared outcome reliability and outliers across terciles of hospital caseload (lowest caseloads, middle caseloads, highest caseloads). Then, we examined outcome reliability and outliers when limiting performance reports to hospitals meeting different caseload thresholds chosen a priori from historical and current accreditation standards (none, 50 cases/yr, 100 cases/yr, and 125 cases/yr).

Calculating hospital adjusted outcome rates and outliers

To calculate hospital adjusted outcome rates, we used logistic regression models to calculate each patient’s predicted probability of experiencing each outcome (overall complications, serious complications, reoperation and hospital mortality). All models adjusted for patient age, sex, race, primary insurer, median ZIP code income, procedure type (laparoscopic gastric bypass, open gastric bypass, other stapling procedure), and 29 comorbidities as defined by Elixhauser and colleagues, which are widely used for risk-adjustment using administrative data.(16, 17) Dividing observed outcomes by the sum of predicted outcomes from the logistic regression models yields hospital observed: expected (O:E) ratios, which when multiplied by the cohort’s overall outcome rate yields hospital risk-adjusted rates.

To account for random outcome variation due to caseload differences, we further adjusted hospital outcome rates and generated hospital-specific standard errors using hierarchical modeling and empirical Bayes techniques, sometimes referred to as ‘reliability adjustment.’(18-20) In brief, reliability adjustment “shrinks” hospital outcome rates towards overall outcome rate proportionally to their level of reliability, with lower caseload hospitals generally experiencing more adjustment (because of their lower overall reliability) than higher caseload hospitals. Reliability adjustment provides more stable performance estimates and improved hospital performance prediction compared to non-hierarchical modeling.(19, 21) Both regional and national quality improvement platforms use reliability adjustment for performance reporting,(22, 23) and MBSAQIP is considering reporting reliability-adjusted outcome rates to accredited centers.(4)

We identified outlier performance status based on the 95% confidence interval of a hospital’s risk-adjusted rate. If the upper limit of a hospital’s confidence interval was less than the average rate (i.e. the 95% confidence interval was both less than and also excluded the average outcome rate), that hospital was a ‘low’ outlier (better than expected performance). Conversely, if the lower limit of a hospital’s outcome rate confidence interval was greater than the average rate, it was a ‘high’ outlier (worse than expected performance). Please see Figure 1 for examples of low and high outliers in a performance report. For our first analysis, we calculated reliability-adjusted outcome rates and outliers within each hospital caseload tercile. In our second analysis, we calculated adjusted outcome rates from all hospitals at once.

Calculating outcome reliability

Reliability is an estimation of the degree to which differences in hospital outcome rates reflect true quality differences after accounting for patient risk.(14) Mathematically, reliability is calculated using the formula [signal/(signal+noise)], with possible results ranging from 0 (no reliability) to 1 (perfect reliability). Commonly accepted reliability thresholds for performance monitoring are 0.70-0.90.(14, 15) For this study, we estimated reliability using previously described methods.(6, 7) In brief, we used hierarchical regression models with the hospital specified as the higher level for each outcome. ‘Signal’ represents hospital-level variation after controlling for known influences (patient comorbidities, insurance, procedure type, etc). We define ‘signal’ as the hospital-level random intercept variance in the fully adjusted hierarchical model (using the covariates described above). ‘Noise’ represents within-hospital measurement error and is influenced by the risk-adjustment model used and hospital caseload (sample size). We estimated each hospital’s ‘noise’ using standard techniques for measuring the standard error of their predicted outcome rates.

Finally, to assess the robustness of our findings, we performed several sensitivity analyses. In one, we assessed reliability and outliers for laparoscopic gastric bypass procedures only. In another, we categorized hospitals a priori using historical caseload cutoffs for accreditation (<50 cases, 50-124 cases, ≥125 cases) rather than used caseload terciles. Results from both analyses were nearly identical to those presented below.

We performed all analyses using STATA release 12 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). All reported p-values are two-sided with alpha set at 0.05. All analyses were conducted in accordance with the data use agreement for HCUP data through the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.(12) The University of Michigan Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol.

