INTRODUCTION

Debates surrounding the appropriate design and conduct of clinical research in low-resource settings have bedeviled the scientific, policy, and bioethics communities for decades. Historically, controversies primarily involved trials related to infectious disease. With the growing globalization of cancer clinical trials and the recognition of cancer as a public health threat in developing as well as developed countries, these debates will increasingly engage the cancer research community.

The paradigmatic case that sparked discussion of the ethics of international clinical trials concerned the development of antiretroviral therapies to prevent vertical transmission of HIV from pregnant women to their newborn infants. In 1994, the AIDS Clinical Trials Group published results of the Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group Protocol 076 trial (hereafter, 076), a study conducted in the United States and France that compared an intensive and prolonged regimen of perinatal zidovudine to placebo.1 The 076 regimen reduced the risk of vertical transmission from 25.5% to 8.3%, and it rapidly became the standard of care for HIV-infected pregnant women in developed nations. Most of the world's burden of HIV, however, resided in low-resource areas such as sub-Saharan Africa, areas in which the 076 regimen was infeasible for financial and logistical reasons. Thus, numerous research teams set out to identify less expensive, less logistically demanding approaches to the problem of perinatal transmission.

Because standards of care in low-resource countries after the publication of the 076 study did not include zidovudine, most teams compared potentially feasible new interventions against placebo controls. In 1997, Lurie and Wolfe2 and Angell3 ignited a firestorm with the charge that placebo-controlled trials of perinatal short-course zidovudine, one of the regimens under study as a feasible alternative to the 076 regimen, unethically denied proven effective therapy to control-group participants. Pointing out that placebo-controlled studies of interventions to reduce the incidence of vertical HIV transmission were no longer acceptable in developed countries, they claimed that the use of placebos in developing-world trials represented an unethical double standard. Angell, invoking the memory of the infamous Tuskegee syphilis study, claimed that “acceptance of this ethical relativism could result in widespread exploitation of vulnerable Third World populations for research programs that could not be carried out in the sponsoring country.”3 Study sponsors and other commentators disputed this position, arguing that placebo controls were necessary to assess the efficacy and feasibility of the short-course regimen as compared with the absence of antiretroviral treatment and that no patients were made worse off by trial participation relative to the local standard of care.4,5

Cancer, too, is increasingly a disease of the developing world. According to the American Cancer Society, 56% of cancer cases and 64% of cancer deaths in 2008 occurred in the economically developing world.6 Such statistics highlight a pressing need for high-quality research to identify feasible, evidence-based therapeutic strategies appropriate for low-resource settings.

Despite the public health urgency of cancer in the developing world, along with the globalization of industry-sponsored clinical research, the ethics of cancer clinical trials in low-resource settings have received little attention.7,8 However, recent controversies suggest that these trials may come under increased scrutiny.9–13 What are the appropriate standards for the design and conduct of such trials? Ethical criteria for clinical research are generally held to universally.14 Differences in health service priorities and wide disparities in background conditions, however, raise the possibility that the questions asked and the methods used to answer them might justifiably vary across regions.

Two questions relevant to clinical trials in low-resource settings are particularly vexing. First, what is the proper control group for evaluating investigational treatments in this setting? As with HIV, investigators conducting cancer trials—especially those based at developed-world institutions or funded by developed-world sources—must decide whether trials should compare novel interventions to the developed-world standard of care, or if it is acceptable, or even preferable, to evaluate them against locally available treatments. Second, must these trials have the potential to benefit the host population? These questions, which encompass what sponsors and investigators owe both to study participants and to host communities, remain unsettled to this day.15

CHOICE OF CONTROL GROUP IN DEVELOPING-WORLD CLINICAL TRIALS

In considering ethical duties to individuals from low-resource settings who participate in trials, sponsors, investigators, and research oversight bodies must address the issue of what interventions should be used as comparators. International statements of research ethics, including the World Medical Association's Declaration of Helsinki and guidelines from the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS), assert that if an intervention has been proven effective in high-resource settings, it is at the very least presumptively unethical to withhold that intervention from control-group participants.16,17 The Declaration has undergone frequent revisions since publication of the first version in 1964. According to the current version, with limited exceptions, “The benefits, risks, burdens and effectiveness of a new intervention must be tested against those of the best proven intervention(s).”16 The CIOMS guidelines, in force since 2002, state that “as a general rule, research patients in the control group of a trial of a diagnostic, therapeutic, or preventive intervention should receive an established effective intervention.”17 Thus, at first blush, it appears that, regardless of the local standard of care, withholding a proven effective intervention such as cervical cancer screening,11,12 endocrine ablation for women with operable breast cancer,7 or anti–human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) therapy from women with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer9 from control-group participants contravenes these two authoritative statements of research ethics.