RESULTS

Characteristics of adults undergoing laparoscopic or open stapling procedures in 12 states in 2010 are shown in Table 1. Overall, we identified 31,240 adult patients in 198 hospitals. Patient demographics, comorbidities and procedures were similar across hospital caseload terciles, with the exception of more laparoscopic gastric bypass procedures in hospitals with the highest caseloads (92.6%) than hospitals with the lowest caseloads (82.9%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients Undergoing Laparoscopic or Open Bariatric Stapling Procedures, State Inpatient Databases for 12 States, 2010

| Lowest caseloads, 67 hospitals |

Medium caseloads, 65 hospitals |

Highest caseloads, 66 hospitals |

Total, 198 hospitals |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caseload, mean (SD) | 56.4 (21.8) | 119.7 (21.3) | 298.2 (162.7) | 157.8 (140.1) |

| n | 3,781 | 7,780 | 19,679 | 31,240 |

| Patient demographics, n (%) |

||||

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 43.7 (11.3) | 44.9 (11.7) | 44.7 (11.6) | 44.6 (11.6) |

| Female | 2931 (77.6) | 6011 (77.8) | 15349 (78.4) | 24291 (78.2) |

| Non-white race | 1058 (30.5) | 2002 (30.2) | 5284 (32) | 8344 (31.3) |

| Medicare insurance | 401 (10.6) | 969 (12.5) | 2144 (10.9) | 3514 (11.2) |

| Procedure types, n (%) | ||||

| Laparoscopic gastric bypass |

3133 (82.9) | 6882 (88.5) | 18225 (92.6) | 28240 (90.4) |

| Open gastric bypass | 373 (9.9) | 614 (7.9) | 938 (4.8) | 1925 (6.2) |

| Other bariatric procedure |

275 (7.3) | 284 (3.7) | 516 (2.6) | 1075 (3.4) |

| Comorbidities, n (%)* | ||||

| Hypertension | 2021 (53.5) | 4245 (54.6) | 10848 (55.1) | 17114 (54.8) |

| Congestive heart failure | 38 (1.0) | 89 (1.1) | 216 (1.1) | 343 (1.1) |

| Diabetes | ||||

| Without chronic complications |

1110 (29.4) | 2420 (31.1) | 6090 (30.9) | 9620 (30.8) |

| With chronic complications |

59 (1.6) | 171 (2.2) | 381 (1.9) | 611 (2.0) |

| Chronic pulmonary disease |

669 (17.7) | 1358 (17.5) | 3630 (18.4) | 5657 (18.1) |

| Liver disease | 349 (9.2) | 780 (10) | 2691 (13.7) | 3820 (12.2) |

| Hypothyroidism | 364 (9.6) | 778 (10) | 1884 (9.6) | 3026 (9.7) |

| Depression | 807 (21.3) | 1605 (20.6) | 3505 (17.8) | 5917 (18.9) |

| Psychoses | 92 (2.4) | 166 (2.1) | 443 (2.3) | 701 (2.2) |

| Fluid and electrolyte disorders |

195 (5.2) | 214 (2.8) | 353 (1.8) | 762 (2.4) |

| Deficiency anemias | 149 (3.9) | 288 (3.7) | 826 (4.2) | 1263 (4) |

| Other neurologic disorders |

60 (1.6) | 114 (1.5) | 273 (1.4) | 447 (1.4) |

| Coagulopathy | 20 (0.5) | 33 (0.4) | 83 (0.4) | 136 (0.4) |

| Peripheral vascular disease |

14 (0.4) | 35 (0.4) | 88 (0.4) | 137 (0.4) |

| Postoperative outcomes† | ||||

| Any complication | 258 (6.8) | 449 (5.8) | 973 (4.9) | 1680 (5.4) |

| Serious complications | 77 (2.0) | 175 (2.2) | 296 (1.5) | 548 (1.8) |

| Reoperation | 36 (1.0) | 56 (0.7) | 144 (0.7) | 236 (0.8) |

| Pulmonary complications |

55 (1.5) | 74 (1.0) | 131 (0.7) | 260 (0.8) |

| Cardiac complications | 28 (0.7) | 52 (0.7) | 118 (0.6) | 198 (0.6) |

Table 2 shows adjusted outcome rates, outcome reliability and outlier detection across terciles of hospital caseloads. The ranges of hospitals’ adjusted outcome rates were broadest for overall complications (mean 6.1%, range 1.8% to 34.3%) and serious complications (mean 2.0%, range 0.6%-6.8%) and narrowest for mortality (mean 0.1%, range 0.1%-0.4%). The most reliable outcome was overall complications (mean reliability 0.664), followed by serious complications (mean reliability 0.475), and reoperation (mean reliability 0.374). Mortality was the least frequent and least reliable outcome (Table 2). As hospital caseloads increased, mean outcome reliability increased, as did the proportion of outlier hospitals. Notably, all groups of hospitals had outliers for overall complications and serious complications. For example, among hospitals with the lowest caseloads (mean 56.4 cases), mean reliability for overall complications was 0.491 and 4 (6.0%) hospitals had outlier performance. Among hospitals with the highest caseloads (mean 298.2 cases), mean reliability for overall complications was 0.785 and 20 (30.3%) hospitals had outlying performance (Table 2). For outcomes with less frequent event rates (e.g. reoperation and mortality), reliability levels and proportions of outlying centers were lower, but displayed the same overall trends as overall complications.

Table 2.

Risk and Reliability Adjusted Outcomes Rate Variation and Proportion of Outliers According to Different Caseload Thresholds

| Hospital caseload | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | Overall, 198 hospitals |