Both the Declaration and the CIOMS guidelines identify limited exceptions to the requirement that the control group incorporate the “best current prophylactic, diagnostic, and therapeutic methods.” According to the current version of the Declaration,16 placebo controls may be considered “… where for compelling and scientifically sound methodological reasons the use of any intervention less effective than the best proven one…is necessary to determine the efficacy or safety of an intervention and the patients who receive any intervention less effective than the best proven one… will not be subject to additional risks of serious or irreversible harm as a result of not receiving the best proven intervention… Extreme care must be taken to avoid abuse of this option.”

The CIOMS guidelines similarly permit use of a placebo control “when use of an established effective intervention as a comparator would not yield scientifically reliable results and use of placebo would not add any risk of serious or irreversible harm to the subjects.”17

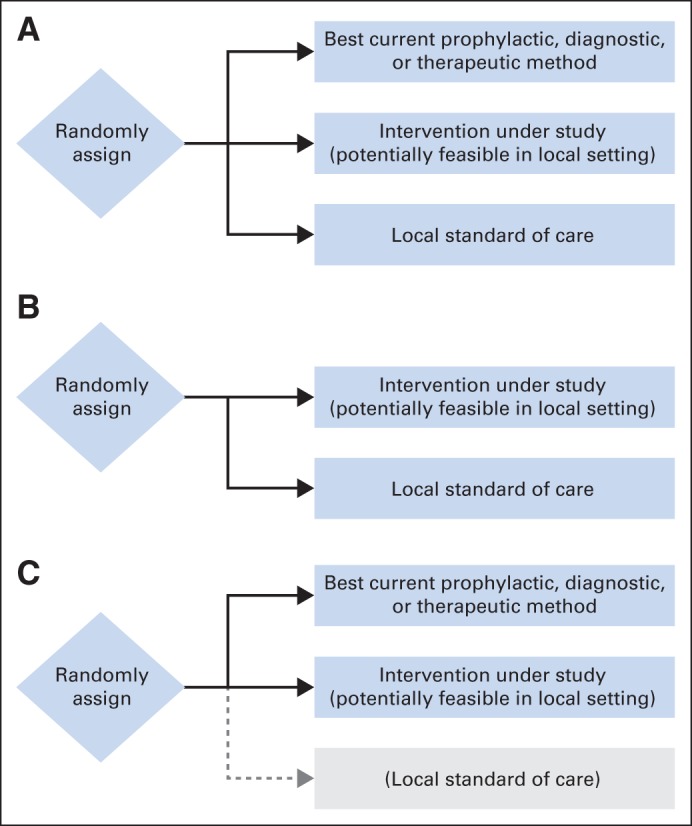

In selecting control groups, it is necessary to consider the methodological options. The most comprehensive and scientifically informative design includes two comparator groups—one incorporating the local standard of care (often no intervention or, in a blinded trial, a placebo), and a second incorporating the known effective therapy (Fig 1A). This design allows investigators to ask two important questions: whether the new therapy is more effective than the local standard and how its effectiveness compares to that of the currently validated therapy. The second plausible design—and the focus of ethical criticism—includes only a local-standard comparator (Fig 1B). Finally, investigators might eliminate the local-standard group from the design shown in Figure 1A and compare the novel intervention against the known effective therapy only (Fig 1C). Interpreting the results of such a study, however, entails an indirect and conceptually problematic inference about how the results among participants receiving the novel intervention compare with those that would have been observed in the local-standard comparator group had the scientifically optimal three-group design been used.

Fig 1.