Lowest caseloads, 67 hospitals |

Medium caseloads, 65 hospitals |

Highest caseloads, 66 hospitals |

| Overall complications | ||||

| Mean risk-and reliability adjusted rate, % (range) |

6.1 (1.8-34.3) |

7.6 (3.2-18.2) |

6.8 (2.8-38.0) |

5.5 (1.9-14.6) |

| Outcome reliability, mean (SD) |

0.664 (0.166) |

0.491 (0.136) |

0.726 (0.051) |

0.785 (0.066) |

| Outlier centers, n (%) | ||||

| Any | 34 (17.1) | 4 (6.0) | 9 (13.8) | 20 (30.3) |

| High | 26 (13.1) | 4 (6.0) | 9 (13.8) | 15 (22.7) |

| Low | 8 (4.0) | 0 | 0 | 5 (7.6) |

| Any serious complication | ||||

| Mean risk-and reliability adjusted rate, % (range) |

2.0 (0.6-6.8) |

2.0 (0.9-9.6) |

2.2 (1.2-8.6) |

1.5 (0.5-7.0) |

| Outcome reliability, mean (SD) |

0.475 (0.185) |

0.423 (0.148) |

0.484 (0.093) |

0.639 (0.100) |

| Outlier centers, n (%) | ||||

| Any | 13 (6.6) | 5 (7.5) | 5 (7.7) | 6 (9.1) |

| High | 12 (6.1) | 5 (7.5) | 5 (7.7) | 5 (7.6) |

| Low | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.5) |

| Reoperation | ||||

| Mean risk-and reliability adjusted rate, % (range) |

0.9 (0.3-2.8) |

1.0 (0.5-2.4) |

0.9 (0.5-3.1) |

0.9 (0.3-2.3) |

| Outcome reliability, mean (SD) |

0.374 (0.169) |

0.185 (0.083) |

0.412 (0.084) |

0.517 (0.103) |

| Outlier centers, n (%) | ||||

| Any | 11 (5.6) | 0 | 5 (7.7) | 9 (13.6) |

| High | 11 (5.6) | 0 | 5 (7.7) | 8 (12.1) |

| Low | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.5) |

| Inpatient mortality | ||||

| Mean risk-and reliability adjusted rate, % (range) |

0.1 (0.1-0.4) |

0.1 (0.1-0.1) |

0.1 (0.1-2.4) |

0.1 (0.1-0.1) |

| Outcome reliability, mean (SD) |

0.117 (0.105) |

0 | 0.216 (0.109) |

0.082 (0.047) |

| Outlier centers, n (%) | ||||

| Any | 2 (1.0) | 0 | 1 (1.5) | 0 |