Plausible designs for evaluating a feasible new treatment in a low-resource setting when an intervention has been proven effective for the indication in question but is unavailable in the local setting. (A) The first design directly tests whether the novel intervention is superior to the local standard of care (often a placebo) and whether it is inferior to existing proven therapy. (B) The second design tests only whether the novel intervention is superior to the local standard of care. (C) The third design directly tests whether the novel intervention is inferior to existing proven therapy. Although investigators may wish to draw conclusions about how the novel therapy compares with the local standard of care, doing so requires assumptions about what the outcome of a hypothetical arm evaluating the local standard, shown in gray, would have been.

Critics of placebo-controlled trials in low-resource settings advocate the use of active-control equivalence trials (Fig 1C). Rather than asking whether a novel intervention is superior to a comparator, such trials generally ask whether the intervention under study is equivalent, or at least noninferior by some specified margin, to an established standard treatment. Interpretation of active-control trials is subject to at least two strong assumptions, the second of which cannot be verified within the trial.18 First, there must be convincing prior evidence that the comparator intervention is itself more effective than placebo for the indication in question. Second, investigators must assume counterfactually that, had the active-control trial included a third placebo group, the active comparator would have been shown to be superior to placebo in that trial (Fig 1C). Given the great variability in placebo response rates and the high proportion of negative studies in some settings, such as in trials of antidepressant agents, this assumption may not be reasonable. Temple and Ellenberg18 label these methodological concerns the problem of assay sensitivity.

Active-control trials pose an even greater inferential challenge for investigators seeking to evaluate feasible and affordable therapeutic approaches for low-resource settings. In an active-control trial intended to inform treatment in a developed country, investigators wish to avoid endorsing an intervention that is truly less effective than current standards. They therefore design and power studies with narrow inferiority margins. Assuming the conditions for assay sensitivity are satisfied, investigators can reasonably conclude from a successful active-control trial designed according to these constraints that a novel intervention is more effective than a (hypothetical) placebo control. However, even if a novel therapy under evaluation in low-resource settings is less effective than the best available standard of care, investigators and the communities on whose behalf they conduct the research may be willing to deem it as successful and endorse it for clinical use so long as it represents a sufficient improvement over what is currently available in the local context. Any inference about how a novel therapy that is shown in a clinical trial to be modestly inferior to an active control compares with what would have been observed had the study included a placebo control group (Fig 1C) is tenuous at best. For example, suppose that the short-course zidovudine treatment had been shown to be less effective than the 076 regimen in an active-control trial that did not include a placebo control group—a result that would not have been surprising. The question would still remain whether the less expensive and more feasible regimen would reduce vertical transmission of HIV in settings in which antiretroviral treatment was not otherwise available for this purpose.4 In other words, the research question that was directly relevant to the local population in resource-poor settings was whether the short course of zidovudine was better than the existing standard of care, not whether it was at most modestly inferior to the 076 regimen.

Beyond methodological questions, the basic premise underlying the Declaration's and CIOMS's presumption against use of placebo controls when a therapy has previously been shown to be effective—that such trials offer participants assigned to the placebo group an unfavorable balance of risks and benefits—demands scrutiny. Judging the risk-benefit balance of any intervention requires specification of the appropriate baseline. If the risks and benefits of assignment to a placebo group are assessed against the alternative of receipt of proven effective therapy outside the trial, then inclusion of a placebo group disadvantages participants. This baseline, however, is flawed.19 Assessing risks and benefits by comparison to theoretical rather than actual alternatives ignores the perspective of the real individuals who are eligible for the trial. Rather, eligible individuals will ask how the risks and benefits of joining the trial and being assigned to the placebo group compare with what is available to them outside the trial. For such individuals, assignment to the placebo group is at worst neutral with respect to the alternatives they face. Furthermore, even if assignment to the placebo group entails neither net benefit nor net harm, entry onto the trial is advantageous: every participant has an ex ante chance of receiving an intervention that is potentially beneficial as compared with the local standard of care.20

In assessing whether a proposed study represents an unfavorable balance of benefits and risks for participants, a useful heuristic is to ask how a knowledgeable independent clinician responsible for an eligible patient would advise her, bearing in mind the available treatment options.21 It is difficult to understand why a study should be judged presumptively unethical when an independent clinician, concerned only with the eligible patient's best interest, would have no reason to recommend against enrolling. Indeed, given the prospect of being randomly assigned to receive the potentially beneficial investigational treatment, the independent clinician would have good reason to advise the patient to participate in the trial.