| High | 2 (1.0) | 0 | 1 (1.5) | 0 |

| Low | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

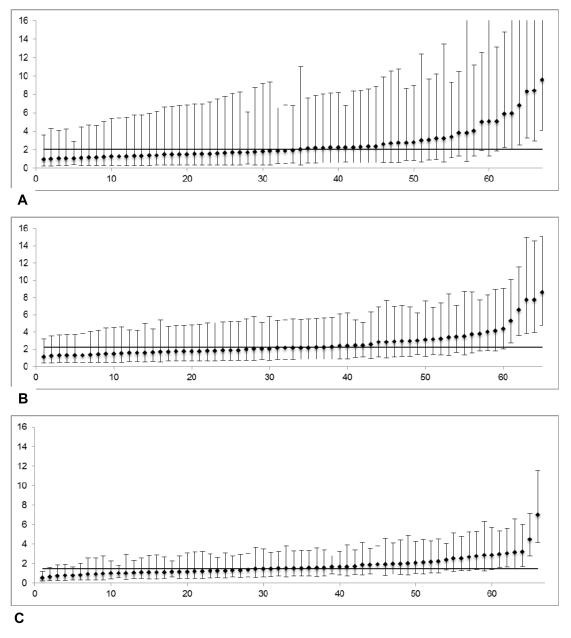

Figure 2 demonstrates performance reports for a reliability-adjusted outcome (serious complications) across different hospitals based on their caseloads. As expected, the precision of hospital outcome rates was greater (i.e. narrower 95% confidence intervals) with higher caseloads. High outliers (worse than average performance) were seen in all groups (Figures 2a c), but low outliers (better than average performance) were only seen at the highest caseloads (Figure 2c) Results for other outcomes were similar, with the exception of mortality, where no low outliers were identified even at the highest caseloads.

Figure 2.

(A-C) Risk-and reliability adjusted outcome rates across hospital caseload terciles (serious complications). Y-axis, percent events (%), X-axis, hospital rank. (A) Lowest caseloads (mean 56.4 cases/y); reliability 0.423. (B) Middle caseloads (mean 119.7 cases/y); reliability 0.484. (C) Highest caseloads (mean 298.2 cases/y); reliability 0.639. Y-axis scale is the same for all figures, to illustrate shrinking of 95% confidence intervals as caseloads.

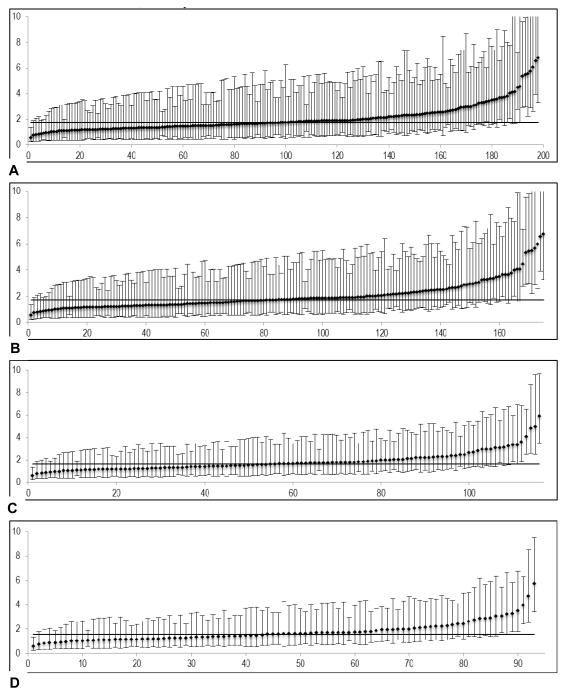

Figure 3a-d shows an example performance report for an outcome (serious complications) generated using all hospitals, then sequentially limiting the report to hospitals meeting caseload thresholds. While some high outlier hospitals were lost as reporting thresholds increased, the overall proportion of outliers increased, demonstrating that the main effect of increasing caseload thresholds for reporting was to reduce the number of lower caseload hospitals with statistically ‘average’ performance (figure 3a-d).

Figure 3.

Risk-and reliability adjusted outcome rates (serious complications) at different caseload thresholds for reporting. Y-axis: percent events (%), X-axis: hospital rank. (A) No caseload threshold; reliability 0.475. (B) Reporting threshold 50 cases/y; reliability 0.508. (C) Reporting threshold 100 cases/y; reliability 0.527. (D) Reporting threshold 125 cases/y; reliability 0.534.

Our sensitivity analyses examining laparoscopic gastric bypass procedures and using different caseloads to define hospital groups showed similar results (Appendix 1, A and B, online only). Hospital mortality was too rare for laparoscopic gastric bypass (0.06%) that we did not examine it as an outcome for that procedure, similar to other authors.(8) When assessing hospital groups based on a priori caseload cutoffs (<50, 50-124, ≥125 cases), we saw the same general trends for all outcomes, with overall complications and serious complications having the highest reliability levels and most outliers detected (Appendix 1b, Appendix 2 figure, online only).

DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated that overall complications and serious complications have adequate reliability for differentiating hospital performance with bariatric surgery across a broad range of hospital caseloads. Reoperation had adequate reliability for hospitals with higher caseloads (120 cases/yr and higher), but not for hospitals with lower caseloads. Mortality had unacceptably low reliability for bariatric performance profiling at all caseloads. As expected, hospitals with higher caseloads were more likely to be outliers due to more statistical power. While overall complications and serious complications were common enough to allow identification of poor performing outliers (worse than expected performance) for most hospitals, the ability to identify high performing outliers (better than average performance) was seen only among hospitals with the highest caseloads. These findings provide guidance to bariatric surgery performance measurement platforms regarding which measures to emphasize.

It is critical that performance measurement programs account for the reliability of outcome measures. This will allow them to emphasize outcomes that provide meaningful peer comparisons, especially when adjusted performance and benchmarking is increasingly tied to accreditations, referral and reimbursement.(24) Commonly accepted reliability benchmarks for performance monitoring are 0.70 to 0.90,(14, 15) though some authors have proposed lower thresholds (0.40-0.70) for surgical quality reporting.(25) We have shown that overall and serious complications have the highest reliability among bariatric surgical outcomes and can be used to identify outlier performance even for most hospitals. Furthermore, we found higher reliability levels for most bariatric outcomes than previous studies,(7) probably due to complete sampling (100% of bariatric cases at each hospital) in our dataset. Our findings suggest that hospitals with lower caseloads can be meaningful participants in a national bariatric quality improvement program. These low volume centers will contribute valuable patient information for risk modeling and can expect to receive meaningful feedback regarding their overall complication and serious complication rates. In contrast, mortality following bariatric surgery was so rare that it could not be used to make any meaningful peer-based comparisons for any group of hospitals. Given how rare and important postoperative mortality is, it would be more beneficial for centers to review their deaths at a local level for quality improvement. Alternative strategies might include providing hospital mortality measures for a group of operations combined at the specialty level, which would increase sample size and reliability of the mortality measure, or employing different monitoring methods such as control charts.

A helpful analogy when considering outcome reliability is statistical power in clinical trials. Analogous to type II errors in underpowered clinical trials (failure to detect differences between groups when they exist), outcomes with low reliability will be unable to provide meaningful differentiation of provider performance. This was demonstrated in the present study, where outcomes with low reliability (e.g. reoperations) were much less able to identify outlying performance compared to outcomes with higher reliability (e.g. serious complications). With unreliable outcomes, there is also an increased chance of misclassifying hospital performance.(15, 21) This has important implications in quality improvement initiatives. If hospitals misinterpret extreme performance based on an unreliable quality metric, they may expend resources investigating and amending what may truly be average performance. This is referred to as ‘tampering’ in the quality improvement lexicon.(26, 27) In addition, centers mislabeled as having better than expected performance may be used to derive best practices for dissemination to all hospitals when in fact they are ‘average’ performers. Accounting for outcome reliability when profiling hospital performance will allow the context of the high and low outliers to be taken into accurate account.