POTENTIAL TO PROVIDE HEALTH BENEFITS TO THE HOST POPULATION

Decisions about the appropriate control group depend upon the obligations of sponsors, investigators, and research oversight bodies to individual study participants. In addition, these parties must consider what, if any, obligations they hold toward the host population or community that extend in time and space beyond the research itself. The CIOMS guidelines assert that trials performed in low-resource settings are ethical only if the intervention under study, if proven safe and effective, has the potential to provide health benefits to the communities or countries in which the trials are conducted. According to Guideline 10,17 “Before undertaking research in a population or community with limited resources, the sponsor and the investigator must make every effort to ensure that the research is responsive to the health needs and the priorities of the population or community in which it is to be carried out and that any intervention or product developed, or knowledge generated, will be made reasonably available for the benefit of that population or community.”

As outlined by CIOMS, the requirement that a study have the potential to provide health benefits to the host population has two components: (1) responsiveness to local health needs and priorities, and (2) an expectation that any products or knowledge that results from the study will be made reasonably available to the host population. Underlying this requirement is a view that, unless the knowledge derived from a study has the potential to benefit the population in which the study takes place, the study unethically exploits members of that population for the benefit of others.

The question of whether clinical research in low-resource settings must have the potential to provide health benefits to the host population is one of the most ethically complex and unsettled topics relevant to research conducted in low-resource settings.15,20,22 There are at least three problems with this requirement. First, if individual participants stand to derive substantial benefits from the research, it is not obvious why they should be denied the possibility of those benefits simply because the fruits of the study will not ultimately accrue to their broader community. Second, communities might benefit from other aspects of the research that outlive the project, such as local capacity-building or infrastructure development; the requirement that clinical research in low-resource settings offers the potential for health benefits to the host population denies communities the freedom to bargain for the benefits that they view as most valuable in exchange for allowing a trial to proceed.23 Third, even if a study is responsive to local health priorities and the intervention proves effective in the trial, sponsors and investigators are at best able to influence, but cannot guarantee, whether it will be reasonably available to the host population. Other entities, including regulatory agencies, government ministries, and (depending on the mix of health systems in the country) private insurers will also play critical roles in determining whether or not successful interventions will ultimately be available to average individuals within the populations of host countries.

Rather than requiring reasonable availability, sponsors, investigators, and research oversight bodies should ensure that communities receive fair benefits in exchange for their participation in the study. Provision of fair benefits has both substantive and procedural elements. Substantively, fair benefits might include some combination of direct and indirect health benefits to study participants; health, economic, or other benefits to communities during the period of the study; or health or other benefits including but not limited to reasonable availability of effective interventions after the study concludes. Procedurally, ensuring fair benefits requires collaborative partnerships with communities and their representatives, with careful attention to minimizing inequalities of bargaining power. The goal is to ensure “free, uncoerced decision-making [about whether or not to participate by the] population bearing the burdens of the research.”23 By definition, studies that provide participating communities with fair benefits do not exploit those communities.24

DO ETHICAL OBLIGATIONS VARY BY STUDY SPONSOR?

Discussions of the ethics of research in low-resource settings have ignored the possibility that ethical obligations, especially to host communities and populations, might vary depending on the nature and mission of the sponsoring entity. Rather, commentators assume, implicitly at least, that ethical guidelines for research in the developing world should be uniform across government, foundation, and for-profit sponsors. This assumption fails critical evaluation.

Government and foundation sponsors generally describe their missions in public-interest terms. The National Institutes of Health, the primary public funder of biomedical research in the United States, describes its mission as “to seek fundamental knowledge about the nature and behavior of living systems and the application of that knowledge to enhance health, lengthen life, and reduce illness and disability.”25 Although arguably the primary concern of the National Institutes of Health is the “health of the Nation,” when the Institutes sponsor research in the developing world, their rationale for doing so is, at least in part, a form of foreign aid. Similarly, foundations that sponsor research in the developing world do so for philanthropic reasons. For example, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, a major sponsor of global health research, describes itself as follows:“Guided by the belief that every life has equal value, the … Foundation works to help all people lead healthy, productive lives. In developing countries, it focuses on improving people's health and giving them the chance to lift themselves out of hunger and extreme poverty.”26 It is reasonable to expect sponsors that describe their objectives in such terms to be bound by the requirement that any research they sponsor in the developing world have the potential to benefit the host population—not because failure to do so would violate their duties to host communities, but rather because it would contradict their institutional missions.