These findings are especially important given that rates of adverse outcome for bariatric surgery have declined dramatically in recent years. The improvement is a success story in surgical safety but has made it more difficult to measure hospital performance.(2, 8, 9) As national surgical quality improves and adverse events become less frequent, outcome reliability necessarily decreases. In response, surgical quality improvement platforms have increasingly used statistical methods that account for lower outcome reliability—so-called “reliability adjustment.” Both national and regional quality improvement platforms utilize reliability adjustment for performance profiling, and the new MBSAQIP platform is considering using reliability adjusted outcomes to profile hospitals as well. (4, 22, 23, 28) By accounting for patient clustering and caseload differences between providers, reliability adjustment ‘shrinks’ hospitals’ adjusted outcome rates towards the overall average rate. (21) As a result, many lower-caseload centers will have ‘average’ performance for rare outcomes like reoperation. This underscores the importance of including other strategies in addition to adjusted outcome feedback in quality monitoring and improvement.

There are several strategies MBSAQIP should consider for maximizing quality improvement efforts in the face of outcomes with low reliability levels. In the early stages of accreditation under the new standards, centers could focus on process measures for improvement (e.g., CPAP masks in the post anesthesia recovery unit or improving long term follow-up rates). Such efforts require small capital investment and are important to continuous quality improvement. Second, MBSAQIP may consider limiting reporting rare outcomes (e.g., anastomotic leak, venous thromboembolism) until centers have accrued a threshold number of cases to reduce the number of ‘average’ centers on the report. Third, they may consider profiling hospitals using composite measures that combine metrics from different care domains (e.g., structural attributes, process compliance and readily identifiable outcomes). Composite measures have been shown, in general, to have higher reliability than single outcome metrics for other procedures,(24, 29-32) and may be of especial utility for hospitals with lower caseloads. Fourth, they should consider following their relative performance longitudinally. While reliability adjustment decreases outcome variation across hospitals, it also decreases the risk of misclassifying hospital performance.(15,21) This should allow more accurate assessment of temporal rank changes that represent quality differences and not statistical artifact caused by sample size. Such changes would be of interest to continuous quality improvement efforts no matter where the hospital lies on the outcomes’ distribution and could be used by hospitals with any caseload. It deserves mention that while the focus of the study was on risk-adjusted outcome feedback, such feedback is one of many components of a successful quality improvement program, and should be used in conjunction with other quality indicators to monitor and improve hospital performance.

Our work has important limitations. First, while we used a validated algorithm to detect outcomes from claims data, clinical registry data with standardized definitions may provide more robust outcomes.(8, 33) However, the focus of the present study was evaluating the reliability of common outcomes for performance profiling and outlier detection across hospital caseloads. Moreover, the outcome rates observed in the present study were consistent with other studies, including those using clinical registries.(22, 34) Second, we could not evaluate other outcomes meaningful to a bariatric quality improvement platform such as effectiveness of the procedures for weight loss and comorbidity resolution, or patient experience. However, the same issues with caseload and adjustment methodology would be expected to influence those outcomes’ reliability levels and usefulness for performance profiling as well. Third, we could not account for different operative techniques, procedure time or operator skill, which have been shown to influence outcome rates following bariatric surgery.(35-38) However, this was mitigated by our sample size and validated risk-adjustment strategy.

The present study shows that overall complications and serious complications have sufficient reliability for profiling bariatric performance, and can be used to identify outlier performance across a broad range of hospital caseloads. The MBSAQIP will be an important step towards national bariatric surgical quality improvement. Given national trends towards improvement, especially in bariatric surgery, a welcomed challenge will be identifying how best to use risk and reliability adjusted outcomes. Accurate identification of reliable outcomes is critical in identifying accurate targets for quality improvement and best practices to be shared between centers. Ensuring the data available to centers accredited by MBSAQIP are valid in regards to reliability adjustment will help establish the value of the program to surgeons, hospitals and outside third parties.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 1. (A) Risk and Reliability Adjusted Outcomes Rate Variation and Proportion of Outliers According to Different Caseload Thresholds, Laparoscopic Gastric Bypass Procedures Only

Appendix 1. (B) Risk and Reliability Adjusted Outcomes Rate Variation and Proportion of Outliers for All Stapling Procedures According to Different Caseload Thresholds

Appendix figure 1: Risk-and reliability adjusted outcome rates across hospital caseload cutoffs (serious complications). Y-axis: percent events (%); x-axis: hospital rank. (A) Lowest caseloads (<50 cases/yr); reliability 0.201. (B) Middle caseloads (50-124 cases/yr); reliability 0.426. (C) Highest caseloads (≥125 cases/yr); reliability 0.534.

Acknowledgments

Support: Dr Krell receives support from NIH grant 5T32CA009672-22. The funding organizations had no role in the concept or design of the study, or in the collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, or in the drafting or review of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure Information: Nothing to disclose.

Disclosures Outside the Scope of Current Work: JB Dimick has a financial interest in Arbormetrix, Inc., which had no role in this study. RW Krell received payment from Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan for data entry, unrelated to the submitted work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Livingston EH. The incidence of bariatric surgery has plateaued in the U.S. Am J Surg. 2010;200:378–385. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nguyen NT, Nguyen B, Shih A, Smith B, Hohmann S. Use of laparoscopy in general surgical operations at academic centers. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2013;9:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American College of Surgeons . Metabolic and bariatric surgery accreditation and quality improvement program. Chicago, Il: [Accessed Decemeber 1, 2013]. Available at: http://www.mbsaqip.org. [Google Scholar]

- 4.American College of Surgeons . Metabolic and bariatric surgery accreditation and quality improvement program standards and pathways manual [draft] American College of Surgeons; Chicago, Il: 2013. pp. 3–80. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dimick JB, Welch HG, Birkmeyer JD. Surgical mortality as an indicator of hospital quality: the problem with small sample size. JAMA. 2004;292:847–851. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.7.847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kao LS, Ghaferi AA, Ko CY, Dimick JB. Reliability of superficial surgical site infections as a hospital quality measure. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;213:231–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krell RW, Hozain A, Kao LS, Dimick JB. Reliability of risk-adjusted outcomes for profiling hospital surgical quality. JAMA Surg. 2014;149:467–474. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.4249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dimick JB, Nicholas LH, Ryan AM, Thumma JR, Birkmeyer JD. Bariatric surgery complications before vs after implementation of a national policy restricting coverage to centers of excellence. JAMA. 2013;309:792–799. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Livingston EH. Procedure incidence and in-hospital complication rates of bariatric surgery in the United States. Am J Surg. 2004;188:105–110. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2004.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Livingston EH. Bariatric surgery outcomes at designated centers of excellence vs nondesignated programs. Arch Surg. 2009;144:319–325. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2009.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Livingston EH. Bariatric surgery centers of excellence do not improve outcomes. Arch Surg. 2010;145:605–606. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2010.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Overview of the State Inpatient Databases (SID) Rockville, MD: [Accessed December 1, 2013]. Available at: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/sidoverview.jsp. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Santry HP, Gillen DL, Lauderdale DS. Trends in bariatric surgical procedures. JAMA. 2005;294:1909–1917. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.15.1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adams JL. The Reliability of Provider Profiling: A Tutorial. RAND Corporation; Santa Monica, CA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adams JL, Mehrotra A, Thomas JW, McGlynn EA. Physician cost profiling--reliability and risk of misclassification. New Engl J Med. 2010;362:1014–1021. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0906323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36:8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Southern DA, Quan H, Ghali WA. Comparison of the Elixhauser and Charlson/Deyo methods of comorbidity measurement in administrative data. Med Care. 2004;42:355–360. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000118861.56848.ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ash AA, Feinberg SE, Louis TA, et al. [Accessed January 1, 2014];Statistical issues in assessing hospital performance. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/HospitalQualityInits/Downloads.