In contrast to governments and foundations, publicly traded for-profit corporations have a primary obligation to engage in activities that will maximize shareholder value. Although companies ideally should price their products—at least those that address essential health needs—so that they are accessible to patients in low-resource settings,15,27 there is no general requirement that companies provide in-kind benefits to the particular communities in which their research activities take place. They cannot, of course, use any means whatever to maximize shareholder value but must respect various moral, legal, and other constraints on what is permissible. Consider a company based in a wealthy country that builds a factory to manufacture high-end apparel in a developing nation. We expect that the company will pay its workers fairly, provide them with decent working conditions, comply with local laws, and avoid imposing harmful externalities such as dumping toxic wastes into the local water supply. We do not, however, criticize the company for the fact that few individuals in the host country will have access to the factory's products. By analogy, companies that engage in clinical research in developing countries must respect universal ethical constraints, such as ensuring that individuals' participation is voluntary and consensual and that participants receive fair benefits from their involvement with the study, and must refrain from imposing harmful externalities on host communities.14 Given their distinct missions, however, requiring that the research activities of for-profit sponsors have the potential to provide health benefits to the host population is ethically misguided.20 Although it is desirable for industry-sponsored studies to offer health benefits to the host population, such studies should not be prohibited as long as they offer participants a level of benefits that is at least as good as the local standard of care.

Some might argue that, whatever the obligations of sponsors, clinician-investigators should not as a matter of professional integrity participate in studies conducted in less-developed countries when the research is not aimed at providing health benefits to the host population. Yet the basis for this stance is not clear. If the research passes the independent clinician test, such that it offers participants a prospect of benefit that is equal to or greater than that of treatment according to the local standard of care, then there are no grounds for ethical criticism of investigators that derive from the absence of health benefits for the host population.

THE QUESTION OF BACKGROUND INJUSTICE

In considering the ethics of clinical trials in low-resource settings, we cannot ignore the question of how disparities among countries in health and health care arose. If wealthy countries historically are at least partly responsible for the plight of poor countries, then there may be some reason to think that investigators and sponsors from developed nations have ethical obligations, grounded in compensatory justice, to use clinical research as a vehicle of redress.15 Proponents of this position might argue, for example, that investigators should not accept the local standard of care as justifying the use of placebo controls, but rather should view the developed-world standard as establishing a normative baseline against which to judge the adequacy of interventions available in a trial. Similarly, proponents might argue that investigators and sponsors have a duty to correct past and present injustices, and that this duty grounds an oligation—including among for-profit sponsors—to ensure that clinical trials in low-resource settings have the potential to benefit the populations in which they are conducted.

A full discussion of the causation of global health disparities and its implications for contemporary investigators and sponsors is beyond the scope of this article. However, there are at least two reasons for skepticism about the claim that investigators and sponsors have a duty to seek compensatory justice through the design and conduct of research. First, even if one accepts that, as a result of their past actions, wealthy nations have a general responsibility to remedy the background conditions of poor countries, it does not follow that this responsibility attaches to individual investigators and sponsors in the context of clinical research. Second, imposing constraints based in compensatory justice may ironically disadvantage the very individuals and communities that those constraints were intended to benefit. Requiring that trials conducted in low-resource settings compare novel interventions to locally unavailable therapies risks making them uninterpretable or irrelevant to the local population. In addition, requiring that interventions be reasonably available to the host population if shown to be safe and effective in a trial reduces the freedom of the host community to bargain for the package of benefits that best fits its needs and circumstances in exchange for allowing the trial to proceed.23

In conclusion, we have argued that, when designing and conducting research in low-resource settings, those alternatives that are generally available in the local context in which a trial will be conducted should serve as the appropriate baseline for evaluating its benefit-risk balance. As a result, there is no ethical obligation to compare novel interventions against treatments that, although proven effective in trials conducted in developed countries, are locally inaccessible. Indeed, if the goal of the study is to evaluate a feasible therapeutic intervention to address a local health need, requiring that it be compared against therapies that are only available elsewhere risks answers that fail the test of local relevance. Finally, there is no ethical basis, other than consistency with the publicly articulated missions of certain classes of sponsors, for requiring that research have the potential to provide health benefits to the communities or populations in which the research is conducted.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect the position or policy of the National Institutes of Health, the Public Health Service, or the Department of Health and Human Services.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest are found in the article online at www.jco.org. Author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Disclosures provided by the authors are available with this article at www.jco.org.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Steven Joffe, Franklin G. Miller

Collection and assembly of data: Steven Joffe, Franklin G. Miller

Data analysis and interpretation: Steven Joffe, Franklin G. Miller

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The Ethics of Cancer Clinical Trials in Low-Resource Settings

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. For a detailed description of the disclosure categories, or for more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to the Author Disclosure Declaration and the Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest section in Information for Contributors.

Steven Joffe

Consulting or Advisory Role: Genzyme/Sanofi

Franklin G. Miller

No relationship to disclose

REFERENCES

- 1.Connor EM, Sperling RS, Gelber R, et al. Reduction of maternal-infant transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 with zidovudine treatment: Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group Protocol 076 Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1173–1180. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199411033311801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lurie P, Wolfe SM. Unethical trials of interventions to reduce perinatal transmission of the human immunodeficiency virus in developing countries. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:853–856. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709183371212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Angell M. The ethics of clinical research in the Third World. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:847–849. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709183371209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Varmus H, Satcher D. Ethical complexities of conducting research in developing countries. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1003–1005. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199710023371411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mbidde E. Bioethics and local circumstances. Science. 1998;279:155. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5348.155a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, et al. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Love RR, Duc NB, Allred DC, et al. Oophorectomy and tamoxifen adjuvant therapy in premenopausal Vietnamese and Chinese women with operable breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2559–2566. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.08.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Love RR, Fost NC. Ethical and regulatory challenges in a randomized control trial of adjuvant treatment for breast cancer in Vietnam. J Investig Med. 1997;45:423–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guan Z, Xu B, DeSilvio ML, et al. Randomized trial of lapatinib versus placebo added to paclitaxel in the treatment of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1947–1953. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.5241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ades F. Lapatinib versus placebo added to paclitaxel in first-line human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive metastatic breast cancer: Ethical lessons not learned from Africa. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:4271. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.0289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shastri SS, Mittra I, Mishra GA, et al. Effect of VIA screening by primary health workers: Randomized controlled study in Mumbai, India. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106:dju009. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sankaranarayanan R, Nene BM, Shastri SS, et al. HPV screening for cervical cancer in rural India. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1385–1394. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagarajan R. Row over clinical trial as 254 Indian women die. Times of India. 2014 Apr 21; [Google Scholar]

- 14.Emanuel EJ, Wendler D, Grady C. What makes clinical research ethical? JAMA. 2000;283:2701–2711. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.20.2701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Macklin R. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2004. Double Standards in Medical Research in Developing Countries. [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310:2191–2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS) International Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research Involving Human Subjects. http://www.cioms.ch/publications/guidelines/guidelines_nov_2002_blurb.htm. [PubMed]

- 18.Temple R, Ellenberg SS. Placebo-controlled trials and active-control trials in the evaluation of new treatments: Part 1. Ethical and scientific issues. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:455–463. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-6-200009190-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joffe S, Miller FG. Equipoise: Asking the right questions for clinical trial design. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2012;9:230–235. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wertheimer A. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2011. Rethinking the Ethics of Clinical Research: Widening the Lens. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rid A, Wendler D. A framework for risk-benefit evaluations in biomedical research. Kennedy Inst Ethics J. 2011;21:141–179. doi: 10.1353/ken.2011.0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolitz R, Emanuel E, Shah S. Rethinking the responsiveness requirement for international research. Lancet. 2009;374:847–849. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60320-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Participants in the 2001 Conference on Ethical Aspects of Research in Developing Countries. Ethics—Fair benefits for research in developing countries. Science. 2002;298:2133–2134. doi: 10.1126/science.1076899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wertheimer A. Exploitation. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Institutes of Health. About NIH: Mission. http://www.nih.gov/about/mission.htm.

- 26.Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Who We Are. http://www.gatesfoundation.org/Who-We-Are/General-Information/Foundation-Factsheet.

- 27.Resnik DB. Developing drugs for the developing world: An economic, legal, moral, and political dilemma. Dev World Bioeth. 2001;1:11–32. doi: 10.1111/1471-8847.00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]