- 19.Dimick JB, Staiger DO, Birkmeyer JD. Ranking hospitals on surgical mortality: the importance of reliability adjustment. Health Serv Res. 2010;45:1614–1629. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01158.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones HES. D.J. The identification of “unusual” health-care providers from a hierarchical model. Am Stat. 2011;65:154–163. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dimick JB, Ghaferi AA, Osborne NH, Ko CY, Hall BL. Reliability adjustment for reporting hospital outcomes with surgery. Ann Surg. 2012;255:703–707. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31824b46ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Birkmeyer NJ, Dimick JB, Share D, et al. Hospital complication rates with bariatric surgery in Michigan. JAMA. 2010;304:435–442. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen ME, Ko CY, Bilimoria KY, et al. Optimizing ACS NSQIP modeling for evaluation of surgical quality and risk: patient risk adjustment, procedure mix adjustment, shrinkage adjustment, and surgical focus. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;217:336–346. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scholle SH, Roski J, Adams JL, et al. Benchmarking physician performance: reliability of individual and composite measures. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14:833–838. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Merkow RP, Hall BL, Cohen ME, et al. Validity and Feasibility of the American College of Surgeons Colectomy Composite Outcome Quality Measure. Ann Surg. 2013;257:483–489. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318273bf17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheung YY, Jung B, Sohn JH, Ogrinc G. Quality initiatives: statistical control charts: simplifying the analysis of data for quality improvement. Radiographics. 2012;32:2113–2126. doi: 10.1148/rg.327125713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wan Th CAM. Monitoring the Quality of Health Care: Issues and Scientific Approaches. Springer; New York: 2003. Total Quality Management and Continuous Quality Improvement; pp. 143–58. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative [Accessed December 1, 2013];Program Overview. Available at: http://msqc.org/about_program_overview.php.

- 29.Chen LM, Staiger DO, Birkmeyer JD, Ryan AM, Zhang W, Dimick JB. Composite quality measures for common inpatient medical conditions. Med Care. 2013;51:832–837. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31829fa92a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dimick JB, Birkmeyer NJ, Finks JF, et al. Composite Measures for Profiling Hospitals on Bariatric Surgery Performance. JAMA Surg. 2014;149:10–16. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.4109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dimick JB, Staiger DO, Hall BL, Ko CY, Birkmeyer JD. Composite measures for profiling hospitals on surgical morbidity. Ann Surg. 2013;257:67–72. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31827b6be6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dimick JB, Staiger DO, Osborne NH, Nicholas LH, Birkmeyer JD. Composite measures for rating hospital quality with major surgery. Health Serv Res. 2012;47:1861–1879. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01407.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iezzoni LI, Daley J, Heeren T, et al. Identifying complications of care using administrative data. Med Care. 1994;32:700–715. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199407000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jafari MD, Jafari F, Young MT, Smith BR, Phalen MJ, Nguyen NT. Volume and outcome relationship in bariatric surgery in the laparoscopic era. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:4539–4546. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-3112-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Birkmeyer JD, Finks JF, O’Reilly A, et al. Surgical skill and complication rates after bariatric surgery. New Engl J Med. 2013;369:1434–1442. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1300625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Birkmeyer NJ, Finks JF, Greenberg CK, et al. Safety culture and complications after bariatric surgery. Ann Surg. 2013;257:260–265. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31826c0085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Finks JF, Carlin A, Share D, et al. Effect of surgical techniques on clinical outcomes after laparoscopic gastric bypass--results from the Michigan Bariatric Surgery Collaborative. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2011;7:284–289. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krell RW, Birkmeyer NJ, Reames BN, et al. Effects of Resident Involvement on Complication Rates after Laparoscopic Gastric Bypass. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;218:253–260. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 1. (A) Risk and Reliability Adjusted Outcomes Rate Variation and Proportion of Outliers According to Different Caseload Thresholds, Laparoscopic Gastric Bypass Procedures Only

Appendix 1. (B) Risk and Reliability Adjusted Outcomes Rate Variation and Proportion of Outliers for All Stapling Procedures According to Different Caseload Thresholds

Appendix figure 1: Risk-and reliability adjusted outcome rates across hospital caseload cutoffs (serious complications). Y-axis: percent events (%); x-axis: hospital rank. (A) Lowest caseloads (<50 cases/yr); reliability 0.201. (B) Middle caseloads (50-124 cases/yr); reliability 0.426. (C) Highest caseloads (≥125 cases/yr); reliability 0.534.